How IMET Your Mother:

Revisiting Foreign Military Training, Human Capital, and Coup Risk

Theodore McLauchlin Lee J. M. Seymour Université de Montréal

Abstract

How does foreign aid in the form of military training impact civil-military relations in recipient states? Savage and Caverley (2017) find that US

foreign military training alters the balance of power between recipient state militaries and their governments, doubling the risk of a military coup.

Despite data constraints that limit their analysis to just two training programs, and obvious concerns about selection effects and endogeneity, the result has been cited as evidence that US training increases coup propensity. Employing new and updated data on the full range of US military training programs, we find this effect limited to a single training program, IMET, and thus unrepresentative of the vast array of US training.

Our results have implications for foreign aid, civil-military relations, and the design of foreign military training programs.

Paper for the American Political Science Association, San Francisco, September 10-13, 2020

Introduction

How does foreign aid in the form of military training impact civil-military relations in recipient states? Despite dramatic increases in the funding for security force assistance and military training over the past two decades, we know relatively little about how aid in the form of military training

impacts the politics of recipient states. In the absence of reliable, validated, and replicable findings, researches and policy-makers have extrapolated patterns on the basis of anecdotal data, country case studies, and

quantitative work based on small samples of training relationships and programs.

Here, we replicate the findings of Savage and Caverley (2017),

scrutinizing the reported association between US military training and coup d’états in recipient states. The Savage and Caverley data cover only the International Military Education and Training (IMET) program and the Counterterrorism Fellowship Program (CTFP). But these are just two of well over thirty programs military training and represent 14% of total training expenditures and 11% of trainees in the period 1999-2016. To address this shortcoming, we draw on an original dataset of US foreign military training

from 1999-2016, IMTAD-USA. Can we replicate their findings using

comparable data? Do the findings apply to other programs? What can we say, more generally, about the relationship between foreign military training and civil-military relations in recipient states? And how should this inform training programs, which have grown globally in scale and scope, to reduce potential harms for recipient states and societies?

While our findings replicate their main finding for the increased coup risks associated with the IMET program, we find that this relationship fails to hold for other US training programs. The absence of significant

relationships between US military training and coups holds even when we use the disaggregated nature of our new data to search for evidence of their hypothesized human capital mechanism. If there is a link between training and coups it appears to be concentrated in one program, though an

important one, yet the causal mechanism seems not to operate in other programs. These findings have important implications for the emerging literature on security assistance and the study of civil-military relations, in addition to the design and implementation of military training.

Foreign Military Training and Civil-Military Relations in Recipient States

A recent review of the literature on civil-military relations concluded that far more work needs to be done on the dynamics of security force

the form of military training on the civil-military relations of recipient countries. Some scholars see training as a beltway for transmitting liberal norms of democracy, civilian control and military professionalism (Atkinson 2006, 2014; Ruby & Gibler 2010; Joyce 2020). Others see inherent dangers in bolstering the capacities of foreign militaries. Recently, Savage and Caverley (2017) underscored the inherent risks of training foreign militaries. They hypothesize that aid in the form of military training increases the military’s “human capital” in ways that shift the balance of power between the military and the regime:

We use ‘human capital’ to describe a range of social, instructional, and economic assets. The benefits consist in part of professional knowledge… enabling recipients to conduct military operations more effectively. FMT can also impart a more ineffable form of ‘social capital’… establishing a powerful network of prestige, trust, and reciprocal relations that allow privileged actors to achieve higher status positions” (545).

Indeed, their study finds that militaries receiving US training are twice as likely to launch a coup despite the explicit emphasis on human rights and civil-military relations in the International Military Education and Training (IMET) program they examine. Further, given IMET’s emphasis on civilian control, Savage and Caverley speculate that other US programs that place comparably less emphasis on such norms could increase coup risk even more.

