Does living in a slum matter for HIV medication adherence? Examining adolescent behavior in Matero, Zambia

by

Suresh Subramanian

Ph.D. University of Nebraska, Lincoln, 1992

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning, in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of

Master of Science in Urban Studies at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology May 2020

© 2020 Suresh Subramanian. All Rights Reserved

The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created.

Signature of Author ……… Department of Urban Studies and Planning, MIT May 18, 2020

Certified by ………. Mariana Arcaya, Associate Professor of Urban Planning and Public Health

Associate Department Head Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by ………. Ceasar McDowell, Professor of Civic Design,

Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning

2

Does living in a slum matter for HIV medication adherence? Examining adolescent behavior in Matero, Zambia

By Suresh Subramanian

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 18, 2020, in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of

Master of Science in Urban Studies at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

Abstract

Three decades into the HIV/AIDS epidemic, annual infection and mortality figures have been dropping rapidly, and there is a sense of an existential crisis averted.

While the AIDS epidemic is coming under control among the broader population, it is growing among vulnerable populations, including the young. Deaths due to HIV have increased by 50% among adolescents, and HIV continues to be the number one cause of death among this cohort group in sub-Saharan Africa. Poor adherence to antiretroviral medication is to blame in large part for this situation. Paradoxically, this is happening in a public health environment where antiretroviral medication availability and

distribution are increasingly unfettered, and guidelines for HIV testing and treatment are robust and comprehensive. What causes these youngsters, who understand the importance of being adherentto missing their life-saving medication?

Rapid urbanization is transforming most parts of the developing world, and over half of Africa’s population now lives in cities. Almost all of this growth has been in slums. Slums in sub-Saharan Africa have a younger demographic, a higher HIV prevalence, and spatially present the most critical target for any efforts to address medication adherence among youth. Where previous studies on medication adherence among adolescents have focused on the patient, the caregivers, and medication-related barriers, this study examines if living in a slum neighborhood creates impediments to antiretroviral adherence. Through 42 semi-structured interviews conducted in a slum neighborhood in Lusaka, Zambia, this study uncovers ways in which the physical, environmental, social, and resource dimensions of the Matero compound may be impacting adolescent HIV medication adherence.

The health of slum residents is one of the primary urban challenges for the

coming decades. Successful health interventions may require a deeper understanding of life in slums and adopting both a slum-centered and a disease-centered approach.

Thesis supervisors:

Ceasar McDowell, Professor of Civic Design, DUSP, MIT

3

Acknowledgments In the final analysis, it’s all about the questions.

I want to express my gratitude to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning for welcoming me into the DUSP family and giving me a chance to pursue this thesis. There is no place quite like DUSP that welcomes people and their questions with such joy. To Professor Ceasar McDowell - my sincere thanks for your mentorship of two decades, your generous availability of time, and relentlessly pushing me to ask the right

questions.

To Professor Mariana Arcaya - a huge thanks for the partnership we built over the last year, for opening my eyes to Neighborhood Effects and for helping me bridge my questions in public health to urban studies.

I came to MIT hoping to work with Professor McDowell and Professor Arcaya, and I am thrilled that I got the chance to do so.

Thank you to my family for all our whimsical conversations, our countless debates, and for challenging me to bring my A-game to all our discussions.

I would like to dedicate this thesis to the youth in sub-Saharan Africa living with HIV and working hard to maintain medication adherence. We, adults, owe you more, and I pray we don’t let you down.

4 Table of Contents Abstract ... 2 Acknowledgments ... 3 Preface ... 5 Chapter 1 ... 8

The AIDS Epidemic ... 9

Youth Adherence to HIV Medication ... 10

Theories of Adherence ... 12

Sub-Saharan Africa and the Growth of Slums ... 14

Slums in Lusaka, Zambia ... 15

Slum Effects on Health ... 15

Adherence Programs in Zambia ... 17

Chapter 2 ... 19 Research Question ... 19 Methodology ... 19 Study Design ... 19 Sampling ... 20 Data Collection ... 21 Field Observation ... 24 Data Analysis ... 25

Results and Discussion ... 26

The Socio-Ecological Model ...27

Individual Factors ... 28

Interpersonal Factors ... 31

Community Factors ... 36

Structural Factors ... 39

Differences between youth from Matero and Kabulonga on Adherence ... 49

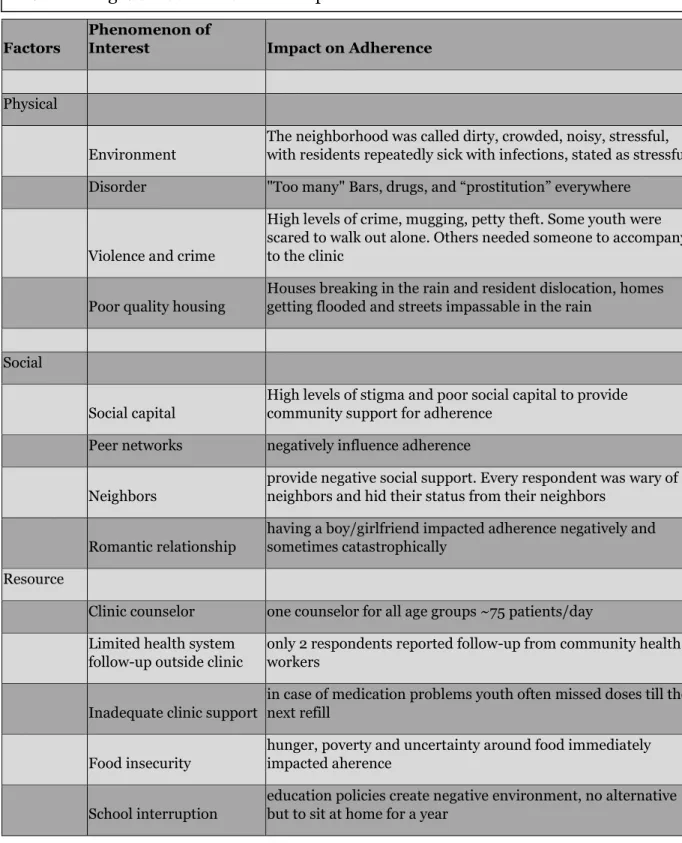

How the Slum Neighborhood Appeared to Impact Adherence ... 52

Thoughts on Methodology ... 60

Chapter 3 ... 63

Conclusion ... 63

Future Directions ... 66

Participatory Approach in Working with Adolescents ... 66

Research – Mental Health of Adolescents Living with HIV ...67

Intervention – Social Support for Adolescents Living with HIV ... 70

Intervention – AI Tool for Improving Adherence ... 71

Limitations ... 73

Epilogue... 77

Appendix Interview Guidelines ... 80

5

Preface

Twenty years ago, I found myself in Matero, a compound (slum neighborhood) in

Lusaka, Zambia, in what appeared to be the peak of the HIV epidemic (data now

confirms that the AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa peaked in 2003). Matero was a

dusty, mostly treeless compound populated by brick homes and shacks. Nearly one in

five adults in Matero were infected with HIV and dying. Lifesaving antiretroviral

medication was limited, when available. A few of us began to work with newborns and

infants infected with HIV at birth, supporting a local physician to provide medical care

to these children and partnering with neighborhood leaders to set up a community care

program. It was a time when many infants in sub-Saharan Africa did not survive to age 5

(median life expectancy for a child infected with HIV at birth was 48 months).

