Affordances of Cultural Interfaces

Reading Print and Digital Poetry in

Stephanie Strickland’s “V-Project”

Matti Kangaskoski

Résumé

Dans cet essai j’envisage les différences de lecture et d’interprétation entre l’imprimé et le numérique en poésie à travers la notion d’ « affordance » (à la fois « moyen » et « usage potentiel »). Je considère la lecture comme une action culturellement construite qui inclut le processus de la lecture dans ses rapports avec une interface donnée et comme un moyen de donner un sens et d’interpréter ce qui a été lu. Une œuvre poétique est normalement circonscrite par les pages de couverture d’un livre ou codex. Cette couverture définit une totalité à l’intérieur de laquelle se donnent à lire tous les éléments dont nous avons besoin pour lire et interpréter et en principe nous sommes sûrs d’avoir un accès intégral à cette totalité. De plus, le codex est immobile en ce sens que les marques d’encre sur le papier sont là aussi longtemps que nous le voulons et ne changent pas d’une lecture à l’autre. Ces marques peuvent être vues comme les « affordances », soit les usages potentiels dans un contexte donné, du livre comme interface. Ces usages tout à fait familiers se font remarquer avec plus d’intensité dès que nous passons à d’autres médias : une création poétique numérique n’a souvent pas de limites physiques, elle n’a ni première ni quatrième de couverture, elle n’est pas régie par un mode de lecture linéaire ou conventionnel, et il y a plusieurs manières d’ouvrir et de parcourir le texte, parfois sur un mode tout à fait parcellaire, lettre par lettre, mot par mot. Des fragments peuvent fonctionner comme des ensembles indépendants, sans rapport avec les autres parties d’un tout qui n’est jamais certain. De tels usages, qui sont fonction de l’interface numérique, induisent une autre manière de lire qui modifie aussi bien ce que nous pensons de la pensée mais aussi la manière dont nous le faisons. Toute lecture poétique suppose des usages matériels, pratiques, cognitifs culturellement déterminés qui implique certains moyens et pour tout dire une certaine logique de la lecture.

Abstract

In this essay, my aim is to articulate the differences in reading and interpretation of print and digital poetry through the concept of affordance. I consider reading as a culturally guided action that includes the process of reading through interaction with the interface as well as means of making sense of what has been read, i.e. interpretation. A typical work of poetry can be circumscribed by the covers of a codex. The covers delineate a whole, a totality, within which we find all the elements we need to consider in reading and interpretation, and usually we can access the whole text without restrictions. Moreover, the codex is static in the sense that the ink marks on paper stay on the page for as long as we wish and from one reading to the next. These can be seen as affordances – potential uses, enabled actions in a certain environment – of the

codex interface. The familiar affordances become more pronounced in contrast with other media: a digital poetry application often has no clear textual boundaries, no front and back cover, no linear or conventionalized direction of reading, and the text can be accessed in many ways, sometimes in pieces as small as one word or one letter at a time. Pieces of the work can be encountered singularly, detached from the other elements of the (often assumed) whole. These features, afforded by the digital interface, suggest a different logic of reading that changes not only what we think about the poetry in question but also how we think about it. Reading poetry entails material, processual, cognitive, and culturally defined affordances that suggest certain means, a certain logic of reading.

Keywords

affordance; codex; cultural interface; digital poetry; Stephanie Strickland; reading

A typical work of contemporary published poetry can be circumscribed by the covers of a codex. The covers delineate a whole, a totality, within which we find all the elements we need to consider in reading and interpretation, and usually we can access the whole text without restrictions. Moreover, the codex is static in the sense that the ink marks on paper stay on the page for as long as we wish and from one reading to the next.

These can be seen as affordances – potential uses, enabled actions in a certain environment – of the codex interface. These familiar affordances become more pronounced in contrast with other media: digital poetry often has no clear textual boundaries, no front and back cover, no linear or conventionalized direction of reading, and the text can be accessed in many ways, sometimes in pieces as small as one word or one letter at a time. Pieces of the work can be encountered singularly, detached from the other elements of the (often assumed) whole. These features, afforded by the digital interface, suggest a different logic of reading that changes not only what we think about the poetry in question but also how we think about it.1 In this essay, my aim is to articulate the differences in reading and interpretation of print and digital poetry through the concept of affordance. I consider reading as a culturally guided action that includes the process of reading through interaction with the interface as well as means of making sense of what has been read, i.e. interpretation. Reading poetry, as I show below, entails material, processual, cognitive, and culturally defined affordances that suggest certain means, a certain logic of reading.

The codex, the printed and bound book, has for long been treated as the norm for delivering a work of poetry, to the point that at specific junctures in literary history it has been possible to dismiss its materiality

1 Spoken or performed, oral poetry that is never inscribed on any written form would present another interesting comparison with its specific affordances and cultural situation of listening/experiencing/interacting. Here I limit the investigation to concern print and digital media.

altogether.2 However, the very idea of close reading is founded upon the latent assumptions of the affordances of the codex. Of course, the codex itself offers multiple ways of exploring its own affordances, and literary history is full of experiments in size, material, typography, intermedia, alternative reading paths, different kinds of page bindings, and even book sculpture. Hence it comes as no surprise that the codex as a form has recently attracted increasing attention: the digital platform with its new affordances reminds us of the codex’s materiality and possibilities – possibilities to which we are, or were, perhaps, already blind.3 Indeed, as new modes, habits, and strategies of reading emerge due to new formal affordances, the affordances of the codex can be drawn out more clearly. Affordance implies a relation: an interface affords something to someone. This makes it a specifically useful concept for the analysis of reading: it is situated between the interface and the reader therefore enabling the investigation of the encounter that reading is. Furthermore, it enables an analysis that acknowledges the necessary interdependence of the various elements involved in this encounter.