There are serious limitations to their research design, however, most notably the fact that they study just two of the 34 programs under which US training takes place and the selection effects inherent in the non-random assignment of US training to both partner countries and to the foreign officers selected to participate in such programs. Notwithstanding these limitations, the study has been cited by scholars, journalists and

policymakers as evidence of the dangers of US military training programs (e.g. Turse 2017, Economist 2019, Böhmelt et al. 2019, Dieng 2019), most recently with the coup of August 2020 by U.S.-trained officers in Mali (e.g. York and Chase 2020).

To replicate this study, we begin with a simple replication of their analysis of the two programs they examine—IMET and CTFP—using

originally-collected and updated data, and extend this analysis over the full gamut of 34 US foreign military training programs. Our much wider range of data allows us to assess Savage and Caverley’s claim that IMET’s focus on norms transmission make it an “easy case” for spreading norms of military professionalism that reduce the likelihood of coups, and thus their hunch that the relationship they uncover for IMET should hold for other training programs.

In a second step moving beyond straightforward replication, we gain empirical leverage by exploiting the disaggregated nature of our data to search for further evidence of the hypothesized mechanisms linking US training to the increased capacity and willingness of officers participating in

training to launch coups. We focus on three program characteristics that could plausibly increase coup propensity through a human capital

mechanism. The impacts of training on the human capital of the military generally, and its officer corps in particular, is emphasized on Savage and Caverley (2017) as well as Böhmelt et al (2019) and Grewal (2020). First, because IMET and CTFP concentrate on the mid-level and senior officers most frequently implicated in coups, we examine the observable implication that training programs with an officer focus should increase coup risk. Second, building on the observation that training in the United States confers authority and prestige to officers and facilitate coordination by placing officers beyond the reach of intelligence and security services, we examine training that takes place in the United States versus training abroad. Here we build on Grewal (2020), who finds that Tunisian military officers studying in the US were “politicized” relative to counterparts that received training in France, transmitting the increasing partisanship among US officers to contexts where civil-military relations are less stable and less institutionalized. Finally, to further examine Savage and Caverley’s claim that IMET represents an “easy case” for reducing coup propensity because of its focus on liberal norms transmission, we examine whether programs with different objectives have different associations with coup propensity.

H1a: Participation in IMET increases a country’s military-backed coup probability.

H1b: Participation in CTFP increases a country’s military-backed coup probability.

H2: Participation in US military training programs increase a country’s military-backed coup probability.

H3: Participation in US military training focused on officers increase a country’s military-backed coup probability.

H4: Participation in US military training that takes place in the United States increases a country’s military backed coup probability.

H5: Participation in US military training that has improving democracy, civil-military relations, or governance increases a

country’s military-backed coup probability less than military training that is not focused on these objectives.

Data & Methods

Detailed, disaggregated data has been a key obstacle to better

understanding the effects of security force assistance on the incidence of coups. Savage and Caverley rely on publicly available data for two US programs, using IMET between 1970-2009, and including the CTFP from 2003 in a pooled analysis. Yet these programs represent a small fraction of overall US military training. Employing IMTAD-USA, our far more

comprehensive dataset on US military training between 1999 and 2016 (McLauchlin and Seymour 2020), we are able to replicate their analysis for

IMET, CTFP and 32 other programs through which the US offers military training to foreign forces.

To probe for further evidence of their human capital mechanism we include data on whether training focuses on officers (by examining three further programs beyond IMET and CTFP: training via service academies; Regional Centers for Security Studies; and professional military exchanges); and data on the location of training (whether it occurs in the US or abroad). All data are taken from the IMTAD-USA dataset (McLauchlin & Seymour 2020).

Otherwise, we fully reproduce Savage and Caverley’s modeling decisions: their choice of dependent variable, the probability of a military backed coup; the same control variables, including years since the last coup, military aid, non-military aid, total aid, years since last coup, affinity for the US, spending per soldier, military personnel, coup-proofing,

democracy, GDP per capita, economic growth, oil revenue, coup-proofing, civil war, terrorist attacks, regime age, empowered ethnic groups, Cold War and post-2001 dummies.1 We also run logit models with cubic polynomials for duration since last coup, and their use of Amelia and multiple imputation to account for missing data. Savage and Caverley examine numerous

measures of training: a dummy variable indicating that any number of students were trained, total students, total expenditures, five-year rolling averages, and logged versions of each. We use the annual number of

