Publisher’s version / Version de l'éditeur:

Journal of Power Sources, 202, pp. 269-275, 2012-03-15

READ THESE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE USING THIS WEBSITE.

https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/copyright

Vous avez des questions? Nous pouvons vous aider. Pour communiquer directement avec un auteur, consultez la

première page de la revue dans laquelle son article a été publié afin de trouver ses coordonnées. Si vous n’arrivez pas à les repérer, communiquez avec nous à PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Questions? Contact the NRC Publications Archive team at

PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca. If you wish to email the authors directly, please see the first page of the publication for their contact information.

NRC Publications Archive

Archives des publications du CNRC

This publication could be one of several versions: author’s original, accepted manuscript or the publisher’s version. / La version de cette publication peut être l’une des suivantes : la version prépublication de l’auteur, la version acceptée du manuscrit ou la version de l’éditeur.

For the publisher’s version, please access the DOI link below./ Pour consulter la version de l’éditeur, utilisez le lien DOI ci-dessous.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowrsour.2011.11.047

Access and use of this website and the material on it are subject to the Terms and Conditions set forth at

Investigation of CrSi2 and MoSi2 as anode materials for lithium-ion

batteries

Courtel, Fabrice M.; Duguay, Dominique; Abu-Lebdeh, Yaser; Davidson,

Isobel J.

https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/droits

L’accès à ce site Web et l’utilisation de son contenu sont assujettis aux conditions présentées dans le site LISEZ CES CONDITIONS ATTENTIVEMENT AVANT D’UTILISER CE SITE WEB.

NRC Publications Record / Notice d'Archives des publications de CNRC:

https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=3a1e8729-81d6-4410-bc97-45d36fd026a1

https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/objet/?id=3a1e8729-81d6-4410-bc97-45d36fd026a1

ContentslistsavailableatSciVerseScienceDirect

Journal

of

Power

Sources

j ou rn a l h o m e pa g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / j p o w s o u r

Investigation

of

CrSi

2

and

MoSi

2

as

anode

materials

for

lithium-ion

batteries

Fabrice

M.

Courtel, Dominique

Duguay, Yaser

Abu-Lebdeh

∗, Isobel

J.

Davidson

NationalResearchCouncilCanada,1200MontrealRoad,Ottawa,OntarioK1A0R6,Canada

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received7October2011 Receivedinrevisedform 14November2011 Accepted15November2011 Available online 25 November 2011

Keywords: CrSi2 MoSi2 Silicide Li-ionbatteries Anodematerial

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

WereportonthesuitabilityofthetwometalsilicidesMoSi2andCrSi2 asanodematerialsforLi-ion

batteries.Thetwomaterialsweresynthesizedbyhighenergyballmillingofthecorrespondingmetals andX-raydiffractionwasusedtofollowtheevolution/formationofthecrystallinephases.Thein-house preparedpowdershaveshownbetterbatteryperformancethancommercialpowders(as-receivedor ball-milled).Weobservedthat20hwerenecessaryfortheformationofMoSi2whereas100hwereneeded

fortheformationoftheCrSi2powder.Thebestbatteryperformancewasobtainedwiththesynthesized

CrSi2powderthathasatheoreticalcapacityvalueof469mAhg−1.Thispowderprovidedcapacitiesof

340,262,167,110,and58mAhg−1atC/12,C/6,C/2,C,and2C,respectively.Cyclingat60◦Cshowed

highercapacityvalues,butwithafasterfadeofthesevalues.

Crown Copyright © 2011 Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Mostcommerciallithium-ionbatteriesusegraphiticcarbonas theanodematerialdue toitslow cost,longcyclelife,andvery stablecapacity[1].However,thereversibleelectrochemical inter-calationoflithiumionsinitsstructureleadstotheintercalationof onelithiumpersixcarbons(LiC6)thatresultsincapacities theo-reticallylimitedtoonly372mAhg−1.Siliconhasbeenstudiedfor quiteawhileasanodematerial.Siliconisabundant,quite inexpen-sive,non-toxic,andprovidesaveryhightheoreticalcapacityover 3500mAhg−1(Si+3.75Li++3.75e−