I examine the affordances of print and digital interfaces and the kinds of reading they produce with the help of a case study: Stephanie Strickland’s poetry book V:WaveSon.nets/Losing L’Una (2002) and her iPad poetry application Vniverse (2014; in collaboration with Ian Hatcher). V:WaveSon.nets/Losing L’Una is an

invertible book: WaveSon.nets begins from one cover, Losing L’Una from the other, and they meet in the

middle. I focus my analysis on WaveSon.nets, which shares its textual data with the digital application; they contain the same raw material of words, structured and accessed in differing ways. This unique feature – same textual data, different interfaces – provides exceptionally good grounds for investigating how reading poetry is influenced by the affordances of the interface. WaveSon.nets organizes its text into 47 sonnets, one per page, whereas in the iPad application Vniverse the reader can access the poem through four different – what I call – reading modes. In each reading mode the poem is encountered and actively constructed anew. The two works are part of Strickland’s “V-project”, by now a family of five poetic works.4

The main goal of the essay is to articulate and examine the affordances that are at play in reading poetry. Doing so enables an analysis of how, on the one hand, cultural interfaces such as the codex and a digital poetry application afford and restrict means of attending to literary works and therefore encourage certain strategies over others, and how, on the other hand, reading habits and strategies adapt to ongoing medial change on a broader scale.

Affordances of Reading Poetry: Material, Processual, Cognitive, and Cultural

V: WaveSon.nets/Losing L’Una (2002) is a complex book of philosophical, political, and mythical content.

It has rhythmic and sonic beauty and a progression that can perhaps be best described with the metaphor of the wave. The sonnets, slightly reimagined from the traditional form to contain fifteen lines instead of fourteen, and without a clear rhyming structure – hence Son.nets – proceed in waves, enjambed over stanzas and often over Son.nets to connect them to each other. Thematically, one of the core issues of the poem is

2 See, for example, David Ciccoricco (2012) who argues that the New Critics treated text as independent of its material conditions. 3 See, for example, Kiene Brillenburg Wurth, Kári Driscoll, and Jessica Pressman’s Book Presence in a Digital Age (2018). 4 In addition to the mentioned two, the project includes another book and two web applications: V:WaveTercets/Losing L’Una (2014), Vniverse web application (2002), and Errand Upon Which We Came web application (2002). Within the project, V:WaveSon.nets/Losing L’Una and the Vniverse iPad application present the biggest formal contrast and are for this reason the most fruitful for the comparison at hand.

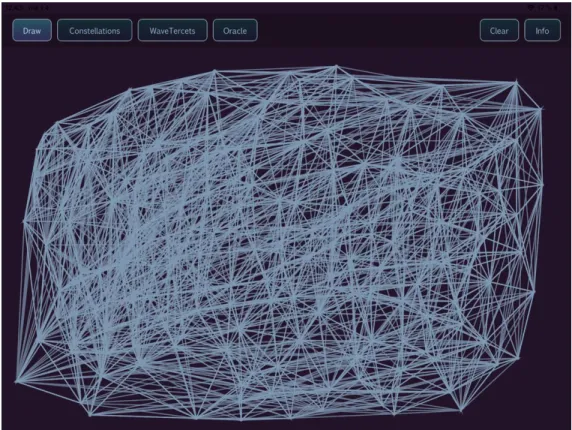

the question of mediation and understanding through mediation: how do we mediate the unorganized world into understandable forms? Similarly, the formal experimentation of the family of works asks: what happens to understanding when a poem is presented in the form of a sonnet, a tercet, or when the reader gets to organize the textual material according to her own whim?5 To this end, the textual data of the WaveSon.nets is found in the iPad application Vniverse, which offers the poem through a menu of options. The reader can choose between the above mentioned reading modes and encounter as well as actively participate in constructing the text through options found in these reading modes. Instead of 47 Son.nets, the poem is now encountered in varying forms from tercets to individual words and their combinations. The continuous wave of WaveSon.nets is broken into smaller bits and permutated around the visual image of the night sky presented at the interface (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Screen capture of Vniverse iPad application.

The starry night sky interface of the Vniverse app has “Draw”, “Constellations”, “WaveTercets”, and “Oracle” in round-edged boxes in the upper part of the screen, roughly where we are accustomed to find a menu bar. In the Draw mode readers can draw their own constellations with their fingers. Upon touching a star a corresponding keyword appears but the word starts to fade soon. One can then tap on stars randomly or glide fingers across the screen so that lines connect the stars. The words fade quickly but the connecting lines stay so that the stars and their corresponding words can be revisited without haste. In the Constellations mode the reader can explore pre-organized constellations one at a time. Each star in the constellation yields a tercet. Where to start and where to proceed is up to the reader. Each constellation, however, forms a preselected and stable set of tercets: for example, in the constellation “Swimmer” one finds tercets 1-15. The WaveTercets mode is time-based and plays the poem for the reader without her active participation. The tercets start from 1 and advance at a steady pace of approximately eight seconds per tercet all the way to 232. The pace affords reading the full tercets, but there is no extra time for understanding. Going back is difficult since one would have to keep track of the stars where the tercets appeared.

