Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 176

Time, extended: Hiroshi Sugimoto with Gilles Deleuze

Mirjam Wittmann

Abstract: How can one think time in the photographic image? In the history of modern

photography the photograph has been seen as a static object, a frozen moment of time. With

the emergence of the beholder past is being changed into present and vice versa. In his

“Seascapes” series the artist Hiroshi Sugimoto exceeds the traditional concepts of time and

reveals instead its intangibility and its character of transgression. French philosopher Gilles

Deleuze gives an idea how to think time in its fleeting and shimmering evanescence that runs

counter to prevailing conceptions of photography‟s relationship to instantaneity and to the

photographic image as the record of a brief and transitory moment in time.

Résumé: Comment penser le temps dans l‟image photographique? Dans l‟histoire de la

photographie moderne, la photographie a été définie comme un objet statique, un moment figé

dans le cours du temps. Depuis qu‟on s‟intéresse davantage à l‟apport du spectateur, on est

devenu attentif aux chassés-croisés entre le passé de la représentation et le présent du regard.

Dans ses « Seascapes », Hiroshi Sugimoto dépasse les idées traditionnelles du temps pour

dévoiler son caractère intangible et transgressif. Ces aspects-là du temps peuvent être pensés à

l‟aide de la philosophie de Gilles Deleuze, qui insiste sur le caractère fluide et évanescent du

temps. Une telle approche rompt avec les idées courantes sur les rapports entre photographie

et instantané et sur l‟image photographique comme représentation d‟un fragment temporel.

Keywords:Hiroshi Sugimoto, Gilles Deleuze, time as transgression, time explosion, floating

time, crystal image, photographic myth, embodiment of memory, desire, weakening of

representation, performative gesture.

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 177 I. Time and the photographic image

The relationship between time and the photographic image has been traditionally seen in many various ways: as narration in the image, as the process between the beholder and the image, or as time that is related to the construction of the image. Throughout the history of modern theory of photography there has been a consensus that the photograph has been a static object, a frozen moment in time. A photograph that has been taken in the past, is a brief and short moment of time that is necessarily regarded as one of its decisive characteristics. That is why Siegfried Kracauers well known book Theory of Film turns nowadays out to be almost conventional – in regards to contemporary philosophy of time. While looking for theoretical distinctions between film and photography he describes the former as a series of movement and the latter as a cut into time. Film is being regarded as a sequence of movement, therefore more able to achieve a higher synthesis of life as it “represents reality as it evolves in time” (Kracauer 1960, p. 41), while photography is “essentially associated with the moment of time at which it came into existence” (Kracauer 1960, p. 19). What can be remarked as a first aspect is that compared to photography film has a different pictorial mediation between past and presence. How can we depict such a relation?

The focus on the conditions of production as the mediums specificity has been significant for a long time in order to distinct between these two mediums until the position of the beholder began to disturb modal temporality. It is through the beholder that past becomes to be present and through the beholder the relationship between past and present began to loose his formal boundaries. The question now is: What does the emergence of the beholder as a condition for the image mean for the image‟s temporality? What needs to be changed regarding traditional time models that measure and count time in minutes and seconds? Is instantaneity as a category of photography still useful for the understanding of a photographic image? And how can one think time in the photographic image?

Augustinus, when he was asked: What is time? Answered: If nobody asks me for it, I know it; if I want to explain it to someone asking, I do not know it. What Augustinus said a long time ago is still at stake when we are trying to describe that phenomenon in the 21 st century. Australian philosopher Elisabeth Grosz emphasized the gap between the phenomenon and its verbal description in the following citation: »Time is one of the assumed yet irreducible terms of all discourse, knowledge, and social practice. Yet it is rarely analyzed or self-consciously discussed in its own terms. [...] Time has a quality of intangibility, a fleeting half-life, emitting its duration-particles only in the passing or transformation of objects and events, thus erasing itself as such while it opens itself to movement and change. It has an evanescence, a fleeting or shimmering, highly precarious „identity‟

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 178 that resists concretization, indication or direct representation. Time is more intangible than any other „thing‟, less able to be grasped, conceptually or physically.« (Grosz 1999, p.1)

One could argue, that we are nonetheless able to tell what time is when we look at the large history of astronomy or the invention of clocks that measure time in minutes and seconds. But do they not just attempt to control time, and are they not just an instrument for us to store it? What is missing it the irreducible affection that it has on us? But how should we reflect the distance that is incorporated in time? Mere astraction or metasphysical construction is not able to consider our aesthetic experience with time?

