HD28 .M414

iVo

U7(r

Dewey

•JUL

29

1982Centerfor

InformationSystems Research

MassachusettsInstituteofTechnology Sloan SchoolofManagement

77 MassachusettsAvenue

©

COGNITIVE STYLE RESEARCH:

A PERSPECTIVE FOR INTEGRATION

PeterG. W. Keen

Gloria S. Bronsema

December 1981

CISR No. 82 Sloan WP No. 1276-82

P. G. W. Keen and G. S. Bronsema 1981

This paper was presented at, and was published in the Proceedings of, the Second International Conference on Information Systems, December, 1981, Cambridge, Mass.

Center for Information Systems Research

Sloan School of Management

M.I.T.LfBRARitS

JUL

2 9 1982Co^itiveStyleResearch:

A

PerspectiveforIntegration* Peter G.W. KeenSloanSchool of

Management

MassachusettsInstituteofTechnologyGloriaS.Bronsema

HarvardUniversity

P

ABSTRACT

Cognitivestyleisa continuingareaof interestinMISresearch. The work is oftencriticized for its fragmentation and lack of validity. This paper proposes the uses of a single instrument, the Myers-BriggsTypeIndicator(MBTI). Itreviews theoverall issue of validity and identifies thefour stepscognitivestyleresearchmust

accom-plishtoachieve coherence. Itassesses existingresearch relatedto thosesteps,focusingonfindingsfromstudiesthatuse theMBTI. It presents data on cognitive style differences

among

occupational specialties., ISSUES

OF

COGNITIVE

STYLE

INMIS

RESEARCH

The link between cognitive style and the

implementation and use of information systemsand modelsisarecurringthemein

MIS/MS research. Studies of cognitive

stylereflecttwocentralassumptions:

1. There are systematic differences

among individualsintermsof per-ception, thinking, and judgment

that significantly influence their choiceofand responseto

informa-tion.

2. The difference between managers' and analysts' cognitive styles is a major explanationof difficultiesin

implementation.

Table I traces the evolution of cognitive

*We, the authors, wish to thank Roberta Fallon for her time,patience, and contri-butions to thispaper.

style research in MIS. The work is

frag-mented and uses a variety of overlapping

constructs and measures. The empirical results are generally equivocal and incon-sistentand,all inall,theresearch has not generated convincing evidence to support thehypotheses implicitinthetwo assump-tions listed above (Taylor and Benbasat,

1980;Wade, 1981).

That said,the cognitive styletheme is of persistent interest and influence in MIS.

TheworkofChurchman(1964),Churchman

and Schainblatt (1965), and Mason and Mitroff (1973) constitutes an unfinished

programforresearchon the dynamic inter-action between information and

personal-ity. Taylor and Benbasat's critique of previous studies (1980) points to the high potential payoff from"sound researchinto the psychological characteristics of infor-mationsystem users," though itjustifiably highlights "inadequately formulated theory," "use of agreat

many

inadequately validated measuring instruments," and "faultyresearchdesigns."5

i^

3-O -P ^ C he •rj OJ o T3 CO u C Q) X O' 2 M 3si

» § S <u2ii

^^

. gj-1-1 K»> &4 -H M 0) o3e *-S.S 5 « o c ?-2 C CQ CO 5?<^^

CD O"O CO o c't! fH O ftQJ "^-M Sis o ft ca2

"2 g CO O.S5

o bcg •S ft 3 c^

O to -^ c c o CO-Oas

o <u ft.S 3 « CO O QJ 42 CQ« « 3 S « g

a

9 73 Ot^ O-o o 3 73 0) ,E " be •B-S o o ES

o bbM P O be(yr

The aimofthispaper isto

make

acasefor theuseoftheMyers-Briggs Type Indicator asthe baseforcognitivestyle research.1. Itisbased ona theoreticallystrong paradigm of Psychological Type

derivedfrom Jungthathas beenof substantial influenceon researchin

or related to the MIS field(Mason

&

Mitroff, 1973,Churchman, 1971,Kilman and Mitroff, 1976, and de

Waele 1978). All provide a rich,

pragmatic, philosophical discussion ofTypetheoryinrelation to infor-mation and decision aids. It is worth noting that cognitive style research effectively began within

|

this tradition, with Churchman's) (1964) and Churchman

&

Schain-blatt's(1965)explorationofmutual

understanding between analystand manager.

2. The MBTI is a reliable measure. While Strieker and Ross (1964) question some aspects of the MBTI's construct validity, there is

a general agreement in the litera-ture on psychological testing that the MBTI is reliable and well-designed. It is also backed up by large-scaledata banks and surveys (McCaulley, 1977). The MBTI has strong predictive validity (Myers, 1980). There have been no

criti-cismsof itsconvergentor discrim-inant validity.

3. The empirical results of Ghani (1980),Henderson and Nutt (1980), Mitroff and Kilman (1976), and others indicate that the MBTI dis-criminates behavior relevant to information systems design and use.

sometimes surprising differences

between occupational typesandjob levels

among

managers,profession-als,and peopleincomplex, special-ized jobs. The datawere gathered over a five-year period. The authorshave feltno incentiveuntil

recently to publish the results,

even though they are statistically significant (P<.05, .01,.001). Basi-cally, they show that specialized jobs attract people of specialized cognitive styles. These resultsare ofimportance onlyif itcanalsobe

shownthatdifferences incognitive style clearly relate to behavior relevant to information systems (item 3 above). It is not enough simplyto point to differences.

Thecentral argumentof this paper is that the MBTI provides a valid theory and

measureofcognitive style. Bagozzi(1980) identifies six aspects of validity in be-havioralmeasures:

1. Conceptuol Validity. Does the theory

make

sense and themeasurement relate to it andvice

>/•

J-versar

Construct Validity-, Does the instrument truly measure the theoreticalconstruct?

Convergent Validity.

Do

the instruments claiming to measurethe same thing correlate ade-quately?

4. Discriminant Validity. In turn, do they clearly not correlate with instruments measuring other factors?

4. MBTIdatacollectedby the authors ofthispaper and taken from other sources point to significant and

5. Predictive Validity. Can the

measures be used to predict rele-vantbehavior?

6. Nomological Validity. Does the

specificconstructrelate to awider theoreticalscheme?

In trying to establish any paradigm, the researcher hasto address all these issues.

Most cognitive style research has tackled

only the first and fifth (conceptual and

predictive). Bagozzi's framework is useful

for evaluating candidate models of cog-nitive style. Apart from the MBTI, only one measure, Witkin's Embedded Figures Test (EFT) (1964) and variations on it,

seems to merit serious consideration as a

generalbaseforcognitive styleresearch in

MIS.

The

EFT

is based on Witkin's fielddepen-dence/independence model, which has been widely used in experimental research in MIS (Lusk, 1973; Doktor and Hamilton, 1973; Benbasat and Dexter, 1979). This paper makes the case for the MBTI and rejects the

EFT

as not valid for MIS research. Thismay

ormay

not befair,but the case for the Witkin model must bemade

in terms of Bagozzi's categories of validity. Thispaperclarifies the issuesand provides a challenge for those who feel Witkin's model and theEFT

are more suit-able.Thereare four interrelated stepsneededto

move

cognitive style research from frag-mentation to coherence, and fromplaus-ibilityto validity:

1. Define a conceptually meaningful paradigmofcognitivestyle.

2. Developa reliablemeasure.

3. Establish that the measure dis-criminates behaviorrelevant tothe development and use of informa-tionsystems.

4. Demonstrate that analysts and

users or managers differ cantlyintermsof style.

signifi

The structure of thispaper corresponds to thesequenceof steps outlinedabove:

1. Define a conceptually meaningful

paradigm. The secondsection

dis-cusses the mainparadigms of cog-nitive style in MIS research. The

third sectiondescribes key concep-tual and psychometric issues and

linkscognitive style to theMBTI.

