IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 100

Paul Joostens (1889--

‐1960)

A Gothic Dadaist’s search for spirituality

1Adriaan Gonnissen

Abstract

This paper examines the search for spirituality of Belgian avant-garde artist Paul Joostens (1889-1960). Although known as a pioneer of Dadaism and (abstract) avant-garde art in Antwerp and Belgium during the tens and twenties of the past century, his later artwork, based on Medieval and mystical inspirations, is often neglected or misinterpret. Joostens was tired of always coming after the true revolutionary Parisian avant-garde artists. His ambition was to transcend this form of avant-garde in search for something more durable and personal, more spiritualized. His 'impure' artwork, as he called it himself, is the artistic legacy of a unique Gothic Dadaist.

Résumé

Cet article analyse la quête spirituelle de l’avant-gardiste belge Paul Joostens (1889-1960). Cet auteur est connu surtout comme un pionnier du dadaïsme et de l’abstraction avant-gardiste à Anvers et en Belgique dans les années 1910 et 1920. Sa production ultérieure, souvent d’inspiration médiévale et mystique, n’est pas reconnue à sa juste valeur, si elle n’est pas totalement méconnue. Joostens s’était lassé de n’être qu’un prolongement tardif des vraies avant-gardes parisiennes et son ambition était devenue de transcender l’avant-garde en vue d’obtenir quelque chose de plus personnel et de plus durable, mais aussi de plus spirituel. Ses œuvres ‘impures’, comme lui-même les appelait, sont l’héritage artistique d’un Dadaïste gothique hors pair.

Keywords

Dadaism, Gothic, avant-garde, medievalism, mysticism

1 This article follows the two-part retrospective exhibition ‘Cinema Joostens’ at Mu.ZEE, Ostend, curated by

Björn Scherlippens and the author of this essay. I would like to thank Phillip Van den Bossche, director of Mu.ZEE, for putting the images to my disposal. I would also like to thank Prof. dr. Hilde Van Gelder and my colleagues at KULeuven, dr. Mieke Bleyen, Ph D students Laurens Dhaenens, Jeroen Verbeeck and Miguel González Virgen for all their advice and help with the editing. Frank Hendrickx inspirer of the ‘Study Centre Paul Joostens, Hasselt’ deserves the biggest expression of gratitude, without him the research on Joostens wouldn’t have been where it is now. I also thank Frank Van Eeckhout for his feedback concerning content and for his cooperation in the research into the life and art of Paul Joostens.

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 101 “About the spiritual content, I leave it to everyone to freely interpret my

personal mysticism. The aesthetes, the authoritarian arts leaders will again not forgive my impure imagery. I did it so and could not do otherwise.”2

Paul Joostens knew that a major part of his oeuvre was highly undervalued. The artist noticed that contemporary art critics and buyers could not understand why he altered his course around 1925 by creating a mysterious artistic universe. He based his idiosyncratic art on the mystical Gothic past he admired, particularly the miraculous cathedrals and the spiritual art of Hans Memling. His ‘impure’ artwork consists of a combination of Gothic, mystical-spiritual and modern inspirations and was often criticized in reviews as being overly cerebral, dark, regressive, perverse and obsessively preoccupied with the female figure.3

Even today, art historians remember Joostens mainly as a pioneer of the avant-garde from the period before 1925. In those days the artist adopted a kind of dandyish lifestyle, enjoying the modern city life in Antwerp, frequenting cabarets, cafés and, most of all, his beloved movie theatres with his close friend Paul Van Ostaijen. He went to Paris with a select group of close friends and experimented with all of the major avant-garde -isms, from Impressionism and Expressionism to Cubism and Futurism. However, Joostens became mostly renowned as a Dadaist, creating (semi-abstract) collages and assemblages, influenced by the Merz of Kurt Schwitters and the mécano-érotique of Francis Picabia.

In 2005 some of Joostens’ collages and assemblages were part of the grand retrospective exhibition on Dada in Centre Pompidou. Joostens was the only Belgian mentioned, next to Clément Pansaers. Nevertheless, the catalogue summarizes the most widespread art historical vision on the artist’s life and art practice. It suggests that he found his most fundamental connection with the international avant-garde through a personal form of Dadaism, after which he lost his way due to mystical Medieval inspirations and the obsessional imagery of women. It was not until the 1950s, the text concludes, that he reconnected with (Neo-) Dadaism by making new assemblages.4

Few have thoroughly examined Joostens’ remarkable change of course, leaving large parts of his oeuvre unnoticed or pressing questions unanswered. Which factors and ambitions made the artist reorganize his artistic inspiration? What drew him to Gothic cathedrals and the art of Memling? What kind of images of spiritual order did he derive from this shift and how do they relate to Dadaism or to his characteristic imagery of female figures? Beginning in the eighties there has been a growing interest in the spiritual dimension of the avant-garde, with religion

2 Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/B1, ‘letter from Paul Joostens to Emmanuel de Bom’, 8 November 1931.

All citations in this text are author’s translations from Joostens’ native languages, either French or the Antwerp dialect. Joostens consciously used the word ‘impure’ to describe his own artwork, employing it in opposition to Jozef Peeters’ concept of pure imagery through abstract geometric forms, inspired by the avant-garde magazine De Stijl and the lecture of Theo Van Doesburg in Antwerp on February 13, 1920.

3 Joostens especially noticed the critiques of Roger Avermaete en André De Ridder. Paul Joostens wrote a prose

text about the critiques of Avermaete in the magazines Kunst en opbouwen (1931) and Volksgazet (1934) in: Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/H, Prose and poetry, ‘Over zijn schilderkunst en de kritieken van RogerAvermaete’, 1934. André De Ridder wrote a rather negative review on the work of Joostens in the magazine Sélection. Chronique de la vie artistique et littéraire 5 (15 February 1925), pp. 435-436.

