Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

m-^.^B

working paper

department

of

economics

«iiiiK_

CONSEQUENCES OF EMPLOYMENT

PROTECTION?

THE

CASE

OF

THE

AMERICANS

WITH

DISABILITIESACT

DaronAcemoglu JoshuaAngrist September1998

massachusetts

institute

of

technology

50 memorial

drive

Cambridge,

mass. 02139

WORKING

PAPER

DEPARTMENT

OF

ECONOMICS

CONSEQUENCES OF

EMPLOYMENT

PROTECTION?

THE

CASE

OF

THE

AMERICANS

WITH

DISABILITIESACT

Daron Acemoglu JoshuaAngrist 98-13 September1998MASSACHUSEHS

INSTITUTE

OF

TECHNOLOGY

50

MEMORIAL

DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE,

MASS. 02142

MASSAC

~

-STlTintC^ - 5Y

JAN

2 8 '959First Version;

December

1997Revised:

June

1998Consequences

of

Employment

Protection?

The

Case

of

the

Americans

with

DisabiHties Act'

Daron Acemoglu

and

Joshua

Angrist^

ABSTRACT

The

Americans

With

DisabiHtiesAct

(ADA)

requires employers toaccommodate

disabledworkers

and

outlaws discrimination against the disabledin hiring, firing,and

pay.Although

theADA

was

meant

to increaseemployment

of the disabled, it also increases costs for employers.The

net theoretical impact turnson

which

provisions of theADA

aremost important

and

how

responsive firm entry

and

exit is to profits. Empirical results using theCPS

suggest that theADA

had

a negati\-e effecton

theemployment

ofdisabledmen

ofallworking

agesand

disabledwomen

under

age 40.The

effects appear to be larger inmedium

size firms, possiblybecause

small firms were

exempt from

theADA.

The

effects are also larger in stateswhere

therehave

been

more

ADA-related

discrimination charges. Estimates ofeffectson

hiringand

firingsuggestthe

ADA

reduced hiring of the disabled but did not affect separations. This weighs againsta pure firing-costs interpretation of the

ADA.

Finally, there is httle evidence ofan impact on

the nondisabled, suggesting that the adverse

employment

consequences of theADA

have

been

limited to the protected group.

'We

thank Lucia Breierova and Chris Mazingo for outstanding research assistance, and Patricia Anderson,Peter Diamond, Alan Krueger, Paul Oyer, James Poterba, Steve Pischke and seminar participants in the

N.B.E.R. Labor Studies Meeting, the 1998 North American Meeting of the Econometric Society, M.LT. and

U.C.L.A. for helpful comments. Special thanks go to to Leo Sanchez for help with data from the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission and to Greg Weyland at the Census Bureafor consultations regarding

CPS

matches and theCPS

redesign. The authors bearsole responsability for the contentsofthis paper.^Department ofIkonomics, MassachusettsInstitute ofTechnology.

I.

Introduction

Government

efforts to eliminateemployment

and

wage

discrimination dateback

to theEqual

Pay

Act

of 1963and

Title VII of the Civil RightsAct

of 1964.These

laws prohibiteddis-crimination

on

the basis of raceand

sex.The

consensusamong

labor economists is that civilrights legislation

and

related federaJ regulations led to a substantialimprovement

ineconomic

conditions for Black

Americans

(see, for example,Freeman,

1981;Heckman

and

Payner, 1989;or Leonard, 1990), while the evidence

on

theimpact

of antidiscrimination policyon

women

isless clear cut (Leonard, 1989).

The

most

recentpieces offederal antidiscrimination legislation aretheAmericans with

Dis-abilities

Act

(ADA)

and

the Civil RightsAct

of 1991(CRA-91).

The

ADA

requires employersto offer reasonable

accommodation

to disabled employees,and bans

discrimination against thedisabled in

wage

determination, hiring,and

firing.The

ADA

seems

tobe

more

far-reachingMian

CRA-91,

which

essentially modified existing antidiscrimination statutes.^ADA

propo-nents

hope

the act willimprove

the labormarket

fortimes of disabled workers. Critics of theADA

have argued that adapting the workplace to the disabled canbe

expensiveand

that thecosts of

accommodation

and ADA-related

litigationmay

have

significant negativeemployment

effects (e.g., Rosen, 1991; Oi, 1991; Weaver, 1991; Epstein, 1992; Olson, 1997).

The

first objective of this paper is to evaluatewhether

theADA

has in factimproved

economic

conditions for the disabled.A

study of theADA

is also ofbroader interest, however.Altliough high-profile reasonable

accommodation

cases have attracted themost

media

atten-tion, the majority of

ADA

charges are for wrongful termination. It is therefore possible thatthe

ADA

acts as aform

ofemployment

protection, similar toEuropean

firing costs. Since theADA

primarily affects a specific group, the consequences ofemployment

protectionmay

be

easy to detect in this case. Moreover, contrary to early experience with the Civil Rights

Act

of 1964, in recent years,

most

discrimination chargesunder

all statuteshave been

related towrongful termination

(EEOC,

various years). If firing costs havedisemployment

effects, thenthis

change

in civil rights law enforcementmay

ultimatelyharm

protected groups otherthan

the disabled, a possibiUty raised

by

Donohue

and

Siegelman (1991, 1993).The

theorysection ofthe paperuses astandard competitivemodel

tohighlight thedistinc-tion

between

hiringand

firingcostsdue

tothe threat oflawsuitsand

thecosts ofaccommodating

disabled workers.

Although

the reasonableaccommodation

provision createsan

incentive toemploy

fewer disabled workers, the introduction of hiringand

firingcostscomphcates

theanaly-sis. If the threat of

ADA-related

litigation encourages employers to increase the hiring of thedisabled,

and

if thenumber

of employers is not very responsive to profits or costs, theADA

may

increase theemployment

of disabled workers asADA

proponentshad

hoped.But

when

most

charges are for wrongful terminationand

costs of reasonableaccommodation

are high,the

ADA

is hkely to reduce disabledemployment.

The

empirical analysis looks at the emplojonentand wages

of disabledand

nondisabledworkers using

data

from

theMarch

Current Population Surveys(CPS)

for 1988-1997.These

data are useful for our purposes because the

CPS

income supplement

identifies disabledwork-ers,

and

because theMarch

CPS

has informationon

firm size, a variable that figures in ourtheoretical discussion,

and

in theADA's

complianceand

sanction provisions.To

investigatethe

impact

of theADA

on

turnover,we

constructmeasmes

of separationsand

accessionsby

matching

CPS

rotation groups. Finally,we

useEEOC

dataon

discrimination chargesby

stateto connect changesin labor

market

variables with the incidence ofADA-related

chargeactivity.The

empirical results suggest that theADA

had

a negativeimpact

on

theemployment

of disabled

men,

withno

effecton

wages.These

results areunchanged by

controlling forpre-ADA

trends in disabledemployment

and

for the increase in the fraction of people receivingDisability Insurance (DI)

and Supplemental

SecurityIncome

(SSI). In contrast to the resultsfor

men,

the results forwomen

are mixed.The

ADA

appears to havehad

a negative effecton

women

aged 21-39, butno

effecton

women

aged 40-58.We

also findno

evidence that theADA

liad a ncgati\-e impact

on

nondisabled workers inany

age group, suggesting that the adverseconsequences of the legislation in this case have been limited to the protected group.

