A Business and Technology Strategy Approach for the

Building Equipment Service Industry

by

Bruce E. Hoopes

B.S., Electrical Engineering (1985) Pennsylvania State University

Submitted to the System Design and Management Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Science in Engineering and Management at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology February 2000

© 2000 Bruce E. Hoopes. All rights reserved.

MASSACHUSES INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

JAN 20 U

LIBRARIES

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part.

Signature of Author... ...

System Design and Management Program February, 2000

Certified by... . . . . . D. Eleanor Westney

Sloan Fellows Professor Of International Management

1-1 Thesis Supervisor

Acceptedby...

Thomas A. Kochan LFM/SDM Co-Director

--- orge M. Bunkerprofessor of Management

Accepted by ...

Paul 'A.* Lagace LFM/SDM Co-Director Professor of Aeronautics & Astronautics and Engineering Systems

A Business and Technology Strategy Approach for the

Building Equipment Service Industry

by

Bruce E. Hoopes

Submitted to the System Design and Management Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Science in Engineering and Management

Abstract

The building equipment service industry has traditionally been characterized by fragmentation and the lack of dominant players. For each different type of building equipment, the building owner interacts with specialist service personnel and proprietary monitoring equipment and technology. Attempts to standardize the interactions between building equipment products, and thus to build a common interface to building owners, have largely failed.

The advent of internet standards and related information technologies provides a new business opportunity in this industry. This entails the creation of a service layer between the building owner and the specialist service companies, in which a single provider monitors all building equipment and is the sole interface to the building owner. The pre-requisite for this business is the establishment of a technical architecture that interfaces with existing building equipment technologies, as well as adopting readily to new technologies. In this thesis, I develop key elements of the business and technology strategy for this building equipment service opportunity. I then analyze and propose a technical architecture that enables the strategy.

Thesis Supervisor: D. Eleanor Westney

Dedicated to my father, Walter Ronald Hoopes.

Love and many thanks to my wife, Karen, and son, Andrew, for their endless support and sacrifice.

Table of Contents

1. INTRO DU CTIO N ... 9

2. INDU STRY BA CK G RO UND ... 12

2.1. BUILDING EQUIPMENT ... 13

2.2. BUILDING AUTOMATION SYSTEMS ... 15

2.3. SERVICE M ODELS ... Is 2.4. TRENDS IN SERVICE ... 20

3. BUSIN ESS STRATEGY ... 22

3.1. OPPORTUNITY DESCRIPTION ... 22

3.2. PRODUCT OFFERING AND VALUE PROPOSITION ... 24

3.3. STRATEGIC ELEMENTS ... 26 3.4. INTERMEDIATION ... 28 3.5. SERVICE M ODELS ... 29 3,6. ENTRANT OR INCUMBENT? ... 33 4. TECH N O LO G Y STRATEG Y ... 36 4. 1. CREATING A STANDARD ... 37 4.2. CAPTURING V ALUE ... 41 4.3. ARCHITECTURAL STRATEGY ... 42 4.4. IMPLICATIONS ... 43

5. PRO DU CT ARCH ITECTURE ... 45

5.1. DEFINING ARCHITECTURE ... 46

5.2. THE ARCHITECTING PROCESS ... 48

5.3. UPSTREAM INFLUENCES ... 52 5 .4 . F U N C T IO N ... 5 2 5.5. ATTRIBUTES ... 56 5 .6 . C O N C E PT ... 5 7 5 .7 . F O R M ... 5 8 5.8. CONNECTIVITY ... 63 6. CO N CLUSIO N ... 65 BIBLIO G RAPH Y ... 68

