Americanaaaaaaa!

A Welcome Home

in Lowell, Massachusetts

or

by

Alexander BodkinHonours Bachelor of Architectural Studies University of Waterloo, 2014

Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

February 2019

©2019 Alexander Bodkin. All rights reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to

distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created.

:

Signature of Author:

Department of Architecture January 17, 2019

Mariana Ibañez Assistant Professor of Architecture

Thesis Supervisor

Nasser Rabbat Aga Khan Professor Chair of the Department Committee on Graduate Students Certified by:

Committee

Readers Supervisor

Timothy Hyde Associate Professor of the History of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Hashim Sarkis Professor of Architecture Professor of Urban Planning Dean, School of Architecture and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Mariana Ibañez Assistant Professor of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Thesis was a strange and wonderful process that allowed me to explore numerous

interests towards the creation of something wholly unexpected. It would not have been possible without the guidance and labour of many friends and mentors.

Mariana Ibañez, thank you for supporting this work from our very first meeting and for remaining exceptionally committed throughout the process. My thesis and my broader educational development have benefited greatly from your openness and energy.

Timothy Hyde, thanks for bringing clarity and confidence to this thesis when it was most needed.

Hashim Sarkis, you have an unparalleled ability to deliver wisdom with precision, regardless of how sparse or how cluttered a presentation is. Thank you.

Friends both new and old supported the intellectual and material development of this thesis. Without them, I would not have crossed the finish line. Charlotte D’Acierno, you’re a model-making hero. Thank you for working diligently over so many days. I owe you.

Paul Mayencourt, thank you for your woodworking skills, all the coffee runs, and your admirable work-life balance.

Sam Ghantous, thank you for the thoughtful crits, the links and articles, and for making all of the beautiful printed matter. Daniela Leon, thank you for reassuring me during one of the earliest discussions of this thesis, and for driving in from New York to wrap up the final model.

Eytan Levi, you joined in right when I needed you. Thanks for staying positive and sticking it out until 5am for the final push. Will Fu, thank you for making so many delightfully childish drawings with so little guidance. Ben Hoyle, thank you for helping with the model when all I had were piles of laser cut material. Miguel Sanchez Enkerlin, thanks for your encouragement throughout this process and your assistance with printed matter in the final days.

Dalma Földesi, thank you for taking and processing key photos of the model while it was still being built.

Alice Song, thanks for doing early morning laser cutting in between your own deadlines. Yaara Yacoby, thank you for the initial hand drawings and your help assembling miniature things.

Above all, thank you to Sarah Gunawan, for everything, but also for being an intellectual ally, a motivator and organizer, an expert model-maker, and a thoughtful critic.

Abstract

This thesis studies how nostalgia has been used to construct shared spatial and social expectations through the envelope of the American home. Then, based on the simple proposition to make the home bigger so that it might host a broader collective, it explores how these expectations can be subverted through distortions and exaggerations of the domestic envelope. As these exaggerations reach the limits of symbolic legibility, they begin to suggest alternate internal organizations which have the potential to shape the social relationships and negotiations of a new collective within.

The site for this thesis is

Lowell, Massachusetts, a once-prosperous textile mill town on the Merrimack River. Lowell is chosen for two of its defining features: its robust preservation campaign, which perpetuates a flattened representation of Lowell’s collective identity that is rooted in a 1970s idea of 19th century domestic architecture, and its long history of immigration – today, approximately one quarter of Lowell’s population is foreign born.

These conditions provide an opportunity to appropriate Lowell’s own nostalgia in the design of a new civic building – the Welcome Home – that serves a broader collective of local and newcomer.

Americanaaaaaaa!

