HAL Id: hal-02633155

https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02633155

Submitted on 27 May 2020

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of

sci-entific research documents, whether they are

pub-lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents

scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

anaerobic digestor

Linda Jabari, Hana Gannoun, Eltaief Khelifi, Jean-Luc Cayol, Jean-Jacques

Godon, Moktar Hamdi, Marie-Laure Fardeau

To cite this version:

Linda Jabari, Hana Gannoun, Eltaief Khelifi, Jean-Luc Cayol, Jean-Jacques Godon, et al.. Bacterial

ecology of abattoir wastewater treated by an anaerobic digestor. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology,

Sociedade Brasileira de Microbiologia, 2016, 47 (1), pp.73-84. �10.1016/j.bjm.2015.11.029�.

�hal-02633155�

ht t p : / / w w w . b j m i c r o b i o l . c o m . b r /

Environmental

Microbiology

Bacterial

ecology

of

abattoir

wastewater

treated

by

an

anaerobic

digestor

Linda

Jabari

a,b,

Hana

Gannoun

a,c,

Eltaief

Khelifi

a,

Jean-Luc

Cayol

b,

Jean-Jacques

Godon

d,

Moktar

Hamdi

a,

Marie-Laure

Fardeau

b,∗aUniversitédeCarthage,Laboratoired’EcologieetdeTechnologieMicrobienne,InstitutNationaldesSciencesAppliquéesetde Technologie(INSAT),2Boulevarddelaterre,B.P.676,1080Tunis,Tunisia

bAix-MarseilleUniversité,UniversitéduSudToulon-Var,CNRS/INSU,IRD,MOI,UM110,13288Marseillecedex9,France cUniversitéTunisElManar,InstitutSupérieurdesSciencesBiologiquesAppliquéesdeTunis(ISSBAT)9,avenueZouhaïerEssafi, 1006Tunis,Tunisia

dINRAU050,LaboratoiredeBiotechnologiedel’Environnement,AvenuedesÉtangs,F-11100Narbonne,France

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received19September2014 Accepted6July2015

AssociateEditor:WelingtonLuizde Araújo Keywords: Bacterialecology Biodiversity Bacterialculture SSCP PCR

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Wastewaterfromananaerobictreatmentplantataslaughterhousewasanalysedto deter-minethebacterialbiodiversitypresent.Molecularanalysisoftheanaerobicsludgeobtained fromthetreatmentplantshowedsignificantdiversity,as27differentphylawereidentified.

Firmicutes,Proteobacteria,Bacteroidetes,Thermotogae,Euryarchaeota(methanogens),andmsbl6 (candidatedivision)werethedominantphylaoftheanaerobictreatmentplantand repre-sented21.7%,18.5%,11.5%,9.4%,8.9%,and8.8%ofthetotalbacteriaidentified,respectively. ThedominantbacteriaisolatedwereClostridium,Bacteroides,Desulfobulbus,Desulfomicrobium, DesulfovibrioandDesulfotomaculum.Ourresultsrevealedthepresenceofnewspecies, gen-eraandfamiliesofmicroorganisms.Themostinterestingstrainswerecharacterised.Three newbacteriainvolvedinanaerobicdigestionofabattoirwastewaterwerepublished.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradeMicrobiologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisis anopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

For hygienic reasons, abattoirs use copious amounts of waterintheirprocessingoperations(slaughteringand clean-ing), which createssignificant wastewater. In addition, the increaseduseofautomatedmachinestoprocesscarcasses, alongwiththeincorporationofwashingateverystage,has increasedwaterconsumptioninslaughterhousefacilities.The

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:marie-laure.fardeau@univ-amu.fr(M.-L.Fardeau).

highfatandproteincontentofslaughterhousewastemakes wastewateragoodsubstrateforanaerobicdigestion,dueto itsexpectedhighmethaneyield.1Numerousmicroorganisms areinvolvedintheanaerobicdegradationofslaughterhouse waste,anystepofwhichmayberate-limitingdependingon thewastebeingtreatedaswellastheprocessinvolved.

Themicroorganismsinvolvedinanaerobicdigestionhave not been fully identified; however, at least four groups of microorganismsareinvolvedinthisprocess.2Thefirstgroup

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjm.2015.11.029

1517-8382/©2015SociedadeBrasileiradeMicrobiologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCC BY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

arethehydrolyticbacteriathatdegradecomplexcompounds (protein, carbohydrates, and fat) into simpler compounds, such as organic acids, alcohols, carbon dioxide (CO2) and

hydrogen.Thesecondgrouparethehydrogenproducing ace-togenicbacteriathatuseorganicacidsandalcoholstoproduce acetateandhydrogen.Thethirdgroupcontains homoaceto-genicbacteriathatcanonlyformacetatefromhydrogen,CO2,

organicacids,alcohols,andcarbohydrates.Thefourthgroup comprises methanogens that form methane from acetate, CO2,andhydrogen.Hydrolytic,acetogenic,andmethanogenic

microorganisms play an equally important role in anaer-obic digestion and methane production. Optimal methane productionisonlyachieved via the interaction ofmultiple microorganisms,3andtherefore,biodegradationofmolecules inwastewaterdependsontheactivityofallmicrobialgroups involved.

CommonfermentativebacteriaincludeLactobacillus, Eubac-terium,Clostridium,Escherichia coli,Fusobacterium, Bacteroides, Leuconostoc,andKlebsiella.Acetogenicbacteriainclude Aceto-bacterium,Clostridium,andDesulfovibrio.2 Methaneproducing organismsareclassifiedunderdomainArchaeaandphylum Euryarchaeota.4

In order to better understand the function of a bac-terial population, a detailed description of the microbial ecosystemis necessary.One methodisvia molecular biol-ogytechniques.5Recentadvancesinthemolecularanalysis ofbacterialecosystemsallowabetterunderstandingofthe specificmicroorganisms involved inwastewatertreatment. Thereareonlyafewstudiesfocusedonmicrobialpopulations, diversityandevolutioninreactorsfedwithcomplexorganic wastes.1 Therefore, little is known about the composition of these reactors. The development of advanced molec-ular biology techniques has contributed to the detection, quantification,andidentificationofthebacterialpopulations involvedinthetreatmentofabattoirwastewater.Forexample, cloningandsequencingof16SrRNAgenefragmentsprovide information about the phylogeny of the microorganisms. Additionally, single stranded conformation polymorphism (SSCP)offersasimple,inexpensiveandsensitivemethodfor detecting whether or not DNA fragments are identical in sequence,andcangreatlyreducetheamountofsequencing necessary.6

This work aimed to study the bacterial ecology of an anaerobicdigestorthroughbothbacterialcultureand molec-ular biological techniques. The bacteria involved in the anaerobic digestion of abattoir wastewater were identified using classic microbiology techniques and molecular tools (sequencingof16SrRNAandSSCP).Additionally,ourresults were compared with those of Gannoun et al.6 to evaluate theeffectofstorageat4◦Conthebacterialdiversityofthe sludge.

Material

and

methods

Originofthesludge

Anaerobic sludge samples were collected from an upflow anaerobic filter thattreats abattoirwastewaterinTunisia.7 Thedigestoroperatedunderbothmesophilic(37◦C)and ther-mophilic(55◦C)conditions.Samplesweretakenattheendof thermophilicphaseandstoredat4◦C.Thesludgewasthen analysedtodeterminethebacterialdiversitypresent,firstvia bacterialculture.

DNAextraction,PCRandSSCPanalysisofthedigestor sludge

Four milliliters of the anaerobic sludge sample were cen-trifugedat6000rpmfor10min.Pelletswerere-suspendedin 4mLof4Mguanidinethiocyanate–0.1MTrispH7.5and600L ofN-lauroylsarcosine10%.Twohundredandfiftymicrolitres oftreatedsamplesweretransferredin2mLtubesandstored at−20◦C.

