Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

131

[415

*1

'. k'U-Vtk.[

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

Does

Air

Quality

Matter?

Evidence from

the

Housing

Market

Kenneth

Y.

Chay

Michael Greenstone

Working

Paper

04-1

9

February

2004

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

This

paper

canbe

downloaded

without charge fromtheSocial Science

Research Network Paper

Collection atMASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTEOF

TECHNOLOGY

MAY

1 8 2004DOES

AIR

QUALITY

MATTER?

EVIDENCE

FROM

THE

HOUSING

MARKET*

Kenneth

Y.Chay

UniversityofCaliforniaatBerkeley and

NBER

Michael GreenstoneMIT,

American Bar

Foundation, andNBER

February

2004

*

We

thank countless colleagues and seminar participants for very helpfulcomments

and suggestions.Justine Hastings,

Mark

Rodini, and Pablo Ibarraran provided excellentresearch assistance. Greenstonereceived funding

from

the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Resources for the Future.Chay

received supportfrom

the Instituteof

Business andEconomic

Research, the Institute ofIndustrial Relations, andan

UC-Berkeley

faculty grant.Funding

fromNSF

Grant No.SBR-9730212

is also gratefullyDOES

AIR

QUALITY

MATTER?

EVIDENCE

FROM

THE

HOUSING

MARKET

ABSTRACT

We

exploit the structure ofthe Clean AirAct

to providenew

evidenceon

the capitalization oftotalsuspended particulates (TSPs) air pollution into housing values. This legislation imposes strict

regulations

on

polluters in "nonattainment" counties,which

are definedby

TSPs

concentrations thatexceed a federally set ceiling.

TSPs

nonattainment status is associated with large reductions inTSPs

pollution

and

increases in county-level housing prices.When

nonattainment status is used as an instrumental variable for TSPs,we

find that the elasticity of housing values with respect to particulatesconcentrationsrange

from

-0.20 to -0.35.These

estimatesofthe averagemarginal willingness-to-payforclean air are far less sensitive to

model

specification than cross-sectional and fixed effects estimates,which

occasionally havethe "perverse" sign.We

also findmodest

evidencethatthe marginal benefitofpollution reductions is lower in

communities

with relatively high pollution levels,which

is consistentwithpreference-based sorting. Overall, the

improvements

in airquality inducedby

themid-1970s

TSPs

nonattainment designation are associated with a $45 billion aggregate increase in housing values in

nonattainmentcounties

between

1970and 1980.Kenneth Y.

Chay

Department

ofEconomics

UniversityofCalifornia, Berkeley

549 Evans

Hall Berkeley,CA

94720

andNBER

kenchay@econ.berkeley.edu Michael GreenstoneDepartment

ofEconomics

MIT

50

Memorial

Drive,E52-391B

Cambridge,

MA

02142-1347

American Bar

Foundationand

NBER

Introduction

Federal airpollution regulationshave

been

among

themost

controversial interventionsmandated

by

the U.S. government.Much

ofthis controversy is generatedby

an absence of convincing empiricalevidence

on

theircosts and benefits. Thus, the credible estimation oftheeconomic

value ofcleanairtoindividualsis animportanttopic tobothpolicy

makers

andeconomists.The

hedonic approach to estimating theeconomic

benefits ofairqualityuses the housing markettoinfertheimplicitprice functionforthis

non-market

amenity. Here, researchers estimatetheassociationbetween

property values and air pollution, usuallymeasured

by

total suspended particulates (TSPs),regression-adjusted fordifferences across locations inobservable characteristics. After over

30

years ofresearch, the cross-sectional correlation

between

housing prices and particulates pollutionappears weak.A

meta-analysisof 37 cross-sectional studiessuggests that a1-ug/m

3 decrease inTSPs

results ina0.05-0.10%

increase inpropertyvalues,which

impliesonlya -0.04to-0.07elasticity(Smith andHuang

1995).As

a result,many

conclude that either individuals place a small valueon

air quality or the hedonicapproach cannot produce reliable estimates of the marginal willingness-to-pay

(MWTP)

forenvironmentalamenities.

These

weak

resultsmay

be

explainedby two

econometric identification problems that couldplague the implementation ofthe hedonic method. First, itis likely that the estimatedhousingprice-air

pollution gradient is severely biased due to omitted variables.

We

show

that the "conventional"cross-sectional

and

fixedeffects approachesproduceestimatesofMWTP

thatarevery sensitive to specificationandoccasionallyhavethe perversesign, indicatingthat

TSPs

and housingpricesare positively correlated.Second

ifthere is heterogeneity across individuals in tastes forclean air,then individualsmay

self-selectinto locationsbased

on

these unobserveddifferences. In this case, estimatesofMWTP

may

only reflect thepreferencesofsubpopulationsthat, forexample,placea relativelylow

valuation onairquality.This paper exploits the structure ofthe Clean Air

Act

Amendments

(CAAAs)

to providenew

evidence

on

the capitalization ofair quality into housing values.The

CAAAs

marked

an unprecedentedattempt

by

the federalgovernment

tomandate

lowerlevelsofairpollution. Ifpollution concentrationsindesignates the county as 'nonattainment'. Polluters in nonattainment counties face

much

greaterregulatory oversight than theircounterparts inattainmentcounties.

We

use nonattainment status as an instrumental variable forTSPs

changes in first-differencedequations forthe 1970-1980 changein county-levelhousingprices.

The

instrumental variables estimatesindicate that the elasticityof housing valueswith respect to particulates concentrations range

from

-0.20to -0.35. Estimates

from

arandom

coefficientsmodel

that allows fornonrandom

sorting provideevidenceconsistentwiththe self-selectionofindividualsacrosscountiesbased

on

tasteheterogeneity andsuggest that the marginal benefit ofa pollution reduction

may

be lower in communities with relativelyhigh pollution levels.

However,

the self-selection bias in estimates oftheaverageMWTP

appearsto besmallrelative totheinfluenceofomittedvariables.

The

"reduced form" relationshipsbetween

the instrument and changes inTSPs

and

housingprices provide direct estimates of the benefits ofthe nonattainment designation.

We

find thatTSPs

declined

by

roughly 10ug/m

3(12%)

more

in nonattainment than attainmentcounties. Further, the datarevealsthathousingpricesrose

by

approximately2.5% more

inthese counties.Our

estimates ofthe averageMWTP

for clean air are far less sensitive to specification than thecross-sectional and fixed effects estimates. For example,

we

find evidence thatnonattainment status isuncorrected with virtually all other observable determinants of changes in housing prices, including

economic

shocks. Thus, it is not surprising that our results are largely insensitive to the choice ofcontrols.

