‘‘An Album of Small, Clear Pictures’’

George Buchanan, Humphrey Jennings’s May the Twelfth, and the Practice of

Looking Away from the Main Event in 1930s London.

Anna Cotrell

Abstract

This article considers two representations of public events in 1930s London – one photographic, by Humphrey Jennings, the other novelistic, by the journalist and novelist George Buchanan. Jennings’ montage of photographs for the coronation of George VI on May 12th, 1937, made as part of Jennings’

involvement with the Mass-Observation project, and Buchanan’s descriptions of an ordinary woman’s perceptions of public events in London in Rose Forbes (1937) demonstrate the importance of the concept of ‘the photographic’ to 1930s representations of ordinary, non-intellectual urban experiences. Comparisons with photography often worked against aspiring novelists such as Buchanan, used as shorthand for journalistic or amateurish writing. However, read alongside Jennings’ experiments with the photographic medium, with which Buchanan’s writing shares not only thematic but also formal elements,

Rose Forbes can be understood as an attempt to use the kind of visual selection the photographic frame

encourages as a point of entry into the daily experiences of those who usually get only a restricted view of the main event.

Résumé

Cet article analyse deux représentations d’événements publics dans les années 1930 à Londres, l’une photographique, par Humphrey Jennings, l’autre romanesque, par le journaliste et écrivain George Buchanan. D’une part: un montage photographique fait à l’occasion du couronnement de Georges VI le 12 mai 1937, qui fait partie du travail de Jennings dans le Projet d’Observation de Masse. D’autre part, dans le roman Rose Forbes (1937), les descriptions de ce qu’observe autour d’elle une femme quelconque qui se promène dans les rues. Les deux œuvres témoignent de l’importance du «photographique» dans la représentation d’expériences urbaines banales, ordinaires, dans ces années-là. La comparaison avec la photographie était un argument souvent utilisé pour déprécier le travail d’auteurs comme Buchanan, accusés de n’être qu’un écrivain journaliste ou amateur. Toutefois, si on lit un roman comme Rose Forbes en tenant compte des expériences de Jennings avec le médium photographique, comme de nombreuses correspondances formelles et thématiques nous y invitent, il devient possible de mieux apprécier ce texte comme une tentative de s’approprier la technique photographique de sélection visuelle et d’explorer ainsi de nouvelles voies d’accès aux expériences de ceux et de celles qui n’ont pas de vue d’ensemble des événements en cours.

Keywords

In George Buchanan’s novel Rose Forbes: The Biography of an Unknown Woman (1937), the eponymous heroine slips out of the millinery shop where she works to watch Trooping the Colour. Rose has little luck spotting the monarch, unable to secure a good view of the event, which for her is ‘‘reduced to bits of red seen in a broken mirror which she held above her head’’:

She was pleased at one tiny episode: heedless of bands, red ranks slow-marching, vast crowds, cinema operators – three pigeons pecked and loitered together on the sanded ground, peeking about beside the soldiers’ feet.

Pigeons had no feeling for pageantry.

Two hundred yards from the fuss, the lake of St. James’s Park lay peaceful, almost deserted. Alone under a tall white umbrella stuck in the grass sat an elderly lady in black, painting clumps of irises by the water.

While she painstakingly jabbed on her greens and her blues, she seemed not to notice the distant strains of bands playing ‘There’s something about a soldier’ with sentimental precision. (161-2)

Buchanan’s description works against the cliché of the masses gawping at public events: Rose’s wry observation of the indifferent pigeons identifies her as an aloof and critical observer, unimpressed by the pomp and circumstance, which she even finds ‘‘faintly boring’’ (161). In another novel, Buchanan makes a similar point about a lower-middle-class couple called Lucy and James who can hardly see anything at the 1937 coronation of George VI because ‘‘[t]hey had not been so fanatical as to sit up all night on the pavement’’; they ‘‘considered themselves sensible and not hysterical on public occasions’’ (Entanglement 86). James, Lucy and Rose are ordinary men and women of the crowd who are “always photographed from above, looking like a plate of blackberries” (86), and whose points of view are typically excluded from accounts of public events. The descent to the eye level of such an insignificant observer serves both an expression of Buchanan’s political persuasion, and a confirmation of his belonging to the 1930s literary trend to record the everyday experiences of an ordinary or average Londoner.

