HAL Id: hal-02299667

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02299667

Submitted on 27 Sep 2019HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0

Co-ordinated studies in view of the future round of

multilateral trade negotiations in the agriculture and

food sector. Final consolidated report

Chantal Le Mouël

To cite this version:

Chantal Le Mouël. Co-ordinated studies in view of the future round of multilateral trade negotiations in the agriculture and food sector. Final consolidated report. [University works] Inconnu. 2001, 548 p. �hal-02299667�

FAIRs-CT97.348I

f'Co-ordinated

Studiesin View

of theFuture Round

ofMultitateral

Trade

Negotiationsin

theAgriculture

andFood Sectoril

INRA

.

EcoNoMIE

BIBLIOTHEQUE

Rue Adolphe

Bobierre

cs

6110335011 RENNES CEDEX Tét. 02.23.48.54.08

F'INAL CONSOLIDATED REPORT

Chantal

LE MOUEL

(co-ordinator)

INRA-Economie

et SociologieRurales,

RennesSeptember 2001

participants:

INSTrrur

NATIONAL DELA

RECHERCHEAcRoNoMIeuE

(France), ESR, RennesINSTITUT NATIONAL DE

LA

RECHERCHEAGRoNoMIeuE

(France), ESR, Grignon UNTVERSITY oF BONN (Germany), Institute for Agricultural policy(IAp)

UNTVERSITY OF READING (United Kingdom), Centre for Food Economics Research (CeFER)

V/AGENINGEN AGRICULTURAL UNTVERSITy (The Netherlands)

UNIVERSITY OF ROME "La Sapienza" (Italy), Dipartimento di Economia pubblica

INSTITUT NATIONAL DE

LA

RECHERCHEAcRoNoMIeuE

(France), ESR, ToulouseDOCUlllEliTATIOlll ECOI'IOl|il|E RUMLE REt'|t'lE$

FAIR5.CT97.348I

rf

Co-ordinated

Studies

in View

of theFuture Round

ofMultilateral

Trade

Negotiationsin

theAgriculture

and tr'ood SectorrtF'INAL CONSOLIDATED REPORT

Chantal

LE MOUEL

(co-ordinator)

INRA-Economie

et SociologieRurales,

RennesSeptember 2001

participants:

INSTITUT NATIONAL DE LA RECHERCHE AGRONOMIQUE (France), ESR, Rennes

INSTITUT NATIONAL DE LA RECHERCHE AGRONOMIQUE (France), ESR, Grignon

UNTVERSIIY OF BONN (Germany), Institute for Agricultural Policy (IAP)

UNryERSITY OF READING (United Kingdom), Centre for Food Economics Research (CeFER)

WAGENINGEN AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY (The Netherlands)

UNTVERSITY oF ROME "La sapienzÀ" (rtaly), Dipartimento di Economia Pubblica

Content

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION 1

1 - MATERIAL AND METHODS... 9

1.1. The database on tariffs, tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) and trade (chapter 2)...9

1.3. The decoupling issue (chapter 4)... t2

1.4. Assessing the world market environment: The

WATSM

model (chapter 5)... 131.5. MECOP:

A

modelof

the

EU's producing sectorof

cereals, oilseeds and protein crops (chapter 6)...1.6. A model of the EU's dairy and beef producing sector (chapter 7) L6

1.7. A spatial equilibrium model of the EU's dairy industry (chapter

8)...

... 181.8. A model of the EU's beef producing sector (chapter 9)... T9

1.9. A software for depicting the regional market of an Appellation of Origin (chapter 10)...20

1.10. Assessment of the impact of food quality and safety standards on EU-US trade in agricultural

and foodproducts (chapter 11) 22

1.11. Non-tariff barriers and market failures: Risk and informational aspects (chapter 12) ...25

2 - THE DATABASE ON TARIFFS, TARIFF-RATE QUOTAS (TRQs) AND TRADE 29

2.1.Inhoduction

2.2.The content of the database on tariffs and trade 30

2.3. Modalities adopted and sources used for constructing the database

3l

2.3.1. Modalities and conventions adopted

3l

2.3.2. Sources used... ..32

29

2.3.2.2. The United States ... 33

2.3.2.3. Canada and other countries.. 2.4.The dataset on tariff-rate quotas 33 2.5.

A

thorough assessmentof

the implementationof

market access disciplineof

the Uruguay 33 Round 3.3.2.1. Empirical implementation of the rates of change in the TRI... 3.3.2.2. Empirical implementation of the rates of change in the MTRI 2.5.1. Technical arrangements madeit

possible to minimise the constraints that resulted from UR market access commitments .... 342.5 .2. Implementation and management of TRQs ... 37

2.6. Conclusion: Lessons for the Millenium Round ...40

3 - MARKET ACCESS INDICATORS... 43

Assessment and comparison of tariff structures chosen by the European Union and the United States under the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture ... 43

3. 1. Inhoduction ... ...43

3.2. Available measures of trade restrictiveness: A review 44 3.2. 1. krcidence measures 44 3 .2.2. Outcome-based measures 46 3.2.2.1. Trade intensity measures ...46

