46

Nostalgic Experiments

Memory in Anne Carson’s Nox and Doug Dorst and

J.J. Abrams’ S.

Sara Tanderup

AbstractThe article discusses a tendency towards “media nostalgia” in contemporary experimental literary works. Authors such as Jonathan Safran Foer, Reif Larsen, Anne Carson, Steven Hall, Umberto Eco, J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst include images, drawing and photographs in their works, or they experiment with the visual and material qualities of writing and the book. The tendency can be explained as a reflection of the media development: The experimental texts draw attention to the book in an age where it can no longer be taken for granted. They recall an avant-garde aesthetics, but whereas the avant-garde is associated with ideas of future and progress, the new texts generally focus on issues of memory and the past. I argue that they are also about memory at a media level; “remembering” the book. I explore this tendency by analyzing Anne Carson’s

Nox (2009) and S. (2013) by Doug Dorst and J.J. Abrams. Both works recall the aesthetics of ‘rare books’,

scrapbooks and artists’ books. They celebrate the book as an auratic object and as an old medium while also embracing the contemporary media culture. Paradoxically, they are thus characterized by a ‘manufactured aura’ – yellowing pages to be bought anytime, anywhere at Amazon.com.

Résumé

Cet article discute d’une tendance vers une nostalgie des médias dans des oeuvres contemporaines expérimentales. Des auteurs comme Safran Foer, Reif Larsen, Anne Carson, Steven Hall, Umberto Eco, J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst incluent des images, dessins et photographies ou expérimentent avec les caractéristiques visuelles et matérielles de l’écriture et du livre. Cette tendance peut s’expliquer comme une réflexion du développement des médias: les textes expérimentaux attirent l‘attention sur le livre à l’âge ou il ne peut plus être pris pour évident. Ils rappellent une esthétique d’avant-garde mais la ou l’avant-garde est associée avec le future et le progrès, les nouveaux textes généralement se concentrent sur des problématiques de la mémoire et du passé. Je soutiens donc qu’ils sont aussi a propos de la mémoire au niveau du média: se rappeler le livre. J’explore cette tendance en analysant Nox de Anne Carson et S de Dorst et Abrams. Les 2 rappellent une esthétique du livre rare et des livres d’artistes. Ils célèbrent le livre comme un « objet auratique » et comme un vieux médium tout en embrassant la culture médiatique contemporaine. Paradoxalement, ils sont caractérisés par une « aura manufacture”—pages jaunissantes qui peuvent être achetées n’importe quand, n’importe où sur amazon.com.

Keywords

47

“With the increasing electronic incorporeality of existence, sometimes it’s reassuring - perhaps even to have something to hold on to…” Chris Ware. Building Stories (2012).

Introducing his experimental graphic novel Building Stories (2012), Chris Ware associates this work with an idea of material stability: “something to hold on to.” In this article, I argue that this association is characteristic of what is currently happening to experimental literature. Whereas the notion of the experimental is historically associated with the avant-garde and with a celebration of future, progress and rupture, literary texts today often make use of experimental strategies in order to establish a sense of stability and continuity – hence resisting the “increasing electronic incorporeality of existence.” This tendency is expressed in several recent novels that combine intermedial experiments with a thematic pre-occupation with memory: Works such as Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2005) and Tree of Codes (2010), Reif Larsen’s The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet (2009), Anne Carson’s Nox (2009), Steven Hall’s The Raw Shark

Texts (2007), Salvador Plascencia’s The People of Paper (2005) and Umberto Eco’s La Misteriosa Fiamma della Regina Loana (2004) include images, photographs or drawings in the literary text, or experiment with

the visual and material aspects of writing and the book – all as part of an attempt represent and discuss issues of memory, history and trauma.

I argue that these new works are about memory at a media level as well: They “remember” the book and the printed novel in a time where neither can be taken for granted. Accordingly, scholars such as N. Katherine Hayles and Johanna Drucker have theorized these experimental novels as a reflection of literature’s reaction to the recent media development and to the arrival of new digital media. Considering the works of e.g. Foer and Plascencia, Hayles argues that “the novel is traumatized by the colonizing incursions of other media. These books respond to this trauma by bursts of anxious creativity, thereby changing what it means to be a novel in print” (2006, 85).

