43

Hidden Art:

Artistic References in Mattotti’s Docteur

Jekyll & Mister Hyde

Barbara Uhlig

Abstract

Mattotti’s adaptation of the classic Jeykll and Hyde narrative is a unique and stylistically rich interpretation. Shifting the setting from Victorian London to Weimar Berlin, his graphic adaptation is closely linked to the artistic expression of the time. Mattotti understands art as a reference system that can be activated and used to suggest new interpretations of an old story. He weaves quotes and references to a multitude of visual sources into his adaptation, from Expressionist film to paintings by Otto Dix and George Grosz. These artis-tic references open up the adapted text and enable the reader to view it in a new light. At the same time, his disregard for the distinction between highbrow and lowbrow consciously dissolves the boundaries between art and comics and further strengthens the medium’s position as ninth art. To analyze Mattotti’s approach to art, the categories of “filtered memory” and “direct reference” will be introduced and expanded upon.

Keywords

44

“Mattottica pinottica,” Mattoptics—these were the words art critic Enrico Ghezzi used to describe the comics of Lorenzo Mattotti, alluding to both the overwhelming pictorial quality of his work as well as his many references to classical art (Ghezzi). Indeed, Mattotti’s comics have always been closely linked to clas-sical art, and to painting in particular. The avant-garde movements of the early 20th century influenced him greatly, as did early expressionist films, which can be seen in his way of using strong, non-representational colors, stark contrasts in hue and lightning, as well as pictorial flatness and fragmentation. Mattotti and Jerry Kramsky’s 2002 album-length, full-color adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s novella The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is no exception. Not only does the work explicitly reference expressionist art, its set-ting is transposed from Victorian London to Weimar Berlin. This means that Mattotti and Kramsky’s Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde not only presents a shift from one medium to the other—from novella to comic—but also from high art to popular art. Further complicating these shifts are the multiple translations and retransla-tions of Stevenson’s novella: while the work was originally written in English, Mattotti and Kramsky used the Italian translation by Carlo Fruttero and Franco Lucentini as their source, even though the comic was origi-nally published in French.1 For these reasons, in this article I will use the Casterman’s 2014 re-publication of Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde. It is important to note that the French edition does not name which translation of Stevenson it is based on, and in comparing the work with other French translations, I found they did not match. It can therefore be assumed that Marc Voline retranslated into French the quotations that Mattotti and Kramsky took from the Italian edition of Stevenson’s text. This, of course, adds yet another layer of interpre-tation to the complex relationship between Stevenson’s original text, the English to Italian translation, and the graphic version of the text.

According to Hutcheon, the term “adaptation” embodies “three distinct but interrelated perspectives,” namely the idea of repetition without replication, (re-)interpretation, and intertextuality (7). The first aspect refers to its transposition that may change the core elements of the source while still saying close to its core ideas, which may be achieved, for example by transposing it into a new medium or setting. This plays a vital role in the interpretation of the adaptation by Mattotti and Kramsky, as the use of the comics medium and the setting transposition present significant points of accord and divergence from the original text. The second interrelated aspect, (re-)interpretation, looks at adaptation as “a process of appropriation, of taking possession of another’s story, and filtering it [...] through one’s own sensibility, interests, and talents” (18). Here again, the adapters’ own intentions come into play in the change of medium and setting. Finally, intertextuality deals with the way both the adapters and the readers perceive the work through their own memory of other works that resonate with it. This aspect is particularly important for Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde as Mattotti not only quotes directly from the (Italian translation of the) original work, but also weaves quotes and references to visual sources into his adaptation.

Visual References in Mattotti’s Work

There are two different ways in which Mattotti approaches art and integrates it into his work. On the one hand, his references to art can be highly distilled and palpable only in traces as a distant memory—they are seamlessly integrated into his unique, instantly recognizable style. This is what Hutcheon would refer to as

45

“background noise,” the intervisual parallels to modern art paintings and illustrations “that are due to similar artistic [...] conventions, rather than specific works” (21). Indeed, Mattotti skillfully takes an art movement’s central characteristics and uses them to create his own works that pay tribute to the original movement. In Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde, this can be seen in his use of expressionism, that is, in the flattened pictorial space, the organic brushwork, and the vivid, unconventional colors that appear independent of their real-world objects. For example, the color palette in the beginning of the comic is unmistakably similar to that chosen by the Munich art group “Der blaue Reiter” (1911-1914), whose members believed that color was at its strongest when it was applied spontaneously to express an intense emotional sensation. This is significant for Mattotti who broke new ground in the way color is used in comics and narrated his story primarily on an emotional level.

