HAL Id: hal-03196773

https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03196773

Submitted on 25 May 2021

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of

sci-entific research documents, whether they are

pub-lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents

scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0

International License

Determinant morphological features of flax plant

products and their contribution in injection moulded

composite reinforcement

Lucile Nuez, Maxime Gautreau, Claire Mayer-Laigle, Pierre d’Arras, Fabienne

Guillon, Alain Bourmaud, Christophe Baley, Johnny Beaugrand

To cite this version:

Lucile Nuez, Maxime Gautreau, Claire Mayer-Laigle, Pierre d’Arras, Fabienne Guillon, et al..

Determinant morphological features of flax plant products and their contribution in injection

moulded composite reinforcement. Composites Part C: Open Access, Elsevier, 2020, 3, pp.100054.

�10.1016/j.jcomc.2020.100054�. �hal-03196773�

ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Composites

Part

C:

Open

Access

journalhomepage:www.elsevier.com/locate/jcomc

Determinant

morphological

features

of

flax

plant

products

and

their

contribution

in

injection

moulded

composite

reinforcement

Lucile

Nuez

a ,b ,∗,

Maxime

Gautreau

c,

Claire

Mayer-Laigle

d,

Pierre

D’Arras

b,

Fabienne

Guillon

c,

Alain

Bourmaud

a,

Christophe

Baley

a,

Johnny

Beaugrand

ca Université de Bretagne-Sud, IRDL, CNRS UMR 6027, BP 92116, 56321 Lorient Cedex, France b Van Robaeys Frères, 83 Rue Saint-Michel, 59122 Killem, France

c Biopolymères Intéractions Assemblages (BIA), INRAE, Rue de la Géraudière, F-44316 Nantes, France d IATE, Univ Montpellier, CIRAD, INRAE, Montpellier SupAgro, Montpellier, France

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Keywords: Fibres Shives Dust Fines Morphometric characterisation Injection moulding Carbohydrate analysisa

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Theuseofbiomassininjectionmouldedorextrudedthermoplasticcompositesisanimportantissue,especially whentryingtoaddvaluetolow-costco-products.Theobjectiveofthisworkwastoconductacompletestudy onthemorphologicalcharacterisationandcarbohydrateanalysisofarangeofco-productsobtainedduringthe processingofflaxstraw.Thus,themorphologyof(i)cutflaxfibres,(ii)fragmentedshives,and(iii)scutching andcardingdustsischaracterisedusingadynamicimageanalyserwithasievingapproach.Thesedifferent fractionsarethenusedtoproduceinjectionmouldedcompositematerials.Theirmechanicalperformancesare discussedinrelationtothemorphologyofthereinforcements,aswellastheircarbohydratecompositionsandfine particlecontents.Co-products,basedontheirreinforcementproperties,canbeclassifiedintothreecategories. Inallcases,areinforcingeffectisdemonstratedforthetensileYoung’smoduluswithanincreasefrom+24to +137%dependingofthematerial.Alinearrelationshipwasobservedbetweenthecellulosecontentofreinforcing materialandthetensilestrengthatbreakoftheinjectionmouldedcomposites.Theresultsarepromisingfor addingvaluetoallflaxco-productsinplasticsprocessing,targetingindustrialapplicationsinlinewiththeir intrinsicperformances.

Introduction

Flaxfibrereinforcedcompositesarenowpresentindifferent indus-trialsectorsandarethesubjectofnumerousacademicandindustrial developments.Flax(linumusitatissimumL.),whencultivatedforits fi-bres,offersvariousby-products,particularly(i)themostadded-value bastfibres,(ii)flaxshivesoriginatingfromthexylemofthestem,as wellas(iii)dustsinducedbythemanufacturingprocessingstepsof fi-breextractionandrefining.

Shortorcutfibres(<5mm)areusedforcompositematerialsthatare generallyextrudedorinjectionmoulded[1] .Themorphological charac-terisationoftheplantreinforcementsusedtoproducethesecomposite materialsisacrucialpointforarangeofreasons[2] :these dataare essentialtoevaluatethetensilepropertiesofthemanufactured compos-ites,thefibre-matrixadhesion,orfibrepacking,allofwhichare neces-saryformodellingstudiesandbehaviouranalysis,whereitisimportant toconsiderthemorphologyofthereinforcementsandtheirdispersion, particularlyinthecaseofthermoplasticcompositesobtainedvia com-pounding[3] .Thelengthanddiameterofthereinforcementsaretwo

∗Correspondingauthorat:Université deBretagne-Sud,IRDL,CNRSUMR6027,BP92116,56321LorientCedex,France.

E-mailaddress:lucile.nuez@univ-ubs.fr (L.Nuez).

mainparametersnecessarytoestimatetheirreinforcingcapacityina compositematerial [4] ; theyareassessedbythevalueoftheaspect ratio,whichrepresentsthelengthofthefibrouselementdividedbyits diameter.Thisaspectratioallowstodeterminetheefficiencyoftheload transferbetweenthereinforcementandthematrix.Inthecaseofflax fibres,rettingandextractingconditionsparticularlyaffectthediameter ofthefibrebundlesandthereforehaveadirectimpactontheiraspect ratio[5] .Theaspectratioalsodependsonthetoolsusedto manufac-turethecompositeparts[3] .Thewiderangeofshearratesthatpossibly occurinplasticsprocessingisalsoacriterionforselectingthebest pro-cessestopreservetheintegrityofplantfibres.Inaddition,inthecaseof injectionmouldedorextrudedparts,ithasbeenshownthat,depending onthenatureoftheprocessorthenumberofcycles,agreaterorlesser quantityoffineparticles(particlesoflessthan200𝜇m)maybepresent inthematerials[6] .Theseelementscandegradethemechanical perfor-manceofthepartsinasignificantwayandbeingabletoquantifythem isimportant[7] .

Themorphologicalanalysisofreinforcementsisaccessibleby differ-entmeans,includinglaserdiffractionmethods,staticordynamicimage

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomc.2020.100054

Received7August2020;Receivedinrevisedform21October2020;Accepted22October2020

2666-6820/© 2020TheAuthors.PublishedbyElsevierB.V.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ )

analysis.Theydependonnumerous parameters,suchastheanalysis method,theresolutionofeachequipment,theabilitytoobtaina statis-ticallyrepresentativesample,themorphologicalcomplexityofthe par-ticles,etc.

Laserdiffractionmethodsarebasedonthelightdiffractionof par-ticles,whichdependsontheirsize. Thistechniqueisgenerally accu-rateforsmallparticles,andwhileitallowsforhighspeedanalysis,it highlydependsontheopticalmodelwhichisnecessaryto mathemati-callytransformtheparticlescatterintensityintoasizedistribution. Op-ticalmodelssuchastheFraunhoferapproximationoftheMiescattering theoryarebasedonseveralassumptions,suchassphericalparticles[8] . Staticimageanalysisisbasedonparticlespositionedonaslidebefore inspectionbyacameraormicroscope,followedbyanimageanalysis methodrequiringathresholdingstep(separationofparticlesfromtheir background)beforefurtheranalysis.Examplesofstaticimageanalysis methodsincludemicroscopy orscannermeasurements,whichcanbe performedincombinationwithmanualimageanalysisorusingspecific softwaresuchasFibreShape.Nevertheless, thesestatic analysis tech-niquesaretime-consuming,theyoftenneglectthesmallestparticles[9] , andonlyslightvariationsweremeasuredbetweenthesemethodsand laser-baseddimensionalanalysis[10 ,11 ].

