MIT LIBRARIES 3

9080 02618 4603

I I ' .1,ma

f")\r'u,

ii/i i';ff

^itihf^ Ino

MM^*^'^^

DEWEY

MIT

Sloan

School

of

Management

MIT

Sloan

Working

Paper

4474-04

January

2004

Costly

Dividend

Signaling:

The

Case

of

Loss

Firms

with

Negative

Cash Flows

PeterR.Joos

and

George

A. Plesko©

2004 byPeter R. JoosandGeorge A.Plesko.Allrightsreserved.Short sectionsoftext,nottoexceed twoparagraphs,

may

be quotedwithoutexplicitpermission,providedthatfullcreditincluding

©

noticeisgiventothesource. Thispaper alsocan bedownloadedwithoutchargefromtheSocialScienceResearchNetworkElectronicPaperCollection:

!

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTEi OF

TECHNOLOGY

DEC

3im

Costly dividend

signaling:

The

case

of

lossfirms with

negative

cash

flows

PeterJoos

and

George

A. PleskoFirstDraft:

November

2003

ThisDraft:January

2004

Abstract

We

examine

the dividend-signalinghypothesisin asample offirms forwhich

dividendincreases are particularly costly,

namely

loss firms with negative cash flows.When

compared

tolossfirmswithpositivecashflows,we

findthepredictivepower

of dividendincreases for future returnonassetstobegreaterforlossfirmswithnegativecashflows, consistentwiththepredictive

power

ofthedividendsignalbeingstrongerwhen

itscostishigher.

Our

results provide support for the dividend-signaling hypothesisand

have broaderimplications sincelossfirms comprisea largeand

increasingshareof publicly-traded firms.Contactinformation:

Sloan Schoolof

Management

MassachusettsInstituteofTechnology

E52-325,

50

Memorial

Drive Cambridge,MA

02142-1347

Joos: 617-253-9459,

pioos@mit.edu

(correspondingauthor) Plesko: 617-253-2668.gplesko@mit.edu

Whether

firms signal futureprospectsthroughdividendchanges hasbeenasourceof

debateand

researchinthecorporate financeliteraturesince the earlypapersby

Lintner(1956)

and

Millerand

Modigliani(1961). Despite considerableresearch, thedebate overtheempirical validityofthedividend-signalinghypothesisremainsaliveintheliterature.

Nissim

and

Ziv (2001) present evidence consistent with the dividend-signalinghypothesis

by

showing

dividend increases (but not decreases) relate to fiiture profitability.However, two

recentpaperscome

todifferentconclusions. Grullonetal. (2003) arguetheresults inNissim and

Ziv (2001) followfrom

amisspecificationofthe earnings expectationsmodel

used topredictexpectedearnings.They

find theevidence supportingthedividend-signalinghypothesis disappearswhen

theearnings expectationsmodel

accounts fornon-linear patterns in the behaviorofearnings.' In amore

generalreview of dividend policy. Skinner (2003) concludes structural changes in dividend

policy

and

thenatureofcorporateearnings over timeruleout signaling,atleast inrecentdecades.

He

finds dividends havebecome

toosmooth and

earnings too volatile fordividendchangestobe an informativesignal for futureearnings changes.

Although not conclusive, this recentempirical evidence appears to be

moving

towardsrejecting the dividend-signaling hypothesis.^ Inthispaper,

we

contributetothedebate with a different approach to test the dividend-signaling hypothesis. Instead of

examining

dividend behavior for all firms in the market,we

examine

thedividend-signalinghypothesisina setting

where

useof dividendstosignalisparticularly costlytothefirm.

Spence

(1973) argues the cost of sending aneconomic

signal determines itsincrease their dividend

payment

(i.e., cash outflow) while experiencing current lossescaused

by

negativecash flows.^We

arguethat, since investorscanreadilyobservethe current loss and its components,management

will need to send a strongand

credible signal to convincemarketparticipants thatperformancewillimprove.We

assume

thatincreasingcash dividendsatatimethefirmhasanegativecash flowconstitutes astrong

and

costly signal offuture performance fortwo

reasons. First, the increase in currentcashdividendswillimmediatelyaffectthe liquidityofthefirm. Second,anincrease in

thecashdividendimpliesa strong

commitment

tomaintainthehigherlevelof dividendsinthefuture,given previousstudies

document

areluctanceofmanagers

tocutdividends(e.g.,Lintner1956

and

Brav

etal.2003).We

testour hypothesisby comparing

thepredictivepower of

dividendincreasesbetween

loss firms with positiveand

negative cash flowcomponents

for futureperformance.

We

collectasample oflossobservationsfrom 1970-2001and

testwhetheradividendincreaseprovides incremental informationinpredicting firms' return

on

assetsbeyond

thatcontainedincurrentearningsand

anumber

ofcontrol variables.Our

main

resultsshow

that, condifioningon

cash flows, the signalingpower

of dividendincreases for loss firmsexistsonlyfornegativecashflowfirms,consistentwiththehypothesisthatthecostlierthesignalisthe

more

informationitcontains.We

verifyour

main

results in additional analyses focusingon

subsamples offirms with multiple losses forwhich

increaseddividend pajmientsareincreasingly costly,and

on

augmented

specificationsof ourbasicmodel.

Although

some

resultsareconsistentwithalossbeingsufficient for adividendincreasetoimproveforecastsoffuturereturns irrespectiveofthe sign of the cash flow, all robustness analyses demonstrate the predictive

power

ofdividendincreasesislargerforloss firmswithanegativecash flow thanforlossfirms

withapositivecashflow.