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 102 often seen as a pivotal point.5 These studies can provide new insights into Joostens’ change of course, but my main source of research are the artist’s understudied manuscripts – his journals and texts. After all, he wrote that because he made art with ‘the intention to present an experienced reality […] it is therefore necessary to know my writings.’6

The search for artistic reinvention

For thirty-five long years – more or less since 1925 until his death in 1960 – Joostens ensconced himself in his workplace, which he called his ‘abbey’, and never left his hometown Antwerp again. During this ‘inner exile’, as Paenhuysen describes it, he marginalized himself from the world by literally plastering dark the windows of his place and breaking with most of his friends and fellow artists of the Antwerp avant-garde movement.7 He kept in touch with only a small group of acquaintances by correspondence. Joostens had in effect become a peintre maudit, a ‘good at nothing’, which was his destiny because of his egocentric isolation and his Dadaist refusal of any kind of conformism.8 The dandy almost completely disappeared then, he literally changed his fashionable clothes and hat for a poor bathrobe. The most notable aspect that remained from his former lifestyle was the cinephilia that lured him to his precious movie theatres every day and night. Nonetheless, he became more like a hermit and started to create a wholly artificial universe around him, with no place for plants, flowers, or even sunlight. He started to decorate his abbey with artworks, late Gothic figures, folksy Mary statues, building stones and pinnacles of cathedrals.

In 1926 he wrote a pessimistic letter to Michel Seuphor, a pseudonym for Fernand Berckelaers: ‘My artistic career ended in 1923. Since then I have been surviving. Everything has been done and it is no longer useful to run because one always starts late.’9 Seuphor, artist, writer, founder of the magazine Het Overzicht and advocate of the international (abstract) avant-garde in Antwerp, knew the artist well and had moved to Paris where he tried – unsuccessfully – to market Joostens’ art. There was no interest in the work of a young and unknown Antwerp artist who had merely followed and tried out the major avant-garde –isms. In 1919 Léonce Rosenberg, founder of Galerie de l’Effort Moderne and supporter of Parisian Cubists like Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes, refused Joostens’ hybrid brand of Cubo-Futurism. Metzinger himself had corresponded with Joostens in an effort to point out and adjust his stylistic inconsistencies, but he had turned a deaf ear to the Cubist’s advice.10

The artist was tired of being considered as always coming too late in relation to the true authoritarian voices in Paris and Berlin, and he eventually projected the Dadaist destructive

5 For instance: Maurice Tuchman et al., The spiritual in art – Abstract painting 1890-1985, County Museum of

Art, Los Angeles, 1986; Jérôme Cottin, La mystique de l’Art – Art et christianisme de 1900 à nos jours, Cerf, Paris, 2007; Traces du Sacré, Mark Alizart (ed.), Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2008; Frank Bosman and Theo Salemink (eds.), Avant-garde en religie. Over het spirituele in de moderne kunst. 1905-1955, 2009, Van Gruting, Utrecht.

6 Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/H, Journal, September 1953.

7 An Paenhuysen, De Nieuwe Wereld. De wonderjaren van de Belgische avant-garde (1918-1939), 2010,

Meulenhoff-Manteau, Antwerp, p. 253.

8 Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/H, Prose and poetry, ‘Artistes-Maudits’, September-December 1939. 9 Cited in: Rik Sauwen, ‘D’un monde à l’autre: Michel Seuphor et Paul Joostens’, in H. Henkels (ed.), Seuphor ,

1976, Mercator Fonds, Antwerp, p. 124.

10 Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/B2, ‘letters from Metzinger to Paul Joostens’, March 20, April 5 and

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 103 tendencies on himself, ending up tormented by a sense of uselessness and artistic aimlessness. This form of depression was also fuelled by the tension in his marriage to Mado Millot, an eighteen-year-old he had met in Paris at the time when he was well into his thirties. In the spring of 1924 the couple got married, but by the end of 1925 she had already left him. Although the signs of a major depression and/or creative impasse became noticeable, Joostens never really stopped working. On the contrary, his only therapy consisted of making art and writing, almost with neurotic diligence.11

Joostens was not the only one going through some sort of identity crisis, searching for a new impetus. Around 1925 many Belgian avant-gardists had to deal with this phenomenon. The Brussels artist Victor Servranckx, for example, one of the few Belgian abstract avant-garde painters who had been successful on an international level, took the avant-garde ideal of intertwining art and life to heart, devoting himself to the applied arts in order to make a veritable contribution to the modern world.12 Other artists and critics searched for an authentic Flemish style and became advocates of what is called ‘Flemish Expressionism’, characterized by sombre, earthly tones and figurative expressions that portrayed the harsh social realities of the working-class.