As a lower-middle-class worker who has moved to London from an Irish province, Rose fits perfectly into this definition of the ordinary or average – women like her appear in countless British novels from the late 1920s onwards. Rose’s experiences follow a pattern that brings together several recurring themes of the urban literature of the decade: unemployment, a dull suburban marriage, a sexual awakening and a divorce, the stirrings of a political consciousness, and, finally, a disorientating but thrilling acceptance of the anonymity and loneliness of city life as liberating. Rose Forbes is comparable to Storm Jameson’s Mirror in Darkness trilogy, which follows the similar trials of the aspiring writer Hervey Russell. It also has similar elements to novels such as Betty Miller’s The Mere Living (1933), or Norah Hoult’s Youth Can’t Be Served (1933), or even J.B. Priestley’s They Walk in the City (1936) - all of them follow the progress of young women in the city, but tend to digress into minute descriptions of the urban environment itself. Hoult and Miller, like Buchanan, had started out in journalism, and their fiction experiments with reportage techniques. Detailed descriptions of characters’ sensory experiences of the city become integral to these narratives, which can at times read as montages of isolated episodes. Buchanan’s biography of ‘a woman’, with the accompanying musings about men, sex, marriage, and fashion, runs parallel to the biography of Rose as an observer. He mixes several different visual

modes or styles in his account of Rose’s development as a Londoner who never stops looking around herself. These inconsistencies in her mode of vision develop alongside a growing dissatisfaction which culminates in Rose’s final rejection of the comforts of marriage and romance. A socialist writer, Buchanan suggests at several points in the novel that what stands in the way of Rose’s political awakening is a consumerist attitude to the world she inhabits. Her indulgent looking at shop windows and inside sleek modern spaces of urban leisure is devoid of thought, and therefore suspect. Thus in one scene, Rose looks at a swimming-pool with its visually pleasing pattern of ‘‘palpitating blue surface, reaching swimmers’ arms, dark heads, the splashing dives’’ (164) – a sleek image that resembles advertising posters of the kind that were displayed on the London underground in the 1930s.1 Rose herself becomes a part of this

image, flat and emptied of an inner life: ‘‘Rose blew cigarette smoke into the air; she became contented and stupid’’ (164).

This judgment of Rose is severe, but it is inconsistent. Throughout the novel, Buchanan appears to be at least partly in thrall of Rose’s ‘‘stupidity’’ – there is a curiosity and even affection about the way he writes about her self-conscious posturing in new clothes, for example. The close attention Buchanan pays to the trivial aspects of Rose’s daily life suggests that it may be her commercially trained gaze – ‘‘the twentieth-century commercial habit’’ (145) - that allows her to develop a mode of close looking that moves beyond mercantile evaluation. After watching Trooping the Colour, Rose returns to the millinery shop where she works, where she ‘‘co-operated in inventing new ways of twisting shiny straw so that it might crown the obtuse heads of women’’ (116). The odd conflation of casual misogyny and a fascination with the precision of Rose’s work is representative of the novel’s tone. The possibility of reconciling an almost automatic identification of attitudes and activities as vulgar or soulless with a search for aesthetic possibilities within that vulgarity informs all of this writer’s work of the 1930s.

Buchanan is now an almost completely forgotten author, none of his work currently in print, but in the 1930s he was a successful journalist, reviewer, dramatist, and novelist. He came to London from Ireland in the 1920s and worked in Fleet Street throughout the decade. One assignment, for the Sunday

Times, involved Buchanan writing about ordinary lives in Midland cities. In his 1965 memoir Morning Papers, he recalled his preoccupations as a young journalist, among them the need to learn ‘‘to take an

interest in the least thing’’ (Morning Papers 115), and not to ‘‘reject persons of any particular class’’ (60): “I am observing what people are doing on the aesthetic count – even negatively, as philistines, when they complain about the words used in plays or about statues being naked’’ (79).