2. Develop a reliable measure. The

fourth section reviews the MBTI,

focusing on definitions and con-struct,andstatistical validity.

3. Demonstrate the measure

discri-minates relevant behavior. The

fifth section summarizes applied

researchusingtheMBTI.

4. Demonstrate analysts and users/

managers differ significantly. The

sixth section presents data on career specialization froma range of sources. The results challenge thebasichypothesisthatmanagers

and analysts in general differ in

style. There are significant vari-ations across functional areas and

job levels. Top managers seem,

surprisingly, different as a group than middle managers and MBA's.

A

sharper definition of "manager"or "user"isneeded inMISresearch.

The final section summarizes the

case for the MBTI as a valid

measure and briefly contrasts it

with theEFT.

PARADIGMS OF

COGNITIVE STYLE

Kogan (1976)providesabroaddefinition of cognitivestyle:

Theconstruct ofcognitivestylehas been with us for approximately a quarter of a century and it con-tinues to preoccupy psychologists

working in the interface between

cognitive and personality. There are individual differences in styles of perceiving, remembering,

think-ing, and judging, and these

indi-vidual variations, if not directly part of the personality are at the very least intimately associated with various noncognitive dimen-sions ofpersonality.

Messick (1970) identifies nine cognitive styles. Kogan (1976) distinguishes three types of models, performance-based, developmental (one

mode

of style is more "advanced" than the others), and value-neutral (neitherextremeofthespectrum is"better"). Most models are bipolar e.g.,

reflectivity-impulsivity(Kagan and Kogan, 1970), field dependence-independence (Witkin, Goodenough, &. Karp, 1967), con-vergence-divergence (Hudson, 1966), and cognitive simplicity-complexity (Bieri,

1961). Most oif the models are based on developmental theory and their measures

calibrated from studies of seven to eight-een year olds. Cognitive style is seen as uncorrelated with intelligence, as

measuredbyIQ tests. Style istheresult of divergentpsychological growththat results

in consistent, differentiated traits and strategies.

Almost all the MIS research on cognitive style falls into the followingcategories in

termsofconceptualbase:

1. the Witkin field

dependence-inde-pendence model

2. the converger-diverger construct (Hudson)

There is substantial overlap among the models and, frequently, the labels they employ. The use of bipolar constructs is

common.

Most MIS studies constrast an analytic or systematic style with an oppositeone: intuitive or heuristic (Huys-mans, 1970; Barrett, 1978). Most use ad hoc measures, or adopt tests from other sources. Table 2 lists examples. As ex-ploratory research, this strategy is ac-ceptable. Huysmans, Doktor, and Keen(1973), for example,were mainly concern-ed with demonstrating the value and appli-cability of the cognitive style paradigm;

measurement was a secondary issue. The

lack of valid measures, however, surely explains why there has been no follow-up to theirwork.

Many

of the bipolar models provide noreal conceptualdiscussion. Eventhosebased on Witkin and theEFT

focus on experimental data rather than on underlying theory (Dermer, 1973). More importantly,regard-less of the labels used, most of these models can besubsumed intoHudson's con-verger-divergerframework.

If the

EFT

is a measure in search of atheory (Zigler, 1963) Hudson's formulation isthe reverse.

He

uses a variety of pencil-and-paper tests which do not have clear norms. There isnodiscussion ofconstruct, discriminant, or convergent validity, buthis book Contrary Imaginations,is stimula-tingandrich ininsight andimplication. It

is hard to see how any existing analytic/ heuristic model not based on Witkin or

Hudson adds to either our conceptual or

empiricalunderstandingof cognitive style.

3. cognitivecomplexity theory

4. theMBTI

Table 2 summarizes the main definitions and measuresineach category.

Cognitive complexity theory and construct theoryare not modelsof style but address the same overall issues. They are Type I

models (performance-based) using Kogan's distinction. Complexity is better than simplicity (Witkin's model also falls into

Table 2. Definitions and Measures of Cognitive Style Categories

Field

Dependence-Independence

Focuses on perceptual behavior, an individual's ability to

analyti-cally isolate an item from its content, its field. Field-dependent

people are likely to be particularly responsive to social frames of

reference (heuristic), while field independent people are more

analytic (Witkin).

Measures:

EFT (Embedded

Figures Test)Converger-Diverger

In convergent thinking the aim is to discover the one right answer.

It is highly directed and logical thinking. In divergent thinking

the aim is to produce alarge

number

of possible answers, noneof which is necessarily more correct than the others (Hudson).

Measures: ad hoc tests; creative uses ofobjects

Cognitive Complexity

Theory

Measurement ofthe

number

of dimensions individual employ incon-struing their social and personal world. Individuals at the

com-plexity end of the spectrum will differentiate greater

numbers

ofdimensions than wUl those at the simplicity end ofthe spectrum.

Measures: performance -basedtest; paragraph completion

MBTI

(Myers-BriggsType

Indicator)^

Looks at the

ways

people prefer to perceive and judge their world.Categorizes sixteen psychological types.

A

person's overallpsycho-logical type is a result oftest scores received on each ofthe four spearate preferences (introvert or extravert, sensing or intuitive,

thinking or feeling, judging orperceiving).

Larreche (1974), Carlisle (1974), and Stabell (1974) used complexity theory in

their studies of Decision Support Systems, drawing on Bieri (1961) and Schroeder, Driver, and Steufert (1967). Their work

has not been followed up, mainly,

we

deduce, because of the gapbetweenpara-digm and measure. Schroeder, et. al's. Paragraph Completion test lacks psycho-metricvalidity.

Wade

(1981) and Taylor and Benbasot (1980) provide comprehensive critiques of research in all four categories. Table 3summarizes our

own

assessment of thevalidity of thefirst threecategories using Bagozzi's classification. Ofcourse, it must

be shown thatthe fourthcategoryof

cog-nitive style research, based on the MBTI,

does not suffer the same inadequacies. This will be done in the fourth section of

this paper. The points to be

made

here are:1. There is a consistent gap between

paradigm and measure in the MIS

cognitivestyle research.

2. Themeasures arelargelyadhoc.

3. The bipolar constructs are

redun-dant and can be subsumed into

either Witkin's or Hudson's frame-works.

Other general criticisms can be added; testsof analytic-heuristic stylescorrelate poorly (Vasarheiyi, 1977; Zmud, 1978), as do those measuring cognitive complexity (Stabell, 1974). Worse, the experimental results are generally uninteresting or inconsistent (Taggart and Robey, 1979). This isespecially true of studies using the

EFT

(Taggartand Robey, 1979).CONCEPTUAL

AND

PSYCHOAAETRIC

ISSUES

McKenney

and Keenpresenta two-dimen-sional model ofcognitive style (1974) thathas

many

overlaps with other models and that suffersfrom several of theweaknesesdiscussed above. It is briefly described here sincework byKeen (1973)and subse-quent unpublished surveys confirmseveral points central to the argument of this

paper:

1. The psychometric issues in

devel-opment and application of

paper-and-pencil tests are immense and must be avoided by the use of

~

established,notad hocmeasures.

2. The analytic/heuristic and sys-tematic/intuitive dichotomies re-flect a more general converger/ divergerdistinction.

3. The MBTI is as good or better a

method for measurement as the

elaboratesetof testsused byKeen

(1973).

