Letters to the Editor

Prenatal diagnosis of Blake’s pouch cyst following

first-trimester observation of enlarged intracranial

translucency

A 27-year-old primigravida with no relevant medical his-tory was seen for her first prenatal appointment and first-trimester ultrasound scan at 12+ 1 weeks’ gestation. The crown–rump length (CRL) was 57.8 mm and the nuchal translucency thickness was 1.3 mm. First-trimester evaluation for combined risk did not indicate that the pregnancy was at high risk for aneuploidy, with a risk of 1/10 000.

Following the publications by Chaoui and Nico-laides et al.1 – 3, we systematically measure intracranial translucency (IT) at the first-trimester scan. For this fetus the IT was 3.5 mm (Figure 1), which is well above the 95th percentile for CRL according to established refer-ence ranges1. The patient was examined again at 23 and 32 weeks’ gestation. Examination of fetal anatomy at 23 weeks showed a large cyst connecting the fourth ventricle with the retrocerebellar space. The vermis was present, along with otherwise normal fetal morphology and biometry. We noted an enlargement of the fourth ventricle and an elevation of the lower part of the vermis, which was shifted away from the posterior part of the brainstem in an anticlockwise rotation (Figure 2). Using the methodology described by Guibaud and des Portes4 for the diagnosis of anomalies of the posterior fossa, we concluded that the fetus had a persistent Blake’s pouch (or Blake’s pouch cyst). At the time of writing the infant was 1 month old with normal findings on neurological exam-ination and on transfontanellar ultrasound examexam-ination performed 2 weeks after birth (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Ultrasound image (sagittal view) at12+ 1weeks’ gestation showing an enlarged intracranial translucency (*) of 3.5 mm (>95thpercentile).

Figure 2 (a) Sagittal ultrasound view of fetal brain at 23 weeks displaying enlargement of the fourth ventricle associated with elevation of the lower part of the vermis (V), with otherwise normal morphology and biometry. The vermis is shifted away from the pons with an anticlockwise rotation. The Blake’s pouch cyst (*) and its roof (arrowhead) are visible. (b) Axial ultrasound view of the posterior fossa displaying the ‘keyhole sign’ corresponding to the Blake’s pouch cyst (BPC). The lateral walls of the cyst are visible (arrows).

Our case of Blake’s pouch cyst is interesting because it complements cases in the literature of first-trimester cystic enlargement (paradoxically) resulting in a normal neonatal outcome5. In our case the IT was enlarged, well above the 95thpercentile for CRL1.

Following the description of IT, numerous studies have investigated the absence of this space as a screening marker for open spina bifida6,7. However, it should be noted that recently the sensitivity of this sign has been challenged by the report of a case in which there was a diagnosis of open spina bifida during the first trimester when the IT was present and of normal size8.

Figure 3 Transfontanellar ultrasound image (sagittal view) 2 weeks after birth showing normal position of the vermis, with full resolution of the Blake’s pouch cyst.

No previous publication has described enlargement of the IT. Our case is original in this regard because it sug-gests that enlargement of the IT can be used for the early detection of cystic malformations of the posterior fossa. This is a new sonographic marker that can be detected dur-ing the first-trimester scan when examindur-ing cerebral struc-tures. However, it should be emphasized that, although this finding was present in our case, abnormal structures visualized in the posterior fossa on first-trimester ultra-sound scan should not be automatically taken to indicate a pathological condition. Indeed, in our case the description of a normal brain after birth must relate to a delay in the fenestration of the Blake’s pouch into the perimedullary subarachnoid spaces9. When evaluating this aspect of fetal anatomy at first-trimester examination, the process of informing the parents regarding any abnormal findings and the need for appropriate monitoring must be carefully managed in order to avoid excessive anxiety or consider-ation of terminconsider-ation of pregnancy without due cause.

Normality of the posterior fossa, particularly the pres-ence of the cerebellar vermis, can be evaluated from 18 weeks’ gestation. However, whether the cerebellar vermis is complete or incomplete cannot always be deter-mined in early pregnancy.

A. Lafouge†, G. Gorincour‡, R. Desbriere§¶ and E. Quarello*§¶ †Cabinet de Gyn´ecologie et Obst´etrique,

Av Gambetta, Hy`eres, France;

‡Service de Radiop´ediatrie et d’Imagerie Pr´enatale,

H ˆopital la Timone, Marseille, France;

§Institut de M´edecine de la Reproduction,

Marseille, France;

¶Unit´e d’ ´Echographies Obst´etricales et de Diagnostic Pr´enatal, H ˆopital Saint Joseph, 25 Bd de Louvain; 13285 Marseille Cedex 08, France *Correspondence. (e-mail: e.quarello@me.com)

DOI: 10.1002/uog.11099

References

1. Chaoui R, Benoit B, Mitkowska-Wozniak H, Heling KS, Nico-laides KH. Assessment of intracranial translucency (IT) in the detection of spina bifida at the 11–13-week scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 249–252.

