Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

HB31

.M415

dewsy

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

DO

FIRMS

WANT

TO

BORROW

MORE?

TESTING CREDIT

CONSTRAINTS USING

A

DIRECTED

LENDING

PROGRAM*

Abhijit

Banerjee

Esther

Duflo

Working

Paper

02-25

May

2002

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can be downloaded

without

charge from

the

Social

Science

Research Network Paper

Collection

athttp://papers. ssrn,com/paper.taf?abstract id=316587

MASSACHOSEtlTiwSTFfirTr

^FTECHNOLOGY

AUG

1 2

2002

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

DO

FIRMS

WANT

TO

BORROW

MORE?

TESTING

CREDIT

CONSTRAINTS USING

A

DIRECTED

LENDING

PROGRAM*

Abhijit

Banerjee

Esther

Duflo

Working

Paper

02-25

May

2002

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper can be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research Network Paper

Collection

atDo

Firms

Want

to

Borrow

More?

Testing Credit Constraints

Using a

Directed

Lending

Program

1*

Abhijit

V.

BanerjeeWd

Esther

Duflo*May

2002

Abstract

We

begin the paper by laying out a simple methodology that allows us to determinewhether firms are credit constrained, based on

how

they react to changes in directedlend-ing programs.

The

basic idea is that while both constrained and unconstrained firmsmay

be willing to absorb all the directed credit that they can get (because it

may

be cheaperthan other sources of credit), constrained firmswill use it to expand production, while un-constrained firms will primarily use it as a substitute for other borrowing.

We

the applythis methodology to firms in India that

became

eligible for directed credit as a result of apolicy changein 1998. Using firmsthat werealready getting this kindofcreditbefore 1998

to control for time trends,

we

show that there is no evidence that directed credit is beingused as a substitute for other forms ofcredit. Instead the credit was used to financemore

production-there was significant acceleration in the rate ofgrowth of sales and profits for

thesefirms.

We

conclude thatmany

ofthe firmsmust havebeenseverely creditconstrained.Keywords: Banking, Credit constraints, India JEL: 016,

G2

*We

thank Tata Consulting Services for their help in understanding the Indian banking Industry,Sankarnaranayan for his work collecting the data, Dean Yang and Niki Klonaris for excellent research

assis-tance, and Robert Barro, Sugato Battacharya, Gary Becker, Ehanan Helpman, Sendhil Mullainathan, Kevin

Murphy, Raghuram Rajan and Christopher Udryfor veryuseful comments.

We

are particularly grateful to theadministrationandthe employeesofthebankwestudyfortheirgiving us access tothedataweuseinthispaper,

department ofEconomics, MIT.

1

Introduction

That

there are limits to access to credit is widely accepted today asan

important part ofan

economist's description of the world. Credit constraints

now

figure prominently ineconomic

analyzes ofshort-termfluctuations

and

long-term growth.1Yet

one

is hard-pressed tofind tightevidenceofthe existence ofcreditconstraints

on

firms, especiallyina developing countrysetting.This is in

some

ways

what

is tobe

expected: a firm is credit constrainedwhen

it cannotborrow

asmuch

asitwould

liketoatthegoingmarket

rateor, inotherwords,when

themarginalproductofcapital inthe firmisgreater

than

themarket

interest rate. It ishowever

notclearhow

one should go about estimating the marginal product ofcapital.

The

most

obvious approach,which

relieson

usingshockstothemarket

supply curveofcapitaltoestimatethedemand

curve,is onlyvalid under the

assumption

that thesupply is always equal todemand,

i.e., ifthe firm isnever credit constrained.

The

literature has therefore taken a less direct route:The

idea is to study the effects ofaccess to

what

are taken tobe

close substitutes for credit—

current cash flow, parental wealth,community

wealth—

on

investment. Ifthere areno

credit constraints, greater access to asubsti-tutefor credit

would

beirrelevant for theinvestment decision.While

thisliteraturehastypicallyfound

that thesecredit substitutesdo

affect investment,2 suggesting that firms areindeed creditconstrained, the interpretation of this evidence is not uncontroversial.

The

problem

is thatac-cess to these other resources is unlikely to be entirely uncorrelated with other characteristics

ofthe firm (such as productivity) that

may

influencehow much

itwants

to invest.To

takean

obvious example, a shock to cash-flow potentially contains information about the firm's future

performance.

Of

course, ifone hasenough

informationabout

the shock, one can isolate shocksthat are clearly uninformative.

Lamont's

(1997) use of oil-price shocks to look at non-oilin-vestment of oil

companies

isan example

ofthis strategy.However

it is not an accident that'SeeBernanke andGertler (1989)andKiyotakiandMoore(1997)ontheories of business cyclesbased oncredit

constraints,andBanerjeeand

Newman

(1993) andGalorandZeira (1993)ontheoriesofgrowthanddevelopment based on limitedcredit access.Theliterature onthe effectsofcash-flowon investment isenormous. Fazzari, Hubbard and Petersen (1998) provide ausefulintroduction to this literature. Theeffectsof familywealthoninvestment have alsobeen

exten-sivelystudied (seeBlanchflowerandOswald (1998),foraninterestingexample). Thereisalsoa growingliterature

the

companies

forwhich

Lamont

is able to have preciseenough

information about thenature ofshocks tend to be very large

companies

and, asemphasized by

Lamont

and

others, 3 cash-flowshocks canhave very different effects

on

big cash-rich firmsthan

on

small cash-poorfirms.4Here

we

take a differentapproach

to this question.We

make

use of a policy change thataffected the flow of directed credit to

an

identifiable subset of firms.Such

policy changes arecommon

inmany

developingand

developed countries—

even the U.S. has theCommunity

Rein-vestment Act,

which

obligesbanks

to lendmore

to specific communities.5The

advantageofourapproach

isthat it givesus aspecific exogenous shocktothesupply ofcredit to specific firms (as

compared

to a shift in the overallsupply ofcredit). Its disadvantageisthat directed credit need not

be

priced at its truemarket

price,and

therefore a shock to thesupply ofdirected credit mightlead to

more

investmentevenifthe firmisnotcredit constrained.In this paper

we

develop a simplemethodology

basedon

ideasfrom

elementaryprice theorythat allows to deal with this problem.

The

methodology

is basedon two

observations: first, ifa firm is not credit constrained then an increase in the supply ofsubsidized directed credit to

the firm

must

lead it to substitute directed credit for creditfrom

the market. Second, whileinvestment

and

thereforetotal productionmay

goup

even ifthe firm is not credit constrained,itwill onlygo

up

ifthe firm has already fully substitutedmarket

credit with directed credit.We

test these implications using firm-level datathatwe

collectedfrom

asample

of small tomedium

size firmsin India.We

make

use of achange in theso-called priority sector regulation,under

which

firms smaller than a certain limit are given priority access tobank

lending.6The

experiment

we

exploit is a 1998 reformwhich

increased themaximum

size belowwhich

a firmis eligible to receive priority sector lending.

Our

basic empirical strategy is a difference-in-difference-in-difference approach: that is,we

focuson

the changes in the rate of change in3

Kaplan and Zingales (2000) make thesamepoint.

4

The estimation of the effects of credit constraints on farmers is significantly more straightforward since variations in theweather providea powerfulsource ofexogeneous short-term variation in cashflow. Rosenzweig

and Wolpin (1993) use this strategy to study theeffect ofcredit constraints on investment in bullocks in rural

India.