On the other hand, art in Mattotti’s comics can be used as a direct citation, its origin quite clear and identifiable, which adds an additional layer of meaning as a sophisticated commentary on the story. In his 1989 comic Murmure, for example, he references Umberto Boccioni and Ernst Barlach, but also alludes to comics like The Yellow Kid and The Katzenjammer Kids (Uhlig 97-101). His and Jerry Kramsky’s adaptation of Ste-venson’s novella The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is the one comic in Mattotti’s oeuvre that uses the most direct artistic references, most notably Otto Dix’s Seven Deadly Sins (1933), to which he devotes an entire page.2 In both his approaches to engaging with art—either as filtered memories or as more direct refer-ences—it is important to note that the allusion invariably adds an additional layer of meaning. Never reduced to a purely decorative, non-narrative element, the art movement he chooses as “background noise” is always closely tied to the comic’s narrative and is an integral part of the artist’s communion with his audience.3 Understanding his specific references thus opens up the interpretation of his comics—at least to an informed reader, who, at least to some extent, is able to identify the references. In short, by absorbing and transforming his artistic references, Mattotti has created a unique personal style that always communicates on an emotional level and across several media. Whether in comics, illustration, painting, animation, or sculpture, his creations have a distinctive air about them, making his diverse oeuvre consistent and instantly recognizable (Brandigi 111). Because Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde makes use of both reference systems that Mattotti adopted, it is therefore a particularly suitable example for showcasing the importance of artistic references in his comic work.

Structure

The textual element in Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde stays close to the Italian translation of Steven-son’s text in its nearly word-for-word incorporation of carefully selected passages that are particularly central to the narrative or emotionally-charged. However, the original plot structure is not followed—it has been compressed and paired down. Mattotti and Kramsky nevertheless are able to preserve Stevenson’s intended atmosphere of sublime terror and looming disaster, and convey a dense atmosphere. Their restructuring of the

2 Due to copyright restrictions, only images of the comic are included in this article. All paintings mentioned, however, can easily be found online.

3 In Caboto, a comic about an early explorer of the American continent at the turn of the 16th century, Mattotti absorbs the painting style of the Spanish golden age, and adds a yellow tint and crackled surface to his illustrations reminiscent of old oil paintings. In Fires, a story about the confrontation between nature and civilization, the paintings of the Fauves are clearly visible in his flat brush-work, use of colors, and handling of perspective.

46

plot and centering the narration on the novella’s chapter “Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case,” which is framed by the chapters “Story of the Door” and “The Last Night,” follows a well-established pattern within the adaptation history of the novella. Sara Rizzo demonstrates that most adaptations now place great emphasis on the transformation of Jekyll into Hyde and show it early on in the plot instead of at the very end, as Steven-son’s text did. This device, much favored for its “spectacular potentiality” (Rizzo 256), was first used as early as 1887 in a stage adaptation featuring Richard Mansfield as Jekyll/Hyde. Nowadays, as the story has become part of cultural knowledge and the revelation hardly comes as a surprise, it may seem a good choice to change the structure. Most adaptations thus anticipate the transformation and place less emphasis on the revelation of Hyde’s identity than on Jekyll’s identity crisis. This holds true for Mattotti and Kramsky’s adaptation. Due to the standard bande dessinée format of 64 pages, they needed to shorten and synthesize certain scenes. For example, while both the novella and the comic start with Hyde running over a young child, in the novella Hyde is shown as being completely indifferent to the girl, but in the comic he purposely attacks her. In this way, the comic shows Hyde’s propensity to excessive violence and his capacity for murder from page one, rather than initially only hinting at this theme.

A graphic adaptation’s most challenging aspect is finding a visual equivalent to the adapted text. Often, text has been considered primary and illustrations inadequate (Torgovnick 93), what Diane Penrod calls the “hegemony of word over image” (80). Illustrations are sometimes accused of “severely limit[ing] the range of the reader’s visual imagination” (ibid.), and thus are critically viewed for “guid[ing] the reader’s imagination through one potential reading of the text,” and having “the potential to change reader perception dramatically” (Doerksen 499). As James H. Brown argues, images add finality to a story by offering a static image, where-as the text may be open to interpretation (186). Therefore, providing a visual interpretation is particularly difficult if the adapted text is deliberately ambiguous, which is the case of Stevenson’s novella. In his work, Stevenson carefully avoids describing Hyde’s appearance, choosing instead to give an account of the reaction Hyde elicits from everyone he meets, which is one of loathing and a desire to kill him. In fact, Stevenson only mentions that Hyde is smaller than Jekyll and that his hands are “lean, corded, knuckly, of a dusky pallor and thickly shaded with a swart growth of hair.”4 Due to this, focus on Hyde’s hands has become a staple in visual adaptations of the novella, as for example in Mammalian’s cinematic adaptation Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde from 1931 (Jones 102). Mattotti chose to deviate from this. While he does show Hyde’s fingers turning claw-like in the first transformation scene, it is only one of ten panels that he dedicates to Jekyll’s metamorphosis. His focus is rather on the excruciating pain of the process, and its visual rendering is similar to scenes in his other works depicting painful—though mostly spiritual—transformations.5 Both the first and the last panel of this scene show a twisted, though decidedly human figure, not a “deformed” creature, as Stevenson comments on Hyde’s appearance. Also, in the adaptation, the people Hyde encounters do not react to Hyde until he acts out of control. The intentions of the adapters are here decidedly different from those of Stevenson: Hyde is not judged by his appearance, but by his actions. Mattotti does not turn Hyde into something non-human as the source text suggests, but rather allows Hyde’s misdeeds to define and eventually change him. For this reason, it is not surprising that Hyde’s hands are not hairy in the beginning—he starts to change only after his sexual excesses and murder of a war criminal. His hands are also a sign of Jekyll losing control over Hyde, as they

