Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 123 Assessing Empathy: A Slumdog Questionnaire

Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski

Abstract (E): Applying recent theories of embodied cognition to Danny Boyle’s 2008 film Slumdog Millionaire, this essay contrasts Vittorio Gallese’s notion of the “shared manifold” of human experience to earlier models of identification drawn from Freudian psychology and Alvin Goldman’s simulationist theory of mind, and also proposes a fourth notion of empathy: “getting under the skin.” Focusing on Slumdog’s “blue boy” scene, which evoked strikingly different reactions from viewers around the world, this essay argues that viewer identification and empathy, while possibly universal phenomena, are simultaneously subject to cultural and historical constraints. Creating emotional bonds between viewers and filmic protagonists thus remains a complicated challenge for filmmakers aiming to reach a global audience.

Abstract (F): Cet article applique les théories récentes de cognition corporelle au film Slumdog Millionaire (Danny Boyle, 2008). Il oppose la notion du “partage multiple” de l’expérience humaine (“shared manifold”) de Vittorio Gallese à des modèles plus anciens basés sur le concept freudien d’identification mais aussi à la théorie simulationniste de l’esprit d’Alvin Goldman, tout en proposant une quatrième forme d’empathie qui consiste à se « glisser sous la peau » de quelqu’un d’autre. Analysant une scène qui a suscité des réactions très diverses parmi les spectateurs du monde entier, l’article démontre que tant l’identification que l’empathie, qui sont sans doute des phénomènes universellement partagés, subissent aussi des contraintes culturelles et historiques. La production de liens émotionnels entre spectateurs et personnages reste donc un défi très complexe pour tout réalisateur désireux de toucher un public global.

Keywords: empathy, identification, embodied cognition, intersubjectivity, cognitive slippage

Article

Under the Skin

In his Introduction to the shooting script for Slumdog Millionaire, director Danny Boyle describes his initial reaction to the manuscript that had found its way to his desk: “When I was first sent the screenplay for Slumdog Millionaire back in August 2006, I thought, ‘Oh, no, I don’t want to make a film about a quiz show!’” But realizing that Simon Beaufoy, screenwriter of The Full Monty, had penned this new script, Boyle decided to take a look. After reading just ten pages, Boyle committed to making the film. In that same introduction, Boyle expresses his admiration for Beaufoy’s adaption of Vikas Swarup’s bestselling novel Q & A:

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 124 This is screenwriting as architecture. Simon knows where he is taking you, and the delight is in discovering how he gets you there. Every scene has a beginning, a middle, and an end: a trigger, a purpose, and a destination. And the story has incredible empathy for its characters, an ability to get under the skin of life in one of the most intense and extreme cities on earth. It is never distanced or judgmental. Slumdog is inclusive, generous, and immediate.1

In addition to the skillful crafting of the narrative and strategic scene-pacing, Boyle strongly empathized with the characters of the screenplay, a set of connections enhanced by its powerful mode of storytelling. Boyle believed that he could bring the script to life, allowing viewers to “get under the skin” of life in Mumbai—from his perspective, “one of the most intense and extreme cities on earth.”

Boyle sought to translate this epidermal experience to the medium of film, creating, in the humorous phrasing of one critic, “a game-show Bollywoody picaresque featuring a slum kid’s rise from poverty to superstardom in his quest for love.”2 Despite initial difficulties with distribution,3Slumdog would go on to become a global hit, winning eight Oscar awards in 2009, including the Best Director and coveted Best Picture Awards, together with numerous other awards and nominations from around the world.4

Yet the film’s overwhelming success in the U.S. and Britain was not matched by a similar reception in India, where Slumdog provoked not only divided critical reactions, but also harsh condemnations and protests. While some Indian critics praised the film for its empathic presentations of its central characters and of slum life in Mumbai,5others voiced more negative reactions to the film. Many of those negative responses stemmed not only from viewers’ non-identifications with the protagonist and his epic quest, but also with the supposed views, values and goals of the film itself. In particular, the epithet “Slumdog,” used by a host of adversarial characters in the film to denigrate the hero Jamal Malik, was construed by some as an affront not only to India’s downtrodden and impoverished, but also to the nation as a whole.6And, while the “rags-to-raja” fantasy enamored many moviegoers, particularly in the U.S. and Britain, it alienated other segments of its audience with its sensational “poverty porn,” rampant violence, and controversial depictions of Mumbai’s Dharavi slum.7Moreover, the portrayal of Jamal as a Muslim (a detail not found in the original novel8) and most of his adversaries as Hindus also aroused rancor among some Hindus, who perceived this decision as unsympathetic and/or abusive to their ethnic and religious large group.9

In this essay, I shall analyze the phenomenon of empathy, as highlighted by Danny Boyle as one of the principal strengths of Simon Beaufoy’s characterization in the screenplay, and also expressed by viewers around the world as central to their experience of the film. Here I conceive of empathy as a form of “getting under the skin” of other people, or rather, of their getting under our skins. How one might share and understand the experiences of another being, whether real or fictional, is, of course, a key point of debate among those who study the human mind. Drawing on recent interdisciplinary explorations of embodied cognition and empathy taking place within

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 125 and between the fields of social and cognitive neuroscience, philosophy, film and narrative studies, and several other fields, I shall explore several possible meanings of “getting under the skin”—i.e., our potential modes of relating to fictional characters through real-time bodily experiences, both pleasurable and painful, that are conveyed through a “shared manifold” of experience. By comparing and combining various models of identification and empathy proposed by Sigmund Freud, Alvin Goldman, Vittorio Gallese, Susanne Keen and others, I hope to contribute to the interdisciplinary discussions and debates surrounding human cognitive processes and intersubjectivity.

