People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research

!" 8 ي! 1945 / *+!, UNIVERSITY OF 8 MAI 1945/ GUELMA

789 باد=ا ت!?8+او FACULTY OF LETTERS AND LANGUAGES

BC, باد=ا و ا DE78FGHا ?8+ LANGUAGE

DEPARTMENT OF LETTRES AND ENGLISH

Option: Language and Culture

A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of Letters and English Language in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in Language and Culture.

Candidate Supervisor

Ms. BOUTOBBA Lilia Mrs. HIMOURA Kawther BOARD OF EXAMINERS

Chairwoman: Mrs. ABDAOUI Fatima (MAA) University of 8 Mai 1945-Guelma Supervisor: Mrs. HIMOURA Kawther (MAB) University of 8 Mai 1945-Guelma Examiner: Mrs. BENYOUNES Djahida (MAA) University of 8 Mai 1945-Guelma

2019

Students’ Problems with Cohesion and Coherence in EFL Essay

Writing

The Case of Master One Students, Department o

f

English,

University of 08 Mai 1945-Guelma

Dedication

Before all, I thank ALLAH

With ALLAH’s help, I have achieved this modest work

I dedicate this work to my parents who encouraged me in accomplishing this research To my precious mother Fatiha for her help, love, patience, and moral assistance throughout

my whole studies and life

To my dear father Mohamed for his help, care, and assistance To my dear husband Amrane Mohamed and his family To my dear sisters Amel and Amira and to my dearest brother Raouf

To all my lovely nieces To my best friend Rania

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my special appreciation and sincere gratitude to my supervisor Mrs. HIMOURA Kawther for her great help, guidance, and support throughout the

conduction of the research.

I would like to express my respect and gratitude to the jury members Mrs.

BENYOUNES Djahida and Mrs. ABDAOUI Fatima who devoted their precious time and accepted to review and evaluate my research.

A special thanks goes to all the advice of teachers who encouraged and assisted me to fulfill this research.

I would like also to thank Master one students who helped me and participated in this study.

Abstract

The current study attempts to investigate students’ problems with cohesion and coherence in English as foreign language essay writing. This research aims at exploring students’ attitudes and perceptions concerning the issues and struggles encountered when using cohesion and coherence in writing EFL essays. The present research adopts the descriptive method, which is manifested through a questionnaire and an analysis of students’ essays. The sample of this research was chosen randomly from Master one students at the Department of English, University of 8 Mai 1945, Guelma. Sixty (60) students participated in answering the questionnaire and other fifty (50) students participated in writing the essays. The derived findings reveal that Master one students encounter serious problems with cohesion and coherence when writing EFL essays. Consequently, the necessity of including cohesion and coherence lessons as well as providing opportunities for students to practice to write EFL essays through the use of cohesive devices and coherence in all the modules should be taken into serious consideration.

List of Abbreviations

EFL: English as a Foreign Language FL: Foreign Language

L1: First Language

List of Tables

Table 1.1. Basic Conjunction Relationship...21

Table 1.2. Types of Cohesion...25

Table 2.1. Narrowing the Topic Assigned by the Teacher...43

Table 2.2. Transition Signals “Additional Idea”...50

Table 2.3. Transition Signals “Opposite Idea”...51

Table 2.4. Unique Characteristics of Essays...54

Table 3.1. Student’s Age...58

Table 3.2. Student’s Gender...58

Table 3.3. Years of Studying English...59

Table 3.4. Student’s Level of Writing Proficiency...59

Table 3.5. Student’s English Writing Outside the Classroom...60

Table 3.6. Student’s Essay Writing Inside the Classroom...61

Table 3.7. How Difficult or Easy it is to Write an Essay...62

Table 3.8. The Time Allocated for Students to Write Essays...63

Table 3.9. The Topic of the Essay...64

Table 3.10. The Types of Essays...64

Table 3.11. The Outline of the Essay...65

Table 3.12. Student’s Consideration When Writing an Essay...66

Table 3.13. Students’ Follow of the Steps of the Writing Process...68

Table 3.14. Student’s Consideration of the Steps of an Essay...69

Table 3.15. Student’s Organization of Ideas...70

Table 3.16. The Problems Faced when Writing EFL Essays...72

Table 3.18. The Type of Lessons Received About Cohesion and Coherence...74

Table 3.19. Student’s Knowledge of the Difference between Cohesion and Coherence...75

Table 3.20. The appropriate Answer...76

Table 3.21. Problems Faced with Cohesion and Coherence...78

Table 3.22. The Frequency of Using Cohesive Devices...79

Table 3.23. Students’ Problems with Cohesive Devices...80

Table 3.24. The Characteristics of a Cohesive Text...81

Table 3.25. The Characteristics of a Coherent Text...81

Table 3.26. Ideas Organization...82

Table 3.27. The Appropriate Answer...82

Table 3.28. Teacher’s Feedback...83

Table 3.32. The Mistakes Found in Students’ Essays...83

Table 3.33. The Frequency of Students’ Mistakes with Cohesion and Coherence...86

Table 3.34. The Arithmetic Mean of the Correct or the Wrong Use of Cohesion and Coherence in Students’ Essays...100

List of Figures

Figure 1.1. The Process Wheel...10

Figure 1.2. Essay Outlining ...11

Figure 1.3. The Three Parts of an Essay...15

Figure 2.1. Types of Cohesion in English by Williams (1983)...17

Figure 2.2. Types of References...37

Figure 2.3. Types of Demonstrative Reference...44

Contents DEDICATION...i ACKNOWLEDGMENT...ii ABSTRACT...iii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS...iv LIST OF TABLES...v LIST OF FIGURES...vii CONTENTS...viii GENERAL INTRODUCTION...1

1. Statement of the Problem………...….2

2. Aims of the Study...3

3. Research Questions...3

4. Research Hypothesis...4

5. Research Methodology and Design...3

5.1 Research Method...4

5.2 Population of the Study...4

5.3 Data Gathering Tools...5

6. Structure of the Dissertation...5

CHAPTER ONE: COHESION AND COHERENCE Introduction...6

1.1. Discourse Anaalysis (DA)...6

1.2. Text and texture...7

1.2.1. Text...7

1.3. Cohesion...8

1.4. Types of cohesion...9

1.4.1 Grammatical cohesion...11

1.4.1.1. Reference...12

1.4.1.1.1.Endophoric (Textual) Reference...12

1. Anaphoric Reference...12

2. Cataphoric Reference...13

1.4.1.1.2. Exophoric (Situational) Reference...13

1.4.1.1.2. Sub-Types of Referential Cohesion...14

1. Personal Reference...14 2. Demonstrative Reference...15 3. Comparative Reference...16 A. General Comparison...16 B. Particular Comparison...16 1.4.1.2. Substitution...17 A. Nominal Substitution...18 B. Verbal Substitution...18 C. Causal Substitution...18 2.4.1.3. Ellipsis...18 1. Nominal Ellipsis...20 2. Verbal Ellipsis...20 3. Causal Ellipsis...20 1.4.1.4. Conjunction...20 1. Additive Conjunction...21 2. Adversative Conjunction...21

3. Causal Conjunction...22 4. Temporal Conjunction...22 1.4.2. Lexical Cohesion...22 1.4.2.1. Reiteration...22 1. Repetition...23 2. Synonymy...23 3. Near Synonymy...23 4. Superordinate...24 1.4.2.2. Collocations...24 1.5. Coherence...25 1.6. Types of meaning...27

1.6.1. Conceptual/ Logical Meaning...27

1.6.2. Connotative Meaning...28 1.6.3. Social Meaning...28 1.6.4. Affective Meaning...29 1.6.5. Reflected Meaning...29 1.6.6. Collocative Meaning...29 1.6.7. Thematic Meaning...30

