Digital Health Communication and Global

Public Influence: A Study of the Ebola Epidemic

The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available.

Please share

how this access benefits you. Your story matters.

Citation

Roberts, Hal et al. "Digital Health Communication and Global

Public Influence: A Study of the Ebola Epidemic." Journal of Health

Communication 22, sup1 (August 2017): 51-58 © 2017 The Authors

As Published

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1209598

Publisher

Informa UK Limited

Version

Final published version

Citable link

https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/122025

Terms of Use

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=uhcm20

Journal of Health Communication

International Perspectives

ISSN: 1081-0730 (Print) 1087-0415 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uhcm20

Digital Health Communication and Global Public

Influence: A Study of the Ebola Epidemic

Hal Roberts, Brittany Seymour, Sands Alden Fish II, Emily Robinson & Ethan

Zuckerman

To cite this article: Hal Roberts, Brittany Seymour, Sands Alden Fish II, Emily Robinson & Ethan Zuckerman (2017) Digital Health Communication and Global Public Influence: A Study of the Ebola Epidemic, Journal of Health Communication, 22:sup1, 51-58, DOI: 10.1080/10810730.2016.1209598

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1209598

Published with license by Taylor & Francis© 2017 Hal Roberts, Brittany Seymour, Sands Alden Fish II, Emily Robinson, and Ethan Zuckerman.

Published online: 30 Aug 2017.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 1690

View Crossmark data

Digital Health Communication and Global Public Influence: A

Study of the Ebola Epidemic

HAL ROBERTS1, BRITTANY SEYMOUR2, SANDS ALDEN FISH II1, EMILY ROBINSON3, and ETHAN ZUCKERMAN4 1Berkman Center for Internet and Society, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

2Department of Oral Health Policy and Epidemiology, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, USA 3Department of International Education Policy, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA 4Center for Civic Media, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

Scientists and health communication professionals expressed frustration over the relationship between misinformation circulating on the Internet and global public perceptions of and responses to the Ebola epidemic originating in West Africa. Using the big data platform Media Cloud, we analyzed all English-language stories about keyword“Ebola” published from 1 July 2014 to 17 November 2014 from the media sets U.S. Mainstream Media, U.S. Regional Media, U.S. Political Blogs, U.S. Popular Blogs, Europe Media Monitor, and Global Voices to understand how social network theory and models of the networked global public may have contributed to health communication efforts. 109,400 stories met our inclusion criteria. The CDC and WHO were the two media sources with the most inlinks (hyperlinks directed to their sites). Twitter was fourth Significantly more public engagement on social media globally was directed toward stories about risks of U. S. domestic Ebola infections than toward stories focused on Ebola infections in West Africa or on science-based information. Corresponding public sentiments about Ebola were reflected in the policy responses of the international community, including violations of the International Health Regulations and the treatment of potentially exposed individuals. The digitally networked global public may have influenced the discourse, sentiment, and response to the Ebola epidemic.

Due to rapid Internet advancements and emerging media technol-ogies, the last two decades have been marked by the rise of a highly connected and digitally empowered general public. In contrast to most of the 20th century, today’s public sphere is a complex global network of many voices fostered by the growing variety of modes of (mostly digital) communication both in publishing content and in determining which content attracts attention. In this networked public sphere, attention continues to follow the traditional power law: a few stories and sources within any given issue usually attract the vast majority of the attention (Barabási,1999). Some argue that the continued operation of this power law indicates that only a few elite actors will have meaningful influence on public sentiment about a given topic (Barabási,1999; Hindman,2008). Others argue that the networked public sphere can act as an“attention back-bone,” directly and indirectly gathering attention from a diverse set

of actors and modes of publishing, and ultimately influencing whose voices are heard and shared online (Benkler,2006).

Scientists and health professionals expressed tremendous frustration over the relationship between misinformation cir-culating on the Internet and the global public’s perceptions and responses during the Ebola epidemic that originated in West Africa (Chandler et al., 2015; The Lancet, 2014; Merino, 2014; Mitman, 2014; Oyeyemi, Gabarron, & Wynn,

