Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

0ew9\(f

working

paper

department

of

economics

CORPORATE

CONTROL

AND BALANCE OF

POWERS

Daron

Acemoglu

94-22June

1994

massachusetts

institute

of

technology

50

memorial

drive

Cambridge, mass.

02139

CORPORATE

CONTROL

AND BALANCE

OF

POWERS

Daron

Acemoglu

.iAStiACHUSEfTSiNSTlTUlE

OF TECHNOLOGY

OCT

2

11994

CORPORATE

CONTROL AND

BALANCE

OF

POWERS

DARON ACEMOGLU

Department

ofEconomics, E52-71 Massachusetts Institute ofTechnology50

Memorial

Drive,Cambridge,

MA

02139FirstVersion: July 1992 Current Version:

June

1994JEL

Classification:D23,

G32

Keywords: Incomplete Contracts, Separation of

Ownership

and

Control,Property Rights, Managerial Discretion, Dispersion of Ownership,

Decentralized versus Centralized

Ownership

I

am

grateful to Olivier Blanchard, Patrick Bolton, DenisGromb,

Leonardo

Felli, Oliver Hart,Owen

Lamont,

ErnstMaug, John Moore,

Thomas

Piketty, Steve Pischke,Andrew

Scott,David

Scharfstein,

Jeremy

Steinand

JecinTirolefor helpfulconversationand

discussion. Early versions ofthis paperwas

presented at theLSE,

University of Bristol,Southampton and

York. I thankCORPORATE

CONTROL AND

BALANCE OF

POWERS

Abstract

Most

managers

enjoy considerable discretionand

protectionfrom

possible interventionswhich

enablesthem

tolook aftertheirown

interests. This is often attributed tothe dispersion ofshareholders

and

regulations that deter effective outside interventions. This paper presents amodel

thathas empire-buildingmanagers

who

have importanteffortchoices.Because

themanager

is not the residual claimants of the relevant returns, in order to provide

him

with the right incentives,he

needstobegivensufficient discretionand

theopportunitytosharesome

oftherentshe

creates.To

achievethis,equilibrium organizationalform

separates controlfrom

ownershipand

tries to contain the manager's empire-building incentives using performance contracts

and

the capital structure rather thanmore

directmethods

ofcontrol. Nevertheless, owners willoften be unable tocommit

to managerial discretion because ownership of the assets givesthem

the right to decide towhat

use that assetwill be putand

thus the right to fire the manager. In this case,it will

be

necessary to choose a disperse ownership structure in order to create free-rider effectsamong

shareholdersand

thus tocommit

them

to bepassive. Thus, the dispersion of ownership,rather than being the cause of the problem,

may

be a solution to amore

serious one. Nevertheless, there will often be benefits to having large shareholders. In this case, the papershows

that an intermediate level of dispersion is theoptimum.

First Version: July 1992 Current Version:

June

1994JEL

Classification: D23,G32

Keywords: Incomplete Contracts, Separation of

Ownership and

Control,Property PUghts, Managerial Discretion, Dispersion of Ownership,

1) Introduction

Most

corporationsare run bymanagers

who

are not the residual claimants of the returns theygenerateand

who

canthereforebe

expectedtodeviatefrom

value maximization. Shleiferand

Vishny (1988, p.S) write;

"A

wealth of evidence suggests thatmanagers

often take actions that dramaticallyreducethe value ofthe firm. Witness, forexample, the ability ofmanagers

todefeat hostiletender offers, evenwhen

shareholders stand togainhundreds

ofmillions ofdollarsfrom

thebid, or the ability toundertakebillion dollaroilexploration projects thatthe

market

treats ashavingnegative present value

(McConnell

and

Musceralla(1986))."Blanchardetal's(1993) recentstudyclearly

documents

how

managers

tend tospendthe free-cash flow innon-valuemaximizingways. In a sample of firms without profitable investment opportunities, windfall cash gains are

never paid to shareholders

and

are often used inways

that appear farfrom

value maximizing.These

observationsand

many

similarones (seeJensen(1988)) suggestthatmanagerial discretionisharmfultocorporateperformance.Popularpress

and

"gurus" alsoseem

toagreethatmanagerialdiscretion is costly

and

that it should be limited. Michael Porter (1992, p.14) writes "Outsideowners should

be

encouraged toholdlarger stakesand

totake amore

active role incompanies". MichaelJacobs' (1991)book

isone

ofthemany

examples inthepopularpress thatarguein favor of effective ownershipand

intervention in the"Warren

Buffet style".The

diagnosis associated with the above line of reasoning is often that the passivity of disperseshareholders leadstoexcessivemanagerialdiscretionand

theimplicitlysuggestedremedy

is to reducethe discretion of the

manager

-forinstance byhighdebt claims (e.g. Jensen (1986)), the discipline of aboard

of directors (e.g.Fama

£ind Jensen (1983)), or takeovers (e.g.Manne

(1965)). Incontrast, the

main argument

ofourpaperisthat thediscretion thatthemanager

enjoysmay

actually have an importanteconomic

roleand

dispersion of ownershipmay

be theway

to secure such managerial discretion in equilibrium.Managers

often have important decisions but arenot theresidualclaimant of the returns they generate. Thiswould

leadtothewrong

incentiveswhen

contracts are incomplete.One

way

ofpreventingthis isto redistribute property rightsso as tomake

themanager

residual claimant using theinsightthatownershiptransfers controlrightsand

thus rents

(Grossman and

Hart (1986), Hartand

Moore

(1990a)). Yet, because in ourset-up themanager

does not havethe resources tobuy

the relevantassets, thissolution is notpossible.Our

suggestionstartswith thewell-knownobservationthatthemarriageof ownershipand

controlneed

not be absolute.

The

manager

can enjoy part ofthe rents generated by his effort choices evenwhen

he is not theowner

of the assets as long ashe is in control. Therefore, in order to ensurethe right incentives, the

manager must be

givensome

discretion to enjoy rents within the organization. Obviously, thereis alimitto theamount

ofrents thatthemanager

shouldbe givenand

the optimal organizationalform

should strive to achieve a balance ofpowers.also

makes

it difficult for the owners to relinquish part of the control associated with theownership of the assets.

