MIT LIBRARIES

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

b

531

1415

.cz-Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

ASSET

ALLOCATION

AND

ASSET

LOCATION:

HOUSEHOLD

EVIDENCE

FROM

THE

SURVEY

OF

CONSUMER

FINANCES

Daniel

Bergstresser

James

Poterba

Working

Paper

02-34

September

2002

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper can be

downloaded

withoutcharge from

the SocialScience

Research Network Paper

Collection atMASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE OFTECHNOLOGY

ASSET

ALLOCATION

AND

ASSET

LOCATION:

HOUSEHOLD

EVIDENCE

FROM

THE

SURVEY OF

CONSUMER

FINANCES

DanielBergstresser Harvard Business School

James

PoterbaMIT

andNBER

March

2001 RevisedSeptember

2002

ABSTRACT

The

rapidgrowth ofassetsinself-directedtax-deferredretirementaccounts has generatedanew

setoffinancialdecisionsfor

many

households. Inadditiontodecidingwhich

assets tohold,households withsubstantial assets inbothtaxable

and

tax-deferredaccountsmust

decidewhere

tohold them. Thispaperuses data

from

the SurveyofConsumer

Financestoassesshow

many

householdshaveenough

assets inbothtaxable

and

tax-deferredaccountstofacesignificantassetlocation choices. Italso investigates theassetlocationdecisions thesehouseholdsmake. In 1998,45 percentof households

had

at leastsome

assets ina tax-deferred account,and

more

thantenmillionhouseholdshad

atleast$25,000inbothataxable

and

a tax-deferred account.Many

householdsholdequities in theirtax-deferredaccounts,but notintheirtaxableaccounts,whilealsoholdingtaxable

bonds

in theirtaxable accounts.Most

ofthesehouseholds could reducetheirtaxes

by

relocatingheavily-taxed fixedincome

assets to theirtax-deferred account. Assetallocationinsideand

outside tax-deferred accountsisquite similar,with about seventy percentofassetsineachlocationinvestedinequitysecurities. Fornearly three quartersofthehouseholdsthatholdapparently tax-inefficientportfolios, ashiftoflessthan$10,000in financial assetscan

move

theirportfolio toatax-efficient allocation. Assetlocationdecisionswithin

IRAs

appeartobesensitive tomarginaltax rates;

we

do

not findevidenceforsuch sensitivity inother tax-deferred accounts.We

aregrateful toBrad

Barber,David

Bradford, JoelDickson,Roger

Gordon,Andrew

Samwick, and

John

Shoven

forhelpfulconversations,toAmir

Sufi forassistancewiththe SurveyofConsumer

Finances,andtothe

Hoover

Institution,theNationalInstituteof Aging,and

theNationalScience Foundationforresearch support.Households

have always facedtheassetallocationproblem,havingtodecidewhich

assetstopurchase

and

how much

toinvest ineach of them.But

withtherecentgrowth

ofself-directed retirementplanassets,

many

householdsnow

alsofaceanasset locationproblem. This isthequestionofhow much

of

agivenassettoholdinataxableaccount,and

how much

ofittoholdina tax-deferredaccount. Assetsinparticipant-directedtax-deferredaccountstotalednearlyfivetrilliondollars atthe

end

of 2001, with$2.4trillioninIndividualRetirementAccounts,

and

$2.3 trillionin401(k)-typeplans.At

theend

of1990,

by

comparison,therewere $637

billion inIRAs,

and $735

billion indefinedcontributionplans.The

recentgrowth

of IRAs,401(k)'s,and

other self-directed tax-deferred retirement vehicles hasdrawn

substantial interesttotheinvestmentdecisionsmade

by

households withthese accounts. Assetlocationhas

begun

to attractattentionfrom

researchers inpublicfinanceand

financial economics,and

itisafrequent topicofdiscussion

among

financialplanners.Shoven

(1998)outlined the structureoftheasset locationproblem,

and

observedthattaxminimizationwould

usuallydictateholdingheavily-taxedtaxable

bonds

inthetax-deferredaccount,withless-heavilytaxedequitiesinthetaxable account.Recent

work

by

Dammon,

Spatt,and

Zhang

(2002),Huang

(2001), Poterba, Shoven,and

Sialm(2001),and

Shoven and

Sialm (forthcoming) hasoffered further insighton

theoptimalassetmix

forhouseholdsfacingvarioustax

and

financialcircumstances.Absent

liquidityor other considerations,households should holdrelativelyheavily taxedassets intheirtax-deferredaccount.

Whether

thisimpliesthattaxablebonds

should be heldinthetax-deferredaccount

depends

on

thesetofassetsavailabletothehousehold. For example,Shoven and

Sialm(forthcoming) considerthe assetlocationdecisionfor investors

who

can only holdequitiesintheform

ofrelativelytaxinefficientvehicles,suchashigh-turnoveractively-managedmutualfunds. Ifthese

investorshave accesstotax-exempt bonds, thentheiroptimal assetlocation

may

involve equitymutualfundsinthe tax-deferred account,

and

tax-exemptbonds

inthetaxableaccount.Most

oftherecentresearchon

assetlocationhas focusedon

the derivationof tax-minimizingportfoliostrategies,ratherthan

on

theanalysisofhousehold

portfoliochoices.Three

studies have(1997),is based

on

asurveyof

TIAA-CREF

participants. It findsthat investorschoosesimilar assetallocationsintheirtaxable

and

tax-deferredaccounts,with littleapparent regardforthebenefits oftax-efficientassetlocation.

One

open

issue concerningthisresearchconcernsthe extenttowhich

thebehavior of

TIAA-CREF

participantscan begeneralizedtothepopulationatlarge.A

second

study,Barberand

Odean

(forthcoming), isbasedon

datadrawn from

brokerage firmrecords.

The

datasuggestthathouseholds holdequitymutual fundsand

taxablebonds

intheirtax-deferred accounts,while theyholdindividual equitiesin theirtaxableaccount.

Because

individual equityholdings tendtobelessheavily taxed than

bonds

orequitymutual

funds,this assetlocation patternisbroadlyconsistentwith tax-minimizingbehavior.

However,

householdsaremore

likelytotrade stocks intheirtaxablethanin theirtax-deferredaccount,

even

thoughtradingin the tax-deferredaccountwould

notgenerate currentcapitalgains taxliability.

A

key

concern withthisstudyisthedegreetowhich

dataon

assetsheldthrougha singlebrokerage firmdepict ahousehold's broader balancesheet,

and

inparticularwhether

householdsmay

have

offsettingpositionsatother financialinstitutions.Finally,athirdstudy,

Amromin

(2002),usesdatafrom

theSurvey of

Consumer

Financestoinvestigate

whether

precautionarydemands

forfinancial assets,coupled withpenaltiesand

restrictionson

withdrawing

assetsfrom

tax-deferred accounts, canexplain deviationsfrom

tax-efficientassetlocationpatterns.

The

paperalsoprovidessummary

informationon

tax-deferredaccountholdings.The

findingssuggestthatthe standard deviation

of household

laborincome

isrelatedtoassetlocation choices,withhouseholdsin lessriskyoccupationschoosing

more

tax-efficientasset locations. Thispaperrepresentsanimportantstep

toward

buildingmodels of

the factorsthataffectassetlocation choices.In thispaper,

we

also usedatafrom

severalSurveysof

Consumer

Finances(SCFs)

toanalyzeassetlocation decisions.

The

SCF

dataprovide completeand

disaggregatedataon

the portfoliosheldby

alarge

sample

of households.The

SCF

askshouseholdstoaggregatetheirholdingsacrossallfinancialintermediaries. This

makes

itpossibletostudythe overall structureofthe householdportfolio,ratherthanThispaper has

two

goals.The

firstis todescribe theimportance ofthe assetlocationproblem,asmeasured

by

thenumber

ofhouseholdsfacing asset location decisionsand

thevalue ofthe assetsheldby

households with suchchoices.

