Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

HB31

.M415working paper

department

of

economics

'R 1 1991CONTRACTUAL

FORM,

RETAIL

PRICE,

AND

ASSET CHARACTERISTICS

Andrea Shepard

Number

569January

1991

massachusetts

institute

of

technology

50

memorial

drive

Cambridge,

mass.

02139

CONTRACTUAL

FORM,

RETAIL

PRICE,

AND

ASSET CHARACTERISTICS

Andrea Shepard

Number

569January

1991

M.l.T.

LIBRARIES

j 1

19M'

CONTRACTUAL

FORM, RETAIL

PRICE

AND

ASSET CHARACTERISTICS

Andrea

Shepard

Massachusetts Institute

of Technology

and

Harvard

UniversityDecember

1990

This

paper

has benefittedfrom

conversations with Severin Borenstein, PaulJoskow

and Michael

Whinston and

suggestionsby workshop

participants at StanfordGraduate

School of Business.The

research hasbeen

supportedinpartby

agrantfrom

the Center forEnergy

Policy Research,Predictions derived

from

aprincipal-agent analysis ofthe manufacturer-retailer relationship arederived

and

tested using microdata on contractual form, outlet characteristicsand

retail pricesfor gasoline stations in Eastern Massachusetts.

The

empirical results are consistent withupstream firms choosing contracts that

have

strong incentive characteristics but less directcontrol

when

asset characteristicsmake

unobservable effortby

downstream

agents important.Manufacturers trade-off incentive

power

formore

direct controlwhen

observable effort isrelatively

more

important. Retail prices are affectedby

the identityof

the decisionmakerand

1.

INTRODUCTION

Vertical restraints

have

a longand

controversial literature in theeconomics

of antitrustpolicy.

They

have

a shorter but less controversial literature in positiveeconomic

theory1 . Inthis latter literature, vertical agreements areanalyzed as a responseto principal-agent problems.

The

upstream firm sells its output to self-interesteddownstream

agents for transformationand

resale. In theabsence

of

contractualrestraints, the agents' choices ofprice and/orquality oftenwill not

be

in the best interest ofthe upstream principal.The

purpose

ofthe contract is to alignthe interests ofthe agent with the interests of the principal.

There

is amodest

empirical literature addressing thisview

of vertical contracts2.Brickley

and

Dark

(1984) investigate the effect of monitoring costsand

reputation investmenton

the upstream firm's decision to operatedownstream

units as franchises rather thancompany-owned

outlets.They

find patterns consistentwith franchising toeconomize on

monitoring costsby

establishing the franchisee as a residual claimant atremote

outletsand

withcompany

ownership

when

thedownstream

firm has an incentive to free-rideon

the reputation of theupstream firm. Lafontaine (1988)

and

Norton

(1988) also report results suggesting thatmonitoring costs

and

moral

hazard affect the choicebetween

franchisingand

company

ownership. Ornstein

and

Hanssens

(1987) find evidence that industry-wide resale pricemaintenance agreements increase the retail price ofdistilled spirits.

Although

previous empirical studieshave

addressed the choice of price or contractualform

made

foreach outlet, theyhave

ingeneralbeen

hampered

by

a paucityof

outlet-level data.As

a result, theyhave

reliedon

variation in industry ormarket

averages to estimate a relationshipbetween

characteristicsand

contractual form. In general, the studies test for a relationshipbetween

theindustry proportionofoutietsoperatedunder

some

contractualform and

some

set ofindustry characteristics.The

theory invokedby

these studies,however,

makes

no

1

The

positive theory ofvertical restraints issummarized

in Tirole (1988) and Katz (1989).For

amore

institutional application ofprincipal agent theory to franchising seeRubin

(1978).2

There

isa related empirical literatureon

the effectof

asset specificity, or thepotential forexpost rent extraction

by

some

party to the agreement,on

contract choices. See, for example,Joskow

(1987).The

contractingproblem

addressed in thispaper

does not involve relationshipprediction about proportions. Indeed, in the absence of important (and unobserved)

heterogeneity across outlets, no

mix

ofcontractualform

shouldbe

observed3.

This study is an empirical test of the implications of principal-agent theory in

which

outlet-specific data appropriate to the theoretical predictions are used.

Data on

an outlet'scharacteristics, its retail prices

and

the contractunder

which

it ismanaged

are used toexamine

the relationships

among

the outlet characteristics, the upstream firm's choice of contracts, andthe agent's choice of retail price.

One

focus of the study is the upstream firm's choice oftheallocation of control rights (contractual form) as a function of the characteristics of the

downstream

asset. Thus, the observedmix

in contractualform

is tiedto observed heterogeneityin outlet characteristics.

A

second focus is the effect ofcontractualform on

the agent's choice of retail price conditionalon

asset characteristics. Differences in retail prices are tied todifferences in characteristics and the incentives

embodied

in the contractual form.The

application addressed here is gasoline retailing,and

the study exploits the facts thatprincipals (refiners) sell gasoline through variously configured stations

and

use severalcontractual forms. Variation in station characteristics lead to variation in the importance of

agent effort

and

the extent towhich

the relevant effort is observable to the principal.Because

an unconstrained agent generally will not choose the level ofeffort preferredby

the principal,contractual

forms

with strongperformance

incentives willbe

used at stationswhere

effort isimportant

and

unobservable.At

stationswhere

effort is observable, the refinermay

choose

acontractual

form

that allowsmore

direct control over observable effort but offersweaker

performance

incentives.Legalconstraints

on

contractingon

pricemake

thepriceand

effortproblems

asymmetric.Price isalways observable, but can

be

directly chosenby

theupstream

firm only at acompany-owned

outletwhere

providing incentives forunobservable effortmay

be

more

difficult.Holding

constant the quality

of

theproduct, retail prices willbe

affectedby whether

they are chosenby

the upstream or

downstream

firm.Because

agents will generally not chose the price that3

Gallini

and Lutz

(1990) develop a signalingmodel

inwhich

a choice variable for theupstream firm is the proportion of

company-owned

stores in the distribution network, and Lafontaine (1990) presentssome

related empirical results.The

standard principal-agent theoryinvoked in this

paper

and

in the bulk of the empiricalwork,

however,

requires outlet-levelmaximizes

upstream profit, the advantage ofdirect control over pricemay

offset concerns with unobservable quality.These

predictionsare tested using datafrom

acensus ofstations in Eastern Massachusettsthat include information

on

over1100 branded

stations. Consistent with the theory, pricesappear to

be

different—slightlylower~at

company-owned

outlets. Station configurations thatimply

output is sensitive to unobservable effort increase the probability that a contractualform

with strong effort incentives will

be

chosen. Conversely, configuring stations such that outputis

more

sensitive to observable qualityincreases the probability that a contractualform

grantingquality control to the upstream firm will

be

chosen.The

paper isorganizedas follows. Section 2presents amodel

of decision-making withinaverticalstructure

when

thereareinstitutionaland

informational constraintson

contracting.The

implicationsofthis

model

for thechoiceof

contractualform and

retailprice ingasolineretailingare discussed in Section 3.