Nevertheless, this diminutive program in Matero managed to buck that trend, and of the

1500 children who were provided long-term care over the last 19 years, only 13 died.

Each death, however, mattered deeply, and the program has evolved with every tragedy.

During this same time, the world has invested over half a trillion dollars on

finding cures and establishing complete public health systems to tackle the HIV

epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. The comprehensive global response to the HIV

epidemic is often held up as an exemplar in public health circles. That may be at risk

now. Three times in the last three years, I have received calls from friends in Matero that

one of the adolescents I had known in the community had died of HIV. Each was a child

I knew personally, intimately in the way you know a child who you have seen every day

for the first few years of its life and later witnessed growing up to become a teenager. In

each case, the young adult had become negligent in taking his HIV medication, and the

6

Adolescent non-adherence to HIV medication is now one of the biggest crisis

threatening to reverse the gains of the past 20 years in the global fight against the HIV

epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. What causes these youngsters, who understand the

importance of taking their medication daily, to do something as hazardous as inviting a

life-threatening infection back? Both public health and academic research are starting to

pay more attention to this, but the pace of youth HIV mortality in sub-Saharan Africa is

only increasing. In the face of this crisis, it is often difficult to read the published

research in scientific terms. Academic reports seem dry, impersonal and small, and

often lacking in urgency to appear almost nonchalant. Are we examining the issue from

all perspectives? Are we chasing down all the causal leads? Are we even asking the right

questions? Over time and from hearing anecdotal accounts, it has appeared like the

youth in Matero were particularly vulnerable and dying in higher numbers than in other

parts of Lusaka. Life in slums often has an existence independent of its descriptors. Was

there something about living in the Matero neighborhood that was making it hard for

these youth to adhere?

As epidemics progress, they develop their own narrative style. In the first decade of this century, the AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa was viewed in human terms through a poetic optic. During the second decade, as the focus shifted to strengthening public health systems, the tone of the narrative has become workmanlike, replete with performance indicators, and tracking metrics. In every interview with the young adolescents living with HIV, there were moments when they revealed how scared they were; when our gaze met in a way where we both acknowledged our bewilderment at their situation. And I have puzzled ever since if we adults are with them in their

7

struggles when they are unable to handle their fight or if a generation is going to vanish without discovering their future.

8

Chapter 1

Gift keeps getting awakened every night by the loud music blaring from the bar next door. At 16, she lives with her grandmother in a compound (slum) in southern Africa. Like adolescents her age, she wants to be with her friends, go to school, and own a cellphone. Her grandmother makes a living selling boiled eggs and chips to the patrons in the bar and stays up till the early hours of the morning. Sometimes Gift works with her, and when that happens, she misses school.

Gift was infected with HIV (the virus that causes AIDS) from her mother at birth. Ever since she can remember, her grandmother has been giving Gift some medicines every day. A few years ago, in response to incessant questioning, her grandmother broke the news to her about being HIV infected. Gift is now responsible for taking her HIV medicines by herself. She is often sad and angry about being HIV infected. Now and then, she gives herself a “holiday” from taking her medicines because she feels healthy. She dislikes the nurse at the clinic who always makes her wait, so sometimes she does not pick up her medication refills on time. She also does not want her friends to know about her HIV infection, so whenever she is out with them, she will miss her medications.

Gift’s story (while fictitious) is that of a typical adolescent in a slum in southern Africa. It is a nightmare scenario for public health officials and those working to contain the AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Adolescents in the slums of Zambia who are on HIV medication take them regularly less than 50% of the time. Without the youth in the slums in Zambia (and by extension in the slums of SSA, which

9

accounts for almost 80% of all youth worldwide living with HIV) taking their HIV medication regularly, there is no path for the world to eliminate the AIDS epidemic. The AIDS epidemic

The AIDS epidemic, now entering its fourth decade, has infected 75 million people and claimed 32 million lives. The epicenter of the epidemic has been SSA, where 11 countries have accounted for the vast majority of the infections and deaths. HIV infections in SSA peaked in 1996 with 3m new cases per year, and mortality from the epidemic peaked in 2004 at 1.7m deaths. In early 2003 then-President, George Bush launched the President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) program, and in addition to the commitment from the US government, the program served to attract resources and funding from a large number of donor countries. The early 2000s were a period of intense activity in SSA –an entire generation of adults was being killed by the epidemic, and many of the world’s leading medical researchers, pharmaceutical

companies, humanitarian agencies, and volunteers turned their focus on sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Anti-retroviral medication (ARVs) started to become more available, their distribution more widespread, and protocols established across all the impacted

countries. An infrastructure for ARV delivery was put in place outside of the national health systems (something sharply criticized since then), and large numbers of people began to be tested for HIV and started on ARVs. This had the simultaneous effect of reducing the number of deaths and slowing down the epidemic.

Today it is estimated that roughly 85% of the 21m people living with HIV

(PLHIV) in SSA are aware of their infection, and two-thirds are on treatment (the global statistics are similar with over 80% of the infected aware of their status and almost two thirds on treatment). Total deaths caused by HIV have declined from 1.7m in 2004 to

10

less than 770,000 in 2018. There is a collective sense of an existential crisis averted, and nations are starting to look forward to a world with HIV contained completely – an indication of which is the recent establishment of an ambitious goal of identifying 90% of all infected, placing 90% of the identified (as HIV infected) on ARVs and ensuring that 90% of those on ARVs see a decline in viral loads. This goal with the catchy title of 90-90-90 is now becoming the basis for public health programs and, in many instances, even national economic planning. While the AIDS epidemic is coming under control as a general epidemic, with over half of the infected now having viral suppression, it is

growing in vulnerable populations, including LGBT, MSM, and the young. The focus of this thesis is the young people living with HIV.