Our

study extends the dividend signaling literatureby

identifying a particularsegment

of firms forwhich

we

hypothesize the decision to increase dividends isparticularly costly. Consistent with Spence'scriterion for informative signals,

we

finddividends helptopredicta firm'sfiitureperformance

when

thedividendsignaliscostly.We

also extend previous researchon

the relationbetween

lossesand

dividendsby

focusing

on

the particularquality oflosses thatrenders the dividend signal costlyand

credible,

namely

thecashflowcomponent

oftheloss.In thenextsection,

we

discuss relatedresearchand

motivateourstudy. InsectionII

we

provide descriptive statisticsof

thesample

and

present our empirical model.SectionsIII

and

IV

containourmain

resultsand

theresults of robustnessanalyses.We

concludeinafinalsection.

I.

Background

and

motivationTo

testthedividend-signalinghypothesis,we

evaluate the predictivepower

of anincrease in cash dividendsforfuture firmperformance ina sample

of

firms thatreport current losses.We

argue the cost of the dividend signal will determine its informativeness and distinguishbetween

losseswith a negative versus a positive cashflow

component

tocapture thedifferentialcostofthedividendincreaseacrossloss firms.We

arenot thefirsttoinvestigate the relafionbetween

dividendsand

losses.LikeDeAngelo

etal. (1992) [hereafter,DDS],

we

focuson

loss firmsto studythe dividend-signaling hypothesis,arguingthatdividendswill have informationcontentwhen

currentearnings areanunreliable indicatoroffutureprofitability,

and

thatlossesprovidesucha specialcontext. In asample of 167firmsovertheperiod 1980-1985,DDS

show

alossisa necessary, but not sufficient, condition for a firm to decrease dividends.

They

find firms that decrease dividends experiencemore

severeand

more

persistent losses than firmsthatdo

not.Further,unusualincome

items(e.g.,specialitems) area larger factorinthe earningsoflossfirmsthat

do

notreduce dividends thanofthefirms that do. Focusingexplicitly

on

dividend signaling, they find dividend decreases provide incremental informationtopredict futureearnings,althoughtheirforecastingpower

diminishesinthepresenceof unusual

income

items.Using

a larger sample over a longtime period. Skinner (2003) finds thatwhen

firmspayinglargedividends experiencealoss,the lossis

more

likelycausedby

special items,and

more

likely toreversethana lossreportedby

a firmthat does notpay

large dividends. In related work, Joosand

Plesko (2003)examine

a largesample

oflossfirms,

and

thetiming oflossreversals.They

show

the lossesoffirms thatcontinuetopay

dividendsare

more

likely toreverse thanthose of non-dividendpayingfirms,and

thateliminating adividendisassociatedwithadecreaseinthelikelihood the loss will reverse

inthe

immediate

future.^We

extendthis lineofresearchby comparing

whetherincreasesincash dividendsby

loss firms signal future performance betterwhen

negative cash flows rather than negative accruals drive theloss.Whereas

previousresearch focuses specificallyon

the role ofspecial itemswhen

studying the relationbetween

dividendsand

losses,we

differentiate

between

losseswitha positiveand

negative cash flowcomponent

tocapture therelativecostofthe decision to increasedividend cashoutflows.The

evidenceinJoosand

Plesko (2003)showing

losseshave

become

more

persistentinrecent years,oftendue

to persistent negative cash flows, emphasizes thepotential cost of an increase in cash dividendsforlossfirms.

The most

recent paperson

the dividend-signaling hypothesis find a reducedsignaling rolefor dividendsovertime, consistentwithfindingsthatfirms have

changed

their dividend-paying behavior (see Skinner

2003)7

In light ofthe evidence ofthereducedsignaling role of dividends ina general cross-sectional time-series context,

we

complement

theliteratureby

focusingon

anarrowersettingthatprovidesa powerfiiltestofthedividend-signaling hypothesis.

II.

Sample

constructionand

descriptivestatisticsOur

sample

consists of firm-yearobservationsfrom

Compustat's Industrialand

Research

Annual Data

Basesfortheyears 1971-2000. ConsistentwithHayn

(1995)we

defineour earningsvariable as

income

(loss)before extraordinaryitemsand

discontinuedoperations or

IB

(annualCompustat

data item #18).We

definetwo main

variables tocapturedividend

payments by

the firm.We

defineDIVCF

asthetotaldollaramount

of cash dividends paidby

the firm (annualCompustat

data item #21).^We

focuson

(changesin) thetotal

amount

paidratherthandividends persharetobeconsistent with ourview

thatthetotaldividend cash outflowestablishes the cost to afirm alreadyfaced with bothalossand

a negativecash flowina particular year. Sinceitispossiblethatthedividend cash outflow in a particular year increase without dividends per share being

affectedifthefirm's

number

of outstandingshareschanges,we

define asecondvariabledataitem#25).

TableIpresents descriptiveinformationforthesample. Panel

A

shows

ourinitial samplecontains206,420 firm-year observations: 146,394profitobservationsand

60,026loss observations

(29.08%

ofthe total).The

panel flirthershows

a relationbetween

dividend

payments and

loss occurrence: consistentwith the evidenceinSkinner (2003)we

find dividend-paying firms are less likelyto incur losses than non-dividend-payingfirms. Focusingfirst

on

thedividendpayments

of ourfirm-year observationsintheyearprior to the current observation,

we

observe 117,618 firm-year observations withno

dividends

and

88,802 firm-yearobservations with cashdividends.Of

thefirms thatpay

no

dividends44.43%

incur a currentloss;by

contrast,ofthedividend payingfirmsonly8.74%

incur a currentloss.The

contrastbetween

dividend-payingand

non-dividend-payingfirms

becomes

sharperwhen

we

focuson

thecontemporaneous

relationbetween

dividend

payments and

firm profitability: ofthe firm-year observations not paying a dividend,45.90%

have acontemporaneous

loss,compared

to only6.69%

offirms currentlypayingdividends.Panel

B

provides adescriptionof dividendchanges occurringin our sample. In theftiUsamplethemajorityoffirmsneverchange

theirdividend payments:measured

astotal cash outflow (or per share)

56.49%

(54.40%) offirm-year observationsdo

not change dividends in a given year,33.00%

(28.85%) increase dividends, and10.51%

(16.75%) decreasedividends.