3.2.2.2. Measures based on the equivalence among hade barriers... 47

3.2.3.The TRI and the MTRI... 49

3.2.3.1. The TRI. 3.2.3.2. The MTRI.... 52

3.2.3.3. Rates of change in the TRI and MTRI... 53

3.3. Empirical implementation of the TRI and the MTRI... 55

3.3.1. Empirical implementation of the MTRI in absolute terms... ....55

3.3.2. Empirical implementation of the rates of change in the TRI and the MTRI...57

49 ...57

3.3.3. Data and parameters 59

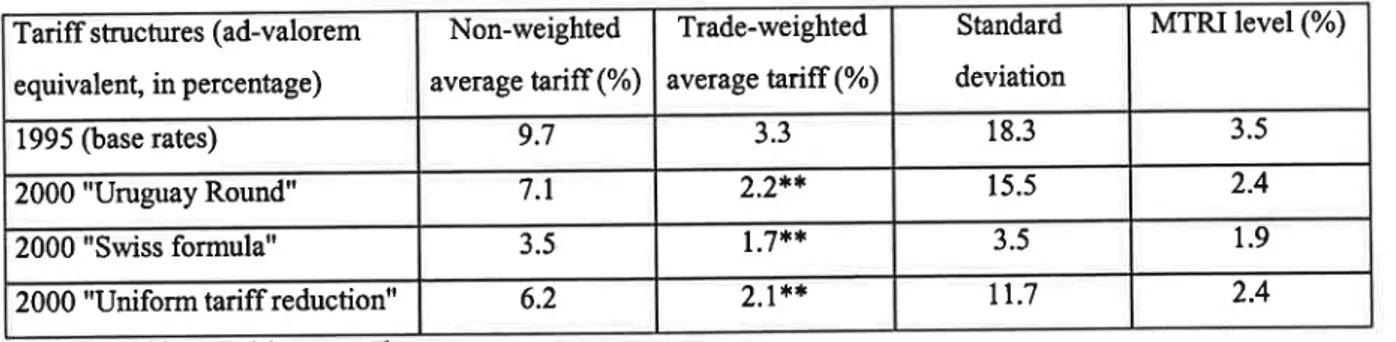

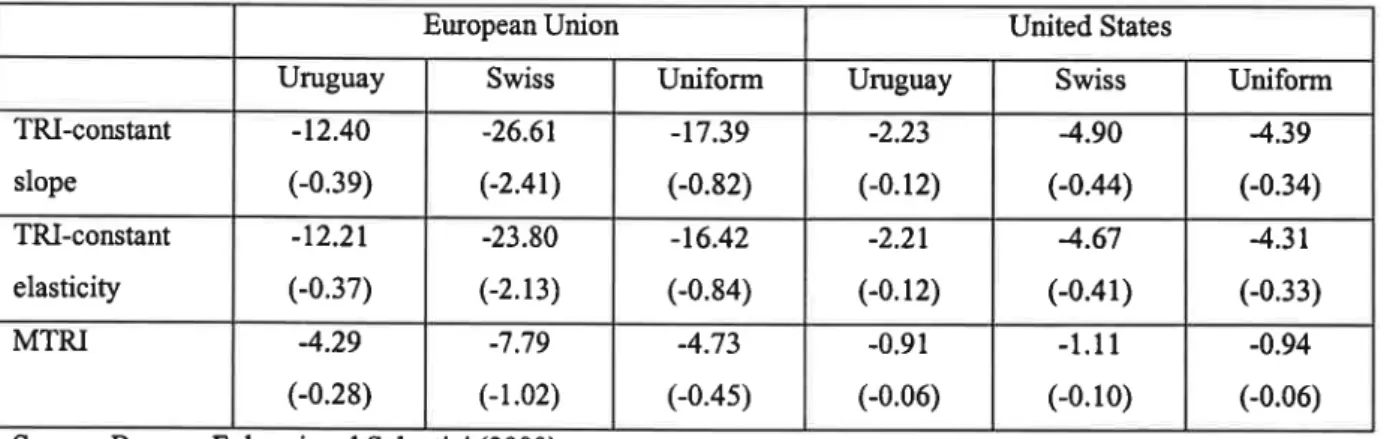

3.4. Empirical results for the EU and the US

6t

3.4. 1 . Three altemative tariff reduction schemes 61

3.4.2.lmpact of the Uruguay Round and counterfactual scenarios: Analysis

in

terms of TRI andMTRI rates of change... 62

3.4.3. Impact of the Uruguay Round and counterfactual scenarios: Analysis in terms of changes in MTRIlevels... 66

3.5. Conclusion: Discussion and policy recommendations 70 3.5.1. Howreliable are the a-theoretic indicators?. ..70

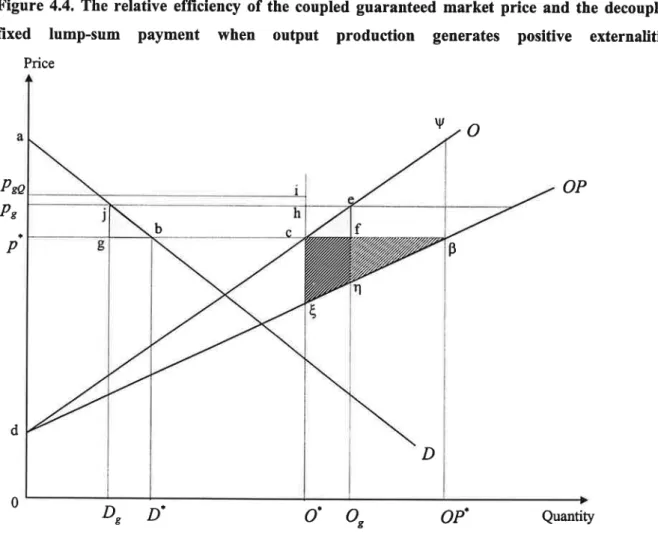

3.5.2. Policy implications,... APPENDD(. Sensivity analysis 73 77 4 - MEASURES OF INTERNAL SUPPORT 79 4.1. Introduction ...79

4.2. Decoupling agricultural income support: Economic

issues...

...824.2.L.

The

efficiency

argumentfor

decoupling agriculturalincome

support:A

graphical illustration 83 4.2.1.1. The guaranteed market price: Coupling and induced marketdistortions

...854.2.1.2. The production subsidy: Coupled to production only and less market distorting...85

4.2.1.3. The production quota-subsidy: A decoupled instrument? ... 87

4.2.1.4. The fixed lump-sum payment: effrcient and "decoupled"... 89

4.2.2.In practice, income support policy instruments are never fully decoupled...91

4.2.2.1. The fixed lump-sum payment and the individual decision to stop producing: The "cross-subsidisation" effect 91 4.2.2.2. The fixed lump-sum payment and labour decisions of agriculttral households ...93

4.2.2.3. The fixed lump-sum payment and investment

decisions...

...944.2.2.5. The question of the measurement of the degree of decoupling of income support policy

instruments 95

4.2.3.Decoupling income support policy instruments: The limits of the efficiency argument

in

asecond-best world... ... 96

4.2.3.I. The fixed lump-sum payment and the marginal cost of taxation 96

4.2.3 .2. The fi xed lump-sum payment and extemalities...'. 97

4.2.3.3. Decoupling agricultural income support instruments in a multi-output, multi-instrument

framework.. 99

4.3. Are the green box decoupling criteria for direct payments to producers well-designed: Taking into account adjustments on the land market and/or in the number of farmers... 102

4.3.1. The key role of factor mobility assumptions ... 103

4.3.3.1. The theoretical model 103

4.3.L2. Comparative static analysis ... 107

4.3.1.3.Factor

mobility and

the

greenbox

decouplingcriteria

for

direct

payments toproducers

4.3.2.T1rc key role of adjustments on the land market and in the number of farmers ... 111

4.3.2.1. The theoretical model ... 1 12

4.3.2.2.The impact of income support policy instruments on

trade...

... 1154.4. Promoting multifunctionality while minimising hade distortion effects: The relative merits

of

traditional policy instruments ... 120

4.4.1. Comparison

of

the

effectsof

alternative agricultural income support programsfor

aconstant budget cost/income support...

t22

4.4.2. Classification

of

the alternative income support programs accordingto

their ability toachieve the four policy objectives ,.,....'.,...,.,,.,., |26

4.5. Conclusion and policy recommendations ... r28

APPENDD( 1. Comparative statics of the model of paragraph 4.3.1

...

...'...'...132 APPENDD( 2. Comparative statics of the model of paragraph{.32 ...1335 - ASSESSING THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE WORLD MARKET ENVIRONMENT...137

Simulating the impact of further trade liberalisation on world agricultural markets using the ...I37 5. 1. Introduction ... 137

5.2. The WATSIM Modelling system: The WATSIM Data Base... ...138

5.2.1. The

WATSM

non-Spatial Data Base... 1395.2.1.1. Data sources ...139

5.2.I.2. Data processing...

t40

5.2.2.TheWATSM

Spatial Data Base ... 140140 5.2.2.2. Consistency adjustment ... ...r42 5.2.2.3 . Results of the consistency calculation ... ...t47 5.3. The

WATSM

modelling system: The simulation model 150 5.3. 1. Overall concept... ...1505.3.2. Representation of regional gross trade 153 5.3.2.I. Derivation of model equations ... 155

5.3.2.2. Derivation, estimation or "guestimation" of parameters?... 5.3.2.3. Regional exceptions.. 158 ...159

5.3.3. Representation of policy instruments 160 5.3.3.

l.

Market access .. ...1605.3.3.2. Domestic support... 164

5.3.3.3. Export subsidies.... ...165

5.3.4. Technical realisation... ...165

5.4. Likely Medium-Term Developments on Agriculttnal World Markets: The

WATSM

Reference Run 5.4. 1. Basic assumptions ...t66 5.4.2. Likely developments on agricultural markets ... ...1675.4.2.1. Grains ... 167

5.4.2.3. Meat... 181

5.4.2.4.

Milk

and dairy... 1855.4.3. The WATSIM reference run under an alternative assumption on the degree of decoupling

of

area and headage payments in the 8U... 189

5.5. The impacts of furttrer liberalisation of agricultural markets... 193

5.5.

l.