4. As

Wade

points out, "whileMcKenney

and Keen claim that a cognitivestyle is different from a personality type, on the surfacetheir construct would appear to have a lot in

common

with the Myers-Briggs sensing/intuition and thinking/feelingdimension"(1981).Wade'scriticism is legitimate. Eveninhis

initial study (1973), Keen found that the

MBTI discriminated certain aspects of style better than the batter of tests he used forthe main study. Thesetestswere

cumbersometoadminister(I and 1/2hours

plus I hourto score),and providedsubjects

withlittleuseful feedback. Therewere no

population norms, and cutpoints were

situotionally selected. In later studies

Keen found thatwhile the overall correla-tions

among

the tests were similar fordifferentpopulations, absolute scores were distorted by factors of speed and recent experience withtest-taking.

Table 3.

An

Assessment ofthe Validity of CognitiveStyle Paradigms in MIS

Table 3. (Continued)

Type which Mason and Mitroff present is

veryclose to theaims and conceptsof the

McKenney-Keenmodel. Subsequent

exper-iments involving junior college students, managers, and MIS professionals confirm the authors'viewthat themodel is redun-dant. While it still seems correct in its

overall formulation, thesubstitution ofthe

MBTI providesreliability and easeof

mea-surement and adds nomological validity, since the philosophic base and empirical application of the MBTI analytic/sys-tematic and heuristic/intuitive dichotomy

.rely on similar definitions and methods,

they too can be subsumed into the MBTI

which adds an essential perceptual dimen-sion to theirsimple oneofproblemsolving.

cerned with the conscious aspects of per-sonality, especially how people take in

in-formation andhow theydecidewhat todo with it. Heassumesthat muchapparently

random variation in humanbehavior is

ac-tually orderlyandconsistent. Jung distin-guishesbetweentwo opposite modes:

I. "FindingOut"

Sensing; preference for known facts:

reliance on concrete data and

experi-> ence

Intuition: looking for possibilities and

relationships; focus on concepts and theory

Ifcognitive"style,"asmost MIS research-ers seem to intend, is to be viewed as value-neutral,the performance-basedType

I models giso seem less acceptable than

ones that equate style with personality type. Nisbett and Temoshok (1976) and

Maccoby andJacklin (1974)

make

a strongcase that Type I models are completely

invalid; they really measure "performance

on a simple task or narrow set of related tasks"(NisbettandTemoshok, 1976).

2. "Deciding"

Thinking; judgments are based on

im-personal analysisandlogic

Feeling; judgments are based on

feel-ingsand personal values

Mason and Mitroff (1973) relate the

Jung-ian scales specifically to information sys-tems:

THE

MYERS-BRIGGS

TYPE

INDICATOR

(MBTI)There is ahuge literatureonthe MBTI.

A

1980 bibliography (CAPT) lists almost 600 references,many

ofwhich relate to educa-tionand occupationgi choice, especially in medicine (McCauley, 1977). Theinstru-ment wasdeveloped in the I940's through

I960'sbyI.Myers. Ithasbeen continuously

refined since then;theCenterfor Applica-tions ofPsychological Typeat the

Univer-sity of Florida built a database of over 75,000subjectsbetween 1970 and 1976 and

carried out a number of longitudinal

stud-ies.

The MBTI is based on Jung's theory of Psychological Type (1923). Jungwas

con-Each of these types hasa different conceptof"information," andthis is important for MISdesign. If oneis a pure Thinking type, information

will beentirelysymbolic,e.g.,some

abstractsystem, model,or string of symbols devoid of almost any

em-piricalcontent. If one is a Sensa-tion type, information will be en-tirely empirical, devoid of almost any theoretical content. Thus, Sensationtypesspeakof"rawdata," "hard facts," "numbers." For

Intui-tion types, information will be in

the form of "imaginative stories," "sketches of future possibilities." Information for Feeling types takes the formof "art," "poetry,""human

drama," andespecially "stories that

component." What is information

for one type will definitely not be information for another. Thus, as designers of MIS, our job is not to get (or force) all types to conform

to one, but to give each type the kind of information he is

psycholog-ically attuned to and will use most

effectively.

Jung definedtwoother dimensionsof type:

I. Relative interest in the outer ver-sus inner world: Introversion:

one's main interest is in the inner worldofconcepts and ideas.

Extroversion; one is more involved with the outer world of people and things.

2. Dealing with the world around us:

Judging; "living in a planned, de-cided, orderly way, wanting to regulate life and control it"

(Myers, 1976).

Perceiving: "living ina flexible, spon-taneous way, wantingtounderstand life

and adapttoit."

This classification results in four indepen-dent dimensionsand,hence,sixteen types:

El: Extroversion(E)-Introversion(I)

SN: Sensing(S) -Intuition (N)

TF: Thinking(T) -Feeling(F)

JP: Judging(J) -Perceiving(P)

An

ENFJ, for example, isextroverted,in-tuitive,feeling,andjudging.

The MBTI is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 126 forced-choice questions

(Form G). Shorter versionshove been used

by Mitroff, Slocum (1978), Kilmann and Taylor(1974).

Results ore reported in terms of "prefer-ence"scores. Jungstressed that amature

individual can use the eight modes (four scales X two opposites) as the occasion demands, but that people have consistent preferenceforonepoleon each dimension. The strengthof thepreferenceis shownby taking a numeric score between I and 67.

Myers (1962) states "the letter is con-sidered the most important port of the score, as indicating which of the opposite sides of his nature the person prefers to use and, presumably, has developed —or

can develop—to a higher degree. ...The

numerical portion of a score shows how

stronglythe preference is reported,which is not necessarily the same thing as how

strongly it is felt...Each person is classed

in positive terms, by what he likes, not

what he lacks. The theory attaches no prior value judgment to one preferenceas

comparedwith another, butconsiders each

one valuable and at times indepensible in itsownfield."

Myers (1962) provides a detailed

descrip-tion of the construction of the MBTI, to-gether with data to support its validity.

Theonly technicalproblemsseemto be:

I. The

SN

&

JPscales are not ortho-gonal.t>/

.A'

TheTF

scalehashad to berecali-\/ ) brated to reflect the fact that

-^ "feeling responses

may

be moreacceptable or popular

among

younger Americans than theyweretwenty years" (Myers, 1976). (See alsoStriekerandRoss, 1964.)

Split-half reliabilities in samples of high school and college students (N= 26to 100) are inthe.80range, andmedian item-type tetrachroniccorrelations.61 (N=

MOD

forIIth and 12thgraders and .48 for 4th and

5th (N = 264). The indicator has been subjected to a strict series of internal consistency analyses, mainly using large samplesof adults. Checkson internal and

longitudinal validity have beencarried out that suggest that the MBTI is reliable (Buros, 1970;Lake,Miles,

&

Earie, 1973).The MBTI is designed to maximize accur-acy atthecenterrather than theextremes

of each index; this is consistent with the emphasis on the letter (E, I, S, N, etc.) rather than the score. The MBTI has no zero point; scores are converted by dou-bling the difference and adding or sub-tracting I, so that the final preference strength isalways an odd number.

The scoring method eliminates distortions caused by students omitting to answer questions and by social desirability re-sponses (Myers, 1962). Myers presents

substantial evidence to support thechoice of division points, e.g., between E and T, (Myers, 1962) to address criticisms by Strieker and Ross (1962) concerning cri-terion groups and the interpretation of regresssion results. It is central to the theoryof typethat the regressions reflect a dichotomy; i.e., that an E is different fromanI,SfromN,etc.

Thebest method thus found...is by plottingthe regression ofa depen-dent variable separately upon the

twohalves ofanindex.

...The crucial que.stion is whether the observed disparities in level

and/or slope...are better explained by the hypothesisof twodifferent populations(Myers, 1962).

One resultof thedichotomous construction and the consequent reliance on the letter rather than the score has been the very limiteduse of parametricstatistical

analy-sis in empirical MBTI research.

