IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 181 More than WORDS. Semantic Continuity in Moving Images.

Janina Wildfeuer

Abstract

This article focuses on a linguistic analysis of the textual qualities of coherence and structure in a short film named WORDS, available online on vimeo.com. The analytical framework chosen for the analysis is the so-called logic of film discourse interpretation which has recently been developed as a new tool for film analysis that takes into account the recipient’s inferential meaning-making on the basis of explicit textual cues in the filmic discourse. The article will elucidate how this framework works and how meaning construction in multimodal filmic discourse can be described with the help of a formal, logical tool and on the basis of defeasible reasoning.

Résumé

L’article se concentre sur une analyse linguistique des qualités textuelles de la cohérence et structure dans le court métrage WORDS, mis en ligne à vimeo.com. L’instrument analytique choisi pour l’analyse est la logique de l’interprétation du discours filmique qui a été proposée récemment comme un nouvel outil pour l’analyse du film et qui prend en considération la construction du sens causée par les inférences du récipient en vertu des indications textuelles dans le discours filmique. L’article va démontrer comment l’outil fonctionne et comment il est possible de décrire la construction du sens dans le discours multimodal à l’aide d’un instrument formel et logique qui considère l’argumentation contestable du récipient.

Keywords: multimodal film analysis, logic of discourse interpretation, semantic continuity

1 Introduction

One of the main questions in contemporary film theory and analysis is how films mean and how it is possible to make sense of the various resources operating together in multimodal combination. Meaning in film, as is commonly assumed, arises out of the dynamic interplay of images, sounds, gestures, music, etc. and has to be inferred by the recipient with the help of world knowledge and reasoning about the best interpretation (cf. Bordwell 1985, Bordwell 1989, O’Halloran 2004). How

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 182 this inference-making process can be made visible in terms of the construction of filmic narrative will be examined in the following. According to David Bordwell, narrative comprehension is a matter of an experiential logic that guides and prompts the viewer and affects and constrains his/her inferential reasoning (cf. Bordwell 2008, p. 98).

“In watching a film, the perceiver identifies certain cues which prompt her to execute many inferential activities — ranging from the mandatory and very fast activity of perceiving apparent motion, through the more “cognitively penetrable” process of constructing, say, links between scenes, to the still more open process of ascribing abstract meanings to the film. In most cases, the spectator applies knowledge structures to cues which she identifies within the film.” (Bordwell 1985, p. 34)

This article wants to elaborate exactly on these textual cues which are responsible within the process of film interpretation. The example to be analysed will be a short film that, at first sight, does not seem to be highly coherent or narrative: WORDS, published online on the video platform Vimeo (http://vimeo.com) in 2010. At present, short films like WORDS are very popular and much valued film forms found mostly on the Internet. Most of them represent a cut-together of different film scenes or give a synopsis of still images that are connected by a specific sound track. They do not often have a length of more than two or three minutes and do not contain an overall narration or a coherent figuration, but are nevertheless enjoyable and entertaining.

How recipients can make sense of the intersemiotic interplay of the various resources used in this film will be examined in this article. The analytical perspective taken for a comprehensive examination is the film as discourse-perspective pursued within contemporary multimodal film analysis (cf. van Leeuwen 1991, 1996, O’Halloran 2004, Bateman 2007, Tseng 2009, Bateman and Schmidt 2011, Wildfeuer 2012). This notion of film as text or discourse is a new starting point of investigation today. It combines traditional accounts of film interpretation with modern linguistic analyses of meaning construction in multimodal texts and puts forward the notion of inference and abductive reasoning as the main matter of interest in this analysis. With regard to basic textual qualities such as coherence and structure, it makes possible to point out exactly and in particular systematically how the discursive meaning can be constructed because of links and connections between entities in the text.

For a comprehensive analysis of these qualities, Wildfeuer (2012) provides the logic of film discourse

interpretation as a framework which takes inferential strategies and defeasible reasoning as a

fundament for making meaning, but, at the same time, offers distinct constraints to control the interpretation. This framework provides a method for constructing the discursive structure of the filmic text by describing a set of film discourse relations that can be inferred between the events of a filmic discourse. With the help of clear meaning postulates and default axioms that define and constrain the inference of the relations and the conditions that must hold within the context, it is possible to reproduce the recipient’s interpretation process in a more formal and systematic way.

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 183 The analysis of the short film WORDS in the following will give a concrete example of how these discourse relations act as mediators that guide hypothesis construction by filling in gaps of underspecified information (cf. Bateman and Schmidt 2011). The result of the analysis will then depict the coherent structure of the filmic text and will give an overview of how meaning can be constructed within this text.

