Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 81

The surrealist book as a cross-border space: The experimentations of Lise Deharme and Gisèle Prassinos

Andrea Oberhuber

Abstract: Following in the ‘revolutionary’ aesthetic footsteps of the post-World War One

avant-garde, many writers, painters, and photographers chose to partake in interartistic collaboration, thus defying the established boundaries between the different arts and their media and putting an end to the idea of the work of art as the ultimate production of a sole individual. Artistic contributions such as those by Magritte and Man Ray for Éluard, or those by Masson for Aragon, Bataille and Leiris, are now considered classics of the surrealist book. Yet the collaboration between women writers and artists of the surrealist movement remains to this day largely unknown, notwithstanding their recognized intermedial practice. Most would combine two artistic practices in their works: writing and film (Belen a.k.a Nelly Kaplan), writing and photography (Claude Cahun), writing and painting (Leonora Carrington), or writing and drawing (Unica Zürn). In my analysis of the avant-garde book-object, I examine two examples of rethinking the book as a space of text/image experimentation in the framework of surrealist aesthetics. The first is Lise Deharme, who sees the book as a space for collaboration and intermedial dialogue, the second Gisèle Prassinos, who views the book-object as a space for playful metamorphosis. These two writers and artists upset any previous understanding of the ‘illustrated book’ and come far closer to what is referred to today as the livre d’artiste.

Résumé: Fidèle à l’esthétique « révolutionnaire » propre aux avant-gardes de

l’entre-deux-guerres, bon nombre d’auteurs, de peintres et de photographes se sont lancés dans l’aventure de la collaboration interartistique défiant par là les frontières entre les arts et les genres, mettant à mort l’idée de l’œuvre d’art comme l’aboutissement d’une démarche individuelle. Si les illustrations de Max Ernst pour Crevel, Tzara ou Péret, de Magritte et Man Ray pour Éluard, de Masson pour Aragon, Bataille et Leiris ou de Miro pour Breton font aujourd’hui partie des grands classiques du livre dit surréaliste, la collaboration entre femmes auteurs et artistes du mouvement surréaliste semblent encore aujourd’hui moins connue. Ces créatrices surréalistes faisaient pourtant preuve le plus souvent d’une véritable praxis intermédiale, c’est-à-dire que, pour la plupart, elles investissaient d’office deux arts et leur médium respectif : l’écriture et le

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 82

cinéma (Belen alias Nelly Kaplan), l’écriture et la photographie (Claude Cahun), l’écriture et la peinture (Leonora Carrington) ou l’écriture et le dessin (Unica Zürn).

Les deux cas de figure que je me propose d’examiner de plus près sont représentatifs d’une nouvelle conception de l’espace livresque, telle que mise en œuvre par l’esthétique surréaliste : je m’intéresserai d’abord au livre comme espace de collaboration et de dialogue intermédial chez Lise Deharme, ensuite au livre-objet comme possible lieu de métamorphose ludique chez Gisèle Prassinos. Les deux auteures font éclater les limites anciennement assignées au « livre illustré » se rapprochant davantage de ce que l’on désigne aujourd’hui comme « livre d’artiste ». M’inspirant des recherches menées par Henri Béhar, Renée Riese Hubert, Lothar Lang et Montserrat Prudon dans le contexte du livre dit surréaliste, je m’interrogerai sur les rapports de collusion et de collision entre le texte et l’image, de même que sur le type de lecture exigé par le nouvel objet livre. Mon analyse prendra appui sur Le Cœur de Pic, Le Poids d’un oiseau et Brelin le frou ou le Portrait de famille.

Key words: Surrealist Book; interartistic collaboration; collaboration between women writers

and artists; text/image experimentation; intermedial dialogue; Lise Deharme; Gisèle Prassinos.

With the research in surrealism and literary culture conducted by Henri Béhar (1982), François Chapon (1987), Renée Riese Hubert (1988), Lothar Lang (1993), Johanna Drucker (1995), and Yves Peyré (2001),1 among others, we are now quite familiar with the importance of the collaboration between writers and visual artists in their development of a ‘cross-border’ aesthetic. Inspired by the surrealist concept of ars combinatoria, this collaboration between artists has evolved into an array of what are now called ‘livres d’artiste’.2

1 Henri Béhar, ‘Le Livre surréaliste’, Mélusine, 4 (1981), ed. by Henri Béhar; François Chapon, Le peintre et le

livre: l’âge d’or du livre illustré en France, 1870-1970 (Paris: Flammarion, 1987); Renée Riese Hubert, Surrealism and the Book (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988); Lothar Lang, Surrealismus und Buchkunst (Leipzig:

Ed. Leipzig, 1993); Johanna Drucker, The Century of Artists’ Books (New York: Granary Books ,1995); Yves Peyré,

Peinture et poésie: le dialogue par le livre, 1874-2000 (Paris: Gallimard, 2001).