5Zinman

(2002) evaluates theeffect ofcredit on small businesses using exogenous variations induced by the

CommunityReinvestmentAct.

6

Banks arepenalized for failingtolend acertain fraction ofthe portfolio to firms that classifiedto bein the

various firm

outcomes

beforeand

after the reform for firms that got included in the prioritysector as aresult ofthe

new

limit, using the corresponding changes for firms that were alreadyin theprioritysector as acontrol.

We

find thatbank

lendingand

firmrevenueswent

up

for thenewly

targeted firmsinthe year of the reform.We

findno

evidencethatthiswas accompanied by

substitution of

bank

credit for borrowingfrom

themarket

and no

evidencethat revenuegrowth

was

confined to firms thathad

fully substitutedbank

credit formarket

borrowing.As

alreadyargued, the last

two

observations are inconsistent with the firms being unconstrained in theirmarket

borrowing.We

alsousethis datatoestimate parametersoftheproductionfunction.We

find

no

evidence ofdiminishing returns to additional investment,which

reinforces the idea thatthe firms arenotatthe point

where

themarginalproduct isabout

tofallbelow

theinterest rate.Finally,

we

try to estimate the effect oftheprogram-induced

additional investmenton

profits.While

the interpretation ofthis result relieson

some

additional assumptions, it suggests a verylarge

gap between

the marginalproductand

themarket

interest rate (the point estimateisthatRs. 1

more

in loans increased profits net ofinterestpayment by

Rs. 1.36,which

ismuch

toolarge to

be

explained as just the effect ofgetting a subsidized loan).The

rest of the paper is organized as follows: the next section describes the institutionalenvironment

and

ourdata

sources, providessome

descriptive evidenceand

informally arguesthat firms

may

be

expected tobe

credit constrained in this environment.The

next sectiondevelops our empirical strategy, starting with the theory

and

ending with the equationwe

estimate.

The

penultimate section reports the results.We

conclude withsome

admittedlyspeculative discussion of

what

our results imply forcredit policy in India.2

Institutions,

Data and

Some

Descriptive

Evidence

2.1

The

Banking

Sector

inIndia

Despitethe

emergence

ofanumber

ofdynamic

private sectorbanks

and

entryby

a largenumber

offoreignbanks, the biggest

banks

inIndia areallin the publicsector, i.e., they are corporatizedbanks

with thegovernment

as the controlling share-holder.The

27 public sectorbanks

collectover

77%

ofdepositsand

comprise over90%

ofall branches.requirements not to revealthe

name

ofthebank,we

note itwas

ratedamong

the topfive publicsector banks in 1999

and

2000by

Business Today, amajor

business magazine.While banks

inIndia occasionally providelonger-termloans,financingfixedcapitalisprimar-ilytheresponsibility of specializedlong-term lendinginstitutions such asthe IndustrialFinance

Corporation ofIndia.

Banks

typically provide short-term working capitaltofirms.These

loansare given as acredit linewith apre-specified limit

and an

interestratethat issetafewpercent-agepoints aboveprime.

The

gap

betweenthe interestrateand

theprimerateisfixed in advancebased on the firm's creditrating

and

other characteristics, butcannot bemore

than4%.

Creditlines in India charge interest only

on

the part that is used and, given that the interest rate is pre-specified,many

borrowerswant

as large acredit line as theycan get.2.2

Priority

Sector

Regulation

All

banks

are required to lend at least40%

of their net credit to the "priority sector",which

includes agriculture, agricultural processing, transport industry,

and

smallscaleindustry (SSI).If banks

do

not satisfy the priority sector target, they are required to lendmoney

to specificgovernment

agenciesat very low rates of interest.In

January

1998, therewas

a change in the definition of the small scale industry sector.Before thisdate only firms with total investment inplant

and

machinery below Rs. 6.5 millionwere included in the priority sector.

The

reform extended the definition of priority sector toinclude firms with investment in plants

and machinery

up

to Rs. 30 million.The

"priority sector" targetsseem

to be binding for thebank

we

study (as well as formost

banks): every year, the bank's sharelent tothe priority sector isvery closeto

40%

(itwas

42%

in 2000-2001). It is plausible that the

bank had

to gosome

distancedown

the client qualityladder to achieve this target. Moreover, there is the issue ofthe physical cost of lending. In a

previousstudy ofthis

and

threeotherbanks

(Banerjeeand

Duflo, 2000),we

calculated that thelabor

and

administrative costs associated to lending to the SSI sectorwas

about 1.5 paisa perRupee

higher than that oflendingin theunreserved sector. This isconsistent with thecommon

view that lending to smaller clients is

more

costly.Two

thingschanged

when

the priority sector limitwas

raised: first, thebank

coulddraw

from

a larger pooland

therefore could bemore

exactingin its standards for clients. Second, itcould save

on

the cost oflendingby

focusingon

slightly larger clients. Forboth

these reasons thebank would

like to switch its lending towards thenewly

inductedmembers

ofthe priority sector. Ifthese firms were constrained in theirdemand

for credit before the policychange, onewould

expect toseean

expansion of lendingto these firms relative to firms that were already inthe priority sector.7

2.3

Data

Collection

The

data for this study were obtainedfrom one

ofthe better-performing Indian public sectorbanks. This bank, like other public sectorbanks, routinely collects balancesheet

and

profitand

loss account data

from

all firms thatborrow from

itand

compiles the data in the firm's loanfolder.

Every

year the firm alsomust

apply for renewal/extension of its credit line,and

thepaper-work for this is also stored in the folder, along with the firm's initial application.

The

folderis typically stored in the

branch

until it is completely full.With

the help of employeesfrom

this bank, as well as a formerbank

officer,we

extracteddata

from

the loan folders in the spring of 2000.We

collected general information about theclient (product description, investment in plant

and

machinery, date of incorporation ofunits,length orthe relationshipwiththebank, currentlimits for

term

loans,working

capital,and

letterofcredit).

We

also recorded asummary

ofthe balance sheetand

profitand

loss informationcollected

by

thebank, as well as informationabout

thebank's decisionregarding theamount

ofcredit to extend tothe firm,

and

the interest rate charged.As

we

discuss inmore

detail below, part ofour empirical strategy called for acomparison

between

accounts that have alwaysbeen

a part of thepriority sector,and

accountsthatbecame

part of the priority sector in 1998.

We

first selected all the branches that handle businessaccounts in the 6

major

regions of the bank's operation (includingNew

Delhiand Mumbai).

Ineach ofthese branches,

we

collected informationon

all the accounts belonging to the prioritysector.

We

collected dataon

atotal of 253 firms, including 93 firms with investment in plants Theincrease in lending to larger firmsmay

come entirely atthe expenseofsmaller firms (without affectingtotal lending to the priority sector), or the reform could cause an increase in the amount lent to the priority sector.