1.7. Context and Meaning...30

1.8. The Relationship Between Cohesion and Coherence...31

1.9. Cohesion and Coherence: Independent but interrelated...32

Conclusion...33

CHAPTER TWO: EFL ESSAY WRITING Introduction...34

2.1.1. Definition of a Foreign Language (FL)...34

2.1.2. English as a Foreign Language (EFL)...34

2.1.3. The Writing Skill...35

2.2. The Writing Process...35

2.2.1. Prewriting...35

2.2.2. Drafting...36

2.2.3. Revising...36

2.2.4. Editing...36

2.2.5. Publishing/ Final Version...37

2.3. The Importance of EFL Writing...37

2.4. Sources Affecting Poor EFL Writing...38

2.4.1. Grammar Errors...39

2.4.2. Vocabulary Errors...40

2.4.3. Punctuation Errors...40

2.4.4. Spelling Mistakes...40

2.5. The Influence of First Language on EFL Learner’s Writing...41

2.6. Definition of an Essay...41

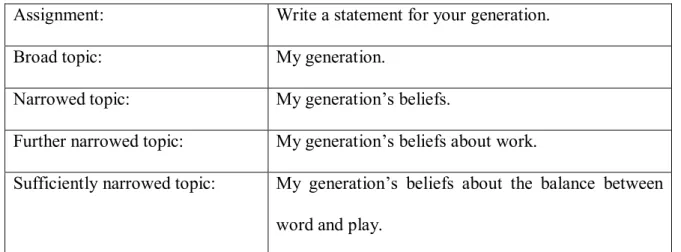

2.7 Choosing the Topic of the Essay...42

1.7.1. Topics Selected by Students...42

1.7.2. Topics Assigned by Teacher...43

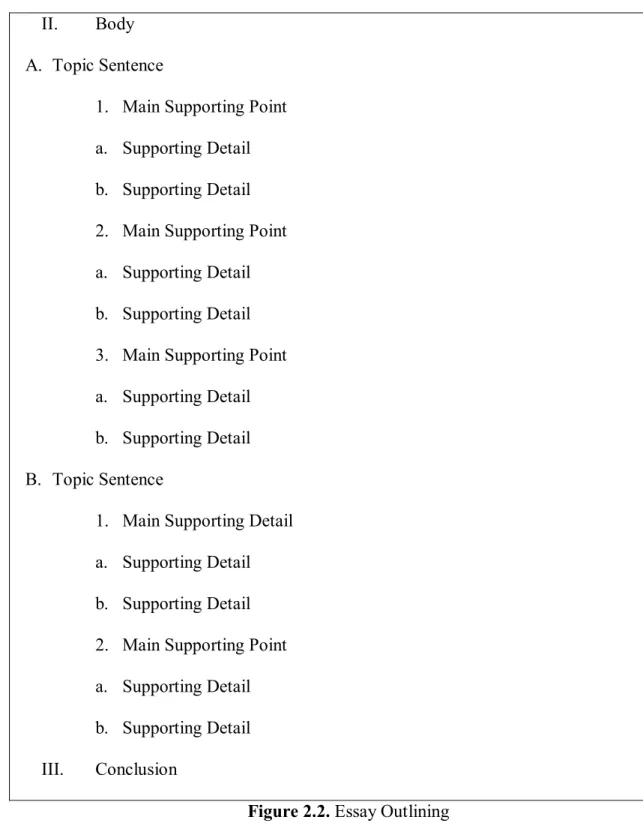

2.8. The Outline of the Essay...43

2.8.1. The Importance of an Outline...44

2.9. Components of an Essay...45

2.9.1 The Introduction...46

2. Characteristics of a Strong Thesis Statement...47

2.9.2. The Body...48

2.9.2.1. Parts of the Body Paragraph...48

1. The Topic Sentence...49

2. The Supporting Sentence (Details/ Illustrations/ Explanations)...49

3. The Concluding Sentence...49

4. Transitions...50

A. Transition signals: Additional Idea...50

B. Transition signals: Opposite Idea...50

2.9.3. The Conclusion...51

2.10. Types of Essays...52

2.10.1. Narrative: Telling a Story...52

2.10.2. Descriptive: Painting a Picture...52

2.10.3. Persuasive: Convince Me If You Can...53

2.10.4. Expository: It Is All About Facts...53

2.10.5. Characteristics of Essays...54

Conclusion...55

CHAPTER THREE: Field Investigation Introduction...56

3.1 Student’s Questionnaire...56

3.1.1. Population of the Study...56

3.1.2. Description of Students’ Questionnaire...56

3.1.3. Administration of Students’ Questionnaire...57

3.1.4. Data Analysis and Interpretation...58

3.1.4.2. Discussion of Results from the Students’ Questionnaire...82

Conclusion...85

3.2. Students' Essays Analysis...85

Introduction ...85

3.2.4 Data Analysis and Interpretation...86

3.2.4.1 Analysis of Findings from the Students’ Essays...86

3.2.4.2 Discussion of Results from the Students’ Essays...90

A. Cohesion...95

B. Coherence...97

Conclusion...102

GENERAL CONCLUSION...104

3.3. Pedagogical implications...105

3.3.1. Implications for Teachers...105

3.3.2. Implications for Students...105

3.4. Limitations of the Study...113 References

Appendix 1: Students’ Questionnaire Appendix 2. Students’ Essays (A) Appendix 3. Students’ Essays (B) ]^8

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

Writing is a fundamental part of the life of every student. At the university, students are usually asked to write different pieces of writing from the simplest to the most complex ones. They are usually asked to write paragraphs, different types of essays, and research papers. This increase in the variety of papers is mainly due to the importance that writing holds for students in their lives both during and after their education. In contrast to the ground reality, essay writing might seem like a trivial task that can be easily performed by anyone having the least basic skills in writing. Still, when one encounters the process of essay writing, these preconceived notions and assumptions would undoubtedly come to an end. This particularly happens when writing in EFL where students may face many challenges. However, the overall essay writing process includes ups and downs which tend to frustrate students, and that is why it has become crucial to improving it since it is an important skill that students need to learn and will need for the future. Moreover, many students believe that the essay writing process is the most difficult subject among other language skills because it does not only convey messages, or express feelings, it is rather an inclusive skill for language production.

The teachers have delineated various problems in the essay writing of EFL learners. They agreed that they have difficulties in grammar and syntax, and lack enough knowledge of appropriate vocabulary. They also make mistakes in subject-verb agreement, pronouns, prepositions, articles, tenses, and basic sentence structures. In addition to the lack of ideas which affects students’ writing, organized writing is also a challenge to learners as their writing lacks cohesion, coherence, consolidation of knowledge, and the use of formal transitional and cohesive devices.

As one of the FL skills, writing is really difficult. The difficulty stems from generating, organizing, and transmitting ideas into a well-constructed and comprehensible

text. A lot of learners have problems in the EFL writing classroom context, and this is often seen in their meaningless sentences. In order to produce a coherent and cohesive text, EFL learners should keep in mind that readers will not be able to follow their ideas unless they signal the connection between the previous and the coming ideas through contextual clues. In this context, Master one students at the Department of English, University of 8 Mai 1945, Guelma, encounter many problems and difficulties with cohesion and coherence when writing essays.