2014; Ratzan & Moritsugu, 2014; Trad, Fisher, & Tambyah,

2014). Their interpretation of the situation was often unidir-ectional: misinformation shaped public sentiment. Thus, cor-responding solutions were frequently too simplistic, aimed at correcting the misinformation in an effort to redirect public sentiment globally, an ultimately ineffective approach (Chandler et al., 2015). New network theory research suggests the true relationship between misinformation and public per-ception is much more complex: the networked public sphere is no longer merely a target audience but is now a major contributor to the online health communication arena, shaping the conversations with individual sentiments and social engagements. In this paper, we explore how models of the networked public sphere online may apply to modern health communication and the Ebola epidemic. We analyze the com-plex interplay between media, social media, and the broader international community’s response to the epidemic; compli-cations magnified by modern media modalities likely nega-tively influenced policy responses, diverted attention and resources from where they were most needed, and may have © 2017 Hal Roberts, Brittany Seymour, Sands Alden Fish II, Emily

Robinson, and Ethan Zuckerman. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which per-mits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Address correspondence to Emily Robinson, Department of International Education Policy, Harvard Graduate School of Education, 13 Appian Way, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA. E-mail:emily_robinson@mail.harvard.edu

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online atwww.tandfonline.com/UHCM.

Journal of Health Communication, 22: 51–58, 2017 Published with license by Taylor & Francis ISSN: 1081-0730 print/1087-0415 online DOI: 10.1080/10810730.2016.1209598

played a role in violations of the International Health Regulations. This study aims to provide insight into how social network theory applies to modern health communica-tion management moving forward.

Methods

For this study, we used Media Cloud, a big data platform for the quantitative study of online media. Media Cloud provides a searchable archive of over 250 million stories from 50,000 media sources over more than 5 years, along with tools to analyze that archive. It has been used successfully for the development of previous studies designed to elucidate the opera-tion of the networked public sphere and online influence (Benkler, Roberts, Faris, Solow-Niederman, & Etling, 2013; Faris, Roberts, Etling, Othman, & Benkler, 2015; Graeff, Stempeck, & Zuckerman, 2014). We analyzed a set of web pages located by Media Cloud, as described below, to determine story identification and intensity of coverage, and performed link analysis, content clustering, and social media analysis to determine the most influential media sources and stories during our designated time period. The combination of these analyses would provide us with insights into the networked public sphere’s influence over online media engagement about Ebola. Story Identification and Intensity of Coverage

We searched using the keyword “Ebola” for all English lan-guage stories published from 1 July 2014 to 17 November 2014 in the following media sets: U.S. Mainstream Media, U.S. Regional Media, U.S. Political Blogs, U.S. Popular Blogs, Europe Media Monitor, and Global Voices. The date range corresponded to the period of most intense media coverage of Ebola, as indicated by preliminary Media Cloud searches and thus provided us with the richest data set.

For each story discovered, we downloaded the HTML for that story. We extracted the substantive text of each story by eliminating advertisement, navigational, and other surrounding content and parsed the text into individual sentences. We then counted the number of sentences published each day to track intensity of cover-age over time. We supplemented this set of stories by downloading each link in each story and adding to the set any more stories that included the keyword“Ebola” not yet included. We repeated this iterative spidering process 15 times, until very few new stories had been found and we determined we had reached saturation.

Link Analysis

As a metric of influence for media sources and stories, we used link analysis to report the number of incoming hyperlinks (inlinks) directed to a given story from a media source other than the publisher. This follows the approach used for social network analysis in previous Media Cloud-based studies (Adamic & Glance,2005; Hargittai, Gallo, & Kane, 2007). In the process of spidering the hyperlinks of every story in the set, we recorded data about which of those stories linked to other stories in the set. We included only hyperlinks within the sub-stantive text of each story. To determine influence within the link economy, we counted the number of inlinks for each story

and for each media source. We counted as inlinks any links coming from media sources other than the stories’ own media source. This approach is based on the commonly accepted assumption that a link from one site to another indicates that the linked site has exerted some influence over the linking site. This behavior does not necessarily imply agreement but has been shown to indicate substantive engagement, a measure of influence within a network (Hargittai et al., 2007).

