Illustrating a Woman’s Text in a Man’s World

The Art of Visualizing Madame Riccoboni

Marijn S. Kaplan

Abstract

In 1764 Marie Jeanne Riccoboni (1713-1792) became purportedly the first French woman to publish an illustrated first-edition novel, Histoire de Miss Jenny; the 1786 definitive collection of her oeuvre in 8 volumes bears no less than 24 illustrations. This essay argues that these illustrations produced by male visual artists visualize the role gender played in eighteenth-century-French narrative illustrations in that they show to what extent a woman’s text illustrated in a man’s world resembles Riccoboni’s real phallocentric world much more closely than her fictional protofeminist world.

Résumé

En 1764 Marie Jeanne Riccoboni (1713-1792) fut sans doute la première femme française à publier un roman en première édition illustrée. Dans l’édition définitive de cette œuvre en huit volumes (1786) on ne trouve pas moins de 24 illustrations. Dans cet article, on démontre que ces images produites par des artistes masculins rendent visible le rôle du genre dans les illustrations françaises de l’époque. Ces images montrent en effet un univers qui relève beaucoup plus du monde phallocentrique dans lequel évoluait Mme Riccobini que de l’univers protoféministe qui émerge dans ses récits.

Keywords

Riccoboni, Marie Jeanne; eighteenth-century France; women writers; visual arts narrative illustrations;

Histoire de Miss Jenny; gender; Gravelot (Hubert François Bourguignon d’Anville)

In France, decorative images were produced alongside texts at least as far back as the early fifteenth century when John, Duke of Berry (1340-1416) commissioned the Très Riches Heures, a richly illuminated book of hours. The invention of the printing press later that century facilitated the larger-scale reproduction of books and texts as well as images that had been created through engraving. Nevertheless, it took many more years before narrative illustrations routinely accompanied printed texts. Although La Princesse de

Clèvesgenerally considered the first French novelwas published in 1678, French novels were still

The year 1761 however marked a milestone in the transition from decorative to narrative illustrations, as Jean-Jacques Rousseau published Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, illustrated by the celebrated Hubert François Bourguignon d’Anville called Gravelot (1699-1773) who has been described as “perhaps … the first to show what might be done in the way of illustrating the subjects treated in [the novel’s] pages” (Dilke 111).

The publication of Julie brought about many changes. It caused both reader and collector demand for illustrated novels to soar in France and French novels to become more commonly illustrated from their first edition onward. And although publishers and printers had controlled the illustration process during the first half of the eighteenth century, novelists now increasingly adopted this role. They naturally selected illustrators who would follow their instructions (Cronk 403) and thus Rousseau, an apprentice engraver himself, had become actively engaged with Gravelot in the illustrations for Julie. He had told Gravelot what scenes to illustrate and ordered him to make many changes as detailed even as the size of women’s eyes and breasts (Cronk 404-06),1 wanting the illustrations to correlate closely with his novel. This, however, deviated from the norm for as Christophe Martin has demonstrated, a basic dissociation exists between eighteenth-century narrative illustrations and their narratives. Due to economical, social and esthetical reasons, the former do not necessarily illustrate textual highlights but rather tend to favor attractive images that please not only readers but also collectors, with a preference for intimate spaces where reading and/or writing take place as well as for the female body. As such, reiteration often supersedes originality, with illustrations serving three main purposes: decorating a page, interpreting a text and rousing the imagination.2