Youth Adherence to HIV Medication

Adherence is the extent to which patients take prescribed medication on time and keep all clinic and lab appointments. While adherence is critical for all medication regimens and is a global concern for chronic ailments (poor adherence costs healthcare systems over $300B/year worldwide), in the case of HIV, it is of critical significance. Successful treatment outcomes are contingent on patients taking prescribed

medications at or greater than 95% of the time. Sub-optimal antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence has negative individual (relapse and higher viral load) and societal (creation of new strains of HIV and an increase in the population of people capable of HIV transmission) repercussions. With two-thirds of the 21 million PLHIV in SSA now on ART, there is rapidly growing attention among researchers and public health

professionals toward the management of ART adherence and a growing realization that adherence levels (a) vary vastly between cohort groups (Nachega et al., 2014); (b) vary

11

over time within individuals (Chaiyachati et al., 2014); and (c) resist easy management, particularly at scale (Haberer et al., 2017).

Adolescents in SSA account for 85% of the world’s 2 million adolescents living with HIV (Adejumo, Malee, Ryscavage, Hunter, & Taiwo, 2015). With continued scale-up of ARV distribution, HIV is no longer the leading cause of death in SSA, and for large sections of the population, it has now become a chronic ailment to be managed and contained. However, for adolescents, it is a different story. Deaths due to HIV have increased by 50% among adolescents and continues to be the number one cause of death among this group. Poor adherence to ART is to blame in large part for this situation. It is a measure of the lowered adherence levels among the adolescents that while they

account for 15% of PLHIV, they account for over 33% of all new infections (Kim et al., 2017). Additionally, there are 1.1 million children below the age of 10 who are HIV+, 90% of who live in SSA, and will be reaching teenage years in the coming decade, making the challenge of ART adherence among adolescents a critical area of concern in containing the AIDS epidemic.

Research addressing ART adherence among youth has been limited, and there are at least three significant gaps in our collective understanding that call for a more in-depth examination. First, there is a scarcity of research hypothesizing and confirming causal linkages to adherence behavior among youth in SSA. In a recent systematic review of youth HIV adherence in sub-Saharan Africa, Ammon et al. summarize 11 studies (an even mix of qualitative and cross-sectional quantitative studies) and tabulate 44 barriers and 29 facilitators to adherence. Most of the barriers, including

forgetfulness, depression, drug side-effects, and perceived stigma, were patient-related with their locus in the individual. The facilitators were, conversely, mostly factors

12

located in the external environment and in social networks. These included caregiver support, peer-groups, and reminders from community health workers. However, as the authors conclude, these studies provide convergence on a few key factors but do not reveal causal linkages.

Second, a lack of longitudinal studies. Adherence is not a one-time event but is often a lifelong commitment to daily action. For most adults, it is not easy for

adolescents and youth; it is even less so. Adolescence and youth are a time of significant physical, emotional, and behavioral development and changes. Generally accepted to cover the period from onset of puberty through adulthood (spanning age group from 12-20), adolescents are particularly susceptible to peer pressure, mood swings, impulsive behavior, risk-taking, and immature judgment. Prima-facie, these factors appear to be relevant to impacting adherence behavior, yet there appear to be very few published efforts examining across-time influences on youth adherence behavior.

Third, studies to date with this group have addressed only individual and social factors in locating correlates to adherence. There is little published work that has examined the lived environment (the neighborhood) as a causal or mediating construct affecting adherence behavior nor studied the subjective lived experience of the youth in a particular neighborhood for its impact on adherence. Later in this discussion, we will address this gap and examine the neighborhood for its influence on adherence.

Theories of adherence

Adherence to medication is an individual action repeated at prescribed intervals. Most models of interventions to support HIV medication adherence are based on

cognitive theories of behavior, and the resulting design of the adherence programs reflect this theoretical stance. For instance, the COM-B model, the most widely used

13

framework for creating adherence programs, views adherence beliefs and behavior as being governed by the patient’s capabilities to manage medication, the opportunity to do so regularly, and motivation to maintain the practice. Other models take this theoretical framing a step further and take into account the impact and influence of social variables on adherence behavior. Amico et al. ( 2018) review a dozen models that include social context as a key factor influencing adherence behavior. These include the

social-ecological framework that views the patient behavior as resulting from the influence of individual factors (motivation, skills, self-efficacy), micro-level factors (significant-close others), meso level factors (community and neighborhood factors) and macro-level factors (policy, health system structure). The social-ecological model is generally

acknowledged to be comprehensive and affirmatively positions the neighborhood as an influence on adherence. While these approaches have found widespread application, it is essential to note that in both categories of models (psychological and psychological-social models of adherence), the locus of the adherence decision and agency is the individual. This is a point we will revisit later in this discussion.

Given the socially embedded nature of the HIV illness – a virulent pathogen, a moral affect-laden and stigmatizing infection, the often visible signs of the progression of the disease, and the preponderance of the condition among the poor – it may be restrictive to view the HIV infection in purely biological terms and the adherence behavior as a strictly individual agency in action. The patient-provider relationships often have structural power inequities and paternalistic overtones (Broyles, Colbert, & Erlen, 2005). In the case of infectious illnesses such as HIV and Tuberculosis, this relationship is also infused frequently with blame (for becoming infected, for missing medication) and moral judgment (the overall sexually transmitted nature of most HIV

14

infections). As a result, even socio-ecological models of adherence (which ultimately still view adherence as the actions of an independent agent) may be somewhat limiting in attempting to understand and explain the behaviors of the infected. A more subjective understanding of the lived experience of the illness may be required to uncover daily adherence practices.

This thesis acknowledges these dimensions of adherence and adopts (in addition to a socio-ecological approach), a subjective framing of the lived HIV illness in

understanding adherence behavior. While this comprehensive theoretical position could come up for criticism as being too expansive to reveal any new learning, it affords an exploratory study such as this, the opportunity to examine both the effect of the neighborhood as well as the lived experience of the patient within the neighborhood context. In the case of the youth in SSA, this neighborhood context is often a slum. Sub Saharan Africa and the growth of slums

Rapid urbanization is transforming most parts of the developing world. The UN Urbanization Prospects 2018 report concludes that 55% of the global population is now urban. This growth has been particularly pronounced in Africa, where the urban

population has grown from 30% of the national population to over 60% in 20 years. In Asia and Africa, much of the urban growth has been in slums. Slums have been defined variously in the literature, but as a whole are characterized by poor infrastructure, sanitation, impermanent tenancy, and in most instances, a high density of population. While even as recently as 2010, the UN was working on a vision of “cities without slums,” urban planners now acknowledge that slums will be a part of the city landscape for the foreseeable future. In SSA, the growth of slums has been particularly significant. Official census reports for SSA place slum populations at 60% of the urban population

15

and more recent approaches to measuring residence using drones and satellite imagery place the slum population closer to 80% of the urban population. `