The experimental novels indicate an emerging self-consciousness about what it means to be a book. They celebrate the old medium, stressing ideas of continuity and literary tradition; however, their experimental aesthetics also reflect change, challenging a traditional understanding of the novel and confronting it with other media. Because of this tension, they may be read as reflections of what is currently happening to the novel: They indicate change combined with longing for continuity: “something to hold on to.”

I investigate this tendency by analyzing two recent works: Anne Carson’s Nox (2009) and S. (2013) by J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst. Both works are pre-occupied with issues of memory, amnesia and loss, and both are highly experimental – with yellowing pages, handwriting in the margins and photographs, postcards and letters inserted between or seemingly glued on to the pages. I argue that both works may be read as reflections of ‘media nostalgia’, celebrating the book as an old object and as a medium of memory that is positioned clearly in opposition to “the increasing electronic incorporeality of existence.” Both works evoke the aesthetics of “rare books” such as scrapbooks and artists’ books. They seem to remember the book as an auratic object, a tangible material artifact that is surrounded by cultural nostalgia. However both works also project the aesthetics of the rare books into appealing new works that are grounded in contemporary media culture.

My investigation focuses on these tensions in the two works: between their experimental strategies, redefining the book, and their occupation with nostalgia, memory and literary tradition; and between their celebration of “bookishness”, handwriting and yellowing pages, and their status as products of contemporary

48

media culture. These tensions point us towards reading them as reflections of the changing idea, status and expression of the novel in the digital age.

I. Nox

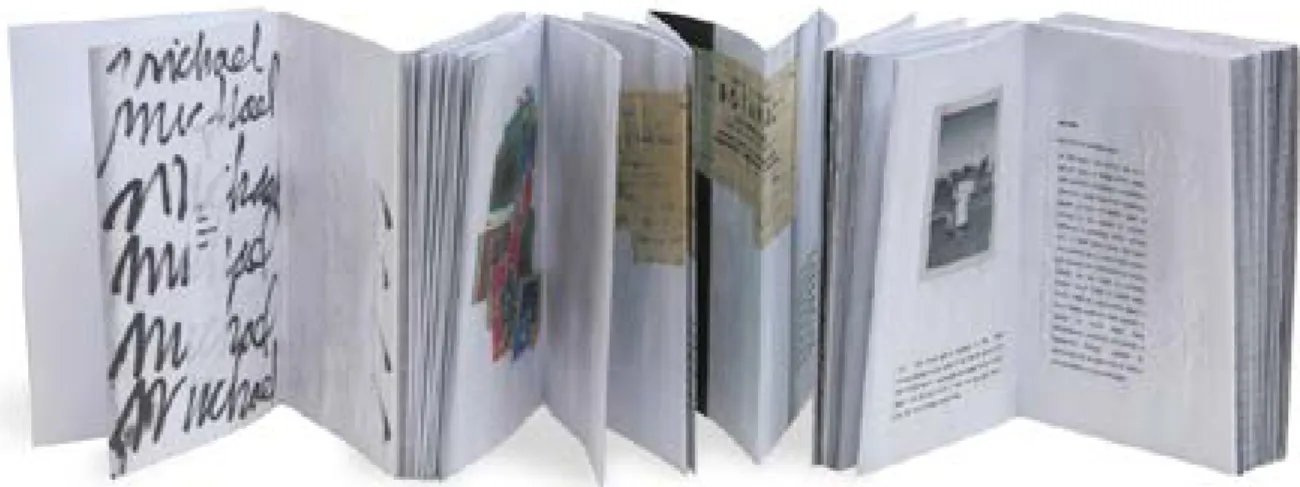

Nox is based on a scrapbook that Carson made for her brother Michael after his sudden death in 2000.1 It is

filled with photographs, fragments of letters and other pieces of text that are seemingly glued on to the pages. The pages are yellowing and most of the writing appears to be typed or written by hand. The work is presented in a leporello-format; it is folded like an accordion. Unfolded, it consists one long piece of paper, 25 meters in total. It is contained in a big, grey box. “When my brother died, I made an epitaph for him in the shape of a book,” it says on the back of the box. “This is a replica of it, as close as we could get.” The work is presented as “epitaph,” an inscription on a monument. In its massive grey box, it does indeed resemble a monument, or even a gravestone.