Finally, in the Oracle mode the reader can pose questions to the work that now functions as an oracle. The application gives personalized answers to the reader drawing from the textual data through various filters. A reader can ask the poem what she loves, for example, and the poem will answer. Asking questions from a textual, aleatory work can be seen as an allusion to divinatory works such as the Chinese I Ching or to refer to the Oracle of Delphi in Ancient Greece. On the basis of this preliminary description it is already clear that the application affords strategies of reading wholly different from the codex. Now that we have an initial understanding of the two interfaces, we are better positioned to look at their affordances as cultural interfaces.

Above I gave the definition of affordance as an action enabled in a certain environment. Caroline Levine (2015, 6) gives a useful further description:

Affordance is a term used to describe the potential uses or actions latent in materials and designs. Glass affords transparency and brittleness. Steel affords strength, smoothness, hardness, and durability. [...] Specific designs, which organize these materials, then lay claim to their own range of affordances. A fork affords stabbing and scooping. A doorknob affords not only hardness and durability, but also turning, pushing, and pulling.

Let us look at the example of the doorknob more closely. The doorknob’s material form facilitates its use. It is at a convenient height for hands and affords grasping and turning – but how do we know to turn it? The term affordance was originally introduced by James J. Gibson in ecological psychology as action possibilities offered by the environment to the animal (1979; see also Kaptelinin 2013). Affordances come to be in

mutuality between the animal and the environment (ibid.). This means that a given environment affords

different actions for a human and for a dog. A doorknob, for example, is easily turnable for me, but not for a dog. Different animals observe their environment according to their needs and capabilities. The mutuality aspect is essential because it shows how perceiving affordances is inextricably tied with the capacities of the creature in its environment. A dog can learn to open the door but it will not be easy for him.

In addition, the object can be used for different purposes, such as the doorknob for hanging clothes. This means that the design does not enforce its use, but affords it, and, in the case of successful design, as Norman (1988), who introduced the concept to design theory, argued, encourages it. Bucher and Helmond note that the “Gibsonian understanding locates affordances in the relation between a body and its environment, whereas the low-level conception of affordance takes after Norman by locating affordances in the technical features of the user interface” (2017, 204; see also Sun and Hart-Davidson 2014, 3536-7). I take both of the above conceptions into account in my conceptualization of the term in relation to reading: affordances as action possibilities are enabled by the technical characteristics of the interface but they only arise in interaction, in mutuality, with the reader.

Thus, starting from the simple example of the doorknob, there are i) material affordances that come with the physical size, shape, weight, feel, and look of the interface, and ii) processual affordances that come with the functionality of the interface. In terms of reading poetry we can think of the look, weight, and page-turnability of the codex. This means that we can access the whole text without restrictions and read in whatever pace and order we choose. The iPad, in contrast, has a different weight and look, and, as a digital interface, affords wholly different processes. In the Vniverse iPad application, for example, the processes of the WaveTercets mode restricts the reading time of one tercet into eight seconds.

Therefore, the material and processual affordances suggest different means of reading, which adds iii) a cognitive facet to affordances. As N. Katherine Hayles (2012) has suggested, the codex affords the cognitive mode of deep attention whereas the digital online interfaces afford the cognitive mode of hyper attention. Not surprisingly, the cognitive mode of deep attention is associated with close reading whereas hyper attention is associated with hyper reading, characterized by skimming, reading multiple information streams, switching between tasks rapidly, and a short attention span (ibid.). Moreover, textual form as such has a cognitive facet. To give a crude example, in today’s information overload society it becomes more and more clear which forms of language afford recognizability and easy access to readers pressed for time and with shortening attention spans. A story that centers around an individual’s experience, for instance, seems to be one of the textual forms that people want to read and engage with (see Salmon 2017). Hyper attentive reading habits online and increasingly also offline claim their own affordances of brevity and clarity to sustain the attention of readers. Any difficulties in reading, ranging from unfamiliar vocabulary to ambiguity, can hinder the reader due to longer reading times and more effort required for understanding.6

The cognitive facet is interlinked with iv) cultural-social affordances that arise from learned conventions of use of the interface. Learned cultural conventions include tacit knowledge about how the interface is used but also where and when it is typically used. How do I know, for example, that the round-edged boxes in the