The

percentageschange significantlywhen

we

partition the samplebetween

profit and loss firm-year observations: profitable firms increasedividends

payments

farmore

oftenthanlossfirms.By

contrast,the largemajorityofloss firmsdo

notchange

theirdividendpayments (86.98%

or86.04%

dependingon

whetherwe

measure

dividendsastotal cash outfloworpershare).The

high percentagereflectsthefactthatlossfirms are less likelyto

pay

dividends,andthatonlyasmallfractionoflossfirmsthat

pay

dividendsincreasedividendpayments (4.20%

or3.80%

dependingon

how we

measure

thedividendvariable).Panel

C

in Table I cross-tabulates ourtwo

measures of dividend changes.The

diagonal percentages in panel

C

show

that in the vast majority ofcases both proxiesreflectthe

same

directionof dividend change.However,

changesinthenumber

ofshares outstanding, with or without a constant dividend per share, can lead to non-zerooff-diagonalpercentages. For example,

we

observethat in20.54%)ofcases firm'stotalcash dividendpayments

increaseina particular year, yet thedividend pershare variableshows

adividenddecrease.

Such

a combination istheresult of an increasein thenumber

ofsharesinthe

same

year (e.g., as a resultofequityissuances orstock optionexercises).The two

variablesthereforecomplement

eachother asproxies fordividenddecisionsby

management.

While

we

focus primarilyon

the dollarvalueof dividend payments,sinceit best captures the

amount

of cash the firm is using,we

present results using bothvariables toillustratethesignaling roleof dividendincreases.

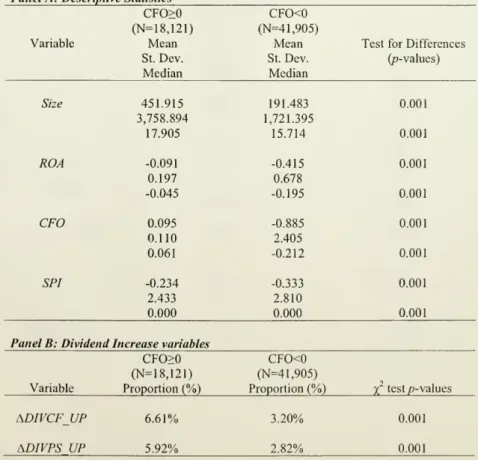

In Table II,

we

present evidence for ourmain

variables ofinterest. Sincewe

hypothesizethatthesignofthecashflowcomponent

of negative earningswilldeterminetherelativecostofadividendincrease

we

presentourdescriptivestatistics forasample oflossobservations partitionedby

thesignofthecashflowcomponent

ofthelosses.We

define the cash flow

component

of earnings(CFO)

as cash flow from operations,measured

asnetincome

(annualCompustat

dataitem# 172)lessaccruals.We

measure

(data item #5)

+ ADebt

in Current Liabilities (data item #34)+

Depreciationand

Amortizations(dataitem#14).Panel

A

of TableIIshows

themean,

standard deviation,and median

for four variablesofinterest. First,we

define Size asmarket value ofthefirm (stock pricetimesthe

number

of outstanding shares, orannualCompustat

dataitem#199*data item #25).Second,

we

defineROA

as earnings before extra-ordinary itemsand

discontinuedoperations (or

IB

asdefinedbefore) scaledby

laggedtotalassets{TA, annualCompustat

dataitem#6). Third,

we

defineCFO

asbefore. Finally,we

includeSPI, or specialitems (annualCompustat

data item #17) scaledby

lagged assets {TA,.i), in the Panel sincepreviousresearch singles out

SPI

asthe specificcomponent

oflosses relatedtoboththe qualityoflosses(i.e.,degreeofpermanence)

andthe dividend-payingbehavioroffirms(Skinner2003).

Panel

A

reports significant differencesbetween

themeans and medians

ofthetwo

subsamples (based

on

two-sided t-testsand

two-sidedWilcoxon

tests forthemean

and

median)

asafiinctionofthesignoftheircash flow component. Generallyspeaking, lossobservations with a positive cash flow are larger

and

exhibit stronger profitability(smaller losses)than loss observationswith a negative cash flow

component.

Positivecash flow loss firms

on

average also report less negative SPI, withboth types oflossfirmshaving

median

SPI of

zero though. Alldifferencesbetween

means and medians

arestatisticallysignificant.

Panel

B

of Table IIprovides descriptive statisticson

the incidence of dividendincreases in the sample ofloss observations as a functionofthe signofthe cash flow

thattakes the value of1 ifthe

change

in dividend cash outflow (dividend payout pershare)ispositive,

and

zero otherwise,withDIVCF

and

DIVPS

asdefinedbefore. PanelB

shows

a significantlysmallerproportionoflossobservationswithanegativecashflowcomponent

increases dividends, consistent with a dividend increase being costly:regardless ofthe dividend variable used, the percentage ofpositive

