Natura denaturans: Asemicism and

Surreal Interconnectedness in the

Codex Seraphinianus

Sami

Sjöberg

Résumé

Le Codex Seraphinianus est un livre qui nous interpelle visuellement mais qui en même temps se dérobe à la lecture, par les textes asemiques, c’est-à-dire “privés de sens”, qu’il contient et par ses nombreuses images représentant des espèces imaginaires et des objets surréalistes. Le présent article défend l’idée que tant les textes que les images résistent à l’interprétation, quand bien même le refus du sens n’est pas le même dans les deux cas. Cette stratégie peut être appelée natura denaturans (“la nature qui dénature”). Ce concept désigne le processus qui combine des objets en soi parfaitement reconnaissables de manière à les rendre inhabituels, voire « non-naturels ». Ce faisant, le Codex tend à mettre en question l’identité ontologique et la stabilité d’espèces représentées tout en suggérant l’existence de certaines choses qui peuvent être cachées au sein du monde naturel. La biologie comparée de Roger Caillois, écrivain et sociologue, défend l’idée que l’esprit qui dépeint ces formes artificielles fait nécessairement partie de ce qu’il cherche à rejeter cognitivement.

Abstract

The Codex Seraphinianus is a visually engaging but indecipherable book, laden with asemic writing and evocative images depicting imaginary species and surreal objects. This essay argues that the script and images are equally asemic, but the latter’s lack of representation is determined in a distinct manner. The strategy is here termed natura denaturans (“nature unnaturing”), denoting a process where recognisable objects are combined in a way that renders them not only unfamiliar but also ‘unnatural’. Hereby the Codex aims to defy the ontological identity and stability of species while indicating what may be hidden in the natural world. The comparative biology of the author and sociologist Roger Caillois suggests that the mind depicting this unnaturality is necessarily a part of the very nature it seeks to cognitively repudiate.

Keywords

al asemicism; analogical reasoning; surrealism; comparative biology; Codex Seraphinianus; Luigi Serafini; Roger Caillois

“Il n’y a pas de quoi s’étonner : du comportement de l’insecte à la conscience de l’homme, dans cet univers homogène, le chemin est continu.” (Caillois 1938, 83)

The Codex Seraphinianus (1981, henceforth Codex), frequently portrayed as one of the most difficult twentieth-century books, is a textual and visual treatise composed by the Italian architect and artist Luigi Serafini (b. 1949). In a rare interview he characterized the motives behind the Codex’s language-like script: “language means meaning, it stimulates the desire to solve the mystery, to understand the meaning,” but to “decipher does not always mean to understand” (Babkina 2015). Serafini was referring to the many attempts to understand the script through software and decoders – all methods of deciphering that categorically reject the possibility of regarding the script as asemic writing. Asemic writing is an oxymoron insofar as such writing bears the hallmarks of writing through its shapes, arrangement and context, but conveys no verbal

signification.1 In 2009 Serafini revealed that the writing in the Codex was not based on any existing or

invented language, thus debunking many of the previous theories and approaches regarding the book (see Stanley 2010, 8).

Any attempt to read the Codex becomes bifurcated due to its material character. Namely, the script forms only half of the mystery that requires the reader to cease to attempt to access a particular verbal meaning, or reading in general. Serafini’s playful hermeneutics set the script in dialogue with visceral images (see Fig. 1). The qualitative distance between the modes of expression is duplicated on nearly each spread of the book by virtue of a rather straightforward arrangement: the left side contains indecipherable script whereas the right consists of images seemingly bursting with representative potential.

The renowned experimental writer Christian Bök has focused on the visual aspects of the book and described the Codex as “a work of natural history, more bizarre than any work by Linnaeus or Alembert,” since the

Codex describes an “arcane system of imaginary knowledge” (Bök 2011, 9–10).2 His characterization is rare as it does not regard the Codex as unilaterally humorous, hallucinatory or depicting some other world, such as a “hypothetical land, nation, or dimension” (Schwenger 2001; Albani and Buonarroti 2010, 193; Melka and Stanley 2012, 141). Demarcations that assign the Codex to the regime of ‘the other’ illustrate the basic human need to relegate the unfamiliar to the sphere of fantasy and thus neutralize it as a form of fiction. Arguably, the Codex has critical potential when it is regarded as depicting this world, which is referred to as the natural world in this essay. Indeed, a critical observer should focus on what the book reveals about our underlying conventions of relating to our environment or umwelt – in its Uexküllian sense an environment seen from the point of view of a particular organism – and how we conceptualize or attempt to make sense

of the world.3

1 According to the visual poet Tim Gaze, asemic writing is a form or collection of forms that appear to be writing while “having no

worded meaning” (Gaze 2008a, 2; see also Brownie 2015, 54–55). Some of the numerous twentieth-century artists creating asemic writing include Max Ernst, Christian Dotremont, Jean Dubuffet, Henri Michaux, André Masson and the artists associated with the lettrist movement of Isidore Isou.

2 Bök’s allusion to pataphysics in the same text was anticipatory as Serafini was nominated a satrap for the Collège de ‘pataphysique

in 2016. This aspect emphasizes that the Codex should be regarded as an exception from nature and a departure from the law of non-contradiction. Moreover, the pataphysical dimension of the Codex highlights the humor with which the book portrays the encyclopedic tradition’s obsession with classifications and order.

3 Uexküll’s umwelt denotes nature surrounding the organism the way that the organism perceives it. In other words, it describes the

selective perception of features that are relevant to the subject. The concept derives from the Continental tradition of studying the behavior of animals in their natural environment whereby the umwelt relates first and foremost to flora and fauna (Uexküll 1926).