The

second istoexplore assetlocationpatterns,and

to relatethesepatternstohouseholdcharacteristicsthataffectthe gains

from

tax-efficientasset location,particularlyhousehold marginaltaxrates.

The

paperisdividedintofive sections.The

firstpresents informationon

thenumber

ofhouseholdsthatface substantivelyimportantassetlocation decisions.

We

identifysuchhouseholdsby

thepresenceofsignificantassetholdingsinbothtaxable

and

tax-deferredaccounts(TDAs).

Sectiontwo

explores

how

householdsallocatetheirassetsintaxableand

intax-deferred accounts. Inthe aggregate,equityinvestments

make

up

more

thantwo-thirdsoftax -deferred financial assetsand

a similarproportionoftaxable financialassets.

The

thirdsectionfocuseson

assetlocation decisions. Itdevelopsa simpleclassificationrule toindicate

whether

ornothouseholdsaremaking

assetlocation decisionsthatare taxefficient.

We

developseveralpossiblemeasures

oftax efficiency,and

we

present estimatesoftheportfolioreallocationthat

would

beneeded

tobringhouseholdsintax-inefficientpositionsto tax-efficientpoints. Sectionfour presents cross-sectional regression

and

discretechoiceevidenceon

the correlationbetween

varioushousehold

characteristicsand

assetlocationpatterns.We

investigate age,income,and

net

worth

patternsintax efficiency,and

studyhow

ahousehold'smarginalincome

taxrateaffectsthelikelihoodthatitsassetlocationchoicesaretax-efficient.

A

briefconclusion suggestsdirections forfutureresearch.

jL

How

Many

Households Face

AssetLocationChoices?The

recentexpansion oftax-deferredaccountshas includedIndividualRetirementAccounts

(IRAs),

which

are availabletoalltaxpayerswith earned income, 401(k)plans,which

areemployer-provided definedcontributionplansavailableat

some

firms,403(b)plans,which

aresimilarto401(k)plansbutare availableto

employees

atnonprofitinstitutions,and

anumber

ofothersmallerprograms.characteristicsofthose

who

participateinthem. Table1shows

thetotalvalueofassetsheldintax-deferredaccountsasafractionoftotalfinancialassets forselected yearsduringthelast

two

decades.The

TDA

sharewas

16.8percentattheend

of 2001, almost doublethesharein1985. Tax-deferredassetsareroughlyequallydivided

between

IRAs

andvarious typesofdefined contributionpension planaccounts.A

growing

fractionoftheassets in

IRAs

were

actuallyaccumulatedinpensionaccounts,and

then"rolledover"toanIRA.

The

aggregatedataillustratethegrowing

importance ofIRAs

and

401(k)s, buttheydo

notindicate

how many

householdshave

substantialbalances bothinTDAs

and

intaxable accounts,and

thusface substantivelyimportantassetlocationproblems.

To

investigatehow

many

householdsfallin thisgroup,

we

usedatafrom

the 1989, 1992, 1995,and 1998

Surveys ofConsumer

Finances (SCFs).The

SCF

isthebest availablesource ofdataon

household wealthand

itscomponents.

Itasksa relativelycomprehensive

setofquestions,hasa largesample

size,and

oversamples highnetworth

households.The

1998SCF, which

isdescribedby

Kennickell,Starr-McCluer,and

Surette (2000),sampled

4309

households, with

2813

intherandom

sampleand 1496inthestratifiedrandom

samplethatover-weightedthosewith highincomesor net worth.

By

combining

anareaprobabilitysample withahigh-incomeoversample,the

SCF

provides accurate informationon

broad populationcharacteristics,whilealsoofferingin-depthinformation

on

thehouseholdsthatholda disproportionateshareoffinancialassetsand

networth.Four householdsareexcluded

from

the publicusedatasetduetodisclosureconcerns, leavingasample

with4305

observations.One

fourthofthehouseholdsinthesurveyhave

networth of overa milliondollars. Allof ourtabulationsweightthevariousobservationsinthesurvey

by

theirsampling weightssothatourreportedstatisticsshouldberepresentativeoftheU.S.population.

We

measurethetotal valueofthe assetsheldintax-deferredaccountsas thesum

ofassetsheldin401(k)s, 403(b)s,IRAs, and supplementalretirementaccounts(SRAs).

We

excludethe valueofassets insome

traditionaldefined contribution plansthatdo

notfallintothesecategories,sincesome

oftheseplansmay

notallowparticipantsmuch

controlovertheirassetallocation decisions. Thisexclusionprobablyleadsustounderstate the valueoftax-deferredassets thataredirectlycontrolled

by

individualinvestors.A

similarallocation

may

limitindividual controlof investmentoptions.We

neverthelessincludeall401(k)planassets,becausevirtuallyall401(k)participantscontrolassetallocationdecisionsforatleast

some

oftheirholdings.Table 2presents

summary

informationon

thepercentageof households withtax-deferred accounts.The

firstcolumn shows

thepercentage withIndividualRetirement Accounts, 401(k)plans,403(b)plans,orotherself-directedretirementsavingplans. This percentagerises

from

30.7percentin 1989to45.7percentin1998.

The

nextcolumn shows

thepercentageof households withfinancial assets,excludingtransactionaccountssuchascheckingaccounts, outsidetheir

TDA.

Approximately

45 percentofthehouseholds ineachofthefourSurveys of

Consumer

Financesreportownership oftheseassets. This percentagewould

bemuch

greaterif

we

includedfinancialassetsintransactionaccounts.We

excludethem on

thegroundsthattheydo

notreflectlong-terminvestmentpositionsinthe

way

thatTDA

balancesdo.The

lastcolumn

inTable 2shows

thepercentageof households witheithertaxableor tax-deferredassets. Thisgroup accountsfor55percentof householdsin 1989

and

63percentin 1998.These

dataillustratetherapidgrowth duringthelastdecadeintheshareof households with

some

involvementin financialmarkets.Table3 presents

more

detailedinformationon

thesetof householdsthatfaceassetlocationproblems. It

shows

thenumber

of households withTDA

balances,andnon-TDA

balances,above

variousthresholdlevels in 1989

and

1998. Assetthresholds aremeasured

inconstant 1998dollars,and

theshadedentriesalongthe diagonal

show

theresultswhen

we

applythesame

thresholdtobothtaxableandtax-deferred accounts.

The

assetthresholdsdo

notadjust forthedeferred taxes associatedwithholdingsinsideTDAs,

or the greater prospectiveafter-taxreturnsassociatedwithassetsheldintheseaccounts. Poterba(2002)suggeststhatfortime horizonsof

between

25and

40

years,thesetwo

factorslargelyoffseteachother.The

upperpanelof Table3presentsinformationfrom

the 1989SCF,

whilethelower panelpresentsdata

from

1998.The

lowerpanelshows

that in 1998, 30.3 millionhouseholdshad

positiveamounts

of bothtaxableandtax-deferredassets.

Over

halfofthesehouseholdshad

significantamounts

inbothaccounts; 15.6millionhouseholds

had

more

than $10,000inboth,while 10.3 millionhouseholdshad

more

than$25,000inhouseholds,

had

more

than$100,000inbothtypesofaccounts. Thisgroup,which

accountsfor justover3percentofallhouseholds,heldalmost

42

percentofnon-transactionaccountfinancial assets.Comparing

theentriesinTable3for1989and

1998 demonstratesthegrowing

importance ofassetsintax-deferred accounts,and ofthe assetlocationissue. In1989, 8.6 millionhouseholdshad

more

than$10,000, and2.6million

had

more

than$50,000,inbothtaxableand

tax-deferredaccounts.These

amounts

are

measured

in 1998dollars.Between

1989and 1998, thenumber

ofhouseholds withtax-deferredassetsabovevarious thresholds

grew

much

more

rapidlythanthenumber

of households withtaxableassetsabovevariousthresholds.

To

place tax-deferredassetholdingsinthebroadercontextof householdportfolios,Table4

presentsinformation

on

the distributionoftheratioofTDA

assets tototalfinancial assets for the 1998SCF.