4 For this paper, the Gutenberg version of the text was used. Therefore, citations do not have a page number. The full text can be found here: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/43/43-h/43-h.htm

47

appear for the first time when Jekyll goes to sleep as himself and wakes up as Hyde. In the course of the comic, as Hyde becomes increasingly desperate, his hands become hairier and the overall style of the visuals deteri-orates. The flowing lines become jagged and less organic and the colors turn into muddy tertiaries (fig. 4). He does, however, avoid giving Hyde clear features by casting his face into shadow most of the time.

The Hollywood tradition in particular not only places emphasis on the transformation of Jekyll into Hyde but also allows Jekyll to find a rather peaceful end—in death he manages to regain control and trans-forms back to his old self (Rizzo 256). Mattotti, however, chose a different path. At the point when Jekyll ac-knowledges that he has lost control over Hyde and decides to commit suicide, he has visually transformed into an altogether different creature, no longer human but not like Hyde either. He is reduced to a white, writhing shape reminiscent of Francis Bacon’s painting Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), a body in pain whose life force is derived out of the oppressiveness and density of the surrounding black space. What the doctor finds when breaking down the door, we do not know—all we see are two men hunched over in horror looking at a black shape on the floor. The text only mentions a “painfully contorted body,” consciously leaving out the passage that states it is Hyde’s. Mattotti and Kramsky’s choice to assume the polarity of Jekyll and Hyde as known to the reader finds its echo in the visuals. Intertextuality is not limited to motifs from other adaptations, but also weaves in cinematic techniques popular in the 1920s, which also work to tie the adapta-tion to its new setting. Mattotti’s pictorial language makes heavy use of tilted angles, which add to the feeling of unease and madness. It is no coincidence that the first pages of the comic remind one of the cinematographic techniques of the Dutch angle, sometimes called the German angle, where the camera is not level with the horizon. This technique, first used in early German expressionist films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), which intended to essay the social deterioration of Weimar Germany, allows the comic an unusual perspective that shows both the city of Berlin and the inner world of Jekyll to be off-balance and about to collapse.

Setting

As aforementioned, the most dramatic deviation from Stevenson’s story is the comic’s setting. Instead of Victorian London, this story takes place in Berlin in the 1920s. This is obvious in both the colors and the visual references to paintings and drawings by artists from Expressionism and New Objectivity, which depict the dark side of the metropolis in the so-called golden twenties. In both narratives, the city itself plays an im-portant role. In Stevenson’s tale, Victorian London is divided into two strata. One belongs to the respectable high society and is characterized by its well-lit streets and handsome houses. Clearly, this is the world of Dr. Jekyll, an honorable gentleman. Hyde, in contrast, lives in Soho, which, at the time, was a shabby, ugly part of the city that Stevenson describes as sinister and disdained. Here, Hyde can live out his dark desires, the very impulses that Jekyll seeks to eliminate from his social as well as private persona. The two sides of London, however, are as intricately and inseparably linked as Jekyll and Hyde themselves, and so their houses are connected by a secret passage. Additionally, London, as the capital of Victorian society, was marked by rapid technological and social changes that brought with them new fears. Urbanization resulted in the creation of slums, rising crime rates, and the spread of disease (Dierkes 47).

The situation in Berlin half a century later was similarly torn: on the one hand, the 1920s were Berlin’s cultural heydays after the devastations of the First World War. The city was brimming with energy—art and

48

theater flourished, cabarets were thriving, jazz swept the country, and people went wild. On the other hand, the war and reparations had badly affected the city: war invalids lined the streets, many went hungry, and prostitution prospered. As in Stevenson’s London, two worlds collided in Weimar Berlin, pitting chaos against hope, deprivation against decadence. Mattotti’s interpretation of Berlin is based on the paintings and drawings by George Grosz, Otto Dix, Hanns Kralik, and Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, which show a society close to madness, whose dance on the edge of a volcano is leading it directly into catastrophe. The graphic scenes of Hyde’s excessive violence can, in this context, be seen as an additional commentary on the story that is closely tied to its setting. Stevenson links Hyde’s violence to the stifling social conventions of his time that his protagonist tries to escape in his bid to pursue pleasure. In so doing, his novella becomes a reflection on the dual nature of the human being and the inhibiting threat of social ostracism. Mattotti and Kramsky’s setting in Weimar Germany speaks of the danger of poverty, hunger, and distress. In the comic’s colors and pacing, fascism rising as result of impoverishment and desperation can be felt. Mattotti achieves this by linking his adaptation to Expressionist art. His citations in the form of filtered memories are subtle, palpable more in color and composition than content. While a sophisticated reader may still be able to identify the source paintings and thus enjoy a deeper engagement with the comic’s palimpsestic structure, a vague recognition of the com-ic’s ties to Expressionist art are sufficient. Mattotti manages to activate a remembrance of similar depictions in the reader’s mind, shining a light on comparable documents the reader may have seen. This results in a dark and gloomy atmosphere that alerts the reader to the story’s prevailing tone and heightens the escalating violence of Hyde’s nefarious deeds.

