HAL Id: hal-02306137

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02306137

Submitted on 4 Oct 2019

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License

exist ?

Louis-Pascal Mahé, Terry L. Roe

To cite this version:

Louis-Pascal Mahé, Terry L. Roe. EC-US Agricultural trade : Do political compromises exist ?. [Uni-versity works] Inconnu. 1990, 27 p. �hal-02306137�

r

l rr Ir

Ir

t- r-I ir

Ir

I tt,

8C-U$.rioc byIr. P. llÀEE*, T. Ir. R(f,* *

*

E-It-s.À.-

I)épartenent iles $ciences Econoniqueset

sociales rle Rennes-65, rue de St-Brieuc

-

3b042 lenneg Cédex (France)**

Ilepartnentof

Àgricultural

and Àpplieil Econonics-

University ot Ilinnesota-

231 classroonoffice

Building-

Lgg4 BufordÀvenue

-

ST PAUI, ttlt{tùEstfÀ 55108 (U.S.À.)October t99O i I I I 1 I I I I I i 1 I I i l I i I j i I I I I l I l i 't l

I'

t,

t

t-L

L

L

t

t

ElC-ITS

AGFèICt'I.TTIGèAI-

TFÙADE

FÈEI-ATTOI\IS

.

r-,L

r-L

CONTRIBUTION TO THE LIBEB AMICORUM

IN HONOUR OF JAN DE VEER,

DIRECTOR OF THE LANDBOUIV-ECONOMISCH INSTITUUT

t.P. MAHE and T,L. ROE ( 1)

october 1990

EC-US AGRICULTURAL TRADE RELATIONS :

DO POLITICAL COMPROMISES EXIST ?

Contents

introduction

I.

Three paradoxesin

the EC-US agricultural trade confllcta. The two big players can help or hurt each other, but to a llmited

extend

b. Economic efflciency has a limited role

ln

the deslgn and the reformof the CAP

c. The US position

ln

the CATTis

a tactical rather than a compromiseposition leading to a treaty

II.

Political weights of commodity groupsin

the EC and the USa. Revealing the political weights of varlous farmer groups

b. A brief interpretation of the relative weights

III. Feaslble compromises between the EC and the US

a, Partial liberallzatlon and decoupled compensatory payments

b. Tariffication and rebalancing open avenues for a treaty

Summary

-

ConclusionsReferences

I - t.P. l{ÀffE is professor - Dept of sciences sociales EI$À ftennes - france

T.t' ROE is professor - Dept of lgrlcultural Econoric university of !{innesola.

f--L t r- (-r I r t I L t I l t-i t L-l

t.

L

r'

EC-US AGRICULTURAT TRADE RELATIONS :

DO POTITICAL COMPROMISES EXIST ?

Introductlon

The history

of

EC-US conflicts about the Common Agriculturai Poiicyhas been long and rich

in

events. The US has never accepted the foundlng prlnclples of the CAP, and their implicatlons. l[hile some periods were ratherquiet, sudden outbreaks

of

confliets have been recurrent. Evenif

the

USfinally accepted that a protectionlst CAP was the economic prlce to pay for the political gain

of

a united Europe,it

couldnot

llve

with the

variableIevy system and even less wlth

its

recent useof

export restltutions on SCsurpluses. Starting

in

early 1980's attempts to complete the CAP by a tax onfats and oils

or

bya

ceiling on cereal substltute imports have triggered a swlft retaliation by the US (Hathar,vay, Tracy, Petlt).Naturally, the opposing views on agrlcultural policy reforms

in

the ECand the US have reached

a

cllmaxin

the GATT negotlatlonsof

the ongoingUruguay Round. The basic position

of

the USls a

compiete eliminatlon offarm support policies

as

long as theyare

linkedwith

production levels, while the EC is keen to trade a commitment to a llmited cutin

price supportfor

a

rebalancingof its tariff

structureln

favorof

imported feeds. Other GATT members are also playersin

that

game andthe

EC export refund systemis

the main târgetfor

complaints.In

October 1g89,the

US made anew proposal

for

the

transltlon period toward decoupled farm programmes,which basically required

an

elimination of export subsldles over 5 years andof

other output-linked support policies over 10 years, Although deflned in terms of policy instrumentatlon, this scheme of agrlculture policy ad,justment

r-incteases the pressure on the EC

;

and a profound reform of the CAPls

theactual target pursued by the US.

in

this

paper, we do not intend to revlervall

the lssues relatedto

the EC-US agricultural tradeconflict

whichhas

attracteda

largebody

of research (see cathle,curry

ed., Moyer and Josllng,for

recent surveys). wewould like however

to

adress three questions: (i)

whyis

the confllet solntense while evidence exists

that the

slzeof

interactlonis

realbut

not considerable?

(i1) whyis

the EC reluctantto

llberallze while the economicgains are large and, correspondlngly ïrhy

is

the US position led onlyby

âquest

for

welfare efflelencyof

free trade? (iii)

last,

can we reveal theactual pollcy obJectives embedded

in

the current farm programmes and by doing so identify areas for mutual agreement, l.e. for a treaty ?In the first

section we analyse three paradoxesin

the

EC and USpositions

in

the current GATT roundof

negotiations.In

the second sectionwe present estlmates

of the

relative political weightsfor

various soclalgroups affected

by

the

current programmes. The resulting polltical value function is then used to dellneate areas for feasible compromises.I -