Extraction and purification of total genomic DNA was implementedaccordingtotheprotocoldevelopedbyGodon etal.8

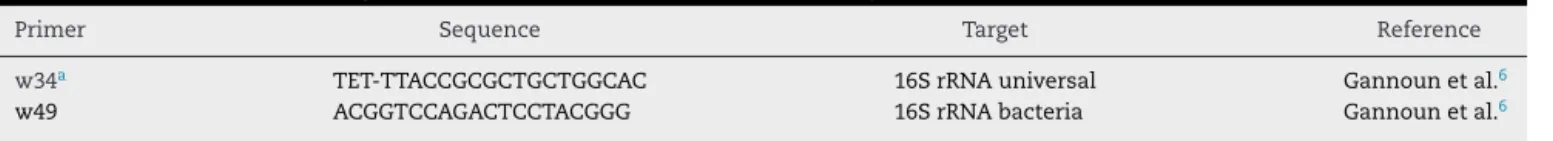

HighlyvariableV3regionsofbacterial16SrRNAgeneswere amplifiedbyPCRusingbacterial(w49–w34)primers(Table1). Samples were treated according to the protocol previously describedbyDelbèsetal.9

For electrophoresis, PCR–SSCP products were diluted in water before mixing with 18.75L formamide (Genescan-Applied Biosystems) and 0.25L internal standards (ROX, Genescan-Applied Biosystems) according tothe protocolof SSCPdescribedbyDelbèsetal.9

SSCPanalyseswereperformedonanautomaticsequencer abi310 (Applied Biosystems). RNA fragment detection was done on the fluorescent w34 primer. The resultsobtained wereanalysedbyGeneScanAnalysis2.0.2Software(Applied Biosystems)asspecifiedbyGannounetal.6Forbacterial iden-tification, pyrosequencingofthe DNA samplesusing a454 protocol was performed (Research and Testing Laboratory, Lubbock,USA).

Methodsofanalysisforpyrosequencingdatausedherein have been described previously.10–14 Sequences are first depleted of barcodes and primers. Then, short sequences under200bpareremoved,sequenceswithambiguousbase callsare removed, and sequenceswith homopolymerruns exceeding 6bp are removed. Sequences are then denoised and chimeras removed. Operational taxonomic units were definedafterremovalofsingletonsequences,clusteringat3% divergence(97%similarity).15–21Operationaltaxonomicunits

Table1–Sequencesandtargetpositionsofprimersusedinthisstudy.

Primer Sequence Target Reference

w34a TET-TTACCGCGCTGCTGGCAC 16SrRNAuniversal Gannounetal.6

w49 ACGGTCCAGACTCCTACGGG 16SrRNAbacteria Gannounetal.6

were then taxonomically classified using BLASTn against a curated GreenGenes database22 and compiled into each taxonomic level into both “counts” and “percentage” files. Countsfilescontaintheactualnumberofsequences,while the percentage files contain the percentage of sequences withineach samplethatmap tothedesignated taxonomic classification.

Enrichmentandisolationproceduresoffermentativeand SRBbacteria

TheHungate technique23 was used throughoutthis study. Inoculationswere done with10% ofculture.Sampleswere collectedfromtheanaerobicfilterattheendofthermophilic phase.A0.5mLaliquotofsamplewasinoculatedintoHungate tubescontaining5mLofbasalmedium.

ForbothSRB andfermentativebacteria, enrichmentand isolationwasdoneaccordingtotheprotocoldescribed previ-ouslybyHungate23andKhelifietal.5

PurificationoftheDNA,PCRamplificationandsequencing ofthe16SrRNAgeneofisolatedbacteria

Purification of the DNA, PCR amplification and sequenc-ing of the 16S rRNA gene were performed as described previously.24 Thepartialsequences generatedwere assem-bledusingBioEditversion5.0.925andtheconsensussequence of1495nucleotideswas correctedmanually forerrors. The most closely related sequences in GenBank (version 178), theRibosomalDatabaseProject(release10)identifiedusing BLAST,26andtheSequenceMatchprogram,27wereextracted and aligned. The consensus sequence was then adjusted manually toconform tothe 16S rRNA secondary structure model.28Nucleotideambiguitieswereomittedand evolution-ary distances were calculated using the Jukes and Cantor option.29DendrogramswereconstructedwiththeTREECON programusingtheneighbor-joiningmethod.30Treetopology was re-examined by the bootstrap method (1000 replica-tions) of re-sampling.31 Its topology was also supported using the maximum-parsimony and maximum-likelihood algorithms.

Dataanalyses

Thetwomainfactors taken into accountwhen measuring diversityarerichness andevenness.Richnessisameasure ofthe numberofdifferentkindsoforganismspresent ina particularsample.Evenness(Es)compares thesimilarity of populationsizes betweeneach ofthe speciespresent. The reciprocalofSimpson’sindex(diversityrichness)(1/D),which iswidelyusedforecologicalstudies,wasalsousedasa mea-sureofdiversity.Richnessandevennesswerecalculatedand interpretedasdescribed previouslybySimpson32and Gan-nounetal.6

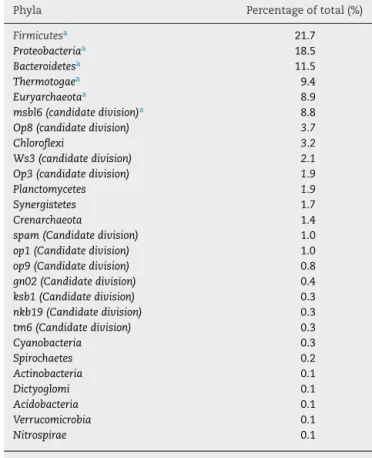

Table2–Thedifferentphylafoundinthedigestor.

Phyla Percentageoftotal(%)

Firmicutesa 21.7 Proteobacteriaa 18.5 Bacteroidetesa 11.5 Thermotogaea 9.4 Euryarchaeotaa 8.9 msbl6(candidatedivision)a 8.8

Op8(candidatedivision) 3.7

Chloroflexi 3.2

Ws3(candidatedivision) 2.1 Op3(candidatedivision) 1.9

Planctomycetes 1.9

Synergistetes 1.7

Crenarchaeota 1.4

spam(Candidatedivision) 1.0

op1(Candidatedivision) 1.0

op9(Candidatedivision) 0.8

gn02(Candidatedivision) 0.4 ksb1(Candidatedivision) 0.3 nkb19(Candidatedivision) 0.3 tm6(Candidatedivision) 0.3 Cyanobacteria 0.3 Spirochaetes 0.2 Actinobacteria 0.1 Dictyoglomi 0.1 Acidobacteria 0.1 Verrucomicrobia 0.1 Nitrospirae 0.1

a Themostcommonphyla.

Results

and

discussion

Diversityandabundanceofthebacterialcommunitiesin thebioreactorsludgeusingSSCPandDNAsequencing

Therewassignificantmicrobialdiversityoftheupflow anaer-obic filter, which operated under both mesophilic (37◦C) and thermophilic (55◦C)conditions. Twenty-sevendifferent phylawereidentified,andthesixmostcommonphyla

(Fir-micutes,Proteobacteria,Bacteroidetes,Thermotogae,Euryarchaeota

(themethanogenicbacteria),andthemsbl6(candidate divi-sion)) represented 78.8% of the total (Table2). The21 less commonphylarepresented21%ofthetotal.

Gram-positive bacteria, including Firmicutes (low G+C), were the most common type of bacteria in the anaerobic digestor, comprising21.7% ofthetotal. Both Gram-positive low G+C bacteria and the Bacteroidetes phylum are known for their fermentative properties. Furthermore Bacteroidetes

playanimportantroleinthedegradationofcomplex poly-mers.FirmicutesandBacteroidetesarealsothetwomaingroups encountered in the study by Godon et al.8 of a fluidised bed anaerobic digestorfedwith vinasse.These twogroups ofbacteriahydrolysethepolymersubstrates whicharenot degraded duringthepreviousstagesofanaerobic digestion (such aspolysaccharides, proteins and lipids) into acetate, longchainfattyacids,CO2,formateandhydrogen.

Bacteria within the Proteobacteria phylum were also commonlyfoundinthedigestor.TheseGram-negative bacte-ria are considered to be some of the most cultivable microorganisms .33,34 The Proteobacteria havean important

Table3–Themaingenusandspeciesofthedigestor.