Merely three years after Rousseau’s Julie was published, Marie Jeanne Riccoboni (1713-1792) became purportedly the first woman to publish an illustrated first-edition novel, Histoire de Miss Jenny.3 In 1786 the definitive collection of her oeuvre in eight volumes came out bearing no less than twenty-four illustrations, Oeuvres complettes [sic] (Lewine 465). The fact that the latter appeared during her lifetime in 1786 implies that her popularity had soared enough to justify a sizable investment in visual arts on her publisher’s part.4 Riccoboni had started her career as an actress but then became an author, one of the few eighteenth-century French women to be able to live of her pen. She produced numerous bestselling novels, short stories, essays and translations, and corresponded with such male Enlightenment luminaries as David Hume, David Garrick, Denis Diderot and Pierre Choderlos de Laclos. Although her oeuvre remained relatively unknown during the nineteenth and most of the twentieth centuries, gender became an axis of exploration during the 1970s. Since then, feminist analyses of her texts abound, such as those by Joan Stewart who includes Riccoboni prominently in the “covert female rebellion” of late eighteenth-century French women writing against their oppression by patriarchy (1).5 By analyzing 1.All translations are mine unless otherwise indicated. See also the articles by Claude Labrosse.

2. See Martin’s Introduction, pp. 1-40.

3. See Cronk’s list, p. 408. At a time when copyright did not exist yet, pirated editions were rampant. Thus, Riccoboni may never have seen the earlier illustrated edition of one of her other novels published in Germany and uncovered recently by Nathalie Ferrand, a 1762 edition of Lettres de Juliette Catesby (248).

4. Volland had announced beforehand in the Mercure de France that the collection would also be sold through subscription: subscribers paid a lower price and only paid if they liked the volumes as they received them. See “Annonces et notices.” Subscribers paid 3 livres 12 sous per volume as opposed to 4 livres 10 sous for others. 5. Other feminist interpretations include Bostic’s, Lanser’s, and Sol’s.

the role gender plays in the context of the visual arts, this essay examines the relationship between Riccoboni’s novels and her narrative illustrations in an effort to determine whether the latter support or detract from feminist textual interpretations.

Eighteenth-century France was a man’s world and relatively few female-authored novels existed, let alone novels bearing illustrations.6 Although numerous women wrote at this time and contributed to the dissemination of Enlightenment ideas, most people still harbored prejudice against women writers for abandoning the private sphere and entering the public sphere in order to compete with men in the intellectual domain.7 Geraldine Sheridan has shown recently that “one of the most skilled craft occupations in which women excelled was the art of engraving … a rare example of an area in which women could develop a respected career” (225), yet male engravers still greatly outnumbered female ones.8 Therefore, the parties involved in the publication of an illustrated novel remained predominantly male—from the illustrators or draftsmen9 to the engravers and the publishers who took a financial risk because of the costs involved.10 Riccoboni quarreled regularly with all-male pirates, publishers, and translators in order to publish and protect her work, as I have demonstrated elsewhere,11 and the same applied to her interactions with visual artists. A couple of weeks before Miss Jenny appeared she told David Hume—who was acting as intermediary for the novel’s translation into English—that she could send him the four drawings Gravelot had done for the French version for the translation as well (Nicholls 40), revealing an apparently positive relationship with Gravelot. With Noël Lemire (1724-1800), however, the engraver of two of Gravelot’s illustrations for Miss Jenny (and some for Julie), she had a contentious relationship. In the same letter to Hume, she says she will not send him the engraved plates because they will be bad and she calls Lemire “impertinent” because he is making her wait and dares to ask as much money for retouching the plates as for engraving them in the first place (Nicholls 40).12

Thirteen illustrations grace Riccoboni’s novels overall between the two editions; none have received much scholarly attention.13 Miss Jenny contains four, a frontispiece for each volume, all drawn by Gravelot; Lemire and Benoît Louis Prévost (1735-1804) each engraved two. Three of Gravelot’s 1764 drawings later reappeared in Riccoboni’s 1786 collection; the fourth was left out likely because it depicts three women talking, just like another 1786 image. In addition, the 1786 collection comprises 16 new illustrations by Brion de la Tour (?1756-1823), Gravelot having died in 1773. Five new illustrations are unsigned14 and the engraver is unknown. The facts that the 1786 collection contains drawings by two 6. Both Ferrand and Martin demonstrate this through the paucity of female-authored novels included in their studies.

7. For a detailed study, see the book by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith and Dena Goodman. 8. See Index in Roger Portalis Les graveurs…., vol. 3, p. 763-79.