Assetlocationissuesare

more

importantforhouseholds withlargeTDA

balances thanforthosewithsmallbalances.

They

arerelativelymore

importantforhouseholds with roughlysimilarholdingsinsideand

outsidetheir

TDAs.

Forahousehold withaportfolioalmostentirely inthetaxableaccount,the assetmix

withinthe401(k)

may

beoflittleconsequence,sincethe valueofthe401(k)atretirementmay

represent a smallfractionoftotalwealth. Forahousehold with almostallofitsassets inthe

TDA,

theassetlocationdecisionisalsooflittleconsequence

—

theremay

betoofew

assetsoutside theTDA

toallowmuch

flexibility.Table4

shows

that in 1998, themedian

household with bothtax-deferredandtaxablefinancialassetshad

57.1percentofitsfinancial assets ina tax deferred account.At

the25thpercentilethisvaluewas

28

percent,whileatthe75thpercentileit

was

85.6 percent.Thus

thereissubstantialdispersionintheshareofassetsheldin

TDAs,

and

asubstantialnumber

of households havebetween

aquarter,andthree-quarters,oftheir financial assets inthese accounts. Forhigher networthhouseholds,the distributionoftax-deferred

assets relative toallfinancial assetsshiftstowardtheleft.

The

median

valueofthisratioforhouseholds withat least$250,000innetworth,forexample,is47.9percent,

compared

with57.1 percentforallhouseholds.The

measure

ofnetworth usedforthiscutoffincludes non-financialassets,andifwe

limitour sampletohouseholds withfinancial assetsof

more

than$250,000,we

findthatthemedian

household has only42.3the networthandfinancial asset distributions,asubstantialgroup of households have

TDA

and

non-TDA

holdingsthatareofsimilarmagnitude.

Not

surprisingly,networthisstrongly correlatedwithTDA

balances.The median

networth ofhouseholds with

more

than$25,000inbothtaxableandtax-deferredaccountsis$510,000, whilethemedian

forthosewith

more

than $100,000inbothsettingsis$1.18million. Inbothcases,mean

networthissubstantiallygreaterthan

median

($1.31 millionforthosewithmore

than$25,000inbothsettings,and $2.58millionforthosewith

more

than $1 00,000).Income

alsoriseswithTDA

holdings.Median

householdincome

risesfrom

$81,200forthosewithmore

than$25,000inboththeTDA

andthetaxable account,to$124,900forthosewith

more

than$100,000

ineachsetting,whilethemedian

ageofthehouseholdhead

rises

from

54to 56.The median income

statisticsdo

not capture asignificantnumber

ofretiredhouseholdswithlargeholdingsof both

TDA

and

non-TDA

financial assets,butrelativelylow

currentincome.2. AssetAllocation Patterns

The

datainthelastsectionsuggestthatroughlythirtymillionhouseholdsfacedassetlocationdecisionsin1998,andthatroughlyfifteenmillion

had

atleast$10,000inataxableaswellasatax-deferredaccount.

A

substantialshareofthehouseholds withsignificantTDA

balanceshad

similarbalancesinsideand

outsidetheir

TDAs.

Forthesehouseholds,decisionsaboutassetlocationcanhaveanon-trivialimpacton

theirlong-runfinancialstatus. Considera45-year-oldcouplewith$100,000ina

TDA,

and

thesame amount

ina taxable account.

Assume

thatthecouplefacesa28

percentmarginalincome

tax rateon

interestand

dividends,

no

capitalgainstax,and

thatbothbonds

and

stocks yield returnsof7 percent peryear,butallofthe

bond income

iscurrentlytaxablewhileonly 2percentoftheequityreturn,thedividendyield,istaxable.Ifthecoupleallocates the

TDA

tostocksand

thetaxableaccounttobonds,and

makes no

subsequentreallocationdecisions,thenatage70,netoftaxespaidtowithdrawassets

from

theTDA,

theywillhave$732,650.

By

comparison,ifthey invest theTDA

inbonds and holdequityin theirtaxable account,thelowertaxburden

on

thebond income

that resultsfrom

holdingbondsintheTDA

will result inanafter-tax8

thatcould haveimportanteffects

on

financialstatus. Inthissection,we

usedatafrom

theSurvey ofConsumer

Financesto investigate assetallocationpatterns,andtheninthenextsection,we

considerassetlocation.

2.1 Survey of

Consumer

Finances Informationon

AssetAllocationFor

most

typesoftax-deferredaccounts, theSurvey ofConsumer

Financesaskswhethertheaccountisinvested 'mostly orallinstock','split

between

stockandinterestearningassets',or"mostlyorallininterest-bearingaccounts,"orin "real estate,""insurance,"or"other." Hardly

any

TDA

assets areheldinrealestate,insurance,or"other."

We

usethisinformationtoconstructestimatesoftheassetcompositionoftax-deferred accounts,

and

tocompare

theseestimateswithcomparableestimateson

thecomposition oftaxableaccounts.

We

allocateall oftheassets inaccountsidentifiedas'mostly orallinstock' toequity,halfofthevalueof'split' accounts,and

none

ofthevalueofotheraccountstoequity.We

thensum

these equityholdings,aswellas thetotalvalueofallaccounts.

The

SCF

doesnot distinguish taxableand tax-exemptbondsinthe

TDA,

butbasedon

evidenceinBarberand

Odean

(forthcoming),we

assume

thatthereareno

tax-exemptholdings.

Forone group oftax-deferredaccounts, the

SCF

collects assetvalues but not thecompositionofassets.

These

are theaccountsof householdswho

had

a defined contributionplanataprevious job, butwho

have notyet rolledtheiraccounttoan

IRA

ortakencashdistributionsfrom

theplan. Nearlythreehundredthousandhouseholds have suchaccounts.

We

includedthesehouseholdsinoursummary

tabulationsintheprecedingsection,butinthisandlatersections,

we

exclude them.The

SCF

asksrespondentstoseparately reportthe dollarvaluesofdirectstock holdings, equitymutual fundshares,

and mixed

equity-fixedincome

mutual fundsharesthatareheldoutsidetax-deferredaccounts. Aggregatingthesereportedassetholdingsprovides a

measure

ofequityheldintaxableaccounts.We

do

not include equityinprivately-heldcompanies,sincesuchassetsmay

beilliquidanddifficulttotransfer

from

the taxabletothetax-deferredaccount.The

SCF

alsoprovidesconsiderabledetailon

fixed-income

assetsheld outsideoftax-deferred accounts.Our

measure of fixed-income assetsincludescertificatesforegoinganalysis,

we

excludethe valueof checking accountsand

money

marketaccounts,on

thegroundsthatholdingsoftheseaccountsare driven

by

liquidityconcernsratherthanassetallocationor taxissues.Tax-exempt bonds

raisespecialproblemsforouranalysis.While

theirrisk attributesaresimilartoother fixed

income

securities, theirincome

istaxedlessheavilythantheincome from

taxablebonds.The

holdersof tax-exempt

bonds

pay

implicitratherthanexplicittaxes,sothe effectivetaxburdenon

tax-exemptbonds

equals the yieldspreadbetween

comparably-riskytaxableand

tax-exempt bonds. Thisyieldspreadisusually smaller than the topmarginal

income

tax ratetimes the taxablebond

yield,soatleastforhouseholdswithrelativelyhigh marginaltaxrates,tax-exemptbondsofferahigherafter-taxreturnthan taxable bonds.

For

some

households,tax-exemptbonds

may

thereforeofferaless risky,butlightly-taxed,alternativetotaxableequity. In

some

of ourcalculations,we

combine

tax-exemptbonds withequitytodescribehouseholdassetallocations

between

heavily-taxedandlightly-taxedassets.Inthe 1

998

SCF,

4.8 percentofallhouseholdsreportedowning

tax-exempt bonds,and

another 1.8percentheldtax-exempt

money

marketaccounts. Ifwe

restrictourattention tohouseholdsthathave bothtaxableandtax-deferredfinancial assets, 11.9percentholdtax-exempt bonds. Thisfractionhasdeclined;it

wasl6.3percentin 1989. In contrast,thepercentofallhouseholds

owning

tax-exemptbonds

hasbeen

verystable.