Strain Percentage(%) Strain Percentage(%)

Kosmotogaspp.a 9.37 Cclostridiumacetireducens 0.97

msbl6(candidatedivision)a 8.75 Segetibacterspp. 0.97

Desulfotomaculumthermocisternuma 6.25 Clostridiumlimosum 0.90

Rriemerellaanatipestifera 5.48 Sulfurovumlithotrophicum 0.90

Pelotomaculumthermopropionicuma 4.44 op9(candidatedivision) 0.83

op8(candidatedivision)a 3.68 Achromatiumoxaliferum 0.83

Tthiohalomonasdenitrificansa 3.12 Ureibacillussuwonensis 0.76

Thermobaculumterrenuma 3.12 Desulfobacteriumcatecholicum 0.76

Desulfobulbuselongatusa 2.63 Synergistesspp. 0.76

Methanobacteriumspp.a 2.43 Desulfomicrobiumspp. 0.76

Dysgonomonasmossiia 2.22 Desulfobulbusspp. 0.69

Caldanaerobacteruzonensisa 2.15 Methanobacteriumbeijingense 0.62

ws3(candidatedivision)a 2.08 Pseudomonasresinovorans 0.62

op3(candidatedivision)a 1.94 Rhodovibriosalinarum 0.55

Pirellulaspp.a 1.66 Legionellabirminghamiensis 0.55

Methanobacteriumaarhusensea 1.45 Methanosaetathermophila 0.55

Nitrosococcusoceania 1.45 Acetobacteriumwieringae 0.55

Coprococcusclostridiumsp.ss2/1a 1.38 Thermanaerovibrioacidaminovorans 0.55

Methanosphaerulapalustrisa 1.11 Thermosinuscarboxydivorans 0.55

Parabacteroidesgoldsteiniia 1.04 Ruminococcusflavefaciens 0.48

Candidatusnitrososphaeragargensisa 1.04 Methanosaetaspp. 0.48

spam(candidatedivision)a 1.04 Rhodovulumeuryhalinum 0.48

op1(candidatedivision)a 1.04 Thermomonasfusca 0.48

Methanobrevibactercurvatus 0.97 Mechercharimycesmesophilus 0.41

The48mostabundantspeciesinthesample.

a Thefirst23speciesaretheprominentonesbasedonthePCR-SSCPandmicrobiologicalmethods.

role in the hydrolysis and acetogenesis steps of anaero-bicdigestion,and includedelta,gammaand betavarieties.

Deltaproteobacteriacontainsmanysyntrophicanaerobic bacte-ria, which participate in sulphate reduction. Among the

Gammaproteobacteria,therearemanydenitrifyingbacteriaor bacteriathataccumulatephosphates.35TheBetaproteobacteria areinvolvedinnitrification,andarepotentiallyalsoinvolved indenitrification.

PhylogeneticanalysisofthedomainBacteriaalsohelped tohighlightthe existenceofapoorlyknown order, Thermo-togales,whichwasrelativelyabundantwithinthedigestorat 9.4%.Thermotogalescontainsanaerobicbacteriathatare het-erotrophicwithafermentativemetabolism.36Thesebacteria arealsofoundinotheranaerobicdigestors.8

ThePlanctomycetalesgrouprepresented1.9%ofthe bacte-riawithinthe digestor. BacteriawithinPlanctomycetales are limitedtofivekindsandonlyeightspeciesaredescribed. Aer-obicheterotrophicPlanctomyceteshavebeensuccessfully iso-latedfrombrackishmarinesediments,freshwatersediments, soil,hotsprings,saltpitsandtissuesfromgianttigerprawn postlarvae.37,38 Inaddition,aspecialgroupofPlanctomycetes

wereimplicatedintheoxidationofammoniaunderanaerobic conditionsinwastewaterplants,coastalmarinesediments, andoceanicandfreshwateroxygenminimumzones.39 Fur-thermore,awidevarietyofPlanctomycetaleswerefoundduring analysisofsamplesfromaquaticanaerobicenvironments,a sulphide-andsulphur-richspring,activatedsludge wastewa-tertreatmentplantsandinanaerobicdigestors.8,38,39

TheChloroflexi represented 3.2%of the digestor’s bacte-ria.Chloroflexihavebeenidentifiedfrommanyenvironments through 16S rRNA gene profiling, including marine and freshwatersediments. Despitethis,the Chloroflexiremain a

relativelyunderstudiedbacteriallineage.Atpresent,thereare 19completegenomesavailablefortheChloroflexi.40

Tang et al.41 showed that three phylawere involved in the mesophilic anaerobic treatment of synthetic rejection containingbovineserum albumin:Bacteroidetes,followedby

FirmicutesandProteobacteria.InanotherstudybyFangetal.42 thatevaluatedtheanaerobicdegradationofphenolrich rejec-tion in anupflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactor, eightphylogenetic groupswere detected,namely Thermoto-gales (38.9% ofclones), Firmicutes(27.8%), Chloroflexi(11.1%),

candidatedivisionOP8(9.3%),candidatedivisionOP5(5.5%), Pro-teobacteria (3.7%), Bacteroidetes (1.9%) and Nitrospirae (1.9%). Theseresultsarecomparablewiththeresultsofourstudy.

TheEuryarchaeota,whichconsistmainlyofmethanogenic bacteria, represented 8.9%ofbacteria withinthe anaerobic digestor.TheCrenarchaeota,extremethermoacidophiles,were also detectedin the digestor with an abundance of 1.4%. Thedigestorseemstohavelimitedarchaealdiversity.These resultsaresimilartotheresultsofanotherstudyonthe bacte-rialdiversityofananaerobicdigestorfedwithvinasse,which containedonly4%ofArchaeaBacteriasequences.8

Overall,therewassignificantbacterialdiversitywithinthe digestor.Therewere23specieseachconsistingofgreaterthan 1%,andthemostabundantspecieswasKosmotogaspp.with apercentageof9.37%(Table3).

SSCPanalysisoftheeffectofstorageonthediversityand abundanceofbacterialcommunitieswithinthebioreactor sludge

SSCP analyses(Fig. 1) show the results of two samplesof sludge collected from the same digestorat the endof the

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 2324 2526 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 39 40 41 42 38 43 44 45 46 47 48 13 14 15 16 17 A B 19 C 18 20 D21E 23 24 26 27 28 29 F 32 34 35 36 31

After 2 months

Before 2 months

Fig.1–Effectofstorageonthedynamicsofsinglestrandconformationpolymorphismpatternsofbacterial16SrRNAgene amplificationproductsoftheanaerobicdigestor.

thermophilicphase.6Thesecondsamplewasstoredat4◦Cfor

twomonthsandshoweddifferentSSCPpatterns.The analy-sisofthetwoSSCPpatternsshowedsignificantchangeinthe bacterialcommunityovertime,whichcanbeexplainedbythe factthesludgeisnotstableovertime.

Thedynamicsofbacterialcommunitieswere monitored byPCR-SSCPmethods.Theprofileobtainedforthedomain Bacteriaisshown inFig. 1. TheSSCP pattern revealed the high diversity of bacteria, with at least 48 distinguishable peaksandabout23prominentpeaks.Thebacterialdiversity richness(1/D)andspeciesevenness(Es)wereusedasa mea-sureofdiversityandabundance.Theobtainedvalueswere 38.97(whichofferstowardthenumberofspeciesS=48) (indi-catedmaximumdiversity))and0.811(whichofferstowardto 1:speciesinthesamplearequiteevenlydistributed), respec-tively.Thisresultisinagreementwithothermolecularstudies basedonthePCR-SSCPmethods.

Severalresearchgroupsconfirmedourresultsand demon-stratedthatdiversityinbacterialdigestorsvariesdepending onseveralfactors.However,Zumstein etal.,43 who studied the communitydynamics inananaerobic bioreactor using fluorescencePCRsingle-strandconformationpolymorphism analysis,indicatedthatthroughouttheperiodofthe study, rapidsignificantshiftsinthespeciescompositionofthe bac-terialcommunityoccurred.Infact,thebacterialcommunity wasfollowedfortwoyearsthroughtheanalysisof13SSCP pat-terns,withoneSSCPpatterneverytwomonths.Theanalysis oftheSSCPpatternsshowedacontinuouschangeinthe bac-terialcommunityduringthattime.Typically,amicroorganism initiallypresentatlowlevelsinthecommunitygrew,peaked

and decreased. Moreover,somemicroorganismsseemed to fluctuatesimultaneously.