Three paradoxesln

the EC-US agrlcultural trade confllct.At least, three paradoxlcal observatlons ean be made

in

the context ofEC-US agricultural trade conflict. The

first

deals wlth the apparent contrastbetween the tensions and the threats of generallzed trade war often pointed

out

in

the media andthe

relatively limited interactions betweenthe

tïrocountries as suggested

by

several studies. The secondis

the

surprisinggap between

the

apparent economlc gains andthe

reluctanceof

EC to undertake profound reforms. Thethird,

which may be more subtle,is

thqt the officlal positionof

the USls

probably too boldto

be really seriously feasible in regard to US domestic political conditions.r

L

a

-

The two big players can help orhurt

each other, butto

a limited extent.Many studles have explored

the

implicationsof

agresslve measurestaken

by

eitheror

both partners. Theyall

seemto

concludefor

a

llmited magnitudeof

the cross effects on aggregate policy indicators (budget, farm income, welfare), Anderson and Tyers have estimated the effect of retaliationby

the United Statesin

the formof

a subsidy onits

wheat exports. "Theadverse effects

of

sueh retallation are much lessfor

the EC thanfor

theUnited States and âre llkely

to

be insufflcientto

force EC pollcy reform.Moreover,

in

per caplta terms Canada and Australla are affected much morethan the EC". Paalberg and Sharples also note that "Iiberalization of EC and

Japanese

grain

policies would resultln

smallnet

benefitto the

United States". Ananla, Bohman and Carter have analysed the tmpact of the Export Enhancement Programme andflnd

that the EEP "has been ableto

increaseUS wheat exports. The cost

of

the addttional exports has been lower pricesin

commerclal markets and lncreased government costs.In

addltion, EEp hasnot

achievedlt

goal

of

reducing EC exports becauseof the

varlablerestitution system". These

authors

estimatethe

resulting increase invarlable subsidy cost

for

the ECto

be only 103 million dollars, whichis

asmall amount compared

to

EC outlays. Mahé and Tavéra (1982, i9S9) havealso found

that the

two countries canhurt

each other onlyto a

llmitedexten[ and

thât

domestic effectsof

policy changes are much larger than cross effects due to the absorption role played by world markets.However surprlslng,

the

flrst

paradoxis

consistentwith

the

often mentioned argumentthat

domestic forces are more important than external forcesin

shaping polieles and their reforms,It

may also be the case that,when

the

ECis

making concesslons yieldingto

US pressure,it is

inrecognitlon

for

the

wlder economic and polttical porrerof

the

US, ratherthan

in

regardto

the threat conflnedto

the agrlcultural trade arena.In

astatement before

the

Houseof

Representatlves,M.

Mendelowltz (GAO)mentioned

the

diverglng vlewson the

efficleneyof the

EEp,but

that t^..E':

abandoning

it

would glve the wrong signalto

the EC,in

the contextof

theGATT negotiatlon.

Another explanation could

be that

modelling exercisesare

very aggregated and do not speclfy bilateral trade flows which are important lnsome commodlties.

If

the economic interests vestedin

particular commoditiesare not identified, aggregate measures on budget and income do not reflect

the real weight

that

the producer groups mayput

on the government.If

this

is

true, more attentlon should then be devotedto the

natureof

thepolltlcal economy and the

role of the

various special lnterest groups that affect economic policy asa

possible explanationfor

the large differenee inthe mode and

the

intensityof

public interventionin

varlous commodltyprogrammes.

b) -

Economic efficlency hasa limited

role

in

the

deslgn and thereform of the CAP

The literature on trade liberalization

of the

CAP generally concludesthat economlc gains are significant, and many competitors of the EC on the

world markets have

strlved

to

display ample evidencethat

the

ECas

awhole should galn from liberalization

of

the

CAP. Of course these welfare galns are only potentialin

the sensethat

loosers from policlz reforms wouldhave to be compensated

to

accept the changes.These welfare measures

all

assumethat the

varlous social groupsinvolved (farmers, consumers, taxpayers) have equal political importance or

weight

in

the political economyof

government policy. Butthis is not

the casein

realityas

producers appearto

havea

larger weight than other groups.This

evidenceis

consistent with the high level of support providedto EC farmers at the expense of taxpayers and eonsumers.

Moreover,

in

orderto

identify more precisely areasfor

compromlseit

ls

necessaryto

disaggregate farmers into subgroups as policy lnstrumentsI I t. i t-t,

T-differ markedly accordlng

to

commodity programmes.If

particular commodltygroups have higher politlcal weights, changes affecting these groups

will

beharder

to

implement,or

these groups must be compensatedto

make the changes more acceptable. Aggregate efficiency measure are therefore not adequateto

understand the EC negotlating position and to investigate somelikely scenarlos

of

agreementin

the GATT negotiations. Moreover,ln

orderto find a

possible setof

politically feasible trade compromises between the US andthe

EC, knowledgeof

the

polltical weightsof the

various specialinterest groups

in the

policy processis

requiredin

order

to

devise acompensatory scheme that wlll lnduce them to accept a possible treaty.

c)

TheUS

posltionin the

GATTis a

tacticalrather than

acompromise posltion leading to a treaty.

IVhile

the

EC's proposalfor

trade

policy reform clearly shows thateconomic efficiency is not seen as a feasible goal by European governments,

the US positlon

-

total dismantllng of border and domestlc support-

wouldsuggest

that the US

governmentis led only by

welfare

effic.ienc)'conslderations.

One posslble interpretation

is that

US negotiators are convinced ofthe superior competltlvity

of

american agriculture andthat

free trade andhigher world prices would be beneficial

to the

country's trade balance. tofarmer's income, and âls,:, {.} taxpayers, There

is llttle

doubtthat

-

exceptwhen the doilar

is

greatly overvalued-

the US crop sectoris

among themost efficient

in the

world, andlt ls

widely acceptedthat

agriculturalpolicy liberalizatlon would benefit

to the

USgrain

sector. The various sklrmishes which have occured on world market outlets where the EC andthe US compete for wheat exports conflrm that view and so does the US call

for eiimination of EC protectlonlst devices

in

the food and feed graln seetor.The evidence is much less obvlous

for

soybeans and corn gluten feedexports because

the

ellminatlonof

the

support provldedto

the

livestock

T-derlved demand

for

feed, thusdriving

world prices down sharply (MahéTavéta, 1989). The US poliey makers have

not

paid great attentionto

theoffsettlng effects

of

reducingor

eliminatingsupport

to

EC livestockproducers on

the

beneflts expected froma

liberallzatlon limltedto

grain policy.Moreover, other farm subsectors

in

the US would be badlyhurt

by

a full-fledged trade llberalizatlon. The sugar industryis

the

most obviousexample,

but the dairy

sector whichis

nearly as protected asits

EC'scounterpart would also

be put

under tremendous pressure. Thereis

adebate going

on

currentlyin

the US (2) about the potentialof the

dalrysector

to

becomea

more active exporter. Evenif

world pricesfor

dairyproducts are due

to

rise sharply froma

complete liberallzation,the

high nominal rate of protection granted to the milk sectorln

the US (about 100%)suggests that the US dalry industry would suffer from free trade.