Vniverse application are touchable? The knowledge and skill of using technology, including assumptions

about reading and writing on print and digital interfaces, has been theorized through the concept of technological frames (Orlikowski and Gash 1994; Taipale 2014). Analogously to cognitive frames, technological frames guide our knowledge of the usage of interfaces and derive from education, previous use, is learned in social groups and so on (ibid.). In other words, they are learned through culturally defined conventions in specific environments. That we know an interface button to be push-able, that some of us still read newspapers specifically in the morning, or that we pull out the smartphone while standing in traffic lights to check for messages – these are cultural conventions, formed in use and become habitual over time. Similar conventions and assumptions guide reading: for example when I sit down with a book of poetry, I make tacit assumptions of what kind of reading is to be expected and what kind of cultural value it might bestow on me. The tacit assumptions can vary greatly, but the codex as medium narrows them down: if I settle to read a book of poetry, the assumptions will mostly be about reading a book of poetry, ranging perhaps from reverence to indifference to aversion. If, in comparison, I sit down with the iPad, many other relationships and possibilities of use are tacitly present in the same medial object – email, news, social media, other books and literary applications, games, movies – and my relationship to them. To briefly evoke Louis Althusser’s term interpellation: the interface calls, or hails, me as reader into a cultural context with embedded conventions and beliefs.7

In sum, there are at least material, processual, cognitive, and cultural affordances that make the affordances of reading poetry. This reveals clearly that reading poetry is not an isolated practice that an individual does in an unaffected ideal vacuum. Instead, poetry is tied to a material medium with its texture and functionalities;

6 See e.g. the empirical study on ambiguity effects of rhyming and meter by Wallot and Menninghaus (2018). They note in addition that although ambiguity requires more effort and a longer reading time, it has also been shown to enhance aesthetic appreciation; what is considered a cognitive cost in everyday communication becomes a positive aspect in the realm of art. If, then, people are increasingly hyper-attentive and decreasingly deep-attentive, we could hypothesize that also poetic language is perceived as a cognitive cost rather than aesthetic delight.

7 For interpellation, see Althusser’ classic essay “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” (2004). For interpellation on digital interfaces, see Stanfill (2015).

it is related to the user’s cognitive affordances, and it is situated in cultural, shared conventions and practice. Moreover, all these parts are interlinked so that, for example, the user’s cognitive mode is influenced by the medium on which she reads which is, in turn, influenced by the conventionalized cultural practices associated with that medium.

Reading WaveSon.nets and the Vniverse iPad Application

Using the framework of affordances outlined above, I demonstrate that the two interfaces of WaveSon.nets and Vniverse iPad application afford and invite wholly different readings. The differences in the basic material affordances of shape and feel have already been discussed above, so here I would like to draw attention to how the codex and the poetic form of the WaveSon.nets afford time and organization of reading and what kind of interpretation is therefore enabled. Then I will compare it to the Vniverse iPad application, and to conclude, I will read them both as cultural interfaces.

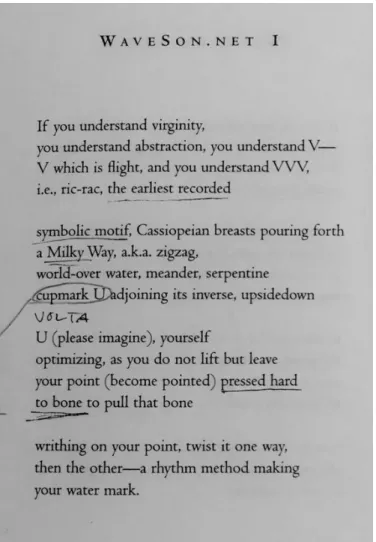

In WaveSon.nets we find one Son.net per page where each Son.net has four stanzas (see Figure 2). The poem uses enjambment not only between stanzas but also between Son.nets. Enjambment creates the metaphorical waves of thought, connecting Son.nets together. These metaphorical waves, however, are not factually continuous, but consist of discrete units: Son.nets, stanzas, lines, words, and, of course, individual letters.

A print poem can typographically afford rhythm and tempo by organizing its units in a specific way. In

WaveSon.nets we find poetically significant spaces between lines, between stanzas, and between pages. These

spaces create breaks in the flow of reading and a cognitive break for the reader to digest what is being read. The effectiveness of breaks between full Son.nets is further effectuated by the factual turning of a page or moving from one page to another within one spread. Breaks between waves of thought are indicated by a full stop in the end of the Son.net. Thus, the turning of pages and the typographical layout afford conventionalized breaks for the reader to pause. An actual reading of a poem rarely proceeds inexorably and even-paced from one word, line, stanza, and page to the next, but rather with a fluctuating pace with pauses, decelerations and accelerations, perhaps leaps and stagnations. Additionally, in print, the reader can jump back and forth, “double read” (Calinescu 1993), and of course, reread the text in its totality. Breaks, pauses, double reading, and rereading are indeed necessary because WaveSon.nets uses inventive imagery, makes broad associative leaps, alludes extensively to philosophy, science, myths, and literature, and generally creates a totality in which its parts are highly interconnected. The codex interface habitually affords this kind of reading, and as is visible in Figure 2, paper affords annotation, which is another material affordance that is of assistance in reading a complex work. Were the reader to engage in this kind of close reading, interpretive conclusions would involve the background assumptions of coherence within a totality – all parts relate to each other and are regarded as a whole. Furthermore, the poem is to be interpreted intersubjectively, proceeding from text to context, relating its parts to its whole, and the whole to a social, cultural, and literary context. The interpretation thus formed aims to be communicable and meaningful to other readers of the same poem. This might seem self-evident but is only so due to convention, and once we move away from the affordances of the codex, these assumptions have to be altered.

