Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 111 New Approaches to Chicana/o Art: The Visual and the Political as Cognitive Process Guisela Latorre

Abstract (E): Scholarly work on Chicana/o art for the past thirty years has privileged the political and social underpinnings that informed much of its production since the late 1960s. While this trend within the scholarship has been quite pertinent to the ideals of the Chicana/o arts movement, this intellectual approach has dominated the field at the expense of visual analyses. As an alternative to the often Eurocentric formal and iconographic analyses common in art history, this paper proposes turning to the cognitive and neural sciences to understand how Chicana artists use the visual emotively to incite a political consciousness in their viewers.

Abstract (F): Les recherches académiques sur l’art des chicanos/as des trente dernières années ont toujours privilégié les bases politiques et sociales qui en sous-tendent la production depuis les années 60. Cette tendance de la recherche a toujours été fort pertinente eu égard des idéaux des mouvements artistiques chicanos/as, mais dans la mesure où elle a favorisé une lecture intellectuelle, elle a aussi provoqué une certaine désaffection pour l’analyse visuelle. Le présent article veut proposer une alternative aux analyses souvent eurocentriques et iconographiques qui dominent toujours l’histoire de l’art pour se tourner en revanche vers les sciences cognitives et neurologiques. Cette nouvelle orientation permet de comprendre comment les artistes chicanas se servent de l’image d’une manière plus émotionnelle dans l’espoir de produire une prise de conscience politique dans l’esprit des spectateurs.

keywords: Chicana/o art, Ester Hernández, Alma López, Cognition, Art and Politics

Article

Scholarly work on Chicana/o art for the past thirty years has privileged the political and social underpinnings that informed much of its production since the late 1960s. I myself have repeatedly argued for the symbiotic relationship that exists between art and activism in the work of Chicana/o artists.i While this trend within the scholarship has been exceedingly fruitful and in many ways quite pertinent to the ideals of the Chicana/o arts movement, this intellectual approach has dominated the field at the expense of visual analyses. Should we thus value Chicana/o art solely for its commentaries on socio-political content, for its insights on issues of race, class, gender, sexuality, etc.? Are Chicana/o artists simply not interested in making aesthetic and formal contributions to the history of modern and contemporary art? Of course not, yet the methodologies that would have enabled us to value the formal, aesthetic and visual qualities of Chicana/o art have been monopolized and colonized by an art establishment that systematically privileged European and Euro-American art production and that often trivialized or ignored the work by artists of color.

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 112 The question then remains, can we still turn to formal or iconographic analyses, methodologies often tainted by their Eurocentric and colonizing gaze, to engage the aesthetics of Chicana/o art? The assumption within the art history establishment has been that a socio political impetus behind the creation of an artwork necessarily negates the possibility of aesthetic value. In other words, artists seeking to use art as a tool to promote social change or enact political activism will seriously compromise the visual quality of their work. Within this framework, art and politics always negate or work against one another. Traditional art historical methodology is so deeply invested in this dichotomy that it has nearly rendered itself useless to assess the value of the Chicana/o arts movement.

I thus propose turning to the cognitive and neural sciences as an alternative to formal and iconographic analyses. The recent wealth of scholarly work on the cognitive nature of creativity and on the neural effects of visual stimuli on the brain has revealed to me new avenues of exploration in Chicana/o art. While most of the current scholarship that engages cognitive theory in the study of the arts focuses on European and Euro-American modes of production, it does not claim that art and politics function in opposition to one another. Rather than make claims about “great” art and artists, these scholars often argue that art is only effective if it’s able to stimulate a response, be it emotional or political. Unlike the discourses of Western art history, the cognitive sciences are not necessarily invested in hierarchies of artistic production nor in legitimizing the inherent “superiority” of the Western male artistic sensibility. This relative impartiality of the field may thus allow us to look at the visual strategies and devices that Chicana/o artists employ without being concerned with a method that ultimately seeks to distinguish between “good” and “bad” art.

