HAL Id: tel-03168272

https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03168272

Submitted on 12 Mar 2021

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Work and Family Trajectories in France

Fanny Landaud

To cite this version:

Fanny Landaud. Essays on Contextual Determinants of Educational, Work and Family Trajectories in France. Economics and Finance. Université Paris sciences et lettres, 2018. English. �NNT : 2018PSLEH097�. �tel-03168272�

THÈSE DE DOCTORAT

de l’Université de recherche Paris Sciences et Lettres

PSL Research University

Préparée à l’Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales

Essais sur les déterminants contextuels des trajectoires scolaires,

professionnelles et familiales en France

COMPOSITION DU JURY : M. PISTOLESI Nicolas

Professeur à TSE et à l’Université Toulouse 1 Capitole, Rapporteur

Mme. SOLAZ Anne

Directrice de recherche à l’INED, Rapporteur

Mme. BACACHE Maya

Professeur à Télécom ParisTech, Membre du jury

Mme. FACK Gabrielle

Professeur à l’Université Paris Dauphine, Membre du jury

M. MAURIN Éric

Directeur des études à l’EHESS, PSE, Membre du jury

Soutenue par Fanny LANDAUD

le 28 Septembre 2018

h

Ecole doctorale

n°

465

ECOLE DOCTORALE ECONOMIE PANTHEON SORBONNE

Spécialité

Sciences Économiques

Dirigée par Éric MAURIN

SCIENCESSOCIALES

ÉCOLE DOCTORALE: ED 465 – Économie Panthéon Sorbonne

THÈSE

Pour l’obtention du grade de docteur en Sciences Économiques de l’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales

Présentée et soutenue publiquement le 28 Septembre 2018 par

Fanny L

ANDAUDE

SSAIS SUR LES DÉTERMINANTS CONTEXTUELS DES

TRAJECTOIRES SCOLAIRES

,

PROFESSIONNELLES ET

FAMILIALES EN

F

RANCE

Sous la direction d’Éric MAURIN

Composition du jury :

Rapporteurs

Nicolas PISTOLESI Professeur à TSE et à l’Université Toulouse I Capitole Anne SOLAZ Directrice de recherche à l’INED

Examinateurs

Maya BACACHE Professeur à Télécom ParisTech

Gabrielle FACK Professeur à l’Université Paris Dauphine Directeur

SCIENCESSOCIALES

ÉCOLE DOCTORALE: ED 465 – Économie Panthéon Sorbonne

PHD THESIS

Submitted to École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics

Prepared and defended on September 28, 2018 by

Fanny L

ANDAUDE

SSAYS ON THE

C

ONTEXTUAL

D

ETERMINANTS OF

E

DUCATIONAL

, W

ORK AND

F

AMILY

T

RAJECTORIES IN

F

RANCE

Thesis Advisor: Éric MAURIN

Jury :

Reviewers

Nicolas PISTOLESI Professor at TSE and University Toulouse I Capitole Anne SOLAZ Professor at INED

Examinators

Maya BACACHE Professor at Télécom ParisTech

Gabrielle FACK Professor at University Paris Dauphine Advisor

Je tiens tout d’abord à remercier Éric Maurin qui a été un directeur de thèse exceptionnel. Éric a commencé à m’encadrer il y a maintenant cinq ans, pour mon mémoire de master. Pendant toutes ces années, Éric a été d’une disponibilité incroyable. Que ce soit pour nos collaborations, pour d’autres projets de recherche ou pour la recherche d’un post-doc, il

s’est toujours montré très à l’écoute et ses conseils m’ont été d’une grande aide. J’ai

énormément appris à ses côtés, et je lui en suis infiniment reconnaissante.

Je tiens également à remercier Gabrielle Fack qui a accepté de faire partie de mon comité de thèse et de mon jury, et m’a donné de nombreux conseils tout au long de ces dernières années. Je remercie aussi chaleureusement les rapporteurs de ma thèse, Anne Solaz et Nicolas Pistolesi, ainsi que Maya Bacache pour avoir accepté de consacrer du temps à mes travaux.

Cette thèse a été écrite à partir de nombreuses sources de données différentes, et je tiens à remercier les différentes institutions et personnes qui m’ont permis ou facilité l’accès à ces données. En particulier, je remercie Caroline Simonis-Sueur de la Direction des Études, de la Performance et de la Prospective du ministère de l’Éducation nationale et Daniel Lejeune du service statistique du concours Mines-Ponts. Je remercie également Isabelle Catto, Pascal Combemale et Sophie Giovachini pour m’avoir permis de collecter de nombreuses informations dans le cadre de ma mission complémentaire de recherche au sein de PSL, et Astrid Aulanier et Yagan Hazard qui m’ont assistée dans cette collecte. J’en suis aussi reconnaissante à Pascal Combemale pour m’avoir initiée et donné goût aux questionnements économiques.

J’ai bénéficié du soutien de très nombreuses personnes pour écrire cette thèse, et je tiens à leur exprimer ma gratitude. Je remercie l’ensemble des membres de l’École d’Économie de Paris pour m’avoir permis de travailler dans les meilleures conditions possibles. En par-ticulier, Béatrice Havet et Véronique Guillotin ont toujours su répondre à mes nombreuses questions administratives, et Radja Aroquiaradja a toujours été disponible pour mes ques-tions informatiques. Mes travaux de recherche ont également grandement profité de multi-ples interactions avec les professeurs de PSE, que ce soit en séminaire, autour d’une machine à café, ou d’un piano à Aussois.

Enfin, l’ensemble des doctorants m’ont beaucoup apporté, tant sur le plan professionnel qu’amical. Je tiens en particulier à remercier Malka Guillot et les membres du bureau A1

Briole et Son-Thierry Ly.

Cette thèse doit également beaucoup aux amis et famille qui m’ont entourée à chaque

instant. En particulier, Andréa, Charlotte, Chatoun, Corentin et Édith. Mes parents,

Philippe et Sophie ; mes sœurs, Adèle et Léna ; et mes grands-parents, Coco et Papet.

Cette thèse se compose de trois essais indépendants dont le dénominateur commun est d’étudier le rôle du contexte institutionnel et de l’environnement social dans lesquels se décident les trajectoires scolaires, professionnelles et familiales.

Une moitié environ des lycées parisiens (les plus prestigieux) reçoivent chaque année davantage de demandes d’admission de la part des collégiens qu’ils n’ont de places disponibles. Le logiciel d’affection utilisé (Affelnet) est contraint de définir, pour chacun de ces lycées, un niveau minimum (en termes de note moyenne obtenue en troisième) nécessaire pour l’admission. En comparant les trajectoires des derniers collégiens admis dans des lycées parisiens sélectifs avec celles des premiers recalés, nous montrons dans le premier chapitre que l’accès à un établissement scolaire sélectif n’a aucun impact sur les performances ultérieures au baccalauréat, mais un impact très négatif sur la propension des jeunes lycéennes à s’orienter dans la filière générale scientifique en fin de seconde. Dans le contexte parisien, l’accès à un lycée sélectif s’accompagne surtout d’une amélioration du niveau académique des camarades de classe, notamment en science. Nos résultats concorderaient donc avec les travaux d’économie et psychologie expérimentale suggérant que les filles seraient plus réticentes que les garçons à choisir des voies compétitives.

Le deuxième chapitre porte sur les effets des politiques de redoublement en classes préparatoires scientifiques, en distinguant les effets directs observés pour les redoublants eux-mêmes et les effets indirects induits sur les autres élèves au moment de la préparation des concours. Nous montrons que les redoublements ont des effets très largement positifs pour les redoublants eux-mêmes, mais que la présence de nombreux redoublants dans une classe a des effets plutôt négatifs pour les autres élèves, notamment quand ces redoublants sont forts académiquement. Plus une classe compte de redoublants de haut niveau académique (niveau mesuré lors de leur première participation aux concours) plus les nouveaux arrivants sont en difficulté au moment des concours, alors que les performances des nouveaux arrivants sont largement insensibles au nombre de redoublants de niveau moyen ou faible. Les redoublements ne semblent pas influer sur les autres élèves parce qu’ils contribuent à surcharger les classes, mais parce qu’ils en modifient le profil et peuvent induire les enseignants à produire des cours d’un niveau trop ambitieux.

Le troisième chapitre s’intéresse aux conséquences pour les trajectoires familiales de l’institutionnalisation des emplois précaires et des difficultés accrues rencontrées par les

rétrospectives sur de larges échantillons de jeunes adultes, et montrons que l’accès à l’emploi stable constitue une étape bien plus décisive que l’accès à un emploi précaire pour la mise en couple et l’arrivée des premiers enfants. Ainsi, entre les générations nées au milieu des années cinquante et celles nées au début des années soixante-dix, la montée de la part des emplois précaires et du chômage des jeunes expliquerait environ 25% des retards observés dans l’âge de mise en couple, et 40% des retards dans l’âge au premier enfant.

Discipline : Sciences économiques

This thesis is composed of three independent essays studying the role of the schooling and social environment in which individuals make their educational, work or family decisions.