We

check the basic findings in anumber

of ways. First, there issome

evidence thatcmplo\'mcnt of the disabled declined

more

inmedium-size

firms, possiblybecause

small firmsare

exempt

from theADA

and

large firms canmore

easily absorb the costsimposed by

theADA.

Second, effects are generally larger in stateswhere

therehave

been

more

ADA-related

discrimination charges. Finally, there is

some

evidence of a negativeimpact

on

hiring of thedisabled, but little evidencefor a reduction in disabled separation rates. This suggests that the

negative effects of the

ADA

may

bedue

more

to the costs ofreasonableaccommodation

than

to the threat of wrongful termination lawsuits.

The

paper

is organized as follows. Section II givessome

background

and

discusses relatedliterature. Section IIIprovides a theoretical analysis ofprovisions that protect disabledworkers.

Section

IV

describes the dataand

oxn empiricalstrategy. SectionV

containsthemain

empiricalII.

Background

A.

ADA

Provisions

and

Coverage

The

ADA

was

signed into law in July 1990and

came

into effect in Jnly 1992. Previously,there

was

no

federal law dealing with theemployment

and wages

of disabled workers in theprivate sector, although the Rehabilitation

Act

of 1973 covered disabled workersemployed by

the federal

government

orworking

for federal contractors.A

number

of states alsohad

lawsprotecting disabled workers, but the coverage

and

effectiveness ofthese laws varied. Title I ofthe

ADA

initially covered all employers with at least twenty five employees. In 1994, coveragewas

extended to employers withfifteenormore

employees. Title Irequires employers to provide"reasonable

accommodation"

for their disabled workers.Examples

includeenablingwheel

chairaccess, purchasing special

equipment

for disabled employees,and

job restructuring to permitdisabled employees to

work

part time orfrom

home.

Title I alsobans

discrimination againstthe disabled in wages, hiring, firing,

and

promotion. For example, a disabledemployee

shouldbe

paid thesame

amount

as a nondisabled worker in thesame

job,and

firms are not allowedto consider disability in hiring

and

firing decisions.^Enforcement

ofADA

provisions is left to theEqual

Employment

Opportunity

Commission

(EEOC)

and

the courts. Disabled employees or job applicantswho

believe theyhave been

discriminated against can file a charge with the

EEOC,

which

will investigateand

insome

cases try to resolve the charge or sue. If the charge is not resolved

and

theEEOC

does notsue on behalf of the charging party, it issues a letter of permission to sue

and

the chargingparty is free to litigate at his or her

own

expense.The

law provides for remedies that includehiring, reinstatement, promotion, back pay, front pay,

and

reasonableaccommodation, and

forpayment

of attorney's fees, expert witness fees,and

court costs.As

aconsequence

ofCRA-91,

compensatory and

punitivedamages

are also available if intentional discrimination is found.These

rangefrom

$50,000 for firms with 100 or fewer employees to $300,000 for firms with 500or

more

employees(EEOC,

1995, p. X-8).The

underlying logic of theADA

seems

tobe

that employers incorrectly perceive thedisabled to be less productive, or are unwilling to

make

modest

adjustments toaccommodate

them

(see, e.g.Kemp,

1991).The

fact that the labormarket

fortunes of the disabled aremuch

worsethan

the nondisabled is not in dispute.The

disabled earn 40 percent or less ofwhat

nondisabled workers earn. Their labor force participation rates aremuch

lowerand

theyare

much

less likely tobe employed

(see, e.g.,Burkhauser and

Daly, 1996, or our statistics,^xitle II covers discrimination in public programs, and Titles III and FV refer to public accommodations

(busmesses) and telecommuiucation. Title

V

contains technicalinformationrelated toenforcement (seeEEOC

below).

ADA

proponents believe the law will inducecompanies

tomake

the investmentsand

modifications necessary to

employ

disabled workers,and

reduce imjustified discrimination. Inrecent years, interest in the labor

market performance

of the disabled has alsobeen

fueledby

efforts to reduce the

number

ofDisability Insurajice recipients (see, e.g., Leonard, 1991)From

July 1992 toSeptember

1997, theEEOC

received 90,803ADA

charges(EEOC,

various years).

Of

these, 29 percentmention

"failure to provideaccommodation",

while 9.4percent are fordiscrimination at the hiring stage.

The

majority ofcharges, 62.9 percent, areforwrongful termination (i.e., discharge, failure to rehire, suspension, or layoff). This motivates

our interpretation of the

ADA

as providing aform

ofemployment

protection.B.

How

Costly

isthe

ADA?

We

have notfoimd

representative dataon

the costs ofaccommodation,

though

thePresiden-t's

Committee

on

Employment

of People with Disabihties has surveyedsome

employers

who

contacted

them

for helpaccommodating

their disabled workers (JobAccommodation

Network,

1997). This survey

shows an

average cost of $930 peraccommodation

sinceOctober

1992.Other

costs ofaccommodation

include time employersspend

dealingwith

ADA

regulationsand

reduced efficiencydue

to a forced restructuring.An

importantcomponent

ofADA

costs resultsfrom

the threat of litigation. Since July1992, over 11,000 of the charges brought

under

theADA

were

resolvedby

theEEOC,

and

employers paid over $174 million in settlements

(EEOC,

various years).This

figiue does notreflect administrative costs, lawyers fees,

and

private settlements in or out of court.Although

we

do

not have dataon

ADA

suits alone,Condon

and

Zolna (1997) report thatemployees

fileover40,000 cases eachyear withstate

and

federal courts, themajorityrelated todiscrimination,and win

almost 60 percent of the time.They

estimatedan

averageaward

ofover $167,000and

defence costs ofover $40,000 (less than the $80,000 estimated

by

Dertouzos, 1988, for wrongfultermination suits in California).

The

ADA

may

alsohavebeen

a factor in thedevelopment

ofanew

insurance market,poli-cies for

Employment

Practices Liability Insurance (EPLI),which

covers the costs ofemployee

lawsuits.

The EPLI

market

started in late 1990and

has sincegrown

rapidly, withminimum

premia

rangingfrom

$4,500 to $20,000 a year (Clarke, 1996). This suggests that the costs ofC.

Related Literature

DeLeire (1997) is the first systematic empirical study of the

impact

of theADA

thatwe

areaware

of.He

used the Siurvey ofIncome and

Program

Participationand

the Panel Siu-vey ofIncome

Dynamics

tocompare

labormarket outcomes

for disabledand

non-disabled workersbe-fore

and

after theADA.

Our

approach

uses different dataand

anumber

ofempirical strategiesnot explored

by

DeLeire, butwe

also begin with similarcomparisons

of changes inoutcomes

by

disability status. Since theADA

creates firing costs, ourpaper

is also related to empiricalwork on

theimpact

of firing costs inEurope

(e.g., Lazear, 1990;Addison

and

Grosso, 1996;and

Nickell, 1997). Related theoretical papers include analyses of labormarket

regulationsby

Mortensen

(1978),Summers

(1989), Lazear (1990), Bertolaand Bentohla

(1990),and

Hopen-hayn and Rogerson

(1993),and

the analysis of optimal disability benefitsby

Diamond

and

Slieshinski (1995). Finally, our

work

is also related to the empirical hteratureon

theimpact

ofmandated

benefits (e.g., Gruber, 1994;Ruhm,

1996; Waldfogel, 1996) and, asnoted

above, toanalyses of the

impact

ofearlier civil rights legislation.III.