André De Ridder and Paul-Gustave Van Hecke, the main promoters of this form of Expressionism, stressed the connection between this so called authentic style and Flemish identity, clearing the way for Flemish nationalist connotations.13 In 1920 De Ridder and Van Hecke founded the gallery and magazine Sélection, favoring a group of painters like Constant Permeke, Gustave De Smet and Frits Van den Berghe. Thanks to the promotional strategies of De Ridder and Van Hecke these artists became popular, which also led to an art historical preference for their proclaimed ‘Flemish Expressionism’.14 Some of Joostens’ former friends joined them in the search for new career opportunities. The artist, on the other hand, refused to get involved and scornfully called the Expressionist style a ‘Bauernkunst’.15

Around that same time René Magritte and E.L.T. Mesens were giving birth to Belgian surrealism in Brussels. The two preeminent artists chose Joostens as their only fellow-countryman to work on the single-issue magazine Œsophage (1925), which still favoured Dadaists like Hans Arp, Max Ernst, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Francis Picabia, Kurt Schwitters and Tristan Tzara.16 But after the publication Joostens never again participated in the pursuits of the two key figures. Perhaps he did not see suitable career opportunities, or perhaps he just did not want to follow in the footsteps of pioneers anymore. At one time he even called the surrealist initiative of Magritte and Mesens a ‘turn to madness’.17 However, this statement could just as well have been a compliment, considering that Joostens never

11 Although he wrote that his career had ended, many of his artworks and writings are dated in the period

1923-1926.

12 An Paenhuysen, De heerschappij van het gepolijst staal. Victor Servranckx en de Belgische abstracte

avant-garde’, Feit en Fictie. Tijdschrift voor de geschiedenis van de Representatie, 6 (2005), 94.

13 An Paenhuysen, De Nieuwe Wereld, pp. 203-205.

14 Jean F. Buyck, ‘Het interbellum: ‘Kunst van Heden’ en het debat omtrent het Vlaams Expressionisme’, in J.

Buyck, In dienst van de kunst: Antwerps mecenaat rond Kunst Van Heden 1905-1959, 1991, KMSKA, Antwerp, pp. 129-142.

15 ‘A farmer’s art.’ Cited in: Rik Sauwen, op.cit., p. 142.

16 Christiane Geurts-Krauss, ‘E.L.T. Mesens: A biography and the new insights that E.L.T. Mesens brought to

bear on the evolution of perception’, in Mieke Mels and Phillip Van den Bossche (eds.), The Star Alphabet by E.L.T. Mesens – Dada & Surrealism in Brussels, Paris & London, 2013, Mu.ZEE, Ostend, p. 29.

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 104 completely distanced himself from surrealism. He once wrote in a personal question-and-answer mode: ‘Are the surrealists right? Yes, because they multiply our five incomplete senses […].’18

Although Joostens – as an individualist pur sang – would never again embrace a manifested style or collective ideology like surrealism, he did share the surrealist’s belief in a superior, transcendant reality that can only be reached by invoking the irrational powers of the subconscious and in the artistic practice as a research method towards this goal. According to Paul Van Ostaijen, who knew Joostens best, the artist had always been sensitive to the search for a higher, spiritual order. In 1917 Van Ostaijen already compared Joostens to a monk and wrote that he was a deeply religious artist who made art as ‘the result of long meditations on the eternal “why” of things.’19

By the end of 1926, six months after his pessimistic letter to Seuphor, Joostens informed him that he had managed to reinvent himself: ‘Poupoule paints again. But he left Cubism and all the other –isms behind. His only model and foster father is the grand and unique Memling.’20 Memling’s perspective of the hereafter and his evocations of the divine made Joostens realize that the art of tomorrow should not be about technical ism-like discussions, which he considered typical of the international avant-garde movements. Rather, he began to favor reflection and the search for inner values and personal spirituality. In other words, the search for an authentic religion.21

Rajesh Heynickx noted that Joostens’ form of depression led to some sort of conversion, much like Hugo Ball who, during one of his Dada happenings at Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich, could not suppress memories of his Catholic youth while wearing his ‘magical bishop’ cubist costume of cardboard cylinders, a big hat and paper claws.22 After that experience Ball became some sort of mystic and wrote books like Byzantine Christianity (1923), demanding a return to spiritual individualism. Many Dadaists shared his call for a life and art of spiritual order, eventually turning to surrealism. Richard Huelsenbeck, another key figure of the Dada movement in Zürich, wrote in his last Dada manifesto (1949):

‘Surrealism undertook to realize the spiritual aspiration of Dadaism through an artistic direction; it strove for the magical reality which we as Dadaists first disclosed in our constructions, collages, writings, and in the dances at Cabaret Voltaire […] the work of the Dadaists, we firmly believe, makes it clear that the goal of Dadaism was human development, towards spirituality and freedom […] Art is spiritual and the first characteristic of the spiritual is freedom […] Yet precisely because art is spirit, it has the mission to expose the unspiritual’.23

18 Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/H, Journal,

19 Paul Van Ostaijen, ‘Over het werk van Paul Joostens’, Vlaamsch leven 49 (1917), 771-775. 20 Ibid., pp. 144-145.

21 Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/H, Journal, September – November 1950, p. 196.

22 Rajesh Heynickx, Meetzucht en mateloosheid. Kunst, religie en identiteit in Vlaanderen tijdens het

interbellum, 2008, Uitgeverij Vantilt, Nijmegen, p. 213.

