HAL Id: dumas-01896854

https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01896854

Submitted on 16 Oct 2018

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Critères pronostiques de mortalité dans l’insuffisance

cardiaque dans une cohorte prospective du CHU

Grenoble-Alpes

Wassima Marsou

To cite this version:

Wassima Marsou. Critères pronostiques de mortalité dans l’insuffisance cardiaque dans une cohorte prospective du CHU Grenoble-Alpes. Human health and pathology. 2018. �dumas-01896854�

AVERTISSEMENT

Ce document est le fruit d'un long travail approuvé par le

jury de soutenance et mis à disposition de l'ensemble de la

communauté universitaire élargie.

Il n’a pas été réévalué depuis la date de soutenance.

Il est soumis à la propriété intellectuelle de l'auteur. Ceci

implique une obligation de citation et de référencement

lors de l’utilisation de ce document.

D’autre part, toute contrefaçon, plagiat, reproduction illicite

encourt une poursuite pénale.

Contact au SID de Grenoble :

bump-theses@univ-grenoble-alpes.fr

LIENS

LIENS

Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 122. 4

Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 335.2- L 335.10

http://www.cfcopies.com/juridique/droit-auteur

UNIVERSITÉ GRENOBLE ALPES UFR DE MÉDECINE DE GRENOBLE

Année :2018

PRONOSTICS PARAMETERS OF DEATH IN HEART FAILURE FOR A

PROSPECTIVE GRENOBLE ALPES UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL COHORT

THÈSE

PRÉSENTÉE POUR L’OBTENTION DU TITRE DE DOCTEUR EN MÉDECINE DIPLÔME D’ÉTAT

Wassima MARSOU

THÈSE SOUTENUE PUBLIQUEMENT À LA FACULTÉ DE MÉDECINE DE GRENOBLE Le : 28/09/2018

DEVANT LE JURY COMPOSÉ DE Président du jury :

Professeur Gérald VANZETTO Membres :

Professeur Gilles BARONE ROCHETTE ( directeur de thèse) Docteur Muriel SALVAT ( co directeur de thèse)

Docteur Maxime MAIGNAN

L’UFR de Médecine de Grenoble n’entend donner aucune approbation ni improbation aux opinions émises dans les thèses ; ces opinions sont considérées comme propres à leurs auteurs.

REMERCIEMENTS : Merci à ma famille :

Maman Malika Serroukh, A celle qui a souffert depuis mon existence pour devenir ce que je suis. Je lui dois tout.

Papa Larbi Marsou et à son héritage marsiouiche.

Wafaa MARSOU ou EL KAISSI ? A son rôle de deuxième mère.

Hafssa MARSOU ma sœur que l'avenir te couvre de bonheur. On est là pour t'aider pour les moments difficiles.

Mariame MARSOU la vie est devant toi, je te redécouvre. Je ne crains pas ce que peut te réserver l'avenir, tu sauras tout affronter.

Abdel Ali MARSOU mon petit frère qui n'a pas écouté mes conseils de ne pas choisir médecine mais sa réussite me ravit. J'espère être là pour t'accompagner.

Soulaiman MARSOU mon petit frère qui me vend du rêve avec son enthousiasme et ses projets. Quand est ce qu'on part à vélo traverser l'Europe ? A quand la traversée du Maroc en mobylette ? Youness MARSOU mon dernier petit frère qui grandit dans les bras de tous tes grands frères et sœurs qui te gâtent un peu trop ! A nos soirées sur la sta7 !!

Wième, Salman, Mohammed petit, Houssam, Lokman, Yiad, Sarah et Lina mes neveux, pour votre beauté et votre amour

Moustapha et Outhman, mes grand frères, la vie a eu raison de votre éloignement

Merci à mes beaux frères Mohammed à ton humour et ton soutien, à Ali et à ton humour également Merci à ma belle sœur Latifa

Merci Muriel SALVAT, et à ton aide dans la réalisation de ce projet et de cette thèse. Merci pour ta franchise et pour ton intolérance à l'imperfection. Merci pour ton soutien pour cette dernière ligne droite.

Merci à l’aide du professeur Gilles Barone-ROCHETTE pour la réalisation de cette thèse.

Merci à Julie MURAT sans qui cette thèse aurait été incompréhensible tellement elle était infestée de fautes d’anglais !!!

Merci à mes professeurs et à tous ceux qui ont pris leur temps de m'enseigner la cardiologie.

Merci à tous ces médecins avec qui j'ai travaillé au CHU de Grenoble de la cardio du 8°B en passant par le 8°C, la chirurgie cardiaque, l'USIC et l'HDJ. A l'équipe de la rythmo où j'ai fait mon premier stage, où clairement j'étais trop jeune pour apprendre la rythmologie.

Merci Pierre Vladimir Ennezat pour la transmission de votre savoir. Merci Hélène Bouvaist pour votre soutien moral.

Merci Marion Maurin, Charlotte Casset et Caroline Augier. Merci Carole Saunier aussi drôle qu'époustouflante.

Merci Aude Boignard aussi douce que rigoureuse.

Merci aux médecins du CH Annecy Genevois et Médipôle Savoie où les équipes sont formidables de par leur motivation et leur expertise.

Claire et Caroline. Que de moments inoubliables drôles ou glauques dans les cavernes des offices A, B, C ou D ! Et mes chers cointernes : Cécile, Flore, Dysmas, Nicolas, Arnaud, Enzo, Florian, Thibaud.

Merci aux équipes infirmières et aides-soignantes sans qui ces 4 années d'internat auront été tristes. Merci à l'équipe de l'USIC : Raphaelle, Grégoire et ses bonbons Haribo...

Merci particulièrement à Souhaila. Tant pis si on me reproche ma préférence ! Promis je ferai une roqia !

Merci à l'équipe infirmière (Christine, Sarah, Béatrice, Marcelle...) de la consultation et de l'HDJ : Marie Yvonne, Nathalie, Souhaila, Mélanie, Christelle qui me permettent de passer mon dernier semestre dans la bonne humeur.

Je passe maintenant à mes cointernes :

Merci particulièrement à Léa Margerit, plus qu'une cointerne, ma voisine de chambre à l'internat de Chambéry. J'aimerai que la vie t'offre plus ce qu'elle ne t'a déjà donné.