2 Semantic Continuity in Words

The short film WORDS was produced by Will Hoffman, Daniel Mercadante and Julius Metoyer, who represent the production company Everynone. It was first published in July 2010 and is still available online on vimeo.com.1 The film depicts a sequence of at first sight unconnected shots accompanied by a continuous soundtrack and a synchronously inserted audio track. How it is possible to make sense of this sequence of images and sounds and to create a coherent structure of the filmic text by means of film discourse relations will be elucidated in the following.2

2.1 Relational Meaning-Making in WORDS: Some Examples

The film starts with the insert of the title on a black background. The following shot is a close-up of a recorder whose play button is pressed. Music starts and the image cuts to an image of a theatre stage where two persons are playing in the spotlight. A shot of two children running around on a playground outside follows. The next shot depicts a meeting situation where members of a football team are sitting in front of a board. The next medium close-up shows the drawings on the board while planning a new play. A cut to another scene depicts a baseball coach shouting “Play ball!” The next shot represents a man playing the trumpet; the following close-up of his mouth blowing into the trumpet is immediately cut to another scene where a man blows out candles on a cake. An image of a ventilator blowing slips of paper on a table and a shot showing a bank note blown across a street follow. The continuing music is calm piano and guitar playing, at times supported by a synthesiser. These first 28 seconds of the film are transcribed in table 1.

# shot shot description audio track spoken

language music 1 title “WORDS” on black background / / / 2 close-up of recorder buttons, “play” is pressed sound of pressing the button / calm music starts after the play-button is

pressed

1

http://vimeo.com/13768695 (accessed September 4, 2012)

2

The analysis is partly taken from the methodological chapter in Wildfeuer (2012, p.66-77), but will contain more examples and a more detailed description of the film’s structure. A complete transcription of the film is given in the appendix of this article.

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 184 3

a theatre stage, two persons playing in

the front

sound of batting

staves /

calm piano and guitar music

4 two girls in a

play-ground outside

sound of

children at play /

calm piano and guitar music

5

a football team planning a new

play

/ “Here, the back is coming off.”

calm piano and guitar music

6

close-up of a board in the meeting

situation

/ “Here, the end is pitching.”

calm piano and guitar music

7 a man with helmet

and facemask / “Play ball!”

calm piano and guitar music

8 a man sounding the

trumpet trumpet play /

calm piano and guitar music

9

close-up of the man’s mouth blowing into the

trumpet

sound of

blowing heavily /

calm piano and guitar music

10 a man blowing out

candles on a cake

sound of

blowing out /

calm piano and guitar music 11 a ventilator blowing away some papers sound of ventilator and the flying paper

/ calm piano and guitar music

12 a bank note on the

street

noises from

outside (cars) /

calm piano and guitar music Table 1: Transcription of the first 28 seconds of the short film WORDS

As the title implies, each image or scene is associated with a particular word that can be interpreted by the recipient. The overall proposition for the first eight shots, for example, is ‘play’. Whereas this is written on the play button in shot 2 and is therefore constructed by written language in the shot, the next four shots (3–6) do not contain any verbal information associated with this word. Shot 7 then depicts a person normally associated with a baseball player or coach. Here, it is the audio track, in particular the spoken language (“Play ball!”) which actualises the proposition.

The words predicted by the title are thus in the majority of cases not explicitly mentioned, neither through spoken nor written language. They can solely be interpreted by analysing the meaning-making potential of the images and the additional information in the voice track. Consequently, this is a

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 185 multimodal meaning construction and it is clearly necessary to consult the interplay of the different modalities for the interpretation. For instance, shot 58, which shows two men at weight lifting, does not have any visual coherence to the shot of the feather before (57). Instead, it is the voice track (“Light as a feather…”) which is directly connected to the image. The conjunction is thus realised cross-modally (see table 2).

In fact, it is necessary to take the whole context into consideration to infer how the particular shots represent the respective predicates. In the sequence depicted in table 2 it becomes apparent that the conjunction between shot 57 and the voice track in 58 is indeed available, but does not influence the following shot (59). It is the word “light” which is decisive for the interpretation of the following image of the shining sun. The proposition ‘light’ comes to the fore and is realised by the following shots. The voice track in shot 62 then finally specifies it: “Let there be light!”

# shot shot description audio track spoken

language music

57 a feather in the air /

“Light as a feather, come

on!”

calm piano and guitar music

58 two men at weight

lifting /

“Aaaah…Light as a feather…”

calm piano and guitar music

59 shining sun / / calm piano and

guitar music Table 2: Extract of the transcription of the short film WORDS

A similar process is observable in shot 9 which shows a close-up of the trumpeter seen in shot 8 before. His trumpet playing is thus depicted in more detail and can be associated with the proposition of the preceding shots: ‘play’. However, the next shots, shot 10 and following, introduce a new predicate which has not been displayed before: ‘blow’. There is thus also a direct link between the close-up of the trumpeter who is blowing into his trumpet and the person blowing out candles in the following shot, so that the former image can retrospectively be associated with the predicate ‘blow’ as well. This is the so-called Context Change Potential that has been analysed in detail within recent works in discourse analysis (cf. Hobbs 1990, Asher and Lascarides 2003, p. 42). It is assumed in these works that meaning in discourse always has to be examined with regard to the context and further information added to this discourse that may change the preceding interpretation. This is the case in the present example, since the new information given by the following shots change the overall context and influence the interpretation of the multimodal composition. The dynamicity of the unfolding discourse has thus to be taken into account within the description of the interpretation process. How this change can be described in a more formal way will be carried out in more detail

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 186 below.