The introduction on the back of the box indicates an important tension in Nox: Whereas the original scrapbook was a personal /project (“I made an epitaph”), the replica is part of a collective process (“as close as we could get”) – involving others; that is, a publishing firm, an editor and not least Carson’s partner, Robert Currie, who is credited in the work for assisting in “the design and realization” of the book. The difference between the “I” and the “we” is crucial because it points to the tension in the work between the original scrapbook as an object of personal memory; a unique, handmade artifact – and the replica as a product of collaboration, submitted to mass production and meant for public consumption. By publishing her scrapbook, Carson includes it in the public sphere of literary culture, but by reproducing the image of the original book, she also insists on translating the intimacy of the private book into the published work.

The work is thus characterized by ambiguity: there is an ambition of immediacy, of getting “as close as we could get” to the original – and there is an awareness of the difference between “the real thing” and the reproduction, which may also be related to the work’s central occupation with memory: We cannot publish the

1 This section is based on my analysis of Nox in “Bits of Books in Boxes. Remembering the Book in Anne Carson’s Nox and Mette Hegnhøj’s Ella is my Name Do You Want To Buy It” in Media and Memory (Text, Action, Space 3), ed. Lars Sætre, Patrizia Lombardo and Sara Tanderup, forthcoming, and in “Intermedial Strategies of Memory in Two Contemporary Novels” in Kunstlicht, vol. 36, no. 1, 2015 – however, my argument has been developed in the present text, because I focus on the aspects of the work that will lead me towards considering it in relation to S. For a detailed analysis of Nox, see also Kiene Brillenburg Wurth: “Re-vision as Remediation. Hypermediacy and Translation in Anne Carson’s NOX” in Image & Narrative, vol. 14, no. 4, 2013.

Fig. 1: By Anne Carson, from NOX, copyright ©2010 by Anne Carson. Use by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

49

original scrapbook, and we cannot reawaken the dead. But we can remember, produce an image of the past, and of the book with handwriting and yellowing pages.

This reflection occurs in the work at another level as Nox is structured around the translation of a Latin poem: Poem “number 101” by the Roman poet Catullus is also about the loss of a brother. Carson is a professional translator of texts from Classical antiquity. Throughout Nox, the process of translating poem 101 is presented along with the process of remembering the brother. Entries from the Latin dictionary are presented, reflecting the ambition of getting “as close as we could get” to the original meaning of the poem. However, the entries are subtly invaded by Carson’s own writing. Thus, for “aequora” we read:

Aequor aequoris neuter noun

[AEQUUS] a smooth or level surface, expanse, surface; a level stretch of ground, plain; inmensumne

noctis aequor confecimus? have we made it across the vast plain of night? the surface of the sea

especially as considered as calm and flat, a part of the sea; a sea per aperta volans aequora soaring over open sea; the waters of a river, lake, sea; tibi rident aequora ponti the waters of the sea laugh up at you (1.3).2

Notably, the lexical entries subtly recall or foreshadow the story about Carson’s brother. For instance, the description of the aequora as the “surface of the sea especially as considered calm and flat” evokes the description later in the work of the brother’s ashes being thrown out at sea. Carson notes that, “his death came wandering slowly towards me across the sea” (6.1). Furthermore, the description of aequora as a “smooth or level surface” may be connected to the physical surface of the work – indeed, the published replica is characterized by a physically smooth surface, which contrasts strikingly with the original scrapbook’s explicitly tactile, uneven appearance.

The lexical entries thus function to confront and connect the different discourses that are at stake in the work; the personal project of remembering the brother and the processes of translating the poem and remediating the scrapbook. The work repeatedly stresses a dynamic relationship between individual and cultural memory, original and translation. Carson remembers the brother’s death through the cultural context of the poem, however, the meaning of the poem is also changed, disturbed, by her personal translation3 – as is

reflected when the translation of the poem is finally presented on a wet, dissolving yellowing page. It has been manipulated to the extent that the original text has become illegible.

In this way, Nox presents a process where the past is being translated only to dissolve materially. What is presented in the end is the absence of the past, reflected in the final illegibility of the poem. This absence is also represented in the poem itself. According to Carson’s translation, it says: “I arrive at these poor, brother, burials/ so I could give you the last gift owed to death/ and talk (why?) with mute ash.” The poem thus highlights an idea of muteness and absence in relation to the material remnant of the dead, the ash. Carson’s book may be considered as a similar remnant. It celebrates the aesthetics of fragmentation and loss, drawing attention to that which is lost in the process of translating or mediating the past.

