HAL Id: tel-00654161

https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00654161

Submitted on 21 Dec 2011

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of

sci-entific research documents, whether they are

pub-lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents

scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Sur quelques structures d’information Intervenant en

jeux, dans les problèmes d’équipe ou de contrôle et en

filtrage

Jean Lévine

To cite this version:

Jean Lévine. Sur quelques structures d’information Intervenant en jeux, dans les problèmes d’équipe

ou de contrôle et en filtrage. Automatique / Robotique. Université Paris Dauphine - Paris IX, 1984.

�tel-00654161�

THESE

DE DOCTOR.l\T D'ETAT ES SCIENCES 11.l\THEHATIQUES

presentee

a

L'Universite Par is 9 - Dauphine UER de l'!athematiques de la Decisionpour obtenirLe grade de

DOCTEUR ES SCIENCES

par

Jean LEVINE

Sujet de la These:

Sur Quelques structures dIInformation Intervenant en Jeu:.::, d aris les Pz ob Leme a d'Equipe oude cont.r o Le et en Filtrage.

Directeur de Recherche Alain BENSOUSSAN

Soutenue Le 19 Novembre 1984

RENERCIEUEUTS

Quecettethese so i tLapreuve derna re c o n n a iss an c e env er e tous ceuxqui ,de pres audeloin, ont p ar t.aq eme e preoccu p ations, m'a i d a n t a assemb ler au fi l des an neea Les pie c e s de cet edifice res t.e, heLe e, t.rea imp a rfait.

Je t ien s a exprime r rnapr ofond e qr at.f t.ude tout part icu-Laer emen t.AA.BENS OUSSANquim'a eou v ent.t.emc Iqne saco nfi an ce et e'a prodigue le s conseils et encouragemen t s sa ns Les que La co trav ai l n'au r ai t 8an s dout e pasYU Le jour ; aP. BERNHARD qu i m'a rn rtte A laprup art,de sdomainesabo r deadanscememcfre et qui a er bien r eus et a me transrnettre son ent ho usias rne pour la reche rch e appliquee aeluidoia rnapresence auCAl de l'Ec o l e desHin e s;aM. FL I ESS, 3.M LASRY, P.L. LIONS ct; E. PARDOUX qu i ont souv ent ma nirest.e leur interet pour man trav a il, Le prou v a nt, par leu r s nomb reu x coneeire, et qui me font l' hon ne ur et l'amitie de pa r t.icipc r .\ ce jury.

J'a d res s eau s s i mese

mce

rea rerner cie me n ts A tau s Le a co-slgnataire s de s travau x t ct pr e sent. e s r J. THEPOT, G. PIGN I E, A.KASI f\:SKl,F GEROJoolELet P.WIUoIS, ain siqu'a t.o u e mea coLke q uea du CAl,G. COHEN, Y.LENOIR,L. PRALYet t.ousre eaut. rcaqui. part agen t quo t idie nnemen t Le durapp r enti s sage de la rech erche me t. hc d cLcqLqu e eou miee aux ox rqenceedes application s.

Qu' il me so it perrnis au s s r d'exp zimer rna reconnai s s a nce env e r s 3. LEVY. Direct. eurde l'Ecole des Hi nes, etLe souha i t qu e le s moye n s de ma intenir un equtLfbr eentr ethe o rie at appl i cat i ons iro n t etemetro ren t ,

Je reme r c re enf inJ.Altirnir a etA.Le Gal li c qutontpris charge Le trav ail de fr a pp e avec be a u co u p de soin etde bo nn e hume u r.

RESUME DE LA THESE D'ETAT DE

Jean LEVINE

Sur Quelques structures d' Information Intervenant en Jeux, dans les Pz ob Leme s d'Equipe ou de corrt.r o Le et en Filtrage.

Ce memoir e est cons acr e

a

I' etude de certains aspects de la prise de decision ou de La commande avec information incomplete sur l'environnement d e t.e r minis t;e oua Le at.oir e ,Dans l a te r e partie, on p r c s e nte des structures d'infor-mation classique d etc r-rnLniato s . comprenantla boucle ouverte, la structurede Stackelberg, la boucle fe r mc e et laboucle fe r me e sur Le futur On compare, suru n exemplede duopoledynamique issude la th e o rJe de la firme, les e q uiLi b r-e s en boucle o u v e rte et fer me e Puis on etu die lastr-u ctu r e feed forward et on montre, en g e n e r a Li, s a nt I.a methode des c a r-a cto r Lstt quo s pourles syste me s dte q u atLo n s d' Hamil ton-Jacobi-Bellman, une c o n ditionn e c e s s airedtexistence locale, s u g g or-ant qu'il existeu n e infinitedte quiLi b r-e adans cer-tains

Dans la 2eme partie, on etudieI' information non classique pour les pr ob Leme s d' e qu Lp e stochastiques dans Le cas de d e c Lde uz a multiples ayant des observations d Lffe r errt.e s et une memoir e limi-tee. On generalise la methode de programmation dynamique en prenant La loi des tra"jectoires jusqu'a l'instant present comme variable d' e t.a t., On obtient une equ at a ond 'Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman sous des hypotheses de regular It e , donnant une d efinition r igoureuse de la notion de "signalisation". Ces hypotheses de r equ Laz ite sont v e r if I e e s dans Le cas du contrOle des diffusions avec observations partielles.

La 3eme pa rtie est co r i sa c ree

a

l' etude d '117".8 cL a sse d<== syat.emes non Li n e aLre s admettam:. desfI Lt.re e de dLrnerisicnfLnie Les sy s t.erne s c ori sLd e r e s ,a

t.emp sdiscret au c o nr.i nu , s orrt, C':t:;,:aC1:~L1J~S par Le fait que lee bruits n'c.gissen1: pas sur La dynarm quc~ du ey st.erne ,mais a e uLernerrt,sur les observations. On donneLacondition n e c e e s air e et suffis ant.e dIex istence d' unf.i Lr.re de dirnericion !::inieainsi que sa realisation minimale, et on montre Le lien entre

dimension finie du filtre et Imme r ston dans un sye t.eraeLf.neair e . Un exemple concret permet d' e v aLue r les performances de la met.hcd e de filtrage, et, deLa comparer au filtre de Kalman e t.eridu ,

La 4eme partie, enfin, propose un aLqo r i.t.hrne rapide nour Le calcul des ccrrcnande s r e aLia ant; Le d e c oupLaoe cu Le rejet des perturbations d "uri s ys t.eme no n Li n e air e (comluandes pcuv ant, s e r vir

a

d ef Ln Lr une sous-optimalite r aLsormab Le pour certains p r ob Leme s de contr61e s t.o chas t.Lque ) Cet algorithme n e c e s sit.e d e r ivation formelle (et peut e t.r e p r oo r arnme dans un Lanq aq e cornme REDUCE ou MACSYMA) at utilise l'interpretation des nombr e s dits "carac-t.e r istiques" comme la longueur de chemins mini.rnauxdans 1e qr aph e du s yst.erne • Cette methode est appliquee au calcul des commande s qui d e c oup Le nt; la dynamique dIun bras de robot.DES l{!:l' IERES

Page

I NTRODUCTI ON

PARTIE I

Generalites sur les structures d' information. Etude de quelques structuresdIinformationen jeuxd Lffer enbLe Ls deterministes noncooperat.Lfe , application au duopole dynamique.

17

1 - Dynamic Duopoly Theory 21

2 - Open Loop and Closed Loop EC;llilibr ia in a Dynamical 41

Duopoly

3 - On the Solutions of Harn ilton - Jacobi Systems and 55

Applications to theDyriarn Lc Duopoly

corrt r oLe et dIequ i.pe PARTIE I I

Etude des conditions r1''''''~;,"""li;-''avec information non class ique pour les pr obLernes

stochastiques.

73

- Non ClassicalLnfo rm.rt Loriand Optimality in Conti- 77 nuous-Time Dynamic Te2mPro'Jle~~s

PARTIE II I

F iltrage non Lt n e air e de

de sys t.emes

a

t..emps discret et ccrrtinuurie c Las s e 187

1 - Exact Finite Dimensional Filt.ers For a Class of 191

Nonlinear Discrete-T Ime Systems

2 - The Finite Dimensional Filtering Problem for a 241

Class of Nonlinear Discrete-Time Systems.

3 - Une Classe de s ys t.cme s No n Li n e air e s

a

Temps Continu 247 Adme t.t.ant; des F LLt.r e s de Dimens ion F inie.PARTIr; IV

Methodes de graphe pour Le d e cou p Laq e et Le r ejet.de perturhations des sy s t.eme e non Li n e a ir c s

1 - A Fast Graph-Thcoric IUgorH.hm For the Feedback 265

Decoupling Problem of Nonlinear sys t.ems ,

2 - A Fast Algorithm Forsys t.emeDecoupling Usin Formal 279

Calculus.