Therefore,

the US

free-trade

positionin the

GATT cannot beconvincingly explained

by pure

econemlc considerationsof

comparatlveadvantage alone. The US proposal may be easier to understand as a tactical

positlon

than âs an

indicationof the flnal

result

it

expectsfrom

theUruguay Round i.e.

of

the contentof

the treaty that they would be readyto sign.

As

in

the caseof

the EC,it is

necessaryto

takelnto

account the politicatr economy dimensions of the US negotiating positionin

orderto

sortout tactical and feasible compromlses. Moyer and Josling note that

the

USposition has been tactlcal

"ln

that the

zero optlon provided an exeellentnegotlating position,.. shiftlng

any

blamefor

thefailure

of the

UruguayRound to the EC...n (p.f92)

There âre several ways

to

interpret the previous three paradoxes bythe economlc clreumstances and the politlcs of agricultural policy making in

the Ec

and

the us. In this

paper

we do not intend to

provlde

at I t i l t L,

r

comparatlve analysis of EC and US agricultural policy decision making which

has already been done

by

several quoted authors,but our

aimls

to approximatea

workable representationof

governments behaviourin

thetrade negotlation, tnhich helps

to

understand better the actual underlying acceptable compromlses for both countries.In

boththe

EC andthe

US,the

levelof

support andthe

type ofinstruments

differ

wldely accordingto

commodity programmes,and

somesectors are clearly easier to liberallze than others. A policy goal functlon of

the government

is a

useful constructto

interpreting the politlcal economyof

economic pollcy. This construct can be usedto

aecountfor

the relativewelghts

of

commodlty groups andto

assesstheir

capacltyto

prevent somepollcy reforms while allowing some specified ehanges.

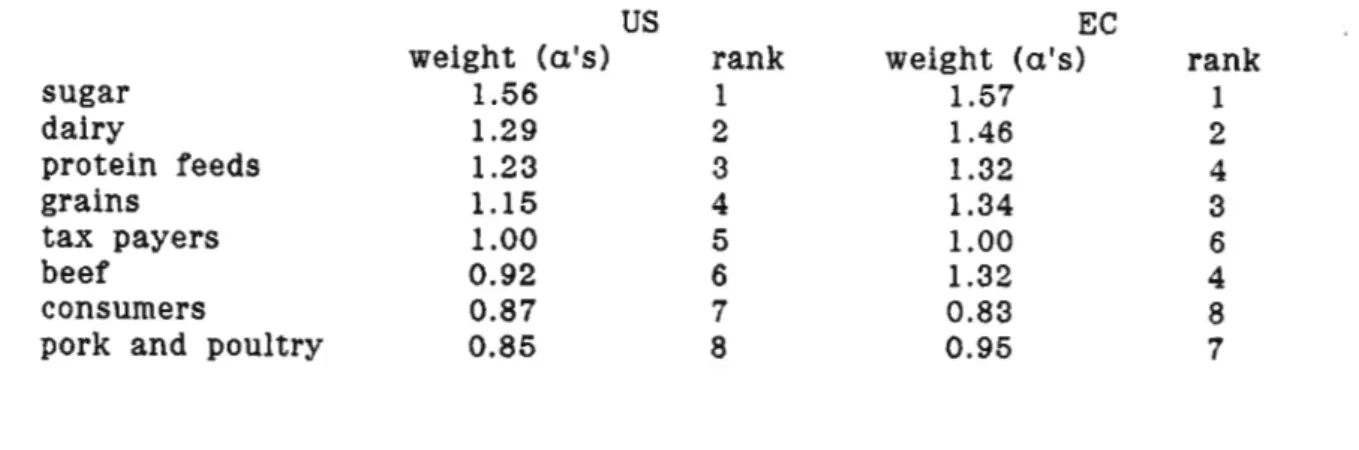

II -

Pollttcal yelghts of commodlty groupsln

the EC end the USSeveral authors have modelled

the

objective functionof

governmentas an uncontrained maximisation

of

a weighted soclal welfare functlon overprodueer

welfare,

consumerwelfare and

taxpayers (e.g. Rausser andFreebairn, Rlethmuller

and

Roe). However,tâking

the

farm seetoras

anaggregate does not reflect the heterogeneity

of

commodity programmes andtherefore the relative political strength of varlous farmer groups.

a)

-

Reveaiing the political weights of I'arious farmer groupslVe

report

here

only

the

results

of a

research devotedto

theestimation of the political weights

of

seven commodlty groupsin

the EC andthe US.

A

detailed accountof the

approachis

givenln

Roe, Johnson andMahé.