Most

ofthehouseholdsthatown

tax-exemptbonds

alsoholdtaxablefixed-incomesecurities. In1998,ofthe4.9 millionhouseholds holding tax-exempt bonds, roughlyhalfa million reported

no

financialassetsoutsidetheir

TDA,

andone

millionheldno

corporatestock.2.2AssetAllocation Patterns

Our

analysisofassetlocationdecisionsfocuseson

whether households holdequities in theirtaxableaccountsorintheirtax-deferredaccounts. Table5reportsthefirststepinouranalysis:

summary

informationon

theequityexposure ofSCF

households.The

table alsoshows

thepercentageof householdswho

holdfixed

income

assets,and tax-exemptbonds.The

tablepresentscross-sectionalinformationanditalsodocuments

recenttrends.The

firstpanelshows

thatequity rosefrom

40.4 percentoffinancialassets in 1989to69.7 percentoffinancial assets in 1998. Thisincreasereflectedboth highremrns

and

broadening10

accountsrose

from

27.3percentto45.8percent,whiletheshareofinvestorsholdingfixed-incomeassetsremainedsteadyataround 50percent.

The

shareof households with anyequity orfixed-incomeassetsrosefrom 54to63percentoverthistimeperiod,while theshareholdingtax-exemptbonds

was

steadyatbetween

fourandfivepercent.

The

lowerpanelsof Table5present separateinformationon

financial assetsheldinside,and

outside,tax-deferred accounts. In 1989, the equity shareofassetsheldin

TDAs

(34percent)was below

the equityshareintaxableaccounts(43percent).

By

1998,68

percentofTDA

assetsand

71 percentofnon-TDA

assetswere

heldin equities.The

similarityofthestock-bondmix

insideand

outsideTDAs

raisesquestionsabouttheextentto

which

investorsareconsideringtax factors indecidingwhetherto locate assetsinsideor outsidethe

TDA.

Table5 alsoshows

thatthepercentageofTDA

households withequityin theirTDA

rosefrom

13.3 in1989to34.5in 1998.

Table5 focuses exclusively

on

householdsthatown

equity,and

itdocuments

how

thesehouseholdsown

theirstock. There canbesubstantialtaxconsequencesassociatedwithdifferentmethods

ofequityownership. For example,investors

who

holdstockthroughequitymutual funds cedesome

controlovertheirtaxburdenstofundmanagers'capitalgainrealizationdecisions.

The

firstrow

inTable 6shows

that in 1989,27.3percentof households

owned

stock. Thistotalcan bedisaggregated: 7.3percentheld equityonlythroughtheir

TDA,

6percentheldequitybothinsideand

outside theTDA,

and

14percentheldequityonlyoutsidetheir

TDA.

The

tablealsoshows

that 14 percentofallhouseholds(10.2+

3.8)had

onlydirectequityholdings,while 6percent(1.1+1.1+1.8+2.0)heldat least

some

equitythroughamutualfund.These

summary

statisticschanged

duringthe 1990s.By

1998, 12.4 percentof households heldtaxableequityonlythroughstock

owned

directly,while15.3percentheldsome

taxableequitythroughamutual fund(15.3

=

4.7+4.8+2.1+3.7).The

percentageofthe populationholdingatleastsome

equity roseto45.8 percentin 1998,

and

thiswas

theresultofrisingnumbers

who

held equityonlyinaTDA

(from7.3percentto 18.1 percent) aswell asbothinsideandoutside a

TDA

(6percentto 16.4percent).The

datafrom

theSurvey of

Consumer

Financesdocument

apronounced

trendtowardahigherfractionofequity11

taxburdens

on

stocksand on bonds,sincethe effectivetaxburdenon

equitiesheldthroughintermediariesisoftenhigherthanthat

on

buy-and-holddirectequity investments.Table7 presents information similarto that inTable6, butitdoessoforthecaseof

bonds

ratherthanstocks. For bonds,the difference

between

holdingassetswithinaTDA,

andoutsidesuchanaccount,isveryimportantfordeterminingtheeffectivetaxburden. Inadditionto splittingfixed-income investments

by

TDA

and

non-TDA

location,Table7 also distinguishes taxablefixed-income investmentsintaxableaccountsfrom

holdingsof tax-exempt bonds. Table 7 does notsuggestany changesin

bond

ownershipthatarenearly aspronouncedas thoseforstockownership. There

was

literallyno

changebetween

1989 and 1998inthepercentageof households

-

48.8-

owning

fixedincome

assets.Roughly

onequarterofthisgroupheldfixed-income

assetsinsidetheirTDA

butnotoutside,whilenearly halfheld fixedincome

assetsoutside theTDA

butnotinside. There hasbeen

some

increase,from

8.8percentto 13.1 percent,inthepercentageofhouseholds with fixed-income investmentsheldonly throughtheir

TDA,

and

adecline,from

25.6to22.7percent, inthe setof households withfixed

income

heldonlyoutsidetheTDA.

The

overwhelming

majorityof

SCF

households holdno

tax-exempt bonds, althoughthosewho

do

holdthesebonds

tendtobeinthehighest networthstrata,

which

makes

theaggregateportfolioshareheldinthesebonds

significant.3. AssetLocation Decisions

We

now

exploreassetlocationchoicesinthe Survey ofConsumer

Finances.We

begin withasummary

ofthese choices. Table8 presentsinformationon

thenumber

of householdswho

reportvariousassetlocation patternsinthe 1998

SCF.

The

columns

ofthistableindicatewhether households havetax-deferred accounts,

and

ifthey do,what

assets(onlyequity, only bonds,and

some

combination)theyholdintheseaccounts.

The rows

describethe assets thatthehouseholds holdin theirtaxableaccounts.We

combine

tax-exempt

bonds

withequitiesheldintaxableaccounts.The

tableshows

thatthereare 46.2 millionhouseholds withassets intax-deferredaccounts; theseare thehouseholdsin

columns

two

throughfour.Of

thisgroup, thereare30millionhouseholds withtaxableassetsoutside the

TDA.

Thisisthegroup of12

We

definetax-minimizingassetlocation patterns asonesthatallocatefixedincome

assets totax-deferredaccountsbefore taxable accounts.

Households

thatfollowsuchassetlocation patternsarelabeledastaxefficient.

The

entries inTable8thatarelightlyshaded correspondtoassetlocation patternscouldbetax-minimizing.

The

darklyshadedthe entriescorrespondtoinvestmentpatterns thatdo

notappeartobeconsistentwithtax-minimization. Thereare 10.8millionhouseholds(23.4 percentofallhouseholds with

TDAs,

and 36

percentofthosewithTDAs

as well as taxableassetsoutside theTDA)

holdingonlyfixed-income

assets in theirTDAs.

Thisisagroupthatmight beallocatingtheirhighly-taxedassets to theirtax-deferredaccount. Less thanhalfofthisgroup,however,4.1 millionhouseholds,holds

any

equity outsidetheTDA.

These households,who

arefollowingastrict"bonds

intheTDA,

stocksinthetaxableaccount"allocationrulerepresentlessthanonetenthofthehouseholds withtax-deferredaccounts,

and

13.6percentofthosewith both

TDA

and

non-TDA

financial assets.Table8 also

shows

thatthereare2.5millionhouseholds with onlybonds

intheTDA,

and

onlybondsoutside the

TDA.

Thisgroupmay

alsobe followingatax-minimizingassetlocationstrategy,asmay

bethe4.9 millionhouseholds with onlyequityin their

TDA

andin theirtaxableaccount. Forahousehold withrisktolerancethatpointstoward holding onlystocksorholdingonly

bonds

inbothsetsofaccounts, thereisno

effective assetlocationdecision.

One

additional group, thosewithbonds and

stocksintheTDA,

andstocksinthetaxable account,couldalsobetax-rninimizing. Thisgroupconsistsof2.3millionhouseholds.