Consequences

of

Protecting Disabled

Workers:

Theory

The

theoretical consequences oftheADA

areexplored usingastandard competitivemodel

withtwo

types of workers. Nondisabled workers supply labor according to the function na{wa)and

the disabled supply labor according to nii{wd),

where Wa

is thewage

receivedby

nondisabledworkers

and

wj^ is thewage

rate for disabled workers.We

assume

that n, is increasing in thewage

rate for i=

a.d. All workers are infinitely livedand

risk-neutral,and

have

a discountfactor

P <

I.There

areM

firms in the labormarket

which

never exit,and

a largenumber

ofpotential firms that can enter at cost F. This is a convenient formulationenabling us to discuss

both

amarket

characterizedby

free entry(when

M

—^ 0)and one where

thenumber

offirmsis fixed

{M

>

and

F

—

oo).All firms are risk-neutral, discount the future at rate P,

and have

access to the productionfunction F{Lt,Dt),

where

Lt is thenumber

of nondisabled workersand Dt

thenumber

ofdisabled workers

employed

at time t.We

alsoassume

that with probability s every period, theproductivity of a worker at his or her current firm falls to zero,

though

productivity elsewhereis imaffected (this

may

be

due, for example, to match-specific learning as in Jovanovic, 1979).We

assume F{Lt,Dt)

=

^m

+

eD^)^

,where

a

<

1,and

<

p<

1.The

quantities Ltand Dt

include only employeeswho

have not received adversematch

specific shocks.The

parameter

e captures the relative productivity of disabled workers. For example,when

p=

1a lower marginal product

than

nondisabled workers. This formulation cdso nests the case inwhich

firms discriminate against the disabled for taste reasons as in Becker (1971).The

issiie raisedmost

often inADA

charges is wrongful termination, followedby

fail-ure to provide reasonable

accommodation

and

discrimination in hiring.Suppose

disabled jobapphcants

who

are not hired sue with probability pd at expected cost v^-, includingdamages

and

lawyer fees. Rejected nondisabled applicants can also sue, falsely claiming tobe

disabled,and

thishappens

with probability paand

has cost Ua-The

expected cost of not hiring adis-abled worker is therefore hd

=

Pdi'd, while the corresponding cost for a nondisabledworker

isha

=

Pa^a-We

refer to haand

hd as hiring costs,though

more

precisely, these are costs thatthe firm incurs

when

it decides not to hirean

applicant.A

disabledworker

who

is fired sueswith probability qd for

damages

(pd- For a nondisabled worker, the corresponding probabilitiesand

damages

are qaand

0a, so the expected costs of firing a disabledand

nondisabledworker

are fd

—

qd<Pdand

fa=

qa4>a-We

begin with the simple casewhere

all costs arepure

waste,so h

and /

act like a taxfrom

the point of view of the workerand

the firm,though

suitsmay

benefit

some

other party such as lawyersand

insurance companies. Thisseems

like a reasonablestarting place since a significant fraction of the litigation costs

imposed

on

employersprobably

do

not get transferred to disabled workers. Obviously, a fraction of these costsdo

accrue toworkers, giving

them

a reason to sue, butwe

defer a discussion of this case.We

assume

that (1—

/?) /„<

Wa and

(1—

/5)/^<

Wd,which

implies that firms alwayswants

to lay off the fraction s of its employees wlio receive adverse match-specific shocks.We

alsoassume

there is an excessnumber

of applicants for every job, Dp- ofwhom

are disabled,and

Lp

are nondisabled.We

treatDp

and

Lp

as given. Finally,we

assume

that firmscan

"accommodate"

disabled workers, forexample by

purchasing specialequipment

at costC

perworker,

and

that this expenditure increases the marginal productivity of disabled workersby

a fixed

amoimt

B

per worker.The

ADA

requires employers tomake

suchaccommodations.

IfC

<

B, employerswould

make

these adjustments voluntarily, even in the absence of theADA.

The

fact thatgovernment

regulation is required suggests that typicallyC

>

B.The

maximization problem

of the firm at time t=

canbe

written as:max

n

=

^P'[F{LuDt)-Wa,tLt-Wd,tDt-cDt-fasLt-,-fdsDt_,

(1){Dt,Lt}

^^Q

-ha

{Lp

-

[L,-

(1-

5)L<_i])-

hd{Dp

- [A -

(1-

5)A-l])]where L_i

=

D_i

=

0, Wa^tand

Wd^t denote nondisabledand

disabledwages

attime

t,and

c

—

C

—

B

is the net cost ofaccommodation

after theADA.

Pre-ADA

firingand

hiring costswage

bill,accommodation

costsand

firing costs.Firms

dischargeafraction s oftheiremployees

who

receivean

adversematch-specific shock, incurringafiringcost of fj foreachdisabled layoff,and

fa for every nondisabled termination.The

second line gives the "hiring costs" the firmincurs as a function of the

number

workers not hired out of the applicant pools,Lp

and

Dp-When

Lt—

Lt-\and Dt

=

Dt-\ so thatemployment

is not changing, the firm hires sLt-\nondisabled

and

sDt-i workers to replace thosewho

are laid off.As

noted above, haand

hd.act as hiring subsidies, because the firm reduces its costs

by

hiringmore

workers.Since

adjustment

costs are linearand

there isno

aggregate imcertainty, firmsimmediately

adjust to steady state

employment

levels,and

Wa^t=

Wa, Wd,t=

"^d, Lt=

L,and

Dt

=

D

\nevery period.

These equihbrium

employment

and

wage

levels satisfy:LP-'[U

+

eD''p'

=

Wa

+

(5sfa-[l

+

P{l-s)]ha

(2)eD"-'

[L"+ eD"]^

=

Wd

+

psfd-[l

+

^{l-

s)]hd+

c.Both

equations equate the relevant marginal product to the flow marginal cost, inclusive offiring costs, hiring subsidies,

and

the net costs ofaccommodation..

To

determine equilibrium,we

alsoimpose market

clearing for nondisabled workers,n~^

[mL)

=

Wa, (3)where

r?"' is the inversesupply functionand

m

is the equilibriumnumber

of firms.The number

of firms is determined

by

n <

r and

m

>

M,

(4)which

holds withcomplementary

slackness. Thismeans

that either themaximized

value ofprofits is equal to entry costs, or that there is

no

entryand

thenumber

offirms,m,

is equal tothe

minimum,

M.

Finally, the

wages

receivedby

disabled workers are givenby

Wd

=

max

[n^^(mD)

,T]Wa , (5)where

7] is a parameter. In the absence of theADA,

t]=

and

there areno

restrictionson

disabled wages.

The

equalpay

provision canbe

interpreted as setting 77=

1.Inspection ofthe equilibrium conditions yields the following conclusions:

1)

From

(2), it isclearlypossiblefor theADA

to reduce thecosts ofemploying

thedisabled,sincehd iseffectively ahiringsubsidy.