CFO

loss firms increasing theirdividendsismore

thantwicethepercentageof negativeCFO

lossfirms.Table11provides evidenceconsistentwithloss observations beingdifferentasa

fiinction

of

the sign ofthe cash flowcomponent

ofthe loss: a negative cash flowcomponent

suggests a greater deterioration in profitabilityand

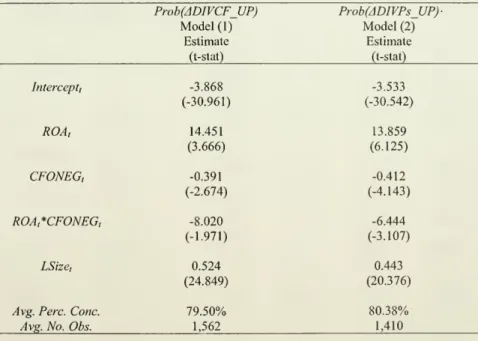

a lower incidence ofdividend increases. In Table III,

we

formally test the relationbetween

currentprofitability, the signofcurrentcashflows,

and

(changes in) dividendpayments

in thesample ofloss observations. Specifically,

we

estimate a logisticregression to evaluate the relation of profitabilityand

itscomponents

to the decision to increase current dividends. Focusingon

ourtwo

dividend variableswe

estimate the following four specifications:Prob

(ADIVCFJJP) =

og+

a,ROA,

+

asCFONEG,

+

asROA,*CFONEG,

+

a^LSize,

+

Si (1)Prob

(ADIVPSJJP) =

bg+

biROA,

+ b2CFONEG, +

bjROA,*CFONEG,

+

b4LSizet+

82 (2)where

ADIVCFUP,

ADIVPSUP,

ROA

are asdefinedbefore;CFONEG

isanindicatorvariable equal to

one

ifthe firm reports a negative cash flow,and

zero otherwise;variables ofinterest,

ROA,

CFONEG,

and

the interactionbetween

both variables,we

include a control variable for the sizeofthefirmineachspecificationsince

Hayn

(1995) and Joosand

Plesko (2003)relate the sizeofthe firmto thepersistenceofthe lossandtherefore the potential costofadividendincrease.

Our

sizevariableisLSize, thelogofthemarket value ofthefirm.

Table IIIreports the results ofestimating

models

(1)and

(2) usingthemethod

detailed

by

Fama

and

Macbeth

(1973). Inbothmodels

the coefficienton

ROA

ispositiveand

highly significant, consistent with a relationbetween

higher profitabilityand

dividendincreases.

However,

the negative coefficienton

CFONEG

indicatesthat, onaverage, loss firmswith negative cash flows are less likely to increasetheir dividend. Further, the negative and significant coefficient

on

ROA*CFONEG

shows

that the relationbetween

higherprofitabilityand

dividend increasesinthefullsample

issmallerfor firms with a negative cash flow.

The

size control variable has a positiveand

significant coefficient, suggesting that larger firms are

more

inclined to increasedividendsinthecurrentlossyearregardlessofthesignofthecashflow.^

Insum,theanalysesinTablesIthroughIIIsuggesta positive relation

between

a firm's profitabilityand

its propensity to increase dividends. Focusingon

lossobservationsinparticular,

we

findthepresence ofanegativecashflowcomponent

oftheloss reducesthe probabilityofadividend increase,consistentwith negative cash flows fromoperations increasing the costofadividendincrease.

III.

Do

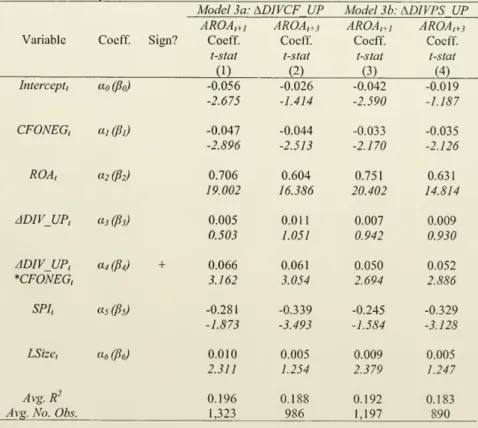

dividend increases forecast futureprofitability?To

examine

whethercostlydividendincreases constitutestrong signalsoffiatureprofitability

we

estimate an earnings forecastingmodel

in our sample of lossobservations. Since

we

arguethatincreasesindividend outflows aremore

costlywhen

cash flows are negative,we

predict the decision to increase dividends is a stronger predictoroffutureprofitability fornegative cash flowloss firms than forpositivecash flowloss firms.We

considertwo

forecasthorizons,one and

three years,and

focuson

futureaccountingprofitability

by

estimating thefollowingparsimonious models:'"AROA,+r

=

ao+

a,CFONEG,

+

ajROA, +

ajADIVCF_UP,+

a4

ADIVCF_UP*CFONEG,

+05

SPI,+

a^ LSize,+

83 (3a)AROA,^,

=

Po+

/^iCFONEG,

+

yff,ROA, +

y9jADIVPS_UP,+

P4

ADIVPS_UP*CFONEG,

+^5

SPI,+

PeLSize,+

£3 (3b)We

define futureprofitability as average ftitureROA

overthe forecast horizon:AROA,+^=(Z,+r ROA,+/t,

where

t=1 or 3)and

estimatemodels

(3a)and

(3b).The

firstspecification (3a) focuses

on

increases inDIVCF,

and

the second (3b)on

increasesinDIVPS.

ROA^

SPI,CFONEG,

LSizearedefinedas before.Our

main

variablesofinterestin

model

(3) are dividend increases(ADIVCFUP

orADIVPSUP),

and

dividendincreases interacted with the negative cash flow indicator variable

CFONEG.

If ourprediction that the decision to increase dividends is a stronger predictor of future

profitabilityfornegative cash flow loss firmsthanforpositive cashflow lossfirms, a^

and

^4willbothbepositiveand

significant.We

include controlsforcurrentprofitability (ROA), special items,and

size.We

include special items {SPI) for the reason

mentioned

earlier,namely

that previousresearchrelates

SPI

to both the qualityoflosses (i.e., degree ofpermanence)

and thedividend-paying behavior offinns (Skinner 2003).

We

include LSize to control forpotentially omitted variables such as risk or growth ofthe firm.