Art and Cognitive Theory

This preliminary study then turns to the possibilities that cognitive and neural science might offer to the analysis and understanding of Chicana/o art. Various scholars in the humanities such as Irving Massey and Patrick Hogan have turned to this field in order to understand the ways in which the elements and forms in arts such as music, art, literature, etc., affect and stimulate the inner workings of the brain. The art journal Leonardo (MIT Press) has also been at the forefront of the intellectual intersection of art and neuroscience. Most recently, Frederick Aldama—perhaps the only scholar in the ethnic studies thus far who has utilized cognitive science—has turned to the field in order to understand how Latina/o comic book artists and writers guide “cognitive processes and emotions”ii

through various text and image-based devices.

The cognitive process then for me does not become the end to my intellectual inquiries but rather the means by which I can ultimately understand how Chicana/o artists not only stimulate the senses with their work but also how they can illicit a political awareness through visual devices. After all, the emergence and development of a social consciousness is also a cognitive process as much as it is a process of socialization and politicization. By the same token, cognitive science as applied to the humanities does not ignore the social contexts that also bring art and creativity into being, but rather promotes an understanding of what Massey calls “a complex negotiation among the subject, the social conditions, and a neurology that is itself an active player in the historical and affective circumstances it seeks to describe.”iii

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 113 between cognitive and neural scientists who, on the one hand, hold that there is a fairly systematic and organized way the brain reacts to visual stimuli, and gender and ethnic studies scholars who, on the other, would contend that this reaction is always mediated by the subject’s social position regards to her/his gender, race, class, sexuality, etc.

As I have argued in the past, the visual becomes a particularly powerful tool for politicization in the hands of Chicana/o artists for, as C.U.M Smith and other neuroscientists would contend, the human brain is particularly sensitive to visual input: “Humans are highly visual creatures. Neurophysiologists tell us that the human cerebral cortex contains more than two dozen visual areas.”iv

Lalita Pandit and Patrick Hogan further contend that the human mind is inherently creative often functioning in a poetic fashion “drawing on images and metaphors.”v

Artists, for their part, have also developed a heightened intuition about how the brain processes and interprets this input.vi Because the brain reacts with such immediacy to this type of stimuli, the visual can also have a volatile effect on brain activity at times fueling the desire for iconoclasm. Drawing from Alain Badiou’s work on iconoclasm, Massey argues that the hostility that images can generate among individuals has as much to do with historical phenomena as it does with “the rage for the absolute: a pervasive finalism that regards representation as merely a step toward its own eradication.”vii

The immediacy and centrality of the visual in perception can trigger emotional extremes in the brain’s chemistry. Chicana/o artists who seek to provoke a social consciousness through emotional response utilize the visual’s power over neural processes to inspire, unsettle or even anger their viewers.

One recurring strategy that many Chicana/o artists have deployed to illicit or promote political awareness is the use of familiar imagery to the assumed audience of their work, imagery which they in turn reformulate with new meaning. Many of these images had previously circulated via the mass media or community settings and were thus collectively recognizable. These symbols or icons thus function as what Patrick Colm Hogan calls “lexical entries” within the brain’s “mental lexicon.” These entries posses both internal structures and external relations that help us understand their inherent qualities and their relationship or connections to other entries.viii As such, a basic and highly simplified definition of creativity is the capability of producing work that is both innovative/new and apt. Hogan argues that artists use images, symbols, and signs that represent both a “break with the past in certain respects and continuity with the past in other respects.” Building up on Hogan’s work, Aldama reached similar conclusions when he explored the presence of innovation in Latina/o comics arguing comic book authors “often reach beyond a specific domain…to innovate their comic book forms,”ix

but that that “[they] can’t reach too far from a given prototype or schema set in their innovation, or they risk losing their audience.”x

Truly exceptional creative artists, Hogan contends, are able to produce “unusual images and metaphorical sources that are above the threshold of activation.” In other words, artists who are particularly gifted can activate new nodes in the brain’s neural pathways thus intensifying the pleasure, elation or exhilaration that one experiences when viewing a powerful work of art. I would intervene here to argue, perhaps somewhat boldly, that activating a political consciousness is not unlike the cognitive process that is activated by a great work of art, and that Chicana/o artists have understood this at a conscious or subconscious level for many decades. Moreover, numerous Chicana/o artists do not

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 114 recognize a clear distinction between the creative and the political process thus using visual imagery’s powerful effect on cognitive psychology to elevate both.

