Climate as Provocation of Preservation Standards and Procedure in Historic Districts of

the Floodprone U.S.: Lessons from Palm View, Miami Beach

by

Sara Brent McCoy

Bachelor of Arts in Geography

Middlebury College, 2014

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master in City Planning

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

September 2020

© 2020 Sara Brent McCoy. All Rights Reserved

The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly

paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium

now known or hereafter created.

Author________________________________________________________________________

Department of Urban Studies and Planning

August 13, 2020

Certified by____________________________________________________________________

Associate Professor of Urban Design and Planning, Brent Ryan

Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by___________________________________________________________________

Professor of the Practice, Ceasar McDowell

Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Climate as Provocation of Preservation Standards and Procedure in Historic Districts of

the Floodprone U.S.

By Sara Brent McCoy

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on August 13, 2020 in partial

fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning

Abstract

With many historic resources located in coastal, flood-prone environments, much has been

written in the last two decades about the (re)negotiation of local preservation regulatory standards to facilitate adoption and uptake of on-site flood-mitigating measures for low-lying historic

buildings and structures. Though various design guidelines have been developed to facilitate the simultaneous pursuit of climate adaptation and historic preservation, various tensions between the two remain.

This thesis uses as an illustrative case a series of events and conditions in Miami Beach, FL, where residents of a low-lying historic district are seeking to have their district’s historic status revoked, in light of perceived limitations posed by the implications of the designation on their capacity to adapt their homes in response to increasing flood risk. Analyses of interviews with stakeholders in Miami Beach and preservation ordinances across Florida are contextualized by literatures around preservation law, critical conservation, and adaptation decision-making. This thesis suggests that efficient, effective adaptation of historic resources in places like Miami Beach will require a (re)negotiation of not just preservation standards (of appropriateness, integrity, what merits designation) but also procedure, wherein preservation decision-making processes become less expert-driven and more actively account for a greater diversity of community values.

Thesis advisor: Brent Ryan, Associate Professor of Urban Design and Planning, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, MIT

Acknowledgements

Parents, siblings, friends, Johnny! Thank you! For your generous counseling and encouragement. And thank you, faculty, staff, and colleagues at DUSP and GSD for your guidance and book recommendations.

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION

Historically and culturally important places in the United States are increasingly, urgently vulnerable to sea level rise and other coastal effects of climate change, in part due to where we have built1, how we have interpreted historical value2, and how we have tried to keep that value

intact3.

Incentives have been in place since American colonization to build in dynamic, coastal environments -- the places now exposed to sea level rise and “the ongoing increase in the frequency, depth, and extent of tidal flooding”4 that comes with it. To build many an early

American city strategically was to build it in a highly dynamic environment, at the mouth of a big river or near a deep harbor or surrounded by wetlands -- well-connected, resource-rich, or easy to protect from attack5. More recently, over the twentieth century and since, cities and regions

have expanded into areas once deemed too hostile to development6; with the advent of the

modern highway system and the Federal Housing Administration, as well as the federalization of disasters7, coastal and riverine frontlines became beach-towns and tourist destinations. As

dynamic environments’ development potential was tapped, those who had once been displaced to this country’s dynamic fringes were once again pushed out8. On barrier island back bays and fill

emerged quaint exurban getaways and region-defining commercial strips. Today, a large share of the country’s people, jobs, homes, and infrastructure are along the coast9.

The National Climate Assessment defines risk as “the potential for adverse consequences when something of value is at stake, and the outcome is uncertain”10. With many “[somethings] of value

. . . at stake”, cities, regions, and states undertake the work of managing the risk of hazards

1 Grunwald, Michael. The Swamp: The Everglades, Florida, and the Politics of Paradise. Simon &

Schuster, 2007.

2 Frey, Patrice. “Why Historic Preservation Needs a New Approach.” Saving Places: National Trust for Historic Preservation (blog), March 26, 2019.

https://savingplaces.org/stories/why-historic-preservation-needs-a-new-approach.

3 “National Flood Insurance Program Floodplain Management Bulletin: Historic Structures.” FEMA,

May 2008.

4 Fleming, Elizabeth, Jeffrey Payne, William V. Sweet, Michael Craghan, John Haines, Juliette Finzi

Hart, Heidi Stiller, and Ariana Sutton-Grier. “Fourth National Climate Assessment Chapter 8: Coastal Effects.” Washington, DC: U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2018. 323.

5 Davis, Jack E. The Gulf: The Making of An American Sea. Liveright Publishing, 2017. 6 Gaul, Gilbert. The Geography of Risk. New York, NY: Sarah Chrichton Books, 2019. 7 Gaul.

8 Kahrl, Andrew W. The Land Was Ours. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016. 9 Kildow et. al, “State of the US Coastal and Ocean Economies,” 5.

10 Arnold, Jeffrey, Roger Pulwarty, Robert Lempert, Kate Gordon, Katherine Greig, Cat Hoffman,

Dale Sands, and Caitlin Werrell. “Fourth National Climate Assessment,” 2018. https://nca2018.globalchange.govhttps://nca2018.globalchange.gov/chapter/28.

strengthened, sped up, or brought on by the increase in global temperature already ensured11;

they have begun the work of adapting12.

Certainly, the practice of adapting to changing physical environments has taken place for millennia. Hazard planners and geographers have warned of the unsustainable nature of

contemporary development practice given hazard risk and cited a need to counter incentives to build in hazardous areas13 more or less since contemporary development practice began14. But

climate adaptation as a local government practice (the stuff of offices, task forces, plans), or as a practice to study normatively, is fairly new.

Adaptation, per the United States Global Change Research Program, is any “adjustment in natural or human systems to a new or changing environment that exploits beneficial opportunities or moderates negative effects15”. This paper largely refers to proactive adaptation, unless otherwise

noted. Proactive adaptation is, per the National Climate Assessment, is a “suite of actions”16

aimed at managing risk related to climate-related hazards. Actions can range from the technical to the progressive, from the incremental to the transformational,17 with possibilities for adaptation

framed as a continuum18. If climate risk is informed by exposure, sensitivity, and capacity19,

adaptive actions can theoretically address any one or combination of these factors in attempts to manage risk.

On one end of the spectrum, adaptation teams, strategies, and actions might pursue some idea of

11 Brown, Calum, Peter Alexander, Almut Arneth, Ian Holman, and Mark Rounsevell. “Achievement

of Paris Climate Goals Unlikely Due to Time Lags in the Land System.” Nature Climate Change 9, no. 3 (March 2019): 203–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0400-5.

12 Bierbaum, Rosina, Joel B. Smith, Arthur Lee, Maria Blair, Lynne Carter, F. Stuart Chapin, Paul

Fleming, et al. “A Comprehensive Review of Climate Adaptation in the United States: More than before, but Less than Needed.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 18, no. 3 (March 1, 2013): 361–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-012-9423-1. 363.

13 Baker, Earl J., and Joe Gordon McPhee. “Land Use Management and Regulation in Hazardous

Areas - A Research Assessment.” Technical Report. United States Government Printing Office, April 1975. https://tamug-ir.tdl.org/handle/1969.3/27101.

