© The Author 2014. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Business History Conference. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com

Asian Trading Ports and Textile

Branding, 1840–1920

AndreAs P. ZAngger

This article is a contribution to the prehistory of modern branding, presenting a case study of the textile trade in colonial Southeast Asia. The visual appearance of brands as well as their social meaning were altered in the cultural encounter of colonial trade. Through these encounters, trademarks were modernized: the reputation of a pro-ducer became less important than the distinctiveness of the product. When doing research at the business archives of former weaving mills or textile trading houses the historian sometimes encounters some-thing called a ticket book. It seems an odd object amidst the sober let-ters and accounts. These tickets—paper prints the size of a postcard or smaller—are very colorful, displaying an exotic motive, often an Asian scene. They were used in the packaging of cotton piece goods for overseas markets and many of them were registered as trademarks that have largely been forgotten. nowadays, these designs are used to add color to company histories and can also be seen in museums. They have even become collectable items. But their decorative value aside, these tickets have analytical value.

This article discusses the trade in european textiles in Asia and role of the tickets therein. They are shown to be a missing link in the genealogy of modern branding, not in a reductionist manner, but rather as one source amongst others that influenced the development

doi:10.1093/es/khu050

Advance Access publication september 30, 2014

Andreas Zangger is a historian in Amsterdam and Alumnus of the UrPP Asia and europe in Zürich, switzerland. Contact: UrPP Asia and europe, Wiesenstrasse 8, 8008 Zurich, switzerland. e-mail: andreas.zangger2@uzh.ch. I would like to thank darrin Hindsill for his comments and for editing. I would also like to thank the diethelm Keller Holding and the various pub-lic institutions in switzerland and the netherlands for granting me access to their archives. I would like to thank Adrian Wilson for his collection of ticket books online. Finally, I would like to thank erich Keller, Cristoph dejung and

of branding. The article argues for the importance of having a more global outlook in a field that has traditionally been centered on Western accounts. It also makes a case for the textile industry’s con-tributions, a sector that is often ignored in accounts of branding, even though it was a pioneer in global trade. Finally the article stresses the role of trade in early branding, especially that of transnational trade.

I

Before addressing these issues we will examine the relevant litera-ture for possible interpretations of the shipper’s tickets. Brands had a long history with many shifts in their meaning, from the marks of the Cutler Company in the seventeenth century to the polysemic tools of (post-)modern consumers for realizing their individual or collec-tive identity-projects.1 But while historic interest in branding is only recent, it has been taken up by several disciplines: economic and legal history, business history and economic anthropology. each field gives different answers to the questions as to what trademarks are, and where and when they originated.

The dominant account of the rise of the brand

In most historic research trademarks are associated with the modern multinational corporation and its rise in the period between 1880 and 1920. Paul duguid has critically noted that this connection has almost become true by definition.2 economic historians think of the develop-ment of intellectual property rights and the legal jurisdiction accom-panying it as a prerequisite for the rise of capitalist society.3 In her seminal article on trademarks Myra Wilkins calls them “an intangible asset” of the modern multinational, Chandlerian corporation.4 Wilkins argues that the modern multinational would not be able to realize the “scale and scope”5 of production and distribution had they no unique name with which to attract buyers. According to Wilkins, the main difference between trademarks and earlier forms of marking is that the artisan marks were seen as a liability, while in the late nineteenth century trademarks were increasingly seen as an asset of a company.

Undoubtedly multinational companies played an important part in the development of branding and other marketing instruments, most of which were developed in the era between 1850 and 1930.6

1. Holt, Why do brands cause trouble? 2. duguid, developing the brand, 406.

3. north, structure and change in economic history. 4. Wilkins, neglected Intangible Asset.

5. Chandler et al., scale and scope the dynamics of industrial capitalism. 6. see Fullerton, How Modern Is Modern Marketing? or for an overview over different theoretical and temporal frameworks Church, new Perspectives.

However, reducing trademark history to the development of the Chandlerian corporation has been challenged from different angles. The reduction of the trademark’s development to a producer’s per-spective and a certain type and size of firm, to the late nineteenth century as well as to Western countries has been criticized.

Modern branding is older than thought

recent anthropological studies trace the history of marks in trade all the way back to ancient Mesopotamia. These studies have adopted a perspective that focuses on consumption more than production. They also focus on the brand as both sign and material object.7 david Wengrow criticizes the traditional identification of branding practice with late capitalism, and instead portrays branding as an answer to problems of economies of scale under a wide range of institutional and ideological conditions.8 He connects the marking of products to practices of sealing that originate in personal seals. These seals are used as guaranty of homogeneous quality. Anthropologist Frank Fanselow presents a similar argument in his account of the contem-porary bazaar economy in Tamil nadu9: the trade in non-substitutable products is based on personal trust between buyer and seller, with sellers constantly under the suspicion of cheating and manipulating. substitutable products, in contrast, are based on standardized quan-tity and quality. But in order to link consumers to producers, and to hinder deception by sellers, these products must be sealed and marked.

scholars of Chinese history have pointed out the long history of branding in the country. The first known complete brand in the mod-ern sense was used in China during the song dynasty (960–1127). A needle manufacturer used a white rabbit as a symbol to help the illiterate to identify his shop. The image of a rabbit was used as a sign for the shop as well as on the packaging of the needles. Furthermore the rabbit carried the symbolic meaning of feminine power, something that resonated with the clientele targeted.10 Based on their investi-gation of the Chinese practice of branding in the time of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), Hamilton and Lai argue that branding should not be viewed as a unique feature of Western capitalist societies.11 They have shown that in the early Qing dynasty much of Chinese long-distance trade was commoditized and that brands played a major role in consumer choice.

7. Bevan and Wengrow, Cultures of commodity branding; Wengrow, Prehistories of Commodity Branding.

8. Wengrow, Prehistories of Commodity Branding. 9. Fanselow, Bazaar economy.

10. eckhardt et al., A Brief History of Branding in China. 11. Hamilton et al., Consumerism Without Capitalism.

In the history of Western business there also have been various studies that found branding practices to have existed long before the rise of the modern multinational. de Munck argues that early-modern artisan marks in Flanders were used to transport product image.12 He suggests, similar to Hamilton/Lai, looking beyond production and to the embedding of a brand in a certain relation between producer, trader and consumer.13

These recent studies in economic anthropology show that brand-ing is a much older and more widespread phenomenon than it is often portrayed as in business history. They also draw our attention to the brand as physical object and to the importance of sealing practices.

However, the question remains as to when and where the transi-tion from the pre-modern to the modern version happened, what this transition comprises and what the driving forces were behind this development. Paul duguid suggests that research on this transition should focus on the “relatively unexplored gap between Wedgwood and Heinz,” the period between 1800 and 1880.14

What is a brand?

In order to study the transition from the pre-modern to the mod-ern brand we first have to define and comprehend the object. some economic historians see the difference between ancient and mod-ern forms of branding in the quality of information a mark carries. According to de Munck the “distinction may be related to a shift away from marks that convey information on the origin of a product or the status of a producer in the context of a ‘stratified state’ towards a situation in which trade marks and brands are instruments in the hands of autonomous firms.”15 Brands carrying information regarding origin and quality, representation of status, power, or value, can be found in many societies, but the construction of product image and something described as brand personality is a unique feature of the modern brand.16

According to legal scholar Frank schechter, trademark law in the nineteenth century still viewed the mark as something connected to the liability of the producer. This notion grew out of the practice around the early-modern marks of cutlers or weavers, which allowed the tracing of a product back to its producer and holding him liable in case of damage. schechter cites a judge who compared trademarks

12. de Munck, The agency of branding and the location of value. 13. Ibid; Hamilton et al., Consumerism Without Capitalism. 14. duguid, developing the brand.

