LIBRARY OF THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF

TECHNOLOGY

CHARACTERISTICS OF OWNERS OF THRIFT DEPOSITS IN

COMMERCIAL BANKS AND SAVINGS & LOAN ASSOCIATIONS

67 -64

Henry J. Claycamp

July 1964

MASS. INST. TECH.

OCT

30

1964i

Characteristics of

Owners

of Thrift Depositsin

Commercial Banks

and Savings& Loan

Associations1 .

INTRODUCTION

Commercial banks

and savings and loan associations offer quite similarproducts to

consumers

seeking a safe, liquid, yield bearingmeans

of holding sav-ings. Both institutions offer safety of principal (nearly allcommercial

banks

and savings and loan associationsnow

have

federal deposit insurance),comparable

liquidity, and convenient

means

of depositing large or small amounts; yet therehave been

marked

shifts in the relative importance of thetwo

institutions asrepositories for

consumer

thrift funds.The recent spectacular growth of savings and loan associations and the decline in the relative importance of

commercial banks

as repositories forthrift funds has prompted major studies of the strengths and

weaknesses

of9

the

two

institutions. Results of these studies indicate thatcommercial banks

are at a competitive disadvantage

because

ofsome

of theirown

operatingcon-ventions and certain policies of regulatory bodies. In addition,

some

of thestudies suggest that aggressive marketing on the part of savings and loan associ-ations and important

changes

inconsumer

preferences and perceptionshave

been

instrumental factors in the shift of importance of the

two

institutions.However,

executives ofcommercial banks

and savings and loan associationsinterested in improving the efficiency of their marketing activities, as well as individuals interested in the impact of the form and

amount

ofconsumer

savings on purchasing behaviorneed

more information on a disaggregative level about the

-2-customers

of thetwo

institutions. Forexample,

it is important toknow

if thecus-tomers of the

two

institutionscome

from similar or dissimilarconsumer

groups.If they

have

unique characteristics, fluctuations ineconomic

conditions are likely tohave

differential effects on the flows of funds to the institutions. In addition, ascertainable distinct characteristics should lead tomore

precise definitions of marketsegments

and more efficient allocation of marketing effort by the institu-tions.On

the other hand, since the assets are almost perfect substitutes, it is possible that thecustomers

of thetwo

institutions are indistinguishable in terms of standardsocio-economic

variablesand

the assets areused

to fulfill similar roles in the portfolios of thetwo

groups.However, even

this conditiondoes

not preclude the possibility that significant differences exist in along important psychological dimensions. For

example,

both institutions have attempted todif-ferentiate their

images

and, as a result, important differencesmay

exist incus-tomers' personality needs, motives for saving, and expectations of

economic

con-ditions.

Knowledge

of these differences, if they can be ascertained, should provide important insights into the factors that affect choice of financial intermediaries andhave

a significant impact on the promotional policies of the institutions.In addition,disaggregative data direct from

consumers

will provide information aboutconsumers

who

hold both SLA's and CBA's. This group is particularly interest-ing since there is an opportunity cost equal to the differential in interest rates on the funds held inCBA's

andpresumably

there issome added

inconvenience to hold-ing funds in both institutions. Itwould

be important toknow

if these individuals

-3-allocate their funds equally to

CBA's

and SLA's, and if they concentrate proportion-ately more or less of their total funds to these institutions.This kind of data

can

also beused

to determine the relative effectiveness of the two institutions in exploiting the potential offered by their present customers.1 . 1 Objectives

This paper is an attempt to provide information

which

can beused

to testhypotheses

andanswer

questions such as those listed above. In particular, theobjectives are:

1) to provide

new

information about the role savings accounts in com-mercialbanks

and savings and loan associations play in the portfoliosof the following three

consumers

groups:a)

Group

C

- thosewho

hold thrift deposits incommercial

banks

but not in savings and loan associations, b)Group

S-those

who

hold thrift deposits in savings and loan associa-tions and not incommercial

banks, and c)Group

B - thosewho

hold thrift deposits in bothcommercial banks

and sav-ings and loan associations.2) to identify characteristics

which

discriminatebetween Groups

C, S, and B, anddraw

inferences relevant to the marketing policies of the respective institutions.3) to determine the relative importance of different types of variables as discriminators

between

the three groups ofconsumers.