9. See Index in Portalis Les dessinateurs…., p. 787-88. 10. For more background, see Philip Stewart ix, Martin 4-8.

11. See my forthcoming article in the French Review, “Publication, Authorship and Ownership in Marie Jeanne Riccoboni (1713-1792)”, vol. 88.1, October 2014.

12. In the end, the English translation did not contain any illustrations.

13. Ann Lewis’s contribution to the 2007 Riccoboni conference volume Mme Riccoboni: Romancière, Épistolière, Traductrice, which also reproduces all 1786 illustrations (p. 327-50), constitutes a notable exception. More recently, Ferrand has examined the role of the book in eighteenth-century illustrations, including Riccoboni’s. 14. It has been suggested that Nicolas Ransonnette (1745-1810) made them (Supplément au Journal de Paris).

illustrators in addition to Gravelot and that one text—Amélie, an adaptation of Fielding’s Amelia—has two illustrations by different illustrators, indicates the fragmented, less uniform nature of this illustration process in comparison with 1764. The twelve images that illustrate the novels are distributed over the first six volumes of Riccoboni’s 1786 Oeuvres as follows:

Volume T o t a l

number of illustrations

Novels with [number of illustrations]

1 3 Lettres de Fanni Butlerd (1757) [1] Lettres de Juliette Catesby (1759) [1]

2 3 Histoire du Marquis de Cressy (1758) [1]

3 3 Histoire de Miss Jenny (1764) [3]

4 3 Lettres de Sophie de Vallière (1772) [3]

5 5 Histoire d’Ernestine (1765) [1]

6 2 Lettres d’Adélaïde de Dammartin (1766) [1]

Lettres de Mylord Rivers (1776) [1]

As the only recurring images after a twenty-two-year gap, the Miss Jenny illustrations show noteworthy trends. Having been 1764 frontispieces, in 1786 they appear instead near the text they illustrate15 and as mirror images. They have undergone subtle changes at least partly due to changing fashions (in hair styles and bonnets, for instance) and the larger 1786 illustration size (5 by 3 inches as opposed to 5 by 2.8 inches in 1764).16 Consistency in the depiction of identifying markers, such as Jenny’s facial features, is missing both across the 1764 images and from 1764 to 1786. Also, the iterative nature of the images becomes apparent in that they resemble other illustrations by Gravelot whose talent was so respected that he was routinely given the freedom to select his own subjects (Martin 19) even though he had accepted detailed input from Rousseau for Julie. An examination of Miss Jenny’s third illustration (1764 on the left, 1786 on the right) demonstrates these points, particularly when compared with another one that Gravelot had made for Prévost’s Manon Lescaut in 1753, “Manon in Saint-Sulpice’s parlor” (interior location, characters, their clothes, positions and gestures, furniture, door…).17

15. During the symposium Worth a Thousand Words: At the Intersections of Literature and the Visual Arts, held October 24-26, 2012 at the Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, Keri Yousif observed astutely that in comparison with nineteenth-century French illustrations, the eighteenth-century ones do not have a title and appear on a separate page with a blank page preceding rather than integrated into the text.

16. I would like to thank the following librarians for this information: Catherine Coker from the Texas A&M University library in College Station, Texas, and Silke Geiring from the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich, Germany.

Fig. 1 (left): Histoire de Miss Jenny, 1764, Part 3

Fig. 2 (right): Histoire de Miss Jenny in Oeuvres complettes de Madame Riccoboni, 1786, Vol. 3