Then

anticipating the separation of ownershipand

control not to becredible, the

manager

willhaveno

incentive tosupply high effortand

inefficiencies areincreased. Inmany

situations, the onlyway

to achieve a credible divorce of ownershipand

controlwill betofurther

muddy

theconceptof ownership;in otherwords,tocreate a disperseownershipstructure so that those shareholderswho

take control confer apositive externalityon

other shareholders. This will introduce afree-riderproblem

among

shareholdersand

passifize them, givingenough

breathingspacetothemanager. Thus, oursuggestion istoreverse the conventional

wisdom

which

takes the disperse ownershipstructure asgiven

and

argues thatthisleads topassiveshareholdersand

to toomuch

managerial discretion; in contrast, our claim is that a decentralized ownershipstructure

may

be

chosen in order tomake

shareholders passiveand

provide themanager

with sufficient discretion.Our

model

is simple.There

is free cash flow in the firm that themanager

can misuse.Shareholders can prevent this non-value maximizing behavior in a

number

of ways.The

firstsolution is tight control by the owners or by an independent board of directors. In this case,

although the

owners

have delegated certain tasks to the manager, there willbe

little separation ofownershipand

control. Second,we

can have"hands-off' (decentralized) ownership relyingon

performance

contractsand

capital structure to control the manager's discretion.Our

firstmain

result, Proposition 1, is that even to the extent that the first solution, effectiveowner

control, ispossible, it is often unattractive

and

a high degree of separation of ownershipand

control ispreferred. This is because

whenever

the conflict is intenseand

they have the power, the ownerswill ignore the manager's interests. In particular, the ownership ofthe assets of the corporation gives

them

the right to replace the manager. If it is expensive to prevent themanager from

consuming

the free cash flow, the ownerswill prefer tofire him.But

anticipating thathe

will bereplaced, the

manager

willhavelessincentive toprovide therightlevelofex ante effortand

more

inefficiencies will be introduced.

Our

secondmajor

result is contained in Proposition 2which

demonstrates thatwhen

owners

cannotcommit

not to intervene, efficient organizationalform

requires a disperseownership structure. Decentralized ownership introduces free-rider effects

among

owners

and

makes

owner

intervention unlikely. Thus, it is a credibleway

of committing to managerialdiscretion.

Yet

it is alsowell-knownthat large shareholdersand

centralized ownershipwill oftenhavebenefits, forinstancebettermonitoring.Inourbasicmodel, interventionbyshareholders has

no

roleonce

optimal performance contracts are written for the manager.We

then modify our assumptionsand

allow thepossibilitythat themanager

canpay-outsome

of the free-cash flowoutif

he

wants to (say in theform

of stock repurchases) andunder

this assumption,we

derive ourour particularmodel, with this optimal intermediate ownership structure, first-best is achieved.

We

also use thisframework

to analyze the impact of takeover threaton

organizationalefficiency.

The

findingshereare not surprisinggiven our threemain

results above; takeovers areharmful if they disturb the balance of power, thus in equilibrium, there

would

alwaysbe

some

positiveleveloftakeoverdefence

mechanism.

However,

when

there arebenefitsfrom

monitoringthat cannot

be

exploited byshareholders, there exists an interiorsolution forthe optimal degreeoftakeover threat. This findingthat

owner

interventionand

takeoverthreat are substitutes is inlinewith theevidenceinShivdasani (1992)that

when

theboardofdirectorsholdssignificantstock inthecompany,

takeovers arerare,and

also in accordwith theview thatin-Japanand

Germany,

takeovers are not necessarybecause other forms of control are very effective (e.g.

Roe

(1993)).However

ourmain

theoretical results also suggest caution inpromoting

takeoversand

German-Japcinese style

owner

intervention becausethemain problem

is not only to control themanager

but to achieve a balance ofpowers.

The

plan of the paperis as follows.Next

sectiondescribes thebasicenvironment. Section 3 analyzes the equilibrium organizationalform

and shows

that a high degree of separation ofownership

and

control,withincentivecontracts forthemanager and

amoderate

levelofdebt,willoften

be

the equilibrium choice. Section 4 introduces the possibility of useful intervention by ownersand

derives the optimal degree ofownership dispersion,which

is alsoshown

to achieve the first-best in this model. Section 5 quickly applies thisframework

to the interactionbetween

takeovers

and

organizational efficiency. Section 6 relates this paper to earlier literatureand

concludes.

2) Description ofthe

Environment

We

willnow

describe amodel

designed to capture the presence of conflicting interestsbetween

themanagement

and

shareholders that cannot be completely resolved by an incentive contract.A

manager

is running a firmon

behalf of a single owner. (Sincewe

will later askhow

the dispersion of ownershipmay

be influencedby strategic considerations,we

first consider thecase of a single owner).

The

world consists ofthree periods t=0, 1and

2 asshown

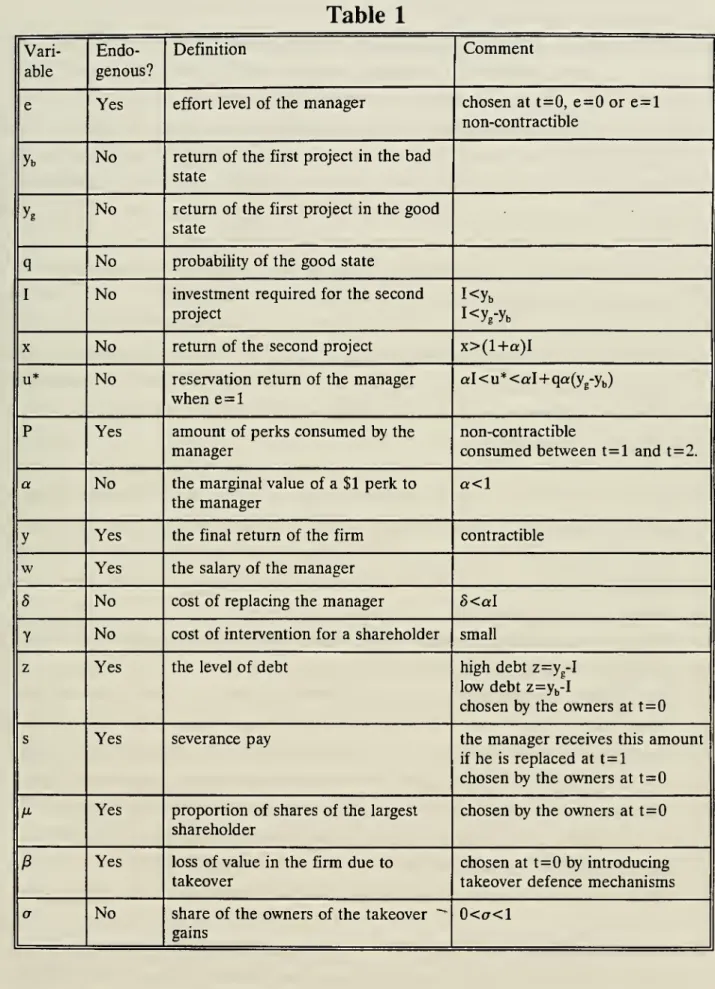

in Figure 1.Table 1

summarizes

all thevariablesused in this paper that are alsolater introduced in the text.We

assume

that theowner

makes

atake-it-or-leave-it offer to themanager

at t=0.The

offerisapackageconsistingofanorganizational

form

(and ownershipstructure), capitalstructureand

incentive contract.The

incentive contract relates the manager's reward towhether

debt obligationshavebeen

met and

tothefinal (t=2) returns ofthe firmthat areverifiable. Next, themanager

chooses an effort level(e=0

or 1)which

influences the likelihoodof thegood

stateand

undertakesthefirstproject

which

for simplicityisassumed

to cost zero.The

human

capitalofthiso

-3

fi) CD § *§•§

I

g 1. MIII

rt D 5?