The fluctuate character or „passing through“ was one of the points of interests why Gilles Deleuze, following Henri Bergson, began to rethink the phenomenon. He noticed that there has been a revival of thinking time when new technologies such as film enter the world. Starting from various film examples Deleuze thought time as simultaneity, focused on the notion of growing time. Time in the cinematic image is being regarded as simultaneity of past and present, being virtual and actual at the same time. The films of the Nouvelle Vague inspired him to think time as becoming and not as being. He turns the weakening of traditional modal temporality into a kind of time explosion where time is trembling and systems of references or orientations are missing. The ungraspability needs to be seen outside of spatiotemporal coordinates. Without these orientations time is constantly in a state of crudity. In terms of moving images time becomes visible as a generic principle. In the following we should ask, if in Deleuze‟s writings, which are undoubtly connected to film theory, there are also connection points with photography? Can photography - traditionally attached to the moment of time at which it came into existence - be connected to time in its pure state?

Under the conditions of some aspects of the Deleuzian idea of time we will see that many ideas of photographic time are dominated by traditional conceptions of time, what I will show in the second part of my article. In the third part a series of photographs by Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto evokes a sense of time that is floating constantly between reception and production and provokes an understanding of time as event. Sugimoto‟s photograph tend to priviledge the notion of bifurcation and indiscernibility between the actual and virtual in Deleuze‟s chrystal image. In revealing time also as growing time the artist undermines the notion of the photograph as a frozen moment of time and transcends the dialectic form of relatedness to the world. Instead these photographs raise the complex question of the relation between the functioning of time and the image which go beyond traditional temporality and thus highlight fundamental qualities of photography.

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 179 II. The photographic paradox in time

In looking at a fictitious photography of his mother, Roland Barthes becomes aware of another paradoxical quality of time. „Time is engorged“, it contains an „enigmatic point of inactuality, a strange stasis, the stasis of an arrest“ (Barthes 1981, p. 91), which is to be conceived as an anthropological constant. This happens in two ways: on the one hand, Barthes thinks of the photo as tearing through time, as tearing a moment from the continous stream of time. On the other hand, it foreshadows his own death. In freezing the life of the portrayed, the photograph reminds the beholder of his own death to come. The specific temporality of futurum II becomes symbolically manifest in a photo by Alexander Gardner depicting Lewis Payne shortly before his execution. What strikes Barthes is the fact that the photograph combines the moment when it was taken, i.e. an event in the past, with an event which will occur in the future. „That is dead and that is going to die“ (Barthes 1981, p. 96), he realizes in a sudden shock which brings to his mind the unavoidability of his own death. Despite the evidently paradoxical structure of photographic temporality Barthes seems to be influenced by traditional, i.e. modal conceptions of time. Past, present and future become intertwined in the futurum II in a way which gives them a tendency towards temporal inattainability.

We can find a similar argument in Philippe Dubois‟ book L’acte photographique et autres eassais who brings up the often stressed subject of photography as a cut in time. He is one of the authors who tries to regard both the production and the reception of images at the same time. In describing the often heard cut in time as a paradoxical phenomenon Dubois isolates a moment of deprivation that is all the more necessary for an image‟s time structure as I will show in the following part.

Although being taken in a decisive moment of time, instantaneity remains paradox, as Philippe Dubois claims. The cut through time and space turns out to be less a cut of continuity but is in itself discontinuous. He argues: “L‟acte photographique coupe, l‟obturateur guillotine la durée, il installe une sorte de hors-temps (hors-course, hors-concours). (…) Cette photo ne me restitue pas la mémoire d‟un parcours temporal mais plutôt la mémoire d‟une experience de coupure radicale de la continuité, coupure qui fonde l‟acte photographique lui-même.” (Dubois 1990, p. 156f.) The often heard cut in time is based on the side of the production of the image. In contrast to painters, the photographer has to make just one decision: everything focuses on the moment of exposure, that moment, where the image is made without the intervention of the human being. The photograph is hence taken, in a tenth of a second, and is said to be constitutive for the image‟s ontology.