The

empiricalwork

is presented in Section 4,and

concludingcomments

are offered in Section 5.2.

A

MODEL

OF

VERTICAL

DECISION-MAKING

This sectionoutlinesa

model

ofverticaldecision-makingwhen some

downstream

choicescannot

be

coveredby

contract.The model

is first presented in a general principal-agentframework

and

then, in Section 3, applied to theproblem of

gasoline manufacturersand

retailers.

The

empiricalwork

addresses only the choicesof

retail priceand

contractual form, but interpretation is facilitatedby

considering the context inwhich

they aremade.

Thus, themodel

alsoexamines

asset characteristicsand

effort choices.The

problem

facing the vertical structure canbe

analyzed as a three stagegame.

In thefirst stage, the upstream firm chooses the characteristics of the

downstream

asset that willmaximize

upstream profit givenmarket

conditionsand

subsequent play. In the second, itchooses thecontract that will inducepreferred behavior

by

thedownstream

firm conditionalon

the asset's characteristics. Finally, the

downstream

agentunder

contract tomanage

the assetchooses effort

and

retail price tomaximize

her utilitygivenmarket

conditionsand

the decisionsofthe upstream firm.

maximize

her utility given the market conditions she faces, the characteristics ofthe asset shemanages and

the contractual restraintson

her choices. Competition in thedownstream

marketis

assumed

tobe

imperfect. Otherwise, her priceand

effort choiceswould be

market-drivenwith

no

role for contractual restraints.4Some

of her choicesmay

be

specifiedby

contract, butsome

cannot be. In particular,some

dimensionsof

effort areassumed

tobe

unobservableby

the principal5. Let e

=

(el

,e?),

where

e1 is observableand

e2 is not. Retail price is observable,but laws against resale price maintenance will disallow contracting

on

price insome

circumstances.

Both

priceand

productqualityareobservedby

theconsumer, and

demand

fortheproductdecreases in price

and

increases in quality6. Quality is a function of asset characteristicsand

agent effort; given asset characteristics, quality increases in effort. Different assets

produce

different products,

and

these products vary in the extent towhich

their quality is affectedby

effort. Let

X

=

(X

l,X

2) index asset characteristics such that an increase inX

denotes anincreased sensitivity of product quality toeffort.

Then

anincreaseinX

1(X

2) denotesan

increasein the sensitivity ofquality to observable (unobservable) effort.

The

agent's utility isassumed

to increase in profitand

decline in effort. Lettingrepresent the contract

and

Z

represent relevantmarket

conditions, the agent'sproblem

canbe

written

max

U(e,p,0,X,Z),p,e

where U(*)

isthe agent'sutilityand

e isthemonetary

disutilityof

effort.Assuming

theX

and

8offered

by

the upstream firm in a take-it-or-leave-it contract allow the agent to achieve at leasther reservation utility level, the solution to this

problem

is the utility-maximizing effortand

4

This assumption is consistent with theapplication to gasoline retailing. Gasoline stations

are sufficiently differentiated

by

locationand

brand tohave

some

discretion in priceand

effort.See, for example, Slade (1986).

5

For

simplicity, choices are characterized as simply observable or unobservable. In fact,choices

may

be

observable but at a high cost or observable but not verifiable.6

Quality is either unobservable to the upstream firm or is a sufficiently noisy indicator of effort that contracting

on

quality cannot substitute for contractingon

effort.price:

e' = e(0,X,Z) (1)

p'

=p(6,X,Z).

(2)In the second stage, theupstream firm chooses

from

thesetofavailable contracts theone

that induces the agent to chose the principal's preferred price and effort given

X

and

Z.For

any

X

and

Z, there is a quality (effort level)and

retail price thatmaximize

upstream profits. Itis

well-known

that in the absence of contractual restraints, thedownstream

choice ofpriceand

effort will diverge

from

thisoptimum

if there are vertical or horizontal externalities7. In thepresence ofexternalities, the

problem

fortheupstream

firmisto design a contract foreach asset thatmaximizes

upstream profit subject to the incentive compatibility constraints impliedby

equations (1)

and

(2). In general, a contractmight

specify the termson

which

inputs aretransferred

from

upstream, the levelofeffortrequired forobservable dimensions, theretailpricewhen

contractingon

price is lawful,lump

sum

transfersand

monitoring rights.The

problem

facing the upstream firm can

be

writtenmax

Il(e\p',X,Z),

d

where

II(») is upstream profit.The

contract is a function of asset characteristics because they determine the effect ofagent effort. If, for example, the asset is designed to insulate quality

from

the agent's choice of effort (low X), theneed

for contractual controls for effort choice is reduced.On

the otherhand, if quality is very sensitive to agent effort (high X), then the contract will

make

some

provisions for influencing the choice

of

effort. If an asset is characterizedby

output verysensitive to observable effort (high

X

1), the contract will generallybe

more

complex,

specifyingagent behavior. If output is very sensitive to unobservable effort (high

X

2), a contract that7

See

Tirole (1988), Chapter4 and

the references therein.provides incentives will

be

preferred.The

profit-maximizing contract canbe

denoted6' = 0(X,Z). (3)

In the first stage, asset characteristics will

be

chosen tomaximize

profit givenZ, the setofavailable contracts

and

thedownstream

decision problem.Market

conditionssummarized by

Z

affect the optimal X. If, for example, finaldemand

is highly sensitive to quality of a particular type, anasset thatcanproduce

thatqualitywould be

chosen. Alternatively, ifdemand

is highly price elastic an asset that is cost efficient but perhaps limited in its quality potential

might be

preferred.The

profit-maximizationproblem

canbe

writtenmax

Yl(d',e',p',Z)X

and is solved

by

X'

= X(Z). <4

>3.

VERTICAL

RELATIONSHIPS

IN

GASOLINE RETAILING

In the context ofgasoline retailing, the upstream firm is the wholesaler and the agent is

the station operator.

The

wholesalermay

be

the refiner (e.g.Mobil

or Shell) or a local distributorwho

is suppliedby

therefiner. Inprinciple, thepresence ofan

intermediarybetween

refiners

and

operatorsmight

have

some

effecton

observed choicesand

theempiricalwork

takesthis into account.