A Welcome Home in Lowell, Massachusetts

by

Alexander BodkinSubmitted to the Department of Architecture on January 17, 2019 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture

Thesis Supervisor: Mariana Ibañez Title: Assistant Professor of Architecture

Committee

Acknowledgements Abstract

Part One: Positioning

A is for Americana N is for Nostalgia L is for Lowell Proposal Manipulations on Images of Elevations

Part Two: A Welcome Home in Lowell, Massachusetts Overview Food House School House Hangout House Work House

Large Hand Drawing Five Documents

Part Three: Back Matter

Final Review Process References 3 5 9 15 25 35 41 51 71 91 103 121 135 147 159 183 193 247

Contents

Positioning

A is for

Americana

Americana are pervasive and familiar artifacts that both shape and are shaped by American culture. These artifacts are preserved

in individual collections and collective

imaginations, allowing them to exert influence across scales. They often operate as nostalgic reminders of a previous era, using a variety of mediums to recall incomplete and idealistic versions of America.

Interest in exploring these populist objects has varied over time, but today, political anxieties around identity and nationalism provide a

renewed opportunity to unpack Americana within the context of architecture.

One vehicle for unpacking this phenomenon is the American home. Not the sprawling suburb or the downtown condo, but perhaps the one that— whether we like it or not—continues to stand in for the idea of the American home.

Viewed from the street, each one is a discrete, private entity, which together form a collective through the repetition and recombination of a shared architectural language: roofs, clapboard, dormers, turrets, bay windows, porches, gables, paint, lawns, and so on.

Figure 1. Illustrations of some

characteristics of the American home’s shared architectural language.

Figure 2. 48 Wannalancit St,

Wannalancit Street, Lowell, MA Figure 3. 245 Gibson St, Tyler Park, Lowell, MA

Figure 4. 101 Livingston Ave,

Livingston-Harvard, Lowell, MA Figure 5. 396 Pine St, Tyler Park, Lowell, MA

Figure 6. 209 Nesmith St, Rogers

Fort Hill Park, Lowell, MA Figure 7. 324 Andover St, Andover Street, Lowell, MA

Figure 8. 344 Wilder St, Wilder

Street, Lowell, MA Figure 9. 43 Nicollet St, Livingston-Harvard, Lowell, MA

Figure 10. 25 Fairmount, Belvidere

Hill, Lowell, MA Figure 11. 408 Pine St, Tyler Park, Lowell, MA

Figure 12. 89 Harvard St,

Livingston-Harvard, Lowell, MA Figure 13. 366 Andover St, Andover Street, Lowell, MA

This home operates as a backdrop for the everyday rituals of American domestic life. Kitchen arguments, basement hangouts, backyard barbecues, lawn care, neighbourly small talk, front door deliveries, flag raising, evenings on the porch—all of which reinforce ideas about who rightfully lives in America and how they ought to act.

Figure 14. Illustrations of some

elements of American domestic life’s everyday rituals.

Figure 15. Still from The Fast and

the Furious. Figure 16. Still from American Beauty.

Figure 17. Still from The Royal

Tenenbaums. Figure 18. Still from Moonrise Kingdom.

Figure 19. Still from Ferris Bueller’s

Day Off. Figure 20. Still from Wayne’s World.

Figure 21. Still from Ferris Bueller’s

Day Off. Figure 22. Still from Home Alone.

Figure 23. Still from Forrest Gump. Figure 24. Still from My Blue

Heaven.

Figure 25. Still from It’s a Wonderful

Life. Figure 26. Still from Home Improvement.

Even if we don’t have this home, and we don’t have its associated rituals, it seems to still be the focus of a collective nostalgia, and so we legislate its preservation, and we attempt to reconstruct it.

The earliest definition of nostalgia (in 1688) was as an acute homesickness. This sense of homesickness underlies Svetlana Boym’s

contemporary definition of restorative nostalgia, which is a longing for an idealized era (however fictional) paired with a desire to actively maintain or reconstruct that time period today.1

N is for

Nostalgia

1. Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Figure 27. Scanned cover pages

of three reports from the Lowell Historic Preservation Commission.

In order to revisit a previous time through space, this nostalgia does not need to create exact spatial replicas. Instead, it aims to recall memories by flattening legible architectural characteristics into familiar compositions that are viewed from the street.

One example of this nostalgia can be found in Lowell, Massachusetts, a once-prosperous textile mill town on the Merrimack River whose monopoly over cotton textile production fell apart in the 1920s as labour and electricity became less expensive elsewhere. In the 1960s, citizens developed a plan to culturally and economically revive Lowell by turning their downtown into the Lowell National Historical Park, an urban national park operated by the National Parks Service that capitalized on the city’s 19th century architectural history.