However, it also simulates immediacy, evoking a sense of “presence” through its experimental

2 Since Nox is unpaginated, I quote by referring to the numbered sections.

3 Accordingly, as noted by Wurth, Carson’s translation is a subjective poetic translation in the sense of Walter Benjamin. For a further discussion of this perspective, see Wurth 29.

50

aesthetics – indeed simulating the presence of the original handmade book.4 In an interview, Carson points

to the fact that the remediation of the scrapbook into a printed, public text appears as another process of translation or memory at stake in the work. According to her, it was important to find a way to reproduce her scrapbook so that, as she says, it “would still be as intimate, so that when you read it you still feel that you are just one person reading it, so it doesn't seem like so much a violation because a fiction of privacy is maintained” (interview by Teicher). The replica is produced by means of scanning the original notebook and then Xeroxing the scans. Carson describes scanning as “ a digital method of reproduction, it has no decay in it, it has no time in it, but the Xerox puts in the sense of the possibility of time” (interview by Teicher). The work’s experimental expression is thus supposed to support the illusion of the book as an intimate object of memory. It is made as an image of a scrapbook to produce a sense of presence, rendering the past tangible and “present.” Nox may be thus read as according to Julia Panko’s argument that the materiality of the book gains new importance in the age of new digital media:

The materiality of the book is important not in the vein of glib arguments about the readers being unable to take their Kindles into the bath, but because it can be the means of another kind of record-making, created from the physical traces a reader’s body leaves in the process of handling a book, rather than from the reduction of a human being to a data set or literary description. (Panko 295)

Panko describes the book is an especially embodied, intimate form of writing that is positioned clearly in opposition to the digital media. By maintaining the scrapbook aesthetics, Carson highlights these qualities; presenting her book as a thing that has been “touched” by time and use. Indeed, it is a monument, remembering the brother as well as the book itself.

However, this celebration of the book as an intimate object is undermined by the remediation of the scrapbook into a published work (Wurth 27). The worn expression of Nox is contrasted by its glittering surface and its appearance as a delicious new object in the monumental box. Nox might thus paradoxically be characterized as an example of a “manufactured aura.”

This tension may also be seen in the fact that the work is juxtaposed between the tradition of the classical artist’s book and the commercialized printed book. It imitates the tactile expression, the experimental and handmade quality of the artists’ book, but it has been widely published and translated into several languages. The resulting ambiguity turns Nox into an object of nostalgia. There is longing for capturing the past, and for restoring the original book in this work – however, this also implies an idealization of the book as an intimate, auratic object. The experimental book object becomes a space for reflection about loss, a lost brother, lost time, and finally, there is a loss of authenticity at stake as the scrapbook is turned into a commercialized product of the contemporary media culture.

II. S.

Another example of the tendency towards intemedial experiment in contemporary literature is S., a recent novel by J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst.5 Like Nox, this work appears to celebrate the material book,

4 I use the term “presence” here in the sense of Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, who in his work “The Production of Presence” (2004) defines “presence” as opposed to “meaning”: ”What is present for us […] is in front of us, in reach of and tangible for our bodies” (17). In the case of Nox, we see that the poem itself as a tangible artifact on yellowing paper seems “present,” while the meaning of the poem – and the past – remains absent, illegible.

5 The section on S. is based on my extensive analysis of the work in “A Scrapbook of You + Me. Bookish Nostalgia and Intermediality in J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst’s S”, forthcoming in Orbis Litterarum.

51

while also challenging the traditional form of the printed novel through visual and material experiments. Thus, it points towards a situation where the novel becomes aware of the specificity of printed books while also letting the story escape the book and migrate into other media.