Serafini called the Codex “the book on principles of a world order of a nonexistent world,” but noted that an “encyclopedia is always a system and always a game, it is always a little bit of a joke” (Babkina 2015). In this sense, it follows the tradition of humorous or ‘mock encyclopaedias’ ranging from the Enlightenment period (e.g. Louis-Sébastien Mercier) to the early twentieth century (e.g. Fritz Mauthner), which critically illustrate what André Breton (1978, 201) called a “mania for classification,” itself exemplified by the Comtean omnipresence of logic. In the surrealist domain, examples include the para-surrealist critical dictionary published in stages in the journal Documents (1929–1931), Breton’s and Paul Eluard’s

Dictionnaire abrégé du surréalisme (The Abridged Dictionary of Surrealism, 1938) and the concise

feuilletons of the Da Costa encycplopédique (Encyclopaedia Da Costa, 1947) by the Acéphale group, to name a few. These instances not only attested to the playful character of the genre, but also criticized simplifying classifications, or, indeed, taxonomical processes in general. In addition, Serafini’s book coincided with the debates concerning postmodernism, which overturned the credibility of traditional

classifications in its critique of regimes of meaning.4 In this context, the Codex can be seen as a sardonic

commentary regarding its contemporary conceptions of nature and culture, universalism and relativism, language, and taxonomy.

This essay focuses on the material aspects of the script and images of the Codex. Hence, it does not delve into the cultural-historical semiotics of forms but rather studies the biological aspects of the Codex. In particular, the text analyses the process of natura denaturans (nature unnaturing), that is, how the book produces an ‘unnatural history’ by criticizing over-optimistic scientism. The notion of unnaturality highlights the critical aspects of the book, which are supplemented by approaching the natural world from a surrealistic point of view that extends or complements the more conventional depictions of our environment. Namely, the Codex exemplifies the observational (in contrast to the experimentality of science) aspect of natural history, but departs from strict scientific and objective observations so as to pursue more surrealistic avenues. Surrealism is an apt association not only because Serafini’s approach has occasionally been dubbed surrealistic, but also because surrealism refused to associate the natural world with its habitual representation (Schwenger 2006, 120; Kaitaro 2008, 49). Keeping in line with such a distinct mode of visual representation, the Codex can be seen as playing with the visual semiotics of historical renditions of epistemologies in the codex tradition. Historically, it evokes a melange of the works of the biologist Ernst Haeckel and the painter Hieronymus Bosch, ranging from astheticized natural objects to peculiar hybrids. In this context, the hybrids of the Czech surrealist Jan Švankmajer provide an apt comparison.

In addition to unfamiliar organisms, Serafini also included familiar natural elements in his book, such as recognizable maple, elm and birch leaves. This indicates that the Codex does indirectly depict the natural world (or, at least a world that overlaps it) by engaging in a mode of representation that is incongruous with it: visual asemicism. This mode of expression serves the purpose of critically reflecting on our conventional epistemological and taxonomical principles as well as, especially in the context of the Codex, the affective response that the unfamiliar and unnatural may invoke.

Serafini not only created a form of indecipherable script but extended the ‘mystery’ towards visual and psychological aspects. In order to study these aspects, I will concentrate on the asemic writing in the Codex,

4 For instance, Foucault’s Les mots et les choses (The Order of Things) rejected the idea of universal and historically applicable

argue that some of the visual aspects of the book are also ‘asemic’ and that they function in a network of signifiers. The unnatural history of the Codex can be seen in dialogue with surrealist interconnectivity, that is, analogical thinking that allows one to connect such epistemological regimes and modes of thought that are commonly considered distinct. As Breton wrote about the analogical method:

“Though held in honor in antiquity and the Middle Ages, [it] was therefore grossly supplanted by the ‘logical’ method which had led to our well-known impasse. The first duty of poets and artists is to re-establish analogy in all its prerogatives, taking care to uproot all the rear-guard spiritualist thought, always carried along parasitically, which vitiates or paralyses its functioning.” (Breton 1978, 280)

The interconnective method represented the principle of the coincidence of opposites in comparison with the scientific principle of non-contradiction. For the para-surrealist social scientist, philosopher and author Roger Caillois, this interconnective principle was also significant in the field of science, even though he remained more circumspect in his assessment of analogy (Roberts 2016, 296). Interconnective thinking is pervasive in

the ‘comparative biology’ developed by Caillois.5 He was drawing from Freud’s work on psychology through

evolutionary biology, but was original in its implementation.6 The incongruous method sought to combine

science and art in a holistic manner that engaged with the affective aspects of this affiliation. In short, Caillois (1938, 9) regarded myths – the manifestations of affectivity – as the focal points of imagination whereby they should not be limited to the cultural analysis of mythology but become the object of a novel, universal science based on interconnectivity. The objective of the present essay is to investigate what kind of epistemologically significant new knowledge this method may unveil from the Codex.

Nothing beyond Materiality: an Extended Asemic Taxonomy

Since its publication, there have been numerous attempts to solve the enigmas of the Codex, which consists of script in an unknown alphabet and images of equally unfamiliar and unnatural flora and fauna, hybrids, and their behavioral and social customs. Much of previous Codex-specific research has focused on possible meanings (e.g. Berloquin 2008, Coulthart 2002, Faucher 2011, Schwenger 2001), the existence of which Serafini categorically denied. Others have analyzed the fantastical elements of the book (Belfield 2007). The point of departure for most research has been how readers experience the Codex and how they engage with their prior experiences of reading and seeing.

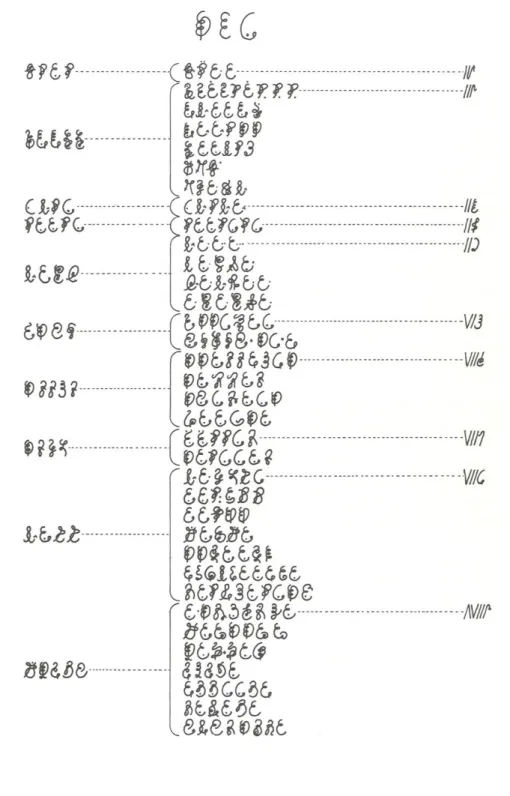

The book is constructed along the lines of the codex tradition, which is visible in its immediate reminiscence of encyclopedias and herbariums. It is divided into sections concerning the natural world and the ‘humanities’ (‘cultural’ interaction). Most of the spreads combine script with images depicting unfamiliar species. The pages of the Codex appear to be indexed. “That’s why descriptions, schemes and chapters of text were essential in the Codex – that’s the principle of an encyclopedia,” Serafini noted (Babkina 2015). Indeed, the