The'WTO scenario 1935.5.2. Impacts of further liberalisation on agricultural markets ... 194 5.5.3. The

WTO

scenario underthe

assumptionof

partial de-couplingof

area and headagepayments in the EU 195

5.6. Conclusion and policy recommendations ...196

APPENDX

1. Sensivity analysis: Sensitivity of the model outcomes with respect to the valuesof

the elasticities of substitution and of

transformation...

...200APPENDX

2.

Aggregate results of the WATSIM reference run... 2036 - MECOP: A MODEL OF THE EU'S PRODUCING SECTOR OF CEREALS, OILSEEDS AND

PROTEIN CROPS... 214

6.1. Introduction

..2t4

6.2. Theoretical framework

6.2.1. Preliminaries: The duality theory under allocatable quasi-fixed factor 6.2.2.The theoretical structure of the MECOP model

6.2.2.1. The first stage ...

6.2.2.2. The second stage...

6.2.3. Miscellaneous by-products of the MECOP model...

6.3. Estimation framework: The Generalised Maximum Entropy

6.3.1. The Generalised Maximum Entropy approach....

6.3. I . 1. Principles of the Maximum Entropy...

6.3.1.2. The Generalised Maximum Entropy

...222

2t7

22r 221 225 227 229 ...227 228 6.3. 1.3. Discussion... 2316.3.2.Implementation of the Generalised Maximum Entropy for the MECOP model 233

6.3.2.1. The set of estimated equations.... ...233

6.3.2.2. The choice of support values for parameters and disturbances 234 6.4. Estimation results ... ...23s 6.4.1. Application to France ...236

6.5. Policy simulations: The Agenda 2000 CAP reform and

beyond

...2426.5.1. Background and motivation ...242

6.5.2. Definition of simulated

scenarios...

...2456.5.3. The likely impacts of the Agenda 2000 CAP reform: The central scenario...247

6.5.4. Sensivity analysis: The sensivity

of

the Agenda 2000 simulation resultsto

the assumed evolution of market prices and the set-aside rate ... ...2546.6. Conclusion and policy recommendations... 257

APPENDD(. Estimation results for the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Spain and Denmark....260

7 - A MODEL OF THE EU's DAIRY AND BEEF PRODUCING

SECTOR....

...2737.2. A tool for simulating dairy policy reform... 275

7.2.1. Philosophy of the model 275 7.2.2. Ovewiew of the model 276 7.2.3. Description of the behavioural

model

...2807.2.3.t. Variable inputs and outputs 280 7.2.3.2. Adjustment of quasi-fixed

factors

...28I

7.2.4.Policies that can be simulated with the model.. ...2817.3. Specification and estimation of the

mode1...

...2827.3.1. Parameterisation of the model... ...283

7.3.1.1.

hofit

function and netputequations....

...2837 .3.1.2.

Milk

supply response... 7 .3.1.3. Quasi-fixed factors ...2837.3.2.Estimation of the equation system by mixed estimation

7.3.3. Prior information

7.3.3.1. Beef supply

7.3.3.3. Rationale for the elasticity decomposition ...

7.3.3.4. Priors for other parameters 7 .3.4. Data: Definitions and sources

7.3.5. Estimation and results

7. 3.6. Specialist dairy farm submodel ...

7 .4.3.3. Simulation results: Agenda 2000... 7.4.4. Simulations: Agenda 2000 plus quota abolition

7.4.4.1. Background..

7 .4.4.2. Quota abolition scenarios

7 .4.4.3. Simulation results: quota abolition ...

7.4.5.lmpact of scenarios on specialist dairy farms... 7.5. Discussion and conclusions

7.5.1. Technical discussion of model simulations

...288 ...289 ...325 286 291 293 302 322 32s 330 .,,,.,,,,293 299 304 7 .4. Policy simulations .... 305 ...30s

7.4.2.Modelling direct

payments

...3077 .4.2.1. The policy issue... ...307

7 .4.2.2. Supply behaviour.. 308

7 .4.2.3 . Policy changes regarding dairy... 310

7.4.2.4. Policy changes regarding beef and

vea1...

...3127.4.3. Simulations: Agenda 2000 ... 319 7.4.3.1. Background 319 7 .4.3 .2. Agenda 2000 scenarios... 321 ...329 ...334 ...33s ...33s

7.5.2.1. Decoupling 336

7.5.2.2. Yield growth 337

7.5.2.3. Quota rents 338

7.5.3. Policy conclusions 338

APPENDD( 1. Background

tables...

...340APPENDD( 2. Simulation results: Agenda 2000... 344

APPENDX 3. Simulation results: Agenda 2000 plus quota abolition

3sl

8 -A

SPATIAL EQUILIBRIUM MODEL OF THE EU's DAIRYINDUSTRY

...3638. 1. Introduction ... ... 363

8.2. The spatial model of the EU dairy industry.. 364

8.3. Policy simulations 367 8.3. I . Definition of simulated scenarios... ...367

8.3. 1. 1. The reference scenario.... 8.3. 1.2. Policy reform scenarios .. 367 ... 368

8.3.2. Simulation

results

...3698.4. Conclusion and policy recommendations... APPENDD( 1. description of the Spatial Equilibrium model with Component A11ocation...379

APPENDD( 2. Assumptions on supply and demand elasticities and on initial quota rents ...382

9

-

ECONOMETRIC MODELS OF BEEF PRODUCING SECTORSIN MAIN

EU MEMBER STATES ... 3849.1. Introduction 384 9.2. National models of beef and veal sectors: Structure and main characteristics...385

9.2.1. Demographic structure: An

illustration...

...3869.2.2.lmpacts of economic and policy variables ... ... 386

9.3. Estimation results ... 389

9.3.1.1. Calf crop models .389

9.3.1.2. Models of female animals older than one yeat... ...390

9.3.1.3. Models of male animals older than one year... 391

9.3.2. Dynamic elasticities ... ... 393

9.3.2.L Elasticities to the number of male

premiums

...3949.3.2.2. Elasticities to the number of suckler cow

premiums...

...3969.3.2.3. Elasticities to the intervention price 397 9.4. Policy simulations 399 9.4.1. The baseline scenario: The impacts of the Agenda 2000 reform 399 9.4.2.The restrictive premium scheme scenario: The impacts of a -20o decrease in the number

of

premiums granted... 4009.5. Conclusion and policy recommendations 402 APPENDD( l.Structure of the national models 403 APPENDD( 2. List of the exogenous variables 405 APPENDD( 3. Estimation results... 406

10 .

A

SOFTWARE FOR DEPICTING THE REGIONAL MARKET OF AN APPELLATION OFORIGIN 422 422 424 425 426 427 428 430 43r

43t

432 10.1. Introduction10.2. Regulation and quality reserve...

10.3. A simulation model

1 0.3. 1 . The reference situation: Free marketing...

10.3.2. Regulation of supply....

10.3.3. The demand side...

10.3.4. Optimal decision on drawing...

10.3.5. The developed software....

10.3.5.1. The law of agronomic performances... 10.3.5.2. The law of grape quality

10.3.5.3. The transition matrix 433 10.3.5.4. The basic structure of the software

10.4. Simulation of a Northern

vineyard...

...43410.4.1. The reference situation ...434

10.4.2. The simulated scenarios 10.4.3. Simulation results.... 436

10.5. Conclusion: CMO-WTO compatibility.. ...437

11

.

ASSESSMENT OF THE IMPACT OF FOOD SAFETY ANDQUALITY

STANDARDS ON EU-US TRADE IN AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD PRODUCTS... 4391 1. 1. Introduction .... 439

I 1.2. Technical barriers to trade

llz.l.