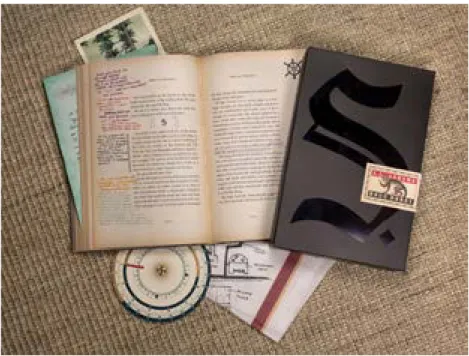

S. arrives in a sealed black slipcase. The authors and publishers are mentioned on the slipcase and the

seal, but by breaking the seal, you enter the fiction: Inside the case is what seems to be an old library book entitled The Ship of Theseus. It is written by V.M. Straka and published by Winged Shoes Press in 1949. This fiction is supported by the visual and material appearance of the work: It resembles an old library book in every detail, with an imitated cloth cover and yellowing pages. Inside the book are replicas of stamps from the library, such as “KEEP THIS BOOK CLEAN” and “property of Laguna Verde High School Library.” In the back is a list with stamps and names and dates of previous borrowers of the book, dating back to the 1950s. Finally, S. is filled with ephemera stuck in between the pages, such as handwritten letters, postcards, old photographs, newspaper clippings and even a drawing of a map on a napkin.

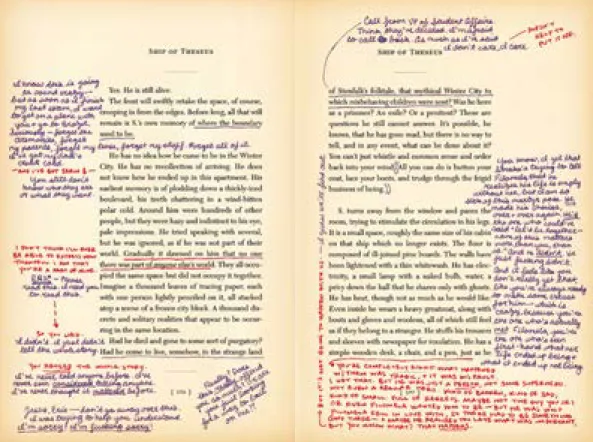

In this way, the borderlines between the text and context are blurred. The story slips out of the printed text, and into the context; into the paratexts and into the margins of the book. The margins are filled with handwriting: There is the neat capitalized writing of a man, Eric Husch, and the feminine scrawl of a young woman, Jennifer (Jen) Heyward. Both appear to be reading The Ship of Theseus at a library, taking turns picking up the book and leaving it for the other to find. In this way, they exchange margin notes, gradually falling in love while interpreting the novel and discussing the true identity of the mysterious author Straka.

In S., the book is thus staged as a meeting place, a space of intimate communication between the

readers. As in Nox, the focus on the material aspects of the literary text is connected to issues of memory and loss: The printed novel is about S., an amnesiac man who tries to regain his lost memory through writing: “Write down what you suspect, what you know about yourself – even if that won’t fill a single page. And then, maybe, start piecing together who you are” (77). This pre-occupation with memory is repeated as Eric and Jen inscribes their own memories into the margins of the novel while trying to get to know each other. In this way, the book itself is turned into an object of memory, bearing witness to their individual stories as well as to their

52

shared history of reading, since their notes from different read-throughs appear together at the pages.

Fortunately, the handwriting is color-coded so that the reader is able to distinguish between comments from different readings: Thus, the earliest notes are Eric’s written in fainted grey pencil, referring to his reading of the book as a youth. The first time he and Jen read through the novel together, Jen’s notes are written in blue and Eric’s are black; the second time, Jen’s are orange and Eric’s green, the third time, Jen’s are purple, Eric’s red, and the fourth time, both write in black. In this way, the pages appear as palimpsests where different times of writing, different stories emerge simultaneously at the surface of the text. Looking back at their earlier comments, Eric suggests that the book has been turned into “a scrapbook of you + me” (76).

This idea of turning a printed novel – furthermore, a public library book – into a private handwritten scrapbook points us towards reading the work as a reflection of the changing status of the novel. As suggested by Panko, the book, when confronted with the new media, gains importance as a material artifact that is able to render the past through the physical traces left by other readers. Thus, it is staged as a space of intimacy and memory as opposed to the new media, which are associated with fluidity and immateriality, even with the loss of human, enbodied memory.6

There certainly seems to be a resistance against the new media at stake in S. Eric resists using new means of communication. “I don’t use email,” he says. “Don’t trust it.” “Paranoid?” Jen asks. “Got hacked a few times last year,” he answers. “Someone was trying to steal my work” (5). To be hacked, losing data and “intimate” information is a fear that commonly surrounds the new media. Evoking this fear, S. may be considered as part of a common cultural tendency towards resisting digital culture. The work is intended as

6 The idea of the new media as less ”material” than the old media is widespread – see below p. 10-11. See also Brown p. 71 or Panko p. 280-81. However, it primarily focuses on the experience of these media, and it has been criticized by among others Hayles, who makes a point in stressing that new media are as based in materiality as old media.