Codex maintains a rather strict structure where individual chapter headings are followed by taxonomy-like

tables (see Fig. 1), images of individual plant or animal ‘species’, and what can be regarded as visual ethological descriptions. According to the summary by Melka and Stanley (2012, 141), the book delineates

5 To my knowledge, there is no prior research on the relations between the Codex, Serafini and Caillois, even though Caillois’s later

writings on the ‘diagonal sciences’ and the poetics of stones seem to share the interconnective aspect of the Codex (see Caillois 1960 and 1975).

“mathematics, geometry, chemistry, anatomy, biology, culinary arts, technology, fashion designs, writing systems, sports, [and] natural phenomena.” In other words, much of its content represents familiar, even everyday phenomena, so assessments of its otherworldliness may have been somewhat premature.

The script has been arduously analyzed because of its characteristics that resemble writing. The resemblance to writing in the Codex is due to some commonly applied devices in world scripts, such as word or paragraph separators, upper case letters, stylistic variants, diacritic marks, possible ligatures, and mirror-like images of characters (Melka and Stanley 2012, 160). In fact, the page-numbering system has been resolved using base-21, that is, the Codex uses 21 symbols for numbers instead of the decimal system ranging from 0 to 9 (Derzhanski 2004). However, regardless of this abundance of (what are seemingly) signifiers, the script itself has kept its unreadable and unbreakable character. After Serafini’s disclosure to the Oxford University Society of Bibliophiles in 2009, it became appropriate to define the script as asemic writing, a form of writing where the “written material has no discernible semantic content” (Gaze 2006). Beyond the material aspect of the script, asemic writing has at least a threefold connotation: neuropsychiatric (asemia, the inability to understand and express signs and symbols), somatic (the bodily act of writing) and medial (what medium or media such writing potentially represents or challenges). One of its key characteristics is that asemic writing “differs from all other expressive modalities such as drawing and writing because it does not necessitate an

effortful structuring of one’s inner experience” (Winston, Mogrelia & Maher 2016, 144).7 In a like manner,

Serafini formulated that: “[a] hidden meaning in itself was not enough, they [the readers of the Codex] needed a hidden meaning that could be deciphered. I don’t believe in such tricks” (Babkina 2015). This is to say that such writing lacks the underlying context of language and the conceptual structuring of cognitive, ‘inner’

representation; in other words, there is no referential relationship between an asemic mark8 and what it

potentially signifies – or, in fact, does not signify. In Saussurean terms, the asemic mark lacks a referent.

The material aspect of asemic writing is, however, far from being completely free of potential signifiers. Its writing-like appearance results from its similarity to conventional alphabets and other characteristics of writing, some of which are listed above. Asemic marks do not function as language, because the reader (or viewer) has no access to potential (hidden) referents. However, I suggest that these marks refer to other, more conventional markings and letters (signifiers), and gain their significance from such a network of signifiers. That is, asemic writing is interpreted as ‘writing’ due to our cultural expectations regarding the material face of writing and the contexts in which it is usually found – books. Due to such expectations, the reader anticipates significative writing in the spreads (Fig. 1). This is to say that asemic marks are in fact connected to the abundance or overdetermination of referents in the network, even though they do not convey meaning themselves.

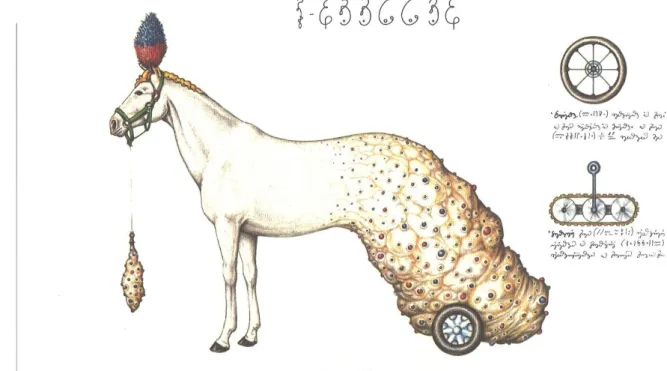

In a like manner, surrealist interconnective thinking functioned on the basis of a similar abundance of signifiers that would engage the imagination in order to create referents for these signifiers. The primacy of images granted by the surrealists enables the mobilization of the imagination. In the context of the Codex, this means that the visual signifiers in the book (for instance, a hybrid of a horse and a caterpillar, see Fig. 2) do not unilaterally denote objects, things or beings in the natural world, but rather function based on a network of signifiers.

7 Due to the article being written in the field of psychology and not art research, it does not take into account the various types of

related surrealist techniques, such as automatic drawing or the cadavre exquis.

8 The term ‘mark’ is applied here due to its etymological connotations, which retain the senses of ‘boundary’ (lack of a signified or

Figure 2. A horse-caterpillar hybrid exemplifies visual asemicism.