While the textual data remains the same in the Vniverse iPad application, many of the background assumptions of reading have to be revised. The words and literary forms found in the WaveSon.nets can here be seen as raw material, contained in the application’s database. The reader, then, draws from this database in various ways, instigating actions, making selections, and participating concretely in the creation of the poem at the interface.

Let us begin the comparison with the Draw mode. Upon touching, each of the 232 stars yields a word, and moving from one star to another, a connecting line appears. As the word “draw” suggests, the reader is encouraged to move her finger across the screen thereby connecting multiple stars with drawing movements.8 So I move my finger across a few stars, thus making a trajectory that moves through words and stars. This can be enjoyable for a while due to the ludic and tactile satisfaction of making these trajectories. The keywords, however, rarely make much sense together and even if they do, they lack intentionality since I am the one who, based on whim, decides which stars to connect. A more serious point can, however, be made: I wanted to try to connect as many stars as possible and this endeavor ended in practically coloring the screen full (see Figure 3). Doing so I soon realized that what is forming on the screen is a visualization of the interconnectedness of, on the one hand, the elements of the poem, and on the other, as a more general interpretation, of the interconnectedness of things in the world as such. The latter point is further supported by the poem. In WaveSon.net 44, the last two stanzas read:

8 Here a notable difference in writing about this kind of reading emerges: I have to move from the impersonal “the reader” to the first person singular, since the choices of the individual reader, in this case me, are significant in reading the application.

Begin with a closed interval, include ends, take out the middle: on the separated term, do

again, again… creating, or leaving, a structure more and more open, of sparkling points.

Indra’s Net? Cantor dust.

Do there exist beings where all take each other into account, in their very core?

Indra’s Net refers to Hindu and Buddhist mythologies where it symbolizes a web of interconnections, sometimes described as a net of jewels all reflecting each other. Cantor dust is a mathematical concept whose process is described in the first stanza above, starting from the line “Begin with a closed interval, include ends”. The poem interprets Cantor dust as a “more and more open” structure of “sparkling points”, which, connected with the reflecting jewels of Indra’s Net, unifies the two visions of interconnected but open structures. Transposing these visions onto the structure of the poem we have the mentioned interconnectedness but also openness: WaveSon.nets is, like Cantor dust, an open and elliptical, albeit poetic structure. In addition, in my personal reading I can report a haptic satisfaction and a beauty in simply making the connections with my finger and creating this image. A tactile satisfaction, turning of pages, moving fingers on the paper, is not entirely missing from reading the codex, but it is so habitual that it is easily dismissed.

Fig. 3. Screen capture of Vniverse iPad application.

Processually controlled time is a feature found throughout the application. In the Draw and Oracle modes, words and stanzas fade in about eight seconds whereas the WaveTercets mode plays the 232 tercets through one by one. There is no temporal pause between the tercets, instead they even overlap so that the next tercet

appears when the previous is still on screen, fading away. The progress of the tercets is not, however, inexorable: by tapping the star that corresponds to a given tercet one can reread it as many times as one wishes. Nevertheless, compared to the codex, paying attention to the poem is significantly more difficult. Due to the cognitive load of this open and associative poem, eight seconds per tercet is not enough to grasp what is said. However, as with the Draw mode, this temporal progression adds a unique feature that is linked to spatial formation and the steady ebb and flow of the poem. The reader can follow visually where each tercet appears and to what constellation it belongs. This produces a spatial image of the poem that is quite different from the sequential progression of turning pages. In addition, the eight-second intervals can be, at least in my reading, felt as pulses, or perhaps even waves, that come and go. The wave-effect is reinforced by fading the text of the tercet in and out. Again, in the iPad application there is less emphasis on the thematic comprehension of the text as a whole and more on the interaction between the processes of the poem and the reader’s engagement in the joint performance this interaction creates. To sum up the difference here: The printed poem affords spatial and cognitive pauses between stanzas and pages and enables the reader to control the time spent and the progression of reading. The temporal progress of the WaveTercets mode erases the pauses between stanzas (here tercets) and, if unobstructed, proceeds in pulses that afford less textual and thematic comprehension. Instead, it enables a spatial image of the poem and creates a pulsing effect, which can be felt in the body. Additionally, the WaveTercets reading mode complicates the binary between hyper and deep attention: on the one hand, it requires the patient and attentive following of one information stream – the ebb and flow of the tercets – but the pace is relatively fast for proper understanding and the reader is not in control of the progress of reading. However, we can imagine a reading in which one lets go of the requirement of understanding and is simply sampling some bits of text here and there, enjoying the poetic performance of appearing and disappearing tercets.