Buchanan’s investigative method, in particular his choice to include the banal and the ‘‘philistine’’, aligns his journalistic work with the 1930s experiments of the Mass-Observation project, which aimed to record daily life in Britain with the help of ordinary Britons’ testimonies. The founding Mass-Observers, Charles Madge, Tom Harrison, and Humphrey Jennings, had complex goals and even more complex influences and interests (Harrison was an anthropologist, Madge a journalist and poet, and Jennings an artist, poet, and painter), and critical appraisals of Mass-Observation have acknowledged that the work the group produced falls somewhere between the scientific and the poetic.2 In 1937, in a jointly

1. On the Underground posters, see Michael T. Saler, The Avant-garde in Interwar England: Medieval Modernism

and the London Underground (New York: Oxford UP, 1999).

signed letter to The New Statesman, Jennings, Madge, and Harrison outlined the goals and a provisional framework for this new mode of social investigation. This manifesto of an ‘‘anthropology at home’’ emphasised the need to observe facts ‘‘not for the sake of an intellectual minority (a situation in which the fact becomes a possession, a successful, enviable selection)’’, but for the sake of presenting it from as varied a selection of points of view as possible:

[A]ll human types can and must assist in this work. The artist and the scientist, each compelled by historical necessity out of their artificial exclusiveness, are at last joining forces and turning back towards the mass from which they had detached themselves. (Harrison, Jennings, and Madge 155)

Mass-Observers faced their biggest challenge in developing a method that could successfully establish such a bridge between the artistic and the scientific. Accuracy and precision were to be combined with an ability to discern the poetic in the mundane. The tension between the two approaches exemplifies what many 1930s writers on the Left thought about the problem of representing ‘‘the mass’’ in a way that would move beyond the possessive and the voyeuristic. The forms that appeared most suitable in finding a compromise between the ‘‘scientific’’ and the ‘‘artistic’’ were often visual: the media of photography and film were drawn on especially frequently. Thus Storm Jameson, in a much-quote essay ‘Documents’ (1937), written for the Left-wing publication Fact, pointed towards a way for the middle-class writer to avoid the trappings of egotism by means of engaging with a literature of ‘‘fact’’, which implied a literature replete with small details observed in a detached way:

As the photographer does, so must the writer keep himself out of the picture while working ceaselessly to present the fact from a striking (poignant, ironic, penetrating, significant) angle. The narrative must be sharp, compressed, concrete . . . The emotion should spring directly from the fact. (Jameson 15-16)

Jameson expressed the hope that a new literary form might be developed which would be analogous or even ‘‘equivalent’’ (18) to photography or documentary film. Enlisting photography and film as art forms that are somehow more detached or objective than literature reads as naïve, but what makes the essay so important for the 1930s is her insight into the kind of description that invalidates attempts, by socially privileged authors, to write about lives radically different to their own. Jameson advocates the use of striking angles by which she appears to mean close-up or closely framed images. Both clinical and offering an unparalleled proximity to the subject of the writer’s ‘‘objective report’’ (12), the close view of quotidian detail provided the nearest approximation to a style that was ‘‘neither superficial nor slickly dramatic’’ (12). Jameson offers an example of the benefits of such a visual economy in a description of a working-class woman cleaning her kitchen: ‘‘he [the middle-class writer] does not know as much as the woman’s forefinger knows when it scrapes the black out of a crack in the table’’ (Jameson 11).The close-up, then, serves as both a source of depth and a restraining mechanism, preventing the writer from sliding into sentimentality, the ‘‘emotions’’ and ‘‘spiritual writhings’’ (11) provoked in him by the sight of a way life he has never encountered before.