Adding

allofthesegroupsinthe lightlyshaded boxestogether,thereare 13.8millionhouseholds

~

29.9 percentofallhouseholds with

TDA

assets,or46

percentof

thosewithbothTDA

andnon-TDA

financial assets- who

may

be following tax-minimizingassetlocationrules.Table8 also

shows

thatthereisasubstantialgroupof householdsthathold both fixed-incomeandequity investments, but

who

holdalloftheirequities inside theirtax-deferred account.These

householdsareindark-shadedentriesofthetable. Thereare 6.5(=3.3

+

3.2)millionhouseholdsthathold onlyfixed-income

securitiesoutsidetheirTDA,

while holdingeitherallequitiesoramix

ofbonds and

stocksintheTDA.

These households appeartobe followingjust thereverseofthe"bondsintheTDA"

strategy. Another13

Thereare9.7 millionhouseholdsthatreportonlyequityinthe

TDA

orbothequityand

fixed-incomesecurities inthe

TDA,

and

holdingsof bothequityand fixed-incomeassetsoutsidetheTDA.

These

households,likethose

who

holdbonds

outside theTDA

and

stocksintheTDA,

could probablyincreasetheirafter-tax financial assetsatretirement

by

adjustingtheirportfolio toholdmore

oftheirfixed-incomeinvestmentsin theirtax-deferredaccount,whilepreservingtheir overallriskexposure.

The

entries inTable8useastark criterion forinclusionincategoriessuchas"onlyequityin theTDA." To

capturehouseholdsthathave mostlyequityintheTDA, we

repeatedthecalculationsthatunderliethetableusing"greaterthan

80

percentoftheTDA

investedinequity"inplaceofthe 100percent cutoffinTable8.

We

made

similarchangesinourother categorizationcriteria,replacingany

100percent cutoffwith80percent,

and

percentwith20

percent.The

resultsarebroadlysimilartothe findingsinTable8,althoughfewer householdsare classified asfollowingstrategies thatarenottaxminimizing

when

we

takethisapproach.

Of

the46.2 millionhouseholds withTDA

assets,3.8millionhavemore

than80percentoftheirTDA

inequity,and

lessthan20

percentoftheirtaxableaccountinequity. Thiscompares

with3.2millionhouseholds inTable8withall oftheir

TDA

inequity,andalloftheirnon-TDA

assets infixedincome.The

number

of households followingassetallocation patternsthatarenot taxminimizing,and

aredark-shadedinthetable,dropsfrom16.2millionto 10.5million

when

we

usethelooser categorizationcriterion.Summary

statisticslikethoseinTable8 provide a useful perspectiveon

assetlocationdecisions.We

havealsopresentedthisinformationina graphical format. Figure 1plotsthebivariate distributionof

householdasset allocationdecisionsintaxable as wellastax-deferredaccounts.

The

concentrationofhouseholds with

TDA

equityallocationsofzero,50percent,and

100percentreflectsinpartour procedureforturning categoricalresponsesinthe

SCF

into quantitativemeasures.The

figureshows, however,thatthereisa verysubstantialconcentrationof householdsinthe four cornersofthedistribution. Thereare

two

mass

pointsinthedistribution,correspondingtomore

than80percentequityallocationinboththeTDA

andoutside the

TDA

(28.3 percentofthehouseholds withTDAs

and

non-TDA

financial assets)and

lessthantwentypercent equityallocation(justover 10percent).

Amromin

(2002)presents similar information,14

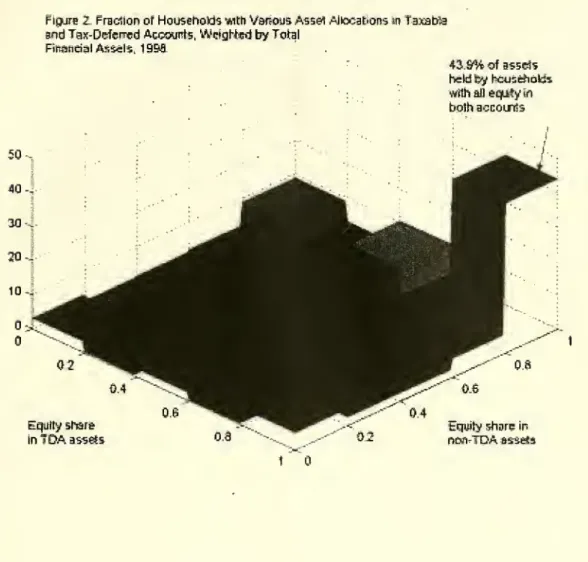

Figure 2 presents information similarto that inFigure 1,buthouseholdsare

now

weightedby

thetotal

amount

offinancial assets thattheyholdinsideand

outsidetheirTDAs.

The

datainFigures 1and 2takentogethersuggestthatthehouseholds with littleor

no

equityin theirTDAs

tendtobe low-wealthhouseholds.

When

we

weightby

financial assets,43.9percentofallhouseholds havemore

than80percentoftheir

TDA

assetsinequity,and

a similarfractionoftheirnon-TDA

assets in equity. Figure2demonstratesthat

most

ofthe assets intax-deferredaccountsareheldinaccountswith highallocations to equity,asthe datainTable5suggested.

Table8

and

Figures 1 and2providesome

insighton

theextenttowhich

householdsarepursuingtax-minimizingassetlocationstrategies,but they

do

notofferaquantitativemeasure

ofhow

closetax-inefficienthouseholdsare to tax -efficient points.

To

addressthisissue,we

compute

theamount

of wealththateach household witha

TDA

and

non-TDA

financialassetswould need

to reallocate inordertoreach atax-efficientportfolio. Table 9

summarizes

the findings.The

firstrow

reportsinformation alreadypresentedinTable8:thereare 16.2millionhouseholdsthatappeartobefollowingtax-inefficient strategiesbased

on

theircurrentportfolioholdings.

The

secondrow

askshow many

ofthesehouseholds holdportfolios thatwould

requireasset

movements

ofmore

than$2500

toreach atax-efficientpoint. For example,ahousehold witha$2000

TDA

balanceinvestedinequity,and

largebond

holdings outsidetheTDA,

couldbe broughttoatax-efficientpoint

by swapping $2000

ofTDA

equityfor debt.Such

ahouseholdwould

be countedastax-inefficient inthefirst

row

of Table9,but notinthesecond.The

resultssuggestthatnearly halfofthehouseholds withtaxinefficientholdingsarewithin

$2500

ofatax-efficient point:only8.5millionofthe 16.2milliontax-inefficienthouseholds cannot be broughttotax-efficiencywithassettransfersof

$2500

orless. Ifwe

allowforasset transfersofno

more

than$10,000 per household,allbut 4.6 millionhouseholds can bebroughttothetax-efficient point.Thisresultsuggeststhat

by moving no

more

than 11.8 millionhouseholds*($10,000), or $118billion,

we

canmove

three-quartersofthetaxinefficienthouseholdstotaxefficient points.

The

informationinTable 9suggeststhatformany

ofthehouseholdsthatarefollowingwhat

15

wealth they

would

accumulateundera taxefficientstrategy,and

theamount

theywillaccumulateiftheycontinuetofollowtheircurrentstrategy.

Table 10 presents another calculationdesignedtoaddress theproximity ofexistingportfolios to

tax-efficient allocations. Itfocuses

on

thetotalamount

of wealththatmust

bereallocatedtoachieveatax-efficientallocation forallhouseholds with

TDAs,

ratherthanon

thenumber

of householdsthathave holdingsthatare inefficient

by

more

thanacertainamount. Sinceassetholdingsarehighly concentrated,resultsbasedon

householdsand on

assetscandiffersubstantially.The

firstrow

inTable1 focuseson

theuniverseofhouseholds with

TDAs

and

positiveholdingsoffinancial assetsoutside theTDA.