Background 439 lL.2.2. Technical barriers to tade: Definition and classificaton... ..,.,...,,.441:439 11.2.3. Understanding the impact of technical measures on trade 11.2.4. Measuring the impact of technical measures on trade 443 450 II.2.4.1. Frequency/inventory-based

measures

...450I L .2.4.2. Price-comparison measures ... 451

I 1.2.4.3. Quantity-type measures ...4s2 11.2.4.4. Compliance cost-based

measure...

...45211.2.5. Legitimacy of non-tariff

measures...:...

...4541I.2.6. The impact of technical barriers to trade: Empirical evidence... 455

11.3. Frequency of US technical measures on agricultural and food

products

...45911.3.1. The inventory database: A comparison of EU and US regulatory profiles 460 11.3.2.

The

frequencyof

technical measuresby tariff

line

(HS-02)using

the

UNCTAD's Database ,..,...,,... 469I I .4. Estimation of tariff-rate equivalents ... ..474

11.5.1. Theoretical

basis...

...47811.5.4.4. Border

procedures.

...49911.5.2. Survey of EU agricultural and food

exporters....

...482| 1.5 .2.1 . Nature of respondents ... 482

I | .5 .2.2. Main characteristics of respondents ...483

I 1.5.3. Survey results: Problems exporting agricultural and food products to the US...487

1 I .5.3. I . The importance of technical requirements relative to other factors influencing exports to the US ...487

11.5.3.2.

The

importanceof

technical requirementsin

the

US

relative

to

other

export markets ...49r 11.5.3.3. The awareness of exporters about US technical requirements... 49311.5.4. Survey results: costs of compliance with US technical requirements...494

11.5.4.1. Prior approval of production facilities 494 11.5.4.2. Product reformulation and/or change in production, packaging and labelling...497

11.5.4.3. Impact on production costs... 498

11.6. Analysis of US detentions of agricultural and food exports from the EU...504

1 1.7. Conclusions and policy recommendations ...509

12 -THE ECONOMICS OF NON.TARIFF BARRIERS. ...512

12.1. Introduction 512 12.2. Trade liberalisation and market failures ... 12.2.1. Trade liberalisation and imperfect competition 12.2.2. Trade liberalisation and risk... ....515

515 517 12.2.3. The importance of informational aspects 518 12.2.4. An economic assessmenVdefinition of non-tariff barriers: The case of the EU-US hormone-treated beef dispute 520 12.2.5. An emphasis on welfare analysis ,,,...52|

12.3.1. Voluntary versus mandatory certifi cation s25

12.3.2.Is labeling a way to solve market inefficiencies resulting from trade liberalisation?..,...,..525

L2.4. An assessment of the US system of food safety regulation and the possible outcome of V/TO

disputes... 527

12.5. Conclusions and policy recommendations 529

12.5.1. New criteria for defining trade

barriers...

....529L2.5.2. Lessons for the WTO dispute settlement 530

PREFACE

The final consolidated report of the programme "co-ordinated studies in view of the future round

of

multilateral trade negotiations in the agriculture and food sector" is the last deliverable

of

a project which started in March 1998.At

that moment, the common view was that both the commitments agreed uponin

1994, within theUruguay Round Agreement

on

Agriculture(URAA),

andthe next

roundof

multilateral tadenegotiations, scheduled to start by the end of year 1999, would be likely to impose further constraints

on the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and require additional adjustments

in

Common Market Organisations (CMOs).This

is in

that context thatthis

programme startedwith

the aimof

co-ordinating a task force working on the preparationof

the coming roundof

multilateral negotiations under the auspices of the World Trade Organisation (WTO).The main purpose

of

the project was to provide a setof

studies,in

connection with policymakers,involving a comprehensive economic analysis

of

the main issuesof

the next roundof

multilateral negotiations, as well as their consequences for the future of the CAP, and quantitative assessmentsof

the likely effects of WTO proposals on the European Union (EU) agriculhre.Such a purpose gave the project a somewhat specific status. On the one hand,

it

was clear since thebeginning that the proposed analyses would be policy-oriented and that the task force involved would work closely with EU decision makers. To this regard, one very positive aspect of the project is that

it

has benefited, during

its

overall lifetime,of

the

sustainedfollowing

and supportfrom the

DG Agriculture. On the other hand, as a FAIR programme, the project should not be limited to market andpolicy expert evaluation but also include genuine research work.

It

was thereforefor all

partners achallenge to develop analyical tools, based on economic theory, which outcomes would be directly useful for EU trade negotiators and decision makers.

The financing by the European Commission has allowed us to design a set of tools and to carry out

work for

makingthem

relevantto

analysethe main

issuesof

multilateral negotiations, theirconsequences in terms

of

CAP reforms and the effects of various policy options for EU agriculture. Provided tools are different in nature. They include databases, synthetic indicators, theoretical models and applied simulation models. The financing by the European Commission also madeit

possible to co-ordinate our effortsin

using these toolsfor

providing policymakerswith

sound economic andpolicy-oriented analyses,

with

a viewto

support trade negotiations and assist planningin

the EU agricultural and food sector.This

consolidated report presents methodologies used, models developed and main findings perresearch task.

Finally, as co-ordinator of the project,

I

want to thank the European Commission for financing thisresearch.

I

hope that the outcome is meeting the expectations and that our results are useful for EUtrade negotiators and policymakers. I also want to express my gratitude to DG Agriculture for the help

and

supportwe

benefitedall

alongthe

project'slife.

I

am

particularly indebtedto

MarinaMastrostefano for her constant following. Her involvement and her active contribution to our meetings

as

well

asto

our work have constituted an invaluable supportfor

the co-ordinatorin

leading this project through to a successful conclusion. Moreover her kindness and her sustained encouragement were a great help for the co-ordinator in doubtful moments.Lastly,

I

would like to thank involved partners. The good finalisationof

this project relies on theirexcellent scientific contributions. I greatly thank all researchers and assistants that have participated to

INTRODUCTION

The background to the FAIRS-CT97-3481 programme

The FAIR5-CT97-3481programme started on the beginning

of

1998.At

that time, the consequences of the basic provisions of the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture(JRAA)

for the EuropeanUnion (tIE) and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) were well documented in the literature (e.g.,

Josling and Tangermann, L992; Guyomard and Mahé, 1993; Helmar et

al.,

1994; Guyomard et al.,1996; Swinbank, 1996; Tangermann,1996). And all existing studies agreed that the major consûaint the AAUR would impose on EU agriculture would lie in the export commitments. The commitments

to

reduce domestic supportwould

imposeno

adjustment needson the

CAP

becauseof

theaccommodating heatment

of AMS

(Aggregate Measureof

Support) reductions,in

particular theexclusion

of

1992 CAP reform compensatory payments from AMS computation. In the same way,tariffication

of

border measures and the new access provisionsin

the formof

current access andminimum access tariff quotas would marginally improve the price competitiveness of imports into the

EU over the six-year implementation period.

The common view however was that, although the immediate quantitative effects of the URAA on EU agriculture

would

likely

to

be

modest,its

significance shouldnot be

underestimated.In

fact, "recognisingthat the

long-term objectiveof

substantial progressive reductionsin

support andprotection resulting

in

fundamental reformis

an ongoing process",Article 20

of

the Agreement includes a commitment to engagein

a new round of multilateral agricultural negotiations before theend

of

1999. Thus, the placementof

agriculture on the agendaof

multilateral negotiations and thedefinition

of

a negotiation frameworkin

the formof

three main areas, i.e., internal support, marketaccess and export competition, are two features of major significance of the URAA (Vanzetti, L996\.

Then, at the beginning

of

1998,it

was expected that the next roundof

V/orld Trade Organisation(!VTO) talks (the so-called Millenium Round) would use again the negotiation framework

of

theUruguay Round and that the proponents

of

reform (particularly the United States and the Caimsgroup) would push

for

further commitmentsin

termsof

intemal support reduction, market accessimprovement and export subsidy cut.