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 180 But Dubois marks another paradox situation in the photographic image. After having analyzed the process of production, he turns towards another decisive moment, when time goes beyond instantaneity. The paradoxical situation of time in the photographic image consists in a temporal movement, when the grabbed instant exceeds into duration. Past things are being received into present and this is where the beholder‟s place becomes a constitutive condition of the photograph‟s temporality. “L‟acte photographique implique donc non seulement un geste de coupure dans la continuité du reel mais aussi l‟idée d‟un passage, d‟un franchissement irreducible.” (Dubois 1990, p. 160)

Two structural levels are overlapping here. Only if the esthetic experience of the beholder and the production process of photography are separated one from another, time can be understood as transgression. Although Dubois marks a decisive point regarding the image‟s temporality as an experience of transgression, the condition of time is all the more based on conventional modal concept of temporality. And although he is able to connect the quoted intangibility inherent in time with the paradox of photographic time Dubois priviledges as well as Barthes do their inspiring ideas of time based on conventional conceptions of time.

III. Time, extended

In order to pursue this idea we should ask for the structure of time as an experience of transgression. What comes immediately to ones mind is Gilles Deleuze‟s paraphrase of Marcel Prousts “Time in the pure state” as a model for time as transgression.

Behind this term lies Deleuze‟s reading of Prousts Time regained when he describes: “But let a noise or a scent, once heard or once smelt again in the present and at the same time in the past, real without being actual, ideal without being abstract, and immediately the permanent and habitually concealed essence of things is liberated and out true self, which seemed – had perhaps for a long time seemed – to be dead but was not altogether dead, is awakened and reanimated as it receives the celestial nourishment that is brought to it.” (Proust 1996, p. 57) What is important to remark is that we are not dealing with simple remembering of a moment that is past but was once present. Gilles Deleuze puts it in another order: memorized things are real, because we experience them (in the present) and they are ideal because they are not bound to materiality. Such a concept allows Deleuze to think an image of being virtual and actual at the same time, it enables him to conceive an image of time as a series of simultaneous paths of bifurcations between the “actual” and the “virtual”. We could

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 181 sum up that the time-image is one that fluctuates constantly between actual and virtual and records memory. In this image mental time is physical and vice versa. In order to name this philosophical construction Deleuze created the term crystal-image which he illustrates with various films of Alain Resnais, Orson Welles, Max Ophuls and others. How should we now understand the relation between the crystal image and photography?

IV. Photographs, revealing time

It seems as if Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto has visualized the term crystal-image. One might argue that there is no direct link between the French philosopher who addressed his thoughts to film and the Japanese photographer. But it is actually Sugimoto himself who allows me to think this connection when he became aware of his cultural roots when he moved to L.A. in the beginning of 1970. The special distance was necessary for him to become again aware of his own asian roots. Insofar we can at least legitimate our approach to Sugimoto from a western point of view. In addition to that Sugimoto was highly interested in phenomenology that has been studied by the artists in the 60s and gave at least minimal art some theoretical basement.

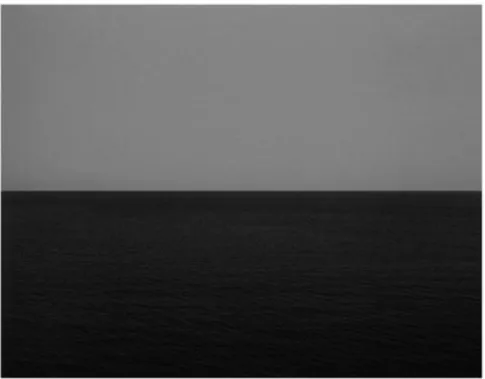

Fig. 1: Exhibition view, Hiroshi Sugimoto at K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf, 14.7.2007 – 06.01.2008

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 182 In 1980 the artist started his series Seascape series which is an ongoing process of work until now (fig.1). Time enters into the subtle play between opposites, between stillness and time. In each photograph the oscillation between change and stasis, clarity and fog, detail and totality, transparency and opacity becomes obvious, creating an atmosphere of meditation and flotation, which the artist calls "time exposed." (fig. 2)