ANNEXE 293

- Un Ape r cu Elementaire de la 'I'h e o r Le Moderne des 295 sys t.emee Non Li ne air es

INTRODUCTION

LES STRUCTURES DYNAMIQUES D' INfORt1ATION

Lorsqu'un d e cide ur- veutelaborer rationellemenT sa str-ate g i.c , par exemple dans .Le cadrede la gestion d'une firme, i l d oit bien e n r e n d utenir compte des informationsqu'il a en sa possession, mais aussi d'un certainnombre d'autres facteursdont l'oubli risquerai t de faire echouersesproj ets :

combieny a - t - i ld ' autres d e c Ld e u r s et que lIes sont les informations en leur possession ?

. Savent-ils la naturedes informations quep o s s e d s notre decideur, et celui-ci connait i l I a naturedes informations de ses c o e q u Lp Le r s ou/et de ses concurrents?

. Y a - t - i l desinformations dont on sait qu'elles existent mais quecertains d e cid e u r s uniquementpeuvent connaitresans en trahir Le contenu ?

que Le faitmeme de libeller cesquestions est

conn ude tous ?

Sichaque d e c i.d e ur- adopte une str ate gied o n n e e , comment r e s u Lt at sera-t-il evalue parchaque d e cid e ur- et cette evaluation est-elle connuede tous ?

. Le resultatd ' une telle str-ate g I s influence-t-il observationsdes d e cid e u r s et si oui comment?

On pourrai T prolonger cettel i s t e encore longtemps, mais butn 'estpas de tenterde d e c o u r a g er- Le d e c Ld e u r p ote n r Le L IIs ' agit simplement de sensibiliser .le lecteur nonpas auc o n c e pt vague et multiformequ'est l'informaTion, mais plus p r e cis e me nt ,

a l a structuredyna'J1iq'..le d'i:1formationgui intervient dans 10. prisede decision 0'..1 le guidage automatique.

Notons que dans lesquestionsprecedences o nt ete e mp l oveOo: termesassez proches : information e r observation.

CIest en fait 1Iensembledesobservations auxquelles les deci-deurs ont a c c e s a u n instant donne et 10.maniere dont

ensemble varie avec le temps quiservira de definition informelle l'expression "structure dynamiqued'information" Et comme precise plus haut, on p r ste r aplus p a rrt Lc u L'i e r-e me nt attentiona l ' influence quantitativede certaines structures d ' information surles decisions quien r e s u Lt e nt ; ce quin'interdit d'ailleurs, de t i r e rdes conclusions qualitatives.

Ainsi, les cadres th e o r Lq u e s que l'ons'est donne sont les Dynamiques,les Problemesd'Equipe, et 10.Th c o nie du Controle, d ete r-rniniste s 0'..1 stochastiques, et l'influencede l ' information sur les decisionsse traduit icipar 10. notion de bouclage (voir pour certainscas particuliers [1] et [2]).

Danstous cesp r-o b Le me s , l ' etat est donnepar 10.solution d 'uneequation d 'evolution LnfLu e n c e e parune 0'..1 plusieurs commandes, et cet etat estsoi t observe c o mp l cte me nt , soi t obseC've par 1ILnte r-me d i.air e de me c a n Ls me s qui r e n d c nt impossible 10. connaissance exacte de l ' etat, soi t encorepas observe du tout. Dansles deux premierscas, on peut avoiruneme mo Lr-e parfaite, se souvenir d 'unepartie seulement du passe desobservations, 0'..1 encore n' observerq uIune fo n c rio n .ir ata ntan e ede l ' e t a tet oublier tout ce qui precede 1 'observation

a

chaque instant. Mais dans tous les cas,10.structure dynamique d'informationpeut s'exprimerd'une ma nie r-e simple, comme 10.d o n n e ed'une famille de a-algebres .in d e x e e s par letemps (voir Ben¥s [3]), contenant a chaque instant l'ensemble de toutes les observations donton peut tenir c o mpteloide commande, et 10.10i de commande estdite admissible si elle estmesurablepar rapport a c et te famille de a-algebres.

Cetted ef initLor; contient naturellement les notions classiquesde boucle ouverte (pas d' information autre

que le temps) ou de bouclefe r-rae e (i-nformation comp:"ete ic stentanee s a n s memoireJ, e r aun s e n s aussi bie n dans

cieterml~is-;:esque

prob Ie rn e s

=n contrale au c a n s les pr obLe me s d'equipe, les o e rfc r mc n c c s realiseespar l ' u t i l i s a t i o n desc o r.m an d e s , s o nt evaluees

a.

d'une fonction c oiit qui estun e foncti-onnelle 'tr a ] e ctoir e s des c o mrnan d e s , e t que l'onc h e r c h ea

.nininie er-dans la .Iois, commande admissibles.Eri je u x , chaque joueur dispose d'une fonction c oiit suppose que les joueurscherchent

a

realiser un typedonne d'equi1ibre(equilibre de"ash par e x e mp Le )a

l'aide des lois de commande admissibles pourchaque joueur.Dans tousles cas,on s' attachera

a

d e v e Lo p p er-des techniques de calcula d a pte e s auxdiverses structures d'information,a

mettre en evidencel ' influence de cesstructures surlesc o n dir Lon s d'cptimaliTe et, lorsqu'on1epourra, sur leminimum ou l ' e q u i l i b r e obtenus.peuttrouver de nombreuxexemples pratiquespour lesquels formalismep r e s e nte convient parfaitement. Citons, sans les d etaiLl er-, les p r o b Le me s d' oligopo1e dynamiqueen economie, d' allocation des taches dans un ordinateur mulTiprocesseuroudans un a t e l i e r flexible, d'evaluationdes transitoireset des c a p a cite s tempsreel d'unr e s e a ude communication, et enfin guidage automatique engeneral avecobservat ionpartielle de l ' etat (1' u n

p r o b Le rne s lesplus frequents en Ln g e nie r-i e !)

Cependant,

a

part de rares exceptions ayant tr o o souvent un caract ere a c a d e miq u e , .Ie calcu1 effectifdes s t r a t e gie s optimales d e p a s s e les p c s s LbLcLt c e des ordinateurs a ctu e Ls , ce qui compromet gravement les p c s sib L'ite s d'app1ication en l ' e t a tactuel de la l:heorie. Notamment, en contrale stochastiqueavec observations p a rtLo Ll es classique (memoireparfaite), on est a me n ea

calculer loi de p r-o b a biL'i t c de l ' e t a t conditionnellement aux observations p a s s e e s (1e f i l t r e ) . v o i r [4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10], loi qui depend des commandes derna nie r e e xtr e me me nt corr.pLi q u e e , ~e caslineaireo u e c r ati qu e gaussien joueici role singullerpu Lsqu a le :"iltre s 'ycalcule

a

l ' aide d "u nr:ombre fi"i de p e r a rne t r o s queseule la mc y e n n e c o n d Lt Lo n n e Ll e depend des c o mrna n d e s Cpr Ln c Lp e de :~eparation de Honham [~1]). On peut done essayer de r r-o u v e r-classes de p r-o b Lc me s d o nt Le f i l t r e est de dimension finie, ce quisimplifie notablement laconduite ca1cu1s : c ettc idee, popu-La rIse e p ar- Brockett [12], a fait l'objet de tentativesencore tr e s limi Tees [13], [14], [15] avons c h e r c n e a la developperpour classede p r-o b Le me sa

temps discret o u continu. (Partie III.).Une seconde approchepermettant d "c s p c r e r des simplifications substantielles, consiste, a l'insTarde [15], a renoncer

a

l'optimalite,pour l ' u t i l i s a t i o n de lois de commande induisant une structurebeaucoup plus simpleet meme, eventuellement,p e r rr etta nt de se ramenera

un p r-o b Le me d ete r-min Ls t e . Ainsi, on proposera l'uti~isationdes techniques de d e c o up La g e et de r ejet de perturbations [17],[18],permettant en particulierde lineariser Le syste me parbouclage, et d1appliquer, a p r e s rej et desp e r t u r b atLo n s , sibesoin est, les techniquesdu Li n e air-e quadratique deterministe !

Avant de passer

a

unerevuede detail surlespoints que .i.'on vientd'aborder, p r e cis o n s quece travail estla reunion d'une s e r I e d' articlesp u b Li e s oua

publier, don t Iesoucis maj eur est de developperdes Techniques de calcul lorsquecelles-ci sont parcellaires (lerepartie), ou inexistantes (2emeet 3emeparties),deja connues mais trop lourdes (4eme partie).

J3ien entendu, les divers d e v e Lo p p e me nts proposesn "a p p c r t e n t de solutions miracles, et d' importants effortsrestent a faire, aussi bien th e o r-Lq u e s quepratiques, p a r-t Lc u Li e r-o mo n t dans la secondepartie, avant de pouvoirs!attaquer

a

des applications reelles dont la t a i l l e estg e n e r a Le me nt colossale ! Cependant, les deux d e r-nie r e s parties (Filtrage n o n Li n e air-e de dimension finie et d e c o up La g edes syste mo s n o n Li n e air e s ) n o u s semblent, du p o l nt de vue des applications, e xtr-em e me nt prometteuses comme .le s u g g e r-e nt .i.es o x e rnp Le s p r e s e n t e s (conduite de til'et g uic a g o rap ided'un b r a s de robot, exemples emanants de secte u r s industriels d o nt la demande d'innovationn' est plus a d e mo ntr-er- i».