3%

(a s-o M S ar rti []Tl

cq'

C

(D

§i

D."

D

^

a

s. (D a. 0)3

g

ffl to55-3

5; <DTable

1

Vari-able Endo-genous? DefinitionComment

e

Yes

effort level of themanager

chosen at t=0,e=0

or e=

lnon-contractible

Yb

No

return of the firstproject in the bad stateyg

No

return of the first project in thegood

stateq

No

probabihty of thegood

stateI

No

investment required for the secondproject

KYb

Kyg-Yb

X

No

return of the second projectx>(H-a)I

u*

No

reservation return ofthemanager

when e=l

al<u*<al+qa(y^-y^,)

p

Yes

amount

of perksconsumed

by themanager

non-contractible

consumed

betweent=l

and t=2.a

No

the marginal value of a $1 perk to themanager

a<l

y

Yes

the final return of the firm contractiblew

Yes

the salaryof themanager

8

No

cost ofreplacing themanager

8<al

y

No

cost of intervention for a shareholder smallz

Yes

the levelofdebt high debt z=yg-Ilow debt z=yb-I

chosen by the owners at

t=0

sYes

severance pay themanager

receives thisamount

ifhe is replaced at t=l chosen by the owners at

t=0

M

Yes

proportion of shares ofthe largest shareholderchosen by the owners at

t=0

fi

Yes

lossofvalue in the firm due totakeover

chosen at

t=0

by introducing takeover defencemechanisms

a

No

share ofthe owners of the takeover^

gains

before t=l.

The

fact that organizationalform and

capital structure are chosen at the beginningis our

way

of formalizing that these are endogenous.At

date t=l, firstthe stateofnatureis revealed as eithergood

orbad and

then the return of the first project is realized'.At

this point the return of the project is notyet verifiable nor isthe state of nature,

hence

nothing is contractible (in contrast tot=2 where

final returns are contractible).However,

debt contracts with maturityt=l

Ccin bewritten to induce themanager

topay-out

some

portion of thefirm'scash-flow.At

t=

1 anew

(indivisible)investmentproject,that costs Iand

has certain return equal tox, can alsobe

undertaken. Crucially for all ofourresults,after

t=l

themanager

can usesome

portion of the returns already realized for hisown

benefit,i.e.

consume them

asperks,buthe

cannotconsume

the return of thesecondprojectthat accruesat t=2.

The

consumption

of perks can be either abusing an expense account,embezzlement

or simplyinvestinginlowreturnbutprestigious(empire-building) investments.Assuming

thatreturnsand

actions att=l

arenon-contractible iscertainly stylisticand

simplifying.However,

our resultswould

holdinotherenvironmentswhere

incompletenessof contracts preventsa perfect alignmentof interests (for instance suppose

payments

att=l

are contractible, our resultswould

remainunchanged

if shareholders can fire themanager

after the state of nature is revealed but before the returns are realized).It is also

assumed

that aftert=l, the manager'shuman

capital isno

longeressential andthe

owners

(orsome

other claim-holders)may

decide toreplacehim

with another manager. Thisset-upwill enableusto

model

the degreetowhich

themanager

has control over the organization. Inpractice,managers

arerarely fired bythe ownersbutwe

would

liketo allowfor thispossibilityand

investigatewhat

the equilibrium degree ofjobsecuritywill be formanagers. Inthis context,we

allow fortwo

possibilities:Scenario

A

:whether

the owners have theright to replace themanager

may

bedetermined bythegovernance structure chosen at t=0.

Scenario

B

: irrespective ofthe governance structure, the owners have the right to interveneand

fire the

manager

att=l, sayby callinganEmergency

GeneralMeeting

(EGM).

We

willassume

thatinterventionhas asmallprivate cost y for the shareholder

who

callstheEGM.

y can alsobeinterpreted as the cost that a shareholderneeds to incur tomonitor the success ofthe

company

(e.g. read the annual report). Scenario

B

has a natural plausibilitycompared

toA

because ownership normally gives the right to decidewho

will use the assetsand

these rights cannot be surrendered easily. Inwhat

followswe

will start with ScenarioA

because this will define the optimal degree ofseparation ofownership and control, but the casewe

aremost

interested in isWe

model the state of nature to be revealed before the actual returns to allow for "dividendpoliq'" insection 4; therethemanagerwillbeallowedtoannounce andcommitto alevel ofdividendafter

Scenario B.

Finally, at

t=2

the return of the second investment project is realized, themanager

pays out the return of the secondproject togetherwithwhat

isleft-overfrom

the return of thefirstone

and

isrewarded

according to these returns as specified by his incentive contract.We

alsomake

the following assumptions. First,there isno

discounting in thismodel and

all agents are risk-neutral.

The

manager

hasno

resources tobuy

thecompany

or to pay an entry fee at the beginning of the relationship.At

t=0, themanager

can choose effort e equal to or1 (low or high effort).

The

reservation return ofthemanager

(or cost of managerial effort) isequal to if

e=0,

equal to u* if e=l. Ife=0, the first project has zero return. Ife=l,

there isaprobability q that the state ofnaturewill

be

good and

the projectwillyield theamount

y^and

with probability 1-q, the state ofnaturewill be

bad and

the return of the project is equal to the smalleramount

y^.The

second project isassumed

to be always availableand

to yield thesame

return, x, irrespective of the effort level of the

manager and

the state of nature.As

described above, themanager

can use the"freecashflow"inways

thatdo

notenhance

the value of thefirm.We

assume

that every $1 of thefirm's cash generates$a

of return for themanager where a<l.

Thus

the transformation of cash into perks is inefficient, for instance because direct theft is notpossible

and

themanager

has to use indirectmethods

toconsume

this cash flow. Perkscan onlybe

consumed

during the life of the project (i.e.between t=l

and

t=2). Finally, replacing themanager

costs8and

thenew

manager

canbe chosen suchthathe

cannotconsume

anyperks.Thisassumption is quite crucial for our analysis since it

makes

the replacement ofthe firstmanager

sufficiently attractive for the owner. Intuitively,we

can argue that there aremore

thanone

type of managers.One

kind is easy to control but also not very productive, while another type isessential for growth projects like the

one

undertaken at t=0, but is difficult to control.More

simply,shareholdersmay

be unabletotellapartgood managers (who do

notconsume

perks)from

bad

ones before they are put in place.With

this interpretation, ourmodel would

only apply to firmsthathired a "bad"manager

tostartwith,sincetheowners of these firmswillwishto trytheir luckonce

more

in the managerial labormarket

at t=l. Alternatively it can alsobe

argued thatit takes time for

managers

to familiarize themselves with the organization of the firmand

for a while they areunableto usecompany

resourcesfor theirown

interest; thus in the short-run, theowner

will benefitfrom

anew

manager. Finally, it is also possible to interpret firing as anintervention by owners or other claim holders that reduces the (private) return of the

manager

by an

amount

8(similar toDewatripontand

Tirole (1992)) aswell aspreventing theconsumption

ofperks.