We

estimate bothspecificationsusingthe

Fama-MacBeth

methodology.Table

IV

presents theresultsofthe estimationof equations(3a)-(3b). All four estimationresults(columns(1)through(4)),focusingon

differentdividendmeasuresand

forecast horizons,

show

thesame

result for the dividend increase variables: the coefficients asand

/5jon

the dividendincrease variables are not significant, indicatingthat a dividend increase for loss firms with apositive cash flow

component

does notsignal future profitability controlling for other factors in the model.

By

contrast, the coefficients a^and

y9^on

the dividend increase variable interacted withCFONEG

are positiveand

significant in all specifications. Inuntabulated analysis,we

also find thesum

ofOi+a^ and ^3+^4

arepositiveand

statisticallysignificantinallspecifications.The

evidence isconsistent with dividend increases signaling futureprofitability, even after

controlling forotherfactors,

when

thecash flowcomponent

oflossesisnegative. Thisfindingsupports the hypothesisthat dividendincreases constitutean informative signal

when

the costofthe signalisrelativelyhigh.Table

IV

alsoshows

the coefficientson

CFONEG

{aj or ^/) are negativeand

significant in all four specifications, consistent with losses with negative cash flows

signaling persistent profitabihtyproblems(see alsoJoos

and

Plesko2003).By

contrast,the coefficients

on

ROA

(a2or ^2) are positiveand

highly significantinallspecifications, consistentwiththepreviousfindingson

theserialcorrelationandmean

reversionofROA

(e.g., Sloan 1996).

The

coefficientson

SPI

(as or (is) are negative in all fourspecifications,butthe levelofsignificance variesdepending

on

the forecast horizon: the coefficients aremarginallysignificantinthe one-year horizonmodels

(columns (1)and

(3)),but highlysignificantoverthethree-yearhorizon (columns(2)

and

(4)),suggestingspecial items affect firm profitability

more

over the longer horizon,and

are lessinformative overtheshorterhorizon. Finally, sizepredicts fiitureprofitabilityonlyone year ahead (columns(1)

and

(3)),but not threeyearsahead (columns(2)and

(4)).In

summary,

theresultsforbothdividendvariablesand

bothforecasthorizonsareconsistentwitha dividendincrease providing information

on

the futureperformance oflossfirms only

when

currentcash flows arenegative.We

interprettheresults toindicate theusefulnessofadividendincreasetosignalfuturefirmperformanceisdirectlyrelatedtotheexpectedcostofthedividendincrease.

IV.

Robustness

analysesWe

carryout three (unreported)analysesto testthe sensitivityand

robustnessof ourfindings. Inourfirstanalysis,we

focuson

asubsample

offirmswithmore

thanone

sequential loss, omitting observations for

which

the current loss is precededby

a profitable year.We

assume

that forthesefirms the costto increasedividendsshouldbegreaterthanforfirmsexperiencingafirstloss."

We

findchangesindividendsvaryasafianctionof whethera lossisthefirstloss(i.e.,the prior year'searnings

were

positive) orwhether the loss is

one

in a sequence (a repeat loss):10.38%

(9.08%) of first lossobservations increase dividend cash outflows (dividend cash outflows pershare) versus

1.44%

(1.27%) ofrepeat loss observations. This finding is consistent witha string oflosses revealingcontinuingprofitabilityproblems,

making

itmore

difficult forthe firmtoincrease dividend payments.

The

proportion ofrepeat losses with negative cash flows (74.90%) is also largerthan the corresponding proportion offirst losses with negativecash flows (58.60%). Repeat losses with negative cash flows also exhibit lower

profitabilitythanthosewitha positivecashflowcomponent.

The

descriptiveevidencesuggests the decisiontoincreasedividendswhen

afirm faces repeat losses constitutes apowerfulsignalregardlessofthe signofthecash flow.The

existence of such a strong signal forall multiple loss firms could diminish the signalingvalue ofa dividendincrease forloss firms with negativecash flows.We

re-estimate the predictiontestsin the sample ofrepeat lossobservations

and

observethat,consistent with our conjecture that increasing dividends

when

facing repeat losses iscostly evenforpositive

CFO

firms,the coefficients ajand

P}become

significant(atthe10%

level) in the one-yearmodels

but not in the three-yearmodels.More

important though, consistentwith our previousresults, the coefficients a4and

P4in(3a)and

(3b)remainpositive

and

significantinallspecifications. Allotherresultsremainqualitatively thesame.In a secondanalysis,

we

include additional control variables in (3a) and(3b)tocapture the levelofliquidity

and

recentgrowth ofthe firm.We

include cashand

short-termsecuritiesscaled

by

assets(annualCompustat

dataitem#1 scaledby

dataitem #6)as a

proxy

for liquidityand

the logofSales/Salesi.i (whereSales isannualCompustat

dataitem #12)as aproxyforgrowth.

When

we

includebothvariablesinthemodels,we

findthe coefficient

on

liquidityisinsignificantinallspecifications,whilethe coefficienton

thegrowth

proxyispositiveand

significant(atthe5%

level) inallspecifications.As

in theprevious robustnesstest, the coefficientsaj

and

fijbecome

significant atthe5%

level intheone-year horizon

models

(correspondingtocolumns

(1)and

(3) inTableIV), butremain insignificant inthe three-yearhorizonmodels. Throughout,the coefficients a4and

^4 remain positiveand

significant in all specifications, reinforcing the stronger predictive role for fiiture profitability of dividend increaseswhen

the cash flowcomponent

oflossesisnegative. Allotherresultsremainqualitativelythesame.In a final test,

we

re-estimate (3 a)and

(3b) in separate samples of lossobservations determined

by

the sign of cash flows. That is, ratherthan incorporatingCFONEG

and

the interaction term,we

estimate a simplifiedversionof(3a)and

(3b) inseparate samples, allowing the coefficients

on

ROA,

SPI,and

LSize to vary in both samples.The

procedure allows usto evaluatewhetherthe coefficientson

the dividendincrease variable

and

on

the interactionterminModels

(3a)and

(3b)capturedifferentialforecasting

power

oftheother variablesincludedintheequationwith'fixed'coefficients.Our

estimationsshow

thatthe coefficients a^and

^2on

ROA

varyasafunctionofthesignofthecash flow

component

oflosses;the coefficientson

SPI and

LSizehowever

arenotdifferent across the subsamples.