For instance, one

2 See Elza Adamowicz, ‘État présent: The Livre d’artiste in Twentieth-Century France’, French Studies, LXIII. 2

(2009), 189-198. For further discussion on the artist book, see Anne Moeglin-Delcroix, Esthétique du livre d’artiste:

1960-1980 (Paris: Jean Michel Place, 1997); Peinture et écriture 2. Le livre d’artiste, ed. by Montserrat Prudon

1874-Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 83 might think of Max Ernst’s visual contributions to the works of Crevel, Tzara, or Péret, in the so-called ‘surrealist’ books, or of the illustrations of Magritte and Man Ray for Éluard, along with those of Masson for Aragon, Bataille, and Leiris. Less well-known is the development of a new type of ‘book’ put together by surrealist avant-garde women writers and artists that went beyond traditional practices of scrapbooking, binding, and illustration, or other a posteriori additions to literary production, like the cover page or frontispiece. Many of these 2nd and 3rd generation avant-garde artists, while actively rewriting or redrawing the topoï of surrealism, fully utilized the space of the book to create protean works. These books, or rather, these book objects, are the result of collaborations between women and men, or – as in our study – of collaborations between two women: poets and painters, writers and photographers or illustrators. These forms of interartistic collaboration and dialogue of at least two medias are governed by a creative principle that establishes dynamic relationships between writing and iconography. According to the cross-border aesthetics of the so-called historical Avant-Gardes,3 the artists appropriate the book as an object, offering an idea of the work of art that transcends the boundaries between different artistic genres and their supporting media. While exploring such variables as the ‘feminine’ and the ‘intermedial’, these artists situate themselves in opposition to the conventional figures of the ‘child-woman’, the ‘muse’, or the ‘collaborator of recognized poets, painters, and photographers’, a far cry then from Katherine Conley’s Automatic Woman.4 Emblematic figures of this type of surrealist creation — Claude Cahun, Lise Deharme, Leonor Fini, Bona de Mandiargues, Unica Zürn, among many others — conceive of the book as an entity in which the two artifacts are inseparable, their iconographic and textual practices ensuring the continuance of the movement’s poetic and aesthetic values.5

In the context of a reflection on the ‘book’ object as a space of innovation and experimentation, I discuss two cases that I deem representative of modes of rethinking the new

1999, ed. by Jean Khalfa (Cambridge: Black Apollo Press, 2001); and Isabelle Jameson, ‘Histoire du livre d’artiste’, Cursus, 9. 1 (2005).

3 I refer to Peter Bürger’s terminology of Futurism, Dada and Surrealism as ‘historical Avant-Gardes’ and to the

characteristics he proposes in the chapter: « The Avant-Gardiste Work of Art », in Theory of the Avant-garde, translated from German by Michael Shaw, Minneapolis, University of Minneapolis Press, 1992 [1974], p. 55-82. See also Renée Riese Hubert Surrealism and the Book, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1988, p. 54-83.

4 See Katharine Conley, Automatic Woman: The Representation of Woman in Surrealism (Lincoln-London:

University of Nebraska Press, 1996).

5

See Andrea Oberhuber, ‘Écriture et image de soi dans Le Livre de Leonor Fini’, Dalhousie French Studies, 89 (winter 2009), 45-46.

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 84

book object proposed by surrealist aesthetics. On the one hand, with Lise Deharme, Claude Cahun, and Leonor Fini, the book opens up a space for collaboration, exchange and dialogue. On the other hand, with Gisèle Prassinos, the book becomes a stage for games of metamorphosis and mad humour. I am interested in the notion of the boundary between the visual and the textual and between words and images, with respect to their degree of ‘coincidence’, which may be ‘complete’ (like in the traditional forms of illustrated books or “picture books”), ‘partial’ (common for the hybrid text/image-forms in the 20th century), or ‘hidden’ (as occasionally in artist’s books).6

By way of three types of collaboration between artists, I want to show that text and image tend to preserve a balance that might vary depending on the specific example, but that is continuously in favour of the sense which is co-created where words and images intersect: this sense is sometimes obvious, in particular when text and image are facing each other on the double page to open a space of convergence, and sometimes it needs to be reconstituted by the reader-viewer’s imaginativeness. Likewise, it will be demonstrated that the fragmentation of pages to be read and pages to be viewed within the book-space goes beyond the idea of books with illustrations added in retrospect. These book challenge the mimetic relation between text and image, asking for a reader who is able to break with traditional linear reading habits and ready to dive into this new space of reading and viewing, as image and text question each other. Underlying this analysis are the following questions: What iconographic and textual ‘regime’ governs the books brought forth by these authors and artists? And, in the wake of this interrogation, what new stance must the reader take before a book that forgoes bi-dimensionality to manifest itself rather as a reconfigured space of reading and looking?