We

will focus on the comparison between firms that were newly labelled aspriority sector and smallerand machinery between

6.5and

30 million rupees.We

aimed

tocollect datafor the years1996-1999, but

when

a folder is full, older information is not always kept in the branch.We

have1996data

on

lending for 120 accounts (ofthe 166 firmsthathad

started their relationshipwiththe

banks by

1996), 1997 data for 175 accounts (of 191 possible accounts), 1998 data for 226accounts (of 238),

and

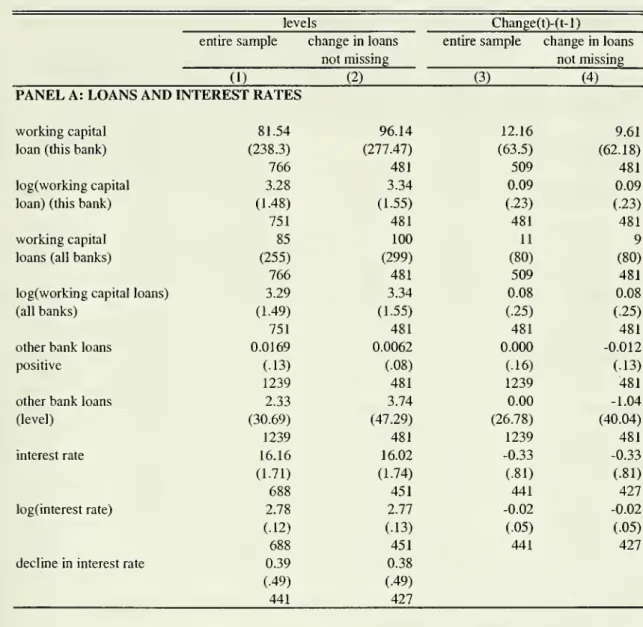

1999 data for 240 accounts. Table 1 presents thesummary

statistics forall data that will be used in the analysis of credit constraint

and

credit rationing (in the fullsample,

and

in the sample forwhich

we

have informationon

the change in lendingbetween

theprevious period

and

that period,which

will be thesample

ofinterest for the analysis).2.4

Descriptive

Evidence

on Lending

Decisions

Inthissubsection,

we

providesome

description oflending decisionsinthebanking

sector.We

usethisevidence to argue that this is

an

environmentwhere

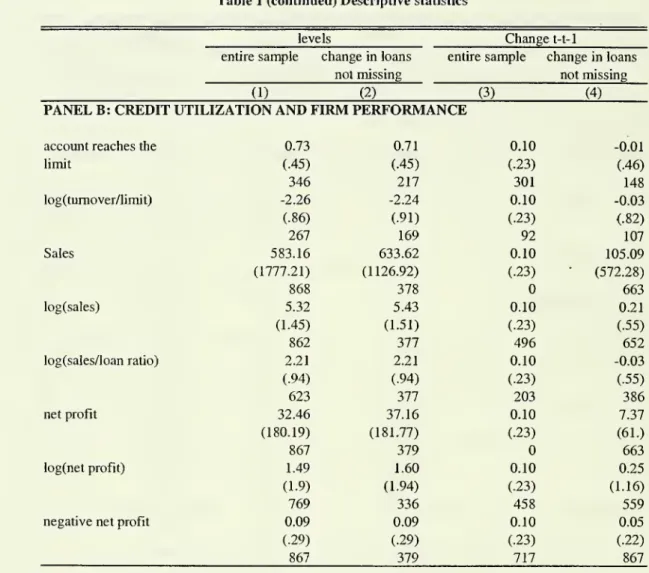

credit constraints arisequite naturally.Tables 2

and

3show

descriptive statistics regarding the loans in the sample.The

firstrow

oftable 2

shows

that, in a majority ofcases, the loan limit does not changefrom

year to year:in 1999, the limit

was

notupdated

even innominal

terms for65%

of the loans. This is notbecause thelimit is set so high that it is essentially non-binding:

row

2shows

that in the threeyears in the sample,

69%

to80%

ofthe accounts reached or exceeded the credit limit at leastonce in theyear.

Thislack of

growth

in thecredit limit grantedby

thebank

isparticularly striking giventhattheIndian

economy

registerednominal

growth

rates of over12%

per year. Thiswould

suggestthat the

demand

forbank

credit should haveincreasedfrom

year to year over the period, unlessthe firms have increasing access to another source of finance.

There

isno

evidence that theywereusing

any

other formalsource ofcredit forworking

capital.On

average98%

oftheworkingcapitalloans providedto firms inour

sample

come

from

this onebank and

inany

case, thesame

kind ofinertia

shows

up

in the dataon

totalbank

loans to. the firm.That

thedemand

forformalsectorcredit increasedfrom

year toyear, issuggestedby

rows4and

5 in table 2.The

bank'sofficial guidelines for lending explicitlystate that thebank

shouldtry to

meet

the legitimate needs ofthe borrower. For this reason, themaximum

lending limitsthat can be authorized

by

thebank

are explicitly linked to the projected sales of the borrower.lendinglimit

on

the basis of the turnover.8Row

3shows

that actual sales have increasedfrom

year to year for

most

firms.Rows

4and

5show

thatboth

projected salesand

themaximum

authorizedlendingalsoincreased

from

year to yearin a largemajorityofcases. Yet therewas no

correspondingchange inlending

from

thebank.The

changein the credit limitthatwas

actuallysanctioned thus fell systematically short of

what

thebank

determined to be the firm's needsas determined

by

the bank. In 1999,80%

of the actual limits granted were below20%

ofthepredicted sales,

and

60%

werebelow

themaximum

limit calculatedby

the banker.On

average,thegranted limit

was

89%

ofthemaximum

authorizedlimit,and

67%

ofwhat

followingtherulebased

on

20%

ofpredicted saleswould

give. Itis possible thatsome

oftheshortfallwas

coveredby

informalcredit, includingtradecredit: accordingto thebalancesheet, totalcurrentliabilitiesexcluding

bank

credit increasedby

3.8%

every yearon

average.9However,

some

expenses (suchaswages) aretypically not covered

by

tradecredit and, moreover, trade credit could berationedas well.

The

question that is at the heart of this paper iswhether

suchsubstitution operates tothe point

where

a firm isnot credit constrained.In table 3,

we

examine

inmore

detailwhether

this tendency couldbe

explainedby

otherfactors that

might

have affected a firm's need for credit.Column

(3)shows

thatno

variablewe

observe

seems

to explainwhy

afirm's credit limitwas

changed: firms arenotmore

likely to getan

increase in limit ifthey reached themaximum

limit in the previous year, iftheir projectedsales (according to the bank itself)

have

increased, if their current sales have increased, if theratio ofprofitstosaleshas increased, orifthe currentratio (the ratioofcurrentassetstocurrent

liabilities, a traditional indicator of

how

secure aworking

capital loan is, in India as well as inthe U.S.) has increased.

Turning

to thedirection or themagnitude

ofchanges, onlyan

increasein projected sales or current sales predicts

an

increase in granted limit,and

only an increase inprojected salespredict thelevelofincrease. This couldwell be

due

to reversecausality, however:The

bank

officer couldbe

more

likely to predict a larger increase in saleswhen

he is willing to give a larger credit extension to the firm.One

reasonthegranted limitmay

not change isthat the previous year's limit alreadyincor-8

Theexact ruleisthat the limitonturnover basis shouldbe the

minimum

of20% ofthe projectedsales and 25% oftheprojectedsalesminusthe finances available to the firmfrom other sources. In practice, themaximum

limitcalculated by thebank officeris not alwaysequal to thiscalculated number.

porated all information relevant to the lending decision: the limit is not responsive to

what

iscurrently going

on

in the firm, because these are just short-run fluctuationswhich

tell us littleabout the future of the firm. Ifthis were the case,

we

should observe that granted limits aremuch

more

responsive to these factors foryoung

firms than for old firms.Columns

5and

6 intable 3 repeat the analysis, breaking the

sample

into recentand

older clients.Changes

in limitsare

more

frequent foryounger clients, but theydo

notseem

tobe

more

sensitive toeither pastutilization, increases in projected sales, or profits.