A Question of Empathy

For the purposes of this study, I shall adopt literary theorist Suzanne Keen’s definition of empathy as “a vicarious, spontaneous sharing of affect . . . [that] can be provoked by witnessing another’s emotional state, by hearing about another’s condition, or even by reading. It need not be a conscious response . . . ."10Keen distinguishes empathy--feeling with a person (or character)--from the closely related affect of sympathy--feeling for another. Keen further distinguishes empathy from personal distress, “an aversive response also characterized by apprehension of another’s emotion,” but different from empathy “in that it focuses on the self and leads not to sympathy but to avoidance."11 In a narrative context, empathy may result from one’s identification with a character, or perhaps vice versa12; in most accounts, these phenomena are closely related to each other.

Question #1: In the opening sequence of the 2008 film Slumdog Millionaire, with which character do you empathize?

A: The jowly, middle-aged man (Fig. 1) who blows cigarette smoke in the face of B: The much younger man who sits across from him (Fig. 2)

C: Both men D: Neither man

In the first two minutes of the film, the camera alternates between tightly framed close-ups of both men, shot in hazy, golden half-light. Though no words are spoken, we hear the sounds of the older man, later identified as Srinivas (played by noted Indian actor, director and screenwriter Saurabh Shukla) sucking on his cigarette and puffing out smoke in brief, directional bursts. The younger man, soon identified as Jamal Malik (played by British actor Dev Patel in his feature-film debut), blinks as his interrogator blows the smoke into his face. As the camera angle switches back and forth, viewers must not only attempt to understand the apparent conflict, but must also decide with whom to identify. They may identify with one or

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 126 both characters, or they may consciously or unconsciously refrain from deciding until more information is forthcoming.

Fig. 1: Srinivas (Saurabh Shukla) attempts to smoke out his youthful prisoner.

Fig. 2: Jamal Malik (Dev Patel) faces interrogation from Constable Srinivas.

These preliminary questions of empathy and identification may be disrupted, complicated, or further solidified by the hard slap in the face delivered to the young man at the end of this sequence. As the screen fades to black, the first question of the film appears in a computer graphic, while a game-show clock ticks loudly in anticipation of the audience’s ‘final answer’:

Jamal Malik is one question away from winning twenty million rupees. How did he do it?

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 127

A: He cheated.

B: He’s lucky.

C: He’s a genius.

D: It is written.

While initially raising the possibility that Jamal has contributed to the aggression being directed toward him through some form of dishonesty (thus potentially undermining audience identification with the young man now identified as the protagonist), director Danny Boyle, co-director Loveleen Tandan, and screenwriter Simon Beaufoy offer three other answers that work to consolidate the viewers’ interest in, empathy for, and/or identification with Jamal at the outset of their film. As in Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? (Kaun Banega Kroropati, in its Hindi version), the television quiz show on which the screenplay and the original novel Q & A are based, viewers of Slumdog are thus invited to provide their answers to the film’s central question, both provisionally, at this early point in the story; at the conclusion of the film; and at many points in between.

Answer D, “It is written,” adds to the possibility that either luck or his prodigious intellectual gifts are advancing Jamal to a potential fortune. This answer also suggests the further prospect that the hidden hand of fate or providence guides not only Jamal’s life, but possibly that of the viewer, as well. In this way, the film’s playful game-show format also invites the fantasy of a global shared belief system that enables a universal identification with the protagonist and storyline, and that gratifies all tastes and wishes at once.

How We Identify: The Shared Manifold

While a global belief system remains elusive, there may, in fact, be universal patterns or structures in storytelling, as Patrick Colm Hogan has argued.13 Hogan further contends that people tend to respond in similar ways to certain story elements, situations, and characters, even across broad cultural or historical divides. Hogan attributes these patterns of shared response to certain shared features of human cognition that, for example, enable us to empathize or to identify with characters in stories, as we do in real life. He suggests that empathy may have evolved in humans for particular reasons of survival. Empathic anger, for example, is a typical response to physical threats to children.14 Such empathy, he might well argue, is likely to be mobilized in viewers watching the horrifying situations faced by children and young people in Slumdog Millionaire.

In this next section, I shall further explore the possible cognitive mechanisms of empathy, as well as the relation of empathy to new models of intersubjectivity. While I can only touch upon the extensive theorizations of these topics, I invite the reader to consider the following question:

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 128 Question #2: When you identify with a character in a story, you do so because

A: You imagine what it is like to walk in that character’s shoes B: The character is a vehicle for your fantasies

C: The character is a second you D: The character gets under your skin

While the differences between each possible answer may not be immediately apparent, I consider this question fundamental to our understanding of virtually any narrative, be it film, stage performance, novel, or some other form of representation.

The audience’s identification with a protagonist is never a given. Nevertheless, a skillful writer, director, or actor draws on a set of techniques to enhance identification, or sometimes to complicate it. In his landmark essay “Der Dichter und Phantasieren” (“Creative Writers and Daydreaming,” 1908), Freud argued that narcissistic impulses underlie the productions of creative writers, as well as readers or viewers of their productions. Creative writers design characters who serve to gratify the hidden or not-so-hidden wishes of both the authors and their audiences. In this respect, writers are barely different from daydreamers or children, in that each of these three groups creates a fantasy world invested with emotional significance. These representations, whether rehearsed in the mind or committed to page or stage, express certain wishes of their creators. A child may wish to be grown up, and may explore that wish through imaginative role-playing, as does the adult day-dreamer. A creative writer continues the play of childhood in the form of his or her artistic productions. The protagonist of the story becomes a proxy for the unexpressed desires and fantasies of the author, as well as the audience. Freud explains:

One feature above all cannot fail to strike us about the creations of these story-writers: each of them has a hero who is the centre of interest, for whom the writer tries to win our sympathy by every possible means and whom he seems to place under the protection of a special Providence. If, at the end of one chapter of my story, I leave the hero unconscious and bleeding from severe wounds, I am sure to find him at the beginning of the next being carefully nursed and on the way to recovery; and if the first volume closes with the ship he is in going down in a storm at sea, I am certain, at the opening of the second volume, to read of his miraculous rescue—a rescue without which the story could not proceed. The feeling of security with which I follow the hero through his perilous adventures is the same as the feeling with which a hero in real life throws himself into the water to save a drowning man or exposes himself to the enemy’s fire in order to storm a battery. It is the true heroic feeling, which one of our best writers has expressed in an inimitable phrase: “Nothing can happen to me!” It seems to me, however, that through this revealing characteristic of invulnerability we can immediately recognize His Majesty the Ego, the hero alike of every day-dream and of every

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 129 story.15

This oft-quoted explanation of how we create and/or perceive fictional characters is frequently included in anthologies of literary criticism, even though it strikes most scholars and writers as a highly reductive account. Freud would select Answer B as the correct one, because he considered human beings to be essentially egocentric in their relations to others. Thus the gratifications provided by the heroes and heroines of stories are egocentric ones, such as the wish to be invulnerable to pain, suffering, and even death, and/or the wish to be erotically irresistible. Writers mitigate the potentially repulsive egotism of their own personal fantasies by disguising them (displacing them onto characters) and by presenting such fantasies in an aesthetically pleasing manner. The real pay-off for the viewer, however, is not aesthetic experience per se, but rather “the release of still greater pleasure arising from deeper psychical sources."16

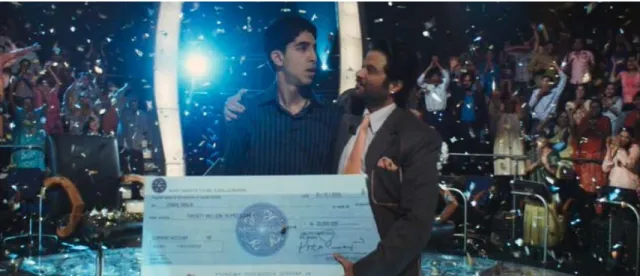

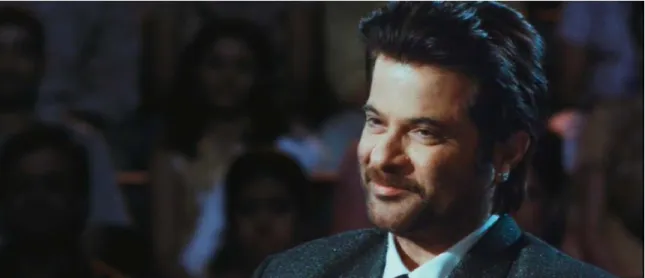

Were Freud to watch Slumdog Millionaire, he would not need a front-row seat to observe that the protagonist Jamal, who is literally tortured by the police in the first five minutes of the film, miraculously survives that ordeal (along with countless others throughout his life), and finally wins 20,000,000 rupees on the television gameshow (Fig. 3) and, against impossible odds, reunites with his childhood love Latika (Fig. 4). The final answer to the film’s opening question—D: It is written—also would seem to confirm Freud’s formula that “a special providence” protects the hero. The film serves up ego-gratification in massive doses, he would likely argue. He might also offer the following clarification: that, to the extent that the film fails to please some viewers, it is because some aspect of characterization or plot interferes with the viewer’s identification process, causing it to go awry and creating alienation or anger instead (failed gratification).

Fig. 3: Jamal receives a giant check from gameshow host Prem Kapur (played by Anil Kapoor) after winning the top prize.

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 130 When we view Slumdog with Freud’s theory in mind, the film does seem to confirm the notion of egocentrism in art: the protagonist is a stand-in or proxy for the viewer, whose own wishes and fantasies are vicariously gratified—if not at the beginning, then at the end. Jamal evades a large cast of malevolent characters, wins a fortune, and gets the girl of his dreams.

Fig. 4: Latika (played by Freida Pinto) and Jamal reunite in the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus in Mumbai.

In contrast to Freud’s account of the narcissistic gratifications provided by fictional protagonists and their quests, which leaves little room for the question of empathy or intersubjectivity, one may weigh more recent theories of embodied cognition. The Italian neuroscientist Vittorio Gallese, one of the discoverers of the primate Mirror Neuron System (MNS), offers a different, and indeed revolutionary, account of intersubjective experience that in some ways contradicts the Freudian notion of a proxy self. Gallese has argued that humans possess a neural wiring that enables them to identify with each other. One internal mechanism enabling identification is the MNS, a system within the brain that responds to the perceived motions, actions, and expressed feelings of others. 17 According to Gallese, our MNS not only helps us to understand the intentions of others, but something broader still: the system (in relation to other brain relays) causes us, in some very real sense, to have the feelings of others, and to live them. He calls this empathetic experience “embodied simulation.” Gallese writes:

We human beings do not represent to ourselves in a necessarily explicit way the intentions guiding the behavior of others. The intentions directing actions are not, in fact, solely and exclusively expressed as propositions. These are embodied in the intrinsic intentionality of the action, insofar as that action is linked to a final state, a goal. According to my model, in many situations within daily life we don’t ascribe intentions to others;

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 131 rather, we simply take note of them. When we witness the behaviors and actions of others, thanks to embodied simulation, their intentional contents can be comprehended directly, without the need to represent them explicitly in the form of a proposition.18

Here and elsewhere, Gallese holds that we quite literally share the experiences of others. Interestingly, this relay mechanism is not a conscious one—nor is it an unconscious one, in the Freudian sense. Rather, it is a form of automatic response, a mode of immediate mental processing that happens before we cognize it—if we do so at all.

Gallese uses the metaphor of il corpo teatrale, the theatrical body, to describe this phenomenon of automatic understanding and identification, passed from one body to another, or to a group—not only in ‘real life,’ but also within theatrical and other performative practices. Gallese also proposes a neural basis for the human capacity for mimesis and for the evolution of the theatrical art form. According to his model, theatrical spectators are by no means passive; rather, they actively engage as conduits for the emotions and intentions projected by the actors on stage.