The

discrete relationshipbetween

regulatory status and the previous year's pollution levelsprovide

two

opportunities to gauge the credibility ofourresults. In particular, the structure ofthe rulethat determines nonattainment status ensures that there are nonattainment and attainment counties with

identical and almost identical average

TSPs

levels in the regulation selection year. This allows us toimplement

"matching" and quasi-experimental regression discontinuity validation tests.Both

ofthesetests confirm the reduced form results and our basic finding of an importantrelationship

between

TSPs

The

analysis is conducted with themost

detailed and comprehensive data availableon

pollutionlevels,

EPA

regulations, and housingvalues atthe county-level.Through

aFreedom

of InformationAct

request,

we

obtained annual airpollution concentrations for each county basedon

the universe of stateand

national pollution monitors.These

dataareusedtomeasure

counties' prevailingTSPs

concentrationsand

nonattainmentstatus.We

usetheCounty

and

CityData Books

data file,which

islargelybasedon

the1970

and 1980 Censuses,toobtainmeasures of housingvaluesand housing and countycharacteristics.Overall,the timingand location ofthe changesin

TSPs

concentrationsand

housing values inthedecade

from

1970 to 1980 provide evidence thatTSPs

may

have

a causal impacton

property values.Taken

literally, our estimates indicate that theimprovements

in air quality inducedby

themid-1970s

TSPs

nonattainmentdesignationareassociatedwith a $45 billionaggregate increase inhousing values innonattainment counties duringthis decade.

The

results also demonstratethatthe hedonicmethod

canbesuccessfully appliedincertaincontexts.

I.

The Hedonic

Method

and

Econometric

IdentificationProblems

An

explicitmarket forclean airdoes notexist.The

hedonic pricemethod

iscommonly

usedtoestimatethe

economic

value ofthisnon-market amenityto individuals.1 Itisbasedon

the insight that theutility associatedwiththe consumption ofadifferentiatedproduct, suchas housing, is determined

by

theutility associated with the individual characteristics ofthe good. For example, hedonic theory predicts

that an

economic

bad, suchas airpollution, willbe negatively correlatedwithhousing prices,holding allothercharacteristics constant. Here,

we

review themethod and

the econometric identification problemsassociatedwith its implementation.

A.

The

Hedonic

Method

Economists have estimatedtheassociation

between

housingpricesand airpollutionat leastsinceRidker (1967) and Ridker and

Henning

(1967).However,

Rosen

(1974)was

the first to give this1

Other methods for non-market amenity valuation include contingent valuation, conjoint analysis, and discrete

correlation an

economic

interpretation. In theRosen

model, adifferentiatedgood

can be describedby

avector ofitscharacteristics,

Q

=

(qi, q2,..., qn). In the caseofahouse, thesecharacteristics

may

includestructural attributes(e.g.,

number

of bedrooms), theprovisionof neighborhoodpublic services(e.g., localschool quality),andlocalamenities(e.g., airquality). Thus, thepriceofthei

th

house can be writtenas:

(1)

P

i=

P(q1,q2,...,qn).The

partial derivative ofP(») withrespect tothen

th characteristic, 5P/dqn, is referred to as the marginalimplicit price. Itisthemarginalpriceofthe

n

th characteristic implicit inthe overall priceofthehouse. In a competitive market the housing price-housing characteristic locus, or the hedonic priceschedule (HPS), is determined

by

the equilibriuminteractionsofconsumers

andproducers.2The

HPS

isthe locusoftangencies

between

consumers' bid functions and suppliers' offerfunctions.The

gradientofthe implicit price function with respect to air pollution gives the equilibrium differential that allocates

individualsacross locationsand compensatesthose

who

face higherpollution levels. Locationswith poorairquality

must

have lower housing prices inorderto attractpotentialhomeowners.

Thus, at eachpointon

theHPS,

the marginal price ofahousing characteristic is equal to anindividual consumer's marginalwillingnessto

pay

(MWTP)

for that characteristic andan individualsupplier'smarginalcost of producingit. Since the

HPS

reveals theMWTP

at a given point, it can be used to infer the welfare effects ofamarginalchangeinacharacteristic fora givenindividual.

In principle, the hedonic

method

can also be used to recover the entiredemand

orMWTP

function.3 This

would

be oftremendous practical importance,because itwould

allow forthe estimationofthewelfare effects of nonmarginal changes.

Rosen

(1974)proposed a 2-stepapproach for estimatingthe

MWTP

function, aswellasthe supplycurve.4 Insome

recentwork, Ekeland,Heckman

and

Nesheim

(2004) outline the assumptions necessary to identify the

demand

(and supply) functions in an additive-SeeRosen

(1974), Freeman(1993),andPalmquist (1991) fordetails.

3

Epple and Sieg (1999) develop an alternative approach to value local public goods. Sieg, Smith, Banzhaf, and

Walsh (2000) applythis locational equilibriumapproach to value air quality changes in Southern California from

1990-1995.

4

Brown

andRosen(1982), Bartik (1987),and Epple(1987)highlight thestrongassumptionsnecessaryto identifythe structuralparameterswiththisapproach. Thereisaconsensusthatempiricalapplicationshavenotidentified a

situationwheretheseassumptions holdandthatthesecondstage

MWTP

functionforanenvironmentalamenityhasversion ofthe hedonic

model

with datafrom

a single market.The

estimation details are explored infurtherwork.5

B.

Econometric

IdentificationProblems

This paper's goal is to estimate the hedonic price function for clean air and empirically assess

whether housing prices rise with air quality. In

some

respects, this is less ambitious than efforts toestimate primitive preference parameters and, in turn,

MWTP

functions.However

from

a practical perspective, it is ofat least equal importance, because the consistent estimation ofequation (1) is thefoundation

upon which any

welfare calculation rests. This is because the welfare effects ofa marginalchange in air quality are obtained directly

from

theHPS.

Further, an inconsistentHPS

will lead to aninconsistent

MWTP

function, invalidating any welfare analysis of non-marginal changes, regardless ofthe

method

usedtorecover preference ortechnologyparameters.Consistent estimation of the

HPS

in equation (1) is extremely difficult since theremay

be

unobserved factors that covary with both air pollution and housing prices.6 For example, areas with

higherlevelsof

TSPs

tendtobemore

urbanized andhave

higher per-capitaincomes,populationdensities,and crimerates.

7

Consequently, cross-sectional estimatesofthehousingprice-air quality gradient

may

beseverely biased due to omitted variables. This is one explanation for the

wide

variability inHPS

estimates

and

the relatively frequent examples of perversely signed estimates from the cross-sectionalstudies ofthe last 30 years (Smith and

Huang

1995).8Our

firstgoal is to solvethisproblem of

omittedvariables.

Self-selection to locations based

on

preferences presents asecond sourceofbiasinestimation of5

Heckman, Matzkin, and Nesheim (2002) examine identification and estimation ofnonadditive hedonic models.

Heckman, Matzkin, and Nesheim (2003) examine the performance of estimation techniques for both types of

models.

6

See Halvorsen and Pollakowski (1981)and Cropper et al. (1988) fordiscussions ofmisspecificationofthe

HPS

duetoincorrectchoiceoffunctionalformforobservedcovariates.

7

Similarproblems arise

when

estimatingcompensatingwage

differentialsforjobcharacteristics,suchas the riskofinjuryordeath. Theregression-adjusted associationbetweenwages and

many

jobamenities isweak

andoftenhas acounterintuitive sign (Smith 1979; Black and Kneisner 2003).

Brown

(1980) assumes that the biases are due topermanentdifferences across individualsandfocusesonjob'changers'.