2. Chaoui R, Nicolaides KH. From nuchal translucency to intracra-nial translucency: towards the early detection of spina bifida. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010; 35: 133–138.

3. Chaoui R, Nicolaides KH. Detecting open spina bifida at the 11–13-week scan by assessing intracranial translucency and the posterior brain region: mid-sagittal or axial plane? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 38: 609–612.

4. Guibaud L, des Portes V. Plea for an anatomical approach to abnormalities of the posterior fossa in prenatal diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2006; 27: 477–481.

5. Bretelle F, Senat MV, Bernard JP, Hillion Y, Ville Y. First-trimester diagnosis of fetal arachnoid cyst: prenatal implication. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2002; 20: 400–402.

6. Chaoui R, Benoit B, Heling KS, Kagan KO, Pietzsch V, Sarut Lopez A, Tekesin I, Karl K. Prospective detection of open spina bifida at 11–13 weeks by assessing intracranial translucency and posterior brain. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 38: 722–726. 7. Egle D, Strobl I, Weiskopf-Schwendinger V, Grubinger E, Kraxner F, Mutz-Dehbalaie IS, Strasak A, Scheier M. Appearance of the fetal posterior fossa at11+ 3to13+ 6gestational weeks on transabdominal ultrasound examination. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 38: 620–624.

8. Arigita M, Martinez D, Nadal A, Borrell A. Spina bifida in a 13-week fetus with a normal intracranial translucency. Prenat Diagn 2011; 31: 1104–1105.

9. Robinson AJ, Goldstein R. The cisterna magna septa: vestigial remnants of Blake’s pouch and a potential new marker for normal development of the rhombencephalon. J Ultrasound Med 2007; 26: 83–95.

Rare combination of exomphalos with umbilical

cord teratoma

One third of infants with an omphalocele detected antenatally have associated anomalies1. Short-term mor-bidity in infants with a prenatal diagnosis of omphalocele is worse than that in cases detected at birth1. Congeni-tal umbilical cord teratomas are extremely rare, with 14 cases currently reported in the literature2 – 4. Four cases involved the combination of an umbilical cord teratoma and exomphalos3,5,6, of which two were terminated. We report the normal delivery of a fetus with an antenatally detected omphalocele and umbilical cord teratoma. The infant remained well following teratoma resection and exomphalos repair.

A non-smoking 34-year-old woman underwent an ini-tial examination at 7 weeks’ gestation at her local hospital with no abnormal findings. At 20 weeks’ gestation, a well-defined echogenic area within the cord that measured 2.1 × 2.6 × 2.8 cm was identified, with adjacent thickening of the umbilical cord. The patient was counseled about a suspected minor exomphalos, and invasive testing for karyotyping was offered and declined. At 28 weeks’ ges-tation the herniating structures measured 3.7 × 3.9 × 5.4 cm. In retrospect, acoustic shadows could be seen,

Figure 1 Ultrasound image at 28 weeks’ gestation showing exomphalos (E) and acoustic shadowing (AS), which was recognized retrospectively to be due to bone component of teratoma. F, fetus.

Figure 2 Postdelivery image demonstrating the relationship between teratoma (T), umbilical cord (UC) and exomphalos (E).

indicating bone within the umbilical cord mass (Figure 1). The body of the cord contained several large cysts. At 32+ 6 weeks’ gestation the cord hernia had a narrow base that measured 1.8 cm and a significant amount of bowel was contained within. At 38 + 5 weeks’ gestation labor was induced, resulting in normal vaginal delivery of a female infant weighing 3763 g. The neck of the umbilical cord hernia was narrow, prompting concern about the viability of bowel within the exomphalos. A tumor arising from the wall of the exomphalos was connected to the native small bowel (Figure 2). Complete resection necessitated excision of a small section of bowel and anastomosis.

Teratomas grow rapidly and, when associated with exomphalos and umbilical vessels, may lead to their rupture2. Rarely, they contain malignant tissue7; there-fore, serial tumor markers and imaging are required during the first few years of life. Despite the large volume of some umbilical cord teratomas, there has been only one

obstetric complication reported in which placental rup-ture led to fetal demise8. Known midline defects associated with umbilical teratomas include exomphalos, exstrophy of the urinary bladder9and myelomeningocele10.

Antenatal diagnosis of an umbilical cord tumor can be challenging in the presence of an exomphalos3. In the present case the initial ultrasound features may have sug-gested the presence of only a large exomphalos. However, acoustic shadowing that indicated bone (Figure 1) and narrowing of the umbilical cord between the mass and the abdominal wall were suggestive of a tumor.