Merci à Lisa Periollat et à ce dernier semestre qui nous permet enfin de travailler côte à côte. On se reverra sur le lac d'Annecy sur un bateau en topless ! Merci pour ta droiture et ton soutien psy !! Merci à Marjorie Canu et à ton célibat qui nous a permis de partager un hiver haut en ski. Merci pour ton amitié sans concessions.

Merci à Lauriane Gonzalez et à ton soutien au cours de mon 4eme semestre. Merci Adrien Carabelli et à ta gentillesse sans égal.

Merci à tous les autres et à tous ces moments partagés autour d'une pizza au Hasard, au week end au palace de Menthon Saint Bernard, et à Courchevel.

Merci à tous ces petits coups de main pendant toutes ces heures passées dans les services.

Dédicace spéciale au club des antisociales, elles se reconnaitront ahahaa !!! Faut peut être songer à mettre à jour la photo du groupe. Elle est ( je suis ) horrible ! A nos soirées tisanes-chocolat !!! Je vous adore. A bientôt aux Deux Alpes !

Et merci pour vos chéris à toutes les deux parce qu'on parlait quand même souvent d'eux !

Merci à ma copine lyonnaise Samira et à ton soutien sans faille, ainsi qu'à mes copines parisiennes : Najla Boujaddaini qui nous a réuni et qui m'a initié au selfie^^, Sirine Ghammour à ta douceur, ta tolérance, et à notre trek dans les Alpes, Meriem Ouslim, Meriem Alaya, Sara Lahlou, Nawel Boumediene. Une véritable histoire d'amour qui traverse les frontières, l'espace et peut être la vie?!

Merci à mes amies montpelliéraines de l’externat: Sultan Akcimen et Nadia Ouzzin. Sultan, ma chérie d'amour comme tu aimes bien le dire. J'espère avoir plus d'occasions pour te voir. Merci pour ces longues discussions téléphoniques qui nous permettent de maintenir la flamme de notre amitié malgré la distance.

Audrey Bringer, Audrey Chambelland, Claire Fournier, Julie Armengaud, Charlyne Bel, Marie Azoury, Alphane Baquerre, Anne Sophie Granié même si vous n'êtes pas là ce jour.

Mes amours de cœur :

Liza Sakoun, merci pour tous ces moments, on a traversé notre internat et grandi ensemble.

Alison Rousselle, merci pour tous ces moments hauts en couleur sinusoidale. Reste comme tu es. J'espère que ta nouvelle vie à Chambéry te rendra heureuse.

Camille Ton Van et à nous boucles d'oreilles majorquis. Je pique ta place à Lille ! Merci à ta famille pour leur acceuil chaleureux à Lille, fidèle à l'esprit du nord.

Emeraude, je te découvre tardivement, mais merci pour ces longues discussions.

Yohan, merci pour ta tablette de chocolat, venu au meilleur moment. Je veux que la vie t'offre son meilleur visage sous le plus belle lumière. A toi de l'attraper et de la contempler.

A la troupe népalaise :

Lisa Martinet, Mike, Tonton, Cousin et Bridget

Vous avez été des compagnons de grande qualité. Merci de m'avoir fait découvrir la haute montagne et de m'avoir fait confiance. A bientôt pour un nouveau trek.

Maintenant à mes co-internes/copains du 1er semestre de l'internat et à tous ces moments festifs : Yohan Walch, Gauthier Courtois, Morgan Heitz, Anne Bonifacio, Laurent Seyler, Davy Benhamou, Charles-Dysmas Peyret, Marie Soula, Marine Buiche, Joris Prévost, Audrey, Nicolas, Hubert Gheerband, Anne Sophie , Marion, Eliott, Frédéric Richard, Marion Pla, Julien Hilion, Giovanni, Sarah Aubanel, Arthur Z, Camille Tronc.

Merci Claire Jouzier pour nos runnings dans le bois de l'internat d'Annecy et à la Bastille et à toutes ces longues discussions sur nos vies.

Mes colocataires du roof top cours Gambetta : Aurélie Bros, Marine Buiche, Paulo Deschamps Merci pour votre soutien. A quand le dîner de cons ?

Mes colocataires de l'avenue Jean Perrot : Nicolas, Camille, à votre bébé et à votre mariage ! Mes colocataires du super appart de la place notre Dame

Antoine, Julie, Gabrielle, Vivien et Miguel qui m'ont supporté durant la dernière ligne droite. Une vraie famille d'adoption. Nos repas vont bien me manquer là haut dans le Ch'Nord.

Julie, je te remercie encore. Désolée pour mon absence dans la participation des tâches ménagères depuis cet été. Promis je me rattraperai !

Je vous adore ! Merci de ce que vous êtes et d'être parmi mes proches. Mes voisins et mes cointernes de Chambéry :

Margaux Lacroix devenue amie, on s'est suivi à Annecy. A Gaspard le plus beau bébé de l'internat !!!!

Assia, ma voisine de palier !! Je t'embrasse.

Thibault Allain, Eve, Noémie, Grégoire, Pierre Jean, Nicolas

Merci aux gignols de Malaga, on a bien rigolé, souvent de moi d'ailleurs... J'oublierai pas !! Merci à Yaelle et à la famille César, à ces repas partagés, à votre simplicité et à votre sympathie.

J'en oublie probablement ; il est si difficile de mettre sur papier toute la gratitude que j'ai pour toutes les personnes qui ont traversé mon internat. Merci de ce que vous êtes, merci encore. Certains d'entre vous ne sont malheureusement que de passage dans ma vie. D'autres j'espère resteront dans ma vie. J'ai pris un peu ou beaucoup de chacun de vous. Je garde le souvenir de chacuns de ces moments que nous avons partagés. J'ai appris l'esprit de la camaraderie. Je suis ce que vous m'avez transmis.

ABBREVATIONS AND ACRONYMS: ACE Angiotensin-converting-enzyme AF Atrial Fibrillation

ARB Angiotensin II receptor blockers

BB Beta Blockers BMI Body Mass Index CAD Coronary artery disease

COPB Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease CVD Cardiovascular Disease

DBP Diastolic Blood Pressure HB Heartbeat

HF Heart Failure HR Hazard Ratio LV Left Ventricular

LVEF Left Ventricular Ejection Failure

NYHA New York Heart Association SAS Sleep Apnea Syndrom SBP Systolic Blood Pressure WHO World Health Organization

PRONOSTICS PARAMETERS OF DEATH IN HEART FAILURE FOR A PROSPECTIVE UNIVERSITY GRENOBLE ALPES HOSPITAL COHORT

RÉSUMÉ :

INTRODUCTION : L’insuffisance cardiaque est un problème majeur de santé publique. Les modèles prédictifs de risque de mortalité sont peu performants dans la pratique clinique quotidienne car les données de ces modèles sont issues d’études ou de registres où les populations sont différentes de la réalité du terrain car plus jeunes et moins co-morbides.