The same principle applies for further shots in the film, such as the scene in which a man and a woman are sitting on a bed, not talking to each other. The images before and after (see table 3) can all be associated with the predicate ‘break’ (or its phonologically similar counterpart ‘brake’ as depicted in shot 24).

Inferring that the two persons are representing a couple, it is possible to associate the situation of breaking off their relationship and thus to connect the image with the predicate ‘break’. The interpretation can mainly be based on the gestures and facial expressions of the persons in the image, but there is, for example, no influencing voice track. Since it is only the continuing sound track which accompanies the whole sequence of shots, the silence between the two persons is also a crucial factor for the interpretation. Additionally, adequate language skills are necessary to associate the particular vocabulary used.3

# shot shot description audio track spoken

language music

26 a man shouting into

his cellular phone /

“You’re breaking up, man, I can’t hear you!”

calm piano and guitar music

27

a man and a woman sitting on a

bed, heads downs

/ / calm piano and

guitar music

28 a man hitting a TV

with a bat sound of batting /

calm piano and guitar music Table 3: Extract of the transcription of the short film WORDS

2.2 Constructing the Discourse Structure of WORDS

Since it is possible to associate every shot with words that summarise and conclude the different situations which are at first sight not directly related to each other, the film as a whole emerges as a coherent text whose meaning potential is identifiable by the recipient. The continuous sound track and the cross-modal realisation of meaning in some cases support the high density of relationships. Although the film does not have a clear narration or a definite figuration, it is a coherent text that ‘makes sense’. In the following, the interpretation processes which operate during the film’s reception

3

These language skills are necessary for the interpretation of some idiomatic expressions such as, for example, the description of shot 40 (see the transcription in the appendix), which can be associated with “to run a red light”. The same principle applies to the specific vocabulary of, for example, bowling or billiards. Without these language skills, it might be more difficult to associate every shot with the respective proposition. However, as further analysis will demonstrate, it is possible to interpret the coherent discourse structure. The text thus also makes sense, when two or three propositions cannot be found at first sight.

Furthermore, the possibility to watch the film repeatedly on the Internet allows to reconsider the interpretation and to find some more propositions and relationships between the various shots.

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 187 will be outlined in more detail and with the help of the analytical tool of the logic of film discourse

interpretation. It will help to describe the inference process which depends on different knowledge

sources. It will then be possible to depict how meaning construction in this example takes place. The interpretation of the beginning of the film, as given in table 1, can for example be described more formally in the graphical representation of the film’s discourse structure in figure 1.

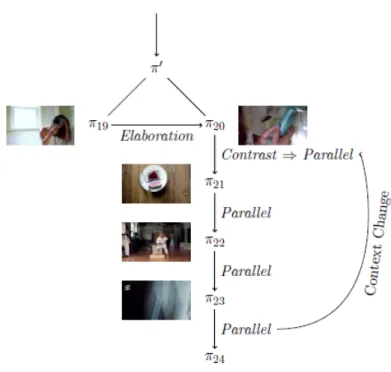

Figure 1: Graphical representation of the discourse structure of the first shots of WORDS

Since the film contains a sequence of very different shots, every shot is described in this figure by a label 𝜋𝑛 representing a single discourse segment. 𝜋1, for example, represents the shot of the play button which is pressed by an unknown actor. Each discourse segment can be interpreted as a so-called eventuality which is assumed to be normally inferred by the recipient by combining the meaning potential of the modalities within the shots. The eventuality of 𝜋1 can be interpreted as the proposition ‘play’. This inference is possible because of the explicit specification of the proposition within the shot, written on the button. The following shots are also interpreted and associated with this proposition, since they all depict the action process of ‘playing’, as for example given by the two

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 188 children on the playground in 𝜋3 or the person playing the trumpet in 𝜋6. Whereas the non-transactional process in shot 2 is dominated by the close-up focussing on the play-button, the bi-directional process in shot 3 connects the two unknown actors and dominates the inference process that leads to the predicate ‘play’.4

Since the first six discourse segments can be compared to each other by their semantic similarity, they are related via Parallel-relations. The relations hold because of the common theme between the segments; they all depict the activity of playing. This common theme is the condition that must hold for the inference of the discourse relation, as generally defined in Wildfeuer (2012, p. 93f.). In the present example, the association given to the theatre play in shot 3 (𝜋2) describes an event which can be formulated relatively similarly to the event depicted in shot 2. The relation between the two segments thus fulfils the default axiom defined for Parallel, given in the following and defined by Wildfeuer (2012).