The book as space for collaboration and intermedial dialogue

In 1937, Lise Deharme published a children’s book entitled Le Cœur de Pic, to which Éluard referred, in his preface, as a ‘livre d’images, [qui] a l’âge que vous voulez’7

6 Aron Kibédi Varga, ‘Entre le texte et l’image: une pragmatique des limites’, Text and Visuality: Word & Image

Interaction 3, ed. by Martin Heusser and others (Amsterdam-Atlanta: Rodopi, 1999), 77-92 (80-89).

. In this collection, Deharme, well-known in the surrealist milieu — the writer and poet was, after all, a regular at Parisian salons and passed for a surrealist muse — , brought together a series of poems devoted

7

Paul Éluard, ‘Préface’ in Lise Deharme, Le Cœur de Pic, illustré de vingt photographies par Claude Cahun (Paris: José Corti, 1937; Éditions MeMo 2004). Hereafter CP (does not have page numbers).

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 85

to the wonders of flora and fauna: here is a ‘Belle de nuit’, for whom Jehan du Seigneur ‘donnerai[t] [s]a vie’, an ‘Immortelle’ who may only die of regret, azaleas in ‘un beau petit panier’, a ‘capucine’ who cried tears of ‘glycine / pour la mort du papillon blanc / son amant’. Among these peaceful landscapes, these quickly wilting flowers and stolid animals in the meadows, Pic appears, intent on sharing his troubles with the reader (‘Les ennuis de Pic’). Rather than ‘jouer / avec les petites filles dans les hôtels’, he asks ‘qu’on lui amène / le Diable’, or that we lend him a book of matches for a moment — ‘Ah quelle belle flambée / mes enfants’, cries the little hero with green coat and Basque beret. Pic’s appearance shifts the poetic mood squarely into the marvellous and irrational world of childhood. The reader now, and retroactively, associates the narrative voice with the mischievous Pic, who tells us that from a fallen feather, a ‘plumier’ will grow, that ‘trois petits souliers’ can go up the stairs, on their own, and that if the nerve of his tooth taunts him, Pic shall take up a ‘petit bâton pointu / pan’, and the nerve will turn into a ‘petit serpent / mort’.

From the outset, the book’s cover tells the reader that it is the collaborative work of two artists, since the 32 rather unusual poems are expressly ‘illustré[s] de vingt photographies par Claude Cahun’ (fig. 1). Pic’s surreal universe, steeped in invisible adventures, is a perfect match for the dreamlike imagination Cahun had evinced in her earlier short texts, such as Carnaval en chambre and, especially, the photomontages she had incorporated into Aveux non avenus.8 Approached by Deharme, Claude Cahun, a writer and photographer, created a new type of image that François Leperlier called ‘photographic tableau’, to do justice both to its theatricality (staged objects) and to its pictorial characteristics (composited form).9

8 For further details, see François Leperlier, Claude Cahun: l’exotisme intérieur (Paris: Fayard, 2006: 357-360) and

Andrea Oberhuber, ‘“J’ai la manie de l’exception”: illisibilité, hybridation et réflexions génériques dans Aveux non

avenus de Claude Cahun’ in Ricard Ripoll, ed., Stratégies de l’illisible (Perpignan: Presses universitaires de

Perpignan, 2005: 75-87).

At first glance, these twenty photographs, as they are unequivocally characterized on the cover page, look like photomontages. The colour photograph chosen for the book’s cover is a perfect example. Like each of the other images in the book, it suggests a specific work of collage and montage, this one featuring Pic, the hero with a big tin-box heart, standing in front of seven playing cards, while an eighth — the Queen of Hearts — is mounted like a flag or banner on a long wooden rod. The other images of the book, in black and white, portray a variety of objects, dolls, and various

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 86

children’s figurines, which, found, manufactured, redirected, are placed in either a natural or domestic setting. So eclectic and surprising is the staging of these strange worlds — with anthropomorphic eggs placed under a bird’s cage (plate III), a deer juxtaposed with a thimble, a hedgehog with a pair of scissors (plate IV) — one might well take it for photomontage. As with a theatre set, Cahun places this clutter of objects, flowers, little animals, statues, shoes, fabric, and figurines upon a single, delimited stage, as if she were attempting to capture particular moments of an odd spectacle. Midway between snapshot and surrealist photomontage, these trompe-l’œil images create a false sense of ‘reality’, precisely because of their resemblance to a theatre stage. They give palpable dimension to the ‘petit théâtre d’enfance [. . .], précieux et intimiste’10 that is staged in Deharme’s poems. As such, each theatrical simulation would seem to correspond to a moment in life as seen through the eyes of the miniature characters, of which Pic is the principal hero. In resonance with each of the thirty-two sad and somewhat malicious poems, these photographic tableaux bring to this children’s book not only a certain symbolic value, but also, like childhood itself, a highly dramatic element.