1 For a discussion of these controls and the relevant measures, see Savage and Caverley 2017, pp 549-550.

students and expenditures, and the five-year average of expenditures. The human capital mechanism implies that longer-run training relationships should be more likely to produce coups d’état, because the longer the duration of training, the more meaningful an impact it can have on human capital. For all of these hypotheses, then, we should expect that the sum of training in the previous five years (one of Savage and Caverley’s key

indicators) should be more strongly related to coups d’état than the previous year’s training total. Lastly, like them, we use standard units.

Results

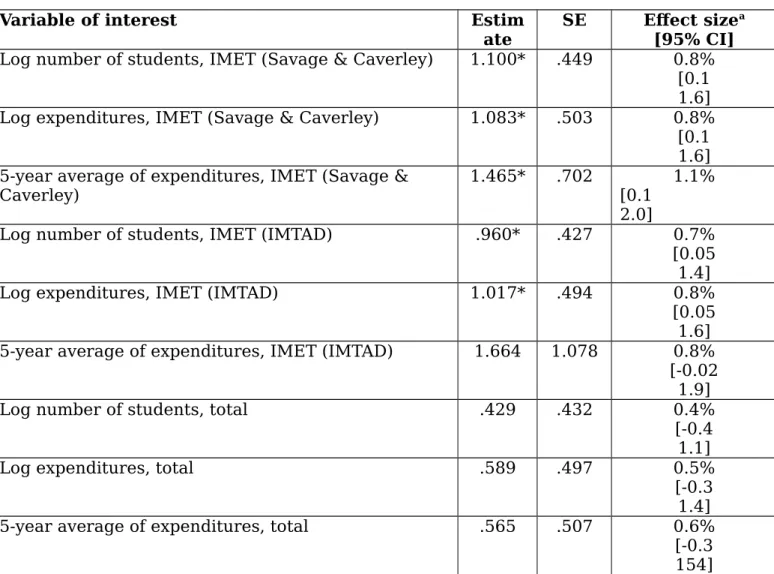

With multiple different replications examining different aspects of the training-coup relationship, here we report only the relationship between a given training measure and the incidence of coups, but the full suite of control variables is in place in each model. Overall replication results are given in Table 1. Because our data cover a different time period (1999 to 2009; the years 2010 through 2016 are eliminated because Savage and Caverley’s own data stop in 2009), we first assess whether Savage and Caverley’s results, with their own training measures, hold for the 1999 to 2009 period. For IMET—their key result—they do (with the partial exception of the five-year average of expenditures, whose standardized coefficient is larger but, with our data, less reliably related to coups). This at least suggests that differences in the results are not entirely due to changing timeframes and gives us some initial confidence that it is not, for example,

a Cold War artifact in which the United States was particularly active in sponsoring and approving coups.

Table 1. Overall replication results

Variable of interest Estim

ate

SE Effect sizea

[95% CI]

Log number of students, IMET (Savage & Caverley) 1.100* .449 0.8% [0.1 1.6]

Log expenditures, IMET (Savage & Caverley) 1.083* .503 0.8%

[0.1 1.6] 5-year average of expenditures, IMET (Savage &

Caverley) 1.465* .702 [0.1 1.1%

2.0]

Log number of students, IMET (IMTAD) .960* .427 0.7%

[0.05 1.4]

Log expenditures, IMET (IMTAD) 1.017* .494 0.8%

[0.05 1.6]

5-year average of expenditures, IMET (IMTAD) 1.664 1.078 0.8%

[-0.02 1.9]

Log number of students, total .429 .432 0.4%

[-0.4 1.1]

Log expenditures, total .589 .497 0.5%

[-0.3 1.4]

5-year average of expenditures, total .565 .507 0.6%

[-0.3 154] a Effect size is change in predicted probability of a coup associated with a

one-standard-deviation change in each variable

Aggregating across all 34 programs, however, there appears to be no statistically significant relationship between the total number of students, or expenditures on training, and the incidence of coup attempts. There is also a substantial reduction in effect sizes (calculated using the Margins command in Stata on one of the five multiply-imputed datasets). It is thus not as though we can conclude that the aggregate of US training

expenditures supports coup attempts. One could, however, argue that a substantial amount of this aid is unlikely to impact civil-military relations in host states, and thus dilutes effects limited to a smaller group of programs.