In 1998,thetotalbalancein

TDAs

was

$2.64trillion.To move

allhouseholds withTDAs

toatax-minimizingassetlocationwould

requireassettransfersof $250.8billion,orjustunderonetenthof

TDA

assets. Thisisslightlymore

thantwice thetransfer,calculatedabove,that

would

bringallbut 4.6 millionhouseholdsto tax-efficientpoints.Table 10also

shows

thepercentageofassets thatneedtobereallocatedtoachievetaxefficiencyforhouseholds

whose

assetsmeet

various thresholdsforTDA

and

non-TDA

holdings. Forthosewithatleast$250,000inbothtaxable

and

tax-deferredholdings,therequired reallocationis$83billion,orelevenpercentof

TDA

assets.The

required reallocation asapercentageofTDA

assetsissmallestforthosewithsmallholdings

-

thosewho

do

nothave

atleast$25,000inboththeirtaxableandtax-deferred accounts. Forthisgroup, thereallocation

needed

toachievetaxefficiency ($33.9billion)isonly4.3 percentoftotalTDA

assets.Thisreflectsthesmallersize

of

TDA

relative tonon-TDA

assetsforthisgroup,aswellasa greatertendencytoholdtaxablefixed

income

assets intheTDA

among

smallaccountholders.Table 10 also

shows

theaggregateportfolioreallocation thatwould

beneeded

tomove

householdstoequal equity/fixed-income allocations insideandoutsideoftax-deferred accounts.

The

required reallocationisnot

much

largerthan theone

thatisneeded

tomove

allhouseholdstothetax-minimizingasset location.The

comparison ofthese calculationssuggeststhathouseholds appeartobeslightlyclosertothetax-minimizing

outcome

thantoa defaultstrategy thatwould

allocatethesame

fractionof boththetaxableandthetax-deferredaccountto equities.

The

thirdcolumn

of Table 10shows

thereallocationthatwould

be16

each household could hold $25,000infixed-incomeassetsoutsideofthe

TDA

for financialemergencies.Such

abuffer stockmight beattractiveif,asinAmromin

(2002) andHuang

(2001),householdsfacerandom

shocksto theirexpenditureneeds

and

theycanmake

earlywithdrawalsfrom

tax-deferredaccounts onlyatsubstantial cost.

The

required reallocationwhen

we

allowfora buffer stockofnon-TDA

fixedincome

savingisonlyslightlysmaller thanthat

when

we

do

notconsidersuchabuffer.The

notionofafinancialbuffer stock outsidetheTDA

raisesan importantquestionabouttheextentto

which

TDA

and

non-TDA

assets are substitutes. Forindividualsovertheageof 59Vz,who

canwithdraw

assetsfrom

TDAs

withoutpenalty,thedegreeofsubstitutabilityisgreaterthanforyounger

householdswho

facewithdrawalpenaltiesof 10percent.

Depending on

the structureoftheTDA,

theremay

alsobeotherfactors,suchashardship withdrawalrestrictionsin401(k)plans, that limitthedegreeto

which

TDA

assetscansubstitutefor

non-TDA

assets.Our

analysisfocuseson

the tax differencesbetween

assetsheldinsideandoutside

TDAs,

butnon-taxdifferencesshouldalsobe consideredinfuturework.4. ExplainingtheDivergence

Between

Actual Asset Locationand Tax-Minimizing

BehaviorThereissubstantialheterogeneity acrosshouseholdsin the asset allocations thattheychoseintaxable

and

TDA

accounts.While

developingastructuralmodel

oftheoptimalamount

ofequity ordebttoholdinthetax-deferredaccount,giventhe

random

shocksfacinghouseholds,isbeyond

thescopeofthe currentpaper,

we

canexplorewhich

typesof householdsmake

tax-efficientassetlocation decisions.We

do

thisinthreeways. First,

we

estimate probitmodels

for the discretechoiceof whetherornot ahouseholdisinthetax efficientregioninTable8. Second,

we

estimate regressionmodels

toexplain the differencebetween

theshareofthetax-deferredaccountthatisheldinfixed

income

assets,andtheshareofthe financial assetportfoliooutside the

TDA

thatisheldinfixedincome

assets. Finally,we

estimate regressionmodels

inwhich

thedependentvariableistheshareofTDA

assets thatwould

needtobereallocatedtobringthehouseholdtoatax-efficient allocation.

We

considerthehousehold's marginaltaxrate,itsreportedrisktolerance,itsage,networth, and17

rate,are readilyavailableontheSurvey of

Consumer

Finances.Our

marginaltaxratevariableisanestimateofthehousehold's marginalfederal

income

taxrateon

ordinaryincome,constructedusingthealgorithmdescribedinPoterba and

Samwick

(forthcoming).The

benefitofmaking

atax-efficientassetlocationdecisionisincreasinginahousehold's marginal

income

taxrate.We

thereforetestforanassociationbetween

themarginaltaxrateandassetlocationpatterns.Inourestimation,

we

report resultsbothfortheentiresample of households withTDAs

and

non-TDA

financialassets(1709observations),and

forasubsample ofthosehouseholds withIRAs

(1410observations).

Some

householdsinthesubsample haveTDA

holdingsonlyinanIRA,

whileothershaveboth

IRA

andnon-IRA

holdings.When

we

analyze thesubsample withIRA

holdings,we

defineourmeasure

oftaxefficiencyusingonlytheassetsheldintheIRA.Thus

ahousehold with anERA

fullyinvestedinbonds,but a401(k) withsubstantialequity holdings,

and

equityholdingsina taxableaccountaswellwould

beclassifiedastax efficient inthesubsampleanalysis.Our

rationale forfocusingon

thesecondgroupisthatsome

households with 401(k) accountsmay

holdequityintheir

TDAs

becauseofemployer

restrictionson

asset allocation.Many

employersmake

401(k)matchingcontributionsin

employer

stock,and

theyrequireemployees

toholdthisstockforsome

periodoftime. Thiscouldresult in

some

households holdingequityin theirTDA,

even thoughtheywould

prefertochoosea

more

tax-efficient asset allocation.We

haveno

way

toidentifyhouseholds withconstrained holdingsin their401(k)s, so

we

focusonlyon

IRA

holdingsbecause households have completediscretioninallocatingtheseassets.

Table 1 1 presentsthe resultsof ourempirical analysisofthe cross-sectional determinantsofasset

allocation.

The

firsttwo columns

present estimatesofprobitmodels

foradiscretedependentvariablesetequaltounityifthehouseholdexhibits a taxefficientassetlocationpattern,andzero otherwise.

The

basicspecificationis

(1)

Prob(TAXEFFi

=

1)=

<D(p+

5*MTR, + I

of AGE,

+

I

yk*NETWORTH

ik18

where

TAXEFF,

isanindicator variablefortaxefficiency,and

0(.) denotesthestandardnormal

distributionfunction,and

we

include categorical indicator variables for age, networth,and

householdincome.

The

RISK

variables areresponsestothreeSCF

questionsthattrytoelicitahousehold'spreferenceswithrespecttotherisk-rewardtradeoff.

The

coefficientestimatessuggest apositive,althoughvariable, relationshipbetween

householdmarginaltaxratesandthetax efficiency

of

ahousehold'sassetlocation choices. Forthefullsample,thecoefficient

on

thetaxvariableispositive,butstatisticallyinsignificantly differentfrom

zero. Itislarger inabsolutevalue,

and

statisticallysignificantly differentfromzero, fortheIRA

subsample.The

resultswithrespecttothemarginaltaxratecoefficientsaresensitive,however,tothe other variables includedinthe

equation. Eliminatingthecategoricalvariablesforhousehold income,forexample, reducesthemarginaltax

ratecoefficient

and

insome

specifications results ina negativecoefficientestimate.Thereis

some

evidence of anage-related patternintax-efficiency.Both

oftheestimated equationsshow

asubstantiallylargeragecoefficientsforthe 60-69year oldagegroupthanfor the50-59 yearoldgroup.

The

significance ofthesetwo

agecategoriesisthatthe taxpenaltyforwithdrawalsfrom

tax-deferredaccountsiseliminatedoncethehousehold reaches age

59

54,therebyreducingtheimportanceofprecautionarysavingconsiderations.

