i

^Hiey

HD28

.M414

rvo-34I(»

COMPUTER-BASED

DATA

AND

ORGANIZATIONAL

LEARNING:

THE

IMPORTANCE OF

MANAGERS'

STORIES

David

K.

Goldstein

April

1992

CISR

WP

No.

234

Sloan

WP

No.

3426-92

Center

forInformation

Systems

Research

Massachusetts Instituteof Technology

Sloan School of Management

77MassachusettsAvenue

COMPUTER-BASED DATA

AND

ORGANIZATIONAL

LEARNING:

THE IMPORTANCE OF

MANAGERS'

STORIES

David

K.

Goldstein

April

1992

CISR

WP

No.

234

Sloan

WP

No. 3426-92

®1992

D.K. GoldsteinCenter

forInformation

Systems

Research

Sloan

School

ofManagement

TSlT. UBRAHIhb

JUL

16

1992.:i>mputcr-baseddataandoraaniz-aliotialIcamini;

COMPUTER-BASED

DATA

AND

ORGANIZATIONAL

LEARNING:

THE IMPORTANCE

OF MANAGERS'

STORIES

While

many

organizations are investing largeamounts

ofmoney

to provide computer-based data to their managers, little isknown

abouthow.

or even whether,managers

use thesedata to learn about the business environment. This issue is explored by examining

how

grocery product

managers

use supermarket scanner data toleam

about changes in the marketing environment. Managers' stories play a central role in the four step process used by one productmanagement

organization as it learnsfrom

analyzing computer-based data. First,a

manager examines

the data and looks for unexpected results—

findings that contradict one ormore

of her stories about the marketing environment. If a surprise is found, themanager

carries out a relatively unstructured, multi-stage process to

make

sense out of the unexpectedresult. This process can be

viewed

as a dialoguebetween

the result and a set of tools at the manager's disposal (including analyses of computer-based data). Next, themanager

tells the story to share her insights with peersand

superiors, developing acommon

understanding.Finally, the

manager

creates an official story, that is used to 'sell'new

marketing approachesto people outside theproduct

manager

organization—

the sales force and supermarket buyers.Keywords:

Organizational Learning, Decision Support, Marketing Information. ManagerialLearning, Stories, Storytelling

-2-.ompuier-baseddataandorganizational Icamina

Introduction

Making

sense of the business environment isbecoming

amore

important organizationaltask, as rapid organizational and technological changes increase environmental complexity and

dynamism

(Boynton and Victor, 1991). This task is facilitated by thesame

phenomenon

thathas increased its importance

—

the computer. Organizationsnow

have access to detailed dataon

their operations captured by theirown,

and

sometimes

their customers', transactionprocessing systems. These data can play an increasingly significant role in organizational

learning, by helping

managers

both to better understand the effect of their actions.These

managers

can then reactmore

rapidly and accurately to changes in customer needs orcompetitor actions.

While

many

organizations are investing largeamounts

ofmoney

to provide computer-based data to their managers, little isknown

abouthow,

or even whether,managers

use thesedata to learn about the business environment.

The

goal of this paper is to explore the role ofcomputer-based data in organizations' understanding of their world. Since organizations learn only

when

their individualmembers

learn (Simon, 1991;Nonaka,

1991), I will firstinvestigate

how

managers

learn about theenvironment and

organize their knowledge. I willthen explore the role of computer-based data in managerial learning. Finally, I will

examine

how

themanagers

share their insights both withinand

outside the organization.My

insights derive primarilyfrom

two

sources—

from

studies of cognition in practice carried out by anthropologists and organizational researchers andfrom

interviews with grocery product managers. Managerial understanding ofthe environment is aproblem

that can benefitfrom

study in situ—

through the examination ofhow

managers

use computer-based data as partof their day-to-day work. Since cognition in practice differs significantly

from

cognition inartificial settings

(Brown

and Duguid. 1991; Lave, 1988), insights providedby

andiropologists(e.g., Orr, 1990)

who

have studiedproblem

solving in the workplace and by organizationalresearchers

who

have observed managerial cognition (e.g., Isenberg, 1986) in practice willhelp us understand the role ofcomputer-based data in managerial learning.

The

examination of this research is supplementedby

interviews carried out withproduct

managers

in grocery product manufacturers.Most

of the data for this papercome

from

interviews with six productmanagers

andtwo

information support personnel at Butler', arelatively small (sales under $2(X) million), independently run subsidiary of a major grocery

manufacturer.

These

interviewswere

conducted as part of a larger study of the use otcomputer-based data by product

managers

at five grocery manufacturers (Goldstein and Cho,computer-baseddataandoreamzationalleamine

1991; Goldstein. 1990; Goldstein and Zack. 1989). TTiey focused on

how

the productmanagers

used anew

data source—

purchased data collected from supermarket scanners—

andwhat

they learnedfrom

their analyses.The

visit took place sixmonths

after Butler purchasedscanner data for the first time and three

months

after itbegan

using the data as part ofcompany-wide

state-of-the-brand reviews (presentations to seniormanagement

on the status ofeach Butler product).

Product

managers

are responsible for developing marketingprograms

(e.g.,consumer

promotions) for a particular product line (e.g.,

Duncan

HinesBrownie

Mixes).They

setprices, plan marketing activities, introduce

new

product varieties, and monitor competition.Computer-based

data play a key role in product managers' understanding of theirenvironment

(McCann,

1986).These

managers

integrate information produced by their f~irmon

sales,shipments, and inventory, with purchased data

on

their and competitors' performance.The

data available to productmanagers

greatly increasedwhen

supermarket scannerdata

became

available. Butler purchased, for its product managers, monthly data for each offifty U.S. regions

on

each category (e.g., baking mixes) inwhich

thecompany

sold products.These

data included retail price, salesvolume

in dollars and units, and promotion activity(e.g., percentage ofmerchandise sold in supermarkets with an end-aisle display or with a large

or small ad in a supermarket circular).

These

datawere

for each item in the category(including both Butler

and

competitor products) with a unique Universal ProductCode

(e.g.,Duncan

HinesDeluxe

Brownie

Mix). Butler productmanagers

could access hundreds ofmegabytes

of data.By

analyzing scanner data, productmanagers

could increase the accuracy and timeliness of the feedback they receive about causal relationships in the marketing environment.They

could better understand the impact of the4Ps

of the marketingmix

—

price, promotion, place, and product

—

on

sales for theirand

their competitors' products.The

Role

of

Stories

inManagerial Learning

Researchers have proposed several

frameworks

to describehow

people organize their understanding of their world. People have scripts(Schank

and

Abelson, 1977) that containevent sequences for frequently occurring actions, for

example

ordering a meal in a restaurant.They

haveschema

(Minsky, 1975) that hierarchically structureknowledge

about a given topic basedon

its attributes, forexample

the characteristics of birds and of a specific type of bird.In addition, people have stories to organize their

knowledge

about experience (Schank, 1991).Stories are a type of narrative that contain settings, characters, a plot

—

with aproblem

or conflict and its resolution (Bower, 1976).