8

Smith and

Huang

(1995)find that a quarter ofthereported estimates haveperverse signs; thatis, theyindicate atheaverage

MWTP

forcleanair inthepopulation. In particular, ifindividualswith lower valuationsforairquality sort to areas with worse air quality, then estimatesofthe average

MWTP

that do notaccountforthis can be biased

upward

ordownward

dependingon

the structureofpreferences andtheamount

ofsorting. This is an especially salient issue for thispaper, because its identification strategy is based on

comparisons ofdifferentregionsofthe countryandtheseregionsaredetermined

by

the level of TSPs.So

ifindividuals have sortedbased

on

pollution levels, the approachmay

produce estimates ofthe averageMWTP

that are basedon non-random

subpopulations. Thus, our second goalis to estimatethe averageMWTP

while accounting forself-selection andtoprobehow

MWTP

may

varyinthepopulation.The

consequences ofthe misspecification ofequation (1)were

recognized almost immediatelyafterthe original

Rosen

paper. For example, Small(1975) wrote:I have entirely avoided...the important question of whether the empirical difficulties,

especially correlation

between

pollution andunmeasured

neighborhood characteristics,areso

overwhelming

as torenderthe entiremethod

useless. Ihope

that...futurework

canproceed to solving these practical problems....

The

degree of attention devoted to this[problem]...is

what

will reallydeterminewhetherthemethod

standsorfalls.. ."[p. 107].

In the intervening years, this

problem

of misspecification has received little attentionfrom

empiricalresearchers9, even though

Rosen

himself recognized it. 10Thispaper's aims are to focus attentionon this

problem

ofmisspecification and to demonstratehow

the structure ofthe Clean Air Actmay

provide aquasi-experimental solutioninthecase of housingpricesand TSPs.11

II.

Background

on

FederalAir Quality RegulationsBefore 1970 the federal

government

did not play a significant role in the regulation of airpollution; that responsibility

was

left primarily to state governments.12 In the absence of federallegislation,

few

states found it in their interest to impose strict regulationson

polluters within their9

Gravesetal. (1988)isanexception.

10

Rosen ( 1986) wrote, "It is clear thatnothingcan be learned aboutthe structure ofpreferencesin asingle

cross-section..." (p. 658),and

"On

theempiricalsideofthesequestions, the greatest potential for furtherprogressrestsindevelopingmoresuitablesourcesofdataonthenatureofselectionandmatching..."(p.688).

11

Inanearlierversionofthispaper,

we

outlinedandimplementedamethodthatexploits featuresoftheCleanAirActtoestimate

MWTP

functionsforTSPs(Chay and Greenstone2001). Thismethodrequiresvery strongassumptionsthat

may

notbeplausible,sothismaterialisnotpresentedhere.12

Lave and

Omenn

(1981) and Liroff (1986) provide more details on theCAAAs.

In addition, see Greenstonejurisdictions.

Concerned

with the detrimental health effects of persistently high concentrations ofsuspended particulates pollution,

and

of

other air pollutants, Congress passed the Clean AirAct

Amendments

of1970.The

centerpiece of theCAAAs

is the establishment of separate federal air quality standards,known

as theNationalAmbient

Air Quality Standards(NAAQS),

for five pollutants.The

stated goalofthe

amendments

istobring all countiesintocompliance withthe standardsby

reducinglocal airpollutionconcentrations.

The

legislationrequirestheEPA

to assign annually each county to eithernonattainmentor attainmentstatus foreach ofthe pollutants,

on

thebasis of whethertherelevant standard is exceeded.The

federalTSPs

standard is violated ifeither oftwo

thresholds is exceeded: 1) the annual geometricmean

concentration exceeds 75ug/m

, or 2) the second highest daily concentration exceeds260

ug/m

3

(see

Appendix

Table l).13

The

CAAAs

direct the 50 states to develop and enforce local pollution abatementprograms

thatensurethateach oftheircountiesattainsthe standards. Intheirnonattainmentcounties, statesarerequired

to develop plant-specificregulations for everymajor source ofpollution.

These

local rulesdemand

thatsubstantial investments,

by

eithernew

or existing plants, beaccompanied by

installation ofstate-of-the-art pollution abatement equipment and strict emissions ceilings.

The

1977amendments added

therequirement that any increase in emissions

from

new

investmentbe

offsetby

a reduction in emissionsfrom

another source withinthesame

county.14 Statesare alsomandated

to setemissionlimitson

existingplants innonattainmentcounties.

In attainment counties, the restrictions

on

polluters are less stringent. Large-scale investments,such asplant openings and large expansions atexisting plants, requireless expensive (andless effective)

pollution abatement equipment;

moreover

offsets are not necessary. Smaller plants and existing plantsare essentiallyunregulated.

13

In addition to the TSPs standard, Appendix Table 1 lists the industrial and non-industrial sources, abatement

techniques, and health effects of TSPs. The

TSPs

standard prevailed from 1971 until 1987, when, instead ofregulatingallparticulateswith anaerodynamic diameterlessthan100micrometers,the

EPA

shifteditsfocusto fineparticles. The regulations were changed to apply only to emissions of

PM-lOs

(particles with an aerodynamicdiameterofatmost 10micrometers)in 1987andtoemissionsofPM-2.5sin1997.

14

Offsets could be purchased from a different facility or could be generated by tighter controls on existing

Both

the states and the federalEPA

are given substantial enforcementpowers

to ensure that theCAAAs'

statutes are met. For instance, the federalEPA

must

approve all state regulationprograms

inorderto limit the variance in regulatory intensity across states.

On

the compliance side, states runtheirown

inspectionprograms andfrequently fine noncompliers.The

1977

legislationmade

the plant-specificregulations both federaland state law,

which

gives theEPA

legal standingtoimpose penaltieson

statesthat

do

not aggressively enforcetheregulations andon

plants thatdo

notadheretothem.Nadeau

(1997) andCohen

(1998)document

the effectiveness ofthese regulatory actions at theplantlevel.

Henderson

(1996) providesdirect evidencethat theregulationsaresuccessfully enforced.He

finds that ozone concentrations declined

more

in counties thatwere

nonattainment forozone

than inattainmentcounties. Greenstone (2004) finds that sulfur dioxide nonattainment status is associatedwith

modest

reductions in sulfur dioxide concentrations. In this paper andChay

and Greenstone (2003a),we

find striking evidence that

TSPs

levels fell substantiallymore

inTSPs

nonattainment counties than inattainment counties duringthe 1970s.1

HI.

Data

Sourcesand

DescriptiveStatisticsTo

implement our analysis,we

compile themost

detailed and comprehensive data availableon

pollution levels,

EPA

regulations, and housingvalues for the 1970s. Here,we

describe the data sourcesandprovide

some

descriptivestatistics.More

detailsonthe dataareprovidedintheData Appendix.A.

Data

SourcesTSPs

PollutionData

and

National Trends.The

TSPs

datawere

obtainedby

filingaFreedom

ofInformation

Act

request with theEPA

that yielded theQuick

Look

Report file,which

comes

from theEPA's

Air QualitySubsystem(AQS)

database. This file contains annual information on the location ofandreadingsfromevery

TSPs

monitorin operationintheU.S. since 1967. Since theEPA

regulationsare1

Greenstone(2002) providesfurtherevidence ontheeffectivenessofthe regulations.

He

finds thatnonattainmentstatus is associated with modest reductions in the employment, investment, and shipments of polluting

manufacturers. Interestingly,theregulationofTSPshaslittle associationwithchangesinemployment. Instead,the

appliedatthecountylevel,

we

calculatedthe annualgeometricmean

TSPs

concentration foreach countyfrom

the monitor-level data. For counties withmore

thanone

monitor, the countymean

is a weightedaverage ofthe monitor-specific geometric means, with the

number

ofobservations per monitor used asweights.