Cohesion and coherence are two vital elements in producing good writing. They are two terms used in discourse analysis and text linguistics to describe the properties of written texts. Cohesion refers to sentences’ connection at the sentence level, while coherence refers to sentences’ connection at the idea level. Cohesion and coherence are two different things. We can say that the text is cohesive if its elements are linked together, and we can say that the text is coherent only if it makes sense. However, the text may be cohesive (linked together), but incoherent (meaningless). Cohesion refers to the connectivity of sentences in the text, but coherence refers to how easy it is to understand the meaning. Moreover, cohesion is based on grammatical relationships, whereas coherence is based on semantic ones.

1. Statement of the Problem

Most of the students at the Department of English, University of 8 Mai 1945, Guelma face problems with cohesion and coherence in their EFL essay writing. Even though students have received lectures and courses on cohesion and coherence throughout their studies at the university; still, they encounter serious difficulties when they are asked to formulate an EFL essay composition. Thus, when reading their written pieces, it is a hard task to retrieve the precise intended meaning. These problems can be the result of the lack of concentration while writing, the short period of time, the absence of awareness of the use of cohesive and coherent devices, and the lack of practice. It can also be due to the fact that cohesive devices are often

absent, misused, or overused by learners in their attempt to rectify their writing production. These practical problems lead to the purpose of this study, which is to investigate students’ problems with cohesion and coherence in EFL essay writing. Therefore, it is crucial that learners should be aware of and competent in the correct use of cohesive devices as well as coherence. As a consequence, this would help in making the sentences and ideas of the essay linked together to be more cohesive and coherent, hence, developing their writing skill.

2. Aims of the Study

The aims of this research are:

1. To identify the problems that EFL learners encounter when writing essays.

2. To investigate the difficulties preventing students from using coherent and cohesive devices correctly.

3. To raise students’ awareness of the importance of cohesion and coherence. 3. Research Questions

1. What are the reasons of poor writing quality for EFL students? 2. What are the types of mistakes found in EFL students’ writing? 3. Why do students lack awareness of cohesion and coherence? 4. What are students’ attitudes towards cohesion and coherence? 4. Research Hypothesis

Cohesion and coherence are the two fundamental compositions of any effective EFL essay. The absence of the cohesive and coherent devices in an essay would lead to a poor meaningless piece of writing. Besides, students would not be able to increase their self-reliance, self-direction, and improvement in their academic achievement. So, we hypothesize that:

H1: If EFL students overcome cohesion and coherence problems, their essay writing would

5. Research Methodology and Design 5.1. Research Method

The present research is conducted through a descriptive method. It is conducted via a questionnaire and essays analysis. The study aims at testing the research hypothesis by analysing students’ problems and errors produced in EFL essays, and a questionnaire investigating students’ attitudes towards the use of cohesion and coherence in EFL essay writing and their importance. This method would allow for the confirmation or the rejection of the research hypothesis.

5.2. Population of the Study

The population of the study is Master one students at the Department of English, University of 8 Mai 1945, Guelma. The sample is composed of (110) students who were chosen randomly. The choice of this sample was motivated by two reasons. The first reason is that they have been studying English as the main language for four years. Therefore, their writing performance is supposed to be at a higher level. The second reason is that they satisfy the condition of the study since they have been exposed to the written production of many types of essays and research papers as well as being on the verge of graduation. Moreover, fifty (60) students of Master one are asked to write an essay on a particular topic, and the number to whom the questionnaire is distributed is sixty (60) students.

5.3. Data Gathering Tools

This research is carried out by means of a diagnostic test that is introduced to the participants; it involves writing an essay. The goal of this diagnostic test is to identify students' problems with cohesion and coherence in EFL essay writing. In addition, to prove or disapprove the research hypothesis, the student’s questionnaire provides valuable information about the students’ views and perceptions concerning the errors they commit, the causes of these errors, their capability to use cohesive and coherent devices accurately, and their ability

to enhance their writing. The output of the questionnaire, as well as the essays, are analyzed in search of problems in the field of interest.

6. Structure of the Dissertation

The dissertation is divided into three chapters. The first chapter is entitled “EFL Essay Writing”; it explores the definitions of the writing skill and the writing process, and essays. It also discusses the components of the essay, the topic of the essay, the thesis statement, the structure of the essay, as well as some of its types and their characteristics. In addition to the factors which affect students writing, the causes of affecting poor EFL writing is also discussed. The second chapter is entitled “Cohesion and Coherence”. It comprises definitions of cohesion and coherence, their components and types, and the relationship between them. The third chapter is entitled “Field Investigation”. It discusses the methodology, describes the research design, the data collection, and the interpretation of the findings. It also includes a description of EFL students’ questionnaires and written essays, their administration, and the analysis of the errors derived from both of them. Later, it interprets the results according to research questions and hypothesis. Finally, in the "General Conclusion", there are some pedagogical implications for both teachers and students as well as the limitations of the study.

CHAPTER ONE Cohesion and Coherence Introduction

Any written or spoken piece of language has certain rules to be followed in order to convey its producer’s main message properly. One of the main rules is cohesion; the major function of cohesion is text formation. This chapter discusses discourse, text and texture, the types of cohesion, and their main components in details. Moreover, it also discusses the concept of cohesion, the seven types of meaning, context and meaning, cohesion and coherence, and their role in communicating messages in the text, as well as the various relationships between cohesion and coherence. Cohesion and coherence serve at making sense to language in the text or discourse analysis. They have a major role in both the interpretation of the message and the negotiation of meaning in discourse. Hence, good academic writing demands an appropriate set of cohesive ties and coherent features so as that to create a comprehensible text.

1.1. Discourse Analysis (DA):

Following the Chomskian theory of Transformational Generative Grammar, linguists used to pay more attention to the analysis of sentence in isolation. They were concerned much more with the level of structure. Therefore, it is a pure syntactic view which neglected the meaning and focused on the form. According to Cook (1989), Zellig Harris has introduced a paper with the title “Discourse Analysis”. Hence, the term “Discourse Analysis” was introduced for the first time.

McCarthy (1991), states that discourse analysis is "concerned with the study of the relationship between language and contexts in which it is used” (p. 5). Furthermore, he suggests that because of Harris’s theory, linguists’ attention has shifted to the analysis of discourse rather than the analysis of a sentence in isolation. In other words, this new approach

motivated linguists to shift to the analysis of language as a combination of sentences which form the text, rather than isolated sentences. In addition, he adds: “Discourse analysts study language in use: written texts of all kinds, and spoken data, from conversation to highly institutionalized forms of talk”. Moreover, language requires unity and meaning in order to serve a communicative function; it is not just a set of followed rules for achieving the surface structure (p. 5).

1.2. Text and Texture: 1.2.1. Text:

Halliday and Hasan (1976) state, “text is used in linguistics to refer to any passage, spoken or written, of whatever length, that form a unified whole” (p. 1). Moreover, the text is not a grammatical unit like a sentence or a clause; it is something bigger. It is “a unit of language in use” that is not defined by its size. Text is best seen as a semantic unit of meaning, not of form (pp. 1-2).

Halliday and Hasan hold the view that in order to know whether a set of sentences constitutes a text or not depends on the cohesive relationships which exist between the sentences, hence, create texture (as cited in Brown and Yule, 1983, p. 191).

1.2.2. Texture:

Halliday and Hasan (1976) declare: “A text has texture, and this is what distinguishes it from something that is not a text. It derives this texture from the fact that it functions as a unity with respect to its environment”. The texture is the property that distinguishes a text from any other thing that is not a text. Without texture, each sentence may have different meaning and context, thus, the text would be a mere group of words set together randomly. The texture is otherwise referred to as textuality; it is also defined as what makes any length of text meaningful and coherent (p. 2). Moreover, any passage in English that is composed of more than one sentence is considered a text. Indeed, certain linguistic features would be

present to give the text texture and to contribute to its total unity. Halliday and Hasan provide an example for this:

-“if we find the following instructions in the cooking book; Wash and core six cooking apples. Put them into a fireproof dish”

As a consequence, ‘them’, in the second sentence refers to ‘six cooking apples’ in the first sentence. Thus, the anaphoric function of ‘them’ provides cohesion to the two sentences. The two sentences together constitute a text and can be interpreted as a whole; it is the texture which makes the two sentences a text (p. 2).