METHODE : Nous avons étudié la population hospitalisée pour insuffisance cardiaque au centre hospitalier universitaire de Grenoble Alpes sans critères d'exclusion afin d'étudier les facteurs pronostiques. Les patients inclus pouvaient consulter les urgences ou être hospitalisés directement dans un service de médecine ou de réanimation. Les données démographiques, cliniques, biologiques, thérapeutiques et le type de cardiomyopathie étaient recensés de manière prospective. Le pronostic à 1 an était recueilli.

RESULTATS : 235 patients ont été inclus du 21 novembre 2016 au 21 février 2017 dont 75% de femmes (135). L'âge moyen était de 80,3+/- 12,5 ans. La fraction d’éjection du ventricule gauche moyenne était de 47.7+/-16.9% dans le groupe survivant et 48+/-17.7% dans le groupe non survivant. La mortalité à un an était de 36% (n= 86). La prise en charge en service de cardiologie n'influençait pas le pronostic. Un poids supérieur à 70kg et un taux bas de NT proBNP étaient associés à un meilleur pronostic. L'Odd Ratio était de 0,97[0,96-0,98], p<0,0001 et de 1,89[1,15;3,09] p=0,01 respectivement.

CONCLUSION : Le poids, le pourcentage de masse maigre et le statut nutritionnel sont des paramètres à intégrer dans la prise en charge des patients insuffisants cardiaques âgés au sein d'une équipe multidisciplinaire comprenant des spécialistes de l'insuffisance cardiaque, de la nutrition et de la gériatrie.

MOTS CLÉS key words : heart failure, risk factors, overweight, elderly, obesity paradox FILIÈRE : Cardiologie et maladies cardiovasculaires

INTRODUCTION :

Heart Failure (HF) is a major public health problem in western countries. Its prevalence is about 1-2% (1). The incidence approaches 5 to 10 per 1000 people per year (2). Incidence and prevalence rise steeply with age, especially after 60 years old (2). The Hillingdon study found that in people aged 45 to 55 years old, HF incidence is 0,2/1000, and increases to 12,4/1000 after 85 years old (4). In comparison, the Rotterdam study identifies an incidence of 2, 5/1000 for people aged 55 to 64 years old, and 44/1000 after 85 years old (5).

Despite drug treatments available in HF to avoid hospital admission and reduce morbidity and mortality, HF prevalence and mortality seem to remain high (1). The mortality rate is about 24.4% for age 60 and 54.4% for age 80 at 5 years follow-up, frequently due to non-cardiovascular causes (54.3% of cases), and does not decline over time (3). Clinical characteristics of patients with heart failure have changed in the last decades. Indeed, cases of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction have increased in the last 30 years. It is known that drug treatments lack efficiency in reducing mortality for this type of HF (6).

A large number of studies have investigated mortality risk factors. Many prognostic markers of death and/or HF hospitalization have been identified and a few prediction models exist (7-11). But they haven’t been implemented in the real practice. They are complex to use in conventional ward. And most of studies used to create models are clinical trials whose population is different from real life in- patients. Indeed, they were younger, with a higher proportion of males, suffering more from coronary artery disease (CAD), and had less comorbidities. So, more knowledge was needed to help physicians and patients in real life.

Our team wanted to explore prognostic parameter of death with a cohort of patients coming to Grenoble-Alpes University Hospital with all types of HF and without exclusion criteria.

METHOD:

This is an prospective epidemiological study run at Grenoble-Alpes University Hospital in France. Our goal is to be as exhaustive as possible in order to have a realistic picture of the kind of patients admitted for acute heart failure and their management, from the beginning at the emergency ward to their discharge.

We selected all adults who consulted the emergency, or/and were hospitalized in cardiac or non-cardiac ward, cardiology Intensive Care Unit or resuscitation service for acute heart failure. The emergency file codes were: breathlessness, chest pain, impaired general condition, leg oedema, pulmonary oedema, heart failure, congestive heart failure and cardiogenic shock. Patients admitted in other wards were selected by doctors of those wards. All files were read twice by two different doctors: an emergency or a specialist doctor and a cardiologist from the study. The diagnosis of heart failure was checked and deduced by the patients' natural history, clinical exam, biology, treatments and response to treatments. The definition of Heart failure used is that of the recommendations of the ESC (1): a clinical syndrome characterized by typical symptoms caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality, resulting in a reduced cardiac output and or elevated intra cardiac pressures at rest or during stress. The heart failure could be not the only diagnosis. The diagnosis of heart failure can be accompanied by other conditions. It can be a second diagnosis and not the main reason for the admission. We include all acute heart failure, cardiogenic shock, new onset or decompensated chronic heart failure, reduced heart failure and preserved heart failure. The period of inclusion was from November 21st 2016 to February 21st 2017.

Population:

Demographic datas of the patients were collected: age, sex, weight at the entrance, during hospitalization, and at discharge, height, the heart parameters at the admission (heart rate (HR), systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP), Left Ventricular Ejection Failure (LVEF), the

type of heart failure: dyspnea, cardiogenic shock or increase of leg edemas.

We researched the etiology of the acute heart failure (sepsis, atrial arrhythmias, ventricular arrhythmias, hypertensive crisis, non compliance to medication, anemia, idiopathic heart failure acute valvular heart disease, acute coronary disease, other), comorbidities (Atrial Fibrillation (AF), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Bronchitis (COPD), diabetes, Sleep Apnea Syndrome (SAS), High blood pressure, dyslipidemia, CAD in family history), previous history of heart failure, pharmacological treatments (Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACE), Beta Blockers

(BB), Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), Ant aldosterone, diuretics, insulin, oral anti diabetic treatment), previous hospitalization for heart failure one year prior, the type of cardiovascular disease: ischemic heart disease, structural valvular heart disease, hypertensive cardiopathy, rhythmic heart disease, dilated heart disease, and non-explored heart disease and others. All datas were researched on their medical files.