Content Clustering

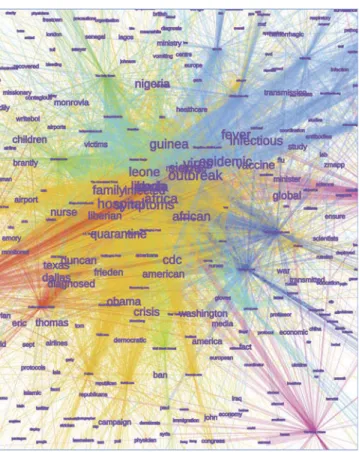

We used content clustering to identify communities of media sources that used similar language and to determine how specific language maps onto those communities. For each of the 50 media sources with the most inlinks, and thus determined to be the most influential, we identified the 100 words most commonly used by each media source in its Ebola stories, for a total of 5,000 words. To generate this list of the top 100 words for each media source, we first stemmed each of the words and then omitted any of 4,362 English stopwords. We then generated a bipartite graph with both the media sources and their most common words as nodes and added an edge between each media source and each word among the top 100 words for the given media source. For example, an edge was created between the WHO node and the “epidemic” node because “epi-demic” was among the 100 words most commonly used by WHO. Finally, we drew the map using the force-based layout algorithm Force Atlas 2 (Blondel, Guillaume, Lambiotte, & Lefebvre,2008) to determine the position of the nodes and the Louvain community detection algorithm to determine the color of the nodes. Sources that used common language were clustered into color-coded commu-nities within the visualization map.

Social Media Analysis

Because link analysis only tells us which sources and stories are receiving links and not who is reading or sharing those links, we used two different social media metrics to better understand the sources with which the public (as opposed to publishers) was engaging: Uniform resource locators (URLs), otherwise known as Internet addresses, shared on Twitter and clicks on Bitly links (shortened URL links found on social media sites that redirect users to original media sources). For both Twitter and Bitly data, we generated a list of common variants for the URL of each story, as well as a list of URLs found by the spider (an automated web crawler) to redirect to any of those URLs. For Twitter, we used the company’s application program interface (API) to count the num-ber of times any of those URL variants were included in a tweet. This Twitter metric does not directly count the number of people who read the story, but it does indicate social media interest in a story or topic. For Bitly, we used the company’s API to count the number of times any web user clicked on a Bitly link that resolved to any of the story’s URL variants.

Results

Story Identification and Coverage Intensity

Our initial Media Cloud search identified 83,972 stories. The iterative spidering process identified an additional 25,428

stories, for a total set of 109,400 Ebola-related stories. Over the course of October, Ebola was by far the most prevalent news story in U.S. online media. In fact, U.S. media covered Ebola more intensely than it covered any topic for any month since October 2010 (the earliest date for which Media Cloud data is available), with the sole exception of coverage of the final month of the 2012 U.S. presidential election.

Three distinct peaks of Ebola coverage occurred around July 27, September 28, and 15 October 2014 (Figure 1). On July 27, reports broke of the first infections of American doctors in Liberia. On September 30, media widely reported the infection of Thomas Duncan in Texas as the first infection on U.S. soil. On October 12, Ebola coverage intensified with the first infec-tion of a health care worker in the United States. After October 12, a series of other U.S. infection-related events led to contin-uous coverage that gradually lessened in intensity over time. Link Analysis

Table 1lists the 10 media sources andTable 2lists the 10 stories with the most inlinks. Science- and medical-related actors and stories received the most inlinks within the network of coverage. The CDC and WHO were the two most inlinked media sources, followed by New York Times and Twitter. The rest of the 10 most inlinked sources were all U.S. mainstream media sites, with the exception of Reuters, a UK media company with a large U.S. footprint. Seven of the top 10 stories by inlinks were WHO or CDC stories. The Twitter “#ebola” hashtag itself was the fourth most inlinked story, an Ebola category page for ABC News was seventh, and a Texas infection story was tenth.

Content Clustering

Figures 2 and3 are two different views of the map resulting from the content clustering. The map includes five commu-nities, which are described in Table 3: (1) U.S./Politics (yel-low); (2) U.S./Texas (red); (3) Human Suffering (bluegreens); (4) Science/Medical (violet); and (5) Governance (indigo). Overall, the U.S./Politics community constitutes the core of the networked map, with the Science/Medical sources mostly segregated into the top right corner. The U.S./Politics cluster consists overwhelmingly of major U.S. mainstream media (USA Today, LA Times, New York Times, etc.). The Science/ Medical cluster consists mostly of national and international health agencies (WHO, NIH) and science-focused publica-tions (Nature). The CDC is located among the Science/ Medical sources by the layout algorithm but placed in the U.S./Politics community on the map, suggesting use of lan-guage from both categories. This map shows that sources focusing on language and phrasing oriented toward science

and medicine were largely separate from those focusing on language oriented toward U.S. domestic concerns and politics. Social Media Analysis