14 White, Gilbert. “Human Adjustment to Floods: A Geographical Approach to the Flood Problem in

the United States.” University of Chicago, 1942.

https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/climate/docs/Human_Adj_Floods_White.pdf.

15 U.S. Global Change Research Program. “Glossary.” GlobalChange.gov. Accessed August 13,

2020. https://www.globalchange.gov/climate-change/glossary.

16 Fleming et. al.

17 Wise, R. M., I. Fazey, M. Stafford Smith, S. E. Park, H. C. Eakin, E. R. M. Archer Van Garderen,

and B. Campbell. “Reconceptualising Adaptation to Climate Change as Part of Pathways of Change and Response.” Global Environmental Change 28 (September 1, 2014): 325–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.12.002.

18 Pelling, Mark. Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation. Routledge,

2010.

continuity, a maintenance of status quo20, an understanding of resilience with roots in

engineering21. Design and implementation of the seawall, the new pump station, or the raised road

can bend toward this goal. These conventional, incremental strategies have commonly taken precedence over more transformational approaches22, and will continue to as “long as capital

protection and accommodation initiatives can be expected to have net benefits within their design lives”.23 Various reasons are cited as to why incremental, conventional action has been largely

preferred -- among them, high short-term, uncompensated costs of transformative actions, some enduring risk uncertainty, and institutional inertia24 -- even as such actions are suggested to be

maladaptive25 in contexts where risks faced are “so sizeable that they can be reduced only by

novel or dramatically enlarged adaptations, the reorganization of vulnerable systems, or changes in their locations”26.

On the other end of the spectrum are these means to transformative/transformational adaptation. Broader conceptualizations and applications position adaptation as an opportunity to reimagine, driven by an understanding of the “current situation [as] undesirable”27, as well as of the ways in

which a community’s sensitivity to climate stressors and events can be informed by underlying inequities and injustices.28 These actions may offer a “dynamic in social-ecological evolution”29;

they may entail a “reconsider[ation of] the social norms and societal values that underlie existing problems.”30 In what are described as transformative adaptation approaches, there may be some

20 Adger, W. Neil, Suraje Dessai, Marisa Goulden, Mike Hulme, Irene Lorenzoni, Donald R. Nelson,

Lars Otto Naess, Johanna Wolf, and Anita Wreford. “Are There Social Limits to Adaptation to Climate Change?” Climatic Change 93, no. 3–4 (April 2009): 335–54.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-008-9520-z. 341.

21 Holling, C.S. “Engineering Resilience versus Ecological Resilience.” In Engineering within Ecological Constraints, edited by P.E. Schulze, 31–43. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press,

1996.

22 Bierbaum, et al.

23 Butler, William H., Robert E. Deyle, and Cassidy Mutnansky. “Low-Regrets Incrementalism: Land

Use Planning Adaptation to Accelerating Sea Level Rise in Florida’s Coastal Communities.”

Journal of Planning Education and Research 36, no. 3 (September 2016): 319–32.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16647161. 329.

24 Kates, Robert W., William R. Travis, and Thomas J. Wilbanks. “Transformational Adaptation

When Incremental Adaptations to Climate Change Are Insufficient.” Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences 109, no. 19 (May 8, 2012): 7156-7161.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1115521109.

25 Barnett, Jon, and Saffron O’Neill. “Maladaptation.” Global Environmental Change 20, no. 2 (May

1, 2010): 211–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.11.004.

26 Kates, 7156. 27 Adger et al, 341.

28 Julius, Susan, Keely Maxwell, Anne Gramsbsch, Ann Kosmal, Libby Larson, and Nancy Sonti.

“Fourth National Climate Assessment.” U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, 2018. https://nca2018.globalchange.govhttps://nca2018.globalchange.gov/chapter/11.

29 Pelling.

30 Wise, R. M., I. Fazey, M. Stafford Smith, S. E. Park, H. C. Eakin, E. R. M. Archer Van Garderen,

element of disruption31; in these cases, in response to stochastic events (like storms) and/or

gradual change (like erosion), a system or a place, becoming more resilient, does not return to its previous state, but rather a more stable alternative state32. Though conventional adaptation

actions are more commonly applied, adaptation projects and grant awards have recently included in their aims more transformational considerations such as the reunification of displaced

community members33, or the diversification of economic opportunities34, not just simply as

co-benefits of adaptation actions but as means towards the end of managing risk, or avoiding it altogether.

Proactive adaptation can entail both/either (anything along the spectrum of) maintenance and/or planned disruption. The process of “[choosing] wisely between alternative strategies for managing change” -- from the more conventional to the transformational -- entails, theoretically, both

“technical analysis and community participation”35. Adaptation planning best practice encourages

a robust participatory process, to determine collective risk tolerance, to map community values and priorities3637. Increased levels of engagement and participation were found to be widely

understood across disciplines as necessary to improving the efficacy of climate change

adaptation as a locally-pursued practice38, an understanding dating back at least to the 1992 Rio

Declaration39 and echoed by the IPCC in 201840.

Change and Response.” Global Environmental Change 28 (September 1, 2014): 325–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.12.002.

31 Clarke, Darren, Conor Murphy, and Irene Lorenzoni. “Place Attachment, Disruption and

Transformative Adaptation.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 55 (February 1, 2018): 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.12.006.

32 Holling.

33 “National Disaster Resilience Competition Grantee Profiles.” U.S. Department of Housing and

Urban Development, January 2016. https://archives.hud.gov/news/2016/pr16-006-NDRCGrantProf.pdf. 9.

34 “National Disaster Resilience Competition Grantee Profiles”, 21.

35 Godschalk, David R., Edward J. Kaiser, and Philip R. Berke. “Integrating Hazard Mitigation and

Local Land Use Planning.” In Cooperating with Nature: Confronting Natural Hazards with Land-Use

Planning for Sustainable Communities, edited by Raymond J. Burby. Washington DC: Joseph

Henry Press, 1998. 97.

36 Carcasson, Martín, and Leah Sprain. “Beyond Problem Solving: Reconceptualizing the Work of

Public Deliberation as Deliberative Inquiry.” Communication Theory 26, no. 1 (February 1, 2016): 41–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12055.

37 Paavola, Jouni, and W. Neil Adger. “Fair Adaptation to Climate Change.” Ecological Economics

56, no. 4 (April 1, 2006): 594–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.03.015.

38 Hügel, Stephan, and Anna R. Davies. “Public Participation, Engagement, and Climate Change

Adaptation: A Review of the Research Literature.” WIREs Climate Change 11, no. 4 (2020): e645. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.645.

39 Hügel and Davies, 2.

40 IPCC. “Global Warming of 1.5C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of

1.5C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustain- Able Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty.” Geneva, 2018. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/.

The importance of participation in informing decision-making is underscored further41 in contexts

where transformational adaptation is understood to be “both possible and necessary”42 – in the

places where conventional strategies alone are not understood to be enough to effectively, efficiently manage risk. Part of the cited value in these contexts of a more thoroughly engaged process is its role in making different interests, values, and forms of knowledge more visible43.