Many

studies report no tests of significance;most others use simple chi-square

statis-ticsor related indeces showing observedto expected frequencies based on large

sam-ples from Myers (McCaulley, 1976). This

obviously poses.problems of comparability and generalizationof results.

Masonand Mitroff seem to have been the

first to use the Jungian theory of type in

MIS and reference the MBTI. In later studies Mitroff and Kilmann (1975), and

Kilmannand Mitroff(1976)usea variant of the MBTIbutdonotreport detailed

statis-tics.TheBerkeley traditionof Churchman

and Mitroff focuses on thetheoretical and philosophical implications of the Jungian

framework(see alsodeWaele, 1978).

Keen (1973) and others explicitly inter-ested in empirical aspects of cognitive style (Henderson and Nutt, 1980) largely accept the labels of the MBTI with little

discussion oftheunderlyingtheory. Myers ineffectsanctions theempiricaluseof the

MBTI independentof Jungian theory: "the personality differences it reflects are not atall theoretical, beinga familiar part of everyday life. The theorysimplyoffersa set ofreasons forthem, which

may

ormay

not matter in a given context" (Myers,.

1962).

The important issue of the relation

be-tween personality "type" and cognitive "style" isdiscussed indeWaele,Mason and Mitroff, and Mitroff and Kilmann (1978). Kagan's distinction between performance-based and value-neutral models of style

seemsrelevant. Stabell makesthe telling

point that cognitive style is a theory of external behavior, (unlike cognitive

com-plexity theory which focuses on internal constructs). Wade,followingan exhaustive analysis of a 900-item questionnaire, grouped fifteen personality/cognitive

di-mensions intothree factors(varimax

rota-tion). These load heavily on MBTI scales

and derive a two-dimensional model of style thatissimilar to theMcKenney-Keen

model andto Hellreigeland Slocum's(1980) adaptationoftheMBTItoacognitivestyle paradigm. Wade's detailed explication is usefulandstronglysuggeststhatageneral model of style needstobe bi-dimensional.

not bipolar, and that the basic distinction

between information gathering and

in-formation evaluation (McKenney

&

Keen, 1974) istheoreticallyand empirically sound (Hellriegel and Slocum use exactly theselabels; Wade uses fact gathering and

in-formationprocessing).

EMPIRICAL STUDIES USING

THE

MBTI

The above discussion of the MBTI relates to steps I and 2 in the research sequence

describedinthefirstsection:

1. Define a conceptually meaningful paradigmof style.

2. Developa reliablemeasure.

This section focuseson the next step: es-tablish that the measurediscriminates be-havior relevant to theuseanddevelopment

ofinformationsystems.

Thisis oneofthe central overall hypothe-sesforcognitive styleresearch in MIS. It must be stressed that results using other instruments are equivocal (Taggart

&

Ro-bey, 1979;Taylor

&

Benbasat, 1980).MBTI results are generally reported in terms of letters 5, N, T, J, etc., and percentages (a group consists of

60%

S's,40%

N's). Thereis aneed forastandard-ized approach to presenting MBTI results (see the next section). In the discussion here, if significance levels are not shown, theywere not reported in the publication referredto.

TheMBTI letters will be used here rather thansuchcognitive style labels as analytic, intuitive, etc. The assumed relation be-tween the McKenney-Keen model and the

MBTI isinFigure I.

The overlapis not complete; the systema-tic-intuitive distinction and related ana-lytic-heuristic dichotomy is intendedly

broader thanthat of thinking-feeling. The

El scale has not been found in any MIS study to relate tocognitive style. The JP dimension is interesting in relation to oc-cupational choice (sixth section); it seems

to indicate a preference for structure as againstflexibility.

Ghani (1980)foundthatT'sandF'sdifferin termsofperformanceand time neededina reasonably complex decision making task using different information formats. T's

prefer and do better using tabular and F's

graphical displays(p <.0I). Ghani alsoused the EFT, but did not find any significant differences. Henderson andNuttsimilarly found thatT'sand F's differed in perform-ance in an operations management task.

Keen (1973) reports that cognitive

"spe-cialists," individuals previously identified

as marked systematics or intuitives,

showed predictable differences in problem

solving strategies and choice of task (p

<05); this isareclassification of the origi-nal data, using the TF scaleof the MBTI

instead of the original pencil-and-paper tests.

McCaulleyand Natter(1974)found

signifi-cant differences among types in terms of preferred learning activities. Sensing types"need experience with the real thing before learning the symbols verbal and mathematical)." N's prefer independent study. While these resultsdo not directly relate to information use,

many

ofMc-Caulley and Natter's conclusions seem

di-rectlytransferable totheMIScontext.

De

Waele(1978)reports a number ofrela-tionshipsbetween MBTI type and decision

makingprocessesinmarketing:

1. IP's report problems in "getting things done" and EJ's in handling

^

uncertainty.2.\ The N'senjoy problem finding and theS'sproblemsolving.

general, personal, and humanistic; their ideal organization hasa mis-sion toserve mankind.

4. SF'semphasize fact and precision,

human relations, and individual

rather than global values.

The work of Mitroff and his colleagues is

of particular relevance to cognitive style

in that it adds nomological validity. Not

only does the MBTi tap characteristics of individual information processing, but it

includes noncognitive dimensions that ex-tend the applicability of findings focused oncognitiveissues.

Scattered across the MBTI literature is a

massofmodest conclusions thatadd up to

very rich profiles. Examplesare shown in

Table k (no attributions are shown here, sincetheydrawonawealthof references).

COGNITIVE STYLE

AND

OCCUPATIONAL

SPECIALIZATION

The final component of the four steps for

research indentified inthe firstsection is: demonstrate that analysts and users of information systems differ significantly in termsof style. ThissectionpresentsMBTI

data acrossoccupations. Keen(1974) sug-gests that MIS research should focus on cognitive specialization rcther than cog-nitive style, since it is concerned with

people andjobs thatare notrepresentative of the overall population: managers,whose

mean

IQ's are i to 2 standard deviationsabovethenormof 100;management

scien-tists,whosetrainingandskills are unusual;

andfunctional specialists,whoare likelyto bringspecializedmodesof thinking to their jobs.

range of functions, skills, attitudes, and processes.

The data reported in this section focuson differencesincognitive styleinspecialized

jobs and among business functions and

levelsof management. Manyof the

sam-pleswerecollectedby theauthors, but the analysis draws on other surveys. The au-thors' samplesare not random. The stra-tegyhas been to locate as

many

specializ-ed occupational groupsas possible, partic-ularly ones that require special trainingandskills of analysis. Theauthors hadsix

overall hypotheses, several of which are almost axiomatic in the literature on

MIS/MSimplementation:

I. Intellectual fields wil preponderanceof N's.

contain a

2. Fields in which attention to detail and concrete action are key will

attractS's.

3. Technical specialists will tend to

beNT's,withfewF'sandS's.

4. Academics in a given field are

more likely to be P's than are

practitioners. (The assumption here, not well supported by the data, was that individuals prefer-ring a clear structure and orderly

work environment, J's, would be

more likelytochooseindustry than

academic).

5. Managerswillbe predominantlyT's

andJ's.

6. Individuals whose work involves close contact with others will

mainly beS'sandF's.

Cognitive style research often assumes thatmanagersaredifferent fromanalysts. That hypothesis does not seem to have been systematically tested. More impor-tantly, the term "manager" covers a wide

There is a distinct problem in choosing a

method for determining the significance

levels of differences between groups.

None of them are representative of the general population, in which the sixteen

MBTI types are not uniformly distributed.