Fig. 2: Hiroshi Sugimoto, Caribbean Sea, Jamaica, 1980, Gelatinesilverprint, 119,4 x 149,2 cm, private ownership, © Hiroshi Sugimoto

There are clear seascapes, in which precise and accurate horizons divide bright, blank skies from dark-flecked water, where smooth sunpaths appear in terms of thin wave-lines on the water, as you can see in Caribbean Sea, Jamaica from 1980. Whereas in Aegean Sea, Pilion (fig. 3) from 1990 there are foggy seascapes, where sky and sea are merged atmospherically, with horizons blurred or nonexistent, the structures of the waves completely disappeared.

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 183 Fig. 3: Hiroshi Sugimoto, Aegean Sea, Pilion, 1990,

119,4 x 149,2 cm, Gelatinesilverprint, private ownership, © Hiroshi Sugimoto

An atmosphere between sunrise and sunset, never knowing where the light comes from nor upon what it points. And there are seascapes such as Marmara Sea from 1991, in which sky, water, waves, and horizons lose their own formal boundaries and merge into slight degrees of black and grey. (fig. 4)

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 184 Fig. 4: Hiroshi Sugimoto, Marmara Sea, Silivri, 1991,

119,4 x 149,2 cm, Gelatinesilverprint, private ownership, © Hiroshi Sugimoto

Amidst blurred dark water and brilliant sky and vice versa, Sugimoto highlights a misty, picturesque ambience, as if an impressionist painter such as Monet had been given the camera to fix the transient changes of light in contemporary photographic vision.

Time began to float around, to move both in a linear timeline, through the moments captured in each single frame, and horizontally, across different images- until the series as a whole could be read as a movie in which all events registered simultaneously. The first link to Deleuze lies in the transcendence of floating time. It is not captured in a single print, but in the spaces in-between. Time enters the spaces in-between, and extends towards the frame of the single images. What becomes obvious is the permanent disappearance of time in forms of missing objects and missing link to concrete space and time. Even the day oder nightscapes provoque an oscillating atmosphere which lets the beholder stay in the mood of uncertitude and unstableness (fig. 4).

This illusion of narrative structure is reinforced by the titles. Undoubtedly one could ignore them, but most people, when confronted with a picture, want to know what it depicts. The representational character remains present only in the titles whereas the material object denies locating

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 185 the photographed object. The representational demand of photography is at the same time made unmasked and annihilated as it exposes it as a simple illusion with far-reaching consequences.

But photographs are not just simply phantasmatic. If photographs were mere fantasies of light and shadow, captions would just be phantoms of real information. It seems, as if Sugimoto wished to make visible this aspect of his work. He could also have called his images "Untitled Seascape", but he did not. The naming words in the titles animate to resonate. Regarding concrete titles as “Rebun Island, Rügen, Aegean Sea, Cascade River,” etc. Sugimoto reinforces our desire for denotation and creates a moment of deprivation knowing that it can never be redeemed.

Again in order to link again Deleuze here we could argue that the philosopher created new terms such as the crystal-image as a reaction to the inconvenience of traditional verbal systems. He created the term to express his idea of an image outside of traditional verbal denotation. Sugimoto resists in the same way to traditional denotation when he gives more value to visual appearance. He is not so much concerned of documentation of the seas but of revealing specific photographic qualities. To make this idea clear, it is interesting to see what Sugimoto said about the desire to do this series:

“ I was near asleep when I had a very clear vision: the idea of a very accurate horizon, a completely still seascape with a bright, cloudless sky. The horizon was in the very center of the image. This vision is rooted in my childhood: I remember the first time I saw the sea. I was born in Tokio and, as you know, Tokio is situated next to the sea. Every Japanese wants to see the Fuji, but I was attracted to the ocean. I liked this image and started to think about a new series. I thought of my ancestors who looked at the sea and gave it its name. To name something means to be self-aware, to be able to distinguish oneself from the world. Language stems from this human need to communicate with the world. Without language the boundaries between the inner and outer worlds would not be obvious. While working on the seascape series, I thought about the oldest impressions of human beings, about the time when the first human beings gave names to the world around them, the sea.“ (translated by M.W. from the german translation, quoted in: Sugimoto 1994, p.95)

As one can clearly remark, Sugimoto attaches much importance to the creation of myths, his own romantic ideas and philosophy. In both, in his own history and the history of the human beings, he went back to the roots and touches consequently topics like denotation, early times and memory.