Slums in Lusaka, Zambia

Zambia, a landlocked country in sub-Saharan Africa, has grown in population from 11m in 2000 to 18m in 2019. During the same time, Lusaka, the capital city of Zambia, has more than doubled in population from 1m to 2.6m. The city has a markedly colonial history, initially settled by white farmers and operating as a key transit point between the resource-rich regions of central Africa (presently Congo) and the various ports. Prior to gaining independence in 1964, Zambia (then Northern Rhodesia) was a strategically vital part of the British colonial economy in southern Africa. Until the mid-1940s, only black African men who worked in Lusaka were allowed to live in the city (in specially designated areas). Women and families were permitted into the city after the passing of the African Housing Ordinance in 1948 (Myers, 2006), which formalized the provision of land for black Africans to build shacks and small residences. Most of the land allotted for this purpose came from the white (and in a few cases, Asian) farmers, and the resulting slum neighborhoods called compounds still carry the names of the farmers who originally owned the lands (e.g., George compound, Chelstone compound, etc.). These compounds have continued to swell as the city population has expanded and now account for over 70% of Lusaka’s 2.6m residents.

This study will be based in the Matero compound, one of the first two compounds to be created in 1950.

Slum effects on health

Neighborhoods impact the health of their residents. There is now a rich body of research that has proposed and explored the impact of the lived environment (the

16

neighborhood) on health (Oakes, Andrade, Biyoow, & Cowan, 2015). Poverty, health, and public policy often intersect in mutually reinforcing ways in (spatial) neighborhoods to generate “concentrations of disadvantage” (Jargowsky & Tursi, 2015). There is

extensive support for the impact of the neighborhood on all aspects of health, including susceptibility to chronic illnesses, infectious diseases, violence, and stress-related ‘weathering.’ Earlier investigations on ‘neighborhood effects’ tested for one individual factor at a time. With the increasing availability of sophisticated quantitative techniques to ‘tease out’ the effects of multiple factors concurrently, including through interactions with other factors, researchers are now equipped to explore ‘multi-level’ and complex causal models (Arcaya et al., 2016). This permits a more intricate exploration of multiple neighborhood factors simultaneously and helps inform programmatic interventions in a more targeted manner.

Slums are a particular instantiation of spatially defined neighborhoods, and there is now a growing field of study, turning its attention to slum effects (Ezeh et al., 2017). This thesis is situated in slums, and at the outset, it is essential to clarify issues of terminology. The term ‘slum,’ by the nature of its origins, carries pejorative connotations about the place and its peoples. Words like informal settlements, unauthorized settlements (a favorite among governments), or informality are now employed (in the place of ‘slum’) in the academic circles. However, given that the

generally accepted definition of slums is that set out by the United Nations, and various UN agencies continue to use the term slum in all their publications, we will do the same.

Slums vary in form and composition. Not all poor people live in slums, and not all people living slums are poor. However, several factors persist in common across slums, including overcrowding, insecure land tenure, inadequate water, and sanitation

17

infrastructure, and a relatively higher level of poverty. Slums have existed for hundreds of years, and with the recent urban boom, new ones have sprung up, others have

expanded. Whatever the temporally proximal cause that leads to their creation, slums have their origins in power inequity. Slums impact the health of their citizens through multiple causal pathways. The physical environments of slums, characterized by

intermittent, inadequate and polluted water supplies, substandard sanitation, irregular to non-existent trash collection, and environmental pollution, impact health through infectious and vector-borne illnesses. Other factors such as violence, social dysfunction, insecurity around tenure, and lack of a political voice lead to heightened levels of stress that weather its citizens –amplifying (existing) illnesses and causing new ones (Corburn, 2017).

Adherence programs in Zambia

ARV adherence programs in the compounds of Lusaka are one-size-fits-all and are managed from the government’s neighborhood clinics. The programs comprise of two parts. (a) An initial education session – provided by the physician on the importance of taking ARVs regularly and (b) ad-hoc support from the network of Community Health Workers (CHWs) who support patients on ARVs on a day to day basis. Upon starting ARV medication, all patients are provided the names and contacts of the nearest care workers to their homes and assigned to a care worker. The CHWs, in-turn, are also informed about newly enrolled patients in the program assigned to them. More recently, the Center for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIDRZ) has been testing and rolling out community adherence groups – a neighborhood approach to bringing together small groups of people on ARVs to provide peer support to each other. Given the nature and composition of these CAGs, the participants are almost exclusively

18

adults. For their part, the adolescents in the slums of Zambia are on their own when it comes to maintaining ART adherence.

This thesis will examine the effect of the slum neighborhood on HIV medication adherence among youth in the Matero compound of Zambia.

Summary:

• Anti-retroviral Treatment (ART) adherence rate among adolescents and young adults (youth) in SSA is <50%. HIV continues to be the leading cause of death for youth in SSA.

• Previous literature has identified 44 factors (Individual, Medication, Caregiver, and Health system factors) as “barriers” to HIV adherence for youth in SSA. These include individual and social factors but do not include the impact of the neighborhood.

• Slums in SSA account for a large portion of the population. Slums in Africa have a higher HIV prevalence, a higher density of youth, and any efforts to target HIV adherence among youth must focus first on slums.

• Current adherence programs in the slums of Lusaka, Zambia are a one-size-fits-all approach and are limited to education sessions in the clinic and the

availability of community health workers (CHWs) in the community for support as needed.

• This study argues for examining the lived experience of HIV by the youth in a slum environment.

19

Chapter 2

Research Question

This thesis will ask and attempt to answer the question:

Does living in a slum neighborhood impact ART adherence behavior among youth?

In attempting to understanding how a neighborhood impacts the health of its residents, several useful operationalizations have been proposed. Given the nature of the questions being addressed in this thesis, the study will adopt a comprehensive operational framing put forward by Ettman et al. 2019) that dissects the neighborhood into three environments – physical, social, and resource – for systematic examination. The physical environment includes factors such as the density of dwellings, availability of electricity, water and sanitation, rainfall protection, ventilation, overall comfort,

noise, distance to the clinic, distance to school. The social environment includes stigma,

social support, and interactions with peers, family, and friends, attendance in church,

recreation and relaxation with friends, factors that contribute to social disorganization

in the neighborhood, social stressors, relationship with CHWs, experience in the clinic.

The resource environment comprises factors such as availability of CHWs and support

when needed, clinic support when not feeling well, and help in keeping adherence from

the clinic.

Methodology

Study Design

This study of adolescents took place in the Matero compound and Kabulonga in

20

Matero Reference Clinic, George Clinic) that also serve as ARV distribution centers. A

few of the adolescents were enrolled in the ARV distribution program at the University

Teaching Hospital (UTH). This was a result of where their caregivers had first taken

them for testing, or if their HIV status had been discovered during a hospitalization.