With

thismodification, all our resultswould

remainunchanged

ifthe reservation returnof the

manager

is taken to be equal to u*-l-5.As

far as the governance structures go,we

will considertwo

cases.The

first correspondsowner

hasno

direct control.We

refer to this as managerial discretion. In contrast, the secondgives the

owner

the discretion to fire themanager

at t=l.We

refer to this asowner

controlled organization. In ourmodel

all other organizational forms areno

differentthan thesetwo

simple cases.We

will startby assuming thatthe allocation ofdiscretion is contractible (scenarioA)

and

later return to scenario

B

where

theowner

will notbe

able to choose directlybetween

thetwo

governance structures.

The

capital structureswe

discuss are alsovery simple.As

it will beclear later, long-termdebt contracts have

no

role in thismodel

since att=2

incentive contracts conditionalupon

finalreturns of the firm can bewritten.Therefore, only debt contractsthat

mature

att=l need

to be considered (see footnote 6 for a caveat).We

assume

that at t=0, theowner

sells debt contractsin a competitive market.

A

debt contractamounts

to apromiseto pay zat t=l. Thispayment

isnotconditional

upon

thestateofnaturesincethisisnotverifiable. Rationalinvestorswillcorrectly realizewhat

themanager

will payinthe twostatesand

valuethis debt contractaccordingly.Thus

shareholderswill alwaysreceivethe value of the

company

but thisvaluemay

be influenced by thesize of the debt obligations. Since the

owner

is not credit constrained, an alternative is to think that she holds the debt contracts herselfand

this interpretation will simplify the exposition.Our

results

would

remainunchanged

aslong asthe debtmarket remained

competitive, even ifanew

class of claim-holders

were

introduced^.3) Analysis of the Basic

Model

We

start by stating our assumptions about the variables definedand

discussed in the previous section (see also Table 1).Assumption

1: x>(l-l-a)I.For

the second project to be undertaken,we

need

to leave aminimum

amount

I as cash in the firm.We

thereforeneed

to prevent themanager from consuming

thisamount

in theform

of perks. This will cost aminimum

of al since themanager

can obtain exactly thisamount

byconsuming

I. Itisthereforeprofitable toundertakethesecondproject despitethisadditional cost.Assumption

2: I<yband

I<yg-y[,.The

first part of this assumption tells us that evenwhen

the state of nature is bad, there issufficientcash inthe firmtoundertakethesecondproject.

The

secondpartmakes

surethatwhen

we

choose a debt level equal toyg-I (see below), the firm defaults in thebad

state.Assumption

3: aI>5-l-Y.^ In otherwords,

it does not matterfor our purposesthatthe owner and the debt-holder are the

samepeople or not. Such separation

may

sometimes be important dueto otherforms ofincompleteness of contracts as shown in Dewatripont and Tirole (1992) or due togeneral equilibrium interactions as in Acemoglu (1993).Bearing in

mind

that5 is the cost of replacing the manager, this assumption implies that in theabsence ofadditional costs, itwill be in the interestof the

owner

to replace themanager

expost,even

when

anadditionalcostof intervention y isincurred.Without

thisassumption,shareholderswill neverfind it profitable toreplace the

manager and

we

will not beable to discuss theoptimal degree of separation ofownershipand

control.Assumption

4: al<u*<al+qa(yg-yb).The

left-hand side ofthis inequality tells us that ifthemanager

is only paid al in each state (theminimum

payment

necessaryforthe second project tobe

undertaken), this will notbe

sufficient tocompensate

her for choosing the high effort leveland

she needs to be paid somethingadditional.

The

right-hand side of the inequality tells us that ifadditionally she getstoconsume

the difference

between

the lowand

high returns in thegood

state, this willmore

than cover her reservation return. Sincea<l,

it also implies that it isworthwhile for theowners

to induce themanager

to choose the high effort level, e=l.Next

denote thesalaryof themanager

inthefirstperiodasWjand

recallthatthiscan onlybe

conditionedupon

whether

themanager

has servicedthe debt obligations but not directlyon

the realization of the state.

The

second period salary, W2(y), can be contingentupon

the finalreturns of the project denoted by y.

The

manager's expected return will be aEP-l-EW]4-Ew2(y)where

P

istheamount

of theperksconsumed

and

E(.)istheexpectations operator.Thisexpectedreturn needs to

be

larger than the relevant reservation returnand

because of the resource constraints, the salaries have tobe

non-negative.Proposition (Most Preferred Outcome):

In the

most

preferred scenario for the owner, themanager would

choosee=l

and

willbe

paidhis reservation return.

The

owner's returnwould

be(1) n^=^^+(l-^)7^+A'-/-u*

IIfb is the highest (first-best) return that the

owner

can achieveand

while choosing the organizationalform and

thecapital structure,theowner

will strive to reachthis amount.We

next analyze the optimalcontractsunder

differentorganizational forms,determinethemaximum

pay-off thatowners

can expectand

then proceed to the analysis of equilibrium organizational form.Lemma

1 (Full Managerial DiscretionWithout

Debt):With

full managerial discretionand

without debt contracts, themanager

is offeredyv^=0

^2)

^2^=0

ify<yi+x-I

w^{y)=ay^ ify^y^^x-I

He

choosese=l

and

retains control in both states.The

return of theowner

is(3)

n^=^l-a)7/(l-^)(l-a)7,+T-/

Proof:

Suppose

the return of the project is yt,.Without

an incentive contract themanager

canconsume

all ofthis as perks and get ccj^.To

encouragehim

to undertake the second investmentand

not toconsume

any perks, the incentive contractmust

payhim

at least this amount. If theinvestmentprojectisundertaken

and

no

perks areconsumed,

the return of the projectatt=2

willbe y^+x-I; this explains the first two

components

of Wj. Similarly,when

the return is yg, themanager

needs to be paid at least ccj^. Since themanager

is receivingmore

than his reservation return (assumption 4),he

prefers to exert efforte=l

and Wj is set equal to zero (as it cannotbe

negative).