The

coefficienton

the dividend increase variable issignificantatthe

5%

levelin allspecifications,indicatingthatdividendincreases signal futureprofitabilityirrespectiveofthe signofthecash flowcomponent

ofthelosswhen

we

estimate themodels

inseparatesubsamples.Most

importantlythough,in supportof ourpredictionand

previous results, the magnitude ofthe coefficienton

the dividendincrease variable remains significantly larger in the subsample of negative

CFO

lossfirms thaninthesubsample ofpositive

CFO

losses.Summarizing,theresultsoftheadditionalanalysesinsubsamplesoflossfirms or

for different specifications of

Models

(3a)and

(3b) are all consistent with dividendincreases

by

loss firmsbeingmore

informativeabout futureprofitabilitywhen

thecashflow

component

ofthe lossisnegative thanwhen

itispositive.We

interpretourresultstoindicatethatthe

more

costlyadividendsignalis,themore

informativethedividendis aboutthe firm'sftitureperformance.V.

Conclusion

This paper provides

new

evidenceon

the role of dividends in signaling firms' future performance.We

examine

whether firms that report a current lossand

have a negativecashflowsignalftitureperformance ofthefirmthroughcostlyincreasesincashdividends.

We

distinguishbetween

losses determinedby

negative cash flows versusnegative accruals to capture the cost ofa current dividend increase.

We

argue thatincreasingdividend

payments

when

thefirmisalready losingmoney

constitutesa strong signaloffiatureperformancefortwo

reasons. First,theincreaseincurrentcash dividendsaffectsthecurrentliquidityofthefirm. Second,theincreaseincashdividendsimplies a strong

commitment

to an increased level of dividend cash outflows in the fiature sincepreviousresearch

documents

ahighreluctanceofmanagers

tocutdividends.The

evidencein thepaperstrongly supports thehypothesis thatcostly dividendincreases

by

loss firmswith negative cash flowsconsistently predict future measures of performance betterthan dividendincreasesby

other loss firms.While

recent empiricalresultshave discounted the role of dividendsas a signaling

mechanism

in large cross-sectional samples(Benartzi etal. 1997, Grullon etal. 2003, Skinner 2003), ourresultssuggest costly dividend increases are informative for a

narrow

group of firms. Fornegativecashflowlossfirms,theuseof cashto

pay

a dividend,ratherthantoreinvestintheongoingoperationsofthefirm,suggests

management

judgesthe prospectsofthefirmtobe good, even thoughcurrentearningsarenot.

Our

focuson

lossfirmshasbroaderimplications as researchshows

thatlossfirmscomprisea large

and

increasingshareofpublicly-tradedfirms(e.g.,Hayn

1995,Joosand

Plesko 2003, Skinner 2003). Therefore, an increasingly larger set of

managers

isconfi-onted with reporting negative earnings that are generally

much

less informative aboutfutureperformance ofthe firm.As

aresult,theyface theneed

torelyon

additionalmechanisms beyond

reportedprofitabilitymeasurestoprovideinvestorswith informationaboutthefirm'sprospects.

References

Aharony, Joseph,

and

Itzhak Swary, 1980. Quarterly dividendand

earningsannouncements and

stockholders' returns:An

empirical analysis.Journalof

Finance,35, 1,1-12.

Asquith, Paul,

and David

W.

MuUins,

Jr, 1983.The

impact of initiating dividendpayments on

shareholders' wealth.Journalof

Business, 56, 1,77-96.Bemartzi,

Shlomo,

Roni

Michaely,and

RichardThaler, 1997.Do

changes individendssignalthe future or the past?Journal

of

Finance,52,3,1007-1043.Brav, Alon, John R.

Graham, Campbell

R. Harvey,and

Roni

Michaely, 2003, Payoutpolicyinthe21stcentury.

Working

paper.Duke

University.DeAngelo,

Harry, Linda E.DeAngelo, and Douglas

J. Skinner, 1992. Dividendsand

losses.Journal

of

Finance,47, 1837-1863.DeAngelo,

Harry, Linda E.DeAngelo, and Douglas

J. Skinner, 2003.Are

dividendsdisappearing?dividendconcentration

and

theconsolidationofearnings.Forthcoming

Journal

of

FinancialEconomics.Fama, Eugene

F.,and

Kenneth

R.French, 2001. Disappearingdividends:changingfirmcharacteristicsorlower propensitytopay? Journal

of

FinancialEconomics,60, 3-43.Fama,

Eugene

F.,and James

D.MacBeth,

1973. Risk, returnand

equilibrium:Empiricaltests.Journal

of

PoliticalEconomy,

81,607-636.Grullon, Gustavo,

Roni

Michaely,Shlomo

Benartziand

Richard H. Thaler, 2003. Dividend changesdo

not signalchanges infutureprofitability.Working

paper.RiceUniversity,CornellUniversity,Universityof Chicago.

Hayn,

C,

1995.The

information content of losses. Journalof

Accountingand

Economics,20, 125-153.

Healy, Paul. M.,

and

Krishna G. Palepu, 1988. Earnings informationconveyed by

dividendinitiations

and

omissions.Journalof

FinancialEconomics, 21,2, 149-175.Joos,Peter,

and

George

A. Plesko,2003. Lossreversals,and

earnings-basedvaluation.Working

paper,MIT.