Nearly all of Riccoboni’s novels including Miss Jenny exhibit feminocentricity, a focus on female characters and their lives. This is reflected not only in their titles (see table above), but also literally in their illustrations with a woman usually occupying the center of the illustration, like here. It may however surprise modern readers/viewers that the selected scene here depicts Miss Jenny at her wits’ end about financial problems, slumped to the ground in despair, as a male “savior” delivers money to her. A similar argument applies to Gravelot’s first illustration depicting Miss Jenny just having been born out of wedlock, her mother about to die in bed, and a centered (i.e. central) father figure accepting Jenny from a maid and promising to protect her;18 it resembles his 1761 “Claire veils Julie upon her death”19 illustration for Rousseau. But whereas the two earlier illustrations represent true textual highlights in their original contexts, the events they illustrate in Riccoboni’s novel appear more trivial and anti-feminocentric. Gravelot’s fourth illustration shows Miss Jenny’s male benefactor whom she agreed to 18. http://sites.univ-provence.fr/pictura/GenerateurNotice.php?numnotice=B1080&premiere

marry having been killed by the bigamist who had married her earlier. Her female friend has fallen at his feet as she herself enters the room. Once more, the heroine is literally marginalized in favor of a male savior/benefactor figure, challenging the illustration’s feminocentricity. This image in turn may have inspired a 1769 illustration by Gravelot for Marmontel’s Contes moraux.20

An example of not merely marginalizing the heroine but rendering her entirely invisible in favor of male characters can be found in Lettres de Sophie de Vallière (1772), one of Riccoboni’s longest and (therefore) least popular novels. It recounts the identity quest of a young woman orphaned at birth, Sophie, adopted and then rejected, who traces her roots and gains a husband and substitute father in the process. The novel’s first two illustrations are entirely feminocentric and situated in the private sphere: the first shows Sophie being adopted by her substitute mother and the second depicts her supported by two female friends as she uncovers part of her origins. Its third illustration, however, depicts a male chase at sea, a conflict between the man in the water —Sophie’s father—and one of the men in the boat—Sophie’s substitute father—over a woman—Sophie’s mother—who is curiously absent from the illustration although on board the boat in the narrative. This picturesque yet relatively minor event undoubtedly appealed to male readers and collectors with its sense of adventure and heroism yet was selected for illustration at the expense of numerous other, textually more relevant events; its depiction also eliminated the only woman and most significant person in the scene.

Fig. 3: Lettres de Sophie de Vallière in Oeuvres complettes de Madame Riccoboni, 1786, Vol. 4

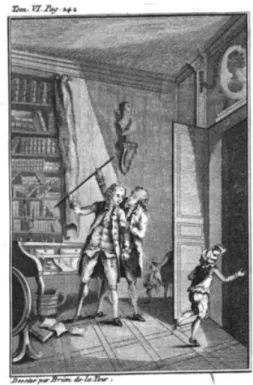

There is one additional illustration without female presence in Riccoboni’s 1786 collection. It accompanies her 1776 final novel, Lettres de Milord Rivers à sir Charles Cardigan, which constitutes her least feminocentric work, as its title indicates. Two men correspond with each other mostly about philosophy and morality, and Milord Rivers, a tutor, has fallen in love with his young female student, whom he ends up marrying. The only illustration for this novel depicts a mere anecdote in it yet quoted specifically by contemporary (male) critics for its political significance.21 It shows a library with a writing desk, the protagonist Rivers, his uncle and a boy, in an apparent association between men and the creation and gathering of knowledge. The uncle tries to hit the slave boy with a stick, but

Fig. 4: Lettres de Mylord Rivers in Oeuvres complettes de Madame Riccoboni, 1786, Vol. 6

Rivers prevents him from doing so. Nathalie Ferrand, in a rare analysis of Riccoboni’s illustrations, points out the irony between this Enlightenment knowledge and the racism exhibited because the slave boy had spilled water on the uncle’s anti-slavery writings (143-44). In terms of gender, no woman is present in this scene in the narrative and participating in the racism. Riccoboni did not routinely include political issues in her writings, but she wrote this anti-slavery scene in 1776, seven years before Olympe de Gouges’s L’Esclavage des noirs and Claire de Duras’s Ourika.22 However, whereas racial discrimination and abuse in the private sphere can apparently be both narrated and visualized, the same does not apply to emotional and sexual abuse of women by men.23

21. See for instance the 1777 Journal Encyclopédique.

22. See Translating Slavery for analyses of gender and race in these and other writings by French women. 23. Mary Trouille offers an extensive and insightful study of wife abuse in eighteenth-century France, both as presented to the courts and in fiction.