1.3. Cohesion:

Halliday and Hasan (1976) state, “The concept of cohesion is a semantic one; it refers to relations of meaning that exist within the texts, and that defines it as a text” (p. 4). In other words, cohesion occurs when the interpretation of certain elements in the text depends on each other. The relation of cohesion is created when both, the presupposing, and the presupposed are integrated into the text. Therefore, because the one presupposes the other, it cannot be successfully decoded only by recourse to it.

Brown and Yule (1983) point out that cohesion is about the lexical and grammatical linguistic mechanisms which internally link between both: the parts of the texts and the text and its context. They serve as signals that are available to the writer but not necessarily used by him. They add that they guide the reader towards interpreting the intended discourse (p. 191).

Baker (1992) defines the function of cohesion as the network of lexical and grammatical relations, which brings different parts of the text together. These relations and ties help in the creation and organization of the text by requiring the reader to interpret words and expression by reference to those in the surrounding context. Moreover, she adds:

“Cohesion is a surface relation; it connects together the actual words and expressions that we can see or hear” (p. 180).

Kennedy (2003) argues, “Texts are said to display cohesion when different parts of the text are linked to each other through particular lexical and grammatical features or relationships to give unity to the text” (p. 321).

1.4. Types of Cohesion:

Halliday and Hasan (1976) recognize five types of cohesion: reference, substitution, ellipsis, conjunction. The first four types belong to the category of grammatical cohesion, while the fifth and last type is lexical cohesion (pp. 75-84).

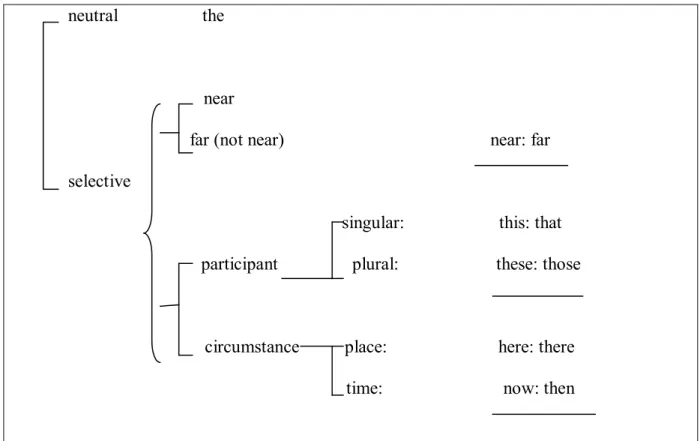

Williams (1983) summarizes the various types of cohesive relations in texts based on the work of Halliday and Hasan (1976) (as cited in kennedy, 2003, p. 322). They are displayed in the following figure:

collocation

lexical

repetition reitiration synonymy

cohesive ties superordination

general noun

(pronominal) exophoric reference (demonstrative) anaphoric (comparative) cataphoric substitution nominal grammatical verbal causal ellipsis additive contrastive amplifying exemplifying causal

logical connectives alternative explanatory excluding temporal summary Figure 1.1. Types of Cohesion in English by Williams (1983)

1.4.1. Lexical cohesion:

Generally, cohesion is achieved through several kinds of grammatical processes. These processes include:

1.4.1.1. Reference:

Halliday and Hasan (1976) claim that reference is a systemic relation; it is the act of indicating something by using certain linguistic elements. In addition, cohesive reference can point back to previously mentioned items, to forthcoming items, and outside the text (Kennedy, 2003, p. 224).

Yule (1996) defines reference as “an act in which a speaker, or writer, uses linguistic forms to enable a listener, or reader, to identify something”. The reference refers to those elements in any linguistic or situational texts which allow the listener or the reader to interpret the intention of the writer or speaker through referencing to another element in the same discourse (p. 17).

Reference:

(Situational) (Textual)

exophora endophora

(to preceding text) (to following text) anaphora cataphora

Figure 1.2. Types of References

Moreover, there are two types of reference that Halliday and Hasan (1976) describe: 1.4.1.1.1. Endophoric (Textual) Reference:

They are those cohesive relations which take place within the text so as that the meaning is interpreted through referring to the text. However, reference items come in two forms in the text: cataphoric or anaphoric. Moreover, Brown and Yule (1983) argue: “where their interpretation lies within a text they are called Endophoric relations" (p. 192).

According to Halliday and Hasan (1976): “Endophoric reference as the norm; not implying by this that it is the logical prior form of the reference relation, but merely that it is the form of it which plays a part in cohesion” (p.37). Moreover, when the reference indicates within the text, interpreting the meaning of a certain reference requires looking elsewhere in the text. It can either be anaphoric, i.e. indicating backward to a referent that has already been stated, or cataphoric, i.e. indicating forward to a referent that has not been produced yet. They are explained as the following:

1. Anaphoric Reference:

Nunan (1993) claims, “Anaphoric reference points the reader or listener ‘backward’ to a previously mentioned entity, process or state of affairs” (p.22). In addition, Brown and Yule (1983) add: “anaphoric reference is looking back in the text for their interpretation” (p.192). Halliday and Hasan (1976) also add that anaphora “provides a link with a preceding portion of the text” (p.51). By these definitions, they all mean that anaphoric reference is any reference that “points backward” to previously mentioned information or referring back to the item which has been previously identified in the text.

McCarthy (1991) provides an example which clearly exemplifies this type of reference: “And the living room was a very small room with two windows that wouldn't open and things like that. And it looked nice. It had a beautiful brick wall”. It is clear through this example that ‘it’ refers backward to ‘the living room’ (p. 38).

2. Cataphoric Reference:

Concerning this type of reference, McCarthy (1991) argues, “Cataphoric reference is the reverse of anaphoric reference and is relatively straightforward” (p. 42). It means referring to an item which has already been stated before it is identified. In addition, Nunan (1993) states, “cataphoric reference points the reader or listener forward – it draws us further into the text in order to identify the elements to which the reference items refer” (p. 22). Furthermore, cataphoric reference is also defined by Halliday and Hasan (1976), as to look forward in the text to identify the elements that the reference items refer to.

In addition, Brown and Yule (1983), define cataphora as “looking forward in the text for their interpretation” (p.192). That is to say, cataphora is that reference, which “points forward” to the data that will be presented later in the text. Moreover, Yule (1996) provides an example for this type of reference: “I turned the corner and almost stepped on it. There was a large snake in the middle of the path” (p. 23). This example clearly demonstrates that ‘it’ refers forward to the noun phrase ‘a large snake’.

1.4.1.1.2. Exophoric (Situational) Reference:

Halliday and Hasan (1976), comment: “Exphora is not simply a synonym for referential meaning”. Exophoric items indicate that reference should be made for the situation’s context; they do not name anything (p. 33).

Brown and Yule (1983) say, “Where their interpretation lies outside the text in the context of a situation, the relationship is said to be an exophoric relationship” (p. 192). Moreover, the exophoric reference refers to those cohesive relations which take place beyond the boundaries of texts. Therefore, the meaning can only be interpreted through reference to the context (p. 192- 193). That is to say, unless the listener refers back to the context of the discourse, he cannot interpret the meaning. Furthermore, they also see that “exophoric

co-reference instructs the hearer to look outside the text to identify what is being referred to” An example of this type of reference would be: “look at that” (p. 199).