Mass-Observers were similarly concerned about the ways in which visual manifestations of the ‘‘facts’’ of everyday life could be used in order to represent the non-middle-class urban mass. That

the format of the ‘‘objective’’ report was vulnerable to class-bound forms of prejudice is demonstrated clearly in many of the accounts of the day, which were made by ‘‘over two hundred observers.’’ In one episode, an observer relishes his (only slightly delayed) realisation that a ‘‘neat’’ and ‘‘quiet-voiced’’ woman in ‘‘a well-cut coat’’ who speaks to him is actually a prostitute (May the Twelfth 100-1). The full-figure view encourages a reductive looking over of the observed, and throughout May The Twelfth, the Mass-Observers find it difficult to resist the temptation to quickly summarise people by identifying their social status or occupation. Being observant did not always equal being insightful, but there is a sense that the leading Mass-Observers chose to include such instances of banal prejudice because of their commitment to searching for Britons’ ‘‘collective unconscious’’ in unexpected places. Jennings and Madge were both reading Freud at the time, and developed an interest in Surrealism and its possible uses within a social realist project like Mass-Observation.

Jennings in particular was experimenting with the idea of Surrealist ‘‘coincidences’’ – objects or scenes that one might notice accidentally throughout the day, but which cumulatively might add up to a meaningful pattern. Such coincidences, according to Jennings, have ‘‘the infinite freedom of appearing anywhere, anytime, to anyone: in broad daylight to those whom we most despise in places we have most loathed’’ (Jennings 168). Partly, then, the insistent inclusion of banal observations by people whose insight was limited to identifying social stereotypes points to a faith in discovering unconsciously formed patterns within forms of ordinary thinking that are usually ignored by the artist or writer. Jennings’s own account of the day provides the book with its most experimental and visually striking material, some of which approaches Jameson’s ideal of a significant detail that ‘‘leaves no more to be said, and implies everything’’ (Jameson 16). For instance, Jennings provides a brief and cryptic description of a scene in St Jameson’s Park where ‘‘behind the stands there is an area of black mud strewn with pieces of torn newspaper. A woman sits alone in the mud surrounded by the paper, her head in her hands’’ (May the

Twelfth 124). No further explanation of this image is given; it floats independently of the day’s narrative,

as it were. Intriguingly, the banal accounts of observers who were mainly interested in the obvious markers of class are given equal space to Jennings’ exquisite ‘‘montages’’ of more unusual observations. Like Buchanan who was prepared to record people’s ‘‘philistine’’ remarks, Jennings was committed to including material that was created by what Madge and Harrison called ‘‘subjective cameras, each with his or her own individual distortion’’ (First Year’s Work 95).

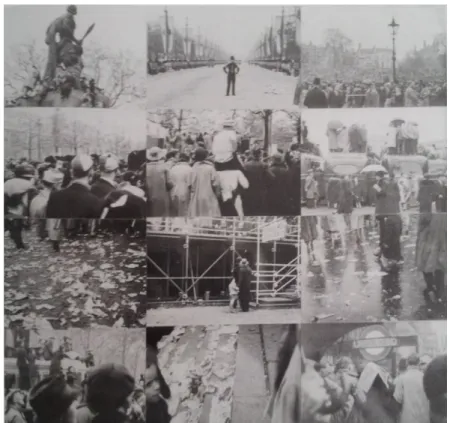

The camera acts as a metonym of the mind of an ‘‘untrained’’ observer (First Year’s Work 95), and for Jennings, a real camera provided access to such as observer’s point of view. Jennings, who was one of the observers on the day, produced a montage of photographs of the event (Illustration 1). It was not included in the published version, but it illustrates Mass-Observers’ goals at the time. Uninformative and repetitive, the montage consists of low-contrast images of people’s backs, hats, and torn paper and rubbish strewn over the wet pavement. It emulates the style of an amateur’s snapshot, a selection of pictures by someone who is not a professional artist. It seems that Jennings is attempting here to reproduce, or inhabit, the sort of vision that is not his own – the point of view of someone who sees little, like Buchanan’s insignificant observers typically seen from above. As a selection, it appears to be undiscerning: the pictures all look similar, to the point of appearing to be different versions of the same objects seen from slightly different angles. Ian Walker has discussed this image in terms of Jennings’s

‘‘tactics of looking away from the main event of the day’’ (Walker 103), and it does seem that the casualness of Jennings’s choices is premeditated.