Cognitive science also tells us that exposure to repeated images or exempla can leave certain impressions on the brain that either produce feelings of security through familiarity or boredom, depending on the circumstances. When a work of art recalls those existing patterns imprinted upon a person’s mind, it will automatically trigger those feelings, but if the image is altered somehow or presented within an unexpected context, it can disrupt the cognitive lull often associated with repeated imagery and stimulate brain activity by causing feelings of surprise, outrage, pleasure, etc. “Perhaps the most cognitively interesting way of using exempla creatively,” Hogan explains, “is by taking an exemplum and shifting it to a new domain.”xi Aldama, for his part, explains that “innovation also entails a sense of how reader-viewer carries certain domain-specific baggage that will need to be reshaped.”xii

It is this heightened state of stimulation that Chicana/o artists capitalize on when seeking to provoke a political response to their work. “Artists,” Chai-Youn Kim and Randolph Blake maintain, “have discovered some of the principles of visual perception and have learned how to exploit them to produce stimulus conditions (and, hence, brain states) that portray compelling visual qualities such as depth and transparency.”xiii

While most contemporary Chicana/o artists are not necessarily interested in creating illusions of depth and transparency, many indeed are compelled by the idea that visual stimuli can create certain “brain states” that promote specific emotions and even ways of thinking. “Art is a means of perception and cognition,” Baingio Pinna argues, “and the basic role of perception is to make it possible to structure reality and thus to attain knowledge.”xiv

Ester Hernández and Alma López: Doing Cultural and Cognitive Work

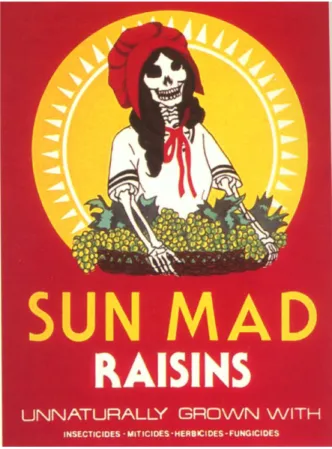

In what follows I would like to turn to specific works of art that I think will allow us to further mine the potential of cognitive theory for the analysis of Chicana/o art. The qualities and visual vocabulary of these works are particularly fitting for these kinds of analyses given the way that these artists heavily rely on striking and bold forms to convey very specific socio-historical issues. Ester Hernández’s silkscreen Sun Mad (1982) [figure 1], and Alma López’s digital print Ixta (1999) [figure 2] both use formal and thematic elements to cognitively stimulate a type of pleasure that stems from the aesthetic but also political experience of the work of art. While pleasure is often regarded as a highly individualized and at times even self-centered emotion or cognitive response, Chicana/o artists like Hernández, and López utilize the pleasure from the aesthetic experience as a catapult for the consciousness-raising process. In other words, works such as these promote the idea that pleasure is an important component of politicization. By analyzing these two works of art I hope to initiate an intellectual dialogue about the new opportunities that cognitive theories and methodologies offer to future studies of Chicana/o art.

Since the 1970s the work of Bay Area Chicana artist Ester Hernández has functioned for many scholars and Chicana/o art enthusiasts as a lens through which gendered, racialized, and colonized histories are made visible and palpable. Images of a Chicanas re-sculpting the Statue of Liberty into a Mesoamerican goddess or breaking out of the Virgin of Guadalupe’s body halo with a karate kick characterized her work from the

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 115 1970s while iconic portraits of Chicana musicians and performers like Lydia Mendoza and Astrid Hadad have pervaded her more recent production from the 1990s and 2000s. But the one image that has made Hernández most visible as a politically engaged artist was her silkscreen Sun Mad which came to embody the cause of the United Farm Workers (UFW). The image denounced the harmful effects of pesticides and chemicals on those who harvest and consume grapes grown in California. As the daughter of a farm working family, her commitment to the UFW cause was both political and personal. This image resonated with a whole generation of politicized Chicanas/os who came of age in the 1970s and 80s proclaiming their support for the UFW.