In

addition,by

announcing thatall

the support provided tofarmers under the Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act

of

1996 would qualiff for theso-called "green" box, the United States (US) had indicated their willingness to challenge the exemption

of a large share of EU farm support from reduction commitment (the so-called "blue box" issue). On

the other hand, the mandate given

to

the US Trade Representativeby

the Agriculture and Food Consultative Committee suggested that EU intemal regulations relative to competition, norms, qualityFrom the EU perspective,

it

was expected that not only theURAA

commitments would probably require a significant adjustment ofEuropean agriculture around the year 2000, but the next roundof

WTO negotiations would belikely

to

impose further constraints on the CAP, and require larger changesin

Common Market Organisations (European Commission, 1997;FAPRI,

1998; USDA,1998; OECD,1999).

The objectives of the FAIRS-CT9 7-3 48 1 programme

In that context, the aim of the FAIR5-CT97-348I programme was to co-ordinate a task force working on the preparation

of

the Millenium Round. The purpose of the prograrnme was to provide a setof

studies, in connection with policymakers, involving:

- comprehensive economic analyses of the main issues of the next round of multilateral negotiations;

- databases and indicators on trade and tariffs for the EU as well as other major trading countries;

- assessments of the world market environment and prices as well as of the forecasted effects of WTO reform proposals;

-

quantitative assessments of the economic impactof

WTO proposals onEU

agriculture, including simulations on reformsof

Common Market Organisations (CMOs) which could be necessary to comply with these proposals;-

assessmentsof

the effectsof

proposed "regulatory reforms" on theEU

agro-food industry, withspecial attention paid to the trade effects of food standards and food labelling.

More specifically, the following operational objectives have been retained:

1. Assess the ctrrent intemational trade environment, which

will

form the basis of the next roundof

multilateral negotiations.

2. Develop effective measures of trade restrictions, encompassing domestic support as well as tariffs

and non-tariff measures such as food safety and quality standards, and develop effective measures

of

decoupled domestic support.

3. Evaluate the impact of hade reforms on world markets and, in turn, the implications for European

agriculture and the food processing industries.

4. Assess the degree to which food safety and quality standards act as impedance to hade and the

5. Define an appropriate classification

of

Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) which assesses the degree to which such measures impede trade and/or actually address market failures, which can be applied toassess the impact of regulatory reforms.

6. Overall, to provide a comprehensive analysis of policy reforms and trade

in

agriculture and foodproducts

within

the European Unionto

support future hade negotiations and aid planningin

theagricultural and food sectors.

Presentation of tasles and subtasks

In order to achieve the above-mentioned objectives, the research has been organised into three tasks,

further divided

into

subtasksto

facilitate effective management. For each taskor

subtask,a

co-ordinator has been appointed who was responsible

for

the methodology, co-ordination and finalanalysis (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Tasks, subtasks and co-ordinators

r

Taskl:

Analysis of the international trade environment for agricultural and food products - Subtask l. I : Development of a database on tade (co-ordinator: partner 2, INRA-ESR Grignon)-Subtaskl.2: Constructing indicators of hade restriction, measures of protection and support, and assessing the consequences of choosing a particular indicator (co-ordinator: Partner 1, INRA-ESR Rennes)

- Subtask 1.3: Assessing the development of the world market environment and world market prices using a revised and updated version of the TRADE model (co-ordinator: partner 3, University of Bonn)

o

Task 2: Quantitative assessments of the economic impact of policy reforms on agriculture and the food sector inthe European Union

- Subtask 2.1: Arable crops (co-ordinator: partner I,II\IRA-ESR Rennes) - Subtask 2.2: Dany (co-ordinator: partner 5, University of Wageningen)

- Subtask 2.3: Beef (co-ordinator: partner l,INRA-ESR Rennes) - Subtask 2.4: W ine (co-ordinator: partner2, INRA-ESR Grignon)

o

Task3:

Effectof

proposed agreementsin

the areaof

regulatory reform on theEU

agro-food industry(co-ordinator: partner 4, University of Reading)

- Stage

l:

Survey of regulatory requirements- Stage 2: Interviews - Stage 3: Postal survey

Additional hackground elements durtng the coarse of the FAIRS-CT97-3481 programme

Since the beginning

of

1998, two main features have marked the background to theFAIR5-CT97-3481 programme. First of all, in March 1999, the EU adopted a CAP reform package (Agenda 2000).

This reform basically extents

the

1992 reform and inhoduces more decouplingin

the systemof

compensatory payments

to

COP (cereals, oilseeds and protein crops) producers. The Agenda 2000reform was largely motivated by EU export commitments under the AAUR and the expectation that these commitments

would

be

strengthenedin

the Millenium

Round (Desquilbetet al.,

1999).However, smoothing the EU East enlargement process and easing CAP budget pressures were also

important concerns supporting the Agenda 2000 reform.

Secondly, in December 1999, the Seattle ministerial conference marked the opening of the Millenium

Round. The first phase

of

multilateral negotiations (which endedin

March 2001) has consistedof

countries submitting proposals containing their starting position for the negotiations. Hence, since the

early 2000, 125 WTO member govemments have submitted 45 proposals from which

it

is possible todeduce the issues that are likely to be the major focus of the second phase of negotiations.

The synthesis

of

the overall received proposals providedby

theWTO

Secretariat (W'TO, 2001)globally confirms the main issues that were expected at the beginning

of

the FAIR5-CT97'3481 programme. On the market access side, furthertariff

reductions should be negotiated, but how thereductions

will

be handledis still

undecided and appears as a major negotiating area.It

is

widelyrecognised that the Uruguay Round (UR) calculated equivalent tariffs were very often too high to allow real opportunity for imports. Hence, the discussion is likely to focus on various ways to define and apply reduction rates,

for

market protectionto

be effectively reduced.I

Regarding tariff-ratequotas (TRQO there are several proposals for either replacing them with low tariffs or increasing their

size, but at the moment the discussion almost turns on quota administration. Many countries advocate

for increased scrutiny of methods used for giving exporters access to quotas. They add that

it

should be clarified which methods are legal or illegal under WTO rules. On the export competition side, asexpected further reductions

in

export subsidies should be negotiated. Currently, some countries propose thetotal

eliminationof

export subsidieswhile

others are preparedto

negotiate further progressive reductions. Finally, on the domestic support side, the received proposals dealwith

the three "boxes". As expected further reduction of "amber box" measures should be negotiated. As in thecase

of

tariffs, how this

additional reductionwill

be

applied seemsto be a

major concern indiscussions. To this regard, some countries advocate that ceilings should be set for specific products rather than having overall aggregated ceilings. Proposals dealing

with

the "green box" areof

threet

Th. US for example proposes that the negotiations to reduce tariffs starts with applied tariffs insteadof

types. Unsurprisingly, some countries push

for

increased scrutinyof

measures currently included,arguing that some of them, in certain circumstances, could have an influence on production and prices.

Others think that the "green box" should not be changed because

it

is

already satisfactory. The lastones argue

for

a broadeningof

the "green box"to

cover additional typesof

measures. Finally, asexpected, some countries want the "blue box" to be scrapped because

it

involves payments that areonly

partly

decoupledfrom

production. Obviously, someother

countries oppose scrappingit

completely and maintain that

the

"bluebox"

is

an importanttool for

supporting and reforming agriculture, and for achieving certain "non-trade" objectives.The synthesis of proposals by the WTO Secretariat points out a certain number of other issues. These

were also expected issues at the beginning of the FAIR5-CT97-348I programme. However, we paid lower attention to them when developing this programme. This is the case of, mainly, the extension

of

the export subsidy discipline to all forms of subsidies (including the effect of state trading enterprises,food aid and export credits) as well as "non-trade" concerns and multifunctionality.