The

file alsoreportsthefour highestdailymonitorreadings.Our

1970 and 1980 county-level measures ofTSPs

are calculatedwith datafrom

multiple years.In particular, the 1970 (1980) level

of

TSPs

is the simple average over a county's nonmissing annualaverages in the years 1969-72 (1977-80). These formulas mitigate

measurement

error in theTSPs

measures. Further the

EPA's

monitoringnetwork

was

stillgrowing

in the late 1960s, so the 1969-72definitionallowsfor a largersample.

There are

two

primary reasons forourexclusive focuson

TSPs

ratherthanon

otherforms ofairpollution. First,

TSPs

isthemost

visibleform

ofairpollution and hasthemost

pernicious health effectsofall the pollutants regulated

by

theCAAAs.

16 Second, theEPA's

monitoringnetwork

forthe other airpollutants

was

initsnascent stages in the early 1970sand

the inclusion ofthesepollutants in ourmodels

severelyrestrictsthe sample size.17

TSPs

Attainment'/Nonattainment Designations.The

EPA

did not begin to publicly release theannual list of

TSPs

nonattainment counties until 1978.We

contacted theEPA

butwere

informed thatrecords

from

the early 1970s "no longer exist." Consequently,we

used theTSPs

monitor data todetermine

which

counties exceeded either of the federal ceilings and assigned these counties to thenonattainmentcategory; all other counties are designated attainment.

We

allowed these designations tovary

by

year and basedthem on

the previous year's concentrations. This is likely to be a reasonableapproximation to the

EPA's

actual selection rule, because it is basedon

thesame

information thatwas

availabletothe

EPA.

The

Data

Appendix

providesmore

detailson

ourassignmentrule.16

See Dockery et al. (1993),

Ransom

and Pope (1995), and Chay, Dobkin, and Greenstone(2003) and Chay andGreenstone(2003aand 2003b)forevidenceonthe effects ofTSPsonadultandinfant health,respectively.

17

Only34 outofoursample of988 countieswere monitoredforall oftheotherprimarypollutantsregulatedbythe

1970

CAAAs

atthebeginningand end ofthe 1970s. Alternativelywhen

thesampleislimited tocountiesmonitoredfor

TSPs

and oneotherpollutant, the samplesizes are 135 (carbonmonoxide),49 (ozone),and 144(sulfurdioxide).We

separately examined the relationship betweenhousing values and levels ofozone, sulfur dioxide, and carbonmonoxideinthe 1970sandfoundno association. Chayand Greenstone (1998)findmodestevidencethatchangesin

Housing

Valuesand County

Characteristics.The

property value and county characteristics datacome

from the 1972 and 1983County

and

CityData Books (CCDB).

The

CCDBs

are comprehensive,reliable,and contain awealth ofinformationfor everyU.S. county.

Much

ofthedata isderivedfrom

the1970and 1980 Censuses

of

Populationand

Housing.Our

primaryoutcome

variable is the log-median value ofowner-occupied housing units in thecounty.

The

control variables include demographic and socioeconomic characteristics (populationdensity, race,education, age,per-capita income, povertyand

unemployment

rates,fraction inurban area),neighborhood characteristics(crime rates, doctors

and

hospital bedsper-capita), fiscal/taxvariables(per-capita taxes,

government

revenue, expenditures, fraction spent on education, welfare, health, and police),and housing characteristics (e.g., year structure

was

built and whether there is indoor plumbing).The

Data

Appendix

contains acompletesetofthecontrolsusedinthe subsequentanalysis.The Census

data containsfewervariableson

the characteristicsofhomes

and neighborhoodsthanis ideal. For example, these data

do

not contain informationon

square feet ofliving space, garages, airconditioning, lot size, crime statistics, or schooling expenditures per student.

We

explain ouridentificationstrategy ingreaterdetail below,but

we

believethat itovercomes

some

ofthe limitationsofthe Census data. In particular,

we

include county fixed effects to control for permanent, unobservedvariables anduse the indicator fornonattainmentstatus as an instrumental variable inan effort to isolate

changes in

TSPs

thatare orthogonaltochangesintheunobserveddeterminantsof housing prices.We

note thatanumber

ofstudieshave used census tractleveldata orevenhouse-levelprice dataand focused

on

local markets (e.g., Ridker andHenning

1967, Harrison and Rubinfeld 1978,and

Palmquist 1984). In contrast, the unitofobservationin ourdata isthe county.

Two

practical reasons forthe use of these data are that

TSPs

regulations are enforced at the county-level and census tracts aredifficultto

match between

the 1970and 1980Censuses.The

use ofthiscounty-level dataraisesafew

issues. First intheabsence ofarbitrary assumptionsabout

which

countiesconstitute separate markets,itisnecessarytoassume

thatthere isanationalhousingmarket.18

The

benefitofthis is thatour estimates ofMWTP

will reflect the preferences ofthe entireUS

population,ratherthanthesubpopulation that livesina particular cityorlocalmarket.

The

costisthatwe

are unableto explore the degree ofwithin-county taste heterogeneity and sorting. If taste heterogeneity

and sorting are greaterwithin counties than

between

counties, as is likely the case, then the subsequentresults willunderstatethe individual-leveldispersionin

MWTP.

Second, the hedonic approach as originally conceived is an individual level

model

andaggregation to the county-level

may

inducesome

biases. Forexample

ifthe individual relationship isnonlinear, the aggregation will obscure the true relationship.

We

suspect that the aggregation to thecounty-level

may

not be an important source ofbias. Notably, our cross-sectional estimatesfrom

thiscounty-level data are very similar to the estimates in the previous literature that rely

on

more

disaggregated data

and

aresummarized

inSmithandHuang

(1995).Further, the aggregation does not lead to the loss of substantial variation in TSPs.

Using

theavailability ofreadings

from

multiple monitors inmost

counties,we

find that only25%

of the totalvariation in 1970-80

TSPs

changes isattributable towithin-countyvariation,withtherestdue tobetween-county variation. Finally, a census tract-level (or individual-house level) analysis introduces inference

problems that a county-level analysis avoids because there are substantially fewer monitors than census

tracts(orhouses). 19

B.DescriptiveStatistics

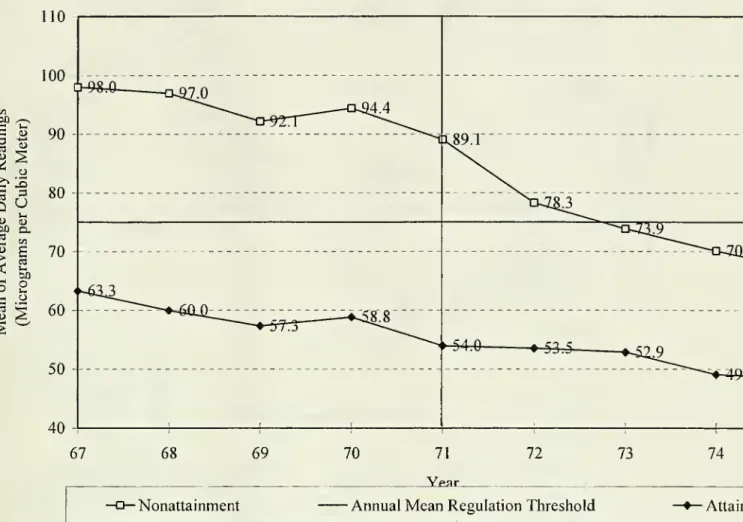

Figure 1 presents trends from 1969-1990 in average particulates levels across the counties with

monitor readings in each year.20 Air quality

improved

dramatically over the period, withTSPs

levelsfalling

from

an averageof85ug/m

3 in 1969to 55pg/m

3 in 1990.Most

ofthe overallpollutionreduction18

Giventhis assumption,itis sensibletoalsoexplorewhether

TSPs

affectwages as inRoback (1982).We

findnoassociationbetween

TSPs

andwagesandbrieflydiscuss theseresults inSectionVII.19

For example, HarrisonandRubinfeld's (1978)analysis of506censustracts relieson only 18

TSPs

monitors. Asnoted by Moulton (1986), the treatment ofthese conelated observations as independent can lead to incorrect inferences.