The first chapter studies the impact of enrollment at a more selective Parisian high school on students’ performance and choice of field of study. We compare students’ educational outcomes depending on whether their 9thgrade standardized score fell just above or below an admission threshold, and we find that enrollment at a more selective high school has no impact on students’ performance but induces female students to turn away from scientific fields and settle for less competitive ones. Our results are consistent with lab-experiment findings on gender differences in attitude towards competition and bad grades.

The second chapter analyzes grade repetition in higher education and focuses on the spillover effects induced by grade repeaters on undergraduate freshmen. We distinguish between spillovers effects induced by higher- or lower- achieving repeaters to disentangle class size from composition effects, and we find that grade repetition generates little

congestion effects but has important negative composition effects. We show that the

performances of freshmen are very sensitive to the number of higher-achieving repeaters while they are not impacted by the number of lower-achieving repeaters. One potential mechanism would be distortion in teaching practices.

The last chapter studies the impact of temporary contracts and youth unemployment to explain observed delays in age at first cohabiting relationship and in age at first child. Using French data on the work and family history of large samples of young adults, this chapter provides evidence that access to permanent jobs has a much stronger impact than access to temporary jobs for family formation. According to our estimates, about 25% of the increase in age at first cohabitation and about 40% of the increase in age at first child observed during the second half of the century can be explained by the rise in unemployment and in the share of temporary jobs among young workers.

Field: Economics

Remerciements vii

Résumé en français ix

Summary in English xi

Introduction générale 1

1 Competitive Schools and the Gender Gap in the Choice of Field of Study 7

1 Introduction . . . 8

2 Institutional Context . . . 11

2.1 The Assignment of Middle School Students to High Schools . . . 11

2.2 Major Field of Study and High School Exit Exams . . . 13

2.3 Selective Undergraduate Programs . . . 14

3 Data and Methods . . . 15

3.1 Data . . . 15

3.2 Cut-off Scores . . . 16

4 Graphical Evidence . . . 17

4.1 First-Stage : Effect of Eligibility on Enrollment . . . 18

4.2 Field of Study at the End of 10thGrade . . . 19

5 Regression Results . . . 20

5.1 First Stage Effects on School Environment . . . 21

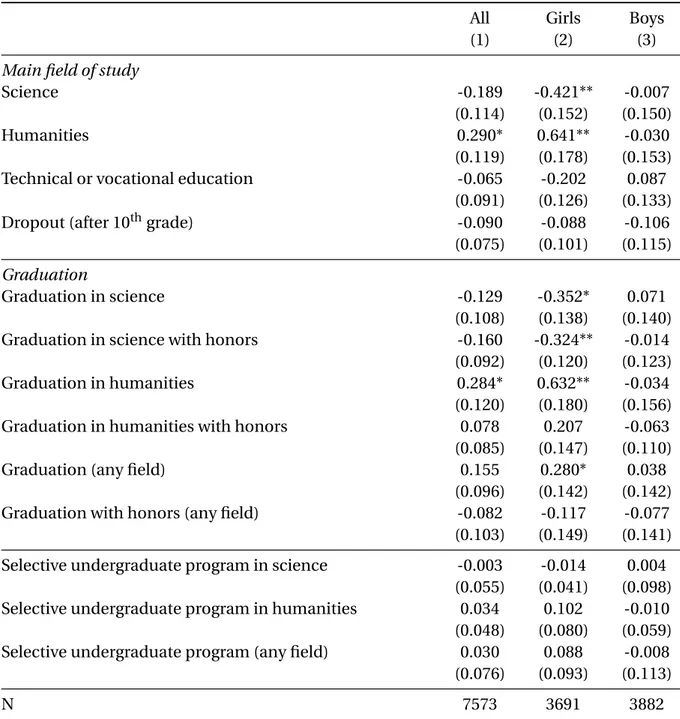

5.2 Major Field of Study and Performance on Exams . . . 23

5.3 Robustness and Falsification Tests . . . 24

6 Mechanisms . . . 25

6.1 Attitude towards Competition . . . 26

6.2 Rank Consideration . . . 26

6.3 Comparative Advantages and Capacity Constraints . . . 27

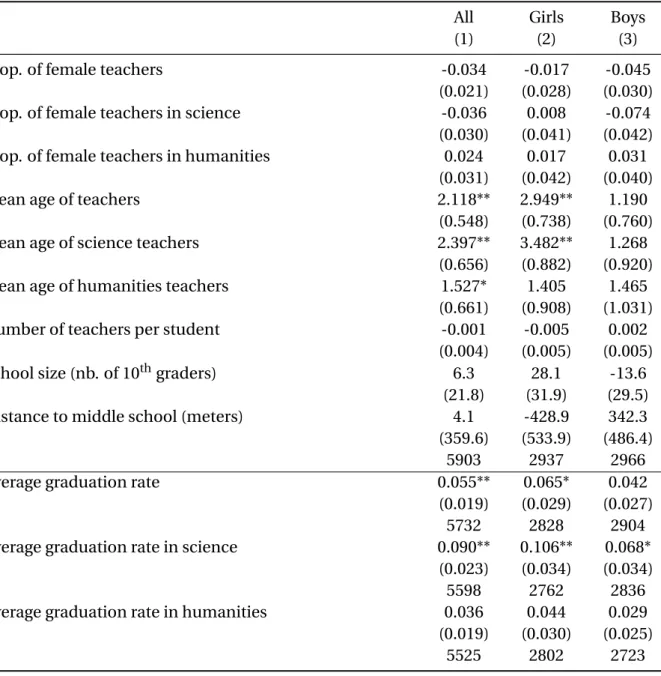

6.4 Teachers’ Characteristics . . . 29

7 Conclusion . . . 30

Appendices . . . 38

1.A Additional Tables and Figures . . . 38

1.B Cut-off Scores . . . 57

2 Les redoublants nuisent-ils aux autres étudiants ? Le cas des classes prépara-toires scientifiques 59 1 Introduction . . . 60

2.2 Les classes préparatoires . . . 65

2.3 Classes étoilées . . . 66

3 Données utilisées . . . 67

3.1 Les données du concours Mines-Ponts . . . 67

3.2 Les données du ministère . . . 68

3.3 Identification des étudiants qui redoublent après avoir été classés . . . 68

3.4 Échantillon de travail . . . 69

4 Les redoublants : profils et performances . . . 70

4.1 Les effets directs du redoublement sur les redoublants . . . 70

4.2 Le niveau académique des redoublants classés et non classés . . . 71

5 L’influence des redoublants sur les non-redoublants . . . 72

5.1 Effets des redoublements sur la taille des classes l’année suivante . . . 74

5.2 Effets des 5/2 sur les performances des 3/2 . . . 74

5.3 Redoublants classés vs. non classés . . . 75

6 Conclusion . . . 77

Annexe . . . 81

3 From Employment to Engagement ? Stable Jobs, Temporary Jobs, and Cohabiting Relationships 85 1 Introduction . . . 86

2 Stable Jobs, Temporary Jobs, and Cohabiting Relationships . . . 89

2.1 Data . . . 89

2.2 Event Study . . . 91

2.3 Timing of Events Analysis . . . 93

2.4 Stable Jobs, Temporary Jobs, Cohabiting Relationships and Fertility . . 98

3 Gender, Employment and Cohabiting Relationships before the 1950s . . . 99

3.1 Data . . . 99

3.2 Event Study . . . 101

3.3 Timing of Events Analysis . . . 102

4 Discussion . . . 103

5 Conclusion . . . 105

Appendix . . . 112

Conclusion générale 135

Avec la parution des ouvrages de Gary Becker "Human Capital, A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education" en 1964 et "A Treatise on the Family" en 1981, le champ de la science économique s’est progressivement élargi aux domaines de l’éducation et de la famille, jusqu’alors chasse gardée des sociologues.

Dans ces deux ouvrages, Gary Becker propose de modéliser les choix scolaires et les déci-sions relatives à la famille (mariage, naissance, divorce,...) comme des arbitrages purement individuels, très largement indépendants du contexte dans lequel ils sont rendus, essentiel-lement déterminés par les préférences et les ressources des individus décisionnaires eux-mêmes.

Depuis lors, de nombreuses recherches se sont attelées à compléter cette approche en sorte de mieux rendre compte de l’importance du contexte social dans lequel les décisions individuelles sont prises, notamment celles qui conditionnent les parcours scolaires ou les carrières familiales et professionnelles. Cette thèse s’inscrit dans cette lignée de travaux et présente trois essais dont le dénominateur commun est d’étudier le rôle du contexte institu-tionnel et de l’environnement social dans lesquels se décident les trajectoires individuelles.

Le premier chapitre de cette thèse étudie ainsi le rôle des camarades de classe dans les choix d’orientation des élèves de seconde générale de l’académie de Paris. Le second chapitre porte sur l’influence qu’ont les redoublants sur les autres élèves dans les classes préparatoires scientifiques, notamment au moment de la préparation des concours. Enfin, le troisième chapitre étudie la façon dont l’institutionnalisation des emplois précaires et les difficultés rencontrées par les jeunes pour s’insérer durablement dans l’emploi se répercutent dans les autres sphères de leur vie, en contribuant notamment à retarder l’âge auquel ils peuvent vivre en couple et avoir des enfants.