Illustration 1 Humphrey Jennings, May 12 1937. Used by permission of Marie-Louise Jennings.

There is a deliberate wastefulness about this image, a conscious refusal to choose one’s subject matter carefully. It does not seem to matter that every frame is filled with objects we have already seen. Not only does it record the proliferation of waste-torn paper (a persistent pattern in May the Twelfth),3 but it

also seems to multiply it. The image is remarkably undemanding of the viewer in the sense that it does not dictate the order in which the photographs ought to be viewed. The eye travels freely between the small episodes that are so alike as to make the way they are put together seem almost irrelevant. The people in the photographs seem to have little to do with the main event – essentially, they are looking at each other, or at each other’s backs – or, like the person in the bottom right-hand corner, they have chosen not to look at all, since there is nothing to see.

With this collection of photographs, Jennings appears to be resisting the need to make a selection that would count as representative of the event, which could easily have been a photograph of the monarch, or of crowds photographed from above. Instead, what he offers is a non-selection, as it were: neither of these little pictures can become a definitive image of the Coronation. That Jennings worried about the kinds of choices, or selections, of material that one’s status as an artist and intellectual dictates is evident in his writing of the 1930s, for publications such as the London Bulletin and Contemporary

3. For a discussion of the motif of paper in May the Twelfth, see Steven Connor, ‘A Door Half Open to Surprise: Charles Madge’s Imminences’, New Formations 44 (2001), 56-62.

Poetry and Prose. In an article for the London Bulletin in 1938, Jennings wrote that ‘‘intellectually the

importance of the camera lies clearly in the way in which it deals with problems of choice – choice and avoidance of choice’’ (Jennings, qtd. in Film-Maker, Painter, Poet 20).

Jennings was experimenting with photography at the time, but his other writing from the late 1930s suggests that the problems of choice were not restricted to photography, and that photography was, to an extent, an analogy for similar difficulties in other media. One remark, in an irritated review of Surrealism (1936), edited by Herbert Read, is particularly relevant here. Jennings was dissatisfied with the reception and ‘‘use’’ of Surrealism in England, believing that it had been commoditized and reduced to an adjunct of Romanticism. If Surrealism requires ‘‘forgetting all ‘beliefs’ preceding the picture’’, the distorted version Jennings finds in Read’s Surrealism is little more than ‘‘a series of ‘truths’ and ‘loyalties’ which produce imitations of the creative powers of non-selectivity’’ (Jennings 168). This problem of imitating openness and inclusivity Jennings believes to be specific to the middle-class English intellectual: ‘‘But for the English to awaken from the sleep of selectivity what a task. And to be already a ‘painter’, a ‘writer’, an ‘artist’, a ‘surrealist’, what a handicap’’ (168).

Selectivity, then, refers to a class-bound narrowness of creative vision, but it also implies a self-imposed rigidity that comes with defining oneself as ‘‘a writer’’, or an ‘‘artist.’’ One alternative to this limiting approach appears to have involved inhabiting a point of view which was radically different and which was frequently associated with a restless and inattentive modern type – a woman or man able to notice things only in passing, barely stopping to penetrate below the surface of daily events. This perceived inability to choose well, to pick out the best from a mass of scenes and objects, was often referred to as the ‘‘photographic’’ attitude or method in 1930s literary and cultural criticism. Raymond Mortimer, in a review of Derrick Leon’s novel Livingstones (1933) used the terms ‘‘naturalistic novel’’, ‘‘tranche de vie’’, and ‘‘photography’’ interchangeably, suggesting that all three needed to be ‘‘transcend[ed]’’, preferably by making ‘‘critical implications about present society’’ (Mortimer 326). And Morton D. Zabel went as far as to suggest, in 1934, that contemporary theatre audiences had developed an ‘‘instability in interest and sympathy’’ that could be defined in terms of a ‘‘triumph’’ of ‘‘photography’’, by which Zabel appears to have implied simultaneously a distractedness and a failure to understand anything above ‘‘the commonest denominators of humour, farce, sex appeal, and sensation’’ (Zabel 314).