The Lowell Historic Preservation Commission was established to develop and implement a robust preservation campaign, which eventually spread from the park downtown to the

surrounding domestic neighbourhoods.

In doing so, Lowell operationalized nostalgia to construct a collective identity through the elevations of the American private home. This continues to be enforced by the Lowell Historic Board (which was established in 1983 to succeed the Lowell Historic Preservation Commission as the city’s historic preservation agency), a network of ten Neighbourhood Design Review District boards, and a set of design

guidelines. It has also become self-reinforcing, as neighbourhood associations form to apply political pressure and contractors become fluent in the architectural language.

Figure 28. Scanned cover page

of “The Lowell Neighborhoods,” a report that extends the National Park Service’s 1979 architectural, historical, and planning survey of the downtown Lowell Historic Preservation District out to the rest of Lowell’s neighbourhoods.

Figure 32. Scanned cover page of

“Lowell: The Building Book,” which contains information on Lowell’s architecture and recommendations

for its preservation. 2. ibid.

But why care about all of this? The following quote from Svetlana Boym gives us some guidance:

“It is the promise to rebuild the ideal home that lies at the core of many powerful ideologies of today, tempting us to relinquish critical thinking for emotional bonding. The danger of nostalgia is that it tends to confuse the actual home with an imaginary one. … Unelected nostalgia breeds monsters. Yet the sentiment itself, the mourning of displacement and temporal irreversibility, is at the very core of the modern condition.” 2

Nostalgia is inescapable, but it isn’t fixed. It is a creative act that can be operationalized

towards different ends. Perhaps nostalgia can be appropriated to challenge and expand what the American home is, what it means, and who gets to live in it.

To do so requires beginning with the domestic envelope, and designing from the outside in. This thesis studies how nostalgia has been used to construct shared spatial and social expectations through the envelope of the American home.

Then, based on the simple proposition to make the home bigger so that it might house a broader collective, it explores how these expectations can be subverted through distortions and exaggerations of the domestic envelope. As these exaggerations reach the limits of symbolic legibility, they begin to suggest

alternate internal organizations which have the potential to shape the social relationships and negotiations of a new collective within.

Figure 33. Scanned and redrawn

page from “Lowell: The Building Book,” which shows how Lowell prioritizes the front facade and its architectural characteristics in their conception of the American home.

Lowell was chosen as a site to test this thesis for its two defining features.

First, the robust preservation campaign that I have already spoken about, which perpetuates a flattened representation of Lowell’s collective identity that is rooted in a 1970s idea of 19th century domestic architecture.

Second, an extensive history of immigration, which provides an opportunity to interrogate Lowell’s nostalgia and its implications through the lens of the newcomer.

L is for

Lowell

Lowell was founded in 1821 as a planned

industrial city. By the 1850s, it grew to become the second largest city in Massachusetts and the world’s largest producer of cotton textiles. The city’s mills and their associated dams and canals for hydroelectric power generation were built and later run by a largely immigrant workforce.

Housing blocks, social institutions, and other urban amenities were constructed alongside the mills, and a central business district emerged as commercial activity was drawn up from Boston to serve the growing population. Ethnic enclaves formed over time, and their inhabitants established institutions such as schools and churches that operated in their own native languages.

Figure 34. Map of Lowell’s ethnic

districts as of 1912, from George F. Kenngott’s “The Record of a City, A Social Survey of Lowell Massachusetts,” The Macmillan Company: New York, 1912.

Figure 35. Demographics of Lowell.

Sources: Gibson, Campbell and Kay Jung. Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850 to 2000.U.S. Census Bureau, Feb. 2006.

Kenngott, George F. The Record of a City, A Social Survey of Lowell Massachusetts. The Macmillan Company: New York, 1912.