23 Published in: Robert Motherwell (red.), The Dada painters and poets: an anthology, University Press,

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 105

‘The Gothic adventure’24

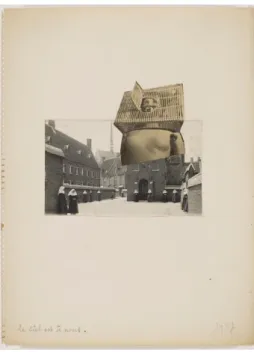

In 1950 Joostens wrote in his journal the text ‘The Gothic adventure’, in which he looked back on his life and art practice.25 He declares that the Gothic was in his blood by heritage and remembers nostalgically how he, as the son of a stonemason, spent his youth in the attic and garrets of his parental home where he was impressed by an altar and polychrome stuccos. In his father’s workshop he discovered decorative rosettes, corbels, pinnacles and parts of stained glass windows of cathedrals. As a young boy he had a collection of postcards with pictures of the cathedrals of Chartres, Amiens, Reims, Beauvais and Rouen, which he would then copy.26 He spent his summer holidays in Bruges, where he had the opportunity to visit two key exhibitions on the Flemish Primitives: ‘Les Primitives flamands et l’art ancien’ in the summer of 1902, and in 1907 the exhibition on ‘Het Gulden Vlies’, which he always remembered. ‘The Memling II’, the name that the artist gave to a cluster of works he had made since his self-proclaimed reinvention, is a set of drawn and painted cathedrals, churches and castles. He also expressed medieval piety through a variety of Madonnas, devout churchgoers, reliquaries, or through images reflecting the security and tranquility of the walled city of Bruges, the city of Memling. Art critic Roger Avermaete immediately dismissed Joostens’ so-called neo-Gothic art and denounced it in his reviews as a ‘strange ailment’, a ‘mystical-symbolist-Gothic disease’.27 However, Joostens’ art has little to do with a Gothic Revival like that of true Neo-Gothic art. Except for a few remarkable paintings, like ‘Easter’, the artist did not meticulously copy techniques and themes of fifteenth century artworks as a true Neo-Gothic artist would. (Fig. 1)(Fig. 2)28.

As the artist’s own mindset, ‘Joostens’ Gothic’, is characterized by a hybridization of Medieval iconography and modern reminiscences, Coronation with Self-Portrait (1931) shows the Madonna – a sculptural figure rather than a woman of flesh and blood – crowned by messengers of God against a dynamic background of colourful planes. The Cubist, planar structure and futuristic dynamic of the early Joostens had not quite disappeared in the thirties. His self-portrait

24 Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/H, Journal, May-June 1950, p. 80. 25 Ibid., May-June 1950, p. 80.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid., Prose and poetry, ‘Over zijn schilderkunst en de kritieken van Roger Avermaete’, 1934.

28 All images in this article – unless specified otherwise – have the following creditline: Photo: Steven Decroos;

Courtesy of Mu.ZEE, Ostend.

Fig. 1 Christmas, 1927. Oil and pencil on canvas,

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 106 is discernable on the left side of the painting, where he appears as the contemplative witness of this hybrid scene, which is dominated by the mannequin-like Madonna.

‘The Gothic state’, as Joostens defines it, consists of a ‘disposition of the mind tending towards a protestation against the works imposed by nature. This dissatisfied state of mind wants to replace the unbridled creation with an artifical construction whose quintessence is the imprecation of the enforced life.’29 In other words, the Gothic state is his Dadaist version of the road to transcendence, entering into a spiritual realm by way of a lifelong artistic search for artificial creation, especially the creation of the ideal mechanical woman, the summit of artificiality.30 The sculptural Madonna is an early example of this search, while other female imagery will be discussed further on.

Many similarities can be seen between Joostens’ definition of ‘the Gothic state’ and the slogan he wrote down in his last will: ‘My Dadaism: realizing transcendence, responding by the mind.’31 In the artist’s personal, artificial universe there is absolutely no difference between Gothic and Dadaism, both are fused in an intellectual artistic effort. This is the reason for which the Gothic inspired works should perhaps be considered as the work of a Gothic Dadaist. Seen that way, Joostens’ Gothic inspiration becomes less of a strange anachronism between two Dadaist episodes in the twenties and fifties, and more of a period of personal reinterpretation of his continuously Dadaist thinking.

The nuance of this intrepretation is necessary to thoroughly understand the artist’s oeuvre, because the return to traditional modes of representation in itself was not unusual for an avant-garde artist around 1926. In fact, Joostens’ artistic shift can be considered as an example of a ‘rappel à l’ordre’, a concept coined by Jean Cocteau in 1926, the same year Joostens wrote his letters to Seuphor.32 Like many other European avant-garde artists around this time, Joostens embarked upon a project for the reinstallment of traditional values of high art as a response to the incipient and growing academicization of what had been bold avant-garde statements, such as abstract or anti-art.

Benjamin H.D. Buchloh has noticed the first signs of this European avant-garde shift already happening in 1915, shortly after Marcel Duchamp’s first introduction of the readymade and Kazimir Malevich’s painted black square. He gives the example of Picasso who, in 1915, suddenly decided to draw a portrait in the manner of nineteenth century artist Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres of the Cubist poet Max Jacob – who had just converted to catholicism – disguised as a Breton peasant. Buchloh states that Picasso’s and Jacob’s sense of ‘historicist eclecticism’ became a new type of avant-garde program after the publication of Cocteau’s Le

rappel à l’ordre in 1926.33

29 Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/H, Journal, April-May 1936, p. 83. Published in: Adriaan Gonnissen

(ed.), Paul Joostens – manuscripts and essays, 2014, Mu.ZEE, Ostend, pp. 139.

30 The first author who substantiated the connection between the mechanical and the idealized woman figure

was: Frank Van Eeckhout, ‘Our Lady of the Holy Pushpin - About Joostens’ highly impure imagery, women, girls and stars’, in Adriaan Gonnissen (ed.), op. cit., pp. 90-120.

31 A copy of the testament, titled ‘Paul Joostens: Ceci est mon seul et unique testament’, can be found in a

private collection: Hasselt, ‘Research Centre Paul Joostens’, Frank Hendrickx.