When Buchanan’s novel was published, it received a lukewarm review from V.S. Pritchett, who wrote in the New Statesman that ‘‘a lot of it is very adroit camera work, an album of small, clear pictures . . . and the pictures are the unremarkable ones that a very ordinary woman would have taken’’ (Pritchett 888, 890). The grumpy dismissal of the photographic or boringly realist is there, but, despite his eagerness to point out the novel’s flaws, Pritchett comes close to identifying its virtues. The ‘‘biography’’ of Rose is indeed an album of generic observations, but I would argue that the way Buchanan uses them is closer to Jennings’s studious disregard of ‘‘selectivity’’ than it is to Pritchett’s implication of a predictable sequence. The material that could be described with the term ‘‘photographic’’ is the least useful and the least informative content of Rose’s life. The series of events that constitute the narrative in Rose Forbes are periodically intruded into by intensely visual descriptions of things that are of no consequence: Rose

notices used bus tickets scattered on the pavement (Rose 142), ‘‘the obvious veins’’ of a man’s hand on the underground (166), and, in a surrealistic episode devoted to the Jubilee of George V, a portrait of the monarch ‘‘in a shop window full of pink corsets’’ (259). Such observations puncture the ‘‘events’’ of Rose’s life which she experiences as a mechanical routine she is helpless to change. Rose’s working day is presented in the form of a montage, but one that has a rigid narrative sequence, which begins to wear Rose down; on ‘‘the morning of the 9,856th day’’ Rose has spent in London, she begins to think of her life as one in which ‘‘nothing ever happens’’ (150):

Clothes on the chair: the pathetic look of stockings, rumpled strips, the embarrassing body-belt. She stoops over her shoes with a glance at the clock.

… Bus … office … typewriter …

Lunch, on a wet or greasy marble-top table, milk and poached egg in a thick crowd. …

Finis, five-thirty.

Life begins at five-thirty. What life? (152-3)

There is a deadening coherence to this description: and this may well be the passage Pritchett had in mind when writing his review. Rose’s life in London is formed from a series of predictable events – unsteady work followed by unemployment, failed affairs, and a dull marriage from which Rose escapes when she falls in love with a communist. The small observations that Rose makes involuntarily and that intrude into this daily sequence create the tension central to the novel, between Rose’s lack of economic and social agency and her growing agency and sophistication as a mature observer of daily life. The ‘‘close-up’’ becomes a political tool in the process of uncovering a form of intelligence that cannot be presented either in terms of a verbally sophisticated intellectual’s inner narrative or schematically by means of a plot. Sitting in a café with an ex-lover, Rose, who had been enthralled by his patronizing talk about art and ‘‘authors she had not read’’ (101), experiences a change of heart via a close visual scrutiny of the man:

It was a curious reversal of last year’s attitudes. He sat with his feet crumpled awkwardly and let the cup of tea become cold.

She wondered: ‘‘When is he going to touch it?’’ She watched the cup. What was the matter with him? He was twisting a corner of the teacloth in his fingers and smiling and saying: ‘‘Yes.’’

…

She saw reflected there all the foolish misery of her own life a year ago. ‘‘I’ve grown, passed on.’’ It was this that made her stare at him – which, no doubt, served only to increase his empty behaviour. (132)

Rose’s initiation into metropolitan life is marked by a sense of a deep inferiority to the man who leaves her feeling ‘‘confused, helpless, feeling negative’’ ‘‘at the end of his tirades’’ (101). At one point she announces to her lover, ‘‘I don’t think. I only have feelings in my stomach’’ (106). This self-defeating attitude is reversed in the café scene where Rose’s observations are no longer denigrated as mere ‘‘feelings’’, but constitute an alternative, and more versatile, intelligence than that represented by the intellectual’s cultural capital.