McCoulley uses simple chi-square

statis-tics, comparing the percentage of type

(e.g., S's) in a subset of the population

against the overall data bank created and maintained at the University of Florida. Since we are interested inthe differences

between specialized groups and general

management we follow her method, but

substitute for her base figures a pooled

breakdown of the percentageof each type

among

Wharton (n=232). Harvard (n=l07), and Stanford (n=256) MBA's. This figurewaschosen as a reference point since the

MBA's samples are adequately large

(n=604).

There are no firm figures on the distribu-tion of MBTItypesacrossthe general pop-ulation. Myers calibrated

Form G

of the MBTI, by using 1,114males and 1,111 fe-males in grades4-12,

and validated itusing other, generallyadult,samples. The

Center for Applications of Psychological

Type (CAPT) has builta data bank of 75,

745 MBTI profiles collected between 1970 and 1976. (For this profile see

CAPT

baseline figures). This contains a large .numberof college students. The distribu-tion of typesissignificantlydifferentfrom that forMBA's. Most MBTIstudies

exam-inespecialized groups. Thelack of

popula-tion norms explains why

many

studies donot report significance levels. In some

cases, too, the raw data are no longer availableandonlyaggregate figureson the percentageofsubjects in eachMBTI cate-gory are available. This obviously limits statistical analysis. This weakness is off-setbytherangeofsamplesforwhichsome

information is available. It is only where

the issue is the statistical significance of the distribution of types in a particular group that MBTI research is limited to nonparametric analysis. Studies that re-late theMBTItoothermeasures use multi-variate techniques, including regression andfactor analysis(e.g.,Wade).

Table 5 summarizes the distribution of

MBTItypesacross various fields(Appendix

A

indicates the sources; the authors'sam-ples aremarkedwithan"x").

Some

ofthe samples are very small; one problem instudying specialized occupations is that people in them are hard to locate andare notubiquitous.

Some

general points are obvious fromTa-ble5. TheS's skill isingetting thingsdone

andthe N's inthinking things up. TheS is

a decision maker and heavily attentive to detailed facts(accountants,bankers, senior executives, judges). In intellectual,

scien-tific, and creative fields N's dominate.

There is a clear-cut relationship between

intellectual attainment and the SN scale.

Among

non-college prep high school stu-dents14% are N, forcollegeprep42%,andamongnational meritscholars

83%

(Myers,1962).

The differences across occupational

spe-cialities are marked. For example,

ac-countants and sales/customer relations personnel areentirelydifferent intermsof the

TF

dimension (73% versus 11%). Sur-prisingly, senior executives differ from middle managers and MBA's on theSN

dimension. Senior executives are much more concrete and good at getting things doneversus thinking things up. This resultis based ona limited samplebut is impor-tant in its implications if it can be con-firmed withlarger surveys. Six hypotheses

werelistedabove; theresultsarediscussed

below.

Hypothesis _[: Intellectual fields will co-ntain a preponderance of N's. This is

clearly confirmed. In the technical fields

listed, N's constitutea majority; in

scien-tific and intellectual fields, theyare

gen-erally

90%

of the total. Oneofthe seven scientific and intellectual fields issignfi-cantat the.01 level,andfour are

signifi-cantatthe.001 levelforN,usingthe

MBA

•ITIt IM CO 001^ COloo|o t-1 enII i-l|05| I 00 I I t-.-1

o

CO t-liHlesio

CO in IS 15 CO CO COOQ CO 05'I tx3r~-loolooI •I «oh

bl

II IfticoI •I 00|t>.I a bo « C.5 Pi O;:3 ' '^ QJ *i o c 0)X3 OK

W U

3 G O 0) *^ 0)'§

0) v •a -o-S <u M CC O33 3 o w OO

00Hypotheses2: Fieldsin whichattention to detail and concrete action are key will

attract

S^

This hypothesis is also sup-ported. Inbusiness function areas, S's are in the majority among accountants, bank employees, and sales/customer relations. Marketing managers, management consul-tants, MBA's, and middle managers are mainlyN'sbycontrast.The sample of senior executives is small (119) and consists of attendeesat a Stan-ford University Executive program. The

differences between this group and the

MBA's on theS/N dimension is significant

(p <.00l). In addition,Hoy's(1979)sample

ofowner/managersofsmall firms inTexas

shows an even stronger proportion of S's

(86%), also significant at the .001 level.

However, in asmaller sampleof 44

Geor-giaowner/managers, he found

48%

were S.This

may

berelated to differences in edu-cationlevelbetweenthetwogroups.The explanation for.the unexpected

fre-quencyofS's

among

topmanagersseemsto be that the N's style is well-suited tohandling complexity. Managers have to handlearangeof functions, planning, fore-casting, analysis, and control, while the senior executive is better at dealing with facts and getting things done.

A

large organization includesmany

professionaland academic disciplines: economists,

computer scientists, human resource

plan-ners, lawyers, and even historians. Inte-grating their activities requires the N's willingness to play with concepts and use theoretical frameworks. However,

some-one has to eliminate, not add, to this

complexity anduncertainty. TheS'sskillis

getting things done, demanding the facts and only the facts. S'shold that "matters inferred are not as reliable as matters explicitly stated" (Myers, 1980). The top executive's profileis veryclose to that of state judges who are decision makers par excellence and whose currency is "fact" (Keen, 1981).

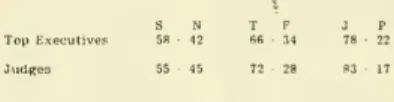

TopExecutives JlldRCS

In contrast tosenior executivesand judges all the technical and professional fields in Table 5 are mainly N's in predominant style;so, too, are most of the managerial ones. There is almost no difference in percentN'sbetweentheMBA's, usedasthe base for comparison, and Bell Labs Super-visors,management scientists,office auto-mation, and data processing professionals.

Theonly difference on the S/N dimension in these populations is thedata processing professionals have stronger

N

scores than the MBA's (p<i05). Theoperating assump-tion thatanalystsare different fromman-agers (Grayson, 1973) seems too broad;

both are N's. Leovitt's criticism (1975) that both technical specialists and

manag-ers are analytic in focus seems more ac-curate. However, the difference between

managers/analysts (N's) and senior execu-tives(S's) is significant at the .001 level.

ItappearsfromTable5 that theproblem in Mutual Understanding (Churchman and Schainblatt) between analysts and

manag-ers will be most marked at top levels of

the organization and in functional areas involving concrete dataand action. Level ofeducation isobviously a relevant factor.

The percentage of N's in any group is

correlated with educational level (Myers,

1962). Wharton undergraduatesare

28%

N

andWhartonMBA's 65%.

Among

industry-hired college graduates (Myers, 1962)

50%

areN's; thiscontrasts with the

68%

fortheMBA

population. The strikingly large fraction of S's (86%) in Hoy's sample ofowner/managersof smallfirms

may

reflect differingeducation levels. Thesubjects inhis sample where S's are 48%, were at-tendeesatacontinuingeducation courseat theUniversityofGeorgia.

highly educated:

many

of them have ad-vanceddegrees. Thus, while the executive sample is not random but a "convenience" one,educationlevel isnot a likely explana-tion of executives' substantial difference fromothereducatedmanagers. This resultis suggestive only arid needs confirmation from more systematic sampling; if it is confirmed, ithassomeinteresting implica-tions.

1. Top managers on the average are

not just promoted middle

manag-ers, but individuals whose con-creteness, pragmatism, and

em-phasis on getting thingsdonemake

them stand out from the middle

managers and MBA's whoaremore

focusedon concepts andplanning.

2. Analysts and top managers could hardly differmore interms of

how

theyviewdata.3. The top manager's view of the world is relatively narrow and un-sympathetic to the theories and

methods of the analytic decision

sciences.