A blatant example of not visualizing sexual abuse of women by men in order to make readers/viewers forget ugly truths (Martin 34) can be found in Lettres de Juliette Catesby, Riccoboni’s best-selling third novel published in 1759. In the plot, Juliette, a wealthy widow, agrees to remarry. Shortly before the wedding, her fiancé attends a friend’s wedding and upon his return, cancels his own wedding and promptly marries someone else. After his wife dies, he returns to Juliette who forgives him and marries him, even after learning that he had “accidentally” raped and impregnated the other woman. Yet, in the only illustration gracing this novel we see three women, including the heroine seated on the right and her maid on the left, outside, near a harbor, without any men. The scene is visually attractive yet again very minor within the novel.24 During a walk, Juliette Catesby learns from a flower seller named Sara that she is upset because her fiancé’s grandfather has broken off her engagement. Since her fiancé has inherited some money, the grandfather now wants a larger dowry, which her mother refuses to give. Wealthy Juliette supplies the money so the couple can get married.

Although contemporary readers such as the prominent critic Grimm may have found “the little episode with Sara charming” (403) and undoubtedly appreciated this peaceful, flowery yet narratologically trivial illustration, feminist literary critics25 focus on its non-represented polar opposite, one of the most private and darkest (literally) indoor scenes possible, a violent de-flowering (“déflorer” in French)26 which Grimm merely called an “adventure” (402). Although rape constitutes the ultimate example of the dark forces of the private sphere conspiring against women and the key scene in the novel, it is not visualized here.

Fig. 5: Lettres de Juliette Catesby in Oeuvres complettes de Madame Riccoboni, 1786, Vol. 1

24. Joan Hinde Stewart argues that it constitutes a comment on marriageability as it relates to the lower classes (128-30).

25. Such as Sol 101, Lanser 29.

26. According to the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, it carried the same meaning in eighteenth-century French.

In a feminist visual arts criticism context, the area where the three women interact demonstrates features of the “spaces of femininity” aptly analyzed by Griselda Pollock. Thus, although supposedly outside on a walk, the women appear to be in an interior (private) space together with the visual artist and the reader/ viewer, in the foreground, which establishes “a notional relation between the viewer and the wom[e]n defining the foreground, therefore forcing the viewer to experience a dislocation between [their] space and that of a world beyond its frontiers....” (63). The ships represent that “world beyond its frontiers” i.e. the public space of masculinity and denote trade, travel, and endless horizons. Through their location and unnatural separation, framed by the tall (phallic) building on the left, they demarcate the foreground as a private space of femininity. Women, even when supposedly outside, need to be restrained to private spaces, where they can sit prettily and passively as the object of the male gaze without participating in the public sphere.

Another typical space of femininity, the drawing room, the intimate space where reading and/ or writing take place, is depicted in the illustration that accompanies Lettres de Mistriss Fanni Butlerd, Riccoboni’s first novel published in 1757. It tells the tale of a young non-noble woman whose noble lover abandons her for a better prospect. She avenges herself by publishing their correspondence in order to expose him publicly. This plot again addresses the public and private sphere debate, while highlighting one of Riccoboni’s recurring themes, namely that men can treat women as they please in the private sphere without being held accountable. Feminist interpretations focus on the importance of Fanni going public with her story of betrayal and abandonment and on the fact that she decides to give herself to her lover instead of giving in to him.27 Not surprisingly, the novel’s only illustration does not depict Fanni giving herself to her lover, but rather a very minor scene where a secondary male character, not the treacherous lover, breaks a tea cup in the foreground. The picturesque metaphor of a man breaking a cup into pieces undoubtedly appealed more to readers/viewers both male and female than a man breaking unmarried Fanni’s heart and virginity or her exposing his betrayal. Although the illustration, a domestic tableau with characters in a nicely decorated drawing room, drinking tea and scaring the cat when the cup falls, is set in the private sphere, it does not show the dark side of men and women living together directly as addressed by Riccoboni’s novel.