The

scenarioenvisagedby

ADA

proponents

can probably

be

best described as hd>

0, fa=

ha=

0,and minimal

firing costs for the disabled, inwhich

as long as

p>

0, theADA

will reduce nondisabledemployment

eindwages

in this case,though

this effect is likely to

be

small.2)

As

we

noted

in Section II, theADA

appears tohave

increased fd considerablymore

than

hd. Similarly, costs ofemploying

the disabled are increasedby

theaccommodation

costs,c. Therefore, in practice, the

ADA

may

be

more

likely to reduce disabledemployment and

wages.

3)

The

equal-pay provision of theADA

(i.e. r/>

0)may

have

increased disabled wages,creatinginvoluntary

unemployment

offthe disabled supply curve.The

equal-payprovision alsointeracts with firing costs

and

the costs ofaccommodation

by

preventingwages from

faUing tooffset these costs, exacerbating the

dechne

in disabledemployment.

4)

Although

the partial-equilibrium effect of hiring costs is to increaseemployment

ofthedisabled, the implicit hiring subsidy hd is effectively financed

by

reducing profits. Ifm

>

M

and

n =

r

to startwith, thenan

increasein hd will causesome

firms to shutdown,

causingboth

disabled

and

nondisabledemployment

and wages

to fall.More

generally, the contrastbetween

the free-entry

and

fixed-number cases suggests that theADA

will reduceemployment

most

infirms or uidustries

where

profits are close to entry costs. In the empirical work,we

use firm sizeas a

proxy

for excess profitability, since large firms aremore

profitable (see, e.g., Schmalensee,1989; Scherer

and

Ross, 1990,Chapter

11).5) Finalh', the

ADA

might

also affectemployment

by

changing firingand

hiring costs fortlic nondisabled.

/

and

ha-The

discu.ssion so farpresumes

that/ and

h act like taxeson

the firm-worker relationshiprather than a transfer

from

the firm to the worker.We

know

from

thework

ofMortensen

(1978)

and

Lazear (1990) thatwhen

/ and

h are pure transfersand

sidepayments

are allowed,firing costs should have

no

effecton

employment.

To

see this in our context,suppose

thatfa

=

ha=

hd=

and

/d>

0.Under

theassumption

that fd is apure transferand

both

partiesare risk-neutral, labor supply of disabled workers changes to

nd[wd

+

13sfd)-The

reason forthe

change

is that workers anticipate theymay

be

fired,and

therefore include the discountedfiow value of firing costs, /3s/d, in their

employment

income. It is straightforward to see thatas long as

Wd

can falland

keepWd

+

0s

fd constant, changes in fdhave no

effecton

disabledemployment.

However, the equal-pay provision of theADA

limits this possibility. Moreover,because

/ and h

may

includepayments

to third partiesand

because firmsand

workers arerisk-averse, characterizing these costs as a tax

on

theemployment

contractseems

like a betterstylized description of reahty.

because separations are exogenous. In a previous version ofthe

paper

(details availableupon

request),

we

allow for time-varying productivityand

endogenous

separations. This analysisshows

thatADA-related

firing costs arelikely to reduceboth

hiringand

separations.The

theoretical discussion thereforeshows

that the net effect oftheADA

depends on which

provisions are

most

important.The

accommodation

and

firing costsimposed

by

theADA

axelikely to reduce

employment,

while hiring costshave

the opposite effect. If the equal-payprovision is not binding,

equiUbrium

ison

the labor supply curves of disabledand

nondisabledworkers,

and

employment

declinesareaccompanied by

wage

declines.More

generally, however,the equal-pay provision can create "involuntary

imemployment"

off the supply curve.We

therefore estimate reduced-form equations of the form:

y^t

=

x[^(3+

6t+

-ita,t+

E^t, (6)where

i denotes individualsand

t time; yu isweeks worked

or averageweekly

wages;and

Xiiis a set of controls including disability status.

The

term

5t is a year effect to control forchanges in aggregate conditions. Finally, a^t is the interaction of a disability status indicator

and

adummy

forpost-ADA

years.The

coefficient 7^measures

theimpact

of theADA

on

the disabled using the nondisabled as a control group. Since the

ADA

potentially affects theemplo}'mcnt of nondisabled as well as disabled workers,

we

also exploreempirical specificationsthat use \'ariation

by

firm sizeand

state to separately identify effectson

the disabledand

nondisabled.

IV.

Data

and

Descriptive

Statistics

The

sample

isdrawn

from theMarch

CPS's

from 1988 through 1997,and

limited tomen

and

women

aged 21-58, since this age group has strong labor-force attachment. Disabled workersare identified in the

March

CPS

Income Supplement by

the question:"Do

you have

a healthproblem

or disabilitywhich

preventsyou

from workingorwhich

limits the kindand

theamoTmt

of

work you

can do?". This question hasbeen

usedby

other researchersworking on

disabilityissues (e.g.,

Krueger

and

Kr\ise, 1995),and

is similar to disabiUty questions in thePSID

and

SIPP

(see, e.g.,Burkhauser

and

Daly

1996; DeLeire, 1997).^The

impact

of theADA

on

employment

levels is evaluatedby

looking atdata

on weeks

worked

diiring the previous calendar yearfrom

theMarch

income

supplement.The

wage

measure

isaverage weekly earnings,computed

using annual earnings datafrom

thesupplement.^Using datafromtheRetirementHistorySurvey andtheNational LongitudinalSurveyofOldermen,

Bound

(1989) compares objective measures of health status with self-reported measures like the one used here. His

Although

theCPS

changed from paper

questionnaires to computer-assisted interviewing in1994,

and

themain

labor force status <piestionswere

also revised at that time, the content ofthe

income supplement was

not changed.Appendix

A

discussesan

analysis ofmatched

CPS

data

forMarch

1993and

1994,and

providesmore

informationon

theCPS

redesignand

itspossible consequences for our analysis.''

The

variables in theincome supplement

refer to the previous calendar year, so thesample

has data for

weeks worked and wages

in 1987-1996.The

disabihty status question in thesupplement

appearstorefer torespondents'status at thetimeofthesurvey(March

ofthe survey.

year), but actually serves as alead-inquestion prefacing additional

supplement

questionsabout

disability

income

the previous year.Except

for Table Iand

Figure I,which

present descriptivestatistics dated

by

survey year, the tablesand

figures label estimates according to the year ofobservation,

which

is the survey yearminus

one.CPS

supplement

respondents provide informationon

the sizeoftheemployer

theyworked

for longest in the past year.

Responses

to this question aregrouped

into three brackets;1-24 employees (small), 25-99 employees

(medium), and

100 ormore

employees

(large).The

analysis ofhiring

and

firingoutcomes

is basedon

changes inemployment

status in amatch

ofCPS

rotation groupsfrom

March

to April. Finally,we

useEEOC

data

on ADA-related

chargesbrought in each state since 1992 to see ifcharge activity is related to

employment.^

Descriptive statistics organized

by

survey year, age group,and

sex, arereported in TableI.The

tableshows no major change

in averageweeks worked

by

men

or in the proportion ofmen

currently employed, although there is a

modest

increase inweeks worked

by

women.

Table Iand

Figure 1show

an

increase in work-related disability rates formen

and women.