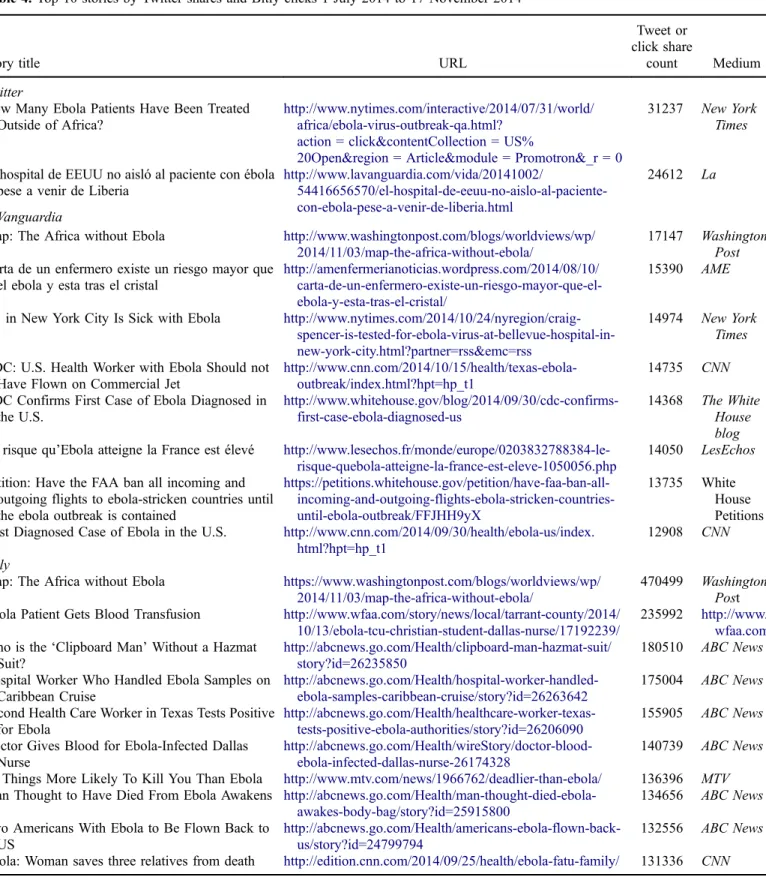

Six of the top 10 stories by Twitter shares are from the U.S./ Politics content cluster, while 2 are cluster outliers and 2 are White House pages. Only 1 WHO or CDC story appears among the top 20 stories by Twitter shares. The list of media sources with the most Bitly clicks across social media consists solely of U.S./Politics sources, led by CNN, ABC News, and Washington Post.

Table 4 lists the combined top 10 stories by Twitter shares and Bitly clicks. Twelve out of eighteen stories were focused directly on risks of domestic infection in the United States or Europe. Three stories were pieces debunking various aspects of that domestic risk. Two stories focused on emotional personal narratives of individuals in West Africa. The remaining story was a page of New York Times visualizations about Ebola, split roughly evenly between African- and U.S.-focused coverage.

Discussion

As of 23 September 2015, there had been 4 confirmed cases of Ebola in the United States and 1 reported death (World Health Organization, 2015a), compared with 28,295 Ebola cases reported to WHO from Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, and 11,295 reported deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). However, our results show that vastly more public attention internationally within social media was directed toward stories about risks of U.S. domestic Ebola infections than toward stories focused on confirmed Ebola infections in the impacted African countries. For example, this imbalance existed in a media controversy that dominated the U.S. news cycle more than any other topic in the past 4 years other than the last month of the 2012 U.S. presidential election. As the largest donor globally during the crisis, making up more than 50% of total donations, the United States became a leader in thought and in action (Finanacial Tracking Service, 2015).

To understand media coverage in the networked public sphere globally, we must look beyond simple metrics like num-bers of web page views for individual web pages or numnum-bers of followers on Twitter for particular accounts. Instead, we must grapple with the networked interplay of publishers, content, link economy, and social media engagement. Our multimodal analy-sis provided several key findings. Challenges in communication included the immense engagement in U.S. and international online media focused mostly on risk of domestic infection in countries where true risk was low. Positive outcomes included the fact that the flood of stories about local U.S. cases also Figure 1. Coverage intensity (number of online stories published) of the Ebola epidemic through online media from 1 July 2014 to 17 November 2014. (Source: Authors’ analysis of coverage intensity for keyword “Ebola” 2015.)

resulted in many inlinks to expert sources such as the CDC and WHO that promoted information consistent with the best avail-able public health knowledge about Ebola. Additionally, atten-tion was also paid to stories refuting misinformaatten-tion. Notably, personal stories about African suffering, appealing to human emotion and compassion, during the Ebola outbreak were among the most highly engaged.