Fordynamicimageanalysis,particlesflow infrontofarecording camerathatcapturestheirshadowsatawantedfrequencyandthatare thenautomaticallyanalysedinasimilarmannerasstaticimage analy-sis.Furthermore,theuseofautomaticsystemsallowstogaintimeand thenumberofanalysedparticlescanriseuptoseveraltensofthousands ofobjectsinlessthanoneminute[12] ,suchaswiththeQICPIC[13] ,or withtheMorFiCompact○R fibreanalyser,whichisaspecificautomatic

equipmentinitiallydevelopedforthepaperindustrybeforeoraftera processstagethathasbeenusedindifferentstudies[6 ,14–16 ].The fi-brescirculateinawaterorethanolbathandimageacquisitionsallow forlengthsofseveralmmtobeanalysed,buttherelativelylowcamera resolutionispenalisingforsinglefibrediametermeasurements. How-ever,thismethodhastheadvantageofreliablyquantifyingfineparticles (lessthan200𝜇m)whosenumberfractionincreasessignificantlyafter injectionorextrusioncycles[6] .Otherautomatedmeasurement instru-mentsdesignedforcellulosefibreanalysisbypolarisedlightdiffraction includetheFS-200ortheFibreQualityAnalyser(FQA)[17–19] .The lensesused,thedepthoffocusandthefocusingdifficultiesassociated mustalsobetakenintoconsideration,dependingonthespecificitiesof thesampletobeanalysed.Thechoiceofameasuringtechniqueis there-foreacompromisebetweenwhatneedstobeanalysedandthecurrent availabletechniques.

Theaimofthis paperistomeasuretherelevantparametersof a rangeofflaxco-productsthatcanbeusedasinjectionmoulded compos-itereinforcements.Wefocusonthecharacterisationofhackledfibres, fragmentedshivesandevenscutchingandcardingdusts,i.e.,theoverall flaxproductsrepresentativeoftheentireflaxstem.Theiruses,length, individualisation,aspectratioorpresenceofaheterogeneous popula-tionofcomponents,morphologicallyspeaking,arequantifiedusinga dynamicmorphologicalanalyser.Theresults obtainedarethen anal-ysedinrelationtothestructure,carbohydrateanalysis,andoriginof thesedifferentflaxplantfractions;thentheiruseinpoly-(propylene) in-jectionmouldedcompositesismechanicallytestedandanalysed.These datamakeitpossibletofullyunderstandthespecificitiesofeachflax co-productandconsidertheirinterestforcompositematerial reinforce-mentapplications.

Experimentalprocedure

Flaxproducts Cutflaxfibres

TheflaxfibreisfromtheAlizéevariety,whichwasharvestedin2017 inNormandy,suppliedandcutbyDepestele(Bourguebus,France);flax stemswerepulledout,dewrettedfor6weeksandthenscutchedand

hackled.Theresultingfibreswerethenindustriallycutto1,2and4mm inlength,andrespectivelynamedFF1,FF2andFF4.Intherestofthis study,theterm“fibre” willdesignatebothelementaryfibresandflax fibrebundles,asbotharepresentinthethreestudiedbatches; other-wisedifferentiationwillbemadebyspecifying“elementaryfibres” or “bundles”.ThesamplesnamesandprocessingaresuppliedinFig. 1 .

Flaxshives

Theflaxshives(FS)wereprovidedinbulkbytheflaxscutching com-panyVanRobaeysFrères(France),followingthescutchingofthe2018 flaxharvestyear,beforebeingmilledwithalaboratoryscalerotating cuttingmill(RetschMühle,Germany).Themeshsizeofthegridused was500μm,accountingforsampleB500.Thelatter,afterbeing previ-ouslyovendriedat60°C,wasthenfurtherfractionatedbysieve sep-arationusingavibratingsievingcolumn(Proviteq,France)composed of5sieveswithsquaremeshsizesof630,400,315,100and50μm, andcompletedwithabottomsieve.Thesamplenamesandmethodsof obtentionaresummarisedinFig. 1 .

Scutchingandcardingdust

Scutchingandcardingdusts wereprovided bytheflaxscutching companyVanRobaeysFrères(France).Thescutchingdusts(SD)were retrievedfromthecondensersintheairvacuumingsystem,especially duringtherettedflaxbaleunrollingprocessinthescutchingline,and moregloballyalongeachstepofthescutchingprocess.Similarly,the carding dusts(CD)wereobtained duringthe refiningprocessof the flaxtowsor“short” fibresobtainedasco-productsduringthescutching [20] transformationstep,whichconsistsofcardingandfurtherrefining. SamplenamesandmeansofproductionareshownFig. 1 .TheSDand CDwerefractionatedviasieveseparationusingavibratingsieving col-umn(Retsch,Germany)composedof5sieveswithsquaremeshsizesof 500,250,180,125and90μm,andcompletedwithabottomsieve.

Particlesizeanalysis

Particlemorphologywasstudiedbyadynamicimageanalysis de-vice,QICPIC(SympaTecGmbH,Germany).Thisequipmentwaschosen, sinceitmustbeabletoevaluatethelengthofavarietyofparticles(from thesizeoffinestothatofflaxshivesofvaryingdiametersandofflax fibreelementsofdifferentlengths).Eachsamplehasasubstantial vari-ability,sothistechniqueisalsoabletomeasureaconsiderablenumber ofparticlestoensureitsstatisticalrepresentativity.Differentprotocols havebeenadaptedfortheparticle’smorphometricdescription.Because ofatendencytoparticleaggregation,theflaxshives(bothfragmented andsievedportions),thecutfibres,andthescutchingandcardingdust samplesweredispersedinliquidusingaunitadaptedtothedevice, LIX-CEL,whichprovidesbothultrasonicagitationandstirringatthesame time.Eachsamplewasweighedtoapproximately50mganddispersed firstin5mLofethanoland45mLofdistilledwater,beforethefinal dis-persionin950mLofwaterwithamagneticstirrer.Theflaxshiveswere analysedusingtheM7lensspecifictotheQICPIC,whichisappropriate formeasuringparticlesofalengthrangingfrom4.2μmataminimum to8665μmatamaximum(ISO13322-1/2).Thecutflaxfibresamples wereanalysedwiththeM9lens,whichisappropriateforparticles rang-ingfrom17μmto33,792μm(ISO13322-1/2)inordertocomparethe sampleswithoneanother.

Thenumberof analysedparticlesvariedbetween 39,000and2.8 million,dependingonthesamplesandmeasurements,andweremade induplicatestoensurereproducibilityoftheresults.PAQXOSsoftware (SympaTecGmbH,Germany)wasusedtocalculate,inrealtime,the par-ticlelength,definedastheshortestpathbetweenthemostdistantend pointsoftheparticlesafterskeletonisation(Lefi function).Theparticle diameterwascalculatedusingtheDifi function,definedasthedivision oftheprojectedparticleareabythesumofallbranchlengthofthe fi-breskeleton.Theparticleaspectratiowascalculatedastheoppositeof theelongationparametergivenbythePAQXOSsoftware(definedasthe

Fig.1.Reinforcingmaterialsamples,theiroriginandcorrespondingprocessingstepsusedforisolation.FF1,FF2andFF4refertothescutchedandhackledflax fibrescutto1,2and4mm,respectively;B500referstothefragmentedflaxshives;T630,T400,T315,T100,T50,andTbotrefertoitssievedfractionscollected abovethecorrespondingmeshsizes,andfinallySDandCDrefertothescutchingandcardingdusts,respectively.S500,S250,S180,S125,S90andSbot,aswellas C500,C250,C180,C125,C90andCbot,refertotheirrespectivesievedfractions.Thecolourkeyisrespectedthroughoutthisstudyforthemainsamples.

ratioofDifi andLefi).Anothermorphologicalparameter,sphericity,is calculatedtocharacterisetheparticles.Sphericityisdefinedasfollows (Eq. (1) ):

𝑆𝑝ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑖𝑡𝑦= 𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑖𝑚𝑒𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑜𝑓𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑐𝑖𝑟𝑐𝑙𝑒

𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑖𝑚𝑒𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑜𝑓𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑡𝑖𝑐𝑙𝑒𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑗𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 (1)

Theanalysiswas conductedonthebasisof thevolume distribution, whereeach particleisgivenaweightdependingon thevolume ofa cylinderofalengthanddiameterequivalenttothedimensionsofthe particle.ThedistributionspaniscalculatedfollowingEq.(2):

𝑆𝑝𝑎𝑛=90

𝑡ℎ𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑙𝑒− 10𝑡ℎ𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑙𝑒

50𝑡ℎ𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑙𝑒 (2)

Scanningelectronmicroscopy(SEM)observations

Each sample was observed usinga scanningelectron microscope (JeolJSM-IT500HR,Japan)afterbeingsputtercoatedwithathinlayer ofgoldinanEdwardsSputterCoater.Theimagesweretakenunderx25 andx100magnification.TheSEMobservationswerefollowedbyan el-ementalanalysisusinganenergydispersiveX-rayanalysissystem(EDS) fortheTbotsamplesofscutchingandcardingdustsusingaJeolSDD JED-2300analysisstationonthepreviouslycitedSEM.Theaccelerating voltageforthelatterwas5kV.