↔SiLi3.75)[2].Howeverit suf-fersfromlargestructuralvolumechangesduringcharge/discharge cyclingofthebatteryreaching300–400%[1,3,4].Thisgivesriseto mechanicalstressesthatleadtocracksandeventual disintegra-tionoftheelectrodeandafailureofthebattery[5].Intermetallic compounds,suchassilicidesM–Si(withM:Mg[6–8],Mn[2,9], Mo[10],Fe[9,11],Ni[12],Nb,Ta, V,Ca,Cr[13,14],and Ti)[1]

werefirstreportedbyAnaniandHugginsasanodematerialsfor Li-ionbatteries[14],especiallyMg2Si[6]andCrSi2[14].Since,more workhave been performedon siliconand silicon-metalalloys; onthisregard,twointerestingreviewshaverecentlybeen pub-lishedonthesubjectbyParketal.[15]andLarcheretal.[2].The insituformationoftheinactivemetalcompoundactsasamatrix that mitigates the volume change. Mg2Si has an anti-fluorine structurethatwasshowntoaccommodateLi-insertionaccording

∗ Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+16139494184;fax:+16139900347.

E-mailaddress:Yaser.Abu-Lebdeh@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca(Y.Abu-Lebdeh).

to the following path: Mg2Si+2Li+2e→Li2MgSi+Mg, followed by reaction of Mg with lithium toform an MgLi alloy [14,16]. However, other groups reported the following reaction path-way [7,8]: Mg2Si+3Li+3e→2MgLi+SiLi. Initial capacities are typically usually high but the reversible capacity is quite low. It has also been reported that lithium could be inserted into the structure of CrSi2, but is limited by slow kinetics at room temperature[17].Nevertheless, usinga composite of CrSi2 and lithium,Weydanzetal.reportedinitialdischargecapacities rang-ingfrom650to800mAhg−1,dependingontheLi:CrSi

2ratioused

[17].

Wedecidedtoinvestigatethebatteryperformanceofpristine CrSi2(withoutlithiumadditive)atroomtemperature(R.T.)andat 60◦C.Wealsoreportonthebatterybehaviorofitstwincompound MoSi2asacomparison[10].Thesetwopristinesilicideshavenever beeninvestigated asanodematerialsfor Li-ionbatteries. Based onAnaniandHugginswork[14]weestimatedtheoretical capac-itiesof804mAhg−1 forMoSi

2 and580mAhg−1 forCrSi2.These values arein therange of capacities expectedfor futureanode materialsin cathode-limitedbatteries as calculated byAppleby etal.[4].

Hereinwe reportthe investigationofsynthesized and com-merciallyavailableCrSi2andMoSi2.Thepowdersweretestedas receivedandalsoball-milledviahighenergyball-milling(HEBM) at different times. In addition, a comparison with synthesized CrSi2andMoSi2powderspreparedbyHEBMwasalsoperformed. Lithiumbatteries (half-cells)wereassembled withthedifferent materials and tested galvanostatically at differentrates and by cyclicvoltammetry.

0378-7753/$–seefrontmatter.Crown Copyright © 2011 Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2011.11.047

270 F.M.Courteletal./JournalofPowerSources202 (2012) 269–275

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Chromiumsilicide(CrSi2,230mesh,99+%),molybdenum(Mo, 1–2m,>99.9%),andsilicon(Si,325mesh,99%)werepurchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Molybdenum silicide (MoSi2, 99.5%) and chromium(Cr,<10m,99.8%)werepurchased fromAlfaAesar. CarbongraphiteE-KS4andSuperScarbonwerepurchasedfrom LonzaG+T(Switzerland)andTimcal (Switzerland),respectively. Sodiumcarboxymethylcellulose(NaCMC,viscosity42.0mPas)was purchased from Calbiochem and used as a 5wt% solution dis-solvedindouble distilledH2O.Sodiumcarboxymethyl cellulose (NaCMC)wasusedasabinderinthisworkinsteadofconventional PVDFdue toitssuperiorperformance withsilicon-based anode materials.

2.2. Synthesis

CrSi2andMoSi2powderswerefirstusedasreceivedandthen ball-milledfor20husingHEBMtechnique.A50mLtungsten car-bidevial(8004,Spex)andthreetungstencarbidebeads(10.75g each,Spex)wereusedalongwithapowder/ballratioof1/3.2.CrSi2 andMoSi2 werealsosynthesizedviathesameHEBMtechnique usingthesamepowder/ballratio.Thesynthesiswasperformed usingMo,CrandSipowdersasstartingmaterialsmixedinaM/Si atomicratioof 1/2.Themixturewasball-milleduntiltheright phasewasobtained,whichtook100hforCrSi2and20hforMoSi2. HEBMwasperformedusingaSPEX8000ballmiller,andthevials weresealedunderargonatmospherebeforemilling.