15. de Munck, The agency of branding and the location of value, 1055; Hamilton et al., Consumerism Without Capitalism.

to the brand marks on cattle that allow the identifying of the owner or source.17 But, this metaphor of cattle branding is based on a mis-conception of the function of the trademark. According to schechter “the mark actually sells the product.”18 He sees the slowly emerging comprehension of this fact in the legal praxis as an important step for trademark law.

To get a better understanding of this transition, the semiotic analy-sis of the trademark/brand brought forward by Barton Beebe is help-ful.19 He follows the triadic conception of the sign by de saussure, and makes a distinction between the signifier (the perceptible form of the sign), the referent (the tangible product), and the signified (the meaning to which the perceptible form refers). The ticket or trade-mark stands for the signifier: it tells the consumer that a certain piece of cloth (referent) comes from a certain source (signified) and that he can expect a consistency of quality of the product. The brand itself would stand for the overall relational system of the sign.20 This distinction illustrates the various relations in the sign system of the brand, such as the relation between mark and product or mark and source. schechter would then describe a shift: the mark that once identified the producer now identifies the product.

In branding an important innovation was the drawing up of prod-uct lines in place of producer branding. so-called “fancy words” for products became more and more popular after legislation accepted their registration as trademarks. John Mercer sees brand names as an important contribution to a shift in the nature of branding. “Its adop-tion marked the development from marks as descripadop-tions of origin to brands as items of artifice, from conveyors of information to evoca-tive contrivances.”21 This finding goes hand in hand with those of schechter.

If we accept this view of a shift in the nature of the brand from a mark indicating a real source to an artificial item carrying an array of meanings, the focus is placed on ways of communicating with customers.

Old and new industries and the role of trade

Historians of pre-modern and modern brands usually look at dif-ferent industries. david Higgins contends that business historians researching modern branding have paid more attention to “fashiona-ble” industries like beverages and processed foods, whose trademarks

17. schechter, The historical foundations of the law relating to trade-marks, 147. 18. schechter, The rational basis of trademark protection, 819.

19. Beebe, The semiotic Analysis of Trademark Law. 20. see especially Ibid; 47.

developed into successful brands, while neglecting the “unfashion-able” industries like textiles and cutlery.22 This difference, however, can be explained substantially and is not just a matter of fashion: Consumers tend to comparison shop for search goods (clothing, fur-niture), while with non-durable or durable experience goods (food, drink, toiletries, pharmaceuticals/books, watches, paints) measuring costs are high, and it is often easiest just to buy and try out the prod-uct. This difference explains different marketing strategies adopted.23 nevertheless, in the global intermediary trade in cottons, the use of trademarks was already widespread in the early age of branding, as this article will show. In the period before the vertically integrated firm, attention should be given to supply chains trying to reach distant markets. Paul duguid, in his study of the alcohol trade in nineteenth century england argues that brands were rarely used as an asset of a producer to fight competitors. He instead sees them as a way of disci-plining the links in a supply chain of small firms.24

This article is a contribution to the pre-history of modern brand-ing, focusing specifically on the trade in european ginghams and calico prints in southeast Asia. I will show the development of a specific kind of branding and what effects it had on the supply chain. In opposition to the traditional account of branding, which has mainly been told from the producer’s perspective, this account brings into the picture the various actors that were involved in the establishing of the brands: european merchants in singapore, Batavia, Manchester and rotterdam; Chinese and other Asian trad-ers in singapore, the dutch east Indies; productrad-ers in Britain, the netherlands and switzerland; lithographic printers in Manchester, as well as courts in singapore and London. The research is based on the business archives of dutch, german and swiss textile pro-ducers and traders, on personal letters of european merchants in Asia as well as judicial records of trademark cases in the UK and singapore. Unfortunately, the impact of Asian consumers is impos-sible to assess, as sources yield little information about the influence of textile brands at consumer level. However, the sources do give a multifaceted picture of the wholesale trade of european textiles con-ducted between european merchants and Asian retailers who sold the goods in the Malay Archipelago.25

22. Higgins, Forgotten heroes, 282. 23. Church, new Perspectives, 414f. 24. duguid, developing the brand.

25. The business archives visited comprise: diethelm & Co (dA); rautenberg, schmidt & Co (singapore and Penang) (rs). Textile producers: Koninklijke stoomweverij nijverdal (KsW); gelderman & Zonen (gZ) (Mathias naef, niederuzwil (Mn), Birnstiel, Lanz & Co (BL), P. Blumer & Jenny (BJ).

II

In the nineteenth century trade between europe and southeast Asia was concentrated in the bazaars of a few cities like Batavia, singapore, Penang, Makassar, Bangkok, saigon, and Manila. europeans were able to profit from a well functioning retail trade network in the archi-pelago that grew in tandem with colonial expansion, and limit their trade activity to wholesale.26 Agricultural products of the archipelago were brought to the trading ports and sold as staple goods. during the early colonial period these products, especially spices, dominated the transcontinental trade between europe and southeast Asia. But in the course of the nineteenth century, with the growing importance of industrial production, trade in the other direction—manufactured goods exported from europe—became equally significant.27 This bidi-rectional trade allowed for optimal use of cargo capacities in inter-continental shipping and reduced the need for complicated money transactions as proceeds from selling goods could be directly used to buy other goods. The competition on the market for european textiles in southeast Asia grew as the rivalry between industrialized coun-tries in the era of imperialism increased.

Textiles became the most important imported good. While the mar-ket in bulk produced uncolored cottons, so called “greys,” was firmly in British hands28, the market in colored cotton piece goods was more contested. This was true especially in the sale of high-end manufac-tures like calico prints and ginghams (colored woven cottons), where the quality of colors and patterns played a crucial role. Here, produc-ers from scotland, saxony, eastern switzerland, Vosges, Alsace, and the netherlands competed intensely. This market was determined less by price than by product differentiation.29

The merchants of these colored cottons faced thus two fundamen-tal problems. The product had to be constantly changed, in order to respond to demands of fashion and be distinct from the competition. But at the same time it had to communicate consistency of quality in order to get returning customers. This requirement of both unique-ness and consistency has been typical of the apparel industry for a long time. Creating steady international demand for specific types

26. ray, rise of the bazaar.

27. For the foreign trade of singapore up to WWI see Chiang Hai ding, History of straits’ settlements foreign trade; Wong Lin Ken, The trade of singapore, 1819–1869.

28. For trade figures in the dutch Indies see Lindblad, de Handel tussen nederland en nederlands-Indie, 1874–1939.

29. For monopolistic competition in the market for finished cloth see Brown, Imperfect Competition and Anglo-german Trade rivalry: Markets for Cotton Textiles before 1914.

of cloth required strenuous efforts to ensure uniformity. It has also “meant conveying knowledge of their identities and qualities to geo-graphically separated populations, and, in the past, this has often been without the benefits of mass literacy, advertising, or global mass media.”30

In the long-distance textile trade, well before the advent of trade-mark registration, trade-markings played a crucial role. There is a tradition of textile marks going back to the medieval era. In cities exporting textiles, producers were obliged to put their mark on their goods. For that they often used so-called selvedge patterns or line-headings, i.e., marks woven into the top or bottom of a fabric designating qual-ity and origin.31 This was a measure designed by the authorities to prevent fraud, and it can be found in europe as well as in China.32 The selvedge patterns allowed the tracing back of a woven good to the producer, holding him liable, either by legal or economic meas-ures. But they were also a guarantee that the cloth was not cut by the intermediaries. By the early seventeenth century, Chinese cotton producers used these patterns to send advertising messages to the consumers.33 Today these selvedge patterns are still used in the trade of dutch wax prints in Africa.34

Industrial producers also used stamps on bolts to mark the end of the fabric, hence the name bolt stamp. One of the early european examples of a stamp for textiles exported overseas is that of VOC, the dutch east Indian Company. With the onset of industrial production and the multiplication of producers and traders, identification of an item’s origin became a problem. Most products were marked with a combination of stamps indicating producer, trader and quality. In a booklet from around 1920 a dutch producer lists 1,176 combinations of stamps, for the targeting of different markets.35 This number may have been even higher for Manchester producers.