Compositemanufacture

Each categoryof flaxco-productswasused tomanufacture poly-(propylene)(PP)reinforcedinjectionmouldedcompositeswitha 30%-wtfractionforeach,followinganextrusionprocess.Thepolymermatrix

usedinthisstudywasaPPC10,642(TotalPetrochemicals,France)with anMFIof44g/10min(230°C-2.16kg).Asacompatibiliser,amaleic anhydridemodified PP(MAPP)wasadded totheformulationat the proportionof4%-wt.ThepolymerusedwasOrevacCA100(Arkema, France)withanMFIof10g/10minat190°Cand0.325kg.

Beforemanufacturing,boththescutchingandcardingdusts,SDand CD,wereovendriedat60°Cforapproximately12h.Theywerethen compoundedwithaco-rotatingtwin-screwextruder(TSA,Italy)and in-jectionmoulded(BattenfeldBA800,Austria)intoISO527-2type1B nor-malisedspecimensfollowingthesameprocessasdescribedelsewhere [21] .Theextrusiontemperatureprofilewentfrom180°Cto190°Cwith adietemperatureof180°C,andaconstantbarreltemperatureof190°C wasappliedduringinjection,withamouldtemperatureof30°C.The manufacturingprocessofthesamplesproducedwithfragmentedflax shives(B500)andflaxfibresof1mm(FF1)wasdescribedinaprevious study[21] ,aswellasforthecompositesproducedwith2mmlongflax fibres(FF2)andwithtalc[7] .

Tensiletest

Tensiletestingwasconductedontheinjectionmouldedcomposite specimensfollowingtheISO527standard.AnMTSSynergie1000RT machinewasused.Thetensilespeedwas1mm/min,thenominallength was25mm,andtestswereperformedinacontrolledenvironmentof 23±2°Cand50±5%relativehumidity.Aminimumoffivespecimens weretestedfollowingconditioningduringatleast24hinthesame con-ditionsasduringtesting. A10kNsensorwasmountedonthemachine tomeasuretheappliedforceonthespecimen,whileanextensometer

allowedformeasuringthedeformationduringtesting.Aminimumof5 specimensweretestedpercompositeformulation.

Carbohydrateanalysis

Awetchemicalanalysiswasusedtodeterminethemonosaccharide contentofeachstudiedflaxproductmaterialcategory.Duetotheirsize andforthepurposesofhomogeneity,approximately1gofflaxfibres wasinitiallycryogrinded(SPEX6700freezermill).Followingthisstep, approximately 5mgof each sample(fragmented flaxshives, scutch-ingandcardingdusts)werepre-hydrolysedwith12MH2SO4(Sigma Aldrich,USA)for2hat25 °Candthenfurtherhydrolysed in1.5M H2SO4for2hat100°C.Individualneutralsugars(arabinose, rham-nose,fucose,glucose,xylose,galactoseandmannose)werequantified aftertheir derivatisationintoalditol acetates.Liquid-gas chromatog-raphy(PerkinElmer,Clarus 580,Shelton, USA)equippedwithaDB 225capillarycolumn(J&WScientific,Folsom,USA)wasperformedat 205°C,usingH2asthecarriergas,inordertoanalysethealditolacetate derivatives[22] .Astandardsugarssolutionandinositolasinternal stan-dardwereusedforcalibration.Uronicacids(sumofgalacturonicacid (GalA)andglucuronicacid(GlcA))inacidhydrolyzateswerequantified usingthem-hydroxybiphenylmethod[23] .Measureswereperformed intriplicate,andtheresultsareexpressedasapercentageofdrymatter mass.

Ashcontent

Approximatively2g ofscutchingandcardingdustsample(SDor CD)werefirstweighted(m1)anddriedinanovenat130°Cfor90min. Aftercoolingtheywereweighedagaintodeterminethedrymass(ms). Thewatercontent(w)wascalculatedusingEq.(3):

𝑤=1− 𝑚𝑠

𝑚1

(3) In parallel, approximatively two other grams of samples were first weighed(m2)andthenpyrolyzedat900°Cfor2hrsfollowingnorm ISO2171withaHeraeusThermo-lineoven(ThermoFischerScientific, USA).Theresidualmasswasweighted(mr)aftercoolinginadesiccator

toroomtemperature.Theashcontentonthedrymaterialwascalculated accordingtoEq.(4):

𝐴𝑠ℎ=100∗ 𝑚𝑟

𝑚2 ∗ (1−𝑤)

(4) whereAshisa percentage,m2 is thesamplemassin grams, andmr

is thesampleresidualmassin grams, andwthewater content.The experimentswereconductedinduplicateandaveraged.

Resultsanddiscussion

Morphologicalanalysis Cutflaxfibres

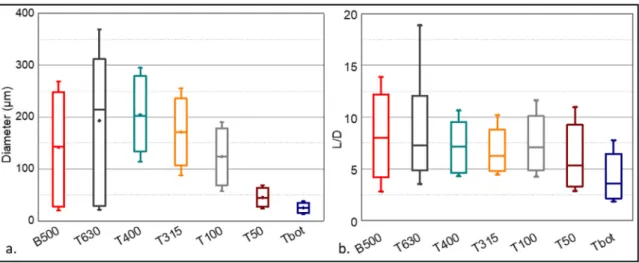

Sincethemeanlengthvaluedoesnotgiveanyinformationonthe distributionspanandisnotrepresentativeofagivensample,theresults arepresentedinabox-plotdiagram,asshowninFig. 2 a,withthe10th (firstdecile),15th(firstquartile),50th(median),85th(thirdquartile), and90th(lastdecile)percentilesofthecumulativelengthdistribution, movingfromthebottomup.Thearithmeticmeanisadditionally repre-sentedwithadot.

Fig. 2 bshowsasymmetricdistributionforallthecutfibresamples, withameanlengthequaltothemedian.Thearithmeticmeanlength oftheflaxfibresis973±15μm,2046±14μmand4044±65μm forFF1,FF2andFF4,respectively,signifyinganormaldistributionfor thesethreesamples.

Fig. 3 arepresentstheSEMobservationsofthecutflaxfibres,whereit ispossibletosee,forallsamples,ahomogeneousfibrelengthintheform ofbothelementaryfibresandbundles.Tocomplete thisobservation,

thediagramsinFig. 3 bdisplaythecapturedimagesofthefibresbythe QICPICduringthedynamicimageanalysis.Forallsamples,thecutfibre lengthisfullyconsistentwiththetargetedvalue,butanon-negligible amountofverysmallparticles,notablyoffines(particlesoflessthan 200μm)isalsopresent.Thislengthdistribution(Fig. 2 b)furthermore validatesthecuttingmethodused,asthetargetedlengthsarereached witharelativeerroroflessthan3%forallsamples.

Thediameterdistributionofthecut flaxfibresamplesisgivenin Fig. 4 a,withmeandiametervaluesof112.7±3.6μm,162.8±6.3μm, and180.3 ±7.3μmforFF1, FF2andFF4,respectively. Indeed, the shearingstressesinducedbythecuttingprocesstendtoindividualise thefibrebundles[24 ,25 ]:thesmallerthedesiredfibrelength,thehigher theshearingstressesandthemoreindividualisedthefibres.Thesmall shoulderfordiametersbetween40and65μmforeachmeasuredsample maybeduetoananalysisartefactlinkedtothechosenlens.