All

these additional background elements, which punctuated the programme's life, did not make us to depart from the original plan. However, they contributed, in the finalisation stage, to bend the work undertakenfor

integrating theminto

our

analyses. Thus, asfar

asthe

Agenda 2000 reform is concerned, we decided when defining the reference runsof

all

developed models, that they should include this CAP change.It

results that, within both subtask 1.3 and task 2, the analyses carried outwith, respectively, the world hade (the so-called WATSIM) model and the EU sectoral models for

arable crops, dairy and beef start

with

an examinationof

the impactsof

the Agenda 2000 reformpackage in each ofthese EU sectors.

Secondly, the proposals submitted by countries to the WTO oriented our work in mainly two areas. On the one hand, they helped us to speciff the policy scenarios to be simulated with the various models.

Hence,

within

subtask 1.3,we

retained, asa

stylised liberalisation scenario,a

policy

scenarioreplicating the main provisions of the URAA, which in view of the submitted proposals appears as a

possible outcome

of

the Millenium Round. Furthermore, as submitted proposals confirm that thedecoupling issue

will

be a major focus of the Millenium Round, this issue being of key importance forthe future of the CAP, we decided

to

integrate the decoupling dimensionin

mostof

our simulated scenarios. Therefore,still within

task

1.3,all

simulated scenariosthat

were originally designed assuming coupled CAP direct payments have been supplemented by alternative scenarios assuming agreater degree of decoupling of these payments. In the same vein, within task 2, some policy scenarios have been defined in order to shed some light on the degree of decoupling of the Agenda 2000 CAP direct payment systems. On the other hand, following the growing debate around multifunctionality in

'WTO submitted proposals, we oriented our last work undertaken on decoupling

within

subtask 1.2towards this issue.

Outline of the report

In chapter

l,

methodologies used for the different subtasks are described. Chapter 2 refers to subtaskl.l

and deals with the database on tariffs and frade. The modalities adopted to construct this databaseas well as its content are first described. Then, a thorough assessment

of

the implementation of theUruguay Round market access discipline is provided. Chapter 3 refers to subtask 1.2 and focuses on

market protection indicators. Using the Trade Restrictiveness Index (TRI) and the Mercantilist Trade

Restrictiveness Index

(MTRI), a

comparisonof

EU

and UStariff

structures before and after the URAA implementation is proposed. This allows to assess and compare the improvementin

market access that was permittedin

both countriesby

the Uruguay Round commitmentson

tariffs. In addition, the effects of the actual URAA commitments are compared to altemative schemes oftariff

reductions such as the "Swiss formula" and the uniformtariff

reduction. This makesit

possible toassess and compare the impact of the uneven allocation of tariff cuts across commodities implemented

by the EU and the US under the URAA. Chapter 4 also refers to subtask 1.2 and is concerned with the

decoupling issue. The first part of the analysis gives an overview of the main advantages and limits

of

decoupling. The second part deals with the "green box" decoupling criteria as defined in Annex 2

of

the URAA. Two theoretical models are developed

in

order to compare the degreeof

decouplingof

various internal income support instruments, and

in

so doing to examine whether the corresponding"green box" decoupling criteria are well-designed. Using an extended version

of

oneof

theabove-mentioned theoretical models, the last part of the analysis addresses the question of the relative merits

of naditional income support instruments as regards to the promotion of multifunctionality. Chapter 5

refers to subtask 1.3 and reports the analyses carried out with the

WATSM

(World Agricultural TradeSlMulation) model. Firstly, a detailed description of the model is provided. Secondly, the reference

run of the model is presented and analysed, emphasising the tikely developments of the world market

environment,

as the

backgroundto

the

Millenium

Round.Thirdly,

the

resultsof a

stylisedliberalisation scenario, as a fictitious outcome of the Millenium Round, are described and discussed.

Chapters

2

and 5 contribute to the first objectiveof

the programme (assess the current internationalhade environment which

will

form the basis of the next round of multilateral negotiations). Chapters 3and

4

are devotedto

the second objectiveof

the programme (develop effective indicatorsof

traderestrictions and develop effective measures of decoupled domestic support). The third objective of the

programme (evaluate

the

impactof

trade reformson world

markets andtheir

implications forEuropean agriculture and the food processing industries) is dealt with in the last part of chapter 5 and

Chapter 6 refers to subtask

2.I

and, reports the analysis carried outwith

the EU sectoral model forarable crops. Chapters 7 and 8 both refer to subtask 2.2. Chapter 7 is concerned with the model of the

EU's dairy and beef producing sector and related policy simulations. While chapter 8 concenfiates on

the model of the EU's milk processing sector and related performed simulations. Chapter 9 refers to

subtask

2.3

and focuses on the analysis carried outwith

theEU

sectoral modelfor

beef. Finally, chapter 10 refers to subtask 2.4 and addresses the question of the welfare effects of an Appellationof

Origin using a software depicting a regional market regulated through an Appellation of Origin. hr all these chapters, the model developed

is

presentedfirst.

Then, the referencerun

of

the model is described and the obtained results are discussed. Finally, alternative simulations performed with themodel are proposed and results are analysed. In chapters 6 to 9, altemative simulations corresponds to

policy

change scenarios, whilein

chapter 10 they involve changesin

some characteristicsof

theregional market considered.

Chapters

1l

and 12 both refer to task 3. The assessmentof

the impactof

technical measures (orstandards) on EU agricultural and food exports to the United-States is the subject of chapter 11. The chapter starts with an analysis and a review of literature centred on the definition and the classification of technical measures, the impact of such measures on hade, the available methods for quantifring this impact and the existing studies devoted to estimate this impact in the context of trade in agricultural

and food products. Then, the impact of US technical measures on EU agricultural and food exports to the US

is

assessed combining various methods. Chapter 12 focuses on the economics of non-tariffbarriers. It proposes several analytical frameworks allowing to analyse the welfare effects of domestic

food quality and safety regulations and to examine their ability to address market failures. A particular

attention is paid to market failures resulting from risk and imperfect information.

Chapter 11 contributes

to

the fourth objectiveof

the programme (assess the degree to which food safety and quality standards hinder trade, and the implications of regulatory reform on trade flows). Chapter 12 relates to the fifth objective of the programme (define an appropriate classification ofnon-tariff barriers that assesses the degree to which such measures impede trade and/or actually address

market failures).

The overall report contibute to the sixth objective

of

the programme (to provide a comprehensive analysis of domestic policies and hade reforms in agriculture and food products in the EU, with a view1 -

MATERIAL

A}ID METHODSAs indicated in the infroduction, the research was divided into three tasks, further divided into eleven subtasks (or stages, as far as task 3 is concerned). In this report, results ofthese eleven subtasks are

reported in chapters 2 to 12. However for purpose of rationalising the presentation, one chapter does

not necessarily correspond to one subtask, even if this is most often the case. In fact, when one subtask

conbibutes to several objectives or, at reverse, when several subtasks contribute to the same objective, results are presented according to the objectives rather than according to the subtask they refer to. As there is an obvious relationship between material and methods used and pursued objectives, applied

methodologies for this project are described following the framework of chapters 2 to 12.

It

is

important to emphasise thatin

next sections, material and methods used are described without going into too much details since further descriptions are provided in each of chapters2to

12.1.1. The database on tariffs,

tariff-rate

quotas (TRQs) and trade (chapter 2)Subtask 1.1 consists

in

the developmentof

a database on tariffs and trade. The database has beenconsfucted

with

the principleof

matchingall

the relevant informationto

each counûry's officialschedule on bound tariffs, as submitted under the URAA.

