MITLIBRARIES

3

9080

02618

4587

*

I

\*

LIBRAaiBS

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

HB31

.M415

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

DOES

HAZARDOUS

WASTE

MATTER?

EVIDENCE

FROM

THE

HOUSING MARKET

AND

THE

SUPERFUND

PROGRAM

Michael

Greenstone

Justin

Gallagher

Working

Paper

05-27

October

31,

2005

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

This

paper can

be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science Research

Network Paper

Collection at

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTEOF

TECHNOLOGY

NOV

1 i\ ZUllbDoes

Hazardous Waste

Matter?

Evidence

from

theHousing

Market and

theSuperfund

Program*

Michael

Greenstone

and

JustinGallagher

October

2005

*

We

thankDaron Acemoglu, David

Autor,Maureen

Cropper, Esther Duflo,Dick

Eckhaus, Alex Farreli,Don

Fullerton,Ted

Gayer, Jon Gruber, Jon Guryan, Joe Gyourko, Paul Joskow,Matthew

Kahn.David

Lee,Jim

Poterba, Katherine Probst, Bernard Saianie, Randall Walsh,Rob

Williams, and especiallyTed

Gayer

for insightfulcomments.

The

paperalso benefited from thecomments

of seminarparticipants atASSA,

BYU,

UC-Berkeley,UC-Davis. UC-Santa

Barbara,CEMFI,

Colorado, Columbia,HEC

Montreal.Kentucky,

LSE,

MIT,

NBER,

Rand, Resources for the Future, SITE, Stanford, Syracuse, Texas, andUCLA.

Leila Agha, Brian Goodness, ElizabethGreenwood,

Rose

Kontak, William Li, and JonathanUrsprung

providedoutstanding research assistance.We

especiallythankKatherineProbst forgenerouslysharing dataon the costs ofSuperfund clean-ups. Funding from the Center for Integrating Statistical and

Environmental Scienceatthe UniversityofChicago andtheCenterfor

Energy

and Environmental PolicyDoes

Hazardous

Waste

Matter?

Evidence

from

theHousing

Market

and

theSuperfund

Program

Abstract

Approximately $30

billion(2000$) has been spent on Superfundclean-ups of hazardous wastesites, andremediation efforts are incomplete at roughly halfofthe 1,500 Superfundsites. This study estimates the

effectof Superfund clean-ups on local housingprice appreciation.

We

compare

housing pricegrowth intheareas surroundingthe first

400

hazardous waste sitesto becleanedup

throughthe Superfiindprogram

to the areas surrounding the

290

sites that narrowly missed qualifying for these clean-ups.We

cannotrejectthat the clean-ups had no effecton local housing price growth, nearly

two

decades afterthese sitesbecame

eligible for them. This finding is robust to a series of specification checks, including theapplication ofa quasi-experimental regression discontinuity design based on

knowledge

ofthe selectionrule. Overall, the preferred estimates suggest that the benefits of Superfund clean-ups as

measured

through the housing market are substantially lowerthan the $43 million

mean

cost ofSuperfundclean-ups.

Michael Greenstone Justin Gallagher

MIT,

Department

ofEconomics

Department

ofEconomics

50

Memorial

Drive,E52-359

549

Evans

Hall,MC

3880

Cambridge,

MA

02142-1347

UC

Berkeleyand

NBER

' Berkeley,CA

94720-3880

Introduction

The

estimation of individuals' valuations of environmental amenities with revealed preferencemethods

has been an active area ofresearch formore

than three decades.Numerous

theoreticalmodels

outlining revealed preference

methods

to recover economically welldefmed

measures ofwillingness topay have been developed. In principle, these

methods

can be used in a variety ofsettings, includinghousingmarkets, recreational choices, health outcomes, andthe

consumption

ofgoods designedtoprotectindividuals against adverse environmentally-induced outcomes.'

The

application of these approaches,however, is often

accompanied

by seemingly valid concerns about misspecification thatundermine

thecredibility ofany findings. Consequently,

many

are skeptical that markets can be used to determineindividuals" valuation of environmental amenities. Further, the increasing reliance on stated preference

techniques to value enviromnental amenities is surely related to dissatisfaction with the performance of

revealed preference techniques.^

Hazardous

wastesites are anexample

of an environmental disamenity that provokes greatpublicconcern.

The

1980Comprehensive

Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act,which

became

known

as Superfund, aims to address this concern.The

Act gave theEPA

the right to initiateremedial clean-ups at sites

where

a release or significant threat ofa release ofa hazardous substanceposes an

imminent

andsubstantial dangertopublic welfare andtheenvironment. Sincethepassage oftheSuperfund legislation,

more

than 1,500 sites have been placed on the National Priorities List (NPL),qualifyingthose sites forfederally financedremediation.

As

of 2000, approximately$30

billion (2000$)has been spent on clean-ups,

and

remediation efforts are incomplete atroughly halfofthesites. Despitethese past and future expenditures, there has not been a systematic accounting of the benefits of

Superfund clean-ups of hazardous wastesites.

As

aresult,Superfundis a controversialprogram.^This paper estimates the effect ofSuperfund sponsored clean-ups of hazardous waste sites on

SeeFreeman(2003) and

Champ,

Boyle,andBrown

(2003)forreviews."See

Hanemann

(1994))andDiamond

andHausman

(1994)fordiscussionsofstatedpreference techniques.

^ In March 1995 in Congressional testimony, Katharine Probst ofResources for the Future said, "Although the

program hasbeenin existenceforover 14years,

we

stillknow

very littleaboutthebenefitsofsite cleanuporabouttheassociated costs." Atthesame hearing,JohnShanahan oftheHeritageFoundationsaid,"Superfund...iswidely regardedas a wastetlilandineffectiveprogram indireneedofsubstantive reform."

housingprice appreciation in areassurrounding the sites.

The

empirical challenge isthatthe evolution ofhousing prices proximate to the Superfund sites in the absence of the clean-ups is

unknown.

The

development ofa valid counterfactual is likely to be especially challenging, because thesites assigned to

the

NPL

are themost

polluted ones in the US. Thus, itseems

reasonable toassume

that prices in theseareas are determined by a different process than prices in the remainder of the country for reasons

unrelatedtothe clean-ups. For example,

what

would

havehappened

to housingpricesinLove

Canal,NY,

intheabsenceofthe

famous

clean-upthere?To

solve this problem,we

implement

a quasi-experiment basedon knowledge

ofthe selectionrule thatthe

EPA

usedto developthefirstNPL.

Nearly 15,000 siteswere

referredtotheEPA

aspotentialNPL

sites in 1980-1, but theEPA's

budget could onlyaccommodate

400

clean-ups. Consequently, theyinitially

winnowed

the list to the690

worst sites and then developed theHazardous

Ranking

System

(HRS).

The

HRS

was

used to assign each sitea scorefrom to 100 based on the risk itposed, with 100being the

most

dangerous.The

EPA

placedthe400

sites withHRS

scores exceeding28.5on

the initialNPL

in 1983,making them

eligible for Superfund remedialclean-ups.Our

empirical strategy exploits this selection process by focusing on the areas surrounding the690 hazardous waste sitesthat

were

finalists forthe initialNPL.