32 Translation : ‘Return to order.’ Jean Cocteau, Le rappel à l’ordre (Paris: Stock, 1926).

33 Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, ‘Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression: Notes on the Return of Representation

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 107 In 1935 Joostens wrote in a whimsical and at the same time provocative way that his own art was more rich and solid than Picasso’s, exactly because he, Joostens, took the Medieval art tradition to heart in search of the spiritual. The engaging fragments of the Gothic past, of cathedrals and of Memling’s art, were in his opinion timeless spiritual idealizations, paragons of intelligent ordering, inner protection and personal devotional contemplation. Those were values that he could not find anywhere in modern times and art, not even in the art of Picasso. ‘In the [playful] domain of Picasso, the draftsmen of Mickey [Mouse] are better.’34

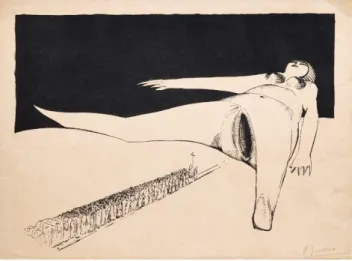

Rajesh Heynickx has noted that although contemporary art critics repudiated Joostens’ artistic shift, it didn’t come as a surprise that the artist did get appreciation for his ‘Gothic rebirth’ from another party: the Catholics. In 1928 Joostens even became a member of De Pelgrim, an alliance of Catholic Flemish artists who congratulated Joostens on his ‘return to God’.35 But this was not the reason for which Joostens signed up. It is important to bear in mind that, for instance, a few years earlier Joostens had made his cartoon-like series Les Mollusques, with La Procession as an authentic expression of his Dadaist urge to ventilate brutal, strident and blasphemous humour with a sense of perversion (Fig. 3). In this work, a religious procession, with the cross in front of the march, walks towards the gigantic vagina of a huge female figure lying on her back. Wisely, Joostens did not show this part of his oeuvre to the members of De Pelgrim. Joostens only signed up because the organisation provided the artist with a steady income and a market to sell some of his artwork. Eventually Joostens could not keep up appearances and withdrew his membership after a few exhibitions. As usual, he was unable to align himself with the strict regulations of De Pelgrim, which stated that deepening fate had to go hand in hand with a strong Christian community art and Flemish nationalist dimensions.36

Joostens could not subscribe to an art in service of a right-wing plea for Flemish nationalism. It must be argued that the artist never concerned himself with a political agenda in his artwork. In fact, he radically rejected all Flemish nationalist tendencies, and this rejection could be an additional explanation for his refusal of Flemish expressionism. In his journal he declares that Belgium is a country made up of consecutive cultures and without clear characteristics of identity. According to Joostens, Rubens was more like an Italian, Van Eyck was a true Dutchman and Memling had his origins in the Rhine area. ‘What is typically Flemish? The beer

34 Ibid., Journal Z, July 1935, p. 38.

35 Rajesh Heynickx, ‘Even the air is made of it’, in Adriaan Gonnissen (ed.), op. cit., p. 81. 36 An Paenhuysen, De Nieuwe Wereld, p. 266.

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 108 perhaps? […] Where does Gothic come from? And renaissance? And rococo? And the modern? By coincidence?’37 As a result, Joostens’ Medieval inspiration should not be considered as an attempt to appropriate the art of the Flemish primitives and cathedrals as if they were authentic elements that could be employed towards the formation of a Flemish identity.

Furthermore, Joostens actually wanted a free

(Dadaist) spirituality. He despised the form of life, history and art determined by dogmatic Catholicism as De Pelgrim prescribed it and as he had experienced during his education at a strict institution of Jesuits. During the First World War, Joostens had been indignant about what he considered typical ‘sadistic axioms’ of the Catholic Church, which gave people false hope by promising that the war would end if one conscientiously kept praying to God.38 Joostens thougt this kind of Catholic faith both oppressive and restrictive of the search for the spiritual self. Spirituality should in his opinion not be about submitting to an antropomorphised image of God.39

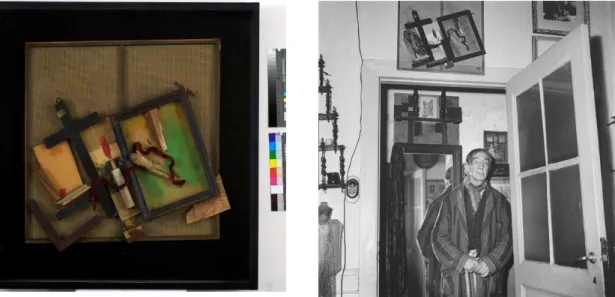

The writings of Frank Bosman and Theo Salemink indicate that many avant-gardists searched for a religion against the grain and tried to resist their religious education but could never break away from it entirely.40 It is clear that certain aspects of Joostens’ Catholic education did stick, as the late assemblage titled INRI (1950) demonstrates. (Fig. 4) Pieces of wood, cardboard and paper are assembled in the middle of a frame which in turn contains a smaller frame as well as traditional Christian symbols like the cross, the figure of Christ and the burning candle. The cross is crooked and an armless Christ no longer hangs on the cross. A stream of blood, symbolized by a red wire, loosely connects the cross with the figure and the candle. Although this artistic act of assemblage could be interpreted as blasphemous and iconoclastic, Joostens hung his artwork over the doorway, as it were a conventional crucifix. (Fig. 5) Moreover, it can be stated that these very personal box constructions were not really intended to ever be exhibited, because they never left the workplace during the artists’ life and served solely in building the Dadaist’s personal sanctuary.

37 Ibidem, Journal D, January-February 1936, 55. Also cited in: An Paenhuysen, op. cit., p. 267. 38 Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/H, Journal, February-March 1941, p. 61.