�? (𝛼, 𝛽, 𝜆) ∧ 𝑠𝑒𝑚𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑐 𝑠𝑖𝑚𝑖𝑙𝑎𝑟𝑖𝑡𝑦 (𝛼, 𝛽)� > 𝑃𝑎𝑟𝑎𝑙𝑙𝑒𝑙 (𝛼, 𝛽, 𝜆)

In this case, the eventualities 𝜋1 and 𝜋2) replace the variables 𝛼 and 𝛽 in the discourse context labelled 𝜆, so that the logical formula can be rewritten as follows:

�? �𝑒𝜋1, 𝑒𝜋2, 𝜆� ∧ 𝑠𝑒𝑚𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑐 𝑠𝑖𝑚𝑖𝑙𝑎𝑟𝑖𝑡𝑦 �𝑒𝜋1, 𝑒𝜋2�� > 𝑃𝑎𝑟𝑎𝑙𝑙𝑒𝑙 �𝑒𝜋1, 𝑒𝜋2�

This relation is the most preferred connection between the discourse segments, since no other default axiom can be fulfilled by the context. Since the shots differ from each other in basic characteristics, such as time and space and their figuration, they can only be related to each other via a text-structuring relation such as Parallel which requires similarity only on a higher level of description. This similarity holds for the segments 𝜋1− 𝜋6 as well as 𝜋7 which shows again the trumpeter. However, the transition between 𝜋6 and 𝜋7 is marked by another discourse relation in figure 1. There is thus a change within the filmic discourse which influences the interpretation.

In the case of 𝜋6 and 𝜋7, it is the granularity of description that changes because of the zoomed depiction of the trumpeter in 𝜋7. Whereas the transitions between the other shots always show completely different settings and characters, the change here is only given by the camera perspective. The second shot, 𝜋7, is a close-up of the trumpeter’s mouth showing him blowing into the trumpet. The function of this close-up thus is different to the relations between the preceding shots, namely focussing on a small aspect within the image and specifying the description. The relation which holds between the two elements is thus an Elaboration-relation. The default axiom which is fulfilled is the following:

�? (𝜋6, 𝜋7, 𝜆) ∧ 𝑠𝑝𝑒𝑐𝑖𝑓𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 (𝜋6, 𝜋7)� > 𝐸𝑙𝑎𝑏𝑜𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 (𝜋6, 𝜋7, 𝜆)

4 Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) provide these descriptions of processes for images in their work Reading Images. The Grammar of Visual Design.

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 189 In the example, the specification is realised by the zoom-effect arranged on the visual level. Consequently, in the following, the focus lies on the process depicted in the second shot. This focus has a special function within the unfolding discourse, since it depicts a change in the chain of propositions which can be inferred from the shots. For 𝜋7, it can already be assumed that the predicate associated with this shot is no longer ‘play’, but that the focus now lies on the process of blowing. This assumption can be supported by the following shots, which all can be associated with this predicate (see table 1). It is thus the following context of the unfolding discourse which makes clear that ‘blow’ now becomes the dominant predicate and establishes again a sequence of Parallel -relations.

The input-context of the unfolding discourse has consequently been changed by the so-called Context Change Potential (Asher and Lascarides 2003, Wildfeuer 2012) and the process of discourse update makes it possible to find connections between the contrasting discourse segments. It can be recognised that the zoomed image of the trumpeter depicts the transition to another sequence of parallels. This transition itself is textually realised by an Elaboration-relation, which explicitly focuses on the change. The process of discourse update and the Context Change Potential are graphically represented in figure 2.

Figure 2: Second graphical representation of shots 10-13 of WORDS

It becomes visible that the interpretation of the contrast between the process of playing and blowing is compensated by the following context which makes clear that there are again Parallel-relations holding between the segments. These relations are text-structuring relations that entail that the structure of the particular constituents as well as their semantic content is similar. This is the case for nearly all discourse relations holding between the discourse segments. The connections that can be

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 190 drawn between the different shots are all based on similarities between the action processes depicted. Only the Elaboration-relation in the example described above has another function, namely that of providing additional content which then, as a consequence, supports the transition between the predicate sequences.

This is also the case in the following extract. In the sequence of shots 18–20, there is a further discourse relation that functions similarly to the Elaboration-relation described for the first transition (see table 4).

# shot shot description audio track spoken

language music

18

a woman drying her hair until the blower stops

the sound of a

hair blower /

calm piano and guitar music

19 close-up of the hair

blower clicking /

calm piano and guitar music 20 a plate falling down, breaking into pieces sound of breaking porcelain

/ calm piano and guitar music Table 4: Extract of the transcription of the short film WORDS

The zoomed image in shot 19 focuses on the hair blower which stops working in the shot before. This focus supports again the inference that there is a change in the propositional content. Similar to the transition before, this focus is related to the preceding shot via an Elaboration-relation that gives more information and specifies the description of the image. Shot 20 then shows a plate falling down and breaking into pieces. Consequently, the association is drawn between the break of the hair blower and the process of breaking into pieces. In contrast to the proposition ‘blow’ in the preceding shots, it can now be inferred that ‘break’ is the dominant association in the following. This is furthermore supported by the next shots and their action processes. A graphical representation of the discourse structure of these shots is given in figure 3.

