Design of Creative Narrative and Technical Systems for an Immersive

Multimedia Nighttime Spectacular Show

by Garrett V. Parrish

SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF

BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING AS RECOMMENDED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING AT THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May2017 \3ulknet 7.01-13

@2017 Garrett V. Parrish. All rights reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part

in any medium now known or hereafter created.

Signature of Author:

Signature redacted

Certified by:

fl~n~rtmant ,~f ~~.1JLIE LI I I~..I IL '.JI Mechanical Engineering May 22, 2017

Signature redacted

Maria Yang Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering Thesis Supervisor

Signature redacted

Accepted by:Associate Professor

ARCHIVES

M AS$O STM9ETS TITUTiEOF TECHNOLOGY

JUL 2

5

2017

LIBRARIES

Rohit Karnik of Mechanical Engineering Undergraduate Officer

Design of Creative Narrative and Technical Systems for an Immersive

Multimedia Nighttime Spectacular Show

by Garrett V. Parrish

SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF

BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING AS RECOMMENDED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING AT THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

Abstract

The goal of this thesis is to explore the design process for the creative and technical components of a nighttime spectacular show. As spectacular shows are a unique art form with unusual narrative structures and conventions and complex technical systems involved in their implementation, they present an intriguing case study for the design process. There exists almost no academic literature on the process used to effectively design and construct large scale entertainment experiences as virtually all of those projects are carried out in the private sector and any innovations required to complete the projects are documented in patents as opposed to academic publications. With a specific narrative goal in mind and distinct derivative works, a twelve minute show narrative was written and designed. Furthermore, the various production elements (set, lighting, audio, music, and control systems) were also designed and constructed to serve as an explicit implementation of the creative narrative. The show consists of three main 'acts', with individual beats and scenes, each of which fulfills a certain set of creative and technical design requirements. The practical producing of this show is exempt from this thesis as the focus is on the creative narrative and technical systems design processes.

Thesis Supervisor: Maria Yang

Title: Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Professor Maria Yang for her guidance, advice, and

support throughout the development and writing of this thesis.

The author would like to thank MIT CAC for their generous support throughout the

process of producing this project, financial support with venue registration, and continued

support for further iterations of the project.

The author would like to thank the Council for the Arts at MIT for their generous funding

of this project, their continued support throughout the various challenges this project has

presented, and for their institutional support for new and unique art projects on campus.

The author would like to thank the Saint Anthony Educational Foundation for their

generous financial contribution to this project and to the fraternity of Delta Psi for their

continual support for the author throughout the process of writing this thesis.

The author would like to thank Ben Bloomberg for his support throughout the

development and production of this project.

The author would like to thank Peter Torpey and Peter Agoos for their narrative and

technical guidance throughout the development of this project.

The author would like to thank Josh Higgason and Sara Brown for their continued

technical and creative support throughout the development of this project.

The author would like to thank Seth Riskin, director of the MIT Museum Studio, for his

support through the MIT Museum Studio.

The author would like to especially thank Alex, Chelsea, and Donna Parrish for their

eternal support for this thesis and project throughout the process.

Table of Contents

Abstract 2 Acknowledgements 3 Table of Contents 4 List of Figures 6 List of Tables 8 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: Background 10 2.1 Spectacle 10 2.2 Modern Spectaculars 11Chapter 3: Creative and Technical Requirements 14

3.1 The Spectacular Design Process 14

3.1.1 Lighting Design 16

3.1.2 Sound Design 16

3.1.3 Video Design 16

3.1.4 Set Design 17

3.1.5 Show Control and Cueing Systems 17

3.2 A Parallel Creative and Technical Design Approach 18

3.2.1 New Technology Availability 18

3.2.2 Driving Technical Innovation with Creative Incentive 18

3.3 "Story is King" 19

Chapter 4: The Narrative Design Process 20

4.1 Narrative and Thematic Exploration 20

4.2 Thematic Selection 20

4.3 Thematic Structure 22

4.4 Scene-Based Concept Art 22

4.5 Concept Arranging 23

4.6 Narrative Outlining 25

4.8 Show Timeline 27

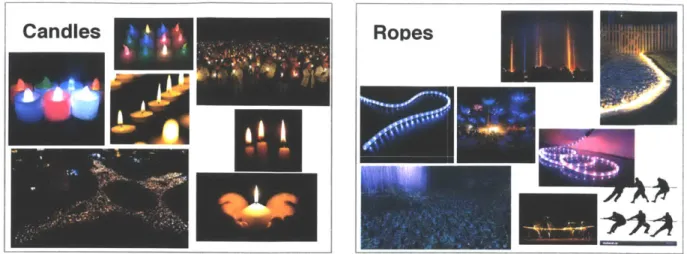

4.9 Visual Inspiration 27

4.10 Script Writing 28

4.11 Musical Development 29

Chapter 5: Production Planning 30

5.1 Venue Selection 30

5.1.1 Creative Design Requirements 31

5.1.2 Technical Design Requirements 31

5.1.3 Venue Selection and Alternatives 32

5.2 Budget Definition 33

5.3 Production Schedule Definition 34

5.4 Design Management Techniques 34

Chapter 6: The Technical Design and Implementation Process 35

6.1 Production Specifications Specific to Chosen Venue 35

6.2 Production Element Definition 37

6.3 Sound Systems Design and Placement 37

6.4 Central Structure Design 38

6.5 Lighting Design and Placement 40

6.6 Projection Design 42

6.6.1 Projection Surfaces 42

6.6.2 Projection Instruments 43

6.7 Overall Technical Architecture Design 44

6.8 Final Production Plan 45

6.9 Equipment Procurement 46

Chapter 7: Future considerations 46

7.1 New Venue: Killian Court 47

List of Figures

Figure 1: World of Color at Disney California Adventure in Anaheim, CA. 11 Figure 2: Illuminations: Reflections of Earth at EPCOT in Orlando, FL. 12

Figure 3: 2008 Olympic Opening Ceremonies in Beijing, China. 13

Figure 4: Notes and insights on structural and production-level spectacular design. 14