Pour de nombreux observateurs, il ne fait guère de doute que les élèves d’une même classe, voire d’une même école, s’influencent mutuellement, tant dans leurs comportements en classe que dans leurs choix d’orientation. En fait, il ne fait même guère de doute pour beau-coup que le mieux pour un enfant est d’avoir les meilleurs camarades de classe possibles. De nombreux parents s’attachent ainsi à protéger leurs enfants d’influences qu’ils jugent pro-blématiques en essayant de les scolariser avec des élèves du meilleur niveau scolaire pos-sible, que ce soit en choisissant des options réputées difficiles (comme le latin) ou en venant résider à proximité d’établissements réputés sélectifs.

Force est de constater qu’un élève est en moyenne d’autant plus performant à l’école que ces camarades le sont, ce qui semble apporter une justification aux stratégies des parents les plus inquiets. Pourtant, comme le souligne – par exemple – Joshua Angrist dans "The

Perils of Peer Effects", il n’est en réalité guère évident d’interpréter ce type de corrélation comme reflétant un effet proprement causal des camarades de classe, c’est-à-dire comme reflétant une véritable influence vertueuse qu’exerceraient les élèves les plus performants sur leur entourage. Les deux premiers chapitres de cette thèse utilisent les spécificités du système scolaire français – et notamment les spécificités du système d’affectation des collégiens dans les lycées Parisiens – pour revisiter cette question et essayer d’isoler l’influence réelle exercée par des camarades de classe d’un meilleur niveau académique. Paradoxalement, ces deux chapitres mettent en lumière que ces effets sont souvent bien loin de ce à quoi on les associe généralement et peuvent même être tout à fait contre-productifs. Dans le premier chapitre, nous montrons par exemple qu’être scolarisé dans un lycée plus sélectif avec de meilleurs élèves n’apporte aucun bénéfice scolaire au moment du baccalauréat, mais détourne les filles de la filière scientifique, la plus prestigieuse et recherchée. Dans le second chapitre, nous nous intéressons aux classes préparatoires scientifiques et démontrons que les redoublants les plus forts académiquement tendent à y déprimer les performances aux concours de leurs camarades de classe non-redoublants.

Le premier chapitre – coécrit avec Son-Thierry Ly et Éric Maurin et intitulé "Competitive Schools and the Gender Gap in the Choice of Field of Study" – s’inscrit dans deux courants de la littérature : celui analysant la sous-représentation des femmes en science et celui étudiant l’effet d’être admis dans un établissement scolaire sélectif.

S’agissant du premier courant de recherches, il s’est intéressé au rôle joué par les différences de capacités cognitives, d’aspirations ou de préférences existant entre hommes et femmes pour expliquer la sous-représentation des femmes dans les domaines scientifiques, lesquels sont également les domaines les plus rémunérateurs (voir par exemple Zafar, 2013 ; Stinebrickner et Stinebrickner, 2014 ou Wiswall et Zafar, 2015). Dans un autre registre, Joensen et Nielsen (2009) ; Carrell, Page et West (2010) ; Lavy et Sand (2015) ou Jackson (2012) et Eisenkopf et al. (2015) ont souligné l’importance de facteurs plus institutionnels pour expliquer le déficit de femmes en sciences. Ces recherches ont notamment étudié le rôle des enseignants et des pratiques enseignantes comme facteurs explicatifs potentiels des trajectoires des filles et des garçons. Face à ce corpus de recherches, l’apport de notre premier chapitre est d’identifier un autre déterminant de la sous-représentation des femmes en sciences, à savoir la sélectivité de l’environnement scolaire dans lequel elles sont amenées à faire leurs choix. En concentrant l’analyse sur les lycées parisiens les plus sélectifs et en comparant les trajectoires des derniers collégiens admis dans ces lycées avec celles des premiers recalés (au sens du score utilisé par le logiciel d’affectation des élèves, Affelnet), nous démontrons que l’accès en fin de troisième

à un lycée plus sélectif n’a aucun impact sur les performances ultérieures au baccalauréat, mais un impact très négatif sur la propension des jeunes filles à choisir la filière scientifique à l’issue de leur année de seconde (les choix d’orientation des garçons restant quant à eux totalement insensibles au lycée fréquenté). Ces résultats font écho aux travaux d’économie et de psychologie expérimentale qui suggèrent que les filles tendent à être plus rétives que les garçons à entrer en compétition avec leurs camarades (voir par exemple Niederle et Vesterlund, 2007, 2011 ; Croson et Gneezy, 2009 ; ou Buser, Niederle et Oosterbeek, 2014). Dans la mesure où l’accès à un lycée sélectif accroît surtout la compétition dans les matières scientifiques (ce que semble confirmer l’étude de l’évolution des classements des élèves dans les différentes matières après la troisième), l’aversion spécifique pour la compétition des jeunes filles pourrait expliquer leur rejet des mathématiques en fin de seconde dans les lycées les plus cotés. Au-delà de la question des filles et des sciences, ce premier chapitre contribue également à la littérature sur l’impact des établissements sélectifs. Cette littérature a principalement étudié le rôle des établissements sélectifs sur les performances scolaires (voir par exemple Pop-Eleches et Urquiola, 2013 ou Abdulkadiro˘glu, Angrist et Pathak, 2014). Les spécificités du système français nous permettent d’élargir cette perspective et d’étudier les effets sur les choix d’orientation des élèves, jamais envisagés jusqu’à présent.

Le second chapitre de cette thèse – coécrit avec Éric Maurin et intitulé "Les redoublants nuisent-ils aux autres étudiants ? Le cas des classes préparatoires scientifiques" – propose une analyse des effets des politiques de redoublement, en distinguant les effets directs observés sur les redoublants eux-mêmes et les effets indirects induits sur les autres élèves. L’une des originalités de notre analyse est de porter non pas sur l’enseignement primaire ou secon-daire (comme l’immense majorité de la littérature sur le redoublement), mais sur l’une des filières de l’enseignement supérieur, à savoir celle des classes préparatoires scientifiques.

Le redoublement est une pratique largement répandue dans les premiers cycles de l’en-seignement supérieur, notamment les plus sélectifs (médecine, droit, classes préparatoires, ...). Pourtant, il n’existe que peu d’éléments attestant de son efficacité dans ce contexte. À notre connaissance, il n’existe même qu’un seul article ayant abordé la question du re-doublement dans l’enseignement supérieur, à partir de données obtenues d’une université Suisse (voir Tafreschi et Thiemann, 2016). Dans ce chapitre, nous rassemblons un ensemble de données administratives retraçant (pour la période 2011-2016) les résultats aux concours d’écoles d’ingénieurs obtenus par les élèves de classes préparatoires scientifiques avant et après un éventuel redoublement. Ces données permettent tout d’abord de démontrer très directement un premier résultat qui n’avait jamais été établi rigoureusement, à savoir que le redoublement de la dernière année de classe préparatoire permet un accroissement très net

des performances aux concours pour une très grande majorité des redoublants concernés (accroissement que nous quantifions précisément).

Au-delà des redoublants eux-mêmes, les redoublements sont susceptibles d’affecter les autres élèves, ne serait-ce que parce qu’ils contribuent à augmenter la taille des classes et à rendre a priori plus difficiles les conditions d’enseignement. Il n’existe à notre connaissance que deux articles ayant abordé la question des effets indirects des politiques de redoublement et tous deux portent sur l’enseignement secondaire (Lavy, Paserman et Schlosser, 2012 et Hill, 2014). Notre travail est ainsi le premier à analyser les effets induits par les redoublements sur les non-redoublants dans l’enseignement supérieur. L’un des intérêts des données disponibles est de permettre de distinguer deux types de redoublants selon le niveau académique qu’ils avaient atteint en fin de première année. Notre analyse révèle que les redoublants de niveau moyen ou faible (à l’aune de leurs résultats aux concours l’année précédant le redoublement) n’ont aucun effet sur les non-redoublants, même quand ils contribuent à augmenter très significativement la taille des classes. Les effets de congestion liés à la taille des classes semblent ainsi relativement négligeables dans le contexte des classes préparatoires. Les seuls redoublants apparaissant exercer une influence sur les autres élèves de leur classe de Mathématiques Spéciales sont finalement les redoublants les plus forts académiquement, ceux qui étaient admis dans une très bonne école et n’ont redoublé que dans le but d’accéder à une école plus prestigieuse encore. En outre, nous révélons que cette influence tend à être négative : plus la classe compte de redoublants de haut niveau académique, plus les non-redoublants sont en difficulté au moment des concours, notamment dans les classes dites "étoilées", où précisément se concentrent les meilleurs redoublants. Les redoublants les plus forts ne semblent ainsi générer aucun des effets d’entraînement vertueux attribués traditionnellement aux bons élèves, mais semblent en revanche induire les enseignants à produire des cours d’un niveau trop ambitieux pour la moyenne des nouveaux arrivants.