McCarthy (1991) states, "Exophoric reference directs the receiver out of the text and into an assumed shared world" (p. 41). Hence, different aspects shared between the sender and the receiver should be given in order to interpret the meaning. An example of this type of reference would be: “The government is to blame for unemployment”. In this example, we can notice that the shared world between the speaker and the listener is a necessary part in order to know which ‘government’ exactly (p. 39). He adds, “references to assumed, shared worlds outside of the text are exophoric” (p. 35).

Halliday and Hasan (1976) argue,

Exophoric reference contributes to the CREATION of text, in that it links the language with the context of situation; but it does not contribute to the INTEGRATION of the passage with another so that the two together form part of the same text. Hence, it does not contribute directly to cohesion. (p. 37).

1.4.1.1.3. Sub-Types of Referential Cohesion:

According to Halliday and Hasan (1976), referential cohesion is divided into three sub-types: personal, demonstrative, and comparative reference.

1. Personal Reference:

It is the linguistic element that is used as a referring device. It is defined by Halliday and Hasan (1976) as “reference by means of function in the speech situation, through the category of person” (p. 37). As explained by Nunan (1993), the items of personal reference are expressed through pronouns. They can be personal pronouns like (I, you, he, she, it, we, they), possessive pronouns like (mine, yours, hers, etc), and possessive determiners like (me, your, his, her, etc).

2. Demonstrative Reference:

Nunan (1993) mentions, “demonstrative reference is expressed through determiners and adverbs. These items can represent a single word or phrase, or much longer chunks of text– ranging across several paragraphs or even several pages” (p.23).

Halliday and Hasan (1976), define demonstrative reference as: “reference by means of location on a scale of proximity” (p. 37). It refers to using demonstrative determiners to refer to an item. Moreover, this type of reference is reached through using both near and far proximity determiners (this, these, that, those, etc). It is also attained through using both adverbial demonstratives of place (here, there, around, etc), and adverbials of time (then, after, before, etc). The aforementioned types are summarized in the following figure:

neutral the

near

far (not near) near: far selective

singular: this: that participant plural: these: those

circumstance place: here: there time: now: then

Figure 2.3. Types of Demonstrative Reference (Retrieved from Halliday and Hasan 1976, p. 57)

3. Comparative Reference:

According to Halliday and Hasan (1976), comparative reference is “indirect reference by means of identity or similarity” (p. 37). In other words, it is an item in linguistics used to accomplish the function of the comparison. Besides, they state that the comparative reference is classified into two types: general and particular.

A. General Comparison:

This type of reference includes words and expressions that are used to express likeness and differences between items. The likeness is expressed via using adjectives such as (equal, same, identical, etc), and adverbs like (similarly, likewise, etc). Whereas, the difference is expressed via using adjectives such as (other, different, otherwise, etc) (p. 77).

B. Particular Comparison:

This type of reference is not about expressing likeness, or differences between items, rather, it is about the property of quantity and quality. It is achieved through the use of adjectives and adverbs “not of special class, but ordinary adjectives in some comparative form” (p. 77). The adjectives function either as Numerative or Epithet such as (more, fewer, further, less, etc). Whereas, the adverbs function either as Adjunct in the clause or as Submodifier such as (better, such in, more...than, etc) (p. 77). These types are summarized in the following figure:

identity same, equal, identical, identically general similarity such, similar, so, similarly, likewise (deictic) difference other, different, else, differently, compar- otherwise

ison

numerative more, fewer, less, further, particular additional; so- as- equally- (non-deictic) + quantifier, eg: so, many

epithet comparative adjectives and adverbs, eg: better: so- as- more- less- equally- +comparative

adjectives and adverbs, eg: equally good

Figure 2.4. Types of Comparative Reference (Retrieved from Halliday and Hasan, 1976, p. 76) 1.4.1.2. Substitution:

Tajeddin and Rahimi (2017), state “substitution is the action of replacing a word or words by another word or group of words” (p. 3).

Jabeen, Mehmood, and Iqbal (2013), state “This is the replacement of one item by another. It is a relation in the wording rather than in the meaning. This implies that as a general rule, the substitute item has some structural function as that for which it substitutes” (p. 125).

According to Halliday and Hasan (1976), substitution is often used to avoid repetition in the text "a substitute is sort of counter which is used in place of the repetition of a particular item" (p. 89). Unlike reference, which represents a relation between different meanings, substitution represents a relation between different linguistic items like words and phrases i.e. it refers to a grammatical relation in the wording, not the meaning (p. 90). Moreover, they have made a clear distinction between substitution and reference “In terms of the linguistic system, reference is a relation on the semantic level, whereas substitution is a relation on the lexicogrammatical level, the level of grammar and vocabulary, or linguistic form” (p. 89).

In addition, Halliday and Hasan (1976) declare: “Since substitution is a grammatical relation, a relation in the wording rather than in the meaning, the different types of substitution are defended grammatically” (p. 90). Hence, there are three types of substitution: nominal, verbal, and causal.

1. Nominal substitution:

This type of substitution is generally found in texts. It is often signaled when a noun or a nominal group is replaced by (one, ones). It functions as the head of the nominal group. 2. Verbal substitution:

It refers to the replacement of a verb or a verbal group, by another verb “to do” which functions as the head of the verbal group.

3. Causal substitution:

It refers to the replacement of an entire clause by (so, or not). 1.4.1.3. Ellipsis:

McCarthy (1991), states “Ellipsis is the omission of elements normally required by the grammar which the speaker/writer assumes are obvious from the context and therefore need not be raised” (p. 43). In other words, ellipsis is often when the structure of a text misses some element, i.e. it is when an item is omitted. However, he adds that what is special about ellipsis

is that the meaning is not affected by the omission because this does not have an effect on the whole meaning of the text. Hence, it is easy for the reader to deduce the meaning from the rest of the text (p. 43).

Nunan (1993) indicates “ellipsis occurs when some essential structural element is omitted from a sentence or a clause and can only be recovered by referring to an element in the preceding text” (p. 25).

Jabeen, Mehmood, and Iqbal (2013) declare: “The idea of omitting part of sentences on the assumption that an earlier sentence will make the meaning clear is known as ellipsis” (p. 126).

Tajeddin and Rahimi (2017), write “Ellipsis is the omission from speech or writing of a word or words that are superfluous or can be understood from contextual clues” (p. 3). Additionally, Thomas (1979: 43) says: “Ellipsis concerns the absence of linguistic elements from the overt form of sentences (as cited in Tajeddin and Rahimi, 2017, p. 3).

Kennedy (2003), points out: “Ellipsis is the process by which noun phrases, verb phrases or clauses are deleted (or ‘understood’ when they are absent)” (p. 324).

According to Halliday and Hasan (1976), ellipsis is similar to substitution; it is the act of omitting a certain word or part from the sentence. Ellipsis is described simply as “substitution by zero” (p. 141). Moreover, they add “the notion that ellipsis occurs when something that is structurally necessarily is left unsaid: there is a sense of incompleteness associated with it”. Ellipsis is a relation within the text; it is a special case of substitution. Furthermore, it is the omission of a linguistic item because the meaning is clearly understood from the context (p. 144). As a result, in English, there three main types of ellipsis: nominal, verbal, and causal.

1. Nominal Ellipsis:

It is about replacing a noun, a pronoun, a noun phrase, or omitting a noun head. E.g. “Nelly liked the green tiles; myself I preferred the blue” (McCarthy, 1991, p. 43). 2. Verbal Ellipsis:

It replaces a verb with a “pro-form”; it is about replacing the omitted verb. E.g. “Paul likes muffins. Sara does too” (Kennedy, 2003, p. 324).