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 186 The same desire brings him back to a deep reflection on photographic qualities. We could think now that taking a picture is equivalent to naming the world. In the same way that he wants us to see sheer oceans as the origin of our world, he confronts us with our own desire to capture the world to make it stable. As a photograph denies in itself a complete understanding in language, it is open for suggestions, for dreams and interpretation. The act of going back to our roots is linked to memory as a common interpretation of Sugimoto‟s images.

I would underline here what Hans Belting said in his reflections on this series, that the artist “undermines our belief in the indexicality of time” (Belting 2005, p. 160) Although a photograph captures a single moment of time and fixes it on paper, Sugimoto reinforces time as duration and and makes you feel as if time stands still and moves on at the same time. As Thierry de Duve pointed out, time is not a model, not comprehensible as a logic or metaphysic paradigm. Time is always a “before” and “after, but also an “not yet” and “not any-more”: “It is the sudden vanishing of the present tense, splitting into the contradiction of being simultaneously too late and too early, that is properly unbearable.” (Thierry de Duve 1978, p.121) This idea points all the more towards an understanding of lateral time, existing one and another at the same time, being virtual and actual at the same time. This understanding points again towards the Deleuzian understanding of time.

Instantaneity has being changed into a stream of time as if Sugimoto had infiltrated Henri Bergson‟s idea of duration as existential form of our life who would become significant for Deleuze‟s conception of the time-image.

Bergson started his career in reaction against “scientific notion of time” and embarked on a path involving phenomenological mode of adhesion to immediate experience. He denounced an increase of awareness of the inadequacy of clock-time as time-measurer and resisted a materialistic and positivistic view on the world. If we understand the permanent insistence in duration as a critic of rational and verbal denotation, we become aware of Bergson‟s interest to go beyond the system of words that dominate our conscience (as one possible characterization of duration). In the same way as we denote things and ideas in words, the verbal system marks at the bottom a fundamental difference to how the world is given to us. It also denies a phenomenological character of things that Bergson wants to dig out.

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 187 That is why he puts so much emphasis on the term duration as it goes beyond all kinds of denotation. Differences separate things and also modal distinctions such as past, present and future and arrange them in a virtual logical space. In the perception of our conscience these categories don‟t exist and past is not past, but kept into future. Bergson says: “But to touch the reality of the spirit we must place ourselves at the point where an individual consciousness, continuing and retaining the past in a present enriched by it, thus escapes the law of necessity, the law which ordains that the past shall ever follow itself in a present which merely repeats it in another form and that all things shall ever be flowing away.” (Bergson 2004, p. 313) The link between duration and memory becomes significant in his famous book Matière et Memoires from 1896. As preserved duration memory stores experiences and keeps them alive.

This is, where Gilles Deleuze started to rethink the term “preserve” and connected his idea of an image being virtual and actual at the same time.

It seems as if Sugimoto has visualized what Bergson and Deleuze wrote about time and memory. The photographic image in Sugimoto‟s work becomes the embodiment of memory. The inscription of time becomes visible as incarnation in the photographic images through denying a representational character. Sugimoto transfers the stored time of photography into a reflection on memory. Time is filled with aura and enters the beholder‟s memory. The sea as one of the origins of the world points to the memory of the world, in what we find the sources of our lives. And at the same time a photograph is one of our tools to name the world and make it stable.

Beside a deep reflection on time and memory Sugimotos Series reflects the potential of photography. In denying the representational character Sugimoto reinforces photographic qualities like conservation. We remember that we remember time in photographic images. Time becomes visible not as a solely and frozen moment but as a symbol of stored time, as memory (gespeicherte Zeit).