List of Figures

Figure 1: Building Automation System Architectures ... 15

Figure 2: BACnet and LonW orks Summary ... 18

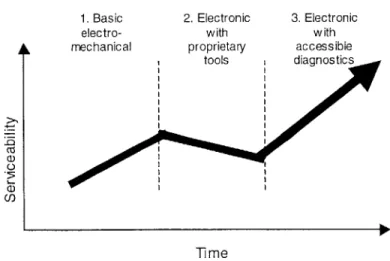

Fig ure 3: Trends in Serviceability ... 19

Figure 4: Interaction with Service Providers ... 20

Figure 5: Integrated Service Provider... 22

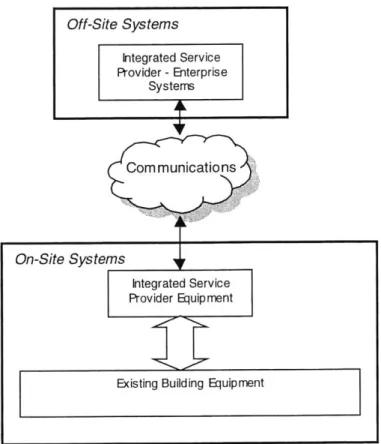

Figure 6: Sum mary of On- and Off-Site Equipment ... 25

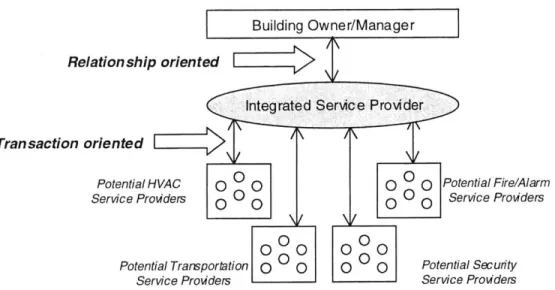

Figure 7: Transaction Oriented Service ... 31

Figure 8: Application of Agents... 32

Figure 9: Summary of Incum bent vs. Entrant... 35

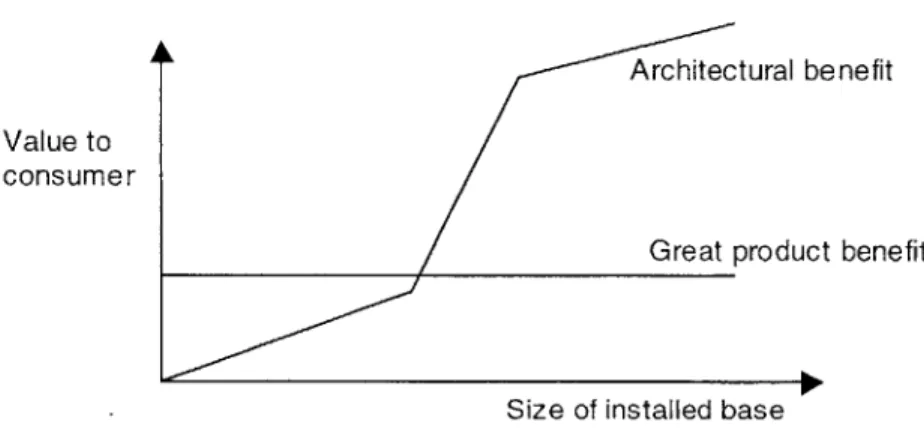

Figure 10: Consumer Benefits and Installed Base ... 38

Figure 11: Reference Architecting Process... 49

Figure 12: Logical Architecture ... 59

Figure 13: Physical Architecture -Basic Application... 61

Figure 14: Physical Architecture -Large Scale Application... 62

1.

Introduction

This thesis examines an opportunity in the building equipment service industry. Building equipment systems provide the functions necessary for the operation of modern

buildings; examples are heating, air conditioning, and alarming systems. The servicing of these systems involves monitoring, maintenance, and repair, and is typically performed under contract by firms specializing in particular equipment types. As a result of this specialization, a building owner or facility manager is forced to interact with many different service providers. The consequence is building management inefficiency, and inconsistency in process and information reporting. However, the forces of information technology, internetworking, and intelligent machinery have converged to provide a new model for building equipment service. This model involves the creation of a service layer between the consumers of building equipment service and the specialist service providers.

For the enterprising firm, this new service model represents a business opportunity. An examination of this opportunity could lead in many different directions: a market

analysis, exploring revenue potential and pricing options; a competitive analysis, examining existing firms and their capabilities; or perhaps a net present value analysis intended to quantify the opportunity's value. Although each of these are important elements in an overall approach, my intention in undertaking this thesis was not to

develop a traditional business plan. Rather, I sought to explore certain strategic elements that are key to the venture's viability, and to establish a practical foundation for a firm pursuing the building equipment service opportunity.

My approach in this regard is to apply the tools of business strategy, technology strategy, and systems architecture. The business strategy is focused on the key elements of the opportunity; namely, the proposed value to the customer, alternative models for

providing service, and an examination of the types of firms best suited to the opportunity. However, as technology is the prime enabler for the opportunity, the main thrust of the thesis is the development of the technology strategy and product architecture. The

technology strategy proposes specific actions the firm can take in order to gain advantage through technology. These actions are focused on developing the product as a standard, and on ensuring that ultimately value is captured by the firm and not by imitators. The technology strategy is subsequently used as driver for the product architecture, which is described in both logical and physical form. By developing the product architecture to this level of detail, I provide a practical foundation on which the new service venture can be based. In the end, the business strategy, technology strategy, and product architecture suggestions are meant to form a cohesive approach for a potential building equipment service provider.