39 Ibid., February-March 1950, p. 71.

40 Frank Bosman and Theo Salemink, ‘Avant-garde en religie in een tijd van Nada’, in Frank Bosman en Theo

Salemink (eds.), op.cit., p. 8.

Fig. 4 INRI, 1950, Galerie Brockstedt, Berlin Fig. 5 Paul Joostens’ studio Venusstraat, 1958-1960, private collection

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 109 Fig. 7 Marlène, 1937,

Private collection Fig. 8 Cover Piccolo

Magazine, 22 August 1937

(Female) imagery of spiritual order

Although the ‘abbey’ was Joostens’ creative comfort zone, real spiritual experiences befell him mainly in the ‘cinema, my only real and grand church’.41 For him, the darkness and the rhytmically moving images replaced the church, turning the movie theatre into a modern cathedral that fulfilled the artist’s spiritual needs. Only the luminous, white screen could bring the actresses of Hollywood to life, making him fall ‘crazy in love with my three goddesses Greta, Brigitte and Marlène’. The mysterious aura and the sense of unreachability that surrounded actresses like Marlène Dietrich made it possible for the artist to accredit them with divine qualities. ‘Marlène you are the closest to the divinities of Leonardo Da Vinci.’42

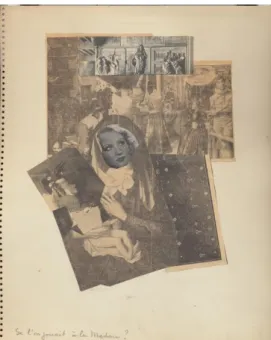

Si l’on Jouait à la Madone (‘If one plays with the Madonna’) shows the playful transformation

of a cut-out photographic reproduction of a Medieval Madonna and Child painting. (Fig. 6) A movie star, who seems to be diva Brigitte Helm, lends her face to the body of the Madonna. Joostens idealizes the female Hollywood stars in his artwork, like icons that irradiate the purity of a Medieval Madonna. Such artistic gestures could be reminiscent of some of the poems of American poet and film philosopher Vachel Lindsay, who made similar idealizations of movie stars as goddesses. Lindsay also wrote that cinema contributed to the senseless mess of modernity, arguing often that the distinctiveness of the cinematic medium lays in its ability to fragment the world into discrete images and to recombine these at will.43

Although Joostens probably wasn’t aware of Lindsay’s ideas, it is possible to draw clear parallels. As an admirer of Marlène Dietrich, Joostens, for instance, cut out a photographic image from the popular Belgian entertainment magazine Piccolo and used other fragments of photographic reproductions to recombine them into a layered portrait of his Goddess,

41 Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/H, Journal V, 1934, pp. 36-37.

42 Ibid., August 1938, p. 271. Published in: Adriaan Gonnissen (ed.), op. cit., p. 144.

43 Laurence Goldstein, American poet at the movies, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 1994, pp. 19-35. Fig. 6 If one plays with the Madonna, 1937,

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 110 mysterious and elegant. (Fig. 7) (Fig. 8). ‘Living is cinema, Dada is cinema’, wrote the artist.44 It is not surprising, then, that in the late thirties Joostens discovered the Dadaist photomontage as a suitable medium to visualize his spiritual experiences. The technique was ideal for juxtaposing and combining images, in an almost cinematic manner, in order to generate new meaning. In 1937 he made his first series of more than 170 Dada photomontages, titled Le

Royaume des Choses inutiles.45 The series can be read and looked at as a clever sketchbook, containing – among many other aspects of the artist’s rich oeuvre – building stones of the artist’s

44 Jean F. Buyck (ed.), Paul Joostens, de cruciale jaren. Brieven aan Jos Léonard, 1919-1925, 1995,

Petraco-Pandora, Antwerpen, p. 226.

45 Translation: ‘The Kingdom of useless things’.

Fig. 7 Marlène, 1937, Private collection

Fig. 8 Cover Piccolo Magazine, 22 August 1937

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 111 spiritual female imagery.

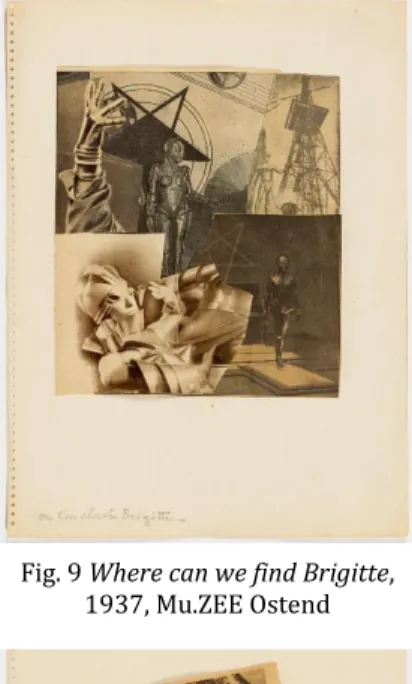

In Joostens’ spiritual search for the ideal, mechanical woman it is no surprise that ‘The Frankenstein movies played an important part in my being […] I am a little bit like that: alone, despising the works of God and searching for the artificial.’46 The German sciencefiction film of Fritz Lang, Metropolis (1927), one of the artist’s all time favourites, almost completely fulfilled his ideal fantasy. Brigitte Helm plays the leading character Mary, a name which, of course, can immediately bring to mind religious connotations. This moral fable takes place in a futuristic society, in the year 2026, where only the rich live above ground. The prophetic Maria pleads for the poor, underground workers, but is imprisoned by the mayor and replaced by a controllable female robot. In an erotic dancing scene male spectators are stunned and burn with desire for this mechanical woman. The power of female seduction and the appeal of divinity are all brought together in one machine, brilliantly interpreted and embodied by Helm.