While the stamps were mostly used on whites and greys, because of visibility, printed labels were provided for the more elaborate colored weavings and prints. The so-called “shipper’s tickets” or “bolt labels” were printed labels that were placed on bolts, boxes, or envelopes

30. Clark, “Lincoln green and real dutch java prints,” in Cultures of commod-ity branding, ed. Bevan, 197.

31. Meyer, entwicklung der Handelsmarke in der schweiz; Higgins et al., The trade mark question and the Lancashire cotton textile industry. The Linen Act of 1726 officialized these headings in england and gave producers some protection against counterfeiting. Bently, Making of Modern Trade Marks Law, 5.

32. eckhardt et al., A Brief History of Branding in China. 33. Hamilton et al., Consumerism Without Capitalism, 260f.

34. Clark, “Lincoln green and real dutch java prints,” in Cultures of commod-ity branding, ed. Bevan and Wengrow.

as an eye catcher. The earliest examples date from as early as 1680: textiles exported to West Africa by the royal Africa Company were wrapped in a stiff paper with a picture of a “gaudy elephant.”36

Between 1830 and 1870 these tickets became a permanent feature of the european textile trade overseas. They can be found on all con-tinents in trade with people who were not expected to read european writing. Once trademark registration was introduced in Britain in 1876, producers and quickly began to submit them for registration.37 By the end of the 1870s more than 44,000 marks for textiles were caught up in a backlog of registrations! Cotton piece goods were the class with the greatest number of requests for protection, although many marks did not meet the criteria of being the sole property of the applicant, because they had become “common to the trade.”38

One specific trait of these shipper’s tickets is their visual language, which mostly consists of symbols. This symbolic language is typical of the transcontinental textile trade, although it can also be found on other products, as well as textiles for the european or American mar-kets. But for the most part, branding practices in european domestic markets at the time were more focused on the name of the producer and thus script based.39

What’s in a name?

In the nineteenth century brand names for products were not very common. Branded products could be found in the health and hygiene sector in the early romantic era, but they had a touch of quackery.40 Barbara McClintock describes “sunlight,” introduced 1884 by the British company Lever Brothers, as the first modern brand insofar as the product was marketed as an entity in itself and less in relation to the producer.41

A common way to promote a product was, however, to use the name of the business owner as a trademark. This choice was rooted in a business practice that firmly linked name and reputation as well as “moral” and monetary credit.42 In an economy transgressing a regional scope, it was crucial for businessmen to get information on the financial situation as well as on “character” or “moral credit” 36. Wadsworth et al., The Cotton Trade and Industrial Lancashire, 1600–1780, 150.

37. den Otter et al., “Twentse tjaps.”

38. Higgins et al., The trade mark question and the Lancashire cotton textile industry. see also Higgins, Forgotten heroes.

39. Mercer, Mark of distinction.

40. strachan, Advertising and satirical culture in the romantic period, 29–34. 41. McClintock, Imperial Leather.

42. For the name as social capital see sunderland, social capital, trust and the industrial revolution, 1780–1880; Olegario, Culture of credit.

of their partners.43 The name of a business stood for the goodwill it had and was considered an asset. At the time, for smaller merchant houses or businesses, reputation was connected more closely to ethi-cal issues and individual conduct than it is for a modern corporation. “We have a good, beautiful name everywhere and I doubt not one moment that it will stay so,”44 said the senior partner of the trading house Hooglandt & Co in singapore to his new junior partner, and his statement can be read as an urge to behave accordingly. For small businesses named after one or more of the partners, the distinction between the public and private aspects of a name, reputation and personal character becomes blurred. On the local level it was nearly impossible to make a distinction between the private and the pub-lic behavior of a businessman. In global trade, however, this kind of social control was difficult to maintain.45

One solution to this problem manifested itself in an early use of trade-marks. In the nineteenth century trademarks were very much indebted to the idea of the reputation of an entrepreneur communicated through his name. “A man’s name is still stronger trade mark than any that can be devised,” a British trademark lawyer observed in his treatise on the subject of 1876.46 Likewise the economic theory of trademarks is also indebted to this tradition of linking brands and reputation.47

Visual communication

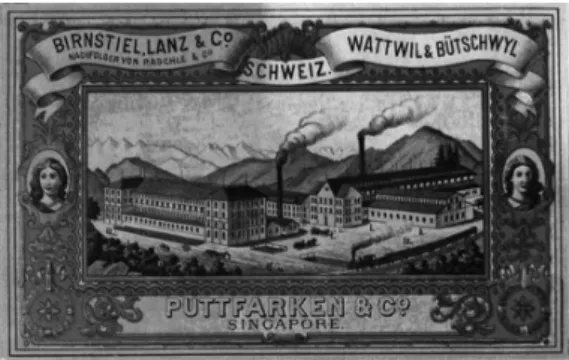

How could professional integrity and standards of quality be com-municated, if consumers used a different writing system and Western names sounded unfamiliar? Many early producers seem to have been in the dark about this issue. A common practice was to use the business name in combination with an illustration of their factory as trademarks (see figures 1–4). An early example comes from the Koninklijke Weefgoederen Fabriek C.T. stork in Hengelo. This sam-ple was found in the business archive of Mathias naef, niederuzwil, one of the main producers of colored weavings in switzerland, who was obviously using the dutch trademark as a template for the design of his own mark in the 1860s. Both the dutch and swiss producers 43. The major swiss producer of calico prints P. Blumer, Jenny & Co kept records of their business partners worldwide in their “information book.” For the professionalization of business information in the Us see Olegario, Culture of credit.

44. Letter of J. r. riedtmann in switzerland to W. H. diethelm in singapore. 16.5.1876. dA, A 2.7.

45. rabo, A shop of one’s own; dahl, Trade, trust, and networks; Aslanian, global Trade networks of Armenian Merchants.

46. salaman, Manual of trade mark registration, 11.

47. For a critical evaluation see Casson et al., export Performance and reputation.

copied predecessors from england. The marks speak to the success and achievements of the entrepreneurs—in line with the idea of the name of the entrepreneur representing the business.

However, it was a badly chosen symbol for use in their chief mar-kets in the Malay Archipelago, as the factory was not a common cul-tural symbol in southeast Asia.

These tickets contrast with the standard ticket that became estab-lished in the textile trade in south and southeast Asia in the years between 1850 and 1890.

There were two forms of the standard ticket: a smaller one in green and gold reserved for yarns, and a bigger one, about the size of a wine label or a postcard used for cotton piece goods.48 As can be seen in

fig-ure 5, it is the glaring colors that first strike the eye.49 Looking at col-lections of these tickets it is above all the consistent use of symbolic signs for identification that stands out. These symbolic trademarks

48. susan, Textile ticket printing and pattern card making. 49. Figures 2–4 originally are also colored.