The image above features plenty of signifiers that are meaningful from a biological aspect and that play with hermeneutics (how we identify species). The caterpillar half is portrayed rather realistically considering its form, coloring and structure – with the exception of the wheel, a cultural signifier. The horse half, for its part, exhibits a domesticated animal (based on the cultural signifiers, such as the bridle and the plume). There are, indeed, plenty of signifiers and corresponding referents for each of these halves. However, their hybrid lacks a referent in the natural world, whereby it can be regarded as asemic. The hybrid gains significance due to the resemblance of its respective halves to the natural world. Yet, the limits of the known natural world are transcended in their combination. The hybrid can be identified as a horse-caterpillar, but a ‘species’ bearing an exact likeness to the one in the image does not exist (and is nameless). There is nothing beyond the image with the exception of the signifying potential the asemic mark (horse-caterpillar) gains from the network of signifiers that constitutes it (horse half/caterpillar half). In a manner of speaking, the asemic mark lends its reference, even though it is almost comically overdetermined by the sheer number of signifiers.

In an attempt to provide a taxonomy of modes of pictorial and written expression, the visual poet Tim Gaze has identified an axis that extends from abstract images to legible writing and negotiates between text and image. He modelled a continuum of types of “penned expression,” which ranges from recognizable images to legible writing through abstract images and asemic writing (Gaze 2008b, 13). However, this classification lacks a category that would include the images of the Codex, which are not all unambiguous or recognizable. Hence, Gaze’s taxonomy should be amended with asemic images as follows:

Asemic images have no discernible semantic content insofar as ‘semantic’ refers to the conventions of

representation.9 Abstract images (as opposed to non-objective images that are not based on resemblance or

representation) tend to relate to a given context, be it, for instance, the natural world or an emotional state.

Asemic images, on the other hand, are images that lack a referential relationship to the natural world even though the images (or their components) take part in a network of signifiers. The network enables the generation of an affective response, because of the resemblance. This characteristic derives from them becoming part of a network of signifiers in the act of interpretation. What Gaze did not explicitly mention in his definition of asemic writing was how asemicism depends on the social dimension: asemic writing and images are approached based on community-specific conventions of reading, seeing and interpreting. Aptly, Serafini noted that the Codex “gets overgrown with processes and phenomena” due to the conventions of reading (Babkina 2015). Asemicism makes these conventions manifest while enabling the emergence of the network of signifiers.

Visual Asemicism in the Codex: an Unnatural History

The unnatural ‘species’ depicted in the Codex depart from the natural world and its representations. Serafini did not settle for random ensembles of visual images, but formed genealogical trees in the vein of the biologists and naturalists Haeckel and Charles Darwin. This link to biology and natural history only highlights the unnatural history presented in the Codex. Such a history denotes a complementary and extensive view of the natural world from a surrealistic point of view. In the surrealist view, there is a cognitive drive to render forms (here, asemic marks) comprehensible. Thereby there is no natural world without a culturally formed mind to receive it, which explains the actuality of myths in their contact with the unfamiliar

and the unnatural.10

The novel term natura denaturans describes the significance that visual asemicism gains in the Codex. The medieval and Spinozian tag natura naturans encapsulates the idea of nature as self-generating, dynamic and animate whereas the verb denaturans connotes nature producing something other than ‘nature’ while

simultaneously dissolving the habitual ontological categories and links between organisms in that nature.11

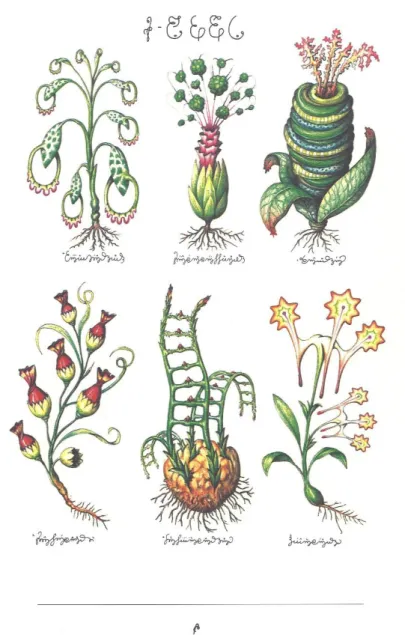

The denaturing can be seen as an ‘unnatural’ genealogical process. One the one hand, organisms in the natural world tend to evolve based on functionality, be it survival or procreation. For instance, the lavish appearance of flowers, their colors and their scent, are conditioned by pollinators and how these pollinators perceive and observe their umwelt (for example, only a few insects are able to see the color red). In other words, they share an environment. On the other hand, Serafini’s flora includes various characteristics that seem inessential when compared with the organisms of the natural world. Examples include plants that seem to morph into the shapes of wicker baskets and lampshades. Even if this transformation would occur between the natural and the cultural (such as the hybridity in the surrealist Max Ernst’s collage book Une semaine de bonte, 1934), the result is a mark that is neither natural nor cultural – only some aspects of it may be.

9 Indeed, the etymology of the word ‘semantic’ derives from sema ‘sign, mark, token; omen, portent; constellation; grave’ and from

the root *dheie- ‘to see, look’ (Weekley 1967, 1093).

10 Yet, biologically, such a mind is necessarily a part of the natural world. This is a particularly important note as the surrealists

rejected the Cartesian divide between nature and humans.

11 The later appropriations of the concept of umwelt in biosemiotics depict each organism having a particular umwelt and when

Instead of the representative genealogies formed by Haeckel and Darwin, Serafini’s ‘evolutionary’ processes remain obscure. The unnatural history in the Codex is, rather, based on appearance and mythology, which can be illuminated by Caillois’s approach to appearances. He surmised that:

“Surrealism can thus take as the maxim of its experience Hegel’s self-evident aphorism: “Nothing is more real than the appearance considered as appearance”. This aphorism is also an epigraph of all poetry which refuses to take advantage of its artistic privileges in order to present itself as science. Poetry, then, becomes a violently unilateral principle, siding on the marvellous and the unusual; and it strives, independently of any other consideration and by whatever means, to take into account the irrational element within the object.” (Caillois 1990, 8)

The marvellous (le merveilleux)12 signifies a destabilizing incursion of the surreal into everyday life. By

focusing on the marvellous, Caillois sought to posit it as an element of the natural world, which would exemplify the interconnectedness of nature and the human mind – the mind perceiving the natural world. Appearances, resemblances and myths played key parts in this quest. Namely, in Cailloisian thinking, appearances are what not only create affective responses but also link objects and phenomena together: in this sense appearances are mythological. A myth constitutes a site of emotional investment, that is, myths are able to generate affective movements (Caillois 2003a, 69n1). In short, myths (as products of human imagination) are based on the ‘affective necessity’ to react to natural phenomena (Caillois 1938, 23). In the

Codex, these affective moments are evoked by the processual denaturans where recognizable objects and

organisms are combined in a manner that would not be possible in the natural world, due, for instance, to transplant rejection according to biological processes and organic factors such as DNA incompatibility, or to the sheer differences in scale with which Serafini plays (see Fig. 2).