3. Causal Ellipsis:

It refers to the omission of a clause; it uses a pro-form to replace a clause. E.g. “I went to the pictures, and Jane did too” (Kennedy, 2003, p. 324).

1.4.1.4. Conjunction:

McCarthy (1991) states: “A conjunction does not set off a search backward or forward for its referent, but it does presuppose a textual sequence, and signals a relationship between segments of the discourse” (p. 45). Halliday and Hasan (1976) argue: “Conjunctive elements are cohesive not in themselves but indirectly, by virtue of their specific meanings which presuppose the presence of other components in the discourse” (p.226).

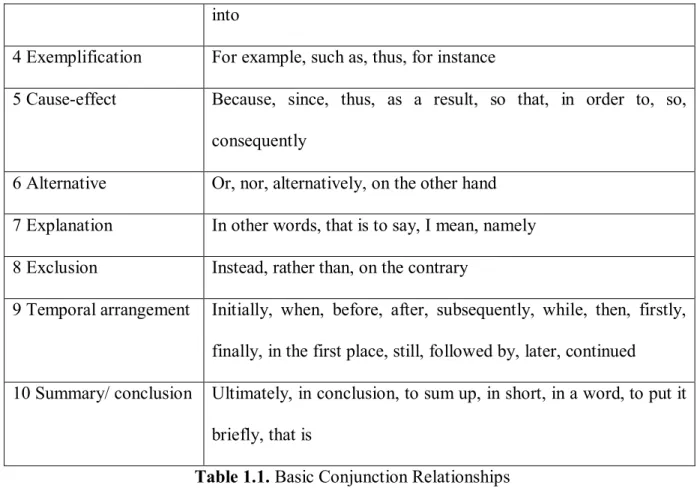

The conjunction is different from all the previous grammatical cohesive devices. In contrast to those cohesive ties which accomplish their meaning by backward or forward for their reference in the text, conjunctions do express their own meaning. Besides, Kennedy (2003) states that grammatical cohesion in texts is also achieved by various conjunction relationships which are shown in the following table:

Relationship Examples of logical connectives

1 Addition/inclusion And, furthermore, besides, also, in addition, similarly

2 Contrast But, although, despite, yet, however, still, on the other hand, nevertheless

into

4 Exemplification For example, such as, thus, for instance

5 Cause-effect Because, since, thus, as a result, so that, in order to, so, consequently

6 Alternative Or, nor, alternatively, on the other hand 7 Explanation In other words, that is to say, I mean, namely 8 Exclusion Instead, rather than, on the contrary

9 Temporal arrangement Initially, when, before, after, subsequently, while, then, firstly, finally, in the first place, still, followed by, later, continued 10 Summary/ conclusion Ultimately, in conclusion, to sum up, in short, in a word, to put it

briefly, that is

Table 1.1. Basic Conjunction Relationships (Retrieved from Kennedy, 2003, p. 325)

Furthermore, Brown and Yule (1983) as well as many other linguists have classified conjunction into four categories: additive, adversative, causal, and temporal. Also, Halliday and Hasan (1976) provide the following examples for each types of conjunction:

1. Additive Conjunction:

The main function of the additive conjunctions is to link sentences together; they add more information.

E.g. “I couldn’t send all the horses, you know, because two of them are wanted in the game. And I haven’t send the too messengers either” (p. 246).

2. Adversative Conjunction:

Adversative conjunctions are used to connect both similar and different ideas.

E.g. “All the figures were correct, they’d been checked. Yet, the total came out wrong” (p. 250).

3. Causal Conjunction:

Causal conjunctions are used to give the reason why something happens. It also indicates the cause-effect relationship between ideas.

E.g. “You aren’t living, are you? Because I’ve got something to say to you” (p. 258). 4. Temporal Conjunction:

Temporal conjunctions are used to locate ideas or events according to the time of the text or the real world time.

E.g. “The weather cleared just as the party approached the summit. Until then, they has seen nothing of the panorama around” (p. 263).

1.4.2. Lexical cohesion:

Halliday and Hasan (1976), state “This is the cohesive effect achieved by the selection of vocabulary” (p. 275). In addition, Kennedy (2003), states “Lexical cohesion is achieved through the selection of vocabulary” (p. 22). Moreover, Bahaziq (2016) points out that lexical cohesion involves the choice of vocabulary: its main interest is the relationship which exists between different lexical items in a text such as words and phrases (p. 114).

Furthermore, Renkema (2004) provides a definition for lexical cohesion: it “refers to the links between the content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs) which are used in subsequent segments of discourse. Two types of lexical cohesion can be distinguished: reiteration and collocation” (p. 105).

1.4.2.1. Reiteration:

According to Halliday and Hasan (1976), reiteration refers to two items sharing the same referent which could have similar meanings or repeated in the text (as cited in Bahaziq, 2016, p. 114).

Reiteration is a form of lexical cohesion which involves the repetition of a lexical item, at one end of the scale; the use of general word to refer back to lexical item, at the other end of the scale; and a number of the things between the uses of synonym, near-synonym, or superordinate. (p. 278).

Furthermore, they identified four types of reiteration: repetition, synonym, near-Snynonym, and superordinate.

1. Repetition:

Repetition is the most common form among the lexical devices. It is simply about the repetition of words or word phrases which are in relation to the text. For example: “After heavy rain the river often floods these houses. However, last May, in spite of continuous rain for 20 hours, the river stayed within its banks” (Kennedy, 2003, p. 323).

2. Synonymy:

In contrast to repetition, Synonymy is to replace the same word by similar or close words which have the same meaning and fit the context. For example: “Accordingly... I took leave, and turned to the ascent of the peak. The climb is perfectly easy. Here, ‘ascent’ is a synonym of and refers back to ‘climb’” (Halliday and Hasan, 1976, p. 278).

3. Near-synonymy:

It refers to the connection between two words which do not have the exact spelling. Instead, these words have an almost close and similar meaning. For example: “Then quickly rose Sir Bedivere, and ran, And leaping down the ridges lightly, plung’d among the bulrush bed, and clutch’d the sword. And lightly wheel’d and threw it. The great brand made ligh’nings in the splendor of the moon...” Hence, brand refers back to the near synonym which is ‘sword’ (Halliday and Hasan, 1976, p. 278).

4. Superordinate:

It is also called hyponymy; it refers to items of ‘general-specific’ or ‘an example of’ relationship (Paltridge, 2012, p. 119 as cited in bahaziq, 2016, p. 114). It is the relation of the meaning between both: the more general and the more specific terms. For example, Henry’s bought himself a new Jaguar. He practically lives in the car. Here ‘car’ refers back to ‘Jaguar’; it is its superordinate (Halliday and Hasan, 1976, p. 278).

1.4.2.2. Collocations:

Bahaziq (2016) writes that collocation is a set of vocabulary items which occur simultaneously. It is composed of a collection of adjectives and nouns like ‘fast-food’, verbs and nouns like: ‘run out of money’, and other different items like: ‘men’, ‘women’ (p.114). Moreover, Renkema (2004), states that collocation in concerned with the relationship between words because these words often occur in the same setting. For example: “Red Cross helicopters were in the air continuously. The blood bank will soon desperately in need for donors” (p. 105).