They

candescnbe

one incident or an agglomeration of several incidents. Stories also have a moral—

a rule, lesson,theme

or-4-computer-baseddataandoreanizatiotialieamina

general inference

—

that the person has derivedfrom

the story. This moral is used tounderstand current events (Martin, 1982).

When

a person hears a story, he tnes tomatch

thatstory (and its moral) to one he already knows. If he tlnds a match, he believes that he

understands the story (Schank, 1991).

There

isample

evidence that people maintainsome

of their work-relatedknowledge

asstories.

They

use stories to understand their world both within and outside the organization.For example, senior

managers

develop a plausible understanding of current events bycomparing them

to stories of specific previous events (Isabella, 1990; Isenberg, 1986). Inassessing the reasoning behind a competitor's early

announcement

of anew

product, anexecutive relates it to stories she

knows

about previous early product announcements. Shemight

remember

a story about acomparable announcement

by anothercompany

one yearearlier.

The

lesson of that storywas

that the earlyannouncement was

a market signal.Therefore, she

would

determine that the currentannouncement

served thesame

purpose.Similarly, photocopier technicians recall stories of previous repairs as they diagnose and

correct copier malfunctions (Orr, 1990). Stories are also used

by

workers in other cultures.Midwives

in the Yucatan recall and retell stories of births to determinehow

to handle difficultdeliveries (Jordan, 1989).

In

my

interviews with product managers, they recalled stories about the impact ofchanges in the

4Ps

of the marketingmix on

sales for theirand

competitors' products. For example, amanager

might recall a story about a$10

per case wholesale price reduction,whose

setting

was

the Phoenix region last September.The

story's characterswould

be consumers, supermarket buyers, competitors, andmembers

of the organization's sales force. Its plotwould

be a description of the rationale behind the price reduction (was it in response to acompetitor's action?) and the reaction to it by the sales force

(how

aggressively did theycommunicate

thechange and

its rationale to buyers?),by

buyers(how

much

did they purchaseand did they pass the savings onto consumers?),

by

competitors (did theymatch

thereduction?),

and by consumers (how

did it affect retail sales?).The

moral of the story mightbe that a

$10

price drop in Phoenix should only be used to increase purchases bysupermarkets, since they

do

not pass the savings onto consumers.As

a second example, consider this story toldby

a Butler productmanager

about acompany

that recently introduced a line that directlycompeted

with her product:[The

competitive line]bad

better distribution. Thiswas

their Gist refrigeratedproduct

and

theypaid

top dollar to get into the dairy case, butnow

they're having problems.They

are losing distribution in the West Coastand

incomputer-based daiaandoraamzationalleaminc

have

three strongand

one

weaA' item.We

also have better salesper

pointof

distribution. (Sales volume

per

store in which the itemsare carried./In this story, the

main

characterwas

acompany

—

the competitor. Other charactersincluded Butler

and

the supermarketsm

the various regions.The

settingwas

the U.S. grocerymarket at the time of the product introduction.

The

plot described thecompany's

attempts toconvince supermarkets to stock the four items in its

new

product line.The

story hadtwo

lessons: 1) the competitor is not doing well with this

new

product and is vulnerable; 2)therefore. Butler's saJes force should attempt to convince the supermarkets to

swap

outsome

or all ofthe competitor's items

and

stockmore

of Butler's items.Another

key characteristic of theabove

story—

and

product managers' stories ingeneral

—

is its detail.Not

onlydo

we

know

that the competitor paidmoney

to thesuf)ermarkets to get

them

to stock itsnew

product,we

alsoknow why

—

itwas

thecompany's

first dairy product and they

were

committed

tomaking

it a success. This detail increases the story's impact (Martin. 1982).When

compared

to abstract information, people both can recalldetailed stories

more

accurately (Reyes.Thompson

and

Bower,

1980) and aremore

likely toact u{X)n

them

(Kahneman

and Tversky, 1973; Borgidaand

Nisbett. 1977).Managers'

Use

of

Computer-Based

Data

to

Confirm and

Modify

Stories

Stories play an important role in

how

a productmanager

changes his understanding of the marketing environment through his analysis of computer-based data.When

a productmanager

studies computer-based data, he is attempting to relate it to stories heknows

about his productand

its environment. Consider a productmanager

who

examines

the latest scanner data and finds that both sales in Seattlewere

down

by

15%

and

that the city's largest supermarket chain raised the retail price of his productby 10%.

The

productmanager

would

try to

match

this data to stories about previous price changes.The

manager

might recall a story about the last time thesame

chain raised its price, or he mightremember

the impact of price increases by similar chains in Seattle or in other cities.The

productmanager would

saythat he understands the data, if they confirmed

one

of his stories. If themanager were

surprised by the data, he

would

try tomake

sense ofthem

—

at thesame

time modifying one ofhis stories.

Analysis of computer-based data plays a key role in the product managers' sense

making

process. It provides theraw

material they use to confirm or modify their stories.Product

managers

at Butler used scanner data to learn about the impact of changes in the4Ps

of the marketing environment

on

keyoutcome

measures, such as salesand

market share, foroorapulfir-based dataand orcamzauonailearning

Product

managers

noted that analyzing computer-based data helpedthem

monitor the environment^. Tliey tracked sales, distribution, price,and

promotions for their product and itskey competition.

They

often focused their attentionon

new

products ornew

varieties.Product

managers

studied the country as awhole

and important markets—

usually either markets that accounted for a large proportion of sales ornew

or test markets for Butler or acompetitor.

They

analyzed data to evaluate theirperformance

and to anticipate questionsfrom

superiors.

One

product manager-^ discussed the arrival of monthly market share data: Thedata is hand-deliveredto thepresident[ofthe subsidiary], the executive vice president, the directorof

marketing,and

theproduct managers. It arrivesat10

AM.

on

a Tuesday. People wait tor themailperson. It'sprettyintense.The

managers

tend to look at market share tor the total U.S.and

tor atew

keymarkets. I

oHen

get notes fromthem

asking, 'why did thishappen?

what'sgoing

on?' It'smy

job

toknow

thatour

Den\'ernumbers

are off. because our competitor ran a coupon.By

2 P.M.

that day. a report ison

the deskof

the division president at corporate. It containsmarket

share data plus trends torthe year.