2.3. Characterization

PowderX-raydiffractionwascarriedoutusingaBrukerAXSD8 diffractometerwithaCuK␣sourcewithastepsizeof0.03◦ and anacquisitiontimeof1sperstep.Thepatternswereanalyzedby theRietveldrefinementmethod[18]usingthesoftwareTOPAS4 fromBrukerAXS[19].Thecrystallitesizesweredeterminedusing thefundamentalparameterapproachmethoddevelopedbyCheary etal.[20].Powderswerealsocharacterizedbyscanningelectron microscopy(SEM) usinga JEOL 840A.Battery cycling was car-riedoutonhalf-cellsusing2325-typecoincellsassembledinan argon-filledglovebox. Capacitymeasurementswereperformed bygalvanostaticexperimentscarriedoutonamultichannelArbin batterycycler.Theworkingelectrodewasfirstcharged(lithiated) downto5mVversusLi/Li+atdifferentC-ratesandthendischarged (delithiated)upto2VversusLi/Li+.Thevaluesofthecell parame-ters,thecrystallitesizes,andthecompositionpercentagesaregiven withanerrorvaluebetweenbrackets.

Theworkingelectrodeswerepreparedasfollows:theactive materialwasmixedwith5wt% SuperScarbon,5wt% Graphite and10wt%binder.Theelectrode filmsweremadebyspreading ontoahighpuritycopperfoilcurrentcollector(cleanedusinga 2.5%HClsolutioninordertoremovethecopperoxidelayer)using anautomateddoctor-bladeandthendriedovernightat85◦C in aconvectionoven.Individualdiskelectrodes(Ø=12.5mm)were punchedout, dried at 80◦C under vacuumovernight and then pressedunderapressureof0.5metricton.Electrodesweremade of3–4mgofactivematerial.Alithiummetaldisk(Ø=16.5mm) wasusedasanegativeelectrode(counterelectrodeandreference electrode).70Lof a solutionof1MLiPF6 inethylene carbon-ate/dimethylcarbonate(EC:DMC,1:1,v/v)wasusedaselectrolyte andspreadoveradoublelayerofmicroporouspropylene separa-tors(Celgard3501,thickness=30m,Ø=2.1mm).Thecellswere assembledinanargon-filleddrygloveboxatroomtemperature.

3. Resultsanddiscussion

3.1. X-raydiffraction

XRD hasbeen performed on the MoSi2 and CrSi2 commer-cialpowders,as-receivedand ball-milledinordertofollowthe decreaseofthecrystallitesizes.X-raypatternswerealsorecorded duringtheHEBMstepsoftheMo–SiandCr–Simixtures.

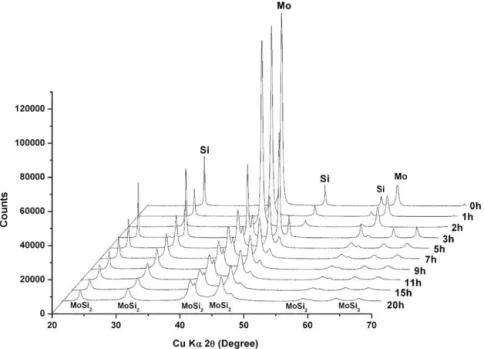

Fig.1showstheXRDprofilesofcommercialMoSi2asa func-tionof HEBM time. Using theRietveld refinementmethod,the composition(inwt%)oftheas-receivedcommercialMoSi2 pow-derwasof:93.3(1)%MoSi2,4.9(1)%Mo5Si3,and0.8(6)%Mo.The MoSi2 phase exhibits a tetragonal I4/mmm structure with cell parameterof:a=3.20508(3) ˚Aandc=7.84638(9) ˚A,anda crystal-litesizeof306(14)nmwascalculated.Thesecondarytetragonal