It becomes visible again that most of the relations between the discourse segments are Parallel-relations and that the inference of the Contrast-relation is again updated by the following discourse. The interpretation of the Parallel-relations is based on the semantic similarity between the shots and their action processes.

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 191 Figure 3: Third graphical representation of the discourse structure of WORDS

In some cases, this interpretation needs further information sources, such as domain knowledge, which makes it possible, for example, to describe and associate the first hit in a snooker game, as depicted in shot 25, with the sequence of images with the same proposition. The association with the predicate ‘break’ can only be drawn when this knowledge is available for the recipient. However, since this shot is accompanied by further shots whose meaning potential can be inferred more easily, it is assumed that the action process depicted in shot 25 will be inferred similarly.

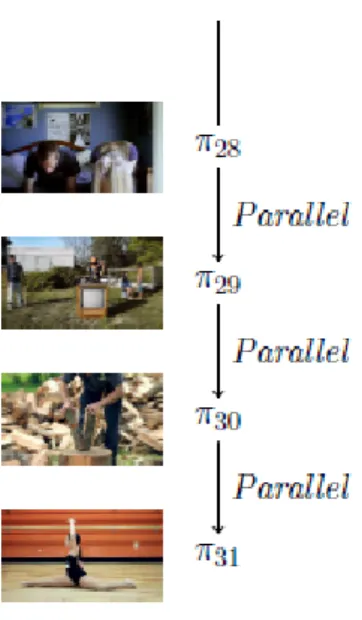

Another kind of transition between predicate sequences is given in shot 28 in which a main hits a TV with a bat. This process can still be inferred as ‘breaking’ and therefore associated with the preceding shots via a Parallel-relation. The following shot 29 shows a man choping wood which is followed by an image of a young girl doing the splits. It is inferred that there is again a transition to another predicate which can also be associated with the following shots. Whereas shot 28 still resembles the process of breaking, shot 29 can rather be associated with the predicate ‘split’. However, there is no explicit indication of the transition nor a further discourse relation that focuses on a change in the sequence. Instead, all shots here are related to each other via Parallel-relations and it is only the predicate itself that changes (see figure 4).

In this example, it is the action process in both images which fulfils the condition for inferring a

Parallel-relation. Furthermore, the setting and the characters in the shots resemble each other,

although they do not depict the same scene. Consequently, both shots can be associated with a similar action process and it is again the following context that specifies the transition, which, in this case, cannot be made visible by the discourse structure itself.

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 192 Figure 4: Fourth graphical representation of the discourse structure of WORDS

The coherence of the various extracts and the overall discourse is thus continuously constructed by

Parallel-relations which all are based on the semantic similarity of the shots and their events. There is

no single Narration-relation in this film, which, for example, requires a spatiotemporal consequence or a coherent figuration (cf. Wildfeuer 2012, p. 92ff.). All the characters in this film appear only once and the overall similarity and parallelisms are mainly constructed because of the abstract interpretation that can be inferred from the action processes shown in the images.

However, the similarity is not only given on the visual level of description, but it is also realised by the audio track, for instance. In the sequence of shots which can all be associated with the predicate ‘fall’, for example (see table 5), shot 52 shows a TV in a sleeping room that displays an old woman lying on the floor.

# shot shot description audio track spoken

language music

51 a man falling down

the stairs

sound of

thunking /

calm piano and guitar music

52

TV in sleeping room showing an old woman on the

floor

/ “I’m falling and I…”

calm piano and guitar music

53 a waterfall

sound of waterfall outside

/ calm piano and guitar music Table 5: Extract of the transcription of the short film WORDS

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 193 The voice track which is audible in this shot can be attributed to this woman saying “I’m falling...”. It is thus only the voice track which makes it possible to associate the shot with the preceding ones and the dominant predicate in this context. The visual description does not feature any similarities to the preceding action processes. This example makes visible not only the multimodal, but also intersemiotic meaning construction within filmic discourse. Only the interplay of the semiotic resources here enables the interpretation of the discourse relation and therefore the construction of the discourse structure and the film’s overall coherence. Furthermore, it becomes clear that the context again influences the interpretation. If the preceding shots did not create the association with the predicate ‘fall’, the voice track in shot 52 would probably not be interpreted as the important resource here.

The parallelisms between the shots can be inferred until the film’s ending in shot 67 which depicts again a parallel to the preceding shots and, furthermore, to the beginning of the film. The close-up of the space bar which is pressed by an unknown actor constructs a direct parallel to the first shot of the play button and therefore completes the sequence of shots by an implicit closing of the playing. A black screen and some credits follow, but do not hold any semantic similarities to the preceding shots. On the basis of our general film knowledge, it can be inferred that the end titles do not constitute a breach within the film and therefore do not influence the overall coherence of the filmic discourse.