Fig. 1 Cover (Lise Deharme, Le C¦ur de Pic, illustré de vingt photographies par Claude Cahun, Paris: José Corti, 1937; Éditions MeMo 2004).

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 87

The collaborative work in Le Cœur de Pic results in a four-handed oeuvre that enables a dialogue between the poetic word and the photographic image: the collaboration is even and complementary, the visual and the textual in such a state of ‘complete coincidence’ as to become inseparable, echoing each other, at times, in the most casual manner.11

Le Cœur de Pic is a precious, truly surrealist book-object, as evinced by the specular conception of the textual and the visual, which enables variations and discrepancies between poem and photograph nonetheless, by the dreamworld conjured on each double-page spread, by the semblance of theatrical spectacle manifest when reader-spectators hold the book up vertically before their eyes, and by the finely made format and binding.

Text and image fit together as if made for one another. The work as a whole is witness to a single creative force, as if, after Deharme’s numerous novels and Cahun’s many aesthetic experimentations, the moment had come to combine word and image in a single, indefinite space-time, at once the time of recreation and the spatial re-creation of the child’s universe. Such, indeed, is suggested by the illustration at the centre of the book, where a doll’s bed covered with a white veil and plants accompanies ‘La débonnaire Saponnaire’ and ‘La Centaurée déprimée’ (plate XIII).

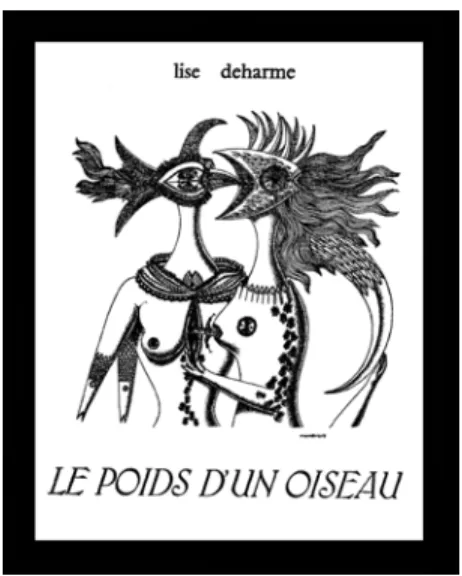

Almost twenty years later, Deharme embarks on another interartistic collaboration. This time she calls upon painter and illustrator Leonor Fini to illustrate the cover and plates that are to accompany Deharme’s poetic prose. Inspired still by fairytales and fantastic stories, Deharme’s Le Poids d’un oiseau12

11 Having engaged in several studies of Cahun’s inclination to intermingle text and image in the same work of art —

often the outcome of an interartistic collaboration —, I point the reader to the following articles: Andrea Oberhuber, ‘Aimer, s’aimer à s’y perdre? Les jeux spéculaires de Cahun-Moore’, Intermédialités, 4 (fall 2004), 87-114; ‘Pour une esthétique de l’entre-deux: à propos des stratégies intermédiales dans l’œuvre de Claude Cahun’, Narratologie, 6 (2005), 343-364; and ‘Cahun, Moore, Deharme and the Surrealist Book’, History of Photography, 31. 1 (spring 2007), 40-56.

is made up of several unrelated micro-narratives that resolve nonetheless into a reflection on time and the finiteness of the human condition. Disappearance and spectres are recurring themes in the collection, and the narrator’s voice often seems to come from beyond the grave. As with many of Deharme’s works, the narrative centres on female figures and their hybrid identity, particularly in their elective affinities with the plant kingdom. The writing

12

Lise Deharme, Le Poids d’un oiseau, illustrations by Leonor Fini (Paris: Éric Losfeld, 1955). Hereafter PO (not paginated).