If the

manager

just tracked trends but didno

further analysis, hewould

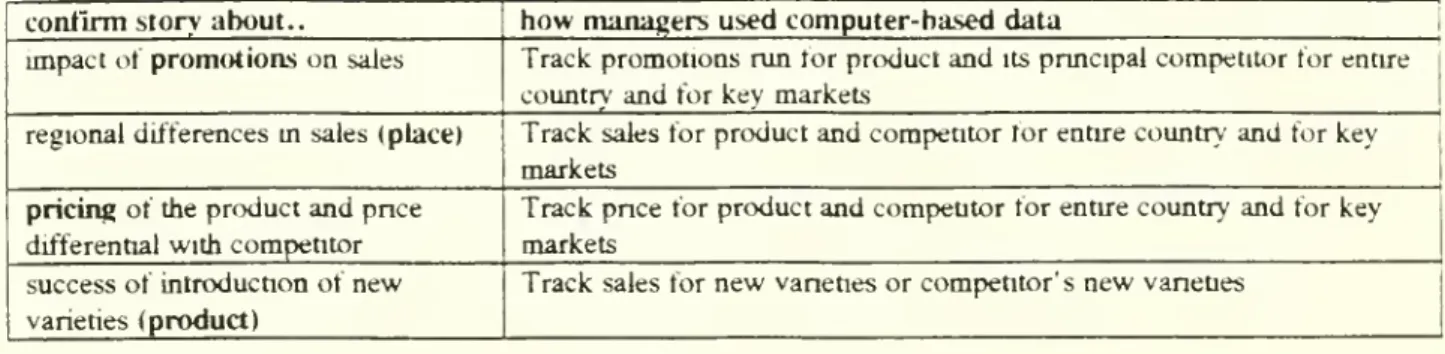

say that he understood the data and learned nothing new.These

data contirmed one his stories about the product and its environment (see Table 1). For example, one productmanager

closelyfollowed the introduction of a new,

and

relatively spicy, variety of his product line. In hisanalysis of the previous month's scanner data,

two

of his storieswere

confirmed. First, hefound that sales for all varieties increased

11.1% and

sales of thenew

varietywere up 11%.

In discussing this

new

variety, he noted that itwas

'tracking'—

selling as well as the averagevariety. Hence, these

new

data confirmed a portion of his story about thenew

variety. Second, he noted that thenew

varietywas

selling best in the Southwest. This contirmed oneaspect of his story about regional differences in

consumer

tastes—

thatSouthwestemers

preferspicier foods.

Frequently an event occurs that is surprising to a manager.

The

event is "discrepantfrom

predictions" and hence "trigger[s] a need for explanation" (Lxjuis, 1980, p. 241).The

manager

has decided to 'notice' the event (Starbuckand

Milliken, 1988).She must

switchfrom

monitoring,which

is characterized as amore

automatic or scriptedmode

of cognitive^Rockart and De Long (1988) also note that computer-based data play an important role in monitoring the

environment.

^This manager was not at Butler, butwas atone of the company's that participated

m

the first phase of this study.-7-;omputer-baseddataandorganizational learning

TABLE

1:USING

COMPUTER-BASED

DATA TO CONHRiM

MANAGERS'

STORIES

compuler-baacddalaandorcamzatiunalIcamine

among

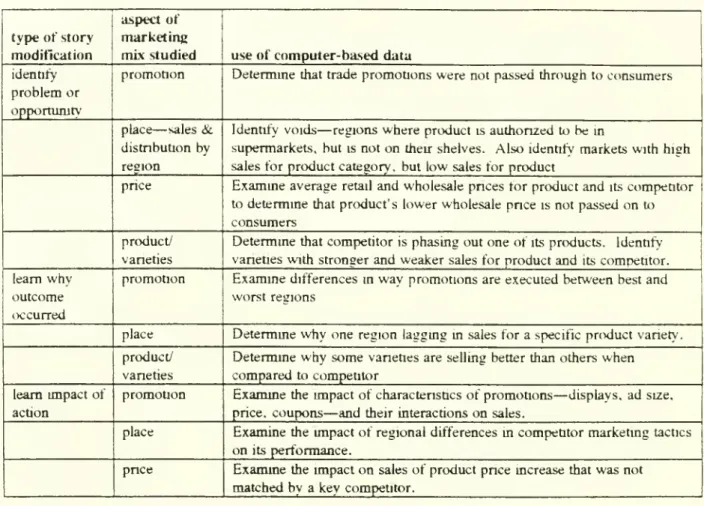

these elements on product sales. Tlie followingexample

illustrates the processfollowed by one product

manager

as she analyzed computer-based data and modified herstories about the impact

on

sales of promotions.One

Butler productmanager

was

surprised that her winter holidaypromotion

was

notas effective thisyear as theyear

before.Her

hunch was

that thegrowth

inprivate labelproducts [products

marketed under

thesupermarket'sown

labelJover the past year reduced the impact

of

her promotions.She

attempted to verify thishunch by comparing

scanner dataon

sales of her product tor thepromotion

period in regions thathad

strong private label sales with data torotherregions.

She

foundthat overallherpromotion

was

less elective in regionswith strong private labelsales.

While carrying out her analysis, the

manager

noticed that there were largedifferences in the effectiveness

of

her promotionsamong

those regions withstrong private labelsales. This

prompted

her to investigate further.She

lookedwithin those regions

comparing

regions in which herpromotion

was

effectivewith those in which it

was

not. Themanager

found thatwhen

the supermarketswith private labels

promoted

their products during the weeks right before theThanksgiving

and

Christmas holidays theirpromotions

were very effective atgenerating increasedsales, otherwise they were not.

The product

manager modiSed

her storyabout

the impactof

promotionson

the salesof

her product,adding

that selecting the appropriateweek

forpromotionswas

critical.She

explained thisphenomenon

by

noting that her productwas

purchased

to be eaten with holiday mealsand

that itwas

a relatively expensive,impulse purchase.