Sampling

The study used a convenience sampling approach to identify participants. Three sets

of participants were recruited for the study.

a) Adolescents in Matero – these were to form the bulk of the study participants and

were residents of Matero.

b) Adolescents from Kabulonga (a wealthy neighborhood in Lusaka)

c) Clinic workers from Matero city clinics who work with adolescents

In identifying potential adolescent participants from Matero, three criteria were set up

as preconditions. Participants should be (a) between 14-20 years of age; (b) should be

on ARVs and managing their ARV regimen by themselves, and; (c) should be residing in

the Matero compound. For the second group, the same criteria as above were used

except that these youth were to be residents of Kabulonga.

The assistance of the Matero Care Center was utilized to recruit participants. The Matero Care Center (MCC) is a local Zambian NGO and manages the care of over 450 HIV+ children in the community of Matero in Lusaka, Zambia.

Healthcare workers in the three clinics were briefed in detail about the study and

their permission was sought to work with and through them for recruiting participants

from their pool of patients. After the necessary approvals were received, clinic workers

21

all participants had similar expectations about the study and their participation.

Participants were recruited by the clinic and care workers during their routine

interactions (medication refill visits, regular check-ups, and follow-up visits). All

recruited participants were managing their HIV medication regimen independently and

were visiting the clinics for ARV refills and follow-up visits by themselves.

The research was approved by the institutional review board at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Studies involving stigmatizing and personally

painful illnesses like HIV, and that too with young adults, is fraught with concern. The

research team spent a great deal of attention on the design and execution of the study to

ensure safety and confidentiality for all participants. A clear consent form with simple

language was created. Once the final list of participants was assembled, participants

were given time slots to visit the interview location. All participants were given bus fare

and a packet of biscuits as compensation for their time. However, they were not told

about the payment until after the interview was over to ensure there would be no impact

of potential compensation on their responses.

Data Collection

The thesis presented a methodological challenge in that we were attempting to answer questions that were either conceptual (e.g., the power imbalance between youth and public health directives) or arising from practice (we are witnessing poor adherence among youth and do not know why). We wanted to inform theory as well as practice. We were setting out to answer questions such as:

1) What is the narrative the youth carry about their HIV infection? What is their narrative about their lives, their surroundings, their social networks, and the

22

physical environment they lived in? Within the narrative of their illness, how do youth frame their HIV treatment adherence?

2) How does social stigma in the neighborhood play out in their lives? In their social networks? In the clinic infrastructure and community health worker networks? How is stigma manifest in the slum neighborhood?

3) Agency – What role do the youth see for themselves in the adherence process? How do they perceive this role? Do they sense an agency in their health? 4) What is the lived experience of power imbalance (with adults, with the clinic,

with the care workers) in the adherence process for the youth?

5) How are the current adherence programs interpreted subjectively by the youth? To that end, the study was designed to employ two qualitative data collection

techniques – the semi-structured interview and field observation. The semi-structured interview process allowed for an interactive conversation with each participant to better understand their adherence behavior and the subjectivity of their illness within the context of the slum environment. The latter permitted the researcher to first-hand to observe the lived experience of their HIV illness within the context of the slum. The positionality of the youth in the interview process was as an active participant in the research process and not a passive actor.

The interview guide is included in Appendix A. While the interviews mostly

followed the outline laid out in the guide, the mood and tempo were kept relatively

relaxed, and the conversation was allowed to go where the participant responses led it.

Probes were utilized to help the participants expand on specific comments. All

interviews were conducted by this researcher and the nurse from MCC. Interviews

23

that where necessary, they could switch to the local language Nyanja. The nurse was

familiar with Nyanja and translated in real-time. As the interviews progressed, it

became evident that having two interviewers allowed for the process to resemble a

conversation, and the two interviewers were often able to key off one another and also

pursue lines of questioning without making the interviews appear like an interrogation.

The interviews with the 34 adolescents from Matero were conducted on the premises of

the Matero Care Center, which is located centrally in the Matero compound and was

well known to all participants. The interviews were conducted in a room in the clinic

customarily used for patient discussions. Interviews with the five adolescents from

Kabulonga were conducted in a private location near Kabulonga's main intersection.

Meetings with the three clinic staff were held in the Matero Care Center.

After each interview, the two interviewers spent, on average, 60 minutes

debriefing. This time was also used to ensure that in addition to the text of what was

said, the non-verbal cues were also immediately documented, and nothing was left to

memory. This process, while time-consuming at the moment, allowed for a more

accurate and complete transcript for each interview, and both interviewers felt that the

debriefing process helped make the notes richer in detail. The two interviewers worked

during the debrief discussions to go over all the instances where the participant had

provided an insight into their adherence to categorize participants into poor/fair/good

adherence categories. The written transcripts of the interviews were prepared by the

researcher and reviewed and confirmed by the nurse each day. Finally, once the

transcripts were created for each interview, all identification information about the

participant, including their name and location, was stripped and replaced with a coded

24

the Matero Care Center, and this researcher did not have any further access to this

information.

The purpose of the interview process was threefold (a) understand better the

lived experience of HIV for each participant; (b) understand the process and experience

of managing their ARV regimen for each participant; (c) understand the various factors

that influenced the management of ARV for each participant. The semi-structured

interview guide was constructed with these objectives in mind, and the two interviewers

discussed these interview objectives in detail prior to commencing the interviews.

The purpose of the interviews with the clinic staff was to uncover a second

perspective on the lived HIV experience of adolescents in Matero, the challenges faced

by youth in Matero in managing their own ARV regimen, and the challenges faced by the

clinic staff in providing care and support to the adolescents in their medication

adherence.

Altogether, 42 interviews were conducted during January 2020. All participants

were carefully read the consent form at the start of the interview meeting and given

sufficient time and flexibility to ask questions, decline to participate, or once started, to

terminate the interview at any time. All participants gave voluntary verbal consent to

proceed. No participant refused to participate or requested to end the interview

prematurely. All participants were thanked and debriefed for any concerns or any

requests from their side.

Field Observation in Matero

Observation research is a vital part of ethnographic data collection. Observation

research allows the researcher and team to supplement interviews with a first-person

25

information to the interview findings. In this case, the author walked through the

marketplace, bars, and lanes in Matero for 60-90 minutes every day as part of

first-person ethnographic data collection. These walks were often between interviews or at

the end of the day. Notes from the field observation walks were recorded each evening

by the researcher.

Data Analysis

Ethnographic interviews have been incorporated into research in multiple ways.