After this first introductory chapter, the thesis includes four more chapters. The second chapter provides an evaluation of the current state of the building equipment service

industry. This includes an overview of building equipment types, and a description of previous attempts to network building systems together. Models for providing building

equipment service are examined, with a particular emphasis on the relationships between service providers and consumers. Enabling trends in the service industry are also

covered. Chapter Three introduces the business opportunity in detail, including an evaluation of alternative strategic approaches. The product offering is described, noting the particular benefits to the customer. As the basic proposition involves the introduction

of a new layer in the service value chain, a section is devoted to discussing the merits of brokering arrangements. Different models for providing service within the new approach

are evaluated, and finally a determination of the advantages of entering via an incumbent firm or an entrant firm are discussed.

In Chapter Four, the basis for a technology strategy is laid out. Specifically, this covers elements of standards creation, means of capturing value for the first mover, and

strategies for the product architecture. The final chapter develops the product

architecture. The architecting process is established, then each step is defined and tied back to the technology strategy. The resultant architecture is described in two forms: the logical form, and the physical form. Examples of typical applications are provided in

order to establish the architecture's scalability. The final step evaluates the connectivity of the architecture against strategic goals and upstream influences.

2.

Industry Background

The modern building requires a multitude of functions for successful operation, ranging from heating and air-conditioning to vertical transportation. The interrelated mechanical, electrical, and computer systems that provide these functions are known as building equipment systems. The specific equipment requirements of each building are unique due to varying uses, designs, materials, climates, and construction techniques. Building requirements are satisfied by custom designed building systems, even though most

components are 'off-the-shelf' -it is the combination of the components that makes each

solution unique.

This work addresses building equipment that is controlled or has the potential to be controlled by automated (electronic or computer) means, as opposed to purely mechanical systems (noting that as technology progresses more systems fall into the former rather than the latter category). These are large, complex systems, with product life-cycles that are typically measured in decades rather than years. The high purchase and installation cost of this equipment creates an incentive for the building owner to maximize the equipment lifetime. As a result, an important element of ownership is service and maintenance.

The complexity of building equipment systems means specialized skills are necessary for service and maintenance. As most building owners or facility managers lack this skill, they turn to service providers who specialize in a particular type or brand of equipment. The service provider market is split between two general types of firms. The first, the equipment manufacturers, clearly possess the equipment knowledge required to provide

the specialized service. The manufacturers are supplemented by the second type of firm

-smaller independents that have developed expertise servicing particular brands of

equipment. Although independents initially started in order to fill market voids where the manufacturers did not compete, the two often now compete side-by-side. The natural

growth inherent in the service provider market provides abundant opportunities -every

of the industry shows that service revenues approach new equipment revenues in terms of volume. For example, in the U.S. elevator industry, service sales volume is typically

80% of new equipment sales volume, with a total industry volume of $7 billion (Strakosch 1999).

2.1. Building equipment

Eyke provides the following breakdown of building equipment systems: heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, transportation systems, lighting systems, fire systems, security systems, and electrical (energy) systems (Eyke 1988). Industrial sites may require further services such as compressed air or steam. Each type of system is briefly described below.

HVAC Systems: An HVAC system provides a building with a consistent, controllable environment. Stein (1997) lists services such as heating, cooling, humidity control, air re-circulation and filtering, and exhausting odor-laden air as functions provided by HVAC systems. These systems are built from many different component types, including chillers, boilers, pumps, fans, air handlers, valves, circulators, and blowers; within a total system, components are often provided by different manufacturers. Because of the distributed nature of HVAC systems, and the requirement for consistent control, manufacturers were early adopters of embedded computer and networking technology. However, cost pressures and competitive issues resulted in the propagation of proprietary solutions. Over time, HVAC manufacturers have capitalized on

technology advances and decreasing computing costs to achieve ever greater control and monitoring capabilities.

Transportation Systems: Building transportation equipment is used to move people and goods efficiently throughout a building. Elevators and escalators provide vertical

transportation, while automated walkways provide horizontal movement. Since the early 1980's, elevator and escalator manufacturers have incorporated computing technology in their systems. Initially, microprocessors were used to replicate the relay based logic

traditionally used for system control. Over time, however, computing and software technology was employed for competitive advantage in areas such as position control, traffic optimization, and operational features. More recently, manufacturers have turned to networking and telecommunications technologies to enhance their ability to remotely

monitor systems.