For

simplicity,however,

this discussion treats all wholesalers as refiners.The

asset is a gasoline station atsome

location,and

its characteristics includewhether

it sells non-gasoline products or services (e.g. automotive service or convenience store items),

itsgasolinesalescapacity,

and whether

itsells gasoline full-service, self-service or both.Market

conditions include the traffic

volume

at the station's location,demand

elasticities (with respectOperator effort might include hours of operation, the level of service provided at full-service

pumps,

or supervision of repair service.The

contract canbe

conceptuallydecomposed

into the "contractualform"

and

the"contractual terms" both

of

which

are included in the 8 notation.The

form

establishes therights

of

control, whilethe terms set the levels for variables forwhich

control rightshave

beenallocated to the refiner.

For

example, the canonical franchiseagreement

reserves the choice offranchise fee

and

wholesale price to the upstream firm, but allows thedownstream

firm tochoose

retail priceand

effort. This allocationof

control rights is the contractual form.The

terms are the particular franchise fee

and

wholesaleprice selectedby

theupstream

firm.There

are three contractualforms

used in gasoline retailing:company-owned,

lessee-dealer

and

open-dealer8.Within

each category, standardform

contracts that vary across dealersonly in the contractual terms

predominate

9.For

example, a refiner typically will reserve theright to set station hours in all lessee-dealer contracts, but

may

assign different hours for different stations.Under

open-dealer contracts, the landand

the capital areowned

by

the station operator.The

refiner hasno

investment in the station.The

contractualform

allocates the control of thewholesaleprice to therefiner.

There

isno

rental or franchisefee. Decision rights over servicequality

and

retailprice are allocated to the station operator.The

only substantive constraintson

operator behavior are with respect to product purity

and

labeling. Operators, for example,cannot sell gasoline supplied

by some

other refiner inpumps

identified with the contractingrefiner

and

are required to monitor storage tanks for contamination and/or leakage.The

contracts also specify a

minimum

volume

of

gasoline the open-dealer operatormust

purchase.However,

theonly penalty for failing tomeet

theminimum

purchase requirement isterminationof the supply relationship.

Because

a terminated open-dealer operator can sign with anothersupplier, this penalty is relatively mild.

8

The

descriptions ofcontractualforms

isbasedon

conversations with refiners, wholesalersand

industry analystsand

material inNordhaus,

et al. (1983),American

Petroleum

Institute(1981)

and Temple,

Barkerand

Sloan (1988).9

There

may

be

some

interstate variation in contractualforms

in response to state lawson

At

stations operated under lessee-dealer contracts, the landand most

ofthe capital areowned

by

the refiner.The

operator is responsible forbuying the initial inventory of gasolineand

other products10.As

in the open-dealer contract, the contractualform

allocates controlover the wholesale price to the refiner.

The

refiner also sets an annual lease fee. In additionto

minimum

purchaseand

product purity requirements, the lessee-dealer contract allocates substantial qualitycontrol to therefiner; contractscan specify hoursof

operation, set cleanlinessand

landscaping standards, definewhat

typesof

non-gasoline products or servicesmay

be

soldon

the premises, require the lessee tobe

on-site a specifiedamount

of timeand

give the refinerthe right to inspect the station, observe operations

and

audit business records.The

stationoperator retains the right to set the retail price for all products.

The

rental is station specific in the sense that it is set to reflect thevolume

of gasolinesales: a

good

location for selling gasolinewillhave

a higherrent than abad

location.However,

theserents

do

notextract alldownstream

profit.One

reason forthis isthereturnfrom

ancillarysales.

Two

stations in equallygood

locations with respect to gasolinedemand

and

thesame

capital for gasoline sales usually are charged the

same

renteven

ifone

also has service bays to provide automotive serviceand

the other does not. Refinersmay

also charge a flat fee forproviding the capital for the ancillary service, but these fees are not station-specific. In the

above

example, the refinermay

charge the station with auto repair service a flat fee for eachservice bay, but every station with repair

bays

willbe

charged thesame

fee11.The

use ofstandardized fees of this type is a

common

practice in franchise contracts inmany

industries(Lafontaine, 1990).

Because

not all rent is extracted, terminationimposes

a real penalty. Similarly, refusalto

renew

thelease—which

may

have

a termanywhere

from one

to ten years—is a real penalty.10

Conversations with refiners and industry analysts suggest that the cost ofbuilding a

new

station in the

sample

areawas

approximately 1 milliondollars in 1987,and

the cost ofan initialinventory for a station with automotive service

was

less than $250,000.11

The

transfervalueoflessee dealer stations is evidence thatnot all thedownstream

profitisextracted.

The

Petroleum

Marketing

PracticesAct

of1978

gives operators with lessee-dealercontracts the right to sell the lease to another party

(who

must be approved

by

the lessor).Leases

have been

sold forsubstantial sums;$100,000

to$300,000

arecommonly

citedas typicalof the range.

This

means

the refiner has amechanism

for enforcing quality standardsand

theminimum

purchase requirement.

The

circumstances underwhich

a lessee-dealer operator can beterminated or not

renewed

are restrictedby

the federal PetroleumMarketing

PracticesAct

of1978.

While

refiners can refusetorenew

orterminate for failure tomeet

the termsof

the lease,they cannot refuse to

renew

or terminate at will.The

refiner retains the right to alter the station's characteristics without the consent ofthe dealer.At

stations operated undercompany-owned

contracts, all capital investment ismade

by

the refiner,

and

the operator isemployed by

the refiner. All the control allocated to theemployer

in standardemployer-employee

relationships is allocated to therefiner. In particular,therefiner maintains

ownership

ofthe gasoline untilit is sold to theconsumer

and therefore has the right to set the retail price. This is the only contractualform under which

the refiner can directly set the retail price12.The

operatoris a salariedemployee

whose

compensation

package

may

include an incentivescheme

typically tied to thevolume

of sales.The model

assumes

that the refiner chooses station characteristics, a reasonableassumption at

company-owned

and

lessee-dealer stationswhere

the capital isowned

by

therefiner

and

the contractualform

allocates to the refiner substantial quality control rights.At

open-dealer stations this

modeling approach

isless immediately appealing. Itcanbe

supported,however, by

arguing thatarefiner choosingto signan

open-dealercontractataparticular station couldhave

constructedan

alternative stationand

supplied it as acompany-owned

or alessee-dealer operation.

Given

this option, the refiner will enter an open-dealer contract only if thestationcharacteristics arethose

he

prefers givenmarket

conditions,and

the station characteristicsare such that an open-dealer contract is preferred.

12

There

is a long history oflitigation with respect to resale pricemaintenance

in gasolineretailing.

The

courtshave

consistentlyheld that refiners cannot setthe retailprice atany

stationnot operated

by

an employee. In particular, the courtshave

ruled that using acommission

contractual

form under which

legal title to thegasolineis retainedby

the refiner until sold to theconsumer

but the operator is notanemployee

does not give the refiner the right to setthe retailprice. See, for example,

Simpson

v.Union

OilCompany,

311 U.S.

13, 17-18. Itmay

notbe

coincidental that the

commission

contractualform

has virtually disappearedfrom

gasoline3.1

Contractual

Form

and

EffortAmong

the three contractualforms

there arecleardifferences in thepotential for directlycontrolling effort

and

forprovidingperformance

incentives.The amount

ofdirect effort controlallocated to the refiner is greatest with

company-owned

contractsand

smallest with open-dealercontracts.