It

combinesthe

estlmation of a Policy Goal Function (PGF), a model ofEC-US'agrlcultural policy interactions and game theory.

r'' t'-! t I t-I i L,

t,

It

âssumesthat

in

the

reference perlod,the

US optimizedtheir

behaviour, 1.e.the

US government hasand

the

Ec

havet

t.,

taking

the

behaviourof

the EC as glven, and conversely. Thusthe

baseyear

is

consldered as a Nash equilibriumof the

EC-US agricultural trade pollcy game.Farmer groups

are

deflnedas

commodlty groupsfor

two

reasons.Flrst,

it is

easierto

model income effectsof

policies on varlous commodltyproducers than on various types of farmers. The latter optlon rvould requlre

a

model disaggregated accordingto

typesof

farms. Whilethis

approachwould be useful from a political organizatlon viewpoint, sueh a model

is

not available. Second, commodity-specific farmer unionsexlst

andare

quite activein

the defense of the lnterests oftheir

members.It

ls

expected that a large partof

the political pressureworks

throughtheir

channels, evenif'

general purpose farmer unlonsdo play

a role ln the

protectionof

theinterests

of

the sector as a whole andin

the alleviationof

the conflicts of interest between farmer groups.There

are

elght soeial groups lnvolvedin the

PGF, The commoditybreak down

is

the following:

gralns, protein anlmal feed, beef, dalry, porkand poultry, and sugar. consumers

are

takenas a

single group whichmeans

that they

are

assumedto be

indifferent betweena

welfare gainresulting from a price cut on sugar

or

on beeffor

example. Taxpayers arealso treated as

a

sepârate group. Of course, therels

some simplification asthese groups do

not

makea

partitionof

the society and some indivlduals belongto

several groups in the same tlme. They are not evenly affected byfarm policy programmes however, and this representation

is

expectedto

bemeaningful.

The

first

apparent reasonfor

expecting different political weights isthe

reiatlvelevel

of

nominal protection grantedto

various commodltygroups. Table

1

exhibits the NRP's (nomlnal ratesof

protection)at

the producers'level

in the Ec

and

the us (g) ln

1996. Thereare

some3 - Àctual protection rates used in the calibration of the political relghts {rith the help of the iliss nodel, l{ahé, Tavêra, Trochet} are shotn ratber lhan the P$E's calculated by 0BCD. But they have a sinilar

similarlties

ln

the patternsof

protectlon grantedto

various commodities inboth countrles. But the general level

of

supportis

smallerin

the US thanin the EC and

it

is partlcularlyso

for ollseeds products, beef and pork andpoultry. The other main difference

ls

dueto

the

US deflciency paymentsystem on gralns which puts

the

burdenof

support on the taxpayer andnot on the consumer as

in

the EC.r !--( l-I 1,, i t

Table 1. Nominal rates of protectlon {l), 1986

EC

producer

consumer USproducer

consumer grains protein feeds beefpork and poultry dairy sugar 78 95 76 20 94 80 0 76 20 80 L70 56 10 6 0 80 120 10 0 5 0 69 r20 170

t,

tl) delined u 100 r (poduæt piæ - border pdæl devided by boder priæ.

The political value function is deflned as a

weighted sumof the

galnsthat the

various social groups derivefrom

the

policieslmplemented. The PGF

is

Just

a

way

to

order dlfferent

statesof

theeconomy.

It

is therefore defined up to a monotonic transformation. Hence theweights must be normalized

to

be easily lnterpreted, andin

the

present cese, taxpayers are glven a weight equalto

one.7

(l) V=XorTr*Tt

:-l

I-l

where the o'g are the polltical weights and the T's the transfers benefiting

to the groups.

Tt

is the transferto

taxpayersor

budget receipts. The listof

producer groups (i=1to

6)

ls

givenin

table 1 antl i=? represents theconsumer group. Slnce we assume that the base year 1986 was

an

optimal situatlonfor

both the EC and the US, the V function hasat

a maximum lnthis year

;

therefore the pollcy instruments were chosen so asto

maximiseV,

andthey

verlfy the first

order conditionsfor

the

PGFto

reach amaximum i.e.,

t-a

r-ra

f

Q) ôv/ôgr=0

;J=1,...,7

where gJ

is

theitl

policy instrument. Making useof

(1)

weget a

set of seven equationsln

seven unknowns, the o's.7 (3) X or ôTr / ôgl + ôTt / ôg1 = g !-r I-l l-l; J - lr ...r t

By alterlng the policy instruments

of

each commodity programme andof the consumer group, a set of estimates for ôTr/ôgr were obtained and (3)

was solved

for

the

o's. Table2

shows the valuesof

the weights derivedfrom

this

process. An internatlonal trade modelis

neededto

generate theôTr

/ 6gt

as the EC and the US are large enoughto

affect world priceswhen

thelr

pollclesare

changed. The lmpacton

the

budget (ôTt/

ôer)should therefore account

for this

termsof

trade effects;

Moreover someprogrammes, as

for

oilseedsln

the EC andfor

many commoditiesln

the US,do

not

lsolate domestlc prices from world prlces, sothat the

welfare of consumers andof

some producers (e.g. llvestock) depend on world prlcechanges.

Table 2. Polltlcal weights of various commodlty groups and

of

consumers inthe EC and the US

r-I r t t t I t I l r I t US rank 's) eh wei EC weight (o's) t,57 1.46 1.32 1.34 1.00 1.32 0.83 0.95

t(o

56 k ran I I 4 3 6 4 8 7 sugar dairy protein feeds grains tâx payers beef consumerspork and poultry

1 D 3 4 5 6 7

I

I 1 1 I I 0 0 90 .23 .15 .00 .92 .87 0.85 I I \-f i[- The relative size of the polittcal weights does not depend only on the

level of support

but

also on the burden that the particular produeer group is able to put on other groups.To

see why, considerthe

simple case where

r-

t-there are no cross effects between commodity groups (ô Tr

/

ô

g

= 0for

i+

i, iJ = I

to 6). The equatlon for the jtb weight amountsto

:or ôTr / ôgl * oz ôTz / ô$ + ôTt / ôg1 = g

It

turns out that fora

given effect on the welfareof

producerj

(ôTl/

ôgl), the

weightot

wlll

be

larger, the larger :lre effects on consumersand taxpayers in absolute value, as long as they are negative which

is

truein most cases,

In

other words,a

commodlty groupwill

have higher welghtsif

the benefitit

gets costs more on consumers and taxpayers. This approachcould be extended to other commodlty groups.