Faced with the above question, Gallese would likely answer C: The character is a second you. He explains, “By means of a shared neural state realized in two different bodies that nevertheless obey the same functional rules, the ‘objectual other’ becomes ‘another self'.19

Answer A: 'You imagine what it is like to walk in that character’s shoes' derives from an earlier understanding of intersubjectivity. According to that model, known as theory of mind, we understand the thoughts and motives of others because we have the capacity to reconstruct them as mental representations. There are different versions of theory of mind—some of which take our understanding of the mental states of others as a kind of automatic and innate ability, and others of which highlight ‘mind-reading’ as a form of predictive or knowledge that derives from our ability to mentally put ourselves in another’s shoes. As the philosopher Alvin Goldman explains:

[H]aving a mental state and representing another individual as having such a state are entirely different matters. The latter activity, mentalizing or mindreading, is a second-order activity: It is mind thinking about minds. It is the activity of conceptualizing other creatures (and oneself) as loci of mental life.20

For Goldman, empathy is closely related to simulation, that process of understanding the mental state of another by attempting to replicate or emulate it within one’s own mind. Empathy and simulation are also connected to identification, in his view. Goldman’s simulationist version of mindreading, particularly in its most recent presentations, overlaps somewhat with that of Gallese’s concept of embodied mind, yet foregrounds the cognitive over the emotional.

Answer D: ‘The character gets under your skin’ has a slightly different force than Answer C, though Gallese might also weigh this possibility. In this construction of intersubjectivity, the shared manifold gives rise to challenges to identification and empathy based on sometimes

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 132 overwhelming, difficult, painful, or unwanted feelings and thoughts, seemingly imposed from without. This answer would attribute slightly more power to the other person, whether real or representational, to disrupt one’s psychic equilibrium. The resulting response may or may not be a fully empathic one, or may contain other emotional elements, such as personal distress, that make it harder to classify. I shall return to each of these answers later in the essay.

“Religion! Interesting”: Identification and its Obstacles

Generally speaking, a filmmaker seeks to sustain his audience’s identifications with the central protagonist(s) throughout the film. If we accept Gallese’s theory of embodied simulation and of the shared, we-centric manifold of experience, then we begin to understand the ways in which filmic representations may indeed get under our skins. In other words, we are likely to experience in our bodies, albeit in a strongly muted form, what the protagonists are feeling or experiencing on the screen. Actors’ expressions may magnify those feelings. The nature of the viewers’ mirrored experiences will depend, in part, on their interpretation of the visual information that they are seeing—for example, facial or bodily expressions that convey emotion or feeling. Actors’ movements, camera angles, lighting, costume and other aspects of filmic representation will influence these interpretations, as well as real-time embodied feelings that they experience while watching the film.

But despite the neural substrate that viewers share with each other and with most other human beings, they may respond in quite different embodied ways to particular characters and events within a film. In the remainder of this essay, I shall consider one further example from Slumdog—a scene that has elicited strongly different reactions from viewers. These reactions seemed to depend, in part, on viewers’ degrees of familiarity with Hindu culture and on their knowledge of Hindu/Muslim relations, both recent and past. The riot scene became a topic of controversy among a segment of the viewing audience. The debate over this scene helps us to understand how cultural experiences configure what we see and feel--so much so, I argue, that viewers are quite literally not seeing the same text.

In Scene 30 of the film, Jamal appears onstage with Prem Kapur, host of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. “For 16,000 rupees,” Prem announces. “Religion! Interesting."21 While religion may indeed be interesting, it is not immediately clear why Prem makes this declaration. Prem’s expression—actually a series of small facial movements—poses a problem of interpretation for the viewer. Wearing a smile that borders on contempt, Prem’s face (fig. 5) cues the audience to wonder what it is that Prem may know about religion (apart from the impending question), or why religion may be particularly interesting in this context. Viewers who know that Jamal is a Muslim may anticipate that the 16,000 rupee question will be about Hinduism. Hence, Prem’s expression may convey that Jamal, a partial outsider to Hindu culture, is not likely to know the answer to the question, or that perhaps his answer may not be the ‘right’ one. Viewers who are not aware of the religious and culture affiliations of these characters (arguably a large segment of the American viewing audience) may have an entirely different set of expectations arising from the phrase “Religion! Interesting.” They may feel uncertain why a question about religion is

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 133 being asked on a gameshow in the first place.

Prem continues, “In depictions of God Rama, he is famously holding what in his right hand?” Jamal raises his head and eyes slowly as the camera cuts to a woman placing clothes out to dry next to railroad tracks, as a train roars by her crouching body. The scene then jumps to a public laundry area, where a beautiful young woman—Jamal and Salim’s mother—scrubs clothes while her sons splash in the brown water. In a series of shots that cut between her face, her sons, and the train tracks that run behind the pool, the camera shows her expressions shifting from maternal affection, to attentiveness as she looks behind her, to worry, and then finally to fear (fig. 6) as an armed mob appears behind the passing train, ready to set upon the vulnerable people in or near the pool.

Fig. 5: Prem prepares to ask the 16,000 rupee question about religion.

Fig. 6: The face of Jamal and Salim’s mother registers panic as she sees what the audience has not yet seen—an armed mob preparing to attack.

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 134 As she screams to her children to run away, the viewer, situated behind the mother, sees an attacker hit her in the face with a large stick. If we accept Gallese’s theories of embodied cognition, the viewer not only imagines what that blow must feel like, but feels a mirrored version of that horrific blow—one that leaves no marks, but that registers faintly as pain. To reinforce that feeling of violation, the blow is shown again in slower motion from a different angle as the mother falls backwards into the water.