Keskesetal.44studiedtheeffectoftheprolongedsludge retention time on bacterial communities involved in the aerobic treatment of abattoir wastewater by a submerged membrane bioreactor.Their results showedthat the biodi-versityvariedsignificantlyinrelationwiththeenvironmental conditions,particularlyTSS.

Thesludgemicroorganismsandassociationsof microor-ganismsmayoccupythesameecologicalnichesuccessively. They could correspond to the ecological unit called an ecotype.45

Isolationandidentificationofbacteria

Fermentative bacteria and SRB involved in the anaero-bic digestion of organic matter in abattoir effluents were investigatedbytwo approaches:classical microbiology and moleculartaxonomy.

The isolation ofbacteria is preceded byan enrichment phase which favors the growth of a given microorganism (fermentative bacteria or SRB), selected according to the physicalandnutritionalconditionsofthemediumcategory. For thispurpose,twodifferentculturemediawereused,as described in the Materials and Methods section. The first culturemediumwasspeciallydesignedforthedetectionof fermentativebacteria andthe secondforSRB. Bothculture mediaweretestedat37◦Cand55◦C.Glucosewasusedasan energysourcetoisolatefermentativebacteria,whereas lac-tate,acetateandH2CO2werereservedfortheisolationofSRB.

Table4–Phylogeneticaffiliationofthe16SrRNAbacteriasequencesofisolatedstrains.

Name Closestneighbor Accessionnumber Origin References Similarity(%)

Mesophilicfermentativebacteria(37◦C)

LIND8L2 Clostridiumnovyi AB041865 Soilandfeces Sasakietal.49 96%

LIND7Ha Parabacteroidesmerdae AB238928 Humanfeces Johnsonetal.51 91%

LIND8A Clostridiumsp13A1 AY554421 Anaerobicbioreactortreating

cellulosewaste

Burrelletal.50 99%

LINBA ClostridiumspD3RC-2 DQ852338 Rumenyakchina Zhangetal.48 99%

LINBL1 ClostridiumspD3RC-2 DQ852338 Rumenyakchina Zhangetal.48 99%

LINBA2 ClostridiumspD3RC-2 DQ852338 Rumenyakchina Zhangetal.48 99%

LIND8A ClostridiumspD3RC-2 DQ852338 Rumenyakchina Zhangetal.48 96%

Thermophilicfermentativebacteria(55◦C)

LIND6LT2a Parasporobacterium

paucivorans

AJ272036 Anaerobicdigestortreatingsolid

waste

Lomansetal.57 87%

LIND8AT Unculturedbacterium DQ125705 Soilscontaminatedwithuranium

waste

Brodieetal.59 97%

LINBAT1 Unculturedbacterium AF280825 Anaerobicdigestortreating

pharmaceuticalwastes

Laparaetal.60 99%

LINBLT2 Unculturedbacterium AF280825 Anaerobicdigestortreating

pharmaceuticalwastes

Laparaetal.60 98%

LIND4FT1 Caloramatorcoolhaasii AF104215 Anaerobicthermophilicgranular

sludge

Pluggeetal.61 96%

LIND8HT Lutisporathermophila AB186360 Thermophilicbioreactordigesting

municipalsolidwastes

Shiratori

etal.62

99%

LINBLT Clostridium

thermosuccinogenes

Y18180 Cattlemanure,beetpulp,soil,

sedimentpond

Stackebrandt

etal.72

98%

LINBHT2 Clostridiumtertium Y18174 Openwarwounds Stackebrandt

etal.72

98%

Mesophilicsulphate-reducingbacteria(37◦C)

LINBL Desulfobulbuspropionicus AY548789 Fluidized-bedreactorstreatingacidic,

metal-containingwastewater

Kaksonen67 99%

LINBH Desulfovibriovulgaris AE017285 Soil,animalintestinesandfeces,fresh

andsaltwater

Heidelberg

etal.68

99%

LINBH2 Desulfovibriovulgaris AE017285 Soil,animalintestinesandfeces,fresh

andsaltwater

Heidelberg

etal.68

99%

LINBA1 Desulfomicrobiumbaculatum AJ277895 Water-saturatedmanganese

carbonateore

Hippe73 99%

LINBH1 Desulfomicrobiumbaculatum AJ277895 Water-saturatedmanganese

carbonateore

Hippe73 99%

Thermophilicsulphate-reducingbacteria(55◦C)

LINBHT1a Desulfotomaculumhalophilum U88891 Oilproductionfacilities

Tardy-Jacquenod

etal.69

89%

a ThesestrainswerecharacterizedandpublishedLIND7H,55LIND6LT258andLINDBHT1.71

Isolationandcultureofbacteriaallowedustostudythe biodiversityofthese bioreactors aswell ashighlighted the dominantbacteriainthedifferentconditionstested.The iso-lation of the different strains was carried out on an agar medium.Thisstephelpedtoisolatestrainsthatare identi-fiedbasedontheirmorphologicaldifferences(size,shape,and color).

Following this step, molecular analysis of the isolated strainswasperformed.AfterextractionofthebacterialDNA, the16SrDNAwasamplifiedbyPCR.Thequalityofthe ampli-fiedDNAwasvisualisedwithultra-violetlightaftermigration on gel agarose at 1%. The PCR product was subsequently sequencedtoidentifythedifferentstrains.Thegenescoding for16SrRNAhavebeenchosenastaxonomicmarkers,asthey haveauniversaldistributionandconservedfunction.These

genespossessbothhighlyconservedareas,providing infor-mationontheevolutionofdistantspecies,andvariableareas, todifferentiateorganismsbelongingtothesamegenus,and eventuallythesamespecies.46

Each microorganism was then identified by comparing the 16S rDNAsequences withthoseofknown microorgan-isms,andeachwascatalogedincomputerdatabases.Given the large number ofisolated bacteria in recent underwent restrictionanalysisbyARDRAtechniquetoeliminateidentical strainsrestrictionprofilestokeeponlytheamplifiasof dif-ferentstrainsprioriwhichwillbetheobjectofphylogenetic studies.Phylogeneticaffiliationsofthe16SrRNAofbacteria sequencesarepresentedinTable4withtheclosestrelatives ofisolatedmesophilicandthermophilicfermentativebacteria andSRB.

5%

LIND8AT-1131bp

Caloramator fervidus

Clostridium grantii Clostridium cellulovorans

Caloramator viterbiensis

Clostridium hungatei Clostridium ganghwense

Caloramator proteolyticus

LIND8A-1125bp LINBHT2-1119bp

Caloramator uzoniensis

LINBL1-1118bp Clostridium thermocellum Clostridium populeti LIND6LT2-1123bp Clostridium quinii Clostridium carnis

I lyobacter delafieldiii Clostridium homopropionicum

LIND8L2-1104bp

Clostridium thermopalmarium Clostridium novyi

Clostridiumhaemolyticum

Clostridium disporicum Clostridium celatum

Clostridium tertium Clostridium sartagoforme

LINBA2-1129bp LINBA-1122b p

LINBLT2-1132b p LINBAT1-1134 bp

Clostridium indolis Anaerostipes caccae

LIND8HT-1116bp

Gracilibacter thermotolerans

Clostridium aldrichii Acetivibrio cellulolyticus

LINBLT-1137b p

Clostridium thermosuccinogenes Clostridium josui

Clostridium cellulolyticum Clostridium termitidis

Clostridium cellobioparum

LIND4FT1-1130bp

Caloramator coolhaasii

Thermobrachium celer Caloramator indicus

100 100 75 93 93 71 100 100 100 94 87 78 97 100 100 100 95 100 83 80 100 99 100 97 100 100 100 100 100 100 87 98 99 100