The weights in table 2 therefore refleet a richer lnformation than the nomlnal rates

of

protection as they depend on the type of instrument usedto

provide the lncome transferto a

partlcular commodity group. Take thedairy producers

in

the EC a$ an example. Not only do they beneflt from ahigh

supportbut

becauseof the net

exporting positionthe

producersurplus

is

larger than consumer surplus and tax payers must finance theexport subsidles, hence a high weight to dairy producers

in

the EC.The

flrst

noticeable observation drawnfrom

the

analysisis

thesmaller weight

of

consumersin

the ECin

comparisonto

the US consumers.This

is

conslstentwith

the different typesof

policy lnstruments used inboth countries

for

mâny products and particularlyfor

grains and wtth the smaller taxatlonof

consumers of anlmal productsin

the US. The ranking of commodity groupsis

actuallynot

so differentln

the

two countrles, wlth sugar and dairyat

the top and pork and poultry producersat

or near the bottom. Graln producers have a smaller relative weightin

the

US than lnthe EC and

it

is even more the case for beef producers.b)

-

A brief interpretation of the relative weightst t: I t I L,

It

structureis

outof the

scopeof this

paperto try to fully

explain theof

the political welghtsof

the

various producer groups.A

fewL3

L

I

t

remarks drawn from public choice theory are appropriate horpever. Public choice explanations stress

the

importaneeof

the costof

organlzation and,therefore,

of

the numberof

agents andthe

concentrationin

the industry.The relatlvely low welght

to

consumers relativeto

taxpayersis

conslstentwith this explanation. So ls the case

of

sugar producersln

both countries,as they are

fairly

few and asthe

industryls

highly concentrated. Theirability

to

keepthe

hieh levelof

supportis

probably also dueto

the

lowbudget cost of the sugar programmes

in

the EC and the US, which puts the burden mainly on the less well-organized consumers.Budget cost

or

tax pâyers expenses are more visible than consumersurplus loss. Consumers must invest

in

ahigh

costof

informationif

they want to show theirloss

and make their caseln

the democratic process. Thebudget cost

ls

'obvlous every year and attracts more scrutiny from thegovernment and from the public opinion. Therefore costly programmes are

expected

to

be less sustainable. Thefairly

large political welghtto

grain producers as reflectedln

1986in

both the EC and the USis

partly due tohlstorical

rigidity of

programmes which werenot

costly whenthey

werelnitlated. The EC has only become

self

sufficientin

grainsin the

early eighties and the US Target Price setin

1980 was not sofar

away from theworld

price

which

has

droppedin dollar in the early

eighties. Thestabilisers in the EC and the reduction

in

the US Target Price and the LoanRate introduced

since by the US farm bill tend to

confirm

thlslnterpretation. To

a

large ext,ent,the

fairly

high weight givento

oilseedproducers

in

the .EC

can

be

accountedfor by a

similar

historicaldevelopment,

to

whichthe

low self-sufficiency of the ECin

protein feed hascontributed.

At first

sight,the

rankingof

dairy

producersis not

so easy toexplain

by

the concentratlon and costof

organization argument. There aremany producers and

still

they manage to develop a large political ponrer. Inthe US however, the hlstory

of

protection hasits

rootsin

the formation ofmarket orders

and

agreementsfor dalry

producers.This

was partly stimulatedby fairly large

and

well

organizeddalry

cooperatlves. Thecooperatlves provided

an

organizational structurethat

in fact

served to Iower the costof

coalltion formatlon, the costof

forming groupsof

similar interestsat

the local level and then being ableto

launch effective lobbylng

r-the cooperatlve structure also provlded

a

mechanism to solve the free rider problem so thatall

dairy farmers would be taxedto

support the costof

alobbying effort. To

a

large extentthis

argumentis

also valldfor

the

ECwhere cooperatives have been lmportant actors

in

the

dairy industry. Therelatively low income

of

dairy producers generatedby

free market forceshas also contributed

to

makethe

support programmes more aeceptable tothe public oplnlon, at .ieast

for

the past. Agaln the recently higher cost ofthe programme have led

to

supply eontrol measures!with

theall

buy-outscheme

in

the US and production quotasin

the EC. This shift of the burdenon

the

consumeronly

andthe

vested interestin

productlonrights

arelikely

to

keep the rankof

dairy producers hiehin

the scalefor

the nearfuture. Beef producers

ln

the EC arestill

for mostof

them dairy producersdue

to

the complementarity betneen beef and mllkin

the

EC, hence theirweight are similar to dairy producers,

The sltuatlons of pork and poultry producers

in

the EC and of pork,poultry and beef producers

in the

USare

rather similar. Although theconcentration

in

the industryis

high, they have not been ableto

attractmuch support. The high elastlcity argument proposed

by

Gardnerfor

animalproducts

in

the US seemsto

be relevant. These producers are often well-offin Europe

in

spite of unstable prices, they are not viewed as typlcal familyfarm operators but rather as commercial farmers, and policy makers fear a

rapid

accumulationof

surplusesif

higher support were grantedto

the industry.Even

if

afully

adequate politieal economy explanatlonof

the relative welghtsis

notyet

available, they do not seemat

odds with the intuition of policy analysis.It is

now north investigating the llght they can provide onthe GATT negotiatlons.

III. Feaslble compromlses between the EC and the US

Various stages

of

farm pollcy reforms were simulatedfor

the EC andthe US, both

in

unilateral and bilateral ways. These actlons leadto

impactst

:

r-on pollcy lndlcators which can be presented in the pay-off matrlx of a game

as ln table 3. In the GATT context the political pay-offs are used preferably

to pay-offs based on classlcal welfare

gains

On the baslsof

the matrix ofpolitlcal gains and losses

ln

the EC an the US, Feasible compromlsesin

the negotiations are shown to exlst.a

-

partial liberallzation and decoupled compensatory paymentsFour

actionsâre

investigatedwith

increaslng degreeof

tradeliberalizatlon

for both

countries. More preciselythe

posslble actions simulated for the US are :-

(sq) The statu quoof

1986 ;-

(bpes) Ban on producer and export subsidies;

free

tradein

atlcommodltles except beef, sugar, and

dalry,

self-sufficiencyln dairy

is followed while sugar prlces and beef quotas remaln at the status quo ;- (pft)

Partial free trade;

free tradeln

grains, animal feeds, beef,and pork and poultry

;

dairy and sugar policles remaln at the statu quo ;-

(ft)

Free trade;

free tradeln

all

commodities ;and for the EC they are :

-

(sq) The status quoof

1986 ; r-

(bpes) Ban on export restitutlons;

ad valorem tarlffs attaln self-sufficiencyin

grains, beef, pork and poultry, dairy,price differentials,

in

percent, between producers and eonsumersthe status quo

;

the farm price of oilseeds is unchanged ;are used to and sugar ; remain at 1' I 1 iL L.