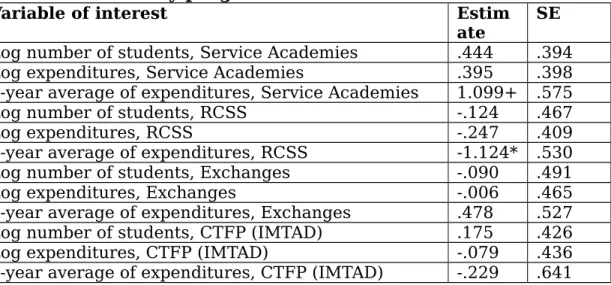

Table 2. Results by program

Variable of interest Estim

ate SE

Log number of students, Service Academies .444 .394

Log expenditures, Service Academies .395 .398

5-year average of expenditures, Service Academies 1.099+ .575

Log number of students, RCSS -.124 .467

Log expenditures, RCSS -.247 .409

5-year average of expenditures, RCSS -1.124* .530

Log number of students, Exchanges -.090 .491

Log expenditures, Exchanges -.006 .465

5-year average of expenditures, Exchanges .478 .527

Log number of students, CTFP (IMTAD) .175 .426

Log expenditures, CTFP (IMTAD) -.079 .436

5-year average of expenditures, CTFP (IMTAD) -.229 .641

To account for this possibility, we focus on programs with several features comparable to IMET that should impact coup propensity. First, we examine programs focused on officer training, namely the Service

Academies, Regional Centers for Security Studies, and professional military exchanges. Here, however, we find no strong association for subsets of training programs in which the training-coups relationship should, by the causal mechanism of Savage and Caverley’s theoretical logic, be especially strong. For one other program—exchanges through service academies— there is a positive relationship that is significant at the .1 level, for the 5-year rolling average. There is a negative relationship, statistically

significant for the 5-year rolling average, between training at the Regional Centers for Security Studies and coups. There is no statistically significant relationship between training and coups for any other officer-focused

program other than IMET – not even for CTFP considered on its own (table 2). For this program in particular, it is worth highlighting Savage and

Caverley’s procedure, which never considered CTFP on its own, but only a figure consisting of IMET + CTFP trainees and expenditures. It is

reasonable to conclude that the positive relationship between this figure and coups was being driven by IMET alone.

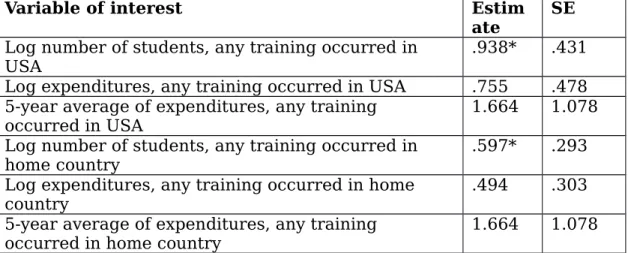

Table 3. Results by location of training (IMET only)

Variable of interest Estim

ate

SE

Log number of students, any training occurred in USA

.938* .431

Log expenditures, any training occurred in USA .755 .478 5-year average of expenditures, any training

occurred in USA 1.664 1.078

Log number of students, any training occurred in

home country .597* .293

Log expenditures, any training occurred in home

country .494 .303

5-year average of expenditures, any training

occurred in home country 1.664 1.078

Second, it is not clear that there is a meaningful difference between training in the US and training elsewhere, in spite of Savage and Caverley’s claim that training in the US increases officers’ prestige so as to help them rally other officers for a coup. This hypothesis, it should be noted, is tested only on a subset of the data. The details of training, including the location and the recipient-country units trained, are not fully declassified for each country; for some they remain classified, and for others they are just not recorded even if other training details are. However, for the remaining 70% we are able to code locations of training. In the original FMTR documents from which our IMTAD-USA data were coded, these locations are given for each training course; rather than the labor-intensive task of coding all of these, we simply recorded whether any training occurred in the US, the recipient country, or a third country in a given program in a given year, and then multiply these dummy variables by number of trainees and

IMET, since this is the only program for which there is a clear relationship. Here, the coefficient is larger for training taking place in the US than training taking place in the home country, but this difference is not statistically significant.