Lintner, J., 1956. Distribution of

incomes

ofcorporationsamong

dividends, retained earnings,and

taxes.American

Economic

Review,46, 97- 113.Miller,Merton,

and

Franco Modigliani, 1961.Dividendpolicy, growth andthevaluationMiller, Merton,

Kevin

Rock, 1985, Dividend policy under asymmetric information Journalof

Finance,40, 1031-

1051.Nissim, Doron,

and

Ziv,Amir, 2001. Dividend changesand

futureprofitability.Journalof

Finance, 56,2111-2133.Sloan,Richard, 1996.

Do

stock pricesfully reflectinformationinaccrualsand

cash flowsfor futureearnings?

The Accounting

Review, 71,3, 289-315.Skinner,

Douglas

J., 2003.What

do

dividendstellus aboutearnings quality?Working

paper, University of

Chicago

Graduate School of Businessand

University ofMichigan

BusinessSchool.Spence, Michael, 1973.Jobmarketsignaling.

The

QuarterlyJournalofEconomics,

87,3,355-374.

Watts,Ross, 1973.

The

informationcontentofdividends.Journalof

Business, 46,2,191-211.

Earlier

work by

Benartzietal. (1997)discusseshow

previous empiricalwork

provides evidencethemarkettreatschangesindividendsasnewsworthy

(seeAharony and Swary

1980, Asquith

and

MuUins

1983).They

also point out it is not clear that dividend changessignal futureearnings changes,as thehypothesispredicts.The

authorsconclude changes in dividendssummarize

information about the past,namely

past earnings increases,ratherthanthefuture,i.e.,upcoming

earnings increases.Other

examples of

studies thatfailtofindevidenceor findevidencethatismixed on

the question whether dividend changesmap

intofuture earningschanges areWatts (1973),Healy and

Palepu(1988),DeAngelo

etal.(1992)." Previousresearch

proposescostsassociatedwithdividend payments,for

example

Millerand

Rock

(1985) arguethesignaling costof

dividendsisforgone investment.However,

we

know

ofno

researchthatstudies thepower

ofthedividendsignal asaftinctionoftherelativelevelofthecost.

Skinnerdefines largedividend-payingfirms as firms

whose

dividendisinthe top quartileof dividends paidineach decade.^

Note

the results inJoosand

Plesko (2003)

and

Skinner (2003) are at odds withthe findinginBenartzi etal. (1997)"thatdividendcuts reliably signal anincreasein fiitureearnings."(p. 1031-1032, emphasisintheoriginal).

DDS

reportthatdividendreductionsoccurlessoftenwhen

the lossesincludeanaccrual for special items, butdo

not differentiate whether the underlying loss is drivenby

accruals or cash flows. Further, the results ofBenartzi et al. (1997) suggest that if

dividendshave

any

signalingpower,itisthrougha reduction,ratherthananincrease.^

The

findingsofFama

and

French (2001)

who

report adecreaseintheproportion ofdividend-payingfirmsinthe

US

over timeand

DDS

(2003)who

show

a large increaseintheconcentrationof dividend

payments

over timealsounderline thechangesindividend-paying behavior of

US

firms.^

We

winsorizeallvariablesofinterest atthe1st

and

99' percentile.' In unreported analyses,

we

estimate additional specifications ofmodels

(1) and (2).

Specifically,

we

also include SpecialItems inone ofthe specificationsand

findthatthey obtain a significant negative coefficient, whereas the other resuhs remain qualitativelyunchanged. Similarly,

we

includeanindicatorvariable todistinguishbetween

firstandrepeat losses

and

find a positive coefficient on this variable, with all other resultsremainingqualitativelyunchanged. Finally,

we

alsoestimate a versionofmodels

(1)and

(2) that includes a control variable forthedividendpolicyofthe firm sinceunreportedanalysis

shows

theincidenceof dividendincreasesrelates towhetherthefirmpreviously paidadividendornot:we

includeanindicatorvariablethattakeson

thevalueof one ifthe firmpays adividend(i.e., annual

Compustat

data item #21 islargerthanzero),andzerootherwise

and

findtheresultsdo

notchangequalitatively.We

alsoestimatetwo-year horizonmodels

with results similarto the oneand

three-yearhorizon models. Also, consistentwith previousresearch

we

focusonthe predictionof an accounting variable only (e.g.,

Nissim and

Ziv 2001). Benartzi et al. (1997) furthermorepoint outthatthe relationbetween

dividendincreasesand

futureaccountingvariables or future returnsisdistinct:whereasthey find

no

evidenceofa relationbetween

dividend changes

and

future earningschanges, they observepositiveexcess returnsforthe three yearsfollowingadividendincrease.

'

'Joos

and

Plesko (2003)document

thattheprobabihtyofalossfirm returningtoprofitabilityishigherfor firms incurring afirstlossthanforfirmswithrepeatlosses.

'^

We

alsocompare

the descriptivestatisticsinTableIItodescriptivestatisticsforrepeat losses

and

find the repeat loss observations generally exhibit significantly lowerprofitabilitythan thetotalgroup oflossfirms.

TABLE

ISample

Information

Ourinitialsampleconsistsoffirm-year observations fromCompustaVsIndustrialand ResearchAnnual Data Basesforthe years 1971-2000.

We

defineour earnings variableasincome(loss)before extraordinary items anddiscontinued operations orIB(annualCompiistat data item #18).We

defineADIVCF

as thechangeintotal dollaramount ofdividends paidbythefirm (annualCompustatdataitem #21).

We

defineADIVPS

asthechangeintotaldollaramount ofdividends paidbythe firm per share (annualCompustatdata item #21/ annualCompustatdataitem #25).