Viewers are also highly likely to identify not only with the mother, but also with the two boys who witness the horrifying murder, and to feel their fear. The ensuing sequence shows the two boys running in terror through narrow streets, evading the violence taking place all around them. At one point they run into a blind alleyway, where they are confronted with a strange sight: a blue boy, about three years old, standing quite still in front of a house. The blue child stares at the two, while they look back in terror. For a few seconds the boys stand frozen in their places, until Jamal and Salim run away.

Fig. 7: A child dressed as the Hindu hero Rama appears in a blind alley during the riot scene.

The Blue Boy Conundrum

This strange figure, who appears nowhere in Vikas Swarup’s novel, was added by Beaufoy to the screenplay. His ambiguous appearance in the film’s riot sequence prompts many questions, including the following:

Question #3: What is the expression on the blue boy’s face?

A: Hatred B: Wrath

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 135 D: Not sure

Arguably, one’s answer to this question will shape how one experiences the rest of the film. For some viewers, the appearance of the child dressed as Rama suggests a certain politics on the part of the filmmaker—i.e., pro-Muslim and anti-Hindu. Such viewers may take this scene as a representation or evocation of a specific set of historical events: namely, the Bombay riots of 1992-1993, in which Muslims were systematically targeted by Hindu mobs.22 Depending on one’s point of view, this scene constitutes an appropriate retelling of an historical event, albeit in a fictional context, or a gross distortion of a long history of ethnic and religious conflict.

Other viewers unfamiliar with India’s recent history or its ethnic conflicts may have no idea what might be motivating the attack in this scene, much less the appearance of the boy. As evident in many discussions about the film after its release, many viewers outside of India did not understand the cultural references within this scene—particularly the sequence featuring the blue boy.

The film’s deliberate decontextualization of historical events is evident when one compares the film with the shooting script. Boyle opted to delete the following lines that appear in Scene 31 of the shooting script after the mother yells at her sons to run. These lines make the ethnic and religious dimensions of the conflict much clearer:

SALIM Krishna, quick!

Salim hold out his hand to Krishna who is wading with difficulty through the water. KRISHNA

No way! You’re a bloody Muslim. Get away from me!

The rioters leap the tracks and are upon them.

KRISHNA (CONT’D) They’re Muslims! Him and him!

MOTHER Go!

23

Perhaps recognizing that these lines would, for a variety of reasons, be highly inflammatory to Hindus, Muslims, as well as other ethnic and religious groups, Boyle excised the character

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 136 Krishna. Following the script, however, Boyle kept the blue boy, who appears in a stage direction of the shooting script. That direction states, “As [the two boys] head down the alley, they get glimpses of burning houses, fleeing women, a three-year old boy in a doorway, painted entirely in garish blue. He stares at them. In his hand he is carrying a bow and arrow."24This incident supplies Jamal with the answer to the 16,000 rupee question: Rama carries a bow and arrow in his hand. Presumably that is why Boyle did not cut this scene from the film, though it, too, proved extremely provocative to some viewers, while confounding to others.

Viewers around the globe have interpreted this scene differently, depending on their cultural formation, their awareness of history and world events, as well as innumerable other factors. Consider, for example, the reaction of one blogger, who records his visceral anger at the representation of Rama in this scene:

More disturbingly, you have the depiction of the blue bodied Rama whom Hindus consider as Maryada Puroshottam [the best among men] threatening to terminate the existence of the innocent Muslim children. To a question on with which weapons is Lord Rama depicted with in popular iconography, Jamal Malik the protagonist does not remember the grand Ram Lilas which happen across the country or Ram Kathas on televisions. Instead, a Hindu kid dressed immaculately like Lord Rama stand in the mid of a slum in a threatening pose. And one cannot miss the hatred being portrayed in the face and looks of that young Hindu kid, younger than even Jamaal. Even a 5 year old Hindu kid is a communal bigot and Rama is responsible for all the communal crap.25

This viewer would likely choose Answer A: 'Hatred' as the answer to the question posed above, because he literally sees hatred on the face of the blue boy. For this viewer, this scene uses children for inappropriate political ends. The boy dressed as Rama in effect places a negative and destructive face on Hinduism. The blue boy has gotten under this viewer’s skin, disrupting potential identifications with Jamal and Salim, and arguably causing personal distress.

Context is indeed everything. On another blog, a viewer asks the following question, searching for a cultural context in which to place a scene otherwise difficult to interpret. its ANGIE writes:

I don`t understand who the blue boy is, how he/it is relevant to the story that Jamal was telling, or what he/it is doing (he/it is just standing there and raising his left hand..?). It doesn’t seem likely that he/it was a figment of imagination because Jamal and Salim both saw him/it. Can someone please explain?26

Though this viewer does not comment on the expression of the blue boy, she might well pick D: 'Not sure', when asked to interpret the expression, precisely because no emotional content seems to have registered with her.

Another viewer offers the following answer: “In India, a lot of beggars dress up like Hindu gods to make extra money."27While providing some context, this viewer does not explain what the scene might mean in the context of this riot.

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 137 To offer a final set of examples, I cite the following exchange between three viewers of “Slumdog”:

Michelle said…

lord rama FREAKEDDDD me out omg. freaked me out during the movie( maybe cuz i was high) but it also scared me during the trailer and when i see a pic of this kid... god forbid i hallucinate that image cuz i will shit my pants. otherwise. slumdog was pretty sick.

Anonymous said...

From a European perspective, the appearance of Rama does not give the impression of a (blue) boy with hate in his eyes. The bow in the right hand is not according to rules of engagement. Bows are used with the left hand and arrows are in the right. Is it important to see the bow in the right hand? and why is it important ?

Angelicchika said...