Sun Mad has emerged as one of the most visually effective images to tout the UFW message in the past forty years because of its simultaneous simplicity and complexity. Through the use of an economy of formal means and simplicity in design, Hernández created an image that became an emblem of the struggles in the fields. But what exactly made such an image so successful in terms of its visual impact and effectiveness? Certainly, Hernández’s personal connection to the farm working experience afforded her a certain legitimacy and sensitivity to the issues, but it was also her profound understanding of the effects of the visual on the brain that contributed to the “aesthetic” success of Sun Mad. As an artist, she knew how to use images to provoke and/or stimulate viewers.

With this particular piece, Hernández drew from a large repertoire of pre-existing popular imagery at her disposal. Sun Mad recalls simultaneously histories of fine art, popular culture, and advertising. The artist utilized these familiar stimuli to lure the spectator into the world she created with this image. She assumed multiple and overlapping audience populations with Sun Mad, some of which are clearly recognizable through the silkscreen’s iconography. For instance, Chicana/o or Mexican audiences were likely to be familiar with the meaning of the calavera motif in the central figure, for these figures are common during celebrations of El Día de los Muertos on both sides of the U.S./Mexico border. They might also recognize Hernández’s homage to turn-of-the century Mexican printmaker José Guadalupe Posada who used calaveras in his broadsides to critique Mexico’s social hierarchy. Viewers with some knowledge of European and Euro-American contemporary art will probably recognize the artist’s nod to Pop Art and the likes of Andy Warhol who, like Hernández, also used advertising imagery in his silkscreens. Finally, more general and popular U.S. audiences will undoubtedly identify a widely disseminated consumer culture icon, namely the Sun Maid figure from the ads and product packaging of the Sun-Maid Growers of California whose farms operated in the Great Central Valley of the state, halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco. While these audiences can be very distinct, they may also overlap and recognize these visual traditions simultaneously. By alluding to these traditions in one image, Hernández references what Aldama calls “universal prototype narratives [which are combined] in ways that are innovative cognitively and emotively.”xv

The innovation here is dependent on the images’ familiarity, i.e. their category as universal prototypes, and on the radical ways in which the artist transforms them. I further argue that the use of universal prototypes and the subsequent subversion of the same creates a disruption in the habitual brain functions that operate when visual information is processed. This disruption can cause strong emotions, either negative or positive. Aldama calls these reactions subcortical emotional responses, which artists or writers stimulate by defying “certain formal conventions” thus disrupting “our social memory of [these].”xvi

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 116 be surprised, annoyed, delighted or emboldened, depending on their ideological and social position, but, regardless, they will not likely to remain complacent or indifferent. This disruption will then encourage the viewer to engage the image deeper, including its social message. The emotive intensity of this disruption may also contribute to a process of politicization whereby the viewer is compelled to become emotionally involved in the message behind Sun Mad.

With the possible exception of Posada’s calavera, none of the references in Sun Mad are necessarily politically radical or subversive, but they become so when Hernández compels her audience to read them against one another. For instance, the image of the Sun Maid on its own is meant to recall an idyllic (though utterly fictional) past, as described in the company’s website: “Life was much simpler, more rural, a lot less hectic and sunbonnets were still part of women’s fashion in California.”xvii Hernández’s replacement of the Sun Maid’s body with a calavera is coupled with strategic changes in the text that normally accompanies this image: “Sun Maid” becomes “Sun Mad,” and “Natural California Raisins” becomes “Unnaturally grown with insecticides, miticides, herbicides, fungicides.” Images that circulate widely and massively like the Sun Maid motif are meant to provide feelings of comfort and safety for those who consume them; in other words, “they establish constancy and stability among continual differences and perceptual change.”xviii

Hernández purposely disrupts the constancy and stability associated the Sun Maid brand to expose the labor abuses that this seemingly benign image conceals. The cognitive crisis that the artist provokes here is the basis for the aesthetic and political success of her image. For those of us who have been teaching Sun Mad in our classes for a number of years, it is difficult to walk along supermarket isles and not become agitated when we see those insidious boxes of raisins!