Theaspectratio,beingtheparticle’slengthdividedbyitsdiameter, isagoodindicatoroftheparticleelongationandcomposite reinforce-mentpotential.Fig. 4 bshowsanincreaseinboththefibreaspectratio andthedistributionspanwiththefibrelength.Themedianaspectratio increasesfrom8.2to13.0and23.8forFF1,FF2andFF4,respectively, whilethedistributionspanincreasesby1%and17%whenFF2andFF4 arecomparedtoFF1,respectively.Thisoutcomeisexpected consider-ingtheeminentincreaseinthefibrelength(thelengthsofFF2andFF4 aremultipliedbytwoandbyfourwhencomparedtoFF1)withrespect tothegradualincreaseofthesamples’diameters[26] .

Fragmentedflaxshives

Fig. 5 arepresentsthelengthdistributionofthefragmentedflaxshive sampleB500,aswellasitssievedfractions.TheB500samplepresents an importantspanin thelength distribution,with ameanlength of 1262±64μm.Thislengthiscoherentwhenlookingatthelength distri-butionofeachsievedfractionandwhenconsideringtheir correspond-ingmassfractions.ThecoarsestparticlesinsampleT630alsopresenta widelengthdistributionwithameanparticlelengthslightlyhigherthan B500at1487±45μm.Whilethesievingstepperformedinthisstudy mightprovetobecostlyatanindustrialscale,itemergesasaprecious insightforunderstandingthevarietyofparticlemorphologies.The siev-ingmassfractionisgivenundereachsievedsample(Fig. 5 a).Sample T400accountsfor62%oftheinitialB500fragmentedshives,together withsamplesT630andT100,whicheachmakeupfor13%ofthe ini-tialmassofB500.ThispercentageissurprisinglyimportantfortheT630 sample,regardingthefactthattherotatingcuttingmillgridmeshsize was500μm.Itcanbeexplainedbytheagglomerationoflonger parti-clesduringsievingthatcouldpreventaportionofsmallerparticlesto passthroughthesieve,andthuscauseanimportantdistributionspan. Theremainingsievedfractions(T315,T50andTbot)sumup to12% onceaddedtogether.Therefore,themajorityofthefragmented parti-clesbelongtotheT400sievedsample,thustheyarethemostpresent intermsofmassinB500.However,themorphologiccharacteristicsof thecutting-milledB500flaxshivesampleenclosethoseofeachsieving fractionandwereusedassuchforthecompositereinforcementmaterial (seeSection3.2).

TheSEMobservationsof theflaxshivesample (Fig. 5 b–g),show thepresenceoftheremainingfibres(bothelementaryandintheform ofbundles),particularlyforT630(Fig. 5 b)andT50(Fig. 5 f),together withlargesizedflaxshivefragments.Fibrestendtoagglomerateduring sievingfractionation,whichcouldexplainwhytheyaresoimportantly presentinthisfraction.

Thefollowingsievingfractionsshowamorerestrictedlength distri-bution,withmeanlengthsat1443±2μm,1126±8μm,920±19μm, 276±1μmand106±4μmfortheT400,T315,T100andTbotsamples, respectively.TheirSEMimages(Fig. 5 c–g)clearlyshowareductionin theparticlediameterwitheachsieveseparation,withparticlesof rel-ativelyhomogeneouslengthsforsamplesT400andT315,accounting bothforalengthdistributionspanof0.8.Incontrast,thelength dis-tributionspanoftheremainingsamplesgraduallyincreasesto1.3for

Fig.2.a.Exampleofaboxplotdiagramand theappropriatesignification,b.Length distri-butionof cutflaxfibresamplesof 1,2 and 4mm(samplesFF1,FF2andFF4,respectively) followingscutching,andhackling.

Fig.3. a.SEMobservationsofcutflaxfibresamplesof1,2and4mm(samplesFF1,FF2andFF4,respectively)followingscutching,andhackling,b.Corresponding analysedparticlesobtainedbydynamicimageanalysis.

Fig.4. a.Diametercumulative (dottedline) andrelativedensity(fullline)distributionof thecutflaxfibres.b.Aspectratiodistribution ofthecutflaxfibres.

Fig.5.a.Particlelengthdistributionofflaxshivesamplesbeforeandaftersievingwiththecorrespondingmassfractionsaftersieving,bTheSEMimagesofthe sievedflaxshivesaretakenwithax25magnificationforallsamplesexcepttheT50andTbotdetailedviews,whicharemagnifiedatx100.

Fig.6. a.Flaxshivediameterdistribution,b.Flaxshiveaspectratiodistribution.

sampleT100andto1.7forsamplesT50andTbot.Whiletheparticle lengthremarkablydecreasesforthesethreesamples,theSEMimages predictablyshowdistinctheterogeneityintheparticlelength.

Inthisstudy,particleseparationisconductedbymeansofa vibrat-ingsieving device.Therefore,sinceaparticle’saspectratioincreases withrespecttoagivenmeshsize,theprobabilityofthisparticlepassing throughthisspecificsievedecreases[27] .Furthermore,thelongest par-ticles,whichtendtoagglomerateduringsieving,andmorefragmented particlescanbefoundinsievefractionslikeT50.Thelongestparticles retainedonthesievetendtoformameshandcouldagglomeratewith smallerfragments,asobservedfortheT630fractioncontainingboth fibresandcoarse particles.Agglomeration couldalsobeduetostatic electricitychargingofparticlesinducedbyrepeatedmovementsofthe vibratingsievingoperation.

Fig. 6 ashowstheevolutionoftheflaxshives(FS)diameterwiththe sievingseparation.TheoriginalfragmentedFSsample,B500,showsa symmetricdistribution,withameandiameterof142.4±0.01μm.The T630sample,presentingtheremainingunsievedparticles,showsa par-ticlediametergoingfromafirstdecileof21.5±0.3μmtoalastdecile of369±85.7μm,revealingthepresenceofbothfibresandFSparticles, withameandiameterof202.1±20.4μm.Thefollowingsievedfractions presentadistributionclosetosymmetric,withameandiameterthat progressivelydecreasesfrom201.7±18.0μmforT400,170.1±4.9μm

forT315,124.6±0.3μmforT100,45.2±1.2μmforT50andfinally 25.5±0.3μmforthebottomsieve.

Interestingly,despiteasubstantialsievingtime(over40min),the di-ametersoftheparticlesoverlap(Fig. 6 a).Thisoverlapcanbeexplained bythefactthatinorderforparticlestopassthroughaspecificmesh size,theymusthaveatleasttwodimensionsthatareinferiortothe min-imumsquareapertureofthegivensieve[28] .Furthermore,duringthe dynamicimageanalysismethodused,mostparticlescanmovefreelyin thethreedimensions.Thismovementcausesthemeasured“diameter” topotentiallycorrespondtotheparticle’sthickness.Flaxshives,asseen intheSEMobservations(Fig. 5 b),havearectangularshapewhenseen fromallthreedimensions.

The FS aspect ratio was additionally calculated and is given in Fig. 6 b.Amedianaspectratioof8fortheinitialfragmentedFS sam-ple(B500)decreasesandstaysrelativelyconstantaround7forsamples T630,T400,T315andT100,andthenfurtherdecreasesforthelasttwo sievefractions,at5.4and3.6forT50andTbot,respectively.Themean diameterdecreaseswithrespecttothedecreasingmeshsize,whichis consistentwiththedecreasingaspectratiooftheparticles.

Estimationofthemorphologicaldiversityofscutchingandcardingdust

Forthetwodustbatchesandassociatedfractions,SEMobservations wereperformed(Fig. 7 ).Thetwobatches, SDandCD,contain dust,

Fig.7. SEMobservationof;a.Scutchingdustandh.Cardingdust.Observationsofeachsievedfractionisshowninb-gandi-nsub-figuresforscutchingandcarding dust,respectively,foreachsievinggrid:b,i=500μm,c,j=250μm,d,k=180μm,e,l=125μm,f,m=90μmandg,n=Tbotfraction.