(pft)

Partialfree trade

;

Ad

valoremtarlffs of

ZO percent areimposed on grain and beef,

the

oil

seed cake supportis

redueedto

ZOpercent more than world prlce,

pork

andpoultry

priceis

setto

worldprlces, dairy and sugar prices remain at the status quo ;

r-The economlc results are summarlzed

in

table3 ;

the US chooses the row, the EC chooses thecolumn.

Before diseussing the game matrixof

thewelfare galns,

the key

economlc outcomesof the

simutationsare

brieflysummarized.

For

comparable experlments,the

results

obtainedfrom

the model are simllarto

those obtained from (CEC).In

general, liberalizatloncauses large lncreases

in

the world prlces of grains, beef, sugar, and dairy,decreases

In

the prices ofoil

seed cakes and Feed Grain Subsiltutes (FGS),and smaller changes

in

the prlceof

pork and poultry. Three factors drlve these results:

crop production shiftin

the US from grains to oilseeds, feedlnput substitution

ln

the EC from oil seed cakes and feed grain subsiltutes(rGs)

to

gralns, and lower feed input demandof

beef, dairy, and pork andpoultry produeers in the EC due

to

the contraction of the animal sector.The

strict

economlc results would predict that both countries move tofree trade

if

classical welfare efficiencye)

werethe

single pollcy goalpursued by the EC and the US governments. Table 3 shows that

(ft,

ft)

is

aNash equillbrium

of

this game;

free trade isa

dominant strategy whateverthe

other player does.If this

game were reallstlc one would expect the posltions expressedin

the

GATTto

befar

bolder than what we observe.Since

they are not,

governments most certainly havea

more eomplexobJective function and social groups weights

in

the PGF must differ as wasshown

in

table 2.

r-t'

1.,

r-Table 3

:

tflelfare galns from poliey reforms (a)(billion ECU) EC US sq bpes

pft

fr

sq 0 6.4 3.0 8.5 -. 0 0.3 0.4 0.3 bpes 0.4 6.6 3.3 8.9 2.5 2.3 2.8 2.3 rpft

0.L 6.3 3.7 8.9 1.5-0.8

1_.I

2.0fr

0.9 6.8 4.7 8.8 3.0 2.6 3.3 2,7 r I I i t{a} The $outh-East nunber ig the U$ relfare gain ald the llortl-fesl is the EC's gain.

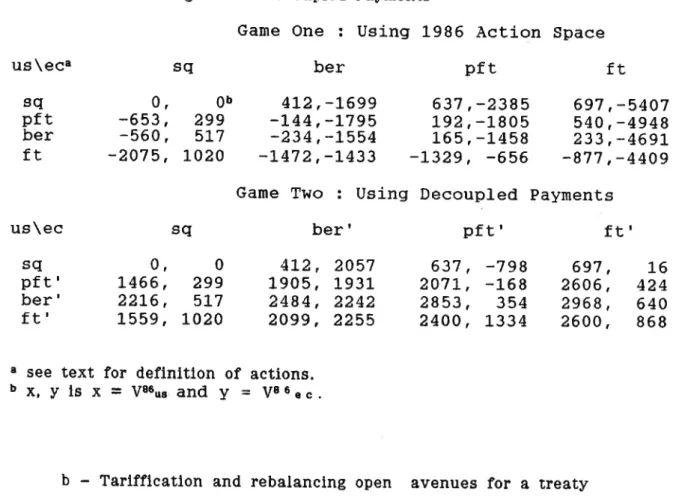

The games presented

in

table 4 are more relevantfor

understandingthe GATT round. The pay-offs

in

table4

(game one) are now the values ofthe PGF assoclated wlth each combinatlon

of

actions takenby

theEC

andthe

US. Liberalizationof

farm policies doesnot

appearlikely

at all if

countries limit their margln of manoeuvre to the current policy instruments.

Although each country would

like

the

other playerto

move toward freetrade,

it

bears a political lossif it

makes the move itself. Domestic policies again mâtter more than policiesof

other countries. Within the setof

policy instruments usedin

the past, the prospect of an agreementin

the GATT is bleak,if

the PGF calibrated on the base year 1986stlll

reflects the political weights of social groups relevant for the 1990 situation.Feasible compromises require the use

of

new policy lnstruments andtable 4 (game two) lllustrates the outcomes of

a

liberalization combined with compensatory decoupled payments. Game twois

derived from game one inthe following way. Budget savings resulting from pollcy changes are used to compensate producer groups,

the

groupswith

hlghest weights beingrr r I r-{

r

T Ir

t- r-l tr

i F l 18compensated

flrst.

Therels

not enough savingsto

compensateall

producergroups, because

of

offlciency loss andof

the

large share of.the

current polieles burden borne by consumers.Game two shows

that

feaslble compromises between the EC and the USexlst

if

decoupled payments are used. The best prefered action corespond to bpesl.e

a ban on production and export subsidiesln

the US on grains anddairy and a ban on export subsidles wlth a return to self-sufflclency in the EC

for

gralns, beef,pork

andpoultry, dalry

and sugar (ollseeds beingunaffected).

As

the

savingsare

not enough

to firlly

compensate producers,decoupled payments make

freer

trade polltlcally acceptable,but

not

full-fledged

free

trade.It

ls stlll

polltically necessaryto

keep someof

the burden put on consumers, because of their low weights. Freer trade results,free trade does not.