Hence

the promotions weremost

effectivewhen

timed tobring theproduct to the purchasers' attention during the ^veek before they were

most

likely toconsume

it.The

above

example

illustrates that the story modification process is a relativelyunstructured one. It can be

viewed

as a dialoguebetween

the set of tools (including varioustypes of analysis of computer-based data) at the manager's disposal and her

knowledge

of theenvironment

and

ofhow

to use the tools.A

process referred to as bricolage by Levi-Strauss(1966)'*. In the

above

example, the product manager's toolswere

the specific analyses ofscanner data that she performed to test her

hunch

about private label products and toexamine

the differences

between

regions inwhich

herpromotion

was

successful and those inwhich

itwas

not.The

manager'sknowledge

about theenvironment

was

organized as stories about the impact of changes in the marketingmix on

sales.She

also possessed stories, gained from^Levi-Straussdescnbeshow thebricoleur(handyman)enters intoa dialogue with thematenalsavailabletohtm

computer-baseddata andoreanizationalleamine

TABLE

2:USING

COMPUTER-BASED

DATA TO

iMODIFV

MANAGERS'

STORIES

type ofstory

computer-baseddata andorganizationalleamine

as a dialogue

between

tools andknowledge

(Levi-Strauss. 1962) and as a dialectical process inwhich

the gap "between resolution characteristics and information and procedural possibilities"is closed (Lave, 1988, p. 145). Levi-Strauss

and Lave

emphasize that both the use of toolsand the definition of the

problem

affect each other; each changes as the dialogue proceeds.In the example, the product

manager

mitially defined theproblem

as one of private labelgrowth

and hypothesized that the difference in the effectiveness of her holiday promotion could be explained by the increase in private label sales.The

tool she used to test herhypothesis

was

an analysis of scanner data inwhich

shecompared

the impact of her promotionin regions with strong private labels with its impact in other regions.

Her

analysis partlysupported her hypothesis.

As

her dialogue proceeded, themanager

redefined theproblem

as one of promotion timing. She tested anew

hypothesis—

supermarkets' promotionswere

more

effectivewhen

theypromoted

their private label product theweek

before either Thanksgivingor Christmas

—

using anew

tool.While

she still reliedon

scanner data,now

she focused heranalysis

on

the impact of promotion timingon

sales.A

secondexample

illustrates the use of multiple sources of information to learnwhy

a specificoutcome

occurred. Itshows

how

talking with peersand

market research can becombined

with analysis of computer-based data. Thisexample

also supports theview

that the story modification process can be characterized as a dialoguebetween

a set of tools and a problem.Another product

manager

at Butler did notknow

why

salesof

anew

variety—

light—

werepoor

in the South region. His Srst steptoward

creating a story toexplain this event

was

toask

the regional salesmanager.

The salesmanager

guessed that Southerners did not

consume

asmany

of

this variety as people inotherareas. With this serving as his tentative hypothesis, theproduct

manager

then entered into a dialogue. The Srst tool that

he

usedwas

an

analysisof

scanner data,

comparing

salesof

Butlerand

competitor productsof

this variety in the Southand

in other regions. Themanager

found that Southernersconsumed

about

asmany

of

the competitors' light variety as people in otherregions.

The

productmanager

thenredeSned

theproblem

asone

of

taste.He

came

up

with a

hunch of

hisown

—

Butler's light variety does not taste asgood

as itscompetition to Southern consumers. The

manager

testedthishunch

using anew

tool.

He

hired a market research6rm

to conduct blindtaste tests. These testsshowed

no

differencesbetween

Butlerand

itscompetitors in ffavor.The product

manager

finally accepted a third hypothesis—

that the Southregional sales force

was

doing apoor

job

convincing supermarkets to stockButler light variety. This hypothesis

was

supportedby

the scanner data, since-computer-baseddata andoreanizationalleamine

they

showed

that salesof

light were relativelypoor

in the South.He

believedthis to be true, because

he

believed therewas

no

plausible alternative.M

aresult

of

thissensemaking

process, themanager modiGed

his stories aboutregional differences in product sales,

about

the tasteof

his product,and

about

the effectiveness

of

the South regional sales three at introducingnew

varieties.In this example, the product

manager

first reliedon

discussions with the regional salesmanager

to develop a hypothesis about poor sales of the light vanety in the South.The

manager

used analysis of scanner data as his tool to test the tentative hypothesis.When

thishyf>othesis

was

not verified, he developed anew

one

—

that Butler light variety did not taste asgood

as its competition—

and used another tool—

a market research study—

to test it.The

manager ended

the story modification processwhen

he developed a plausible explanation,which

is consistent with Isenberg (1986)who

notes thatmanagers

strive for believableexplanations rather than optimal solutions.

As

in the first example, themanager

used a set of tools to close the gapbetween

theproblem

and a plausible solution.During

thisgap

closing process, theproblem

itselfwas

reformulated three times and the tools used to solve the

problem were changed

twice. Thisprovides further evidence of a dialogue in

which

both theproblem

and the tools use to solve itaffect each other.

They

both are modified as the process progresses.Finally, a third

example

illustrateshow

a productmanager

used a naturally occurringexperiment as a tool during story modification.

While

managers

routinely conduct experimentson

product taste or packaging using market research techniques, they also can usecomputer-based data to

examine

the impact of a natural experiment. Consider the followingexample:

A

third Butler productmanager

wanted

to understand what levelof

pricereduction

was needed

tomake

hispromotion

effective.Would

sales increaseabout

asmuch

with a99C

promotion

price as with a79C

price? Themanager

went

back

through scanner data.He

noted thatwhen

therehad

been both79C

and 99c

pricesaccompanied

by

features (ads in the supermarket circular)and

end-aisle product displays in the

same

regions at different times, sales weresimilar.

He

summarized

the lesson thathe

learned, stating,"We

learned thatprice is not

what

drives sales. It's getting the featureand

the display.We'd

move

justasmany

cases at99C

with featureand

a displayas at 79C."

When

productmanagers

analyze scanner data they increase the accuracy and timelinessof feedback they receive about causal relationships in the marketing environment. This is a

necessary condition to facilitate organizational experiments (Huber. 1991).

Each

marketingaction taken by a product manager, or by a colleague or competitor, can be

viewed

as anaturally occurring experiment,

from which

the productmanager

can gather valuable insights.12-compuler-base<ldataandomanuauonalIcamins

There

was

one type of tool missingfrom

the story modification process followed by theButler product managers.