I4/mcmMo5Si3 phasehascellparameters ofa=9.6462(6) ˚A and c=4.9064(5) ˚A andcrystallitesizesof210(100)nm.After20hof HEBMadecreaseofMoSi2contentandanincreaseoftheMo5Si3 phase have been observed. The powder is then composed of 70.7(1)%MoSi2, 28.1(1)%Mo5Si3, and 1.2(4)% Mo.Asexpected, a decrease inthe crystallitesizesto 173(10)nmfor MoSi2 and 5(2)nm for Mo5Si3 hasbeen observed. Fig.2 shows theX-ray patterns of the Mo–Si mixture HEBM from 0hto 20h. Before theHEBM started, as expected,a mixture of elemental molyb-denum and silicon wasobserved. Afteronly 3h of HEBM, the tetragonalMoSi2 phasestartedappearing alongwiththe disap-pearanceoftheSipeaksandthedecreaseoftheMopeakintensity, asobservedbyMaetal.[10].After20hofHEBM,thein-house preparedpowderiscomposedof93.2%MoSi2(twodifferent crys-tallinestructures)and6.8%Mo.ThefirstMoSi2identifiedphaseis thetetragonalI4/mmmstructurethatrepresents71.4%,withcell parametersof:a=3.2032(2) ˚Aandc=7.8658(7) ˚A,andcrystallite sizesof13(18)nm.Thesecond identifiedMoSi2 structure hasa P6222spacegroup,represents21.8%andhascellparametersof:

a=4.704(6) ˚Aandc=6.094(4) ˚A,andcrystallitesizesof10(8)nm. Smallercrystallitesizesareobservedforthein-housesynthesized MoSi2comparedtothecommercialHEBMMoSi2powder.

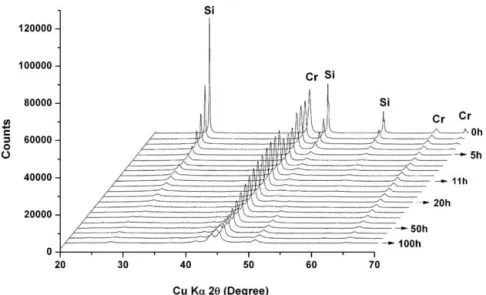

Fig.3showstheXRDprofilesofcommercialCrSi2asafunction ofball-millingtime.ByRietveldrefinement,thecalculated com-positionoftheas-receivedcommercialCrSi2powderwas99.75% CrSi2 and 0.25% CrSi. The CrSi2 phase exhibits a P6422 struc-turewithcellparametersof:a=4.42784(5) ˚Aandc=6.3726(1) ˚A, andusingthefundamentalparameterapproachmethodcrystallite sizesof187(63)nmwerecalculated.After20hofHEBM,theCrSi2 crystallitesizehasdecreasedto7(1)nmwithcellparametersof

a=4.4284(5) ˚Aandc=6.380(2) ˚A;thetwosecondaryphases,CrSi andSiwerenolongervisible.Thein-housepreparedCrSi2powder tookalongertimetopreparethantheMoSi2 powder.Thephase startedappearingafter20hofHEBM,along withthe disappear-anceofthechromiumphase.After100hofHEBM,thechromium phase isat a minimumlevel. Thepowder isthen composedof 65.1%CrSi2,27.2%Cr5Si3,and7.7%Cr.TheCrSi2powdershowed smallcrystallitesizeof9(3)nm,similarlyfortheCr5Si3 powder at9(4)nmFig.4.

3.2. Scanningelectronmicroscopy

Fig.5showstheSEMmicrographsofthethreeCrSi2powders andthreeMoSi2powders.AsshowninFig.5aandc,theas-received commercialCrSi2andMoSi2showsmoothparticlesrangingfrom 5to10minsize.After20hofHEBM, adecreaseinthe parti-clesizewasnoticedforbothpowders.AsshownbyFig.5bandd sizesnowrangeatandbelow5m.CrSi2powdermadeby100hof HEBMdirectlyfromaCr–Simixtureshowsasmallandan homo-geneoussizedistribution,around2mwithaggregatesizesupto

Fig.1. XRDpatternsofcommercialMoSi2duringtheHEBMsteps.

Fig.2.XRDpatternsoftheMo–SimixtureduringtheHEBMsteps.

6–7m.TheMoSi2powderpreparedthesamewaywith20hof HEBMshowsparticlesizesaround1m.

3.3. Batterycycling

Allsixpowdershavebeentestedasanodematerialsin half-cells using lithium metalas a counter and reference electrode. TheC-rate and theoretical capacities werecalculated usingthe workperformedbyAnani andHuggins[14] whoestimatedthe lithium storage capacities of several silicides,including molyb-denum andchromiumsilicides.Capacityvalues ofthedifferent molybdenum and chromium silicides indentified by XRD have been calculated using the formula reported in reference [21]: Cap. (mAhg−1)=(96,500×numberof Li+ exchanged)/(molecular weightofthesilicide×3.6).Thecapacityvalues,rangingfrom279 to804mAhg−1,aresummarizedinTable1.