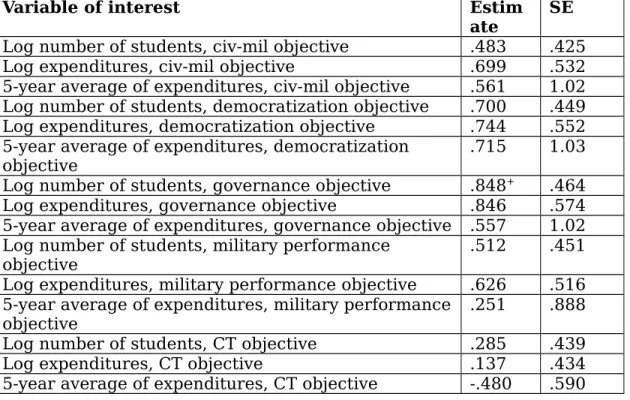

Table 4. Results by program objective

Variable of interest Estim

ate

SE

Log number of students, civ-mil objective .483 .425

Log expenditures, civ-mil objective .699 .532

5-year average of expenditures, civ-mil objective .561 1.02 Log number of students, democratization objective .700 .449

Log expenditures, democratization objective .744 .552

5-year average of expenditures, democratization

objective .715 1.03

Log number of students, governance objective .848+ .464

Log expenditures, governance objective .846 .574

5-year average of expenditures, governance objective .557 1.02 Log number of students, military performance

objective .512 .451

Log expenditures, military performance objective .626 .516 5-year average of expenditures, military performance

objective

.251 .888

Log number of students, CT objective .285 .439

Log expenditures, CT objective .137 .434

5-year average of expenditures, CT objective -.480 .590

Finally, Savage and Caverley suggest that if training is associated with coups for IMET, this association should travel to other programs because IMET focuses especially on the transmission of liberal norms, more than other programs for which military performance is the overriding goal. Our dataset codes the objectives of training programs. We examined the

description of each program given in the Foreign Military Training Reports to assess whether each program had different objectives: military

performance (nearly universal), counterterrorism, improving civilian control of the military, democratization, and good-governance/anticorruption,

counternarcotics, human rights, and gender equality. Note that these objectives are assessed for the program as a whole, and not on a country-by-country basis. As a consequence, this measure does not perfectly capture

the focus of training for a particular activity or partner. We focus here on the objectives most obviously related to preventing coups—civil-military relations, democratization, and governance. Again, there are no statistically significant differences across objectives. The financing that comes with improved civilian control as an objective does not appear to offset a coup-promoting effect from the fact of training in the first place. If anything, it appears to be the opposite: more politically-oriented objectives seem to have a somewhat stronger relationship with coups than more

military-performance-oriented financing. Again, however, this could be explained by the selection effects of seeking to prevent coup recurrence through security assistance.

In sum, Savage and Caverley, then, may have been on to something. That something, though, appears to principally be a problem with IMET— not, at least as far as we can tell, US training more generally.

Conclusion

Existing research casts doubt on the efficacy of military training (Ladwig 2017, Biddle et al. 2018) and its implications for negative outcomes ranging from human rights (Dube and Naidu 2015) and political violence (Boutton 2019). Scholars have an obligation to pay close attention to transfers of skills to those vested with coercive power in fragile states. Savage and Caverley’s important finding has far reaching implications for security policy and our understanding of how aid impacts civil-military relations.

Using new data, however, our findings provide reasons to challenge the wider applicability of this relationship beyond the IMET program.