Instead of the abstract, biomorphic shapes favoured by surrealists like André Masson or Joan Miró, the Codex

depicts ‘species’ whose appearance shares some basic features with organisms more familiar to us.13 In fact,

Ernst and Salvador Dalí have made use of slippages between the human, vegetal and animal realms (see Roberts 2016b, 223). Predating the Codex by some years, the collages of Švankmajer portray melanges between species, including humans. Especially his Bilderlexikon series (1971–1973) of graphic works is laid out akin to works in natural history and include sections such as anthropology and zoology. Stylistically, his work appears as a mediator between early twentieth-century surrealist collage works and Serafini’s encyclopedia. For instance, Serafini’s fauna have characteristics relating to sensory aspects (eyes, ears, whiskers) and motion (tails, legs, paws), and flora tends to include roots, leaves and inflorescence (see Fig. 3). The book features non-existing plants and a vast array of unnatural hybrids: grafted plants, plant hybrids, hybrid animals (e.g. the horse-caterpillar), plant-animal hybrids (such as a stag’s head with tree antlers and roots growing in a flower pot) and hybrids of organic and inorganic matter (e.g. a carrot including a glass-like compartment containing a homunculus, and a human with a pen for a hand). Due to their resemblance to

12 For André Breton, the marvellous presented a gap in signification whose causes remain unexplained and which aims to produce

a break in discursive thinking. The intended aim was to propel the mind to a ‘higher sphere’ of receptivity. The marvellous was significant in analogical thinking due to its ability to unveil potential connections (see Bauduin et al. 2018, 9). It was pr esented by Breton in Nadja (1918), where he noted: “Perhaps life needs to be deciphered like a cryptogram. Secret staircases, frames from which the paintings quickly slip aside..., button which must be indirectly pressed to make an entire room move sideways or vertically, or immediately change all of its furnishings; we may imagine the mind’s great adventure as a journey of this sort to the paradise of pitfalls.’ (Breton 1960, 112)

13 Such features recur in, for instance, Miró’s lithographs and paintings, Ernst’s Maximiliana (1965) and Masson’s Anatomie de

natural world species, and while balancing between the natural and the cultural, these hybrids are able to generate an affective response. Such a response is supported by Italo Calvino’s characterization of the

Codex’s visual contents as teratological (Calvino 2015, 144).14 His interpretation emphasizing teratology already suggests an affective response caused by the ‘unnaturality’ of the organisms. However, instead of abnormalities or mutations, the Codex is a display of idiosyncratic autopoietic processes – one may surmise that this flora is supposed to grow this way, as there is no evidence proving otherwise.

Figure 3. Flora in the Codex present unnatural evolutionary shapes.

These instances of visual asemicism establish a regime between the natural world and the otherworldly fantastic: the marvellous surreal. Especially the legacy of Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms in Nature, 1904) is as topical here as Serafini’s play with scale. The unfamiliarity of the organisms’ environment lead to a more comprehensive view of the natural world. Consider the creatures of the deep uncharted oceans or the microscopic level of our umwelt that is beyond the scale of human perception. For instance, some of

14 Teratology refers to the study of abnormalities of physiological development, which encompasses human congenital and

Serafini’s drawings resemble foraminifera that are microscopic animalia we never see without the aid of technology – yet they belong to our umwelt.

Visually and taxonomically the Codex is balanced between two aspects, namely the unfamiliar and the unnatural. The former category encompasses organisms that are included in our umwelt even though they are beyond our perceptive capabilities. The latter includes representations that could not become real according to our current understanding of organisms and their biological development. For instance, the various Codex hybrids that include inorganic material in their composition, such as a root with a tap on it, ontologically form a single ‘species’. The context suggests that the tap is not added to the plant but is rather an integral part of the ‘species’. Humans are far from being exempt, which is exemplified by the writer-artist with a pen for a hand. The ‘transhuman’ perspective highlights the unnatural aspects of these hybrids, even though the

Codex does not portray them as augmented humans: there is no distinct boundary where the pen ends and the

arm begins.15 This is to say that, yet again, the asemic marks involved fail to constitute a proper referent in

the natural world.

These unnatural organisms represent visual asemicism because they lack any direct referential relationship to the natural world. The aspects of unfamiliarity and unnaturality are related through the surrealist idea of interconnectedness (analogical thinking). This interconnectedness is able to illustrate how visual asemicism – images that have no referential relationship – may still evoke an affective response. These images resemble species of the natural world due to shared characteristics whereby they gain their asemic ‘value’ in relation to other signifiers that are referential, for instance, the network of signifiers, based on resemblances, that includes colors (e.g. green implying the presence of chlorophyll), forms and plant parts as described above, but also the more unnatural ones such blossoms resembling ladders and shooting stars. Cailloisian comparative biology is able to tackle these resemblances that exemplify the engagement with the natural and the cultured mind.

Comparative Biology and the Objective Ideogram

Comparative biology was meant to be a solution to the contemporary atomization of research and knowledge regarding the natural world. It combined biological and psychological (or, psychoanalytical) aspects, thus establishing a continuum between nature and the human mind. The approach was greatly indebted to Freud’s theories regarding biology, psychology and myth, and whose metapsychology was based on the theories of Darwin and Haeckel (Gould 1977, Sulloway 1979). However, Caillois’s originality derives from his adoption of a structural mode of comparative thinking that originated in the nineteenth century, and its application to the surrealist ends of connecting the instinct of insects with the psychology and mythology of humans.