Le dernier chapitre de cette thèse s’intéresse à des effets de contexte d’une autre nature. Dans ce chapitre – intitulé "From Employment to Engagement ? Stable Jobs, Temporary Jobs, and Cohabiting Relationships" – nous abordons en effet la question des déterminants des trajectoires professionnelles et familiales. Depuis les années soixante-dix, l’âge de la pre-mière cohabitation conjugale et l’âge au premier enfant ont nettement reculés en France (voir par exemple Prioux, 2003 et Pison, 2018). Ces évolutions coïncident avec d’importants changements de normes sociales, symbolisés par les revendications de Mai 68 et matérialisés entre autres par les lois Neuwirth ou Veil. Ces changements de normes se sont accompagnés d’un accroissement de la demande d’éducation des filles et d’un recul notable de leur âge de fin d’études. La question se pose toutefois de savoir si ces changements de normes sociales

peuvent être tenus pour seuls responsables du recul de l’âge auquel se forment les familles. Dans ce chapitre, nous étudions un autre élément de contexte susceptible d’avoir influé sur les trajectoires familiales : l’augmentation du chômage des jeunes et l’institutionnalisation des contrats précaires à l’entrée de la vie active.

Ce dernier chapitre s’inscrit ainsi dans la vaste littérature sur les liens entre l’accès à l’em-ploi et la formation de la famille (voir par exemple Ekert-Jaffé et Solaz, 2001 ; Prioux, 2003 ; Adsera, 2005 ou Goldstein et al., 2013). Notre principale contribution est de mettre en lu-mière l’importance de la nature de l’emploi obtenu – stable ou précaire – dans la décision d’emménager avec son conjoint, puis d’avoir des enfants. D’un point de vue méthodolo-gique, il n’est guère aisé d’identifier le sens et l’ampleur des liens de causalité susceptibles d’exister entre l’accès à l’emploi et la formation de la famille. La corrélation existant entre la date du premier emploi et la date de la première cohabitation peut tout autant indiquer un lien causal de l’emploi vers le couple qu’un lien causal du couple vers l’emploi, voire de simples effets de sélection. Afin d’éclairer ces questions, ce chapitre développe une analyse de durée utilisant le modèle d’Abbring et van den Berg, 2003. Sous l’hypothèse que les indivi-dus ne peuvent anticiper longtemps à l’avance les dates exactes d’obtention de leur premier emploi ou de formation de leur premier couple (ou, en tous cas, ne prennent pas de déci-sions en lien avec ces événements plusieurs mois en amont), le modèle d’Abbring et van den Berg permet d’identifier les liens de causalité entre accès à l’emploi et formation de la famille. L’utilisation de ce modèle – menée sur deux enquêtes retraçant les trajectoires pro-fessionnelles et familiales d’un large échantillon de jeunes adultes – révèle qu’un premier emploi stable a un impact nettement plus important sur la mise en couple qu’un emploi précaire (et quantifie précisément la différence). Nos résultats révèlent par ailleurs que la stabilité de l’emploi importe également pour la décision d’avoir un enfant. Nous démon-trons également que les liens entre emploi, cohabitation et genre ont beaucoup évolué au fil des générations. Pour celles nées avant le milieu des années cinquante, l’emploi consti-tuait plus fréquemment une condition nécessaire pour fonder une famille chez les hommes que chez les femmes et la mise en couple jouait un rôle très négatif sur la participation des femmes au marché du travail. Pour les générations suivantes, les liens entre mise en couple et emplois apparaissent bien plus similaires entre hommes et femmes. D’une génération à l’autre, la montée du chômage des jeunes et de la part des contrats précaires expliquerait environ 25% des retards observés dans l’âge à la première mise en couple et environ 40% des retards dans l’âge au premier enfant.

Competitive Schools and the Gender Gap in the

Choice of Field of Study

JOINT WITHSON-THIERRYLY ANDÉRICMAURIN

Abstract

In most developed countries, students have to choose a major field of study during high school. This is an important decision as it largely determines subsequent educational and occupational choices. Using French data, this paper reveals that enrollment at a more selec-tive high school, with higher-achieving peers, has no impact on boys, but a strong impact on girls’ choices: they turn away from scientific fields and settle for less competitive ones. Our results are not consistent with two commonly-advanced explanations for gender differences in field of study, namely disparities in prior academic preparation and in sensitivity to rank in class.

1 Introduction

In most developed countries, male and female students still choose very different major fields of study during high school or during college. In French high schools for instance, male students are about 40% more likely than female students to specialize in science1. These gender differences have attracted considerable attention as they likely explain a significant part of labor market differentials across gender groups. The choice of science as a major field of study is typically associated with the best prospective outcomes, but female students are still dramatically underrepresented in this field.

A long-standing literature has explored the causes of the gender gap in the choice of field of study, with a specific emphasis on gender differences in ability, expectations or preferences. Several influential studies have also emphasized the role of teaching practices

and teachers’ stereotypes2. In this paper we analyze the role of another potential

determinant of students’ choices, namely the school environment in which they make their decisions. Specifically we look at whether the choice of field of study of girls and boys depends on the academic level of the schoolmates with whom they have to compete. In more selective schools, with higher-achieving peers, students may be induced to form new expectations about their chances of success in the different fields, which may eventually affect their choices.

It has long been recognized that enrollment at a more selective school, with higher-achieving peers, may affect students’ subsequent performance and graduation probability, even though empirical evidence are mixed (see Pop-Eleches and Urquiola, 2013 or Abdulkadiro˘glu, Angrist and Pathak, 2014 for example). Much less is known, however, on whether enrollment in selective schools affects students’ choice of field of study. One basic reason for this lack of evidence is that the choice of major field of study often occurs at the same time as the high school choice, so that it is logically very difficult to define the impact of the latter on the former. Another basic difficulty is that the choice of enrolling in a more

1See Direction de l’évaluation, de la prospective et de la performance (2014). The requirement to choose

major fields of study during high school is not specific to the French system. Similar requirements exist in the UK, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Denmark, Norway or Korea for instance. For evidence on the gender gap in field of study in secondary education, see for example Buser, Niederle and Oosterbeek (2014) for the Netherlands; Joensen and Nielsen (2016) for Denmark; Office for Standards in Education (OFSTED) for the UK; Buser, Peter and Wolter (2017) for Switzerland. For evidence on the gender gap in the choice of field of study in US post-secondary education system see for example Chen and Weko (2009).

2For an analysis of teachers and teaching practices, see Carrell, Page and West (2010); Joensen and Nielsen

(2009); Lavy and Sand (2015). For an analysis of the role of attitude towards competition, see Croson and Gneezy (2009); Niederle and Vesterlund (2011, 2010); Buser, Niederle and Oosterbeek (2014). For an analysis of gender differences in preferences and expectations see Zafar (2013).

selective school and the choice of field of study likely depend on the same explanatory factors, such as students’ willingness to compete. In such a context, where two decisions potentially share the same causes, it is typically very hard to evaluate the influence that they exert on each other, even when they do not take place at the same time. Students enrolled in selective schools tend to choose more demanding fields of study, but it does not follow that their choice is influenced by their school environment.

In this paper, we build on the features of the Parisian high school system to overcome these issues. One first feature of this system is that middle school students are assigned to high schools through a centralized process that gives priority to students with the best average grades in middle school. About half of high schools receive more applications than they have places to offer and enrollment at each of these schools is restricted to students whose middle school average grade is above a specific cut-off level computed by the system. The second basic feature of the system is that students do not have to choose their major field of study at the start of high school, but only after one year of familiarization (that is, grade 10). In this context, it is possible to isolate the impact of enrollment at an oversubscribed high school on subsequent choices of field of study by comparing students whose middle school achievements were either just above or just below the specific cut-off level of this more selective high school.

This Regression Discontinuity (RD) analysis first confirms that eligibility for enrollment in a more selective school is associated with a very significant increase in the ability level of high school peers. It also reveals that this increase in peer ability is even more significant in science than in humanities, so that enrollment in a more selective school is first and foremost associated with an increase in competition in science. Importantly these first stages effects on peer ability are very similar for boys and girls, consistent with the assumption that, in our set-up, there is no gender gap in the willingness to attend higher ranked schools.