1 .2

Design

of the Investigation1.2.1 The

Sample

-4-were

known

to hold eitherCBAs

or SLAs)was

one of several panelsdrawn

from largemidwestern

metropolitan areas in the study ofconsumer

savings carried on4 by the

Consumer

Savings Project.As

a part of theConsumer

Savings Project, informationwas

collected on a largenumber

of variables, ranging from standardsocio-economic

variables toamounts

held in specific assets and scores on psychological tests.The data

used

in this studywere

taken from the third re-interview of the panel, approximately ninemonths

after the initial contact. Corrections for inconsistencies in reporting during the ninemonth

period and for discrepanciesbetween

theamount

reported for a given holding and the actual

amount

according to the institution's recordswere

made

beforeany

analysiswas

undertaken.These

correctionsmean

that the data are likely to be more accurate than that obtained in

most

surveys. In particular,amounts

reported for specific assets are far less likely to be biased by under- and non-reporting than are reports of financial holdings derived frommost

surveys.1.2.2

Methodology

The first step in the analysis

was

classification ofeach

savings unit in the sample into one of three mutually exclusive groups -Group C, Group

S andGroup

B.In the analysis of the role of the specific asset in the portfolio of the

SU

,com-parisons

were

made

of themean

dollar holdings inCBAs

andSLAs

and of concentra-tion ratios ineach

of the respective assets. The concentration ratiowas

computed

5

as the ratio of the

amount

held in the specific asset to the total discretionary assets of the savings unit.

-5-In the analysis of the importance of specific variables in discriminating

between

the three groups,comparisons

between

themeans

ofeach

of the threegroups

were

firstmade

on a univariate basis, then all variableswere

included in a multivariatetwo-way

discriminate analysis.The discriminate analysis

was

performed in a step-wise fashion. That is, ina given run the program took all included variables into account in the first step

and

computed

the contribution ofeach

of the variables to the totalsum

of thesquares accounted for by the discriminant function.

Then

the variable contribu-ting the least to thesums

of squareswas

automatically deleted and the coeffi-cients recomputed. This process, including the analysis of variance,was

repeated until only one variable remained.

In order to

compare

the relative importance of certain classes of variables in discriminatingbetween

the three groups, all variableswere

classified inthree categories - socio-economic, asset, and psychological variables.

Socio-economic

variables included the age, education, and occupation of themain

wage

earner in the SU; the

SU's

gross 1959income

and total discretionary assets held at the date of the interview - spring, 1960.Asset

balances included theSU's

holdings in checking accounts,government

bonds, annuities, loans lent, stock, bonds, equity in real estate other than the place of residence, and equity in

businesses

operated by theSU

.

Psychological variables included

were

needs, asmeasured

by theEdwards

7

Personal Preference Schedule ; motives for saving; and expectations. The

needs

included were:

N-achievement,

N-deference,N-autonomy,

N-affiliation,

-6-and N-heterosexuality.

Motives

included were:M-old

age,M-education

ofchildren,

M-payment

of debts,M-purchase,

andM-emergency.

Expectationsincluded

were

X-prosperity during the next five years, X-recession during nextfive years, X-price level to increase during next five years, X-price level to remain constant during next five years.

1.2.3 Limitations

Obvious

limitations of the investigation are related to the nature of thesample. The sample

was

taken from:one point in time - early 1960,

one geographic region - the

midwest

United States,households

in a large metropolitan area,and

households

who

areknown

holders ofCBAs

or SLAs.Perhaps the

most

important limitation relates to the possible effect ofpromo-tion

done

prior to the study but not explicitly taken into account here. That is,the results found at this point in time

may

be in partcaused

by prior promotion. Thus, the variableswhich

distinguishbetween

the groupsmay

nothave

generality in situationswhere

other types of promotionhave

been employed.