2.3 Summary of the Analysis

The graphical representations in the preceding section depict the unfolding discourse structure of the short film and therefore represent a syntagmatic articulation of a selection of film discourse relations which could be inferred because of the meaning potential of the shots and the contextual information available. Based on the default axioms given for each relation, it could have been shown how the recipient infers the coherence of the filmic discourse and how this discourse makes sense, although it does not feature a coherent figuration or narration. It was furthermore possible to outline in detail how the recipient’s inference process is guided by the so-called textual cues which, for example, explicitly mark a transition between predicate sequences.

It is thus possible to describe how meaning in this filmic discourse is constructed on the basis of the multimodal and intersemiotic interplay of the resources and at the same time to examine how this meaning construction is constrained by explicit references in the text. However, these constraints are not available within the whole text, as has been pointed out in the example of the transition between the predicates ‘break’ and ‘split’. The text gives no definite indication of the transition and it is only the context which makes clear that there is a change in the description and association of the images. Consequently, meaning construction during the interpretation of this short film takes place as both a bottom-up as well as a top-down process in constructing the meaning potential of the filmic devices with regard to their intersemiosis and in taking general world and film knowledge as a further basis for

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 194 relating the elements to each other. It is thus exactly the process of “furnish[ing] the materials out of which inferential processes of perception and cognition build meanings.” (Bordwell 1989, p. 3) As has become clear during the analysis, this process is a dynamic one which is influenced by the unfolding discourse context that changes the interpretation during discourse update. The result of this interpretation is the description of the overall discourse structure and the film’s coherence. This coherence is based on nine different predicates which can be inferred from the multimodal composition of the filmic entities: play – blow – break – split – run – fly – fall – light – space. This sequence of predicates makes it possible to describe the abstract meaning potential of the filmic discourse and at the same time to construct its thematic structure.

3 Conclusion

In contrast to films with a coherent narration and figuration, WORDS does not create spatiotemporal consequences on a specific diegetic level nor does it construct causal relationships between its constituents. It is thus not a typical narrative film that is based on the so-called narrative logic which “depends upon story events and causal relations and parallelisms among them” (Bordwell 1985, p. 6). Nevertheless, the filmic discourse constructs a specific path that the recipient chooses by relating the various discourse segments to each other and by inferring the sequence of predicates described above. This specific path could have been reproduced by outlining the unfolding of the film’s discourse structure with the set of relations provided within the logic of film discourse interpretation.

It can therefore be summarised that the parallelisms found in the discourse structure of WORDS depict as well a kind of textual logic that enables the viewer to interpret the film and construct its overall coherence. Based on the logical principles provided for the set of film discourse relations in Wildfeuer (2012), which represent essential principles of understanding and making meaning, it is possible to describe in detail how the film makes sense without any coherent narration, but on the basis of our general knowledge of the world. It is thus not an explicitly narrative logic that governs the interpretation process and that is normally assumed for filmic discourse. However, the textual principles and qualities operating in the short film WORDS make it also possible to connect the various discourse segments to each other and to construct at least the topic structure of the text.

As indicated in the introduction, these types of short films are very popular at the moment and are mostly found on the Internet, provided on video platforms such as YouTube or Vimeo. It is assumed that they represent a new form of video production that uses various film sequences and different images to create meaningful texts which do not tell a single story or describe a specific topic, but entertain differently. They describe common events, emotional situations or enjoyable incidents people experience in their daily life and which they want to share with others. A very popular and recent example for this new film genre is the movie LIFE IN A DAY which has been produced by filmmakers all over the world. The film depicts a series of video clips that have been submitted to the

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 195 YouTube website as a reaction to a call for videos recorded on July 24, 2010. It is a result of a selection from 4,500 hours of video material from more than 190 nations.5 Although the arrangement of the various clips starts with the description of the morning routine of several characters and then follows the course of the day, there is no single story told by the images. Various characters are depicted at different settings and without any specific commonalities in their actions or dialogues. Nevertheless, the film is coherent and makes sense, since its discourse segments are related to each other by logical principles such as parallelisms, contrasts or, in some rare cases, causal relationships. The construction of the film’s meaning potential thus resembles the principles used in the composition of the short film WORDS.

This composition aims at a semantic continuity between the various filmic elements which is simply based on qualities such as similarity or parallelism. These qualities are governed by the basic principles of coherence and structure in order to construct the film’s meaning potential. In contrast to verbal discourses whose meaning construction is often based on a single semiotic resource such as the written language, the cross-modal patterns transcending the duality of visual and auditory modalities in this example film represent a specificity which accounts for the distinctiveness of these types of films. Whereas typical narrative films contain a story and figuration whose interpretation is possible because of spatiotemporal and causal relationships holding within the discourse, the interpretation of WORDS depends nearly exclusively on text structuring principles of the discourse which could be described in the analysis. However, these principles also lead to a coherent text with a topic structure that is comparable to that of a narrative discourse.