Although health and infectious disease authorities were clearly influential, our findings support our hypothesis that the digitally connected global public was a critical influencer within the network. In fact, our results provide evidence that health authorities were more influential among other media publishers than among the broader public, resulting in the prevalence of inlinks to public health sites but the scarcity of attention paid to those sites in social media (Twitter shares and Bitly clicks). As a result, international health authorities

were largely unsuccessful in directing the narrative about the Ebola outbreak and response among the global public online.

A striking example of this public influence was the sharp contrast between particular international responses and the recommendations of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and other prominent health authorities. MSF advised against forced quarantines and travel bans as methods for controlling the epidemic because these measures “breed fear and unrest” and interfere with the international community’s ability to respond (Doctors Without Borders, 2015). These sentiments were echoed by the scientific and health community through-out the epidemic (Asgary, Pavlin, Ripp, Reithinger, & Polyak, 2015; Bogoch et al., 2015; Drazen et al., 2014; Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2014; McCarthy, 2014a, 2014b; Ratzan & Moritsugu, 2014; Rosenbaum, 2015). In its July Table 1. Top 10 media sources online ranked by quantity of inlinks from 1 July 2014 to 17 November 2014

Rank Media ID Name Media type Stories Inlinks Outlinks Clicks Referrers 1 19740 cdc.gov Government 347 2140 112 140268 1947 2 19765 who.int Ind. Group 293 1963 1 9409 584 3 1 New York Times General News 1111 1788 681 514343 12046 4 18346 twitter.com User Gen. 927 1390 0 2612 184 5 1149 MSNBC General News 1270 1127 575 414016 7449 6 2 Washington Post General News 792 1116 34 2082951 11399 7 1095 CNN General News 1655 1042 781 5489934 18770 8 25499 nbcnews.com General News 298 883 445 116294 2082 9 4442 Reuters News General News 2266 865 21 119975 5358 10 669 ABC News General News 686 681 3 553158 2605

Source: Authors’ analysis of inlinks, 2015.

Table 2. Top 10 media stories online ranked by quantity of inlinks from 1 July 2014 to 17 November 2014

Rank Story ID Title Publish date Medium Inlinks Outlinks Clicks Referrers 1 280648117 WHO l Ebola virus disease undateable who.int 473 0 445 21 2 280653575 Ebola Virus Disease Information for Clinicians in

U.S. Healthcare Settings

undateable cdc.gov 202 0 1208 33 3 280648383 Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever l CDC undateable cdc.gov 181 0 265 23 4 280659444 Tweets about #ebola hashtag on Twitter undateable twitter.com 178 0 1 1 5 280688375 WHO l Ebola virus disease update—West Africa 2014-08-04

12:00:00

who.int 159 0 81 3 6 280653545 WHO l Ebola virus disease, West Africa—update 2014-07-27

12:00:00

who.int 148 0 0 0 7 280648306 Ebola News, Photos and Videos—ABC News undateable ABC News 134 0 3 2 8 294156836 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa l Ebola

Hemorrhagic Fever

undateable cdc.gov 98 0 347 26 9 280648044 Signs and Symptoms l Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever l

CDC

undateable cdc.gov 87 0 50 5 10 286399456 UTA grad isolated at New Jersey hospital as part

of Ebola quarantine 2014-10-25 17:00:32 Dallas Morning News 87 0 8139 287

Source: Authors’ analysis of inlinks, 2015.

2015 Report of the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel, the World Health Organization concluded, “the global commu-nity does not take seriously its obligations under the International Health Regulations (2005)—a legally binding document.” Close to one-quarter of its member states were in violation of the IHR by enacting travel bans and other restrictive measures that negatively impacted travel and aid to the affected countries (World Health Organization,2015b). This may explain why the terms“quarantine” and “ban” were not found within the scientific language cluster in our map, but were found within the U.S./Politics cluster, reflecting the

division between the medical/scientific and the political nar-ratives responding to public fear and sentiment.

While scientific experts avoided discussion of bans and quar-antines, those topics were widely discussed in the U.S./Politics cluster, and policymakers acted in accord with those discussions. The governors of New York and New Jersey instituted strict mandatory quarantines of all travelers who had been in direct contact with infected patients, regardless of whether or not they Figure 2. Network map of the five communities identified by the

content clustering analysis that shared common language and phras-ing durphras-ing the Ebola epidemic, with example sources labeled. (Source: Authors’ content clustering analysis of communities and keywords, 2015.)

Figure 3. Network map of the five communities identified by the content clustering analysis that shared common language and phrasing during the Ebola epidemic, displaying examples of the most common words used in published text. (Source: Authors’ content clustering analysis of communities and key-words, 2015.)