Hypothesis 3: Technical specialists will

tend tobe NT's withfew F's andS's. This

restates a basic assumption of cognitive style research: the analyst's preference and skill are in concepts and systematic thinking. Intechnicalandscientific fields,

about

70%

are T's. This is roughly thesameforbusinessfunctionsand managerial

levels,including senior executives. Again,

this suggests that analysts and managers

are not as different as the implementation literatureassumes. Contrasts to the

ana-lysts

come

by looking at the servicepro-fessions(counseling,education,and health-related) and intellectual fields where F's

predominate.

The authors

make

the conjecture that the claim that a sizeable faction of managersoperate "intuitively" is misleading. The

intuitive strategy described by

McKenney

and Keen is close to the F's mode of thinking; this is intellectually complex, highly verbal,andrelies on analogy (Keen, 1973). Writers, Rhodes Scholars, theo-logians, college teachers, and educators areF's.De

Waele's study of marketing managershighlighted the role of experience in de-cision making. S's are highly pragmatic andaction oriented; they distrust abstrac-tions.

We

suspect that it is theS's among managerswhospeakof "gut feel"andthat thegapinmutual understanding isoneof S versus N: reliance on experience versus concepts. Myers discusses mutual under-standing. Type, and marriage, and argues that theSN

scale relates to seeing things thesameway: "Thisdoes more tomake

aman

andwoman

understandable to each other thanashared preference onEl orTF

orJP." Ourdataalsosuggestthatbecause the S/N dimension is most different be-tween managers/analysts and senior exec-utives, it is most likely to cause differ-ences in understanding between the twogroups. TheT scale seemsto offer little,

ifany,discriminatingpower inbusinessand technical fields.

Hypothesis 4: Academics will be more

likely to be P's than practitioners. This

hypothesis was not well supported except

for de Waele's small samples of manage-mentscientistsand academics:

J's; theonlyexception being middle

mana-gerswhoareP's. Thefact thatthemiddle managers' P score disrupted the steady J

trendfor technicalandbusiness professions as well asacademics was initially

surpris-ing. However, further examinationof the

data causes the emergence of interesting significance levels. Most of the "practi-tioners" (seven out of the eleven profes-sional groups in technical business fields)

are significantly different from the

MBA

base population; that is, they are

signifi-cantly stronger J's (four at the .001 level,

one at the .01 level, and two at the .05

level) than the MBA's. The remaining

"practitioners" (industrial management

scientists. Bell Lab Supervisors, and bank managers)aswell astheacademicsarenot significantly different from the MBA's. There are at least two possible explana-tions forthisdiscrepancy:

1. The "weaker" J groups and middle

managers (P's)

may

work inenvi-ronments that demand less struc-ture than the "stronger" J's' envi-ronments and/or

2. the weaker J, as well as the P

groups,

may

becomprised of moreMBA's, thereby lowering the J score. Both explanations are con-jecture and will require further research. (Additionally,it requires that researchers request complete education backgrounds of subjects beingtested.)

Hypothesis 5: Managers will be predom-inatelyT'sandJ's. Thedata confirmsthat

mangers are predominantly T's. Middle

managers and senior executives were not

significantly different thanMBA'sontheT

scale, while manager/owners were

signifi-cantly stronger T's (p< .01). The data confirmsthatmanagers are predominantly J's. Seniorexecutives andmanager/owners

are mostly J's, significantly more so

(p<.00l)thanMBA's. However,themiddle managers' scores provide a discrepancy.

As previously stated, the middle managers

are P's, and differ significantly (p <.00l) fromthe MBA's. It isplausible that senior executives and managers/owners would prefer a more structured environment; it appears that the more a job involves de-cision making, the higher the fraction of

J's it contains. Thesenior executives are

83%

J's; they are closer to the judges inoverall profile than to other managerial

levels. Senior management is clearly a

field forJ's. However, MBA's are weaker

J's and middlemanagers are P's. Whether this is a result of less and/or different decision making responsibilityis inneedof furtherresearch.

Hypothesis 6: Individuals whose work

in-volvesclosecontact with otherswillbe 5*5

and F's. The data in Table5 support this

hypothesis. Itisnot surprising thatservice

professions (health, education, and

coun-seling), intellectual fields (creative

wri-ters,Rhodesscholars,and theologians)and

college teaching attract F's. However,

limited information and limited samples

make

formal testsof significance notpos-sible. It is also not surprising that the

sales/customer relations profession, the group in the business field who has the

most people contact, is mainly F's. The

virtual absence of technical and

manager-ial fields inwhichF'sareamajority limits

comparison. It is, however, obvious that theworldof MIS, intermsof development

and useof information systems,is not one inwhich

many

F'sare found.NT

managersandanalystshave

many

strengths. So, too, do the NF's who do not easily fit with them. Examples are shown in Table 6 (theseare taken froma range of sources, includingMyers, 1962and1980).CONCLUSION

The abovediscussion and data support the case for the MBTI as a general base for cognitivestyle research inMIS. It reason-ablymeetsBagozzi's tests of validity:

Table 6

including data on learning, occupa-tional, interpersonal behavior, organizational needs, and problem solving.

Many

other cognitive style models have both a limiteddomain of applicability anda

nar-row conception of cognition and behavior.

Wilkin's model of fieldindependenceisthe only otherwidely supportedalternate

para-digm forMISresearch. Thisisnota survey paper nor is there any wish to

make

the case for the MBTI at the expense of theEFT. The field independence model has

been widely applied in both MIS and ac-counting research (Lusk, 1973, 1979). Benbasat andhiscolleagues have usedit in

a series of experiments over a number of years. Since there clearly is no single cognitive style, the

EFT

and MBTI can peacefullycoexist. However, the general case for the Witkin model and measureneeds to be

made

in basically the sameterms as that for the MBTI in this paper.

Thevalidityofthe

EFT

needstobedemon-strated.

Taggart and Robey point out thatdespite criticisms of the

EFT

"the general docu-mentationof thetest'sdevelopmentleaveslittledoubt thata fundamental personality

construct underlies the measure (1979).

The issue is, "is this the construct MIS

researchisinterested in?"

The main arguments against the

EFT

inthiscontextare:

I. Conceptual validity; it isdifficult toseehowasimplebi-polar model

based onperformanceintasksthat focusonspatial skillcan

adequate-lycapture complexcognitive proc-esses.

A

major conclusion of this paper is the need for a two-dimensional construct that dis-tinguishes information-gathering and information-evaluation. The MBTI results showninTable 5sug-gest thateven twodimensions

may

notbe enough.In addition, cognitive "style" is a broad theory and the Witkin

measureanarrowone. Nisbettand

Temoshok review Witkin's and his

colleagues experiements (and Broverman's analogous model, 1964, of "automatization") and agree with Zigler, 1963, that "no concept more general than 'spatial

decontextualization' can be sup-ported by the data. "We are not

the first to view with alarm an

unwarranted overgeneralization in

theterms employedby Witkin and

his colleagues... (our)data are con-sistent with the demands of Witkin's critics for anarrower con-ceptionofhisconstruct."

Such a conception would not be a general model of cognitive style.

Amostnoneof the researcherswho

use the

EFT

discussthe underlying theory; the issue of conceptual validityisessentially ignored.2. Construct Validity; the

EFT

is a well established measure of fieldindependence. It isused in MIS as an indicator of "analytic" versus "heuristic" styles. There is no clear basis for substituting these labels (Zigler, 1963). The

EFT

and related instruments measureper-formanceonanarrowsetofsimple tasks. It seems inappropriate to usethescoresasgeneralindicators of style in experiments examining

complex problem solving behavior

and informationuse.