0 20k 40k 60k 80k 100k 120k 2000 1980 1960 1940 1920 1900 1880 1860 1840

Total Population of Lowell

Foreign-born Population of Lowell Percentage of Population Foreign-born

44% % 8% 25% 0 20k 40k 60k 80k 100k 120k 2000 1980 1960 1940 1920 1900 1880 1860 1840

Total Population of Lowell

Foreign-born Population of Lowell Percentage of Population Foreign-born

44%

%

8%

25%

Total Population of Lowell Foreign-born Population Foreign-born Population as Percentage of Total

By the 1900s, 80 percent of the city’s population were immigrants or the children of immigrant parents.

As Lowell’s economy declined from the 1920s onward, so too did its immigration rate. The Immigration Act of 1924 reinforced this trend by restricting the number of immigrants to the US from certain countries and enforcing a ban on non-white immigrants.

These measures were later countered by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which eliminated the national-origin quotas from 1924 and helped shift the demographic makeup of the United States as immigrants came increasingly from Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

In the 1970s, Lowell became the site of

resettlement for 25,000 Cambodian refugees, reinvigorating and intensifying Lowell’s legacy as a city of immigrants.3 Based on data from 2016, Lowell has a population of 110,500, of which 25.7% are foreign born.

3. Mills, Robert. “City, UMass Lowell recognize contributions of immigrants with display of art, stories.” Lowell Sun, 14 April 2014.

Proposal

This condition of immigration provides an opportunity to appropriate Lowell’s own nostalgia in the design for a new collective that is situated at the intersection of local and newcomer.

Welcome Home

International Institute of New England

The Community Family Elderly Day Care Center The Acre Neighborhood District 236 Broadway St Welcome Home Int ernational Ins titut e of Ne w England The Community F amil y Elderl y Da y Car e Cent er The A

cre Neighborhood Dis

tric t 236 Br

oadw ay St WelHomecome

Int ernational Ins titut e of Ne w England The Community F amil y El derl y Da y Car e Cent er The A cr e Neighborhood Dis tric t 236 Br oadw ay St W el come Home International Institute of New England

The Community Family Elderly Day Care Center

The Acre Neighborhood District 236 Broadway St

Welcome Home

Figure 36. Stakeholders for the

Welcome Home.

This thesis proposes a new civic building called a Welcome Home that acts as a hub for newcomer services and amenities, while also providing locals with new community space as well. To do this, the Welcome Home engages with existing institutions in Lowell. These are, on one hand, the International Institute of New England, an active newcomer assistance organization, and the Community Family Elderly Day Care Center, a senior center.

Figure 37. Map of the

Neighbourhood Design Review Districts in Lowell, MA.

A B C D E K H G I J F

A. Downtown Lowell Historic District B. The Acre Neighborhood District C. Andover Street Neighborhood District D. Belvidere Hill Neighborhood District E. Livingston-Harvard Neighborhood District F. Rogers Fort Hill Park Neighborhood District

Welcome Home

G. South Common Neighborhood District H. Tyler Park Neighborhood District

I. Wannalancit Street Neighborhood District J. Washington Square Neighborhood District K. Wilder Street Neighborhood District 44

Potential sites were considered that shared certain characteristics: all of them were within one of the Design Review Districts, which

manage preservation in Lowell; they all were in predominantly residential zones but were

adjacent to existing institutions, like an American Legion, a Church, and a School; and they all

had multiple street-facing sides, which offered multiple approaches to the project.

The final site chosen for this Welcome Home sits at the edge of The Acre, one of the first Neighbourhood Design Review districts established and one of the oldest neighbourhoods in Lowell.

In The Acre, more than 24% of neighbourhood residents are immigrants from Southeast Asia (mostly Cambodians), and another 26% are Hispanic.

Figure 38. Map of The Acre

Neighbourhood Design Review District, with the site of the Welcome Home emphasized.

Welcome Home

The Acre Neighborhood Design Review District

This site was chosen for a number of its characteristics:

1) The site occupies just over half of a residential block, and therefore presents an opportunity to test the domestic language at a larger scale.

2) There are five small existing gable

front homes on the site, some of which were constructed in 1890 and others of which were constructed in 1980. This presents an opportunity to work with existing types and conditions, to test what remains and what is exaggerated, to challenge (but not destroy) the sanctity of the house.