REFERENCE: Items that refer to something else in the text for their interpretation. (1) pronominal: e.g., he, her, they, theirs

(2) proper nouns: e.g., Brandon, Ms. Sharon

(3) demonstratives: e.g., this/these, that/those, here/there

(4) comparatives: identity/similarity/difference/ordinals/comparatives/superatives, e.g., same, similar, such, bigger

CONJUNCTION: Connectors between two independent sentences. (1) Additive: e.g., and, or, by the way

(2) Adversative: e.g., but, yet, however, rather (3) Causal: e.g., so, therefore, thus

ELLIPSIS: Elements left unsaid or unwritten but are understood by the reader/speaker. (1) Noun ellipsis: delete nouns, e.g., He liked the blue hat; I myself liked the white. (2) Verbal ellipsis: delete verbs, e.g., Tom drew a small boat and April a big boat. (3) Clausal ellipsis: delete clauses, e.g., A: Will you go? B: Yes ;

A: Would you like something to drink? B: Sure.

SUBSTITUTION: The replacement of word or structure by a "dummy" word. (1) Noun substitution: e.g., Tom drew a big boat and April drew a small one. (2) Verb substitution: e.g., He wanted to draw pictures there, and they really did. LEXICAL TIES:

(1) Collocation: e.g., go home, have fun, rain/rainy/wet/umbrella/soaked (2) Repetition: e.g., drew/draw/drawing, rain/raining/rainy

(3) Synonym: e.g., sad/unhappy (4) Antonym: e.g., boy/girl, big/small

(5) Hyponymy (general-specific relations): e.g., fruit/banana, apple

(6) Meronymy (part-whole relations): e.g., house/door, room, wall, kitchen

Table 1.2. Types of Cohesion summarized from Cook, 1989; Halliday & Hasan, 1976, 1989; McCarthy, 1991; Renkema, 1993

(Retrieved from Bae, 2002, p. 56) 1.5. Coherence:

De Beaugrande and Dressler (1981), point out that coherence “concerns the way in which the things that the text is about, called the textual world, are mutually accessible and relevant”. It is the logical relationship between ideas and meanings (p. 4). In other words, when sentences and ideas are connected and flow together smoothly, coherence is attained. Without coherence, the reader would not be able to comprehend the main points and ideas of

an essay. Hence, coherence enables the reader to move easily from one idea to another, from one sentence to another, and from one paragraph to another.

Also, Johns (1986) provides a definition of coherence as follows:

Coherence is defined by some as a feature internal to text. In traditional handbooks, this feature is divided into two constructs: cohesion (i.e., the linking of sentences) and unity (i.e., sticking to the point). Often, these constructs are introduced separately, as if, in fact, they could be separated in written. (p. 248).

Furthermore, Johns (1986) suggests that coherence involves text and reader based features. Text-based features are the connections between sentences and phrases (cohesion) and sticking to the point (unity). However, reader-based features are the readers’ interactions towards the text using their prior knowledge of the content. When the text expressions (text-based features) are aroused in a person, the person recalls his experiences and expectations towards the linked events and situations (reader-based features). As a consequence, this person raises different predictions and hypothesis of the following information. If there are a response and a continuity of senses in the rest of the text, that person automatically feels that the text is coherent (pp. 248-250).

In addition, Suwandi (2016) declares:

A text is considered incoherent when the words or sentences in each paragraph are not fitting together well. They are just like a list of points or ideas with no connection to each other, which result in readers’ difficulty in following the writer’s ideas. (p. 254). Bae (2001) conducted an investigation in which he discussed the concepts of cohesion and coherence. In his article, he clarifies that coherence occurs when all the parts of the text are logically well connected so as that the text’s quality is pleasing or makes sense. The connection is partly established via cohesion (Halliday and Hasan, 1989, p. 247), and partly

via the outside text knowledge possessed by the reader or the listener (Renkema, 1993, p. 35). They can be genre expectation, reader expectations, and background knowledge (p. 52).

Moreover, the publication of Halliday and Hasan’s Cohesion in English highly influenced both the understanding and the teaching of the features of coherence. Many linguists believe that a coherent text has two main characteristics: cohesion and register. The first is about ties between sentences, and the latter is about coherence with a context (p. 248). 1.6. Types of Meaning:

Umagandhi and Vinothini (2017), in their journal, discuss Leech’s seven types of meaning in semantics. Geoffrey Leech (1981) studied the meaning deeply and broke it down into seven types: logical or conceptual meaning, connotative meaning, social meaning, affective meaning, reflected meaning, collocative meaning, and thematic meaning. Leech’s logical or conceptual meaning is the same as designative meaning, while connotative meaning was different from connotation. Except for conceptual and thematic meanings, the other five types of meaning are called associative meaning. They are explained as the following:

1.6.1. Conceptual/ Logical Meaning:

This type of meaning is also labeled by some scholars as denotative, cognitive, descriptive, or designative meaning. This type of meaning was considered as the main feature of linguistic communication that is integral in the functioning of language. Leech considers conceptual meaning as fundamental because it is identical in structure and organization to the phonological and syntactic levels of language. Moreover, two of the basic principles for conceptual meaning are the structure and constructiveness principles. They are the two structural principles which seem to be the basis of all linguistic patterning. In fact, the two principles of a constituent structure display how language is organized (p. 71). In other words, Besides, Setiawan (2014) provides an example of conceptual or logical meaning: “woman”.

Woman = human+ female+ adult. Conceptual meaning refers to the literal meaning of the word displaying the concept or idea to which it refers.

1.6.2. Connotative Meaning:

According to Leech, the connotative meaning is the communicative value that expression has by virtue to what it refers to over and above its purely conceptual content. These are the features of the segment of the real world or the referent that is not included within the conceptual meaning. There are only a few constructive or criteria features that display the fundamental criterion of the correct use of words. He adds that the connotative meaning is mainly concerned with real-life experiences. However, it differs according to historical periods, culture, beliefs, and each individual's experiences and knowledge. Moreover, it is composed of an indeterminate open-ended set of features (p. 72). An example for this would be: “There is no place like home”. Home may denote the real building that someone lives in. However, connotatively, it indicates family, secure, comfort, peace, etc. 1.6.3. Social Meaning:

This type of meaning is concerned with the two aspects of communication that are retrieved from the environment or the situation in which the utterance is produced in a language. In simple words, the social meaning is related to the situation in which the utterance is used. Besides, the social meaning is about the information in a piece of language concerning the social context of its use such as word, sentence, phrase, pronunciation variation, etc. It is understood via recognizing various levels of style and dimensions within the same language.

However, in a social situation, the functional meaning of a sentence may vary from the conceptual meaning because of its illocutionary force. Aspects of language diversity can be social or regional dialect variation, style variation (formal, informal, or slang, etc). Hence, the decoding of messages depends on the person’s knowledge of stylistics and variations. For

instance, some words or pronunciations are recognized to be dialectical, i.e., showing the social or regional origin of the speaker (p. 72).In addition, Setiawan (2014) provides an example of social meaning: “I ain’t done nothing”. This sentence clearly denotes that the speaker is possibly an African American who is not educated and underprivileged.

1.6.4. Affective Meaning:

Affective meaning is a part of meaning which displays the personal feelings and emotions of the speaker. It also includes the speaker’s reaction to what the listener is talking about. In other words, it refers to the emotions or effects aroused in the reader or listener. Unlike the social meaning, this meaning is not only about the difference in the use of words and lexemes, rather, but factors of intonation and voice-timbre are also considered as tone of voice (p. 72). Moreover, Setiawan (2014) provides an example of affective meaning: “Home” for a soldier, expatriate, or a sailor means everything to him.