Lettres de Fanni Butlerd in Oeuvres complettes de Madame Riccoboni, 1786, Vol. 1

Even though the originality of Riccoboni’s protagonist’s solutionrevenge by boldly going publicescaped contemporary critics, it has fascinated modern critics, not only in a framework of original protofeminist justice but also as a parallel context to Riccoboni’s own publishing experience as a woman. In fact, Riccoboni published a preview of this novel in the January 1757 Mercure de France28 foreshadowing Fanni’s gesture. In the illustration we merely see the narrator Fanni Butlerd writing a letter in the background. Only 27% of French women were literate,29 yet women writing and reading formed a popular recurring theme in the visual arts, while also reflecting both the novel’s own modes of production and consumption.

Not all illustrations describe narratologically trivial moments. Thus, the Fanni Butlerd image should be compared to another one set in a drawing room where a tea cup plays a prominent role, namely the one illustrating Histoire du Marquis de Cressy (1758) and visualizing the novel’s final and crucial scene. Here we see a man, the marquis, serving a cup of tea to his wife at night while another woman looks on. Although it appears to be a sweet and intimate domestic moment, it represents in fact one of the darkest moments in Riccoboni’s fiction (hence the candles). The marquis is a rake wishing to climb his way up the social ladder through marriage. To that end he gets involved with multiple women yet eventually marries his wife. When she uncovers his betrayal, she decides to commit suicide and puts poison in her tea cup, which she then asks the unsuspecting marquis to hand her and drinks in front of him while confronting him about his treachery. One of his mistresses watches unknowingly. In this single instance where a rake preying on women is portrayed, he looks elegant, polite and helpful, not criminal and duplicitous. The moment selected for visualization occurs right before the denouement, 28. See “Lettre traduite de l’Anglois…”

29. 48% of men were literate in 1786-1790. The number had risen from 29% and 14% for men and women respectively a century earlier (Melton 82).

which will kill her and burden him with guilt for life, yet the victimization for either one of them is not shown.

Fig. 7: Histoire du Marquis de Cressy in Oeuvres complettes de Madame Riccoboni, 1786, Vol. 2

Histoire d’Ernestine (1765) offers an antithetical marquis and an interesting variation on the theme

of “spaces of femininity”. La Harpe, another prominent eighteenth-century critic, called the novel Riccoboni’s “diamond” (21). Ernestine, a miniature painter, paints, falls in love with, and eventually marries a marquis, overcoming obstacles such as class differences and his arranged marriage. This image displays an instance of visual arts auto-representation, as Brion de la Tour depicts Ernestine in the background (in the relative dark) teaching a female pupil how to draw/paint a male model, possibly the marquis. In the foreground (in the light) she falls in love with the marquis who appears closest to the viewer and thus of greater importance. Given that the facial features here do seem constant, Ernestine is seen twice in this illustration, reflecting two different parts of the narrative simultaneously.

Fig. 8: Histoire d’Ernestine in Oeuvres complettes de Madame Riccoboni, 1786, Vol. 5

In terms of gender, Ernestine presents a rare portrait of a woman working to earn a livingjust like Riccobonian anomaly in Enlightenment fiction. While other illustrations show private spaces of femininity such as the drawing room, the boudoir or the bedroom, this one depicts a unique professional feminine space, the artist’s studio. Just like the illustrations accompanying Riccoboni’s non-novelistic texts in the 1786 collection, the male/female couple in love is chosen as the object of the illustration with the love plot—featuring the man more prominently—literally overtaking the professional one, like in the novel. Nevertheless, the background visualizes an alternate space of femininity, that of the professional woman. Equally importantly, the marquis is shown as the only “passive” man in these illustrations, i.e. the only one not acting (upon women) but rather an object of the female gaze; perhaps not coincidentally, he embodies arguably the author’s most positive male character.