Ce travail rassernble 10 articles organises en quatreparties

- Generalites sur les structuresd'information. etude de quelques structures d' information en jeux differentiels deterministes non cooperatifs. application au duopole dynamique.

1.1. Dynamic duopoly theory (en collaboration avec J. I'h e p otL, p ub Li e dans l ' Encyclopedia of Systems and Control. Pergamon Press. 1983.

1.2. Open-loop and closed-loop equilibria in a dynamicalduopoly (en collaboration avec J. Thepot), p u bLde dans "Optimal Control Theory and Economic Analysis. G. Feichtinger Ed., North-Holland. 1982.

1.3. On the solutions of Hamilton-Jacobi systems and applications the dynamic duopoly. A paraitr e , 1983.

II - Etude des conditions d'optimalite avec information non

Classique pour les problemes de controle et d' equipe stochastiques.

Non classical information and optimality in continuous-time dynamic team problems. A parai tre. 1984.

III - Fil trage nonlineaire de dimension finie pour une classe de systemes

a

tempsdiscret et continu.III Exact fini te dimensional filters for a class of nonlinear

discrete-time systems. (en collabora tion avec G Pignie) A paraitre. 1983

I I I I . b The finite dimensional filtering problem for a classof

nonlinear discrete-time systems Proc of the9th IFAC

World Congress Budapest. 1984 (en collaboration avec

G. Pignie).

111.2 Une classe de s y s t e rne s n o n Lt n e a Lr-e s

a

tempscontinu admettant des filtres de dimension finie. A paraitre. 1984.IV - Methodes de graphe pour Ie decouplage et Ie rejetde

perturba tions des systemes n o n Li.n e a Lr-e s .

IV.1. A fast graph theoretic algorithm for the feedbackdecoupling problem of nonlinear systems. (en collaboration avec A. Kasinskil. in Mathematical Theory of Networks and Systems. P.A. Fuhrmann. ed. Lecture Notes in Control and Information Sciences, N°58, pp. 550-562. (1983). Springer.

IV.2. A fast algorithm for systems decoupling using formal calculus (en collaboration avec F. Geromel et P. Willis). In Analysis and Optimization of Systems. A. Bensoussan, J.L. Lions e d , Lecture Notes in Control and Information Sciences, N°63, Part.2, p p , 378-390, (1983).Springer.

Un a p e r cu elementaire de la t h e o r i.e moderme des s y st s ms s n o n Ld n e a Lr-e e , p ub l d e dans la RAIRO - Automatique. (Dec. 83).

Partie 1 :

Dans la premiere partie, on donne u n ep r-e s e nta tion informelle de differentes structures d' information dans Le cadre de la th e o r Le des j eux dynamiques non c o o p e r-a tifs

a

2 joueurs (duopole d yn a miq uei . Les structures d' informa tion sont c La s s e e s en deux series : "information complete" (qui est d'ailleurs u n c h o i.x malheureux p uis q uto n n'yconnait pas n e c e s s a Lr-eme n t. tout! mais qui veut simplement dire qu' u n e structure probabiliste n ' est pas n e c e s s a Lr-e ) et "informa tique incomplete".L' informa tion complete regroupe la boucle ouverte, La boucle fe r-me e , les structuces du type Sl:ackelberg tdisyrnctr Lq u a ) et en fin la "boucle fe r me e sur le f'utu r?•Les techniques hamil toniennes de cal c u L des strategies optimales sont presentees Aucune structure

donne Le meme r e s u I ta t en general.

Cette affirmation est eta y e e par les deux papiers c omp Le me n t.air-e s 1.2 et1.3 de ce chapi tre o u l ' on mon tre (1.2) que la notion de boucle fe r-me e nIimplique pas, ma Lg r e la presence dIinforma tion complete Ln st a nta ne e , une concurrence plus e x a c e r-b e e : au contraire, dans le cas de firmes se partageant Le ma r c h e par le c c ntr-o Le des prix, pour un ma r c h e de biens substi tuables avec une demande

a

elasticite constante, la boucle fermee induit une certaine cooperation parce que chaque firmesait que les 2 ont intereta

saturer les contraintes,ce qui limite les choix str ate g Lq u e s au lieu de c r-e er-des menaces s up p Le me nta Lr-e s , et produit en definitive un consensuspour avoir des prix plus eleves qu'en boucle ouverte. Le second

papier (1.3) p r e s e nte une structure d'information originale que l'on rencontre naturellement dans le cas general de la resolution des condi tions d' optimali te : l ' e q u Ll Lb r-e de Nash des Hamil toniens donne les strategies optimales comme des fonctions de l'etat, mais aussi des variables adjointes (done contenant des informations sur le futur). Or, on montre par le calcul d u s y st e me c a r-a cte rt s t.Lq ue que ces strategies donnent lieu en general

a

une infinite d'equilibres possibles en tout point regulier g e n e r-Lq ue . On termine en donnant exemple Ld n e a Lr e quadra tique o u aucun des e q ua.Li.b r-e s en boucle ouverte, f'e r-mee ou fe r-me e sur le futur ne coincide. On peut certainement en c o n c Lu r e que l'equilibre de Nash n'est pas une dIequilibre suffisamment precise pour etre vraiment pertinente . . .Dans la seconde s e r Lede structures d'information incomplete, p r-e s e nte les structures de bouclefe r-me e sur les observations de boucle fe r-me e sur la loi de probabili te de 1Ietat .Nous reviendrons sur ces structures dans la seconde partie.

Cette partie est c ntie r-e me nt c o n s a c r-e e

a

l ' information non classique,a

savoir lorsque les oi-a Lg e b r-c s d 'observation ne sont pas croissantes enfonction d utemps On peut donner 2 exemples simples de structures d ' information o u cela a lieu :lorsque Le con trol eur (decideur dans un p r o b Le me de contra Le )oublie une partie du passe des observations, ou, lorsqu'il y a plusieurs joueurs, si chaque joueur a desinformations dif'f'e r-e nt e s sur l ' e t a t du s y ste me et n'a pas a c c e s a u x informations des autres Onvoit quecette d e r nie r e structure est g e n e r a Le enth e o riedes jeux ou dans lesp r-o b Le me s d' e q u.i p e , On montre que l ' on peut utiliser la methode de programmation dynamiquea

condition de "grossir"l'espace d ' e t a t : au lieu de l ' e t a tdu s y ste me de depart, i l faut utiliser sa loide probabili tenon condi tionnelle comme nouvelle variable d'etat. Dans ce cas, la programmation dynamique donne la ou les strategies optimales enfonction des observations et de la loi, ce qui obligea

c o n s Ld e r-e r une structure d ' information plus g e n e r a Le o uLe bouclage des commandes sur la loi est permis, et que l ' on a a p p e Le e "bouclef'e r me ev• On montre alors que l' optimum en boucle r e r me e est egal au precedent, puis on derive les condi tions d' opti-malite .Cette etude est me n e e dans deux c a s : lorsque les bruits temps discret ou dans Le casdes diffusions

On montre dansces deux situations que la fonctionvaleur est et continue par rapport

a

la loides trajectoires, et done sur-differentiable, et, moyennant unecondi tion de r e g u La r L te sur Le sur-differentiel, on peut obtenir une equation du type Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman c a r-a ct e r Ls a nt La fonction valeur et la ou les strat e g i.e s optimales. L' Hamil tonien a s s o ciea

cette equa tion comporte alors un terme supplementaire par rapporta

celui du c o n t r o Lea

information complete, terme que l'on peut interpreter comme la variation du c o ut c o r-r e s p o n d a n ta

unev a r LatLo n d'information; on donne ainsi une definition precise de la notion de "signalling", introdui te heuristiquement dans[19J

et[zo] ,

disantq u 'aI'optimum

la commande devait r-e a Lt s e r le meilleur compromisentre minimiser le c o ut et coder desLnfo r-matLo n s dont la connaissance pourrait a rue Lt o r-e r les decisionsfu t.u r e sDans Lecas particulier du c o ntr o r e desdiffusions avec observations partielles etinformation c La s eiq u e , on mo ntr-e en plusque .L'c q u atio n d' Hamil ton-Jacobi-Bellman p e ut.etre obtenue sans hypothese de r e gu La r-Lt e sur La fonction valeur, donnant ainsi unecondition n e c e s s s a Lr e et suffisante dIoptimalite , g e n e r-a Li s ant les condi tions n e c e s s a Lr e s obtenues par A. Bensoussant

[5J

Partie III :

Comme p r-e c e d e mme nt a n n o n c c , c 'est la p e n u riede techniques de cal c u L efficaces en contrale stochastique, me me

a

information classique (.3.1 'exception du cas lineaire-quadratique gaussien) qui montre l'importance soit des techniques de filtrage approche, soitde fil trage exact mais dimension finie.

C' est Le p r o b Le me d u fil trage exact de dimensionfinie quiest a o o r de ici pour uneclasse de syste me s n o n Li n c a I r-e s

a

temps discretcontinu , ne comportant pas de bruits de dynamique.