Figure 1 Mark of the weaving mill C. T. Stork in the netherlands, ca. 1850s (courtesy of Staatsarchiv St. gallen).

Figure 2 Mark of the weaving mill Mathias naef in Switzerland, ca. 1860 (courtesy of Staatsarchiv St. gallen).

are typical of the textile trade with Asia. In order to understand the development of these tickets we have to look both at lithographic printing and its use in trade, as well as at the trade between europeans and Asians in the Asian emporia.

Shipper’s tickets in the world of ephemera

In the first half of the nineteenth century the printing business wit-nessed a series of innovations such as lithography and chromo-lithography. These innovations made the use of color for advertising purposes affordable for a broad range of businesses.50 subsequently printers and businesses began to experiment with more sophisticated material for communicating to with customers. The tickets are just one item in the variety of ephemera like trade cards, postcards, greet-ing cards, brochures, posters, wrappers etc.51 The Liebig cards—first issued in 1875—are a prominent example.

50. Last, The color explosion nineteenth-century American lithography. 51. For package printing see davis, Package and print. For ephemera in general see rickards et al., The encyclopedia of ephemera.

Figure 3 Mark of the weaving mill Birnstiel, Lanz & Co in Switzerland, ca. 1890 (courtesy of Toggenburgermuseum).

Figure 4 Mark of the weaving mill H.P. gelderman & Zonen in the netherlands, ca. 1920s (courtesy of Historisch Centrum Overijssel).

The shipper’s tickets as well as the Liebig card originate from so-called advertising trade cards that producers and retailers in europe and America used to promote their businesses and products.52 These trade card’s history goes back to the seventeenth century. They were initially little more than a sophisticated business card. eventually, however, the entire spectrum of commercial printed graphics, from stationary over labels to price lists, evolved from these early mod-ern trade cards.53 In the last quarter of the nineteenth century with the advances in printing techniques and the possibility of using colored pictures, they became a widespread tool of marketing. They were also popular with the public and even became a collectable item, as the use of color was a novelty for contemporary printing. The similarities of commercial collecting cards with the shipper’s tickets are striking: they were both based on the same printing tech-nique and developed in the same period; they are about of the same size; they both play with color and both are dominated by an image. sometimes it is hard to tell the difference between a trade card that is used as an advertisement to evoke certain emotions and the trade-mark used to identify a producer or a product. The collections of the printers include tickets used to denote length and quality of the cloth—mainly destined for southern european and south American markets. They were often adorned with an illustration of a glamor-ous woman or a child, either of which would have been difficult to register as a trademark. Printers also produced so-called stock cards—cards with a special motif printed in color—that could be used either as trade card or trademark.

52. Kaduck, Advertising Trade Cards; greene, Advertising trade cards. 53. rickards et al., The encyclopedia of ephemera, 334.

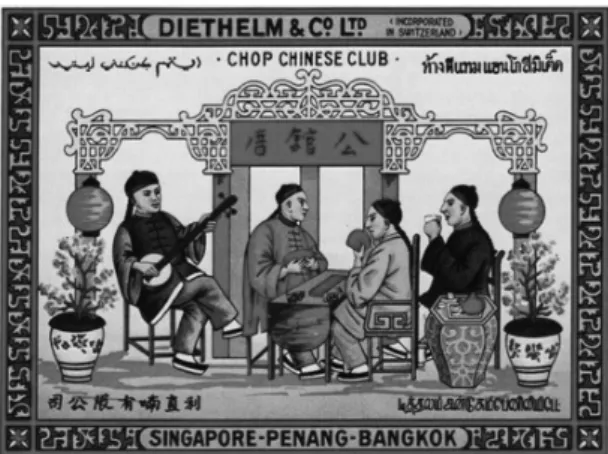

Figure 5 One of the trademarks of the trading house Diethelm & Co in Singapore (courtesy of Diethelm Keller Holding).

But despite the many similarities between the two, the image has a different function: the image on the trade cards is mostly illustrative. There are, roughly speaking, three kinds of images in the vast array of designs: those showing the product of the company; those presenting an allegory of the qualities of the product, and those with no obvi-ous connection between product, such as the image on the Liebig cards, where the motifs were chosen for their decorative, exotic or educational value and less as a direct way of promoting the product. The image on the shipper’s tickets for Asian markets, however, is not illustrative of the product, but rather identifies the product by using a symbol.

As the media developed, the difference between the imagery of advertising and the logo as an identifier became sharper. But even today the borders between the two are contested, and courts regularly have to decide whether the wording or imagery of an advertisement can cause confusion with a registered trademark.54 In the last quarter of the nineteenth century this border was more diffuse.

Arbitrary symbols, Asian or not

In europe there is long tradition of using pictures in trademarks. The signs of the inns in the early modern era created for a predominantly illiterate clientele are an example.55 The tobacco trade used images of slaves or native Americans on the packages as early as 1700. Trademark design for alcoholic beverages or medicines also used such symbolic signs.56 In fact, for British trademark law a trademark, if not the name of a business owner, was usually a symbol or emblem.57

Often these pictures had an illustrative character. A typical more modern example is singer, whose logo—a sewing machine—being generic could not have been registered without the additional com-pany name. Think of the Peircean distinction between icon (likeness between sign and object), index (factual connection between sign and object) and symbol (arbitrary relation between sign and object).58 All three types of signs can be found in trademarks, although the icon can only take an illustrative role, as explained in the example of singer. The factory marks are an example of an indexical sign, but they can’t stand on their own either and need the company name 54. e.g., Citrus group Inc. v. Cadbury Beverages, Inc., 781 F. supp. 386 (1991). 55. Maczak et al., Travel in early modern europe. Chap. 1.

56. see davis, Package and print the development of container and label design, 92–97; Lewis, Printed ephemera the changing uses of type and letterforms in english and American printing.

57. Bently, Making of Modern Trade Marks Law.

58. Peirce, new elements. For the difference in branding between symbolical and iconic/indexical signs see also Lury, Brands, 78–85.

for specificity. This does not imply that indexical marks cannot be distinctive. nevertheless, once established with consumers, symbolic signs can make for stronger brands, because the sign speaks to the consumer. The arbitrary connection between sign and product, pro-viding the sign is not already in use in the industry, makes symbolic signs distinctive.59

But neither the precursors nor the intrinsic reasons favoring arbi-trary signs can sufficiently explain the success of arbiarbi-trary symbols as trademarks in the Asian textile trade. The shipper’s tickets for Asian markets stand out in collections of commercial graphics. It is not only the exotic imagery, but the invariable use of arbitrary symbols that attract attention. Only matchbox design is similar in its consistent use of symbols. It also evolved from using names and factory pic-tures to creating brands using symbols in the period between 1850 and 1880.60 Matchboxes were an interesting field for testing effects of branding, because there was hardly any difference in quality with which to differentiate the product. Interestingly the same merchants who were selling textiles in southeast Asia were also involved in the selling of matches.

It remains a legitimate question to ask, why the textile merchants so consistently chose for arbitrary symbols to sell their goods and how they came up with their libraries of symbols. Merchants generally lacked experience in design, just as the printers lacked experience in marketing. The case of a swiss-dutch trading house in singapore shows them experimenting with various motifs (see below) and even flirting with the idea of counterfeiting.