Figure 5: Structural narrative research on existing spectaculars. 20

Figure 6: Explorations of various themes and selection of technology. 21

Figure 7: A thematic brainstorm on a whiteboard. 22

Figure 8: Concept art for the scenes of Sparks of Hope. 23

Figure 9: Concept ordering and brainstorming for each scene. 24

Figure 10: Storyboards for the main visual and thematic beats of each scene. 26

Figure 11: Show outline and timeline. 27

Figure 12: Research image collages. 28

Figure 13. Musical sketch for the opening of Sparks of Hope. 30

Figure 14: Morss Hall in Walker Memorial Hall at MIT. 32

Figure 15: Budget excerpt. 33

Figure 16: Production schedule defined for the Sparks of Hope. 34

Figure 17: Management spreadsheet for Sparks of Hope. 35

Figure 18: Morss Hall balconies. 35

Figure 19: Morss Hall murals. 36

Figure 20: Morss Hall architectural and structural features. 36

Figure 21: Sound systems Design 37

Figure 22: Concept sketches for central object. 38

Figure 23: Prototype obelisk and design sketches/schematics. 39

Figure 24: Production-level central structure truss design. 40

Figure 25: Lighting design working documents. 40

Figure 26: Projection on the central mural in Morss Hall. 42

Figure 27: Projection on paper surfaces hanging from right and left balconies. 43

Figure 28: Projector instrument calculations and decisions. 43

Figure 29: Selected projector testing in venue. 44

Figure 30: Show control architecture. 44

Figure 31: Hand-drawn production plan. 45

Figure 32: VectorWorks plans of the venue and all the included production elements. 46 Figure 33: Concept sketch for Sparks of Hope in Killian Court. 47

List of Tables

Table 1: An empirically observed outline of creative development for a spectacular. 15

Table 2. Creative requirements for venue selection. 31

Table 3. Technical requirements for venue selection. 31

Table 4. Venue alternatives. 32

Table 5: Final lighting design manifest. 41

Chapter 1: Introduction

It is clear that the accelerating pace of technological development leads to new and

complex problems for our society. For those that study and create technology, these challenges

are embedded in all of their work. With the power to create and understand technology, a

responsibility arrises to do so in a meaningful, ethical, and mature manner. However, this is not

always the case. It has become easy, with the accelerating speed, detachment, and power of

technology for people to use it in such a way that abandons the empathy, understanding, and

emotion that makes people human. However, technologists should make sure that their work is

done with a respect and awareness of what makes our species 'human'. And, they should find

hope in the fact that many throughout society are working to find a balance between humanity

and technology. These concepts are the central conceits of the show and the underlying goal of

this project is to communicate these ideas to a wide and receptive audience.

With such a lofty, vague, and un-scientific goal in mind (i.e. to engender empathy and

understanding when using and designing technology) there are various means by which one can

approach achieving it. One method that the author has always believed to be incredibly

powerful is art, specifically large-scale spectacular show design and production. A spectacular is

typically a large nighttime multi-media show that primarily uses visual means to convey a simple

narrative or message. Therefore, this thesis project encapsulates the design and production

processes undertaken by the author to design a nighttime spectacular show with the specific

goal of communicating the above concepts to an audience, specifically the MIT community. As

this show was designed for and executed at MIT, primarily for the incoming freshman class, it

presents an excellent opportunity to reach a young and inspired audience and to advocate for

the concepts and ideals proposed in a meaningful way.

Specifically, this thesis details the design process for both the creative and technical

elements of the nighttime spectacular show, entitled Sparks of Hope: An Epic Spectacular on

Humanity and Technology, made for the explained purpose. The 'show', as it will be referred to

throughout this thesis, is a multi-media indoor narrative production lasting approximately

twelve minutes that tells the story of humanity and technology from the discovery of fire to the

present day. The show incorporates various sensory, lighting, visual, and sonic technologies and

production elements. This project is presented as a design case study with the goal of exploring, defining, and analyzing the process by which a multimedia nighttime spectacular show is

designed, planned, and executed. Though the final outcome of the design process is still in

continuous development (the production is scheduled for a date after completion of this thesis)

the majority of the design process is complete and is therefore able to be analyzed.

Chapter 2: Background

2.1 Spectacle

For the purpose of this thesis, it is critical to define the concept of 'spectacle'. This is the

basis upon which this design case study is formed. Spectacle refers to a visually striking

large-scale performance or display. The concept of 'spectacle' dates back several centuries where the

custom of using fireworks displays were seen as a popular expression of joy or 'allegrezza'

throughout the European continent.1 Fireworks displays are commonly manifestations of

spectacles and are often used as an element in large multi-media shows such as the opening

ceremonies of the Olympics, the Super Bowl half-time shows, and Cirque Du Soleil productions.

I Marcigliano, A. (1989). The Development of the Fireworks Display and its Contribution to Dramatic Art in Renaissance Ferrara. Theatre Research International, 14(1), 1-13. doi:10.1017/S0307883300005514

Fireworks, along with other production elements such as video, projection, lighting, C02, haze,

sets and performers are all elements that can be used by designers to achieve visual spectacle.

2.2 Modern Spectaculars

Figure 1: World of Color at Disney California Adventure in Anaheim, CA.

Inspired by the concept of 'spectacle', several large corporations and organizations have

turned to the design of nighttime 'spectaculars' as a way of engaging large audiences in a

meaningful and memorable way. This has thus led to the development of these shows and a

growing presence of their creative and technical canon throughout the entertainment industry.

As certain production technologies have become more prevalent, inexpensive, and available,

large-scale visual spectacles have risen in popularity. It is critical, however, to distinguish

between music concerts and tours or traditional fireworks displays and 'nighttime spectaculars.'

For the purpose of this thesis, a spectacular is defined as a relatively short narrative-driven

multimedia visual experience, typically outdoors. This distinguishes it from its companion art

forms due to its unique structure, rules of engagement, production and reception.

Figure 2: Illuminations: Reflections of Earth at EPCOT in Orlando, FL.

The themed entertainment industry produces some of the highest-budget and highest

quality spectaculars in the world. By incorporating large nighttime shows into theme parks, companies such as The Walt Disney Company and NBC Universal can guarantee a large regular

audience for their spectaculars and therefore justify large investments in their creative

development and technical production. Figures 12 and 23 show examples of themed

entertainment shows produced by Walt Disney Imagineering's Creative Entertainment division.