Du point de vue des applications, unetelle mo d e Ld s atLo n peut justifier au moins dansles deuxcas suivants :

- la d u r-e e de vie ou d'observation du processusest tr e s - lesbruits de dynamique n'agissent que sur les composantes "Ientes" du processus. Onpeut ainsi filtrer sur un court intervalle de temps la dynamique rapidenon b r-ui te e (situation p r-e c e d e ntel , puis r-e a ctu a Li s e r la loi en fonction de la derivedu processus lent

recommencer.

Lesdeux premiers papierssont c o n s a c r-e s au temps disc ret , le premier exposant la th e o r Le et le secondcomparant d i.f'f'e r e nt e s methodes de filtrage dans le cadre d'une application, etLe tr oiais e me est c o n s a c r e autemps continu Less

ys

te me sa

temps discret etu oie s icisont plus gene raux queceuxa

temps continu puisque, pour les premiers, L' Lnte n s Lt e des bruitsd'observationpeut etre c o r r e Le ea

l ' e t a t (bruits c o Lo r e s ) .Dans Le premier papierI on c o mma n c e par p r o u v er-u n e formule recursive donnant La loi c o ncitic nn e Ije non n o r-ma Li s e e , puis montre qu "u n e orientation n a t.ur-eLl e consiste

a

g e n e r-a Li s er-a

la dimension infinie les techniques de realisation des s y ste me s nonlineairesa

temps discret.On montre, dans Le cas des bruits gaussiens, que l'on peut construire explici tement une base canonique du fil tre qui donne lieu

a

u n e condi tion necessaire et suffisante d' existence de fil tre de dimension finie .Cette condi tion est p a rtLc u Ld e r e me n t. simple et accessible au calcul, et permet de d e c r-Lr-e explicitement la realisation minimale du filtre dont la dimension est e ga I.ea

la dimension de l ' espace e n g e n d r e par la base canonique. Bien entendu, on veri fie que cette realisation minimale est bien localement faiblement observable et localement faiblement accessible, au sens de La th e o r Le des s y ste me s n o n Li n e a Lr-e s . De plus, on montre q utu n s y st e me n o n Ld n e a Lr-e admettant un filtre de dimension finie peut etretr-a n s f'o r-me en un s y ste me Ld n e a Lr-esi et seulement si l'intensite des bruits n'est pas c o r-r e Le ea

l'etat. Enfin, on tente d'evaluer Le nombre des s y st e me s admettant un filtre de dimension minimale do nn e e r , et pour une equation d'observation d o n ne e . On montre que,sous certaines hypotheses de r e g u La r Ite sur la base canonique, on peut effectivement construire au moins autant de syste me s satisfaisant aux condi tions ci-dessus que d ' elements d' un sous-grouped u groupe Li n e a Lr e de dimension r , En plus d'exemples a c a d emiq u e s , on p r e s e nte une application r e e Ll.e

a

un p r o b Le me de conduite de tir, donnant des r e s u Lt at s probants, alors qu'aucune methode Li.n e air-e ou a p p r o c h e e ne donne de bons r e s u Lta ts. Ce point est p a rttc u Lt e r-eme nt d e v e Lo p p e dans Le second papier o u 1 'on montre, toujours pour Le p r o b Lem e de conduite de tir, que Le filtre de Kalman ete n d u diverge presque systematiquement, que Le filtre de Kalman sur un s y ste me L'i n e a i.r-e obtenu en d e r-Lv a n t. deux fois Le s y ste me de depart est c o mp Letem e nt inefficace puis que l'etat n'y est plus observable, alorsque Le filtre n o n Li.ne a Lr-e obtenu par les techniques p r e c e de nte s donneI pour une erreur ini tiale de l ' ordre de 40 %, u n e e stLrae e en moins de 15 observations ( 2 secondes r e e Ll.e a ) dont l'erreur est Ln f'e r-Le u r ea

5 %. Notons enfin que pour des temps de cal c u L aussi courts l'utilisation du filtre n on L'i n e a Lr-e general (de dimension infinie) etait rigoureusement impossible.Dans Le tr-o Lsie me papier, onmo n t r s qU2 la p Lu pa rr. des r e s u I ta ts precedents se g e n e r a Lt s e nt au temp s c o n t Lnu AinsiI a o r e s avoir c a l c u Le explicite me nt la solution de I' e q ua tion c e Zakai pour Le cas de la dynamique non b r uite e , on fait apparaitre comme p r e c e d emme nt la base canonique du fil tre donnant ainsila condi tion n e c e s s air-e et suffisante d'existence dtu n filtre de dimension finie, ainsi que la realisation minimale du filtre. La condition obtenue est equiva-lente

a

la dimension finie de l'algebre de Lie a s s o cie ea

l'equation, de Zakai, g e n c r a Li s a nt ainsi des r e s u Lt at s heuristiques[21]

obtenus p r e c e d e mme nt dans Le cas o u I' a Lg e b r c de Lie est nilpotente. On donne enfin un exemple d' observation p oLynSmia Le de d e g r-e quelconque d' un s y s t.e me Li n e a Lr-e non b r uite ou Le filtre est toujours de dimension finie, alors que lorsque la dynamique est b r-u Ite e et l'observation cubique, i l n ' y a pas de fil tre de dimension finie (voir [14J).Partie IV :

La motivation de cette d e r n Le r-e partie, qui n'est pas d o n n e e dansles papiers p r e s e nt e s , comportant en soi un interet plus general, peut etre vue comme Le o e ve Lo p pe me nt de methodespermettant de transformer un p r o b Leme stochastique n o n Ld n e a Lr-e en un p r o b Le me eventuellement decouple et Ld n e a Lr-e , mais surtout d e t.e r'mLn Let e (rejet des perturbations). La classe naturelle des lois de commande assurant une telle p r-o p riete est done la classe dans laquelle on peut chercher la "sous-optimali te".

Le premier papier IV. 1, a p r-e s avoir r a p p e Le les conditions necessaires et suffisantes de rejet de perturbation et de d e c o up La g e , prouve que Le calcul des lois de commande assurant Ie rejet de perturbations et Ie d e c o up La g e peut etre t r e s largement simplifie

a

l'aide de l'interpretation, en terme de graphe, des nombres c a r-a cte r-LstLq u e s , Ces nombres s' Lnte r p r-et e n t. comme Le nombre minimal dtLnte g r att o n s q u ' il fauta

une commande pour etre "visible" dans une sortie d o n n e e . On donne l'algorithme de calcul, utilisant des methodesde calcul forme1 (Reduce ou Macsyma).Le second papier IV.2 donne u n resume du papier IV 1 et montre comment est organise Le programme de calcul formel. L' interet de la methode de graphe est c hi ff'r-e sur l'exemple du c e c ou p La g ede la dynamique d' un bras de robot. Cet exemple montre Le gain que 1ton retire des methodes de c a Lc u I formel, sans lesquelles Le d e c o u p La g e de tels s y ste mes n e c e s si.teraient des efforts e xtr eme nt lourds.

Annexes :

On donne u n expose e Le me nta Lr e des r e s u Lt.ats les plus modernes th e o r Le des s y ste me sn o n Li n e a Lr-e s qui pourra servir

a

e c Lair-c i.r-certain nombre de definitions et p r o p r-Lete s ut Ll d s e e sdans les deux derniers chapit r-e s .Conclusion :

Ce travail comportant essentiellement des methodes de calcul, i l est clair q u ' u n travail de comparaison et d' approfondissement sur chaque structure dIinformation est n e c e s s a Lr-e . Ce travail semble cependant tr e s difficile dans Le cas de l'information non classique ou de gros efforts th e o r Lq u e sres tent

a

faire, surtout concernant les methodes n ume r d qu e s .D' autre part, la generalisation des methodes d e v e Lo p p e e s en fil trage, au cas comportant des brui ts de dynamique semble etre questiontr e s importante aussi bien t.h e o r-Lq ue me nt que pour les applica tions.

Finalement, i l serait Lnt e r e s s a n t de savoir s ' i l est possible de trouver des algori thmes performants pour Le d e c o u p La g e et Ie rejet de perturbations par retour de sortie puisqu'ici les methodes p r o p o s e e s n e c e s si te nt la connaissance exacte de l'etat.

References de l'Introduction

[1] BERNEARD, G. COHEN, J-P QUADRAT: Le feedback en th e o r I c de la commande. Quelquesremarques. A paraItre

[2] HO, I. BLAU, T. BASAR : A t a l e offour.irfo r-matio n str-u ctu r e s A paraitre.

[3] BENES: Existence of optimalstrategies basedon specified information, SIAMJ. Cont. Vol.8, 2 p.179-188 (1970).

[4] ANDERSON, A. FRIEDMAN: Nulti-dimensionalquality control. Parts I and II. TAMS, Vo1.246, p.31-94 (1978).

[5] BENSOUSSAN : Maximum principle and dynamic programming approaches of the optimal control of partially observed diffusions. Stochastics. 9,3, (1983), p169-222.

[6] J.M BISMUT : Sur un p r-o b Le me de controle stochastique avec observation partiel1e. Z.f.W, 49, p.63-95 (1979).

[7] DAVIS :Nonlinearsemigroups inthe controlof partially observed stochastic systems. LectureNotes in Nath. (1979).