From being used as a factual report of reality, as projections of researchers’ views of a

phenomenon, to being part of a co-created constructed reality by the researcher and

interviewee, interviews serve many purposes in building an understanding of particular

issues. In our case, the interview process was grounded in the theoretical view of HIV

medication adherence as a socially embedded behavior that is part of the lived

experience of being HIV positive. Indeed, the motivation for adopting ethnographic,

semi-structured interviews as the chosen methodology over a survey or a pure

observation research was based on this theoretical premise. The research design, the

framework for the semi-structured interviews, and the analysis of the interview data

reflected this approach.

The completed transcripts were studied in detail before distilling them in a

manner that allowed themes to emerge naturally. The interview transcripts were printed

and laid out on the floor of a classroom on campus. This allowed the researcher to spend

many hours trying to take in all the interviews and allow themes and factors to surface

naturally. Themes emerged both from the content of what was said, and the specific

26

interviews using different colored highlighters. It is essential to point out that no

a-priori framework was created to generate themes. Since changes in body language and

tone were journaled along with the exact words that participants used, the generation of

themes was further enriched. Nyanja words were translated for meaning but were left

unchanged in the transcripts. Overall, the researcher maintained active attention to

ensure that researcher bias was minimized in each stage of the analysis stage.

An important point to reiterate is that the transcripts were not ‘reduced’ to

themes. That would be a form of deconstruction and reconstruction that could at best

make the interviews less detailed and, at worse, misrepresent the meaning the

interviewees were conveying. Instead, specific themes were allowed to surface to answer

two questions – (a) what seem to be the factors that are serving as barriers or enablers

of adherence and (b) how does the slum neighborhood impact adherence behavior. The

quest for answers to these two questions was driven by examining the interview

transcripts with an open mind and holding these questions alive throughout the

analysis. The researcher did not seek to find information that explicitly confirmed

previous findings or refuted them. No diagrams or visuals were used.

Results and Discussion

In most academic writing, the “results” and “discussion” sections are kept

separate. In this instance, given the subjective nature of HIV adherence and the

ethnographic methodology employed, the thesis will combine these two sections into a

single free-flowing narration. This section will be presented in two parts. The first part

will discuss the findings from the interviews and the primary factors that appeared to

27

add to the existing research in this area. The second part will narrow the context of the

discussion to the Matero slum neighborhood and address specific findings that address

the core question of this thesis –does living in a slum neighborhood impact adherence

behavior?

In what follows, details on names, quotes, situations, and events have been

deliberately altered without in any way affecting the findings or conclusions.

The Socio-Ecological Model

A framework employed frequently to examine the social and structural influences

on behavior is the socio-ecological model (Bronfenbrenner 1977). The socio-ecological

model (SEM) has broad applicability. Within public health, the SEM approach builds on

the understanding that social and environmental factors individually and jointly impact

the health of populations, particularly vulnerable groups and those who face health

disparities (Kaplan, 2004). Visually it is often depicted with the individual situated

within a set of nesting circles that each represent a layer of influence. The circle/s closest

to the individual is viewed as the most proximal influence and is comprised of personal

and interpersonal influences. Each subsequent outer circle represents another set of

influences that are further removed from the individual but are no less important. The

next outer ring represents influences and interactions that the individual has direct

contact with including the social networks, and peer groups. The next outer circle

comprises influences such as the institutions, the environment in the community,

violence, and dysfunction, and social capital within the neighborhood. The next outer

layer contains the structural elements, including community resources, infrastructure,

and policies that influence the neighborhood. The model, as employed in this

28

(in our case, medication adherence) and is particularly suited for highlighting the

impact and interplay between individual, family, community, and structural influences.

The following discussion will be framed using these four layers of influence outlined

above in our attempt to provide a better understanding of the ways in which adherence

is impacted by these factors and identify points of intervention.

Individual factors

Disclosure

Within the HIV care continuum, disclosure is the process of revealing their HIV

status to a person. It is a moment that is fraught with the potential for trauma and

marks a milestone in the life of every person living with HIV (LeGrand et al., 2015).

29

When it comes to disclosing their HIV diagnosis or status to a child, the process is

complex and challenging to implement. Along with expanding the availability of ARVs

after 2005, public health systems in SSA significantly improved their capacity for

testing, ARV distribution, and follow-up care for children. The vast majority of the

children perinatally infected with HIV at birth were starting to live longer and,

disclosure of their serostatus became a significant psychosocial challenge for the

surviving parent/s, grandparent/s, aunts, siblings (the primary caregivers of the child).

Lack of adequate preparation, training, and a combination of guilt and stigma prevented

caregivers from having the difficult conversation with the child about his/her HIV

status. In a typical scenario in SSA, the child was given ARVs by the caregiver but was

rarely told about her HIV status. This process would continue until the pre-adolescent

child would begin to resist taking medications and accost the caregiver about it. This

presented a psychosocial challenge for the caregiver who would often respond to the

situation by resorting to small lies “you have to take this because it will make you

strong” “you have asthma, and if you don’t take it, it will stop you from breathing”. In some instances, they initiated incremental disclosure with the goal of full disclosure by

early adolescence. National guidelines recommend full disclosure of HIV status by the

age of 12, though studies have repeatedly found that in SSA, the disclosure process is

delayed well into late adolescence (Cluver et al., 2015). Research has highlighted both

negative and positive psychological, behavioral, and social outcomes from the

adolescent disclosure process (Zanoni, Sibaya, Cairns, & Haberer, 2019).

Every single participant in our study had been disclosed. The most recent was

someone who had been disclosed 18 months ago, and the oldest to be disclosed was 14

30

caregiver or a family member, since Zambian law restricts clinics and testing centers to

disclose only to adults (over 18) unless accompanied by a caregiver. Interviewees

described their moment of being told they were HIV+ (disclosure) as being disorienting,

isolating, and painful.

“I felt why me, why I’m the only one with this”

“I was disclosed by the sister to my mom. I felt really bad. Everyone

understands HIV as a very bad thing. So I was very hurt”. “I was still angry and never really accepted. Then I outed my medication with not accepting and bad feeling of why me?”

“I felt so bad, my mind started growing, and I heard my friends talk bad about people who are HIV..why they are saying bad things about people like us..I used to feel so bad I used to cry in my room.”

Almost a third of the young people said that upon learning about their status,

they felt like they were going to die.

I got confused. I know that the only way to get HIV is to have illicit behavior with girls or using sharp objects and I was not doing both

Some ran away from home (NC); others stopped eating. QN said that he started

fighting with his father and never talked to him for two years (in particular, his story

reveals the deep undercurrent of emotional trauma within families from HIV).

Dad told me one time about all the bad things he did the sickest things he did. He used to go to a lot of bars. He used to chill a lot. That’s when dad told me I am sorry to give you this. So that’s how we made our friendship again.