Disabilityrates for

men

aged 40-58 start increasingin the 1991 survey,and remain

high thereafter,though

with a slight decline in 1996

and

1997. Disability rates forwomen

aged 40-58 increase sharplystarting in 1994. For

men

aged 21-39, there is a small increase in self-reported disability ratesbetween

1990and

1994,which

is later reversed,and

in 1996 the disabihty rate for thisgroup

is lower than it

was

in 1990.These

patterns suggest theADA

may

have

had

an

effecton

theprobability that people describe themselves as disabled, especially for

women.

^ This raises theThe estimateswereport areweighted bj'

CPS

sampleweights. The weightswere updatedin 1994 toreflectthe 1990 Census.

We

use newly releasedupdated weightsforthe 1990-1993 surveys aswell. The 1988CPS

datacomefrom the so-called March "rewrite" file. This fileincludes firmsizeandother variables noton the original

1988 release, and reflects a revised imputation procedure (Bureau ofthe Census, 1991). The extract excludes

the hispanicoversamplefor each year.

A

few dozen households with duphcatehousehold identifiers inthe 1994survey werealso excluded because they could not be included inthe matchedsamples.

^Theanalysis variables are state/yearaggregatesfrom ourtabulations of

EEOC

microdata. Theseare similarto less recent statistics publishedin

EEOC

reports.^The fact that the disabled

may

be an elastic population has been noted by 01 (1991) and Kubik (1997).On

the other hand, Dwyerand Mitchell (1998) argue that disabilitystatus does not appear tobe endogenousinmodelsofretirementbehavior.

possibility ofcomposition effects, a point

we

return to in the discussion ofresults.V.

Results

A.

Employment

and

Wage

Effects

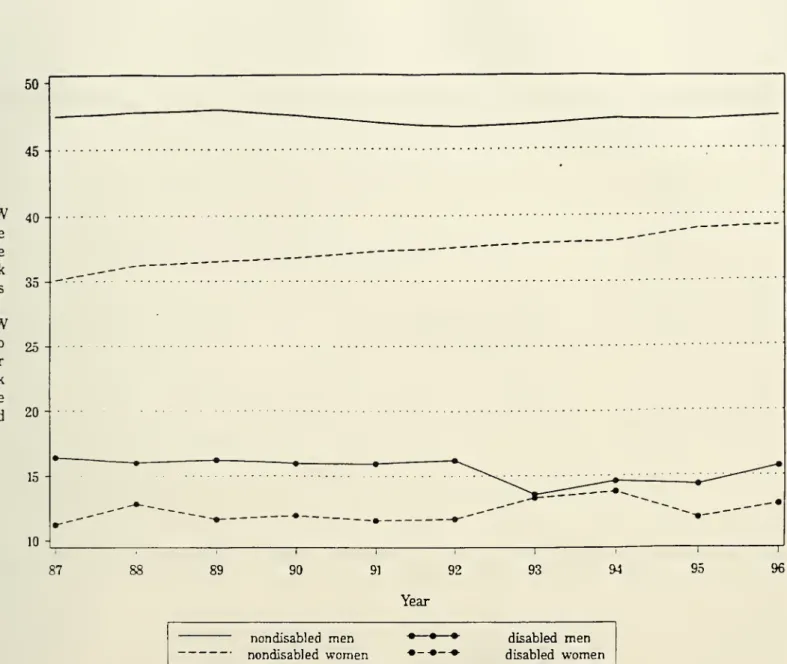

Figure 2 plots average

weeks worked by

sexand

disability status.While

men

aged

21-58work

on

average over 45weeks

a year, disabledmen

work

lessthan

20weeks on

average. Especiallynoteworthy

is the 2week

decline inweeks

worked by

disabledmen

between

1992and

1993, the first full year inwhich

theADA

was

in effect.There

isno

sharp decline inweeks worked by

disabled

women

aged 21-58.FigTues 3a

and 3b

plot averageweeks

worked

separatelyby

age group.Weeks

worked

by

disabledmen

aged 21-39dropped

sharplybetween

1992and

1993, while thoseby

disabledwomen

aged 21-39 started fallingin 1992.Weeks

worked by

men

aged 40-58 alsoshow

amarked

decline

between

1992and

1993. In contrast, therewas an

increase inweeks worked

by

disabledwomen

aged 40-58between

1992and

1993,which

iswhy

we

do

not see a decline for disabledwomen

when

thetwo

age groups forwomen

are pooled.Table II reports ordinary least squares

(OLS)

estimates of equation (6).These

estimatesarefrom regressions of

weeks

worked

and

log weeklywages

on

ageand

racedummies,

yearand

disability effects,

and

yearxdisability interactions for 1991-1996.The

interactionterms

are thecoefficients of interest.

Because

theADA

came

into effect in July 1992,we

think of 1993-96as post-treatment years. 1992 is possibly a transition year, while the effects for 1991

can

be

seen as '"pre-treatment" specification tests.

The

table also reports estimatesfrom

specificationsincluding a linear time trend interacted with disability status,

and

a single-effectmodel

thatincludes a trend interaction with disability status, 1991

and

1992 interactionswith

disabilitystatus,

and

a singlepost-ADA

dummy

for 1993-1996 interacted with disability status.The

models

with trends allow for the possibility that changes inoutcomes by

disability status canbe

explainedby

extrapolating different trends for the disabledand

nondisabled.The

results inTable II suggest that theADA

had

asubstantialand

statistically significantnegative effect

on

theemployment

of disabled peopleunder

40. For example,column

(1) ofPanel

A

shows

thatweeks worked by

disabledmen

aged 21-39were

stable until 1992, but fellby

1.8weeks

in 1993,and

declinedby an

additionalweek

in 1995.Column

(2)shows

thatcontrolling for disabihty-specific trends does not

change

these results. Results forwomen

aged

21-39 are similar (columns 4-6), but the decline starts in 1992.

The

sharpemployment

dechnesin 1992

and

1993 suggest that the costs of theADA

were not anticipatedby employers

beforethe law

became

effective. This is not too surprising since the first years ofADA

enforcementwere

characterizedby

some

confusion regarding exactlywhat

the act required (see, e.g., Veresand

Sims, 1995).Panel

B

reports estimates for the 40-58 age group.The

disabiHty-year interaction formen

is 1.8

weeks

in 1993, but this effect is halvedwhen

a linear trend is added.On

the otherhand,

thesingle-effect

model

reported incolumn

(3) generates a statistically significant,decline of2.1weeks

after controlling for disability-specific trends. Finally,column

(4)shows

a decline in therelative

employment

of disabledwomen

aged

40-58, but this is in 1991, before theADA

came

into effect. Moreover,

columns

(5)and

(6)show

that these effects disappearonce

we

controlfor disability-specific trends, and, in fact, the coefficients ofinterest

change

sign.So

there islittle evidence that the

ADA

had an

effecton

theemployment

of disabledwomen

in the 40-58age group.

Columns

(7)-(12) in PanelA

report estimates for the log weekly earnings ofmen

and

women

aged

21-39.There

isan

effecton

men

in 1994, but not in other years,and

the 1994effects disappears in

models

with a trend.There

isno

evidence of awage

effect forwomen

aged 21-39.