The

expression for 11^ is straightforward.QED

Thiscasecorrespondstoaveryhighdegreeof separation ofownership

and

control.There

is

no

"hard"mechanism

for the control of the manager, and theowner

hasno

opportunity to intervene.As

a result, themanager

has full discretionand

the onlyway

to preventhim from

misusingthe

company

funds istowrite anincentive contract.But

sincethemanager

does not have any funds topay an entryfee, thisamounts

topayinghim

a rentor an "efficiency salary", not too dissimilar to an efficiencywage

a la Shapiroand

Stiglitz (1984).Although

there isno

socialinefficiency in thiscase, the

owner

isnot entirelyhappy

because partofherpotential returns arebeing paid to the manager^. This implies that the

owner

may

like to choose a different organizationalform

in order to reduce this rent.Lemma

2(Owner

ControlWithout

Debt):With owner

control without debt, themanager

is always replaced att=l, thus choosese=0

and

is paid

Wi=0.

The

firstproject is not undertaken,and

att=l

anew

manager

ishired.The

owner

makes

(4) n^=;r-5-Y-/

Of

course theresult thatthereis noinefficiencyisduetothe simplicityofour model. In general, inthe absenceof "hard"controlson themanagertherewillbe importantinefficiencies.Forinstance,sincereturnsare lower,fewercorporationwillbewilling toundertakethefirstinvestment.Thisisalsothereason

why we

refer toIIfb asthe first-nest result.Proof:

The

manager

cannotcommit

not toconsume

whatever is left in the firm.He

thus needsto

be

paid aminimum

ofalwhich

is larger than 8+

y. It follows that, irrespective of the effort leveland

the state ofnature, theowner

will always prefer to replace themanager

at t=l.As

aresult, the

manager

hasno

incentive to choosee=l

because his return, w,, does notdepend on

his effort. Therefore

he

is not paid anythingand

the return of the first project is zero.QED

This caseis the opposite of

Lemma

1.Although

themanager and

theowner

are separate agents, there isno

separation ofownershipand

control, so themanager

realizes thatwhen

hisinterests conflict with those of the owner, his interests will be ignored.

More

specifically,Assumption

3 implies that theowner

will find itprofitabletoreplace themanager

irrespective ofthe state ofnature.

As

aresult themanager

hasno

interestin supplying the high effort leveland

demands

hispayment

in advance (i.e. att=l

beforebeingfired).We

thusget a verystarkresultthatwith

owner

controland

without anyother instrument, theoutcome

is very inefficient.Note

a very important assumption; the salary of the

manager

cannot be conditionedupon

the realization of the returns afterhe leaves thecompany.

In practicethere is acommon

mechanism

that can

be

used tomake

thepayment

of themanager

conditionalupon

the returns after heleaves: to give

him

stockoptionsthatwill notbelost evenifhe

isfired.We

are thus assumingthatsuchstock optionscannot

be

used. Inourset-up there aregood

reasonsfornotrelyingtoomuch

on

such instruments. First, ifthe replacedmanager

could sellhisstock options in anuninformed

market

(i.e. amarket

that does not observe his initial effort level), stock optionswillprovideno

benefit. Second, supposethat the second

manager

who

is hired also needs to be given the right incentives.Yet,ifthedischargedmanager

hassubstantialstockoptionson

thecompany,

theowner

may

find it profitable not to give expensive direct incentives to the secondmanager

butmay

choose to

make

aside-dealwithhim

at theexpense of thedischarged manager. (In otherwords,giving the right incentives to the second

manager would

create a positive externalityon

the firstmanager which

theowner

willnotinternalize).Thiskindofconsiderationswill in general limitthe extent towhich

stockoptions canbe usedwhen

themanager

isexpected to quit''.An

alternative to stock options is severance pay for amanager

who

is dischargedwhich

we

will analyze later.The

above results are restrictive as theydo

not incorporate debt contracts.The

role of debt will be different in thetwo

organizational forms. Therefore our analysis will illustratetwo

related benefits of debt contracts for control purposes.

Stock options in practice are used more

commonly

as incentive contracts with directors ormanagersduring their tenure with the

company

ratherthan asa methodof inducing themto care about the value of thecompany

oncetheyare fired.Alternatively, ifwe

adopt Dewatripont andTirole (1992)'sassumption that intervention reduces theprivate benefits ofthe manager,stock optionswill notsolve the

incentive problem.

The

advantage of our set-up relative to those that rely on private benefits and theabsenceofperformancecontractsisthatitemphasizeswhichcontractscanactually solvetheproblem. For instance in thiscase ratherthan returns being non-contractible as inHart and

Moore

(1990a,b),we

just need the manager's renumaration not to depend upon the firm'sperformance afterhe leaves.Lemma

3(Owner

ControlWith

Debt):With owner

control,theoptimalcontractwould impose

adebtobligationofz=ygon

themanager

and

contingentupon

thepayment

of the debt themanager would

be paidWi=u*/q and

Wi=0

otherwise.

The

return of theowner

is(5) nojfqy^^(\-q)y^^x-u*-8-y-I

Proof:

The

abovecontactinduces themanager

tosupplye=l,

thusIIoD>no.He

ispaidexactlyhisreservation return butisalwaysreplaced.Thisimposesanadditional cost

5+

yon

theowner.QED

Thisillustrates thefirstuse of debtsimilar toAghion and

Bolton(1992), Hartand

Moore

(1989)and

Dewatripontand

Tirole(1992)^The

problem

inLemma

2was

thatdue

to lack ofjobsecurity, the

manager had no

interest in supplying a high effort level.Debt

makes

the return of themanager

contingentupon

his action (and the state of nature), therefore, if set at anappropriate (intermediate) level, it can give incentives to choosethe right level ofeffort

and

so,Hod

>

Ho-We

next turn to managerial discretion.Here

the role ofdebtwould

be to get the excess cash flow out of the firm as in Jensen (1986), Stultz (1991)and Hart and

Moore

(1990b).There

are three possibilities; (i) the

owner

can choose avery high level ofdebt such that themanager

always defaults, but this

would

putcontrol inthe handsof theowner

inbothstatessowe

go

backto the case with

owner

control. Therefore without loss ofgenerality,we

onlyconcentrateon

the othertwo

possibilities: (ii) the debt-level can be lowenough

thatthemanager

is neverforced to default. But, theowner

also wants the second projectto be undertaken so she has to leave I inthe firm''

and

hence, a low level of debtwould

correspond to z=yt.-I. (iii) the debt level can be chosensufficientlyhigh that themanager

is forced todefault inthebad

state but not in thegood

state,thus ahighlevel ofdebtisz=Vg-I.

We

willanalyze these twopossibilitiesseparately, starting with high debt.^ However

differently from these papers, it does not keep control in the hands of the manager.

Thusthiscontract canalsobe interpreted as a "coarse" incentivecontract ratherthandebt. This feature is

not shared by otherdebt contracts thatwill beconsidered in thispaper.