They

performed almostno

statistical analyses to helpthem

make

sense of computer-based data. Tlie product

managers

had the training(many

hadM.B.A.

degrees) and the

computer

software needed to perform these analyses. Further,many

of thesurprises they encountered could be studied using statistical techniques. For example, product

managers

could have used regression to determinewhich

of several causal variables (price reductions, coupons, ads in supermarket circulars)were

significantly related to sales.They

could also perform analyses of variance to identify significant differences in sales

among

regions.Only

onemanager

tried to perform a statistical analysis.He

described his attempt:/

wanted

to find outwhat

drives salesof

my

product. I first tried running aregression, but it didn't tell

me

much.

Then

I decided tocompare

my

topand

bottom three markets. Ilookedat the full set

of

scanner measures. I found thatthe top three

had

much

deeperpace

cuts, they wereon

price reductionmore

otien. they

had more

AB

features [largerads in supermarketcirculars].The

simple analysis performedby

the productmanager

was

an easierway

forhim

to build arich, detailed story about the factors that affected sales of his product.

The

story that the productmanager

developedwas

alsomore

easilycommunicated

to his superiorsand

to the sales force as will be discussed in the next section.Sharing

Stories

Based on

Analysis

of

Computer-Based

Data

Managers

share the insights they have gainedfrom

analysis of computer-based data bytelling stories. Sharing insights is critical to

managers

who

interpret their environment byexchanging information and developing a

common

understanding (Daft andWeick,

1984). It is also critical to organizations, permitting multiple interpretations of thesame

eventand

richerorganizational learning (March, SprouU, and

Tamuz,

1991)and

facilitating thedevelopment

ofa

community

memory

—

a set of stories about the organizationand

its environment(Brown and

Duguid, 1991).

People in organizations like to tell and listen to stories. Telling stories helps workers and

managers

identify themselves as competent practitioners.As

story tellers, people inorganizations have a desire to share their achievements with others.

As

listeners, workersand

managers

like to hear stories; they have a "deepand

abiding interest in the characters and socialdramas

oftheir world" (Orr, 1990, p. 75).-13-computer-baseddata andoreamzationalleamine

Telling Stories to

Others

Members

of theOrganization

Product

managers

share stories that are basedon

their analyses of computer-based data.They

tell stories to each other, to their managers, and to sales managers. This story tellingmight be in response to a specific inquiry

from

a superior or a sales manager, in a formalreview of product performance presented to senior marketing

management,

or in less formal settings—

such as over lunch orcoffee.At

Butler,many

stories basedon

analyses of computer-based datawere

shared duringpresentations to

management.

The

vice president of marketing strongly encouraged theproduct

managers

to use thenewly

acquired scanner data as part of their state-of-the-brandreview.

The

managers

developed detailed stories about their product and its marketingenvironment

and toldthem

at the presentation.They

supported these stories withnumbers

from

their analyses, presented in chartsand

graphs. For example, themanager

who

developed the story about factors that affected sales ofhis product discussed at theend

of the last section supported this story with chartscompanng

sizeand

number

of price cutsand

number

of large supermarket circular ads in the three regions with the bestand

worst sales.Another

productmanager was

singled out by her peersand

superior for the quality ofher state-of-the-brand presentation.

She

told a story aboutwhy

sales of her product declinedsteeply over the last

two

years.She

stated that therewere

toomany

varieties of the product,all but a

few

were

doing very poorly,and

onlyone

was

selling well.The

productmanager

also observed that while her product

was

a fad foodand

experienced rapid salesgrowth

when

introduced about four years ago, the product category

was

now

agingand

hadbecome

more

price sensitive.

She

also noted that her productwas

performing well relative to itscompetition; it had higher per store sales. Finally, she pointed out that there

were

largeseasonal variations in sales

and

in the effectiveness of promotions.Based

on

this story, the productmanager

developed adetailed marketing strategy. Thisincluded dropping

many

product varietiesand

focusingon

the best selling one. She alsoeliminated all promotions

from

the first quarterwhen

saleswere

low.Most

importandy, theproduct

manager

attractedmanagement

support for her brand.She

stated:We

got corporatecommitment back

to the business, becausewe

could explain a great dealmore

to them.We

could tellthem

a story.We

could tellthem

whatwe

don't know. Before[we

analyzed thescanner

data/we

didn't evenknow

what

we

knew

and

what

we

didn't.We

gotcommitment

togrow

the business—

despite seeing a

20-30%

sales decline over the last2

years, because thepresentation

was

impressive. Before they were looking the otherway

when

Iwalkedin thehallway.

Now

they're letting usspend

money

behindthe business.-14-computer-baseddataandDrganizaiionai leanuna

There

was

a secondmajor

benefit of the state-of-the brand analyses.The

productmanagers

and their superiors found commonalitiesamong

the products.They

found andelaborated

on

patterns present in organizational events (Boje, 1991).The

productmanagers

developed a joint understanding about the impact of price, promotions, competition, and marketing

mix on

sales.One

productmanager

described the story that had been developed about promotions of Butler products through analyses of computer-based data by several of her colleagues:^o"-We

're a small brand. The trade [supermarkets} will only give us somany

promotionsper

quarterand

most

thingsneed

to be supported quarterly. Sincevve're

an

impulse-driven, trade-intensive category, we're very dependenton

promotions. Frankly,

we

havemore

thanour

lairsharebased on

oursize.We

learned thatwe don

't havedeep enough

pockets to support allof

our

product categones.

We

can'tsupport 14 categories,we

can support atmost

6.Theretbre.

we

willbedoing

jointpromotionsof

several products.Another

productmanager added

to the promotion story:We

found thatC

ads [the smallest ads in supermarket circulars]do

next tonothing.

Two

C

ads cost thesame

asone

A

ad

[the largest size ad], butdon

'tbring the

same

results.End

aisle displays withA

ads are50%

more

effectivethan

A

ads alone. Further, jointconsumer

and

trade aremuch

more

effectivethan separateones.