Lighting Systems: These systems provide illumination using a combination of

equipment types, technology, and diffusion patterns. Typically lighting systems can be controlled via computer from central locations, and cost savings resulting from reduced energy use is a primary motivator behind control innovation. However, relatively simple control algorithms and cost considerations have precluded the necessity for advanced computing capabilities in this industry.

Fire Systems: This category of building equipment includes smoke, heat, and fire detection and alarming, extinguishing systems, and fire and smoke control systems.

These systems are governed by strict local and national regulations -in some locations

integration with other building systems is not permitted. Normally designers of these systems are cautious about using unproven new technology due to reliability concerns, but modern computing and electronics are employed, primarily for improved sensing capability and for remote communications.

Security Systems: Functions provided by security systems include intruder detection and alarming, access control, and use monitoring. Innovation in this industry is centered around detector and sensor technology, and networking capabilities. Remote

communication to central monitoring sites is also a key driver of computing technology.

Energy Systems: Although the scope of this work does not include power generating equipment, energy usage monitoring and control is an important component of modern building technology. In many cases, these controls are built directly into the energy consuming equipment, and therefore central monitoring is a reporting rather than active function.

2.2. Building Automation Systems

Each type of building equipment described above has evolved significantly over the past decades in terms of integration with electronics and computer technology. The primary motivations for this evolution were better control, higher reliability, and increased monitoring capability to detect and diagnose faults in the equipment. As micro-computers and communication capabilities propagated throughout building equipment systems, a new class of integration arose which linked the systems together. The

intention was to coordinate control between devices that had a functional relationship, for example, to optimize the HVAC systems in a building and to provide a central control capability. These integrative systems are known as building automation systems.

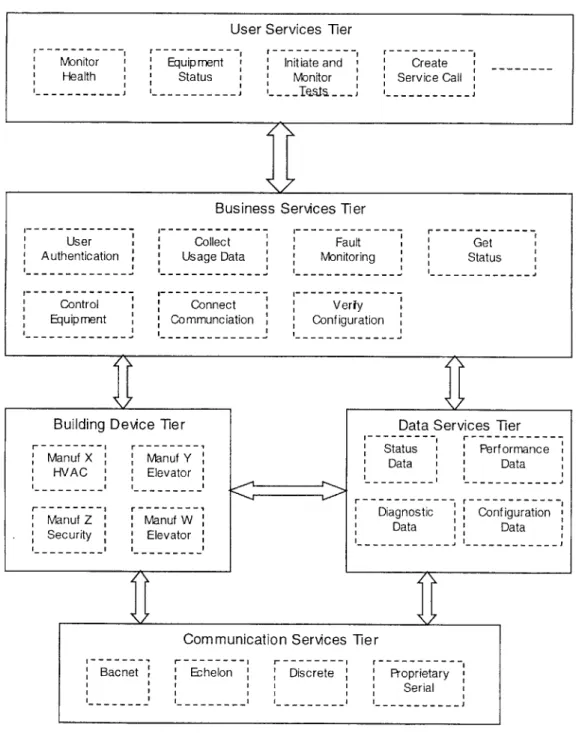

A. Centralized BAS B. Distributed BAS

CPUPC FPU - ~- ~~ F PU SC SC SC FPU ~- ~-- FP E-~ FPU FPU expansion modules

Figure 1: Building Automation System Architectures

The figure above shows two common building automation system architectures. In the centralized system, the CPU, or central processing unit, is the main controller for all building equipment devices. FPUs, or field processing units, act as the interfaces to the building equipment. In the distributed architecture, the PC only performs non-real time functions such as report generation. The control of the building equipment is contained within the standalone controllers (SC), which in turn control individual devices through expansion modules. Eyke (1988) describes the main benefits of building automation

systems as increased reliability, reduced operating costs, easier building management, and intangible benefits such as greater personnel efficiency and morale. The primary customer for these systems is the building owner or facility manager. The focus of the building automation industry has been to ease the job of the facility managers by providing inter-operation between the devices.

As Goldschmidt (1998) notes, the first generations of computerized building equipment systems relied on proprietary communication methods. That is, within a single

manufacturer's equipment offerings communication techniques were used that were not known nor readily available to outside vendors. As a result, it was difficult if not impossible to mix equipment from different vendors, and building owners became frustrated by their inability to competitively bid additions to their systems.