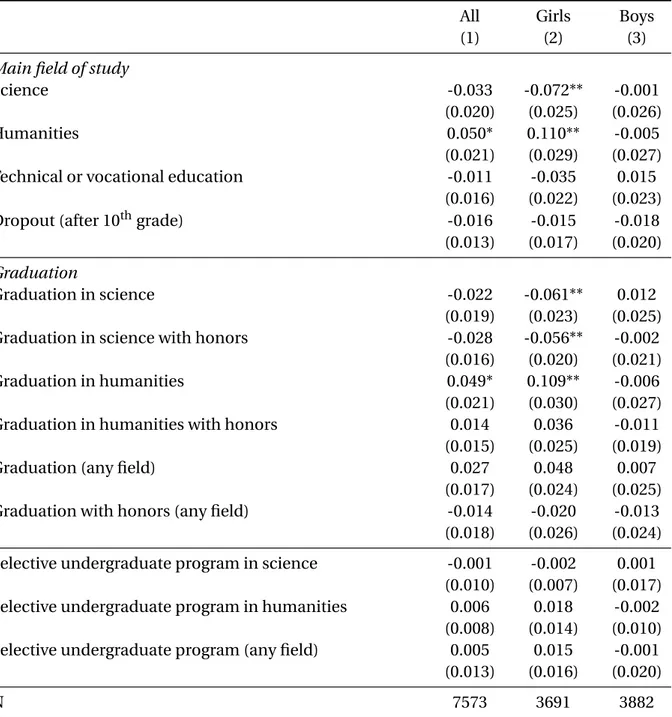

By contrast, eligibility for admission into a more selective school, with higher-achieving peers, has very different effects on the choice of major field of study made by boys and girls one year later, at the end of grade 10. Specifically, it has no effect on boys, but induces a significant decrease in the probability that girls choose science and a symmetrical increase in the probability that they choose humanities. Eventually, enrollment at a more selective school is not followed by any significant change in students’ overall graduation probability, but by a significant decrease in the share of girls who graduate in science.

Generally speaking, our results are consistent with experimental findings showing that female students are more likely to turn away from competitive settings than their male counterparts (Croson and Gneezy, 2009; Niederle and Vesterlund, 2011). They are also consistent with Rask and Tiefenthaler (2008) or Goldin (2015), who suggest that female students tend to be more responsive to a decline in performances than males. Our paper contributes to showing the decisive impact of these gender differences on the choices made

by girls and boys during high school. Because science is the field of study where

competition increases the most in sought-after schools, gender differences in attitudes towards grades and competition appear to induce many female students to turn away from science. Our findings are also reminiscent of the literature on college major choice in the US and on the role played by students’ expectations in this choice (Stinebrickner and Stinebrickner, 2014; Wiswall and Zafar, 2015). In a related contribution, Arcidiacono, Aucejo and Hotz (2016) show that the probability that a minority student graduates in science may be much lower in more selective Californian universities than in less selective ones.

Finally, our paper contributes to the literature on the effect of going to a more selective school, with higher-achieving peers (Abdulkadiro˘glu et al., 2017; Clark and Del Bono, 2016; Cullen, Jacob and Levitt, 2006; Jackson, 2013). Several recent papers build on a similar regression discontinuity design to provide evidence on the effect of selective schools on students’ performance in various institutional contexts (Abdulkadiro˘glu, Angrist and Pathak, 2014; Dobbie and Fryer Jr, 2014; Pop-Eleches and Urquiola, 2013). This literature

finds mixed evidence on the impact of elite schools on student academic performance3.

Because French students have to choose a major field of study at the end of their first year of high school, we are able to look not only at the impact on academic performance, but also on the choice of field of study. The effect of gaining admission to a more selective school appears to be much stronger on field of study than on academic performance. There is a small recent literature which documents similar findings about tracking within schools (He, 2016; Dougherty et al., 2017).

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the institutional context. Section 3 describes our administrative data sources while Section 4 provides basic graphical evidence on the impact of being eligible for admission into a selective school on students subsequent choices of field of study or graduation probabilities. Section 5 develops our Regression

Dis-3Most studies on elite schools in the US find little or no effects on academic achievement (Cullen, Jacob

and Levitt, 2006; Abdulkadiro˘glu, Angrist and Pathak, 2014; Dobbie and Fryer Jr, 2014), but positive effects are found in other contexts (Jackson, 2010; Estrada and Gignoux, 2017; Pop-Eleches and Urquiola, 2013). There is a small related literature on the impact of students’ rank within their school on their subsequent academic performance (see Murphy and Weinhardt, 2014).

continuity analysis. Section 6 explores the candidate mechanisms that may explain that more competitive school contexts induce female students to turn away from science.

2 Institutional Context

In this section, we provide information on how middle school students are assigned to high schools in Paris as well as on the exams that they have to take and the choices that they have to make during their high school years. In the following sections, the main research question will be whether the high school to which a middle school student is assigned affects her subsequent choices and performance on exams.

2.1 The Assignment of Middle School Students to High Schools

In France, middle school runs from grade 6 to grade 9. Students complete grade 9 the year they turn 15. The curriculum is the same in all middle schools and there is no streaming by ability. At the end of grade 9, students enter into high school, which runs from grade 10 to grade 12. This paper focuses on students who completed 9thgrade in public middle schools in the education region of Paris, in either 2009 or 2010.

France is divided into thirty education regions and the education region of Paris represents about 3% of French middle school students. In this region, there are about 100 public middle schools and about 50 public high schools where middle school students can pursue general education courses. Middle school students are assigned to public high schools through a centralized process called Affelnet, which is completely gender-blind and which is described in detail in Hiller and Tercieux (2014) or in Fack, Grenet and He (2015). Students are first asked to list up to six choices of public high schools in descending order of preference4. Paris is divided into four geographical districts (West, East, North, and South), and there is a very strong incentive to apply to high schools in one’s district of residence since the system gives priority to home-district over out-of-district applications. Also, within each district, a priority is given to low-income students, namely the 20% students eligible to means-tested financial assistance. For the other students, the system ranks their

applications according to the average of their 9th grade marks across all subjects and

assigns them to as many seats as possible using a deferred acceptance algorithm (Roth,

4Students from public middle schools can also apply to private high schools, but this is not processed by

Af-felnet. As discussed below, we checked that eligibility for admission into a more selective public high school has

no effect on the probability that students from public middle schools go to a private high school. Students from private middle schools can also apply to public high schools, but their applications are processed separately, after those of students from public middle schools.

1982) and a multi round process5. There are twelve subjects (Mathematics, Physics, Biology, Technology, French, History/Geography, Sport, two foreign languages, Art, Music and Discipline) and the marks used to compute the average score used by the system are first standardized at the region level. Standardization amounts to weighting each mark by the inverse of its standard deviation. These weights being revealed only ex post (that is, after all students have submitted their choices), the weighted average marks used by the system are ex ante impossible to precisely predict or manipulate.

In substance, the algorithm first assigns the students with the best 9th grade average marks to their preferred schools until one school starts being oversubscribed. This top school is then dropped from the application lists of the remaining (not yet assigned) students. These students are then re-ranked and the process is reiterated until another school starts being oversubscribed, and so on. At the end of this first round, there are no seats left in a fraction of schools (that is, the oversubscribed ones), whereas the other fraction is still undersubscribed. Similarly, a fraction of students are assigned to one of the schools of their list whereas the other fraction are still unassigned (that is, they applied for oversubscribed schools only). To further improve the assignment rate, each unassigned student is then asked to form new choices, namely to apply to at least one of the undersubscribed schools, and the process is reiterated. At the end of this second round, some students are still unassigned, and the education administration helps them find a seat in one of the remaining undersubscribed schools in an informal way. Undersubscribed schools are typically those that end up admitting a significant proportion of out-of-district students.

The key feature of this assignment process is that it is possible to define a minimum admission score for a large fraction of high schools, namely the oversubscribed ones. As discussed below, in years 2009 and 2010, about half of the public high schools of the region of Paris appear to be oversubscribed, with very significant discontinuities in the rate of enrollment of students at specific cut-off points of the distribution of 9thgrade scores. This feature will make it possible to build on a regression discontinuity analysis to evaluate the effect of being admitted to these schools on subsequent educational outcomes. Specifically, we will focus on students whose 9th grade scores fall either just above or just below the cut-off point of an oversubscribed school and we will compare the outcomes of those just above with those just below. The vast majority of these students continue general education in high school, and the question will be whether enrollment at a higher ranked school affects either their major field of study in high school or the level of their academic

performance6.

Generally speaking, our research strategy relies on the assumption that individual 9th grade scores and schools’ minimum admission scores cannot be manipulated and predicted. As discussed above, there is little scope for manipulation of individual scores. With respect to schools’ minimum admission scores, they depend on many factors that are no easier to predict than individual scores, such as the exact number of low-income students and the exact distribution of their choices across schools in each district. In this set up, there is again little scope for manipulation or prediction7. As discussed below, we find no evidence of discontinuities in the density of individual scores – or in students’ pre-assignment characteristics – at the cut-off.

2.2 Major Field of Study and High School Exit Exams

At the end of their first year of high school (grade 10), French students can either pursue general education or enter a technical or a vocational education program. Furthermore, those who pursue general education have to choose a major field of study. There are three possible fields: science (field "S"), economics and social sciences (field "E/S") or languages and literature (field "L"). The number of students per school and field of study is not set once and for all. It can vary significantly from one year to another so as to meet the choices of students8. At the end of 10thgrade, students are asked the field of study that they prefer and, eventually, the vast majority is allowed to pursue the track that they prefer. This is a key choice: each field of study corresponds to a very specific curriculum, specific high school examinations, and specific opportunities after high school.

For example, for those who choose to specialize in science, the scientific subjects represent 50% to 60% of compulsory courses in grade 11 and 12. By contrast, for those who choose to specialize in languages and literature, scientific subjects represent less than 5% of compulsory courses. With respect to post-secondary education, it is virtually impossible to enter an engineering school or a medical school after non-scientific studies in high school9.