D. J. B. Keene*†, E. Shawkat‡, J. Gillham‡ and R. J. Craigie† †Department of Paediatric Surgery, Royal Manchester

Children’s Hospital, Manchester, UK; ‡Department of Obstetrics, St Mary’s Hospital, Manchester, UK *Correspondence. (e-mail: dkeene@doctors.org.uk)

DOI: 10.1002/uog.11124

References

1. Cohen-Overbeek TE, Tong WH, Hatzmann TR, Wilms JF, Govaerts LC, Galjaard RJ, Steegers EA, Hop WC, Wladimiroff JW, Tibboel D. Omphalocele: comparison of outcome following prenatal or postnatal diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010; 36: 687–692.

2. Barker GM, Choudhury SR, Nicholls G, Whittle MR, Raafat F, Mitra SK. Fetiform teratoma arising from a tubular intestinal duplication. A probable cause of ruptured exomphalos. Pediatr Surg Int 1997; 12: 204–205.

3. Satge DC, Laumond MA, Desfarges F, Chenard MP. An umbil-ical cord teratoma in a 17-week-old fetus. Prenat Diagn 2001; 21: 284–288.

4. Del Sordo R, Fratini D, Cavaliere A. Teratoma of umbilical cord: a case report and literature review. Pathologica 2006; 98: 224–228 [Article in Italian].

5. Hargitai B, Csabai L, B ´an Z, Hetenyi I, Szucs I, Varga S, Papp Z. Rare case of exomphalos complicated with umbilical cord teratoma in a fetus with trisomy 13. Fetal Diagn Ther 2005; 20: 528–533.

6. Kreczy A, Alge A, Menardi G, Gassner I, Gschwendtner A, Mikuz G. Teratoma of the umbilical cord. Case report with review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1994; 118: 934–937.

7. Kreyberg L. A teratoma-like swelling in the umbilical cord possibly of acardius nature. J Pathol Bacteriol 1958; 75: 109–112.

8. Hartz PH, Van der Sar A. Teratoma of the liver in an infant. Am J Clin Pathol 1945; 15: 1959–1963.

9. Smith D, Majmudar B. Teratoma of the umbilical cord. Hum Pathol 1985; 16: 190–193.

10. Fujikura T, Wellings Sr. A teratoma-like mass on the placenta of a malformed infant. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1964; 89: 824–825.

Pitfalls in diagnosis of uterine artery

pseudoaneurysm after Cesarean section

A primigravid woman underwent emergency Cesarean section at 40 weeks of gestation because of cervical dys-tocia (dilation, 9 cm). Arterial bleeding from the left part of the uterine incision occurred during the procedure and

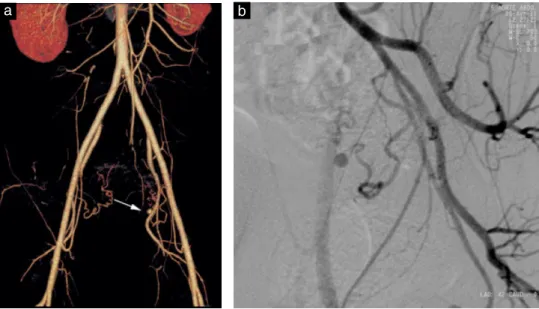

the artery was ligated immediately. The clinical course was uneventful and the woman was discharged on day 5. She then presented with abnormal uterine bleeding on day 35. Ultrasound examination revealed no retained products of conception and a normal myometrium. The bleeding stopped spontaneously and the patient received a blood transfusion (hemoglobin concentration, 6.7 g/dL). She was readmitted on day 49 due to massive uter-ine bleeding and hemorrhagic shock. Transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound examination, including color Doppler imaging, again revealed no retained products of conception and no lower uterine segment anomaly. The patient received another blood transfusion (hemoglobin concentration, 7.7 g/dL) and bleeding again stopped spon-taneously. Ultrasound examination was repeated by the same sonographer 10 h later when the hemodynamic status was normal. B-mode imaging revealed a 9-mm pulsatile cystic lesion in the left wall of the lower uterus (Figure 1a). Three-dimensional color Doppler showed tur-bulent blood flow communicating with the left uterine artery (Figure 1b), raising the suspicion of pseudoa-neurysm. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a sac perfused with contrast medium originat-ing from the ascendoriginat-ing branch of the left uterine artery (Figure 2a). Selective angiography confirmed the diagno-sis (Figure 2b) and the pseudoaneurysm was embolized using coils. The patient was discharged 2 days later and thereafter had normal menstrual periods with no recurrent abnormal bleeding.