I saw the movie and did some research on God Rama, and his appearance in the movie. Yes, he is a Hindu god, but he had his left hand upraised, and that symbolizes his blessing. My interpretation on that is that God Rama "blessed" Jamal and Salim with allowing them to stay alive, even though they were the enemy. Also, thinking about what Jamal said "If it wasn't for Rama and Allah, I 'd still have a mother," everything makes sense. Believing that God Rama blessed them with safety, Jamal is mad because God Rama blessed them, but didn't bless their mother. Also, on a religious term, your God (whichever one you believe in) is supposed to watch over you and keep you safe. Thus, stating that, Jamal is more than likely mad at God Rama and Allah because those gods allowed Jamal and Salim to be safe, but not their mother.28

While Anonymous, who self-identifies as European, states that the expression on the blue boy’s face does not convey hate, s/he does not clarify what the expression might convey instead. Anonymous also focuses on the significance of the hand, attempting to connect it to “rules of engagement,” but without reaching a conclusion. Anonymous might also choose D: 'Not sure'.

Michelle, in contrast, would probably answer B: 'Wrath'. This reading did not, in her case, result in a mirrored reaction of wrath on her part, but rather a sense of panic or terror, since she clearly does not identify with the blue boy, but with Jamal and Salim.

Meanwhile, angelicchika provides another quite different interpretation of the blue boy, who does not merely represent, but who is, in her view, the God Rama. Though the boys are “the enemy,” God Rama blesses them, thereby allowing them to stay alive. Arguably, this viewer would choose answer C: 'Divine Beneficence' as her answer, though she focuses on the hand gesture, rather than the face of the blue boy. After offering a 'Hindu' interpretation, she then proposes a non-sectarian addendum to her reading: “your God (whichever one you believe in) is supposed to watch over you and keep you safe.” Perhaps this viewer interprets the troubling

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 138 scene in such a way that preserves her belief in a protective god. In order to do so, she reads anger in Jamal’s reactions, though it is not clear in which scene she locates the visual or verbal evidence for her claim that “Jamal is more than likely mad at God Rama and Allah.”

Interestingly, angelicchika focuses on the hand gesture of the blue boy, rather than his facial expression. In Hindu iconology, the raised hand gesture on the part of Rama, as well as other heroes, gods and goddesses, indicates protection and grace.29 This viewer fixes on a different component of the visual text in order to elaborate her quite different interpretation of the blue boy scene.

Cognitive Slippage: Some Provisional Conclusions

It is not likely to surprise readers if I state that multiple interpretations of any text are both possible and likely, as the above-cited discussions suggest in fairly fascinating ways. Nor will it surprise anyone to learn that interpretations depend heavily on context, including the cultural, ethnic, and religious background of the viewer—to name three influential variables among millions of others. However, the problem of interpreting facial expressions and gestures becomes quite a bit more complicated when viewed through the lens of embodied cognition.

Neuroscientists, cognitive psychologists, and other researchers have offered major new insights into the bodily formatting shared by most human beings—i.e., the neural networks of the brain and the body. Drawing on his understanding of neuroscience, as well as phenomenology and psychology, Vittorio Gallese has been one of the principal theorists of the “we-centric” manifold of human experience, our potential to experience what others feel through a process of physical reflection or transference30enabled by the human Mirror Neuron System, together with other systems of cognition (as opposed to representing those feelings to ourselves in a purely or primarily mental manner). While our experiences of others’ feelings are not identical to those of the persons we perceive in real life or in filmic representations, they flow through us and register in our bodies. In a very concrete way, these feelings get under our skins—and into our bodies.

Represented feelings may get under our skins in other ways, as well. If we identify with a character, it will be painful for us to continue in that identification if, for example, he is tortured or abused. Jamal is, in fact, tortured and abused throughout the film, in ways that are precisely designed to get under our skins, to make us feel uncomfortable. Yet the pacing of each set of scenes, organized around the questions that Jamal successfully answers, enables viewers to maintain empathy and identification with the protagonist because they anticipate that he will triumph over his abusers. The alternating pace of the protagonist’s pain, defeat, and of humiliation on the one hand and jubilation and triumph on the other, intensifies the range of feelings experienced by viewers following the protagonist, keeping them attached. The joyful dance at the end of the film serves, in fact, as the viewers’ reward for having suffered through appalling abuse together with Jamal and other characters with whom they may identify.

Yet, as we have seen, there may be stumbling blocks in the way of the audience’s identification with, and empathy for, the protagonist. The riot scene in Slumdog Millionaire, together with the generally dismal picture of Mumbai conveyed throughout the film, made it

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 139 hard, if not impossible, for some viewers to relate to the film and its protagonist. Moreover, as the many reactions to the blue boy scene suggest, viewers literally saw different expressions conveyed by the face and hand of the child dressed as Rama—expressions that registered in their bodies in a variety of ways.

Viewers unfamiliar with Indian culture tended to be puzzled by the scene. Such viewers seemed unable to read the blue boy’s expression, to find meaning in it, and to feel anything in relation to the scene. Others saw hostility or hatred in the expression, and, perhaps in spite of themselves, felt hatred for the film. This feeling of hatred was predicated, if not on direct identification with the child in the scene, then with a negative construction of Hinduism seemingly embodied by the blue boy.31However, another viewer saw beneficence in the blue boy’s hand gesture, rather than hatred in his face.

Still another viewer felt herself on the receiving end of the blue boy’s wrath. This viewer seemed not to identify with the boy or with the religious and cultural value system he evokes for some other audience members; hence, her embodied experience was one of overwhelming fear.

Each of these reactions to the blue boy could also serve to reinforce or to undermine the viewer’s identification with Jamal, the protagonist. What this particular scene suggests about filmmaking practice is that every facial expression, every gesture, every movement of every character has the power to amplify viewers’ empathy for the protagonist, to modify it, play with it, or to derail it completely, either in intended or unintended ways.