References to Fine Art in the Comic Adaptation

On the very first page, the comic references Kralik’s painting From my Window (1930), a work sim-ilar to Mattotti’s creations in both subject and spatial distribution, from the design of the curved house and the distortion of shadows to the yellow tram that he incorporated into the third panel. The colors and the perspective, however, have been changed: the chromatic choices and changes are tied to the narrative, not to the original painting. Mattotti opts for a Dutch angle towards the first depiction of Hyde—a shadow roaming the night-dimmed streets—to show the setting as off-balance. In this first scene, we also find references to the geometrically constructed bodies of Oskar Schlemmer, who builds all his figures using geometric forms and intense shading to make them three-dimensional. Also, the figure of the girl strikingly reminds the viewer of Schlemmer’s costume design for his triadic ballet, a curious reference. The Bauhaus artist wanted to recreate the human figure by breaking it down into its parts, much like taking apart a machine, to rebuild a better, im-proved version of mankind (Behrisch). The same can be said of Jekyll, who tried to eliminate the dark side of his personality by splitting it off and discarding it.

As aforementioned, the comic also includes many references to George Grosz. On page 11, Jekyll discusses his ideas on splitting someone into two different entities with his fellow scientist, Dr. Lanyon. They meet at a bar. Their table stands in the background, separated from everyone and everything else. In the fore-ground, several couples are dancing. The warped perspective of the floor tiles does not match that of the walls. The clashing colors reinforce foreshortening and centering, thus increasing the prismatic effect of the pictorial space. Grosz’s influence can be seen in the fragmentation of space, line, and perspective that is typical of his

49

work, as well as the specific rendering of the human face that is close to caricature. This is even more obvious in the middle panel on page 23, in which Hyde triumphantly raises his cane into the night sky. This is a clear reference to Grosz’s painting Widmung an Oskar Panizza (Dedicated to Oskar Panizza, 1917/1918). In bright red, it depicts an apocalyptic vision of German society on the brink of chaos: a hysteric and dehumanized mass fills the streets of the city, a drunken skeleton sits on a coffin. The parade is led by three figures representing Alcohol, Syphilis, and Pest—caricatures of the social structure in Weimar Germany. The only clear figure is a bloated priest, fervently brandishing a bright white crucifix that offers no consolation. In the comic’s panel, the reference to Grosz is clearly visible in the tilting facades to both sides of Hyde, in the reflections in the windows, in the posture of Hyde that exactly mirrors that of the priest—though he is raising his cane instead of a crucifix—, and even in the violent colors (fig. 1). For Grosz, the painting criticized the social disintegra-tion that is reflected in sexual excess, lust for power, and exploitadisintegra-tion of the working class (Pascu 89). Citing this image in Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde is far more than an homage, however. It links the narrative to the social grievances of the 1920s, since both protest “against a humanity that [has] gone insane” (Wolf 42). While Grosz depicted the threat to democracy, Mattotti additionally shows the threat to the identity of man, a central theme in the adapted text, therefore linking both ideas in one panel. In the whole scene, in which Hyde fully experiences his new freedom for the first time, red and a tainted green are the dominant colors. These reinforce the loss of control reflected in the protagonist’s glowing eyes. Contorting angles and towering buildings about to collapse convey the instability of what represents normalcy.

The most frequently referenced artist in the comic, however, is Otto Dix, and particularly his rep-resentation of prostitutes in Weimar Germany. This is no surprise considering that the city and its inhabitants were his main subject. One of Dix’s most famous paintings, a triptych called Grande Ville (1927/1928) is referenced three times in the comic. Its first rendering in the comic is very close to its source, while the other two depictions progress in time with the narrative development and show what happens to the characters in the triptych at later stages in their lives. The format of the triptych has always been used to display great shock and overwhelming devastation (Müller). A triptych normally defies the established reading direction from left to right—the gaze jumps back and forth between the three images to settle on the middle image. In the case of Grande Ville, the middle panel forms a harsh contrast in showing the rich upper class that is blind to the dire

Fig. 1: Hyde raises his cane into the night sky, duplicating the pose of the priest in the painting Dedicated to Oskar Panizza by George Grosz; Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde, Mattotti/Kramsky, © Casterman S.A.