Table 3. Summary of color-coded communities within the visualization maps shown inFigures 2and3

Community category Color Example keys terms Example sources

U.S./Politics Yellow “Obama,” “American,” “Crisis,” “Democratic,” “ban” Fox News New York Times Huffington Post

U.S./Texas Red “Dallas,” “Eric,” “Texas,” “Duncan” CBS Local Dallas Morning News Human Suffering Bluegreens “missionary,” “victims,” “bodily,” “bleeding,” “recovered” Yahoo InfoWars.com

Medical/Clinical/ Scientific

Purple “transmission,” “antibodies,” “immune,” “Zmapp drug,”

“pathogens” Nature New England Journal ofMedicine Governance Pink “agenda,” “partnership,” “infrastructure” White House Canadian Government

Source: Authors’ content clustering analysis of communities and keywords, 2015.

Table 4. Top 10 stories by Twitter shares and Bitly clicks 1 July 2014 to 17 November 2014

Story title URL

Tweet or click share

count Medium Twitter

How Many Ebola Patients Have Been Treated Outside of Africa?

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/07/31/world/ africa/ebola-virus-outbreak-qa.html?

action = click&contentCollection = US%

20Open®ion = Article&module = Promotron&_r = 0

31237 New York Times

El hospital de EEUU no aisló al paciente con ébola pese a venir de Liberia

http://www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20141002/

54416656570/el-hospital-de-eeuu-no-aislo-al-paciente-con-ebola-pese-a-venir-de-liberia.html

24612 La

Vanguardia

Map: The Africa without Ebola http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/wp/ 2014/11/03/map-the-africa-without-ebola/

17147 Washington Post Carta de un enfermero existe un riesgo mayor que

el ebola y esta tras el cristal

http://amenfermerianoticias.wordpress.com/2014/08/10/ carta-de-un-enfermero-existe-un-riesgo-mayor-que-el-ebola-y-esta-tras-el-cristal/

15390 AME

Dr. in New York City Is Sick with Ebola http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/24/nyregion/craig- spencer-is-tested-for-ebola-virus-at-bellevue-hospital-in-new-york-city.html?partner=rss&emc=rss

14974 New York Times CDC: U.S. Health Worker with Ebola Should not

Have Flown on Commercial Jet

http://www.cnn.com/2014/10/15/health/texas-ebola-outbreak/index.html?hpt=hp_t1

14735 CNN CDC Confirms First Case of Ebola Diagnosed in

the U.S. http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2014/09/30/cdc-confirms-first-case-ebola-diagnosed-us 14368 The White House blog Le risque qu’Ebola atteigne la France est élevé

http://www.lesechos.fr/monde/europe/0203832788384-le-risque-quebola-atteigne-la-france-est-eleve-1050056.php

14050 LesEchos Petition: Have the FAA ban all incoming and

outgoing flights to ebola-stricken countries until the ebola outbreak is contained

https://petitions.whitehouse.gov/petition/have-faa-ban-all- incoming-and-outgoing-flights-ebola-stricken-countries-until-ebola-outbreak/FFJHH9yX 13735 White House Petitions First Diagnosed Case of Ebola in the U.S. http://www.cnn.com/2014/09/30/health/ebola-us/index.

html?hpt=hp_t1

12908 CNN Bitly

Map: The Africa without Ebola https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/wp/ 2014/11/03/map-the-africa-without-ebola/

470499 Washington Post Ebola Patient Gets Blood Transfusion http://www.wfaa.com/story/news/local/tarrant-county/2014/

10/13/ebola-tcu-christian-student-dallas-nurse/17192239/

235992 http://www. wfaa.com

Who is the‘Clipboard Man’ Without a Hazmat Suit?

http://abcnews.go.com/Health/clipboard-man-hazmat-suit/ story?id=26235850

180510 ABC News Hospital Worker Who Handled Ebola Samples on

Caribbean Cruise

http://abcnews.go.com/Health/hospital-worker-handled-ebola-samples-caribbean-cruise/story?id=26263642

175004 ABC News Second Health Care Worker in Texas Tests Positive

for Ebola

http://abcnews.go.com/Health/healthcare-worker-texas-tests-positive-ebola-authorities/story?id=26206090

155905 ABC News Doctor Gives Blood for Ebola-Infected Dallas

Nurse

http://abcnews.go.com/Health/wireStory/doctor-blood-ebola-infected-dallas-nurse-26174328

140739 ABC News 99 Things More Likely To Kill You Than Ebola http://www.mtv.com/news/1966762/deadlier-than-ebola/ 136396 MTV Man Thought to Have Died From Ebola Awakens

http://abcnews.go.com/Health/man-thought-died-ebola-awakes-body-bag/story?id=25915800