Only towards the end of the nineteenth century were there spe-cialized printers for shipper’s tickets such as norbury, snow & Co or Benjamin Taylor & Co in Manchester. The latter advertised themselves as “Textile Trade Mark Printers for India, China, Burma, s. America, egypt and the near east. Java, sumatra and the straits. Africa, Japan and the Colonies.”61 According to the books of the company the vast majority of the tickets were destined for Asian markets. For their design the firm had up to twenty lithographic artists on their payroll, as the tickets needed to be complex enough in order to prevent coun-terfeiting. some of the designs were developed in-house and directly registered as trademarks, which a firm could then buy.

But shipper’s tickets must be seen as something more than just a special development in design. They were embedded in a daily prac-tice of the bazaars in the major Asian emporia. We therefore have to

59. On distinctiveness see Beebe, The semiotic account of trademark doctrine and trademark culture.

60. Jones, Matchbox Cover design.

turn to their social function, which was affected by local culture in the trading ports.

Eastern tradition of seals and stamps

seals and stamps authorizing or legitimizing documents or products are firmly rooted in the culture of east Asia and southeast Asia. In the Malay world the seals are engravings in Arabic script that symbol-ize royal authority and were being used throughout the archipelago when the first europeans arrived in the region.62 The Malay word for the seals is “cap” or “tjap” in the dutch transcription. In english it is usually referred to by “chop.” The expression “chop” carries the his-tory of cultural encounter and hybrid developments in the colonial Indies. Its origins are disputed: it may have come from the Hindi word “chhap” meaning stamp, seal or something coined.63 Another theory claims that it came from the Chinese expression “tsah,” which is pro-nounced as “tsap” in Cantonese, which means a contract or a written order from a superior.64 The expression was then picked up in Malay, the lingua franca used in trade throughout southeast Asia. Here it was used to mean “stamp,” but more generally for something author-ized or legitimauthor-ized by a stamp like passports or trade licenses. This meaning of the word also found its way into Portuguese, english, and dutch. Ultimately the expression “chop” denoted Western trademarks in the material form of bolt stamps and shipper’s tickets. Trademarks are thus placed in a tradition of signs of legitimacy.

In the Cantonese trade the expression was omnipresent. The “Chinese Commercial guide” of 1856, a book by samuel Wells Williams, an American linguist and diplomat, mentions “chop” in several contexts. The “grand chop” was the customs clearance; the “chopped dollar” was a punched coin with a personal seal of a mer-chant. He would only accept payments with his own chop on it. In the tea trade the “chop” designated a certain brand: “The word chop, (hau or tsz’ hau a term of common use in the tea trade,) means merely a brand or mark, and is given by the brokers who make up the lots of tea in the country. It is frequently the name of a firm, or merely a fancy appellation applied to each distinct lot of the same quality and origin, to distinguish it from other lots, even of the same sort of tea. […] The ‘chop name’ consists of two characters, as yuh-lán (Magnolia), hing 62. gallop, Malay seal inscriptions: a study in Islamic epigraphy from southeast Asia.

63. Hobson-Jobson (1903): A glossary of colloquial Anglo-Indian words, article “Chop.”

64. rouffaer et al., de batikkunst in nederlandsch-Indië en haar geschiedenis, 216f.

lung (rising Affluence), fang chi (Fragrant sesamum), &c., and has slight reference to the origin or quality of the tea.”65 similarly the use of chops to denote origin and quality was standard in the trade with raw silk in China and was introduced in Japan by Western merchants after the opening of trade in the 1860s.66

The study of Hamilton and Lai cited above specifically mentions brands in textiles. These textiles, mostly originating from the same region in the Yangtze delta, were also exported to the nanyang (mar-itime southeast Asia), europe and America.67 The straits Times in singapore list nankeens, a coarse, yellowish Chinese fabric for export to the West, as a trade item in the 1830s. Whether these nankeens had their own brands is not reported. If we follow Hamilton and Lai we can assume that by the mid-nineteenth century Chinese traders in southeast Asian trading ports were more or less familiar with branded textiles from China. Other authors are more cautious and suggest that the Qing marketing economy was a relatively closed sys-tem where personal networks of brokers and merchants accessed the marketplace.68 This is more a critique of the power of the brands than their relevance. In the long-distance trade we can assume that the cot-tons exported were branded.

Lessons from markets overseas

Trading in markets overseas was highly risky, especially for the swiss who did not have a long seafaring tradition and could not refer to a navy for protection. For this reason the swiss were highly responsive to market demands and began to do market research prior to pro-duction. “I feel the market’s pulse,” writes Conrad Blumer, one of the major producers of textile prints in europe, when he travelled to India, singapore and Batavia in 1846 to collect patterns and market information.69 The dutch and Belgians studied the swiss model after learning of its success in foreign markets.70

Lessons learned included the importance of extrinsic factors like packaging71 and branding for sales. In eastern markets, especially,

65. Wells Williams, A Chinese commercial guide, 196.

66. Bavier, Japan’s seidenzucht, seidenhandel und seidenindustrie, 71f. 67. Hamilton et al., Consumerism Without Capitalism.

68. Zurndorfer, Cotton Textile Manufacture and Marketing in Late Imperial China and the “great divergence,” 724. referring to rowe, domestic Interregional Trade in eighteenth-century China.

69. stüssi, Conrad Blumers grosse reise, 18.

70. Kindt, notes sur l’industrie et le commerce de la suisse; Waal, Aanteekeningen Over Koloniale Onderwerpen. just to name two of many exam-ples. Also see Brommer, Bontjes voor de tropen, 29. see also simons et al., Berichten over en weer.

brands were regarded an imperative for trade. Interestingly many merchants talk of branding rather as a requirement of their trading partners than something springing from their own initiative. Many representatives of the industry and commerce comment on the fact that Chinese and other Asians “buy by mark.” george Wostenholm, producer of quality blades in sheffield, formulated this requirement in a typically Victorian manner: “Many people who cannot read english buy our goods, Chinese for instance (…) and I have heard say those on the Pacific Coast will not buy a knife unless these strange marks I*XL are on the side of the blade. You will see therefore, when dealing with foreign markets, how important it is to have a very distinctive mark— we must presuppose in the purchaser not only ignorance of quality, dense ignorance even, but also ignorance of the english language.”72 An American consul in Japan writes: “designs and ‘chops’ (trade-marks) in the east have a value annually of many thousands of dollars from the repute in which they stand. Old established concerns can almost bank upon a sale of a certain quantity each year of the goods which they handle.”73 Finally a german merchant who had done extensive trade in Hong Kong writes: “Business was facilitated by the fact, that the Chinese would buy merchandise under a certain chop, which is viewed as a guaranty for consistent quality. This trademark, the so-called chop, is in general a colored image in Chinese taste. [...] Introducing such a trademark was the actual difficulty. Once intro-duced it was easy to make sales, and usually chopped goods got better prices than unmarked ones; it could happen that the same good was highly in demand with a chop, but could not be sold without it.”74

In singapore and Java chops were omnipresent in the textile trade. The varied designs of British, swiss and dutch traders reveal a trial-and-error process in the selection of symbols. We see plants, animals, people, symbolic objects and mythical figures. The trading houses were able to observe the effects of different symbols: some labels sold well, while others—often with the products of the same producers—did not sell.75 The merchants mined familiar symbolic libraries. Besides the 72. george Wostenholm in 1888. Cit. after Higgins et al., Asset or liability?, 6f. 73. department of Commerce and Labor. Monthly Consular and Trade reports. nr. 300. september, 1905.