Etiologies, comorbidities, cardiomyopathies, drug treatment when non described on the files were suggested by the patient's history, biology and drug treatments. For example, patients were listed as diabetic if it was written on their medical files, or deduced from their treatments, or from their HbA1C.

We collected the time ( date and the hour) of admission, the ward where there were admitted : cardiac ward, non-cardiac ward, resuscitation or intensive care unit, discharge or death and the date of death in hospital. . We also collected biology (creatinine, hemoglobin, natremy, urea, Nt proBNP at the admission and the discharge, troponin, glycaemia, HbA1C, albuminemia) at the time of the admission to hospital. All these datas are available in the patients' digital medical files. The software used at Grenoble University Hospital is Cristalnet.

At year 1, we called each and every patient from the cohort. If they didn't answer despite several calls, we called their family if their contact details were known, or their general practitioners. We collected their vital status, possible death causes, hospitalizations (for cardiac or non-cardiac causes) and the date of the last news. When precise date of death was unknown, we chose the first

day of the month when they died.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 21, SPSS Corp, Somers, NY). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± one standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages. Baseline characteristics of patients according to death were compared using a Chi2 or an unpaired t-test. The index date was the date of hospitalization for heart failure. All clinical parameters were proposed for inclusion in a univariate Cox proportional hazard model and all significant (p < 0.05) univariate correlates of survival were entered into forward stepwise multivariate Cox model. Survival of patients with weight according to death was evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared among groups using log-rank test. All tests were 2-sided and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS:

Patients’ characteristics:

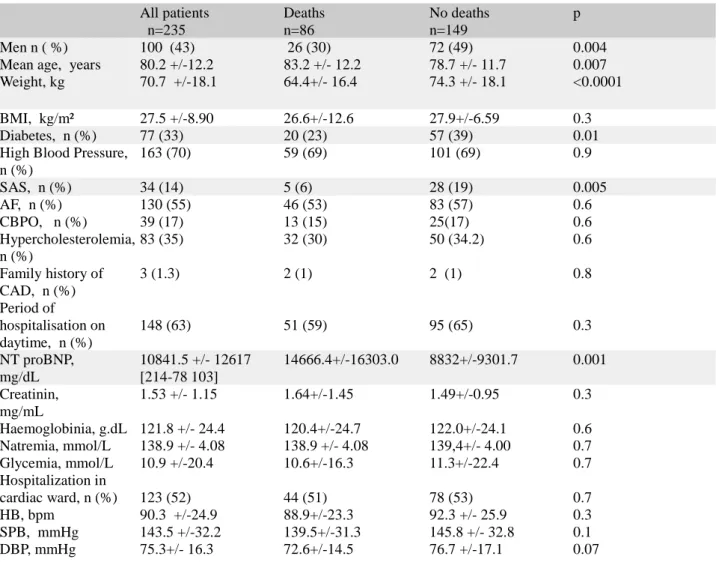

We included a total of 235 patients from 21th November 2016 to 21th February 2017. The demographic characteristics are described in table 1.

Fifty seven per cent were women, 43% were men. The mean age was 80.2 years old. The mean LVEF was 47,8+/-16,9%. There were 86 (36.5%) deaths at one year. 2 patients were out of reach because they had changed residences. The mean weight was 70.7 kg and the mean BMI 27.5kg/m². 77 (33%) were diabetic, 163 (70%) had high blood pressure, 34 (14%) had SAS, 130 (55%) had AF, 39 (17%) COPD, 83 (35%) dyslipidemia, 60 (25%) were investigated for ischemia.

cardiomyopathies associated with AF, 13 (5%) dilated cardiomyopathies, 44 (12%) non explored cardiomyopathies. There were 40 (17%) patients treated at the admission by ACE inhibitors, 26 (11%) by ARB, 95 (40%) by BB, 148 (63%) by diuretics, and 12 (5%) by anti-aldosterone. There were 55 (23%) patients treated at the discharge by ACE inhibitors, 56 (6%) by ARB, 129 (54%) by BB, 181 (77%) by diuretics, and 27 (11%) by anti-aldosterone.

Prognosis

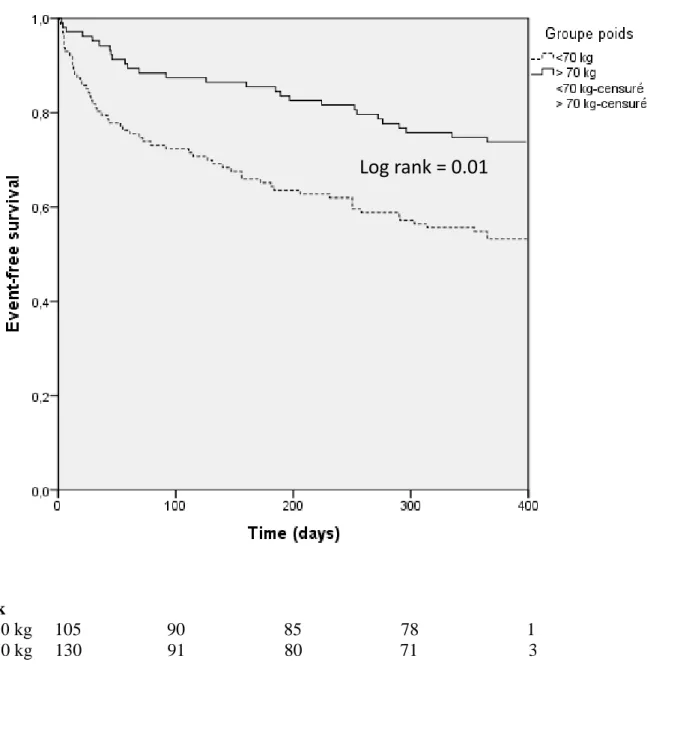

In the surviving group, the mean left ventricle ejection fraction was 47.7 +/- 16.9%, whereas patients who did not survive had a mean left ventricle ejection fraction of 48+/- 17.7 %. No statistically significate difference was observed (p=0.9). The characteristics of patients with and without MACEs are given in Table 1. Significant differences in weight were observed between patients with and without death (p≤0.0001). In univariate analysis, age, sex, SAS, diabetes, weight and Nt-proBNP appear predictor of death. In multivariate analysis, low weight and Nt proBNP were independent predictors of death (HR 0.98 [0.97; 1.00], p=0.04 and HR 1.69 [1.04; 2.74] p=0, 03, repectively. Table 2 shows Uni- and Multivariate Cox Analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival curves according to average weight in the cohort are shown in Figure 1.