The theory illustrated analogical thinking where biological and affective elements were interconnected.16 In

the interconnective endeavor, the ‘objective ideogram’ (idéogramme objectif) functioned as the linking factor. Caillois (2003a, 80) stated that objective ideograms “concretely realize the lyrical and passional

15 Indeed, current debates regarding transhumanism, especially the unnaturality argument, are a real- life instance of such hybridity

and the affective response it evokes (see e.g. Hansell and Grassie 2011; More and Vita-More 2013).

16 The main ideas were introduced in Caillois’s two early essays on insects in the 1930s: ‘La mante religieuse. De la biologie à la

psychanalyse’ (The Praying Mantis: From Biology to Psychoanalysis, 1934) and ‘Mimétisme et la psychasthénie légendaire’ (Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia, 1935).

virtualities of the mind [de l’affectivité] in the outside world.” In short, the objective ideogram mediates between affectivity and the external world, and can be regarded as a more objective and culturally acute form of the Freudian ‘symbol’. However, as Rosa Eidelpes (2014, 3–4) has noted, Caillois did not lay out whether these ideograms referred to natural objects, the phenomenon itself, or inner representation. Yet, in the case of visual asemicism, it seems that there is no natural object or phenomenon, only a representation that draws attention to the absence of reference to the natural world.

In the context of the Codex, the objective ideogram can be regarded as a mediating component between the unfamiliar and the unnatural. For instance, phantoms and vampires do not belong to the natural world, but they may exert an influence on real phenomena (Caillois 2003a, 73; Saint Ours, 2001, 40). Through this affective dimension, Caillois wanted to tie the concept of the marvellous to nature. He sought to decipher “how a representation could have a separate and, as it were, secret effect upon each individual in the absence of any symbolic dimension, whose meaning was chiefly defined by its social usage and whose emotional efficacy stemmed from its role in the collectivity” (Caillois 2003a, 69–70). This allows for an asemic point of view, as social conventions not only steer the interpretation of asemicism (i.e. is it ‘seen’ or ‘read’) but also condition myths.

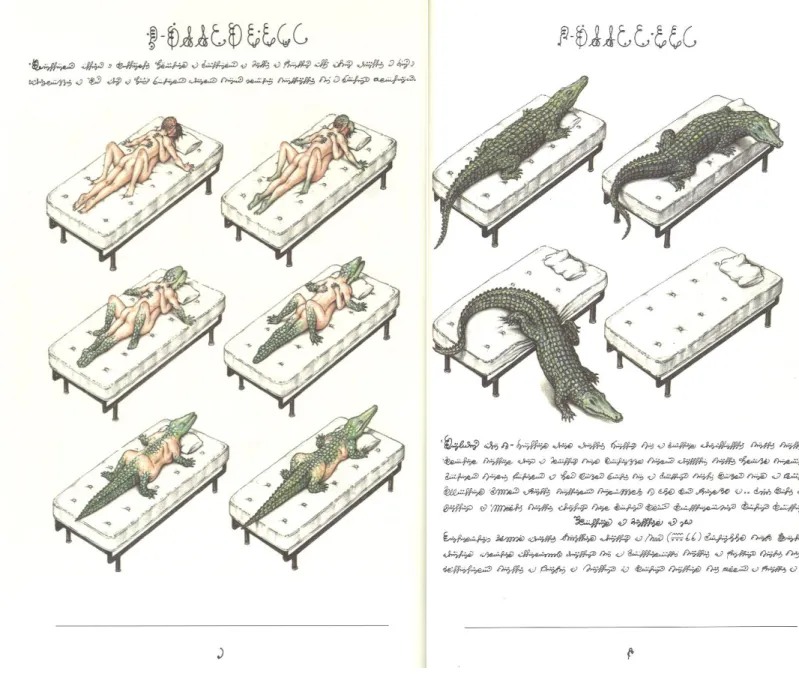

The relation between myths and biology can be exemplified by an interpretation of a sequence in the Codex. One of its most renowned scenes is the copulating human couple and their quite surreal transformation into a crocodile (Fig. 4). This is not a case of visual asemicism in the sense that these drawings depict objects of the natural world, but their transformation is rather unnatural. Paul Fisher Davies has interpreted the spread as a comic book feature that relies on identity transforming itself in space (the bed remains identical, the

couple turns into an animal).17 More importantly, he notes that an analogy is suggested: “lovemaking is

‘beastly’, that two lovers can become lost in each other, that they become one subhuman creature, that love grows dangerous” (Davies 2015, 124). Davies is correct to suggest this analogy, but does not delve further into the interconnective thinking that Seraphini’s image suggests.

17 Davies (2015, 124) notes that chronology is implied but uncertain, because the spread could exemplify nine couples in various

Figure 4. A couple transforming into a nonhuman animal.

Here the comparative biology of Caillois becomes a useful interpretative frame. Namely, it enables the

comparative analysis of the two simultaneous transformations taking place in the sequence. First is the obvious interspecies transformation where a human turns into an animal, which implies unity (man being part of nature). The second is an intraspecies transformation where two humans become one in the form of a nonhuman animal. This is particularly interesting if the boards represent temporal change as Davies suggests. In this case, two (human) minds seem to have become a nonhuman (and, hence, also a non-cultured) one, exhibiting a metaphorical continuum between nature and the human mind. The autonomy of the nonhuman mind is implied by the control the animal exerts over its movements and will, or instinct, to leave the bed. So, has a human been devoured in this interspecies transformation?

Both transformations are consistent with the surrealist aspects of the Codex. Yet, phagophobia, the fear of being eaten, is related to Caillois’s arguments based on comparative biology. Serafini’s crocodile does not embody the kind of entomological characteristics Caillois focused on, but it does evoke phagophobic anxiety. According to Caillois (2003a, 81), this fear was not merely a psychological phobia but a biological, vestigial

residue. This is to say that humans’ anxious relation to the notorious homophage, the crocodile as a

man-eater, is conditioned not by culture but rather by biological development, which is manifested via affects and

myths as their representation.18 In this context, Caillois adopted Freud’s theories regarding the biological

past, its continuously resurfacing vestiges and the developments in thinking about mythology.