74. „Im übrigen wurde das geschäft […] dadurch erleichtert, dass die Chinesen daran gewöhnt sind, eine Ware unter einer bestimmten Marke zu kaufen, welche als garantie für gleichbleibende Qualität angesehen wird. […] die schwierigkeit war jeweils, eine solche Marke einzuführen. War sie es einmal, so bestand im allgemeinen keine schwierigkeit, darin geschäfte zu machen, und gewöhnlich waren für solche Chopwaren bessere Preise zu erzielen, als für unmarkierte; es konnte vorkommen, dass ein und dieselbe Ware mit dem Chop sehr begehrt, ohne ihn aber unverkäuflich war.” Wagner, der einfuhrhandel nach China, 268.

coat of arms of the merchant, the samples of swiss trading houses show cows, swiss flags, a mountain railway, a chamois, while the dutch had ships, anchors, tulips, and the British displayed royals, coronations, Britannia, and patriotic scenes of ships and sea.76 But they soon found out that the symbol carried information and that they had to adjust their libraries to suit the taste of their consumers. In a letter dating 1884 one partner of the swiss trading house diethelm & Co wrote to a colleague that they had had to learn the hard way. They had used the chamois as trademark for their matches in singapore. Had they instead employed the “half-moon and star”-mark—a central symbol among their Malay clientele—they would have done much better.77

Whether end-consumers had an impact on the branding practice cannot be verified because of lack of sources. Court cases indicate that the european merchants were not well informed about the brand knowledge of the consumers.78 For them it was a tool in the whole-sale trade. We can only assume that brands helped to bridge the vari-ous ethnic gaps in the trade. The merchandise went from european merchants, then through Chinese, Indian, Buginese or Yemeni whole-salers and Chinese and Malay retailers, and then finally to the con-sumers.79 european merchants attempted to strengthen business relations by visiting their clientele in the bazaar and exchanging gifts on Christmas and Chinese new Year,80 or—in the case of the Chinese—by sitting down with the Malay retailers, chewing sireh and chatting for hours, before coming to a deal.81 However, social rela-tions alone were inadequate. Mistrust would have prevailed in the trade were there no brands to guaranty consistent quality. In revealing business relations the brands made the bazaar more transparent.

76. dA A 6.1/2 Ticketbooks. gZ, Historisch Centrum Overijssel, 168.2, Box 3. Tickets. susan, Textile ticket printing and pattern card making.

77. dA: A 2.7. riedtmann to diethelm, 25 July 1884. Procter & gamble pre-viously introduced a moon and star mark for candles. see Pennington et al., Customer branding of commodity products, 462f.

78. Johnston v Orr-Ewing (1882) 7 House of Lords 219. Guyer v. Imhof, Blumer

& Co (1891) schweizerisches Bundesgericht 42.

79. djie, distribueerende tusschenhandel, 5–15. For the Bugis see Trocki, Prince of pirates; for the traders of the Hadramaut in singapore see Clarence-smith et al., Hadhrami traders, scholars and statesmen in the Indian Ocean, 1750s–1960s; for the different Indian groups see sandhu, Indian communities in southeast Asia; for trading minorities in general see dobbin, Asian entrepreneurial minorities; McCabe, diaspora entrepreneurial networks.

80. On mutual gifts in business relations see Berghoff, Wirtschaftsgeschichte als Kulturgeschichte, 154; Tong Chee Kiong et al., guanxi Bases, Xinyong and Chinese Business networks, 81. For a detailed account of business relations in the bazaar in singapore see Zangger, Koloniale schweiz, Chap. A.4.

81. Bradell, notes on the Chinese in the straits. On the cultural capital of Chinese traders in the exchange with Malay traders see Andaya, Cloth Trade in Jambi and Palembang.

Although determining the extent of Asian end-consumers’ influ-ence on the branding of european cloth is a somewhat speculative venture, it is safe to say that shipper’s ticket are an example of con-sumer branding82: documentation shows that trademark owners reacted to the demands of Asian buyers, be they retail traders or end-consumers. Their influence can be seen by the very fact that products were branded and by the choice of symbols used. The shipper’s tick-ets are thus an example for the fact that globalization works simulta-neously top-down and bottom-up.83

The local name of a chop

european brands always had a local name in Malay, Hindi or Chinese. For example the trademark with the anchor would be known as “chop sauh” in the bazaar of singapore and as “tjap saoeh” in the dutch east Indies.84 By the 1860s marks such as “tjap boerong” (bird mark) or “tjap koeda” (horse mark) were so well established that the term became generic for a specific type of yarn or cloth in Java. Market reports regularly listed the prices of these items next to other yarns and types of cloth.85 Customers in the southeast Asian markets were quite conservative and usually stuck to an established brand, if the quality remained consistent.86 A well-established name in the bazaar equaled a monopoly. As chopped goods tended to guarantee higher turnover and better prices, trademark infringement and coun-terfeiting was rampant.87 Most new trademarks tried to imitate those already established, and certain motives such as the eagle, the tiger, the elephant, the cock, or the anchor existed in many variations with minimal differences. This was a decade or two before the introduc-tion of a thorough trademark law.

And even after the establishment of registers, protecting the image deposited in the trademark registers in Britain or elsewhere in europe was less important than defending the name established in the bazaar. One of the most prominent cases was that of Johnston v. Orr Ewing, which was heard before the House of Lords in 1882. Both firms used a mark with two elephants for yarn on the market in Bombay. Although 82. For consumer branding see Pennington et al., Customer branding of com-modity products; duguid, developing the brand, 433ff.

83. This argument is also brought forward by Cochran, Chinese Medicine Men. 84. “Tjap” is the colonial dutch transcription of the Malay “cap.”

85. see e.g., nieuwe rotterdamsche Courant, 28.4.1865. 86. Kelling, Het jaarbeurswezen in nederlandsch-Indië, 232.

87. I follow the distinction by da silva Lopes/Casson, where trademark infringement is the copying of the mark only, counterfeiting the copying of both the mark and the product. da silva Lopes et al., Brand Protection and globalisation of British Business.

european merchants and Indian middlemen could easily distinguish the two marks, the Lords ruled that even though they had a different design and carried different names, nevertheless the native buyers might be deceived, as they are used to buying the yarn under the name “Bhe Hathi” (two elephants). someone who uses a similar design for a trademark ought to “appropriate it with such precautions, that reasonable probability of error should be avoided.”88 In a similar case of 1906 in singapore between two trading houses both using anchors as trademarks, the plaintiff asked “(…) only that the defend-ants be restrained from using such a representation of an anchor as would result in their goods being called by the name of ‘chop sauh’, which was the exclusive property of the plaintiff.”89 These two exam-ples clearly demonstrate the shift in emphasis put forward by Frank schechter. In semiological terms the trademark as signifier points less to the manufacturing source, but instead to the product.90

On the other hand merchants also learned of the dangers in a loss of distinctiveness. In the case Katz Brothers Ltd. v. Kim Hin & Co involving an eagle mark on brandy from 1899 the supreme Court of the straits settlements decided that Katz Bros could not claim the mark as its property, because “chop burong” brandy, as it was called on the market, was sold by eight different merchant houses and that it had become synonymous with cheap brandy.91

Textile trademarks for the Asian markets were instrumental in establishing a jurisdiction on trademarks in general—especially in regard to the notion of distinctiveness. supreme courts both in Britain and in switzerland heard cases on trademarks in the textile trade with Asia.92 The case before the House of Lords was one of five cases on trademarks in the period 1862–1882 that were constitutive for the legal practice afterwards. Bently regards this period as forma-tive for many aspects of British trademark law; the textile trade had a prominent role in its elaboration.93

The merchants in the textile trade in Asia were thus well acquainted with word marks and even product lines, since tickets of different colors were used to indicate differences in qualities. This happened before the introduction of sunlight soap by Lever Brothers, which usually is considered a milestone for innovation in branding.94

88. Cox, A manual of trade-mark cases, 371–74. 89. “Anchor Trade Mark,” straits Times, 4.12.1906.

90. Beebe, The semiotic Analysis of Trademark Law, 677–81.

91. ng-Loy Wee Loon, Trade Marks, Language and Culture: The Concept of distinctiveness and Publici Juris, 5f.