His father, who was also HIV+, finally broke through their mutual wall of silence and

one day had the above conversation. PM reported that from that time he and his father

“have become close, and many times I go with my father to do piece work..sometimes we go to eat chicken.”

In 9 of the cases, there appeared to be problems in disclosure. These included abrupt

31

In almost all these cases, the participants reported a variety of feelings and reported

behaviors that were indicative of psychological trauma (LeGrand et al., 2015; Patton et

al., 2016). This reaction was not limited to only poorly done disclosure. Despite

seemingly appropriate protocols being followed, in 7 cases, participants reported

distress and reactive behavior. In every case where the disclosure was done poorly, there

were accompanying behavioral responses that impacted adherence negatively. In all of

these cases, the participants related how they decided to stop taking ARVs and even

questioned their reasons to live. A scan of all the instances with problematic disclosure

showed that barring 2 cases all others fell into our poor or average adherence category.

Interpersonal Factors

Family support

Family support – family influence on adherence showed up in multiple ways – almost

all were positive. Family influence showed up in 3 broad ways:

1. Provided tools, reminders, and follow up support. Family members (usually the primary caregiver) helped make the adherence process easier through daily

reminders and follow-ups, by bringing the ARVs and water daily at the

designated time and helping with taking the medicines and provide oversight to

ensure that the adolescent was maintaining adherence.

2. Institutionalized HIV and medication adherence within the family. Family members participated in the logistics of picking up ARVs, accompanying each

other to the clinic, storing the medicines carefully at home, supporting each other

in case of any side-effects and openly discussed and planned activities to account

32

3. Framed the HIV situation and adherence through words, attitude, and action. Family members taught the adolescents adherence-management skills, and

caregivers, in particular, worked to destigmatize the experience of living with

HIV.

A more in-depth analysis of interviews with the patients revealed that almost all

youth in the adhering group had one or more strong caregiving dyadic relationships at

home. These were often with the mother, an aunt, or a grandmother and, in some cases,

the father. In many instances, these were relationships that had predated disclosure and

only became stronger after disclosure. Some patients had multiple strong dyadic

relationships at home – often with a parent and another person on ART. In every case,

the strong relationship helped to provide all three aspects of support discussed above.

When this strong relationship was with the mother, the dominant support was most in

the form of providing tools and reminders and follow-ups. In contrast, with a sibling,

the relationship often prioritized framing the HIV situation and normalizing it – “she

always encourages me and tells me I am completely normal” “she always tells me I can achieve anything.” This aligns with recent findings on youth adherence by Kelly et al. (2014), who found that while causality was not established, social support and scores

were found to be higher among people who adhered.

A few of the younger adolescents spoke about a strong paternal influence on their

adherence through punitive responses to non-adherence. In each case, the youth

reported that their dad, who was also on ARVs, would “whip me” or “beat me” if he ever

33

Additionally, two other aspects of family support came through in some interviews.

First, the family member with the closest relationship to the youth often went to the

defense of the child/youth in instances where there was ‘experienced’ or ‘anticipated’

stigma. Often these situations involved a neighbor or a visiting relative who would

suspect that the youth was on ARVs and say something (or begin to say something)

stigmatizing. The family supporter would immediately step in to defend the child, and

this helped to strengthen their relationship further. Second, the close family supporter

would play a watchful role over the youth and ensure that they “did not go with bad

boys” or fall into ‘bad’ company - “my mother always checks who I play with and does not want me talking to her” (referring to a girl who used to be a friend in the past but had recently become pregnant at 15). When probed further, these youth responded that

they received more attention and support that the other children in the family.

However, family influence was not always positive. There were four examples of

chronic negative interactions within the family. Each time it came up in the interviews,

the situation involved an uncle, aunt, or a stepmother.

“my aunt would say that I could not become anything because I am positive. It was confusing to me. I felt like I was not a human enough. I was really hating me so much” For instance, TN reported that his uncle, who lived in the same house, would berate

him every day when his father was away at night working. The father’s brother would

come to the door of his room and would yell invectives and “mean things that I was a

sick person who should not be living” every night. The youth reported that it was the most stressful part of his daily life, and often his father would have to counsel him. In

other instances, it became clear that poor adherence or risky behavior by the parent or

34

was herself lax on taking her ARVs, and the youth said that “I feel sometimes like why I

should drink my medicine daily when she does not”. The mother sold cassava in the marketplace and often came home late and did not take her ARVs.

Lastly, it appeared that, for the most part, the parents or caregivers who had been

part of the child’s ARV history for many years continued to maintain a reasonably strong

presence and influence well into the child’s adolescence and, often in tangible ways

every day. They were part of the support structure that the youth relied on for being

adherent. This does raise the question of how the child would manage their adherence if

they had to leave home and be independent or if the parent/caregiver ever left the

immediate surroundings (died, moved away, etc.).

Close Friend

Many youths reported having a close ‘other’ outside the immediate family (a

friend, a cousin) as a significant influence in their lives. Seven of the 15 youth who

reported strong adherence and 4 of the ten youth in the fair adherence group reported

having a close friend/s or a cousin who “supported” them and “encouraged” them. In a

prototypical situation, their HIV status was inadvertently revealed to this ‘other’ friend

or cousin because they “met in the clinic and we both realized that we were taking

ARV,” or in some instances, a visiting friend or cousin inadvertently discovered the ARVs and accosted them “she had come to stay with me and asked me what I was

taking daily.” In other cases, the youth volunteered the information about their HIV+ status to the other in a moment of close friendship

“he told me a lot of things that happened at his place and his struggles in his home and his grandfather's place. That’s when I told him that I am taking medication. He said better you take medication than to live without taking medication..he is now my best friend.”

35

In every example, the youth reported that they became “close” to this friend or cousin,

and in 9 of 11 instances, they said they were “very close” “like a best friend.” In all but 3

of the examples, the other was not HIV+. This is important to note since it validates the

role of people not living with HIV in providing support. This close relationship provided

a sense of shelter and comfort to the youth, and they felt that this person was important

to them.

Intimate Romantic Relationships

Seven of the 34 youth were involved in steady sexual relationships. Four of the

seven were young women, two were living with their boyfriends, and one of them was

married and already had a child. In every instance, being in a sexual relationship

appeared to impact adherence negatively. In all cases, they concealed their HIV status

from their partner (and consequently had to hide their ARVs at home), and, in every

case, it came in the way of their taking their medications on time. None of the seven

were defaulting entirely, and none of them appeared to be symptomatic of any HIV

related illnesses. JC, the young girl who was living with her husband, reported that she

hid her ARVs in the kitchen and would take her medication if her husband was out of

the house. In every case, they reported having unprotected sex and no contraception.