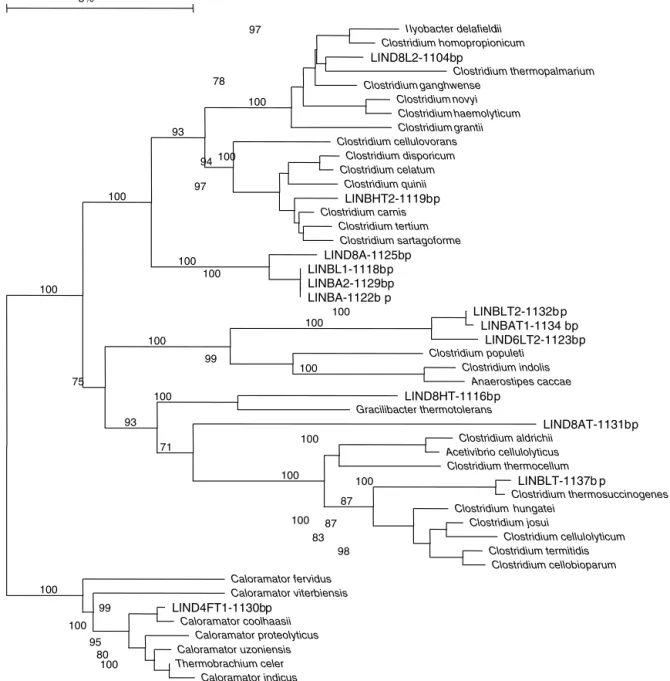

Fig.2–Phylogenetictreebasedonthegeneencodingthe16SRNAshowingthepositioningoffermentativemesophilicand thermophilicbacteriaisolatedfromtheanaerobicdigestor.

Fermentativebacterialcommunitiesinthebioreactor sludge

StrainsLINBA,LINBL1,LINBA2areclosestphylogeneticallyto

Clostridium sp. D3RC-2 with apercentage sequence similar-ityof99%.Thisbacteriumwasfirstlydetectedintherumen ofayakinChina47,48 butitisnotyetdescribed.Thestrain LIND8Ashares96%ofsequenceswithClostridium sp. D3RC-2.This strain seems tobe anew speciesand differs from the latter. Thestrain LIND8L2 hasalso been recently affil-iated with Clostridiaspecies. LIND8L2 isa strain similar to

Clostridiumnovyi with96%sequencesimilarity.C.novyi isa pathogenicbacteriumphylogeneticallyclosetoC.botulinum

andC.haemolyticum.49TheneareststraintoLIND8Ais

Clostrid-iumsp13A1,previouslyisolatedfromananaerobicbioreactor treating cellulose wastes,50 with 99% sequence similarity.

TheclosestphylogeneticrelativesofthestrainLIND7HTare Parabacteroidesmerdae,51P.goldsteinii52,53andP.gordonii,54with 91.4%,91.3%and91.2%sequencesimilarity,respectively.This novelstrainwasidentifiedandcharacterisedbyJabarietal.55 Onthebasisofphylogeneticinferenceandphenotypic prop-erties,LIND7HTisproposedasthetypestrainofanovelgenus

andspecieswithinthefamilyPorphyromonadaceae, Macellibac-teroidesfermentansgen.nov.,sp.nov.

Strainsisolatedinmesophilicconditionsweredetermined to belong to Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, which are known fortheirfermentativeactivityandwhicharethetwogroups mainly encountered in the study by Godon et al.8 on an anaerobicdigestor.Theyhydrolysethepolymersubstratesnot degradedduringthestagesofremediation(suchas polysac-charides,proteinsandlipids)toacetate,longchainfattyacids, CO2,formateandhydrogen.

Desulfomicrobium orale

Desulfotomaculum carboxydivorans

Desulfomicrobium hypogeium

Desulfovibrio oryzae

Desulfotomaculum geothermicum

Desulfobulbus elongatus

Desulfovibrio vulgaris subsp. vulgaris

LINBHT1-1121bp

Desulfomicrobium baculatum

LINBA1-1165bp LINBH1-1149bp

Desulfomicrobium sp. 'Delta +'

Desulfomicrobium escambiense

Desulfomicrobium norvegicum

Desulfomicrobium apsheronum

LINBH2-1157bp LINBH-1150bp

Desulfovibrio intestinalis

Desulfovibrio desulfuricans subsp. desulfuricans

Desulfovibrio pigra

Desulfovibrio fairfieldensis

Desulfobulbus rhabdoformis

Desulfobulbus mediterraneus

Desulfobulbus propionicus

LIN.BL-1157bp

Desulfotomaculum halophilum

Desulfotomaculum alkaliphilum

5% 100 100 100 93 100 100 100 99 97 100 92 76 100 97 89 99 81 98 71

Fig.3–Phylogenetictreebasedonthegeneencodingthe16SRNAshowingthepositioningofSRBisolatedfromthe anaerobicdigestor.

The isolation of fermentative, thermophilic bacteria obtainedsomestrainsclassified as“uncultured bacterium” indicatingtheycannotbegrownonsyntheticmaterialina laboratory.ThesestrainsareLIND6LT2,LIND8AT,LINBAT1and LINBLT2. The strain LIND6LT2 was detectedin an anaero-bicdigestortreatingsolidwasteinthermophilicconditions.56 Theclosestphylogeneticrelativetothisstrainis Parasporobac-terium paucivorans with 87.17% sequence similarity.57 This novelstrainwasinitiallyidentifiedandcharacterisedbyJabari et al.58 On the basis of phylogenetical and physiological properties, the strain LIND6LT2T is proposed as the strain

typeof Defluviitaleasaccharophila gen. nov., sp.nov., placed inDefluviitaleaceae fam.nov., withinthe phylum Firmicutes,

classClostridia,orderClostridiales.ThestrainLIND8AThas97% similaritywithastrainclassifiedasuncultivablebacterium, probablyinvolvedinmetalreduction.59

Accordingtothephylogenetictree(Fig.2),thestrains LIN-BAT1andLINBLT2arephylogeneticallyclose.Thesesequences were also identified within an anaerobic digestor treat-ing pharmaceutical wastes.60 The closest relative tostrain LIND4FT1isCaloramatorcoolhaasii,with96%sequence similar-itywhichsuggeststhatthisstrainisanewspecies.C.coolhaasii

hasbeenisolatedfrom ananaerobic granularsludge biore-actorthatdegradesglutamate.Itismoderatelythermophilic andstrictlyanaerobic.61LIND8HTstrainisclosetoLutispora

thermophile,62 with 99%sequence similarity whichis firstly isolatedfromanenrichmentculturederivedfroman anaer-obicthermophilic bioreactor treatingartificial solid wastes.

StrainsLINBLTandLINBHT2wereaffiliatedwithC.tertiumand

C. thermosuccinogenes,respectively, each with98% sequence similarity.

The mesophilic and thermophilic fermentative strains which were isolatedwere alsodesignated tothe group Fir-micutes,whichseemstobethemostabundantgroupinour anaerobic digestor. Almostall isolateswere representedby

Clostridium species. This is not surprising, because during the hydrolysis phase in bioreactors, macromolecules such as polysaccharides, lipids, proteins and nucleic acids are cleaved,typicallybyspecificextracellularenzymes, produc-ing monomers (monosaccharides, fatty acids, amino acids andnitrogenbases)whicharetransportedintothecellwhere theyarefermented.Thebacteriainvolvedinthisstagehave a strictly anaerobic or facultative metabolism. During the acidogenesis phase, these monomers are metabolised by fermentative microorganisms toprimarily produce volatile fatty acids(acetate,propionate,butyrate, isobutyrate, valer-ate and isovalerate), but alsoalcohols, sulphide(H2S), CO2

and hydrogen.Acidogenesisleadstosimplified productsof fermentation,andthebacteriainvolvedinthisstepmaybe facultativeorstrictlyanaerobic.Strictlyanaerobicbacteriaof thegenusClostridiumareoftenalargefractionofthe popula-tionparticipatingintheanaerobicstepofacidformation.