Similar types of cognitive disruptions also pervade the work of Los Angeles-based Chicana artist Alma López. Drawing from the fiercely feminist iconographic tradition established by the likes of Hernández, López is also known for her use of digital montages to document oppositional and marginalized histories. Moreover, as a queer woman of color López challenges the assumed heteronormativity of the nationalist and cultural paradigms often associated with Chicana/o culture. The artist capitalizes on the flexibility afforded to her by digital media to create photographic collages and iconographic layerings to craft her visions of decolonization. In addition, she engages the digital domain in politically subversive ways, as I have argued elsewhere:

López […] belongs to a generation of Chicana artists who have begun using computer technology as a viable and potentially empowering medium for creative expression. By using this medium, they are infringing on a territory that bas traditionally excluded their presence as women of color, namely the realm of science and technology. Lopez's use of digital imagery also counters the paradigm of the digital divide, which maintains that ethnic minorities have limited access to digital technologies, an idea that many media and race scholars have denounced as a self-fulfilling prophecy.xix

Utilizing digital media to queer traditional Mexican or Chicana/o iconography has been at the core of López’s artistic and political project and nowhere in her oevre is this more evident than in her digital print entitled Ixta. As Chicana feminist scholar Sarah Ramírez has revealed, Ixta directly references two important sources of Mexican nationalist

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 117 discourse, namely the popular “Legend of the Volcanoes” and the work of Mexican illustrator Jesús Helguera who popularized this very legend through his highly romanticized paintings of the Aztec warrior Popocatepetl and his love interest princess Ixtacihuatl. Ramírez recounts the legend of these doomed lovers as follows:

Having heard erroneous rumors of the warrior Popocatepetl’s death, his betrothed Ixtacihuatl kills herself. The former is grief-stricken upon finding Ixtacihuatl dead. He carries her up to the highest mountain in the Valley of Mexico and guards her body; they become transformed into the twin volcanoes that to this day bear their names… [The story] ideologically codes Ixtacihuatl as a disempowered woman with her identity and apparent survival both dependent of male identification.xx Helguera’s images have circulated widely among Mexican and Chicana/o populations via calendars and posters. Ramírez further argues that López’s rendition of this story “signifies a revision that challenges male Chicano nationalist memory and constructions of Chicano his-story.” She further contends that the artist with Ixta “locates a female body over the U.S.-Mexico border, rescuing any woman’s death from the male confined nationalist imagination and an idealized romantic past.” xxi

While I concur with Ramírez’s interpretation of López’s image, the question remains, how does the artist visually enact these tactics of revision and rescue that Ramírez accurately observes? It is here where we can again turn to cognitive theory and neural science in an attempt to unpack the visual strategies deployed by López to dislodge the masculinist tropes associated with Chicano and Mexican culture.

As an artist, López is an image-producing agent who can broadly anticipate a viewer response to her work. Aldama in his work on filmic aesthetics and narratives argues that movie directors are deeply aware of how imagery stimulates cognitive function. Though he addresses the specificity of the filmic aesthetic, his analyses are also relevant when considering the visual art work by the likes of López: “[…] it is the director’s sense of the other and of herself (thus also of herself as spectator) that will orient her work both intellectually and technically, and that will project on the spectator’s mind […] a distinctive mood concerning the film as a whole.”xxii Like that of a film director, López’s role as a visual artist also requires her to imagine or anticipate her audience’s reception in order to create an emotive response.