I t

L

LL

L

L

L

L

I l t d

t-Table 4 : Policy-Goal Function Values for Alternative U.S. and E.C. Trade

Liberalizatlon Strategles and Decoupled payments

|.

sq

Game One

:

Using L986Action

Spaceber

pft

us\ec. sqpft

berfr

us\ec sqpft'

ber'

ft'

0, -653, -560, -2075, 4I2, -1_699 -L44 , -L7 95 -234, -1554 -L472, -1433412,

2057L905,

19312484,

22422099,

2255 637,-2395 192, -1g05 L65, -1459 -1"329, -656fr

697,-5407 540, -4948 233,-469! -877,-4409 0b 299 5L7 1020 sqGame Two

:

Using Decoupled paymentsber'

pft'

ft,

0, 'J,466, 2216, L559, 0 2995tt

1020 637 , 207l., 2853, 2400, -798 -1_68 354 L334 697 , 2606, 2968, 2600, 16 424 640 868 I ta see text for definitlon of actions. b x, Y ls x = V8ôug âJId Y = V86ec.

b

-

Tarifficatlon and rebalancing open avenues for a treatyA

new setof

pollcy lnstruments was also introduced, basedon

thenegotiationg posltion

of

the EC. Rebalancing implles tradingtariffs

on feedimports

for

a decreasein

the support provided to grain and oilseedsin

theEC.

This scenario

ls flrst

exploredon the

basisof

the

oil

seed sectoronly. Before implementing increasing levels

of

tariff

on

oilseeds and cakesthe EC gets

rid

of the crushlng subsidy and the supportis

only providedby the tariff. Tabte 5 illustrates the results of this scenarlo on both the Ec

and

the Us

PGF'g. ïrhenthe Ec

abolishesthe

produeer subsidy, worldprlces

for

oilseeds and cakes increase and US soybean producers benefit from this termsof

trade effect, hencethe

us

grainln

pGF, lvhenthe

Ecimposes increasing levels

of

tariffs the

US PGF decreases contlnuously asthe gains from the lower EC producer prlce are increasingly offset

by

the losses dueto

the

ECtariff. A

tarlfficatlonat

40%or

less leavesthe

USbetter

off

thanln

the status quo. Tarifficatlon hasa

different pattern ofeffect on the EC's PGF. When the crushing subsidy

ls

abandonned, the ECsuffers

a

polltical loss, because the lncome lossof oil

seed producers is Iarger than tax payers galn and because the welght of the former group ishigher. When increasing levels

of tariffs are

implementedthe

EC's PGFincreases and reaches

a

maximumat a

40per

centtariff.

Higher levels oftariff

impose a larger loss on livestock producers and the PGF decreases.From table 5, a tarlfflcation

of

upto

40 per cent makes both the ECand the US better off

in

termsof

the PGF. Tarifflcation, and rebalancing doopen areas

for

feaslble compromlses, But the changein

the PGF are fairlysmall as compared

to

game two, so that the possibilityof

both countrles togain from tariffication and rebalancing

is

likely

to

be sensitive to the baseyear situation.

Tableau 5. Impact of tarlfication and rebalanclng

ln

oilseeds on the PGF'sThe domain of a feaslble treaty was further explored by extending the

rebalancing concepts

to

grains andto

feedgraln

substitutes.A

feasibletreaty zone was uncovered where both the EC and the US would be better

f l-I 1 I t EC PGF' US PGF

-200 60

220 296

310 280 -60 190 - 100170

-80-45

-90305

210 140 70

3 EC Tariff on oilseedsi

r-i

off than in the status quo.

It is

illustrated on figure 1. The ECtariff

rateson imported feed are indicated on the y-axis and

the

decreasein

nominalrate of protection on grains and oilseeds on the x-axis.

Figure 1. A EGUS Treaty zone based on Tariffication and Rebalancing

I

r-I i

EG anlmalffi tartfr rab (%)

3tt $ â ât t5 10 5 t l r t ; I -10

(d prcarcc ntd ûfY for ol3.oô

From the analysis

of

a rebalancing limitedto

oilseeds, we expect that the PGFof the

EC increasesin

the

north-west direction when support isless reduced on grains and oilseeds and when

tariffs

on imported feedsinereases in the same time. Clearly, the US's PGF decreases

in

that direction and therefore improves when we move toward the south-east. Theleft

handlimit of the treaty zone corresponds

to

combinationsof

tariffs

and support0

€

-15

Cut ln nomlnal rate of protectlon'(%) of EC graln and oll seed

r I I t r I I I I I t \, t I t.-I I

t.

I I i i i-" ZONE TREATY

t'-E

cuts which keep the EC indifferent

to

the status quo. The rlght-hand limitmeans

the

samethlng for the

US. Comblnationswithln

the

treaty

zoneimproves

the polltlcal galns and

therefore

correspondto

feasible compromises between the EC and the US, witha tarifi

range from zero up to 80 per cent anda

cutin

nominal protectionof up

to l5

per cent. Hereagain the changes ln political galns are falrly small as

ln

table 5.a a a t-I I t-f I I I I

This investlgatlon has shown

that

the polltical economy dimension is necessaryto

providea

rationalefor

the negotiating positionsin

the GATTand

to

solve the paradoxes mentionnedin

theflrst

section. The ECis

likely to move further toward liberalization thanits

early declaration in the GATTsuggested,

but

new policy instruments are necessary. The US is unlikely tofetch complete trade liberallzation

in

the GATT. Freer tradeis

likely, free trade is not.There

are

obvlous limitsto the

present investigation. Two may bementionned. The reference year used, namely 1986,

is

somewhat exceptionnal and the weights are not necessarily relevant for 1990. A sensitivity test wasdone however, and

it

showed that they are fairly robust. But the situationof

the markets and budget outlays has evolved slnce 1986 andthe

treatyzone relevant today may look different. Using

the

1986 weights tothe

1988base year conflrms

thls

changein

the economic outlook and shows that the domainof

feasible compromises between the EC and the US has shrunk, so that a treaty seems less llkely now..

i'-

t-Another caveat

is ln

order.