We

compare

theevolutionofresidentialproperty values inthe areasnearsitesthat had initial

HRS

scores exceeding28.5 totheareasproximatetosites that had

HRS

scoresbelow

the 28.5 threshold.The

assumption is that the evolution of housingprices in the areas surrounding the sites with scores

below

28.5 form a valid counterfactual for priceappreciation in areas near sites with

HRS

scores above the threshold.We

alsoimplement

aquasi-experimental regression discontinuitydesign

(Cook

andCampbell

1979) to focus the comparisons inthe"neighborhood" ofthecut-off

The

implementation of thisHRS

based research design suggests that the placement of ahazardous wastesite on the

NPL

is associated witheconomically small andstatistically indistinguishablefrom zero gains in residential property values. Thisfindingholdswhetherthe growth in housing prices is

measured

7 or 17 years after the sites' placement on theNP.

Moreover, it is robust to a variety' ofspecification checks, including the regression discontinuity approach.

The

validity of these results isfurther supported by the finding that observable ex-ante determinants ofhousing price appreciation are

well balanced

among

census tracts containing sites withHRS

scoresabove

andbelow

28.5, especiallynear the cut-off Overall, these findings suggest that the

mean

benefits of a Superfund clean-up asmeasured

through the housing market are substantially lower than the $43 millionmean

cost of aSuperfundclean-up.

A

few

otherresults fromtheHRS

research design are noteworthy. There is little evidencethat asite's placement on the

NPL

causes an immediate decline in rental rates or housing prices,which

undermines the popular stigma hypothesis (e.g., Harris 1999). Additionally,

we

cannot reject that theclean-ups fail to cause changes in the fractions of minorities, children or other

demographic

characteristics ofthe population inthe areassurroundingthe sites."* Finally, there is

modest

evidencethattheclean-ups are associated with population increasesinthecensustracts containing thesites.

The

conventional hedonic approach uses ordinary least squares to estimate the effect ofa site'splacement on the

NPL

on

housing price appreciation.The

basis ofthis approach is a comparison oftheareas surrounding

NPL

sites with the remainder oftheUS.

In contrastto theHRS

research design, theconventional approach produces estimates that suggest that gains in property values exceed the

mean

costs ofclean-up.

However,

these regressions also produce anumber

ofpuzzling resultsthatundennine

confidence in the approach's validity. Further, the ex-ante determinants ofchanges in housing prices

differdramatically

between

areassurroundingNPL

sitesandthe restofthe country.These

latterfindingsunderscore the importance of the

HRS

research design as a potential solution to the misspecificationproblems that have plagued the conventional implementation ofthe hedonic approach in other settings

and appearto

undermine

ithere.In addition to the availability ofthe

HRS

research design, this study hastwo

other appealingfeatures. Firsttoconductthestudy,

we

assembledthemost

comprehensivedatafile ever compiled bytheEPA

or other researchers on the Superfundprogram

and its effects.The

resulting database hasSee Banzhafand Walsh (2005) and Cameron and

McConnaha

(2005) for evidence of migration induced byinformationon all Superfund hazardous wastesites,the sitesthat narrowly missed placement

on

the initialNPL,

and census-tractlevel housingprices for 1980, 1990, and 2000.The

data filealso contains awealthof information aboutthehazardous wastesites,includingtheirprecise location,

HRS

scores, expectedandactual

(when

remediation is complete) costs ofclean-up, size in acres, and dates they achieved variousmilestones (including completion of remediation). Consequently, this study is a substantial departure

from

the previous Superfund/hazardous waste site hedonic literature,which

is entirely comprised ofexaminations ofa singlesite orhandful ofthem.^

Second,

we

utilize consumers' reveled preferences andassume

thatthey transmittheirvaluationsofthe clean-upsthrough the housing market. Ifthe housing market isoperating correctly, pricechanges

will capture the healthand aestheticbenefits ofclean-ups. Further, hedonic theory can be used to relate

theresults tothetheoreticallycorrect welfare

measure

ofwillingness to pay. Thus,thisapproach freesusfrom a relying

on

state preference techniques or the notoriously poor laboratory estimates of risk tohuman

health associated with the thousands of chemicals present at the sites and assumptions aboutthecorrect valueofastatistical life.*

The

paper proceeds as follows. Section I provides background on the Superfimdprogram

andhow

its initial implementation provides a research design thatmay

allow for credible estimation oftheeffects ofSuperfundclean-ups

on

priceappreciation. SectionII reviewsthe hedonicmethod

theoreticallyand empirically and uses it to provide an

economic

interpretation for the results from theHRS

researchdesign. Section III details the data sources and provides

some

summary

statistics. SectionsIV

andV

reports onthe econometric

methods

andempirical findings, respectively. Section VI interprets theresultsanddiscussesthepolicy implications, while VII concludes.

I.

The

Superfund

Program

and

aNew

Research Design

'

A

partiallistofprevious Superfund/hazardous wastesitehedonicstudiesincludesSchmalenseeetal.(1975), Smith and Michael (1990), Kohlhase (1991), Kiel (1995), Gayer Hamilton, and Viscusi (2000, 2002), Kiel and Zabel

(2001),McCluskey and Rausser(2003), Ihlanfeldtand Taylor(2004),Messeretal.(2004),and Farrell(2004).

'Viscusiand Hamilton (1999)

use

EPA

providedestimates ofthe probabilityofcancer cases atasubsample ofsitesand find that at themedian site expenditure the average cost per cancer case averted by the clean-up exceeds S6

A. Histoiy

and

Broad

Progi-amGoalsBefore the regulation ofthe disposal of hazardous wastes by the Toxic Substances Control and

Resource

Conservation andRecovery

Acts of 1976, industrial firms frequently disposed of wastes byburying

them

in the ground.Love

Canal,NY

is perhaps themost

infamousexample

ofthese disposalpractices.

Throughout

the 1940s and 1950s, this areawas

a landfill for industrial waste andmore

than21,000 tons ofchemical wastes

were

ultimately depositedthere.The

landfill closed in the early 1950sand overthe next

two

decades acommunity

developed in that area. Inthe 1970s,Love

Canal residentsbegan

tocomplain of high rates ofhealth problems, such as cancer, birth defects, miscarriages, and skinailments. After

New

York

state investigators found high concentrations of dangerous chemicals in theair

and

soil, concerns about the safety of this areaprompted

President Carter to declare a state ofemergency

that led to therelocation ofthe900

residents ofthis area.The Love

Canal incidenthelpedtogalvanize support for addressing the legacy of industrial waste and this led to the creation of the

Superfund

program

in 1980.The

centerpiece ofthe Superfund program, andthispaper's focus, isthe long-run remediation ofhazardous waste sites.^

These

multi-year remediation effortsaim

to reducepermanently the serious, butnot imminently life-threatening, dangers caused by hazardous substances.

As

of 2000, roughly 1,500sites

have

been placedon theNPL

andthereby chosen forthese long-run clean-ups.The

nextsubsectiondescribes the selection process,

which

formsthebasisof ourresearch design.B. SiteAssessment

&

SuperfundClean-Ups

ProcessesAs

of 1996,more

than 40,000 hazardous waste sites had been referred to theEPA

for possibleinclusion on the

NPL.

The

EPA

follows a multi-step process to determinewhich

ofthese sites posethegreatest danger to

humans

and the environment.The

assessment process involves determiningwhich

'

EPA

(2000)claimsthat56%

ofthe childrenbom

inLoveCanal between 1974 and 1978 hadbirthdefects.The Superfund program also funds immediate removals. These clean-ups are responses to environmental emergencies and are generally short-term actions aimed at diminishing an immediate threat. Examples ofsuch

actions including cleaningup wastespilledfromcontainers and constructing fencesaround dangeroussites. These

actions are not intended to remediatethe underlying environmental problem and accountfor a small proportion of Superfundactivities. Importantly, they areadministeredathazardous wastesitesthatareandarenotonthe

NPL.

hazardous chemicals arepresentatthesiteandthe overall risk level.