Like Hernández before her, with Ixta López juxtaposes opposing universal prototype narratives to trigger subcortical emotional responses and cognitive crises. In this image, the roles of Popocatepetl and Ixtacihuatl have been appropriated by the figures of two young Chicanas, Cristina Serna and Myrna Tapia, two personal friends of the artist. This appropriation causes perhaps the most immediate cognitive disruption in the image. For many Mexican or Chicana/o audiences, the assumed heterosexuality of the “Legend of the Volcanoes” is probably deeply naturalized and ingrained in their collective psyche. Thus López’s intentionally and tactically queers the legend by placing Serna and Tapia in the foreground while pushing Helguera’s rendering of Popocatepetl and Ixtacihuatl to the background as if to suggest that this young same-sex couple is displacing the older heterosexual pairing as allegories of Mexican/Chicana/o cultural identity. López’s sense of other and of herself as spectator, to borrow Aldama’s language once again, allows her to provoke an emotive response by cognitively disrupting the assumed heterosexuality of the “Legend of the Volcanoes.” It is through her use of this legend as a universal prototype

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 118 narrative that López is able to successfully revise what Sarah Ramírez called “male Chicano nationalist memory.”xxiii

But López in her work is not only interested in disrupting patriarchal and heterosexist assumptions of Mexican and Chicano culture; she is also committed to challenging the various layers of exclusion in Eurocentric art historical discourse. Like Hernández with Sun Mad, in Ixta López assumes multiple and overlapping audiences. While Mexican and Chicana/o viewers are likely to be culturally predisposed to respond to Helguera’s romanticizing imagery, spectators who are well versed in the history of Western art are likely to respond to different stimuli in the image. The artist purposely arranges Ixta’s composition symmetrically while Serna and Tapia’s bodies form a triangular shape. For Renaissance artists in Italy and Northern Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries, symmetrical and triangular compositions evoked the Classical ideals of balance, order and stability, in other words, the rational superiority of the western world. Moreover, López’s figural group composed of Serna and Tapia also recalls yet another Renaissance ideal, namely the preponderance of Christian iconography. Serna’s mourning stance over Tapia’s body is reminiscent of various Pietà or Lamentation scenes where the Virgin Mary mourns over the dead body Christ after being lowered from the cross.xxiv Thus if we think of Ixta as a revision or redefinition of the Christian Pietà, it is a necessarily subversive and critical one. Audiences who are familiar with the universal prototype narratives of Renaissance aesthetics and traditional Christian iconography will likely be bewildered or even shocked not only by López’s queering of these but also with her use of brown desiring Chicana bodies to stand for the figures of Mary and Christ. Whiteness, masculinity and heterosexuality have been intimately inscribed within Judeo Christian and Western aesthetics like necessary properties in art history’s mental lexicon. López’s disruption of this mental lexicon can cause a cognitive crisis leading either to utter disavowal or rejection of Ixta’s subversive message or possibly to the emergence of a political consciousness brought about by the unsettling of habitual mental pathways that do not question the naturalization of social hierarchies.

Conclusion

Cognitive science as a theoretical tool in humanities research can offer new and exciting avenues of inquiry and exploration for those of us interested in both the political and aesthetic impact of Chicana/o art. The cognitive approach can deepen our understanding of the tools that artists have at their disposal to affect the emotive response to visual stimuli. Poststructuralist scholars have challenged the excessive importance that traditional art history has placed on the intentions of the artist arguing that an image’s meaning and impact is necessarily fluid and dynamic, always conditioned by social practices and power relations thus making the artist’s intentions largely inconsequential or irrelevant. While I recognize the importance of addressing the social reception of images and often reject modern and contemporary art history’s tendency to idolize individual artists, we also need to consider some of the individualized ways in which we produce and consume visual culture. Artists have unique abilities to use the visual in highly effective and emotive ways thus we should not ignore their creative agency. Cognitive theories then allow us to explore the inner workings of creativity and the mental structures of visual reception while not overlooking how those processes are simultaneously mediated by social relations.