Fig.8. a.Scutchingdustdiameterdistribution,b.Scutchingdustsphericitydistribution.

fibresandshivesatdifferentproportions.Onecannoticethatthereare morefibresandshivesforCD(Fig. 7 h)incomparisonwithSD(Fig. 7 a). Conversely,SDshowsagreaterdustpopulation.Thisoutcomeislogical, asthecardingstagetakesplaceafterscutching;atthisstage,thebatches offibreshavealreadybeencleanedofalmostallmineralpollutionand oftheshivesanddustgeneratedduringscutching.Eveniftheshivesare specificallysortedduringscutching,asmallfractionmaybepresentin thescutchingdust.

Fig. 8 ashowstheevolutionofthediameterofthescutchingdust(SD) asafunctionofthemeshofthesieve,andtheresultingweightfractions arealsomentioned.ConcerningtheSD-Rawsample,thedispersionis verylow due totheimportantfraction of smallparticlesin theraw batch(70%-wt<125𝜇m),andtheremainingfibresandshivespoorly

impacttheresults.Asexpected,anincreaseinthediameterisobserved withanincreaseinthesievemesh.TheS500samplehas,witha sym-metricalrepresentation,thelargestdiameters,withanaveragediameter of354.0±11.6𝜇mandalastdecileof527.7±22.0𝜇m,illustratingthe presenceofshivefragments,asevidencedinFig. 7 b.TheS250sample, withafirstdecileof111.9±7.1𝜇mandalastdecileof373.6±30.1𝜇m,

showsamixtureofshivesandbundlesoffibres(Fig. 7 c).Allofthe fol-lowingsamplesalsohaveadistributionsimilartoasymmetrical dis-tribution,themeandiameterofwhichdecreaseswithadecreaseinthe sizeofthemeshofthesieves,withsamplesS180andS125havingmean diametersof81.6±5.2𝜇mand37.7±1.3𝜇m,respectively.Forthelast twosamples,S90andSbot,thedispersionofthediametersismuchless pronounced.Indeed,thefirstdecileis6.2±0.1𝜇mandthelastdecileis

Fig.9. a,c:initialSEMimagesofscutchingandcardingTbotsamples, respec-tively.b,d:silicaanalysisofthesamerespectivesamplesviaenergydispersive X-rayanalyser(EDS).

28.0±1.0𝜇mforsampleS90.ThetrendisidenticalfortheSbotsample withafirstdecileof6.3±0.1𝜇mandalastdecileof25.5±0.3𝜇m.

Theselasttwosamplesarerepresentativeofamixtureofdustand fi-bres.Fig. 7 fandgstronglyconfirmthisanalysiswiththepresenceof numeroussmallparticlesequivalenttofines,whichprobablycomefrom mineraldustfromthesoil.

Thishypothesisisconfirmedbyanelementaryanalysis,asshownin Fig. 9 .MainlyfoundintheSbotsample(Fig. 9 aandb),thesesmall parti-clesareveryrichinsilica,whichconfirmstheirorigin.Theyarepresent inmuchsmallerquantitiesintheC-botsample(Fig. 9 candd)dueto therefiningtreatmentsundergonebythefibres,whichhaveremoved themajorityofthesoilresidues.

Becausethe scutchingandcarding dustsamples arebothmainly composedoffinesandbecausetheirmorphologyisquitedifferentfrom thatoffibresorshives,theirsphericitywasanalysedratherthantheir as-pectratio,whichwouldnotreallyhaveaphysicalmeaninginthiscase. Fig. 8 bshowsthesphericityofSDaccordingtothemeshofthesieve, whereasphericityofonecorrespondstoaperfectsphere.The spheric-ityofSD-Rawpresentsthegreatestdispersion:from0.18to0.92.For allothersamples,thesphericityoscillatesbetween0.25and0.84. How-ever,somedifferences betweenthesamplesarenoticeable.ForS500

andS250,thedispersionofthesphericityistight.Indeed,thefirstand lastdecileare0.42and0.77,and0.37and0.74forS500andS250, re-spectively.SamplesS180andS125showthepresenceofparticleswith asphericitylessthan0.3withameansphericityof0.47and0.56, re-spectively.Afibrehasasphericityofapproximately0.3;therefore,this sphericitywouldsuggestasignificantpresenceof fibresinthesetwo samples,asshowninFig. 7 dande.Concerningthelasttwosamples, S90andSbot,thefirstdecileofthesphericityisverycloseto0.40,with valuesof0.39and0.40,respectively.Thesevaluesindicatethepresence ofmainlydustandalsooffibres,butinalesserquantity.

Fig. 10 aillustratestheevolutionofthediametersofthecardingdust (CD)asafunctionofthemeshofthesieves.Ageneraldecreaseinthe diameterisobservedforeachsamplewithdecreasingsievemeshes.The C500samplehasasymmetricaldiameterdistribution,withamean di-ameterof235.1±14.0𝜇m.ThelastdecileofC500,484.6±22.7𝜇m,

illustratesthepresenceofelongatedparticleslikefibrebundlesand/or shives (Fig. 7 i). The C250 sample represents the diameters with a highdispersion towardslarge diameters:the valueofthelast decile is 295.7 ± 5.9𝜇m, showing thedisappearance of thelargest shives presentintheC500sample.Inaddition,thediameterdistributionofthe C250sampleisnolongersymmetricalwithamediandiameterequalto 83.06 ±1.7𝜇m.Thelastthree samples(C125,C90andCbot)show a gradualdecrease in theaveragediameter from33.4±0.8 𝜇mfor C125,13.6±0.2𝜇mforC90and13.2±0.1𝜇m forCbot.TheC90 andCbotsamplesmainlyconsistofdustandunitfibres(Fig. 7 mand n).FortheCD-Rawsample,thedispersionofdiametersisverylimited: from10.2±0.2𝜇mto42.8±1.3𝜇m;comprisingthemeanvalues ob-tainedforsamplesC125,C90andCbot.Onecannoticeinthiscasethe verylowfractionofdust,comparedtoSDsampleatthesamestage.

Fig. 10 bshowstheevolutionofthesphericityofthesamples follow-ingthesievingofCD.Forthemajorityof thesamples,thesphericity varies verylittle:0.62,0.66,0.53and0.58forsamplesC500,C250, C180andC125,respectively. FortheC90andCbotsamples,the av-eragesphericitiesare0.53and0.55,respectively.Incomparisonwith thereciprocalsamplesofthescutchingdust(SbotandS90),thereisa decreaseinthissphericity.Inotherwords,itindicatesthepresenceof morefibresinCD,whosesphericityislessthanthatofSD.

Fig. 11 ashowstheashfractionsofdrymatterfortheSDandCD. Forrawsamples(SDandCD),thedifferenceisremarkable:theSDhas anashcontentof58.2%fordrymatter,whereas fortheCD,theash contentdoesnotexceed8%.Inthisway,andSDismainlymadeupof minerals.Fig. 11 balsopresentsthedistributionofthemassfractionof eachsample,accordingtothesizeofthemeshofthevarioussievesused. ThemostimportantfractionoftheSDoriginatesfromtheSbotsample

Fig.11. a.Ashcontentscutchingandcardingdusts,b.Sievingmassfractionof SDandCD.

with38%ofthetotalmass,whilethelargestfractionoftheCD corre-spondstothe250μmsieve(C250sample)withalmost44%ofthetotal mass.Thesedistributions,specifictoeachtypeofdustoriginatingfrom twodistincttransformationprocesses,perfectlyillustratethediversity ofthecomponentsmakingupthesample.Thus,CDismainlymadeup offibreelements(bothelementaryandinbundles)becausethe card-ingprocessoccursontowsobtainedafterthescutchingprocess,where rettedplantstemsaremechanicallytransformedandarethereforealso cleanedoftheorganicandmineralduststheycarryfromthefieldsthey werecultivatedin.