50

need of the lower classes depicted in the smaller side panels. The large painting in the middle depicts a fancy jazz club. A band is playing, couples in exquisite clothing are dancing, large feather fans in hand, with the polished parquet floor reflecting their every movement. The two side panels show the urban space. The archi-tectural backdrop suggests that the left panel represents a poor quarter, the right panel a bourgeois setting. The men in both side panels are badly mutilated war veterans. Crippled, deformed, unable to walk, they are out-casts. The prostitutes, reduced to their bodies, form a harsh contrast to them. Waiting for solvent clients, they ignore the veterans. Both groups are survivors of the First World War, unable to return to a normal life within society. Society itself—represented as the upper class in the middle panel—is caught in a state of denial.

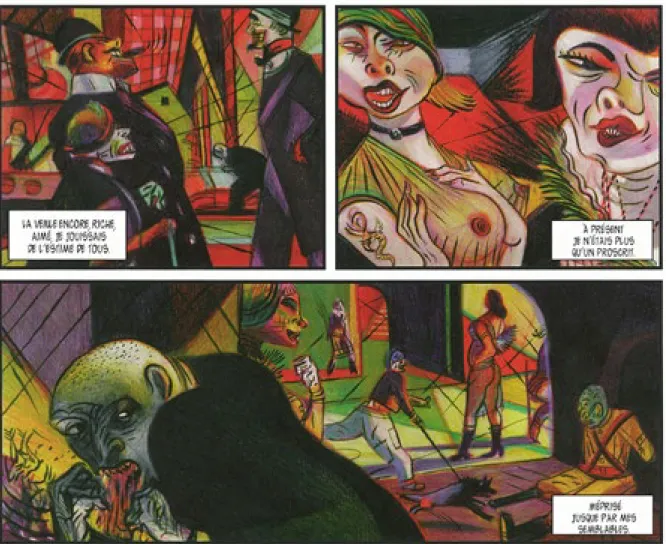

The structure of the triptych has not been preserved in the comic but has found an expression that keeps up its structural opposition. The first time Mattotti alludes to this painting is after Jekyll’s meeting with Dr. Lanyon on page 15. Outside the bar, several prostitutes are waiting for wealthy clients (fig. 2). What used to be the middle panel is now a panel that fills the width of the page (the bar scene). The former side panels have been integrated into a single panel on the following page so that it is now the reverse of the former middle panel. Though it is technically one panel, it is visually split into three parts: the outer edges show prostitutes in rather fancy clothes while Jekyll, walking past with his gaze lowered to the ground, represents the oblivious upper class of the triptych. Mattotti also found a way to replicate the back and forth movement of the triptych by returning to the side panels at later stages in the comic, thus forcing the reader to flip back and forth be-tween the pages to compare the images.

Mattotti’s prostitutes on page 16 reference the left panel of the triptych, both in attitude and appear-ance: he mimics the prostitutes’ posture—hand on hip, face in semi-profile—, transparent clothing, and fox-head shawl draped across naked shoulders. It makes sense to not reference both source panels, as the original structure implies a change in setting when read from left to right, since it is rather unlikely that Jekyll would pass through one of the poor quarters on his way home. The caption in the previous panel is in sharp contrast to its pictorial content. While we see the close up of a prostitute, her gaze lascivious, tongue salaciously hanging out, reminding the viewer more of a dog than a human being, the caption paraphrases Stevenson: “The just could walk steadfast on his upward path, as it is his nature, no longer exposed to disgrace and penitence by the

Fig. 2: The prostitutes in the background are modeled after Otto Dix’s Grande Ville; Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde, Mattotti and Kramsky, © Casterman S.A.

51

hands of this extraneous evil” (16, my translation).6 The image exposes the hypocrisy behind these words: the so-called just deems himself a better person, but secretly wishes to be able to live out his dark desires without being judged by his fellow men. This reflects Dix’s intention in Grande Ville, which can be interpreted as condemnation of society’s exploitation and alienation of the poor.

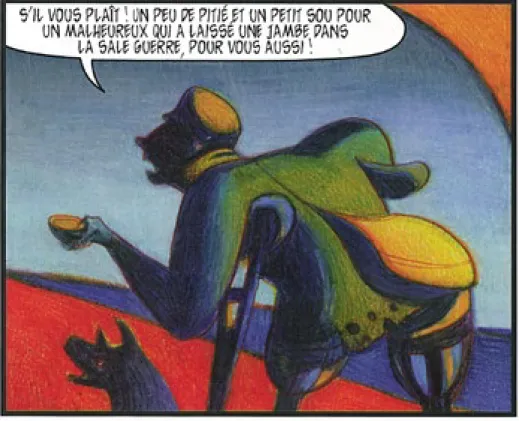

Mattotti returns to the triptych as an inspiration for a scene on pages 30-32, in which Hyde attacks and kills a war cripple and his dog (fig. 3). Here, however, he refers to the right panel of the triptych as it is Hyde—not Jekyll—who roams the streets. The cripple and the dog bear a striking resemblance to one of the veterans in the left panel of Grande Ville, again objectifying him and exposing him to the whims of those in power. At the same time, it continues the narrative of the original painting. While Dix showed the war cripples being at the mercy of the rich to support them in charity, Mattotti shows that their lives depend quite literally on the rich—the veteran’s death does not lead to legal consequences for Hyde but is a heavy burden on Jeky-ll’s conscious and the reason for his first involuntary transformation. Structurally, the panel of the war cripple is again positioned in the middle of a left page, making it a reverse of the tryptich on page 15 and therefore linking it to the panel of the prostitutes on page 16.7.