Both Illuminations: Reflections of Earth4 and World of Color5 are critically acclaimed, widely

lauded, and reach millions of guests each year. Both are stellar examples of current spectaculars

and served as baselines and cases studies throughout this design process.

2 https://disneyland.disney.go.com/entertainment/disney-california-adventure/world-of-color/ 3 https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/entertainment/epcot/illuminations-reflections-of-earth/

4 "All-time Winners By Category." The Golden Ticket Awards I Presented by Amusement Today. N.p., 19 Sept.

2016. Web. 15 May 2017.

5 "Thea Awards Announced for 'World of Color' and Disney Imagineer Kim Irvine." Disney Parks Blog. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 May 2017.

Figure 3: 2008 Olympic Opening Ceremonies in Beijing, China.

Arguably, some of the most widely known examples of modern spectaculars are the

Olympic opening ceremonies.6 Countries that host the Olympics use the global audience that

watch the opening ceremonies to promote their country's heritage and culture to the rest of the

world.7 Since the opening ceremonies are funded by budgets in the billions of dollars, these

shows tend to be virtually the most massive and expensive on the planet. In addition to cost,

these ceremonies require a degree of complexity almost unheard of for other traditional

entertainment shows even going so far as to alter the weather on the day of the show to ensure

success.8 For example, the Beijing Opening ceremony during the Summer Olympics of 2008 cost

(at a low estimate) upwards of $100 million dollars, putting the running cost of the show at

nearly $476,000 per minute and nearly $8,000 per second.9 This was the largest budget of any

single-night show in public history and demonstrates the sheer magnitude of complexity and

6 "A Brief History of the Opening Ceremonies -Photo Essays." Time. Time Inc., n.d. Web. 15 May 2017. 7 "Ancient Olympic Games". The Olympic Movement. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

8 "Beijing disperses rain to dry Olympic night." Beijing 2008 Olympic Games. Xinhuanet, 9 Aug. 2008. Web. 15

May 2017. <http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2008-08/09/content_9079637.htm>.

9 Brand, Madeleine, Howard Berkes, Linton Weeks, and Uri Berliner. "China Celebrates Opening Of Summer Olympics." NPR. NPR, 08 Aug. 2008. Web. 15 May 2017.

13 of 47

Nor_ 1

cost that nighttime spectaculars can require for success. Beijing's opening ceremony was one of

the most universally lauded and cataloged nighttime spectaculars in history, shown in figure 310.

All of these examples of nighttime spectaculars served as design case studies for this thesis. Figure 4 shows notes and insights documented from researching the narrative,

structural, production, and technical elements of these shows. These notes and insights were

absolutely critical to establishing basic design requirements when designing the show. The

author borrowed heavily from existing techniques and successes of previous spectaculars that

the author observed through this background research.

J -Z ,4

/ /' 'J///

Figure 4: Notes and insights on structural and production-level spectacular design.

Chapter 3: Creative and Technical Design Requirements

3.1 The Spectacular Design Process

As the design and production of spectaculars exists far beyond the realm of academic

studies, research, and activity, there is little to no formal research or sources when it comes to

the creative and engineering design process employed by the creators of these shows.

Fortunately, the author had the personal opportunity to observe leaders in the entertainment

industry as they design spectaculars and was been able to gather information regarding the

design process. The author interviewed creative and technical directors they had worked with in

the past to empirically determine the design process they use when designing spectaculars.

Design Step Business Proposition Budget Determination Purpose

Most shows start out as a business proposition, either to celebrate the opening of a new theme park or to commemorate the anniversary of an organization.

Once the need for a show is determined, a business unit of the organization will likely allocate a certain amount of capital to the show's creators for development and production costs.

Scope and Scale With a budget, the shows creators collaborate with the business units to establish a Determination relative size length, complexity, and guest reach of the show prior to development.

Narrative Iteration Concept art Musical Development Show Timeline Creation Scene Storyboarding

With a scope in mind, the shows creators will begin iterating on the show's themes and motifs. They will usually come up with a general narrative structure and purpose for the show in conjunction with the show's producers.

Once a general narrative is established, the directors will use a concept artist to create visual concept renderings for the shows overall style, effects, and location.

Upon determination of the narrative structure, the directors will proceed to employ a composer to determine the musical tone and style of the show as well as to develop musical themes and motifs to be used throughout the show.

Once further narrative planning has been completed, the directors will create a written timeline of the show which details the main 'beats' or narrative plot points. Once a timeline is established, directors will work with concept artists to create renderings and plans for each beat within all scenes of the show.

Table 1: An empirically observed outline of creative development for a spectacular.

Once directors and producers have reached the step of scene storyboarding, they are

likely to start heavy technical development of the show, involving technical directors,

technicians, and technical designers. For the purposes of this thesis, only certain elements of

traditional spectacular production element canon will be considered. The following sections

detail the main technical elements associated with the design of a spectacular and describes the

various uses, deficits, and benefits of each separate technology.

3.1.1 Lighting Design

Lighting design constitutes a major component of nighttime spectaculars because the shows tend to occur outside and in the evening, thus requiring lighting instruments to achieve even the most basic of narrative effects. Additionally, moving head fixtures offer a standard and complexity-inexpensive way of adding dynamic control to a show. From a technical perspective, the selection, placement, powering, control, and programming of lights is of vital importance to the show's success.

3.1.2 Sound Design

Sound design encompasses all technical elements associated with the audio systems of the production in addition to the creative design and execution of all recording, mixing, mastering, and audio production. With the typical production of a custom-written music track for a spectacular, there are various technical elements required in the production, recording, mixing, mastering, and bouncing of the main music and audio tracks. This work can only then be heard via a robust and well-designed audio system of speakers, amplifiers, and controllers.

3.1.3 Video Design

As video technology has become more and more advanced over the past few decades, it has become increasingly incorporated into nighttime spectaculars. This medium often includes projection design; while televisions and LED screens are effective, they are more often then not simply too small to achieve the desired 'spectacular' effect. However, projection is used to great effect since it can transform physical surfaces such as buildings, fabric, water mist screens, or

the sky. Video design incorporates the selection and placement of projectors as well as the

technical elements required to design motion graphics and video content to be projected.