Thetheoreticalcapacityvaluesofthesixinvestigatedpowders havebeencalculatedaccordingtothecompositionobtainedvia theRietveldrefinementmethodappliedtotheXRDpatterns.The capacityvaluessummarizedinTable2donottakeintoaccount a possibleamorphous silicon phase thatwas notdetectableby XRD.

Fig.6showstheperformanceandtheratecapabilityof com-mercialMoSi2,as-receivedandHEBMfor20h,andin-housemade MoSi2 electrodes. After20 cyclesat C/12, the previously men-tionedpowdersshowedcapacitiesof100,115and135mAhg−1, Table1

Theoreticalcapacityvaluesofthedifferentmolybdenumandchromiumsilicides.

Silicide MoSi2 Mo5Si3 CrSi2 CrSi Cr5Si3

Lithiumstored[14] 4.56 5.88 2.34 0.93 4.32

272 F.M.Courteletal./JournalofPowerSources202 (2012) 269–275

Table2

Compositionandtheoreticalcapacityvaluesofcommercial(as-receivedandHEBM)andin-housesynthesizedmolybdenumandchromiumsilicides.

Silicide MoSi2commercial

as-received MoSi2commercial 20hHEBM MoSi2in-house 20hHEBM CrSi2commercial as-received CrSi2commercial 20hHEBM CrSi2in-house 100hHEBM CompositionfromRietveldrefinement

(wt%)

93.3MoSi2 70.7MoSi2 93.2MoSi2 99.75CrSi2 93.53CrSi2 65.1CrSi2

4.9Mo5Si3 28.1NMo5Si3 6.8Mo 0.25CrSi 6.47Cr Cr5Si3

Mo 1.2Mo 7.7Cr

Capacity(mAhg−1) 764 647 749 579 542 469

respectively,whichislowerthangraphite(330mAhg−1atC/12). AccordingtoHuggins,theexpectedcapacitiesare764,647, and 749mAhg−1, respectively. The lower capacities could not be attributedtopoorelectronic conductivityas itis reported that MoSi2isagoodelectricalconductorof3.5×104Scm−1[22,23]but mostprobablytopoorionicconductivityasitisalsopossiblethat thelithiumdiffusioncoefficientisverylowatR.T.Another possi-bilityisthatMoSi2mightnotbeveryreactivetowardslithium,as pointedoutbyDahnetal.formostsilicides[9].Fig.6alsoreports theratecapabilityofthesethreeelectrodes,thatareobviouslyalso

verylow.Howeverthepowdermadein-houseprovidedthebest capacityvalues.

InordertoimprovethelithiummobilityinMoSi2,ahalf-cell madeofthein-housepreparedpowderhasbeencycledat60◦C. Itshowedahighfirstdischargecapacityof450mAhg−1 andan irreversiblecapacityof235mAhg−1,whichrepresentsabout65% ofthefirstdischargecapacity.After20cycles,theelectrode has acapacity ofonly75mAhg−1.AsreportedbyFleischaueretal., thecapacityfadeforsilicon-richsilicidescouldberelatedtothe increaseddegreeofLi15Si4crystallizationathighertemperatureas

Fig.3. XRDpatternsofcommercialCrSi2duringtheHEBMsteps.

Fig.5.SEMmicrographsof(a)as-receivedcommercialCrSi2,(b)commercialCrSi2after20hofHEBM,(c)synthesizedCrSi2,(d)as-receivedcommercialMoSi2,(e)commercial

MoSi2after20hofHEBM,and(f)synthesizedMoSi2.