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 88

resembles an automatic writing practice: the tone is often comical or parodic, especially in relation to traditional poetic genres and in its playful rapport with language.13

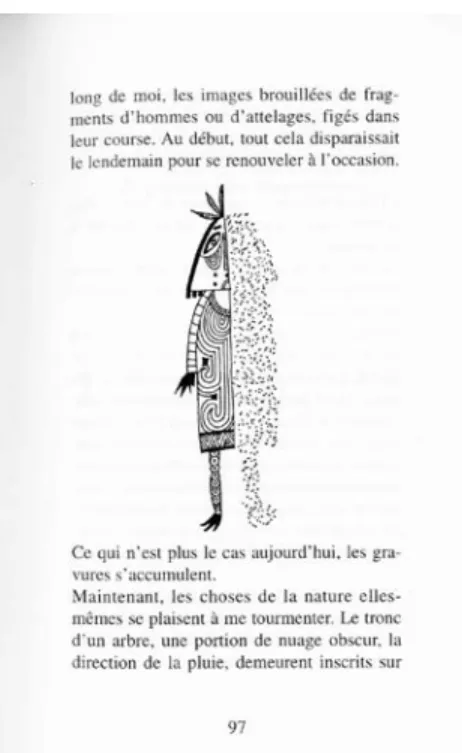

Unlike the previous example, Fini’s art-deco, black and white drawings seem confined to an illustrative function, the dialogue between word and image following a one-to-one relationship. Fini’s characteristically febrile, sinewy drawings refer explicitly to their respective text, which they open or close as they fleetingly appear to the reader-spectator. Indeed, the five drawings of women, all veiled, seem to suddenly appear in the text like spectral figures, as if to surprise the reader and to interrupt the reading for a moment.

The coincidence between text and image remains ‘partial’ here, the dialogue fragmentary. Without a unifying narrative, the collection is lent formal unity by the five illustrations portraying the same woman in different postures. Upon closer inspection, the work as a whole does appear to hold, as a unity in tone and style runs through both the stories and Fini’s illustrations. A particular passage in ‘C’est la fin d’un beau jour’ enables us to identify the inspiration for the drawings: ‘[Les] fantômes sentent la poussière et parfois même un peu le parfum. Ils portent des voiles, des fleurs, des bijoux et des souliers de bal d’une couleur exquise absolument impossible à trouver dans le commerce courant.’ (PO, n.p.) Indeed, like ghosts, the women in the drawings seem to run through the book and vanish upon its ending. Despite the rather conventional rapport between text and image, an aesthetic more suggestive of illustration than of a surrealist book, what grabs the reader’s attention is Le Poids d’un oiseau’s cover (fig. 2). Serving as a gateway to the work, it reveals ‘hidden’ coincidences between the stories and the illustrations.

13 The writer enjoys associating words according to their phonetic resemblance, thus creating new, unexpected

meanings (see for instance in ‘La partie de cartes’ (PO n.p.). For further details on Deharme’s use of humour and irony, see Marie-Claude Barnet, La femme cent sexes ou les genres communicants: Deharme, Mansour, Prassinos (Bern: Peter Lang, 1998), pp. 150-153. It is rather surprising that there is so little in-depth analysis of Deharme’s works. Nevertheless, besides Barnet’s aforementioned study and an article entitled ‘To Lise Deharme’s Lighthouse: “Le Phare de Neuilly”, a Forgotten Surrealist Review’, French Studies, 57. 3 (2003), 323-334, worth mentioning is a special issue of Les Cahiers Bleus (no. 19, fall-winter 1980) devoted to Lise Deharme, which includes tributes from contemporaries, drawings (including two of Fini’s), and letter facsimiles.

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 89

Fig. 2 Cover (Lise Deharme, Le Poids d¹un oiseau, illustrations by Leonor Fini, Paris: Éric Losfeld, 1955).

Everything here conspires to draw the reader’s gaze, transformed into that of a spectator, even a voyeur, into the depths of the etching, as he or she, intrigued, attempts to unravel the image of the two fish-bird-headed women engulfing each other. The woman on the left is plunging her beak into the wide-open beak of her hybrid counterpart, who, in symbiotic turn, is inserting her dagger-equipped breast into a small vulva-shaped gap cut into the first woman’s chest. Insects (flies?) attempt to penetrate the body as well, while another colony of insects marches up the arm of the woman on the right, towards her neck. Fini’s exquisitely detailed etching foreshadows Deharme’s odd universe of strange birds: a ghost that haunts the Château de Versailles; a woman struck by lightning; a maid killed by a falling elevator; a young girl buried alive by the sisters of a convent; a queen who kills wolves and peasants and then prepares them for dinner ‘avec des petits lardons d’enfants’, as in the ironic tale ‘Ah! Mon beau château!’ (PO, n.p.). The surrealistic dimension of the image echoes the unbridled imagination of these micro-narratives, their prevailing spectral universe and images of death.