3. Convergent and 4. Validity; The

EFT

was initially designed for useamong

school childrenand college students of average ability. Thegraduate school subjects of most experiments in MIS using the

EFT

or group

EFT

score too highly to allow reliablediscrimination. Themaximum

score ontheGEFT

is 18;the reportmedianisaround I6,and

the average 13. Thedistributions areextremely skewed. Asa result, studies use a simple, arbitrary low-high dichotomy. This obviously limits discriminiation, and makes

any classification of a subject as "low analytic" or "heuristic"

unre-liable. The main advantageof the

EFT

is its simplicity. Itseemstoosimple. There is a lack of

statis-ticaldata tosupport any claim for

either convergent or discriminant validity in the context of MIS re-search.

5. Predictive Validity; Taylor and

Benbasat (1980) and Taggart and

Robey (1979) provide useful

sum-maries of experiments using the

EFT

inMIS. Theresultsaregener-ally equivocal and often contra-dictory. For example, Doktor and Hamilton's conclusions (1973) are inconsistent with Benbasat and Dexter(1978)and Lusk(1973) using

similar, clearhypotheses. In

many

instances, some factor other than cognitive style accounts for most ofthevarianceintheresults.

6. Nomological Validity. This seems

the most limitation. The MBTI

relates to a rich psychological model and to wealth of data on learning, occupations, interper-sonal behavior, organizational needs, etc. Witkin and his col-leagues have studied relationships

between field

dependence/inde-pendence and

many

of thesefac-tors. Their discussions of

inter-personal behavior (Witkin

&

Good-enough, 1977) and education

(Wit-kin,eta!., 1967)are thorough and useful. However, they do not re-late to the managerial and

organ-izational context of interest to

MIS. Whereasthere is a range of

MBTI data on managerialbehavior, occupational choice, turnover,

teamwork, values, and educational

level, the general validity of the

Witkin model rests on the results

of anumber ofsmall scale

exper-iments rather than large scale, heterogeneoussurveys. TheWitkin model is anarrow one andfar less

rich in its implications than the

MBTI. That is not necessarily a

weakness,butitmakesitseem less

suitablethan theMBTIforMIS;the

overallaimsofMISresearchinthis context aregeneral and ambitious; to establish that thepsychologyof individual differences is a major

explanatory factor for all aspects of information systems. Regard-less of empirical results, no paper withthe scope, bravura, and

intel-lectual depth of Mason and

Mit-roff's could be written around the

EFT, nor could Mitroff and Kil-mann's studyof idealorganizations be obtained from a low/high di-chotomy.

The overall case for

EFT

has not beenmade

as yet. If itcanbe, theEFT may

be better suited to studies of the psychology of individual cognitive differences whereperformance rather than preference or

behavioristhe focus of interestthan isthe

MBTI. Until the case for the validity of

the

EFT

ismade,however, itishardtosee that further, simple experiments around "analytic" and "heuristic" styles can be justified.The adoption of the MBTI as the central instrument for MIS research on cognitive style permits an integrated, cumulative research effort. That the cognitive style paradigm continues to interest a large

numberof MIS researchersdespite the

ob-viousflaws in and fragmentationof exist-ing efforts indicates its potential

impor-tance. The relationship between informa-tionand information-processor is obviously at the heart of MIS.

A common

andvalid construct andmeasure willmake

it easier to translate potential intoactual. Thiscan begin from the further consolidation and comparison of the results of existingstu-dies, especially in linking the data on

in-formation use and that on occupational differences.

A

systematicmethod for re-portingMBTlresultsisessential; theuseof letters and percentages is convenient and acceptable, but therehas been atendency to ignore statistical analyses in the MBTIliterature.

Once thecomparativestudies demonstrate that the two central hypotheses of the cognitive style approach are well-support-ed, a major aim of the overall research effortwillhave been accomplished. These hypothesesare simple:

1. Cognitive style differences have a major impact on information

sys-temsand implementation.

2. Managers and analysts are

differ-ent (or,if the arguments and data presentedin thispaperare correct,

some managers are different from

theanalysts).

Selectingavalidmethodforstudyingthem

hasnot been simple. The issueof validity has to be resolved. The MBTI seems to offeranexcellent solution.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Altemeyer, B. "Education in theArts and Sciences: Divergent Paths," Ph.D. Dissertation, Carnegie Institute of Technology, 1966.

Bagozzi, R. P. Causal Models in

Marke-ting,Wiley,

New

York,New

York, 1980.Barrett, M.J. "CognitiveStyle: An

Over-view of the Developmental Phase of a

Decision Process Research Program,"

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1978.

Benbasat, I. and Dexter,A. S. "Value and Events Approaches to Accounting:

An

Experimental Evaluation," TheAc-counting Review, Volume LIV,

Number

4,October 1979.

Bieri,J. "Complexity-Simplicityasa Per-sonalityVariableinCognitiveand Pref-erential Behavior," Fiske and Maddi,

eds.. Functions of Varied Experience,

Dorsey, 1961.

Broverman,D.M.,Broverman, 1.K., Vogel, W., Palmer, R. D., and Klaiber, E. L. "The Automatization Cognitive Style and Physical Development," Child De-velopment,Volume35,

Number

I, 1964. Bruner,J.S.,Olver, R.,andGreenfield, P. M. StudiesinCognitive Growth,Wiley,New

York,New

York, 1966.Buros, 0., ed. Mer\tal Measurement Yea-rbook,GryphonPress, 1970.

Carlisle, J. "Cognitive Factors in Inter-active Decision Systems," Ph.D. Dis-sertation, Yale,

New

Haven, Connecti-cut, 1974.Center for Applications of Psychological Type,June 1980.

Churchman, C. W. "Managerial

Accept-ance of Scientific Recommendations,"

California Management Review, Fall

1964.

Churchman, C.W. TheDesignof Inquiring

Systems,Basic Books, 1971.

Churchman, C.W. and Schainblatt, A. H.

"The Researcher and the Manager:

A

Dialectic of Implementation," Manag-ementScience,February 1965.Dermer, J. "A ReplytoCognitive Aspects of Annual Reports: Field Indepen-dence/Dependence," Empirical

Re-search to Accounting; Selected Stu-dies, 1973.

de Waele, M. "Managerial Style and the Design of Decision Aids," Ph.D. Dis-sertation, University of California, Berkeley,California,

May

1978. Doktor, R. H. and Hamilton,W. F."Cog-nitive Style and the Acceptance of

Recommenda-tions," Management Science, April

1973.

Ghani, J.A. "The Effects of Information Representation

&

Modification onDe-cision Performance," Ph.D.

Disserta-tion, Wharton School, University of

Pennsylvania,August, 1980.

Grayson, C. J. "Management Science and Business Practice," Harvard Business

Review,July 1973.

Hellriegel, D. and Slocum, J. W., Jr.

"Preferred Organizational Designs and Problems Solving Styles: Interesting Companions,"

Human

SystemsManag-ement,Volume2,

Number

2,SeptemberHenderson, J. C. and Nutt, P. C. "The Influence ofDecisionStyleon Decision

Making Behavior," Management

Sci-ence,April 1980.

Hoy, F. "Perceptions of Entrepreneurs-Implications for Consulting," Presented to the Third National Conference-Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, Phila-delphia,Pennsylvania,October 1979. Hudson, L. Contrary Imaginations,

Meth-uen,1966.

Huysmans,J.H.B.M. TheImplementation

of Operations Research,

Wiley-lnter-science, 1970.

Jung, K. Psychological Types, London, England,

WIT.

Kagan, J.and Kogan, N. "Individual Vari-ation inCognitive Processes,"P.

Mus-sen, ed., Carmichael's Manual of Child Psychology, Volume 1, Wiley,

New

York,New

York 1970.Keen, P. G.W. "The Implications of

Cog-nitive Style for Individual Decision Making," DB.A. Thesis, Harvard,

Cam-bridge,Massachusetts, 1973.Keen, P. G. W. "Cognitive Style and Career Specialization," J.Van Maanen, ed.,

New

Perspectives on Careers,1974.