Households

over age60

aremore

likely tohave

tax-efficient allocationsthantheirslightlyyoungercounterparts.

We

experimented withexpandingthe specificationtoincludeaninteractionterm

between

themarginaltaxrateand

anindicatorvariableforhouseholds overtheageof60,butwe

couldnotreject the nullhypothesisthatthecoefficienton

thisvariablewas

equalto zero.Thereisonly

weak

evidence ofnetworth-related, or income-related, patternsinthe probabilityofholdingatax-efficient portfolio.

The

specificationinthefirstcolumn

suggeststhathouseholds withnetworth oflessthan$25,000are less likely to

make

tax-efficientchoicesthan otherhouseholdsare,but thedifferences acrossnetworthcategories arenotstatisticallysignificant. Similarproblemsariseininterpreting

the

income

coefficients.The

nexttwo columns

of Table 11,columns

threeandfour, reportregression equations inwhich

the19

shareof

non-TDA

assets infixedincome

securities.The

specificationincludes thesame

explanatoryvariablesastheprobit

models

reportedinthefirsttwo

columns:(2) DIFF,

=

p

+ 8*MTR,

+

I

a

j*AGE

1J+

I

yk*NETWORTH

lk+Et]

c*RISK,

c+

2

p

s*rNCOME

is+

£,.Once

again, theestimatedcoefficienton

themarginaltax ratevariableissensitive toourchoiceofestimationsample.

The

coefficientson

themarginaltaxratearenegativeinthemodels

forboththefull sampleand

theERA

subsample.The

coefficientisstatisticallysignificantly differentfrom

zeroforthesample withERA

holdings.

The

pointestimatefor this specification, -.412,impliesthataone percentagepoint increaseinahousehold's marginaltax rateleadstoa 0.4percent declineinthedifference

between

theshareoffixed-income

assets inthetaxableand

the tax-deferredaccount.Thereis

some

evidence ofalinkbetween

networth andthedifferenceinasset allocations.Highernetworth households appeartoholdahighershareoftheir

non-TDA

assets infixedincome

thanlowernetworthhouseholds. Thisfindingistruefor the

ERA-only

sampleaswellas forthebroadersample. Itislargelydriven

by

a smalleramount

of fixed-income holdinginthetax-deferredaccountsof highnetworthhouseholds. Thereisonce again

some

evidenceofa differenceinassetallocationpatterns forhouseholdsintheirfifties

and

sixties,witholderhouseholdsshowing

asmallerdifferentialbetween

theshareoffixedincome

assets intaxableandtax-deferredaccounts. Thereareno pronounced

patternsinthe assetallocationpatternsacross

income

groups,andthecoefficientson

some

oftheadjacent indicator variablesforincome

categoriesdiffersubstantially.

The

lasttwo columns

of Table 1 1 presentourlastempiricaltestof whethertax rates affect assetlocation.

The

dependentvariableintheseregressionmodels

isthepercentageofTDA

assets thatneedtobereallocatedinordertoreach a tax-efficientallocation.

The

specificationisotherwisethesame

as thatinequation(2).

Once

againthemarginaltaxratevariablehasmixed

effectsacrossspecifications.The

coefficientestimateispositive

when

we

estimate themodel

forthefullsample,andnegativewhen

we

estimateonthesample of

ERA

holders. Enneithercaseisthe coefficienton

themarginaltax ratevariable20

5. Conclusions

Thispaperpresentsevidence

on

assetallocationand

locationdecisionsforhouseholdswithsubstantial balancesinboththeirtaxableandtax-deferredaccounts. It

shows

that assetlocationisanimportantfinancialissueforasubstantialgroup ofU.S.households.

More

thanelevenmillionhouseholdsin1998

had

atleast$25,000inbothtaxableand

tax-deferredaccounts,and

atleast3.4millionhad

more

than$100,000investedineachtypeofaccount.

Many

households havechosenassetlocationstrategies thatallocateequityto theirtax-deferredaccount while theyareholdingfixed

income

investmentsintaxableaccount.A

broad range ofstudiesbothinacademicjournalsandin outlets that areread

by

financialservices professionals,suchasCharron (1999)and

Crain

and

Austin(1997), suggestthathouseholds canraise their after-taxretirementwealthby

holding highlytaxedassets in theirtaxdeferred account,

and

lightlytaxedassetsoutside. Datafrom

theSurvey ofConsumer

Financesneverthelesssuggestthattheequity shareoftax-deferredassetsisroughlyequaltotheequityshare

offinancial assetsoutsidethe

TDA.

The

costoftax inefficientbehaviormay

be modest,however,formany

households.

Our

calculationssuggestthatforroughlythreequartersofthehouseholdsthatappeartodeviatefrom

tax-efficientassetlocationstrategies,moving

lessthan$10,000inbonds

or stockswould

bringthem

toatax -efficient allocation.

The

limitedsizeofthisreallocationplacesanupperbound on

theforegoneretirementwealthassociatedwithcurrentassetlocation decisions.

We

havehad

limitedsuccessinexplaining theassetlocation patternsthatwe

observeincross-sectionalsurveydata. In the 1998 Survey of

Consumer

Finances,forexample,we

findatbest aweak

relationship

between

ahousehold'smarginalincome

taxrateandthetax-efficiencyofitsportfolio allocation.Explainingthese patternsisclearlyachallengefor futurework,

which

shouldfocusbothon

theinformationthathouseholdsreceiveaboutassetallocationdecisionswithin tax-deferred accounts,

and

on

householdawarenessoftheafter-taxreturnconsequences ofdifferentassetlocationchoices.

The

assetlocationdecisionispartofabroader householddecisionaboutportfolio allocation.Findingthat

many

households pursuetax-inefficient assetlocationstrategies raisesquestionsaboutother21

one suchdecision:

consumer

borrowing. Datafrom

the 1998SCF

suggestthat44

percentof U.S. householdshaveoutstandingcreditcard balances. Moreover, 1 1.5percenthaveacreditcardbalance ofat least$5000,

and

more

than 18 percenthavemore

than$2500

inoutstanding balances. Since 1986,interestpayments on

consumer

debthavenotbeendeductiblefrom

adjustedgrossincome

forthepurposeofcomputing

taxableincome. Interest

on

mortgagedebt,however, remainsdeductibleforincome

taxpurposes.The

taxdeductioncreatesastrong incentiveforhouseholdsto

borrow

throughhome

equitycredit linesratherthanon

creditcards

when

theycan.Maki

(1996)and

Stango (1999)suggest a declineinbothcreditcarddebtand

inautoloan financingafter

TRA86,

along withanincreaseinmortgage

borrowing.Inspiteofthetaxincentives,thereappeartobeasignificantminorityof households withcreditcard

balances

who

couldgeneratesubstantialtax savingsby

increasingtheiruseof mortgagedebt.Our

preliminary estimates suggestthat

among

the 18 percentof households withat least$2500

inoutstandingconsumer

debt,5.4percent,orjustunderonethirdofthegroup, haveatleast$50,000inself-reportedhousingequity. Nearly one seventh ofthisgroup, or2.3percentoftheaggregate population,hasatleast

$100,000inhousingequity. Itispossiblethatthetransactionscostsassociatedwithestablishinga

home

equitylineoutweighthe taxsavingfor

some

households,particularlythosewho

do

not itemizeand

who

do

notexpecttomaintaintheircreditcardbalanceforverylong. Nevertheless,it

seems

thatmany

ofthesame

issues that arise inexplainingapparentlytax-inefficient assetlocationdecisionsalso arisewithrespectto

consumer

borrowingdecisions.Work

iscurrentlyunderway on

these,and

otherrelatedhouseholdfinancialREFERENCES

Amromin,

Gene

(2002), "PortfolioAllocationChoicesinTaxable and

Tax-Deferred Accounts:An

Empirical Testof

Tax

Efficiency,"mimeo,

UniversityofChicago Department

ofEconomics.

Barber,

Brad

M.

and

TerranceOdean

(forthcoming), "Are Individual InvestorsTax

Savvy?