Le Poids d’un oiseau is an idle book, to be read as entertainment, a time for a breather and letting one’s thoughts escape distinctions of real and unreal and take flight. The very detached tone of these fifteen ‘tales for adults’, their dark humour, and Deharme’s parodic writing all invite the reader to act like the flimsy characters in the etchings: to alight for a moment, to look and see, and then to disappear, in the expectation of a book to come, of ‘des jours meilleurs’, as the narrator puts it at the end of ‘La Dame à la harpe’ (PO n.p.). Like the fleeting women figures, the ghostly characters are light as feathers, have no gravity at all. As one

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 90

looks at the texts and images more attentively, relating them to the cover image, the initial discrepancy between the literal and the figural begins to fade away. Should reader-spectators choose to let themselves enter this wonderland, they may well be submerged in this fleeting, dual universe of the in-between. In this liminal space of the book, the walls erected between the two regimes of representation may fall, inviting us to a cross-reading that continues long after we’ve reached the end of the story.

The book, a playful space of metamorphosis

Contrary to most surrealist artists whose practice was truly intermedial, Gisèle Prassinos, the child-woman immortalized by Man Ray during her reading of her poem ‘La sauterelle arthritique’ for the group of surrealists, comes to the marriage of writing and visual arts much later in her career.14 In Brelin le frou ou le Portrait de famille15

Brelin le frou was published by Belfond in 1975 (fig. 3 and fig. 4)

, Prassinos explores the book as an object and a space for iconographic and textual play and experimentation for the first time. A reader familiar with such previous work as Une demande en mariage (1935), Le temps n’est rien (1958), Les Mots endormis (1967), discovers a new dimension of the author as an avid illustrator and tapestry artist.

16

14

Prassinos’ poetic oeuvre has elicited more critical attention than Deharme’s. See in particular Annie Richard, ‘Le discours féminin dans Le Grand Repas de Gisèle Prassinos’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Université Paris III, 1980), ead., Le monde suspendu de Gisele Prassinos (Aigues-Vives: HB Éditions, 1997) and ead., La Bible surréaliste de

Gisèle Prassinos: les tentures bibliques (Bierges : Éditions Mols, 2004). Also consider the following: Madeleine

Cottenet-Hage, Gisèle Prassinos ou le désir du lieu intime (Paris: Jean-Michel Place, 1988); José Ensch and Rosemarie Kiefer, À l’écoute de Gisèle Prassinos : une voix grecque (Sherbrooke: Editions Naaman, 1986); Jacqueline Chénieux-Gendron, ‘Gisèle Prassinos disqualifiée disqualifiante’, Obliques, 14-15 (1977), 207-215; Marie-Claire Barnet, ‘“Exquises esquisses” by Gisèle and Mario Prassinos: the Craftswoman, the Writer and Her Brother’ in On Verbal / Visual Representation: Word & Image Interactions 4, ed. by Martin Heusser and others (Amsterdam / New York: Rodopi, 2005), 193-206.

, but the line drawings that accompany it, originally intended for colour tapestry, were done in 1966-1967. This work is fundamental to Prassinos’ sense of craftwork and personal mythology, here constructed, analyzed, and commented upon in a more entertaining manner than in her auto(bio)graphy, Le temps n’est rien. Brelin, the protagonist and anti-hero of this family portrait

15 Gisèle Prassinos, Brelin le frou ou le Portrait de famille (Paris: Belfond, 1975). Hereafter BF.

16 I wish to express my gratitude to Gisèle Prassinos who offerd me full permission to publish the images of Brelin

le frou. I am also very grateful to Annie Richard, specialist of Prassinos’ work, for acting as a messenger between

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 91

— ‘enfant débile mental, castré à l’âge de seize ans par ses parents honteux des nombreux esclandres qu’il avait provoqués par son exhibitionnisme’ (BF 19)—, functions as a double, an alter ego for Prassinos, who is seeking a place within a family of seven children. In the preface, the narrator, G.P., takes the reader to the faraway land of Frubie-Ost. This imaginary realm is made up of words and images that leave readers spellbound. The narrator recalls the legend, which, in the ‘quotidien de la capitale frubienne-ost’ (BF 12), accompanies the aforementioned painting: ‘Cet intéressant tableau, intitulé LE PORTRAIT DE FAMILLE et composé de morceaux d’étoffes cousus sur de la toile, est, parmi beaucoup d’autres, l’ouvrage d’un frou17, récemment décédé dans un rbi18 où il vivait seul depuis vingt-quatre ans.’ (BF 11-12)

Fig. 3 Cover (Gisèle Prassinos, Brelin le frou ou le Portrait de famille, Paris: Belfond, 1975). Fig. 4 Gisèle Prassinos, Brelin le frou ou le Portrait de famille, p. 18-19.19