The difference between this short film and typical narrative films thus lies in the textual composition of the film. With regard to the construction of the film’s coherence, the variety of discourse relations found in the analysis is not as diverse as it could be for narrative texts in general. The set of relations provided within the logic of film discourse interpretation contains a few more relations that can be found in filmic discourse, as described and analysed in more detail in Wildfeuer (2012).6 These relations support for example the unfolding of the diegetic content and do not only refer to the textual arrangement of the discourse segments. In the short film WORDS, this is only the case for the few

Elaboration-relations that function as a kind of specification of the semantic content and therefore do

not operate similarly to the Parallel-relations. With the help of the framework of the logic of film

discourse interpretation, it has been possible to examine this specific textual composition of the short

film and to outline how the recipient can make sense of this exceptional interplay of the semiotic resources. In a further step, this analysis may also help to ask questions concerning genre specificities or narratological problems, but which definitely need further empirical analysis of these film types. As a first detailed description of how meaning in these films can be interpreted, the analysis proves the need for a systematic approach to film analysis in order to be able to work out the differences of

5 See http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1687247/.

6 The set contains the following seven film discourse relations: Narration, Elaboration, Explanation, Result, Background, Parallel and Contrast (cf. Wildfeuer 2012, p. 92ff.).

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 196 several film genres in more detail and to examine their multimodal narrative or non-narrative meaning construction.

Works Cited

Asher, Nicolas and Lascarides, Alex. Logics of Conversation. Cambridge University Press, 2003. Bateman, John. “Towards a Grande Paradigmatique of Film: Christian Metz reloaded.” Semiotica 167.1/4 (2007): 13–64.

Bateman, John A. and Schmidt, Karl-Heinrich. Multimodal Film Analysis: How Films Mean. Routledge, 2011.

Bazin, André. What is Cinema. André Bazin. Essays selected and translated by Hugh Gray. University of California Press, 1967.

Bordwell, David. Narration in the Fiction Film. Routledge, 1985.

Bordwell, David. Making Meaning. Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema. Harvard University Press, 1989.

Bordwell, David. Poetics of Cinema. Taylor & Francis Group, 2008.

Bordwell, David and Thompson, Kristin. Film Art: An Introduction. McGraw Hill, 2001. Hobbs, Jerry R. Literature and Cognition. Lecture Notes, 1990.

Kress, Gunther and van Leeuwen, Theo. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. Routledge, 1996.

Martin, J.R. and Rose, David. Working with Discourse: Meaning beyond the Clause. Continuum, 2003.

O’Halloran, K. “Visual Semiosis in Film.” Multimodal Discourse Analysis: Systemic Functional

Perspectives. ed. Kay O’Halloran. Continuum, 2004. 109–130.

Peirce, Charles S., Hartshorne, Charles, and Weiss, Paul. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1979.

Tseng, Chiaoi. Cohesion in Film and the Construction of Filmic Thematic Configuration: A

Functional Perspective. Ph.D. thesis, University of Bremen, 2009.

van Leeuwen, Theo. “Conjunctive Structure in Documentary Film and Television.” Continuum 5.1 (1991): 76–114.

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 197 van Leeuwen, Theo. “Moving English: The Visual Language of Film.” Redesigning English – New

Texts, New Identities. ed. D. Goodman, S; Graddol. Routledge, 1996. 81–105.

Wildfeuer, Janina. Coherence in Film and the Construction of Logical Forms of Discourse: A

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 198 Appendix

WORDS (Everynone, 2010)

Short film directed by Daniel Mercadante and Will Hoffman. Available online, [URL:] http://vimeo.com/13768695 (accessed September 4, 2012).

# shot shot description audio track spoken

language music 1 title “WORDS” on black background / / 2 close-up of recorder buttons, “play” is pressed sound of pressing the button “/ music starts immediately after play-button is pressed 3

a theatre stage, two persons playing in

the front

sound of batting

staves /

calm piano and guitar music

4 two girls in a

playground outside

sound of children at play

calm piano and guitar music

5

a football team planning a new

play

/ “Here, the back is coming off.” calm piano and guitar music

6 close-up of a board

in the meeting situation

“Here, the end

is pinching.” /

calm piano and guitar music

7 a man with helmet

and facemask / “Play ball!”

calm piano and guitar music

8 a man sounding the

trumpet trumpet play /

calm piano and guitar music

9

close-up of the man’s mouth blowing into the

trumpet

sound of

blowing heavily /

calm piano and guitar music

10 a man blowing out

candles on a cake

sound of

blowing out /

calm piano and guitar music 11 a ventilator blowing away some papers sound of ventilator and the flying paper

/ calm piano and guitar music

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 199

12 a bank note on the

street

noises from outside

(cars)

/ calm piano and guitar music

13 trees blown by the

wind

sound of heavy

wind /

calm piano and guitar music

14 a man blowing his

nose

sound of blowing one’s

nose

/ calm piano and guitar music

15 2 men boxing

sound of a blow against the

headgear

/ calm piano and guitar music

16 a blow fish sound of

bubbling water /

calm piano and guitar music

17 a bulb with a

blowout clicking /

calm piano and guitar music

18

a woman drying her hair until the blower stops

the sound of a

hair blower /

calm piano and guitar music

19 close-up of the hair

blower clicking /

calm piano and guitar music 20 a plate falling down, breaking into pieces sound of breaking porcelain