Obviously

these limitationsmake

it important to validate the results reported here withnew

data beforemaking

broad generalizations.2. Results

2. 1

Comparative

Holdings ofCBAs

andSLAs

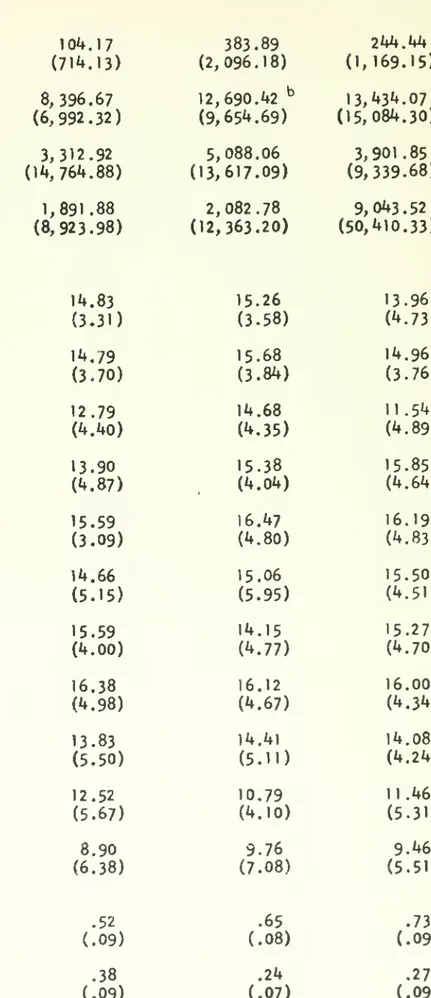

The data presented in Table 1 provide considerable information about the

way

the three

consumer

groups useCBAs

andSLAs

in their portfolios. In addition, in-ferencescan

bedrawn

about the nature of the market reached by thetwo

institutions and their relative effectiveness in exploiting the opportunities presented by theseGroup

TABLE 1

Absolute and Relative Holdings in Commercial Bank Accounts and Savings and Loan Association Accounts

-8-markets.

For

example,

comparison

of the average concentration ratios (i.e. ,$CBA

or

SLA

'A total discretionary assets) indicates thatSUs

in the three groups tend to hold, on average, slightly over50%

of their total discretionary assets inCBAs,

SLAs, or a combination of the two. Although the variances of the three distribu-tions are large, the similarity of the

mean

ratios is striking. Similar results are also found if the concentration of funds in thetwo

assets iscompared

on a group basis. Forexample,

24%

of the total discretionary assets ofGroup

C

isconcen-trated in

CBAs,

27%

of the assets ofGroup

S is concentrated in SLAs, and24%

of the assets of

Group

B is concentrated in combination ofCBAs

and SLAs. The fact that the aggregate concentration ratios are approximately one-halfthe value of the average of the individual ratios indicates, as might be expected, that a large

number

of those with small total asset holdings tend tohave

highcon-centration ratios. Thus, the results suggest that there is little difference in the portfolio role assigned to

CBAs

andSLAs

byconsumers

who

choose

one or the other exclusively; and, contrary to a priori expectations,consumers

who

hold bothCBAs

and

SLAs do

notseem

to concentrate more of their funds in these assets than thosewho

choose

one type of institution exclusively.Viewed

in a slightly differentway,

these results indicate thatcommercial banks

have approximately the

same

effectiveness in exploiting the potential offered bySUs

who

holdCBAs

exclusively, as savings and loan associations have with their present customers.However,

the distribution of funds bySUs

inGroup

Bshows

that the average concentration ratio forCBAs

is approximately one-half of thesame

ratio for

-9-SLAs.

A

similar result is found for the aggregate ratios, i.e. , only8%

ofGroup

B's total assets are in

CBAs

and16%

are in SLAs. Thus, with the group that diversifies thrift depositsbetween

thetwo

institutions,commercial

banksdo

considerably less well than savings and loan associations.

Although the variances are large and the distributions

skewed,

the resultsshown

in Table 1 also indicate that the average balance held inCBAs

is con-siderably smaller than that heldin SLAs.Moreover,

since the denominator of the concentration ratio is total discretionary assets, it is apparent that theSUs

inGroup

C

have, on average, smaller savings to distributeamong

variousalterna-tives.