So

for stations atwhich

themore

important effort dimensions are observable, thecompany-owned

contract shouldbe

attractive.For

unobservable effort,however,

what

matters isperformance

incentives. In thisdimension

company-owned

contracts are inferior toopen and

lessee-dealer contracts.When

greater operator effortincreases the

demand

for gasoline, operators with lessee-dealerand

open-dealer contracts gain the

mark-up

over wholesaleprice for each additional gallon sold. Further,for

some

non-gasoline products or services, these operators are true residual claimants.In contrast, iftheoperator receives only a fixed salary at

company-owned

stations, thereis

no

mechanism

for affecting unobserved effort.Some

refiners,however,

include an incentivescheme

in thecompensation package

for salaried operators.The

extent towhich

this approachis a

good

substitute for residual claimancydepends

on

what

observable indicators ofeffort areavailable. Ifa station sells only gasoline,

an

incentivescheme

based onlyon

gasolinevolume

can

be

agood

substitute fordirectly contractingon

effort. Indeed,any

readily metered productor service can

be

easily incorporated into an incentive scheme.But

then it is not correct toclaim these outputs involve unobservable effort, becausethere is

some

observableindicator thatis highly correlated with effort.

Some

services,however,

are difficult tometer

because theoutput is hard to define or can

be

easily disguisedby

the operator. In this case, effort isunobservable.

The

relationshipbetween

optimal contractualform

and

station characteristics issummarized

in thediagram.When

both observableand

unobservable effortare important (highX

1and

highX

2, respectively), lessee-dealer(LD)

contracts willbe

preferred because thisform

allows both control over observable quality

and

incentives for unobservable effort.With

highX

1and

low

X

2, the refiner shouldbe

indifferentbetween

the lessee-dealer andcompany-owned

(CO)

forms, bothofwhich

allow control of observable effort. In theopposing case (lowX

1and

highX

2) thecompany-owned

form

is dominated, but the refiner willbe

indifferentbetween

the lesseeand

open-dealer(OD)

forms. Finally,when

effort has little effecton

quality, the refinerHIGH X

2LOWX

2HIGH

X

1LD

LD =

CO

LOWX

1LD

=

OD

LD =

CO

=

OD

will

be

indifferentamong

the three forms.A

good example

of a service that ishighlysensitive to unobservable effort isauto

repair.

The

qualityof

repairwork

isnotoriously difficult to monitor; without

on-site supervision

by

amanager

with strongincentivesto

produce

highquality, shirking isunavoidable.

For

thesame

reason, it isrelativelyeasy foran operatortounder-report

auto repair profit.

An

incentivescheme

based

on

output or profit is not feasible. Residual claimancy through an open-dealer orlessee-dealer contract is a superior

mechanism

for inducing optimaldownstream

choices.Evidence

supporting thisargument

isreportedby

Brickleyand

Dark,who

find thatamong

thosefirms offering automotive repair,

96

percent of the outletswere

operated as franchises ratherthan as

company-owned

outlets.Some

non-gasoline output is less affectedby

unobservable dealer effort.Convenience

stores can

be

run inways

thatremove

those quality dimensions sensitive to unobservable effortfrom

the controlof

the operator. Inventory canbe

centrally planned, purchased, pricedand

distributed.

As

a result, the effectof

effort isreduced. Further, it is fairly easy tomonitor

thequality dimensions her effort can influence: cleanliness, spoilage

and

stocking shelves, forexample.

With

many

observable quality dimensions, refiners should prefercompany-owned

orlessee-dealer contracts to open-dealercontracts for stations with convenience stores.

With

littleunobservable effort input

by

the operator, refinersmay

be

indifferentbetween

company-owned

and

lessee-dealer contracts for convenience store stations. Finally, theremay

be

some

stationsat

which

operator effort has little effecton

demand.

A

station that sells only self-servicegasoline, for example, requires only

minimal

operator input.At

these stations, there isno

reason to suppose that

one

contractualform

willbe

preferred to anotheron

the basis ofqualitycontrol.

3.2

Contractual

Form

and

PriceContractual

form

will affect price as well as effort,and

the ability to set price directlyat

company-owned

outletsmay make

thisform

attractive to refiners .Because

a refiner's onlyinstrumentforextracting

downstream

profit atopen-dealer stationsisthewholesaleprice,he

willset thewholesaleprice forthose stations

above

his marginal cost.But

because a refiner cannotlawfully set station-specific wholesale prices,

he

must

then charge a wholesale priceabove

marginalcostatall hisstations.

Even

withoutthisconstraint, ifextraction ofdownstream

profit through rental orother fixed fees isimperfect, charging a wholesale priceabove

marginal costmight maximize

upstream profit. In either case, ifdownstream

competition is imperfect, theretail price decision of

downstream

agents willbe

affectedby

double marginalization: holding effort constant, the price chosenby

thedownstream

agent willbe

too highfrom

the refiner'spoint of

view

because theoperator's marginal return toreducing retailprice isless than thetotalbenefit ofprice

minus

unit productionand

retailing cost.When

the agent chooses both effortand

price, it is clear that the price she choosesand

the price the refinerwould choose

will notbe

the same, but it is not possible to sign the difference without further information about finaldemand

and

downstream

competition. Here,however,

the useof

minimum

purchaserequirements impliesthat the price chosen

by

the operator tends tobe

too high. In the absenceofquantity forcing, then, prices at

company-owned

outletswould be lower

than prices at otheroutlets.

Minimum

purchase requirements will limit the pricing discretionof

lessee-dealeroperators,

and

arecommonly

believed tobe

used for that purpose.They

are not a substitute,however,

for setting price.Minimum

purchase requirements are in effect over relatively longperiods of time

and

are not adjusted forminor

changes indemand

or supply conditions.As

aresult they are set

low enough

to ensure the dealer willbe

able tomeet

them under

a range ofconditions.