Decision science and frameworks across disciplines highlight the importance of value

transparency44, with critical decision-making requiring an understanding of both “what the various

stakeholders care about and the consequences of the alternatives” 45. In the design and pursuit of

transformational adaptation strategies in particular, when place-related value conflicts exist and are neither articulated nor addressed, adaptation may very well be stalled or ineffective4647. In this

reading, many barriers to adaptation often attributed to other constraints are in fact barriers imposed by conflicts of values48 -- that, as echoed by O’Brien, “values subjectively define the

limits to adaptation as a response to climate change, as much or more so than objective

factors”49. The process of articulating different sets of values, of rules, of knowledge -- of making

them visible through more robust engagement -- despite its messiness and slow pace50, is argued

to be “more likely to lead to robust and defensible decisions”51 than those which do not address

value conflict. In daylighting these subjective limitations, and facilitating these multilateral interactions between values, rules, and knowledge52, perceived conflicts of values and interests

(and the limits they impose) may also be revealed to be not entirely entrenched53.

41 Sprain, Leah. “Paradoxes of Public Participation in Climate Change Governance.” The Good Society 25 (January 1, 2017): 62. https://doi.org/10.5325/goodsociety.25.1.0062.

42 Colloff, Matthew J., Berta Martín-López, Sandra Lavorel, Bruno Locatelli, Russell Gorddard,

Pierre-Yves Longaretti, Gretchen Walters, et al. “An Integrative Research Framework for Enabling Transformative Adaptation.” Environmental Science & Policy 68 (2016): 87–96.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.11.007. 88.

43 O’Brien, Karen L. “Do Values Subjectively Define the Limits to Climate Change Adaptation?” In Adapting to Climate Change: Thresholds, Values, Governance, edited by W Neil Adger, Irene

Lorenzoni, and Karen L O’Brien, 164–80. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

44 Espinosa-Romero, Maria J., Kai M. A. Chan, Timothy McDaniels, and Denise M. Dalmer.

“Structuring Decision-Making for Ecosystem-Based Management.” Marine Policy 35, no. 5 (2011): 575–83.

45 Gregory, Robin, and Ralph L. Keeney. “A Practical Approach to Address Uncertainty in

Stakeholder Deliberations.” Risk Analysis: An International Journal 37, no. 3 (March 2017): 487– 501. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12638. 487.

46 Adger, et al.

47 Clarke, Darren, Conor Murphy, and Irene Lorenzoni. “Place Attachment, Disruption and

Transformative Adaptation.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 55 (February 1, 2018): 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.12.006.

48 Adger, et al. 49 O’Brien, 177.

50 Hügel and Davies, 12. 51 Hügel and Davies, 12. 52 Colloff et al, 91. 53 Adger, et al.

But adaptation decision-making – the process of choosing which suite, which actions, for which contexts -- is fraught with “tensions with other drivers of public governances”54, the delivery of

other, competing public goods55. While land use planning and regulation of the design and

construction of buildings have been and will continue to be key means of adaptation employed by local governments5657, the formal mandates and working objectives of different bodies regulating

land use can and do conflict with, take precedence over, and/or impede adaptation-sensitive land use reform as currently defined, in pursuit of other important social ends, such as cultural

resource or historic preservation58.

Preservation is a practice of identifying and stewarding places and structures deemed to be of such cultural or historical importance as to require an additional layer of regulation, to keep their value intact, the loss of which might otherwise be left unaccounted for in urban development choices. But where landmarks and districts, the domain of preservation, are low-lying or hazard-prone, decisions made by the bodies that regulate them -- about what aspects to preserve, and in what way -- can further inform a places’ exposure, sensitivity, and capacity to adapt59. In other

words, where place disruption may be a necessary part of adaptation60, preservation is a practice

of place maintenance. The tensions between the two are multilateral: Climate exacerbates existing challenges within the field of preservation and presents new ones61. [SOMETHNG ELSE] One

researcher described the 2005 hurricane season as the largest disaster for historic resources in the United States since passage of the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act62.

The particular vulnerability of historic resources – and, importantly, the people who live in historic

54 Hügel and Davies, 12.

55 Conde, Sarah N. “Striking a Match in the Historic District: Opposition to Historic Preservation

and Responsive Community Building.” Georgetown University Law Center, 2007. 38.

56 Bierbaum et.al, 371. 57 Baker.

58 Seekamp, Erin, Sandra Fatorić, and Allie McCreary. “Historic Preservation Priorities for Climate

Adaptation.” Ocean & Coastal Management 191 (June 15, 2020): 105180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105180. 2.

59 Xiao, Xiao, Erin Seekamp, Max Post van der Burg, Mitchell Eaton, Sandra Fatorić, and Allie

McCreary. “Optimizing Historic Preservation under Climate Change: Decision Support for Cultural Resource Adaptation Planning in National Parks.” Land Use Policy 83 (April 1, 2019): 379–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.02.011.

60 Hess, Jeremy J., Josephine N. Malilay, and Alan J. Parkinson. “Climate Change: The Importance

of Place.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Theme Issue: Climate Change and the Health of the Public, 35, no. 5 (November 1, 2008): 468–78.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.024.

61 Rockman, Marcy, Marissa Morgan, Sonya Ziaja, George Hambrecht, and Alison Meadow.

“Cultural Resources Climate Change Strategy.” Washington DC: Cultural Resources, Partnerships, and Science and Climate Change Response Program, National Park Service, 2016.

62 Williams, Joy. 2010. “Historic Tax Incentives As Disaster Relief: A Case Study of Post-Katrina

buildings63 – to coastal flooding and other consequences of climate change and parallel

ecological degradation is broadly recognized64, though more granular assessment of degree of

relative risk in any given location is in some cases are stilled needed65. Historic resources are

those buildings, streetscapes, and other spaces and structures preserved as vestiges of social, aesthetic, technological, and ecological contexts that no longer exist -- near shorelines now eroded, behind buffering landscapes now filled66. Their incompatibility with present and future

environments (and certain market demands or enforceable standards) is in some ways, arguably, a reason for their preservation and regulatory treatment, even as the consequences of climate change make clear that the once-strategic locations where they stand can no longer sustain them as they were originally intended. Of course, at the same time, these resources are arguably protected in part as well because they are compatible with and meet social demands in ways that new construction cannot67, in part because of those same market demands and regulatory

standards that they precede68.

In a short-term understanding of adaptive capacity, of engineering resilience – one more oriented towards immediate resumption69 – the fruits of past and present preservation practice (districts,

landmarks) may very well serve the purpose of grounding, of cohesion70 in recovery from

disruptive events71, in service of a community’s capacity to bounce back. But, in the long term, in

our most vulnerable places, more conflicts may arise between preservation as practiced today and means of transformative adaptation as understood to be needed.

The question of how to mitigate flooding of a historic structure or site without sacrificing its

63 Purdy, Bella. “Resilient, Historic Buildings Design Guide.” City of Boston Environment

Department, August 2018. https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/embed/file/2018-10/resilient_historic_design_guide_updated.pdf.

64 Rockman, et al. 65 Rockman, et al.

66 Poon, Linda. 2016. “Why Protecting Historic Sites Needs to Be Part of Disaster Planning.” CityLab. April 8, 2016.

https://www.citylab.com/equity/2016/04/why-historic-preservation-needs-to-be-part-of- disaster-planning/477318/.