DISCUSSION:

In our analysis, NT proBNP and weight are strong independent risk factors of mortality in the elderly admitted to hospital for HF. A high NT proBNP at the admission and a weight under of 70 kilograms seem to yield a poor prognosis.

BNP and NT proBNP are strong independent risk factor of mortality and other cardiac outcomes after acute heart failure and also in chronic heart failure according to the 2016 European guidelines

for diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. The published literature shows that BNP and NtproBNP are associated with all-cause mortality and composite outcomes in both decompensated and chronic stable HF populations and no superiority one against other (12) (13). The OPTIMIZE-HF registry (14) shows the discharge natriuretic peptide had the best performance and was the most important characteristic for predicting 1-year mortality (hazard ratio [HR] for log transformation 1.34; 95% CI 1.28–1.40) and 1-year death or rehospitalization (HR 1.15; 95% CI 1.12–1.18). Moreover, natriuretic peptides are superior on clinical parameters to provide information on mortality. Compared with a clinical variables only model, the discharge BNP model improved risk reclassification and discrimination in predicting mortality and rehospitalization (1-year mortality: NRI 5.5%, P<0.0001; IDI 0.023, P<0.0001; 1-(1-year mortality or re hospitalization: NRI 4.2%, P<0.0001; IDI 0.010, P<0.0001).

It is relevant that obesity is an independent risk factor of heart failure (15-16). In a study of 5,881 patients, the risk of HF increased 5% in men and 7% in women for every 1 kg/m2 increment in BMI during a 14-year follow-up (17). But when heart failure is known, overweight and obesity are associated with better prognosis than underweight or normal weight: it is named the Obesity Paradox. (18-21)

Obesity and overweight are definite in The World Health Organization (WHO) as “an abnormal or excessive fat accumulation.to the extent that health may be impaired.” And no universal cutoffs to diagnose overweight or obesity have been well established. The commonly used parameters are BMI with cutoff >30kg/m² suggested by the WHO.

Many studies have explored that paradox. In a meta-analysis of 9 observational HF studies (n 28,209) in which patients were followed up for an average of 2.7 years, Oreopoulos et al. showed that compared with individuals without elevated BMI, overweight and obese HF patients had reductions in CV (19% and 40%, respectively) and all-cause (16% and 33%, respectively) mortality(22). Likewise, in an analysis of BMI and in-hospital mortality for 108,927 decompensated

HF patients, higher BMI was associated with lower mortality (23).

Studies that explore the effect of weight loss reinforce that's paradox. For instance, in the study Weight Loss in Obese Patients With Heart Failure which gathered 1000 patients, weight loss was associated to higher mortality even though it was significantly adjusted for age, sex, BMI, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, LVEF, HF duration, ischemic etiology, diabetes, and treatment : HR 1.89 [95% CI 1.32–2.68], P<0.001) (24).

On the contrary, losing weight through exercise confers protection against mortality in cardiovascular disease (25).Studies assessing mortality based on body fat and lean mass rather than BMI or weight alone have suggested that subjects losing body fat rather than lean mass have a lower mortality (26, 27). This suggests that sarcopenia is the real mortality predictors. Indeed, cachexia and malnutrition are independent predictors of increased mortality in heart failure (28).

Many studies have proposed different explanation. The first hypothesis is the inaccuracy of the BMI in characterizing the severity of obesity. Most studies exploring the obesity paradox have used BMI to evaluate fat mass. In recent studies however, the improvement of survival on HF patients with a BMI over 30kg/ m² could not be verified when the Vo2 max is corrected on the fat mass. This suggested that Vo2max corrected on lean mass and VO2/VCO2 are most predictive (29) (30). In fact, fat doesn’t consume oxygen or receive substantial perfusion. This suggests that BMI is probably not the best to assess fat mass. Oreopoulos et al demonstrated that BMI classifies 40% of patients with HF in the wrong group (31). Many studies have researched others parameters to evaluate excess fat mass predicting on mortality mainly hip and waist circumference. But currently, no superiority of those over BMI has been proved for the prediction of incident (32).

Based on the previous findings, it would be reasonable to assume that higher amounts of lean mass exert protective effects in patients with HF. A retrospective analysis of more than 47,000

patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction reported a significant protective effect of lean mass in predicting all-cause mortality, regardless of BMI or fat mass (33). An initial analysis of this study suggested that higher BMI and fat mass were associated with lower mortality. When adjusted for lean mass index (kg/m2), however, these associations were not supported, therefore suggesting that the protective component of high body weight and BMI was not fat mass but lean mass (34).

However, those hypothesis are not supported by the next studies. A small study of 209 patients with chronic systolic HF had shown that both higher BMI and percent body fat ( calculated on the average of thigh, chest and abdomen in men and thigh, triceps and suprailiac in women) were independent predictors of better event-free survival (35). Preliminary data in nearly 1,000 patients with systolic HF also showed the prognostic impact of body fat on total survival (36).

The mechanisms by which obesity protects HF patients while inducing diastolic dysfunction and increasing the risk of HF remain unclear. In obese patients, there are hemodynamic abnormalities and structural cardiac changes: LV ( Left Ventricular) end-diastolic, right atrial pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure increase (37-38) central blood volume and stroke volume increase and induce increasing cardiac output. This leads to an initial LV dilation followed by a compensatory LV hypertrophic or concentering remolding without hypertrophy (39, 40). But it seems to be lean mass increase blood volume and cardiac output. The correct definition of lean mass is the sum of bone mineral mass, skeletal muscle mass, and residual mass (18) . The hypothesis of the obesity paradox is based on the fact that the increasing of cardiac output lead to improvement cardiorespiratory fitness, performance and outcomes in HF (18).