The

fact that the probability of a limit's change is entirelyuncorrected

with observablefirm characteristics is striking.

One

plausible theory relates this to the fact, noted above, thatchanges in the limit are surprisingly rare. If

bank

officials are reluctant to change the limit,a large fraction of the observed changes

may

reflect effective lobbying or something purelyprocedural ("it has been fiveyears since the limit

was

raised") ratherthaneconomic

rationality.What

explains the reluctance of loan officers todo

what

is, palpably, their job?A

recentreport

on

banking policiescommissioned by

the ReserveBank

of India suggests one potentialexplanation:

"The

[working group] observed that it has received representationsfrom

theman-agement and

the unions ofthebank

complaining about the diffidence in taking credit decisions withwhich

thebanks

are beset at present. This isdue

to investigationsby

outside agencieson

the accountability ofstaffin respect toNon

Performing Assets."(Tannan

(2001)). In otherwords, the

problem

is that changing the limit (in either direction) involves sticking one's neckout-ifone cuts the limit the firm

may

complain,and

ifone raises it, there is a possibility onewould

be held responsible ifthe loan goes bad: the Central VigilanceCommission

(agovern-ment body

entrusted with monitoring the probity of publicofficials) is formallynotified ofeveryinstance of a

bad

loan in a public sector bank,and

investigates a fraction of them.10Simply

renewing the loan without changing the

amount

is one easyway

to avoid such responsibility,especially if the original decision

was someone

else's (loan officers are frequently transferred).The

problem

is likely exacerbatedby

thefact thatthe linkbetween

theprofitabilityofthebank

and

the prospects ofan

individual loan officer, is, at best, ratherweak.Whatever

the explanation, thefactthatthebank

doesnotseem

to be respondingtochanges10There

were 1380 investigations ofbank officers in 2000 for credit related frauds, 55% of which resulted in

inthefirm's creditneeds,suggests that

some

firmswould

havean

unmet

demand

forbank

credit.Of

course the firm couldborrow from

themarket

(e.g., use trade credit, or moneylenders) tosupplement

what

it getsfrom

thebanking

system. Nevertheless, it doesmake

itmore

plausiblethat the firmswill

be

credit constrained.3

Establishing

Credit Constraints

3.1

Theory

Consider a firm with the following fairly standard production technology: the firm

must pay

a fixed cost

C

before starting production (say the cost of settingup

the factoryand

installingthe machinery).

The

firm then invests in laborand

other variable inputs, k rupees ofworking

capital invested in variable inputs, yield

R

=

F(k)

rupees of revenue after a suitable period.F(k)

has the usualshape

—

it is increasingand

concave.Denote

themarket

rate of interest in thiseconomy

by

rm

and

the interest rateon

bank

lending

by

r^. Sincetheinterest ratethat public sectorbanks

wereallowed to chargeon

prioritysector lending

was capped

above, thereisreasonto believe that thebank

lending ratewas

belowthe market rate: r\>

<

rm

.We

will say that a firm is credit rationed ifat either ofthe interestrates it faces, it

would

like toborrow

more.We

will say it is credit constrained ifitwants

toborrow

more

at themarket

interest rate. It is clear that being credit constrained implies beingcredit rationed, but not the other

way

around.The

policy changewe

analyze involved the firms in question being offered additionalbank

credit.

We

willshow

in thenext section that therewas

no

corresponding changeinthe interest rate.To

the extent that firmsaccepted the additionalcredit being offeredtothem, this is directevidence ofcredit rationing.

However

this initselfdoes notimply

that theywould

haveborrowed

more

at themarket

interest rate.A

possiblescenario is depicted in figure 1.The

horizontal axis in the figure measures k whilethevertical axis represents output.The downward

slopingcurvein thefigure represents themarginal productofcapital, F'(k).

The

step function represents thesupply of capital. In the case represented in the figure,

we

assume

that the firm has access tofcfco unitsof capital at the

bank

rater;, butwas

freetoborrow

asmuch

as itwanted

at the higherwhere

the marginal product ofcapital is equal to rm

. Its total outlay in this equilibrium isfco-Now

considerwhat happens

ifthe firm isnow

allowed toborrow

a greateramount, k^,

at thebank

rate. Clearly since at kbi the marginal product of capital is higherthan

r^, the firm willborrow

the entire additionalamount

offered to it.Moreover

it will continue toborrow

at themarket

interest rate,though

theamount

isnow

reduced.The

totaloutlayhowever

isunchanged

at ko- Thiswillremain the caseaslong as kbi

<

ko:The

effect ofthe policywillbe

tosubstitutemarket

borrowing bybank

loans.The

firmsprofits will goup

becauseofthe additional subsidies but its total outlayand

output willremain

unchanged.The

expansion ofbank

credit will have output effects in this setting if kbi>

^o- In thiscase the firm will stop borrowing

from

themarket

and

the marginal cost of credit it faces willrb. It will

borrow

asmuch

it can get from thebank

butno

more

than

fc(,2, the pointwhere

themarginal product of capital is equal to r&.

We

summarize

thesearguments

in:Result

1: If the firm is not credit constrained (i.e., it canborrow

asmuch

as itwants

atthe

market

rate), but is rationed forbank

loans,an

expansion ofthe availabilityofbank

creditshould always lead to a fall in its borrowing

from

themarket

as long as r;,<

rm

. Profits willalsogo

up

as longasmarket

borrowingfalls.However

thefirm's totaloutlayand

output willgoup

only ifthe priority sector credit fully substitutes for itsmarket

borrowing. Ifrb=

rm

, theexpansion ofthe availability of

bank

credit will haveno

effecton

outlay, output or profits.We

contrast this with the scenario in figure 2,where

the assumption is that the firm isrationed in

both

marketsand

is therefore credit constrained. In the initial situation the firmborrowsthe

maximum

possibleamount

from

thebanks

(fcfco)and

supplementsit with borrowingthe

maximum

possibleamount

from

the market, for a total investment of ko- Available creditfrom

thebank

thengoesup

tokbi This hasno

effecton market

borrowing(sincethetotaloutlayis still less than

what

the firmwould

like at the rate rm

)and

therefore total outlayexpands

tofci.

There

is a corresponding expansion ofoutputand

profits.11Result

2: Ifthe firm is credit constrained,an

expansion ofthe availability ofbank

creditwill lead to an increase in its total outlay, output

and

profits, withoutany

change inmarket

borrowing.

11

Ofcourse, iffc

pi wereso large that F'(kp\)

<

rm

, then there wouldbe substitution ofmarket borrowing inthis caseas well.