3.1.4 Set Design

Depending on the venue of a spectacular, there may be various 'set' elements

incorporated into the production. One of the major hallmarks of spectaculars is the concept of

using existing architectural or natural formations as 'set' pieces which give the illusion of a

known environment 'coming alive' as part of the production. However, designers often either

augment existing architectures or add dynamic set pieces to the production. Set can include

truss structures, symbolic or iconic set pieces, or simple stages for performers to stand on.

3.1.5 Show Control and Cueing Systems

Show control is arguably the most critical technical element of a spectacular. It is the

discipline that enables the show to be cued and timed accurately. There are various approaches

to electronic show control for spectaculars. Depending on the scale and unique requirements of

the show, certain aspects will be triggered manually while others automatically. For example,

lighting cues are typically programmed ahead of time and triggered via timecode. However,

pyrotechnics, by law (depending on the state), are required to be on a non-digital system that is

triggered manually by a licensed pyrotechnician, primarily due to safety concerns. Defining a

show control paradigm and technical architecture is the most critical design requirement for a

spectacular and must be done rationally, intelligently, and with full knowledge of all human,

production, and technical elements in mind.

3.2 A Parallel Creative and Technical Design Approach

In an ideal world, each technical element or discipline would receive a finalized set of

requirements and the creative directors would have an unlimited portfolio of technical means of achieving their vision. This is simply not the case in modern design contexts. Though it is difficult to operate in a dynamic manner, it is critical for both engineers and designers to design systems in relative parallelism so that design requirements can be coordinated and changed

quickly.

3.2.1 New Technology Availability

Entertainment technology is always increasing in capability and complexity. New innovations in lighting, rigging, projection, and construction technologies are making nighttime spectaculars more interesting and technically complex than ever. It is common for technical directors to present a new technology to a creative design team as a way of inspiring the creative directors to use that in their creative development. It is critical for creative directors to be aware of new technological innovations as much as it is critical for technical directors to understand the creative intent of a show. If there is a lack of ability to produce technical innovations, due to personnel, temporal or budgetary constraints, the design process should be geared towards incorporating existing technologies in new and creative ways.

3.2.2 Driving Technical Innovation with Creative Incentive

It is easy for engineers to simply rely on existing technologies and to not innovate

beyond what is currently known in the industry. Research and development is costly, sometimes

requires a non-technical mind to propose a creative vision that would require technical

innovation beyond what would be imagined by those familiar with technology. It is common,

though not always advantageous, to spur the development of new technologies via the request

of a creative director. When a design team takes this approach, it ensures that the production

design decisions are made with the creative vision in mind rather than permitting the narrative

and story to be dictated by existing technologies. This however is obviously not always possible

and creative directors must work within the boundaries of current technological capabilities to

realize their vision.

3.3 "Story is King"

There is one tenant of the design process that must be adhered to above all others: story

is king. This is a phrase coined by Ed Catmull, current president of Pixar Animation, a subsidiary

of The Walt Disney Company." In his book Creativity, Inc., he discusses the relationship

between the creative development of a story and the technical development of the tools

required to bring those stories to life. Within Pixar's unique and highly effective design and

management structure, the core tenant that story is valued above any and all other design

requirements is critical to Pixar's worldwide success.'2 Though there are so many important

practical and technical design requirements when writing and producing a spectacular, the most

important of those is that the creative narrative and story of the show be meaningful and

excellent. When making any design decision in regard to creative, technical, or producing details

of the show, this is the design requirement that would inspire any and all final decisions.

" Catmull, Ed. Creativity, inc. Place of publication not identified: Corgi, 2015. Print.

12 "The Financial Success of Pixar [Infographic]." Daily Infographic. N.p., 02 Mar. 2015. Web. 15 May 2017.

Chapter 4: The Narrative Design Process

The following section will describe and elaborate on the narrative design process of the show, Sparks of Hope. This will draw on the existing spectacular design processes. Each creative

and technical design requirement will be explained throughout the following sections.

4.1 Narrative and Thematic Exploration

The first step in the design process was to start brainstorming what major themes the

author wanted to explore in the show. This began with the researching of existing spectaculars

in order to establish narrative, tonal, and structural similarities between existing works and the

show. Figure 5 show structural narrative transcription and research carried out on existing

spectacular shows, Disneyland Forever and The Bicentennial Fireworks Show. This research

established a baseline structure by which the author could incorporate thematic intent.

53-3-, x lk'

. 4. I .3

04) Fi.d.

*'.3--Figure 5: Structural narrative research on existing spectaculars.

4.2 Thematic Selection

Once the basic narrative themes of the show were selected, the next step in the design

process was to select a main theme to explore throughout the show. This creative design

decision was made with the desired audience, the MIT community, in mind. The first thematic

concept was Journey and was meant to explore how individual members of society experience

their own journeys which happen to intersect at the moment of the show. However, the author

decided that this did not meet the critical design requirement of pertaining directly to the

audience's immediate experiences. With this decision in mind, the author turned to the theme

of technology, since this is the audience's primary field of study. An important tenant of

designing a spectacular is to empathetically consider where the audience has spent the time

prior to the show. In a Disney spectacular, they have spent their day experiencing magic in

various ways and are typically tired from an exciting day. With Sparks of Hope, the author

assumed the audience would primarily be technologists who spent their day in laboratories

studying and inventing technology, and thus settled on the central theme of technology.

riT T P-1s

Figure 6: Explorations of various themes and selection of techno/ogy

Once this central theme had been established, the author decided to add to it by incorporating the concept of humanness into the show. The author decided that they wanted the show to be about humanity and technology and the symbiotic relationship between the two from the dawn of technology to the modern era. Technology and humanity were chosen to serve as the two main 'characters' in the show which can be personified and symbolized through various production means.

4.3 Thematic Structure

The next step in the narrative design process was to establish a rough thematic structure

that progressed throughout the show. This was embodied by the selection of words that

represented each section of the show: nature, foundations, potential, balance, and hope. These terms served as the guiding principles for creative iteration within each section. From these

initial words, the author created a word and inspiration blast to further develop these themes

and the relationships between them, as seen in figure 7. These themes roughly divided the

show into five sections which could then be creatively iterated upon one by one.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ eA ~s.4e e

19M~ d .~ sf

Fiur 7: A1r- thmai bristrrod'wiebad

4. Se-ae Concep Art ,0r

Once W the , bscteaistutrhabentabihdoh uhr rae ocpr

image depicts moments in a scene mainly for the purposes of narrative development and for

pitching the show to producers, technicians, and other individuals involved with the process.