Observed

prices, therefore, couldbe

higher at lessee-dealerand

open-dealer outletsthan

company-owned

outlets despite the quantity forcing. This prediction is consistent withclaims

made

by

open-dealer and lessee-dealer operators thatcompany-owned

stations chargelower

prices(USDOE,

1980). Barronand

Umbeck

(1984) also find that a smallsample

ofstationsconverted

from

company-owned

contracts tosome

other contractualform

chargedpricesthat

were

lower, relative to nearby stations, before thechange

in form. If the absence of astrong enforcement

mechanism

reduces theeffectiveness ofquantity forcing atopen

dealerships,prices at these outlets

may

be

higher than prices at lessee-dealer outlets.3.3

Open-Dealer

Contracts

RevisitedThe

preceding discussion implies that open-dealer contracts should neverdominate

bothcompany-owned

and

lessee-dealer contracts. Ifeffort matters andany

dimension is observable,lessee-dealer contracts will strictly

dominate

open-dealer contracts. Ifeffortis unimportant, thesuperior price control availablewith

company-owned

contractswill leadrefiners topreferstrictlycompany-owned

contracts toopen-dealercontracts.Only

in theunlikely circumstance thateffortmatters but

no dimension

isobservable willan open-dealercontractnotbe dominated

by

anotherform.

Even

in this case, the refiner shouldbe

indifferentbetween

the lesseeand

open-dealer forms. Nonetheless, open-dealer contracts arecommon.

This apparent inconsistency arises

from

the assumption that themost

profitable contractfor the refiner results in a non-negative refiner profit. This need not

be

the case.There

willbe

some

locations atwhich even

the best contract will notproduce

anormal

returnon

therefiner's investment in land

and

capital. If the investment ismade

by

the operator,however,

it will

be

profitable for the refiner to supply gasoline to that station as long as his wholesalemark-up on

thequantity sold ishigher thanhis costofdelivering the gas. Thisarrangement

canbe

profitable for the operator if there aredownstream

rents that cannotbe

extractedby

therefiner

under

any

contract.Then

the total profit at the stationmay

be

highenough

to cover theinvestmentin land

and

capitaleven

though the refiner's share under an alternativearrangement

would

notbe.This situation will arise

most

commonly when

asubstantial shareoftheprofits generatedat the station

come

notfrom

gasoline sales butfrom

sale ofsome

ancillary product or service.At

a stationofthistype, the refiner's profitfrom

gasoline sales (through the wholesalemark-up

plus the rent) will

be

relatively small. Ifrent extraction is imperfect for the ancillary service,this additional

income

might

notbe

sufficient to bring the total return to anormal

level.The

operator,

however,

may

find the ancillary service extremelyprofitable, especiallywhen

she getsto retain the entire profit stream. Thus, stations that

have

a small gasoline sales capacityand

some

ancillary service aremore

likely tobe

open-dealer stations.Nearly all the stations in this country are built

by

gasoline suppliers rather than stationoperators. Sincerefiners

would

not build stations that could notbe run profitablyunder

the bestcontractualarrangement, these stations

must have

been profitable (atleast in expectation) for therefiner

under

lessee-dealer orcompany-owned

contractswhen

theywere

built13.Changes

inmarket conditions can subsequently

make

these stations unprofitable as a refiner investment,leading

him

to sell to anopen

dealer14.Because

these changes aremore

likely the longer thestation exists, open-dealer stations are also

more

likely tobe

older stations.3.4

Summary

of PredictionsIfthe

primary

concernoftherefineriscontrollingthedownstream

price,company-owned

stations

would be

thedominant

form.When

unobservable effort is important,however,

therefiner

may

trade control over price for effort incentivesproducing themix

in contractualform

actuallyobserved.

Within

amixed

distribution system, theprice atcompany-owned

stores willbe

different—and probably lower. If quantity forcing ismore

successfulunder

lessee-dealercontracts, prices at open-dealer stations will higher than prices at lessee-dealer stations.

The

company-owned

contract shouldbe

associated with stations designed to insulatequality

from

unobservable efforttherebymaking

theprice advantage ofthisform

relativelymore

important. Stations selling gasoline self-serviceonly

and

stationswhere

the ancillary service isaconvenience store rather than automotive service should

be

good

candidates for thecompany-owned

form. In contrast, the lessee-dealerform

willbe

associated with stationswhere

unobservable effort isimportant. Stations with automotive service will

be

runmore

profitablyunder a lessee-dealer contract than a

company-owned

contract.Finally, if open-dealer stations are those at

which

refinerownership

isno

longer13

In principle, arefinercouldbuild stations

he

intendsto sell immediatelytoanopen

dealer. Ifrefinerand

operatorhave

thesame

risk attitudeand

beliefs, the refinercould extract all futureprofit through the sale price. This

would be

particularly attractive if the refiner hassome

advantage in land acquisition

and

station construction. In fact,however,

this is not acommon

practice.14

The

federal PetroleumMarketing

PracticesAct

of 1978 requires that a refiner wishing tocease operation of a lessee-dealer station offer to sell the station to the current lessee.

The

refiner is not,

however,

obligated to supply the station after the sale.profitable, these stations should

be

olderon

average than the stationsowned

by

refiners.They

also

may

earn a substantial share ofincome from

an ancillary service forwhich

rent extractionisimperfect, suggesting thattheproportion

of

thestation's capacity devotedto gasoline sales willbe lower

at open-dealer stations.4.

THE

EMPIRICAL

MODEL

AND

RESULTS

Testing these predictions requires an econometric

model

that is responsive to the natureofthe decision

problem and

the limitationsofthe available data.The

empiricalwork

estimatesequations (2)

and

(3) taking into account the discrete nature ofthe observed contractualform

variable.

Because

the estimation strategy isaffectedby

dataavailability, this section begins witha description of the data

and

then specifies the empiricalmodel and

reports the results.4.1

Data

and

Sample

CharacteristicsThe

data arefrom

a cross-sectional census of all the gasoline stations in a four countyarea in Eastern Massachusetts that includes the

Boston

metropolitan area15.Data

on

stationlocation, ancillary services, gasoline brand, station capacity, service level (full or self)

and

contract typeare included foreach.

No

relevantinformationon

effortordemand

characteristicsare available.

Some

informationon market

conditions canbe

constructed using the dataon

station location.

Although

reported as a cross-section, data collection occurred over a twelveweek

period inthe firstquarterof

1987, duringwhich

the wholesalepricesofrefined petroleum productswere

slowly rising.To

adjust for wholesale price changes, theretail priceshave been

indexed usingweekly

fob wholesale price data for the Boston area16. Retail prices observedin

any

givenweek

are indexedby

the average wholesale price reported at theend

of thepreceding

week.

The

analysis is restricted tobranded

stations: Shell,Exxon,

Amoco,

Gulf,Mobil, Citgo,

Texaco and Chevron

in this sample. Descriptive statistics for thebranded

stations15

There

are a totalof

1527

stations in the four country area.The

analysis omits stationsina subsetoftheoutlyingareas, reducing the

sample

to1489

stationsofwhich

1130 arebranded

stations.