Bergson on his part sees that our word “memory” mixes together two different kinds of memories. On the one hand, there is habit-memory, which consists in obtaining certain automatic behavior by means of repetition; in other words, it coincides with the acquisition of sensori-motor mechanisms. On the other hand, there is true or “pure” memory; it is the survival of personal memories, a survival that, for Bergson, is unconscious. In other words, we have habit-memory actually aligned with bodily perception. Pure memory is something else, which is related to the unconscious

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 188 and therefore unable to be designated or denotated. But that is exactly what happens in Sugimotos Seascapes: they unmask, as do Bergson and Deleuze, the human desire to designate things and go beyond the desire for formalisation and denotation. In weakening the representational caracter of his images Sugimoto makes them a pointing gesture to something that cannot be named and is therefore more a reference to a virtual memory than a reference to a single object.

The image seduces the beholder to believe in its representational qualities but never redeems it. In order to create this illusion Sugimoto makes much out of the fact that photography‟s mediality becomes transparent. He makes much out of the fact that the grain becomes invisible, to eliminate the material appearance of the medium.

„I want people to look at my work twice– from a distance and from a close point of view. In large format photography one easily sees the grain. The water for example looks like an agglomeration of dots, and this is where the image ends. Everything consists of dots. With the format I use -8 by10 inch-, people can come very close and study the waves without seeing the grain. I want the beholder to be drawn into my images.“ (translated from the german translation, quoted in: Sugimoto 1994, p. 95)

This antinomic experience, namely the confrontation between the beholder‟s time based memory and the denial of the denotative character of the index turns time in Sugimoto‟s images into floating time. Time flows through the images. In stressing this flow of time the artist runs counter to prevailing conceptions of photography‟s relationship to instantaneity and to the photographic image as the record of a brief and transitory moment in time. For here in this series, the photographs are in contrast the embodiment of the Deleuzian time-image or crystal image which exceeds the traditional concept of time and faces us through images instead in the intangibility that cannot be seen without the experience of the viewer. As for the medium‟s specificity we could finally ask if the distinction between film and photography, between the still and the moving image, that have dominated the debates of both until recently, become blurred.

This turns once again photography into a moving image. If we insist on the term transgression, it can also be understood as time-movement as a kind of happening or performative gesture. And this kind of time as ongoing phenomenon can never be captured or measured in minutes and seconds. This

Image & Narrative , Vol 10, No 1 (2009) 189 sense of the extension of time as constitutive of both the means of production and mode of perception of the photograph is all the more significant in Sugimoto‟s images.

Bibliography

Barthes 1981 - Roland Barthes: Camera Lucida. Reflections on Photography (1980), translated by Richard Howard, New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

Belting 2005 - Hans Belting: "Hiroshi Sugimotos Kinosäle und der unsichtbare Film" in: Hans Belting / Peter Weibel (ed.): Szenarien der Moderne. Kunst und ihre offenen Grenzen. Berlin: Philo & Philo Fine Arts 2005, p. 154-168

Bergson 2004 - Henri Bergson: Matter and Memory (1896) , translated by Nancy Margaret Paul, W. S. Palmer, published by Courier Dover Publications, 2004

De Duve 1978 - Thierry de Duve: „Time Exposure and Snapshot: The Photograph as Paradox“, in: October, Vol. 5, Summer 1978, p. 113-125

Dubois 1990 – Philippe Dubois: L’acte photographique et autres essais, Bruxelles: Editions Labor, 1990

Grosz 1999 – Elisbeth Grosz (ed.): Becomings. Explorations in Time, Memory and Futures, Cornell University Press 1999

Kracauer 1960 - Siegfried Kracauer, Theory of film: The Redemption of Physical Reality, Oxford University Press, 1960

Proust 1996 - Marcel Proust, Time Regained, translated by Terence Kilmartin and Andreas Mayor, London: Vintage, 1996

Sugimoto 1994 - Hiroshi Sugimoto in an interview with Thomas Kellein, in: Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time exposed, ed. by Hiroshi Sugimoto, Thomas Kellein, Kunsthalle Basel, published by H. Mayer, 1995. p.91-96

Mirjam Wittmann studied philosophy and history of art at the Universities of Berlin and Barcelona. Since october 2006 she is participating in a three year scholarship with the graduate program „Image-Body-Medium - an Anthropological Perspective“ at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Karlsruhe, Germany. She is currently writing on her PhD „Photography between index and event“ at the University of Basel.