Contributionininjectionmouldedcomposites Reinforcingeffectoftheflaxstemproducts

Allthreecategoriesofreinforcingmaterials,forwhichthe morpho-logicalaspectshavebeenstudiedpreviously(Section3.1),wereused asreinforcementmaterialata30%massfraction,withthesame poly-(propylene)(PP)matrixcontaining4%-wtmaleicanhydridemodified poly-(propylene) (MAPP) and processing conditions. The tensile be-havioursoftheinjectionmouldedcompositesprocessedwitheach cat-egoryofmaterial(cutflaxfibresFF1,fragmentedflaxshivesB500,and bothscutchingSDandcardingdustCD)aredisplayedinFig. 12 a,while

Fig. 12 bdisplaysthe Young’smodulus of thedifferentflaxinjection mouldedcompositesasafunctionoftheitstensilestrengthatbreak, andacomparisonwiththeresultsobtainedintheliteratureforother composites.TheFig. 12 bshowsthatthescutchingandcardingdusts arealreadyresponsiblefora+24%and+32%increaseintheYoung’s modulus,respectively,whencomparedtotheinitialPP-MAPPmatrix, comingclosetotheflaxfinesstudiedbyBourmaudetal.[7] ,inducing

a+36%increaseinthetensilemodulusofthecomposite.Thefollowing area+88%,+112%and+114%increaseintheYoung’smodulusdue towoodflour(WF),B500flaxshives,anda50/50-wtmixtureofB500 flaxshivesand1mm-longflaxfibres,respectively[21] .Theactionof 1or2mmflaxfibresinducesanaverage+137%effectontheinjection mouldedcomposite’sstiffness[7 ,21 ].

Concerningtheeffectofthesereinforcingmaterialsonthe compos-ite’sstrengthatbreak,scutchingdustsofferalimited,butnevertheless positive,8%increase,whilecardingdustsandfineshaveanequivalent effectwitha+18%and+14%increase,respectively.Then,woodflour, B500shivesandtheFF1-B500mixtureareresponsibleforanincrease instrengthof+48%,+39%and+53%,respectively.Finally,thefibre reinforcingmaterials(FF1andFF2)areresponsibleforanincreasein thetensilestrength,rangingbetween+65%and+79%.

In addition tothe expected increase in the tensile strength and Young’smodulus,andadecreaseinthedeformationatbreak,the re-inforcementmaterialsdonotchangetheglobaltensilebehaviourofthe reinforcedPP-MAPPcomposites(Fig. 12 a).

Furthermore,threecategories(materialisedbycirclesinFig. 12 b) of reinforcing efficiency, equivalent to the three types of materials presentlystudiedcanbedifferentiated:thefines,theparticulate mat-ter(fragmentedshivesorwoodflour)andthefibres.Thesecorrespond toaspectratiosoflessthanorequalto5fortheflaxfines[7] anddusts, 5to8forflaxshivesand8to24andaboveforthefibresstudiedhere. Similarly,thereinforcementpotentialhasalsobeenobservedforlow aspectratiofibres[29] .Nevertheless,anaspectratioof10isgenerally admittedastheminimuminordertohaveamarkedreinforcingeffectin injectionmouldedcomposites,andthisisonlythecaseherefortheflax fibrereinforcedcomposites.Onemustneverthelesskeepinmindthat themethodofanalysishasanimportantimpactontheabsolute mea-suredaspectratiowhencomparingdifferentliteraturesources.Manual methodsareoftenimperfect due totheirtendency tonot takesmall particleswithalowaspectratiointoaccount[9] .

Whilethereinforcingpotentialofcutflaxfibresininjectionmoulded compositesgreatlydependsontheiraspectratiototransferloads,the shearingstressesinducedduringtheextrusionandinjectionstepsare suchthatthefibrelengthisrapidlyreducedbythetransformation

pro-Fig.12. a.Tensilebehaviourof30%-wtreinforcingmaterialsinPPwith4%-wtMAPP,b.Young’smodulusandtensilestrengthatbreakofapoly(propylene) injectionmouldedcompositewith30%-wtofthereinforcementmaterial.Datafrom2mmlongflaxfibres,flaxfinesandtalctakenfrom[7] ,andthatcontaining 1mmflaxfibresandflaxshivesorwoodflourfrom[22] .

Fig.13. Tensilestrengthatbreakasafunctionoffineparticlecontentinitially presentinthereinforcingmaterialsforinjectionmouldedspecimen.

cess,eitherbecauseofthefragilebehaviouroftheflaxbundles,orby afatiguemechanismsforelementaryflaxfibres [30] .Forinstance,it hasbeenshownthat2mm-longflaxfibreshaveanequivalent reinforc-ingefficiencyto1mm-longflaxfibresinboththetensilestrengthand Young’smodulusofpoly-(propylene)injectionmouldedcomposites af-terthecommonextrusionandinjectionprocesssteps,andatthisstage bothfibresampleshadsimilaraspectratios[31] .Interestingly,fines,CD andSDcannotbeassimilatedtojustloadingproducts,buthaveareal functionofreinforcement,whetherconsideringthestrengthorYoung’s modulusofassociatedcomposites.Eveniftheiraspectratioismoderate andalsoimpactedbytheextrusionandinjectionprocess,twin-screw ex-trusionisabletoreachahighindividualisationdegree[3] ,infavourof thereinforcingeffect,minimisingthebundlesandaggregates,evenfor lowaspectratioparticles.Thepropertiesofbothscutchingandcarding dustsareinagreementwithboththetensilestrengthandtensile mod-ulusvalues obtainedwithpoplarsawdust,industriallyusedforwood plasticcompositemanufacturing, andPP and2%-wt MAPP injection mouldedcomposites wherethereinforcement materialhasanaspect ratiobetween3.5and4.5[32] .

Asexplained,themechanicalperformancesofthesethreefamilies offlaxreinforcedcompositesareimpactedbytheaspectratioof rein-forcement;thislatterishighlyimpactedbythevolumefractionoffine particles(<200𝜇m),whichherevariesfrom2%orlessforallcutfibre lengthsto53%fortheCDsamples.Fig. 13 highlightsaclear correla-tion(R2=0.974)betweenthetensilestrengthatbreakandthevolume fractionof finesinitiallypresentin thefivecategoriesof reinforcing samples.

TheseresultsconfirmthestrongimpactoftheL/Dratiooninjection mouldedcompositemechanicalproperties.Whenexclusivelyanalysing thepopulationoffinesoriginatingfromFF1andFF2,theirmedian as-pectratiosare2.8and2.5,respectively,whilethemedianaspectratios oftheentiresamplesofcutfibresFF1andFF2are8.2and13.1, respec-tively.Moreover,Bourmaudetal.[7] showedthatthetensilestrengthat abreakefficiencyratioofflaxfines,generatedbythefibrepreparation process,is1/10whencomparedto2mm longflaxfibresequivalent totheFF2sample. Fines,andheremorespecificallydust,canbe as-similatedtofillersintheiruseincompositematerials.Thefillershave severalroles,includingthatofreducingthecostofthematerialor in-creasingitsprocessabilitybyvaryingthestiffnessorviscosity.Ithas beenpreviouslyshown[7] thattheapparentviscosityofPP-fine par-ticlesissimilartoPP-talc.Inaddition,thisapparentviscosityforhigh shearratesisrelativelyclosetothatofthevirginmatrix,indicatingthe lowimpactoffinesontheflow.

Fig.14. Monosaccharidesandglucosechemicalcompositionofthemaintypes ofsamplesstudied.WFreferstowoodflourforcomparisonpurposes.TheFF, B500andWFvalueshavebeencompletedfrom[22] .

Furthermore, themechanical properties of injection moulded de-pendson severalparameters, suchasthemicrostructureof the rein-forcingmaterials,theirdistributionandorientationwithinthematrix, andonitstheadherencewiththematrix,tociteafew.Asthetotality ofthisinformationisnotknowninthisstudy,thefollowingdiscussion focusesontheknownpropertiesofthereinforcingmaterials.