Figure 8: Concept art for the scenes of Sparks of Hope.

4.5 Concept Arranging

The next step in the process was to further develop each section of the show by

establishing the thematic concepts that were to be explained through the various production

elements. The design technique used for the step in the process was to write phrases, concepts,

or words down on scraps of paper and then organize them by scene in a roughly chronological

order. This technique allowed for a great deal of iteration and brainstorming in regard to the

order, length, and content of each scene. A graphic of this method is shown in figure 9.

E

CIL 1-Ka

Oa 4 On o'e-c\.' -I -C\~~~ VLC G r-"A0 Mj k d-e A c&n I '~ een " of o* n e '~oc~c1C r. IU.Sc re Nr* 'o/ me-,P

0.",

to CA ilc. IF.I

~> iU-.i ~. \. c..).C M rei~ P * -k eJo~ e& oi)

S cn 3U 4- o 4 7 -'- Ia mL' .- 1 ( U e- -exy/ i 1- -e, /

LTcooenUIf

h'C1An I oYY ht C 5b'A 'd

j

.

, 0M,

a

ecLnc

e~oA~ h~0 (~f ~ ~or eh~r oi n

b~e

.ose4 0FJOAIA 0" 60 Is c. .

0(,r rP Offo& A'I -- ______ osnslc b.O~aLI)I+/v ant4 (. ocs

e n y a --- -AO S he Cd--' do e 0 ;r T - y 'v: S y u se o bc -tD (Iv 4 c h V/ /0 IL o o <>/ ver'cJC1 Ngj~-e 0-)A '..Sr A s We C14 4 na Lr 1-i'~~ J0

v

L

ers f e(3 ve r -o an A" nci VI "4~C/ O.~:I JO ):e I's ~: C ;~~~ ' ' Fee, i5 -41

~

--Po '7 e 01) 0 -ci- .r /-I

O~5y

Figure 9: Concept ordering and brainstorming for each scene.

4.6 Narrative Outlining

After in-depth brainstorming on the thematic content of each scene, the author compiled those thoughts and ideas into prose. This design technique significantly helped narrow in on the creative intent of each section and served as a foundation upon which the author could base their other designs. Additionally, this allowed the author to document the established creative intent, as working out individual design details often leads to neglecting or forgetting the overall creative vision. Below is an excerpt from the prose narrative outline the author wrote after the previous step. This excerpt is the narrative outline for the first scene of

the show, Spark, and it details the creative and narrative intent throughout the scene in order of

appearance and flow.

Scene I: Spark

In the beginning, Nature gave rise to the human species.

For a long time, we existed at the mercy of our world in the great cycle of life.

Then with a single spark, fire was discovered over two million years ago and finally gave our species the ability to rise up, changing us forever

With this first technology, humans started to grow and move beyond pure survival.

This event marked the beginning of the symbiotic journey that humanity and technology would take together through time.

The history of the human species is the history of technology; every advancement in the human species is defined by the discovery or creation of a different type of technology.

With technology, we have taken control of the globe and built, brick-by-brick, the foundations upon which our civilization currently rests.

4.7 Storyboards

The next step in the narrative design process was to create visual storyboards of each

scene of the show. This involved drawing pictures with markers and pens on individual index cards. By the modular nature of this design technique, different visual cues and concepts could be rearranged throughout a scene. This process allowed for the streamlining of creative ideas and the creation of a specific visual and narrative outline. Figure 10 shows the conglomeration

of storyboards for the show.

SScene Scene 4 1

Scene I r : r r r en C3 uaandcene

Ad. dw

F ... .a V7. .. __________ *J-Ari Cg r ~ I. ~ik~ ____

~L -L4 IL I

4.8 Show Timeline

The next step in the design process was to create a more formal beat-by-beat plan of

each element of the show's narrative. This manifested itself through a handwritten outline of

the show and a drawn-out horizontal timeline of the show including the various scenes, critical

production element introductions, and other information important to laying out and planning

the narrative structure of the show. Figure 11 shows both an outline (left) and a horizontal

timeline (right) of the show. This was the last realistic step required before any technical

requirements could be defined.

Fi4g1 11: ne

k- J

4.9 Visual Inspiration

The next step in the design process was to assemble visual collages of research images

surround various key pieces of the proposed narrative. These images pulled from books, the

internet, and existing works and were compiled into collages. Figure 12 shows two such

collages. This design step was critical to settling on a visual tone for the show as well as giving

other members of the production team examples of the creative vision.

Figure 12: Research image collages.

4.10 Script Writing

The very last step of the narrative design was to formally write a script. This design step was completed by synthesizing all the narrative notes, outlines, storyboards, concept art, and

previous work into the form of a theatrical script. Below is an excerpt from the script describing the first scene of the show, Spark. Note that in addition to spoken text, the script includes visual, physical, sound, and music cues.

SCENE I - A SPARK Duration: approx. 2:00 min

VISUAL: Sunrise. Image of the sun coming up over the horizon.

MUSIC: The "Humanity" theme plays. It begins with the clicking of stones, sticks, and leaves,

turning into a light, floral, Celtic-inspired rhythm using organic instruments that encapsulates raw humanity.

VISUAL: Empty natural setting. SOUND: Primal daytime soundscape. MUSIC: "Humanity" theme continues.

FEMALE NARRATOR: The Earth, the place we have made our home, existed long before we set

our feet down.

VISUAL: Flares of flora and fauna on all projection surfaces. SOUND: Creaking of trees and woods, whistling of wind.

PHYSICAL: Fans blow wind across the audience members. Analog mechanical animations of growing flowers and trees, flying birds as puppets.

FEMALE NARRATOR: A marvelous ecosystem of flora and fauna, a cycle of life and death, a unique painting of all the universe's energy.

VISUAL: Colors shift from blues to dark tones and finally to black. Flashes of lightning,

projections of shadows of wolves, other dangerous animals, storms, etc. Strobe effects from moving lights.