It is not

certalnthat

reciplents of decoupled payments value one ECU from the budget as one ECU from marketprice support, since decoupled transfers

will

be

harderto

sustainln

the Iong run,To sum up, the outcome of the negotiatlon

is

uncertain as both the ECand the US seem to be close

to

be indifferent to the status quoin

terms ofpolitical pay-offs. Feasible compromise based

on

compensation and/or onrebalanclng exists however. Further exploratlon

with

an game extended tothe other OECD countries does improve the feasibility

of

a treaty, so thatsome degree of liberallzation

ln

the GATT is altogether likely.Sunmery

-

ConeluslonsThe international game played in the EC-US agrlcultural trade confllct cannot be explained only on

the

basisof

classical welfare analysis which would predict free trade dueto

efficiency gains. A political value functionis more relevant to aceount for government behaviour. The various producer

groups appear to have quite different political weights,

in

the EC as well asin

the US, and the rankingof

the various social groups involveddiffer

in both countries.'

The pay-off matrixof

liberalization strategies expressedin

terms ofthe

PGF showsthat both

countrles wouldprefer

status quoto

policyreforms.

But

when decoupled paymentsto

compensate the most powerfulproducers are made, some degree

of

reformis

made politically feasible.r

I I ir

t

r

! { r: Tr

I Ir

t-r

t 24There

ls

also room fora

treaty between the EC and the US, based ontarlfficatlon and rebalanclng. However

the

polltical galnsare

small andrecent changes

ln the

environment have reducedthe

domainof

feasibleagreements.

Therefore

both the

ECand

the

US

appearto get

closeto

beindifferent

to a

treaty

based on rebalanclng. Compensatlon and decoupledpayments seem to be the only avenue for signiflcant policy reforms to occur

ln

the GATT. I { i { t {_ !. Il

I {t

: (" t

t-r

REFERENCES

ANANIA G., BOHMAN M. and C. CARTER (1990)

The US-RC Agricultural trade war

:

an analyslsof

the effectsof the

EEP on the world wheat market;

paper presented atthe VIth EAAE congress, The Hague ANDERSON K. and TYERS R. (19S3)

European Communlty's

grain and

meat policies

and

USretaliation

:

effects on international prices, trade and welfare. Australlan Agricultural Unlverslty Q7 p.)CATHIE J. (I985)

"US and EED agricultural trade policies". A long run vlew of

the present confllct. Food Policy

-

FebruaryCURRY C.E, (1985)

"Confrontation or Negotlation" (United States Pollcy and

European Agriculture). Associated Faculty Press

c.E.c. (1988)

Disharmonies

ln

EC and US Agricultural Policy measures :Report to the EC Commisslon Offtce of publicatlons.

GAO (1e89)

Status report on GAO's review of the Export Enhancement

Program-US General Accounting Office

GAO/T-NS1AD-89-45

GARDNER B. (I987)

Causes of US farm commodity programs Journal of Political

Eeonomy, 95 (21)

:

290-310HATHAWAY, D.E. (1984)

A U,S. View of the Common Agricultural Policy

Paper presented

at

the International Financial Conference,Vienna, Aprll

MAHE L.P. and C, TAVERA (1988)

Bilateral llarmonizatlon of E.C. and U.S. Agricultural Policies

European Revlew of Agricultural Eeonomics, 15

:

327-348MAHE L.P., C. TAVERA and T. TROCHET (1987)

Simuiations de guerre commerciale agricole entre les USA et la

CEE

:

eonfllts et compromis. In J. Bourrinet ed. Les relatlonsCE Etats-Unis, CEDECE, Economica Paris

MOYER H,1[. and T.E. JOSLINC (1990)

Agricultural Policy Reform. Pollcies and proeess in the EC and USA Harvester wheatsheaf. London

PAALBERG P.L. and J.A. SHARPLES

"Japanese and European Community Agrlcultural Trade Policies

: Some US strategles"

L-r

ir

II

t-r

I lI

r

I 26 PETIT M. (1985)Determlnants of Agricultural Policles

ln

the Unlted States andthe European Communlty

Research Report 51. IFPRI

RAUSSER G.C. and J. FREEBAIRN (1974)

Estlmatlon of pollcy Preference Functions

:

an appllcatlon toUS Beef Import Quotas

Revlew of Economlcs and statistlcs, 56

:

497-49RIETHMULLER P. and T. ROE (1986)

Government Interventlon

ln

Commodlty Markets :Japanese Rice and Wheat Pol.icy

Journal of Pollcy Modelllng, 8 (1986)

:

gZ7-949The Case of

ROE T.L., JoHNsoN M. and L.P. MAHE (1990)

Politleally acceptable trade compromises between the EC and

the US

:

a game theory approach.University of Mlnnesota Dept. of Agricultural and Applted

Economlcs

TRACY M. (1e82)

Agrlculture in lVestern Europe, Challenge and Response, 1880-1980, 2nd ed. London

:

Granadat,

L

t

L

!L

t

L

ii\ ijl

:il-

,} 1n

1lir.

iin

ll

l Ilrr

iliij

i Il[-;l

DOCUIIENTS

I'E

TR,ÀVÀIIJ Octobre 199090-01 I'I]IPACT DE IrA PROPOSITION AITIERICAINE ÀU GATT SUR lES AcRICUTTURES DE

LÀ CEE ET DES USA. Hervé Guyomard, Louis P. llahé

et

ChristopheTavéra (1990)

90-02 ÀGRICUITTURE IN THE GATT

:

A QUANTITÂTM ASSESSIIENT 0F THE US t-989PROPOSAIT. Hervé Guyomard, Louis

p.

Mahéet

Christophe Tavéra(1990)

90-03 EC-US AGRICUITTURAIJ TRADE REIATIONS

:

DO POLITICAIT CO]|PROUISES EXIST ?Louis P. ltahé and Terry Lr. Roe fi.990)