Ou l’on cherche Brigitte? [Where can we find Brigitte?] Bas le Masque [Remove the mask]

(1937). (Fig. 9) (Fig. 10).

46 Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/H, Journal CC, November-December 1935, p. 23. Published in: A.

Gonnissen (ed.) op.cit., p. 135.

Fig. 9 Where can we find Brigitte, 1937, Mu.ZEE Ostend

Fig. 10 Remove the mask, 1937, Mu.ZEE Ostend

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 112 Joostens’ obsessions certainly reveal more about the artist than they do about his subjects. The portraits he makes of his beloved movie stars are not solely the outcome of his fascination with those particular women or with cinema in general: they can also be considered self-portraits that explore his own mind. The early painting Futurisme (Asta Nielsen) (1917) is the most literal example. (Fig. 11) While still browsing through the avant-garde -isms, Joostens had already found his first Goddess of the white screen, the Danish star of German silent film: Asta Nielsen. Known for her appearance in the erotic Danish film Afgrunden [The Abyss] (1910), she played very different roles ranging from a dancing-girl and prostitute to a succesful businesswoman wearing manly pants in Die Börsenkönigin [The Queen of the Stock Exchange] (1916). Joostens clearly loved powerful women, heroines of Hollywood who could play any kind of female character, confident and independent. He even identified himself with them, painting his Asta-portrait with his own distinctive nose. The search for the spiritual is rooted in the meditation on his Goddesses, and is also used to create a mirroring self-image.

The creation of an ambivalent female figure is in itself not an iconographical invention of Joostens, as Sofie Verdoodt argues. Many fin-de-siècle Symbolists like Fernand Khnopff, to name just one, played on this same register.47 In many ways Joostens’ most important artistic invention and symbol of his oeuvre, his artifical poezeloes, recalls Symbolist imagery, driven not only by religious sentiment but also by some kind of voyeuristic sexuality or fetishism. The

poezeloes is the result of Joostens’ free association of his obsessional images of different

women; it shows characteristics not only of classic archetypical female figures like the Medieval Madonna, the Biblical or mythological Salome, Judith and the androgynous sphinx, but also of the prostitute or the adolescent girl, along with modern symbols like, for instance, the dancing-girl, the mannequin or the movie star. (Fig. 12)

47 Sofie Verdoodt, ‘Life is cinema: The cinephilia of Paul Joostens’, in A. Gonnissen (ed.), op. cit., p. 58 Fig. 11 Futurism, 1917, private

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 113 The operation for the eclectic formation of the female figure can remind us of Buchloh’s notion of historicist eclecticism that became the new avant-garde program after Cocteau’s book. Moreover, this programmatic change also functioned in relation to another ambition, since Cocteau also suggests ‘that where audacity had become convention – as in the parisian avant-garde – the resurrection of the old modes could create a special kind of novelty: that looking backwards the artist could even more dramatically look forward.’48 Therefore, Joostens’ formal reorganization was not solely a plea for an antimodernist stance by returning to the past Gothic, but also a call for radical innovation – a true avant-garde feature. In the photomontage Le Ciel

est à nous (the sky [or heaven] is ours) (1937) Joostens uses a photographic reproduction of a

Medieval béguinage and pastes on top of it a cut out from a photographic reproduction of the surrealist André Masson’s mannequin. (Fig. 13) The naked, muzzled and sexually-charged mannequin – a symbol of modern times and art – is a long way from the béguinage, an oasis of order, discipline and tranquility. Joostens shows us a disenchanted, modern Western world that is consciously made ‘impure’, perhaps precisely to emphasize this disenchantedness.

These kind of photomontages and other artworks are examples of art as a result of an artist’s attraction towards the deviant and the heretical, art against the grain. Peter Gay proclaims this to be a crucial feature of modernism and avant-garde in general.49 In the case of Joostens’ artwork, An Paenhuysen has noted that by playing times, cultures and ideologies off against one another this particular photomontage, Le ciel est à nous, suggests some kind of

avant-la-lettre postmodernism.50 Building on that premise, one can argue that, while aiming for some kind of countermove against modern rationalism, non-spiritual avant-garde art and insitutional Christianity, Joostens was also intent on developing a kind of postmodern spirituality.

48 Christopher Green, Léger and the avant-garde, London, 1976, p. 218 ; also cited in Benjamin H.D. Buchloh,

op. cit., p. 51.

49 Peter Gay, Modernism: The Lure of Heresy: From Baudelaire to Beckett and beyond (Random House, 2007). 50 An Paenhuysen, De Nieuwe Wereld, p. 264.

Fig. 12 When female legs…, 1957, Private collection

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 114 Therefore, one can see parallels between Joostens’ artwork and Marcel Poorthuis’ writings on the ‘new mysticism’, which started in the nineteenth century and had a big influence on modernism and the avant-garde. Poorthuis draws a direct line between certain artists of the fin-de-siècle and certain artists of the avant-garde, who noticed both the emergence of a new type of mysticism in which aspects of eastern religions, Medieval times and other historic periods were ever present. He gives the clear example of the drawing The Sphinx by Symbolist Jan Toorop, who became a catholic later in life, which not only contains the Egyptian symbol, but a Buddha-figure and Medieval cathedrals as well.51