6It should be emphasized that no school is oversubscribed with low-income students (the maximum

pro-portion of low-income students is 60%). Hence, there is no school that can define a minimum admission score for low-income students. Minimum admission scores are defined for non low-income students only.

7We checked that most schools do not have the same minimum admission score for the first and for the

second cohort. About half of schools do not even have the same exact rank within their district (in terms of minimum admission score) from one cohort to another.

8We checked that the number of students who choose science as major field of study actually varies

signifi-cantly from one year to the other within most schools. The within-school variation rate is on average 10%.

9According to a national longitudinal survey conducted by the Ministry of Education (so called Panel d’élèves

du second degré, recrutement 1995), only about 1% of students who graduate in humanities pursue a science

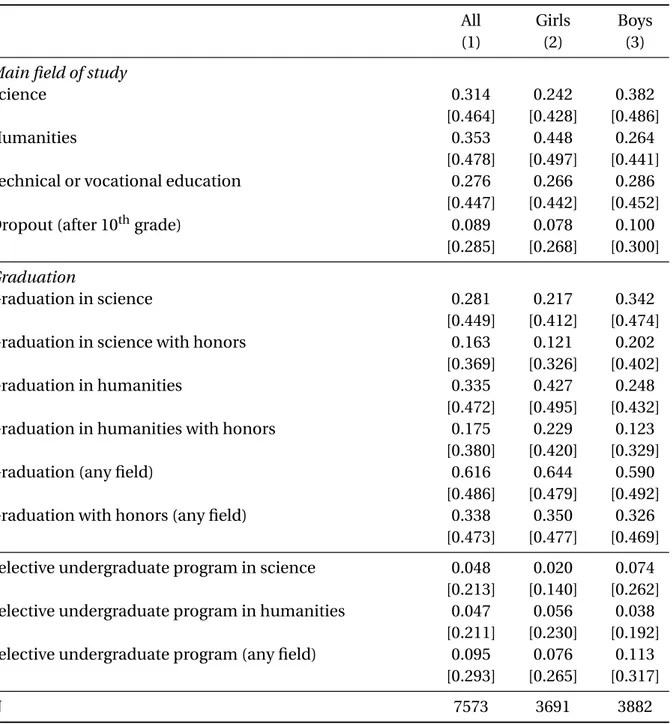

Generally speaking, science is the most prestigious field of study. Students in the scientific track performed on average 60% of a standard deviation higher in middle school than students in the social sciences track and 75% of a standard deviation higher than those in the languages and literature track. In our working sample, about 31% of students choose the scientific track, 13% specialize in literature and languages, 22% specialize in social sciences whereas about 34% opt for a more technical or vocational program, or drop out from education.

The first year of high school (grade 10) is dedicated to exploring the different subjects and to choosing a major field of study. After this exploration year, students have very little leeway to change their major field of study. In Paris, only about 2.5% of students change their major field of study after 10th grade. The two last years of high school (11th and 12th grade) are dedicated to the preparation of the national high school exit exam, the baccalauréat, which is a prerequisite for entry into post-secondary education. Students have to take one exam per subject, and they obtain their diploma if their weighted average mark across subjects is 10/20 or more, where subjects taken and weights depend strongly on the major field of study. For instance, the weights of exams in scientific subjects represent about 50% of the total for students who choose these subjects as major field of study, whereas the weights of these subjects is only about 20% for those who choose social sciences and 5% for those who choose languages and literature. Most exams are taken at the end of 12thgrade, except for exams in French (oral and written) which are taken at the end of 11thgrade. Students whose weighted average mark across subjects is 12/20 or more graduate with honors. Graduation with honors is granted to about half of the students each year in each field.

2.3 Selective Undergraduate Programs

High school graduation is a prerequisite for admission into post-secondary education programs. About half of these programs are selective, and selection depends on the grades obtained in the two last years of high school as well as on students’ ranks within their class. The Classes Préparatoires aux Grandes Écoles (CPGE) are among the most prestigious such selective programs. These two-year programs prepare students to take the entry exams of the most prestigious graduate programs (so called Grandes Écoles). The last important question addressed in this paper is whether enrollment at a more selective high school at the end of grade 9 affects the subsequent probability of gaining access to CPGE programs at the end of grade 12.

for entry exams at engineering graduate schools), some are specialized in economics and business (they prepare for entry exams at business schools) and some are specialized in lit-erature and languages (they prepare for entry exams at top graduate programs in this field). Each year, in Paris, about 20% of students from high school general education programs gain access to a CPGE. The vast majority graduate from high school with honors. When a student applies to a CPGE program, her high school has to provide the average marks (as assessed by teachers) that the student obtained in each subject for each quarter during 11thand 12th grade, as well as the corresponding rank within their class. Hence students from more selec-tive high schools may benefit from the prestige of their schools, but may suffer from being less well ranked within their class.

3 Data and Methods

3.1 Data

In our empirical analysis, we use administrative data providing detailed information on

students who finished middle school (9th grade) in either 2009 or 2010 in the education

region of Paris. For each student, we know the high school to which she was assigned after 9th grade, the field of study chosen at the end of 10th grade as well as the field of study in which she graduated at the end of 12thgrade. For each student, we also know whether she repeated a grade during high school, whether she dropped out from education before graduation and whether she got admitted into a CPGE program after high school.

With respect to students’ academic performance, we know the average marks given by teachers in each subject during 9thgrade as well as results at the national exams taken in Mathematics and French at the end of 9thgrade (externally set and marked). We also know students’ results at the national examination (baccalauréat, externally set and marked) taken at the end of high school (12th grade). As discussed previously, the score used to assign middle school students to high schools corresponds to an average of the average marks given by 9thgrade teachers.

To construct this dataset, we used schools’ registration records as well as administrative records with exhaustive information on results at the end of middle school and at the end of high school national exams, for each year between 2009 and 2014. We were able to match these different data sources using students’ ID number.

school-level administrative datasets, namely information on high school size as well as on the proportion of female teachers and on the distribution of teachers’ age.

3.2 Cut-off Scores

In this section, we consider the 52 public high schools which enter the centralized assignment system in 2009 or 2010. For each cohort and each district, we focus on the 9th grade students whose applications went through the standard assignment process, that is,

they are not low-income and come from a public middle school of the district10. Our

purpose is to identify the public high schools which received more applications than they could accommodate, and to estimate the lowest 9thgrade score that students had to earn to gain admission into these schools.

Our data do not provide information on students’ rank order lists, so that it is not possible to identify which schools are oversubscribed (and their minimum admission scores) directly from the data. To overcome this issue, we built on a method developed by Hansen (2000). Among all possible minimum admission scores, the method first identifies for each school those which coincide with a significant discontinuity in enrollment rates. If any such thresholds exist, the method amounts to choosing for each school the specific threshold

which corresponds to the most significant discontinuity. More details on how we

implemented this procedure are provided in Appendix 1.B.

This method was used by Card, Mas and Rothstein (2008) to estimate for each large American city the minimum proportion of minorities above which white residents start to flee a neighborhood. This method was also used by Hoekstra (2009) in his analysis of the benefits of attending a flagship university. In a recent contribution, Porter and Yu (2015) show that RD estimates and standard errors are unaffected when we use this two-stage method, where cut-offs are estimated first, followed by a standard RD model.

In our case, this method makes it possible to identify 23 schools that were likely significantly oversubscribed in 2009, and 26 in 2010 (out of 52). For each oversubscribed school j , it is possible to define the sub-sample Sj of students who are not low-income, who come from a public middle school located in the same district as j and whose 9thgrade

scores are closer to the minimum admission score of j (denoted q∗j) than to any other

minimum admission score in the district. This sub-sample Sj covers the set of students

who are either just above or just below the minimum required score for admission into j ,

10As mentioned above, low-income students and students from private middle schools are processed

but for no other school. For each student i in Sj, we can also define her percentile rank distance Di to the cut-off admission score of j , where Di > 0 corresponds to students above the cut-off and Di < 0 to students below the cut-off11.

In the remainder of the article, we develop a regression discontinuity analysis using Di as

running variable, and focusing on the students in the pooled sample of all Sj whose

distance Di to the admission cut-off is smaller than 25 centiles12. We also drop from our working sample students whose 9thgrade score falls just between the two quantiles below and above q∗j, namely students whose 9thgrade scores are too close to the cut-off to know for sure whether they are above or below.