67 “Affordable Housing and Historic Preservation.” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development, October 19, 2007.

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/affhsg/historic_preserv.html.

68 Steinberg, Joachim Beno. “New York City’s Landmarks Law and the Rescission Process.” New York University Annual Survey of American Law 66, no. 4 (April 22, 2011).

69 Holling, C S. “Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4, no. 1 (1973): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245. 70 Aldrich, Daniel, and Michelle Meyer. “Social Capital and Community Resilience.” American Behavioral Scientist 59 (February 1, 2015): 254–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214550299,

6.

71 Appler, Douglas, and Andrew Rumbach. “Building Community Resilience Through Historic

historical or aesthetic integrity is locally specific72 and in most places largely left unanswered73, as

common on-site flood mitigation measures used in newer construction may not be appropriate for, or may come at the expense of the integrity of, designated sites and structures74. Many places

lack norms and guidance in the practice of ensuring that our most culturally significant places are, to whatever degree, able to endure75; their stewards are acknowledged to remain largely

under-supported, technically and financially, in managing risk to preserved districts and structures76.

There is some work underway to see how preservation and adaptation can be renegotiated at the local level, simultaneously pursued, or rendered more compatible. Recent years have seen a ramp-up in the development of adaptation design guidelines for historic properties by states7778

and cities7980, to ask and answer: What might on-site flood mitigation measures that do not

interfere with the building’s spirit, with the details that make it special, but are also sufficiently effective at managing risk, look like? These guidelines are often in conversation with, but

operating on a different timescale from, guidelines for cultural resource disaster planning81, which

72 Eggleston, Jenifer, Jennifer Parker, and Jennifer Wellock. “Rehabilitating Historic Buildings.”

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service, November 2019.

73 Fatorić, Sandra, and Erin Seekamp. “Are Cultural Heritage and Resources Threatened by

Climate Change? A Systematic Literature Review.” Climatic Change 142, no. 1 (May 1, 2017): 227–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-1929-9.

74 Mutnansky, Cassidy. “Adaptation Planning for Historic Properties.” Florida Department of

Economic Opportunity, May 2015.

75 Eggleston, Jenifer, Jennifer Parker, and Jennifer Wellock. “Rehabilitating Historic Buildings.”

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service, November 2019.

76 Sesana, Elena, Alexandre S. Gagnon, Chiara Bertolin, and John Hughes. “Adapting Cultural

Heritage to Climate Change Risks: Perspectives of Cultural Heritage Experts in Europe.”

Geosciences 8, no. 8 (August 2018): 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8080305. 77 Louisiana Office of Cultural Development, Division of Historic Preservation. “Elevation Design

Guidelines for Historic Buildings in the Louisiana GO Zone.” Louisiana Office of Cultural Development, Division of Historic Preservation, 2015.

https://www.crt.state.la.us/Assets/OCD/hp/uniquely-louisiana-education/Disaster-Recovery/Final%20Elevation%20Design%20Booklet%2012-07-15%20v2.pdf.

78 Mutnansky.

79 City of Charleston Board of Architectural Review. “Design Guidelines for Elevating Historic

Buildings,” July 24, 2019. https://www.charleston-sc.gov/DocumentCenter/View/18518/BAR-Elevation-Design?bidId=.

80 Purdy, Bella. “Resilient, Historic Buildings Design Guide.” City of Boston Environment

Department, August 2018. https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/embed/file/2018-10/resilient_historic_design_guide_updated.pdf.

81 Burton, Rebecca. “Change Is Hard: Preserving Florida’s Past in an Uncertain Future.” UF Thompson Earth Systems Institute (blog), July 15, 2019.

have also been developed by or for cities and states over the last two decades82.

The National Park Service released their own broader guidelines for in 201983, offered ultimately

in deference to local authorities to renegotiate standards of significance and appropriateness with standards of adaptation locally, in the legacy of other federal preservation guidance. As in the 1966 Preservation Act, interpretations of appropriateness must be grounded in local context84.

But as with many forms of adaptation85, questions about implementation remain. resources in the

practice of adapting historic resources are limited86, and not all things can be adapted to the

same standard, particularly in environments where the adaptation decision-making timeline is shorter, the threats more emergent87. Different interventions will make sense for different contexts,

so guidelines offer a menu88. Practitioners have acknowledged the need for means of

prioritization89, while researchers have developed and encouraged uptake of prioritization tools90

and decision support frameworks91 -- those which classify properties as suited to certain

interventions based on a variety of economic, social, and structural considerations, as well as risk level92.

Ultimately, however, successful adaptation decision-making in towns and cities where landmarks and districts have a big footprint may require further preservation reform beyond that which could be provided for by the adoption of resilient design guidelines and/or an adaptation decision-making framework.

This thesis looks closely at and uses as an illustrative case a series of events and conditions in

82 Nettles, Belinda, Thomas Ankersen, Thomas Hawkins, Adrienne Burke, and Joseph Pardo.

“Protecting Florida’s History from Hazards: A Guide to Integrating Cultural Resources into Disaster Planning.” University of Florida Levin College of Law, Conservation Clinic, June 2017.

83 Eggleston, et al.

84 National Historic Preservation Act, 16 U.S.C. 470 § 1(1966). 85 Bierbaum, et al.

86Sargent, Liz, and Deborah Slaton. “Heading into the Wind: Climate Change and the Implications

for Managing Our Cultural Landscape Legacy.” Change Over Time 5 (October 1, 2015): 200–224. https://doi.org/10.1353/cot.2015.0017.

87 Urban Land Institute. “Miami Beach Florida Stormwater Management and Climate Adaptation

Review: A ULI Advisory Services Panel Report,” April 16, 2018. https://seflorida.uli.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2018/09/Miami-Beach_PanelReport.pdf.

88 Shulman+Associates. “Buoyant City: Historic District Resiliency & Adaptation Guidelines,”

October 29, 2019. https://www.scribd.com/document/446276756/Buoyant-City-Historic-District-Resiliency-Adaptation-Guidelines.

89 Shulman+Associates. 90 Xiao, et al.

91Fatorić and Seekamp. 92 Seekamp, et al.

Palm View, one of Miami Beach, FL’s thirteen local historic districts93, designated in 199994. A

group of residents in Palm View, per local reporting95, are claiming that they have tried and are

unable to effectively adapt their properties to current and future flood risk because of their neighborhood’s historic district status. They feel that the designation of their district impedes them from being able to adapt their low-lying properties, or to sell them to willing buyers.

Residents pursue de-designation in response, suggesting that they cannot effectively adapt while regulated as a district, and that the costs of not adapting, or delayed adaptation, or adaptation in ways deemed appropriate given district status, are punitive96. The claim rests on the idea that,

given current and future flood risk, the private value proposition on which buyer interest (in buying property within highly regulated environments) once depended -- that the public and private benefits of owning and investing in a preserved property outweighed the financial costs and property right limitations on which, in practice, its preservation depends – erodes. Residents feel they are left with one option: To have landmark status removed, and to allow the sites to be entirely redeveloped, or adapted in accordance with some definition of appropriateness or integrity different from the preservation board’s.