Discussiononthecarbohydratecomposition

Theresultsofthecarbohydrateanalysiscarriedoutonthedifferent sample categoriesaregivenin Fig. 14 . Glucose,assimilated to cellu-lose,accountedforapproximately70%offlaxfibredrymass,whileflax shivesandwoodflour(includedhereforcomparisonpurposes)havea similarglucosecontentof31and43%,respectively.Thelattertwo sam-plesalsodifferentiatewiththeiramountofxylose,whichforflaxshives ismorethanthreetimesthatofwoodflour,andmannosecontentwhich, forwoodflour,is7timesthatofflaxshives.Thewoodflourdatawas takenfromapreviousstudyforcomparativepurposes[21] andsugar compositionisinagreementwiththeliterature[33] .Itdiffersfromthe compositionofthehighlycellulosicflaxfibres,whereasitisquitesimilar tothatofflaxshives.Duetocrosslinkingofthelignin-xylosenetwork in woodcellwalls,someauthors[34] haveevidencedanincreasein thewoodcellwallstiffnesswiththeprocessingandrecyclingstage in-ducedbytemperatureexposure.Inthiscontext,itwouldbeinteresting tofurtherinvestigatetherecyclingbehaviourofflaxshivescompounds. Thiscouldbeapositiveargumentfordevelopingthesematerials.Both theflaxfibres’andflaxshives’chemicalcompositionsareinaccordance withpreviouspublishedstudies[35 ,36 ].

Finally,themonosaccharidecontentsofthescutchingandcarding dustsareequivalent,withtheexceptionoftheglucosecontent,which isthelowestforCDat10%against16%forSD.Inthesefractions,a minoramountofbrokenfibresorshivesappearstobepresent,whichis consistentwiththemineralashcontentsmeasuredbypyrolysis(Section 3.1.c).

Theglucosecontentintheanalysedreinforcingflaxco-productsis directlycorrelatedwiththeirreinforcingefficiencyinPP-MAPP injec-tion mouldedcomposites,asseen inFig. 15 bya linearrelationship (R2=0.993).Thenaturalfibrecellwallsarereinforcedbycellulose or-ganisedinmicrofibrils,andtheirmechanicalpropertiesdependonthe cellulosecontent,specificthemicrofibrillarangle(MFA)andits crys-tallisationdegree[37] .Thecellulosecontentisnotsignificantly modi-fiedduringthemanufacturingprocessofinjectionmouldedcomposites [38] atrelativelylowtemperatures(celluloseandhemicellulosesbegin todegradeabove250°C[39] ).Thisstudythereforeshowsthatthe

glu-Fig.15. Tensilestrengthatbreakasfunctionofdrymattercontentofglucose in30%-wtreinforcedinjectionmouldedspecimen.

cosecontentisanaccurateindicatorofthereinforcingpotentialofflax stemproductsininjectionmouldedcomposites.

Thepresentresultsconfirmthatcardingdusthasabetter reinforc-ingpotentialthantalc,whichissimilartoflaxfinesparticles[7] . Re-gardingthescutchingdust,thepresenceofnumerousmineralparticles (Fig. 9 )canbeproblematicfortransformationtools(screws,dies, chan-nels,moulds)andcauseprematurebreakageorwear.Nevertheless,by sieving(forexample,byremovingthemineral-rich90andBotfractions inFig. 7 fandg),thequalityofthebatchesandtheaspectratioofthe re-inforcementscanbesimplyoptimised.Thus,afterminorimprovements, dustcanbeviewedasacredible,eco-friendly,andlow-costalternative formineralloadingsubstitutioninthermoplasticcompounds.

Conclusion

Thisstudyfocusedontherelevantmorphologicalparametersofa rangeofproductsobtainedfromthewholeflaxstem(flaxfibres,flax shives,anddusts)withtheaimofassessingtheirmechanical reinforce-mentpotentialforinjectionmouldingapplications.Thedynamicimage analysisusedforthisstudydeliveredaccurateinformationthrougha volumedistributionanalysis,particularlyconcernedwiththethree fi-brebatchlengthsof1mm,2mmand4mm.Thestudyoftheparticle diametershowedaslightdecreasewiththedecreaseinthefibrelength duetomoresevereshearstressesduringthecuttingprocess.Fragmented flaxshiveshaveanaspectratioofapproximately7.5,butamassfraction concentratedatthecoarsersizedparticles,namely,62%-wtofparticles betweenthe630μmand400μmmesh-sizedsieves.Furthermore,the dustsamplesoriginatingfromthescutchingandthecardingprocess,SD andCD,showverydistinctmorphologicalfeatures,notablyintermsof diameter,withmuchsmallermeandiametersforthecardingdust sam-ples.Interestingly,theSDsamplecontainsimportantamountsofsilica, implyingalargervolumeofmineralparticlesoriginatingfromthecrop cultivationfields.Thislargervolumeisconfirmedbyconsideringthe ashcontentofthetwosamplesfollowingpyrolysis.

Intermsofthemechanicalreinforcement,astrongcorrelation be-tweenthecellulosecontentofflaxstemproductsorafineparticle con-tentandmaximumtensile strengthwas demonstrated.Thisoutcome allowsi)thereinforcingroleofdifferentbiomassmaterialstobe esti-matedbasedontheamountofcellulose,whichisastablecriterionthat doesnotsignificantlyevolveduringthemanufacturingprocessandii) thestrongnegativeroleoffinestobeconfirmed,especiallyduetotheir verylowaspectratios.Furthermore,flaxshivesanddustshaveavery low-addedvalue;theiruseascompositereinforcementsisapotential additionalincomeforscutchingcentresandalsoawaytoincreasethe

biomassfractioninthermoplasticcompositesbycreatinglow-costbut competitivecompoundsintermsoftheirmechanicalproperties. DeclarationofCompetingInterest

Theauthorsdeclarethattheyhavenoknowncompetingfinancial interestsorpersonalrelationshipsthatcouldhaveappearedtoinfluence theworkreportedinthispaper.

Acknowledgements

TheauthorswouldliketothanktheNationalAssociationofResearch andTechnologyforfinancingathesisinpartnershipwithVanRobaeys FrèresandtheDupuydeLômeResearchInstituteoftheSouthBrittany University(France).Wewouldlike tothankSylvianeDaniel(INRAE, Nantes)forherskilfulhelpinthecarbohydrateanalysis,andAnthony Magueresse(IRDL,Lorient)fortheSEMimages.Furthermore,the au-thorswouldliketothanktheRégionBretagneandInterregV.A Cross-ChannelProgrammeforfundingthisworkthroughtheFLOWERproject (Grantnumber23).

Supplementarymaterials

Supplementarymaterialassociatedwiththisarticlecanbefound,in theonlineversion,atdoi:10.1016/j.jcomc.2020.100054 .

References

[1] A. Bourmaud, J. Beaugrand, D.U. Shah, V. Placet, C. Baley, Towards the design of high-performance plant fibre composites, Prog. Mater. Sci. 97 (2018) 347–408, doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2018.05.005 .

[2] K. Haag, et al., Influence of flax fibre variety and year-to-year variability on compos- ite properties, Ind. Crops Prod. 98 (2017) 1–9, doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.12.028 . [3] A.S. Doumbia, et al., Flax/polypropylene composites for lightened structures: mul- tiscale analysis of process and fibre parameters, Mater. Des. 87 (2015) 331–341, doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2015.07.139 .

[4] A. Kelly , W.R. Tyson , Tensile properties of fibre-reinforced metals: copper/tungsten and copper/molybdenum, J. Mech. Phys. Solids 13 (1965) 329–350 .

[5] G. Coroller, et al., Effect of flax fibres individualisation on tensile failure of flax / epoxy unidirectional composite, Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 51 (2013) 62–70, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2013.03.018 .