Furthermore, adipose tissue is an active endocrine organ able to synthesize many pro inflammatory cytokines participating/contributing in diastolic dysfunction such as IL 1b, TNF alpha and IL 18. CRP and leptins which were associated with increased risk of major cardiovascular events are also more produced in obese patients (41, 42). On the contrary, adiponectin an

adipocyte-specific cytokine connected with increased risk of CV events decrease in conditions such as obesity (43) (44). In addition, obese patients secrete various others cytokines and neuroendocrine which may be protective such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptors which may neutralize the adverse biological effects of tumor necrosis factor overexpressed in HF(45). Moreover, higher circulating lipoproteins in obese patients may bind and detoxify lipopolysaccharides that play a role in stimulating the release of inflammatory cytokines, all of which may serve to protect obese HF patients (46).

A recent study suggests that obesity create microcirculation dysfunction and structural microcirculation dysfunction mediated by inflammatory response induced by high level of fat. Endothelium cells produced endothelium factors which both influence smooth muscle tonus and are influencing by hormonal factors like insulin and sympathic nervous system. When they balance to capillary vasoconstriction, it induce chronic hypoxia and so microcirculation alteration and organ dysfunction in obese persons. But that not explain completely the favorable impact of obesisty in survival. (47).

An other study proposed a possible role of endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) dysfunction. In obesity, relatively deficiency of adiponectin and omentin which are able to attenuate reparative effects of peripheral tissues including myocardium and endothelium was found and improve angionesesis and neovascularization. Late outgrowth EPC, one of two type of EPC exhibit a protective impact on the endothelium mediating by proliferation and having the ability to promote angionesesis and collateral vessel growth. Increased adipocytes size is hypothesized to signal the recruitment of late outgrowth EPCs. In metabolically healthy obese individuals with HF the number of EFC in the circulation is frequently increased or near normal contrary in metabolically non healthy obese patients. (48) . The causative role of progenitor cells dysfunction in obesity paradox is now intensive investigation.

Others explanations were proposed: advanced HF is a catabolic state end obese patients with HF may have more metabolic reserve (49). Additionally, overweight and obese patients with acute and chronic HF have lower levels of circulating atrial natriuretic peptides (50). Furthermore, obese patients with HF may have attenuated sympathetic nervous system, renin-angiotensin responses (51). And as result, they consult earlier ad not at the end stage.

Our population is aging (mean age 80 years old) whereas most of studies exploring prognostics parameters have a younger population. Datas about patients' height is lacking due to old age because they have lost height or they bent and calculating their BMI was impossible. Decreased physical activity and decreased energy expenditure with ageing predispose to fat accumulation and fat redistribution, but muscle loss, so BMI may not increase with adiposity. Two study suggested that BMI is also not the best parameters to evaluate fat mass in elderly due to the impossibility to calculate BMI and proposed to use waist circumference(52) (53). Our study suggests that the elderly admitted for an acute heart failure with a weight under 70 kilograms have a poor prognosis. The weight parameter is very easy and quick to use in clinical practice to screen patients with poor prognosis. Further studies should compare weight, BMI and others anthropometrics parameters in elderly in exploring their lean mass. It suggests that elderly with weight over 70kg shouldn't lose weight but should even gain some in a rehabilitation programs..

It's unexpected that diabetes appears to be protective of all-cause mortality on the univariate analyses on our study. It's well known diabetes is associated with developing heart failure and high mortality when HF is known (54-55). Sleep Apnea Syndrome is also associated with better prognosis in our study although it is associated with a worse prognosis in HF in studies (56) (57). But when diabetes and SAS were adjusted on the weight, the association disappears. The link between SAS and obesity is well established: obesity predisposes to SAS and their prevalence

increases with the obesity epidemic. The prevalence of SAS is even higher in obese patients with diabetes mellitus (58).

Strengths and limitations

Our local cohort is exhaustive. We didn't define exclusion criteria. We included all patients admitted for HF whatever the etiology, comorbidities, or the ward where they were admitted to. It reflects the real life cohort of in patient with heart failure. It shows that the real population admitted for heart failure is older than cohorts in most studies exploring mortality risk factor after heart failure. The mean age of our patients is 80 years old, whereas in the main studies the mean age is between 65 and 70years old. This leads to wonder about its possible application to all studies for HF.

We choose a hard end point: all causes mortality that occurred for 36% of patients. Moreover, we had few loss of view (only two).

The scope of our study wasn’t limited by a significant number of events. This doesn’t bear a risk of overfitting in multivariable models.

However, our sample is small because it only covers one health centre for a relatively short period of time: 3 months.

Because our study is observational, the collected parameters are not complex. We have observed that 48% of patients admitted for heart failure had not benefited from an echocardiography. and when the act was performed the reports were brief. We met the same limitations with many of the collected clinical parameters because some of them were incomplete like albumin and pre albumin which could assess the nutritional status. Incomplete data make the follow up difficult. We don't explore the discharge Nt pro BNP because of lacking datas. Indeed, 67 discharge Nt proBNP were available.

In our study, we only collected information about cardiovascular disease and associated disease like COPB or SAS. We didn't take into account co morbid conditions and others histories like

evolutive cancer which could be the origin of mild weight gain, which is more often the case in older adults. This may constitute a bias in our study.

We know that patients with HF must be managed by HF team with close collaboration between HF practitioners (primarily cardiologists, HF nurses and general practitioners) and other experts, pharmacists, dietitians, physiotherapists, psychologists, palliative care providers and social workers. Older HF patients management is complicated by cognitive impairment, frailty and limited social support. The elderly specifies is frailty which is more common in those with HF (59). Frailty can be evaluated by a frailty score including walking speed (gait speed test), timed up-and-go test, PRISMA 7 questionnaire, Frail Score (60), Fried Score (61, 62) and Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). The nutritional state is included in their evaluation. So, their management requires additional geriatricians in order to take their specificities into account with closer contact between the specialised HF team.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, our study claim that being overweight and having a low admission NT proBNP are strongly associated with great prognosis on heart failure in the elderly. It is important to integrate the weight, and particularly the ratio of lean mass and the nutritional state of the care of older patients with HF admitted for HF. This suggesting the importance of encouraging close work between HF teams (included primarily cardiologists, HF nurses and general practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, physiotherapists, psychologists, palliative care providers, social workers) and geriatricians in specialised unit for older adults.