The

final step ofthe assessment process is the application of theHazardous

Ranking

System

(HRS), which

is reserved for themost

dangerous sites.The

EPA

developed theHRS

in 1982 as astandardized approach to quantify

and

compare

thehuman

health and environmental riskamong

sitestoidentify the ones that pose the greatest threat.

The

originalHRS

evaluated the risk for exposure tochemical pollutants alongthreemigration 'pathways'; groundwater, surface water, and air.'

The

toxicityand concentration ofchemicals, the likelihoodof exposure and proximity to

humans,

andthe populationthatcould be affected are themajor determinants ofriskalong eachpathway.

The non-human

impactthatchemicals

may

have is considered during the process ofevaluating the site but plays aminor

role indeterminingthe

HRS

score.The

HRS

produces a score for each site that ranges from to 100, with 100 being the highestlevel ofrisk.

From

1982-1995,theEPA

assigned all hazardous waste sites with aHRS

score of28.5 orgreaterto theNPL.'"

These

sitesarethe onlyonesthatare eligible forSuperfund remedialclean-up.The

Data

Appendix

provides furtherdetails onthedeterminationofHRS

test scores.Once

a site is placedon

theNPL,

itgenerally takesmany

years until clean-up is complete.The

first step is a further study ofthe extentofthe environmental

problem

and

how

best toremedy

it. Thisassessment is

summarized

intheRecord

of Decision(ROD), which

also outlinesthe clean-up actionsthatare planned for the site.

The

site receives the "construction complete" designation once the physicalconstructionofall clean-upremedies iscomplete,theimmediate threats tohealthhave been removed, and

thelong-run threatsare"undercontrol."

The

final stepisthesite's deletion fromtheNPL.

'In

1990,the

EPA

revised theHRS

testsothatitalsoconsiderssoilasanadditionalpathway.'°

In 1980 every statereceived the right to placeone site onthe

NPL

withoutthe sitehaving toscore at orabove28.5 on the

HRS

test. As of 2003, 38 states have used theirexception. It isunknown

whether these sites wouldhavereceived a

HRS

scoreabove28.5.In 1995 thecriteriafor placement on the

NPL

were altered sothat asite musthave aHRS

score greater than 28.5and thegovernor ofthestate inwhichthesite islocatedmust approvetheplacement. Therearecurrentlyanumber

ofpotential

NPL

siteswithHRS

scores greaterthan 28.5 that have not been proposed forNPL

placementdue toknown

state political opposition.We

do notknow

the precise number of these sites because our Freedom ofC.

1982

HRS

Scoresas theBasisof

aNew

ResearchDesign

This paper's goal is to obtain reliableestimates ofthe effectofSuperfund sponsoredclean-upsof

hazardous waste sites on housing price appreciation in areas surrounding the sites.

The

empiricalchallenge isthat

NPL

sites are themost

polluted intheUS,

so the evolution of housing prices near thesesites

may

not becomparable

to that of the remainder of theUS,

even conditional on observablecovariates.

To

avoid confounding the effects oftheclean-ups with unobserved variables, it is necessaryto develop a valid counterfactual for the evolutionofproperty valuesat Superfundsites in theabsenceof

thosesites' placement on the

NPL

andeventual clean-up.A

featureoftheinitialNPL

assignmentprocess thathas notbeen notedpreviously byresearchersmay

provide a credible solution to the likely omitted variables problem. In the first year after thelegislation's passage in 1980, 14,697 sites

were

referred to theEPA

and investigated as potentialcandidates forremedial action.

Through

the assessment process, theEPA

winnowed

this listto the690

most

dangerous sites.Although

the Superfund legislation directed theEPA

to develop aNPL

of "atleasf

400

sites(Section 105(8)(B) ofCERCLA),

budgetary considerations caused theEPA

to set a goalofplacing exactly

400

sitesontheNPL.

The

EPA

developed theHRS

to determine scientifically the400

out ofthe 690 sites that posedthe greatestrisk. Pressured to initiatethe clean-ups quickly,the

EPA

developedtheHRS

in aboutayear.The

HRS

testwas

appliedtothe690

worst sites, andtheirscoreswere

ordered fromhighesttolowest.A

scoreof28.5 divided

numbers 400

and401, so the initialNPL

published inSeptember

1983was

limitedtosites with

HRS

scores exceeding28.5."The

central roleoftheHRS

scoreprovides acompelling basis fora research designthatcompares

outcomes

atsites with initial scoresabove

andbelow

the28.5 cut-offforat leastthreereasons. First, it isunlikelythat sites'

HRS

scoreswere

manipulated toaffect their placementon theNPL,

becausethe 28.5threshold

was

established after the testing ofthe690

siteswas

completed.The

HRS

scores therefore" Exactly 400 ofthe sites on the initial

NPL

hadHRS

scores exceeding 28.5. The original Superfund legislationgave each statethe right to placeone siteon the

NPL

without going through the usual evaluation process. Sixofthese"state priority sites"wereincludedontheoriginal

NPL

released in 1983. Thus, the original listcontainedthereflected the

EPA's

assessment ofthehuman

health and environmental risks posed by each siteand were

notbasedontheexpected costsor benefitsofclean-up.

Second,the

HRS

scores werenoisy measures ofrisk,so it ispossiblethat true riskswere

similarabove and

below

the threshold. This noisinesswas

a consequence ofthe scientific uncertainty aboutthehealth consequences of exposure to the tens of thousands of chemicals present at these sites.'" Further,

the threshold

was

not selected basedon

evidence thatHRS

scoresbelow

28.5 sites posed little risk tohealth. In fact,theFederal Registerspecifically reportedthatthe

"EPA

has notmade

a determinationthatsites scoring less than 28.50 do not present a significant risk to

human

health, welfare, or theenvironment"(FederalRegister 1984, Section IV)

and

thatamore

informativetestwould

require "greatertimeand funds"

(EPA

1982).'^Third, the selection rule that determinedthe placement

on

theNPL

isa highly nonlinear functionofthe

HRS

score. Thisnaturally lends itselfto acomparison ofoutcomes

at sites "near" the 28.5 cut-offIfthe unobservables are similar around the regulatory threshold, then a comparison ofthese sites will

control for all omitted factors correlated with the outcomes. This test has the features of a

quasi-experimentalregression-discontinuity design

(Cook

andCampbell

1979).'''An

additional feature ofthe analysis is that an initial score above 28.5 is highly correlated witheventual

NPL

status butis not a perfect predictorofit. Thisis becausesome

siteswere

rescored,withthe'"

A

recent

summary

ofSuperfund'shistorymakesthispoint. "AttheinceptionofEPA's Superfund program,therewas

much

to be learnedabout industrial wastesandtheir potential forcausingpublic health problems. Beforethisproblem could be addressed on the program level, the types of wastes most often found at sites needed to be

determined, andtheirhealtheffects studied. Identifyingand quantiiyingriskstohealthandtheenvironmentforthe

extremelybroad range ofconditions,chemicals,andthreatsatuncontrolledhazardous wastessitesposed formidable

problems.

Many

ofthese problems stemmed from the lack ofinformation concerning the toxicities ofthe over 65,000 different industrial chemicals listedas having been in commercial production since 1945" (EP.A 2000, p. 3-2).'^

One way

tomeasurethecnidenatureoftheinitialHRS

test isbythedetailoftheguidelinesusedfordeterminingthe

HRS

score. TheguidelinesusedtodeveloptheinitialHRS

siteswerecollectedina30 page manual. Today,theanalogousmanual ismorethan500pages.