53

a “celebration of the analog,” as the author J.J. Abrams has argued (interview by Rothman).7 Like Nox, S. is

thus characterized by nostalgia for the old media, for handwriting, yellowing pages and for the book itself. It is nostalgic, because it is based on an idealization of these old media that is not grounded in reality – as suggested by the fact that S. itself is based on an illusion. The yellowing color is artificial, and the handwriting is scanned onto the pages. The work is designed to look old and worn while it is in fact an appealing new book. Like Nox, it may thus be described with the notion of “manufactured aura.”

Accordingly, I want to stress an ambiguity in S. It celebrates what Jessica Pressman calls the “aesthetics of bookishness”8, the idea and culture and tradition of the book, while it is in fact fundamentally infiltrated

in contemporary media culture. This ambiguity, I argue, is characteristic of what is happening to the printed novel now. It is becoming aware of the specific qualities of the book while also increasingly becoming a part of, and dependent on, the new media culture. As mentioned above, S. is produced through digital technologies highlighting the fact that new media makes it possible, easier and cheaper to produce such experimental works. Doug Dorst points out that the marginalia were originally inscribed into the manuscript by means of the comment function in Word, hence reflecting a reversed process of remediation, where the text is digitally created and then made to appear handwritten afterwards.9

Digitalization is of course hard to avoid at this level of production – as pointed out by Hayles, almost all literature now is “computational” (2008, 43). However, S. makes a particular case because the logic of digital media also seems to be inscribed in the narrative structure and idea of the work: Although Eric resists the use of email, his own conversation with Jen strikingly resembles an email conversation. It is characterized by short messages and quick replies, and it is organized in strings of comments upon comments, hence also resembling the organization of communication in new social media such as Facebook and Twitter. This association is supported when taking into consideration the situation of communication depicted in the work: Jen and Eric exchange the book and communicate through margin notes, but do not physically meet until far into the story. While this idea of establishing intimacy while upholding anonymity seems quite unlikely within the physical setting of the library, it fits well into the world of online communication.

Thus, S. seems to be grounded in a logic that is informed by the new social media. That is confirmed by

the fact that Eric and Jen have their own active Twitter accounts, where they have continued their discussion and investigation of the Straka mystery after the book was published. Thus, the fictional characters migrate out of the book and into other media. Furthermore, in spite of its resistance towards the new media, S. has been developed online on many different media platforms. A book trailer was released before the novel was published, and afterwards, several “alternate endings” for the novel has been released online on readers’ blogs dedicated to the work. S. indeed develops its story across different media.

This fact points to it as an example of what Henry Jenkins has described as contemporary convergence culture. “By convergence,” Jenkins argues, “I mean the flow of content across multiple media platforms, the cooperation between multiple media industries, and the migratory behavior of media audiences who will go almost anywhere in search of the kinds of entertainment experiences they want” (3). Furthermore,

7 Abrams, who is a famous producer of Hollywood film and TV series, had the idea for S. and then “casted” Dorst to actuallyu write it. S. is thus also formed by the modes of production that characterize the world of popular visual media.

8 Pressman presents “the aesthetics of bookishness” as an “emergent literary strategy” (Pressman n.p.) in recent novels that celebrate the material and visual aspects of the book in an age where it can no longer be taken for granted.

9 Cf. interview with Doug Dorst at Kansas Public Library. 8.5. 2014. Web. 14.1 2015. https://whoisstraka.wordpress.com/2014/05/08/ live-interview-with-doug-dorst/

54

convergence culture is linked to a participatory turn: “Convergence represents a cultural shift as consumers are encouraged to seek out new information and make connections among dispersed media content” (3). Consumers, or readers, become active participants.