This learning led to a

change

inpromotion

strategy. Productmanagers

identified thoseproducts that could be linked together with a joint promotion (through further analysis of

computer-based data). Brokers*

were

instructed to strive for larger 'A' adsand

not toparticipate in

'C

ads.They

were

also instructed tomake

trade promotions (price reductions to supermarkets) contingenton

getting bothend

aisle displays andA

ads in circularsand

to time promotions to coincide withcoupons

forconsumers

that appear in free-standing inserts inSunday

newspapers.Official Stories

Told

to PeopleOutside

theOrganization

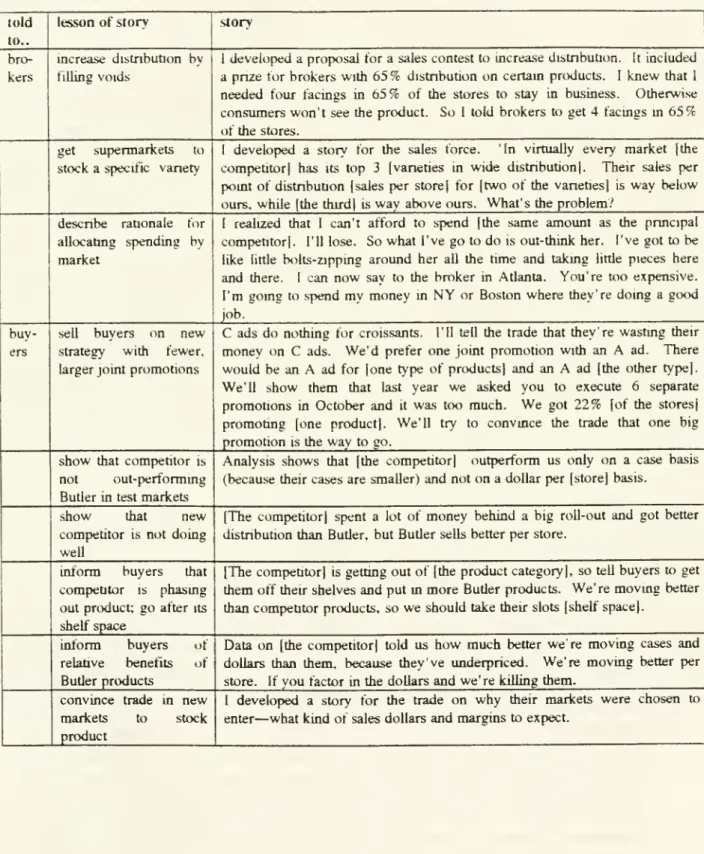

The

productmanagers

also developed 'offical stories' (Schank, 1990) to describe the marketing environment to people outside of the organization—

brokers and supermarket buyers (Butler's customers).These

storieswere

not used tomake

sense of the environment. Rather,they

were

used to enact change (Boje, 1991).The

official storieswere

often versions of thestories developed for

management

or peers.They

were

also supported by charts and graphsobtained

from

analyses of computer-based data. Since brokersmet

with supermarket buyers^Butler sold itsproduct through independentregional brokers, notadedicated sales force.

compuier-hased dataandorgani7^iionalleanuns

primarily to convince

them

to participate in apromotion

or to discuss shelfspace (facings), theofficial stories told to brokers and supermarket buyers involved

explainmg

changes inpromotion strategy,

oblainmg facmgs

for anew

or existing product, or defending shelf spacefrom

a competitor's product. See Table 3 forasummary

of these stories.A

marketingmanager

at anothercompany

descnbed

these stories as essential to'fact-based marketing.'

He

viewed

storytelling, supportedby

appropriate computer-based data, as an alternative to reducing price or other incentives to get a supermarket to stock a product orparticipate in a promotion. His view supports the idea that having

more

information is asymbol

of organizationalcompetence (Feldman and March,

1981) and. therefore,makes

the manufacturer 'look better' to the supermarket buyer.The

story about joint promotions describedabove

was packaged

for telling to thebuyers.

The

brokerswere

given thenew

'party line' about joint promotions andno

C

ads.They

were

also given thenumbers

(basedon

scanner data analysis) to supp>ort the story.One

Butler product

manager

described a part ofthis story:We'll tell the trade [buyers] that last

year

we

asked

you

to execute6

separatepromotions

in Octoberand

itwas

toomuch.

Our

promotion

[forone

product]was

executed in only22%

of

all supermarkets. We'll try to convince the tradethat

one

bigpromotion

[involving several product categories] is theway

to go.We'll

show

them

thatC

ads did nothing for [anotherproduct].We

preforone

joint

promotion

withan

A

ad

for[eachof

two

setsof

related products}.These

storieswere

sometimes

biased, since theywere

used to put Butler's products inas favorable a light and competitor products in as unfavorable a light as possible.

The

storiesabout competitor products always focused

on problems

(e.g., anew

product introductionwas

not successful, or the competitorwas

getting out of a certain product line).Sometimes

information

was

puqxjsely omittedwhen

it did not support the official story. For example, theproduct

manager

who

compared

his best and worst markets found thatmost

of his insights supported the official story about Butler promotions.He

did note, however, that smallerC

adswere

used relativelymore

frequently in regions with high sales of his product than inlow

sales regions.He

noted,"We

left that offthe chart, because it didn't add to our argument."16-computer-baseddata andorgamzaiional leamins;

TABLE

3:OFTICIAL STORIES

TOLD

TO BROKERS

OR

SUPERMARKET

BUYERS

tuld

oompuier-haseddataandorganizational learning

Discussion

The

Butler productmanagement

organization followed a four-step process in learningabout their

environment from

the analysis of computer-based data. First, amanager

exammes

the data

and

look for unexpected results—

findings that contradictone

ormore

of her stories about the marketing environment. If a surprise is found, themanager

carries out a relativelyunstructured, multi-stage process to

make

sense out ofthe unexpected result. This process canbe

viewed

as a dialoguebetween

the resultand

a set of tools at the manager's disposal(including analyses of computer-based data). Next, the

manager

tells the story to share herinsights with peers and superiors, developing a

common

understanding. Finally, themanager

creates an official story, that is used to 'sell'

new

marketing approaches to people outside the productmanager

organization—

the sales force and supermarket buyers.While

the productmanagers

made

extensive use of largeamounts

of computer-baseddata as they attempted to understand changes in their environment, they used almost

no

formalstatistical

methods

in their analyses. This issomewhat

surprising in that statisticalmethods

are designed to assist people insummarizing

anddrawing

inferencesfrom

large data sets.The

Butler product

managers

preferred to develop rich, detailed storieswhich

could be easily toldto and understood

by

their peers, superiors, and customers. In these stories, the data played asupporting role.

The

managers

used the data to confirm the stories or as a tool in storymodification.