Near the end of the narrative, on page 56, Mattotti again returns to Dix’s left panel and to his own inter-pretations of it on page 16 (fig. 4). Now, it refers to the prostitutes in the poor neighborhood of Dix’s painting

6 The original English text says: “The just could walk steadfastly and securely on his upward path, doing the good things in which he found his pleasure, and no longer exposed to disgrace and penitence by the hands of this extraneous evil.”

7 The scene also offers multiple references to the Symbolist painters Léon Spilliaert, in the depiction of the bridge (in particular his painting La Poursuite, 1910), and Edvard Munch, in the death mask in the last panel, mouth and eyes wide open in a scream of horror, the skin a garish yellow and lips turned blue. Both Spilliaert and Munch perfected the translation of disenfranchisement, loneliness, and desperation into paint. Particularly Munch’s painting The Scream (1893–1910) has become a synonym for anguish and suffering, a pervasive theme in the comic.

Fig. 3: The crippled war veteran is again taken from Otto Dix’s Grande Ville; Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde, Mattotti/Kramsky, © Casterman S.A.

52

as well as to the cripple with his dog. Comparing the scene on page 56 to the ones on pages 16 and 30, the characters’ decline into misery and madness becomes palpable. The features of the prostitutes are distorted, exaggerated into caricatures, and Hyde’s grey figure appears haunted and hardly bears any resemblance to his former self. We may be again in the street, surrounded by prostitutes, seeing a cripple with a leg prosthesis sitting in a corner, a dog barking at him. This time, however, Jekyll is an outcast himself. This is particularly shown in the proportions of those depicted. The prostitutes are no longer pushed against the edges of the pan-el’s frame, nor is the war cripple subjected to Jekyll’s arrogance or Hyde’s violence, but have become peers. Desperation permeates the scene, the atmosphere tinted bright green, appearing to be toxic.

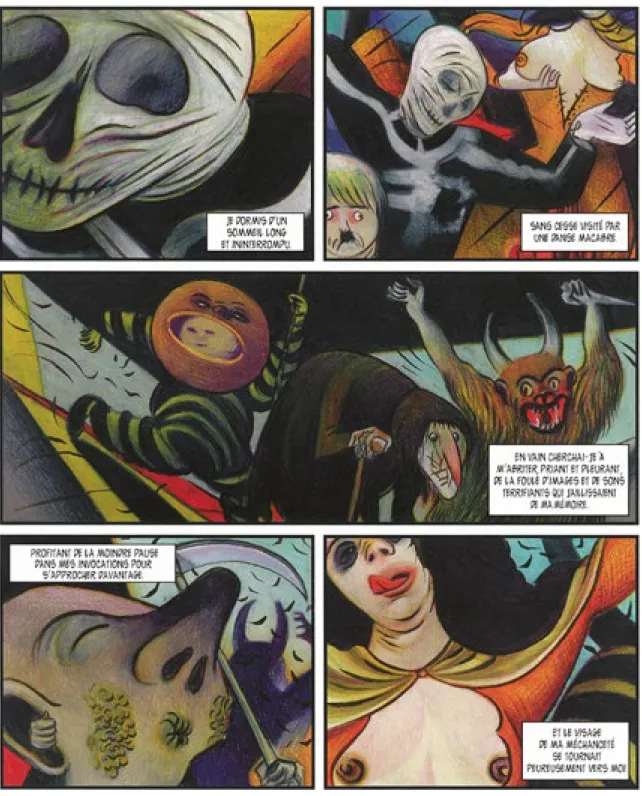

One spread later, on page 58, Mattotti devotes a whole page to a particularly unfiltered reference to Dix’s painting The Seven Deadly Sins (1933). The depiction in the comic is practically unaltered (fig. 5). The sins are introduced by an old witch, greed, who carries a yellow dwarf on her back, who represents envy. A dancing skeleton symbolizes sloth, a nearly naked woman to his left is lust, and a red devil with horns is wrath. Gluttony, finally, is a fat boy with a stockpot on his head, sausages wrapped around his body, and a pretzel in his hand. Pride holds his blackened nose high into the sky, his mouth shaped like an anus. The original painting contains thinly veiled allusions to the rising Nazi regime. The skeleton holds his extremities as well as his scythe in a way reminiscent of the form of the swastika. The dwarf is Hitler, although he obtained his characteristic mustache after 1945. Considering that Mattotti referenced this painting in such a direct way, his

Fig. 4: Mattotti returns to the prostitutes in Grande Ville, but the drawing style deteriorates, mirroring Jekyll’s declining mental state; Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde, Mattotti/Kramsky, © Casterman S.A.