92. Johnston v Orr-Ewing (1882) 7 House of Lords 219. Guyer v. Imhof, Blumer

& Co (1891) Bundesgericht 42.

93. Bently, Making of Modern Trade Marks Law.

Supply chains and the ownership of marks

Without a doubt brands were used to fight competitors; more impor-tantly, however, they can be seen as a strategic tool in a supply chain. This aspect has been emphasized by Paul duguid95 and can be clearly observed in the textile trade. Brands helped the trading houses gain control over the supply chain.

Looking at the marks of swiss and dutch producers and trading companies in the cotton piece good business one can see some dis-playing the name of the producer, some the names of both producer and trading house in Asia, but the majority carried only the name of the trading house.96 In the early phase of globalization distribu-tion was generally externalized. Often there were close network ties between producers or merchant houses in the textile centers on the one hand and agency houses overseas on the other—at least in the main export markets. These ties involved capital investments or familial relationships between the two.97 In the cotton weaving industry of eastern switzerland familial and regional networks connecting producers and agencies were particularly dense. The swiss merchants in singapore most often had completed a commer-cial apprenticeship with a producer and were then sent overseas. How products were brought to market was left to the merchants. Merchants provided producers with market information—crucial knowledge in the fast changing business of fashion. They told them what patterns to produce in what quantities and how to wrap the goods.98

This division of labor between producers and distributors is to be expected considering the great distance between the locations of pro-duction and the markets. Local knowledge was essential for intro-ducing new brands, and established brands had to be nurtured on site. Moreover, merchant houses could not file complaints against an infringement of a trademark of a producer they represented, but only for their own trademarks.99 The example of the Koninklijke stoomweverij nijverdal (KsW) shows how difficult it was, even for large producers, to keep control over their trademark overseas. g. en H. salomonson established in 1816, founded the KsW in 1851 and shortly thereafter brought their products to overseas markets

95. duguid, developing the brand.

96. This comprises the archives of Mn, BL, BJ (see bibliography). see also Higgins et al., The trade mark question and the Lancashire cotton textile industry, 209.

97. On merchant networks in Britain see Chapman, Merchant enterprise in Britain. On agency houses in Asia see Jones et al., Merchants as Business groups.

98. Fischer, Toggenburger Buntweberei auf dem Weltmarkt. 99. sen, The law of monopolies in British India, 303.

under their own trademark. As they had received the honorary title “Koninklijk” (royal), bestowed by the royal family, they also used the royal dutch emblem, a mark with a prestigious symbolic value. Because of this the products of the KsW had a quasi-official status, and their mark was soon well known in Java (one of the main markets of the KsW) as “tjap ringgit” (imperial eagle mark).100 But its early success in the intercontinental textile trade proved to be detrimental once the new system of trademark registration came into being. The royal symbol could not be registered due to its public character, and the KsW regularly had to fight imitators of their mark. several trading houses in Manchester used the mark, slightly changing the symbol and adding fictitious dutch firms as producers, to sell their products in Java.101 The KsW only heard about these imitations after damage was done—their trading partners in Java seemingly undisturbed by the practice.

Obviously a trading company overseas was in a much better posi-tion to protect its interests. Only they were able to introduce new brands. They also had first sight of what was happening in the mar-ket and could react quickly in case of infringements or if a brand performed badly. Their access to local knowledge privileged them in comparison to the producers. In the case of swiss trading networks, the producers, who in the 1860s had control over a number of trading houses in the east, had by the 1880s lost their control over distribu-tion to the merchants. By the beginning of the twentieth century pro-ducers in switzerland found it increasingly difficult to get access to markets in the east themselves.102 Instead the trading houses acted as gatekeepers and issued quotas to different producers, allowing them to produce goods under the label of their trademark. For the merchant houses, selling the merchandise under their own brand was also a way of hiding the sources of supply. The brand had thus lost the con-nection to the producer.

For example, the factory mark of a swiss producer in figure 3

above was still in use at the turn of the twentieth century, but only for the most expensive items “as an additional decorative element,” as the packaging instructions of the trading house in singapore reveal.103 some producers, however, were able to sidestep traders. For example, a producer who had an exclusivity arrangement with a merchant in Bangkok sold his merchandise via another merchant 100. sen and ringgit also refer to the Mexican silver dollars that were used as currency in the region. den Otter et al., “Twentse tjaps.”

101. Burgers, 100 Jaar g. en H. salomonson, 196–200.

102. sulzer, Vom Zeugdruck zur rotfärberei, 239; Tschudi, Hundert Jahre Türkischrotfärberei, 39.

there and instructed the packaging people to use only the merchant’s trademark.104

In Manchester there was also a division of labor between the pro-ducers in Lancashire and Cheshire and the merchant houses in the city. The former concentrated on technique, while the latter were responsi-ble for marketing and usually had control over trademarks.105 Though they also had to negotiate trademark questions with partners overseas, they were in a better position to do so in comparison to the factories (recall the example of the swiss producers). After all, Manchester was the centre for the registration of textile marks for the whole empire.

dutch producers, on the contrary, were more successful in establish-ing their own marks, at least by the 1920s. The case of Vlisco, produc-ers of dutch wax cloth for Java, and, especially, later for West Africa, shows them to be coping with the fact that distant markets had become an abstract variable. At first, marketing activities were limited to get-ting orders from trading partners. In the 1930s, however, Vlisco started investing in direct access to the markets. The fact that their product had a unique visual appearance and their patterns were so popular on the market, helped them to regain control over the supply chain. Their branding is still very traditional using selvedge patterns.106

Conclusion

none of the brands displayed on the shipper’s tickets went on to become a global success. They were as ephemeral as their medium. This might be the reason why they do not appear in traditional accounts of branding history. nevertheless, these tickets had effects on branding in europe.

The two decades between 1860 and 1880 saw fundamental changes of the legal concept of the trademark including registration and an accompanying framework to assess what could count as a trademark, what the prerequisites for a mark to be registered were, and what would be regarded as infringement. Around the same time, busi-nesses began to experiment with new ways of advertising and brand-ing. Advertisements and brands used color, branding put more focus on the product than the producer. We can regard this period as a trial-and-error process in branding on a global scale. The textile tickets in the Asian trade sent out a strong signal to interested business people

104. Ibd.

105. On trademark questions see redford, Manchester merchants and foreign trade, 140–43.

106. For the case of Vlisco see Ingenbleek, Marketing als bedrijfshistorische invalshoek; Hoogenboom et al., From local to grobal, and back. Clark, Lincoln green and real dutch java prints.

and trademark professionals: They showed the potential of color for branding; they showed that pictorial brands proved to be effective as a language working independently of script; they also showed that remote consumers would translate the sign into their own language; furthermore they showed that the sign would work as a marketing tool, even if it had no connection to a producer.