16

The

station-level datawere

collectedby Lundberg

Surveys, Incorporated.The

wholesaleprice data are

from

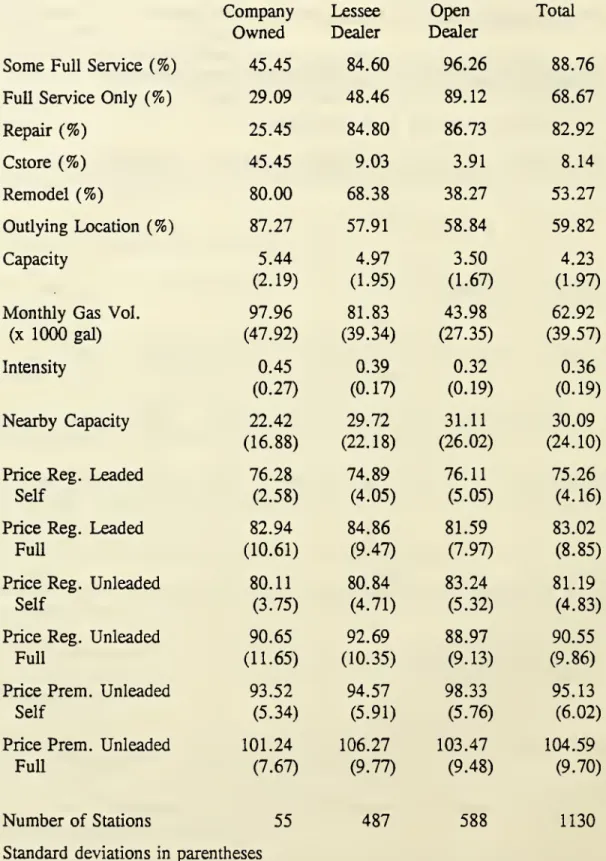

Oil Price Information Service.are reported in

Table

1.Approximately 43

percentofthebrandedstationsareoperatedas lessee-dealeroutletsand

about five percent areoperated as

company-owned

outlets. This area has alower

proportion ofcompany-owned

stations than thenationalaverage. Nationally,major

refinerswere

selling overfourteen percent oftheir product through

company-owned

outlets in 1987; in thesample

areacompany-owned

outletswere

selling less than eight percentof

thebranded

output(USDOE,

1987). This

sample

also contains a higher proportion offull-service only stationsand

alower

proportion

of

self-service only stations than the national average.By

the late 1980s, less thanone

fifth ofallbranded

U.S. stationswere

full-service only,down

from

more

thantwo

thirdsin thelate 1970s.

Yet

in 1987, two-thirds ofthe branded stations in theBoston

areawere

full-service only.

Over

forty percent ofU.S.

stationswere

self-service onlyby

the late 1980s,up

from

less than five percent in the early 1980s, while only about twelve percent ofthesampled

stations are self-service only (National

Petroleum

News,

various issues).17The

data are generally consistent with the predicted relationshipsbetween

stationcharacteristics

and

contractual form.A

much

higher proportionof

company-owned

stations areself-service only.

When

company-owned

stations provide non-gasoline services they are less likely to provide auto repair ("Repair")and

more

likely tohave

convenience stores ("Cstore")than other stations.

Company-owned

stations also tend tobe

located in outlying areasmore

often. Eighty-seven percent of the

company-owned

stations are locatedmore

than ten milesfrom

the center ofBoston

("Outlying Location").These

locationsmay

have lower

land costsand—since

theyhave been

developedmore

recently—probablyhave

anewer

station stock.Perhaps because they are

more

often located in geographically outlying areas, the averagecompany-owned

station faces less competitionfrom

nearby stations.The

"nearby capacity"variable

sums

thenumber

of cars that canbe

served simultaneously at other stations locatedwithin a

one

mile radius ofthe station.The

dataon

open-dealerstations are consistentwith theview

thatthey are small capacity,olderstations not intensivelyinvolvedin gasoline sales.

The

average open-dealer stationhas less17

A

few

of themany

towns

in thesample

areahave

ordinances restricting self-service gasoline. Ifthese ordinances aremore

common

in this area than they are nationwide, theymay

explain"some ofthe divergence

from

the national averages.gasoline sales capacity; it is large

enough

to serve only 3.5 cars at thesame

time ("Capacity"),compared

to five cars at the other stations. In fact, nearly three quarters of the open-dealer stationshave

onlyone

gasoline island whileno

more

than thirty percent oftheother stations aresingle island. In large part because of this capacity difference, open-dealer stations

have

asmallerproportion

of

their availablespace devoted to gasoline sales: the intensity variableis theratio

of

capacity to lot sizeand

is lowest at open-dealer stations.These

stations sellapproximately half the

volume

soldby

lessee-dealerand

company-owned

outlets.The

dataon

investment indicate little recent activity at open-dealer stations. Less than forty percent of the open-dealer stations

have been remodeled

within the three years preceding data collectioncompared

to overtwo

thirds of the other stations("Remodel")

18.

The

price datado

not reveal a clear relationshipbetween

price levelsand

contractualform. Prices are reported

by

gasoline grade (regular leaded, regular unleadedand

premium

unleaded) and service level (full-service

and

self-service).Some

stations offer cash discounts.The

prices used in the analysis are the lowest prices for the specified gradeand

service leveloffered

by

the station.Not

all stations carry all grades.4.2

Estimation

and

Results: PriceEquation

The

retail price equation defines the operator's choice of price given the contractualform, the asset characteristics

and

the relevantmarket

conditions.Because

all the variablesaffectingher choiceareexogenous, theequationcan

be

estimatedby

ordinaryleast squares.The

estimating equation for the price at thejth station is

Pj = 0o +

K%

+Wj

+W

v

+yftj

+i&j

+£

'A,- +v

(5)h=l

where

dx is a

dummy

variable for acompany-owned

station, 62 is adummy

variable for anopen-dealer station

and

D

h, h=

l,..,m, aredummy

variables for them

refiners supplying the18

The

data recordwhether

or not the stationwas

remodeled

within the specified timeperiod, not

what

was

done.Remodeling

can include anythingfrom

rebuilding the station toadding a

canopy

over thepumps.

stations in this sample.

The

6 variable in equation (2) includes both the contractualform

andthe contractual terms. Price will

be

affectedby

both, but onlyform

is observed19by

theeconometrician.

One

of themost

important terms affecting the choice of retail price is the wholesale price.However,

since the wholesale price cannot vary across stations of thesame

brand, unobserved variation in transferpricing will

be

capturedby

therefiner fixed effectsand

therefore willnot bias thecoefficientestimatesin equation (5).