Fermentativebacteriawereabundant,particularlythe pro-teolyticClostridiumspecies.Thesespecieshydrolyseproteins to polypeptides and amino acids, while lipids are hydrol-ysed via oxidation to long-chain fatty acids, and glycerol

0.02

Desulfotomaculum halophilum SEBR 3139 LINBHT1-1121bp

Clostridium sp.9B4

Desulfovibrio oryzae Clostridium populeti ATCC 35295 LINBA2-1129bp LIND6LT2-1123 bp Desulfomicrobium baculatum DSM 1742 Desulfobulbus elongatus DSM 2908 LINBL1-1118bp LIN.BA-1122bp Clostridium sp.D3RC-2 LIND8A-1125bp LIND8A'-GATC-F1

Clostridium subterminale ATCC 25774 Clostridium sp. str. RPec1 LIND8L2-1104bp Ilyobacter delafieldii str. 10cr1 DSM 5704 LINBHT2-1119bp Clostridium sp. str. WV6. LIND4FT1-1130bp Caloramator coolhaasii str. Z LINBAT1-1134 bp LINBLT2-1132bp LINBLT-1137bp Clostridium aldrichii DSM 6159 LIND8HT-1116bp str. 16SX-1 LIND8AT-1131bp clone OPB54 LIND7H-1107bp

Bacteroides ASF519 str. ASF 519. LIN.BL-1157bp Desulfobulbus propionicus LINBH1-1149bp LINBA1-1165bp LINBH2-1157bp LIN.BH-1150bp Desulfovibrio vulgaris DSM 644 Desulfovibrio sp. str. DMB 100 98 93 73 97 89 100 100 89 97 100 100 96 74 100 100 100 81 100 100 100 100 99 100 100 100 100 100 91 100

Fig.4– Phylogenetictreebasedonthe16SRNAgeneofbacteriaisolatedfromdigestortreatingabattoirwastewaters.

andpolycarbohydratesarehydrolysedtosugarsandalcohols. Afterthat,fermentativebacteriaconverttheintermediatesto volatilefattyacids,hydrogenandCO2.6

Sulphate-reducingbacterialcommunitiesinthesludge bioreactor

Sulphate-reducingbacteriawere isolatedinmesophilicand thermophilic conditions on various substrates. In anaero-bicdigestion,the acidogenesisproductsare converted into acetateandhydrogenintheacetogenesisphase.Thehydrogen isnormallyusedbythemicrobialcommunity’smethanogenic hydrogenophiles to reduce CO2 to methane (CH4) while

acetateisconvertedbymethanogenicacetoclastestoCH4.

The presence of sulphate in the medium may change theflowofthesubstrateavailableformethanogens.Infact, theSRB mayoxidiseaportion ofthesubstrate (mainlyvia the hydrogen) using sulphate as an electron acceptor. In suchsituations,thesubstrateisconvertedtosulphurifthe pHof the medium isacidic. These methanogenic bacteria cantherefore competewithother bacterialgroupssuch as sulphate-reducingbacteria.63 TheSRBmayalsobeinvolved inthehydrolysis64andacetogenesissteps.65Inaddition,the SRBareknowntoplayakeyroleinthebiodegradationofa numberofenvironmentalpollutants.66

ThestrainLINDBL,isolatedat37◦C(Table4)inthe pres-enceof20mMlactate,ismostcloselyrelatedtoDesulfobulbus propionicuswitha99%sequencesimilarity.D.propionicuswas firstisolatedfromafluidisedbedbioreactortreatingeffluent containingacidandmetals.67 StrainsLINDBHandLINDBH2 wereaffiliatedphylogeneticallytoDesulfovibriovulgariswith 99%sequence similarity.Bothstrainswere isolatedat37◦C onbasalmediumsupplementedwithH2CO2(2bars)asa

sub-strate.D.vulgarisisusedasamodelforthestudyofSRBto analysethemechanismsofmetalcorrosionandtotreattoxic metalionsfromtheenvironment.68

LINDBA1and LINDBHT1aretwo mesophilicstrainsthat were isolatedonbasalmediumforSRBusingtwodifferent substrates, the first one inthe presenceof 20mM acetate and the second onein the presence of H2CO2 (at 2 bars).

ThesestrainshaveDesulfomicrobiumbaculatumastheirclosest relative,with99%sequencesimilarity.Phylogeneticanalysis demonstratedthatthestrainLINDBHT1Tbelongedwithinthe

genusDesulfotomaculum.Thisstrain(LINDBHT1T)had Desul-fotomaculumhalophilum69andDesulfotomaculumalkaliphilum70 as its closest phylogenetic relatives with approximately 89% sequence similarity. LINDBHT1T is a novel anaerobic

thermophilic sulphate-reducing bacterium. This bacterium constitutesanewspeciesofthegenusDesulfotomaculum,D. peckii71(Fig.3).

Various SRB were isolated from the anaerobic digestor whichshowsthattheyareinvolvedinthedegradation pro-cess.Inordertogainanoverallideaofthecultivablebacterial diversityofthedigestor,wegroupedallofthebacteriaisolated ontothesamephylogenetictree(Fig.4).

Analysis of the microbial populations obtained from the anaerobic sludge samples in both mesophilic and thermophilicconditionsledtotheisolationofmany morpho-logicallydistinctbacteria. Molecularand microbialanalyses showedthatfermentativebacteria(primarilyClostridiumspp. andParabacteroidesspp.),Desulfobulbusspp.,Desulfomicrobium

spp., Desulfovibrio ssp. and Desulfotomaculum ssp. were the prominentmembersofthebacterialcommunityinthe biore-actor(Fig.4).Thediversityofthemicrobialcommunitywithin thedigestormayreflectthemetabolicdiversityof microor-ganismsinvolvedinanaerobicdigestion.Theinteractionsof thiscomplexmicrobialcommunityallowsforcomplete degra-dationofnaturalpolymerssuchaspolysaccharides,proteins, lipidsandnucleicacidsintomethaneandcarbondioxide.

Conclusion

Inconclusion,theuseofbothbacterialcultureand molecu-lartechniquesenabledustoestablishapictureoftheexisting microbialbiodiversityinananaerobic digestor.Theculture approach was essential, especially with regard to culture and/orisolationofmicroorganismswithnoknowncultivable representative.Furtherresearchinthisareacanonlyimprove ourknowledgeofmicrobialanaerobicdigestors,includingthe role of different microbial populations involved in anaero-bicdegradationofwaste,whichwillimprovecontrolofthese treatmentprocesses.Acomprehensivemolecularinventory wouldalsosupportandcomplementourstudyofthe micro-bialdiversityofanaerobicculturesasitwouldlinkinformation on thediversity and functionofmicrobial communitiesin theirenvironment.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorshavenoconflictofinteresttodeclare.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1. ChasteenTG,FuentesDE,TantaleánJC,VásquezCC. Tellurite:history,oxidativestress,andmolecular mechanismsofresistance.FEMSMicrobiolRev. 2009;33:820–832;

ChenYT,ChangHY,LaiYC,PanCC,TsaiSF,PengHL. Sequencingandanalysisofthelargevirulenceplasmid pLVPKofKlebsiellapneumoniaeCG43.Gene.2004;337:189–198; ScherrKE,LundaaT,KloseV,BochmannG,LoibnerAP. Changesinbacterialcommunitiesfromanaerobicdigesters duringpetroleumhydrocarbondegradation.JBiotechnol. 2012;157:564–572;

PalatsiJ,Vi ˜nasM,GuivernauM,FernandezB,FlotatsX. Anaerobicdigestionofslaughterhousewaste:mainprocess limitationsandmicrobialcommunityinteractions.Bioresour Technol.2011;102:2219–2227.

2.HassanAN,NelsonBK.Invitedreview:anaerobic fermentationofdairyfoodwastewater.JDairySci. 2012;95:6188–6203.

3.ChartrainM,BhatnagarL,ZeikusJG.Microbialecophysiology ofwheybiomethanation:comparisonofcarbon

transformationparameters,speciescomposition,andstarter cultureperformanceincontinuousculture.ApplEnviron Microbiol.1987;53:1147–1156.

4.BooneDR,CastenholzRW.Bergey’sManualofSystematic Bacteriology.vol.1,2nded.NewYork,NY:Springer-Verlag; 2001.