From the temporal point of view, the Oracle mode is similar to the Draw and WaveTercets mode. Once a question is asked, the reader gets an answer in the form of individual words or a tercet, or a combination of these. Both words and tercets, however, fade away, again, in about eight seconds. The momentariness of the answer is congruent with asking personal questions in the vein of I Ching and divination. The I Ching originally used yarrow stalks to form the hexagram based on which the divination was done. The idea, as explained by C. G. Jung (Wilhelm 1968), is that the energies at that particular moment affect the position of the stalks and therefore the divination is strictly based on that very moment and situation. The same can be thought of Vniverse’s computational divination. I can ask a question and an answer appears based on the aleatory processes of the poem in that moment. Here the questions are preset, however. The reader can pose questions such as “Whose body?”, “How to know?”, “Why Care?”, or “What do I love?”. From the point of view of personal engagement, the most evocative question is “What do I love?”, since the answer is very directly something to each reader personally. According to the poem, I love “lining / into a gray silent sea, / turquoise lining.” combined with the words “flowing”, “vestige”, and “Struggling”. These passing answers may be meaningful to the reader or they may not, depending on how seriously one takes the idea of divination. But again, there is a participatory element as the reader can choose the question to be asked, and there is a visual element as the answers appear here and there on the night sky. For the question “Why Care?” all other stars but a few fade away for a moment and then fade back in as a single word appears for an answer. By now the interfaces have been explored in sufficient detail to draw out more general consequences for the means of understanding of what is read and for what kind of interpretation is afforded. Whereas the codex is static and its text is organized into sonnets, in the iPad application we find various different ways of organizing and presenting the text to the reader. In all the reading modes except the sequentially set and temporally

controlled WaveTercets, the reader has a heightened exploratory role in uncovering the data through choices and tactile gestures. The codex has its own conventionalized processual affordance, turning of pages, but it cannot change its processes nor can it present its data in many ways. Therefore, it stays the same from one reading to the next. This, however, enables a complex poetics, one that requires deep attention, patience, and multiple reading times. This kind of reading is easily able to sort through the material of the poem and make thematic connections within it. As visualized by the draw mode (Figure 3), the poem creates a language game, a universe of its own, where everything is connected. Interpretive conclusions are made based on the view into the totality of the poem and its intratextual connections. Doing so we find, for example, that Simone Weil and a host of other underrepresented historical and mythical female figures make appearances in the poem. Through these figures the poem forges a view of an embodied understanding of the surrounding world. Reading the iPad application does not give rise to an interpretation that considers the text as whole, but it does invite the reader into engaging with more than only verbal means of understanding as it adds the visual image of the night sky and its processes are accessed through touching. The touchable screen interface is both a material and processual affordance not shared with the codex. Initially, the tactility of touch screens was thought of as a wholly new interface feature and it was conveniently forgotten that the codex is evidently as tactile and physically graspable as the iPad. The computer mouse and keyboard are similarly tactile and, as the touch screen, yield interactive results upon touching. Of course, I do not mean to say that there is no difference, but the difference does not lie in tactility per se. We touch these interfaces differently.

Strickland (2002, 6-7) writes on the other side of the invertible codex, Losing L’Una that 1.27

A universe

meets the hand that pushes against it in the form of

1.28 a limit

that it pushes up against, or seeks to circumvent; it rewards

1.29

a hand-mind that reaches for its breast, a mouth not held back […]

These lines associate not only with touching of the Vniverse’s sky interface, twelve years in the future at the time of writing, but also with the idea of an embodied exploration of the surrounding universe; a universe that rewards the “hand-mind” that pushes, seeks, and reaches. By foregrounding tactility, the Vniverse iPad interface brings touching back to view, and this is the difference in distinction to other interfaces. In sum, the

Vniverse iPad app, through its processes of drawing and encouraging a more personal engagement, in-corporates the factual tactility of the interface into its processes and into the act of reading.

CODA: WaveSon.nets and the Vniverse iPad Application as Cultural Interfaces

Lev Manovich uses the term cultural interface to describe a “human-computer-culture-interface – the ways in which computers present and allow us to interact with cultural data” (2016, 37). However, there is no need to confine interfaces to the computerized sphere. Lori Emerson defines interface as a “technology – whether it is a fascicle, typewriter, a command line, or GUI – that mediates between reader and the surface-level, human-authored writing”, and in the case of digital computers, also between the reader and what happens beneath the surface of the screen (2014, x). Using this broader definition of interfaces, I propose to define cultural interfaces simply as interfaces that present and allow us to interact with cultural data. By this account, a codex of poetry and an iPad poetry application are both clear examples of cultural interfaces. In addition, content streaming services like Spotify and Netflix can be seen as cultural interfaces, and so can, to some extent, social media and news application interfaces – insofar as cultural content is accessed, shared, discussed or promoted on them. The codex is an analogue interface and pertains to an older cultural medium than the digital iPad interface, now ubiquitous and quotidian. To conclude the investigation into the differences of their affordances, let us examine the different cultural conceptions these interfaces imply.

The analogy to analogue media is found in the title, WaveSon.nets. The continuous wave is often used to exemplify the analogue in contrast to the discreteness of the digital. There is a full stop in the middle of the word “Son.nets”, which breaks the continuity of the metaphorical wave and, in addition to cutting the wave into parts, the “.net” alludes to a web address, a digital affair. Moreover, dividing the word reveals the fact that letters of the alphabet are already discrete. The alphabet is digital as there is a finite number of discrete symbols that are permutated according to certain rules (cf. Cramer 2012).