[8] FLEMING: Nonlinear semigroup forcontrolled partially observed diffusions. To appear.

[9] FLEMING, E. PARDOUX : Existenceof optimal p a r t LaLl.vobserved diffusions. SIAM J. Co nt Vol p.251-288 (1982)

[10] R.E. MORTENSEN: Stochasticoptimal control withnoisy v atio n s . Int. J. Cant. 4, p.455-4 6 5 (1966).

[11] W.M WONHAM : On separation theoremof s t o c h a s ric SIA~l J. Cant Vol.6, N°2, (1968)

[12] ::z 3RGCKETT : Remarkson ::'inite dimension a ; estimation Asterisque75, 76 (1980)

[13] Exact finite dirne n sio n a L f i l t e r s for certain cif::'usions with non::-inea.r d r i f t . Stcchastics 5, p.65-92 (1981).

[14] t1 HAZE\HNKEL,

s

ir ,

elARCUS, H.J. SUSS~t,AN Non existence of exact finite dime n s i.o n e Lf i l t e r s?reprin t. Uriive r si

te

Erasmus. Ams-::erdam.[15] M. CHALEYAT-MAUR:::L, D. \1ICHE~ : Un th e o r e me de n o nve x Ls r e r c s de f i l t r e de dimensionfinie. CRAS, t 296 (19£,3). Serie 1. 933-936.

[16] QUADRAT : These Paris

[17] ISI1)ORI, A. KREHER, C. GORI-GIORGI, S. \10NACO :Nonlinear decoupling viafeedback.

p.331- 345 (1981).

Trans. AC. 2 6 , 2 ,

[18] D. CLAUDE: Decoupling of nonlinear systems. Syst. Cont. Letters. 1 , 4(1982).

[19J H.S. WITSENHAUSEN : A counterexample in stochastic optimum

control. SIAM J. Cont. 6,1, (1968), p . 131-147.

[20J I.C. HO, M. KASTNER, E. WONG: Teams, market signalling, and

information theory. IEEE-AC, 68,6, (1980), p. 644-654.

[21J Z.S. ROTH, K.A. LOPARO : Optimal filter realizationfor a class

of nonlinear systems with finite dimensional estimation algebra. Syst. Cont. Letters, 4,1, (1984), p.23-26

PARTIE I

Gt!meralites sur les structures dIinformation.

Etude de quelques structures dIinformation en jeux differentiels

deterministes non cooper at.Lr s ,

RESUME DE LA Jere PARTIE

Generalites sur les structures d' information. Duopole dynamique

Cette partie sert

a

introduire les diverses structuresd' Information qui ant ete e t.udLeea jusqu'

a

present dansLecadre des jeux dynamiques Le premier article, pub Li e dans I' Encyclopedia of Systems and Control, en collaboration avecJ. Thepot, sert enquel-que sorte de f il d irecteur pour les 2 premieres parties: on y

p r e s errt e , sans les d emorrt.z e r , les pr incipaux r eauLt.at,s sur les

con-ditions d'equilibre pour chaque structure d'information, et les

r e s uLt.at.s originaux sont d eve Loppe e et demont.r es dans les autres articles des parties I et I I.

t.es structures d' information presentees sont classees en deux grnupes: l' information de nature deterministe et l ' information d e nat.ur e probabiliste.

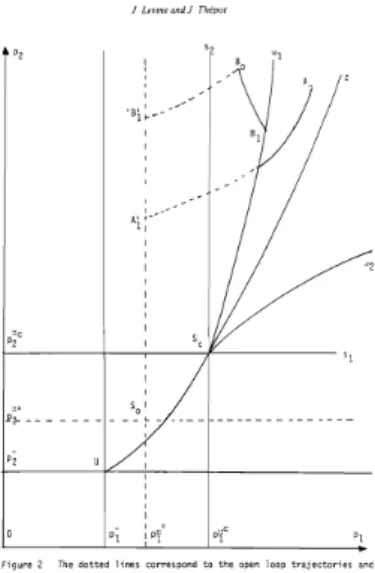

£1) n:ln~ I.e premier groupe, on trouve la boucle ouverte (la seule information pour les 2 joueurs estLetemps et le point de depart du jeu), La boucle fermee (les joueurs ont une information com-plete sur l ' etat du j eu mais purement instantanee), les struc-tures d Lsymet.r iques du type Stackelberg ou l ' un des 2 joueurs est Le meneur et I' autre le suiveur. Le meneur joue en boucle ouverte a l.o r s que le suiveur joue en boucle fermee et connaissant la s t.r ateg i e du meneur; et enf in, la boucle f erme e sur le futur (information complete instantanee des 2 joueurs et enplus, ob-servation exacte de leur revenu marginal).

Deux contr ibutions or ig inales y sont annoncees, et deve-Loppee s dans les deux articles qui suivent. 11 s'agit d'une part de la comparaison entre equilibres en boucle ouverte et en boucle fe r mee , dans le cas d' un duopole au 2 f irmes se partagent le mar cb e par le contr61e des pr ix et deI'investissement, les biens p r o d uit.s par les 2 f irmes etant substituables, et la demande

at-ant s uppo s e e

a

elasticite constante. On montre que, contrai-rementa

ce que l'on attend, la boucle fermee induit une certaine cooperation entre les f irmes car chaque joueur sait que chacun a inter~ta.

saturer les contraintes sur les investissements, cequi limite leurs choix strategiques et produit, en definitive,

des pr ix plus e Lev e s qu' en boucle ouverte en reg ime permament. 11 s' ag it d' autre part du calcul des equilibres en boucle f e r mee sur Le futur. On montre d' abord que c' est cette structure d' informat ion qut apparalt naturellement lorsque l' on cherche un equilibre de Nash des Hamiltoniens, pUisqu'alors on obtient les s t.r at.eqie s optimales comme des fonctions du temps, de l'etat, et

lies variables adjointes (revenus marginaux des 2 joueurs), et

lorsque les strategies optimales ne saturent pas les

contrain-tesr on ne peut e Lirn Lne r les var iables adj ointes. On montre alors, en generalisant

a.

ce cas la t.heo r ie des car act.ar istiques de Cauchy de I' equation d' Hamilton-Jacobi, qu' il existe en tout point generiqlle une infinite d'equilibres possibles. Enfin, ondonne un exemple elementaire OUaucun des equilibres (boucle

ouverte, fe r mee et fermee sur le futur) ne coincide.

b) Dans Le d eux Leme groupe, on pr es ent,e des structures

d'infor-mation incomplete: boucle fermee sur les observations

instan-t.ane es ou , d'une part, les joueurs observant l'etat par des

pz oc ede s differents, ils ne peuvent comparer leurs informations, etr d' autr e part, les observations etant instantanees et sans memoir e , ils ne peuvent utiliser ce qu' ils auraient pu apprendre dans Le passe. ce type d' information non classique ne veri fie pas les conditions "habituelles" sur les o-algebres d' observation que l ' on suppose en contrOle avec observation partielle. On

pre-sente alors une equation de programmation dynamique qui sera

largement developpee dans la partie I I, consacree exclusivement

a.

l ' etude de l'information non class ique.DYNAtlIC IJUQPOL.y'TrrEORY

L.EVINE;t J. THEPOTJtJt

Since the prominent contribution of von Neumann and

Morgen-stern (1944)0 o Ld g o o e Ly theory is widelyrecognized as part of

Game Theory. Static f~rmulationsof the c Lf.g c p oLy game have t:Jeen

developed to explain howthe competitive interdeoendencies

deter-mine the price. quantity or advising decisions of the firms.

How-ever. itis clear that Timeplays a determinant partin the defif1

i t ion of the strategies of the competitors. Differential Games

techniques have therefore been used to extend thestatic

tradit-ional modelsto dynamicsituations. By emphasizing hereduopoly

situations. we are gcingto outline the main issues arising in

this Th e sr-y and to present illustrative and recent models.

I - General Statement and Informational Structuresof a

Dynamic Dilopoly

L.et us consider two firms (firm 1 and firm 2) competing

on the same market over a horizon [D. T]. At timet • the state n.

of firm i is representedby a vector Xi (t) of 1R~ (ex: or8ductien capacity, inventory levels. balance-sheet accounts.

etc . . . )0 ana its decision by a vector functionof its

ot:Jserv-ations (tobe defined later) withvalues uiLt ) in [RPi The

result ui(t) of firmi ' s decision at time t knowing its

observ-ations is called a control (ex: price. quantity to be soldby unit of time0 etc •.. )0 and asequence of decisions over the

horizon is called a strategy. At any time. each firm

to given constraints :

according

tP

j( toX(tJ,u1(tJ,u2( t ) ) ...0 , j • 1 . . . .,m [1] where xLt ) • (x1(tJ,x 2(t)]'€ iBn [prime denoting transpose],

denotes the state of theduopoly. If firm imust satisfy "':he

set of constraints ~i. {~. " •.d. } independently of i t s

~0 Ji

::Jpponent'sdecision, we say that this set::J-i' constraints is

under firm i ' s responsibility.

The dynamics of theduopoly are described by the

follow-ing differential system : XCt] • fCt.x Ct), uiCt J. u

2CtJ] (2)

in which the initial statexCO)• ~ is given.