3) It has four sides—the west, facing larger commercial buildings and the elderly day care center; the north, facing the backside of main street residential buildings; the east, facing a residential street; and the south, facing a playground and residences. These present an opportunity to design for multiple street-facing approaches or “principal facades.”

47 47

Elderly Day Care Center Mediterranean Bakery Latin Grocery Store Playground

4) Given its location between different scales and types of building, it presents an opportunity to explore the tension between the domestic and the institutional.

5) Its relevance to the narrative of immigration within Lowell presents an opportunity to think of architectural context not just as immediate physical fabric but also as something historical and social—and therefore to extend the

arguments of architecture into these realms as well.

Figure 39. Plan view of the site for

the Welcome Home, with nearby locations labeled.

Manipulations on

Images of Elevations

These opportunities and challenges were all first explored through manipulating screenshots of elevations of homes in Lowell. These elevations were not specifically from the Welcome Home’s site in The Acre, but instead from across Lowell’s design review districts.

The tests looked at things like the relationship between roof and ground to introduce a design methodology that worked from the outside-in and began to suggest new spatial possibilities internally.

Figure 40. Before and after, 56

Huntington St, Rogers Fort Hill Park.

Other tests included delaminating the cladding...

Figure 41. Before and after, 52

Franklin St, The Acre.

Repeating and extending the porch to connect two separate homes...

Figure 42. Before and after, 67

Harvard St, Livingston-Harvard.

Stretching volumes until they push past the property lines...

Figure 43. Before and after, 209

Nesmith St, Rogers Fort Hill Park.

Distorting the relationship between lawn and building…

Figure 44. Before and after, 98

Huntington St, Rogers Fort Hill Park.

Manipulating proportions of the roof...

Figure 45. Before and after, 93

Chestnut St, Washington Square.

Exaggerating volumes...

Figure 46. Before and after, 43

Nicollet St, Livingston-Harvard.

And voiding expected conditions.

These exaggerations and distortions toed the line between generic and specific, attempting to invent spatially and open up the elevations to new readings while also still remaining legible enough to participate in Lowell’s world of nostalgia.

The territory of this thesis is within these tensions—the tension between nostalgic and new, between domestic and institutional, etc.— but never with the aim of resolving them.

Figure 47. Before and after, 89

Harvard St, Livingston-Harvard.

A Welcome Home

in Lowell, MA

Overview

The Welcome Home exaggerates and distorts the architectural language of Americana in Lowell as it expands the five existing gable front homes on the site to host the broader collective of

newcomers and locals.

Its final design is presented primarily through a four-part model, with each part corresponding roughly to a zone of the Welcome Home. The model is 1:25 scale, large enough to achieve the feeling of a dollhouse or a model train set and thus begin a dialogue with the mediums of nostalgia.

Figure 48. South and east

Food House

Figure 49. West elevation.

These four zones are sometimes discrete and sometimes overlapping, and can be understood as we move around the model.

In the Food House, the layers of the building are delaminated to make space for an oversized shared kitchen and greenhouse. The balloon

frame of the old house sits in and supports these new uses.

Figure 50. South elevation.

School House Food House

In the School House, classrooms for after school programs and language exchanges are packed inside two of the existing homes. This pressure shifts the floorplates off of their expected

heights, thus confusing and challenging the expected vertical order.

Figure 51. East elevation.

Hangout House School House

In the Hangout House, one of the existing home’s volumes is enlarged until it hits another existing home, creating a large double pitched hall on the upper floor, and a series of small living rooms on the ground floor, all of which could be used for socializing, game nights, and performances.

Figure 52. North elevation.

Work House Hangout House

The Work House is the only zone that does not contain an existing house within its footprint. As such, it extends the roofline and foundation from elsewhere, and omits the “middle floors” to connect basement with attic. Offices for civic services, coworking spaces, and a small workshop are all under one roof here.

Figure 53. Aerial from south-west

Figure 54. Aerial from north-west corner. Food House School House Hangout House Work House 84

Designing from the envelope inwards presents a challenge when one arrives at the middle of the building. In this case, the front of the American home—the lawn—is placed in the centre of the Welcome Home, accessed by passages

under inverted pitched roofs and surrounded by covered walkways and porch spaces.