'''

The research design ofcomparing sites with

HRS

scores "near" the 28.5 is unlikely to be valid for sites thatreceived an initial

HRS

score after 1982. This is because once the 28.5 cut-offwas set, theHRS

testers wereencouraged to minimize testingcosts and simply determine whether asite exceeded the threshold. Consequently,

testers generally stop scoring pathways once enough pathways are scoredto produce a score above thethreshold.

When

only someofthepathways are scored,thefullHRS

scoreisunknown

andthequasi-experimental regression discontinuitydesign isinappropriate.laterscoresdetermining whetherthey

ended

up onthe NPL.'^The

subsequentanalysis uses an indicatorvariable forwhetherasite's initial (i.e., 1982)

HRS

scorewas

above28.5 asan instrumental variable forwhetherasite

was

ontheNPL

into purgethepotentiallyendogenous

variation inNPL

status.Finally, it importantto

emphasize

that sites that failed to qualify for theNPL

were

ineligible forSuperfund remediations.

We

investigated whether these siteswere

cleaned-up under state or localprograms and foundthatthey

were

frequentlyleft untouched.Among

thesitesthatwere

targetedby theseprograms, atypical solution

was

to put a fence around thesite and place signs indicating thepresence ofhealth hazards.

The

point is thatthe remediation activities atNPL

sites drastically exceededtheclean-upactivitiesat

non-NPL

sitesbothinscopeandcost.-y' ' '

..

11.

The Hedonic

Method

and

How

ItCan

Be Used

toInterprettheHRS

Research Design

ResultsA. The

Hedonic

Method and

ItsEconometric

IdentificationProblems

An

explicit market for a clean local environment does not exist.The

hedonic pricemethod

iscommonly

used to estimate theeconomic

value of non-market amenities like environmental quality toindividuals. It is based on the insight thatthe utility associated with the

consumption

ofa differentiatedproduct, such as housing, is determined by the utility associated with the good's characteristics. For

example, hedonic theory predicts thatan

economic

bad, such as proximity toahazardous waste site, willbe negatively correlated with housing prices, holding all other characteristics constant. This section

reviews the hedonic

method

and describes the econometric identification problems associated with itsimplementation.

Economists have estimated the association

between

housing prices and environmental amenitiesat least since Ridker (1967) and Ridker and

Henning

(1967).However, Rosen

(1974) andFreeman

(1974)

were

the first to give this correlation aneconomic

interpretation. In theRosen

formulation, adifferentiated

good

can bedescribedby a vectorofitscharacteristics,Q

=

(qi, q^,..., qn)- Inthecase ofa'^

As

an example, 144 sites with initial scoresabove 28.5 were rescored and this led to 7 sites receiving revised scores belowthecut-off. Further,complaints by citizensandothers led torescoring ata numberofsites below the cut-off. Althoughthere hasbeensubstantialresearch onthequestionofwhichsitesontheNPL

arecleaned-upfirst (see, e.g.,Sigman2001),we

areunawareofanyresearchonthedeterminantsofasitebeingrescored.house, these characteristics

may

include structural attributes (e.g.,number

ofbedrooms), neighborhoodpublic services (e.g., local school quality), and local environmental amenities (e.g., distance from a

hazardous wastesite). Thus,the price ofthei"' house can be written as:

(1) Pi

=

P(q,,q2,...,q„).The

partial derivative ofP(») with respect tothe n"' characteristic, d?/dq„, is referredto as the marginalimplicit price. Itisthemarginalprice ofthe n"'characteristic implicitin the overall priceofthehouse.

In a competitive market, the locus

between

housing pricesand

a characteristic, or the hedonicpriceschedule(HPS), isdetermined by the equilibrium interactionsof

consumers

andproducers.'* Inthehedonicmodel, the

HPS

isformed

by

tangenciesbetween

consumers' bidand suppliers' offerfunctions.The

gradient ofthe implicit price function with respect to the health risk associated with proximity tohazardous waste sites gives the equilibrium differential that compensates individuals for accepting the

increased healthrisk. Put another

way,

areas withelevated healthrisksmust

have lower housingprices toattract potential

homeowners

andtheHPS

reveals the price that allocates individualsacross locations. Inprinciple, the price differential associated with proximity to hazardous waste sites reflects both

individuals' valuations ofthegreater health riskand anyeffecton neighborhoodaesthetics.'^

At

each point on theHPS,

the marginal price of a housing characteristic is equal to anindividual's marginal willingness to pay

(MWTP)

for that characteristic and an individual supplier'smarginal cost ofproducing it. Sincethe

HPS

reveals theMWTP

at agiven point, itcan be usedto inferthe welfare effects ofa marginal

change

in a characteristic.The

overall slope oftheHPS

provides anestimate ofthe average

MWTP

across all consumers. In principle,the hedonicmethod

can also be usedto recover individuals'

demand

orMWTP

functions,which would

beoftremendous

practical importancebecausethese functionsallow forthe calculationofthewelfareeffectsofnonmarginal changes.'*

Our

focus is limited to the successful estimation ofequation (1),which

is the foundation for"^ SeeRosen

( 1974),Freeman(1993), and Palmquist( 1991)for details.

"

Thehedonic approach cannot accountforaestheticbenefitsthataccruetononresidents that, forexample,engageinrecreationalactivitiesnear thesite. Thehealtheffectsapproachhasthissamelimitation.

'* Rosen

(1974) proposed a 2-step approach for estimating the

MWTP

function, as well as the supply curve. Inrecentwork, Ekeland,

Heckman

and Nesheim(2004)outline theassumptions necessaryto identifythedemand(andwelfarecalculations of both marginal

and

non-marginal changes. Consistent estimationmay

be difficultsinceit islikelythatthereareunobserved factors thatcovary with both proximity tohazardous wastesites

and housing prices.

Although

this possibility cannot be directly tested, it is notable that proximity to ahazardous waste site is associated with a

number

ofimportant observable predictors of housing prices.For

example

compared

to the rest ofthe country, areas with hazardous waste sites nearby tend to havelower population densitiesand mobile

homes

comprisea higher proportionofthe housingstock.Consequently, cross-sectional estimates ofthe association

between

housing prices and proximityto a hazardous waste site

may

be severely biased due to omitted variables.'^In fact, the cross-sectional

estimation ofthe

HPS

has exhibited signs ofmisspecification in anumber

ofothersettings, including therelationships

between

land prices and school quality, totalsuspended

particulates air pollution, andclimate variables (Black 1999;

Deschenes

and Greenstone 2004;Chay

and Greenstone 2005)."" Small(1975) recognizedthe consequences ofthemisspecificationof equation(1) just one yearafterpublication

ofthe

Rosen

andFreeman

papers:I have entirely avoided...the important question ofwhether the empirical difficulties, especially correlation

between

pollution andunmeasured neighborhood

characteristics,areso

overwhelming

as to render theentiremethod

useless. Ihope

that...futurework

canproceed to solving these practical problems....

The

degree of attention devoted to this[problem]...is

what

will reallydetermine whetherthemethod

stands orfalls..." [p. 107].Rosen

himself recognized the problemand

expressed skepticism that the hedonicmethod

could beimplemented

successfully in a cross-sectional setting."' Yet, in the intervening years, thisproblem

ofmisspecification has received little attention from empirical researchers.

One

ofthis paper's aims is todemonstratethatit

may

be possibletoobtainreliablehedonicestimates witha credibleresearch design.B.

Using

Hedonic

TheorytoInterpret theResultsfrom

the1982

HRS

Research Design

"

Incorrect choice offunctional form is an alternative source ofmisspecification ofthe HPS. See HalvorsenandPoilakowski (1981) and Cropperetal.(1988)fordiscussionsofthis issue.