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 119 With this cursory exploration I have demonstrated the potential of cognitive science to unpack the complex ways in which Chicana/o artists use the visual to move viewers emotively and politically. It is thus my hope that this essay will foster new intellectual dialogue and research on Chicana/o art and culture that takes into account cognitive dimension of creative expression. The scholarship on cognition and the arts, however, has largely ignored the work by artists of color while also leaving unanswered many questions about how social, gender, racial, and sexual identities function cognitively. The ethnic and gender studies, for their part, are still hesitant to explore methodologies outside of the humanities and social sciences in spite of their commitment to interdisciplinarity. Until we recognize the limitations of our methodologies and agree to step beyond of disciplinary comfort zones, a legitimate and fruitful dialogue between ethnic/gender studies and cognitive science will not be possible.

Acknowledgment

I am grateful to Frederick Aldama, professor of English and U.S. Latina/o studies at The Ohio State University, for introducing me to the field of cognitive and neural science. This article would not have been possible without his thoughtful guidance and mentorship.

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 120 Figure 1. Ester Hernández, Sun Mad (1982), silkscreen

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 121

i

For more on the relationship between Chicana/o art and political activism, see Guisela Latorre, Walls of Empowerment: Chicana/o Indigenist Murals of California (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008): 6-9.

ii

Frederick Luis Aldama, Your Brain on Latino Comics (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009), 84.

iii

Irving Massey, The Neural Imagination: Aesthetic and Neuroscientific Approaches to the Arts (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009), 26.

iv

C.U.M. Smith, “Visual Thinking and Neuroscience,” The Journal of the History of Neural Science 17:3 (2008), 260.

v

Lalita Pandit and Patrick Colm Hogan, “Morsels and Modules: On Embodying Cognition in Shakespeare’s Plays” College Literature 33:1 (Winter 2006), 2.

vi

Massey argued that contemporary sculptor Alexander Calder possessed an intuitive understanding of hoe color affected a viewer’s perception of motion and weight. Massey 6.

vii

Massey 57.

viii

Patrick Colm Hogan, Cognitive Science, Literature, and the Arts (Routledge: New York and London, 2003), 43. ix Aldama 85. x Ibid. 86. xi Ibid. 75. xii Aldama 85. xiii

Chai-Youn Kim and Randolph Blake, “Brain activity accompanying perception of implied motion in abstract painting,” Spatial Vision 20:6 (2007), 546.

xiv

Baingio Pinna, “Art as a scientific object: toward a visual science of art,” Spatial Vision 20:6 (2007), 494. xv Aldama 87. xvi Ibid. 92. xvii http://www.sunmaid.com/en/about/sunmaid_girl.html xviii

Margot D. Lasher, John M. Carroll, and Thomas G. Bever, “The Cognitive Basis of Aesthetic Experience,” Leonardo 16:3, Special Issue: Psychology and the Arts (Summer, 1983), 196.

xix

Guisela Latorre, “Icons of Love and Devotion: Alma López’s Art,” Feminist Studies 34:1/2 (Spring/Summer 2008), 132.

xx

Sarah Ramírez, “Borders, Feminism, and Spirituality: Movements in Chicana Aesthetic Revisioning,” in Decolonial Voices: Chicana and Chicano Cultural Studies in the 21st

Century, eds. Arturo J. Aldama and Naomi H. Quiñones (Bloomington: Indian University Press, 2002), 228.

xxi

Ibid. 229.

xxii

Frederick Aldama, “Race, Cognition, and Emotion: Shakespeare on Film,” College Literature Vol. 33, No. 1 (Winter 2006), 200.

xxiii

Ramírez 229.

xxivxxiv

It was Chicano sculptor Luis Jiménez who first established a connection between the Mexican “Legend of the Volcanoes” and the Christian lamentation story. In 1987 the artist created a fiberglass sculpture that monumentalized the tragic story of Popocatepetl and Ixtacihuatl, but called it Southwest Pietà. The rationale behind the title was that for Mexicans and Chicanas/os of the Southwest, the “Legend of the Volcanoes” was a source of devotion not unlike the tragic martyrdom of Christ himself.

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 122 Guisela Latorre is Associate Professor in the Department of Women’s Studies at The Ohio State University. She specializes in Chicana/o and Latina/o art and is the author of Walls of Empowerment: Chicana/o Indigenist Murals of California published by the University of Texas Press in 2008.