We

haveassumed

aparticularly simpleform

ofthe credit constraint. If instead of thestrictrationing

we

haveassumed

here, there isan

upward

supply curve for credit market, there willbe

a decrease inmarket

borrowing as a result ofthe increase in formal lending.The

importantpoint, however, is that the increase in sales

and

profit will take place even ifthe increase inbank

borrowing does notfullysubstitutefor theentiremarket

borrowing.The

results alsogoesthrough if the

market

supply curve of credit is itself a function ofbank

credit (forexample

because

bank

credit serves as collateral formarket

credit). In this case, theremight be an

increase in

market

borrowing as the result ofthe reform.The

instrumental variable estimatewe

will present below will then bean

estimate ofthe total effect ofthe increase inbank

credit,inclusive ofthe induced effect

on market

credit.3.2

Empirical

Strategy:

Reduced

Form

Estimates

The

empiricalwork

follows directlyfrom

the previous subsection,and

seeks to establish thefactsthat will allow us todetermine

whether

firms arecredit rationed,and

to distinguishcreditrationing

from

credit constraint.Our

empirical strategy takes advantage of the extension ofthe priority sector definition in1998.

As we

described above, the reform extended the definition ofthe prioritysector to firmswith investmentinplants

and machinery between

Rs. 6.5and

30million.As

we

noted, sincethepriority sector target

(40%

of the lending portfolio)was

binding for ourbank

beforeand

afterthis reform, there is

good

reason to believe that the reform reduced theshadow

cost of lendingfor the bigger firms

newly

includedinthepriority sector,and

thusresultedinan

increase in theircredit.

The

reform did notseem

tohavelarge effectson

thecompositionofclientsofthe banks:In the sample,

25%

ofthe small firm,and

28%

ofthe big firms, have entered their relationshipwith the

bank

in 1998 or 1999. Thus, oursample

is not obviously biasedby

the reform.Since thegranted limit, as well as all the

outcomes

we

will consider, arevery stronglyauto-correlated,

we

focuson

the proportionalchange

in this limit, i.e., log(limit granted inyear t)—

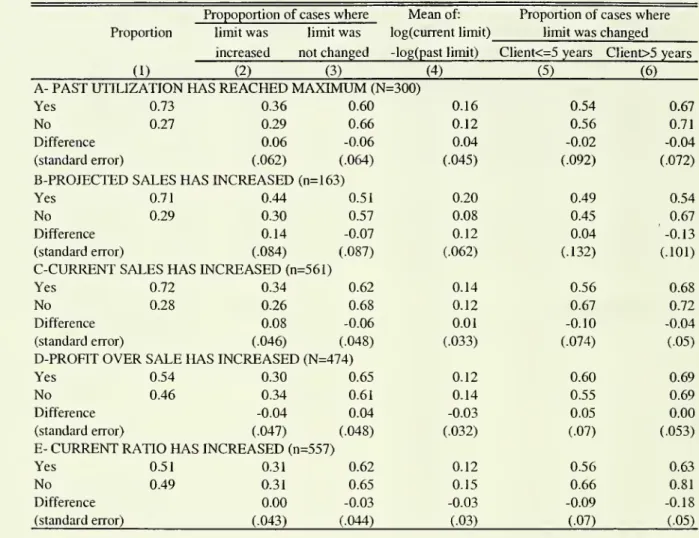

log(limit granted in year t-1). Table 4shows

the average changein thecredit limit facedby

the firmbetween

period t—

1and

period t for 1997, 1998,and

1999.The

averageenhancement

was 5.7%

larger for small firms than for bigfirmsbetween

in 1997, whereas in 1998 itwas 3.6%

larger for big firms. In fact the size ofthe averageenhancement grew

for big firmsand

shrunkfor the small ones. In 1999, the size ofthe average

enhancement

was

almost exactly thesame

for small

and

large firms. This suggests thatbanks

adjusted to thechange

in credit policyby

raising the credit limit ofthe large firms once,

and

then placedboth

largeand

small firmson

the

same

trajectoryPanel

B

intable4shows

that theaverage increaseinenhancement

was

notdue

toan

increasein the probability that the working capital limit

was changed

: big firms did notbecome

more

likely to experience achange in 1998 or 1999 thanin 1997. This

may

appear surprising, but it is entirely consistent with the previous evidenceshowing

that it is not possible to explainwhy

certain firms experienced a change in their credit limit. It is plausible that the

same

kind ofbureaucratic inertiais at

work

here as well.While

loan officersdo

need to respond to pressurefrom

thebank

toexpand

lending to thenewly

eligiblebigfirms, theyseem

toprefergivinglargerincreases to those

which

would

havereceivedan

increase in anycase (forone

reasonoranother),

rather than increasing the

number

of firms that receive enhancements.InPanel C,

we

show

the average increaseinlimit, conditionalon

thelimit changing.The

av-eragepercentage

enhancement was

23%

higher forsmall firms (andthisdifference issignificant).

It

was

3%

higher forthe large firms in 1998.Our

strategy will be to use this change in policy as a source of shock to the availability ofbank

credit to these firms, using firms outside this category to control for possible trends.The

first step

however

is to formally establish that therewas

indeed such a shock.To

do

thiswe

estimate an equation ofthe form:

logkut

-

logkbit-i=

a

kbBIGi

+

f3kbPOST

+

lkbBIGi

*POST

t+

ekbiu (1)where

kbit is ameasure

ofbank

credit to firm i in year t,BIG

is adummy

indicating whetherthe firm has investment in plant

and machinery between

Us. 6.5 millionsand

Rs. 30 millions,and

POST

is adummy

equal to one in the years 1998and

1999.We

use anumber

ofdifferentmeasuresof

banks

loans: working capitalloansfrom

thisbank, totalworking

capital loansfrom

the

banking

sector,and

totalterm

loans. Forworking

capital loans,we

expect a positive 75.We

do

notexpect achange interm

loansin the years immediately following the reform, sinceittakes

some

time for a fixed capitalinvestment project to be plannedand

processed.As

pointed out in the previous subsection, the impact of the shockon

the firmdepends

crucially

on whether

the firmwas

credit constrained, credit rationed or entirely unconstrained.Inorder to distinguish

between

these caseswe

need tolook at anumber

ofothercredit variablesfor the firm.

We

thereforerun anumber

ofother regressions that exactly parallel equation 1:yu

-

Va-i=

a

yBIGi

+

(3y

POST

t+

lyBIG

% *POST

t+

eyit, (2)where yu

is a credit variable for firm i in year t. 12• Credit rationing

Our

Result 1 above suggests that to establish credit rationing,we

need

two

more

pieces ofevidence.

First, sincethe working capital loans take the

form

ofa line ofcredit (and firms are charged only forwhat

they use),we

need

toexamine

what

happened

to the rate atwhich

firmsdraw

upon

theirgranted limit.We

thus use as ourmeasure

ofcredit utilization, the logarithm oftheratioof turnover on accounts (the

sum

ofall debts overthe past year) to the credit limit.Second, this

would

notbe

evidence ofcredit rationing ifthe interest rate chargedon

thisloan decreased at the

same

time. Priority sectors loans are notsupposed

to have lower interestrates (the interest rate charged

on

a loan is the prime lending rate plus apremium

depending

on

thecredit rating of thefirm-without regard forits status), sothere isno prima

facie reasonthe rate should fall. However,

we

directly checkwhether

there is evidence ofthis using threespecifications: using

y

it—

r^in

equation (1) , forr^t equaltothe interestrate in logarithmand

in level,

and

replacingyu

—

yu-\ in equation (2)by

adummy

indicatingwhether

the interestrate fell.