The only colour illustration in Brelin le frou is the one on the cover, a ‘tapestry’ that is also the fulcrum underpinning the story of physicist Berge Bergsky and his family, including Brelin, the elder brother (fig. 5). At once playful and faery-like, the image portrays the seven protagonists of the narrative, their arms extended, as if saluting the reader’s arrival. The odd characters, all geometric in form — their bodies square or rectangular, their hats, noses, mouths and ears

17 Prassinos’s note: ‘1. Frou: Vieillard entre 90 et 95 ans. De 95 à 100 ans, on porte le nom de bem en Frubie-Ost.’ 18 Idem: ‘2. Rbi: Cabane sommaire construite par un paysan frubien.’

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 92

triangular, their eyes round —, are set in a variety of starred, oval- or square-patterned fabric. This welcoming image reveals a unified, closely-knit family, each member counting upon the whole to stand firm and straight. Brelin, dressed in pink and red, is symmetrically opposed to his father, the patriarch, set in light and dark blue. Despite this apparent balance, the attentive reader will note the distance the artist keeps between herself and the dominant grouping of the father and scholar son.

Fig. 5 Gisèle Prassinos, Le Portrait de famille, tapestry (reproduced in Annie Richard, Le monde suspendu de Gisèle Prassinos,

Aigues-Vives, HB Éditions, 1997, p. 71).

The image at the end of this unusual ‘family novel’, titled ‘Portrait idéal de l’artiste’, is altogether different. It soon becomes clear not only that Brelin — like all the book’s protagonists — is a little ‘f(r)ou’ (fig. 6), but that he transcends his state of marginal artist through an avid pursuit of artistic perfection. He is shown facing the reader, his wide, round eyes staring fixedly; he resembles some mythical, even royal figure, with numerous ornaments pinned to his garments (including a tenfold representation of the masculine sex20

20 Barnet, in her La femme cent sexes (67-69), discusses the notion of Eros in Brelin le frou. See also Cottenet-Hage,

‘Humour, sexe et fantaisie: Brelin le frou ou le Portrait de famille de Gisèle Prassinos’ in La femme s'entête: la part

du féminin dans le surréalisme, ed. by Georgiana M. M. Colvile and Katharine Conley (Paris: Lachenal & Ritter,

1998), 172-185 (specifically pp. 177-183).

), a crown poised on his head, and several layers of robes, giving him the austere look of a monarch. Though Brelin appears rather melancholic, due to his lack of a mouth in the image, one nevertheless feels a sense of composure and presence. The face resembles a mortuary mask, stricken black and white, and

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 93

participates in the sense of dread and tragedy that emanates from the painting. Brelin undoubtedly remains a character apart, even within this self-representation in which he consecrates himself as an artist.

Fig. 6 Gisèle Prassinos, Portrait idéal de l¹artiste, tapestry reproduced in Annie Richard, Le monde suspendu de Gisèle Prassinos,

Aigues-Vives, HB Éditions, 1997, p. 72).

Words can spring from images, snapshots one finds in a box. Prassinos invented her patchwork biography of Berge Bergsky, the ‘inoubliable physicien’ (BF 13), and of Brelin le frou from whole cloth, as it were. Brought together separately in a commemorative edition, the Brelin series, which had already been exhibited, are here endowed with a narrative.21 The twelve chapters, like so many ekphrases,22

21 See Richard, Le monde suspendu de Gisèle Prassinos, 63-65.

give a vivid account of the family configurations, of Frubian lifestyle, and of the art of this ‘[p]ays d’Europe situé entre la Bronze septentrionale et l’Hure orientale’ (BF 12, note 3). The line drawings, which the narrator creates from the Brelin tapestries, maintain an integral relationship with the twelve stories: they literally generate words

22

There are several instances where the text on the right-hand side provides a detailed description of the drawing on the left (see, for instance, on pages 19, 45, 53, and 95).

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 94

(fig. 7). What Annie Richard observes regarding Prassinos’s biblical tapestries may also be applied to the artist’s iconographic and textual practice in Brelin le frou: ‘Texte et image sont étroitement imbriqués [. . .]. Les limites s’effacent [. . .] entre le verbal et le visuel [. . .]. Nous sommes en plein processus poétique.’23

Fig. 7 Gisèle Prassinos, Brelin le frou ou le Portrait de famille, p. 144-145.