While filmmakers and actors seek to guide their audience to certain interpretations, they cannot guarantee a particular outcome (even, for example, if the desired outcome is open-ended discussion of what happens in a particular scene). Moreover, in order to enter the same shared manifold of experience that other viewers may enter, we literally have to see the same things. But what we see in a film—as displayed, for example, on the face and hand of the blue boy in Slumdog Millionaire— may vary dramatically from one person to another.

I call this potential for quite different reactions on the part of individual audience members, as well as audience collectives, “cognitive slippage.” By this I mean the possibility of a wide range of perceptions and embodied responses to a visual prompt, particularly when that prompt is presented in a politically, ethically, and/or religiously charged context. Filmmakers may inadvertently create “dead ends” in their films—i.e., points in the filmic story where viewer reactions vary radically, so much so that a certain segment of the audience becomes permanently alienated from the protagonist and distanced from the storyline. Such is the case with the blue boy, who literally stands at the dead end of an alley, and who also embodied the dead end of the film for those viewers who were completely offended by his appearance and perceived expression, and by the social meanings seemingly attached to it. But for other viewers of Slumdog, many of whom have a limited and stereotypical understanding of Indian history, culture, and ethnic conflict, the blue boy scene, though puzzling and obscure, did not derail identifications with Jamal and with the apparent objectives of the film.

Slumdog Millionaire, a powerful and inventive film that attempted to speak to the desires and fantasies of a global audience, and that to a certain extent succeeded in doing so, also provides a useful context for assessing the mechanisms of empathy and identification across wide

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 140 cultural divides. In this essay I have briefly presented four modes of conceptualizing empathy and/or identification. Freud’s theory of readers’ narcissistic attachment to characters that embody their wishes and to scenarios that gratify them may still hold water, at least in some circumstances, though more recent theories of mind, such as Goldman’s simulation theory or Gallese’s concept of the “shared manifold” of experience highlight intersubjectivity instead. They also pull away from Freud’s egocentric understanding of art and its gratifications while moving toward “we-centric” explanations. Gallese’s account in particular emphasizes co-feeling—i.e., the emotions and sensations of a character that register in the body of the viewer.

The fourth mode of empathy featured in this essay, getting under the skin (a concept suggested by Danny Boyle’s comments on Beaufoy’s screenplay of Slumdog) is not exclusive of the other three, but nevertheless has its own distinctive features. Arising, in part, from the shifting crosscurrents of identification within a narrative, this form trends toward physical and psychic discomfort, toward personal distress, and potentially toward the rupture of empathy. This fourth mode may give ‘edgy’ films their edginess, perhaps because it is likely to give rise to cognitive slippage such as that provoked by the blue boy scene in Slumdog. Thus it may be considered the car chase of empathies, always threatening to go off a cliff.

Recent theories of embodied mind and intersubjectivity present new options for understanding how works of art get under our skins in ways that we may find thrilling or in ways that we may resent profoundly. What these theories do not provide, however, is a universal formula for creating blockbuster films. Cognitive slippage, our individual and collective capacity to perceive and interpret sensory prompts quite differently from each other, complicates the puzzle of intersubjectivity considerably. Art exists in the interstices of our collective perceptions, which are always imbued with the potential for multiple meanings and interpretations.

This is, of course, not news to those who study the reactions of test audiences, and who attempt to calibrate a film in order to engage the sympathies and interests of the largest possible segment of the viewing public. To do so in a global context, however, poses extraordinarily complex challenges. The risk is of gratifying one group’s tastes, beliefs, and wishes at the expense of another’s, and, too, of reinforcing cultural misperceptions and existing power differentials. The potential gain is of moving beyond individual and group narcissisms into a shared manifold of human experience, the philosopher’s stone of storytelling.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the helpful discussions of the film, and/or the suggestions and feedback on the ideas in this essay provided by Jayita Sinha, James Hammond, Eric Chapelle, Judith Kroll, and Alaka and Prashant Valanju. Their contributions have been invaluable.

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 141 Notes

1

Slumdog Millionaire: The Shooting Script. Screenplay by Simon Beaufoy, Based on the Novel Q & A by Vikas Swarup (New York: Newmarket Press, 2008), vii.

2

J.M. Tyree, “Against the Clock: Slumdog Millionaire and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” Film Quarterly 62.4 (2009): 34-39, p. 34. Electronic.

3

In an interview with Alkarim Jivani, Boyle describes how the nearly completed film came close to being scuttled when Warner Independents, one of the two distributors, was shut down. The project was saved by the interest from the organizers of major film festivals. See “Mumbai Rising,” Sight and Sound 19. 2 (Feb. 2009).

4

In addition to the eight academy awards garnered by “Slumdog” in 2009, IMDb notes an additional 100 awards granted to the film, plus 49 nominations. The International Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1010048/ Accessed 2/27/2010.

5

In his review of the film, Khalid Mohamed described ―Slumdog Millionaire as "a masterwork of technical bravura, adorned with inspired ensemble performances and directed with astonishing empathy." ―Cuts Straight to the Heart, Hindustan Times, Mumbai, Jan. 23rd, 2009. http://www.hindustantimes.com/Review-Slumdog-Millionaire/H1-Article1-370275.aspx Accessed on 2/27/2010.

6

In 'The Real Roots of the Slumdog' Protests, the New York Times Room for Debate blog, Chitra Divakaruni, Amresh Sinha, and Sadia Shepard comment on the strong reactions to the term ―slumdog by some Indian viewers, as well as problems of sensitivity within the film itself. Feb. 20th, 2009. http://roomfordebate.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/02/20/the-real-roots-of-the-slumdog-protests/?pagemode=print Accessed on 2/10/2010.

7

See, e.g., Alice Miles, “Shocked by Slumdog’s Poverty Porn,” Times Online, January 14th, 2009. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/columnists/guest_contributors/article5511650 .ece Accessed 2/27/10; and Madhur Singh, “Slumdog Millionaire, an Oscar Favorite, is No Hit in India,” Time, January 26th, 2009. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/columnists/guest_contributors/article5511650 .ece Accessed 2/27/10.