[6] A. Bourmaud, D. Åkesson, J. Beaugrand, A. Le Duigou, M. Skrifvars, C. Baley, Re- cycling of L -poly-(lactide)-poly-(butylene-succinate)-flax biocomposite, Polym. De- grad. Stab. 128 (2016) 77–88, doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2016.03.018 . [7] A. Bourmaud, C. Mayer-Laigle, C. Baley, J. Beaugrand, About the frontier between

filling and reinforcement by fine flax particles in plant fibre composites, Ind. Crops Prod. 141 (September) (Dec. 2019) 111774, doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111774 . [8] C. Mayer-Laigle, A. Bourmaud, D.U. Shah, N. Follain, J. Beaugrand, Unravelling the

consequences of ultra-fine milling on physical and chemical characteristics of flax fibres, Powder Technol. 360 (2020) 129–140, doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2019.10.024 . [9] N. Le Moigne, M. Van Den Oever, T. Budtova, A statistical analysis of

fibre size and shape distribution after compounding in composites rein- forced by natural fibres, Composits Part A 42 (10) (2011) 1542–1550, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2011.07.012 .

[10] K. Haag, J. Müssig, Scatter in tensile properties of flax fibre bundles: influence of determination and calculation of the cross- sectional area, J. Mater. Sci. 51 (2016) 7907–7917, doi: 10.1007/s10853-016-0052-z .

[11] J. Müssig, H.G. Schmid, Quality control of fibers along the value added chain by using scanning technique – from fibers to the final product, Microsc. Microanal. 10 (S02) (Aug. 2004) 1332–1333, doi: 10.1017/S1431927604884320 .

[12] J. Müssig, S. Amaducci, Scanner based image analysis to characterise the influence of agronomic factors on hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) fibre width, Ind. Crops Prod. 113 (2018) 28–37 December 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.12.059 .

[13] L. Teuber, H. Militz, A. Krause, Dynamic particle analysis for the evaluation of par- ticle degradation during compounding of wood plastic composites, Composits Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 84 (2016) 464–471, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2016.02.028 . [14] F. Berzin, J. Beaugrand, S. Dobosz, T. Budtova, B. Vergnes, Lignocellu-

losic fiber breakage in a molten polymer. Part 3. Modeling of the di- mensional change of the fibers during compounding by twin screw extru- sion, Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 101 (2017) 422–431 https://doi.org/, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.07.009 .

[15] S.E. Hamdi, C. Delisée, J. Malvestio, N. Da Silva, A. Le Duc, J. Beaugrand, X-ray computed microtomography and 2D image analysis for morphological characteriza- tion of short lignocellulosic fibers raw materials: a benchmark survey, Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 76 (2015) 1–9, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2015.04.019 . [16] F. Berzin, B. Vergnes, J. Beaugrand, Evolution of lignocellulosic fibre lengths along

the screw profile during twin screw compounding with polycaprolactone, Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 59 (2014) 30–36, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2013.12.008 .

[17] M. Graça Carvalho, P.J. Ferreira, A.A. Martins, M. Margarida Figueiredo, A compar- ative study of two automated techniques for measuring fiber length, Tappi J. 80 (2) (1997) 137–142, doi: 10.1201/9781420038064.ch4 .

[18] D. Guay , et al. , Comparison of fiber length analyzers, in: Proceedings of the 2005 TAPPI Practical Papermaking Conference, 2005, pp. 413–442 .

[19] J. Meyers , H. Nanko , Effects of fines on the fiber length and coarseness values mea- sured by the Fiber Quality Analyzer (FQA), in: Proceedings of the 2005 TAPPI Prac- tical Papermaking Conference, 2005, pp. 383–397 .

[20] N. Martin, P. Davies, C. Baley, Comparison of the properties of scutched flax and flax tow for composite material reinforcement, Ind. Crops Prod. 61 (2014) 284–292, doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.07.015 .

[21] L. Nuez, et al., The potential of flax shives as reinforcements for injection moulded polypropylene composites, Ind. Crop. Prod. 148 (March) (2020) 112324, doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112324 .

[22] A.B. Blakeney, P.J. Harris, R.J. Henry, B.A. Stone, A simple and rapid preparation of alditol acetates for monosaccharide analysis, Carbohydr. Res. 113 (2) (1983) 291– 299, doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(83)88244-5 .

[23] N. Blumenkrantz , G. Asboe-Hansen , New method for quantitative determination of uronic acids, Anal. Biochem. 54 (2) (1973) 484–489 .

[24] K. Albrecht, T. Osswald, E. Baur, T. Meier, S. Wartzack, J. Müssig, Fibre length reduction in natural fibre-reinforced polymers during compounding and injection moulding —experiments versus numerical prediction of fibre breakage, J. Compos. Sci. 2 (2) (2018) 20, doi: 10.3390/jcs2020020 .

[25] A. Le Duc, B. Vergnes, T. Budtova, Polypropylene/natural fibres composites: anal- ysis of fibre dimensions after compounding and observations of fibre rupture by rheo-optics, Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 42 (11) (2011) 1727–1737, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2011.07.027 .

[26] M. Tanguy, A. Bourmaud, J. Beaugrand, T. Gaudry, C. Baley, Polypropylene rein- forcement with flax or jute fibre; Influence of microstructure and constituents prop- erties on the performance of composite, Compos. Part B Eng. 139 (2018) 64–74 November 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.11.061 .

[27] J.C. Ludwick, P.L. Henderson, Particle shape and inference of size from sieving, Sed- imentology 11 (3–4) (1968) 197–235, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.1968.tb00853.x . [28] T. Allen , Powder Sampling and Particle Size Determination, Elsevier B.V., 2003 . [29] A. Bourmaud, S. Pimbert, Investigations on mechanical properties of

poly(propylene) and poly(lactic acid) reinforced by miscanthus fibers, Com-

pos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 39 (9) (2008) 1444–1454, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa. 2008.05.023 .

[30] R. Castellani, et al., Lignocellulosic fiber breakage in a molten polymer. Part 1. Qual- itative analysis using rheo-optical observations, Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 91 (2016) 229–237, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2016.10.015 .

[31] G. Ausias, A. Bourmaud, G. Coroller, C. Baley, Study of the fibre morphology stability in polypropylene-flax composites, Polym. Degrad. Stab. 98 (6) (2013) 1216–1224, doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2013.03.006 .

[32] A. Nourbakhsh, A. Karegarfard, A. Ashori, A. Nourbakhsh, Effects of particle size and coupling agent concentration on mechanical properties of particulate-filled polymer composites, J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 23 (2) (2010) 169–174, doi: 10.1177/0892705709340962 .

[33] R.C. Pettersen , The chemical composition of wood, in: The Chemistry of Solid Wood, CRC Press, 1985, pp. 57–126 .

[34] L. Soccalingame, A. Bourmaud, D. Perrin, J.-.C. Bénézet, A. Bergeret, Reprocessing of wood flour reinforced polypropylene composites: impact of particle size and cou- pling agent on composite and particle properties, Polym. Degrad. Stab. 113 (2015) 72–85, doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2015.01.020 .

[35] A.U. Buranov, G. Mazza, Extraction and characterization of hemicelluloses from flax shives by different methods, Carbohydr. Polym. 79 (1) (2010) 17–25, doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2009.06.014 .

[36] C. Mayer-Laigle, R. Rajaonarivony, N. Blanc, X. Rouau, Comminution of dry lig- nocellulosic biomass: part II. Technologies, improvement of milling performances, and security issues, Bioengineering 5 (3) (2018) 1–17, doi: 10.3390/bioengineer- ing5030050 .

[37] A. Bourmaud, C. Morvan, A. Bouali, V. Placet, P. Perré, C. Baley, Relationships be- tween micro-fibrillar angle , mechanical properties and biochemical composition of flax fibers, Ind. Crop. Prod. 44 (2013) 343–351, doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.11.031 . [38] C. Gourier, A. Le Duigou, A. Bourmaud, C. Baley, Mechanical analysis of elementary flax fibre tensile properties after different thermal cycles, Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 64 (2014) 159–166, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2014.05.006 .

[39] D. Siniscalco, O. Arnould, A. Bourmaud, A. Le Duigou, C. Baley, Mon- itoring temperature effects on flax cell-wall mechanical properties within a composite material using AFM, Polym. Test. 69 (April) (2018) 91–99, doi: 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2018.05.009 .