"°

Similarproblemsarise

when

estimatingcompensatingwagedifferentialsforjobcharacteristics, suchastheriskofinjuryor death. Theregression-adjusted associationbetweenwagesand

many

job amenitiesisweak

and oftenhas a counterintuitive sign(Smith 1979; Black and Kneisner2003).^' Rosen

(1986) wrote, "Itis clearthat nothing can be learnedaboutthe structure ofpreferences in asingle cross-section..."(p. 658),and

"On

theempirical sideofthese questions, the greatestpotential forfiirther progress rests indevelopingmoresuitablesourcesofdataonthe natureofselectionand matching..."(p.

The

hedonicmodel

describes amarket in equilibrium and ismost

readily conceivedofin across-sectional setting.

However,

our research design assesses the effect of Superfund remediations ofhazardous waste sites nearly

two

decades after the release oftheNPL.

Consequently, this subsectiondiscusses the interpretationoftheestimableparameters fromthe

HRS

research design.^^To

fix thoughts, defineR

as the monetary value ofthe stream ofservices provided by a houseoveraperiod oftime, ortherental rate.

We

assume

R

is a functionof an index ofindividuals' disutilityassociated with living near a hazardous waste site.

The

index is denoted asH

and is a function oftheexpected health risks and any aesthetic disamenities.

dRI

dH

<

0, because, for example, individuals'willingnesstopayto rentahouse is decreasinginthe health riskassociatedwithresiding in it.

Now,

considerhow

H

changesforindividualsthat live near ahazardous wastesite placedon

theinitial

NPL

asthesiteprogressesthroughthedifferentstagesofthe Superfundprocess:(2)

Ho =

Index Before SuperfundProgram

Initiated(e.g., 1980)Hi

=

Index AfterSitePlacedon theNPL

H2

=

IndexOnce

ROD

Published/Clean-Upis InitiatedH3

=

IndexOnce

"ConstructionComplete"

orDeletedfrom

NPL.

Notably, the clean-up process is slow. For example, the

median

timebetween

NPL

listingand

achievement oftheconstructioncompletemilestone is

more

than 12years.It

seems

reasonabletopresume

thatHo

>

H:, sothatR(H3)

>

R(Ho), because clean-ups reducethehealth risks and likely increase the aesthetic value of proximityto the site. It is not evident

whether

Hiand H2 aregreaterthan, less than, orequal toHq. Itis frequentlyarguedthatthe

announcement

thata siteis eligible for Superfund remediation causes

H

to increase, because placement on theNPL

may

causeresidentsto revise

upwards

their expectationofthehealthrisk.^^""*

^"

An

alternative valuation approach is toplace amonetary value on any health improvements associated with thecleaning-up ofa hazardous waste site. This approach involves four non-trivial steps. Specifically, itentails the determinationof: thetoxicspresentateachsiteandthepathwayswheretheyarefound(e.g., air, soil,groundwater); the healthrisksassociatedwithtoxicandpathway pair(thisisespecially difficultbecausetherehave beenmorethan

65,000 chemicals inproductioninthe

US

sinceWorldWar

IIand duetotheinfeasibilityoftestingofhumans

duetovalid ethical concerns); knowledge about thesize oftheaffected population and their pathway-specific exposure

(see Hamilton and Viscusi 1999 on the associated challenges); and willingness to pay to avoid mortality' (Viscusi 1993; Ashenfelterand Greenstone 2004a, 2004b). In lightofthe substantial scientific, empirical, and data quality

concerns with eachofthesesteps,ourview isthatat presentthis approach isunlikelyto producecredibleestimates

ofthebenefitsofSuperfijnd clean-ups. Furtherby itsverynature, itcannotaccountforany aesthetic benefits.

"^ The

stigmahypothesis is arelated idea. Itstates thatevenafter remediation individuals will assume incorrectly

thatproperties near Superfundsites have anelevated health risk, relative to risk beliefsbefore itsplacementon the

We

cannow

writethe constantdollarmean

price of houses in the vicinity ofthe hazardous wastesites considered for placement on the initial

NPL.

We

begin with the price ofhouses withHRS

scoresexceeding28.5

(measured

aftertheNPL

listing):^3^p//«s>285

^^

l(H,

= H,)5'R(H,)+l(H, = H2)5'R(H2)+l(H, =

H3)5'R(H3).'=0

Inthis equation, the indicator variables 1() equal 1

when

the enclosed statement is true in periodtand 6is adiscount factorbasedon the rate of timepreference.

The

equation demonstrates thatupon

placement on theNPL,

P, ' reflects the expectedevolution ofH

throughouttheclean-upprocess. Further,it isevident that it varies withthestageofthe Superfund clean-up atthetime (i.e.,t) that it is observed. For

example, [P, '*"

| H,

=

H3]>

[P,^

I

H,

=

H|] because theyears ofrelativelylow

rental rates havepassed.

The

constant dollarmean

price ofhouses locatednear thehazardous wastesites withHRS

scoresbelow

28.5 is:^4^p///is<28.5

^

^

6'R(Ho).'=0

We

assume

thatH

isunchanged

forthe sites thatnarrowly missed being placed on theNPL

duetoHRS

scores

below

28.5. If this assumption is valid (if, for example, these sites are never cleaned up), thenP

, *" isidentical inall periods.It is

now

possible to define local residents'mean

willingness to pay forthe listingof an existinghazardous waste site

on

the initialNPL.

This quantity isthe difference between (3) and (4). It shouldbemeasured

immediately afterthe sites areplaced on theNPL

sothatmeasurement

isamong

afixed setofindividuals' bid functions. Further,thistimingofthe

measurement

will ensurethatitwill account fortheinfluence ofthe

NPL

lisfingon

the value of housing services in all potentially affected years. Formally,we

define the theoretically correctmeasure

ofwillingnessto pay(WTP)

as:NPL.

Thus,thereis apermanent negativeeffectonproperty values. Harris(1999) provides areviewofthestigmaliterature.

^^McCluskey

and Rausser (2003) and Messer,Schulze, Hackett,Cameron,andMcClelland (2004) provide evidence

thatpricesdecline immediatelyaftertheannouncementthatalocalsite hasbeenplacedonthe

NPL.

Theintuition isthatresidents

knew

thatproximitytothesitewasundesirable buthad underestimatedtherisks.'

(5)AwTP=[Pf^''"'^^ -Pf'*-''''=^^'|t

=

October 1983].A\vTP

must

bemeasured

in October 1983, because this is immediately subsequent to the releaseof

theinitial

NPL.

Notice,Awtp

depends on the time required to complete each stage of the clean-up, thediscountrate,andthe

change

inH

ateachstage. IfH|,H2 <

Ho, then the signofA\vtpisambiguous.Since data from 1983 are unavailable and our data

on

housing pricescome

from the decennialcensuses,

we

estimate:(6)A|5c,o„r2ooo=[Pr^'''' -

P

f'^""''1 1=

1990

or 2000].This is the

mean

difference in housing prices nearNPL

andnon-NPL

sitesmeasured

in either 1990 or2000.

The

differencebetween

(5)and

(6) isthat the latterismeasured

either7 or 17 years laterthan theformer.