During the interval [ t , t+dt], firm i ' s profit

by gi[t,x,u

1, U2)dt, so that the net present v.s Lu e J i horizon (with a discount rateeli) can be written as :

J

i( Ui, u2) •

f:

giCt,xCt),U1CtJ.1J2Ct))e-elitdt + Mi[xCTJJ. (3) i · 1 . 2 . where Mi describes ahe evaluationof firm i at time T. aefore to discuss the various structures of information

that can be metin these game problems, we suppose thatan

information struc.tureSis given, and that UiCS) is firm i ' s

set ofstrategies adapted toS, and satisfying the constraints

un d e r i ' s res p0n sib i l i t y. i • 1. 2. Th us, we assurne tnat the

two competitors try to realize anon-cooperative Nash

eqUilibr-Lurni namely. ifSisa completeinformationstructure (see

below]. theywant tofind a pair of strategies (u~. U~) in U

1(S) xU2CS) such t h a t :

J1[u~, u~) .;;;J1(u1,u~) IfU1E Ui(S) J2CU~.U~).;;;J2Cu~.uZ] lfu ZEUZCSJ

If~ is incomplete informationstructure, (4)must be

(4)

adaptedin replacing Ji by ECJi) the mathematicalexpectation of J

Finally, let uspresenta brie-f survey of the informational

structures thathave been studied or, at least, pointed out, in

the literature until now: they are classified into completeand

incomplete information structures.

1. Complete information.

In all thisparagraph, both firms are supposed

least a perfect knowledge of theset of data

{{tPj},f,J1,J 2,;,t,T}. (5)

For all thestructures introduced below, simple counterexamples

prove that they yield differentsolutions tothe Nash game.

1.1. Open-loopstructure : Both firms haveonly the

know-ledgeof (5). This structureis called "static" since there is

change of information during the game.The strategiesof U i(5) are thus measurable functions of t a n d ; ,and, when<;isfixed,

reduce tocontrols. Thisclass ofgames isby far the most

studied and the reader willfind a complete bibliography in

(Feichtinger, Jorgensen 1983).

1.2. Feedback structure: Bothfirms observe exactly the

state xat any time to Ui(5) is thus made of measurable functions

u

i(t,x). A careful definition ofthe solution of (1.) mu~!: be provided in order toallow strategiesthat are discontinuous with respect to x ,

As in (Basar ,Olsder1982); we distinguish between "Feedback" and

"Closed-Loop" structures, where the initialcondition; is also

r e mamb e r e d . Thus s tra tegies take the form ui( t , x , ; ) . When, further more, the competitors perfectlyremember the pastof the state,

we saythat we are in a "Full memorystructure".Whether these

I. ] . Sta ckelberg 'th e lea de r , say firm I, pl a ys ope n-lo op and gives it s co n tr ol at eve ry time to the followe r

which, inadditio n, per fe c t ly ob se rv es thestat e. 'thusU1(S) is

mad eof controls u\(t);wherea sU

2{S) is ::la d eof mea s urabl e fu ncti on, of the form u

2( t,Jl, U1(t» . Detai ls c:a llbe fou nd in t

e

asar 1977).1. 4.Fe ed f orwa rd st ru c:t u re :Each fir mtake s de c i si ons of

form ui( t ,x, ..,q)wherep (r,up.q) is the op timalmarg ina l

for fir:ll \ (r e sp 2) of thega :ne st artin gat

t

c,x) over the horizo nr

t,T].Th is in fo rm ati onstruct ur e is natura lly adapted to Dyn amicProg r am mi ng metho d s (Levine 19 53), As a re su l t , th est r u ctu res 1.3. lind \.4 . e e Le etd e in thezer o-sumsitu ation.

2. Incompl e te Infor matio n.

Thi s is thecasewhe r e lea s t one firm does notob se rve

I

perfe c tlythe statebe ca us e of dist u rb a nce s alld/or of theno n

iaj e ctivityof th e observa tion fu n ct i on. Pre cis ely,suppose th at th e obse rvat ions equa tions ar e gi ve n by :

Yi(t) • hi(]t (t),Vi(t) , i • 1,2 (6)

·

..her eVI and\1

2are exogeneousdLseureances,

Conceptu a lly,no th ingwo u ldcha ng e i f , inpl a ce of (6) , the

observa t ion. werede s cr ibedby a stochasticdLfferentLaLsystem. Fo l l owing (Ha rs any L 1968 ), the fit':lls must agreeonall a prior i

proba b i li t ymeasur e on the ini t i al statet andon the dist u r ba nc e s

Le t PU;,v

l,v2) be this apriori pro b abi l ityeeasure ,ThenJ1 an d

J2mustbereplac e d by the ir llIath em at i cal ex p e ctation with r-• •peet P, na mely

Ile shal l as sume tha t th e cons tr a in t s (J) areof the form ~i(t ,yi,u

1,u2) , i • 1,2.

2.J. Output Feedback Structure: Each finn perfectly knows

theset of data :

{{Ijl~},f,h],h2,'J],J2,P,t,T},

and observesYi ateverytime t (andpossibly all orpart of the past Y

i ) . Decisions t a k e the form u i (t , Yi) 0r u i (t, { Yi (s)I s ~ t } ) .

Z.2. Closed-Loop Structure : Inaddi tion to the preceding

the decisions take into account the actualprobability

measure P

t, image of P by (Z), which plays therole of the state

of the game with incomplete information.Thus firm i ' s decision

is of the form ui(t'Yi'Pt ) , For details see (Levine J981).Z.1.

and Z.Z. arereferred to as non-classical information

(Witsenhausen 1968) sincefirms 1 andZ have different ob s e r v atLo n

and the associated sigma-fields included one in another.

- Characterizations of Nash Equilibria.

We shall review theexistence results and the

characterizat-ions of the solutionsfor the precedinginformation structures.

We shall usethe same numbering as in paragraph I.

1.J. Open-Loop structure: Existence results ofan open-loop

Nashsolutioncan be proved for linear-quadraticgames (Starr,

Ho 1969). For the characterization of open-loop solutions, i t

can be proved thata two-sided minimum principle holds (Starr,

Ho 1969):

Theorem I :Let f ,gl ,gz ,MI,HZ be

c

Zfunctions and Ijl

~

depend only CUI,uZ),'Iti , j . Then anecessarycondition for

(u~ ,u~)

to bean open-loop Nash solution is that there exist two continuousfunctions Pl andPz satisfying:

.

*

*

x

=

f(t,x,uI,uZ) x(O) = ~ax.

* * * * with H] =PI.f(t,x,u

I,uZ) + g] (t,x,u] ,uZ)

..;

PI.f(t,x,u1'u~)

+g](t,x,u1'u~)

"Iu1 svt , <jl](u],U;)';;;; 0and HZ

=

PZ·f(t,x,u~

,u;) +gZ(t,x,U~

,u;).,; P Z • f(t,x, u: ,uZ) +g2 (t ,x, u: ' uz)

1.2. Feedback s'tructure :Existence results over a small

horizon can be derived for linear-quadratic games (Lukes 1971),

(Bensoussan ]974). Also characterizationscan be obtained under

regularityassumptions on theoptimalvalue functions, by means

of the Dynamic Programming method, and under theassumption that

the "local" Nash equi 1 i b rium of the Hami 1 tonians a t every po i n t

can be obtainedas functions of (t,x). Namely (Case ]969)

Theorem Z : f ,gl,gz,M] ,MZare chosen as in theorem 1. Let

d~f

Ji(t,x,u:

,u~)

, i = ],Z, where (u;,u~)

supposed torealize aFeedback Nash equilibrium over thehorizon

[t,TI, from the i n i t i a l point x . Suppose furthermore that VI and

V

z

ar: piecewise continuously differentiable. Then VI' V 2' - . and Uz

must solve the following system ofHamilton-Jacobiequations everyregularpoint :

av I av] * *

at

-a.]v l+] Min *(ax

.f(t,x,u] ,uZ)+gl (t,x,uI,uZ»=O <jl (t,x ,u

I,uZ)';;;;O

(8)

av

z

av Z **

at

-a.ivz+ 2 Min*(ax

.f(t,x,u-I,uZ)+gZ(t,x,uI,uZ» .. O • <P ( tx ul,u2) ..,;o

Corollary (Case 1969) : Underthe* same as:umption and if (u~,u;) o b t a i ned by ( 8) are0f theform u] (t , x ) , u Z ( t • x ) , the n

p] =

~l

andPz=

~Zsolve,

at every regular point, the adjointaMi

P i ( T ) - a i ( x ( T » , i = I , Z (9)

*

Remark: in (9) appear the derivativesof u

i ' i .. 1, Z, with

respect to x, so that its solution is generally different from

theopen-loop adj oints.