* Anotherpossibilitywould be to setz=ybbut alsopromise to inject I in the bad state. However,

there

may now

be an ex posthold-upproblem astheownercantrytoforce themanagerout.The

manager's contract would payhim nothingwhen

the returnsat t=2are equalto and thiswouldbe the case iftheowner doesnot put Ibackinto thefirm. She

may

thusbe able toinduce themanagerto quitvery cheaply.Inother words,sincethe assetisworthmoreinsomeoneelse'shandsthan the manager's, the owner would try to end the manager's tenure. Not to complicate the analysis

we

are not considering this case.An

alternative for the manager in this casemay

be to go to the debt market and raisemoney

with debtcontracts that mature at t=2; however in a more general model, outside debt holders

may

also want toreplace themanagerbeforeinjecting

money

into thefirm.Ifthepossiblehold-upproblemisavoidedinonewayor theother,thenouranalysiswouldstillapplybutthe exactformof theassumptionsandthecontracts

would need to change. For instance, in this case the second part of assumption 4 would become

u*<al+qa(yg-yb-l), etc.

Lemma

4 (Managerial DiscretionWith High

Debt):With

managerial controland

z=yg-I, themanager

is offered the following incentive contractq

and

choosese=l.

When

the state of nature isgood

themanager

retains controland

when

the state is bad, theowner

resumes controland

replaces him.The

owner's expected return is(7)

n^^=qy^^{\-q)y,^x-I-m-{\-q\h^'i)

which

is strictly greater than II^,, IIo,Hod-Proof:

The

manager

can onlymeet

the debtpayments

in thegood

state. His salary in this stateischosen to

meet

hisreservation returnand

tomake

the high effort choicesufficiently attractive.Since

he

is only paid his reservation return,when

W]>0,

hewould

prefere=0,

thusWi=0

and

allcompensation

has tobepaid in thesecond period.The

expectedvalue ofhis salary isu*and

theowner

also incurs the cost of replacement, 5and

intervention, y> in thebad

state.QED

We

saw

abovethattheowner

cannotcommit

not to replacethemanager

when

shehas the discretionand

organizational efficiency deteriorates as a consequence. This is theproblem

thatmanagerialdiscretion avoids.

As

aresult,when

shecando

so,theowner

willchoosea highdegreeof separation ofownership

and

controland

try to contain the manager's non-value maximizingobjectives by using incentive contracts

and

the capital structure rather than direct intervention.With

high debt, themanager

retains control in thegood

state but is forced to default in thebad

state.

Lemma

5 (Managerial DiscretionWith

Low

Debt):With

managerial controland

z=yb-I, themanager

is offered the following incentive contract^2^=0

ify<x

w^{y)=al

ifx<y<y-y^^x

w^{y)=aha{j-y^

ifryfYb'^x

The

manager

choosese=l,

retains control in both statesand

the owner's return is(9) IIa/lo=«^/(1-Q)yb^x-I-aI-

qaijfy^

Proof:

The

manager

canretaincontrol inboth statesbymaking

the debt payments.Ifhe

does notmeet

theseobligations,he

is immediatelyreplacedand

gets zero.Hence

heprefers to service the debt.When

the state is bad, there is only anamount

I in the firm sohe

is paid aland

when

thestate is good,

he

needs to be paid an additional a{y^-y^.Assumption

4 implies thathe

is paidmore

than his reservation return sow,=0.

QED

Because

alow level ofdebt is chosen, there is still excess cashand

themanager

is againoffered

an

attractive incentive contract in order to preventhim from consuming

this cash. Nevertheless, a low level of debt is useful because it always retains control in thehands

of themanager

(incontrasttohigh debtwhich

forces defaultinthebad

state).The

owner'sreturnislessthan EpB (and larger than IIo, 11^

and

Uqd), thus, though better thanowner

control, managerialdiscretion with debt is not perfect either.

At

this pointwe

can alsocompare

our result to the standard agency intuition that debt imposes a hard claimon

themanagement

(orsometimes on

the entrepreneur). In our context, although debt imposes such ahard claim

on

the manager, thesword

cutstwo

ways; debt also prevents too frequent interventions by outsiders(compared

toowner

control) sincewhen

themanager

makes

the required payments, he retains control. Therefore, debtprovides abalance ofpowersrather than unilateral control. This result illustratesour first claim that

when management

is delegated to agentswho

are not the residual claimants,it is often preferable to choose a high degree of separation of ownership

and

control so as toprovide discretion to those agents. Expressed alternatively, since the

manager

is not the residual claimantand

does not have the resources tobuy

the necessary assets, it is better to givehim

sufficient discretion so as to ensure that he can to

some

degree look after hisown

interestsand

so has an incentive to supply high effort.

Since both high

and

low debt levels have costsand

benefits,depending

on

the values of the parameters,one

or the othermay

be

preferred.The

cost of high debt is the additionalpayment, 8

+

y, that needsto bemade

and

the cost oflow debtlevel is that themanager

isbeingpaid a rent over his reservation return. In particular, the following result directly follows

from

Lemmas

4and

5;Proposition 1 (Equilibrium Organizational

Form

and

Capital Structure):If u*+(l-q){8+y)>oJ+qa(y -yi^), then managerial discretion with low debt is the preferred organizational structure. Otherwise managerial discretion with high debt level is preferred.

As

we know

from

Lemma

4,H^hd

is largerthanwhat

theowner would

obtainwith other organizationalformsand

financial structures, exceptIImld;managerial discretionwith eitherhigh or low debtis therefore optimal.From

this propositionwe

can seethat a high debtlevel ismore

likely, the higher is the difference

between

yg-yb, the higher area and

I,and

the lower are u*, Sand

Y-These

results arequite intuitive and exceptforthe balanceofpower

aspect,on

thewhole

similar to those of a

number

of other agencymodels

ofcapital structure (see Harrisand

Raviv(1990) for references).

The

largeris yg relativetoy^,, themore

excess cash low debt leaves in thefirm

and

the higher isa, themore

costlyis toinduce themanager

tomaximize

net presentvalue in the presence of this free cash flow.Both

of thesemake

a high level of debtmore

desirable. Since 8+

y is the cost of replacing themanager, it is not surprising that it discourages high debt.However,

anincreasein u* also discourages highdebt.To

seethis, recall that the benefitofdebtis toavoid theefficiencysalary. Ceteris paribus, asthereservation return of the

manager

goesup, the efficiency salary fallsand

there is lessneed

for a high level ofdebt.Our

assumption so far hasbeen

that theowner

cancommit

not to intervene at t=l.However,

the residual rights of control associated with ownership also give the right to fire theemployees of the firm provided that the pre-specified compensations are paid.