Overall, our working sample consists of about 7,500 students whose 9thgrade scores fall close to an admission cut-off, and our basic research question will be whether we observe

discontinuous behavior and performance above and below the Di = 0 cut-off. In Appendix

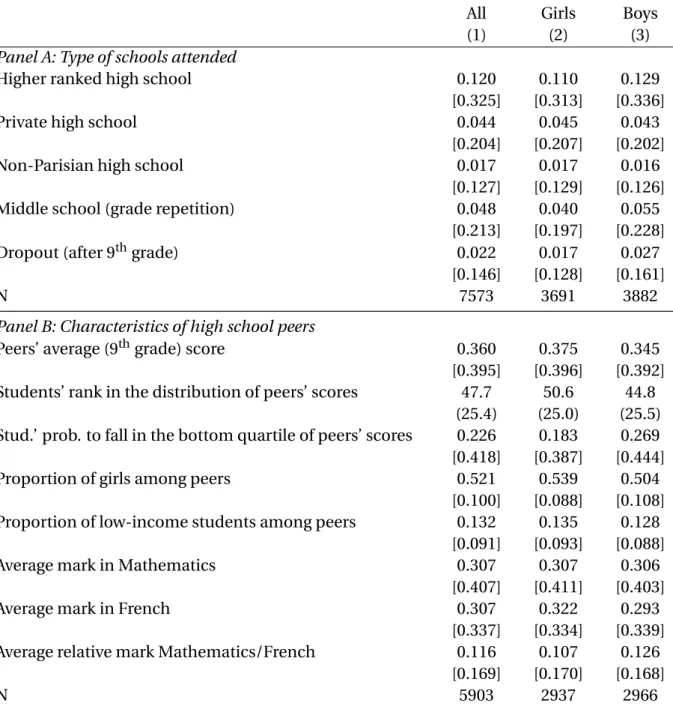

1.A Tables 1.A1-1.A4, we report basic descriptive statistics for students in this pooled sample. In this sample, about 24% of girls choose to specialize in science after 10th grade, against about 38% for boys.

4 Graphical Evidence

Before moving on to a more comprehensive regression analysis, we start by providing graphical evidence on the effect of eligibility for admission into a higher ranked school on three basic outcomes, namely the type of school in which students end up going to after grade 9, their choice of field of study at the end of grade 10 and their performance at the high school exit exam at the end of grade 12. As discussed above, we focus on the pooled sample of students whose 9thgrade score is either just above or just below the minimum ad-mission score of an oversubscribed high school. The basic question is whether we observe discontinuities in enrollment, choice and performance between students above and below the cut-off score. Another important issue is whether we observe similar discontinuities for boys and girls.

11Within each sample S

j, we first define the percentile rank of each student using their 9thgrade score. We

then re-scale this percentile rank variable so that the re-scaled rank is zero for students whose 9thgrade score is equal to the minimum admission score. This running variable is the same as the one used by Abdulkadiro˘glu, Angrist and Pathak (2014).

12We obtain this bandwidth using Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik (2014). As discussed in the next section,

4.1 First-Stage: Effect of Eligibility on Enrollment

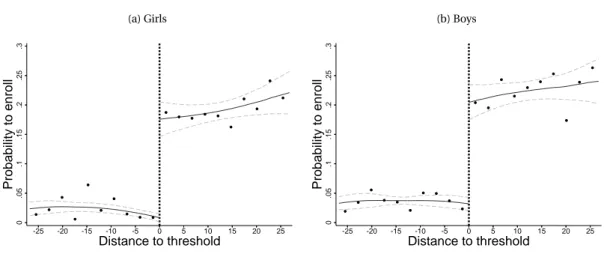

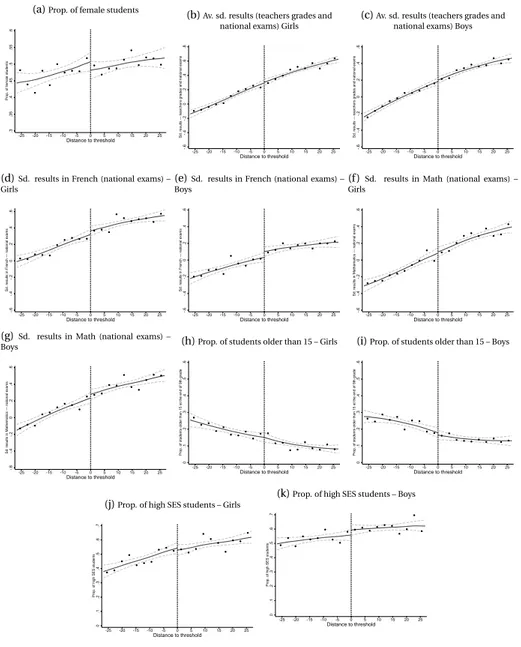

To start with, Figures 1.1a and 1.1b show the probability of enrollment at a higher ranked

high school for students whose 9th grade score is either just above or just below the

minimum admission score13. Figure 1.1a focuses on girls whereas Figure 1.1b focuses on

boys. Comfortingly, they show a very significant shift at the cut-off, the probability of enrollment at a higher ranked high school being about 17 percentage points higher for students just above the cut-off than for students just below the cut-off. This finding is

suggestive that, among students whose 9th grade score falls close to the minimum

admission score of an oversubscribed school, about 17% prefers this school to any lower

ranked school. Results are very similar for girls and boys. It is consistent with the

assumption that girls are no less willing than boys to enroll into selective schools14.

The first potential reason for why enrollment at a higher ranked high school may matter is that it is likely associated with a strong increase in the ability level of high school peers and, consequently, with a strong decline in students’ own ability rank. To provide evidence on this issue, we define for each student her percentile rank in the distribution of 9thgrade scores across her high school peers. Figures 1.2a and 1.2b show the variation in this rank variable for students just above and just below the minimum admission score. On the left hand side of the Figures 1.2a and 1.2b, we observe a smooth increase in students’ rank as their (absolute) score increases and gets closer to the cut-off. On the right hand side, we observe a similar mechanical improvement as we consider students with better scores. But when we compare the first non-eligible students (just below the cut-off ) with the last eligible ones (just above), we observe a significant downward shift of about -6 percentile ranks. Con-sistent with Figures 1.1a and 1.1b, the shift is similar for boys and girls. Figures 1.3a and 1.3b further explore the nature of the change in peer competition at the cut-off. We considered marks in Mathematics and French (using results at end-of-middle school national exams, externally set and marked) and we divided students’ marks in Mathematics by their marks in French, so as to construct (after standardization) a measure of students’ relative ability in Mathematics. The Figures plot the average of this Mathematics/French ratio across high school peers, above and below the cut-off. They reveal a significant upward shift in peers’

rel-13For each Figure, the solid line shows smoothed values of a kernel-weighted local polynomial regression of

the dependent variable on the standardized distance to the threshold. We use a triangular kernel and a degree 1 polynomial smoothing. Smoothed values are estimated separately on each side of the cut-offs. Plotted points represent the mean of the dependent variable for all applicants in a one-unit binwidth. The bandwidth is computed following Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik (2014).

14It should be noted that enrollment rates are not exactly equal to zero for students to the left of the cut-off in

Figure 1.1. This fact reflects that some schools are allowed to develop programs that are focused on a specific theme (sports, music, arts...) and that applications to these specific programs are processed directly by school, not by the centralized system.

ative ability in Mathematics at the cut-off, for both male and female students. We checked that these results are very similar when we use marks given by 9thgrade teachers to construct our Mathematics/French ratio. These findings likely reflect that the willingness to attend a higher ranked school is stronger among students who are relatively stronger in Mathematics. More importantly, these results show that enrollment at a higher ranked school is associated with an increase in peer competition which is even stronger in science than in humanities.

4.2 Field of Study at the End of 10

thGrade

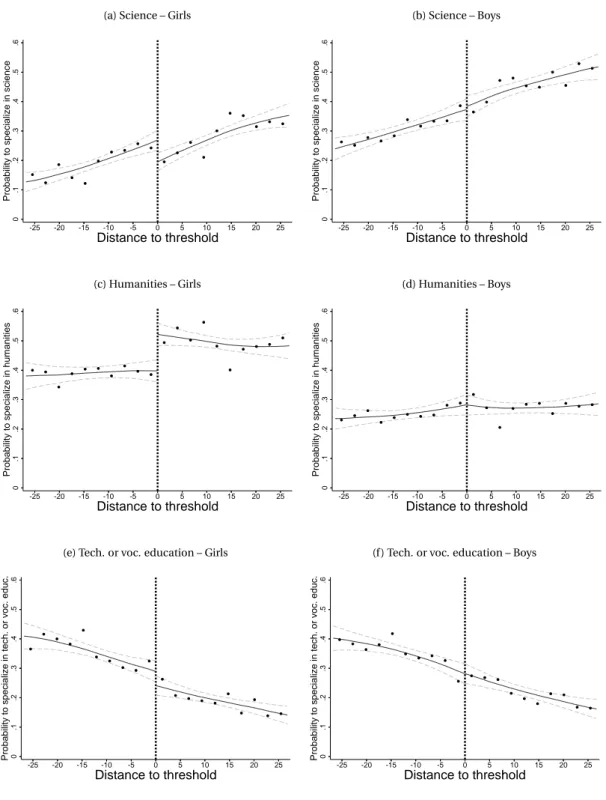

Enrollment in a higher ranked school is associated with an increase in the level of peer competition and the next basic question is whether it affects students’ subsequent choices and performance. Figures 1.4a and 1.4b show the probability of choosing science as a major field of study at the end of 10th grade for students just above and just below the minimum

admission score. Similarly, Figures 1.4c and 1.4d show the probability of choosing

humanities as a major field of study, namely the probability to choose either social sciences or languages and literature. Finally, Figures 1.4e and 1.4f show the probability of opting for technical or vocational education at the end of 10th grade. Taken together, these Figures reveal that eligibility for admission into a higher ranked school induces a significant fraction of girls to choose humanities rather than science as a major field of study. We observe a significant rise in the proportion of girls who choose humanities15, a significant decline in the proportion who choose science as well as a marginal decline in the proportion who opt for technical or vocational education. By contrast, we do not observe any significant shifts for boys.