1.6.5. Reflected Meaning:

It is the meaning which arises when a word has two or more than one conceptual meaning or polysemous. This type of meaning occurs when a sense of a certain word forms a part in the response or reaction to another sense. Moreover, it also occurs due to the relationship between words and sentences or the interconnection on the lexical level of language (p. 72). Furthermore, Setiawan (2014) provides an example of reflected meaning: when one hears “Church” service, The Comforter and The Holy Ghost immediately come into his mind because they are the synonymous expressions which indicate the Third Trinity. However, the Holy Ghost sounds amazing while the Comforter sounds cozy and consoling. 1.6.6. Collocative Meaning:

Collocative meaning is composed of the association in which a word acquires the meanings which occur in its environment. In other words, it is the meaning that a word obtains in the company of other words (p. 72). In addition, Setiawan (2014) provides an

example of of collocative meaning: “pretty” and “handsome” denote someone who is good looking.

1.6.7. Thematic Meaning:

Thematic meaning relates to what is communicated in a particular way. It occurs when the speaker or writer forms the message in terms of the focus, emphasis, and organization. It can also be expressed through intonation and stress in order to highlight and emphasis a certain part of the sentence. In addition, the way in which the message is ordered conveys what is important and what is not (p. 72). Moreover, Setiawan (2014) provides an example of thematic meaning: A. Mrs Bessie Smith donated the first prize.

B. The first prize was donated by Mrs Bessie Smith.

In the first sentence, the emphasis in on who gave the prize, whereas in the sentence, what did Mrs Smith gave is more important. Hence, the meaning changes with the change of emphasis.

1.7. Context and Meaning:

Al-Hindawi and Abu-Krooz (2017), in their article, argue that Firth’s outstanding students set their researching effort’s direction towards the field of context. Following Firth, Ullmann (1963), and Halliday (1985), they developed their teacher’s research concerning the relationship between context and meaning. In his book, Ullmann cited Firth’s ideas confirming that the theory of context provided the required measures in order to clarify and provide details for meanings. Moreover, this can occur by maintaining what their teacher calls: putting facts in a series of frequent contexts, i.e., one of the contexts would indicate what is coming next.

Therefore, (Halliday 1994: 10) gives the name 'culture context' for every separate context, which is a part of a large context and acquires its exact position in it. Furthermore,

Ullmann (1963), asserts that ‘context’ is a multidimensional term that is used to distinguish different meanings, mainly, the conventional one. Moreover, they add:

The role of context in the interpretation of a linguistic unit has long been considered, even if from different perspectives: from the view that regards context as an extralinguistic feature, to the position that meaning is only meaning in use and therefore, pragmatics and semantics are inseparable. (p. 5).

1.8. The Relationship between Cohesion and Coherence:

Cohesion and coherence are two notions of the seven standards of textuality. They have been subjects to intensive debate in the international linguistic community as two important linguistic notions. After the publication of Halliday and Hasan’s crucial work “Cohesion in English” in 1976, cohesion became accepted as a well-established category for text and discourse analysis. Moreover, De Beaugrande and Dressler (1981) who consider cohesion and coherence to be two of the basic standards of textuality, stressed the importance of the relationship between them. Besides, they see cohesion and coherence as two totally separate phenomena, without one having an impact on the other (as cited in Tanskanen, 2006, p. 19).

Additionally, Tanskanen (2006) argues that cohesion and coherence are terms related to discourse analysis and text linguistics; they are set to describe the properties of written texts. However, a text may be cohesive but not necessarily coherent; cohesion does not generate coherence. Cohesion is determined by lexically and grammatically definite intersentential relationships, whereas coherence is based on semantic relationships. Moreover, cohesion refers to the intra-text connectedness of the items, while coherence refers to the suitability of the contextual occurrence of the text which conveys the message appropriately. In cohesion, the outer elements seem connected, whereas, in coherence, the elements of information or sense seem to form conceptual connectivity. Additionally, Coherence is set by

the reciprocal interaction between the writer and the reader in order to make sense of the text based on their shared background knowledge outside the text (p. 21).

1.9. Cohesion and Coherence: Independent but Interrelated:

According to Tanskanen (2006), cohesion is about the relations of meaning which exist in a text and identify it as a text. As a part of the semantic system, cohesion is achieved through vocabulary and grammar. Moreover, it is divided into grammatical cohesion, including reference, substitution, ellipsis, conjunction, and lexical cohesion, including reiteration and collocation. However, unless grammatical and lexical elements are interpreted according to their relation to other elements in the text, they do not become cohesive. Thus, a cohesive tie which contributes to the unity of the text is formed when two elements in text are linked (pp. 15-16).

Moreover, Tanskanen (2006) adds that researchers harshly criticized Halliday and Hasan’s viewpoint that overt markers of cohesion are enough to make a text linked together and proved that cohesion was not necessary at all to make a text seem like a unified whole. Rather, what is important is the coherence or the unity amongst the prepositional units in the text. Hence, “without coherence, a set of sentences would not form a text, no matter how many cohesive links there were between the sentences” (p. 16).

Tanskanen (2006) argues:

Researchers mostly agree that there is a difference between cohesion and coherence, but there is considerable disagreement on what actually differentiates between the two. It is generally accepted, however, that cohesion refers to the grammatical and lexical elements on the surface of a text which can form connections between parts of the text. Coherence, on the other hand, resides not in the text, but is rather the outcome of a dialogue between the text and its listener or reader. (p. 7).

Furthermore, cohesion contributes to coherence; it signals coherence in texts. On the one hand, cohesion is a more formal, grammatical, and explicit property. It is easily divided into different sub-dimensions. On the other hand, coherence is more pragmatic in nature, a matter of relevance, and more a universal property. It is not apt to division into sub-dimensions (p. 19).

Conclusion

This chapter tackles the definitions of discourse analysis, text, texture, and cohesion. The concept of cohesion is a semantic one; it refers to the relations of meaning which exist within the text. Accordingly, cohesion has two types lexical and grammatical. This chapter also discusses the concept of coherence, the types of meaning, context and meaning, and the relationship between cohesion and coherence. Both cohesion and coherence have a significant contribution to maintaining the unity and organization of the paragraphs in essays. In addition, cohesion and coherence are interrelated; they complete each other. Whenever there are cohesion and coherence, there would be a smooth flow of ideas. Coherence cannot exist without cohesion, and it is the opposite of cohesion. As a consequence, the text is best understood and comprehensible with the use of cohesive devices and coherence.

CHAPTER TWO EFL Essay Writing Introduction

Writing is a very important skill that helps students to express their opinions, thoughts, and ideas. It also plays an important role in helping EFL learners to learn and master the language. This chapter discusses the writing skill, the writing process and its components, the importance of writing; as well as; the writing problems encountered by EFL students. Writing is one of the ways to communicate certain messages for certain purposes. The purposes are to express the self, to provide information for the reader, to persuade him, and to create a literary work. It also deals with the composition of essays, their main components, and types.

2.1. Definitions

2.1.1. Foreign Language (FL):

Broughton, Brumfit, Flavell, Hill, and Pincas (1980) state that a language is a tool which helps people to guide themselves in their daily life and in the world. They add that a language that is learned in the classroom or via special classes and not spoken in the society is a FL. It is the contrary of a native language and different from a second language (p. 5). 2.1.2. English as a Foreign Language (EFL):

Broughton et al. (1980) state that English as a foreign language is a language that is often learned and spoken by non-native English speakers; one that is often not commonly spoken in certain countries. As English foreign language learners, Algerian students have to make efforts to know more about the target language and all its aspects in general. So, in order to achieve their goal, which is to learn English as a foreign language, students usually need to raise questions about everything related to that language. They also need to be active to learn more and be self-confident, because these two factors help them to achieve such a goal. Moreover, they add: “It may be seen, then, that the role of English within a nation’s