As a result, the developed database is organised on the basis of the 8-digit Harmonised System (HS) classification, for chapters 01, 02, 03 to 24 (that is, all food products with the exception

of

fisheriesproducts), and for selected items

of

chapters29,31,35,38,

40,41,50,51

and52 (that is, non-food agricultural products, such as skins for leather, etc). This introduced a lot of difficulty for gathering therelevant information, since the list of commodities include some 2800 items.

The database has been constructed for a set of countries, namely Australia, Brazil, Canada, the EU,

Japan, Korea, Norway and the US. Datasets have been ôompleted in a satisfactory way for Canada, the

EU

and

the

US.

For

other

countries, datasets remainedflawed

becauseof

problemsin

the correspondence between the various sourcesof

information.It

was decided then, togetherwith

theCommissionrs representatives,

to

focus on the Canada,the

EU

and the US, andto

provide lesssophisticated data for other counties.

Hence, for Canada, the EU and the US, the constructed datasets include, in addition to the schedules on base (1995) and bound

tariffs

(2000), import values, import quantities,unit

valuesof

imports (under and outof

the Most Favoured Nation status) and applied tariffs,for

each year since 1995.tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) are an important issue in the WTO negotiations, TRQ information have been added to countries' datasets.

For the EU, data sources are mainly COMEXT for import values and quantities, and both the TARIC

and the UNCTAD's TRAINS databases for applied tariffs. Furthermore, obtained applied tariffs were checked against the applied tariffs published in the Official Joumal of the European Communities. For the US, hade and

tariff

data come mainly from the USITC (US International Trade Commission)database, while for Canada most of the data are extracted from the Statistics Canada database. Finally, for all three countries, the main sources for information on TRQS are the

IIRAA

schedules as well asnotifications that were obtained from the WTO Secretariat.

1.2. Market access indicators (chapter 3)

The part of subtask 1.2 devoted to market access is aimed at constructing indicators of frade restriction

and, on the basis of these indicators, assessing and comparing the improvement in market access that

was permitted in the UE and other countries by the IJRAA.

This part

of

subtask 1.2 has been ca:ried out by first conducting a thorough reviewof

literature onavailable methods to measure market protection. Relying on this review, the approach proposed by

Anderson and Neary, which develops theoretically consistent measures in terms of a given criterion

of

equivalence among trade barriers, has been retained. More specifically,

two

indicators have beenretained : i) the TRI (Trade Restrictiveness Index), which corresponds to the uniform

tariff

equivalentin

termsof

welfare

(Andersonand Neary, 1994) and ii)

the MTRI

(Mercantilistic Trade Restrictiveness Index), representing the uniformtariff

equivalent in termsof

imports (Anderson andNeary, 1999), and which might be more relevant regarding trade negotiations.

The second step corresponds to the empirical implementation of the TRI and the

MTRI

in

order toassess and compare the change

in

market accessin

the EU and other countries dueto

the URAA.Because the empirical estimation of indicators such as the TRI and the MTRI is very demanding in

terms of data and parameter requirement, it was decided to focus on the EU and the US.

The analysis involves three stages. Firstly, the rates

of

changeof

theUE

and USTRI

and MTRIbetween 1995 and 2000 are computed using the base and bound tariffs of both countries as submitted

under the LTRAA.

This first

stage allowsto

assess andto

compare how much liberalisation wasachieved in both countries by the end of the implementation period of the URAA, compared to the initial situation. Secondly, the rates of change of the EU and US TRI and MTRI between 1995 and

2000 are computed using two other schemes of tariff reduction: the "Swiss formula" and the uniform

the impact of tariff reduction commitments that would have focused more on reducing tariff dispersion than the actual LIRAA tariff cuts. For the uniform tariff reduction, the resulting changes in the TRI and

MTRI measure the impact of tariff reduction commitments that would have focused more on reducing

tariff average than the actual URAA commitments. Hence, this second stage allows to assess and to

compare the impact of the uneven allocation of tariff cuts across commodities implemented by the EU

and the US under the URAA. Thirdly, the levels of the EU and US MTRI are computed for the years 1995 and 2000, using the same three schemes of tariff reduction than within the second stage. This third stage adds information on the EU and US tariff structures at the beginning and at the end of the

URAA implementation period.

Prices, base and bound tariffs and import quantities required for computing the EU and US TRI and

MTRI were extracted from the database on tariffs and trade developed within subtask 1.1. Regarding

tariffs,

for

some commodities the EU andUS

schedules include a combinationof

ad-valorem andspecific

tariffs,

with

sometimes thresholdson

oneor

bothtariff

components. Therefore, specificcomponents were converted into ad-valorem equivalents by using the average 1995-1998 unit value

of

imports (or exports when imports were not available, or a unit value of the most similar commodity as a proxy when there was no trade in any of the four years). When tariff lines mentioned a threshold, the highest possible tariffs were considered.

Data on

total

expenditures were taken from the GTAP (Global Trade Project Analysis) database(version

4,Mc

Dougall et al., 1998).EU and US import elasticities were estimated econometrically. The estimation

of

these parameters raises a lot of problems, so that simpliffing assumptions had to be adopted. First of all required datafor a sufficiently long period were available only at the level of the so-called SITC classification (from the OECD's

NEXT

database), whichis

more aggregated than the 8-digit HS level. Hence, import elasticities were estimated for the commodity aggregates of the SITC classification. Consequently the single elasticity estimate of each aggregate was atfibuted to all 8-digit level commodities composing the conesponding aggregate. Secondly, due to the very large number of considered commodities, thespecification

of

import demand functions aswell

as the estimation procedure had to be simplified. Thus, import demand functions were specified in double log form, with the domestic own price (unit value) of imports deflated by the domestic consumer price index and the domestic real income as theonly explanatory variables. In other words, cross price effects were not taken into account, which is

clearly a limitation

of

the study. Finally, import demand functions were estimated over the period1,973-1996 using the OLS method.

Due to these adopted simplifuing assumptions, the estimated elasticities for any particular commodity can obviously

only be

considered asvery

crude estimates. Hencea

sensivity analysis has beenconducted

in

order to check how responsive are the TRI andMTRI

estimates to the magnitudesof

import demand elasticities.

1.3. The decoupling issue (chapter 4)

The part

of

subtask 1.2 devotedto

intemal supportis

aimed at contributingto

the debate on thedecoupling of intemal support instruments and the related WTO "green box" definition.

The analysis starts with a thorough review of literature on decoupling. Based on the general theory

of

welfare economics, the theoretical foundations of the principle of decoupling are reviewed. Then, themain limits of this principle when applied to domestic agricultural sectors and policies are discussed.

These limits mainly relate to practical concems and efficiency concerns. On the practical side, the

different mechanisms through which internal support policy instruments affect production and trade

are reviewed. From the economic efficiency point of view, the question is raised of the efficiency

of

highly decoupled policy instruments when concerned domestic economies are far removed from thetheoretical first-best economies and when objectives assigned to agricultural policies are not confined

to

supporting agricultural incomes.This last point

directly refers

to

the

questionof

themultifunctionality of agriculture.

The second step of the analysis addresses the issue of the measurement of the degree of decoupling

of

internal support policy instruments andof

the consistency of the "green box" decoupling criteria asdefined in Annex 2 of the URAA. The analysis is focused on income support policy instruments and

on coffesponding "green box" decoupling criteria (i.e., point 6 of Annex 2). This part of the analysis is

carried out by developing two different theoretical frameworks allowing to determine the effects on

domestic production and trade of various income support policy instruments.