53

Jekyll and Hyde adaptation may well be interpreted in a fascist context. Although the story and the adaptation speak of the universal danger of arrogance, self-righteousness, and hubris, this artistic reference to Dix opens up its interpretation to include a political message on the dangers of poverty, social alienation, and fear of the “other.” In the comic, Dix’s seven sins perform a grotesque dance while Jekyll is dreaming of all the horren-dous crimes he committed as Hyde. The personifications of his sins retreat into the background and nearly disappear when he thinks back to the happy days of his childhood. This suggests that his fears and desires had been present since his childhood days but only took shape when he acted upon them, which only reinforces the interpretation that a person is not defined by his nature but by his actions.

Fig. 5: The parade, representing Jekyll’s fears and dark desires, is an obvious reference to Otto Dix’s The Seven Deadly Sins; Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde, Mattotti/Kramsky, © Casterman S.A.

54

Color Code

As the examples above demonstrate, Mattotti uses the style of paintings and their themes as an inspi-ration for his own drawings, but he treats colors more freely. The direct references in this adaptation are taken from New Objectivity, whose members mostly restricted themselves to a muddy red-brown, often using a washed-out color palette that was meant to highlight the decay and moral decline of the subjects they depicted. Mattotti instead opted for a different color palette that would highlight and narrate both the plot’s structure as well as Jekyll’s irrevocable transformation. He thus decided to base his adaptation on the palette of early expressionists like Franz Marc and August Macke who preferred radiant primary colors. Paintings such as Marc’s Cows Yellow-Red-Green (1912) or Little Blue Horse (1912) are chromatically very similar to the first pages of Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde. Mattotti split the landscape into geometric forms and colored them in vibrant hues of blue, red, and yellow. The expressionists loved these colors because their stark contrast to each other made them appear more vibrant. Additionally, they symbolized positive spiritual transformation and living in harmony with nature. Both ideas can be found in Jekyll’s motive to split his personality into two different entities, one fully evil and one fully good. What he had hoped for was a change for the better; what he got was a change for the worse. The same can be said about the expressionists who fully embraced the First Word War due to a distorted perception that it would bring out the best in mankind and allow for a fresh start. Those who survived abandoned expressionism as a failed utopia.

As Jekyll’s experiment progresses and he realizes that his/Hyde’s “undignified pleasures,” as Steven-son put it, became increasingly more violent, the colors gradually change. The hopeful, hyper-symbolic blue of the expressionists all but disappears to be replaced with a toxic green, a harsh orange, and a reddish-purple. In other words, the pure primaries drift into secondary colors, highlighting the troublesome personality of Hyde gaining ground. Along the same line, these colors also take up more and more space on the page. While there were only traces of them in the beginning, they are soon equally distributed in the panels. As soon as Jekyll can no longer control his transformation into Hyde, and needs more and more of his magic potion to allow him to transform back into his socially acceptable self, Mattotti increasingly mixes his secondary colors with black, making them significantly darker, foreshadowing the looming disaster. Only a fierce hot red re-turns whenever Hyde’s temper takes over and he falls into a killing rage. But even this is finally swallowed by an all-consuming black, as Jekyll realizes that he cannot escape his crimes committed as Hyde, and that death is unavoidable. Once he accepts this, Mattotti allows for a hopeful, light blue to return as the last thing that Jekyll sees: a soft blue sky.

In this sense, color is used as rhythm. As pointed out earlier, Mattotti uses the primaries to make the panels appear more vivid, in addition to conveying the narrative tension. These clashing colors accelerate the pacing of the comic. When Mattotti visualizes the clash of Hyde and the girl in the comic’s very beginning, it is highlighted in the contrasting colors as well as in the geometrical shapes separating the girl’s space from Hyde’s space. In the first tier on the second page, the clash becomes visually unavoidable, which can be seen in the tapered shape of the triangles slicing through the pictorial space, the converging lines never allowing a right angle. At the same time, the colors show the tension but are still harmonious in the yellow wall, the red pathway, and the purple night sky; chromatically it is the equivalent of holding one’s breath. This changes when the secondary colors are introduced and then intensified by the fragmentation of space. This

disintegra-55

tion of pictorial space into many multicolored pieces next to each other, the tilting perspective, and the over-lapping elements within one panel, all add to an increasingly frantic atmosphere. Colors, shades, facets, and forms all generate feverish movement by negating a fixed viewpoint and forcing the eye to jump from anchor point to anchor point. Then again, there are scenes that essay a great sense of calm, particularly when Jekyll is in control, aware that he can no longer exist as two different entities. In the comic, this happens for example after Jekyll goes to sleep as himself and wakes up as Hyde for the first time on page 33. These scenes are in lighter, pastel colors, and the panels are more stable, often highly symmetrical in their composition. Jekyll is less separated from his environment than Hyde who, in terms of color, is often singled out and cast in a harsh background light. The same can be said of the first murder scene, in which Hyde kills the veteran and his dog. The scene is a turning point within the story, and in both colors and shapes, the narrative stops for a moment. Mattotti chooses uniform colors to illustrate this crime, mainly black with highlights in white, reminiscent of the waxen color skin tends to have after death. The colors appear flat, without depth. The even distribution of space within the panels, particularly after the preceding frenzy of Hyde’s scenes, gives the impression of stillness, symbolizing the point of no return in the story.