This formerly private block and its five discrete homes are transformed into something more porous, more ambiguous, sometimes one building and sometimes many.

Figure 55. Simplified ground

floor plan with annotations and reminders.

A second nostalgic medium is introduced into the thesis presentation through the plans, which simplify orthographic drawings in an attempt to achieve legibility by a wider audience. Small annotations in coloured pen suggest the daily activities of a recent visitor.

Figure 56. Simplified first floor plan

with annotations and reminders.

The ground floor has a number of passages from the surrounding streets through to the central lawn which break up the Welcome Home. The first floor bridges over many of these passages to link the different zones back together.

Figure 57. Drawing of upper floor of

Food House filled with plants.

Food House

In the Food House, the layers of the existing house are delaminated to make space for an oversized shared kitchen on the ground floor and a greenhouse on the first floor. The outer clapboard layer becomes a screen that bends down towards the street, obstructing the glass walls behind. The exposed balloon frame of the old house filters light deep into the kitchen and supports the greenhouse’s new structural members. The staircase slips between wall

layers. A wood burning cooking stove pipes warm air up through the glass chimney.

Figure 59. The clapboard screen

plays a hide-and-seek game between the Food House’s inner glass skin and the street-level viewer.

Figure 60. Interior view of model

Figure 61. Drawing of Food House

filled with plants from underneath the School House’s entrance.

Figure 63. The sunken kitchen

fills the ground floor and uses foundation walls as counter space.

Figure 64. Outdoor eating area

surrounded by clapboard fence and an overhang above.

Figure 65. Upper floor greenhouse. 101

Figure 66. Drawing of School

House’s east elevation.

School House

Two of the existing homes are merged and

altered to form the School House. Classrooms for after school programs and language exchanges are packed inside the original volumes. This pressure shifts the floorplates off of their

expected heights, sinking some into the ground and pushing others higher into the air. Challenges to the expected vertical order are revealed

briefly when a floorplate’s edge is seen crossing the midpoint of a window, and again when the clapboard cladding peels up.

Figure 67. On the east elevation, the

clapboard cladding lifts up to reveal vertically displaced floor plates, and the roof wraps down to make an entrance to the central lawn.

Figure 68. View from the east

through the glazed stud wall to a sunken reading room.

Figure 69. The School House’s south

elevation more clearly reveals how floorplates are vertically displaced within.

Figure 70. South entrance, with a

view through to the central lawn.

Figure 71. Ground floor of the

Figure 72. Attic floor of the School

Figure 73. Drawing of a foreign film

night at the School House.

Figure 74. Raked seating space.

Figure 75. Selective removal of wall

cladding creates unexpected views through the School House.

Figure 76. Chairs stowed away when

Figure 77. First floor classroom,

with mats and stools left over from an earlier session.

Figure 78. First floor classroom.

Figure 79. View through the inverted

roof entrance to the central lawn.

Figure 80. Drawing of the School

House from the central lawn. The raked seating space is visible through a window on the left, and the covered porch space is visible on the right.

Figure 81. Drawing of the covered

porch space.

Figure 82. The School House’s porch

space is covered by an extended roof above.

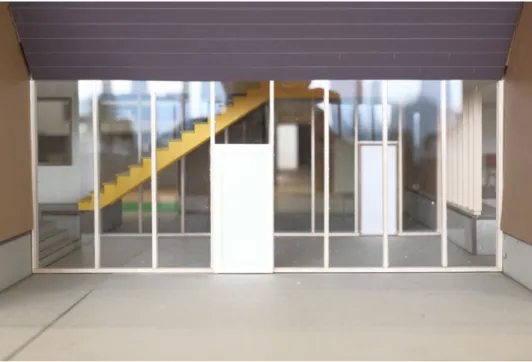

Figure 83. Drawing of the Hangout

House’s east elevation. The

clapboard screen lifts up to protect a seating area made from two of the original home’s foundations. It also reveals an exposed stud wall clad with polycarbonate panels and makes space for a yellow stair hidden behind.