The first model is directed at emphasising the key role of production technologies and factor mobility

assumptions as regards

to

the effectson

domestic production (i.e., the degreeof

decoupling)of

alternative income supportpolicy

instuments. The proposed model, inspired from Hertel (1989), considers two mono-product agriculttnal sectors, each using an aggregate variable input whose price isexogenous, a specific factor and a factor whose price is endogenous. Both sectors are competing for

this last

factor

which

is

alternatively consideredas

homogeneousand

perfectlymobile

orheterogeneous and so imperfectly mobile between sectors. Comparative static results allow to show

how the effects of policy instruments on domestic production are sensitive to adopted assumptions on

production technologies and factor mobility. They are also used to check whether specific decoupling criteria of point 6 of Annex 2 of the

t

RAA are well-designed.The second model has as its aim to examine the effects of various income support policy instruments

on

domestic production and trade when both the nurnberof

farmers and the priceof

land areendogenous. The proposed model, inspired from both Hughes (1980) and Leathers (1992), considers

one mono-product agricultural sector and consists

in

three equilibrium equations: the equilibriumcondition

in

the output market, the equilibrium conditionin

the land market and the entry/exit condition. Comparative static results allow to compare the degree of decoupling of altemative policyinstruments.

Finally, the third step of the analysis extents the second step by taking into account the multifunctional dimension of agriculture. More specifically, the second model is extended for allowing to examine the

effects

of

income support policy instruments not only on domestic production and trade (i.e., their distortion effects) but also on indicators (such as farmers'profit,

the numberof

farmers or yields) relating to various objectives that may be assigned to agricultural policies. In that case, comparativestatic results are derived

on a

constant cosVsupport basis, which allowsit

to

classiff

instrumentsaccording to their relative

ability

to achieve each policy objective while minimising induced tradedistortion effects.

1.4. Assessing the

world

market environment: The\ilATSIM

model (chapter 5)Subtask 1.3 is aimed at assessing the international frade environment, which

will

form the basis of theMillenium Round, and the impacts of trade reforms on world agricultural markets and trade.

This subtask has been carried out using a revised version of the

WATSM

(World Agricultural TradeSlMulation) model. WATSIM is a partial equilibrium, multi-region and multi-commodity simulation model

of

theworld

agricultural markets and trade. The current version covers 10 countries andregional aggregates accounting for the whole world. For each region, 29 commodities are included,

covering 4 cereals, starchy products, sugar, pulses, 4 oilseeds, 4 vegetable oils,

4 oil

cakes, 4 meats,eggs, milk and 3 dairy products. The model is a comparative static framework. Starting from the 1997 base year situation, it is solved for a given set of target years, with no information given on the path

of

adjustment between base and target years. Most parameters used

to

describe supply and demandbehaviours are not estimated but borrowed from other models or literature.

All

parameters are subjectto careful calibration to meet microeconomic theory.

The initial version of the model has been revised with respect to two main areas. On the one hand its original net trade representation has been changed to now consider endogenously gross imports and

gross exports on a same market. On the other hand, and based on the gross hade approach, the model's representation of tariff barriers and export subsidies has been improved. In addition, tariff-rate quotas

The implementation of the gross trade approach within the WATSIM model has been conducted in

two stages. Firstly, the former

WATSM

database has been updated and adapted to the new gross tradestructure

of

the model. The new WATSIM database consists nowin

two subsets: the former non-spatial database and the spatial database. The non-spatial database brings together data from varioussources on production, demand, frade and prices

of

agricultural commodities, macroeconomic and sectoral data as well as policy data.It

includes long time series, covering the period 1961-1997 (withsome series extending up

to

1999), available at the single country levelfor

some 110 agricultural commodities. Programming routines have been developed, that allow to easily and quickly check for data consistency as well as aggregate data according to the model's regional and commodity structure.Available time series are extracted mainly from the FAOSTAT (FAO of the United Nations) and PSD

(Production, Supply and Distribution, USDA) databases, the World Development Indicators (World Bank's database), the World Population Prospects (United Nations) and the Producer and Consumer Support Estimates (OECD).

The spatial database has been developed

by

adding bilateral trade flows and prices between themodel's regions

to

the non-spatial database. The spatial database includes time series covering theperiod 1988-1997, available

at

the

model's regional and commodity aggregate levels. Required bilateral trade flows are extracted mainly from the COMTRADE database (United Nations StatisticsDivision).

A

major taskin

the construction of the spatial database was to ensure consistency within this database and comparedwith

the non-spatial database. The experience shows that the "double reporting" in bilateral trade flows statistics (i.e., importer quotation and exporter quotation) does notnecessarily yields

in

mutual confirmation.In

addition,in

our specific case, the added gross importsand exports data (issued from the COMTRADE database) did not necessarily match the resulting net trade data

of

the non-spatial database (issued from mainly the FAOSTAT and PSD databases).Therefore,

in

orderto

ensure data consistency, the V/ATSIM spatial database has been constructed using an entropy-based approach, namely the cross-entropy approach (Golan et al., 1996).The second stage consisted in the re-designing of the WATSIM model in order to incorporate gross trade representation. Based

on the

Armington assumption (Armington, 1969),import

demandfunctions and export supply functions have been specified

for

each geographical zone and each commodity.Such

functions

closely

rely on

elasticitiesof,

respectively,substitution

andhansformation.

Due

to

data restrictions and resources limitations, these parameters have been"guesstimated". So, sensivity analyses aimed at investigating the impact of the adopted levels of these elasticities on the model outcome were carried out.

Since the new version of the WATSIM model represents explicitly gross imports and gross exports,

it

became possible to improve the modelling of trade policy instruments such as importtariff

barriers,TRQs and export subsidies.

In

very

general terms,for

each country and commodity, domestic"incentive prices" and import prices are linked to the corresponding world price through linear price

transmission functions. Specific and ad-valorem tariffs are represented by simple linear elements in transmission functions from

world

to

domestic import prices. Flexible levies are also explicitly modelled. They lead to non-differentiable price transmission functions. Thus, the exact relationship issmoothly approximated in order to allow for solubility. Just like import tariffs, export subsidies are

specified as an element

of

price hansmission functionson the

export side. They can either berepresented by a linear element or reflect a minimum domestic export price. In this last case, flexible export subsidies are modelled in a way similar to flexible levies on the import side. In addition, limits on subsidised exports are explicitly taken into account. For that purpose, two endogenous adjustment

options are introduced in the model solution: in the case of a minimum export price, the model forces

administrated stock purchases to adjust for subsidised exports do not exceed the corresponding limit;

in

the caseof

a constant export subsidy, the model forces the per-unit export subsidy to adjust for subsidised exports meet the bound. Lastly, TRQs are represented through two-tieredtariff

lines:preferential tariffs for within quota imports and MFN (Most Favoured Nation) tariffs for over quota

imports.

The

effectivetariff

(i.e., real protection)is

then determined andogenously.It

is

at

thepreferential

tariff

level as long as the quotais

unfilled, at theMFN

tariff

level when over quotaimports occur and between both tariffs when the quota is just binding. This effective tariff function is

non-differentiable and is approximated through smooth sigmoid functions.

1.5.

MECOP:

A

modelof

the EU's

producing sectorof

cereals, oilseedsand protein

crops (chapter 6)The main objective of subtask 2.1 is to develop a sectoral model of arable crops for the EU in order to

provide quantitative assessments

of

the

impactsof

reform

proposalsof

the

Common Market Organisation (CMO) for arable crops.Subtask 2.1 has been carried out

by

developing a modelof

the EU's producing sectorof

cereals,oilseeds and protein crops (the so-called MECOP model) and then using this model

for

simulating alternative policy scenarios.The MECOP (Maximum Enhopy

for

Cereals, Oilseeds and Protein crops) modelis

cented on EU supply of cereals, oilseeds and protein crops (COP).A

special feature of the model is that it considersexplicitly the main policy instruments currently

in

forcein

theCMO

for

arable crops (i.e., pricesupport, area payment system, set-aside requirement).