MUSIC: "'Humanity" theme transitions to rhythmic primal drumbeat. Animal horns and human

calls are added throughout the progression of this theme.

FEMALE NARRATOR: We lived at the mercy of nature, the harsh winters, the brutal summers, the dangerous predators. Our nights were dark and cold, and we seemed merely another

species among millions.

SOUND: Rustling of leaves, striking of stones together, over and over and over, until a powerful

spark sound. A sonic roar offlame surrounds the audience.

VISUAL: Flames engulf all of the projection screens. Flashes of red, orange, and yellow spark

around balconies, ceiling, and columns. PHYSICAL: Obelisks glow with fire and light.

FEMALE NARRATOR: There was a spark.

VISUAL and PHYSICAL: The spark turns into a powerfulflame, turning into afire and light show,

signifying the birth of technology and our ability to rise above the rules of nature.

MUSIC: "Flame" theme, a woodwind melody, followed by a strong, rising orchestra, signaling

the spiraling of possibility, power, and wonder. A major tonal shift and key change conclude the scene and transitions to Scene II.

FEMALE NARRATOR: The first spark of technology that set our species on a singular journey through time and space to the population of seven billion we know today...

4.11 Musical Development

After the script, the most important creative element of the show is the musical score. The author worked with a composer to create the score for the show and to design each beat, note, and moment of the score to effectively and meaningly fit the narrative that had been designed. The author used visual drawings and timings to communicate the creative vision for the music to the composer. An example of this is shown in Figure 13. In the diagram, vertical position roughly represents pitch and horizontal position represents time. Orchestrations are sometimes marked or suggested and can be inferred or implied, depending on the competency of the composer. This served as a very effective means of communication.

~~ .E r S/.0

W) A

C6 C7 C

J t' 4of movers On, 14LC-f'

- --- - -calve . 3 eeI

C~

corelo " AeAFigure 13. Musical sketch for the opening of Sparks of Hope.

Chapter 5: Production Planning

Once the narrative had been established, there were several important production-level design decisions that needed to be made before full technical development of the show began.

5.1 Venue Selection

The first and most important technical decision was to select a venue at MIT where the show could take place. There were several creative and technical requirements established, all of which are explained in the following sections.

iSoe

At

p':,Hr-r -(

5.1.1 Creative Design Requirements

Design Notes/Explanation

Requirement

Campus The proximity of the venue to the center of campus was an important creative Location requirement; if the venue was too far from undergraduate or graduate housing, it is

likely that the audience size would suffer.

Indoor/ If the show were to take place outdoors, it would require a significantly larger technical Outdoor and financial investment since there are many practical concerns that are strenuous to

navigate. If the show were to take place indoors, it is critical to ensure the space is large enough and can hold the narrative and visual 'weight' of the show.

Existing Spectaculars often transform a physical space during the show. Therefore, if a venue Architectural has an architectural structure or character that can be used creatively and effectively Personality throughout the show, that venue will more greatly fill this creative requirement. The

'personality' of the space is a crucially important requirement.

Central Visual Focal Point

It is crucially important that the venue have a central or directional focal point in the space. It is important for the audience members to know where to direct their attention throughout the show and architectural features of the venue are able to do this.

Table 2. Creative requirements for venue selection.

5.1.2 Technical Design Requirements

Design Requirement Lighting Grid Power Availability Facilities Restrictions Storage

In and Load-Out

Time Availability Cost

Notes/Explanation

A lighting grid is a series of crossbars, and power and signal infrastructure that

allows for lights to be hung and powered without needing to build and design structures. This offers a great financial and logistical advantage.

With any large amount of lighting and automated equipment, it is critically important that the space be able to power all of the desired equipment.

Weights, designs, and locations of equipment and structures must be approved by facilities and EHS before they can be successfully implemented.

Since there is a large lighting rental, set elements, and other effects used in the show and the venue reservation will likely be for only a short amount of time, options for storing equipment both prior to and during the show are critical. It is critical that there are relatively easy means of loading equipment in and out of the space on the day in question.

The simplest technical requirement for the venue is that it be available for the proposed time of the show.

Based on the proposed budget of the show, it is critical that the cost of renting or reserving the venue is minimal or free.

Table 3. Technical requirements for venue selection.

Figure 14: Morss Hall in Walker Memorial Hall at MIT.

5.1.3 Venue Selection and Alternatives

There were several venues proposed for the production manifestation of this show which are shown in table 4. Ultimately, the author decided to use Morss Hall in Walker Memorial, as featured in figure 14. This option fulfilled as many of the creative and technical requirements as possible, compared to the other proposed venues, see table 4. The space was primarily chosen for its architectural character, time availability, free cost, larger size, central location, and production options of balconies, columns, extra spaces.

Advantages / Disadvantages

La Sala La Sala had a lighting grid, was large, centrally located, and was indoors. However, it lacked architectural character and was not available during the desired time.

Hayden Hayden Courtyard is the option the author would have chosen if the show Courtyard was planned to be outdoors. It is small enough to be realistic, though the

technical limitations of an outdoor venue were too great.

Killian Court Killian Court is where the author would ideally see the show with an unlimited budget. Its architectural character and production options are far greater than any other.

MTA Black The MTA Black Box is a new space that had a lighting grid, storage, Box lobby, and equipment. However, it is very far from campus and a black

box holds a 'theater' connotation that the author didn't want for the show.

Venue

Kresge Oval

Lobby 7

Advantages / Disadvantages

Kresge Oval was an intriguing option as an outdoor space. It is the most centrally located option though very complicated from a technical perspective and with no central visual focal point.

Lobby 7 was one of the initial choices for the show, since it is centrally located, has architectural grandeur and various options. However, the technical steps required to produce the show there were too great.

Table 4. Venue alternatives.

5.2 Budget Definition

This project was generously funded by several entities within the MIT community. In order to apply for funding, it was critical to synthesize all the technical and creative requirements into a form that could be converted to a budget, see figure 15. This process was critically important to defining the scope of the project in a practical sense and for determining what innovative ways the author could use existing equipment to lower costs.