The

owner

may

therefore

be

unabletocommit

not tointerveneand

firethemanager

att=l

(scenarioB

V

Inthiscase,

we

willend-up

with the result ofLemma

3, rather than themore

desirableoutcomes

ofLemmas

4 or 5.There

may

betwoways

of preventingthisproblem^.First,we may

prepareacompensation packagefor themanager

such that it is not harmful tohim

to be firedand

more

importantly, itisnot beneficial tothe

owner

tofirehim.Thus, the contractatt=0

specifies aseverance (lay-off)payfor the

manager

equal to sand

it is onlyprofitable forthe owners to replace themanager

iftherentpaid

when

he

retains controlisgreaterthanthe costof replacinghim, 5+s-l-y (notethat the severance pay is only conditionalupon

whether themanager

is fired or not,and

also thatwhen

theowner

decides to intervene she incurs y)-The

next resultshows

that in ourmodel

severance paywill not be used because it distorts the ex ante effort level of the manager.

Lemma

6 (Disincentive Effects ofCompensation

Packages):Ifa

compensation

package offers themanager

a positive severance pay,he

would

choosee=0.

Thus

in equilibrium, theowner

chooses s=0.Proof:

Suppose

thatthe preferred organizationalform

is managerial control with high debt.Can

we

deter theowner from

intervening by havings>0?

InLemma

4 themanager

received hisreservation return.

Then

providedthats ispositive,hewould

bestrictlybetter offby choosinge=0

and

beingreplaced att=L

Thereforewe

cannotchooses>0

ifwe

want

toimplement

theoutcome

of

Lemma

4^. Alternatively supposethe preferred organizationalform

to be managerial controland

low debt as inLemma

5. In this casewe

need

a severance pay, s such that theowner

neverfindsitprofitable to intervene,thus

s>cd+a(y

-y^^yS-y.But

when

he keeps control, themanager

receivesa rentequal to al+qa(y -yf^)-u* whichissmallerthan al+a(y

-yi,)-8-y (since y issmall)

and

themanager

prefers to choosee=0

and

receive s.QED

This

lemma

establishes that the role ofseverance pay is extremely limited in our model.The

reason is that severance payamounts

to rewarding themanager

in the casewhere

he is^Anotherobvious candidateisreputationinrepeatedinteractionsbut

we

willnotpursuethishere.

^It

may

be conjecturedthatwe

cansolvetheproblem byincreasingtherentof themanagerwhen

he stayswith thefirm.However, thiswould increasethewillingnessofthe ownertofire the manager andthus increase the required severance pay 1-to-l.

replaced and,

when

this reward is high,he

will haveno

incentive to exert the high effort level'.The

secondway

of achievingowner

control is to increase thedispersion ofownershipin orderto passify the shareholders.The

intuition is simple.When

a shareholder intervenes ex post, allshareholders benefit, thus she is creating a positive externality.

A

large shareholderwould

beinternalizing a substantial part of this external effect. In contrast, if the largest shareholder is

small, the cost

may

outweigh the benefitand

each shareholdermay

prefer tobe

passive. In particular let us suppose that at t=0, theowner

sells the shares of thecompany;

she is still the largest shareholder (without anyloss ofgenerality)but onlyowns

aproportion/jl ofthecompany.

Calling an

EGM

will only beprofitable for her if ^i(aI-5)>Y or if/x(aI+a(yg-yi,))>Y,depending

on

the state ofnature.Thus

provided thatwe

choose/i low enough,we

will create a sufficientlyserious free-rider

problem

among

the shareholdersand

intervention will not take place. Therefore'";Proposition 2 (Optimal Dispersion of Ownership):

Suppose

that theowner

camnotcommit

not to interveneatt=l. If u*+(l-q)(8+y)>al+qa(y -y^),then at

t=0

theowner

will choose a low debt level, a disperse ownership such that the largestshareholder has jx less than

and

the shareholders receive the highest possible al+a(y -y^^ySreturnin thiscase,Umld- Otherwise,

mere

isahighdebtlevel, the largestshareholderowns

ix lessthan

—1—

ofthe sharesand

theowners

receive the highest possible return,IImhd-cd-8

Thisproposition

shows

thatthemain

trade-offcanbe thoughttobebetween

concentrated(centralized) ownership

which

leads to frequent interventionand

disperse (decentralized)ownership

which

gives significant discretion tothemanager and

thus requires othermethods

of control (such as debtand

performance contracts)". Intuitively,we

would

like tomake

themanagers

theresidualclaimantbutwe

cannotredistributepropertyrights. Instead,thisisachieveddefacto by reducing the control rights of theowners

and one

way

of doing this is tomuddy

theconcept of ownership by creating a disperse (decentralized) ownership structure.

Our

theory'

An

alternative thatavoidsthisproblemisto write acontractthat

bums

money

when

themanageris replaced. Thiswill

make

it costlyto fire the managerwithout giving the wrong incentives to him.We

assume that such contracts cannotbe written. Firstit is not possible towrite such wasteful contracts and

thenimplementthemexpost.Secondly,interventionbyshareholders

may

take non-contractibleformssuchasreducing the influence of themanager, etc.

'" Here

we

are discussing the optimal dispersion of ownership and controlin the absence of dividendpolicy asdefined inthe nextsection. In thepresence of dividendpolicy, dispersionofownership can help us achieve more than fullmanagerial discretion.

" Viewingthetrade-offin thiswaysuggests thatleveragedbuy-outswill actuallybeverybeneficial

since they allow the manager sufficient discretion while also imposing hard debt claims on him. I

am

grateful Jeremy Stein on this point. It can also be noted that a substantial part of the evidence on the

correlation betweenleverage andperformance comes fromLBOs. (e.g.

Dann

(1992)).therefore suggests thattherequired balanceof

power between

themanager and

the shareholdersis not only an important determinant ofcapital structure

and

incentive contracts but also oftheownership structure. Dispersion of ownership

may

be necessary to create free-rider effectsand

thus

commit

shareholders to passivity'^ This further emphasizes that theneed

for a balance ofpower

may

endogenously determine thedegree towhich

control is separatedform

ownership. Italso reverses the conventional

wisdom

thatmanagers

have substantial discretion because ownership isdisperse. In our model, ownership hastobedisperse to allow theowners

tocommit

to sufficient managerial discretion.4) Benefits

from

Owner

Interventionand Optimal

Dispersion ofOvmership

Inthe basic

model

analyzed above,owner

interventionisneverbeneficial. Thisis becausewhenever

the owners have the right to intervene theywant

to replace themanager and

thisdistorts ex ante incentives.

However,

this set-upwas

chosen in order to highlight themain

resultof the paper that disperse ownership has important benefits

from

the point of view of organizational efficiency.Itisstraightforwardtointroducebenefitsoflargeshareholdersand

thus obtain an intermediate level of dispersion as the equilibrium (or theoptimum).