• Credit constraints

Credit rationing does not necessarily imply credit constraint.

To

investigatewhether

thefirms were credit constrained,

we

look at anumber

ofother pieces of evidence.First, ifa firmwerecredit constrained, our theorytells usthat salesrevenue

would

definitelygo

up, while if it were not, sales should only goup

forfirms that have already fully substitutedbank

credit for theirmarket

borrowing.To

look at the effect ofcredit expansionon

sales,we

posit asimple parametric relation

between

creditand

salesrevenue:Ru

=

Aitku

.Note

thatthisStandarderrorsare correctedfor heteroskedasticity andclustering atthefirm andsector level.

isaspecific parametrizationofthe production functionintroducedinthe previous sub-section.13

log

Rn

=

logA

it+

loght

(3)Differencingthis equation gives:

log Rit

-

\ogRit-i=

logA

it-

log Ait-i+

0[logku

-

logfcjt-i]. (4)We

have already posited that thegrowth

ofbank

credit is given by:logfcwt

-

logfcw,-!=

a

kbBIGi

+

(3kbPOST

t+

^

kbBIGi

*POST

t+

e kbit,In theabsence ofcomplete substitution

between

bank

creditand market

credit, this impliesa relationship of the

same

shape for capitalstock:logku

-

loght-i=

a

kBIGi

+

(3kPOST

t+

7

kbBIG

t *POST

t+

ekit,which

when

substituted in equation (4) yieldslog

Ru

-

logRit-!=

log Ait-

logAn^

+

0[akBIGi

+

P

kPOST

t+

i

kBIGi

*POST

t+

ekit]. (5)Since

we

do

not observe log^4it—

log^t-i

directly,we

end

up

estimating an equation thatexactly

mimics

equation 2 above:log^t

-

logife-!=

a R

BIGi

+

f3R

POST

t+

lR BIGi

*POST

t+

v

kit]. (6)Our

identificationhypothesis is thatlog

A

it~

logAa-!

=

a

A

BIG

l+

(3A

POST

t+

w«

, (7)where

omegau

is uncorrelated withBIG

*POST.

Thisamounts

toassuming

that the rate ofchange of

A

(whichis ashift parameter intheproduction function) did not changedifferentiallyfor big

and

small firms in the year of the policy reform.Under

this assumption7^

gives thereduced

form

effect oftheprogram on

sales revenue.13

This is bestthought of asa reduced form, derived from a moreprimitive technology which makesoutput a

Cobb-Douglasfunction of theamountofn inputsx\,x?....xn. Aslong as theinputshave topurchased usingthe

working capitalandall inputs are purchasedin competitive markets, it can be shownthat the resulting indirect production function has theformgiven above.

Iffirms arecredit constrained

7#

shouldbe

positive, while ifno

firms arecredit constrainedjR

will onlybe

positive for those firms that havefully substitutedmarket

credit.We

thereforealso estimateaversion ofequation 6 inthe

sample

offirmswhose

total current liabilities exceedtheir

bank

credit. Ifthe firmswere

not creditconstrained, thevalue of7^

in thissample

shouldbe

zero.A

second strategy is to lookat substitution directly. Unfortunatelywe

do

not have reliabledata

on market

borrowing.We

therefore adopt the following strategy: equation (4)above

canbe

rewritten in the form:log Rit/kbit

-

log Rit-i/kbit-i=

logAn ~

logAit-i+9{\og ku

~

logfcft-i]-

[logkbit-

logkbit-i]. (8)Differencing one

more

time gives us[logRit/kbit -logRit-i/kbit-i]

-

[logRit-i/kbit-i-log Ra-2/hu-2]

=

[logAn -

log Ait-i]-

[logAit-i-

logAn-2]

+0([log

ku/

kbit-

logkit-i/kbit-i]~

[logkit-i/kbit-i-

logkit_2/kbit-2})-(1

-

9)([logk^t-

logkbit-i]-

[logkbit-i-

logkbit-2])- (9)We

now

take the difference ofthis expression for big firmsand

that for small firms.Denoting

by

the operatorA

theoperation ofdifferenceacross firm categoriesand

using (7)we

getA{

[logRt/ht

-

logRt-i/ht-i]-

[logRt-i/ht-i-

logRt-

2/k

bt-2]}=

OA{([logkt/kbt-

logkt-i/ht-i]~

[logkt-i/kbt-i-

logfct_2 /fcfct_

2])}-(1

-

9)A{[logk

bt-

logkbt-!]-

[loght-i-

loght-2}}. (10)We

have suggested,and

willshow

formallybelow

that A{[logk

bt

—

logkbt-i]—

[logkbt-i—

logA;bt_2]} is positive

when we

compare

pre-reformand

post-reform periods. If a firm is notcredit constrained it should substitute

bank

loans formarket

loans,which

implies thatbank

capital should

grow

fasterthan

total capital stockfor the big firms after the reform, relative tothe smallfirms. A{([log kt/kbt

-

logfct-iA&t-i]-

[logfct-i/fcw-i-

log^-2/^-2])}

isthereforenegative.

As

long as 9<

1, thesetwo

observations together imply that the expressionon

the right shouldbe

negative. If 9>

1, this need notbe

necessarily be case, but with increasingreturn to scale there cannot

be

an

equilibrium inwhich

thefirms are not credit constrained.We

implement

thisby

estimatingequation 2withy,t=

^ Ifthe firmiscredit constrained,7wk

hshould be negative. Ifnot,we

presume

that there isno

substitution.A

final pieceofevidencecomes from

looking at profits.Assuming

that the firmbuys

all itsinputs using its

working

capital,we

can writeriit

=

Auikbit+

km

it)9

-(1

+

rbi^kfct-

(1+

rmit)kmit-

C.It follows that

d\ogTijt

_

A

it(kbit+

kmit)e

d\og

A

it 9Ait{kbit+

kTnit)e~1

kbi

t-{l

+

rbit)kbitd\ogkbitdt

n

dtn

dt6

Ag

(kbit+

km

it) ~ km

jt—

(1+

Tm

ii)km

j tdlogk

m

n

'Tmitkm.itd\ogr

m

itn

dtn

dt 'ignoring the effect of changes in the

bank

interest rate, which, given evidence tobe

shown

later, does not

seem

tobemuch

of an issue. Ifthe firmwas

not credit constrained, kmitwould

be chosen optimally

and

thereforewe

candrop

the thirdterm

in this expression.Taking

timederivatives again

and

droppingall termsthat involveaproductoftwo

ratesofchange (assuming that rates of change are always smalland

therefore their products are going to be negligible),we

getrf2logII;t

_

Aujkbit+

kmit)e

d

2logA

it9A

u

{kbit+

kmit) e~lkbit

-

{\+

rbit)kbitd

2

\ogk

bi t dt2n

dt2n

dt2 rmitkmitdtlogrmitn

dt2 'Comparing

bigand

small firms,and

invoking theA

operator again,we

have:d

2logn

tA

t(kbt+

km

t)°d

2 logA

tA

t(kbt+

km

t) 9d

2logA

t , 1 dt2 ]~

{n

] dt2+

n

{ dt2 *A

rrm

tkmt~. d 2 logrmt_

rmtfcmt ri2logrmt ^ 1n

i dt2n

{ dt2 j9A

t{kbt+

kmt) 9-l kbt-

(1+

rbt)kbt d 2 logkbt {n

dt2 } 16Now

—

"^a""" should be thesame

forboth

largeand

small firms, since it is themarket

interest rate. ThereforeA{

d2'°^rmt}

=

0.By

equation 7 above,A{

d2]°$At}=

0. Thisleaves us with:d

2logIIt_

A

t(kbt+

kmt) ed

2logA

t { dt2 * xn

* dt2[n)