In line with the comparative, interconnective thinking of Caillois, the link is mythological. The psychological background is in the surrealist idea of the femme fatale and the male’s fear of being consumed by her (Caillois 1938, 58; also Zuch 2004). Yet, according to comparative biology, the fear of being devoured by a woman (a textbook example of castration anxiety) is, in fact, a result of residual phagophobia. The sexual aspect of this phobia is accounted for by comparative biology where an embrace inevitably involves a victim and an executioner, the latter being the one who retains consciousness, stays alert and observes (Frank 2003, 66). The executioner thus has predator-like characteristics. Hence, does Serafini portray an interspecies transformation, a very Freudian-surrealist sexual fantasy, or both? In the Cailloisian frame, this parallelism reveals the interconnectedness of things through objective ideograms:

“At first glance it is quite possible to imagine the existence of a universe without objective ideograms. Yet, upon further reflection, one soon realizes that this raises the same insuperable obstacles as the idea of a world that is discontinuous and not overdetermined, albeit probably determined. Once again, it is utterly unthinkable that causal series could be totally distinct. This also contradicts experience, which constantly demonstrates their numerous intersections and sometimes supplies overwhelming, crushing expressions of their unfathomable solidarity. Although their meaning is hidden and ambiguous, such expressions [objective ideograms] never fail to reach their destination.” (Caillois 2003a, 80)

The character of the objective ideogram is hidden and ambiguous whereby it does not surrender to ‘typological’ critique, such as that presented by Eidelpes. Rather, the ideograms gain their interconnective potential by relating to natural objects, phenomena and representations. These aspects are interlinked, as the marvellous may well loom in everything.

In comparative biology, the vestigial residue, the anxiety, results in humans’ unique relation to biological

laws: in humans, biological laws do not condition action but rather representations. Hence, in Cailloisian

thinking the objective ideogram becomes a token of our biological condition, an illustration of the rootedness of myth in biological history. As a final note on the transformations described above, myths about crocodiles are abundant everywhere where their natural habitats have overlapped with those of humans and encounters have been inevitable. Through this aspect it is understandable that the phenomena people observe in nature ‘correspond’ to their psychological and biological structures, which, further, give rise to the creation of myths (Caillois 1938, 30; Eidelpes 2014, 4). Therefore, the crocodile may act as an objective ideogram in all three senses where it refers to the natural organism, phenomena and inner representation. The ideograms reveal the systematic overdetermination of the universe, which indicates the interconnectedness of all things.

18 Caillois was anti-Darwinian, which is suggested by his idea of vestigial residue that echoes the basic principles of Lamarckism.

The background is also Freudian to the extent that Freud’s engagement with evolutionary biology related to Haeckel’s biogenetic law (ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny) and Lamarck’s theory of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Caillois’s reading of Freud assisted him in structuring his thinking through the registers from the biological to the cultural.

Serafini’s world is a manifestation of such overdetermination where the unfamiliar and the unnatural interlink through affectivity. The Codex seems to display the human desire to recover from its original insensate condition, a desire comparable to the pantheistic idea of becoming one with nature (see Caillois 2003a, 79; 2003b). Serafini’s affective and mythological work seeks to evoke, as expressed by him, a mystery that demands to be understood. By ‘representing’ through asemic images, the Codex fails to relinquish its mystery but also encourages an understanding about the marvellous in an interconnected universe.

Surreal Holism

The Codex is able to unveil the conventions by which we regard, observe, analyze and classify our environment in such a habitual manner that we are not always aware of it. Serafini has arguably accomplished a denaturans approach in relation to the natural world, whereby the unfamiliar and the unnatural become aspects of nature. It opposes the reductionism characteristic of the scientific way of thinking, which reduces non-scientific modes of thought (such as mythological ones) to superstitions, which are deemed economically useless (see Roberts 2016b, 219). In the surrealist context, such a denaturans rupture in the fabric of everyday life was warranted by the marvellous. The interconnectedness revealed by the marvellous abides with objective ideograms, which link together natural objects, phenomena and cognitive representations while transcending the strict boundaries of association between these categories.

The interconnectedness based on resemblance steers the interpretation of asemic marks and images, which have no direct referential relationship to the natural world but rather rely on correspondence and similarity. As the Codex exemplifies, these images have traits that resemble natural objects. Thereby they take part in a network of signifiers where their resemblance to other representations (those based on the natural world) produces an indirect reference. That is to say that the unfamiliar and unnatural are linked through this network that includes the potentiality to represent. The objective ideogram works in a similar manner, producing connections between natural objects, phenomena and representations with the aim of linking nature with the

human mind. Le chemin est continu – the path is continuous.19

Bibliography

(Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material.)

Albani, Paolo and Berlinghiero Buonarroti. 2010. Dictionnaire des langues imaginaires. Translated by Edigio Festa. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

Babkina, Katerina. 2015. ‘Luigi Serafini on How and Why He Created an Encyclopedia of an Imaginary World’. Accessed October 12, 2018. Retrieved from https://birdinflight.com/media/luigi-serafini-on-how-and-why-he-created-an-encyclopedia-of-an-imaginary-world.html.

19 This article is part of the project Surrealism and Knowing: Avant-Garde, Science, and Epistemologies (SA316372), funded by

Bauduin, Tessel M., Victoria Ferentinou, and Daniel Zamani (eds.) (2018): ‘Introduction: In Search of the Marvellous’. In Surrealism, Occultism and Politics: In Search of the Marvellous, edited by Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou, and Daniel Zamani, 1–20. New York and London: Routledge.

Belfield, Richard. 2007. The Six Unsolved Ciphers: Mysterious Codes that Have Confounded the World’s

Greatest Cryptographers. Berkeley: Ulysses Press.

Berloquin, Pierre. 2008. Hidden Codes & Grand Designs: Secret Languages from Ancient Times to

Modern Day. New York and London: Sterling.

Breton, André. 1960. Nadja. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Grove Press. --- 1978. What is Surrealism? Translated by Franklin Rosemont. New York: Pathfinder. Brownie, Barbara. 2015. Transforming Type: New Directions in Kinetic Typography. London: Bloomsbury.