This iswhat

we

will

do

in this section. Yet, rather than introducenew

features to the model,we

will relax an assumptionofouranalysissofarthatwas

made

forconvenience. In the basicmodel,the onlyway

that the free-cash flow could begotten outside the firm

was

by debtservicing.However,

there isno

reasonwhy

themanager

should be unable to pay outsome

of the cash voluntarily. In thissection

we

willallowforthispossibilitywhich

we

thinkof as"dividendpolicy"or stockrepurchasesby the manager.

Note however

that thesenames

are chosen mostly for convenience since dividendsand

stock repurchases in practice havemany

other rolesand

characteristics that ouranalysis does not capture (also see footnote 13). First note that since the state ofnature is still

non-contractible, a dividend contract conditional

upon

the state of nature cannot be written.However,

themanager

may

choosethe level of dividend to bepaid out after the state ofnatureis revealed. If dividends are determined at the

same

time as theconsumption

of perks, themanager

will haveno

interest in paying out dividendsand

we

go

back to the results of the previoussection.The

alternativeisthat as soonasthestateofnatureisrevealed, themanager

canprecommit

topaying-outa certainamount

ofdividendand

cannot renegeon

thiswhen

the returns are actually realized (see Figure 1). It is suchprecommitment

thatwe

refer to as "dividendIfthe boardofdirectorsrepresenttheshareholders'interests, passivity

may

notbepossible even with disperse ownership, thusourtheoryalsosuggeststhattheremay

be anoptimaldegreeof"congruence" betweenthe interestsoftheboardofdirectorsandthe shareholders. Ihope topursuethis infuture work.policy"'^.

Precommitment

may

take avery simple form; for instance ifthemanager announces

a dividend leveland

then does not paythis, theowner and

other claim-holdersmay

intervene, firethe

manager

or even sue him. This interpretation emphasizes that institutional factors willdetermine

whether

dividend policy can play this role or not'"*.Proposition 3 (Optimal Dispersion of

Ownership)

In the presence of"dividend policy", the debtlevel is set at z=yb-I, the largest shareholder holds a proportion /i=^t*=

^

ofthe total sharesand

themanager

is offered the followingu*-{l-q)al-q8 contract w^{y)=Q if

y<x

(10)wAf)-aI

ifx<y<x-.tllELL

a

IX*a

the

manager

choosese=l,

alwaysmakes

the debtpayment

att=l and

in thegood

state pays-outy

_ V—

SFL

.There

is never any interventionand

the owners receive IIfb.^

ag

Proof:

The

largestshareholderwillwant

tointervenewhen

herbenefitisgreater than y. Thiswillbe

thecasewhen

^l.(w2(y)-5)>

y•By

interveningthecompany

savesW2(y)and

loses8and

thelargestshareholder getsaproportionfx ofthis.

For

the first-besttobe achieved themanager

needstobe

paid exactlyhis reservation return. Sincein the

bad

stateheispaidal, forthefirst-best, hissalaryinthe

good

stateneedstobe reducedto u*-(l-q)Q:I/q.But

when

/jlisequal to/x*and

themanager

signs contract (10), in equilibrium, he is exactly paid his reservation return. In the

bad

state the largest shareholder finds it profitable not to intervene, but shewould do

so in thegood

stateunless

some

money

is paid out. Anticipating this, themanager

is forced to payjustenough

tomake

the largest shareholder not interveneand

thus needs to pay-outy

-(u*-(l-q)cd/q)/awhich

leaves justenough

to satisfy the terms of his contractand

in thegood

state, he receives W2=u*-(l-q)Q!l/q. Alsoknowing

ex ante that hewill be able to receive his reservation return, themanager

accepts the contractand

chooses high effort.QED

This proposition therefore determinesthe optimal dispersion ofownership by balancing

"

As

thisdiscussionmakesclear,"dividends"willonlybeusefulwhen

theyare quiteflexible. Sincemany

financialeconomistsview dividendsasquiteinflexible,stock repurchasesmay

correspondmore

closely to whatwe

call "dividends" here. Alternatively, if the manager has sufficientlylong-horizon and has the discretion tochoose the debt level each period, this choicemay

also act similar to dividendshere;when

there is excesscash flow, the manager would choose ahigh level ofdebt toprevent intervention. Also as

awordofcaution note thatBlanchardetal (1993)inthehempirical investigation find thatintheirsample offirms the excess cash flow was never paid to the shareholders but was insteadwasted in a

number

ofdifferentways. '* Even

when

paying out cash is not an option, large shareholders will have other monitoringbenefits and asimilar result to Proposition 3 can beobtained by incorporatingthese.

thebeneficial effects of

owner

intervention (i.e. centralized ownership reduces the rents thatthemanager

has to be paid)and

the costs ofsuch intervention (i.e. distortions in the ex ante effortchoices).

5) Application:

The

Threat ofTakeoversand

Organizational EfficiencyWe

now

turnto an application of these ideas. Letus suppose that takeovers are possibleand

that a raider canmake

an offer to the shareholders at any stage ofthe firm's life. This is a potentiallyimportantapplicationbecauseoftworeasons.First,takeovers oftenchange

thebalanceof

powers

within the organization thus their impacton

organizational efficiency requires explicitattention tothe costs

and

benefitsofthepre-existingbalances. Secondly, anumber

ofeconomistsare skeptical that large shareholders can be effective monitors

and

attribute the monitoring role to raiders (e.g.Manne

(1965), Jensen (1986,1988), Scharfstein (1988)). According tothisview ifthere is too

much

excess cash flow in the firm, a raider canmake

an attractive offer to the shareholdersand

acquire thecompany.

We

model

takeoversin avery simple way.The

raiderhastoincurthe costof replacing themanager,8

and

there is also an additional cost of takeover incurredin theprocess ofacquisition (a deadweight loss in the value of the firm).We

denote this cost by/3 (and also ignore the costofintervention, y).

As

totheissueofhow

toshare thegainsfrom

takeover,we

simplyassume

that theowners

receive a proportiono

of the net gains (i.e. after)8 is deducted)and

the rest goes to the raider. Empirical evidence suggests thata

is close to 1, but our resultsdo

notdepend on

the value ofa

(aslong as there areno

significant sunk costs incurred by the raider, see below). Also note that in order to focus attentionon

the interaction between takeoversand

organizational form,we

are assuming in this section that either ScenarioA

appliesand

theowners

can choosethe governance structure that

most

suitsthem

or that ScenarioB

appliesand

the owners havealready sold sharesto achieve managerial discretionthrough dispersion ofownership. Therefore,

in thissection,

we

will completelyignoreissuesrelated toowner

intervention.Also notethatevenifthere are

many

owners, theyall share thesame

preferences regarding organizational structureand

we

can treatthem

asone

owner

in so far as decisions att=0

are concerned.Since the

incumbent

manager's humzin capital is essential, a takeovercan onlyhappen

ator aftert=l.

However,

ifatakeover is expected tohappen

after t=l, themanager

willconsume

all the perks before this takeover offer, thustheraider