While some initial steps have been taken to address the particular vulnerability of historic properties to flood risk in Miami Beach97, something that, according to one preservation board

member, the city “has been studying for a while now” 98, the concerns raised by the group of

property owners and residents in Palm View point to remaining gaps in the approach.

This case is used to highlight some of the barriers to effective adaptation of historic resources, namely those related to decision-making processes and community involvement. Broadly, this work asks: What about the case of Palm View might prove illustrative, or valuable to understand, in a broader reckoning between standards and procedures of adaptation and preservation? This exploratory work allows for connections to be made between adaptation and preservation decision-making literature and a real-life example; the nature and design of the methods are limited, but they are an early step in illustrating constraints and challenges in Palm View,

contextualized by the literature, so that opportunities for addressing those challenges may start to be teased out. Hopefully, lessons learned through the case of Palm View might find resonance elsewhere.

93 Miami Design Preservation League, “Miami Beach Historic Districts: Historic Architecture

Database”, accessed July 15, 2020.

94 City of Miami Beach Planning Department, “Palm View Historic District Designation Report”. 95 Gurney, Kyra, and Alex Harris. “Can a Miami Beach Neighborhood Preserve Its History and

Protect Itself from Sea Rise?” Miami Herald, May 1, 2018.

https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/miami-beach/article209784439.html.

96 Gurney and Harris. 97 Shulman+Associates.

98 City of Miami Beach. Buoyant City: Miami Beach Historic District Resiliency & Adaptation Guidelines. Miami Beach City Hall, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xkzhfM-h4ig.

The case of Palm View is a helpful one towards these ends because of the direct suggestion by the cited residents that adaptation and preservation, at least as practiced in Miami Beach, cannot be simultaneously pursued. And it is useful case because, in calling for de-designation as a response to a feeling of an impossibility of adapting historic resources while designated, as a means of challenging how preservation is practiced and governed in risky areas, residents of Palm View have the potential to set a precedent for elsewhere -- important for both those

encouraged by and fearful of such a development. While rescission (de-listing, de-designation) is outlined as a possibility and a process in local historic preservation ordinances across the country, it is very rarely successfully pursued99 and, to the author’s knowledge, never explicitly to

these ends. Even beyond the United States, reversal of preservation decisions can be uncommon, while new sites are added to the UNESCO World Heritage list every year, only two have been fully de-listed in the list’s forty-five year history, neither for climate-related reasons100, though climate is

listed as one threat faced by World Heritage Sites included on their list of sites In Danger101. The

Palm View case highlights the potential for the use and/or threat of de-listing as not simply a means of economic relief102 or retribution103 but rather a means of (political pressure for)

regulatory reform, particularly where inclusion on a list of local landmarks is seen as a regulatory barrier to adaptation.

It is also a helpful case because of where it is, Miami Beach, the cultural distinctiveness of which is locally and internationally understood and beloved – and the look-and-feel of which owes much to early preservation successes104. As Miami Beach is regularly invoked as a bellwether of

twenty-first century climate risk and response105, current debates there may offer a preview of those to

be had elsewhere. The region to which it belongs is one of a handful where a combination of climatic, geological, hydrological, ecological, social, and economic forces interact so as to

dispose people and infrastructure there to certain consequences of climate change that are more quickly felt, if not more strongly, than in other urban regions106. Regions like South Florida are

99 Conde, 11.

100 UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “World Heritage List.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

Accessed July 15, 2020.

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/?msg=forgotlogin&order=property&delisted=1

101 UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “World Heritage In Danger.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

Accessed July 15, 2020. https://whc.unesco.org/en/158/

102 City of Benoit WI, Municipal Code of Ordinances 32.10.

103 UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “Arabian Oryx Sanctuary.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

Accessed July 15, 2020. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/654

104 McLendon, Timothy, JoAnn Klein, David Listokin, and Michael L. Lahr. “Economic Impacts of

Historic Preservation in Florida: Update, 2010.” Center for Governmental Responsibility, University of Florida Levin College of Law; Center for Urban Policy Research, Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, 2010.

105 Raimi, Daniel, Amelia Keyes, and Cora Kingdon. “Florida Climate Outlook.” Washington, D.C.:

Resources for the Future, January 2020. https://www.rff.org/publications/reports/florida-climate-outlook/.

already feeling the direct and indirect social and economic effects of – and particularly the exacerbation of existing inequalities and challenges by -- increased tidal flooding and storm exposure, as outlined by the National Climate Assessment107; they will feel next-level effects like

mass out-migration before others108. Places like Miami already, and will continue to, serve to

highlight in practice some of the challenges in adapting to these threats -- proactively, reactively, or a combination of both -- in ways that can inform adaptation elsewhere, where similar effects are forthcoming.

Miami is one of these places because of where it is, but also because of how it was built and continues to be developed. The pretense on which South Florida was built over the last century and a half -- “the central technological myth of our time . . . that nature can not only be tamed but made irrelevant”109 -- unravels as the climate changes. Midcentury investments in coastal

engineering that enabled Miami’s modern history110 were made to harness and protect from a

geological and climatic context that no longer exists. Increasingly, water threatens South Florida from every angle, as shorelines erode and hem in, rains fall harder, and groundwater rises up through the permeable limestone on which cities like Miami Beach are built111.

---

This thesis offers a preliminary assessment of the current state of negotiations between

preservation and adaptation as parallel, complementary, conflicting practices in Miami Beach, in conversation with Weinstein-Berman’s 2016 analysis112 and in response to a call for further

analysis around the interactions between preservation and adaptation decision-making processes113. This research is guided by a few questions:

1. How are the issues in Palm View related to the calls for de-designation being described by different stakeholders? Do barriers to simultaneous preservation and adaptation as described by Palm View stakeholders resonate with barriers described by the adaptation

107 Kildow, et al, 35.

108 Hauer, Mathew E. “Migration Induced by Sea-Level Rise Could Reshape the US Population

Landscape.” Nature Climate Change 7, no. 5 (May 2017): 321–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3271.

109 Goodell, Jeff. “Miami: How Rising Sea Levels Continue to Endanger South Florida - Rolling

Stone.” Rolling Stone, August 30, 2013. https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/miami-how-rising-sea-levels-endanger-south-florida-200956/.

110 Bloetscher, Frederick, Serena Hoermann, and Leonard Berry. “Adaptation of Florida’s Urban

Infrastructure to Climate Change.” In Florida’s Climate: Changes, Variations, & Impacts, by Florida Climate Institute. Florida Climate Institute, 2017. https://doi.org/10.17125/fci2017.ch11.

111 Bloetscher et. al, 316.

112 Weinstein-Berman, Laura Allyn. “The Progression of Historic Preservation in Miami Beach and

the Challenges of Sea Level Rise.” Columbia University, 2017. https://doi.org/10.7916/D8FF44G0.

decision-making literature? What about the Palm View case might prove illustrative, and does it offer potential new dimensions?