Of course, all literary works may be said to imply some degree of interactivity, as indicated by classical reader response theory. However, S. makes a particular case because of the degree to which it demands active participation. For instance, Jen and Eric discover that the footnotes in The Ship of Theseus are coded messages between Straka and his translator. It is left to the readers to decode most of them. Furthermore, a so-called reading group kit has been released for the novel, including extra ephemera, colored pencils for the readers to make their own annotations in the book and even a pre-stamped postcard to write and send to one of the characters. In this way, the work encourages the readers to become active participants. In an essay, dating back from 2009, Abrams writes about his general ambition with his works: “I urge you to dig. Give in to the unknown for a while and ponder the mystery…” (2009).

The readers of S. respond to this invitation, as is indicated by the intense discussions of the work taking place on online, especially on blogs devoted to the work. In this way, the readers participate, solving the mystery about the fictional author, practicing a collective engagement in the text that resembles Eric and Jen’s mode of reading. As in Nox, we see a transition from the book as a space for intimacy, privacy – towards reading as a collective process: Eric and Jen read the text together, and the actual readers collaborate online in order to decode it.

Reading S. through the perspective of the convergence culture thus makes it possible to consider the

different levels of change in the contemporary literary culture that this work reflects: That is, change in the way that the work is produced, its narrative construction and in the way it is read. Certainly, there is a tension at stake between the work as part of contemporary media culture, where the book is only one medium among others – and, on the other hand, the celebration of media specificity, and even nostalgia for the book as a privileged space for intimacy. It displays a situation where the printed novel is challenged, however remaining culturally significant as a material tangible object. As Doug Dorst said when asked about what makes S. special: “it is the physical fact of the book itself” (interview by McCarron).

III. Remembering the Book

Both Nox and S. are characterized by a nostalgic celebration of the material book. Accordingly, both

works may be related to a recent “material turn” in contemporary culture. This turn, which has been theorized by e.g. Bill Brown and N. Katherine Hayles, implies an increasing interest in the material aspects of life, a turn towards things rather than texts. It may be, a least partly, explained as a reaction to the recent media development. Brown thus presents the material turn as a counter-reaction against what archeologist Colin Renfrew calls the “dematerialization of material culture.” Renfrew suggests that, “as the electric impulse replaces whatever is left of the material element in the images we are used to, the engagement in the material world is […] threathened […] The physical, tangible, material reality disappears” (qtd. in Brown 71).

New media are here associated with a fear of losing contact with the physical world. While this discourse may certainly be questioned, it is widespread. The new attention towards the materiality of the book may be seen as a reflection of this fear. Katherine Hayles accordingly explains the experimental texts as an expression of a “corporeal anxiety” in literature, which is related to a fear of what she describes as a posthuman situation: In the age of new media, there is a fear of losing the human, bodily aspects of life – and of losing the book as

55

the material “body” of literature.

Nox and S. both seem to reflect this situation, however they do so in different ways: Nox is primarily

nostalgic. It focuses on remembering, translating and remediating the past. By drawing on the aesthetics of the scrapbook, the book is highlighted as an intimate object of personal memory, even though it is remediated into a printed, published book. It is a monument indeed, mourning what is assumed to be absent or lost – the brother as well as the original scrapbook and the literary tradition represented by the poem.

S. similarly celebrates the book as a space of intimacy, turning the printed novel into a handwritten love story. However, at the same time, it embraces the contemporary media culture. The story escapes the book, suggesting a situation where the novel is at once celebrating the book while also moving beyond it, migrating into other, social media and turning the readers into active participants.

Both works are extreme examples. They are experiments – drawing on the tradition of avant-garde aesthetics and experimental literature, artists’ books and scrapbooks. They celebrate the aura of these rare books, the idea of the book as a unique and personal object, of intimacy and authenticity, however remediating or translating these qualities into to the very opposite of authentic. Thus, they suggest a situation where the aesthetics of avant-garde literature and of “rare books” is reproduced and projected into commercial products, “mainstream literature.”

Kiene Brillenburg Wurth has accordingly read Nox as an example of kitsch (Wurth 28). She draws on Celeste Olaquiaga’s definition of kitsch as “the attempt to repossess the experience of intensity and immediacy through an object” (291) – the object being in this case, the book. Certainly, the experiments, yellowing pages and handwritten marginalia are all there to introduce the intense experience of the book as a “present” object of the past. However, the central fact about Nox and S. is not that they are old books. Rather, they are characterized by being new books, or book objects, that look like old books. They are replicas, and they are indeed popular works, that can be bought anytime, anywhere at Amazon.com. As such, they may be read as reflections of what might be happening to the printed novel now. Albeit in an a radically experimental form, they suggest a development where the novel becomes hybrid, incorporating and working across different media while also becoming more aware of itself, of what it means to be a printed novel, and of what it means to be a book.