APPENDIX

Table 1 : Baseline characteristics of patients with and without deaths All patients n=235 Deaths n=86 No deaths n=149 p Men n ( %) 100 (43) 26 (30) 72 (49) 0.004 Mean age, years 80.2 +/-12.2 83.2 +/- 12.2 78.7 +/- 11.7 0.007 Weight, kg 70.7 +/-18.1 64.4+/- 16.4 74.3 +/- 18.1 <0.0001 BMI, kg/m² 27.5 +/-8.90 26.6+/-12.6 27.9+/-6.59 0.3 Diabetes, n (%) 77 (33) 20 (23) 57 (39) 0.01 High Blood Pressure,

n (%) 163 (70) 59 (69) 101 (69) 0.9 SAS, n (%) 34 (14) 5 (6) 28 (19) 0.005 AF, n (%) 130 (55) 46 (53) 83 (57) 0.6 CBPO, n (%) 39 (17) 13 (15) 25(17) 0.6 Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) 83 (35) 32 (30) 50 (34.2) 0.6 Family history of CAD, n (%) 3 (1.3) 2 (1) 2 (1) 0.8 Period of hospitalisation on daytime, n (%) 148 (63) 51 (59) 95 (65) 0.3 NT proBNP, mg/dL 10841.5 +/- 12617 [214-78 103] 14666.4+/-16303.0 8832+/-9301.7 0.001 Creatinin, mg/mL 1.53 +/- 1.15 1.64+/-1.45 1.49+/-0.95 0.3 Haemoglobinia, g.dL 121.8 +/- 24.4 120.4+/-24.7 122.0+/-24.1 0.6 Natremia, mmol/L 138.9 +/- 4.08 138.9 +/- 4.08 139,4+/- 4.00 0.7 Glycemia, mmol/L 10.9 +/-20.4 10.6+/-16.3 11.3+/-22.4 0.7 Hospitalization in cardiac ward, n (%) 123 (52) 44 (51) 78 (53) 0.7 HB, bpm SPB, mmHg DBP, mmHg 90.3 +/-24.9 143.5 +/-32.2 75.3+/- 16.3 88.9+/-23.3 139.5+/-31.3 72.6+/-14.5 92.3 +/- 25.9 145.8 +/- 32.8 76.7 +/-17.1 0.3 0.1 0.07

Table 2. Uni- and Multivariate Cox Analysis Predictors of all-causes mortality after an acute heart failure at one year.

Univariate Analysis Multivariate Analysis

Parameters OR [95% CI] P value HR [95% CI] P value Sex male 1.79 [1.13;2.84] 0.01 1.1 [0.85; 1.42] 0.46 Age 1.03 [1.00; 1.05] 0.01 1.01 [0.98;1.03] 0.38 Weight 0.97 [0.96; 0.98] <0.0001 0.98 [0.97;1.00] 0.04 BMI 0.97 [0.93; 1.01] 0.17 Diabetes 0.54 [0.33; 0.89] 0.02 0.73 [0.43;1.25] 0.26 Hypertension 0.99 [0.52; 1.57] 0.97 SAS 0.31 [0.12;0.72] 0.01 1.42 [0.88; 2.26] 0.13 AF 1.06 [0.69;1.62] 0.77 CBPO 1.06 [0.79;1.42] 0.68 Hypercholesterolemia 0.99 [0.79;1.23] 0.92 Family history of CAD 1.17 [0.43;3.1] 0.7

Care on daytime 0.83 [0.54;1.28] 0.41 Log NT proBNP 1.89 [1.15;3.09] 0.01 1.69 [1.04;2.74] 0.03 Creatinin Haemoglobinia Natremia 1.14 [0.96;1.35] 0.99 [0.98;1.00] 0.99 [0.94;1.05] 0.1 0.5 0.88 Hospitalisation in cardiology ward 0.90 [0.59;1.38] 0.54 SBP HB DBP 0.99 [0.98;1.00] 0.99 [0.98;1.00] 0.98 [0.97;1.00] 0.21 0.36 0.07

Figure 1 : Kaplan Meyer

Log rank = 0.01

No. At Risk

Weight ≥ 70 kg 105 90 85 78 1 Weight < 70 kg 130 91 80 71 3

REFERENCES :

1. Ponikowski P et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failureThe Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 14 juill 2016;37(27):2129-200.

2. Mosterd A, et al. Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. Heart. sept 2007;93(9):1137-46.

Gerber Y et al. A Contemporary Appraisal of the Heart Failure Epidemic in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2000-2010. JAMA Intern Med. 1 juin 2015;175(6):996-1004.

Cowie MR, et al. Incidence and aetiology of heart failure; a population-based study. Eur Heart J. 1999 Mar 20(6):421-8.

A. Mosterd et al, The prognosis of heart failure in general population The Rotterdam Study

European Heart Journal (2001) 22, 1318–1327

6. Owan TE, et al. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 20 juill 2006;355(3):251-9.

7 Ouwerkerk W et al. Factors Influencing the Predictive Power of Models for Predicting Mortality and/or Heart Failure Hospitalization in Patients With Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 1 oct 2014;2(5):429-36.

8. Pocock SJ, et al. Predicting survival in heart failure: a risk score based on 39 372 patients from 30 studies. Eur Heart J. 14 mai 2013;34(19):1404-13.

9. Rahimi K, et al. Risk Prediction in Patients With Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 1 oct 2014;2(5):440-6.

10. Lupón J, de Antonio M, Vila J, Peñafiel J, Galán A, Zamora E, et al. Development of a Novel Heart

11. Dariush Mozaffarian, et al. Prediction of Mode of Death in Heart Failure The Seattle Heart Failure Model. Circulation Heart failure. 24 juill 2007;392-398.

12. Mark Oremus et al. A systematic review of BNP and NT-proBNP in the management of heart failure: overview and methods. Heart Failure Reviews 2014; 19:413-19

13. P. De Groote et al. B-type natriuretic peptide and peak exercise oxygen consumption provide independent information for risk stratification in patients with stable congestive heart failure. JACC. 43(9):1584-89.

14. Fonarow GC, et al. Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF): rationale and design. Am Heart J. juill 2004;148(1):43-51.

15. He J, et al. Risk Factors for Congestive Heart Failure in US Men and Women: NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Arch Intern Med. 9 avr 2001;161(7):996-1002.

16. N.F. Murphy1, et al. Long-term cardiovascular consequences of obesity: 20-year follow-up of more than 15 000 middle-aged men and women (the Renfrew–Paisley study). European Heart Journal. 2006;(27):96–106.