Sparks of Hope Budget Note: This budget does not include any sales tax

Project title: Sparks of Hope: An Epic Spectacular on Humanity and Technology Please fi in the shaded clls where appropriate. Applicant's name Garrett Parrish

Date: March 5, 2017

Pr-ject Expenses Requ Cash Contributions (other mours) In-kind Contributiuns (other seurces)

Expense T9pe (matertalaisquipmentfees.etc.) Amunt from CAIT Source Amount Source Amount

1 Materials

2 Obelisk Base and Litt Materials (wood, aluminum, PVC, masonite, acrylic) $ 1,000.00 s 600.00 IDC, MIT Museum $ 400.00

3 Obelisk interior Ught Manipulation Matertals $ 500.00 $ 200.00 MIT Museum Studio $ 300.00

4 Hardware for Obelisk Moblity (casters, breaks) $ 200.00 S 200.00 $

-5 Heavy Duty Electric Drive Motors and other Electronic Driving Equipment $ 1,537.97 S 640.98 MIT Edgerton Center & Museum $ 998.99

6 Assorted Mechanical Hardware sprockets, gears, fasteners, mounting brackets)for Obelisk Drive Mechanisms (bearings, cabling S 500.00 S s 00.00 $

-7 Domes Materials for Obelisks (acrylic. fabric) $ 289.99 $ 289.99 MIT Museum Studio (2 of them) $ 200.00 Projection Systems

a Long-Range: projectiondesign cIneo3+ 1080 Projector $ 1,499.99 $ - $ MIT Museum Studio $ 1,499.99

9 Long-Range: 2x Panasonic PT-D4000U DLP Proc XGA Projectors $ 999.99 S - $ - MIT Museum Studio $ 999.99

10 Mid-Range:OBenO HT1075 -Portable 3D 1080p DLP Projector with Speaker $ 799.99 $ - S - MIT Museum $ 799.99

11 Mid-Range: Epson Brightink 450WI Projector $ 499.99 $ - $ - MIT Museum $ 499.99

12 Short-Range: BenQ MW855UST DLP Projector $ 1,299.99 $ - - MIT Museum Studio $ 1,299.99

13 Shod-Range: NEC WT600 DLP Projectors S 1,450.00- $ - MIT Museum $ 1,450.00

14 Assorted cabling (data and power) $ 300.00 $ - $ - MIT Museum Studio $ 300.00

i5 Lorg-Range: 20K Laser Projector Rental For Mural Wall (two weeks) $ 200.00 $ - $ Colleague $ 200.00

o6 10x Short-Range ASUS Projectors for Obelisks $ 2,690.00 $ - $ - MIT Museum Studio S 2,890.00

p7 Tripods and mounts for projectors S 400.00 5 150.00 Personal Contribution $ 60.00 MIT Music and Theater Arts $ 200.00 e 5x AUKEY HDMI SplItters (for Obelsk Projectors) $ 84.95 S 84.95 $ - $

-9 Scrim and Projection Material Rental from Rosebrand (one week) $ 740.00 $ 745.00

Figure 15: Budget excerpt.

5.3 Production Schedule Definition

With the venue and date selected, it was critical to establish a timeline of show design and production. The scheduling of various design, technical, and logistical elements was critical to the execution of a successful show. A production schedule (figure 16) was designed and often updated so as to ensure that the many interdependent aspects of the show were completed.

f

3/5-3/113/12-3/18 Theme Song Lyrics Completed

3/19-3/25 Obelisk Lift Mechanical Design Completed

3/26-4/1 Spring Break

4/2-4/8 Obelisk Interior Mechanism Design

4/9-4/15

4/16-4/22 Score Draft Completed, Scene V Music & Storyboards Complete

4/23-4/29 Schedule AV for Walker (MIT AV, MIT MTA, Cuco,

Ben, Media Lab) 4/30-5/6 Score Final Draft

Completed

5/7-5/13 Jamshied Orchestration/ Mixing Review, Theme Song Vocal Recording (Molly Roach, New York, NY)

5/14-5/20 Score Mixing and

Orchestration Completed 5/21-5/27 Light Programming and

Adjustment (in Mores)

CAMIT Grant Interview

Spring Break

Scene I Music & Storyboards Complete Scene III Music & Storyboards Complete

Digital Lighting Programming

Voice Over Record (Female Announcer)

Digital Publicity Launch (facebook, email, MIT

News, Boston Globe, Harvard, MIT)

Physical Publicity Launch (posters, fliers)

FULL-DAYINSTALL AND

SHOWS aflh-llfam

Scene IIVIV Narrative Development Complete Scene V Visual and

Timing Complete

PARTS ORDER FOR Full Show Storyboards OBELISK Complete (with

approximate timings) Spring Break Motion Design Schedule Obelisk 1,2 Interior

Completed Design Theme Song Lyrics

Completed

Projection Systems Scene IV Music & Design Finalization Storyboards Complete Technical Architecture, Walker Lighting Plot Place Lighting Cabling, Timing Control, Finalized Equipment Order, and Other Technical Schedule Rentals (ALP

Production Plans Soundwave)

Projector Procurement Script Completed Voice Over Copy (LOCKED)

Projection Set Up and DMX Lighting Simulation Testing (main) Complete

Theme Song Vocal MIT CopyTech Poster Recording (Ricky Printing Richardson -Cambridge, MA)

ALPS Lighting Rental Light Programming and LAST CLASSES, Light Pick-up (Canton, MA) Adjustment (in Morse) Programming and

Adjustment (In Morss) ALPS Lighting Rental Dismantling of Obelisks,

Retum (Canton, MA), Any remaining space Scrim Retum, MTA clean up, Returning of Equipment Return materials throughout MIT

S,

Production Design for all scenes completed

Spring Break

Obelisk 3,4 Interior Design Scene II Music & Storyboards Complete

Publicity Plan Detailing

Voice Over Record (Male Announcer)

Script Finalized (LOCKED), Projection Set

Up and Testing (west

balcony)

THESIS DUE

Light Programming and Adjustment (in Morss)

Scene 1IIV Narrative Development Complete Theme Song Music Completed Spring Break

Obelisk 5 Interior Design Obelisk 1 Complete Obelisk 2 Complete

Jamshied Score Review, Obelisk 3 Complete

Obelisk 4 Complete, Projection Set Up and Testing (east balcony) Score Timing Finalized (LOCKED), Obelisk 5 Complete

Full Content Stumble Through (video, lights,

sound, effects)

Light Programming and Adjustment (in Morms)

Figure 16: Production schedule defined for the project.