These are weighed averages ofthe county means, with the county's population in 1980 used as weights. The

sample consists of 169 counties with a combined population of 84.4 million in 1980. The unweighted figure is

qualitatively similar.

occurredin

two

punctuatedperiods.While

the declinesinthe 1970s correspond withthe implementationofthe 1970

CAAA,

the remainingimprovements

occurred during the 1981-82 recession.As

heavilypolluting manufacturing plants in the Rust Belt permanently closed due to the recession, air quality in

these areas

improved

substantially(Kahn

1997,Chay

and Greenstone 2003b). This implies that localeconomic

shocks could drive both declines inTSPs

and declinesin housingprices. Below,we

find thatfixed-effectsestimatesofthe

HPS

may

be seriouslybiasedby

theseshocks.Table 1 presents

summary

statisticson

the variables thatwe

control for in the subsequentregressions.

The

means

are calculated as the average across the 988 counties with nonmissing data onTSPs

concentrations in 1970, 1980, and 1974 or 1975, aswell asnonmissing housingprice data in 1970and 1980. Thesecounties

form

theprimary sample,and theyaccountforapproximately 80percentoftheU.S. population. All monetary figures are denotedin 1982-84 dollars. During the 1970s the

mean

ofthecounties'

median

housing price increasedfrom

roughly $40,300 to $53,168, whileTSPs

declinedby

8ug/m

3. Per-capitaincomes

roseby

approximately15%,

andunemployment

rateswere

2.2 percentagepointshigher at the

end

ofthedecade.The

increase in educational attainment duringthis period is alsoevident.

The

population densityandfractionof peopleresidingin urbanized areasare roughlyconstant atthebeginningandend ofthe decade.21

IV.

The

CAAAs

asaQuasi-Experimental

Approach

totheHedonic

IdentificationProblems

Inthe ideal analysis ofindividuals' valuation ofairquality,airpollution concentrations

would

beorthogonal to all determinants of housing prices and tastes for clean air. Since this orthogonality

condition does not hold, this section describes

how we

exploit the differences in regulatory intensityintroduced

by

theCAAAs

to address the identification problems described in Section I B.The

firstsubsection demonstrates that

TSPs

nonattainment status is strongly correlated with declines inTSPs

concentrations and increases in housing prices. These findings appear robust to exploiting the

discreteness ofthe functionthat determines

TSPs

nonattainmentstatus.21

Sincethe definition ofthevacancy variableschanges overtime, itisimpossible to includethe firstdifferenceof

these variables in the subsequent regressions. Consequently, the regressions separately control forthe 1970 and

1980levelsofthesevariables.

The

second subsection provides theoretical and statistical rationales for using mid-decadeTSPs

nonattainmentstatus as aninstrumentalvariable, ratherthanbeginningof decade nonattainment status. It

also highlights the likely problems with the conventional cross-sectional and fixed effects estimation

strategies.

A.

TSPs

NonattainmentStatusand Changes

inTSPs

Concentrationsand

Housing

PricesThis subsection explores the relationship

between

TSPs

nonattainment status and changes inTSPs

concentrations and housingprices. Figure2A

examines the initial impact ofthe 1970CAAAs

on

TSPs

concentrations.The

counties with continuous monitorreadingsfrom

1967-1975 are stratifiedby

theirregulatorystatus in 1972,

which

isthe firstyearthattheCAAAs

were

in force.22The

horizontallineat 75

pg/m

3 is the annual federal standard and the vertical line separates the pre-regulation years (1967through 1971)

from

the years that the regulationswere

enforced.The

exactTSPs

concentration isreportedateachdatapoint.

Beforethe

CAAAs,

TSPs

concentrationsare approximately 35pg/m

3 higherinthenonattainmentcounties.

The

pre-regulation time-seriespatterns ofthetwo

groups are virtually identical.From

1971 to1975,the setof 1972 nonattainment counties

had

astunning22-pg/m

3reduction inTSPs, whileTSPs

fellby

only 6pg/m

3 in attainment counties, continuing their pre-1972 trend. This impliesthat virtually theentirenationaldecline in

TSPs

from

1971-75 in Figure 1 isattributable to the regulations.Figure

2B

demonstratesthatmid-1970s

nonattainmentstatusis alsoassociatedwithreductions inTSPs

concentrations. Here, countiesare divided into those thatarenonattainment in eitherorboth 1975and 1976 and thosethat are attainmentin both years.

TSPs

concentrations forboth setsofcounties areplotted for the years 1970-1980 for the

414

counties with readings in every year.Average

TSPs

concentrations decline

by

approximately 17pg/m

3 inboth setsofcountiesbetween

1970and 1974. Thisis surprising since the 1975-6 nonattainmentcounties are

more

likely to be nonattainmentin 1972, but itimplies that, at least as it relates to pre-existing trends, the attainment counties

may

form

a valid2

The sample consists of 228 counties with a total population of 89 million in 1970.

As

the Data Appendixdescribes, 1972 nonattainmentstatusisdeterminedby1971 TSPsconcentrations.

counterfactual for the nonattainment ones.23 Specifically,

mean

reversion and differential trends are notlikely sources ofbias.

Between

1974 and 1980,mean TSPs

concentrations declinedby

6.3ug/m

3 innonattainment counties and increased

by

4.1ug/m

3 in attainment counties. Consequently, mid-decadenonattainmentstatusis associatedwitharoughly 10

ug/m

3relativeimprovement

inTSPs.24 25The

structure ofthe federal regulations lends itselfto the application oftwo

validity tests oftherelationship

between

nonattainment status and changes inTSPs

concentrations and housing prices.Recall,nonattainment statusis a discrete functionofthe annualgeometric

mean

and secondhighest dailyconcentrations of

TSPs

in the previous year.The

first test is a comparison of theoutcomes

ofnonattainmentandattainment countieswithselectionyear

mean TSPs

concentrations "near"75ug/m

3. Ifthe unobservables are similarat this regulatory thresholdthen a comparison ofthese nonattainment and

attainment countieswill control forall omitted factors correlatedwith TSPs. Thistesthasthe features of

a quasi-experimental regression-discontinuity design

(Cook

andCampbell

1979).26The

secondtestcompares

nonattainmentand attainment counties with selection yearmean TSPs

concentrations less than 75

ug/m

3. Here, the variation inregulatory status is based on violations ofthedaily standard.

The

key assumption is that, conditionalon

selection yearmean

TSPs, the assignmentofnonattainment status does not

depend

on

the potential outcome, or is "ignorable" (Rubin 1978). Thisapproachhasthe featuresofamatchingdesign.