Figure 1.5a further shows that the negative shift in the probability that female students choose science at the end of 10th grade is followed by a shift of similar magnitude in the probability that they graduate in science at the end of 12th grade. Similarly, Figure 1.5c shows that the positive shift in the probability that girls choose humanities at the end of 10thgrade is followed by a parallel shift in the probability that they graduate in humanities at the end of 12thgrade. Taken together, Figures 1.5a and 1.5c are suggestive that girls who are induced by competition to turn away from science actually succeed in graduating in

humanities at the end of 12th grade, but would also have succeeded in graduating in

science, had they been assigned to a less competitive school. Finally, consistent with Figures 1.4b and 1.4d, Figures 1.5b and 1.5d show no shift in the probability that boys graduate in humanities and no shift in the probability that they graduate in science. Hence, enrollment at a more selective school has no effect neither on boys’ choice of field of study

15There is an increase in both the proportion of girls who specialize in social sciences and the proportion

at the end of grade 10 nor on their performance at end-of-high school exams.

Overall, enrollment at a higher ranked school does not seem to affect students’ graduation probability, only the field in which girls choose to graduate. The fact that we find similar reduced form effects on the field of study chosen by boys and girls at the end of 10th grade as on the field in which they graduate at the end of 12thgrade is also consistent with the fact that very few students change fields after grade 10.

Before moving on to our regression analysis, it should be emphasized that our figures rep-resent the effects of eligibility for enrollment (reduced form effects), not the effects of enroll-ment (local average treatenroll-ment effects). Given that we find that about 17% of eligible students actually enroll in the higher ranked school at the cut-off (the compliers), enrollment effects on compliers are likely about 6 times larger than eligibility effects (where 6 ≈ 0.171 ). For ex-ample, under the maintained assumption that eligibility matters only insofar as it affects en-rollment, a -6 percentage point effect of eligibility on the probability to graduate in science can be interpreted as a -36 percentage point effect of enrollment on the same probability for the 17% of students whose assignment is actually affected by eligibility at the cut-off.

5 Regression Results

The previous graphical analysis focused on the most basic high school outcomes: students’ ability rank, main field of study, and performance on exit exams. To complement and test the robustness of these graphical findings, this section provides a regression analysis of the effect of eligibility for admission into a higher ranked school on a more comprehensive set of outcomes, using a large set of control variables and a standard regression discontinuity model (Lee and Lemieux, 2010). We keep on using the same pooled sample of students as in the previous section, namely the pooled sample of students whose 9thgrade score is ei-ther just above or just below the minimum score required for admission into a higher ranked school. For each student in this sample, we still denote Di the percentile rank difference between the 9thgrade score of student i and the minimum admission score to which she is close. Variable Di is positive if student i is just eligible for admission into the higher ranked school to which her score is close to, and Di is negative if student i is not eligible for ad-mission into this higher ranked school. For each outcome Yi available in our longitudinal database, we estimate the following model:

where variable Xi is a set of control variables which includes controls for students’ age, gen-der, family background, average marks in grade 9 as well as a full set of dummies indicating the high school that corresponds to the nearest cut-off. Function f¡Di¢ is a first order spline function of Di, and we use a tent-shaped edge kernel centered around the admission cut-offs16. Variable ui represents the unobserved determinants of students’ choices and

perfor-mance in high school. The parameter of interest isα. Under the maintained assumption

that there is no discontinuity in the distribution of unobserved ui at the cut-off, this pa-rameter can be interpreted as the causal effect of eligibility for admission in a higher ranked school on the outcome under consideration. Tables 1.A2 to 1.A4 in Appendix 1.A provide the means and standard deviations of the different set of outcomes used in this regression anal-ysis. In the same appendix, Table 1.A5 reports the results of regressing the different observed baseline characteristics (gender, age, family background and average marks in grade 9) on a dummy indicating eligibility for admission into a higher ranked school (that is,1{Di ≥ 0}) using Model (1.1). Consistent with our identifying assumption, we do not find evidence of any discontinuous variation in baseline characteristics at the eligibility cut-off, that is, the "effect" of1{Di≥ 0} on baseline characteristics is never statistically significant at standard level. Also, when we regress the eligibility dummy1{Di≥ 0} on the full set of baseline vari-ables, an F-test does not reject the null assumption that the coefficients are jointly equal to zero. Figures 1.A1a-1.A1k in Appendix 1.A provide additional graphical evidence on the smoothness of baseline characteristics in the neighborhood of admission cut-offs. Finally, as a last specification test, we build on McCrary (2008) to test for manipulation of the run-ning variable around the cut-off. The test does not show any significant difference in the (log) height at the cut-off and does not reject the null assumption of continuous distribution of the running variable at standard level (p-value = 0.75). The result holds true for both male and female samples.

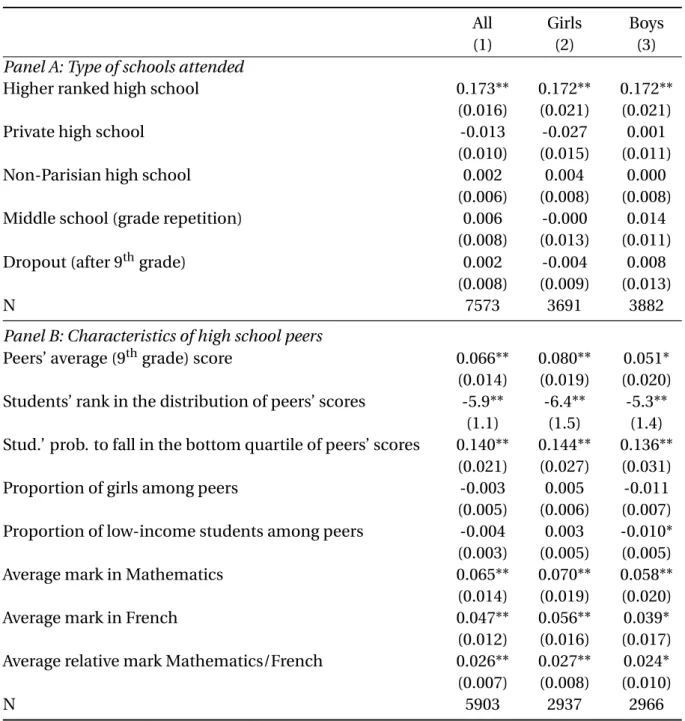

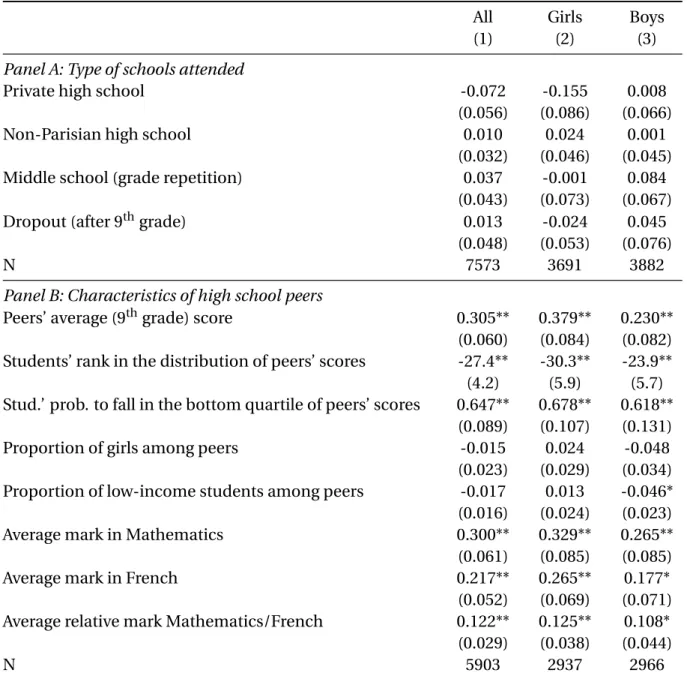

5.1 First Stage Effects on School Environment

The first panel of Table 1.1 shows the estimated effects of eligibility for enrollment into a higher ranked Parisian public school at the end of middle school (grade 9) on the type of

school attended during the following academic year. It shows that eligibility has no

significant effect on the probability that students repeat 9th grade, nor on the probability that they drop out from education. Put differently, there is no evidence that middle school students who fail to be eligible in their preferred high school had rather repeating 9thgrade (or dropping out from education) than going into another high school. The Table also

16This specification is similar to the non parametric specification used by Abdulkadiro˘glu, Angrist and Pathak

(2014). In Subsection 5.3, we check that our results are robust to using higher order spline functions with a uniform kernel.