Panel

A:

FullSample:

Profitvs.Loss

ObservationsIB,>0

N

%

IB,<0

N

%

TOTAL

FullSample

146,39470.92%

60,02629.08%

206,420Profitvs.Loss

and

Past DividendsDiv,.,

=

65,35655.57%

52,26244.43%

117,618Div,.,>0

81,03891.26%

7,7648.74%

88,802Profit

and

Lossand

Current DividendsDiv,

=

63,77154.10%

54,10545.90%

117,876TABLE

IILoss

Firm

Sample:

DescriptiveStatisticsOurinitialsampleconsists offirm-yearobservationsfromCompustafs Industrialand ResearchAnnual DataBasesforthe years 1971-2000. Thetableshowsdescriptivestatisticsfor lossfirm-year observations

(N=60,026). Sizeis marketvalue (priceorannual Compustatdata item#199* numberofoutstanding shares or data item #25).ROA, =IB/TA,.],wherewedefineour earnings variableasincome(loss)before extraordinary itemsanddiscontinued operations orIB(annualCompustatdataitem #18).

We

define the cash flowcomponent ofearnings orCFO

ascashflowfi-omoperationsscaledbylaggedassetswherewemeasurecashflowfromoperationsasnetincome(annualCompustatdataitem #172)-accruals. Accruals

is(ACurrentAssets (data item #4)-ACash(dataitem #1)-ACurrentLiabilities(dataitem #5)+ADeblin

CurrentLiabilities(dataitem#34) +DepreciationandAmortizations(dataitem #14).SPIisspecialitems (annualCompustatdata item#17)scaledbylaggedassets {TA,.i). Thetablereportstestsofdifferences

betweenthemeans and medians ofthetwo subsamplesdeterminedbythesignofthe

CFO

variable (two-sidedt-testsandtwo-sidedWilcoxontestsforthemeanandmedian).ADIVCFUP

(ADIVPSUP)

isan indicatorvariablethattakes thevalueof1 ifthechangeindividend cashoutflow (dividendpayoutpershare), and zero otherwise, where dividends are annual Compustat data item #21 and number of

outstanding sharesisannualCompustatdataitem #25.

TABLE

IIILogisticRegression

Model

ofProbability ofDividend

IncreaseThetablecontains theresultsofa logisticregressionwithasindependent variable an indicator variablethat

takes the valueof1ifthecompanyincreasesitsdividends(measuredasatotalcashflow(DIVCF)orcash flow per share(DIVPS)) andzero otherwise.

Prob(ADIVCFJJP)

=ao

+ a,ROA, +OiCFONEG, +a,ROA,*CFONEG,

+a^LSize,+e, (1)Proh

(ADIVPSUP)

=bg+ b,ROA, +bsCFONEG,+b,ROA,*CFONEG,

+b^LSize,+£2 (2)ADIVCFJUP (ADIVPSUP)

isan indicator variablethattakesthevalueof1 ifthechangeindividend cashoutflow (dividendpayoutpershare),andzero otherwise,wheredividendsareannualCompustaldata item #21 andnumberofoutstanding sharesisannualCompustatdataitem #25. ROA, =IB/TA,.i,where IBis

income(loss)before extraordinary itemsanddiscontinued operations (annualCompustatdataitem #18)

and TAistotalassets (annualCompustatdataitem#6);

CFONEG

isanindicator variablethattakesonthe valueofoneifthe firmreportsa negative cash flow(CFO), andzero otherwise;ROA

*CFONEG

istheinteractionvariablebetween

ROA

andCFONEG;

LSizeislog(market valueof the firm)wherewe

definemarket value as closing price (annual Compustat data item #199) times shares outstanding (annual

Compustatdata item#25)atfiscal-yearend. Ourinitialsampleconsistsoffirm-yearobservationsfrom CompustafsIndustrialand ResearchAnnual DataBasesfortheyears 1971-2000, and

we

carry outour analysis in asubsample of 60,026 loss firm-year observations.We

report the resultsofthe logisticTable

IV

Prediction TestsThetablereportstheresultsofthe

OLS

regressions,estimatedusingtheFama-Macbethmethodology: AROA,^,=

ao+a,CFONEG,

+a^ROA, +a,ADIVCFJJP,+

a^ADIVCF_UP*CFONEG,

+asSPI,+«« LSize,+Eia (3a)

AROA,^,=fio+

P,

CFONEG,

+y3,ROA, +P3AD1VPS_UP,+fi^ADIVPS_UP*CFONEG,

+P,SPI,+P6 LSize,+Eib (3b)

whereaveragefuture

ROA

overtheforecasthorizonisAROA,+,=(£,+r ROAi+/t) whereROA, =IB/TA,.i,IBis annual Compustatdataitem #18, TA istotal assetsorannual Compustatdataitem#6 (t=1 or 3);

CFONEG

isan indicator variablethattakes thevalueof1 ifCFO

isnegative,andzero otherwise;we

measureCFO,orcashflowfromoperationsasnetincome(annualCompustatdataitem#172)-accruals.

We

measureaccruals orACC

as {ACurrentAssets (data item #4) - ACash (dataitem #1) - ACurrentLiabilities(dataitem #5)+ ADebtinCurrentLiabilities(dataitem#34)+DepreciationandAmortizations (dataitem #14);SPIisspecial items(annualCompustatdataitem#17) scaledby laggedassets {TA,.i);

ADIVCFUP

{ADIVPSJUP)isanindicatorvariablethattakesthevalueof1 ifthechangeindividend cash outflow (dividendpayoutpershare),andzero otherwise,wheredividendsareannualCompustatdataitem #21andnumberofoutstanding sharesisannualCompustatdataitem #25; LSizeislog(market valueofthe firm)wherewe

define marketvalueas closing price (annualCompustatdata item#199)times shares outstanding(annualCompustatdataitem#25)atfiscal-yearend. Ourinitialsampleconsistsoffirm-year observationsfrom Compustat'sIndustrialand Research Annual Data Basesfor theyears 1971-2000,andwe

carry out the analysis reportedinthetable inasampleconsistingof 60,026lossfirm-year observationsMITLIBRARIES