Digital as discrete and permutable opens a broader view into the background assumptions of cultural interfaces. In contrast to analogue media, which were broadcast into television and radio sets as a predetermined and continuous signal, contemporary digital cultural content is divided into cultural pieces: a song, an episode of a television series, a piece of news, a poem in Instagram –these pieces can be accessed at the user’s convenience in whatever order. The affordances of digital platforms have also created entirely new cultural forms such as short videos, memes, and tweets that often, if not always, share the features of division, selection, and permutation affordance across the cultural field. Moreover, the user of a digital cultural interface expects that she can select her desired content as well as its time of consumption, its duration, and pace. In this respect, the static codex, while perhaps affording deep attention, can fail to appease a user who is accustomed to controlling the consumption of cultural goods according to a digital logic.

This digital cultural logic further entails the ideas of personal experience and individual, customized products. Unlike the predetermined broadcast of the old media style, the contemporary user expects to be able to select from a vast and open cultural tray of possibilities that is there to cater to their personal preferences. Indeed, most digital cultural interfaces make a point about emphasizing how their goal is to provide a satisfying experience that is individualized for the particular user or page visitor. Furthermore, there is a tendency to encourage affective tone for the selecting user. This is most visible in social media where we are asked to relate to all content through liking/disliking, hearts, frowns, and other iconic emotion states. Lastly, the cultural logic associated with digital cultural interfaces includes momentariness. Although there is nothing substantially ephemeral in digitality, as argued by Matthew Kirschenbaum (2012), the digital online environment is experientially ephemeral. The digital cultural interface updates itself with new content with every refresh of the page and for every user individually.

Therefore, the logic on which contemporary digital cultural interfaces run includes, first, the division of cultural content into discrete units that can be attended to separately, availability at all times, and for the duration that the user wishes.9 Second, it is seen as a value that the user is able to select the cultural parts they want, and the ethics of the interface is to proclaim that it is there to provide satisfying and customized user experience. The user can and should select their preferred content out of a vast, but preorganized array of items based on their affective preference. Third, the affective tone is further emphasized or even solidified by asking the user to rate the experience with emojis, stars, hearts, likes, and shares. And fourth, digital cultural interfaces are characterized by momentariness.

Let us now return to Vniverse with the digital cultural features of division, selection, affective tone, and momentariness in mind. In comparison with the 2002 analogue print book WaveSon.nets, which presents its material in continuous metaphorical waves, in the 2014 Vniverse iPad application we find the material divided into permutable parts. Furthermore, the application organizes its material in the form of a selection. Instead of beginning on page 1, as in the print book, I am encouraged to select a reading mode from a menu, for example the Oracle mode, and then to choose from a further selection of options. In the Oracle mode, I am asking the poem “what I love” and I get an answer whose meaning is constructed in relation to my present feelings, self-image, memory, identity, experience and so on. The affective tone of this question is clear. Furthermore, this answer, as most of the other pieces of poetry in the application, are momentary. They are selected by myself and seen and read in that particular way by myself only, and their meaning is similarly mostly meaningful to me in that moment – nobody else has read through that same trajectory with the exact same organization of text. These affordances produce personal and selective reading. To juxtapose it with a close reading strategy, outlined above, the goal is not to gather first all the evidence, to read it from beginning to end, make it cohere by finding patterns and significant details, to uncover the work’s inner structure, and then make conclusions based on all the information. Rather, the goal is to form and investigate ephemeral, passing connections, which draw more directly on the reader’s subjective background, present location, and state of mind. This is momentary, present-tense reading, through which one only gets glimpses of an overall structure. The application produces isolated poetical moments, which the reader can enjoy as such. Here we have passing moments whose meaning is formed in relation to the ephemeral reader. However, the application adds tactility and a visual element that we do not find in the codex form. The material and processual affordances foreground the corporeal aspects of reading, the “hand-mind”.

To reiterate, what the codex, the bound print book, then affords well is a meticulous reading of the whole totality with the background notions of unity, coherence, and intentionality. The codex interface allows the reader to spend time with the poem, to re-read and double read, to compare and juxtapose the elements of the poem freely. The codex affords the cognitive mode of concentration and deep attention as it does not offer other information streams except the one, text. On this interface Strickland’s poem becomes eminently close readable with its textual experimentation, thematic and symbolic depth, and a rich field of intertextual allusions; in other words, it rewards the close reader with its complexity, depth, and nuanced artistic arrangement.

9 I mean here the availability and control over duration of, for example, a certain episode of a television series or a song in a streaming service, mainly in contrast to the analogue logic of broadcasting. Perhaps paradoxically, the feature of momentariness is at the same time true, but it applies differently on different interfaces. I can reasonably expect to be able to listen to certain songs on Spotify until further notice, almost as if they were on my personal library, but I don’t expect to find the same post on social media or a piece of news on a newspaper website over and over again. This latter kind of momentariness has created a new cultural action, the screenshot, a kind of processual memorization and evidence gathering technique, afforded by most digital interfaces.

Now we are in the position to return to the usefulness of the concept of affordance: The codex as interface

affords close reading but does not enforce it; some readers will select a few Son.nets and discard the rest,

depending on their cognitive, cultural and situational settings. All readers will not try to make a thorough and unifying close reading. However, the specific textual features of a poem in conjunction with the interface medium, as I argue about WaveSon.nets, can invite a certain kind of reading. On the digital interface of the

Vniverse the same poem invites a different kind of reading, and the textual material of the poem is constructed

to afford presenting it on these different interfaces. As affordances arise in mutuality between the environment and the animal, the interface and the human, it is up to the reader what kind of reading will ensue.