(Mean

discretionary assets for theGroups C,

S, and B are$11,814,

$23,186,$32,372

respectively.) Thus, the results indicate that thecommercial

banksrepresented in this

sample

appear to attract proportionately more of theSUs

with small savingsand

fewerSUs

with large holdings thando

savings and loan associa-tions.2.2 Characteristics of Holders of Thrift Deposits

The results of the preceding section indicate that there are close similarities

in concentrations of funds in the

two

assets and theremay

be important differencesin the financial capacity or potential of the three

customer

groups. In the follow-ing section the three groups arecompared

on all variables included in the study. 2.2.1 UnivariateComparisons

ofSU

Groups

TABLE 2

Characteristics of Owners of Thrift Deposits

in Commercial Banks and Savings and Loan Associations Variable

TABLE 2 - Continued

Assets (Continued) Bonds

Home equity

Real estate equity

Business equity Psychological Needs Achievement Deference Au tonomy Affiliation Introspection Oominence Abasement Nurtu ranee Change Aggression Heterosexual Ity

Motive for Saving Old age

Education of children

Group C Mean

TABLE 2 - Continued

Motive for Saving (Continued) Payment of debts

Purchase

Emergency

Expectations

Prosperity (Next Five Years)

Recession (Next Five Years)

Price Level Increase (Next Five Years) Price Level Constant

Group C Mean

-13-a

SU

holdingCBAs

and notSLAs

is more likely to be younger,employed

as a skilledor unskilled laborer, and

have

moredependents

living athome,

than is thehead

ofa

SU

holdingSLAs

and notCBAs.

SUs

inGroup

C

also have lessmoney

invested in stocks andhome

equity.SUs

in thetwo

groups are remarkably similar in terms of formal education, income,home

ownership, andchecking

account balances, expectations ofeconomic

and price conditions, and motives for saving.To

theex-tent that

CBAs

andSLAs

are held for the motives listed, the results indicate that both assets are indeed held for similar reasons. The differences inm-old

age andm-education

of children are consistent with the differences in theages

and familyof the

two

groups, i.e. , the younger group with larger families are lessconcerned

with saving for old age, and more

concerned

with saving for education of children than the older, smaller family groups.In general, differences in the

same

variables are found incomparing

C

with B, the major exception is in the expectation of a recession in the near future.Only

7 percent ofGrbup

C

expected a recession,whereas

31 percent ofGroup

B reported that expectation.Group

Swas

significantly different fromGroup

B only in terms of theautonomy-need

score.

In

summary,

univariatecomparisons

of the three groups indicate thatGroup

C

differs from

Groups

S and B on a limitednumber

ofdimensions

andGroup

S is very similar toGroup

B on nearly all dimensions.

-14-(at least in a statistical sense)

between

the groupsdoes

not preclude the possibility that a multivariatemodel

will yield highly significant differences. The multiple discriminant analyses describedbelow

is an attempt toovercome

the limitations of univariate comparisons.2.2.2 Multiple Discriminant Analysis

between

SU

Groups

Group

C

vs.Group

S - Table 3 provides asummary

of the results obtained inthe discrimination

between

holders ofCBAs

andSlAs

usingsocio-economic,

asset, and psychological variables.Discriminant functions utilizing both

socio-economic

and psychologicalvari-ables produced significant F ratios at the .05 probability level.

However,

the eight best psychological variablesaccounted

for over 26 percent of the totalVari-es

ance and

socio-economic

variables accounted for less than 16 percent.The predication

summary shows

the resultswhich were

obtained inthe attempt to predict a given

SU's

accountownership

based

on its characteristics and the coefficients derived in the discriminant function. Forexample,

adiscrimi-so

nant value (Z)

was

calculated for each/as a linear combination of theSU's

psycho-logical characteristics.

On

the basis of theSU's Z

value and a separately calculated qdecision 7r the

SU was

classified inGroup

C

orGroup

S.These

results also indicate that the psychological variables provide the greatestrelative gain in correct predictions over a rational best guess. For

example,

if oneknows

only that 34 of theSUs

are inGroup

S and 29 are inGroup C,

then the optimal prediction strategy—

guess

that everySU

is inGroup

S --would

result in 34/63 orTABLE 3

Discrimination Between Owners of Commercial Bank Accounts and Owners of Savings and Loan Association Accounts, Based on Socio Economic, Asset and Psychological Variables

Analysis of Variance of the Discriminant Function Variables

-16-54 percent of the

SUs

placed in the correctownership

group. Utilization of the information obtained in the discriminant analysis resulted in 45/63, or 71 percent predicted correctly -- a gain of 17 percentage points. Utilization of thesocio-economic

and asset variables produced gains of 8 and 2.5 percentage points,re-spectively.