5.4 Design Management Techniques

It was critical to devise a task management paradigm to manage so many disparate design processes. The design and management technique used was a universally accessible spreadsheet with all the necessary information included on it, shown in figure 17. The left-most column features the 'narrative beats' in sequential order. Each successive column to the right details a different production element (lights, sound, etc.). This technique effectively coordinated personnel, technical development, and content design and creation.

OUON UbqIWM tue

,,...,MM .... ,lw H.us.h~swt

'F SHM -.. .t.t.

Male a.nincer OWW"p"d o Noum n g on Male -nnunc, Dipped volum- H--s Igts n

O.A-es Sudde- f-,

11scoonrk 18-05 Cok-m 400i on Modwama sounds, me Ekadon Mo 0r on

Fonamk womer ,d XM NOW'l On 25 minube announowmnis 20 ite FAnnnomnt ACT I ColuMrn on1thtg gUtlmovensyms on S-0l CORE P40ht n

Nig CORtE Uighs -n ArrWva (1pbo box Wt)

Dectarotion ofthessofsho Earth -Earfy hurnan h"Mr v

Figure 17: Management spreadsheet for the project.

Chapter 6: The Technical Design and Implementation Process

In parallel to the creative development of the show, there were several technical design

and implementation designs to be completed for effective show execution.

6.1 Production Specifications Specific to Chosen Venue

With the selection of Walker Memorial Morss Hall as the venue for the show, it was

critical to establish some basic production specifications for the space. Figure 18 shows a crucial

element of the space: the balconies situated on the right and left. These balconies served as

excellent locations for projectors and lights in addition to a means by which to hang projection

surfaces. However, there were several weight and positioning requirements to be considered.

Figure 18: Morss Hall balconies.

35 of 47 Orch....lh....uQd or , csePOpOtAr 041ped vo -m Dimped-vlume D hm 4 hit ShitsU U embW (ODO .IM 'g'%.- &1Wdo. m wm -Anthss2- w+prmd Anhm3-grand rnafor chord Fkawte op to twwnifnt Ught undlersCoffn ,n.,..t.,. dep...-.e --Mfht tow swd oansh wagnmhs gnt --Abonrac vhWulEUons M I = Almo d' GmsOf Swarguaosonaceftg Cobos on cftig

The second crucial architectural element of the hall is the large painted canvas mural on the North wall, which provided an excellent opportunity for a projection surface. It is rare that an indoor room has such a large, flat, and dark-colored wall that serves as the central focal point of the architecture. Figure 19 shows the main mural as well as two thinner murals located on the opposite side of the hall.

Figure 19: Morss Hall murals.

The last crucial architectural elements, shown in figure 20, of the hall are the columns, ceiling, and large open space in the middle of the hall. The columns flanking either side create the illusion of a bigger space, something that can be used to great emotional effect. Additionally, the ceiling is mostly made out of white plaster which allows it to be effectively lit from below using various lighting fixtures. Finally, the sheer size of the hall (52'x96') allows for

audience members to situate themselves throughout the hall and allows for the placement of a

large central structure in the center of the space.

6.2 Production Element Definition

The designed narrative structure of the show could certainly be implemented at various

levels of scope, budget, and personnel count. However, based on the practical constraints

imposed by the circumstances of the project, an important step in the design process was to

narrow down the scope of the project and define what the main production elements of the

show were going to be, based on availability, time requirement, budget, and creative

requirements. The following production elements were defined for the proposed show:

" A computer-based control architecture for controlling and timing all show elements " Sound and music (via a speaker array placed around the hall)

" A central structure that serves as the visual and narrative focal point " A significant number and variety of stationary and moving light fixtures

" A series of projectors and projection surfaces strategically placed around the hall

6.3 Sound Systems Design and Placement

With the important creative requirement of a musical

score, an equally critical technical requirement is the use of an

effective sound system to hear that score. Figure 21 shows a

working document the author used to design the sound

systems and placement for the hall. This was done in conjunction with the AV rental company, MIT AV, and other

technical advisors on the project. Speakers were placed at

eight strategic positions around the hall, for a total of twelve

speakers which processed six unique channels of sound. Figure 21: Sound systems Design

37 of 47

. c

6.4 Central Structure Design

One of the main creative requirements specified was to have a singular central structure

that serves as the focal point for the show. This structure would 'come alive' with various

elements such as fans, lighting, and performers. The first step in the design process for this

structure was to draw sketches of its narrative function, featured in figure 22.

Figue 2: Cocep skeche for Jentas bet

4 0

Following these sketches, the next step in the design process was to build a small-scale

prototype focusing on visual and mechanical functions. The author designed and constructed a mechanical version of the obelisk, seen in figure 23, which effectively tested visual concepts, evaluated technical feasibility, and began the process of collecting the equipment required for the assembly and certification of a production-level version.

<t- /~~'t

~

J

F,, Lr ~~ciJ

'II

9Figure 23: Prototype obelisk and design sketches/schematics.

After this prototype had been designed, constructed and tested, the next step was to

convert the technical design of the prototype into a full-scale construction that could be built

using existing safety-approved structural members, lights, and effects. This design conversion

process was particularly challenging and rewarding as there are only a set number of equipment

types and pieces that the author was able to rent and thus had to alter the design accordingly in

order to accommodate those constraints. Figure 24 shows graphical hand-drawn sketches of the

central structure design process in addition to a VectorWorks rendering of the final structure

that was designed. These designs were then used to inform the rental companies on which

pieces of truss, lighting equipment, and other effects needed to be rented.

39 of 47 42

C.~.~s~jI~j~ / \.3 ~ ~ .~A 1 I 7--16 e ~{~ S\ t4

L

I11:

Figure 24: Production-level central structure truss design.

6.5 Lighting Design and Placement

The largest technical segment of the show's design was the lighting systems. In a production of this scale, moving lights and traditional fixtures provide a high yield-to-investment ratio that is critical when working at a small scale. Figure 25 shows working lighting design, positioning, and cataloging throughout the design process. Furthermore, table 5 shows the final design of the lighting systems for the show, depicted in a list.

nf ~ U U 11 I 00 0 ~ C30 rnLIn ?-110 p4A(al