A pseudoaneurysm is defined as a blood-filled cavity communicating with the arterial lumen due to deficiency of one or more layers of an arterial wall1. Spontaneous evolution leads to rupture. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm can occur after Cesarean section, especially when there is arterial injury during the procedure. Its rupture is a rare cause of postpartum hemorrhage, which can occur up to 3 months after Cesarean section1 – 3. It may be misdiagnosed as hypermenorrhea, retained products of

Figure 1 (a) B-mode ultrasound image showing a 9-mm pulsatile anechoic lesion in the left wall of the lower uterus. (b) Three-dimensional color Doppler showing turbulent blood flow

communicating with the left uterine artery, suggesting the presence of pseudoaneurysm (arrow).

conception or endometritis1. Spontaneous hemostasis can occur, reinforcing a misdiagnosis, and there can be a delay of up to 4 weeks before recurrence of bleeding1,4.

Figure 2 Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (a) and angiography (b) revealing a contrast-perfused sac originating from the ascending branch of the left uterine artery.

B-mode imaging usually shows in the wall of the lower uterus an anechoic lesion, which can be pulsatile. Duplex Doppler ultrasound shows a mosaic flow pattern due to the arterial flow swirling in different directions and at different velocities5,6. Sonographic features can disappear during active bleeding due to arterial pressure deflation and/or spastic communication, especially when the pseu-doaneurysm is small in diameter3,7. Contrast-enhanced CT can help to confirm the diagnosis as its sensitivity to detect arterial lesions is similar to that of angiography. Selective arterial embolization is the treatment of choice due to its high success rate (> 90%) and low compli-cation rate and because fertility can be preserved1,3,8. Our case illustrates two major pitfalls that may hinder the diagnosis of uterine artery pseudoaneurysm: sponta-neous hemostasis with delayed recurrence of bleeding and absence of typical ultrasound features at admission due to hemorrhagic shock and the small diameter of the lesion. Physicians facing delayed postpartum hemorrhage with no signs of retained products or endometritis should be aware of the possibility of uterine artery pseudoaneurysm. A second Doppler examination performed after correc-tion of hypovolemia could help to improve deteccorrec-tion of small-diameter uterine artery pseudoaneurysm.

P. Bouchet†, P. Chabrot‡, M. Fontarensky‡, A. Delabaere†§, M. Bonnin¶ and D. Gallot*†§ †CHU Clermont-Ferrand, CHU Estaing, Maternal Fetal

Medicine Unit, 1 place Lucie Aubrac, 63003 Clermont-Ferrand Cedex 1, France; ‡CHU Clermont-Ferrand, Hopital Gabriel Montpied, Department of Radiology, Clermont-Ferrand, France;

§GReD CNRS UMR6247, Clermont Universit´e, Facult´e

de M´edecine, Clermont-Ferrand, France; ¶CHU Clermont-Ferrand, CHU Estaing, Department of

Anesthesiology, Clermont-Ferrand, France *Correspondence. (e-mail: dgallot@chu-clermontferrand.fr)

DOI: 10.1002/uog.11123

References

1. Isono W, Tsutsumi R, Wada-Hiraike O, Fujimoto A, Osuga Y, Yano T, Taketani Y. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm after Cesarean section: case report and literature review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2010; 17: 687–691.

2. G ¨urses C, Yilmaz S, Biyikli S, Yildiz I, Sindel T. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm: unusual cause of delayed postpartum hemor-rhage. J Clin Ultrasound 2008; 36: 189–191.

3. Hayata E, Matsuda H, Furuya K. Rare cause of postpartum hem-orrhage caused by rupture of a uterine artery pseudoaneurysm 3 months after Cesarean delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010; 35: 620–623.

4. Descargues G, Douvrin F, Gravier A, Lemoine J, Marpeau L, Clavier E. False aneurysm of the uterine pedicle: an uncommon cause of post-partum haemorrhage after Cesarean section treated with selective arterial embolization. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2001; 97: 26–29.

5. Ball R, Picus D, Goyal R, Wilson D, Rader J. Ovarian artery pseudoaneurysm: diagnosis by Doppler sonography and treat-ment with transcatheter embolization. J Ultrasound Med 1995; 14: 250–252.

6. Kwon J, Kim G. Obstetric iatrogenic arterial injuries of the uterus: diagnosis with US and treatment with tran-scatheter arterial embolization. Radiographics 2002; 22: 35–46.

7. Bardou P, Orabona M, Vincelot A, Maubon A, Nathan N. Uterine artery false aneurysm after Cesarean delivery: an uncommon cause of post-partum haemorrhage. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2010; 29: 909–912.

8. Yi S, Ahn J. Secondary postpartum hemorrhage due to a pseudoaneurysm rupture at the fundal area of the uterus: a case treated with selective uterine arterial embolization. Fertil Steril 2010; 93: 2048–2049.