Our main result, as well as our inability to validate a human capital mechanism linking training to coup risk, suggests the need to further study how security assistance shapes civil-military relations in recipient states. An obvious question concerns what might be different about the IMET program and why it fails to transmit norms of military professionalism. But first we need to know more about “assignment to treatment,” that is, how training partners are selected to account for the endogeneity and the high likelihood of reverse causality. We also need more nuanced analysis of the conditions in host states, such as Joyce’s (2020) finding that rapid increases in training have negative consequences for the political stability of recipients.

Furthermore, given that multiple training programs and activities occur in many settings, untangling who is doing what, and with what consequences, is an important challenge for future research. Analysis to date has focused on US training, not without reason given the outsized presence of the US security assistance globally. Other countries have

important training programs, however, and there is good reason to suspect these have different objectives. In Mali, for example, the US and EU were quick to cut suspend training programs in Mali in the wake of the August 18, 2020 coup – the second coup d’état by military officers that had received US training in just eight years. While this seems prudent given the

spent the months preceding the coup training in Russia. The increasingly prominent role of other countries in security assistance, US retrenchment, and a more multipolar world all underscores the need to know much more about transnational training relationships beyond the US.

References

Atkinson, C. (2006) Constructivist implications of material power: Military engagement and the socialization of states, 1972–2000. International Studies Quarterly 50(3), 509-537.

Atkinson, C. (2010) Does soft power matter? A comparative analysis of student exchange programs 1980–2006. Foreign Policy Analysis 6(1), 1-22.

Biddle, S., Macdonald, J., & Baker, R. (2018) Small footprint, small payoff: The military effectiveness of security force assistance. Journal of Strategic Studies 41(1-2), 89-142.

Böhmelt, T., Escribà-Folch, A., & Pilster, U. (2019) Pitfalls of

professionalism? Military academies and coup risk. Journal of conflict resolution 63(5), 1111-1139.

Boutton, A. (2019). Military Aid, Regime Vulnerability and the Escalation of Political Violence. British Journal of Political Science, 1-19.

Brooks, R. A. (2019) Integrating the civil–military relations subfield. Annual Review of Political Science 22, 379-398.

De Bruin, E. (2018) Preventing coups d’état: How counterbalancing works. Journal of Conflict Resolution 62(7), 1433-1458.

De Bruin, E. (2020) Mapping Coercive Institutions: The State Security Forces Dataset, 1960-2010. Forthcoming.

Dieng, M (2019) The Multi-National Joint Task Force and the G5 Sahel Joint Force: The limits of military capacity-building efforts. Contemporary Security Policy 40(4): 481-501.

Dube, O., & Naidu, S. (2015) Bases, bullets, and ballots: The effect of US military aid on political conflict in Colombia. The Journal of Politics 77(1), 249-267.

Economist (2019) A shooting puts the spotlight on military training for allies. Economist, December 12.

Grewal, S (2020) Politicization Beyond the Water's Edge: The Impact of U.S. Training on the Tunisian Military. Forthcoming.

Joyce, RM (2020) Exporting Might and Right: Great Power Security Assistance and Developing Militaries. PhD Dissertation, Colombia University.

Ladwig III, W. C. (2016) Influencing Clients in Counterinsurgency: US

Involvement in El Salvador's Civil War, 1979–92. International Security 41(1), 99-146.

McLauchlin T and Seymour L (2020) Tracking the rise of United States foreign military training: IMTAD-USA, a new dataset and research agenda. Unpublished manuscript.

Ruby, T. Z., and Gibler, D. (2010) US professional military education and democratization abroad. European Journal of International Relations 16(3), 339-364.

Savage JD and Caverley J (2017) When human capital threatens the capitol: foreign aid in the form of military training and coups. Journal of Peace Research 54(4), 542–557.

Turse, N (2017) The Pentagon Has a Small Coup Problem. The Nation, 11 August.

York, G and Chase S (2020) For second time in eight years, a coup in Mali has been led by a U.S.-trained soldier. The Globe and Mail, 21 August.