Mass-Observation as an attempt to make people think actively about ‘‘their environment’’, ‘‘so that [it] may be understood and thus constantly transformed’’ (155). This process of understanding and transformation of reality involves a persistent reconsidering of the aspects of the everyday that are typically overlooked – the things that happen on the periphery of main events. In Buchanan’s novel, Rose achieves this transformative understanding by deliberately diverting her interest from the main reason why she is in the café with her former lover – shortly before their meeting, she had received ‘‘a pathetic invitation to marry him’’ (Rose 132). Rose examines instead that which is peripheral to this charged meeting – the small gestures with which he betrays his own insecurities and, finally, dullness. Rose’s intent staring becomes a process through which she is able to reject the superiority of a highly selective or restrictive social and cultural identity embodied by her lover.

Reading a writer like Buchanan alongside Mass-Observers’ experiments in recording the daily lives of ordinary Britons yields intriguing results. As a novelist who arrived at writing fiction via sociology and journalism, Buchanan represents a generation of British writers who similarly developed their ideas about the novel’s purpose in the politicised 1930s via engagements (and sometimes hostile collisions) with the idea of the sociological case study and reportage. For all of those writers, the principles of sociological, journalistic, or photographic investigation could not be simply imported wholesale into literary work. Instead, they articulated the need for an analogical relationship between literature and the visual arts, and the photographic in particular functioned as an idea before it was understood as a set of stylistic tropes. To the writers and intellectuals of the 1930s, the ‘‘close-up’’ identified an attitude rather than a device to be borrowed from photography and film. The fact that Jennings would become a documentary film-maker does not automatically suggest that he engaged with photography in the 1930s as a professional photographer would – at this point, he seems to have approached it in the same way as Jameson and Buchanan did. The photographic point of view offers an alternative form of understanding of what constitutes a ‘‘fact’’ ‒ a word that crops up constantly in 1930s discussions of politics and art. The only kind of ‘‘fact’’ in which Jennings as a Mass-Observer, and Buchanan as a writer, appear to be interested is the cumulative, flexible, ‘‘prolonged’’ process of the formation of an ordinary person’s aesthetic sensibility. In Buchanan’s novel, Rose’s ‘‘traits are drawn out like elastic . . . something snaps . . . there is an ‘event’, which attracts superficial attention. But in truth it is the drawing-out that is the event’’ (Rose 150). The photographic suggests a form for this drawing-out process, which always happens on the margins of a main event.

Works Cited

Buchanan, George. Entanglement. London: Constable, 1938. Print. --- Morning Papers. London: Gaberbocchus, 1965. Print.

--- Rose Forbes: The Biography of an Unknown Woman. London: Constable, 1937. Print.

Connor, Steven. ‘‘A Door Half Open to Surprise’: Charles Madge’s Imminences.’’ New Formations 44 (Autumn 2001): 52-62. Print.

Nation, 30 January 1937: 155. Print.

Harrison, Tom and Charles Madge, eds. First Year’s Work: 1937-38 by Mass-Observation. London: Lindsay Drummond, 1938. Print.

Jameson, Storm. ‘‘Documents.’’ Fact 4 (July 1937): 10-18. Print.

Jennings, Humphrey. ‘‘Review of Surrealism edited by Herbert Read.’’ Contemporary Poetry and Prose 8, December 1936: 167-8. Print.

Jennings, Mary-Lou, ed. Humphrey Jennings: Film-Maker, Painter, Poet. London: British Film Institute in association with Riverside Studios, 1982. Print.

May the Twelfth: Mass-Observation Day-Surveys 1937 by Over Two Hundred Observers. 1937.

London:Faber and Faber, 1987. Print.

Mortimer, Raymond. ‘‘New Novels.’’ New Statesman and Nation, March 18, 1933: 326. Print. Pritchett, V.S. ‘‘New Novels.’’ New Statesman and Nation, May 29, 1937: 888 - 890. Print.

Saler, Michael T. The Avant-garde in Interwar England: Medieval Modernism and the London

Underground. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. Print.

Walker, Ian. So Exotic, So Homemade: Surrealism, Englishness and Documentary Photography. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2007. Print.

Anna Cottrell has recently completed her PhD at University College London. She works in the field of urban literature and visual culture, and is currently working on her first book. Email: a.kanakova@ucl. ac.uk