23

73 ofthe 265 (117 ofthe 149) 1975-76 TSPs attainment(nonattainment) counties were TSPsnonattainment in

1972. Thus, over25percentofthe countiesswitchedtheirnonattainmentstatusbetweenthebeginning and middle ofthe decade.

24

Theresultsare qualitatively similar

when

Figure2B

isbasedonthe988countiesinourprimarysample.25

When

afiguresimilartoFigure2B

isconstructed forthe 1980s,thereduction inTSPsattributabletomid-decaderegulations cannot be distinguished from differential responses to the 1981-82 recession. This finding is not

surprisinggiven thegeographic variation in the effect ofthe 1981-82 recession(Chay and Greenstone 2003b) and

theterminationoftheTSPsregulatoryprogramin 1987. For theseandothersreasons, this studyfocusessolely on the 1970s. Chay and Greenstone (1998) provide a fuller discussion ofthese issues and present the results from

strategies thataddresstheproblemsinestimatingthe

HPS

forthe 1980s.2

In some contexts, leveraging a discontinuity design

may

accentuate selection biases ifeconomic agentsknow

aboutthediscontinuitypoint and changetheirbehavioras aresult. Giventhewidevarietyoffactors thatdetermine

local

TSPs

concentrations ranging fromwind patterns to industrial output,we

suspectthatcounties were unable toengage in non-random sorting near the TSPs regulatory ceiling. Similarly

we

suspect that during the 1970s,individualhomeownerswereunaware oftheproximity oftheircounty's

TSPs

concentrationtothe annualthreshold,makingitunlikelythattheywould

move

as aconsequence.Figure 3 graphically implements these checks

on

the validityof mid-decadeTSPs

nonattainmentstatus as an instrument. Separately for the 1975 attainment

and

nonattainment counties, each panelgraphs the bivariate relation

between

anoutcome

ofinterest and the geometricmean

ofTSPs

levels in1974, the selectionyear for the 1975 nonattainment designation.

The

plotscome

from

theestimation ofnonparametricregressionsthat use auniformkernel density regression smoother. Thus, they represent a

moving

averageoftheraw

changes across 1974TSPs

levels.27The

difference inthe plots forattainmentand nonattainment counties can be interpreted as the impact of 1975 nonattainment status, both for the

counties exceedingjustthe daily concentration threshold (i.e., counties with 1974 concentrations

below

75

ug/m

3)andforthecountiesexceedingthe annualthreshold.Panel

A

presents the 1970-80 change inmean TSPs by

the level ofmean TSPs

in 1974. First,compare

the nonattainment counties with selection yearTSPs

concentrations justabove

75ug/m

3(demarcated

by

the vertical line in the graph) and attainment counties justbelow

this threshold.The

figure reveals that right at the threshold nonattainment counties

had

an approximately 5ug/m

3 largerdecline in

TSPs

than attainment counties over the course ofthe decade. Further an examination ofthecounties withselection year

TSPs

concentration in the 65-85ug/m

3 rangereveals that thenonattainmentcounties

had

anywhere from

a 10-14ug/m

3 greater reduction inmean

TSPs.The

size of theTSPs

reductions declines forcountieswith 1974

mean

concentrations greaterthan90ug/m

3. Further, the slightdownward

slopeinthe plot forattainment counties isconsistentwithsome

reversioninTSPs.Second, consider the counties with annual

mean

concentrationsbelow

75 (J.g/m3. Here, thenonattainment counties receivedthis designation forhaving as

few

as 2 "bad days". There are 67 suchcounties.

A

comparison ofthesenonattainmentcounties to the attainment ones withselectionyearmean

TSPs

concentrationsinthesame

rangesuggests thatnonattainmentstatus isassociatedwithabouta5-unitgreaterreductionin

mean TSPs

overthedecade.2827

The smoothedscatterplots are qualitatively similar for several differentchoices of bandwidth

-

e.g., bandwidthsthatusebetween 10to20percentofthedatatocalculate localmeans. !S

ThefindingfromFigures2and

3A

thatnonattainmentstatusisassociatedwith reductionsinTSPsconcentrationscontradictsrecentclaimsthattheClean AirAct had noeffectonairquality(Goklany 1999).

Panel

B

plots the conditional change in log-housing valuesfrom

1970-80 separately fornonattainmentandattainmentcounties.

Both

validitychecks indicateastrikingassociationbetween

1975nonattainment status and greater increases in property values over the decade.29

They

suggest thatnonattainmentcountieshad abouta0.02-0.04 log pointrelativeincreaseinhousingprices.

In

summary,

Figures 2 and 3document

that nonattainment status is strongly associated withreductions in

TSPs

and increases in housing prices.The

discrete differences inTSPs

changes andhousing price changes that are visible with the regression discontinuity and matching validity tests

provide convincingsupportfor a causal interpretationofthe effectof1975

TSPs

nonattainment status onthese outcomes.

Finally, Figure 3 foreshadows our results

on

the relationshipbetween

housing prices and TSPs.In particular, the strongcorrespondence

between

the patterns in PanelsA

and

B

suggests that thisquasi-experiment

may

alsobe detecting a casualrelationshipbetween

airpollutionandproperty valuesthroughthe

mechanism

of regulation.The

panels also imply thatMWTP

may

vary with the level ofTSPs

concentrations. Specifically, the ratio of the nonattainment-attainment difference in housing price

increases to thedifference in

mean TSPs

declinesislowerinmagnitudeindirtiercounties (i.e., thosewith1974

TSPs

concentrations above 75pg/m

3).

One

explanation for this difference is that individualswithstrongpreferences forcleanair systematicallysorted to the relativelyclean areas. Inordertoexplore this

possibilityfurther, the

below

implementsan estimationapproachthatestimatestheaverageMWTP,

whileattemptingtocontrol for sorting on heterogeneoustastes.

B.

Mid-Decade TSPs

NonattainmentStatusThere are theoretical andstatistical reasonsthatmid-decade (e.g., 1975-6)nonattainment statusis

a better candidate for an instrumental variable than the beginning of the decade nonattainment

designation. First, consider the theoretical rationale. Since annual county-level housing values are

29

Itshouldbenotedthatthere arenononattainment countieswith 1974geometric

mean TSPs

concentrationsbelow40 pg/m3. Thecountieswith

mean

TSPsconcentrationsbelow40pg/m

3

have

much

smaller populationsandnoticeablydifferent characteristicsfromthecountieswith higherTSPsconcentrations. Therefore, these counties

may

notbecomparabletotheothermonitoredcounties.unavailable,

we

relyon

1970 and 1980Census

data. Additionally, Figures2A

and2B

suggestthat thereis atleast a 2-3 year lagbefore the full effects of

TSPs

nonattainment statuson

pollution reductionsarerealized.