They

also used the data tomake

the storiesmore

credible—

charts and graphsreinforced the

message

ofthe stories.Another

example

of the process of creating storiesfrom

large data sets, without usingcomplex

statistics, can be found in the financial pages of The Wall StreetJournal and TheNew

York Times. Reporters create stories that explain the changes in stock,

bond and

currencyprices that occurred the previous day. Consider the following story:

A

report thatshowed

only a small increase in inflationwas

ultimately ignoredby

creditmarket

participants yesterday as traders sold Treasury securitiesand

interest ratesmoved

higher. Pricesof

notesand

bonds

rosesharply immediatelya

Her

theGovernment

announced

that itsProducer

Price Index roseby

amodest

two-tenths

of

apercent lastmonth,and

onlyone-tenthof

apercentwhen

volatileenergy

and

food prices were excluded. But the gains, whichamounted

to asmuch

as^

pointon

some

securities, could not be sustained, as sellersemerged

at the higher price levels. Selling

of

short-and

intermediate-term noteswas

particulariyheavy. Rather than focus

on

thegood

inQation news,memories of

stronger

January

and

February

retail sales figures reportedon

Thursdaycontinued to linger. .Andpreliminaryresults

of

a Universityof

Michigan

surveyreinforced that

economic

recovery isunder

way. [Kenneth G. Gilpin. TheNew

York Times.

March

14. 1992].compuurbaseddata andorgamzauonallearning

The

reporter created a rich story to explain the change in thebond

marlcet.He

did not usestatistical analyses to correlate producer prices or retail sales

and

bond

prices. Rather, hecreated a plausible explanation

and

supported it with both several sets ofdata and text.This study has provided insights into

one

aspect of organizational learning—

how

organizations

make

sense out of largeamounts

of data—

and a perspectiveon

theorganizational learning process. Its findings are strikingly similar to those of

March,

Sproull,and

Tamuz

(1991)who

studiedhow

organizations learnfrom

single eventsand

smallamounts

ofdata.

Those

authors noted that organizations learnmost

when

the event is a surprise.When

confronted with single critical events, organizations create a detailed history to explain it.They

then share this history to allow for multiple interpretationsand

richer learning.The

theme

ofcreating and sharing stories runs through both studies.There are also imp>ortant lessons for researchers

who

study stories. Cognitive psychology researchers havecompared

the impact of rich, detailed stories with abstract numerical informationon

decisionmaking and

have found that peoplewere

more

influencedby

stories(Kahneman

and Tversky, 1973; Borgida and Nisbett, 1977). Butler productmanagers

used data to support their stories to influence their superiorsand

colleagues. Ratherthan studying the differences

between

abstract dataand

stories, it could bemore

beneficial toexamine

the degree towhich

adding supporting data to stories increases their credibility andimpact.

The

study also highlights the importance ofmaking

sense out of computer-based datawhen

managers

must

understand changes in the business environment.While

many

researchers and practitioners have discussed the benefits of organizational learning (e.g.,

Senge, 1990; Stata, 1989), the role ofcomputer-based data in organizational learning has been

all but ignored

by

information systems, functional area (e.g. marketing or operationsmanagement),

and

organizational behavior researchers''. Information systems researchers have focusedon

the value ofmore

sophisticated tools, such as expert systems, in facilitatinglearning

and

in storing organizationalknowledge

(e.g., Sviokla, 1990). In a similar vein,functional area researchers have tried to use computer-based data to develop

complex models

to explain underlying business processes (e.g., Kalwani,

Yim,

Rinne,and

Sugita, 1990).Most

organizational behavior researchers

seem

to recognize the value of storiesand

storytelling inorganizational learning, but they have focused their attention

on

the role of stories fortransmitting

norms and

values (e.g., Martin,Feldman.

Hatch, and Sitkin, 1983).Much

more

research is neededon

organizational learning in general andon

the role ofcomputer-based data in the organizational learning process.

We

need to better understandhow

^Zuboff (1988) isanotable exception.

computer-baseddataandorsanizational learning

organizations interpret their

environment

(Ruber, 1991) and the role of computer-based data inthis process.

The

techniquesemployed

by cognitive anthropologists (e.g., Hutchins. 1991.Orr. 1990. Lave. 1988) can play an important role in this process. Using these techniques,

we

can observe

how

managers

analyze computer-based data,what

they learnfrom

these analyses,and

how

they share thisknowledge

with others. Research is also needed to quantify the impactof computer-based data on organizational performance.

While

some

evidence exists thatinformation technology investment is linked to organizational

performance

(Harrisand

Katz.1991), little is

known

about the causality of this link.Through

the intervening process oforganizational learning,

we

can studyhow

an investment in information technology mightimprove

organizational performance.Finally,

managers

need guidance in designing organizations that encourage learning, specifically through the analysis of computer-based data.Some

researchers have suggestedthat organizations can

promote

learning by fostenngcommunities

of practice(Brown

andDuguid. 1991) and by building overlap into responsibilities

and

rotatingwork

assignments (Nonaka. 1991). Little isknown,

however, abouthow

to developand

share insights gainedfrom

the analysis of computer-based data.The

formal state-of-the brand analysesemployed

byButler is

one

mechanism

to encourage organizational learning. Othersmust

be found.At

thesame

time,we

must

consider the danger of 'analysis-paralysis.'With

toomany

formalmechanisms

in place, organizations might over-analyze data and hencemove

too slowly tomeet

changes in the business environment.At

a strategic level, organizationsmust

constantly adapt to survive in an environmentcharacterized

by

rapid product changes and the diversedemands

of a wide variety ofcustomers.

Toward

that end. theymust

gather, interpret, and disseminateknowledge

aboutchanging market conditions

and customer

needs. Analysis of computer-based data can play akey role in

managing

these organizational'knowledge

assets' (Boynton and Victor, 1991).The

more

detailed data that are collected about theenvironment

and factors that influenceorganizational performance, the

more

important it will be to use these data to provide insightsinto the changes that organizations might

make

and to evaluate the impact of these changes.This paper has provided initial insights into

how

organizations mightgo

about mining computer-based data toimprove

theirperformance.-20-compmer-baseddataandorgamzauonallearning

References

Boje,

David

J. (1991)."The

Storytelling Organization:A

Study of StoryPerformance

in an Office-Supply Firm," .Administrative Science Quarterly, 36. 106-126.Borgida, E. and R.E. Nisbett (1977),

"The

Differential Impact of Abstract Vs. ConcreteInformation

on

Decisions." Journalof

AppliedSocialPsychology, 7, 3. 258-271.Bower,

G.H.

(1976),"Expenments

on

Story Understanding and Recall," QuarterlyJournalof

Experimental Psychology, 28, 511-534.

Boynton.

Andrew

C. and Bart Victor (1991) ,"Beyond

Flexibility:Managing

the DynamicallyStable Organization," Califyrnia

Management

Review, 34, 1, 53-66.Brown, John

Seely and PaulDuguid

(1991), "Organizational Learning andCommunities

ofPractice:

Toward

a UnifiedView

ofWorking,

Learning, and Innovation."Organization Science, 2, 1, 40-57.