Again it has to be emphasized that the tickets were not the only brands to use symbols. But the existence of a large number of ship-per’s tickets used in the textile trade that made uniform use of arbi-trary symbols likely affected branding as a whole. First there was an impact on the visual appearance of brands. It opened up the visual repertoire, which potentially had effects on the nascent advertising industry. But while we can observe the rising popularity of eastern motifs in trade cards, this popularity has to seen against the back-ground of a more general interest for eastern art in the Aesthetic movement. The fashion for anything eastern in the printing business in the last quarter of the nineteenth century might have influenced the development of branding in other sectors. The development of matchbox branding especially has to be studied in this regard.

Second, these visual brands had effects on the trademark law, since courts had to establish law practice, how to assess distinctive-ness of pictorial marks. shipper’s tickets have a prominent place in cases regarding distinctiveness.

Third, it is in the southeast Asian textile trade that we can see a shift in the conception of the trademark: its connection to a source became less relevant. Instead the mark stood for the product itself. Overseas trade is the obvious site for this process to unfold, since physical and cultural distance impeded the establishment of direct connections between producers and customers. For many textile pro-ducers, trading companies were inevitable go-betweens, bringing their products to markets overseas and so they left marketing and branding strategies to the trading company’s discretion. Textiles were by far the most important export item to markets overseas and merchants were accustomed to marks well before the advent of registration.

Bibliography of Works Cited Books

Aslanian, sebouh d. From the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean: The

Global Trade Networks of Armenian Merchants From New Julfa. Berkeley:

University of California Press, 2011.

Baghdiantz McCabe, Ina, ed. diaspora entrepreneurial networks: Four Centuries of History. Oxford: Berg, 2005.

Berghoff, Hartmut, ed. Marketinggeschichte: Die Genese einer modernen

Sozialtechnik. Frankfurt a. M.: Campus 2007.

———. Wirtschaftsgeschichte als Kulturgeschichte: Dimensionen eines

Perspektivenwechsels. Frankfurt a. M.: Campus, 2004.

Bevan, Andrew, and david Wengrow, eds. Cultures of Commodity Branding. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2010.

Burgers, roelf Adrianus. 100 Jaar G. en H. Salomonson, dissertation ed. rotterdam: nederlandsche economische Hoogeschool, 1954.

Chandler, Alfred d., and Takashi Hikino. Scale and Scope the Dynamics of

Industrial Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.

Chapman, stanley d. Merchant Enterprise in Britain From the Industrial

Revolution to World War I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Chiang Hai ding. A History of Straits’ Settlements Foreign Trade 1870–1915. singapore: national Museum, 1978.

Clarence-smith, William g., and Ulrike Freitag eds. Hadhrami Traders,

Scholars and Statesmen in the Indian Ocean, 1750s–1960s. Leiden: Brill,

1997.

Cochran, sherman. Chinese Medicine Men: Consumer Culture in China and

Southeast Asia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

dahl, gunnar. Trade, Trust, and Networks: Commercial Culture in Late

Medieval Italy. Lund: nordic Academic Press, 1998.

davis, Alec. Package and Print the Development of Container and Label

Design. London: Faber & Faber, 1967.

de Waal, engelbertus. Aanteekeningen over Koloniale Onderwerpen, vol. 1. ‘s-gravenhage, The netherlands: M. nijhoff, 1865.

djie, Liem T. De Distribueerende Tusschenhandel der Chineezen op Java. ‘s-gravenhage, The netherlands: Martinus nijhoff, 1947.

dobbin, Christine. Asian Entrepreneurial Minorities: Conjoint Communities

in the Making of the World-Economy 1570–1940. richmond: Curzon, 1996.

Farnie, douglas A. The English Cotton Industry and the World Market, 1815–

1896. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979.

gallop, Annabel T. Malay Seal Inscriptions: A Study in Islamic Epigraphy

From Southeast Asia. London: sOAs, 2002.

Hudson, graham. The Design & Printing of Ephemera in Britain & America,

1720–1920. London: British Library, 2008.

Kaduck, John M. Advertising Trade Cards, 1st ed. des Moines, IA: Wallace-Homestead Book Co, 1976.

Last, Jay T. The Color Explosion Nineteenth-Century American Lithography. santa Ana, CA: Hillcrest Press, 2005.

Lewis, John. Printed Ephemera the Changing Uses of Type and Letterforms in

English and American Printing. Woodbridge: Antique Collector’s Club, 1990.

Lury, Celia. Brands: The Logos of the Global Economy. International Library

of Sociology. London: routledge, 2004.

Maczak, Antoni, and Ursula Philips. Travel in Early Modern Europe. Oxford: John Wiley & sons, 1995.

McClintock, Anne. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the

Meyer, Carl. Die historische Entwicklung der Handelsmarke in der Schweiz. Bern, switzerland: stämpfli, 1905.

north, douglas C. Structure and Change in Economic History. new York: W.W. norton, 1981.

Olegario, rowena. A Culture of Credit: Embedding Trust and Transparency

in American Business. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

rabo, Annika. A Shop of One’s Own: Independence and Reputation Among

Traders in Aleppo. London: Tauris, 2005.

redford, Arthur. Manchester Merchants and Foreign Trade, 1850–1939, vol. II. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1956.

rickards, Maurice, and Michael Twyman. The Encyclopedia of Ephemera:

A Guide to the Fragmentary Documents of Everyday Life for the Collector, Curator, and Historian. new York: routledge, 2001.

rouffaer, gerrit P., and Hendrik H. Juynboll. De Batikkunst in

Nederlandsch-Indië en haar Geschiedenis. Utrecht, The netherlands: A. Oosthoek, 1914.

salaman, Joseph s. A Manual of the Practice of Trade Mark Registration. London: shaw & sons, 1876.

sandhu, Kernial s. Indian Communities in Southeast Asia, 2nd repr. ed. singapore: Institute of southeast Asian studies, 2008.

schechter, Frank I. The Historical Foundations of the Law Relating to

Trade-Marks. new York: Columbia University Press, 1925.

sen, Prosanto K. The Law of Monopolies in British India. Calcutta: MC sircar & sons, 1922.

sherman, Brad, and Lionel Bently. The Making of Modern Intellectual

Property Law: The British Experience, 1760–1911. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1999.

slater, don. Consumer Culture and Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1997. strachan, John. Advertising and Satirical Culture in the Romantic Period.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

sulzer, Klaus. Vom Zeugdruck zur Rotfärberei: Heinrich Sulzer (1800–1876)

und die Türkischrot-Färberei Aadorf. Zürich: Chronos, 1991.

sunderland, david. Social Capital, Trust and the Industrial Revolution, 1780–

1880. London: routledge, 2007.

Tedlow, richard s., and geoffrey Jones. The Rise and Fall of Mass Marketing. London: routledge, 1993.

Trocki, Carl A. Prince of Pirates: The Temenggongs and the Development of

Johor and Singapore 1784–1885. singapore: Univ. Press, 1979.

Tschudi, Peter. Hundert Jahre Türkischrotfärberei, 1829 - 1928: Geschichte

der Rotfarb und Druckerei Joh. Caspar Tschudi in Schwanden. glarus:

Buchdruckerei neue glarner Zeitung, 1931.

Vleming, J. L. Het Chineesche Zakenleven in Nederlandsch-Indië. Weltevreden: Landsdrukkerij, 1926.

von Bavier, ernst. Japan’s Seidenzucht, Seidenhandel und Seidenindustrie. Zürich: Orell, Füssli, 1874.

Wadsworth, Alfred P., and Julia de Lacy Mann. The Cotton Trade and

Industrial Lancashire, 1600–1780. Manchester, UK: Manchester University