The spiritual content in Joostens’ artwork aligns with this new mysticism and was made up of reminescences of past traditions, not only of Medieval Madonnas, cathedrals and paintings of Flemish Primitives but also of mythology and Biblical or ancient themes. Even Buddhism played an important part in Joostens’ artistic inspiration. He once wrote in a letter to Paul Van Ostaijen that he made a study on Buddhism.52 Also, Paul Neuhuys, one of Joostens’ closest friends once wrote that the artist ‘called himself a Buddhist, because he simply ignored other religions’.53 Like many artists, writers and philosophers from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, he saw Buddhism as a mere human, peaceful philosophy cleansed of the history of war, the dogmatics, the rituals and miracles which are inextricably associated with Western Christianity. A picture of a younger Joostens relaxing in his workplace – probably situated in De Moystraat 36 in Antwerp – shows how the figure of Buddha had a central place in his living room. Buddha also appears in several drawings and photomontages. (Fig. 14)

51 Marcel Poorthuis, ‘Nieuw mysticisme en moderne kunstenaars – Bronnen diep uit de negentiende eeuw’, in F.

Bosman en T. Salemink (eds.), op. cit., p. 72; Phil Mertens compared Joostens to Toorop already in 1976: Phil Mertens, ‘Geest en klimaat rond Paul Joostens’, in Flor Bex (ed.), Paul Joostens (Antwerpen: ICC, 1976), p. 71

52 Antwerp, House of Literature, J4453/B1, ‘Letter from Paul Joostens to Paul Van Ostaijen’, 8 February 1921. 53 Cited in: Henri-Floris Jespers, “Exit Paul Joostens (1889-1960), blog de la fondation Ça Ira, 10 february 2008.

http://caira.over-blog.com/article-16518001.html

Fig. 13 Le ciel est à nous, 1937, Mu.ZEE Ostend

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 115 The particular mindset of new mysticism, Poorthuis argues, consists of forging a personal mysticism out of different accessible spiritualities, regardless of the boundaries of time, culture or place. This kind of eclectic formation ‘would become the feature of a postmodern spirituality and at the same time it connects with mystics of all ages’.54 All of these different spiritual influences support the implementation of a personal mysticism, an avant-garde feature that has

roots deep in the nineteenth century, with clear similarities with Symbolism. This insight seems to fit Joostens’ life and art practice quite well.‘Where I withdraw myself to (beyond life), I will definitely not find a response or an intelligible God to talk to, but I will find myself, nice and proper, without having to take anything into account, without any commitments. Nothing but life purged of tragedy. Perhaps that’s the mystic.’55

But still, Joostens’ artwork distinguishes itself from other artists with similar inspirations on one crucial level. Joostens’ spirituality also included artistic elements that would become important in a time yet to come. Icons of popular-culture such as cinema’s and Hollywood movies or stars play a crucial role in the artistic universe of the artist, as discussed above. One could argue that Joostens artistic inspiration shows characteristics of those of a fin-de-siècle artist, a true avant-garde artist, but also of a visionary artist who draws lines from the past to the future.

Conclusion

Fifty-five years after Paul Joostens’ death, the interpretation of his work still presents many challenges. But the historical distance we have today, and the new available sources that have come to light in recent times can provide us with original insights into the (spiritual) life and art of Joostens. There is more to the artist than just a controversial figure bogged down in a dark, Gothic and perverse circle of vice. His project for an artistic reformulation based on the

54 Marcel Poorthuis, ‘Nieuw mysticisme en moderne kunstenaars – Bronnen diep uit de negentiende eeuw’, in

Frank Bosman en Theo Salemink (eds.), op.cit., pp. 57.

55 Published in: Rik Sauwen, ‘Paul Joostens: Le refus à la nature’, in Rik Sauwen, ‘L’esprit dada en Belgique’

(unpublished master’s thesis, Catholic University of Leuven, 1969), 139.

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 16, No.3 (2015) 116 art of the ancient cathedrals, on Memling’s paintings of Madonnas and of the hereafter was rooted in the frustration of always coming too late in relation to the Parisian avant-garde. Yet, Joostens completed his project through his Dadaist search for artificiality, which was the artist’s personal attempt to return to a level of both spirituality and cerebrality, two fundamental aspects he could no longer find working side by side in modern times and art. Dadaism and Gothic are mixed together in an oeuvre that is consciously made hybrid.

Joostens, for instance, turned Hollywood movie stars into Medieval Madonnas and cinemas into cathedrals. By doing so he developed a personal and eclectic spirituality based on various inspirations of different times, places and cultures. His artistic inspiration aligned with the new mysticism that influenced many artists since the fin-de-siècle and also left its mark on modernism and avant-garde art. Joostens’ art production could not accept a contingent or transitory modernism. Instead, the artist searched for a more durable mechanism, an antimodern modernism or a modernism against the grain. He aimed at the ambition to create a personal, new avant-garde, apart from the recuperated -isms. One can see Joostens as a symbolist artist that created an art form that was in fact more avant-gardist than one would expect at the time. This was the real lifework of a unique Gothic Dadaist.

Adriaan Gonnissen is Asst Professor and PhD Candidate at the University of Leuven. His research

focuses on interwar avant-garde in Flanders. He has co-curated various exhibitions on the topic and coedited two books: Gonnissen, A., Scherlippens, B., Van den Bossche, P. (2014). Paul Joostens -

Oeuvre/Works. (Scherlippens, Björn, Ed.). Mu.ZEE, Oostende; Gonnissen, A., Heynickx, R., Sauwen,

R., Van Eeckhout, F., Verdoodt, S., Van den Bossche, P. (as contributor) (2014). Paul Joostens -

Manuscripts and Essays. (Gonnissen, Adriaan, Ed.). Mu.ZEE, Oostende.