5.KhelifiE,BouallaguiH,FardeauML,etal.Fermentativeand sulphate-reducingbacteriaassociatedwithtreatmentofan industrialdyeeffluentinanup-flowanaerobicfixedbed bioreactor.BiochemEngJ.2009;45:136–144.

6.GannounH,KhelifiE,OmriI,etal.Microbialmonitoringby moleculartoolsofanupflowanaerobicfiltertreating abattoirwastewaters.BioresourTechnol.2013;142: 269–277.

7.GannounH,BouallaguiH,OkbiA,SayadiS,HamdiM. Mesophilicandthermophilicanaerobicdigestionof biologicallypretreatedabattoirwastewatersinanupflow anaerobicfilter.JHazardMater.2009;170:263–271.

8.GodonJJ,ZumsteinE,DabertP,HabouzitF,MolettaR. Molecularmicrobialdiversityofananaerobicdigestoras determinedbysmall-subunitrDNAsequenceanalysis.Appl EnvironMicrobiol.1997;63:2802–2813.

9.DelbèsC,MolettaR,GodonJ.Bacterialandarchaeal16S rDNAand16SrRNAdynamicsduringanacetatecrisisinan anaerobicdigestorecosystem.FEMSMicrobiolEcol.

2001;35:19–26.

10.WolcottRD,GontcharovaV,SunY,ZischakauA,DowdSE. Bacterialdiversityinsurgicalsiteinfections:notjustaerobic coccianymore.JWoundCare.2009;18:317–323.

11.BaileyMT,DowdSE,ParryNM,GalleyJD,SchauerDB,LyteM. Stressorexposuredisruptscommensalmicrobial

populationsintheintestinesandleadstoincreased colonizationbyCitrobacterrodentium.InfectImmun. 2010;78:1509–1519.

12.FinegoldSM,DowdSE,GontcharovaV,etal.Pyrosequencing studyoffecalmicrofloraofautisticandcontrolchildren. Anaerobe.2010;16:444–453.

13.GontcharovaV,YounE,SunY,WolcottRD,DowdSE.A comparisonofbacterialcompositionindiabeticulcersand contralateralintactskin.OpenMicrobiolJ.2010;4:8–19.

14.PittaDW,PinchakE,DowdSE,etal.Rumenbacterialdiversity dynamicsassociatedwithchangingfrombermudagrasshay tograzedwinterwheatdiets.MicrobEcol.2010;59:511–522.

15.DowdSE,CallawayTR,WolcottRD,etal.Evaluationofthe bacterialdiversityinthefecesofcattleusing16SrDNA bacterialtag-encodedFLXampliconpyrosequencing (bTEFAP).BMCMicrobiol.2008;8:125.

16.DowdSE,SunY,WolcottRD,DomingoA,CarrollJA.Bacterial tag-encodedFLXampliconpyrosequencing(bTEFAP)for microbiomestudies:bacterialdiversityintheileumofnewly weanedSalmonella-infectedpigs.FoodbornePathogDis. 2008;5:459–472.

17.EdgarRC.Searchandclusteringordersofmagnitudefaster thanBLAST.Bioinformatics.2010;26:2460–2461.

18.CaponeKA,DowdSE,StamatasGN,NikolovskiJ.Diversityof thehumanskinmicrobiomeearlyinlife.JInvestDermatol. 2011;131:2026–2032.

19.DowdSE,DeltonHansonJ,ReesE,etal.Surveyoffungiand yeastinpolymicrobialinfectionsinchronicwounds.JWound Care.2011;20:40–47.

20.ErenAM,ZozayaM,TaylorCM,DowdSE,MartinDH,Ferris MJ.ExploringthediversityofGardnerellavaginalisinthe genitourinarytractmicrobiotaofmonogamouscouples

throughsubtlenucleotidevariation.PLoSONE.2011;6:e26732. M10.

21.SwansonKS,DowdSE,SuchodolskiJS,etal.Phylogenetic andgene-centricmetagenomicsofthecanineintestinal microbiomerevealssimilaritieswithhumansandmice. ISMEJ.2011;5:639–649.

22.DeSantisTZ,HugenholtzP,LarsenN,etal.Greengenes,a chimera-checked16SrRNAgenedatabaseandworkbench compatiblewithARB.ApplEnvironMicrobiol.

2006;72:5069–5072.

23.HungateRE.Arolltubemethodforcultivationofstrict anaerobes.In:NorrisJR,RibbonsDW,eds.Methodsin Microbiology.vol.3B.NewYork,USA:AcademicPress; 1969:117–132.

24.ThabetOB,FardeauML,JoulianC,etal.Clostridiumtunisiense sp.nov.,anewproteolytic,sulfur-reducingbacterium isolatedfromanolivemillwastewatercontaminatedby phosphogypse.Anaerobe.2004;10:185–190.

25.HallTA.BioEdit:auser-friendlybiologicalsequence alignmenteditorandanalysisprogramforWindows 95/98/NT.NucleicAcidsSympSer.1999;41:95–98.

26.AltschulSF,GishW,MillerW,MyersEW,LipmanDJ.Basic localalignmentsearchtool.JMolBiol.1990;215:403–410.

27.ColeJR,WangQ,CardenasE,etal.Theribosomaldatabase project:improvedalignmentsandnewtoolsforrRNA analysis.NucleicAcidsRes.2009;37(Database

issue):D141–D145.

28.WinkerS,WoeseCR.AdefinitionofthedomainsArchaea, BacteriaandEucaryaintermsofsmallsubunitribosomal RNAcharacteristics.SystApplMicrobiol.1991;14:305–310.

29.JukesTH,CantorCR.Evolutionofproteinmolecules.In: MunroHN,ed.MammalianProteinMetabolism.NewYork,USA: AcademicPress;1969:21–132.

30.SaitouN,NeiM.Theneighbor-joiningmethod:anew methodforreconstructingphylogenetictrees.MolBiolEvol. 1987;4:406–425.

31.FelsensteinJ.Confidencelimitsonphylogenies:anapproach usingthebootstrap.Evolution.1985;39:783–791.

32.SimpsonEH.Measurementofdiversity.Nature.1949;163:688.

33.GiovannoniSJ,RappéM.Evolution,diversity,andmolecular ecologyofmarineprokaryotes.In:KirchmanDL,ed.Microbial EcologyoftheOceans.NewYork,NY:JohnWiley&Sons,Inc.; 2000:47–84.

34.ZwartG,CrumpBC,Kamst-VanAgterveldMP,HagenF,Han SK.Typicalfreshwaterbacteria:ananalysisofavailable16S rRNAgenesequencesfromplanktonoflakesandrivers. AquatMicrobEcol.2002;28:141–155.

35.CrocettiGR,HugenholtzP,BondPL,etal.Identificationof polyphosphate-accumulatingorganismsanddesignof16S rRNA-directedprobesfortheirdetectionandquantitation. ApplEnvironMicrobiol.2000;66:1175–1182.

36.HuberR,LangworthyTA.Thermotogamaritimasp.Nov. representsanewgenusofuniqueextremelythermophilic eubacteriagrowingupto90◦C.ArchMicrobiol.

1986;144:324–333.

37.NeefA,AmannR,SchlesnerH,SchleiferKH.Monitoringa widespreadbacterialgroup:insitudetectionof

planctomyceteswith16SrRNA-targetedprobes.Microbiology. 1998;144(Pt12):3257–3266.

38.ChouariR,LePaslierD,DaegelenP,GinestetP,Weissenbach J,SghirA.Molecularevidencefornovelplanctomycete diversityinamunicipalwastewatertreatmentplant.Appl EnvironMicrobiol.2003;69:7354–7363.

39.ElshahedMS,YoussefNH,LuoQ,etal.Phylogeneticand metabolicdiversityofPlanctomycetesfromanaerobic, sulfide-andsulfur-richZodletoneSpring,Oklahoma.ApplEnviron Microbiol.2007;73:4707–4716.

40.HugLA,CastelleCJ,WrightonKC,etal.Communitygenomic analysesconstrainthedistributionofmetabolictraitsacross theChloroflexiphylumandindicaterolesinsedimentcarbon cycling.Microbiome.2013;1:22.