134656 ABC News Two Americans With Ebola to Be Flown Back to

US

http://abcnews.go.com/Health/americans-ebola-flown-back-us/story?id=24799794

132556 ABC News Ebola: Woman saves three relatives from death http://edition.cnn.com/2014/09/25/health/ebola-fatu-family/ 131336 CNN

Source: Authors’ analysis of Twitter shares and Bitly clicks for keyword “Ebola,” 2015.

were showing symptoms (Santora,2014). Schools in Ohio and Texas closed due to fears that faculty and students traveled on the same plane as a healthcare worker who later developed a low-grade fever after caring for an Ebola patient in Dallas (Bever, 2014). And a New Jersey school requested that two children who moved from Rwanda, a country with zero cases of Ebola, remain home from school for a “21 day waiting period.” The school later issued an apology (Milo,2014).

The digitally networked global public in this case study acted not so much as a set of diverse independent actors publishing or passively consuming content. Instead, we see a complex set of interactions between diverse interests and the actions of international health institutions, largely main-stream media content publishers, and consumer attention expressed through social media. These findings suggest that we should view the general public not merely as a target audience for broadcast information, but rather as a contribut-ing actor in the online global public health communication arena. Individuals from around the world shaped the con-versations with their social engagements within the network by sharing stories of interest and by clicking on stories shared by others.

Health communication strategies may need to include not only traditional broadcast diffusion tactics but also social diffusion approaches that account for the networked public sphere and consequently the values of influencers within online networks. Health knowledge and information is born from a rigid, evidence-based process. Yet, once this informa-tion is published online, the networked public sphere deter-mines what is relevant, credible, and worthy of online engagement in a process independent of the strength of scientific arguments.

Social health communication strategies could include innovative ways of interacting with the influencers within online social networks in order to amplify positive messaging supported by science and evidence. These strategies, grounded in network science, might be developed through a combination of testing various sources (open-access versus peer-reviewed subscription publications), content vehicles (info graphics, text-based, videos, or interactive activities), and social message testing (fact-based narrative, anecdotes and personal stories, or resources like fact sheets). Learning from this study, for example, global health agencies might model their content on successful debunking stories or on the individual narratives of African actors that gathered interna-tional attention despite running counter to fear-driven narra-tives of possible U.S. outbreaks.

Conclusion

Our study supports our hypothesis that the digitally net-worked global public online likely influenced the discourse, sentiment, and response to the Ebola epidemic. Small-scale incidents, such as the relatively limited number of cases in the United States and other developed countries, were ampli-fied within the network and became one of the most highly visible aspects of the entire online conversation. The most common language used within the U.S./Politics network did

not correlate with the response recommendations or report-ing by health authorities and scientific experts. The network thus provided a platform for messages that reflected the fears and concerns of the networked public rather those of health officials. Our results warrant further research into how the networked public sphere is affecting current health commu-nication successes (or failures) and whether innovative, socially oriented strategies are needed. We believe that sys-tematic analysis of digital networks, which could include statistical testing for correlation between network engage-ment and specific social communication strategies, will broaden the scientific sphere of influence in order to compel positive, evidence-based public health communication approaches within the networked public with success.

Acknowledgment

We wish to acknowledge Megan Murray, MD, MPH, ScD of the Harvard Global Health Research Core for her support and insights into the development of this paper.

References

Adamic, L. A., & Glance, N. (2005). The political blogosphere and the 2004 U.S. election. Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Link Discovery - LinkKDD‘05, 1–16. doi:10.1145/1134271.1134277 Asgary, R., Pavlin, J. A., Ripp, J. A., Reithinger, R., & Polyak, C. S. (2015,

February). Ebola policies that hinder epidemic response by limiting scientific discourse. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 92(2), 240–241. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.14-0803

Barabási, A. (1999). Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science, 286(5439), 509–512. doi:10.1126/science.286.5439.509

Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks: How social production trans-forms markets and freedom. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Benkler, Y., Roberts, H., Faris, R., Solow-Niederman, A., & Etling, B.