In an attempt to derive the "best" discriminant function the last six variables eliminated in

each

of the three previous functionswere

combined

in acomposite

analysis. Table 4

shows

the last eight variables to be eliminated from the composite function and thesummary

of the results.The F value for the

composite

function is significant at the .01 probability level and over 36 percent of the variancewas

accounted

for by the 8 variables listed inthe table.

Using

these variables, theownership

ofCBA's

and SLA'swas

predicted correctly in 79 percent of thecases

-- a gain of 25 percentage points.Although average stock holdings

was

the last variable to be excluded in the stepwise analysis, at the eight variable step N-affiliation and clerical occupationmade

greater contributions to the explainedsum

of squares.Of

the eight final variables five are from the psychological category, two are from thesocio-economic

category and one is from the asset category. This result is consistent with the resultsshown

in Table 3; i.e. , psychological variables tend to be better discriminatorsbetween

SUs

who

own CBAs

and not SLAs, andSUs

who

own

SLAs

and notCBAs,

than other types of variables. This result is particularly interesting since univariate tests of themean

psychological scores failed toshow

any significant differences (at the .o5 level). Yetwhen

thesame

variableswere used

in a multivariate model, the endre-TABLEjjt

Discrimination Between Owners of Commercial dank Account* and Owners of Savings and Loan Association Accounts

Based on the Best Eight Variables DISCRIMINANT FUNCTION Variable Stock Clerical N-autonomy N-aff Illation N-heterosexual Ity Age N-achievement M-old age ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE Source of Variance Discriminant Function Remainder PREDICTION SUMMARY Group C Group S Total Mean Z Weiqht

-18-sult is highly significant

even

after corrections for lost degrees of freedom.An

additional and perhapsmore

usefulway

to look at the predictivepower

of the discriminant function is to

compute

the probability of an individualSU

falling in a given group, rather than

making

a binary prediction.In this

way

the full information provided by the function is utilized. In orderto

compute

the probability function theSUs

1individual discriminant scores are grouped into discrete class intervals and the proportion of

each

classowning

a given asset, sayCBAs,

iscomputed

and plotted against the mid-point of theZ

class interval. Figure 1, the probability function

computed

on the basis of thecomposite

discriminant function,shows

clearly thatnone

of theSUs

withZ

scoresof less than -2.76

owns

thrift deposits incommercial

banks, all of theSU's

withZ

scores greater than -2.16own

CBAs,

and the probability ofowning

CBAs

increases monotonicallybetween

thetwo

limits.This analysis also yields additional information. For

example,

since theZ

value is positively associated with the probability of

owning

savings accounts incommercial banks

and the coefficients foreach

of the variables in the functionhave

negative signs, it is clear that high values of the variables are positively associated with the probability of

owning SLAs

and negatively associated with the probabilityof

owning CBAs.

That is, highneeds

forautonomy,

affiliation, achievement, andheterosexuality are more closely associated with

ownership

ofSLAs

than withowner-ship of

CBAs.

Similarly, being older, having a clerical occupation, a motive ofsavings for old age, and large stock holdings are

more

closely related toSLA

owner-ship than toCBA

ownership.FIGURE 1

Probability of Owning Commercial Bank Accounts As a Function of individual Discriminant Scores

Probability of owning CBA I.OOt

.80..

.20..

Discriminant Scores

-20-It is important to note that this analysis

does

not provide information about the relationship of these variables and theamounts

held in thetwo

types of assets. In-deed, only$SLA

and $stock (r = .40), and$SLA

and age (r = .29)have

simple cor-relation coefficients greater than .14. (Of course, multiple correlation analysisbetween

dollar holdings and these variablesmay

yield better results.)In

summary,

the results of the discriminant analysisbetween

holders ofCBA's

and SLA's indicated (1) that psychological variables

seemed

to be better predictorsthan

most

other variables in discriminatingbetween

thetwo

groups, (2) the "best"model

incorporated all three kinds of variables, and (3) the best (composite)model

produced highly significant results (in a statistical sense) and

marked

gains in pre-dictive ability. It remains to be seenwhether

these results are operationally sig-nificant, i.e. , whether thesame

variables will predict theownership

of a differentset of

consumers.