This delay in measuringthedifference in housingprices is likely tocauses Ai990or2ooo to exceed

the preferred

measure

ofAwtp

fortwo

reasons. First,many

ofthelow

rental rate yearswhere

Ht=

H|have passed by 1990 and 2000. Second,

enough

time has elapsedbetween

NPL

listing and theobservation on prices so that individuals can sort in responseto the

NPL

listing and/or clean-up. Thus,efforts to estimate willingness to pay functions are unlikely to be convincing, leaving successful

estimation of the

HPS

as the empirical goal. Further, Superfund remediations intend to cause largechangesin environmental quality.

The

factthattheHPS

isweakly

greaterthaneach individual's relevantbid function

combined

withthe non-marginal nature ofthe clean-ups is another reasonthat Ai990or2ooo islikelytobe an overestimate of

Awtp-III.

Data Sources

and

Summary

StatisticsA.

Data

SourcesTo

implement

the analysis,we

constructed themost

comprehensive datafileevercompiled ontheSuperfiind program.

The

datafile contains detailed informationon all hazardous wastesitesplacedon

theNPL

by 2000, aswell asthe hazardous waste sites with 1982HRS

scoresbelow

28.5.We

alsocompiledhousing price, housing characteristic,

and

neighborhooddemographic

information for the areassurroundingthesesites.

These

datacome

from Geolytics'sNeighborhood

Change

Database,which

includes informationfromthe 1970, 1980, 1990, and

2000

Censuses. Importantly, the 1980data predate the publication ofthefirst

NPL

in 1983.We

use these data to form a panel of census tracts basedon 2000

census tractboundaries,

which

aredrawn

sothatthey include approximately 4,000 people in 2000.Census

tracts arethe smallest geographic unit that can be

matched

across the 1970-2000 Censuses.''We

restrict theanalysis to the 48,246 out ofthe 65,443

2000

census tracts that have non-missing housing price data in1980 (beforetheSuperfund legislation

was

passed), 1990,and 2000.We

spentconsiderableeffortcollecting precise locationdata(e.g.,longitudeand

latitude)foreachofthe

NPL

sites and hazardous waste sites with initialHRS

scoresbelow

28.5. This informationwas

usedto place thesesites in unique census tracts.

We

also usedGIS

softwareto identify thecensus tractsthat share a border with the tracts with the sites. Additionally,

we

create separate observations for theportion oftracts that fall within circles of varying radii (e.g., 1, 2, and 3 miles) around the sites.

The

subsequent analysis tests for price effects in all three ofthese groupings oftracts.

The

DataAppendix

providesfurther detailson

how we

definedthesegroups oftracts.The

1982HRS

composite scores are a crucialcomponent

ofthe analysis.We

collected thesescores forthe

690

hazardous waste sites considered forplacement on the initialNPL

from various issuesofthe FederalRegister.

We

also obtainedthegroundwater, surface water, and airpathway

scoresfrom

the

same

source.We

collected anumber

of other variables for theNPL

sites. Various issues of the FederalRegister

were

used to determine the dates ofNPL

listing.The

EPA

provided us with a data file thatreports the dates of release of the

ROD,

initiation of clean-up, completion of remediation (i.e.,construction complete), and deletion from the

NPL

for sites that achieved these milestones.We

alsocollected data on the expected costs of clean-up before remediation

was

initiatedand

estimates oftheactual costs for the sites that reached the construction complete stage."^ "^

We

obtained information on"^

SeetheDataAppendix foradescriptionof

how

1980 and 1990 censustracts wereadjusted tofit2000censustractboundaries.

The

EPA

dividessome

sites into separate operatingunitsand issues separateRODs

forthem.We

calculated the cost variables asthesum

acrossalloperating units. Further,we

reserved the constructioncompletedesignation forthe on the size (measured in acres) ofthe

NPL

hazardous waste sitesfrom

theRODs.

See the DataAppendix

formore

detailsonthese variables and oursources.B.

Summary

StatisticsThe

analysis is conducted withtwo

datasamples.We

refer tothe firstasthe "AllNPL

Sample,"and it includes the 1,398hazardous wastesites inthe 50

US

states andthe DistrictofColumbia

thatwere

placed on the

NPL

by January 1, 2000.The

second is labeled the"1982

HRS

Sample," and it iscomprised ofthehazardous wastesites tested forinclusion ontheinitial

NPL,

regardlessoftheireventualNPL

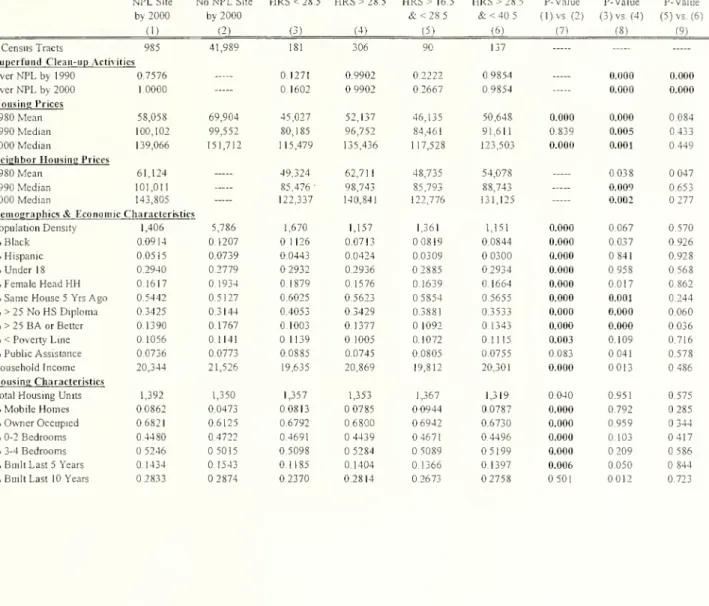

status.^*Table 1 presents

summary

statistics on the hazardous wastesitesin thesesamples.The

entries incolumn

(I) are fromthe AllNPL

Sample and

are limited to sites ina censustract forwhich

thereisnon-missing housingprice data in 1980, 1990, and 2000. After thesesample restrictions, there are 985 sites,

which

ismore

than70%

ofthe sites placed on theNPL

by 2000.Columns

(2) and(3) reportdatafrom

the 1982

HRS

Sample.The column

(2) entries are basedon the487

sitesthatwe

placedin acensus tractwith complete housingpricedata.

Column

(3) reports onthe remaining 189 sites locatedin census tractswith incomplete housingprice data (generally dueto missing 1980 data).

The

14 sites locatedoutside ofthecontinentalUnitedStates

were

dropped fromthe sample.Panel

A

reports onthetimingofthe sites' placementon theNPL.

Column

(1)revealsthat about75%

ofallNPL

sitesreceived this designation in the 1980s. Together,columns

(2) and (3) demonstratethat 443 ofthe

676

sites in the 1982HRS

sample eventuallywere

placed on theNPL.

Thisnumber

exceedsthe

400

sitesthat Congresssetasanexplicit goal,because,aswe

havediscussed,some

sites withinitial scores

below

28.5were

rescored and then received scoresabove

the threshold.Most

of thissiteswherethe

EPA

declaredremediationtobe completeatalloperatingunits."

We

measureactual costasthesum

ofgovernment outlaysandestimates ofthecostsoftheremediationthatwerepaid for by non-governmentalresponsible parties across. The actual outlaysby theseparties are unavailabletothe public and the EPA, so these parties' estimated outlays

come

fromEPA

engineers' estimates of the costs of completingtherequiredremediation. SeetheDataAppendix forfurther details. ProbstandKonisky (2001) provide acomprehensive accounting ofpastcostsonSuperfundremediationsanddetailed projectionsaboutfuture costs.'^

Federal facilities wereprohibited from inclusion on the

NPL

until 1984. Consequently, the 1982HRS

sample doesnot containanyfederalfacilities.rescoring occurred in the 1986-1989 period. Panel

B

providesmean

HRS

scores, conditioned on scoresabove

andbelow

28.5. Notably,themeans

aresimilar across thecolumns.Panel

C

reportson

the size ofthe hazardous waste sitesmeasured

in acres. This variable is onlyavailable for

NPL

sites since it is derived from theRODs.