Let us also point out that the optimization problem of (8)

determines u: and

u~

as functions of (t,x,PI ,PZ). Thus a methodto obtainu~as functions of (t,x) consists in making the change

of variables

(10)

Thus Pi must satisfy the system : *

*

.:.:.i

+~{

.s"

=

af* agi j ( df*+~i)~ ~

at ax - Pi" a i

j - a ij - CliP i - Pi' ~ "aU 'aP'dXj i ..1,2; j , k " I , . . .,n. ( I I )

where f* denotes f evaluated at

u~

(t,x'P1(t,x) ,PZ(t,x», and the*

same forgi'

For linear f andquadratic gi' and if we look for ul U

z

linear feedback functions of x , (11) becomes the wellknown.

system of two coupled Riccatiequations. Nevertheless, thereis

no proofof the fact that, in thelinear quadratic case, the

linear solution of (11) is unique, and the author conjectures

the contrary.

Onthe other hand, one can find verification theorems in

(Stalford, Leitmenn 1973), (Mehlmann 198Z), but an open problem

remains the derivation of necessary conditions on singular s u rfa c a .

1.3. Stackelberg structure : Since the leaderplays

the characterization of the Stackelberg equilibrium can be

obtained by crossing the two preceding methods. It can be seen

in(Basar 1977) that there existinfinitely many equilibria even

inthe simplest linear-quadratic case withstrictly convex cost

functions. This result illustrates the sensitivity of the Nash

equilibrium to the information structures.

1.4. Feedforward : It was seen in ].Z. that one generally

obtains the optimal strategies in (8) in the form:

*

*

u'j (t ,x ,PI 'PZ) , u

z

(t ,x,p] ,PZ) .Thus, since the information structure allows the competitors to

use their optimal strategies as such, without introducing the a

priori change of variables (JO), i t remains to find the adjoint

system for PI'PZ in order to compute the optimaltrajectories.

.

*

ir*

Thus, l.f we note f* (t;x'P1,PZ)"'f(t,-x,u] (t,x,p] ,PZ),uZ(t,x,Pl,PZ)

and the same forgl ,gz' and if we set

Hi'" P i.f* (t , x , PI' P z) + g: (t,"X ,PI' P 2 ) , i '" I,Z ,

'" TT.

1. '" 1,Z,

the following theorem (Le-v i.n e 1983) holds t r u e :

Theorem 3 : inthe feedforwardstructure theadjoint equations

are given, in additionto

x '"

f* (t''X'P 1,PZ), byi '"J,2; j,k '" 1, . . .,n,

i - J,Z; 1 '" ] , •••,n, aM. withterminal conditions: Pi (T) '" a:xl.('X(T».

a~k

with Zn equations,and suitable transversality conditions. This suggests that non-uniqueness of Nash equilibria is a generic prope:ty.*

~ :The non-uniqueness of (IZ) disappears when u

1 and U

z

independent of PI'PZ' in which case the informations on the

future contained in PI ,PZare wot:thless, and the adjoint system

reduces to (9). However, i t can be proved that thesolutions

obtained by (1Z)

loop solutions.

generally different from the openand

closed-Z. Incomplete Information. Feedback structure: We shall

just sketch the dynamic programming methods, forexample when the

observation equations are given by (6), with vi a piecewise

constant process on prescribed intervals [ tj, t

j+ I[ forming a partition of [O,T] • We note vi the projection of vi onthe interval

[ tj, tj+ 1[ andwe suppose that vi is independent of x and of v~, k

r

j, and we note oCv) the probability measure of (vJ'\,)Z). Let us denote :

e -(1i tv i (t, Pi) -

JJcJ~gi

(s'x:

(t ,x),u:

,u~)

e -(1i s ds+Mi(X; (t ,x» )dPt(x)dp(v) , i-1,Z (13)

*

*

where ul,u

Zaresupposed to be a Nashpair in theFeedback

structure (precisely, forevery t'Yi(t) and P

t, they are given by

*

*

u1(t'Yl(t),P t), uZ(t'YZ(t),Pt

» ,

and whereXs(t,x) is thesolution of (2) at time s startingfrom (t,x) and generated byu~ ,u~. Finally, let us recall that the Lie derivative of P t in thedirection of ul,uz' : ~~elimit when i t e x i s t s : LUI ,u

z

(P t) ,.~~~ ~(Xe:l

z(t,pt) - Pt) (J4)U1,u

z

where Xe: (t,P

t) is the image of Pt by the flow of tr aje cto r roj , solutions of :

10

ul,u

z

with Xt (t ,x)

Thefollowing results holdtrue (Levine 1981) :

Proposition: Vi has the integral representation

Vi(t,P

t) = fwi(t,x;t,Pt)dPt(X) , i

=

1,Z,*

with wi(t,x;s,Ps) '"' wi(t,x;t,Xt(s,Ps)) '" (t,s,Ps)'

~

: If(u~ ,u~)

is a Nash point and if w1'w Z are C1functions of all their arguments, then wehave :

ff(~I_CllW

)dPtdP(\»)+f{Minfl;;l.f(t,x,UJ,u~)+gl

(t,x,u],u~)+

u J+<~I,L

*(P )-L**(Pt»ld(Pt~P)(x,\)IYJ)}dQ~(Y])

= 0 ap ul,u Z t l lJ,uzawZ

.awZ

*

*

ff(~ -ClZwZ)dPtdp(\»)+f{MJ.nflai .f(t,x,ul,uZ)+gZ(t,x,uJ,uZ)+ Uz

aw

Zz

+<3'P ,Lu~,uz(Pt)-Lu:,u~(Pt»]d(PtllOp)(x,\)IYz)}dQt(YZ)= 0 wi th the boundary conditions :(J5)

wi(T,x;t,P) '"' Mi(x) , '" x,t,P; i

=

I,Z, whereQ~

=yi(t,Pt) , i'"' I,Z, and where the bracll:ets<,> denote the duality between C1functions and first order distributions.

~ :Very l i t t l e is known about the solutions of (15) which

constitutesa non-linear integra-differential system. I t is

interesting to interpret thecoupled minimization problem of (15)

as a trade-off between cost and information, since the Lie

deri va t i veterm des cribe s the variation ofprobabiLi, ty induced by a variation of control.

To conclude thissurvey of theoretic methods for non-zero

sum differential games, let us just mention theanalysis in

(Dockner, Feichtinger, Jorgensen 1983) of classes of games

11

the optimal controls can bedirectly obtained by a system of

differential equations :

Ui = 'I'i (u1,u Z 'c ) , i - 1, Z .

This situation occurs for example when

~i

dU and~i

do not i '3Xicontain those adjointcomponents

p~

corresponding to xj , j i .III - AnIllustrative Example: GrowthStrategies in a

Price-Setting Duopoly. (Levine .. Thepot 1982)

Let us consider aprice setting duopoly aver an infinite

horizon when the outputs of the competitors are substituable. At

time t , firm i charges theprice Pi(t); its demand xiby unit of

time is supposedto depend on both prices:

(16)

Without a great loss of generality,we will assume henceforth

that the demand functions are time independentand constant

e1as tic i tie s fun c t ions 'in the form x i "Bi P i -Ei pj ni , wher e Bi i s

aconstant depending on the variable units, E

i the elasticity with respect to i ' sown price, n

i the crosselasticity with respect competitor j1S price, satisfying the following inequali ties :

E i > l , n i ; ; ' O ; D=E1EZ-n1nZ>O,

which merely' express classical assumptionson

I. Defini tion of the differential game.

(17)

demand functions

Each firmis supposedto maximise its net present value; then

the problem can be stated as thefollowing differential

Y

i=

Ii - U\Yi' Yi(0)=

; io .;;;

Ii-cCliVi) (Pi - ci)x i ;(18)

(19) (20) (21)

12

where Yi is the output capacity offirmi , Ii therate of inves t>

ment in volume of capacity, c

i the production cost by unit of

put, wi the rate of depreciation of capacity, vi the priceof

unit volume of investment, <;i the levelof capacity at time O.

Re Ls . (20) express that the investment is irreversible and that

firm i is not allowed atany time to lose money; all the

para-meters vi' ci ' wi are supposed to be constantthroughout the

horizon. Hencei t is adifferential game with two state variables

YI'Y2 and two control variables Pi,Ii at the disposal ofeach

compe t i tor.

2.Open loop strategies inthe duopoly

By'using the classical results (see sect. 11.1.1.), we defin .

the current value dualized Hamiltonian Hi offirm i as follows

Hi = (Pi-ci)xi-viIi+qi(Ii-wiYi)+'Pi(Ij-wjYj)+a.i(Yi-xi)· (22)

with qi''Pi' (].i being respectively the costate variables

associated tocapacity Yi' Yj are the Kuhn and Tucker multiplier

associated tocons traint (21). The class ical necessary condi t ions

y i e l d : qi=(wi+di)qi-a. i ' ,p("'(wj+di)'P i ;

(x'+(P.-c.)~·)(I+.!. )(q.-v.)+_a..~i

= 0~ i, 3Pi vi ~ ~ ~3Pi

(23)

(24)

lim q. (t)exp(-d.t) lim 'P. (t)exp(-d.t) 0 ; (25)

t ...oo ~ ~ t... ~ ~

q i <v i " Ii =0 , q i = v i " I i >0 un d e term in ed, qi > vi .. Ii = ; i (Pi - ci)x i ;

(26)

sake of simplicity we do not consider situations where

excesscapacity may occur. Accordingly (26) determine the three

po licies I ike ly to becho sen by each firm along the eq ui I ib ri um

path: [policy I (qi<vi):Ii = 0; policy 2 (permanent policy, qi = vi); policy 3 (qi

>

vi):I i = }; (Pi - ci)xil . A combination13

(k-s) of policies where firmi andfirm j use respectively p o Iic '

k and s iscalled a duopolYregime.