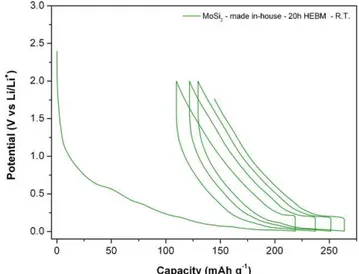

opposedtoamorphousLi15Si4whichismorereactive[24].Itcould alsobeduetothedegradationoftheelectrolyteandtheformation ofathickerSEIlayeratthesurfaceoftheparticles.Fig.7showsthe voltageprofileoftheMoSi2powderpreparedin-houseby20hof HEBM.Itshowsadischargethatstartsmostprobablywiththe for-mationofaSEIatabout1.25V.Aninsertionplateauisalsoobserved atlowpotentialatabout0.01V.Thedelithiationstartedwithashort plateauat0.2V,andthenaslope(straightline)between0.005V and2V.AccordingtoAnaniandHuggins,theadditionof molybde-numtothebinarysilicon–lithiumsystemproducesthreeadditional phasesintheternaryphasediagramMo–Si–Li:MoSi2,Mo5Si3,and Mo3Si.Asaconsequence,itgivesrisetotwoadditionalequilibria: MoSi2–Mo5Si3–SiLi3.25andMo5Si3–Mo3Si–SiLi4.4[14].Itis impor-tanttopointoutthatmolybdenumdoesnotformanalloywith lithium.Thereactionscorrespondingtotheseequilibriaareshown byEqs.(1)and(2):

20MoSi2+91Li++91e−↔4Mo5Si3+28SiLi3.25 (1) 15Mo5Si3+88Li++88e−↔25Mo3Si+20SiLi4.4 (2)

Fig.6.RatecapabilityMoSi2anodesmadefrom:as-receivedcommercialpowder

cycledatR.T.,commercialpowderball-milledfor20hcycledatR.T.,powdermade in-housevia100hofHEBMatR.T.andat60◦C.Batterieswerecycledbetween5mV

and2VversusLi/Li+atC/12,C/6,C/2,C,2CandbacktoC/12.

Chromiumisinthesamegroupasmolybdenumintheperiodic tableand sharessomephysicalandchemical properties,andits silicidecompoundsareofsimilarinterest.SimilartoMoSi2,the per-formanceofpristineCrSi2hasneverbeenreportedintheliterature, onlyWeydanzetal.reportedfirstdischargecapacitiesofa compos-iteofCrSi2andlithiumwhichvariedfrom650to800mAhg−1as afunctionoftheLi:CrSi2ratioused[17].Fig.8showsthe perfor-manceofdifferentCrSi2electrodematerials:theas-receivedand 20hball-milledcommercialpowdersandthein-housesynthesized powders.Theas-receivedpowderprovidesavery lowcapacity, around75mAhg−1.TheHEBM (20h)powdershowed enhance-ment in capacity with a first discharge of 330mAhg−1, which represents61%ofthetheoreticalcapacityandanirreversible capac-itybetweenthefirstandthesecondcycleofabout50mAhg−1(15% ofthefirstdischargecapacity).Thispowdershowedareversible capacityof225mAhg−1after20cyclesatC/12.

The in-house prepared CrSi2 powder showed better per-formance than the commercial one. When cycled at room temperature,areversiblecapacityof340mAhg−1wasobtainedfor thispowderafter20cyclesatC/12,whichisalmostasgoodasthe

Fig.7. Voltageprofileofthefirst4cyclesofMoSi2madein-houseby20hofHEBM

274 F.M.Courteletal./JournalofPowerSources202 (2012) 269–275

Fig.8.CyclingbehaviourofCrSi2anodesmadefrom:as-receivedcommercial

pow-dercycledatR.T.,commercialpowderball-milledfor20hcycledatR.T.,powder madein-housevia20hofHEBMatR.T.andat60◦

C.Batterieswerecycledbetween 5mVand2VversusLi/Li+atC/12.

reversiblecapacityofgraphiteforthesameC-rate(330mAhg−1). TheratecapabilityoftheCrSi2powderpreparedin-houseisshown inFig.9.Capacitiesof262,167,110,and58mAhg−1wereobtained atC/6,C/2,C,and2C,respectively.Whenthebatterywascycled backatC/12,theelectroderecovered94%ofitsprevious capac-ity(atC/12).Similartomolybdenum,chromiumdoesnotforman alloywithlithium,anditsadditiontothebinarysilicon–lithium systemproducesfouradditionalphasesintheternaryphase dia-gramCr–Si–Li:CrSi2,CrSi,Cr5Si3,andCr3Si,whichgaverisetothree additionalequilibria:CrSi2–CrSi–SiLi2.33,CrSi–Cr5Si3–SiLi2.33,and Cr5Si3–Cr3Si–SiLi3.25 [14].Eqs.(1)–(3)showthereactions corre-spondingtotheseequilibria:

3CrSi2+7Li++7e−↔3CrSi+3SiLi2.33 (3) 15CrSi+14Li+

+14e−

↔3Cr5Si3+6SiLi2.33 (4) 3Cr5Si3+13Li++13e−↔5Cr3Si+4SiLi3.25 (5) Weobservedthatchromiumsilicidepowdersshowedbetter per-formance than the molybdenum silicide powders. Contrary to MoSi2,CrSi2isnotaconductorbutap-typesemiconductorwith abandgaprangingfrom0.3to0.84eV[25]whichresultsinlower

Fig.9. RatecapabilityCrSi2anodesmadefrom:as-receivedcommercialpowder

cycledatR.T.,commercialpowderball-milledfor20hcycledatR.T.,powdermade in-housevia100hofHEBMatR.T.andat60◦C.Batterieswerecycledbetween5mV

and2VversusLi/Li+atC/12,C/6,C/2,C,2CandbacktoC/12.

Fig.10.Voltageprofileofthefirst4cyclesofCrSi2madein-houseby100hofHEBM

cycledatR.T.and60◦CatC/12.Batterieswerecycledbetween5mVand2Vversus

Li/Li+.

electricalconductivity.AccordingtoAnaniandHugginsstudy per-formedat400◦C, itis mostlyprobablethatlithiumdiffusionin CrSi2isquitelowatR.T.[17].So,inordertoimprovethelithium diffusion,ahalf-cellmadeofchromiumsilicidepreparedinhouse by100hofHEBMwascycledat60◦C.After20cyclesatC/12,this electrodeshowedacapacityof446mAhg−1,whichishigherthan thecapacityobtainedatR.T.TheratecapabilityillustratedbyFig.9, gavethefollowingperformance:382,315,263,and191mAhg−1at C/6,C/2,C,and2C,respectively.WhencycledbackatC/12,the bat-teryprovided360mAhg−1whichrepresentsabout81%ofcapacity recovery.However,arecoveryof94%wasobtainedwhenthe bat-terywascycledatR.T.,whichmeansthattheperformanceofthe batterydegradesfasterwhencycledat60◦C.AsforMoSi

2,thisis mostprobablyduetotheformationofathickerSEIthatbuildsup withcyclingathighertemperature,orduetotheincreaseddegree ofLi15Si4crystallizationat60◦CasopposedtoamorphousLi15Si4, asreportedbyFleischaueretal.[24].

Fig.10showsthevoltageprofileofchromiumsilicidepowder preparedin-houseafter100hofHEBMofSiandCrpowders.These batterieswerecycledatR.T.or60◦CatC/12between0.005Vand 2VversusLi/Li+.Thegeneralvoltageprofileisquitesimilartowhat wasobservedforMoSi2.ThebatterycycledatR.T.showsa shoul-deratabout0.5VthatcouldberelatedtotheformationoftheSEI, whereasthesameshoulderappearsatabout1.8Vforthebattery cycledat60◦C.Thepotentialthenreachedaplateauatabout0.04V atR.T.and0.17Vat60◦C.Theseplateauscorrespondtothe forma-tionofchromium-richsilicidesandtheformationofsilicon–lithium alloyssuchasSiLi3.25andSiLi2.33,accordingtoequilibriums(3)–(5). Weydanzetal.observedtheonsetofthelithiationatslightlylower voltageof300mVfortheLi–Cr–Sisystem[17].Thebatterycycledat R.T.showedafirstdischargecapacityof435mAhg−1,which repre-sents93%ofthetheoreticalcapacity.Afirstirreversiblecapacityof about50mAhg−1 (12%ofthefirstdischargecapacity)was mea-sured.The samematerial cycled at 60◦C showeda higher first dischargecapacityof870mAhg−1,whichis85%higherthanthe theoreticalcapacity thatwe calculated forthis powder.Soit is probablethattheextracapacityobtainedat60◦Ccorrespondsto theformationofathickerSEIonthesurfaceoftheCrSi2particles thatconsumesalargeamountofcharge.Thishighcapacitycame alongwithahighfirstirreversiblecapacityof285mAhg−1(33%of thefirstdischargecapacity).Thedelithiationofchromiumsilicide occursasaslope,almostastraightlinebetween0.005Vand2V forbothcyclingtemperatures.Aspreviouslymentioned,alarger irreversiblecapacity wasobservedfor thebattery dischargedat 60◦C.