The

Z, vector includesobservedmarket

conditions: nearby rival capacityand

outlying location.Unobserved market

conditions,Zj, are part ofthe error term,

and

may

bias the least square estimates of the contractualform

effects. This

problem

is addressed following the presentationof

the least squares results.Equation (5) is a reduced form,

and

the coefficients will reflect the total effect of theexogenous

variableson

price: the direct effectand

the indirect effect through changes in effort.By

construction, the coefficienton

0, (02) is an estimate ofthe increment to price observed atcompany-owned

(open-dealer) stationscompared

to the price at lessee-dealer stations. Iftherewere no

feedbackfrom

effort to price, the double marginalization effectwould

imply

thecompany-owned

coefficientwould be

negative (5j<

0)and

theopen-dealercoefficient will benon-negative (52

>

0). If there are significant indirect effects,however,

the signs of the coefficients cannotbe

predicted. In this case, the coefficient provides informationon

the totaleffect ofcontractual

form on

price, but it is incorrect to interpret it asan

estimate of only thedirect effect.

The

coefficientsof

interest are thoseon

the contractualform

variables, but thesame

argument

applies to the otherexogenous

variables: stationand market

characteristics willhave

a direct effecton

priceand

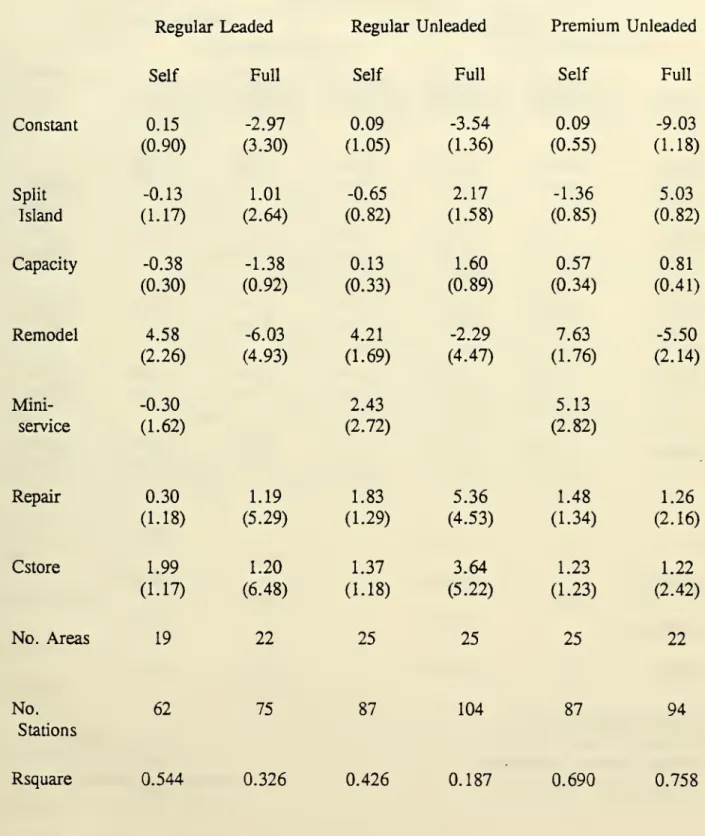

an indirect effect through changes in effort.The

ordinary least squares estimates reported in Table 2 display substantial variationacross gasoline grades

and

service types.For

leaded products, there areno

clear contractualform

effects.The

estimated coefficients are quite small (less than a cent), but impreciselymeasured.

For

unleaded products, the coefficients are consistently negative for thecompany-owned

variable, indicating that prices areone

to threeand

a half cents lower.The

coefficient19

"Observable" isa term reserved fordistinguishing those things that can

be

contracted on;"observed" is used to distinguish

what

the econometrician canmeasure

given the data.estimates,

however,

canbe

statistically distinguishedfrom

zero20 only forpremium

unleaded,full-service gasoline.

The

pattern for open-dealer stations is less clear.The

magnitude

of theeffect for full-service gasolineis small

and

cannotbe bounded from

zero.The

only large effectis for

premium,

unleaded self-servicewhere

the coefficient implies that open-dealer stations charge over acentmore

than lessee dealers, butallopen-dealercoefficientshave

relatively largestandard errors.

The

estimates in Table2

may

be

affectedby

themix

ofsupplier types in the sample.The

discussion has treated all suppliers as refiners, but nearly twenty percent ofthe stations aresupplied

by

local wholesalers.The

datado

notidentify individual local suppliers, but industrysources report that wholesalers in

New

England

may

supplyfrom

less than ten tomore

thanone

hundred

stations.These

wholesalers use thesame

contractualforms

as refinersand

the largerones

may

behave

verymuch

like refiners.There

may

be

variation in contracts acrosswholesalers,

however,

that cannotbe

removed

with refiner fixed effects. In addition,wholesalers

may

supply stations carrying different brands.Table

3reports the resultsfrom

restrictingthesample

to stations thataresupplieddirectlyby

refiners.The

contractualform

resultsof

Table 2 are reinforced.The

estimates of thecompany-owned

coefficients for unleaded productsremain

negativeand

are larger in absolutevalue.

The

averagecompany-owned

effect is -2.75 here,compared

to -1.72when

all suppliersare included. In addition, the coefficient

on

regular unleaded self-service cannow

alsobe

statistically

bounded

away

from

zero. Nonetheless, theestimates are stillimpreciseon

average:the standard error

of

theaveragecompany-owned

effectis 1.42.The

absolutemagnitude

ofthecoefficients for open-dealer stations tend to

be

smaller hereand no

coefficient canbe

bounded

from

zero.Among

the other coefficients, themost

interesting is the estimated effect of rival capacity. Increasing nearby capacity to serve an additional car reduces priceby

less thanone

tenth of a cent, but the effect is persistent

and

precisely estimated. If thenumber

of

nearby stations is substituted for the nearby capacity variable, the (unreported) estimates suggest thatprice also decreases in the

number

ofnearby rivals.These

results are consistentwith the pricingprediction of simple spatial competition models: as the

number

of firms in a givenmarket

20

All references to statistical significance are assessed at the .05 level or better.

increase, the average price will decline.

The

coefficientson

the remaining variableschange

across gradesand

service levels. Ingeneral, station characteristics appear to affect full-service prices

more

than self-service prices.This

may

be

because the quality offull-service hasmore

unobserved variation than the quality of self-service. Full-service prices increasewhen

the station offers both fulland

self-servicegasoline ("Split Island")21.

Recent

remodelingand

offering automotive repair tend to decreasefull-service prices.

At

some

"self-service"pumps,

a stationworker

pumps

the gas but will notprovide

any

other service usually associated with full-service.These

"Mini- service" sales arepriced higher than real self-service.

The

estimates inTables 2and

3 are unbiasediftheunobservedmarket

characteristics (Z2)in the error term are uncorrected with the observed station characteristics. This assumption is

ratherstrong,

however.

Consider, forexample, variations inconsumer

income

thatlead to highdemand

for serviceand

unwillingness to search forlow

prices.The

servicedemand

will leadrefiners to

choose

full-service through equation (4).Income

will alsohave

a direct effecton

prices through the search

component:

holding service constant, higherincome

implies higherprices.