Keen, P.G. W. "Cognitive Styles of

Law-yers and Scientists," Nyhart and Car-'

row, eds.. Resolving Regulatory Issues

Involving Science and Technology,

Heath, 1981.

Kelly, G. A. The Psychology of Personal Conflicts,Norton, 1955.

Killmann, R. H. andTaylor, V. "A Contin-gency Approach to Laboratory

Learn-ing: PsychologicalTypesversus Experi-ential Norms,"

Human

Relations,Vol-ume

27,Number

9, 1974.Kogan, N. CognitiveStylesin Infancy and EarlyChildhood,Wiley,

New

York,New

York, 1976.

Lake,P. G., Miles, M.B., andEarle,R.B. Measuring

Human

Behavior, TeachersCollegePress, 19/3.

Larreche, J. C. "Marketing Managersand Models:

A

Search fora Better Match," Research Paper SeriesNumber

157,TheEuropean Institute of Business

Admin-istration, 1974. .

Leavitt, H. J. "Beyond the Analytic

Man-ager," California Management Review,

Spring-Summer 1975.

Lusk, E. "Cognitive Aspects of Annual Reports: Field Independence," Empiri-cal Research in Accounting: Selected Studies, 1973.

Lusk,E. "A Test ofDifferential

Perform-ance Peaking for a Desembedding

Task," Journal ofAccounting Research,

Spring, 1979.

Maccoby, E. E. and Jacklin, C. J. The

Psychology of Sex Differences,

Stan-ford University Press, Berkeley, Cali-fornia, 1974.

MacKinnon, D. W. "The Nature and

Nur-ture of Creative Talent," American

Psychologist, 1962.

Mason, R. 0. andMitroff, I.I. "AProgram for Research in Management,"

Manag-ement Science, Volume 19,

Number

5,W7T.

McCaulley, M. H. "Personality Variables: Model Profiles that Characterize Vari-ous Fields of Science," M. B. Rowe,

chair. Birth of

New

Ways to Raise a Scientifically Literate Society;Re-searchThat

May

Help, Symposiumpre-sentedat the meetingof the American

Association for the Advancement of Science, Boston, Massachusetts, Feb-ruary1976.

McCaulley, M. H. "TheMyersLongitudinal MedicalStudy,"CenterforApplications of Psychological Type, Gainesville, Florida, 1977. Monograph II, Contract

Number

231-76-0051,Health Resources Administration,DHEW.

McCaulley, M. H. and Natter,F. L. "Psy-chological (Myers-Briggs) Type Differ-ences inEducation," Natter andRollin,

eds., The Governor's Task Force on

Disruptive Youth: Phase II Report,

Tallahassee, Florida, Office of the Governor, 1974.

McKenney, J.L.and Keen,P.G.W.

"How

Managers' Minds Work," Harvard Busi-nessReview,May-June 1974.Messick,S. "The CriterionProblem in the Evaluation of Instruction: Assessing Possible, NotJust IntendedOutcomes,"

WIttrock and Willey, eds., The Eval-uation of Instruction: Issues and Pro-blems, Holt, Rinehart and Winston,

Mitroff, I. I. and Kilmann, R. H. "On

OrganizationStories:

An

Approach to theDesign and AnalysisofOrganization through Myths and Stories," Kilmann, Pondy, and Slevin, eds., TheManag-ementof Organization Design, Volume

I,Elsevier, 1976.

Mitroff, I. I. and Kilmann, R. H. "Stories

ManagersTell:

A New

Tool forOrgan-izational Problem Solving," Manage-ment Review,July 1975.

Mitroff, I. I. and Kilmann, R. H. "On Integrating Behavioral and Philosophi-calSystems: TowardsaUnified Theory of Problem Solving," Annual Series on Sociology,VolumeI, 1978.

Myers, I.B. Introduction to Type, Second

Edition,

CAPT,

1976.Nisbett,R.E.andTemoshok, L. "Is There an'External' CognitiveStyle?," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

Volume33,

Number

I, 1976.Schroeder, H. M., Driver, M. J., and Streufert, S.

Human

Information Pro-cessing, Holt, Rinehart and Winston,Inc., 1967.

Shouksmith, G. Intelligence, Creativity

and Cognitive Style, Wiley,

New

York,New

York, 1970.Slocum, J. W., Jr. "Does Cognitive Style Affect Diagnosis and Intervention Strategies of Change Agents?," Group

and Organization Studies, Volume 3,

Number

2,June 1978.Stabell, C. B. "Individual Differences in Managerial Decision Making Processes:

A

Study of Conversational ComputerUsage," Ph.D. Dissertation, M.I.T.,

Cambridge,Massachusetts, 1974.

Strieker, L. J.and Ross, J. "Some Corre-lates of a Jungian Personality Inven-tory," Psychological Reports, Volume

14, 1964.

Taggart, W. and Robey, D. "Minds and Managers:

On

the Dual NatureofHu-man

Information Processing andManagement," unpublished paper.

Divi-sion of Management, Florida

Interna-tional University,September 1979. Taylor, R.N. and Benbasat, I. "ACritique

of Cognitive Styles Theory and

Re-seearch," Proceedings of the First

In-ternational Conference on Systems, 1980.

Vasarheiyi, M. A. "Man-machine Planning Systems:

A

Cognitive StyleExamina-tion of Interactive Decision Making," Journal of Accounting Research, July

wrr.

Wade, P. F. "Some Factors Affecting

Problem SolvingEffectiveness in

Busi-ness,

A

Study of Management Consul-tants," Ph.D. Dissertation, McGill Uni-versity, 1981.Witkin,H.W. "Origins ofCognitiveStyle," M. Scheerer, ed.. Cognition: Theory, Research, Promise, Harper and Row,

1964.

Witkin, H. A. and Goodenough, D. R. "Field Dependence and Interpersonal Behavior," Psychological Bulletin,

Vol-ume

84,Number

4, 1977.Witkin,H.A.,Goodenough, D. R. and Karp,

S.A. "Stability ofCognitiveStyle from ChildhoodtoYoungAdulthood,"Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

Witkin, H. A., Moore, C. A., Goodenough,

D.R.,and Cox,P.W. "Field-dependent and Field-Independent Cognitive Styles and Their Educational Implications,"

Review of Educational Research,

Vol-ume47, 1977.

Zigler, E. F. "A Measure in Search of a

Theory," Contemporary Psychology,

Volume8, iJH'.

Zmud, R. W. "On the Validity of the

Analytic-Heuristic Instrument Utilized

in the 'Minnesota Experiments',"

Management Science, Volume 24,

Number

10,June 1978.Appendix

A. Sources ofDataReportedinTable 5Data Source

1. BaselineFigures

Center forApplications ofPsycho-

CAPT

logical

Type

Combined

MBA

SamplesKeen

&Bronsema

2. TechnicalFields

Engineeringundergrads

Engineering graduates

Data processingprofessionals

Officeautomation specialists Industrial

management

scientistsBellLabs supervisors

Myers

Meyers

Keen

&Bronsema

Keen

&Bronsema

deWaele

Keen

&Bronsema

3. Scientific Fields Sciencestudents Research scientists McCaulley

McKinnon

4. Intellectual Fields Creative writersRhodes

Scholars Theology Creative architects MathematiciansMcKinnon

Myers

Myers

McKinnon

McKinnon

"'•' li-83 ^y23'88 /\R 2 41986

Appendix

A

(continued) 5. Business(a) Functional Areas

Accountants

Bank

EmployeesSales/customerrelations

Bank

managersMarketing managers

.,0,^'i

^<^