4. Conclusions

Inthisstudywereportedtheinvestigationofmolybdenum sili-cideandchromiumsilicideasanodematerialsforLi-ionbatteries. Thein-housepreparedpowdersshowbetterperformancethanthe ball-milledcommercialMoSi2 andCrSi2 powders.AHEBM time of20hwasnecessaryfortheappearanceoftheMoSi2crystalline phasewhereasalongertimeof100hwasnecessaryforthe for-mationoftheCrSi2crystallinephase.Chromiumsilicidepowders showedbetterperformancethanmolybdenumsilicidepowders; morespecificallythein-housepreparedchromiumsilicidepowder providedacapacityof340mAhg−1atC/12.Highercycling temper-atureshowedarapiddecadeofthecapacityduetothedegradation oftheelectrode.

Acknowledgment

ThisworkwassupportedbyNaturalResourcesCanada’sOffice ofEnergyResearchandDevelopment.

References

[1]G.-A.Nazri,G.Pistoia,LithiumBatteries:ScienceandTechnology,Kluwer Aca-demicPublisher,Boston,Dordrecht,NewYork,London,2004.

[2]D.Larcher,S.Beattie,M.Morcrette,K.Edstrom,J.-C.Jumas,J.-M.Tarascon,J. Mater.Chem.17(2007)3759–3772.

[3]J.Li,R.B.Lewis,J.R.Dahn,Electrochem.Solid-StateLett.10(2007)A17–A20. [4] U.Kasavajjula,C.Wang,A.J.Appleby,J.PowerSources163(2007)1003–1039. [5]P.B.Balbuena,Y.Wang,Lithium-IonBatteries:Solid-ElectrolyteInterphase,

ImperialCollegePress,London,2004.

[6]A.Anani,R.A.Huggins,J.PowerSources38(1992)363–372. [7]J.Santos-Pe ˜na,T.Brousse,D.Schleich,Ionics6(2000)133–138.

[8]H. Kim, J. Choi, H.-J. Sohn, T. Kang, J. Electrochem. Soc. 146 (1999) 4401–4405.

[9]M.D.Fleischauer,J.M.Topple,J.R.Dahn,Electrochem.Solid-StateLett.8(2005) A137–A140.

[10]E.Ma,J.Pagán,G.Cranford,M.Atzmon,J.Mater.Res.8(1993)1836–1844. [11] H.-Y.Lee,S.-M.Lee,J.PowerSources112(2002)649–654.

[12]Y.-N.Zhou,W.-J.Li,H.-J.Chen,C.Liu,L.Zhang,Z.Fu,Electrochem.Commun.13 (2011)546–549.

[13]H.Wang,J.-C.Wu,Y.Shen,G.Li,Z.Zhang,G.Xing,D.Guo,D.Wang,Z.Dong,T. Wu,J.Am.Chem.Soc.132(2010)15875–15877.

[14]A.Anani,R.A.Huggins,J.PowerSources38(1992)351–362.

[15] C.-M.Park,J.-H.Kim,H.Kim,H.-J.Sohn,Chem.Soc.Rev.39(2010)3115–3141. [16]T.Moriga,K.Watanabe,D.Tsuji,S.Massaki,I.Nakabayashi,J.SolidStateChem.

153(2000)386–390.

[17] W.J.Weydanz,M.Wohlfahrt-Mehrens,R.A.Huggins,J.PowerSources81–82 (1999)237–242.

[18] H.Rietveld,ActaCrystallogr.22(1967)151–152.

[19]BrukerAXS,DIFFRACPlusTOPAS:TOPAS4.2UserManual,Karlsruhe,Germany, Bruker-AXSGmbH,2008.

[20]R.W.Cheary,A.Coelho,J.Appl.Crystallogr.25(1992)109–121. [21] R.S.Treptow,J.Chem.Educ.80(2003)1015–1020.

[22]S.Köbel,J.Plüschke,U.Vogt,T.J.Graule,Ceram.Int.30(2004)2105–2110. [23]Z.Guo,G.Blugan,T.Graule,M.Reece,J.Kuebler,J.Eur.Ceram.Soc.27(2007)

2153–2161.

[24]M.D.Fleischauer,R.Mar,J.R.Dahn,J.Electrochem.Soc.154(2007)A151–A155. [25]H.N.Zhu,K.Y.Gao,B.X.Liu,J.Phys.D:Appl.Phys.33(2000)L49.