Bök, Christian. 2011. ‘Codex Seraphinianus’. In Michael Ondaatje et al., eds. 2011. Lost Classics: Writers

on Books Loved and Lost, Overlooked, Under-Read, Unavailable, Stolen, Extinct, or Otherwise Out of Commission, 9–12. New York: Anchor Books.

Caillois, Roger. 1938. Le mythe et l’homme. Paris: Gallimard. --- 1960. Méduse et Cie. Paris: Gallimard.

--- 1975. Pierres réfléchies. Paris: Gallimard.

--- 1990. The Necessity of Mind. Translated by Michael Syrotinski. Venice: Lapis Press.

--- 2003a. ‘The Praying Mantis: From Biology to Psychoanalysis’. In The Edge of Surrealism: A Roger

Caillois Reader, edited and translated by Claudine Frank, 69–81. Durham & London: Duke UP, 69–81.

--- (2003b): ‘Mimicry and Legendary Psychastenia’. In The Edge of Surrealism: A Roger Caillois

Reader, edited and translated by Claudine Frank, 91–103. Durham & London: Duke UP.

Calvino, Italo. 2015. ‘The Encyclopedia of a Visionary’. In Collection of Sand. Translated by Martin L. McLaughlin, 143–148. Boston and New York: Mariner.

Coulthart, John. 2002. ‘Another Green World: The Codex Seraphinianus’. Accessed January 10, 2019. Retrieved from http://www.johncoulthart.com/feuilleton/writings/another-green-world-the-codex-seraphinianus/.

Davies, Paul Fisher. 2015. ‘On the Comics-Nature of the Codex Seraphinianus’. Studies in Comics 6, no. 1: 121–132.

Derzhanski, Ivan A. 2004. ‘Codex Seraphinianus: Some Observations’. Accessed October 12, 2018. Retrieved from http://www.math.bas.bg/~iad/serafin.html.

Eidelpes, Rosa. 2014. ‘Roger Caillois’ Biology of Myth and the Myth of Biology’, Anthopology &

Materialism, no. 2: 1–18.

Faucher, Kane X. 2011. ‘On the Codex Seraphinianus’. SCRIPTjr.nl 2, no. 1. Accessed January 10, 2019. Retrieved from

http://scriptjr.nl/special-sections/cryptotexts/on-the-codex-seraphinianus-kane-x-faucher#.XDdFClUzY-U

Frank, Claudine. 2003. ‘Introduction to “The Praying Mantis”’. In The Edge of Surrealism: A Roger

Caillois Reader, edited and translated by Claudine Frank, 66–69. Durham & London: Duke UP.

Gaze, Tim. 2006. ‘Asemic’. Accessed October 12, 2018. Retrieved from http://www.asemic.net/. --- 2008a. Asemic Movement 2. Accessed October 12, 2018. Retrieved from

https://issuu.com/eexxiitt/docs/asemicmovement2.

--- 2008b. Asemic Movement 1. Accessed October 12, 2018. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/eexxiitt/docs/asemicmovement1.

Gould, Stephen Jay. 1977. Ontogeny and Phylogeny. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Hansell, Gregory M. and William Grassie, ed. 2011. H+/-: Transhumanism and its Critics. Philadelphia: Metanexus.

Hoffmeyer, Jesper. 1996. Signs of Meaning in the Universe. Translated by Barbara J. Haveland. Bloomington: Indiana UP.

Kaitaro, Timo. 2008. Le Surréalisme: Pour un réalisme sans rivage. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Melka, Tomi S., and Jeffrey C. Stanley. 2012. ‘Performance of Seraphinian in Reference to Some Statistical Tests’. Writing Systems Research 4, no. 2: 140–166.

More, Max and Natasha Vita-More, eds. 2013. The Transhumanist Reader: Classical and Contemporary

Roberts, Donna. 2016a. ‘Surrealism and Natural History: Nature and the Marvelous in Breton and Caillois’. In A Companion to Dada and Surrealism, edited by David Hopkins, 287–303. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

--- 2016b. ‘The Ecological Imperative’. In Surrealism: Key Concepts, edited by Krzystof Fijalkowski and Michael Richardson, 217–227. London and New York: Routledge.

Saint Ours, Kathryn. 2001. Le fantastique chez Roger Caillois. Birmingham: Summa Publications.

Schwenger, Peter. 2001. ‘Codex Seraphinianus: Hallucinatory Encyclopedia’. Accessed October 12, 2018. Retrieved from http://faculty.msvu.ca/pschwenger/codex.htm.

--- 2006. The Tears of Things: Melancholy and Physical Objects. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Serafini, Luigi. 2013. Codex Seraphinianus. New York: Rizzoli.

Stanley, Jeffrey C. 2010. To Read Images not Words: Computer-Aided Analysis of the Handwriting in the

Codex Seraphinianus. Master’s thesis, North Carolina State University.

Sulloway, Frank. 1979. Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Uexküll, Jakob von. 1926. Theoretical Biology. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co.

Weekley, Ernest. 1967. An Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. New York: Dover.

Winston, Christine N., Nazneen Mogrelia, and Hemali Maher. 2016. ‘The Therapeutic Value of Asemic Writing: A Qualitative Exploration’. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health 11, no. 2, 142–156.

Zuch, Rainer. 2004. ‘Max Ernst, der König der Vogel und die mythischen Tiere des Surrealismus‘. In

kunsttexte.de, no. 2, 1–13.

Sami Sjöberg is an Academy of Finland Research Fellow at the University of Helsinki and an Adjunct

Professor at the universities of Helsinki and Tampere. His areas of expertise and interest include

avant-garde and experimental literature, science in modern literature, 20th-century history and philosophy of

science, and East-Central European modernisms. His publications include Jewish Aspects in Avant-Garde:

Between Rebellion and Revelation (2017, ed. with Mark Gelber), The Vanguard Messiah: Lettrism between Jewish Mysticism and the Avant-Garde (2015), and numerous articles and essays on European avant-gardes.