8

In Swarup’s novel, the protagonist is given the named Joseph Michael Thomas by Fr. Timothy Francis, the parish priest of St. Joseph’s Church of Delhi who adopts him as an infant. Seven days later, the “All Faith Committee” meets with Fr. Francis, demanding that the orphan be renamed, given his unknown parentage. Thus he is renamed Ram Mohammad Thomas, a name reflecting the main character’s possible Hindu, Muslim, and Christian ancestry. Vikas Swarup, Slumdog Millionaire (2005 [published as Q & A]; Harper Perennial, 2008), 42-45.

9

For a sampling of (in part) Hindu nationalist reactions to the film, see the blog “Islamic Terrorism in India,” http://islamicterrorism.wordpress.com/2009/02/23/anti-hindu-film-slumdog-millionaire-wins-8-oscar/ Accessed 2/12/2010.

10

Suzanne Keen, Empathy and the Novel (Oxford: Oxford U P, 2007), 4.

11

Ibid., 4.

12

Ibid., xii.

13

See, e.g., Understanding Indian Movies: Culture, Cognition, and Cinematic Imagination (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008), 1-13, et passim.

14

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 142 15

“Creative Writers and Day-dreaming,” in The Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. James Strachey, 24 vols., Vol. 9 (London: The Hogarth Press, 1959): 143-153, pp. 149-150.

16

Ibid., 153

17

In the early 90s, a group of scientists at the University of Parma in Italy make an astonishing discovery. While investigating the premotor cortex of macaque monkeys, a section of the primate brain connected to initiating bodily movements, these researchers learned that certain neurons in their subjects fired both when the macaques moved and when they observed the same movements by other primates. This fascinating discovery has led to broader theorizations of a similar set of neurons in the human brain, and to new theories of empathy and shared feeling.

For a good introduction to this field, see Giacomo Rizzolatti and Corrado Sinigaglia’s book Mirrors in the Brain—How Our Minds Share Actions and Emotions, trans. Frances Anderson (2006; Oxford: Oxford U P, 2008), or Marco Iacoboni’s engaging book Mirroring People: The New Science of How We Connect with Others (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2008). See also the writings of Vittorio Gallese, discussed in n. 18 below.

18

Vittorio Gallese, “Il corpo teatrale: mimetismo, neuroni specchio, simulazione incarnata,” Culture teatrali: studi, interventi e scritture sullo spettacolo 16 (2008): 13-38,

pp. 19-20With thanks to Albert Ascoli of the University of California, Berkeley, for assistance with this translation.

For additional information on Gallese’s concept of the shared manifold, see, e.g., “The Two Sides of Mimesis: Girard’s Mimetic Theory, Embodied Simulation and Social Identification, Journal of Consciousness Studies 16, No. 4 (2009): 21-44; “Before and Below Theory of Mind: Embodied Simulation and the Neural Correlates of Social Cognition,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 362 (2007), 659–669; “’Being like me’: Self-other identity, mirror neurons and empathy,” in Perspectives on imitation: From cognitive neuroscience to social science, ed. S. Hurley & N. Chater, Vol. 1 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005): 101–118; “Embodied simulation: from neurons to phenomenal experience. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 4 (2005): 23–48; “The roots of empathy: The shared manifold hypothesis and the neural basis of intersubjectivity,” Psychopathology 36 (2003): 171– 180; and “The ‘Shared Manifold’ Hypothesis: From mirror neurons to empathy,” Journal of Consciousness Studies 8 (2001), 33–50.

19

“Embodied Simulation: From Mirror Neuron Systems to Interpersonal Relations,” in Empathy and Fairness (Wiley, Chichester Novartis Foundation Symposium, 278): 3–19, p. 3.

20

Alvin I. Goldman, Simulating Minds: The Philosophy, Psychology, and Neuroscience of Mindreading (Oxford: Oxford U P, 2006), 3. In this recent book Goldman offers a simulationist theory of mind in contrast to the so-called theory theory of mind and the rationalizing theory of mind.

21

Here I follow the punctuation of the shooting script (29), though viewers may hear the punctuation in different ways as they watch this scene.

22

“Mumbai: A Decade after Riots,” Frontline 20, No. 14 (July 5

th -18 th , 2003). http://www.thehindu.com/fline/fl2014/stories/20030718002704100.htm.Accessed 2/28/2010. 23 Shooting script, 30-31. 24 Ibid., 31. 25

Saurav Basu, responding to the posting “Anti-Hindu film Slumdog Millionaire wins 8 Oscar [sic], Islamic Terrorism in India. http://islamicterrorism.wordpress.com/2009/02/23/anti-hindu-film-slumdog-millionaire-wins-8-oscar/. Accessed on 2/11/2010.

Image & Narrative, Vol 11, No 2 (2010) 143

26itsANGIE, “Slumdog Millionaire: The blue boy/god?”

http://answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20090228131038AAvpEks Accessed 2/28/2010.

27

Pretty, Ibid. Accessed 2/28/2010.

28

Michelle, Anonymous, and angelicchika, “The Visionary Slumdog Millionaire,” Forces of Geek.

“http://www.forcesofgeek.com/2009/01/visionary-slumdog-millionaire.html?showComment=1232499960000#c6006485193502429069 Accessed on 2/28/2010.

29

My thanks to Judith Kroll for pointing out the important iconological aspects of the hand gesture in this scene.

30

I use this term in its most literal sense of a “carrying across,” rather than in the psychoanalytic sense.

31

I say “seemingly,” because we do not know whether the boy dressed as Rama is Hindu, Muslim, or some other ethnicity or religion.

Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski, Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literature Affiliate at the University of Texas at Austin, studies the history of subjectivity and group identity formation. Her new book Globalization and Group Identity in the Renaissance will be published in 2011 by Cambridge University Press.