“we are renting a place together, but we don’t share status to each other” “we love each other and don’t want him to know the status, or he will leave.”

In the two cases where the young women were living with their boyfriends, both

reported that they kept their ARV elsewhere (in Matero) and would go there daily to

36

to the process of taking ARVs daily. In all cases, they reported that they were unaware of

the HIV status of their boyfriends. GM said that her husband refused to take an HIV test

when she suggested it one time.

“You then have to approach it indirectly, and if he says that I cannot live with an HIV person, then leave them completely. You can say let’s go to the clinic, and if you are positive, I will accept, what will you do if I am positive”

We asked these adolescents in romantic relationships a few additional questions.

We asked if they knew about any of their friends who were in romantic/sexual relations

and how they handled the issue of revealing their HIV status. None of the boys reported

knowing about any friend of theirs who was HIV+ and in a relationship. Two of the

young women reported knowing of others who were in similar situations, and in both

instances, they said that their friends also did not reveal their HIV status to their

partners. In addition, GM reported a story about a friend of hers who had “thrown

away” her ARVs and had later fallen sick and died. Community Factors

Peer groups

It emerged from the interviews that peer groups – i.e. when groups of youth got

together not as dyads but as groups, the influence of peers on adherence was almost

always negative. In all of these recollections – 22 out of 34, the youth reported that the

group attitude and narrative about HIV was one of (a) intense stigma “I would never

live with someone who was HIV” “they say that they would not share anything from someone who is +. Why? I am not an animal? It is only a condition” (b) hopelessness “I have many negative friends who say that they will kill themselves if they got HIV” and

37

(c) anti-ARV – “these ARVs are unnecessary. You don’t have to take ARVs to get better;

HIV is not that bad”.

The larger peer group presented a strongly stigmatizing and discouraging role

within each adolescent’s life, and some were wary and suspicious.

“I disclosed my status to my friends. they started running away from me, and now they all talk about me.”

“I am not that comfortable telling my friends my status. When I am not there, they will be discussing my status. You feel that I am the only one with the disease.”

“you take and take the ARV; the virus is not going away. There is nothing that will heal you. Only death, better you die if you get HIV”

When the youth got together, the discussions on HIV status, ARVs, and adherence were

always tinged with bravado and denial of HIV’s impact on health and their lives. Peer

pressure was singled out as a significant influencing factor in youth dropping out of

school and defaulting on adherence.

Peer pressure influenced young men to drop out of school and start doing “piece work”

(daily labor).

“lot of youth in Chunga they drop out of school because of peer pressure..they want to have money …they want it fast”

“some of the children stop school because they feel they have grown and they start doing piece work to get some money They shout and get the bus loaded” Neighbors

The topic of neighbors came up unprompted in 18 of the 34 interviews. Where it

was not brought up by the interviewee, we introduced it into the conversation during a

38

despair with neighbors. Uniformly, neighbors represented a threat and a source of

stigma rather than support. For many participants, neighbors were the first source of

stress they encountered once they stepped outside the family. In every case, neighbors

were reported as being a negative influence on adherence. Neighbors were “mean,”

“gossiping,” “always gossiping in my back” and were said to be “selfish and hurtful”

and to have “mocked” them when they suspected that there was someone in their home

who was HIV+ “there she goes to get her ARV”.

“Sometimes if the neighbor like a tenant who are renting knows I am taking medication he can take advantage of me and shout at me that you are taking medication, haven’t your parents told you this and that. Why are you taking medication?”

Almost all youth reported that they did not seek help from their neighbors because they

would “talk about it,” yet in other parts of the interview, they recounted that in their

neighborhood, people help each other. It appeared that the negative effect was

associated primarily with the immediate neighbor and not the broader community.

The church

The church is one of the pillars of the Zambian society (Campbell, Skovdal, &

Gibbs, 2011). Zambia ranks second in the world in church attendance, with 85% of the

population attending church at least once every week, in many instances, multiple times

a week. As we discussed their daily lives and activities, references to “in my church

group” appeared numerous times. During the interview, we probed deeper on their networks within the church and the role the church played in their HIV life. Twentynine

of the 34 youth in Matero reported regular church visits and having a network of friends

39

of any of the youth we interviewed. All of the participants stated that they had not

revealed their status to anyone at church, including the pastor. All of the participants

confirmed that the church did not have support groups or any activity for HIV

education, support, etc. When parishioners died (HIV continues to be the number one

cause of death in Zambia), the church members would participate and pray, but the

topic of HIV would not come up in discussions. This author has been working in Zambia

for 19 years going, and this near-silence about HIV on the part of the church has

changed little during this time. Over the last decade, a few pastors in Zambia have been

taking an active stance in speaking out about HIV and maintaining adherence. However,

in the interviews we completed, we did not encounter any similar example in Matero.

On the contrary, in two cases, we heard about pastors who were recommending that

people “throw away your medicines” and come to them for the cure.

“There are these pastors who come from abroad and ask them to bring water. Then they pray for them and pray for the water and tell them to stop taking the medication and drink the water.”

In one case, a pastor would pray for them and place his hand on their heads, and as JC

reported, many women in the church would cry and say that they would throw away

their medication. The Zambian government has promulgated laws that include

incarceration and punitive fines against any individual who encouraged not taking HIV

medication.

Structural Factors

Poor Quality Housing

While some parts of Matero have cement brick housing, poor housing

40

within Matero are mainly run down and have sheets of cardboard or plastic for walls.

Three interviewees reported that their houses were breaking in the rain (January 2020

when these interviews were conducted was the wettest month in Zambia over the last 3

years). Throughout the interviews with these participants, the concerns from the broken

walls (in two cases) and broken roof (in one instance) seemed to overshadow their

interview responses

“When its rainy season, things get scattered. Matero is not a safe place”.

In general, participants spoke about the significant disruptions and hardships in Matero

during the rains. In one case, the family was forced to move into the one remaining

room. In another, the youth had to move to live with a relative. In both cases, ARV

adherence had been impacted over the last few weeks, and any discussion on HIV

adherence appeared less urgent and salient.

“Many people go in the water and die in the water that rises to the level of chest and died of electrical shock. People don’t feel secure.”

Bars

Now we come to a set of issues that were mentioned as one of the biggest problems

in Matero community - bars, drugs, prostitution. The dense Matero compound streets

are dotted with makeshift bars that brew their liquor (jiri-jiri and shakey-shakey) and

also sell bottled beer. The bars are often unlicensed, open almost 24 hours (from dawn

to 3 am or so), and heavily patronized through all hours of the day – including early

morning hours.

“ they play a lot of loud music, and there are too many mashabin (bars)… when I start studying, they start to play music, and it disturbs me” “There is too much drinking in Matero..people drink because they feel they are not solving problems.”