Hangout House

In the Hangout House, one of the existing home’s volumes is enlarged until it hits another existing home. The resultant double pitched large hall on the upper floor and low long living room on the ground floor both sit behind a clapboard screen. This screen peels in multiple directions to

provide cover on the sidewalk and to make space for circulation.

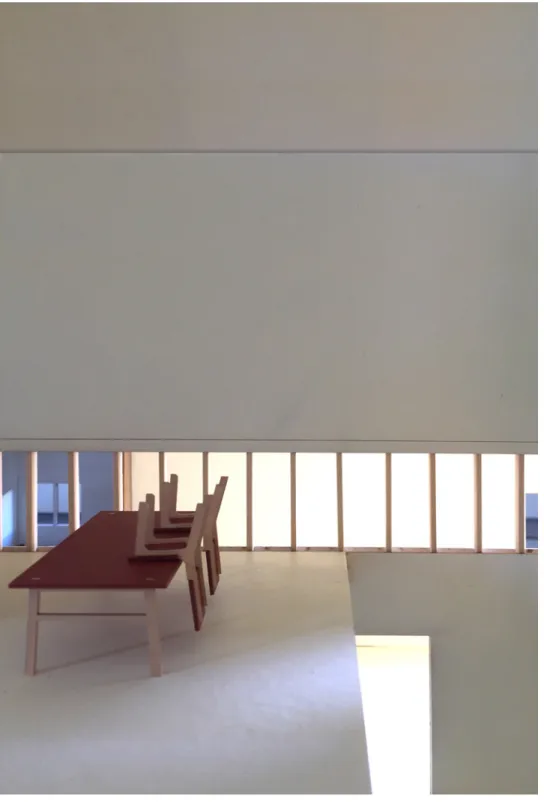

Figure 86. The large hall on the first

Figure 87. Clapboard screens along

Figure 88. View from the stairwell

through the large hall.

Figure 89. The stairwell between

the School House and the Hangout House.

Figure 90. The covered walkway

facing onto the central lawn.

Figure 91. Ground floor living room,

broken up by large scale furnitures.

Figure 92. The covered walkway

and ground floor living room as seen from the central lawn.

Figure 93. Drawing of the Hangout

House as seen from the central lawn.

Figure 94. Hangout House’s west

elevation.

Figure 95. Drawing of the Hangout

House’s west elevation.

Figure 96. Drawing of the Work

House’s west elevation and the west entrance to the central lawn.

Work House

The Work House is the only zone that does not contain one of the five previously existing homes within its footprint. It connects basement to attic by extending the roofline and foundation from elsewhere and omitting the typical “middle floors” of a house. Typically sites of excess,

storage, and memory, the basement and the attic become new offices for civic services, coworking spaces, and a small workshop.

Figure 97. Work House’s west

elevation and the west entrance to the central lawn.

Figure 98. West entrance to the

central lawn.

Figure 99. North elevation of the

Work House. The clapboard cladding wraps up to become a roofing material, while the foundation extends upwards to enclose the ground floor and support the roof.

Figure 100. Drawing of the north

elevation.

Figure 101. A void in the foundation

wall brings light to the ground floor.

Figure 102. Aerial of the Work

House.

Figure 103. The stairs slip between

the clapboard layers and the solid ground floor walls.

Figure 104. The large roof floats

above the first floor, creating a linear circulation route between the roof edge and the vertical structure.

Figure 105. First floor coworking

space. Someone is building a scale model of a house.

Figure 106. Drawing of the

coworking space.

Figure 107. Multi-part hand

drawing of the Welcome Home, its surroundings, and a sampling of possible narratives from the people around it.

Large Hand Drawing

A large hand drawing comprised of five

overlapping sheets presents the Welcome Home within The Acre neighbourhood. The surrounding physical context is rendered to varying degrees of detail. Annotated vignettes are scattered throughout the drawing.

Figure 108. Crop of the multi-part

Figure 109. Crop of the multi-part

Figure 110. Crop of the multi-part

Figure 111. Crop of the multi-part

Figure 112. Crop of the multi-part

Figure 113. Five documents stacked

Five Documents

Five documents were produced to connect portions of the thesis research to the final presentation of the Welcome Home. These documents riff on the bureaucratic graphic language and formatting used by small public institutions like those in Lowell.