A

,rm

tkmtd

2 logrmt9A

t{kbt+

km

t) e-l kbt-

(1+

rbt)kbt d 2 logkbt {n

] dt2+

{n

dt2 j 'The

lastterm

here is the effect of the reform.To

separate itfrom

other time varying effects,thefirst

two

termsmust be

smallenough

tobe

ignored.The

second term,A{

Tr^^

nt }d

'"^Z"""

can safely be

assumed

to be small. It hasbeen

shown

that, in India, the average interest rateon

the internalmarket

is linked to thebank

rate.—

^/

mt is thus closely linked to—

°^rt",

which

is givenby

thePOST

dummy

when

we

estimate equation (2) withrbt as thedependent

variable. Below,

we

estimate this coefficient tobe

-0.16 percentage point (the average interestrate is 14%).

One

scenariowhere

/\{At{kbt^

krnt)<>}d2l°

t%

At

is small is if

^$

At is small.That would be

trueifeither there

was

notmuch

changein At or iftherewas

a directional trend but notmuch

variation

around

the trend.Assuming

thatA{

rmt£

mt}d l

°$2mt is indeed small, this hypothesis

can

be

directly testedby

looking at the coefficient of thePOST

dummy

when we

estimateequation (2) withprofits asthe

dependent

variable: thecoefficient ofthePOST

dummy

willbe

equal to

^{

^k

ht+kmt)'y

<P\^A

tfor the

smaU

firms ginceA

^A

t{kbt+kmt)^

ig nQt equaJ tQ zer^

iftheproduct is zero,

—

°ff

'

must be

zero.Note

thatthe effectofthereformon profit isdue

to thegap between

themarginalproduct ofcapital

and

the bank interest rate: inother words, it combines the subsidy effectand

thecreditconstraint effect: even iffirms were notcredit constrained, their profit

would

still increase afterthereformif

more

subsidized credit ismade

availabletothem, because they substitutecheapercapital for expansive capital.

3.3

Empirical

Strategy:

Testing

the

Identification

assumptions

The

interpretation ofthe centralresulton

salesgrowth

cruciallydepends

on

theassumption

made

inequation (7). Likewise, the interpretation of the otherresults

depends on

theassumption

thattheerror

term

isnot correlatedwith theregressors,most

notablyBIG*POST.

However, thereare

many

reasonswhy

this assumptionmay

not hold. For example, bigand

small firmsmay

be

differentlyaffected by other measuresof

economic

policy (theycould tendtobelong to different sectors, with different policies during these years). Moreover, being labeled as a priority sectorfirm

may

have consequences for big firms overand

above its effectson

credit access.There

are three other

ways

in which being included in the priority sectormay

affect firms. First, SSIfirms are

exempt from

some

types of excise taxation. Second, SSI firmsmay

have better accessto

term

loans. Third, the right to manufacture certain products is reserved for the SSI sector.We

will address the first concernby

using profit beforetax,and

the secondby showing

that inthe time span covered by our dataset, reform did not significantly affect

term

borrowing.The

third concern could be a problem:

among

the small firms,44%

manufacture a product that isreserved for SSI.

Among

the big firms,24%

do.One

control strategywould

be to leave out allfirms that manufacture products that are reserved for SSI. Unfortunately,

we

onlyknow

what

products the firm

manufactured

in 1998. It remains possible thatsome

ofthe big firmsmoved

into reserved products after 1998

and

this increased their profits.As

away

totest ouridentificationassumptionand

toimprove

the precision of the estimates,we

will estimate equation (2) for thedifferentoutcomes

variables separately usingtwo

samples:the

sample

where

therewas no

change in the granted limitfrom

oneyear to the next,and

thesample

where

therewas

a change (either an increase or decrease). In doing so,we

make

use ofthe fact, noted above,and

shown

more

formally below, that the probability ofa change inthe limit appears to be unaffected

by

the policy change (the variableBIG

*POST).

Given

this fact,

and

a simple monotonicity assumption, estimatingan equation oftheform

ofequation(2) separately in the sample

where

therewas

a change in limitand

in thesample

where

therewas no

change in limit will lead to consistent estimates of the parameter of interest7

inboth

subsamples

(Heckman

(1979),Heckman

and

Robb

(1986)).Specifically, denote

q

a variable equal to 1 ifthere is a change in limitand

otherwise, Zithe interaction

BIG

*POST,

and

Xi

the vector(Bid,

POST).

Define en as the potentialselection status

when

Zi=

1and qo

as the potential selection statuswhen

Zi=

0.14Assume

that (i) (€i,{cn,Cio)) are jointly independent of Zi conditional

on Xi

(ii) one of the followingis true: conditional

on

Xi, en>=

chq for all i or Cn>=

chq for all i.The

first assumptionguarantees the validity of Zi as a regressor in the complete sample (but not in the selected

For eachobservation, wewillobserve only eitherc,i or Cio

sample),

and

that the marginal distribution ofqo

and

Qi (but not the joint distribution) areidentified in a

sample

with dataon

Ziand

c*.The

secondassumption

restricts the relationshipbetween

the instrumentand

selection to be monotonic: for all firms, the instrumentmakes

iteither

more

likelyor less likely to experience achange

inlimit.15Given

thesetwo

assumptions, P(ci=

\\Zi=

1)=

P(cj=

l\Zi=

0) implies that (ci,€i) is jointlyindependentof Zi conditionalon

Xi

(fora proofusingthis notation, seeAngrist (1995)).Therefore, E[ei\a

=

l,Zi=

l,Xi]=

E[ei\*=

1,Z,=

0,Xi],and

E[ei\*=

0,Zi=

1,X

Z]=

E[€i\ci

=

0,Zi=

0,Xi\: theOLS

assumptions are satisfied inboth

subsamples.This implies that the independence

assumption

(which is equivalent to the assumption inequation(7)can

be

tested as longasP(ct=

l\Zi=

1)=

P(ci=

l\Zi=

0). Thislaterassumptioncan inturn

be

shown

toholdby

regressingthe probability ofachange

in limiton

the interactionBIG

*POST

(andfinding a coefficient ofzeroon

thisvariable).The

test oftheidentificationassumption

is torun regressions oftheform

(2) in thesample

with

no

increase in credit limit: since the coefficient ofthe variableBIG

*POST

iszero inthecredit equation, it should also

be

zero in the regression of the other outcomes.Of

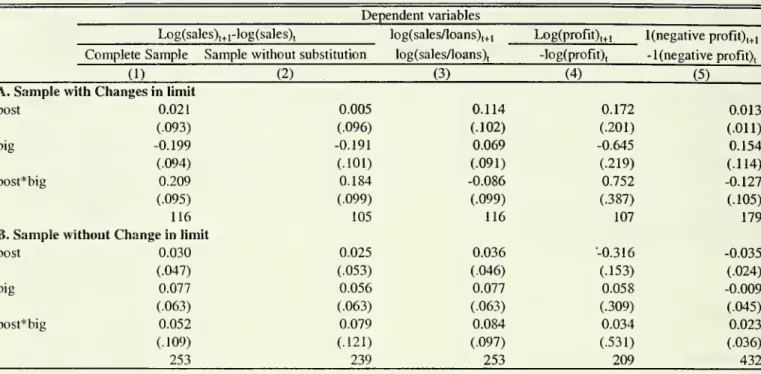

particularinterest, obviously, arethe coefficients intheequation ofsales

and

profit. Ifthe firms are creditconstrained,

we

expect the coefficientsofBIG

*POST

tobe

positive inthesample

with creditlimit changes,

and

equal to zero in thesample

withno

changes in loans.3.4

Empirical

Strategy: Structural

Estimates

The

fact that the firms are credit constrained tells us that the marginal product of capital ishigher

than

themarket

interest rate.The

question is,by

how

much?