A

focuson

1972 nonattainment statuswould

leave 5-6 years until the 1980 census,which

islikely

enough

time forindividuals to sortthemselvesintonew

locationsand supplytorespond tothese airqualitychanges. Consequently

when

housingprices aremeasured

in 1980, thecomposition of people andhomes

may

differfrom

the composition in 1970. Inotherwords

iflocal housing markets are integratedoverthis timehorizon, it

may

be invalid touse 1970-80 housingprice changestomeasure

theMWTP

fora reductionin

TSPs

inthe early 1970s.30A

focuson

mid-decade nonattainment statusmay

mitigate thisproblem

of compensatoryresponses.

The

intuition is that the changes in air quality due to mid-decade regulation are not evidentuntil the end ofthe 1970s,

which

is roughly thesame

time that theCensus

Bureau

asks about housingvalues. This

may

provide an opportunity to observehow

TSPs

reductions are capitalized withoutsubstantialcontamination

by

general equilibriumadjustments indemand

and supply. Itis evidentthatthevirtually identical "pre-period" change in

TSPs

concentrations in nonattainmentand

attainment counties(recallFigure

2B)

is anecessary conditionforthis approachtobevalid.The

second reason forourfocuson

mid-decadeTSPs

nonattainmentstatusisthatthisdesignationisuncorrected with

most

observabledeterminantsof housingprices, includingeconomic

shocks. Thisisnot true

when

comparing

beginning of decade nonattainment and attainment counties. Further,we

findevidence that there is likely to be substantial confounding in the conventional cross-sectional and fixed

effects approachestoestimating the

HPS.

Table2 presentsevidenceon

thesepoints.Table 2

shows

the associationofTSPs

levels,TSPs

changes,andTSPs

nonattainment statuswithnumerous

determinants of housing prices. In the first four columns, the sample is our base set of988counties.

The

Column

5 entries are derivedfrom

our "regression discontinuity" sample of475

countiesthatare near theannual threshold.

A

countyisincludedinthissample ifitmeetstwo

criteria: 1) its 1974geometric

mean TSPs

concentrations is in the 50-100ug/m

3 range, and 2) ifits 1974 geometricmean

,0

For example, Blanchard and Katz (1992) find that local housing prices fall in the first five years following a

negativelocal employment shockbut reboundfullywithinabout a decade oftheshock. This rebound inprices is

likelydueto thegeneralequilibriumresponsesofconsumers andsuppliersofhousing.

concentrationis

below

75 |J.g/m3

, it

must

be designated attainment(i.e., allcountiesthatarenonattainmentsolelydueto thebad day rule aredropped).

The

column

6 entries arefrom

ourbad day

sample,which

islimitedtothe

419

countieswith 1974 geometricmean

concentrationsbetween

50and

75ug/m

3.The

entries in eachcolumn

are the differences in themeans

ofthe variables acrosstwo

sets ofcountiesand the standard errorsofthe differences(inparentheses).

A

'*' indicates that the difference isstatistically significantatthe

5%

level, while '**' indicates significance at the1%

level. IfTSPs

levelswere

randomly

assigned acrosscounties, onewould

expectveryfew

significant differences.Column

1 presents themean

difference in the 1970 values ofthe covariatesbetween

countieswith 1970

TSPs

concentrations greater and less than themedian

1970 county-levelTSPs

concentration.There are significant differences across the

two

sets of counties for severalkey

variables, includingincome

per capita, population, population density, urbanization rate, the poverty rate, the fraction ofhousesthat are

owner

occupied, andtheshareofgovernment

spending on education. It is interesting thatmean

housing values are higher in the dirtier counties, although this difference is not statisticallysignificant at conventional levels.

Although

it is not presented here, an analogous examination ofthemeans

in 1980 leads to similar conclusions. Overall, these findings suggest that "conventional"cross-sectional estimates

may

be biased dueto incorrect specification ofthe functionalform

ofthe observablesvariablesand/oromittedvariables.

Column

2 performs a similaranalysis forthe 1970-1980TSPs

changes. Here, the entries are themean

difference inthe change inthecovariatesbetween

counties with achange inTSPs

that is less (i.e.,larger declines) and greater than the

median

change in TSPs. Reductions inTSPs

arehighly correlatedwith

economic

shocks.The

counties with largepollution declines experienced substantially less growthin per-capita income, smaller population growth, a bigger increase in

unemployment

rates, a largerdecline in manufacturing employment, and less

new

home

construction. These entries demonstrate thatTSPs

concentrations are pro-cyclical and suggest that unless it is possible to perfectly control for theeconomic

cycle,the fixed-effects estimatoroftheHPS

willhavea positivebias. For example,the secondColumn

3compares

the 1970-80change

in thesame

set of variables in 1970-2TSPs

nonattainment and attainment counties. Here, a county is designated nonattainment if it exceeds the

federal standards in any of the years 1970, 1971, or 1972; all other counties are in the attainment

category.

The

nonattainmentcountieshad

a smaller increaseinper-capitaincome growth

and largerand

statistically significant declines in population, manufacturing

employment,

new home

construction,and

populationdensity thantheattainmentcounties.

We

suspectthatthepopulationflowsreveal a substantialworsening of

economic

conditions innonattainment counties. This worsening islikelyduetonon-neutralimpacts of the 1974-75 recession and/or the

economic

effects of the regulations themselves (e.g.,Greenstone 2002). Just as with the fixed effects results, these entries suggestthat estimates thatrely

on

1970-2

TSPs

nonattainment status as an instrumentmay

be positively biased due to the confounding ofchanges in

economic

activity with the regulation-induced change in TSPs.These

findings imply thatbeginningof decade nonattainmentstatusisnotanattractivecandidate foraninstrumentalvariable.31

Columns

4

repeats this analysisamong

1975-6TSPs

nonattainmentand attainment countiesand

finds that the observable determinants of housing prices are better balanced across these counties.

Remarkably, the mid-decade nonattainmentinstrumentpurges the non-neutral

economic

shocksapparentabove. For example,thedifferencesinthechangesinper-capitaincome, totalpopulation,

unemployment

rates, manufacturing

employment,

and

new

home

constructionamong

thetwo

sets ofcounties are allsmaller in magnitude than in the other

columns and

statistically indistinguishablefrom

zero. Also,nonattainment and attainment counties

had

almost identical changes in urbanization rates during the1970s, suggesting that differential 'urban sprawl' within counties is not a source of bias.32 Notably,

nonattainmentcountieshad both agreaterreductionin

TSPs

andagreaterincreaseinhousingvaluesfrom

1970-80,foreshadowing ourinstrumental variableresults.

Finally,

columns

5 and 6compare

the covariates across 1975TSPs

nonattainment and attainmentcounties fortheregression discontinuity and

bad

day samples. Itis evident thattheobservable variables31

Countiesthatwere 1973-4TSPs nonattainmentalso hadstatistically significant largerdeclines inpopulation and

increasesinthepovertyrate. 32

Whilethere aresomesignificantdifferencesbetweennonattainmentandattainment countiesin 1970 valuesofthe

variables,thehypothesisofequal populationdensities in 1970cannotberejectedatconventionallevels.

are well balanced

by

nonattainment status in these columns. In fact,none

of themean

differences incolumn

5 arestatisticallydifferentfrom

zero andonlytwo

ofthem

are incolumn

6.33Although a direct test ofthe validity ofthe exclusion restriction is as always unavailable, it is

reassuring that our instrumental variable is largelyuncorrectedwith observable determinants of housing

prices. Overall, the results in this table suggest that using mid-decade nonattainment status as an

instrumental variablehas

some

important advantages over "conventional" estimation strategiesand

alsoovertheuseof beginning ofdecade nonattainmentstatusasaninstrumentalvariable.