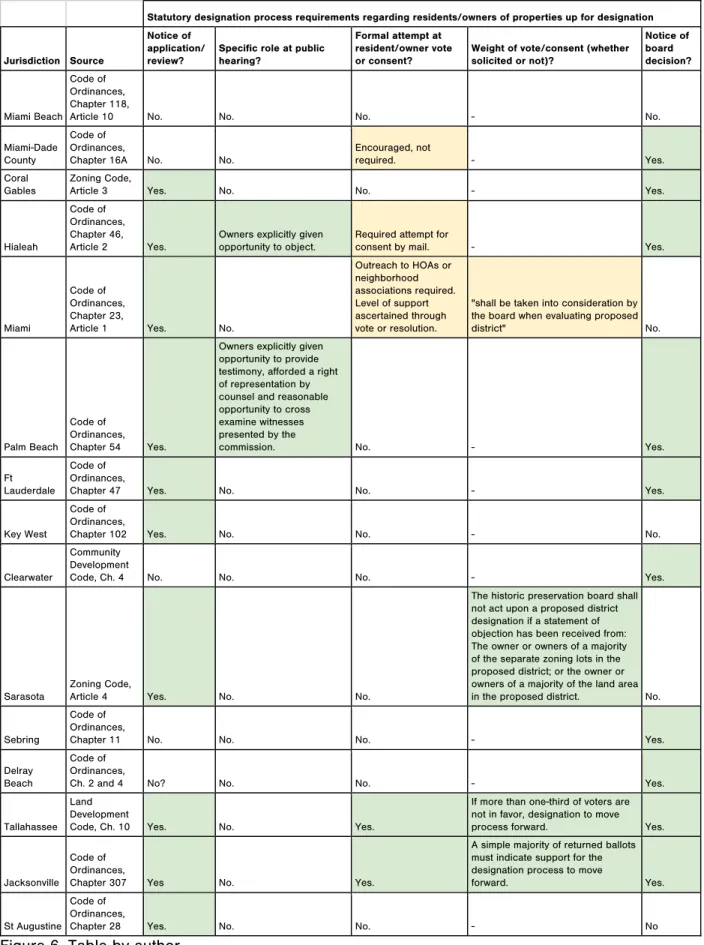

2. For context, How do provisions for community input in the Miami Beach historic designation/de-designation process compare to other provisions regionally, as well as broader national trends? Are there local precedents for greater provisions for community input, under the same state guidance?

3. What are emergent opportunities, and how might frameworks for preservation-adaptation decision-making be applied and amended for the Palm View case?

Methods include semi-structured, cross-disciplinary interviews and a regional comparison of historic preservation ordinances, contextualized by a review of literature around adaptation and preservation decision-making methods and law, and a review of past reports about simultaneous preservation and adaptation in South Florida and elsewhere. This thesis highlights opportunities and hopeful signs for improved preservation-adaptation decision-making in Miami Beach, with implications for elsewhere. What follows is further contextual, historical information about the case of Palm View, Miami Beach, and preservation practice in the United States (Chapter 2); a

presentation of findings from interviews and municipal code analysis (Chapter 3); and a discussion of potential implications and opportunities (Chapter 4).

CHAPTER II:

MODERN PRESERVATION, MIAMI BEACH, PALM VIEW: CONTEXT, BRIEF HISTORIES A Brief, Relevant History of American Preservation, Movement to Practice

Preservation practitioners describe landmarks and districts themselves as public goods114 --

whether for their value as physical reminders which promote something shared or cohesive within a community115, or for an intrinsic value as artistic objects116, or something else. Per the common

definition of a pure public good, landmarked sites and structures would be rival and non-excludable117, the cultural and aesthetic benefits of their existence shared by the public at large,

or at the very least the public that lives near them. Echoes of the similarly timed environmental movement of the mid-late 20th century ring clearly: As with public goods like clean water and air, citizens are seen to lack incentives to undertake stewardship of landmarks with “the optimal level of care”118 as individuals, necessitating government intervention119.

Passage of the Antiquities Act of 1906 and the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 made preservation a matter of federal policy; sites and structures appearing on the resultant National Register of Historic Places are often positioned as some of our most significant, while the National Park Service develops standards and guidelines for preservation at all scales.

But the legal power to protect historic places is ultimately locally conferred120, to municipal and

county preservation commissions or architectural review boards. Charleston, South Carolina passed the country’s first preservation ordinance and designated the first local district in 1931, though its Board of Architectural Review had limited power of enforcement -- to deny demolition, for one -- until 1966, the year that the National Act was passed across the country121. The U.S.

Supreme Court confirmed the local preservation ordinance’s status as an “appropriate means” with its 1978 decision in Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York122. Since 1978, nearly

114 Steinberg.

115 Rose, Carol M. “Preservation and Community: New Directions in the Law of Historic

Preservation.” Stanford Law Review 33, no. 3 (February 1981): 473. https://doi.org/10.2307/1228356. 482.

116 Kaufman, Ned. “Moving Forward: Futures for a Preservation Movement.” In Giving Preservation A History. Routledge, 2004.

117 Samuelson, Paul A. “The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 36, no. 4 (November 1954).

118 Steinberg, 958.

119 Olson, Mancur. The Logic of Collective Action. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1965.. 120 “A Citizen’s Guide to Protecting Historic Places.” National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2002. 121 Weyeneth, Robert R. Historic Preservation for a Living City: Historic Charleston Foundation, 1947-1997. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000.

122 National Trust for Historic Preservation. “Local Preservation Laws.” SavingPlaces.Org.

Accessed May 8, 2020. http://forum.savingplaces.org/learn/fundamentals/preservation-law/local-laws.

2,500 local preservation ordinances have been passed123. The subjects of these ordinances are

locally designated sites and districts, while properties listed on the National Register are sometimes locally regulated through zoning overlays124. This paper focuses on the process of

local designation and stewardship unless otherwise specified.

The local powers of preservation boards and commission include, principally, the power to rule on designations and regulate what are and are not appropriate modifications to historic

properties (including demolition), with the interpretation of what is and is not significant -- which buildings, which features -- understood to be the “central task”125 of the preservation field.

Local re-interpretations of how to apply the federal standards and guidelines developed by the Park Service within designated sites and districts can take the shape of ordinance amendments and informal norms.

Preservation has since its early days been a reactive practice, a response to a threat -- threat of neglect, or of the market’s inability to account for the social value of meaningful sites’ and structures’ existence, or of public prioritization of other objectives over that of heritage

conservation (highway system expansion, urban renewal, civic works)126. The demolition of the

original Penn Station in New York in the 1960s127 and the revitalization of the Vieux Carre in New

Orleans in the 1930s128 are cited as defining moments in the early history of modern preservation

in the United States129, motivated by fear of further loss. That first local ordinance in Charleston

was developed and adopted in direct response to an early pattern of demolition and loss of historic integrity in its downtown, which non-profit groups had been fighting with variable success since the beginning of the twentieth century130. Preservation has, importantly, proven to be

adaptable to respond to different threats131.

Prior to the adoption of the local ordinance and designation of Charleston’s first historic district, preservation of downtown Charleston’s historic gems was the private pursuit of non-profits132. With

123 National Trust for Historic Preservation.

124 Code of Ordinances, City of Pensacola FL § 12-2-10 125 Ames, 6.

126 Ames, 6.

127 National Park Service. “Laying the Preservation Framework: 1960-1980,” July 26, 2017.

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/culturallandscapes/cltimeline4.htm.