In the three columns, themedian

site sizeranges

between

25 and 35 acres.The means

are substantially larger dueto afew

very large sites.The

modest

size ofmost

sites suggests that any expected effectson

property valuesmay

be confined torelativelysmallgeographicareas.

Panel

D

provides evidence on the timerequired for the achievement ofthe clean-up milestones.The

median

time until the different milestones are achieved is reported, rather than the mean, becausemany

sites havenotreached allofthe milestones yet.As

an example, only 16oftheNPL

sites incolumn

(2)receivedeithertheconstructioncomplete ordeleteddesignationby 1990. Thus,

when

we

measure

theeffect of

NPL

status on 1990 housing prices, this effect will almost entirely be driven by siteswhere

remediation activities are unfinished.

By

2000, thenumber

ofsites inthe construction complete/deletedcategoryinthis

column

had increased dramatically to 198. Incolumn

(1), thenumbers

ofsitesthatwere

constructioncomplete

by 2000

(1990)is478

(22).Panel

E

reportstheexpectedcosts ofclean-up forNPL

sites. This informationwas

obtainedfrom

the sites'

RODs

and provides ameasure

ofthe expected costs (2000 $'s) ofthe clean-up before anyremediation activities have begun."'

They

include all costs expected to be incurred during the activeclean-up phase, as well as the expected costs during the operation

and

maintenance phase that issubsequenttothe assignment oftheconstructioncomplete designation.

In the All

NPL

Sample, the estimated cost datais available for753 ofthe985

NPL

sites.The

mean

andmedian

expectedcosts of clean-upare $28.3 millionand

$11 million.The

largermean

reflectsthe high cost ofa

few

clean-ups—

for example, the 95"' percentile expectedcost is $89.6 million. In the1982

HRS

Sample

incolumn

(2),themean

andmedian

are$27.5 millionand

$15.0 million.The

final panel reports estimated and actual costs for thesubsample

ofconstruction complete^'

Allmonetaryfiguresarereportedin2000$'s,unlessotherwise noted.

'

sites

where

both costmeasures are available.To

the best of our knowledge, theestimatedand

actual costdata have not been brought together before.

The

conventionalwisdom

is that the actual costs greatlyexceed the estimated costsofclean-up, andthistable providesthe first opportunityto test this view.

The

data support the conventional

wisdom

as themean

actual costs are35%-55%

higher than themean

expectedcosts across the threecolumns.

The

findings aresimilarformedian

actual and expectedcosts.A

comparison ofcolumns

(2) and (3) across the panels reveals that the sites with and withoutcomplete housing price dataare similaron a

number

of dimensions. For example,themean

HRS

scoresconditional on scoring

above

and below 28.5 are remarkably similar. Further, themedian

sizeand

various cost variables are

comparable

inthetwo

columns. Consequently, itseems

reasonable toconcludethat the sites without complete housing price data are similar to the

column

(2) sites, suggesting thesubsequentresults

may

berepresentativeforthe entire 1982HRS

Sample.Additionally, the sites in

column

(1) are similarto the sites incolumn

(2) and(3) insizeand

thetwo

costvariables.The

mean

HRS

scoresare afew

points lower, butthis comparison is not meaningfulduetothechanges inthe testover timeandchanges in the

how

the scoringwas

conducted.''" Overall, thesimilarityofthe

column

(1)sites withtheothersitessuggeststhatitmay

bereasonabletoassume

thattheresultsfrom the application ofthe

HRS

researchdesigntothe 1982HRS

sampleare informativeabouttheeffectsofthe otherSuperfundclean-ups.

We

now

graphicallysummarize

some

other features ofthetwo

samples. Figure 1 displays thegeographicdistribution ofthe

985

hazardous wastesites in the AllNPL

Sample. There areNPL

sites in45 of the 48 continental states, demonstrating that Superfund is genuinely a national program.

The

highest proportion ofsites, however, is inthe Northeast and

Midwest

(i.e., the "Rust Belt") that reflectsthe historicalconcentrationof

heavy

industry inthese regions.Figures 2

A

and

2B

present the geographic distribution of the 1982HRS

sample. Figure2A

displays thedistributionofsiteswith 1982

HRS

scoresexceeding28.5, whilethose withscoresbelow

this'"

Furtheroncethe28.5 cut-offwasset,the

HRS

testerswereencouraged tominimizetestingcostsand simply determinewhetherasiteexceededthe threshold. Consequently,testersgenerally stopscoringpathways onceenoughpathwaysarescoredtoproduceascoreabovethe threshold.

threshold aredepictedin 2B.

The

sites in both categories arespreadthroughout the UnitedStates, but thebelow

28.5 sites are in fewer states. For example, there are not anybelow

28.5 sites in Minnesota,Florida, and Delaware.

The

unequal distribution of sites across the countiy in thesetwo

groups is apotential

problem

for identification in the presence of local shocks,which

are a major feature of thehousingmarket.

To

mitigateconcerns aboutthese shocks,we

emphasize

econometricmodels

that includestatefixedeffectsforchanges inhousingprices.

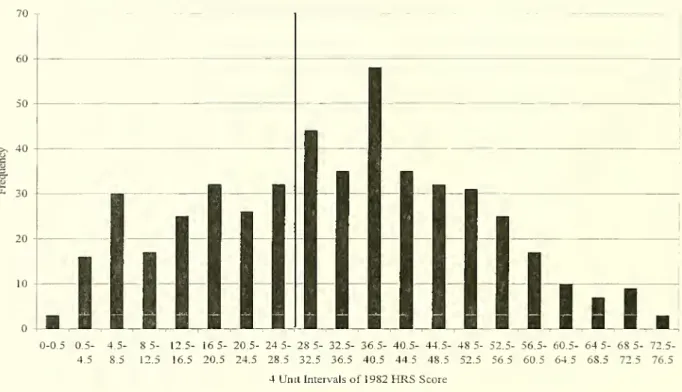

Figure 3 reports the distribution of

HRS

scoresamong

the487

sites in the 1982HRS

Sample.The

figure is a histogramwhere

the bins are 4HRS

points wide.The

distribution looks approximatelynormal, with the

modal

bin covering the 36.5-40.5 range. Importantly,227

sites haveHRS

scoresbetween

16.5and

40.5. Thissetiscenteredonthe regulatory thresholdof28.5 thatdetermines placementon the

NPL

andconstitutestheregression discontinuitysamplethatwe

exploit inthesubsequent analysis.Figure4 plotsthe

mean

estimated costsof remediation by 4-unit intervals (solid line), along withthe fractionofsitesin each interval withnon-missingcostdata (dotted line).

The

vertical linedenotesthe28.5 threshold.

The

non-zeromean

costsbelow

thethreshold are calculatedfrom

the sitesthatreceived ascore greater than 28.5

upon

rescoring and latermade

it onto theNPL.

The

estimated costs ofremediation appear to be increasing in the

HRS

score. This finding suggests that despite its widelyacknowledged

noisiness, the 1982HRS

scoresmay

be informative about relative risks. In theneighborhood of28.5,however, estimated costs areroughly constant,providing

some

evidencethatrisksareroughlyequal

among

thesites inthe regressiondiscontinuitysample.IV.