(2013, July 19). Social Mobilization and the Networked Public Sphere: Mapping the SOPA-PIPA Debate. Retrieved June 22, 2015, fromhttp://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2295953 Bever, L. (2014, October 17). Chain reaction: Concern about Ebola Nurse’s

flight prompts school closings in two states. The Washington Post. Retrieved June 22, 2015, fromhttp://wapo.st/11xeMU0

Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J., Lambiotte, R., & Lefebvre, E. (2008, October 9). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2008(10), 10008. doi:10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/p10008

Bogoch, I. I., Creatore, M. I., Cetron, M. S., Brownstein, J. S., Pesik, N., Miniota, J., . . . Khan, K. (2015, January). Assessment of the potential for international dissemination of Ebola virus via commercial air travel during the 2014 west African outbreak. The Lancet, 385(9962), 29–35. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736 (14)61828-6

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015, September 22). 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa—Case counts. Retrieved from http:// www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/case-counts.html Chandler, C., Fairhead, J., Kelly, A., Leach, M., Martineau, F., Mokuwa, E.,

. . . Wilkinson, A. (2015, April). Ebola: Limitations of correcting mis-information. The Lancet, 385(9975), 1275–1277. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62382-5

Doctors Without Borders. (2015, March 23). Ebola: Pushed to the limit and beyond. Retrieved from https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/sites/ usa/files/msf143061.pdf

Drazen, J. M., Kanapathipillai, R., Campion, E. W., Rubin, E. J., Hammer, S. M., Morrissey, S., & Baden, L. (2014, November). Ebola and quar-antine. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(21), 2029–2030. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1413139

Faris, R., Roberts, H., Etling, B., Othman, D., & Benkler, Y. (2015, February 10). Score another one for the Internet? The role of the networked public sphere in the U.S. net neutrality policy debate. Berkman Center Research Publication No. 2015-4. Social Science Research Network. Retrieved September 28, 2015, from,http://ssrn.com/abstract=2563761

Financial Tracking Sevice. (2015). Ebola Virus Outbreak—West Africa, April 2014. Tracking Global Humanitarian Aid Flows. Retrieved fromhttps://fts. unocha.org/pageloader.aspx?page=emergencyDetails&emergID=16506 Graeff, E., Stempeck, M., & Zuckerman, E. (2014, February 3). The battle for

‘Trayvon Martin’: Mapping a media controversy online and off-line. First Monday, 19(2). doi:10.5210/fm

Hargittai, E., Gallo, J., & Kane, M. (2007). Cross-ideological discussions among conservative and liberal bloggers. Public Choice, 134(1–2), 67– 86. doi:10.1007/s11127-007-9201-x

Hindman, M. (2008). The myth of digital democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lancet. (2014, November 8). The medium and the message of Ebola. The Lancet, 384(9955), 1641. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62016-X Lancet Infectious Diseases. (2014, December 14). Rationality and

coordina-tion for Ebola outbreak in west Africa. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 14(12), 1163. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71020-5

McCarthy, M. (2014a, October 20). Obama calls for calm as US ramps up domestic Ebola response. BMJ, 349, g6333.

McCarthy, M. (2014b, October 22). US revamps domestic Ebola response. BMJ, 349, g6417.

Merino, J. G. (2014). Response to Ebola in the US: Misinformation, fear, and new opportunities. BMJ, 349, g6712–g6712. doi:10.1136/bmj.g6712

Milo, P. (2014, October 21). Maple Shade school official apologizes for Ebola scare, report says. NJ.com. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/ 1KRGfkd

Mitman, G. (2014, November). Ebola in a stew of fear. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(19), 1763–1765. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1411244 Oyeyemi, S. O., Gabarron, E., & Wynn, R. (2014, October). Ebola, Twitter, and misinformation: A dangerous combination? BMJ, 349(oct14 5), g6178–g6178. doi:10.1136/bmj.g6178

Ratzan, S. C., & Moritsugu, K. P. (2014). Ebola crisis–communication chaos we can avoid. Journal of Health Communication: International Perspectives, 19(11), 1213–1215. doi:10.1080/ 10810730.2014.977680

Rosenbaum, L. (2015, January). Communicating uncertainty—Ebola, public health, and the scientific process. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(1), 7–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1413816

Santora, M. (2014, October 24). First patient quarantined under strict new policy tests negative for Ebola. The New York Times. Retrieved June 22, 2015, fromhttp://nyti.ms/1z48o4v

Trad, M.-A., Fisher, D. A., & Tambyah, P. A. (2014, November). Ebola in west Africa. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 14(11), 1045. doi:10.1016/ S1473-3099(14)70924-7

World Health Organization. (2015a, September 23). Ebola situation report —23 September 2015. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/ebola/current-situation/ebola-situation-report-23-september-2015

World Health Organization. (2015b, July), Report of the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/csr/resources/ publications/ebola/ebola-panel-report/en/