/ calm piano and guitar music 21 a young karate destroying wooden shelves sound of breaking shelves

/ calm piano and guitar music 22 an x-ray photograph showing a broken bone in the background: shouting

/ calm piano and guitar music

23 a Lacrosse team shouting of the

team members “Go, break!”

calm piano and guitar music

24 a foot applying the

brakes

sound of squeaking

brakes

/ calm piano and guitar music

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 200 25

a pool table and a man doing the opening stroke

sound of billiard balls

clashing together

/ calm piano and guitar music

26 a man shouting into

his cellular phone /

“You’re breaking up, man, I can’t hear you!”

calm piano and guitar music

27

a man and a woman sitting on a

bed, heads down

/ / calm piano and

guitar music

28 a man hitting a TV

with a bat sound of batting /

calm piano and guitar music

29 a man choping

wood

sound of splitting the tree

trunk

/ calm piano and guitar music

30 a young girl doing

the splits

sound of sliding on the

ground

/ calm piano and guitar music

31 a banana split ice

cream on a table / /

calm piano and guitar music

32

2 men eating the ice cream with

spoons

smacking / calm piano and

guitar music

33 2 bowling pins

(split leave) / /

calm piano and guitar music

34 splitting trousers sound of

splitting /

calm piano and guitar music 35 a run in a pair of tights (shopping cart in the background) sound of shopping cart /

calm piano and guitar music

36 a man running

(close-up of legs)

steps on the

ground /

calm piano and guitar music

37 close-up of running

nose / /

calm piano and guitar music

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 201 38

a drop of paint running down the

wall

/ / calm piano and

guitar music

39 water coming out

of the water-tap

sound of

dropping water /

calm piano and guitar music

40 a car running a red

light sound of car

“I’m gonna run away!”

calm piano and guitar music

41 a boy talking, then

running away

voices / noises outside

“I’m serious, I’m gonna run

away!”

calm piano and guitar music 42 a runway (top view) cockpit sound and sound of flying airplane (some commands from the cockpit)

calm piano and guitar music

43

an airplane in the sky, later birds flying in the sky

sound of bird in

the sky /

calm piano and guitar music

44 a fly on the ground

humming and noises from

outside

/ calm piano and guitar music

45 a zip fly (close-up) laughter / calm piano and

guitar music 46 board in school class with a drawing of the middle finger, a teacher coming in

laughter “That is not good to fly!”

calm piano and guitar music

47 a piano flying

down

strange piano

sound /

calm piano and guitar music

48 a vase falling down sound of

porcelain /

calm piano and guitar music

49 a sky diver in the

sky sound of wind /

calm piano and guitar music

50 a boy diving off

high board / /

calm piano and guitar music

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 202

51 a man falling

down the stairs

sound of

thunking /

calm piano and guitar music

52

a TV in a sleeping room showing an old woman lying on the floor, two persons on a bed

/ “I’m falling and I…”

calm piano and guitar music

53 a waterfall

sound of waterfall outside

/ calm piano and guitar music

54

a girl falling asleep in the arms of a

boy

/ / calm piano and

guitar music

55 autumn coloured

leaves (top view)

sound of birds in the background

/ calm piano and guitar music

56 a falling tree sound of leaves / calm piano and

guitar music

57 a feather in the air /

“Light as a feather, come

on!”

calm piano and guitar music

58 two men at weight

lifting /

“Aaah…Light as a feather…light.”

calm piano and guitar music

59 shining sun / / calm piano and

guitar music

60 a girl playing with

a flashlight laughing /

calm piano and guitar music

61 a man lighting a

cigarette

sound of the

lighter /

calm piano and guitar music

62 a priest in church / “Let there be

light!”

calm piano and guitar music

63 a small night light

in a socket / /

calm piano and guitar music

IMAGE [&] NARRATIVE Vol. 13 No. 4 (2012) 203

64 stadium lights, later

turned off

buzzing of the

lights /

calm piano and guitar music

65 lightning

illuminating a tree

sound of

thunderbolt /

calm piano and guitar music, then the music

stops

66 stars / space, later a

falling star hollow noise / silence

67 close-up of keyboard, space bar is pressed sound of keyboard / silence

68 black screen / / silence

69 credits / / silence

Janina Wildfeuer is Lecturer for German and Interdisciplinary Linguistics at the University of Bremen, Germany, Faculty of Linguistics and Literary Science. She was a member of the doctoral group “Textuality of Film” at the University of Bremen and received her PhD in Linguistics in 2012 with a thesis on “Coherence in Film and the Construction of Logical Forms of Discourse: A Formal-Functional Perspective.” Her research interests focus on Multimodal Discourse Analysis, Semiotics, Film Analysis and Discourse Semantics.