Econometric

Methods

A.LeastSquares Estimation with

Data from

the Entire U.S.Here,

we

discuss a conventional econometric approach to estimating the relationshipbetween

housingprices

and

NPL

listing. This approachis laidout inthe followingsystem ofequations:(7) yc2000

~

1(l^PLc200o)+

Xcl98o'P+

Ec2000,(8) 1(NPLc2000)

=

Xci98o'n+

ric2000,where

yc2ooo is the log of themedian

property value in census tract c in 2000.The

indicatorvariable l(NPLc2ooo) equals 1 only forobservations from census tractsthat contain ahazardous waste site

that has been placed on the

NPL

by 2000. Thus, this variable takes on a value of 1 forany

oftheSuperfund sites in

column

(1)ofTable 1, notjustthosethatwere

onthe initialNPL

list.The

vectorXci98oincludes determinants of housing prices

measured

in 1980, and Ec2oooand

ric2ooo are the unobservabiedeterminants of housing prices and

NPL

status, respectively.We

are also interested inthe effect ofNPL

statusin 1990,andtheyear 1990versionsoftheseequations aredirectlyanalogous.

A

few

features oftheX

vector are noteworthy. First,we

restrictthis vectorto 1980 valuesofthevariables to avoid confounding the effectof

NPL

status with "post-treatment" changes in these variablesthat

may

be due toNPL

status. Second,we

include the 1980

value ofthe dependent variable, ycso inXci98o, to adjust for permanent differences in housing prices across tracts and the possibility of

mean

reversionin housingprices. Seethe

Data

Appendix

forthefullsetofcovariates.Third in

many

applications ofRosen's model, the vector ofcontrols,denoted by X, is limited tohousing

and

neighborhood characteristics (e.g.,number

ofbedrooms, school quality, and air quality).Income

and other similar variables are generally excluded onthegrounds thatthey are"demand

shifters"andare

needed

toobtain consistent estimatesoftheMWTP

function.The

exclusion restrictionis invalidhowever

ifindividualstreatwealthy neighbors asan amenity (or disamenity). In thesubsequent analysis,we

are agnostic aboutwhich

variables belong in theX

vector and report estimates that are adjusted fordifferentcombinationsofthe variables available inthe

Census

data.The

coefficient 6 measurestheeffectofNPL

status on2000

property values aftercontrolling for1980

mean

property values and the other covariates. Ittests for differential housing price appreciation incensus tracts with sites placedon the

NPL.

Ifthere areunobservedpermanent

or transitory determinantsof housing prices that covary with

NPL

status,thenthe leastsquares estimator of9 will be biased.More

formally, consistent estimation of6 requires E[ec2oooTlc2ooo]

=

0.To

account for local shocks to housingmarkets,

we

emphasizeresultsfrom specificationsthatinclude afijll setofstatefixedeffects.Ultimately, theconventionalapproach described in thissubsectionrelies on a

comparison

ofNPL

sitesto the rest ofthe country. Its validity rests on the assumptionthat linearadjustment controls for all

determinants of housing price growth

between

census tracts with and without aNPL

site, besides theeffectofthesite'splacement onthe

NPL.

B.

A

Quasi-ExperimentalApproach based on

the1982

HRS

ResearchDesignHere,

we

discuss our preferred identification strategy that hastwo

Icey differences with theone

described above. First,

we

limit thesample

to the subset of census tracts containing the487

sites thatwere

considered for placementon

the initialNPL

and have complete housing price data. Thus, allobservations are

from

censustracts with hazardous wastesites thatwere

judged to beamong

the nation'smost

dangerous by theEPA

in 1982. If, for example, the P's differ across tracts with and withouthazardous waste sites or there are differential trends in housing prices in tracts with and without these

sites, thenthis approach is

more

likely toproduce

consistent estimates. Second,we

use atwo-stageleastsquares

(2SLS)

strategytoaccountforthepossibilityofendogenous

rescoringofsites.More

formally,we

replaceequation(8)with:(9) 1(NPLe2000)

=

Xcl980'n+

5 1(HRSc82>

28.5)+

TleZOOO,"

^

-where

I(HRSc82>

28.5) serves as an instrumental variable. This indicator function equals 1 for censustracts with a site that has a 1982

HRS

score exceeding the 28.5 threshold.We

then substitute thepredicted value ofl(NPLc2ooo)

from

theestimation ofequation (9) inthe fitting of(7) to obtain 92sls- Inthis

2SLS

framework, B2sls is identifiedfrom

the variation inNPL

status that is due to a site having a1982

HRS

scorethatexceeds28.5.For BjsLs to provide a consistent estimate ofthe

HPS

gradient, the instrumental variablemust

affect the probability of

NPL

listing, without having a direct effect on housing prices.The

next sectionwill demonstratethatthefirstcondition clearly holds.

The

secondcondition requiresthatthe unobserveddeterminants of

2000

housing prices are orthogonal tothe portion ofthenonlinear function ofthe 1982HRS

score that is not explainedby

Xcigso- In the simplest case, the2SLS

estimator is consistent ifE[l(HRSc82>28.5)e,2ooo]=0.

We

also obtain2SLS

estimates anotherway

that allows for the possibility that E[l(HRSc82>

28.5) ec2ooo] ^^ over the entire 1982

HRS

sample. In particular,we

exploit the regression discontinuitydesign implicit in the !(•) function that determines

NPL

eligibility in three separate ways. In the first.

'

approach, a quadratic in tlie 1982

HRS

score is included in Xcigso to partial out any correlationbetween

residual housingprices and the indicator fora 1982

HRS

score exceeding28.5. This approach does notrequirethatthedeterminantsof housingprices areconstant across therangeof 1982

HRS

scores. Instead,it relies on the plausible assumption that residual determinants of housing price growth do not

change

discontinuouslyat

HRS

scoresjustabove

28.5.The

second regression discontinuityapproach involves implementing our2SLS

estimator on theregression discontinuity

sample

of227

censustracts. Recall,thissample

is limitedtotractswithsitesthathave

1982HRS

scoresbetween

16.5 and 40.5. Here, the identifying assumption is that all else is heldequal in the "neighborhood" of the regulatory threshold.

More

formally, it is E[l(HRSc82>

28.5)£c2ooo|16.5

<

1982HRS

<

40.5]=

0. Recall, theHRS

score is a nonlinear function ofthe ground water,surface water, and air migration

pathway

scores.The

third regression discontinuitymethod

exploitsknowledge

ofthis function by including the individualpathway

scores in the vector Xdgso. All oftheseregression discontinuity approaches are

demanding

ofthe dataand

this will be reflected in the samplingerrors.

V. Empirical Results

A. Balancing

of

Observable CovariatesThis subsection

examines

the quality of the comparisons that underlie the subsequent leastsquaresand quasi-experimental

2SLS

estimatesoftheeffectofNPL

statuson housing price growth.We

beginby examining whether

NPL

status andthe l(HRSc82>

28.5) instrumental variable areorthogonaltotheobservablepredictorsof housingprices. Formal tests forthe presenceof omitted variables bias are as

always unavailable, but it

seems

reasonable topresume

thatresearch designs that balancethe observablecovariates across

NPL

status or l(HRSc82>

28.5)may

sufferfrom

smalleromitted variables bias. First,these designs

may

bemore

likely to balancethe unobservabies(Altonji, Elder, andTaber 2000).Second

ifthe observablesarebalanced, then consistent inferencedoes not

depend

onfunctional form assumptionsonthe relations betweenthe observable confounders

and

housingprices. Estimatorsthat misspecity' thesefunctional forms (e.g., linear regression adjustment