The

wage

estimates for oldermen,

reported in Panel B, are also sensitive to theinclusion of trends. Moreover, like the

employment

effects for olderwomen

inPanel

B, thedecline in

wages

for olderwomen

starts too soon.We

therefore interpret thewage

results assuggesting that the

ADA

had

littleeffecton

the relativewages

of disabled workers.The

rest ofthe paper focuses

on

further analyses ofemployment

effects only,and

the analysis is limited todemographic

groupswhere

the evidence for effects is strongest—

women

aged

21-39,and

men

in

both

age groups.Composition

BiasA

possible explanation for theemployment

results in Table 11 is acomposition

effect.Figure 1

shows an

increase in self-reported disability rates after 1991. IfTmemployed

peoplewere

disproportionatelymore

likely to identify themselves as disabled after theADA,

perhaps

because disability

became more

socially acceptable, the results in Table II could overestimatethe

disemployment

effects of theADA.

We

investigate the possibility of composition bias using amatched

sample from

the 1993and

1994 CPS's. In principle, thematched sample

providestwo

observations for half of the1993 respondents. (In practice the

match

rate is lower; seeAppendix

A

for details).The

matched

sample

is used here tocompare

individualswho

report a disability inboth

surveys tothose

who

do

not report a disability in either year. Since these surveys reportdata

on weeks

worked

in 1992and

1993, thematched

dataset provides ashort panel that straddlestheADA's

implementation

dateand

is imaffectedby

composition bias arisingfrom

changes in reportingbehavior.

Resultsusing the

matched

sample

are reported inAppendix

Table

Al.Column

(1) repeatsthe basic cross-sectional specification for 1993

and

1994data

only.Column

(2) reports resultsfor the

sample

ofindividuals forwhom

the mat.chwas

successful.Cohrmn

(3) reportsresults forthe

sample

of individuals reporting thesame

disabilitystatusinboth

years.The

cross-sectionalestimates in Table

Al

are similar to those in Table II.Comparing

cohimns

(1)and

(3), it isapparent that therestriction to the

same

disabihty status inboth

years has almostno

effecton

the results for

men

aged 40-58and

women

aged

21-39.This

isimportant

evidence against thepresence of composition effects since disabihty rates increased

more

for thesetwo

groupsthan

for the

younger

men.

For

men

aged 21-39, the results using asample where

disability status isunchanged

aresmaller than in the 93-94 cross-section.

The

disabihty-constantsample

shows

a 0.3 declinein

weeks

worked, ascompared

to a 1.2week

decline in the full cross-section, ora

3.1week

decline in the

matched

cross-section.Adding

controls for personal characteristicschanges

thisto a 1

week

decline,which

is closer to the 1.5week decHne

observed in the corresponding fullcross-section. Finally, excluding observations

where supplement and weeks worked data were

allocated

by

theCensus

Bureau

generates an estimate of -1.3 (reported incolumn

(7)). Overall,these estimates suggest that the results for

men

aged 21-39 are not generatedby composition

effects either. Infact, thecompositionstory is not plausibleforthis

demographic group anyway,

since disability rates for

men

aged 21-39 are actually lower at theend

ofthesample

periodthan

at tlie beginning,

and

the increasein disability ratescouldaccountfor atmost

halfofthedeclinein

weeks

worked.Changes

in theSSI and

DI

Programs

Another

factor affectingthe interpretation ofTableIIisan

increaseinthenumber

ofpeoplereceiving disability

payments from

the Disability Insurance (DI)and Supplemental

SecurityIncome

(SSI)programs

in the early 1990s (see, e.g., Stapleton, et al, 1994). Disabled workerswho

worked

longenough

are entitled to receiveDI

payments

when

notengaged

in substantialgainful activity. Disabled people without a

work

history can receive SSI,which

is ameans-tested federal benefit that is

supplemented by

some

states. Since SSIand

DI payments

createadverse labor supply effects, increased use of these

programs

may

account for thedechne

indisabled

employment

(a possibility suggestedby

Weidenbaum,

1994).We

address this issue inAppendix

B

usingCPS

dataon

social securityprogram

use.The

results ofthis analysissuggestthat the results in Table II are not explained

by

trends in SSIand

DI

receipt (see TableBl

forthe estimates).

Magnitudes

The

estimates in Table II canbe

compared

to estimates of the effect of theADA

on

the costs of

employing

disabled workers. Unfortunately, there areno good

estimates of thesecosts, so our calculations are really just educated guesses.

The

averageEEOC

charge ratewas about

12 per 1000 disabled employees a year. In cases resolvedby

theEEOC,

about

14percent ofall

ADA

charges, employersmade

averagepayments

ofover $15,000 per case. In theremaining cases, either the charge

was

dropped, is pending, or therewas

a suit.We

do

notknow

what

fractionofADA

chargesend

up

in court.However, between

1995-97 therewere

over56,000

employment

discrimination cases broughtin federal court (Administrative Offices ofU.S.Courts, 1997).

The

totalnumber

ofemployment

discrimination charges filedwith

theEEOC

during this period

was

245,000,which

implies that 23 percent of all chargeswent

to court.We

apply this fraction toADA

charges,and

use the cost estimate of$210,000 per case offeredby

Condon

and

Zolna (1997).To

be on

the conservative side,we

alsoassume

that ifan

ADA

charge does not go to court or get settled

by

theEEOC,

there areno

other costs.The

estimatedaverage cost of

an

ADA

charge is therefore equal to 0.23x

210,000+

0.14x

15,000=

50,400.This is 50,400 x 0.012

=

$605 a year per disabled employee, or $12 for eachweek

ofexposm-e

to the risk of a suit.

Assessingthe cost ofreasonable

accommodation

is even harder.The

Job

Accommodation

Network

(1997) reports amonetary

cost of$930 peraccommodation, which

we

take as the netcost.'

Our

estimates of separation rates in the next section suggest that the average durationof ajob lield by a disabled

employee

is 10 months,which

implies thataccommodation

leads toa $23 increase in weekly

employment

costs.The

average weekly earnings of the disabledwere

about $365 in 1991

and

1992. Since the total weekly cost increeisedue

to theADA

isabout

12+23=35

dollars, ourrough

estimate is that theADA

led to a 10 percent increase in the cost ofemploying

disabled workers.In the theoretical

model

in Section III, employers take the total cost of labor as givenand

are alwayson

their labordemand

curve. Since the results in Table IIshow

little evidenceof a

change

in disabled wages, the cost increase generatedby

theADA

fallson

employers.The

10 to15 percent decline inweeks

worked

is therefore consistent withdemand

elasticities ofabout

-1 to -1.5 for disabled workers. This is in the range of elasticity estimates reportedby

Hammermesh

(1986) for workers in differentdemographic

groups.^This number excludes any productivity increases due to accommodation and any losses fromjob changes

orsub-optimal reorganization of the work environment.

B.

The

Impact

of

the

ADA

on

Hiring

and

Separations

We

iisedmatched

CPS

rotation groupsfrom

March

to April to investigate the effect of theADA

on

hiringand

separation rates (seeAppendix

A

for details relating to theMarch-to-April match).