Daft, R.L.

and

K.E.Weick

(1984),"Toward

aModel

of Organizations as InterpretationSystems,"

Academy

of

Management

Review, 9, 284-295.elSawy,

Omar

(1985), "Personal InformationSystems

For

Strategic Scanning,"MIS

Quarterly, 9, 1, 53-60.

Feldman,

Martha

S. and J.G.March,

(1981) "Information in Organizations as Signaland

Symbol,"

Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 171-186.Goldstein,

David

K. (1990), "Information Support for Sales and Marketing:A

Case

Study ata Small

Grocery

Manufacturer," Informationand

Management,

19, 257-268.Goldstein,

David

K. andNamjae

Cho

(1991), "Environment, Strategy,and

theUse

Of

Computer-Based

Data:Case

Studies in ProductManagement,"

Marketing ScienceInstitute Report 91-132.

Goldstein,

David

K. and Michael H.Zack

(1989),"The

Impact of Marketing InformationSupply

on

Product Managers:An

Organizational Information Processing Perspective,"OfBce

Technologyand

People, 4, 4, 313-336.Harris, Sidney H. and J.L. Katz, "Organizational

Performance and

InformationTechnology

Investment Intensity in the Insurance Industry," Organization Science, 2, 3, 263-295.

Huber,

George

P. (1991), "Organizational Learning:The

Contributing Processes and the Literatures," Organization Science, 2, 1, 88-115.Hutchins,

Edwin

(1991), "OrganizingWork

by

Adaptation," Organization Science, 2, 1,14-39.

-•iimputerbaseddauandorganizaiional Ieamin2

Isabella.

Lynn

A. (1990), "Evolving Interpretations as aChange

Unfolds;How

Managers

Construe

Key

Organ

izalional Events,".Academy of

Management

JournaL

33, 1, 7-41.Isenberg, Daniel J. (1986), "Tlie Structure and Process of Understanding: Implications for

Managerial Action," in Sims.

Henry

P., Jr.. Dennis A. Gioiaand

Associates (Eds.). The Thinking Organization,San

Francisco,CA:

Jossey-Bass Publishers.Jordan. Brigdet (1989), "Cosmopolitical Obstetncs:

Some

Insightsfrom

the Training ofTraditional

Midwives."

Social Scienceand

Medicine, 28. 9, 925-944.Kahneman,

D. and A.Tversky

(1973),"On

the Psychology of Prediction," Psychological/?eweiv, 80, 237-251.

Kalwani.

Manohar

U., ChiKin Yim,

Heikki J.Rmne,

andYoshu

Sugita (1990),"A

PriceExpectations

Model

ofCustomer Brand

Choice," Journalof

Marketing Research, 27,251-262.

Lave, Jean. ( 1988), Cognition in Practice,

Cambridge,

England:Cambndge

University Press.Levi-Strauss, Claude (1966), The

Savage

Mind, Chicago:Chicago

University Press.Louis,

Meryl

Reis and Robert I. Sutton (1990), "Switching Cognitive Gears:From

Habits ofMind

to Active Thinking,"Human

Relations, 44, 1.Louis,

Meryl

Reis (1980), "Surpriseand

Sense-Making:What

Newcomers

Experience inEntering Unfamiliar Settings," .Administrative Science Quarterly, 25, 226-251.

March,

James

G.,Lee

S. Sproull, and MichalTamuz

(1991), "Learningfrom Samples

ofOne

or Fewer." Organization Science, 2, 1, 1-13.

Martin, (1982), "Stories and Scripts in Organizational Settings," in Hastori', Albert H. and

Alice

M.

Isen (eds.), Cognitive Social Psychology,New

York, Elsevier/North-Holland.Martin. Joanne,

Martha

S.Feldman,

Mary

Jo Hatch, andSim

B. Sitkin (1983),The

Uniqueness Paradox in Organizational Stories." .Administrative Science Quarterly, 28, 438-453.

McCann,

J. (1986), The MarketingWorkbench:

UsingComputers

for Better Performance,Homedale,

IL:Dow-Jones

Irwin.Minsky,

Marvin

(1975),"A

Framework

for RepresentingKnowledge,"

in P.H.Winston

(Ed.), The Psychology

of

Computer

Vision,New

York:McGraw-Hill.

Nonaka.

Ikujiro (1991),"The

Knowledge

Creating Orgamzation."Har\ard

Business Review, 69, 6, 96-104.computer-baseddata andon;anizational learning

Orr, Julian (.1990),

"Shanng Knowledge,

Celebrating Identity:War

Stories andCommunity

Memory

in a Service Culture, " in D.S. Middleton and D.Edwards

(Eds.) , CollectiveRemembering:

Memory

in Society, Beverly Hills,CA:

Sage Publications.Reyes,

R.M.,

W.C.

Thompson,

andG.H.

Bower

(1980), "Judgmental Biases Resultingfrom

Differing Availabilities of

Arguments,"

Journalof

Personalityand

Social Psychology,39, 2-12.

Rockart, John F. and

David

W.

De

Long

(1988), Executive Support Systems,Homedale,

IL:Dow-Jones

Irwin.Schank,

Roger

C. (1990), TellMe

a Story:A New

Look

at Realand

ArtiGcialMemory,

New

York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

Schank,

Roger

C. and Robert Abelson (1977), Scripts. Plans,and

Knowledge,

Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum.

Senge, Peter M., (,1990), The Fifth Discipline: The Art

and

Practiceof

the LearningOrganization.

New

York:Doubleday,

.Simon,

Herbert A. (1991),"Bounded

Rationalityand

Organizational Learning," OrganizationScience, 2, 1, 125-134.

Stata, Ray, (1989) "Organizational Learning

~

The

Key

toManagement

Innovation," SloanManagement

Review, 31, 63-74.Starbuck,

W.H.

and F.J. Milliken (1988), "Executives' Perceptual Filters:What They

Noticeand

How

They

Make

Sense," in D.Hambrick

(Ed.), The Executive Effect: Conceptsand

Methods

for StudyingTop Managers, Greenwich, CT:

JAI Press, 35-66.Sviokla. John J. (1990),

"An

Examination of the Impact of Expert Systemson

the Firm:The

CaseofXCON,"

MIS

Quarterly, 14, 126-140.Zuboff,

Shoshana

(1988), In theAge

of

theSmart

Machine,New

York: Basic Press.Date

Due

-r

9v

MIT LIBRARIES