Group

C

vs.Group

B - The resultsshown

in Table 5 are analogous to thosereported in Table 3, except for the substitution of

Group

B forGroup

S. In contrast to the former case,socio-economic

variables appear to produce more significant gains in predictive ability thando

other types.Moreover,

when

the best six vari-ables fromeach

of the separate analyses are incorporated in thecomposite

function, five of the last six variables to be eliminatedwere

from thesocio-economic

class. Contributions to the explained varianceby

each

of the fivewere

highly significant(e.g., self-employed occupation,

income,

professional occupation, and educationTABLE 5

Discrimination Between Owners of Commercial Bank Accounts Only

and Owners of Both Commercial Bank Accounts and Savings and Loan Association Accounts, Based on Socio-economic, Asset and Psychological Variables

Analysis of Variance of the Discriminant Function

TABLE 6

Discrimination Between Owners of Commercial Bank Accounts Only and Owners of Commercial Bank Accounts and Savings and Loan Association Accounts, Based on the Best Eight Variables DISCRIMINANT FUNCTION

Weight Variable Self-employed Income Profess ional Education Age Government Bonds N-ach ievement N-nurturance ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE a P(F)

<

.10 b P(F) < .05 c P(F) < .01 Mean Z Group C Group B .65229 -.00392 .60868 -.06400 -.01460 -.00056 .03707 .02723 .47914 -.84126

-23-Z

scoresbased

on the coefficients derived for the best eight variables enabled correctownership

predictions to bemade

in 78 percent of thecases

—

a gain of 25 percentage points over the "bestguess"

estimate. The probability function derived from theZ

scoresshows

that the function offers perfect discrimination at the extremes and, with the exception of one class interval, the gradient increases monotonicallybetween

the extremes. The signs of the coefficients suggest that concentration of fundsCBAs

rather than diversificationbetween

CBAs

andSLAs

is positively associated with selfemployed

and professional occupations and highneeds

forachievement

and nurturance; and negatively associated with income,education, age, and

government

bond

holdings.Group

S vs.Group

B -- Separate discriminant functionscomputed

forGroups

Sand B produced similar results to those found for

Groups

C

and S. That is,psycho-logical variables resulted in the greatest fraction of the variance accounted for

—

29 percent versus 8 percent for

socio-economic

variables and 7 percent for asset variables -- and the greatest gain in predictivepower

-- 27 percent versus 2per-cent for

socio-economic

variables and 3 percent for asset variables.Wien

the bestvariables from

each

categorywere

combined

in the composite analysis, all six of the psychological variableswere

still in the analysis at the eight variable step; and three of themost

important psychological variables in the S vs. B analysis(N-autonomy,

N-achievement

, N-heterosexuality) are also discriminatorsbetween

Groups

C

and SFIGURE 2

Probability of Owning Commercial Bank Accounts Only, As a Function of Individual Discriminant Scores

Probability of Owning CBA Only

1 .00

^

,80.. .60.- .40-- .20--30 *-*-» \ 1 \ 1- 1 1 1 \ •1 .00 70 .40 .10 + .20 Discriminant ScoresTABLE 7

Discrimination Between Owners of Savings and Loan Association Accounts Only, and Owners of Both Commercial Bank Accounts ana Savings and Loan Association

Accounts, Based on Socio-economic, Asset, and Psychological Variables

Analysis of Variance of the Discriminant Function Variables Socio-economic Assets Psychological Socio-economic Group S Group B Total Assets Group S Group B Total Psychological Group S Group B Total « P(F)

<

.05 Source of Variation Discriminant function Remainder Discriminant function Remainder Discriminant function Remainder Degrees of Freedom 10 115 9 116 8 51 Sum of Squares .0872 Mean Square .9128TABLE 8

Discrimination Between Owners of Savings and Loan Association Accounts Only, and Owners of Both Commercial Bank Accounts and Savings and Loan Association

Accounts, Based on the Best Eight Variables DISCRIMINANT FUNCTION Weight Variable N-autonomy Self-employed N-achievement X-recession N-nurturance Size of SU N-deference N-heterosexual Ity ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE Source of Variance Discriminant Function Remainder PREDICTION SUMMARY Mean Z Group s Group B Group S Group B Total .04400 .31358 2.42479 2.10540 .03560