At the intersection of literary criticism, gender studies and visual arts studies, our examination of the role played by gender in the illustrations accompanying Riccoboni’s novels does not sanction feminist claims for the visual arts domain similar to those made by literary critics for her novels. In line with other eighteenth-century French illustrated novels, the scenes selected for illustration routinely do not correspond to narrative highlights, which, at least for Gravelot’s illustrations, suggests that they were modeled after previous images created for other authors and texts, including Rousseau’s Julie. The 1786 illustrations mostly represent the predictable settings described by Martin, seemingly wishing to appeal foremost to readers’/viewers’ sense of esthetics while avoiding anything visually unpleasing. All illustrations locate women expressly in distinct “spaces of femininity” in the private sphere and

Fanni Butlerd’s bold publication efforts are not displayed in the public sphere. Ernestine forms a minor

female miniature painter’s professional studio as such a space in its illustration.

Despite the era’s preference for visualizing female bodies and Riccoboni’s textual feminocentricity, the illustrations to her novels display a distinct preference for men and their actions when compared to the novels, with only a couple of them privileging women only. In their interpretation of the novels, the illustrations show men as upstaging, marginalizing or even suppressing women altogether to an extent not warranted by the narratives. Men look like gentlemen, heroes, saviors, victims of male violence or—at worst—clumsy while drinking tea, never like rakes or criminals. The illustrations hint at male violence against both male and racial others, although the former is depicted only through its victim and the latter as not being condoned. Men victimizing women in the private sphere through betrayal, abandonment, bigamy and rape, however—the core of Riccoboni’s protofeminist statements in her novels—is not visualized in the illustrations, as it would undoubtedly shock readers/viewers, despite it being condoned. Given the major discrepancy between Riccoboni’s textual and visual messages and even though we know from her correspondence that she participated in the business side of the visual arts process at least in 1764, she likely did not involve herself actively in its artistic side, unlike Rousseau with Julie. Alternatively, she may have been involved, selecting what episodes to illustrate or simply giving her (dis)approval of finished drawings, yet may not have insisted the illustrations correlate with her protofeminist textual messages as the images had to be mediated through multiple levels of male visual artists (illustrators, engravers) rather than simply be written into her novels, a process entirely under her own control. In 1786, when she was seventy-three years old and had slowed down dramatically professionally, that mediation process involved even more, and different, artists. In the end, these illustrations produced by male visual artists visualize the role gender played in eighteenth-century-French narrative illustrations in that they show to what extent a woman’s text illustrated in a man’s world resembles Riccoboni’s real phallocentric world much more closely than her fictional protofeminist world.

Works Cited

“Annonces et notices.” Mercure de France. 6 May 1786. 45. Print.

Bostic, Heidi. The Fiction of Enlightenment: Women of Reason in the French Eighteenth C e n t u r y . Newark: U of Delaware P, 2010. Print.

Cook, Elizabeth Heckendorn. Epistolary Bodies: Gender and Genre in the Eighteenth-Century Republic

of Letters. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1996. Print.

Cronk, Nicholas. “Picturing the text: authorial direction of illustration in eighteenth-century French fiction” Eighteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 14, no. 3-4, April-July 2002, 391-414. Print.

Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, 4th edition, 1762. http://artflproject.uchicago.edu/node/45 Web. Dilke, Emilia Francis Strong. French Engravers and Draughtsmen of the XVIIIth Century. London:

George Bell & Sons, 1902. Print.

Foundation, 2009. Print.

Goldsmith, Elizabeth C. and Dena Goodman, ed. Going Public: Women and Publishing in Early Modern

France. Ithaca, London: Cornell UP, 1995. Print.

Grimm, Friedrich Melchior. Correspondance littéraire. 1759. Vol. 2, part two. 401-03. Print.

Herman, Jan, Kris Peeters, Paul Pelckmans, ed. Mme Riccoboni: romancière, épistolière, traductrice Louvain: Éditions Peters, 2007. Print.

Journal Encyclopédique. January 1777. Vol. 1, part 2. 267-68. Print.

Kadish, Doris Y. and Françoise Massardier-Kenney, eds. Translating Slavery: Gender and Race in

Women’s Writing, 1783-1823. Kent: Kent State UP, 1994. Print.