Income,

then, willbe

in the vector2^.Because

it is correlated with full-service, the coefficient estimates willbe

biased.While

the market characteristic data necessary to avoid bias in the estimates isunavailable, anotherapproach to controlling for

market

characteristics is possible.Any

group

ofstations within a small geographic area should face similar

market

characteristics.Because

station locations are

known,

it is possible to use this information to estimate contractualform

effects within small areas.

To

implement

this approach, station addresses are converted to cartesian coordinates.Each

company-owned

stationbecomes

the center for a geographic area,and

each station withinone

cartesian mile of that station is identified.For

the kthgroup

ofstations, there are

two

priceequations (for each gradeand

service level):one

for the station thatis

company-owned

and

one

for the nearby stations that are not.A

within area average isconstructed for the

non-company-owned

stationsand

subtractedfrom

thecompany-owned

equation.

The

result arek=

1,. .,r equations21

The

effect of offering both fulland

self service gasolineon

full service prices isinvestigated in

Shepard

(1990)where

it is attributed to second degree price discrimination.where

r is thenumber

ofcompany-owned

stations,p

u

is the price at the kthcompany-owned

station

and

p^

(X

u

) is the average price (station characteristic) for thenon-company-owned

stations.The

common

market characteristics (Z) areremoved

by

differencing.Then

ifcompany-owned

stations charge different prices, the constant term will reflect that difference.Notice that refiner fixedeffects arenot well-defined in this context

and

are not in theestimatingequation.

Unreported

resultsshow

that thisomission does not substantivelychange

thereportedcoefficient estimates in Tables

2

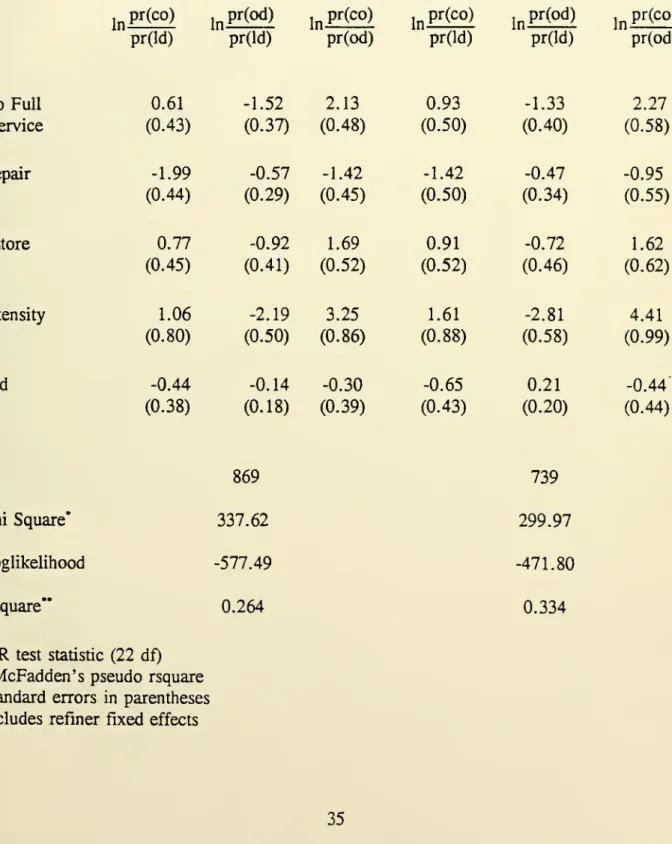

and 3.These

within area estimates are presented in Table4

for all branded stationsand

lendsome

support to the impressionfrom

the earlier estimation thatcompany-owned

stores chargesomewhat

lower

prices for unleaded products22.While

these estimates areno

longerconsistently negative, the only large effects-those for full-service-are negative.

The

onlycoefficientlarge

enough

to be statistically distinguishedfrom

zero is, again, theeffecton

prices forpremium

unleaded gas sold full-service.For

this product, prices atcompany-owned

storesare atleast eight cents per gallon lower.

The

magnitude

of the contractualform

results appear tobe

sensitive toexcluding other explanatory variables. In particular, if"Repair"and

"Cstore"are omitted, the magnitudes of the coefficient estimates

and

standard errors are smaller for thefull-serviceprices.

The

basic pattern,however,

ispreserved: thelarger effectsare negativeand

the implied reduction in price for full-service

premium

is at least six cents.Notice that the test here is particularly stringent.

Suppose

company-owned

outletsdo

choose

lower

prices in response toany

givenmarket

situation.These lower

prices will inducelowerprices atnearby stations. Thus, the

measured

effectisnot theamount

by which

company-owned

stationsreduce theirpricesfrom

theequilibriumprice thatwould

prevailin theirabsence,but the difference in price that survives the competitive response

by

rivals.The row

of Table

22

The

estimation is weighted least squareswhere

the weights reflect thenumber

ofobservations underlying the averages.

The

resulting covariance matrix is homoskedastic.Because

any

given station can appear inmore

thanone

area, the errors also canbe

correlatedacross markets. Fortunately, duplicate observations can

be

identifiedand

used to constructappropriate weights to generate correct standard errors. Itis the corrected standard errors that

appear in

Table

4.4 labeled

"No.

Areas" reports thenumber

ofcompany-owned

stationson

which

the estimatesare based

and

therow

labeled "No. Stations" reports the totalnumber

of stationson which

theestimates are based.

For

example, of the38

company-owned

stations selling regular unleadedgas self-service,

25 have

at leastone

non-company owned

station withinone

mile also sellingregular unleaded gas self-service. Across all twenty-five areas, there are

87

stations sellingunleaded gas self-service.

But

thismeans

thatmost

ofthe314

stations selling this gradeself-service

do

nothave

acompany-owned

store nearby.The

averagedifferences reported in Tables2

and

3, therefore, are based primarilyon

acomparison

ofcompany-owned

stations with otherstations that

do

notcompete

with these hypothetically low-priced stations.One

might

expect,then, to find the estimated effects

more

pronounced

inTable

2.The

fact that the within areaeffects are not smaller suggests thatcontrolling for local effectseliminates important sources of

variation in retail pricing.

4.3

Estimation

and

Results:The

Contract

Equation

In equation (3) the contract is treated as a continuous variable representing both the

contractual

form

and

thecontractual terms.But

onlycontractualform

isobserved,and

observedform

choices are discrete.A

standard approach to estimation basedon

observed, discretechoices is to

model

a latent variable, TI(6(X,Z).) in this case: the profit earnedby

the refinerat a station with characteristics

X

and market

conditionsZ

when

the ith contractualform

ischosen,

i=

1,2,3,and

terms are set optimally.Then

the observed variables 6i can