We

beginby

observing thatan

alternative to estimating equation (4) is to estimate thestructural relationship (4) using

BIGi

*POST

t asan

instrument.16

This

would

allow us to10

The latentindex formulation with alinearmodel Unkingthe latent variable to theinstrument satisfiesthese

two assumptions. However, the assumptions are not necessarilytrue: in particular,one could imagine thatthe limitfroma big firm ismorelikelytobeleft atzerothantobedecreased, butmorelikelytobeincreased thanto

be left at 0. Thiswould violate the monotonicity assumption.

We

will presentevidence belowthat this did notseemtohave happened.

1

Following the discussion in the previoussubsection, we will run this IV regression in the samplewherewe

observean increasein loans.

estimate 6, the elasticity of revenue with respect to

working

capital investment. It isworth

observing that for

an

equilibrium without credit rationing to exist itmust be

the case that9

<

1 in theneighborhood ofthe equilibrium: otherwise the marginal product ofcapital is notdeclining at the equilibrium,

which

rules out it being anoptimum

foran

unconstrained firm.Conversely, finding that 6

>

1,makes

it likely that there arecredit constraints inequilibrium.In practice, as

we

have already mentioned,we

do

not have ameasure

of kit, but only ameasure

ofkbit- Rewriting structural equation (4),we

obtain:log Rtt

=

logA

it+

6logkbit~

01og^|.

(12)Differencingover time:

log

Ru

-logR.t-i

=

logA

it-

logAit-i+

6(log^

-logkbit-i)-9[log~

~

]ogkti-l

^'^

The

term

0[log-^ —

logTjjrff],which

is omitted in the regression, is positively affectedby

thereform inthe presence of

any

substitution ofbank

credit formarket

credit. Thus,when

we

useBid

*POST

t asan

instrument for logfc^(,we

obtain alowerbound

for 0.The

expressionwe

derivedfortheprofitratewas

directlyexpressedasafunction ofdifference-in-difference in the rate of changes of

bank

credit. Thus, to seewhat

happens

to profit,we

estimate the equation

log Rit

-

logRit^

=

aPOST

+

(3BIG

+

A[log kMt-

log kba-i], (14)using the interaction

POST*

BIG

asan

instrument for [logkbit—

logfe^t-i]-Under

theassump-tions in the previous subsection, A

=

eM

k»t+ k^)

e-^k

bt-{i

+

rht)kbt _Furthermore,

we

canuse theassumption

that the probabilitythat the granted limit changesis uncorrelated withthe interaction

BIG

*POST

toconstructan

additional instrument,which

will

make

use of the entire sample of firms to check for the robustness of our estimate: underthis assumption, the interactions

BIG

*POST

and

BIG

*POST

*C

(whereC

is adummy

variable equal tooneifthere is

any

changein the limit) canbe

usedtogether as instrumentsforthechangesin limit inthe

outcomes

equations (aftercontrolling forC

aswell asthe interactionsPOST *C

and

BIG*

C).4

Results

4.1

Credit

Expansion

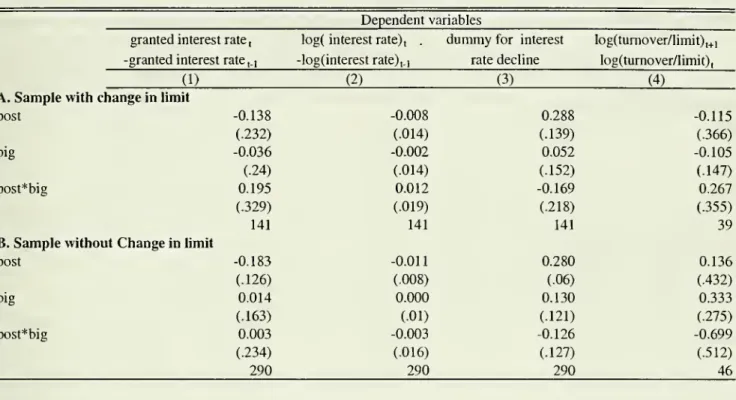

Table 5 presents the results of estimating equation (1) for several credit variables.17

We

startwith a variable indicating

whether

there isany

was any change

in the granted limit (columns(1)

and

(2)),and two

dummies

indicatingwhether

therewas an

increase or a decrease in thegranted limit. Consistent withthe evidence

we

discussed above, thereseem

tobe

absolutelyno

correlation

between

the probability to getany

change at all,any

increase orany

decrease,and

the interaction

BIG*POST.

Moreover, eventhemain

effectsofBIG

and

POST

areverysmall:none

ofthe variables in this regressionseem

to affectwhether

the filewas

granted a change in limit or not. This is trueboth

in the completesample

and

in the sample forwhich

we

havedata

on

the next year's sale (which is smaller sincewe

do

not use the last year of loan data).In the following columns,

we

look at loans receivedfrom

thisbank

(columns (5), (6)and

(7)),and

all working capital loans receivedby

thebanking

sector (columns (8)).As

the descriptiveevidencein table4 suggested, relativetosmall firms, loans

from

thisbank

to big firms increasedsignificantly faster after 1998

than

before: the coefficient of the interactionPOST

*BIG

is 0.08, in the complete sample,and

0.24 in thesample

forwhich

there isany

change in limit.Both

numbers

are significant. Incolumn

(6),we

restrict thesample

to observations that have achangein credit limit.

There was

asignificantdecline intheaverageenhancement

for small firms(the

dummy

forPOST

is negativeand

significant). Before the expansionofthepriority sector,small firmswere granted larger proportional

enhancement

than big firms (the coefficient ofthevariable

BIG

incolumn

(6) is -0.22, with a standarderror of0.079).The

gap

completelyclosedafter the reform (the coefficient of the interaction is actually slightly larger in absolute value than the coefficient ofthe variable

BIG).

Incolumn

(7),we

restrictthesample

to observationswhere

we

have dataon

the next year's sales : the coefficient is almostthesame

(0.23),and

stillsignificant. In

column

(8),we

look at thesum

ofall credit receivedfrom

thebanking

sector:The

coefficient is alittle larger (0.295).In

columns

(9)and

(10),we

lookinmore

detail atloans givenby

otherbanks: theprobability1

Thestandarderrorsin all regressions are adjustedforheteroskedaticityandclustering atthe firmandsector

levels.