128 Fricker, Jonathan. 2012. “Vieux Carre Revival Style Architecture Rescued the French Quarter.”

Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans. December 3, 2012. https://prcno.org/vieux-carre-revival-style-architecture-rescued-french-quarter/.

129 New York Preservation Archive Project. “The Old and Historic Charleston District,” n.d.

http://www.nypap.org/preservation-history/the-old-and-historic-charleston-district/.

130 Weyeneth.

131 Verrey, Robert, and Laura Henley. “Creation Myths and Zoning Boards: Local Uses of Historic

Preservation.” In The Politics of Culture, edited by Brett Williams, 75–107. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991.

the precedent of those key figures, like Susan Pringle Frost in the 1920s133, preservation

continues to depend on private property owners to steward and rehabilitate historic properties. The 1966 National Act describes this dependency on private investment and management explicitly134.

Private property owners might buy a designated building, promote its designation, or invest in its rehabilitation, in part benevolently; those interviewed as part of this research described their choice to live in a historic district as motivated by an admiration for the district’s aesthetic, and a belief in the importance of keeping the district’s aesthetic intact135, with one interviewee making

explicit their self-identification as an “afficionado” who had only lived in historic buildings136. But

the private steward also may accrue a suite of private benefits by owning and stewarding a designated property, some through public sector incentives. These are intended to balance both the private cost of stewardship and the imposed limitations on or surrender of property rights137 --

the concern around which slowed early preservation efforts a century ago138 and resonates in the

case of Palm View.

One such public sector incentive is the federal Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit program,

through which $6B is leveraged each year to encourage private investment in the rehabilitation of roughly 1,200 historic properties139. Importantly, owner-occupied buildings are not eligible for the

federal tax credit. But states and counties often have their own additional credits or exemptions for improvements made to designated buildings, owner-occupied or not, such as Miami-Dade’s full exemption of property taxes on all added value after rehabilitation140. Recognizing the specific

burden borne by owner-occupants of single-family homes -- different from that borne by owners of income-producing properties -- the City of Miami Beach created various additional incentives to encourage designation of single family homes, such as zoning incentives and an ad valorem tax exemption on improvements to designated homes141. Other municipal perks for owners of historic

properties may include a waiving of fees (building, permitting) incurred in relation to a preserved property142. Another commonly cited incentive, for any historic property, is a promise of increased

133 Weyeneth.

134 National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (16USC470). Accessed April 14, 2020.

https://www.nps.gov/history/local-law/nhpa1966.htm.

135 Interview 6, 7. 136 Interview 7. 137 Conde, 2. 138 Weyeneth.

139 National Park Service. “Tax Incentives.” Accessed July 20, 2020.

https://www.nps.gov/tps/tax-incentives.htm.

140 Ad valorem tax exemptions for historic properties, Florida Statutes § 14-196 (2019). 141 City of Miami Beach Code of Ordinances, § 118-600 (2004).

property values following designation143, though the effect is acknowledged to vary144.

A Brief, Relevant History of Miami Beach and Its Preservation

The early history of urban south Florida, in brief, usually begins: When colonists arrived, south Florida’s conditions were initially deemed too harsh to support settlement, passed over by Europeans for more accommodating parts of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts for centuries145. The

entire peninsula has been described as the contiguous United States’ final frontier146, the

development of which “had many similarities with the westward expansion”147, first with the forced

removal of native populations, later with its inclusion in the Homestead Act148.

But the early Floridian homesteaders were few. It was not until men often described as northern entrepreneurs invested in transformative infrastructure and land reclamation projects in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that broader development ensued, with people like Standard Oil’s Henry Flagler kick-starting a transformation of the region “from a virtually uninhabited wasteland to a densely populated Fantasyland”149, made possible as it was elsewhere and in the century to

come by the rhetorical use of terms like “wasteland” and the displacement of communities of color150.

143 Coulson, N. Edward, and Michael L. Lahr. “Gracing the Land of Elvis and Beale Street: Historic

Designation and Property Values in Memphis.” Real Estate Economics 33, no. 3 (2005): 487–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6229.2005.00127.x.

144 Lowenstein, Ronnie. “The Impact of Historic Districts on Residential Property Values.” New

York, NY: NYC Independent Budget Office, September 2003. 2.

145 Grunwald.

146 Klepser, Carolyn. Lost Miami Beach. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2014. 11 147 Weinstein-Berman, 16.

148 Porterfield, Jason. The Homestead Act of 1862: A Primary Source History of the Settlement of the American Heartland in the Late 19th Century. New York: Rosen Publishing Group, 2005. 149 Grunwald, 5.

Figures 1-3: Miami Beach Plats, 1912-1914.151152153

South Florida’s population would grow over the next seventy years in step with expansion of a complex system of water infrastructure, a collection of canals and dikes and pumps154. With each

hurricane from 1926 on, further diking and canal-building ensued. By mid-century, the Central and South Florida Flood Control project “drained the southern half of the State of Florida”155.

After an agricultural venture in what would become Miami Beach failed, there arose from three Realty Company landowners competing visions of a future island city, resulting in the

development of lavish hotels and tourist-oriented shopping districts in what would become South Beach and Collins Park and, in contrast, wide suburban plots and single-family homes to the north and west of the island156. The Miami Beach historic district that this thesis uses as a case,

Palm View, is a product of this period of development, its land filed to be subdivided by Father-of-Miami-Beach157 Carl Fisher’s158 development company in 1920.

But land sales ultimately lagged in the city until, in part spurred by construction of connections to

151 “Miami Beach Plat, 1912.” Miami Beach, FL: National Register of Historic Places Collection,

1979. Division of Archives, History and Records Management. Miami Beach Historic Preservation League. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/AssetDetail/9fb2391b-b6d6-46ff-b798-258081072818.

152 “Miami Beach Plat, 1913.” Miami Beach, FL: National Register of Historic Places Collection,

1979. Division of Archives, History and Records Management. Miami Beach Historic Preservation League. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/AssetDetail/9fb2391b-b6d6-46ff-b798-258081072818.

153 “Miami Beach Plat, 1914.” Miami Beach, FL: National Register of Historic Places Collection,

1979. Division of Archives, History and Records Management. Miami Beach Historic Preservation League. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/AssetDetail/9fb2391b-b6d6-46ff-b798-258081072818.

154 Bloetscher, et. al, 313 155 Bloetscher, et. al, 312. 156 Weinstein-Berman, 27.

157 City of Miami Beach Planning Department, “Palm View Historic District”, 5. 158 Klepser, 20.

the mainland, hotel development ramped up in the early 1920s159, particularly after the Hurricane

of 1926. Weinstein-Berman writes of Miami Beach’s enduring boom-and-bust mentality: In spite of its heritage of planning traditions, Miami Beach’s urban development was spontaneous, generally left to the imaginative forces of speculative developers. Processes of building and rebuilding, which coincided with boom and bust periods of growth, still remain in the architectural ethos of many who reside and govern Miami Beach today.160

The years between the World Wars brought rapid growth in capacity for both full-time residents and visitors: The number of hotels in Miami Beach increased by 262% in the 1930s alone, while the number of houses increased by 190%, and apartments by 282%161 in that same period. Amidst

the Great Depression and simultaneous innovations in materials science, this period’s developers embraced in Miami Beach an architecture that was both economical and entirely new to the area162. Tourism-oriented development continued for decades, as Miami Beach was made

accessible to a new clientele with the advent of the national highway system163.