17. De Divitiis O, et al. Obesity and cardiac function. Circulation. 1981; 64(3):477-482.

18. Salvatore Carbone, et al. Obesity and Heart Failure: Focus on the Obesity Paradox. Mayo Clin Proc 2017;92(2. 2017;266-79.

19. Lavie CJ, et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: Risk Factor, Paradox, and Impact of Weight Loss. J Am Coll Cardiol. 26 mai 2009;53(21):1925-32.

20. Lavie CJ, et al. Obesity and heart failure prognosis: paradox or reverse epidemiology? Eur Heart J. 1 janv 2005;26(1):5-7.

21. Lavie CJ, et al. Impact of Obesity and the Obesity Paradox on Prevalence and Prognosis in Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 1 avr 2013;1(2):93-102

22. Oreopoulos A, et al. Body mass index and mortality in heart failure: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2008 Jul;156(1):13-22

23. Alpert MA, et al. Severe Obesity and Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: New Insights Into Prevalence and Prognosis. JACC Heart Fail. 2016 Dec;4(12):932-934

24. Elisabet Zamora, et al. Weight Loss in Obese Patients With Heart . 2016 Mar 24;5(3) :e002468.

25. Rossignol P, et al. Loss in body weight is an independent prognostic factor for mortality in chronic heart failure: insights from the GISSI-HF and Val-HeFT trials. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(4):424-433

26. Allison DB, et al. Weight loss increases and fat loss decreases all-cause mortality rates: results from two independent cohort studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1999;23:603–11.

27. Lavie CJ, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: risk factor, paradox, and impact of weight loss. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:1925–32.

28. Anker SD, et al. Wasting as independent risk factor for mortality in chronic heart failure. Lancet 1997;349:1050–1053.

29. Osman AF, et al. The incremental prognostic importance of body fat adjusted peak oxygen consumption in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:2126–131.

failure. Am J Cardiol 2004;93:588–593.

31. A. Oreopoulos, et al Association Between Direct Measures of Body Composition and Prognostic Factors in Chronic Heart Failure. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(7)609-617.

32. Loehr LR, et al. Association of multiple anthropometrics of overweight and obesity with incident heart failure: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(1):18-24.

33. De Schutter A, et al. Body composition and mortality in a large cohort with preserved ejection fraction: untangling the obesity paradox. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(8):1072-1079.

34. Alpert MA, et al Obesity and heart failure: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Transl Res. 2014;164(4).

35. AF, Milani RV, Mehra MR. Body composition and prognosis in chronic systolic heart failure: the obesity paradox. Am J Cardiol 2003;91:891– 4.

36. Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Artham SM, et al. Does body composition impact survival in patients with advanced heart failure (abstr). Circulation 2007;116:II360.

37. Kasper EK, et al. Cardiomyopathy of obesity: a clinicopathologic evaluation of 43 obese patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70(9):921-924.

38. Friedman SE, Andrus BW. Obesity and pulmonary hypertension: a review of pathophysiologic mechanisms. J Obes. 2012; 2012: 505274.

39. Owan TE, et al. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355(3):251-259.

40. Forbes GB, et al. Lean body mass in obesity. Int J Obes.1983;7(2):99-107.

human adipose tissue. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(8):875-888.

42. Ballak DB, et al. IL-1 family members in the pathogenesis and treatment of metabolic disease: focus on adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance. Cytokine.

2015;75(2):280-290.

43. Arita Y, Kihara S, Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:79–83.

44. Pischon T, Plasma adiponectin levels and risk of myocardial infarction in men. JAMA. 2004; 291:1730–1737.

45. Mohamed-Ali V, et al. Production of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors by human subcutaneous adipose tissue in vivo. Am J Physiol 1999;227:E971-5.

46. Rauchhaus M, Coats AJS, Anker SD. The endotoxin–lipoprotein hypothesis. Lancet 2000;356:930–3.

47. Oana Sorop et al, T.The microcirculation: a key player in obesity-associated cardiovascular disease Cardiovascular Research (2017) 113, 1035–1045

48. Alexander E Berezin, obesity paadox in heart failure: the possible role of progenitor endothelial cell dysfunction Cell Dev Biol 2017,6:1

49. Kalantar-Zadeh K, et al. Reverse epidemiology of conventional cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:1439–44.

50. Mehra MR, et al. Obesity and suppressed B-type natriuretic peptide levels in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:1590–5

51. Lavie CJ, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: risk factor, paradox, and impact of weight loss. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:1925–32.

52. Han TS, et al. Obesity and weight management in the elderly : a focus on men. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013 ; 27 : 509-25.

53. Bastien M, et al . Overview of epidemiology and contribution of obesity to cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2014 ; 56 : 369-81.

54. Bertoni AG, Hundley WG, Massing MW, Bonds DE, Burke GL, Goff DC. Heart failure, prevalence, incidence, and mortality in the elderly with diabetes. Diabetes Care. mars 2004;27(3):699-703.

55. Riet EES van, Hoes AW, Wagenaar KP, Limburg A, Landman MAJ, Rutten FH. Epidemiology of heart failure: the prevalence of heart failure and ventricular dysfunction in older adults over time. A systematic review. Eur J Heart Fail. 18(3):242-52.

56. Khayat R, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and post-discharge mortality in patients with acute heart failure. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1463–1469.

57. Nakamura S, et al. Impact of sleep-disordered breathing and efficacy of positive airway pressure on mortality in patients with chronic heart failure and sleep-disordered breathing: a meta-analysis. Clin Res Cardiol 2015;104:208–216

58. Foster GD, et al. Sleep AHEAD Research Group. Obstructive sleep apnea among obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009; 32:1017–9. [PubMed: 19279303]

59. Vida’n MT, et al. FRAIL-HF, a study to evaluate the clinical complexity of heart failure in nondependent older patients: rationale, methods and baseline characteristics. Clin Cardiol 2014;37:725–732.

60. Turner G, et al. Best practice guidelines for the management of frailty: a British Geriatrics Society, Age UK and Royal College of General Practitioners report. Age Ageing 2014;43:744– 748.

61. Woo J, et al. Comparison of frailty indicators based on clinical phenotype and the multiple deficit approach in predicting mortality and physical limitation. J Am Geriatr Soc

2012;60:1478–1486.

62. Fried LP, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–M156.