41.TangY,ShigematsuT,MorimuraS,KidaK.Microbial communityanalysisofmesophilicanaerobicprotein degradationprocessusingbovineserumalbumin(BSA)-fed continuouscultivation.JBiosciBioeng.2005;99:150–164.

42.FangHHP,LiangDW,ZhangT,LiuY.Anaerobictreatmentof phenolinwastewaterunderthermophiliccondition.Water Res.2006;40:427–434.

43.ZumsteinE,MolettaR,GodonJJ.Examinationoftwoyearsof communitydynamicsinananaerobicbioreactorusing fluorescencepolymerasechainreaction(PCR)single-strand conformationpolymorphismanalysis.EnvironMicrobiol. 2000;2:69–78.

44.KeskesS,HmaiedF,GannounH,BouallaguiH,GodonJJ, HamdiM.Performanceofasubmergedmembrane bioreactorfortheaerobictreatmentofabattoirwastewater. BioresourTechnol.2012;103:28–34.

45.BegonM,HarperJL,TownsendCR.Ecology:Individuals, PopulationsandCommunities.2nded.Boston,MA:Blackwell ScientificPublications;1990:945.

46.WoeseCR.Bacterialevolution.MicrobiolRev.1987;51:221–271.

47.ZhangK.Clostridiumsp.fromyakrumeninChina. Unpublished.2006.

48.ZhangK,SongL,DongX.Proteiniclasticumruminisgen.nov., sp.nov.,astrictlyanaerobicproteolyticbacteriumisolated fromyakrumen.IntJSystEvolMicrobiol.2010;60(Pt 9):2221–2225.

49.SasakiY,TakikawaN,KojimaA,NorimatsuM,SuzukiS, TamuraY.PhylogeneticpositionsofClostridiumnovyiand Clostridiumhaemolyticumbasedon16SrDNAsequences.IntJ SystEvolMicrobiol.2001;51(Pt3):901–904.

50.BurrellPC.Theisolationofnovelanaerobiccellulolytic bacteriafromalandfillleachatebioreactor.Unpublished. 2004.

51.JohnsonJL,MooreWEC,MooreLVH.Bacteroidescaccaesp. nov.,Bacteroidesmerdaesp.nov.,andBacteroidesstercorissp. nov.isolatedfromhumanfeces.IntJSystBacteriol. 1986;36:499–501.

52.SongY,LiuC,LeeJ,BolanosM,VaisanenML,FinegoldSM. Bacteroidesgoldsteiniisp.nov.isolatedfromclinicalspecimens ofhumanintestinalorigin.JClinMicrobiol.2005;43:4522–4527.

53.SakamotoM,BennoY.ReclassificationofBacteroides distasonis,BacteroidesgoldsteiniiandBacteroidesmerdae asParabacteroidesdistasonisgen.nov.,comb.nov., Parabacteroidesgoldsteiniicomb.nov.andParabacteroides merdaecomb.nov.IntJSystEvolMicrobiol.2006;56(Pt 7):1599–1605.

54.SakamotoM,SuzukiN,MatsunagaN,etal.Parabacteroides gordoniisp.nov.,isolatedfromhumanbloodcultures.IntJ SystEvolMicrobiol.2009;59(Pt11):2843–2847.

55.JabariL,GannounH,CayolJL,etal.Characterizationof Defluviitaleasaccharophilagen.nov.,sp.nov.,athermophilic bacteriumisolatedfromanupflowanaerobicfiltertreating abattoirwastewaters,andproposalofDefluviitaleaceaefam. nov.IntJSystEvolMicrobiol.2012;62(Pt3):550–555.

56.LiT.Microbialfunctionalgroupsinathermophilicanaerobic solidwastedigestorrevealedbystableisotopeprobing. Unpublished.2007.

57.LomansBP,LeijdekkersP,WesselinkJJ,etal.HJ.Obligate sulfide-dependentdegradationofmethoxylatedaromatic compoundsandformationofmethanethiolanddimethyl sulfidebyafreshwatersedimentisolate,Parasporobacterium paucivoransgen.nov.,sp.nov.ApplEnvironMicrobiol. 2001;67:4017–4023.

58.JabariL,GannounH,CayolJL,etal.Macellibacteroides fermentansgen.nov.,sp.nov.,amemberofthefamily Porphyromonadaceaeisolatedfromanupflowanaerobicfilter treatingabattoirwastewaters.IntJSystEvolMicrobiol. 2012;62(Pt10):2522–2527.

59.BrodieEL,DesantisTZ,JoynerDC,etal.Applicationofa high-densityoligonucleotidemicroarrayapproachtostudy bacterialpopulationdynamicsduringuraniumreduction andreoxidation.ApplEnvironMicrobiol.2006;72:6288–6298.

60.LaParaTM,NakatsuCH,PanteaL,AllemanJE.Phylogenetic analysisofbacterialcommunitiesinmesophilicand thermophilicbioreactorstreatingpharmaceutical wastewater.ApplEnvironMicrobiol.2000;66:3951–3959.

61.PluggeCM,ZoetendalEG,StamsAJ.Caloramatorcoolhaasiisp. nov.,aglutamate-degrading,moderatelythermophilic anaerobe.IntJSystEvolMicrobiol.2000;50(Pt3):1155–1162.

62.ShiratoriH,OhiwaH,IkenoH,etal.Lutisporathermophilagen. nov.,sp.nov.,athermophilic,spore-formingbacterium isolatedfromathermophilicmethanogenicbioreactor digestingmunicipalsolidwastes.IntJSystEvolMicrobiol. 2008;58(Pt4):964–969.

63.GarciaJL,PatelBK,OllivierB.Taxonomic,phylogenetic,and ecologicaldiversityofmethanogenicArchaea.Anaerobe. 2000;6:205–226.

64.McInerneyMJ.Anaerobichydrolisandfermentationoffats andproteins.In:ZehnderAJ,ed.BiologyofAnaerobic Microorganisms.NewYork,USA:JohnWileyandSons,Inc.; 1988:373–415.

65.DolfingJ.Acetogenesis.In:ZehnderAJB,ed.Biologyof anaerobicmicroorganisms.NewYork,USA:JohnWileyand Sons,Inc.;1988:417–468.

66.EnsleyBD,SuflitaJM.Metabolismofenvironmental contaminantsbymixedandpureculturesofsulfate reducingbacteria.In:BartonLL,ed.SulfateReducingBacteria. vol.8.NewYork,USA:PeplumPress;1995:293–332.

67.KaksonenAH.Diversityandcommunityfattyacidprofiling ofsulfate-reducingfluidized-bedreactorstreatingacidic, metal-containingwastewater.GeomicrobiolJ.2004;21: 469–480.

68.HeidelbergJF,SeshadriR,HavemanSA,etal.Thegenome sequenceoftheanaerobic,sulfate-reducingbacterium DesulfovibriovulgarisHildenborough.NatBiotechnol. 2004;22:554–559.

69.Tardy-JacquenodC,MagotM,PatelBKC,MatheronR, CaumetteP.Desulfotomaculumhalophilumsp.nov.,a halophilicsulfate-reducingbacteriumisolatedfromoil productionfacilities.IntJSystBacteriol.1998;48(Pt2):333–338.

70.PikutaE,LysenkoA,SuzinaN,etal.Desulfotomaculum alkaliphilumsp.nov.,anewalkaliphilic,moderately thermophilic,sulfate-reducingbacterium.IntJSystEvol Microbiol.2000;50(Pt1):25–33.

71.JabariL,GannounH,CayolJL,etal.Desulfotomaculumpeckii sp.nov.,amoderatelythermophilicmemberofthegenus Desulfotomaculum,isolatedfromanupflowanaerobicfilter treatingabattoirwastewaters.IntJSystEvolMicrobiol. 2013;63(Pt6):2082–2087.

72.StackebrandtE,KramerI,SwiderskiJ,HippeH.Phylogenetic basisforataxonomicdissectionofthegenusClostridium. FEMSImmunolMedMicrobiol.1999;24:253–258.

73.HippeH.ReclassificationofDesulfobacteriummacestiiasa memberofthegenusDesulfomicrobium:Desulfomicrobium macestensecomb.nov.,nom.Corrig.Unpublished.2000.