The next chapter in the history of Miami Beach typically details a period of economic decline, the end of which is in part attributed to164, or at least punctuated by, the addition of South Beach’s Art

Deco District to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. It was one of the first twentieth-century districts added to the Register anywhere in the country165, cited by some as the beginning

of a nationwide re-interpretation of the twentieth-century vernacular as something to behold166. A

more recent history of development in Miami Beach is one marked by significant expansion of the luxury housing stock and international investment167.

159 Patricios, Nicholas N. Building Marvelous Miami. University Press of Florida, 1994. 33. 160 Weinstein-Berman, 47.

161 Root, Keith. Miami Beach Art Deco Guide. Miami Beach, FL: Miami Design Preservation League,

1987. 9.

162 Weinstein-Berman, 40.

163 Stofik, M. Barron. Saving South Beach. Gainesville, FL: Univeristy of Florida Press, 2006. 16. 164 Weinstein-Berman.

165 Patricios, 33.

166 Weinstein-Berman, 54.

167 Viglucci, Andres. “The 100-Year Story of Miami Beach.” Miami Herald. March 21, 2015.

https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/miami-beach/article15798998.html.

Figure 4: Postmodernism in Miami Beach. Photo by author.

Figure 5: Art Deco in Miami Beach. Photo by Carol Highsmith, Library of Congress.

The success of having that first district nationally recognized –and the failure to save another National Register site, the New Yorker Hotel, from demolition in 1981 -- ushered in a wave of local preservation activism in Miami Beach168. By 1981, a countywide preservation ordinance was in

place169, declaring “as a matter of public policy that the protection, enhancement and

perpetuation of properties of historical, cultural, archeological, paleontological, aesthetic and architectural merit are in the interests of the health, prosperity and welfare of the people of Miami-Dade County.”170 Following precedent of preservation ordinances elsewhere, the county was now

168 Weinstein-Berman, 82. 169 Weinstein-Berman, 83.

170 Metropolitan Miami-Dade County Historic Preservation Ordinance, Ord. No. 81-13, § 2 (1981);

empowered to adopt rules of procedure, designate sites and districts, and regulate changes to those designated sites and districts171.

The ordinance provided that municipalities could either draw up their own preservation ordinances within a year, or be subject to regulation by the county board, though any local ordinances were to uphold minimum standards of preservation set forth by the county -- meaning, municipal ordinances could only serve to empower preservation boards further, not less. Miami Beach delegated preservation power locally with the passage of their own ordinance in 1982, setting forth mechanisms by which preservation of Miami Beach properties would be regulated and incentivized. Since passage of the local ordinance, over 2,000 buildings have been either individually designated or included in a historic district172.

Updates to the Miami Beach ordinance since its adoption have included clarifications of board power and community involvement. One preservation professional suggested that the ordinance had been formally strengthened half a dozen times173 since its adoption, while another described

the powers and procedures of the Miami Beach historic preservation board as “a work in

progress”, changes to which involve “usually tightening, finding holes or workarounds that people have found and then closing those”174. This could follow what has been suggested to be a

national trend of strengthening local preservation power175, though instances elsewhere of

loosening can also be found; examples include the repeal of ordinances, the shrinking of boundaries, or the adoption of informal norms of owner consent176.

Procedures for involving residents in board decisions have also changed since the original ordinance was adopted. Included in the original municipal ordinance was a provision for owner consent whereby owners of every single property included in a district proposal would need to provide consent to move the proposal forward177. The county found this provision to not meet the

minimum standards set by their own ordinance: Because the county ordinance included no owner consent provision178, the 100-percent owner consent provision in Miami Beach was interpreted as

a limitation on local preservation power179. While Miami Beach tried to change the provision to

only require 51-percent of owner consent, it ultimately had to concede to the county’s minimum standards and scrap the idea altogether180. A chance to reinstate the owner consent stipulation

came with an added provision to the county ordinance in 1986, which said that any municipality

171 Metropolitan Miami-Dade County Historic Preservation Ordinance, Ord. No. 81-13, § 9 (1981). 172 Miami Design Preservation League. “Miami Beach Historic Districts: Historic Architecture

Database.” Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.ruskinarc.com/mdpl/mb.

173 Interview 14. 174 Interview 11. 175 Frey.

176 Conde, 11.

177 Wilhelm, “A Brief History of MDPL”, accessed May 7, 2020.

178 Metropolitan Miami-Dade County Historic Preservation Ordinance, Ord. No. 81-13, § 9 (1981). 179 Interview 14.

that secured Certified Local Government (CLG)181 status could disregard certain minimum

standards set by the county ordinance. But while Miami Beach successfully applied for CLG status in 1987182, the provision for owner consent was never reinstated183.

Miami Beach’s ordinance was described in an interview as “one of the strongest in the country”, with the preservation board wielding “ultimate power”184. But, certainly, preservation board powers

in Miami Beach are not all absolute, and are mediated through compliance with public safety standards185, or by the interests of the Planning Board and City Commission186.

A Brief History of Palm View and Its Preservation

Palm View Historic District was designated in 1999, with a recommendation of designation brought forward by the Preservation Board and approved by the City Commission187. Its history

features many of the same prominent threads and players as the broader history of Miami Beach188.

With some orientation around a house once belonging to artist Henry Salem Hubbell -- to whom more than three pages of the designation report (developed by the Preservation Board and Planning Department) are dedicated -- the proposed Palm View district was, per its designation proposal report, largely designated because of its unique concentration of single family housing as well as the diversity of architectural styles represented within its few blocks189. The report

described Palm View as simultaneously “[representing] the whole span of Miami Beach history” as well as, with an unparalleled concentration, representing “low scale residential architecture” otherwise underrepresented in its corner of the city or the districts that preceded it190. While it

was not the first local historic district in Miami Beach, the Preservation Board at the time claimed that “[it] would be difficult to find a neighborhood more worthy of historic designation”191. In the

decades to follow, more and more of the single-family housing stock would become historically designated, with a 500% increase in locally-designated single-family housing occurring between 2005 and 2015192.

181 Division of Historical Resources, “Certified Local Governments”, accessed April 22, 2020. 182 Metropolitan Miami-Dade County Historic Preservation Ordinance, Ord. No. 03-38, § 3 (2003). 183 City of Miami Beach Code of Ordinances, § 118-503 (2004).

184 Interview 14.

185 City of Miami Beach Code of Ordinances, § 118-503 (2004). 186 Palm View Designation Report.

187 Palm View Designation Report. 188 Palm View Designation Report. 189 Palm View Designation Report, 21. 190 Palm View Designation Report, 21. 191 Palm View Designation Report, 21.