-27-It is interesting to note that the

composite

function produced virtually no gain in the variance accounted for or in correct predictions over that obtained using the function with psychological variables. In fact, one lessSU

was

predicted correctly in the former analysis.The probability function

computed

from the individualZ

scoresshows

thatZ

is positively associated with the probability of concentrating funds in SLAs.However,

the function

shown

in Figure 3does

not approach and remain at the upper limit asdoes

the function forC

and S, andC

and B. That is, allSUs

withZs between

2.55 and 2.70, and 2.85 and3.00

own

SLAs

only; while only one third of those withZs

between

2.71 and 2.85own

bothSLAs

andCBAs.

The signs of the coefficients

show

that high scores onn-autonomy, n-achievement,

n-nurturance, and n-difference, n-heterosexuality are all

more

closely related toowner-ship of

SLAs

only than toownership

of both assets.Only

the expectation of recessionin the near future is

more

closely associated with diversifying funds in both assets than with concentration of funds in SLAs.3.

Summary

andConclusions

The results presented

above

provide at least first levelanswers

tomany

of the questions raised in the introductory section.First, it is clear that

commonly

used

variablessuch

as income, education, andhome

ownership

are of little value in discriminatingbetween consumer

groupswho

concentrate thrift deposits in

commercial banks

and thosewho

choose

savings andFIGURE 3

Probability of Owning Savings and Loan Association Accounts Only, a

As a Function of Individual Discriminate Scores

Probability of Owning SLA Only

1

.00-

.80--Discriminant Scores

-29-both proved to be important factors in the final discriminant function. Thus, the hypothesis about the

homogeneity

of thetwo

groups in terms of standard marketing variables is partially supported by the results of the analysis.It also

seems

clear that there are empirically verifiable psychologicaldiffer-ences

between

thetwo

groupswhich can

be obtained with an easily administeredpencil and paper test. This result

has

important implications for the marketing strategy of the institutions. If the differences in theneeds

found in this analysis are general it should be possible for marketing executives of the institutions todesign promotional

messages

to more effectively cultivate possible inherent advantages,For

example,

theneed

forautonomy

seems

to be particularly closely associated withconcentrating funds in SLAs.

Even

if theneeds

found important heredo

nothave

generality in other situations,these results clearly indicate that it is possible for an institution to easily ascertain personality differences in

consumer

groupswhich

may

be closely associated with dis-tinct market advantages.It is important to note that

none

of the saving motives proved to be important discriminatorsbetween

thetwo

groups (saving for old age motivewas

not significant at the .10 probability level). Thus, the motives included in this study are, in the net analysis, no more closely associated with one type account than with the other. This result indicates that theremay

be little competitive advantage to be gained by an institution appealing directly to these motives.

-30-amounts

held in other assetshave

little ifany

differential association withCBA's

and SLA's. Thus, from a portfolio point of view, both assets

seem

to play similar roles. This result is consistent with the motives for saving results.The results of the analyses involving

Group

B -- thosewho

diversify their thriftdeposits in both

CBAs

andSLAs

—

present an interesting picture.It is clear from Tables 6 and 8 that

SUs

inGroup

B are more likeGroup

S thanGroup

C

in terms of concentrations of holdings and financial ability. Yet themost

important variables in distinguishing

between Group

C

andGroup

B are themore

com

-monly used socio-economic

variables and themost

important discriminatorsbetween

owners

ofSLAs

only andGroup

B are psychological variables. Sinceowners

of bothCBAs

andSLAs have

low absolute holdings, as well as concentration ratios incom-mercial banks, these results indicate areas of important

weaknesses.

Forexample,

income, education, age, and

government bond

holdingswere

all negatively associated with the probability ofowning

CBAs

only.Similar conclusions

may

bedrawn

from the results of theGroup

B-Group

S dis-criminant analysis since savings and loan associations do less well, relatively speaking, with thosewho

diversify than they do with thosewho

hold only SLAs.In

summary,

the results of this study indicate that certain psychologicalvari-ables are important discriminators

between owners

of thrift deposits incommercial

banks

and savings and loan associations, but the best discriminantmodels

requireboth psychological variables and standard

socio-economic

variables.