Figure 4 provides a graphical overview ofthe location ofthe 1975-6

TSPs

nonattainment andattainment counties.

A

county's shading indicates its regulatory status; light gray for attainment,blackfornonattainment, andwhite forthecountieswithout

TSPs

pollutionmonitors.The

pervasiveness oftheregulatory

program

is evident. For example, 45 ofthe 51 stateshad

at least one county designatednonattainment. This is important if there are regional or state-specific determinants ofthe change in

housingprices

between

1970 and 1980.In

summary,

there are severalreasonswhy

ourapproachto estimatingtheHPS

may

be attractive.First,

TSPs

nonattainment status is strongly associated with large differential reductions in particulateslevels across counties.

The

timing and location ofthe changes provide convincing evidence that theestimated pollutionimpact

may

be causal. Second, the nonattainmentdesignation islargely uncorrelatedwith observable determinants of housing price changes, including

economic

shocks. In fact, theinstrument appears to purge the local

demand

and supply shocks that contaminate estimates basedon

'fixed-effects' analyses. Third, since the regulations are federally mandated, their imposition is

presumably orthogonal to underlying

economic

conditions andthe local politicalprocess determining thesupply ofnon-marketamenities.34

33

Further, thedifferencesinthe 1970levelsofthe variables are alsosmallerinthese restrictedsamples. Thisis

especially truein theregression discontinuity sample, wherethehypothesisofequalmeanscannotberejected forall

the covariates,except

%

Urban(p-value=.037).34

Scientific evidence provides additional support for the credibility ofregulation instruments that depend on

pollution levels. Cleveland et al. (1976) and Cleveland and Graedel (1979) document that wind patterns often

transportairpollutionhundreds ofmilesandthattheozone concentrationofair entering intothe

New

Yorkregionin the 1970s often exceeded the federal standards.

A

region's topographical features can also affect pollutionconcentrations. Counties located in valleys (e.g., Los Angeles, Phoenix, Denver, the Utah Valley) are prone to

weatherinversionsthatlead toprolongedperiodsofhighTSPsconcentrations.

V.

Econometric

Models

fortheHPS

and

Average

MWTP

Here,

we

discuss the econometricmodels

used to estimate the hedonic price locus. First,we

focus

on

theconstantcoefficientsversion ofthese models.We

then discuss arandom

coefficientsmodel

that allows for self-selection bias arising

from

taste sorting.We

show

how

thismodel

identifies theaverage

MWTP

inthepopulationwhileproviding a simple statistical testofsortingbasedon

preferencesforclean air.

A. Estimationofthe

HPS

GradientThe

cross-sectionalmodel

predominantly usedintheliteratureis:(2) Yc70

=

Xc7o'P+

6T

C70+

Ec70, Ec70=

0tc+

Uc70(3)

T

C70=

X^o'II+

T| C70, T| C70=

A,c+

V

c70,where

yc70 is the log of themedian

property value in county c in 1970,X

c70 is a vectorof

observedcharacteristics,

T

c70 isthegeometricmean

ofTSPs

across all monitors inthecounty, andsc70and

r\c70 aretheunobservable determinantsof housing pricesand

TSPs

levels, respectively.35The

coefficientG is the'true' effect of

TSPs

on

properly values and is interpreted as the average gradient oftheHPS.

Forconsistent estimation, the least squares estimator of 9 requires E[sc7oqC7o]

=

0. If there are omittedpermanent (ac and

X

c) ortransitory(u^oand v

c70) factors that covary with bothTSPs

and housing prices,thenthe cross-sectionalestimatorwillbebiased.

With

repeated observations over time, a 'fixed-effects'model

implies that first-differencingthedatawillabsorb thecounty

permanent

effects,a

cand A. c. This leadsto:(4)

y

G80 -y

C70=

(Xcso-Xc7o)'P+

6(T

c80-T

c70)+

(Uc80-Uc7o)(5)

T

c8o-T

c70=

(Xcso-Xc7o)'Il+

(vc80-V

c70).35

For each county,

T

c70 (Tc8o) is calculated as the average across the county's annualmean

TSPs concentrationsfrom 1969-72 (1977-80). Eachcounty's annual

mean

TSPs concentrationistheweightedaverageofthe geometricmean

concentration of each monitor in the county, using the number of observations per monitor as weights.Averagingovermorethanoneyearreducestheimpact of temporaryperturbations onourmeasures ofpollution.

Foridentification,theleast squares estimatorof9 requires E[(uC8o-uc70)(vc80

- v

c70)]=0. That is,there areno

unobserved shocks topollutionlevels thatcovary with unobserved shocks tohousingprices.Suppose

there is aninstrumental variable (IV),Z

c, that causes changes inTSPs

without havingadirect effect

on

housingpricechanges.One

plausibleinstrumentismid-1970sTSPs

regulation,measured

by

theattainment-nonattainment statusofa county. Here,equation (5)becomes:(6)

T

c80-T

c70=

(Xc80-X

c7o)'nTx+

Z^Efe

+

(vc8o-vc70) ,and(7)

Z

c75=

l(Tc74>

T

)=

1(vc74>

T

-Xc

74'n

-X

c),where

Z

c75 is the regulatory status of county c in 1975, 1(») is an indicatorfunction equal to one iftheenclosed statement is true, and

T

is themaximum

concentration ofTSPs

allowedby

the federalregulations.36 Nonattainment status in 1975 is a discrete function of

TSPs

concentrations in 1974. Inparticular, if

T^

andT

c™

x

are the annual geometric

mean

and 2nd highest dailyTSPs

concentrations,respectively,thenthe actualregulatory instrumentused is

l(T

c a 7|

>

75ug/m

3 orT

c™

x>

260

ug/m

3).An

attractive feature ofthis approach is that the reduced-form relations are policy relevant. Inparticular,

n

Tzfrom

equation (6) measures the change inTSPs

concentrations innonattainment countiesrelativetoattainment ones. In theotherreduced-formequation,

(8) Vc80-yc70

=

(Xc80"X

c7o)TIyX+

Z

c75llyz+

(ucso-Uc70 )°,n

yZcapturesthe relativechange inlog-housingprices. SincetheIV

estimator, (9iV),is exactly identified,itisa simpleratioofthe

two

reducedformparameters,thatis 8iV=

n

yz/nTz.Two

sufficient conditions fortheIV

estimator (9iV) toprovide a consistent estimate oftheHPS

gradientare

H

TZ*

andE[v

c74(uc8o- uc70 )]=

0.The

firstconditionclearly holds.The

second conditionrequires that unobserved price shocks from 1970-80 are orthogonal to transitory shocks to 1974

TSPs

levels. Inthe simplestcase,the

TV

estimatorisconsistentifE[Z

c75(uc8o-Uc70)]=

0.We

implement

theIV

estimatorin anumber

of ways. First,we

use all ofthe available data andthemid-decade nonattainmentindicator as the instrumentto obtain9IV.

We

alsocalculateIV

estimatesintwo

otherways

that allow forthe possibility that E[vc74(uc80-u

c70 )]^

overthe entire sample.The

first36

In practice, our preferred instrument equals 1 ifacounty is nonattainmentin 1975 or 1976 and otherwise. In

thissection,