Asset LocationEvidence

from

Retailand

DiscountBrokerage

Accounts."Journalof PublicEconomics

.Bodie, Zvi

and Dwight

B.Crane

(1997), "Personal Investing:Advice, Theory,and

Evidence," Financial AnalystsJournal 53,Number

6(November/December),

13-23.Charron,TerryS.(1999), "Tax-Efficient Investing for

Tax

-Deferredand Taxable

Accounts," Journal of Private PortfolioManagement

(Fall),31-37.Crain,TerryL.

and

JeffreyR. Austin(1997),"An

AnalysisoftheTradeoffBetween

Tax

Deferred EarningsinIRAs

and

Preferential CapitalGains," Financial ServicesReview

6(4),227-242.Dammon,

Robert,ChesterSpatt,and Harold

Zhang

(2002)."Optimal

Asset Locationand

Allocationwith Taxableand

Tax

-DeferredInvesting,"Mimeo,

Carnegie-Mellon

University.Huang,

Jennifer (2001). "TaxableorTax

DeferredAccount?

PortfolioDecisions with Multiple Investment Goals."Mimeo,

MIT

SloanSchool ofManagement.

Kennickell,ArthurB.,

Martha

Starr-McCluer,and

Brian Surette.2000."Changes

inU.S.Family

Financesatthe

End

ofthe 1990s: Resultsfrom

the1998 Survey

ofConsumer

Finances." Federal ReserveBulletin (January).Maki,

Dean

(1996), "Portfolio Shufflingand

Tax

Reform,"

NationalTax

Journal 49,317-329.Poterba,

James

(2002). "Valuing AssetsinRetirementSaving Accounts,"mimeo,

MIT

Economics

Department.Poterba,James,

John

Shoven,and

Clemens

Sialm

(2001). "Asset Location forRetirementSavers,"inW.

Gale,J. Shoven,

and

M.

Warshawsky,

eds.,PrivatePensionsand

PublicPolicies(Washington:Brookings

Institution).Poterba,James,Steven

Vend, and David

Wise

(2001)."The

TransitiontoPersonalAccounts and

IncreasingRetirement Weaith:

Macro

and

Micro

Evidence,"NBER

Working

Paper 8610.Samwick, Andrew, and James

Poterba(forthcoming). "Taxationand Household

PortfolioComposition:Evidence from

Tax

Reforms

inthe 1980sand

1990s." Journalof PublicEconomics

.Shoven,

John

B. (1999)."The

Locationand

Allocationof AssetsinPensionand

Conventional Savings Accounts,"NBER

Working

Paper

7007.Shoven,

John

B.and

Clemens

Sialm(forthcoming). "Asset LocationinTax-Deferredand

Conventional Savings Accounts,"JournalofPublicEconomics.

Stango,Victor(1999).

"The

Tax Reform

Act

of1986

and

theComposition

ofConsumer

Debt." NationalTax

Journal52, 717-739.Table 1: Self-DirectedTax-Deferred Assetsasa PercentofTotal Financial Assets

Year

IRA

DC

pension Total1985

3.1%

5.5%

8.6%

1990 5.3 6.1 11.4

1995 6.9 7.9 14.8

1998 7.9 8.4 16.3

2001 8.5 8.3 16.8

Source:

Flow

of Funds,Z.l release,TablesL.10

and

L.l19.c. Total financial assetswere

$8.0trillionin 1985, $12.3trillionin1990, $18.6 trillionin1995, $27.2 trillionin1998,

and

$28.3trillionin2001.

Table2: Percentageof

Households

withTax-Deferred Accounts

or FinancialAssetsOutside Tax-DeferredAccounts,1989-1998

Year

Tax

Deferred AssetsTaxable

Financial AssetsOutsideTDA

Either

Taxable

orTax

Deferred Assets1989 30.7 45.6 55.1

1992 33.8 44.5 55.4

1995 40.7 43.1 58.4

1998

45.7%

46.8%

63.0%

Source: Tabulations

from

SurveysofConsumer

Finances. Financial assets outside the tax -deferred account includestocks, equitymutual funds,certificatesof

deposit,savings bonds,and

other taxable bonds.Tax-exempt bonds

arenot includedinthesetoffinancial assetsoutside theTDA.

In 1989,6.5 percentof

households reportedsome

holdingsoftax-exempt bonds;thisfractionwas

stableacross surveys, rising to 6.6 percentin 1998. Virtuallyallhouseholdsowning

tax-exemptbonds

alsoheld taxablebonds.The number

of householdsinthefourSurveys ofConsumer

Financesare93

million (1989),95.9million (1992),99

million (1995),and

102.6million (1998).Table3:

Households

withSignificantHoldings

ofBoth

Taxableand

Tax-DeferredFinancial AssetsValue

ofTax-Deferred

Account

Financial Assetsin

Taxable

Account

>0

>10K

>25K

>50K

>100K

1989>0

-A7

•* 11.2 8.0 5.9 3.6>10K

13.1 8.7-: v;cj\, -;'.-6.8 5.1 3.2>25K

8.0 5.9 4.8 3.8 2.4>50K

4.4 3.6 2.9 '2.6 1.8>100K

2.0 1.6 1.4 1.3 1-0 1998>0

30.3 18.6 14.0 10.9 6.6>10K

22.9 15.6 12.3 9.6 6.0>25K

17.2 12.7 10.3 -; 8.2 5.4>50K

11.9 9.2 7.6 6.2 - 4.3>100K

6.9 5.7 5.0 4.1 3.2Notes:

Each

entryshows

thetotalnumber

of

households(inmillions)withthespecifiedmix

ofassets in24

Table4: ShareofFinancialAssets

Held

inTax

DeferredAccounts, 1998Net

Worth

or FinancialAssetCriterion

Millionsof

Households

withTDA

&

Non-TDA

Assets

TDA

Assetsas aPercentageof

Total FinancialAssetsFor

Households

withBoth

TDA

and

Non-TDA

AssetsPercentile

Mean

10lh25

thMedian

75th90

th AllHouseholds

30.310.6%

28.0%

57.1%

85.6%

97.3%

55.9%

Net

Worth

>$100K

22.6 9.1 24.8 54.1 83.4 96.3 53.8Net

Worth >

S250K

14.3 6.8 19.6 47.9 77.9 94.5 48.9Net

Worth

>$1M

3.4 4.1 13.4 34.7 68.2 88.2 40.7 FinancialAssets>

$100K

15.3 7.3 20.9 49.2 79.0 94.7 49.8 FinancialAssets>

$250K

7.4 5.7 15.3 42.3 69.4 93.3 44.2 FinancialAssets>

$1M

1.6 3.0 7.9 25.0 51.5 85.1 33.3 Source: Authors'tabulationsusing1998Survey

ofConsumer

Finances. Seetextfor furtherdetails.Table5: Asset AllocationinTaxable and

Tax-Deferred

Accounts,1989-1998

1989

1992

19951998

AllFinancial AssetsEquityasPercentage

of

TotalFinancialAssets :. - ?•140$%':-

:47,8%

-DO.3/0 „ 69.7%:>

Tax

Exempt Bonds

asPercentageofTotal FinancialAssets 13.5 12.0 9.6 6.2 PercentofHouseholds

with Equity orFixed-Income

Assets 54.0 54.5 56.7 62.6 PercentofHouseholds

withAny

Equity 27.3 32.4 36.6 45.8 PercentofHouseholds

withAny

Fixed-Income

Assets 49.2 48.6 48.4 50.5 Financial AssetsHeld

inTDA

EquityasPercentage

of

TDA

FinancialAssets 33.6 46.8 54.467*sBHH

PercentofHouseholds

with EquityorFixed-Income

Assets 29.1 32.2 38.3 45.0 PercentofHouseholds

withAny

Equity 13.3 19.9 24.7 34.5 PercentofHouseholds

withAny

Fixed-Income

Assets 23.2 24.3 25.0 26.1 FinancialAssetsHeld

inOutsideTDA

EquityasPercentage