-31-small sample size, there is evidence that both institutions

do

equally well in exploit-ing the opportunity presented by thecustomers

who

concentrate their thrift deposits, but savings and loan associationshave

a competitiveedge

withconsumers

who

diversify their holdings.The results found in the analysis of the concentration ratio's also strongly indi-cate -- as do the non-significant motives for savings -- that both assets play very Similar roles in the portfolios of those that hold them.

Finally, it is the author's opinion that although the specific variables found significant here provide intriguing

hypotheses

to be tested in real world marketing experiments,showing

that themost

effective discriminate functions involve easilymeasured

psychological variables is amore

important result than determination ofthe specific variables in the function. For these results suggest that

even

simple testsmay

provide quantifiable personalitydimensions which can

be related to im-portant marketing variables.FOOTNOTES

1. See, "Flows Through Financial Intermediaries," Federal Reserve Bulletin, Vol. 50, No. 5, May, 1964, pp. 549-557

2. For example see, Clifton H. Creps, Jr., and David T. Lapkin, "Public Regulation and Operating Conventions Affecting Sources of Funds of Commercial Banks and Thrift Institutions," Journal of Finance,

Vol. XVII, No. 2, May, 1962, p. 289;

David Alhadeff and Charlotte P. Alhadeff, "The Struggle for Commercial Bank Savings," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. LXXI I

,

February, 1958, No. 1, pp. 1-22.

Marvin Rozen, "Competition Among Financial Institutions for Demand and Thrift Deposits," Journal of Finance, Vol. XVII, No. 2, May, 1962,

p. 318.

3. A savings unit is defined as one or more persons living in the same

dwelling pooling half or more of their income and savings. A dwelling unit may, therefore, have more than one savings unit

k. The consumer savings project is a large-scale study designed to develop the methodology for collection of accurate financial information through the survey technique. See Robert Ferber, Collecting Financial Data by

Consumer Panel Techniques, (Bureau of Economic and Business Research. University of Illinois, 1959).

5. Total discretionary assets was defined as the amount of SO"s total savings minus equity in the home, checking account balances, currency, cash value of life insurance and present value of pension plans.

6. The two-way discriminate analysis is analogous to standard regression analysis in which the dependent variable is dichotomous. One can view

the process as maximizing the deviation of the means of the two groups away from a discriminate function rather than attempting to minimize

the deviations of the dependent variable away from a regression line. For a discussion of discriminant analysis see, R. A. Fisher, Contributions to Mathematical Statistics, (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1950),

pp. 184-90.

7. Alan Edwards, Edwards Personal Preference Schedule Manual, Revised, 1959,

New York Psychological Corporation.

8. The psychological tests were administered to 50 per cent of the original sample who were randomly selected from the total. Tests made on key variable indicate that there are no significant differences between

'

r—o

—

p 29. The decision Z is calculated as follows: Z, = .—

—

. IZ£ - Z* + 2 <rd 2(Z -Z ) c s P

p c b

Where: Z = mean discriminant score for Group C c

Z

s = mean discriminant score for Group S

<j2 = the pooled variances of the discriminant scores for each group

P

P = proportion of the observations in Group C P = proportion of the observations in Group S

William W. Cooley and Paul R. Lohnes, Multivariate Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1962),

pp. 117-18.

10. For an application of this technique in the prediction of innovative purchas ing -behavior see, Ronald E. Frank and William E. Massy, "Innovation and Brand Choice," (Paper presented at the American Marketing Association Winter Conference, Boston, Massachusetts,

3 nOflO

003

flbfi 40inmiIImi innmimimilini,nil

3

TOAD 003 ATT E4^

3 TOfl

0D3

flt.fi357

1751

«*IO

roeS M.I.T. Alfred

P. Sloan .M414 School of Management Nos.55-64 Workup- *>-ers. 5 .£». 3 TDflO

003

flbflMaL

^

im1 .UBft A"IE$ 3tOAO 003

flbfl577

mini

"-«

MET LIBRARIES 3 TOflO003

flbfl715

MIT LIBRARIES 3tOSO 003

flbfl707

&-^

67-^

3 nOflO003

ties flbfl bfli i ii 3 TOflO003

flbflt73

III

iii i -75-CM

72--kM

3Toao 003

an

t,T4 HlllVi8M"'fS°^"

fe.7fl / m'imiB"«lES3