In short, Brelin le frou is what I would call a ‘diverted surrealist book,’ in that it is both distorted and masked. It is ‘distorted’ because Prassinos hijacks a major principles of interartistic collaboration, thus revealing a dual image of herself as not only the well-established author but also a creative subject who, indirectly, assumes her new-found role as an artist. And it is ‘masked’ because this other self produces its tapestry under the guise of the mad artist.24 The book therefore becomes a (self-)fictional space in which such a metamorphosis can take place, thanks to the dual strategy of distortion and masking. Brelin le frou functions like a ‘darkroom (camera obscura)’, conducive to lighting an ‘intérieur protégé’, an ‘espace intime de l’histoire des mots et des formes du poète’.25

23

Richard, Le monde suspendu de Gisèle Prassinos, 76-78.

Intermingled with a family’s history, this particular space enables the existence of a whole country and its part-real, part-fictional characters, which

24 Cottenet-Hage (‘Humour, sexe et fantaisie’, p. 173) argues a similar idea, pointing out that the writer ‘hides

behind the mask of a humorous fiction, thus maintaining a secure distance between a confession and a delightful fantasy’.

25

Marina Catzaras, ‘Poésie du corps ou corps de la poésie: close up sur écriture et peinture’, in Peinture et écriture

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 95

reader-spectators discover through words and through drawings traced in black and white from colourful tapestries. The word-image, then, carries meaning and poetry, but it bears a secret as well, of something hidden, that one may uncover if only one takes the time to truly look at the pictures in relation to their assigned texts, and vice versa.

Towards a new form of the book

The three examples I have discussed here reveal possibilities and avenues for experimentation with the book, enriched by collaborative practice or by innovations around word and image within the concept of the ‘book object’. While Lise Deharme’s writings preceded the image, Cahun and Fini being called upon to contribute their visual art to Le Cœur de Pic and Le Poids d’un oiseau, with Prassinos, in Brelin le frou, the writing draws its narrative inspiration from images found by chance.26 Faced with the narrative-framed illustrations, it is up to the reader-spectator to seek works that gladly combine the poetry of images with the sometimes hidden meaning of the word. New forms of the book therefore seem to be emerging from the fragmentation of space — that between the pages reserved for words and those taken up by images. This fragmentation of book space may take on different forms and transgress the limits of the textual and the visual in different ways. First, two artists may favour a balance between words and images, allowing for interchange between the two entities (Deharme and Cahun). Second, the book’s spatial and temporal fragmentation may extend the idea of the illustrated book, with variations, while providing the images a certain autonomy (Deharme and Fini). And third, a poetic book object may enable word and image to wholly participate in the creation of a parallel world – half fictionalized half autobiographical – where the boundaries between reality and dream, (personal) history and illusion seem to be abolished; sometimes, as with Prassinos, these books offer the possibility of splitting the author’s identity into a writing and a visual artist’s (fig. 8).

26 In the ‘Preface’, in a sort of contract with the reader, the narrator, G.P., explains that during a trip to Frubie-Ost

she chanced to acquire the tapestries that Brelin had made, based on family photos he had found in a box (BF 11-15).

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 96

Fig. 8 Gisèle Prassinos, ³La gomme², Mon coeur les écoute, 1982, Aigues-Vives, HB Éditions, 1998, p. 97.

Whether the two heterogeneous systems of representation collide or collude, the fact that the image and the text meet within the book opens up the possibility of between-spaces. This play of varying coincidence enables new reading practices and prompts formal examination of the continuum between the nineteenth-century illustrated book and the book considered as a ‘surrealist-object’, whose fine craftsmanship and limited edition begs to be exhibited.27 These new books ask of readers that they change their reading practices, and adopt a plural form of perceptual reading.28

scour the book, sometime through physical handling, in a frequent to and fro between text and image, in order to detect hidden meanings within the page, in the icono-textual interstices. Thus, as open-eyed and curious readers, may we participate in the verbal-visual alchemy.

One must forgo the principle of linear reading, and, as a reader-spectator,

27

We know the importance the surrealist movement accorded the found object, to transform it, through a dual process of decontextualization and recontextualization, into a work of art. See the excellent exhibition catalogue,

Surreal Things: Surrealism and Design (London: Victoria & Albert Publications, 2007).

28Anne-Marie Vetter refers to a process involving a ‘double reading’, perhaps even a ‘multiple reading’ of the livre

d’artiste (see ‘Quel lecteur pour le livre d’artiste?’, in Peinture et écriture 2. Le livre d’artiste, ed. by Montserrat

Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No 3 (2011) 97

Andrea Oberhuber est Professeure au Département d'études françaises de l'Université de Montréal depuis juin 2001. Depuis plusieurs années, son intérêt se porte particulièrement sur la littérature et les autres arts. Les approches théoriques qu'elle privilégie se laissent circonscrire par l'intermédialité, les gender studies et la gynocritique.