The comparison between platforms I have pictured here is intended to both reveal common assumptions of reading on a print interface such as the codex and to investigate new assumptions created by digital interfaces. The affordances (material, processual, cognitive, and cultural) I have delineated can certainly be detailed further and other ones might be added. My purpose was to draw an initial frame for affordances that play a role in reading poetry and to look at Strickland’s “V-Project” through that conceptual lens. What the comparison shows is that the cultural interfaces of the codex and the iPad carry on with them not only whatever their text and/or application is and does, but also a full cultural context. For poetry in print and digital form, Strickland’s project attests to the capability of complementary coexistence.

Bibliography

Althusser, Louis. 2004. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. Eds. Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan. Malden: Blackwell.

Brillenburg Wurth, Kiene, Kári Driscoll, and Jessica Pressman (eds). 2018. Book Presence in a Digital

Age. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Bucher, Taina, and Helmond Anne. 2017. “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms.” The SAGE

Handbook of Social Media. Ed. Jean Burgess. London: Sage.

Calinescu, Matei. 1993. Rereading. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ciccoricco, David. 2012. “The Materialities of Close Reading: 1942, 1959, 2009.” Digital Humanities

Quarterly 6 (1). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/6/1/000113/000113.html. Accessed September

10, 2016.

Cramer, Florian. 2012. “Post-Digital Writing.” Electronic Book Review 2012.

http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/electropoetics/postal. Accessed September 10, 2016. Emerson, Lori. 2014. Reading Writing Interfaces: From the Digital to the Bookbound. Electronic Mediations 44. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Gibson, James J. 2015 (1979). The Ecological Approach To Visual Perception. London & New York: Psychology Press.

Gillespie, Tarleton. 2014. “The Relevance of Algorithms.” Media Technologies. Essays on

Communication, Materiality, and Society. Ed. Tarleton Gillespie, Pablo J. Boczkowski, and Kirsten A.

Foot. Cambridge, Mass & London: The MIT Press.

Hayles, N. Katherine. 2012. How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kangaskoski, Matti. 2017. Reading Digital Poetry: Interface, Interaction, and Interpretation. Unigrafia, Helsinki. Dissertation.

Kaptelinin, Viktor. 2013. “Affordances.” The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction, 2nd ed. The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/book/the-encyclopedia-of-human-computer-interaction-2nd-ed/affordances. Accessed January 7. 2019.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. 2012 (2008). Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination. Cambridge, Mass & London: The MIT Press.

Levine, Caroline. 2015. Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Manovich, Lev. 2016. “The Language of Cultural Interfaces.” New Media, Old Media. A History and

Theory Reader. Eds. Wendy Hui Kyong Chun and Anna Watkins Fisher with Thomas W. Keenan. New

York & London: Routledge.

Norman, Donald A. 1988. The Psychology of Everyday Things. New York: Basic Books.

Orlikowski, Wanda J. and Gash, Debra C. 1994. “Technological frames: making sense of information technology in organizations.” ACM Transactions on Information Systems (TOIS). Volume 12 Issue 2, April 1994. 174-207. New York: ACM.

Salmon, Christian. 2017. Storytelling: Bewitching the Modern Mind. Trans. David Macey. New York: Verso.

Sun H and Hart-Davidson WF. 2014. “Binding the Material and the Discursive with a Relational Approach of Affordances” Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Stanfill, Mell. 2015. “The interface as discourse: The production of norms through web design.” New

Media & Society 17(7): 1059–74.

Strickland, Stephanie. 2002. V. WaveSon.nets; V. Losing L’Una. New York: Penguin Books. ———. 2014. V: WaveTercets / Losing L'una. Denver, Colorado: SpringGun Press.

Strickland, Stephanie, and M. D. Coverley. 2002. “Errand Upon Which We Came.” http://www.thebluemoon.com/coverley/errand/home.htm.

Strickland, Stephanie, and Ian Hatcher. 2014. “Vniverse.” Version 1.2. iPad Application.

Strickland, Stephanie, and Cynthia Lawson-Jaramillo. 2002. “V:Vniverse.” Shockwave application. http://vniverse.com/. Accessed September 10, 2016.

Taipale, Sakari. 2014. “The affordances of reading/writing on paper and digitally in Finland.” Telematics

and Informatics 31 (2014) 532–542.

Wallot, Sebastian and Menninghaus, Winfried. 2018. “Ambiguity Effects of Rhyme and Meter.” Journal of Experimental Psychology. Vol. 44, No. 12, 1947–1954.

Wilhelm, Richard. 1967. The I Ching, or, Book of Changes. Trans. Cary F. Baynes; foreword by C. G. Jung. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Matti Kangaskoski is a postdoctoral researcher and a poet. His research concerns the cultural logic of digital interfaces and their influence on literary production. Kangaskoski has published two volumes of poetry and a novel. In 2019‒2020, he is Artist Fellow in Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, University of Helsinki.