An

individual iscoded

as having experienced a separation in year t ifhe

or sheis

employed

inMarch

of that yearand

not in April. Similarly,an

accession (hire) is recordedwhen

someone

who

was

notemployed

inMarch

isemployed

in April. Separations are definedforthose

working

inMarch

while accessions are defined for those notworking

inMarch.

Disabilitystatus always refers to

March.

These measures

of accessionand

separations are thesame

asthose used

by Poterba and

Summers

(1986),and

the resulting average accessionand

separationrates are close to those they report.®

The

estimates of effectson

separationsand

accessions are impreciseand

also potentiallyaffected

by

theCPS

redesign (since the underlying datacome

from

themain

CPS

surveyand

not thesupplement). Moreover, Poterba

and

Summers

(1986)show

that labor-markettransitiondata are plagued

by

considerablemeasurement

error.We

thereforehmit

the discTission in thissection to a briefgraphical analysis.

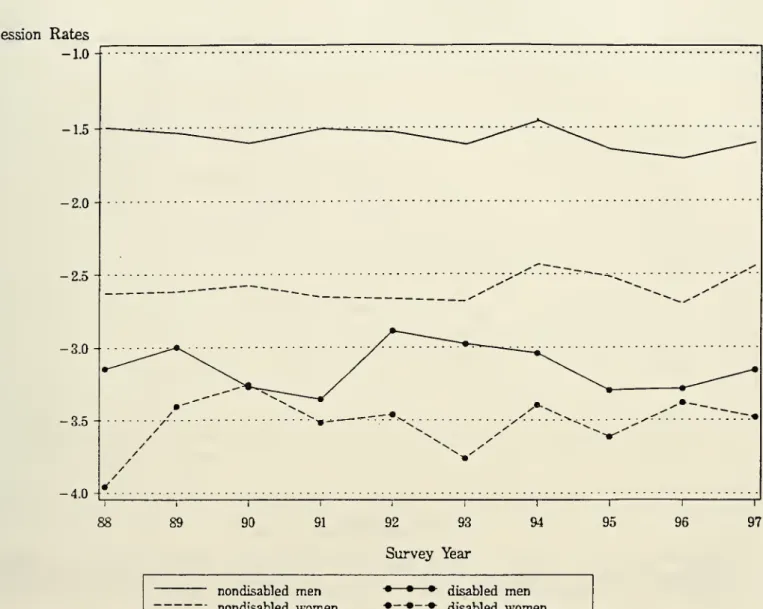

Figure 4a-d plot log accession

and

separation ratesby

disabihtystatus, sexand

age group.^Figure 4a

shows

a post-ADA

declineinseparation ratesfor disabledworkersaged

21-39,though

there is also a decline for the nondisabled.

On

the other hand. Figure4b shows

a post-AD

A

decline in the luring of disabled workers aged 21-39 that is not mirrored in the

data

for thenondisabled, especially for

women.

Figure 4c,which

plots separation rates for the 40-58 agegroup, again

shows no

evidence ofchanges uniqueto the disabled.On

the otherhand,

whilenotas clear as the

change

in disabled hiring for theyoimg

group. Figure4d shows

some

evidenceof a relati\-e decline in hiring for disabled

men

in the older group.The

apparent

reductions inliiring for

men

and younger

women

are not surprising sinceemployment

for thesegroups

fell. Itis important to note, however, that the lack ofa clear reduction in disabled separations weighs

against a pure "firing costs"

model

of theADA.

C.

Results

By

Firm

SizeNext,

we

look atemployment

patternsby

firm size. This is of interestbecause

firms withless than 15 employees are not covered

by

theADA,

and

those with 16-25employees were

^The average separation rate for 1988-1997 is 0.026 for

men

and 0.036 for women.The

average accessionrate is 0.18 for

men

and 0.08 for women. The disabled have higher separation rates and lower accession ratesthan the nondisabled.

^For instantanousaccessionandseparationrates, 77and(, the steady-stateemploymentrateisapproximately

e

=

;^-

We

plot log accession andseparation rates because^

=

(^^

-

^^)

.(e(l-

e)).initially

exempt.

The

ADA

might

alsohave

had

a larger effecton

employment

in small firmssince, as noted in Section III, small firms are probably less able to absorb

ADA-related

costs.Together, these considerations suggest

we

might

expect theADA

tohave

had

the largest effecton

employment

in firms that are sufficiently large tobe

coveredby

ADA

provisions but smallenough

tobe

vulnerable toan

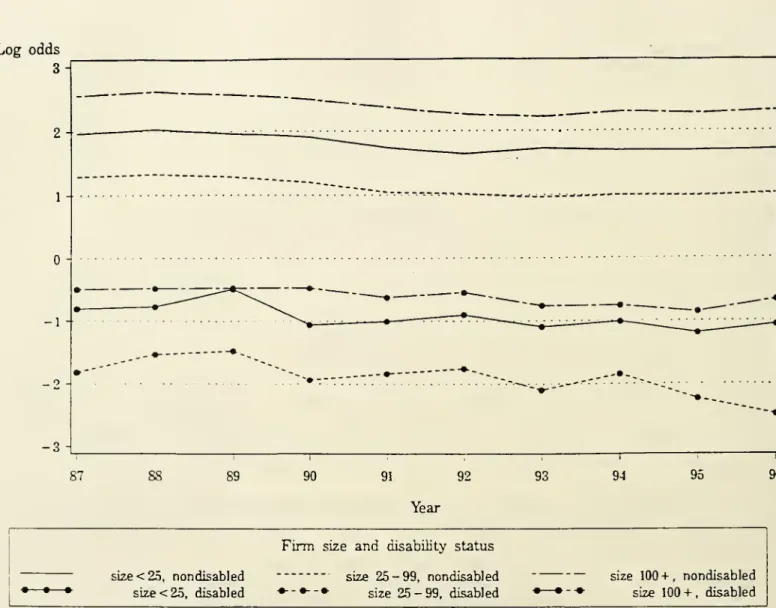

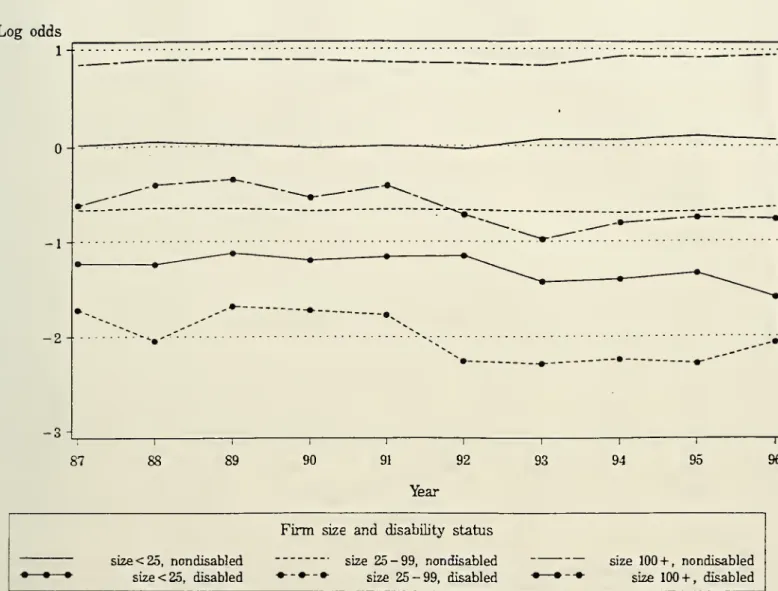

increase in costs.Figures 5a-c plot the log of the probabihty of

working

in a particular firm size categorydivided

by

the probability of not working.As

noted

earlier, the size category refers to theworker's longest job last year as recorded in the supplement.