Kaplan, Marijn S. “Publication, Authorship and Ownership in Marie Jeanne Riccoboni (1713-1792).”

French Review, vol. 88.1, October 2014. Print.

Labrosse, Claude. “Le Rôle des estampes de Gravelot dans la lecture de La Nouvelle Héloïse” Die

Buchillustration im 18. Jahrhundert: Colloquium der Arbeitsstelle 18. Jahrhundert Gesamthochschule Wuppertal, Universität Münster Düsseldorf vom 3. bis 5. Oktober, 1978.

Heidelberg: Winter, 1980. 131-44. Print.

---. “Sur les estampes de La Nouvelle Héloïse dessinées par Gravelot” L’Illustration du livre et la

littérature au XVIIIe siècle en France et en Pologne. Eds. Zdislaw Libera, Claude Jean, Jean

Ehrard. Warsaw: Eds. de l’Université de Varsovie, 1982. 83-103. Print. La Harpe, Jean François de. Lycée, ou cours de littérature. Paris: 1798-1804. Print.

Lanser, Susan Sniader. Fictions of Authority: Women Writers and Narrative Voice. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1992. Print.

“Lettre traduite de l’Anglois, Mistriss Fanni à Milord Charle C… Duc de R… ” Mercure de France January 1757, 9-19. Print.

Lewine, J. Bibliography of Eighteenth-Century Art and Illustrated Books. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, 1898. Print.

Lewis, Ann. “Mme Riccoboni au XIXe siècle: une enquête péritextuelle.” Mme Riccoboni: Romancière,

Épistolière, Traductrice. Eds. Jan Herman, Kris Peeters, Paul Pelckmans. Louvain: Éditions

Peeters, 2007. 303-20. Print.

Martin, Christophe. “Dangereux suppléments”: L’illustration du roman en France au dix-huitième

siècle. Louvain, Paris: Éditions Peeters, 2005. Print.

Melton, James Van Horn. The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe. Cambridge UP: 2001. Print. Nicholls, James C., ed. Mme Riccoboni’s Letters to David Hume, David Garrick and Sir R o b e r t

Liston: 1764-1783. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1976. Print.

Pollock, Griselda. “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity.” Vision and Difference: Femininity,

Feminism and the Histories of Art. New York, London: Routledge, 1988. 50-90. Print.

Portalis, Roger. Les dessinateurs d’illustration au dix-huitième siècle. 2 vols. Paris: Morgand & Fatout, 1877. Print.

---. Les graveurs du dix-huitième siècle. 3 vols. Paris: Morgand & Fatout, 1882. Print. Riccoboni, Marie Jeanne. Histoire de Miss Jenny. Paris: Brocas & Humblot, 1764. Print. ---. Oeuvres complettes de Madame Riccoboni. 8 vols. Paris: Volland, 1786. Print.

Sheridan, Geraldine. Louder Than Words: Ways of Seeing Women Workers in Eighteenth- C e n t u r y

France. Lubbock: Texas Tech UP, 2009. Print.

Sol, Antoinette. Textual Promiscuities: Eighteenth-Century Critical Rewriting. Bucknell UP, 2002. Print.

Stewart, Joan Hinde. Gynographs: French Novels by Women of the Late Eighteenth Century. Lincoln, London: U of Nebraska P., 1993. Print.

Stewart, Phillip. Engraven Desire: Eros, Image, and Text in the French Eighteenth Century. Durham:

Duke UP, 1992. Print.

Supplément au Journal de Paris. 1 December 1790. No. 335. iii. Print.

Trouille, Mary. Wife-abuse in eighteenth-century France. Oxford : Voltaire Foundation, 2009. Print.

Utpictura18. Base de données iconographiques. http://sites.univ-provence.fr/pictura/Presentation.php. Web.

Marijn S. Kaplan is Professor of French at the University of North Texas in Denton, Texas, USA. She has published extensively on eighteenth-century French women writers and can be reached at marijn. kaplan@unt.edu.