Conclusion

Mattotti’s affinity for modern art is generally known. However, the extent to which his comics and art influence each other, as well as the narrative meaning of the visual links between the two, has often been un-derestimated in previous analyses. His graphic adaptation of the Jekyll and Hyde novella succeeds in finding a unique and breathtaking visual expression. Though he inevitably is bound by the limitations of the medium— particularly in its move “from the imagination to the realm of direct perception” (Hutcheon 23)—he manages to find creative solutions that enrich the adapted text considerably.

Mattotti’s unique style—achieved through direct references and filtered memories—plays a major part in this. While in directly referencing particular works, he presents an easily recognizable version of an existing visual source, it is in his use of art styles in his work that he blurs the two mediums of art and comics. In ab-sorbing the style of certain art works and art movements, he evokes through filtered memories an association with similar paintings that the reader is familiar with while not being able to identify, as the association is achieved by simulating distinctive brushwork, color palette, handling of pictorial space and light-shadow-con-trasts, as well as themes and motifs typical of a certain artistic movement. These stylistic elements open up the adapted text to allow for new interpretations of the original source. The more the reader is familiar with the references present in the comic, the more he or she can enjoy their sophisticated commentary on the adapted story. Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde is a creatively autonomous work that creates a complex response to the adapted narrative and even advances the language of the comic.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Maaheen. Openness of Comics: Generating Meaning within Flexible Structures. Mississippi UP, 2016.

56

de/2014/49/oskar-schlemmer-staatsgalerie-stuttgart. Accessed 1 Sept. 2016.

Brandigi, Eleonora. L’archeologia del Graphic Novel: Il Romanzo al Naturale e Leffetto Töpffer. Firenze UP, 2013.

Brown, James H. Imagining the Text: Ekphrasis and Envisioning Courtly Identity in Wirnt von Gravenberg’s Wigalois. Brill, 2016.

Dierkes, Andreas. A Strange Case Reconsidered. Zeitgenössische Bearbeitungen von R. L. Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Königshausen and Neumann, 2009.

Mattotti, Lorenzo, and Jerry Kramsky. Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde. Casterman, 2002. Müller, Hans-Joachim. “Triptychon in Der Moderne - Kunstmuseum Stuttgart: Die Altäre Der

Moderne.” Art, 23. Jan. 2009, http://www.art-magazin.de/kunst/9349-rtkl-triptychon-der-moderne-kun-stmuseum-stuttgart-die-altaere-der-moderne. Accessed 26 Aug. 2016

Ghezzi, Enrico. “Mattottica Pinottica, Paura del Riconoscere.” Segni e colori, edited by Gianni Miriantini and Giovanna Duri, Hazard, 2000, n. pag.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation. Routledge, 2006.

Pascu, Christina-Andrea. “George Grosz und Heinrich Heine – zwei Künstler, ein Volk, ein Gedanke.” Neue Didaktik, vol. 1, 2008, pp. 87-100.

Penrod, Diane. Miss Grundy Doesn’t Teach Here Anymore: Popular Culture and the Composition Classroom. Boynton/Cook Publishers, 1997.

Rizzo, Sara. “Twopence Coloured: The Translation of Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde into Com-ic-Book Text.” European Stevenson, edited by Richard Ambrosini and Richard Dury, Cambridge Schol-ars, 2009, pp. 253-72.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. 1886. Gutenberg, https://www.guten-berg.org/files/43/43-h/43-h.htm. Accessed 1 Sept. 2016.

Torgovnick, Marianna. The Visual Arts, Pictorialism, and the Novel: James, Lawrence, and Woolf. Princeton UP, 2014.

Uhlig, Barbara. “Refiguring Modernism in European Comics: ‘New Seeing’ in the Works of Lorenzo Mattotti and Nicolas de Crécy.” European Comic Art, vol. 8, no.1, 2015, pp. 87-110.

Wolf, Norbert. Expressionism. Taschen, 2004.

Barbara Uhlig studied protohistoric archaeology and art history at the Universities of Munich, Salzburg, and

Eichstaett, and works as a book designer. She is currently writing her dissertation on narrative strategies in the work of Lorenzo Mattotti, with a special focus on the use of color in comics. Her main research interests lie in subversive art, text-image relationships, and the development of Italian comics since the 1960s.