The

size categories are 1-24(small), 25-99 (mediimi),

and

100 ormore

(large).The

figures give a visual representation ofthe coefficients in a multinomial logit

model where

thedependent

variable isemployment-by-size-category,

and

non-workers are the reference group.The

independent

variables are yeareffects.

The

log-odds in each figure werecomputed

separately for disabledand

non-disabledworkers.

The

log-oddsofworking

inamedium

sizefirmappear

tohave

fallensomewhat more

steeplythan log-oddsof

working

in asmall firm after 1992 fordisabled workers inall threedemographic

groups. For

women,

there is also a relativedecUne

in the probability ofworking

in a largefirm.Estimates of these differing trends

by

firm size are not veryprecise (e.g., t=1.4 for themediimi

vs. small contrast for

men

aged 21-39), but they are negativefor all threedemographic

groups.In contrast with this pattern, the log-odds of

employment

by

firm size are essentially parallelfor nondisabled workers, suggesting the

ADA

had no

effecton

the nondisabled.Of

course, evenif there were effects

on

the nondisabled, itseems

likely that theywould be

much

smallerthan

effects

on

the disabled,and

therefore harder to detect.D.

Cross-state Variation

inADA

Charge

Rates

The

last strategywe

use to estimate theimpact

of theADA

relates changes inemployment

tostate-level variation in

ADA

charge rates. Like the firm-size analysis, this strategy allows usto separately identify the

impact

of theADA

on

disabledand

nondisabledemployment.

Forthe purposes of this analysis, the

ADA

charge rate is defined as thenumber

ofADA-related

discrimination charges, in

a

state, perthousand

population disabled in the state in 1992 (thelatter figiu-e estimated using the 1992

CPS). Charge

rates are calculated separately for 1992,1993, 1994

and

1995, but 1992 population data are always used for the denominator.Charge

rates vary considerablyby

state.The

average cumulative rate for 1993-95was

13per 1000 disabled persons aged 21-58, varying

from

aminimum

of6/1000

to amaximum

of40/1000. Variation in charge rates is generated

by

idiosyncratic differences in state labor forcecomposition,localawarenessof

ADA

provisions, cross-state differences inemployers'compliance

with the

ADA,

and

whether

a state previouslyhad

an

FEP

statTite that covered disabledworkers.

Some

stateshad

weak

laws, while othershad

laws that set criminal as well as civilpenalties in cases

where

discrimination is proved (AdvisoryCommission

on

IntergovernmentalRelations, 1989).

The

estimating equation for this strategy is:96

Vidst

=

x'iP+

4>ds+

5dt+

Yl

adAfhrTs^T-l)+

Vidst, (7)r=93

where

ijidst isweeks

worked by

individual i with disabihty statusd hving

in state s in yeart,

and

X, is a vector of individual characteristics (ageand

racedummies).

The

regressors ofinterest are interactions

between

yeardummies

(e.g., /i.ga)and

the charge rate per disabledperson in the previous year in the individual's state ofresidence (e.g., rs,92).

Equation

(7) alsoincludes separate state effects for each disability group, 0ds,

and

yearx

disability effects,8dt-The

parameters of interest, 0^,93, 0^,94, 0^,95and

0:^,96, are the coefficientson

the state/yearchargerate interactions for each disability group.

These

effectsareidentifiedbecause

we

do

nothave a full set of statexyearxdisability interactions in the models.

The

yearx

disability effectsnow

play the role of control variables.We

also report estimatesfrom

amodel

thatadds

lineartrends for each statexdisability group to equation (7).

The

results in Table IIIshow

that in 1993-94,weeks worked by

the disabledmen

in stateswith a large

number

ofADA

charges declined relative to other states.Some

of the estimatesfor

women

aged 21-39and

men

aged 40-58 are negativeand

significant in other years as well.The

effects in 1993 are implausibly large, probably because the charge rate in 1992was

verylow, but estimates for other years are ofa plausible magnitude. For example, hah-ing the

mean

annual charge rateof4/1000 is predicted to reduce

employment

by

2.6weeks based

on

the 1994estimate for

men

aged 21-39.In contrast withthe estimates for thedisabled, there is

no

consistent evidenceofa negativeimpact

ofADA

chargeson

the non-disabled.The

only significant negative estimates for thenondisabled appear in

models

that control for linear trends. For themost

part, these estimatesare considerably smaller than the corresponding estimates for the disabled.

As

afinal strategy,we

experimented withIV

estimation of (7) treating diTTs,T-\ asendoge-nous.

The

instnmientwas

adimamy

forwhether

a state previouslyhad

an

FEP

law restrictingdiscrimination against the disabled, interacted with disabihty status

and

post-ADA

yeardum-mies.

The

presence of a preexistingFEP

law is negatively correlated withADA

charge rates,probably because the

ADA

was

less ofan

innovation in states with theirown

laws restrictingdiscrimination against the disabled. For example, the states with preexisting

FEP

lawshad

15 percent lower

ADA

charge rates.The

resultingIV

estimates are imprecisebut

they alsosuggest that the

ADA

had

largerdisemployment

effectson

the disabled in states withmore

ADA-related

charges.VI.

Conclusion

Some

social critics see theADA

as part ofa process eroding the traditional employment-at-willdoctrine

and

making

the U.S. labormarket

more

like labormarkets

in Europe. In contrast,ADA

proponents see theADA

asmaking

the labormarket

more

inclusive,without

appreciablyincreasing

employer

costs or reducingemployment.

Economic

theory is useful for evaluatingthese alternative views

and

suggests avenues for inquiry, but does notmake

imambiguous

predictions.

In 1993, the first full year in

which

theADA

was

in effect, therewere

marked

drops inthe

employment

of disabledmen

aged 21-58and

disabledwomen

aged

21-39. Extrapolatingemployment

trends, composition effects,and

changes inDI

and

SSI participation ratesdo

notseem

to account for this decline, leaving theADA

as a likely cause. This interpretation is alsosupported

by

evidence thatemployment

of disabledmen

fellmore

sharply in stateswith

more

ADA-related

charge activityand by

relative declines in disabledemployment

inmedium

size firms.Since the

ADA

provides aform

ofemployment

protection, it can lead to lower separationand

accession rates for the disabled.There

is littleevidenceofan

effect oftheADA

on

disabledseparations, however. This

and

the fact that costs of reasonableaccommodation

areprobably

larger than the costs of litigation for wrongful termination suggests that

accommodation

costsha\'e

been

more

important for employers than lawsuits.The

absenceofan

offsetting decline inwages

suggests the equalpay

provision has also played arole in theADA's

employment

effects.Finally,

we

foundno

evidence of effectson

nondisabled workers.Contrary

to the concerns ofits fiercest

opponents

(e.g. Olson, 1997), itseems

likely that theADA

predominantly

affectedthe costs of

employing

the disabled,and

has not led to a fear-of-litigation climate thatreduced

the overall level of