It is easy to show that regime (2-2) is thefinal regimeof the

duopoly to be held from a time t* (t*

<

+00); this regimecoin-cides with the long term classical static equilibrium of the

duopoly with constant prices P:-E:i(ci+(wi+di)vi)/(E:i-l)

To emphasizegrowth strategies of the firm, we suppose that the

initial production capacities ';i arelower than, the long term

* * *

pro d u c t ion 1 eve 1 s xi =x i (p i ' P j ); a s a r e s u 1 t the firm s are both incitated to investand to grow from the ·beginning. Three

types of equilibrium paths can be found according to the values

of theini tial capaci ties .;1 and .; 2 :

For initial capacitiesof same ma g n Lt u d e-, theequilibrium

path is in theform (3-3) ...(2-3) .... (2-2) : at the beginning,

the competitorsuse their maximum investment policies 3while

decreasing the prices and increasing the production until time

t

i when the price reaches the value Pi'

*

Then, firm i adoptsthe permanent policy 2 with its price being" kept constant; firm

jIS pro d u c t ion i s s t i l l inc rea sin g but firm i ' s i s dec rea sin g .

At time t:price Pj becomes equal to pJ and the duopoly adopts

itspermanent regime with production and prices being

to infinity.

For a high initial capacity ';i anda low initial capacity

';j the equilibrium path is either in the form (3-3) ....(J-3) ....

(1-2) ...(2-2) or (3-3)....(1-3) ....(2-3) .... (2-2).Initially, the

firms use their maximum investment policies as previously. Howeve

at a time t

i, firm i stops its investmentalthough price Pi has

not yet reached the value Pi' As aresult, firm i goes througha

14

I t turns ou t tha t thegrowth of the firms is no t c rea ted

through monotonicallyincreasing productions forboth competitor

Moreo-ver, in some cases, one of thefirms has to stop Lnve s tmen t

during a transitory period, as the decrease of the competitor's

price causes too much ofa decline in demand"

3" Feedback strategies

In the closed Loop formulation, theprices and the rates of

investmentare to be sought in thefeedback form

Pi= Pi(yi,yj,t), I i " Ii(yi,yj,t) (Z8)

The feedbacks are determined by the Nash equilibrium of the

HamiLt o nd au s HI and HZ atany point intime t and forany

production capacities Y1 and YZ" As a result, therates of

investment Ii are given by (26), as in the open loop case, and

the capacities constraints (21) are saturated: Zi(Pi,Pj)=Y

i ' fr om which we deduce the feedback laws of theprices

_ <-e/D) (-nJD)

Pi - Yi Yj , and consequentlythose of the investments

The characteristic equations (9) actually take theform

I/J

i

=

-;'iy.-(q,_v.)~i+«lll.+d.)_;':'j)1jJ.

Yj 1 1 1 Y j J 1 Yj 1 + (Z5)"(Z9)

(30)

Clearly, the feedback strategies are sequencesof the three

policies defined above in theopen loop case. However,

differences have to bepointed out :

a) The feedback final regime (2-2) holds withconstant

--prices Pi

=

(Ci+<llli+di)Vi)/~I-ej/D) which arehigher than15

and contrarily to what is intuitively expected, feedback

stra-tegies imply more cooperative behaviourthan the open loop

strategies do.

b) Inthegrowing phase of the duopoly, regime (2-3) does

not hold in feedback with firm i keeping its price constant. In

this regime, theprices evolve according to anon linear differen

tial equations system(see Levine,Thepot 1982) which indicates

that both prices are decreasing. It turns then out that the

feedbackstrategies express a tendency towards some mimetism and

synchronization of the competitor'sdecisions.

IV - Generalized Competition Dynamic Models

Price (or quantity) manipulation is basicallyconsidered by

the managers as a two-edged sword which jeopardizes the

profit-ability of the firm rather than really affects therival's

position.Accordingly, thefirms are more and moreinvolved in

using other competitive weapons. Some dynamic duopoly models th e r e

fore have emphasized more accurate types ofcompetition on

advertising, quality of the products or R&D projects for

instance. Let us outline some typical andrecent contributions

inthi s field.

1.An advertising model (Deal1979)

Deal ·has developed extension of the classical monopolistic

sales response model of (Vidale, Wolfe 1957) :

Let x_(t) and a

i(t) the sales and the advertisingexpenditures per unit of time at date t of firm i . The evolution of the sales

are given by the following differentialequations :

(31

16

where

c

i = the sales decay parameter, 6i .. the sales response parameter and M ,. the total potentialmarket size (6i ,

c

i >0)

Eqn. (31) indicates that advertising expendi tures increase the

sales; however, such anincrease is more efficient when the

marketis saturated (namely when xl +x2 is close to M). As a

result, advertisingexpendituresof a firm have adirect effect

on its own sales andan indirectone on the competitor's as they

contribute to saturate thetotal market.

Dealdefines the o bjective function J i of firm i as a

weighted sum of the marketshareat time T and the sum of the

profits earned over the horizon.

J

i

=

wiXi( T ) ! [ X1( T ) +x2(T)] +f~[Pixi(t)

-a~(t)]dt.

(33)with Pibeing thenet revenue coefficient andwi the weighting

factor for the performance index. The problem is thenstated as a

differential game which is numericallysolved in Open Loop. The

obtained results for a widerange of values of the parametersgive

interestinginsights on therelative importance over the horizon

of the direct andindirect effects ofadvertising.

2.A marketing mix model (Thepot 1983)

This model is related to the price setting model presented

above in Section 3. Thedemand of firmi is assumed tobe in the

form:

xi(t) =Xi[Pi(t),Pj(t),Ai(t),Aj(t)] exp(yit) . (34)

where Ai (t) denotes the goodwill offirm i ,defined by the

differential equation Ai .. ai-r i Ai with a

irepresenting advertising expenditures per unit of time, r

i the depreciation of the goodwilland Yi the growth rate of the demand. Then the

17

In this model each firm has three control variables at its

disposal : the price Pi' theinvestment Ii and the advertising

expendi tures a i•

By emphasizing the Open Loopequilibrium and thecase where

the demand functions are constantelasticities functions. i t is

shown how Competition and Growth interact inthe investmentand

marketing strategies of the firms. It turns out that the

cross-elasticities of the demand with respect to the goodwill play an

important r o l e : they determine whether Competition holds through

pricing oradvertising decisions. This isdue to thefact that

pricing andadvertising decisions quite differently affect the

p r o f i t s : thefirst oneshave an instantaneouseffect while the

impact of the second

goodwill variations.

are displayed over time th r ou g h

Twosituations may occur: either the competitors behave in

a closeway to the monopoly case bycohabitingin the industry

while increasing their sales andboth benefiting of the growth.

orone of them is self eliminatedof the market. In somecase.

this elimination process leads this firm to manipulate its price

in order toavoid excess capacity.

3. A model of R&Dcompetition (Reinganum 1982)

J.F. Reinganum addresses theproblem of resource allocation

Research and Development in a competitive conte-xt by d ev e Lo pin

a dynamic duopoly (in fact oligopoly) model which 'in c o-r p o r ate s

the main aspects of this type of competitionover a non already

18

relevant to the innovation by expending resources on research

activity or knowledgeacquisition. The knowledge acquisition

process is assumed to be deterministic whereas the dateof

successful completion of theproject is a random variable. Then

theproblem can be stated as thedifferential game

Ji

=

f~[PLAl1i+PF~~j-ci(J1i)][exp

- (Zl+ zZ)]dt;Zi =Pi ' zi (0).. 0 ; O';;;;}li '" B,

where 11i (t) is firm i ' s rate ofknowledge acquisition, c i(11i) the discounted cost of additional knowledgeacquired attime t , B is

an upper bound of knowledgeacquisition; P

L is the present value

offirm i ' s reward i f i t is the f i r s t to succeed inthe completio

of the project, P

F if i t is the second (PF ,,;;; PL).Let ti be the timeat whichfirm i succeeds; i t is supposedthat

Prob{t

i.,; t} = I - ex~- zi (t)] and that theconditional probab-i l probab-i t y that firmi will succeedin thenext instant, given that i t

hosnot already done so, is Probiti£(t,t+dt)/ti>t}=A)li(t),O. >0)

Consequently, J

i is theexpected netpresent value of the

gain offirm i according to the fact that imitation is costless

immediate.

Due to the specific features of the exponential distribution,

i t turns outthat Open Loop andClosed Loop strategies coincide.

Analyticalsolutions are obtainedfor interiorsolutions

{O-e].Ii<B} •

Differentialgames techniques arean appropriate conceptual

framework to analyse the competitive strategies of firms ina

dynamic context, although avery limited number of models can be

completely analyticallysolved. However, they providea unified

language which makes comparisons and economicinterpretations