Cited Works

Abrams, J.J. “J.J. Abrams on the Magic of Mystery.” Wired Magazine. 20. Apr. 2009. Web. 23. Nov. 2014.

<http://archive.wired.com/techbiz/people/magazine/17-05/mf_jjessay?currentPage=all>. Abrams, J.J. and Doug Dorst. S. New York: Mulholland Books, 2013.

Abrams, J.J. and Doug Dorst. Interview by Joshua Rothman. “The Story of ‘S’: Talking with J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst.” New York Times. 23 Nov. 2013. Web. 28 Oct. 2014.

< http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2013/11/the-story-of-s-talking-with-jj-abrams-and-doug-dorst.html>.

Brown, Bill. “The Matter of Materialism. Literary mediations.” Material Powers. Cultural Studies, History

and the Material Turn. Eds. Tony Bennett and Patrick Joyce. London and New York: Routledge, 2010.

60-78.

56

Carson, Anne. Interview by Craig Morgan Teicher. “A Classical Poet, Redux: PW Profiles Anne Carson.” 29 March 2010. Web. 15. Jan. 2015. <http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/authors/interviews/ article/42582-a-classical-poet-redux-pw-profiles-anne-carson.html>.

Dorst, Doug. Interview by Meghan McCarron. “It’s the Physical Fact of the Book itself.” Buzz Feed Books. 8. Jan. 2014. Web. 6. Nov. 2014. <http://www.buzzfeed.com/meghanmccarron/doug-dorst>.

Gumbrecht, Hans Ulrich. The Production of Presence. What Meaning Cannot Convey. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004.

Hayles, N. Katherine. “The Future of Literature: Complex Surfaces of Electronic Texts and Print Books.” The

Changing Book: Transitions in Design, Production and Preservation. Eds. Nancy E. Kraft and Holly

Martin Huffman. The Haworth Press, Inc. 2006.

Hayles, N. Katherine. Electronic Literature. Notre Dame; Notre Dame University Press, 2008

Jenkins, Henry: Convergence Culture. Where Old and New Media Collide. New York and London: New York UP. 2006.

Olaquiaga, Celeste. The Artificial Kingdom. On the Kitsch Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Panko, Julia. “‘Memory Pressed Flat into Text’: The Importance of Print in Steven Hall’s The Raw Shark

Texts.” Contemporary Literature. 52, 2 (2011): 264-297.

Pressman, Jessica. “The Aesthetics of Bookishness in Twenty-First-Century Literature.” Bookishness: The

New Fate of Reading in the Digital Age. Spec. Issue of Michigan Quarterly Review 48 (2009). Web. 28.

Oct. 2014. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.act2080.0048.402 >.

Tanderup, Sara. “Intermedial Strategies in Two Contemporary Novels.” Kunstlicht, vol. 36, no. 1, 2015. Tanderup, Sara. Bits of Books in Boxes. Remembering the Book in Anne Carson’s Nox and Mette Hegnhøj’s

Ella is my name do you want to buy it”. Media and Memory (Text, Action, Space 3). Eds. Lars Sætre,

Patrizia Lombardo and Sara Tanderup. Forthcoming 2016.

Tanderup, Sara: “’A Scrapbook of you + me.’ Bookish Nostalgia in J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst’s S.” Orbis

Litterarum. Forthcoming.

Ware, Chris. Building Stories. New York: Pantheon Books, 2012.

Wurth, Kiene Brillenburg. ”Re-vision as Remediation. Hypermediacy and Translation in Anne Carson’s Nox.”

Image & Narrative. 14.4 (2013): 20-33.

Sara Tanderup is a PhD student in Comparative Literature at Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark. She is

currently working on her dissertation “’Something to hold on to…’ Representing Memory and Remembering Literature in Intermedial, Literary Works” (working title). She is a member of the research project “Center for Literature between Media” (2012-2017) and has published various articles in Danish and international journals such as Passage, K&K, Orbis Litterarum and CLCweb: Comparative Literature and Culture.