Figure 114. American Domestic

Life booklet, with 12 screenshots from popular American movies and television shows that communicate the rituals of everyday domestic life.

Figure 115. American Domestic

Life booklet, with 12 screenshots from popular American movies and television shows that communicate the rituals of everyday domestic life.

Figure 116. American Domestic

Life booklet, with 12 screenshots from popular American movies and television shows that communicate the rituals of everyday domestic life.

Figure 117. American Domestic

Life booklet, with 12 screenshots from popular American movies and television shows that communicate the rituals of everyday domestic life.

Figure 118. Elevation Elements

booklet, with 31 images highlighting different characteristics common to home elevations in Lowell, MA.

Figure 119. Elevation Elements

booklet, with 31 images highlighting different characteristics common to home elevations in Lowell, MA.

Figure 120. Elevation Elements

booklet, with 31 images highlighting different characteristics common to home elevations in Lowell, MA.

Figure 121. Elevation Elements

booklet, with 31 images highlighting different characteristics common to home elevations in Lowell, MA.

Figure 122. Welcome to Lowell

booklet, which includes three simplified floor plans of the Welcome Home with annotations and reminders.

Figure 123. Welcome to Lowell

booklet, which includes three simplified floor plans of the Welcome Home with annotations and reminders.

Figure 124. Welcome to Lowell

booklet, which includes three simplified floor plans of the Welcome Home with annotations and reminders.

Figure 125. Welcome to Lowell

booklet, which includes three simplified floor plans of the Welcome Home with annotations and reminders.

Figure 126. Manipulations on Images

of Elevations booklet, with early design tests of exaggerations and distortions.

Figure 127. Manipulations on Images

of Elevations booklet, with early design tests of exaggerations and distortions.

Figure 128. Manipulations on Images

of Elevations booklet, with early design tests of exaggerations and distortions.

Figure 129. Manipulations on Images

of Elevations booklet, with early design tests of exaggerations and distortions.

Figure 130. Booklet with a photocopy

of the Acre Neighborhood District Design Review Standards, published by the Lowell Historic Board on October 13th, 1999.

Figure 131. Booklet with a photocopy

of the Acre Neighborhood District Design Review Standards, published by the Lowell Historic Board on October 13th, 1999.

Figure 132. Booklet with a photocopy

of the Acre Neighborhood District Design Review Standards, published by the Lowell Historic Board on October 13th, 1999.

Figure 133. Booklet with a photocopy

of the Acre Neighborhood District Design Review Standards, published by the Lowell Historic Board on October 13th, 1999.

Back Matter

Final Review

The final review was held on Thursday, December 20th, 2018 on the 6th floor of MIT Building E14 at 10:55.

The invited critics were Florian Idenburg, Keith Krumweide, Amy Kulper, Rosalyne Shieh, and Nida Sinnokrot.

A short slideshow was presented before moving to the 1:25 model, the large hand drawing, the five documents, the model photos, and the small hand sketches.

Figure 134. Model, documents,

drawings, and photos at the final review.

Figure 135. Final review

presentation.

Figure 136. Final review

presentation.

Figure 137. Final review

presentation.

Figure 138. Final review

presentation.

Figure 139. Final review discussion. 189

Figure 140. Final review discussion. 190

Figure 141. Final review discussion. 191

Process

My methodology for this thesis was to research through design. This often meant producing lots of stuff and then spending time with it to understand what the thesis would ultimately ask. The following section contains some of the

process work from my research, which includes sketches, quick collages, screenshots, renders, line drawings, and models.

Figure 142. Diagrams of

manipulations.

Figure 143. Various roof

manipulations.

Figure 144. Delaminated layers of a

wall can be manipulated seperately. Figure 145. Manipulations in one dimension.

Figure 146. Exaggerating wall

thickness. Figure 147. Changing the role and position of the wall.

Figure 148. Testing manipulations of

the porch in elevation.

Figure 149. Testing the spatial

results of the porch manipulations.

Figure 150. Testing manipulations of

cladding in elevation.