Manufacturers mistakenly assumed that they could achieve a form of lock-in with their proprietary systems, when in fact building owners refused to be held hostage. As Fisher (1996) asserts, the ultimate effect of this proprietary thinking was to drastically slow the diffusion of building automation systems (and the resultant benefits to building owners).

In the late 1980's two separate efforts began with the goal of developing solutions that would create a standard for integration in the building equipment and automation industry. Their main intent was to develop a communication and control standard that would allow building developers to seamlessly integrate components from different suppliers to create optimal building solutions. Both parties claimed 'interoperability' as their holy grail. Brown (1998) defines interoperability as the ability to integrate products from multiple vendors into flexible, functional systems without the need to develop custom hardware, software, or tools. Fisher offers a slightly more technical definition: two or more computer systems that share the same communications system, and ask each

other to perform various functions on a peer-to-peer basis. Clearly the adoption of such standards would be a boon to building owners and contractors. Dabholkar (1997) claims that these further benefits would be realized by the adoption of building automation

standards:

2. Standards are the key to cost savings from installation through maintenance.

3. Standards allow creativity among system specifiers and end-users.

4. Standards accelerate the evolution of technology.

The first of these standards efforts, named BACnet, was the product of the American

Society for Heating, Refrigeration, and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). As a

committee based effort requiring the input and approval from a large member body, BACnet took many years to evolve. Ultimately, in 1995, it was approved as an American

National Standard by ANSI. As such, it is the 'formal' building control standard. BACnet is essentially a paper-based standard, describing in great detail the rules used to allow building equipment inter-operability.

The competing standard, LonWorks, was developed and deployed by a single firm, the Echelon Corporation. In contrast to BACnet, LonWorks is supported by a family of products. These products contain the proprietary protocols that define LonWorks. By integrating these specialized chips into their products, manufacturers inherently meet the LonWorks standard. Echelon, of course, stands to gain as the market adopts LonWorks.

As the merits of BACnet and LonWorks are debated, however, it is clear that neither can claim victory in the standards race. Goldschmidt (1998) maintains that the building

management industry is not willing to participate in the learning curve of any new technology, and therefore any standard will take some time to penetrate. This argument

hardly seems compelling in light of rapidly diffusing standards such as TCP-IP or

Windows technology. More likely, the appearance of two competing and roughly equivalent technologies has confused the marketplace and slowed down both. Furthermore, it appears that even though a standard backbone exists for building

equipment, no 'killer application' offering the building owner great advantage has yet

been introduced. Each installation of BACnet or LonWorks does not necessarily increase the value for the next one, and therefore purchase decisions are not affected by the

BACnet LonWorks

Sponsor ASHRAE committee Echelon Corporation

Affiliated Vendors 50 published vendor id's 200 -LonMark Interoperability

(wwwBac 1999) Association (Brown 1998)

Installations 4000 sites (Newman 1997) Over 4 million devices (Frezza

1999)

Shipping Products not available Over 1500 (Tonn 1997)

Figure 2: BACnet and LonWorks Summary

2.3. Service Models

Building equipment service is typically performed under contract, and at a minimum includes equipment maintenance and repair. Specifically, most service contracts include provisions for the following items (Romano 1999):

- Scheduled Maintenance: routine, scheduled service activities intended to prevent breakdown of the equipment. The schedule interval is based on elapsed time or on

usage -for example, the number of runs an elevator makes. In some cases these

activities are required by local regulation.

- Diagnosis and Repair: determination of the cause of a malfunction, and replacement or adjustment of faulty parts. This is also known as unscheduled maintenance. - Safety Test or Audit: verification that the equipment is performing to code, as

required by regulation or contract.

As most building equipment systems are essential to the use of the facility, owners are advised to be judicious in their selection of service providers. Corcoran (1999) suggests that an effective service program has to provide the following basic benefits: it must be proactive, responsive, capable, and in touch. In practice, the primary factors upon which service providers are judged are cost and equipment availability (which measures

Originally, building equipment service was provided exclusively by equipment

manufacturers. As the new equipment industry grew, however, an opportunity came into existence for third-party providers of equipment service. Although they had an inherent disadvantage relative to the original equipment manufacturers, the basic

electro-mechanical nature of the equipment enabled anyone with initiative and a basic technical ability to take part in the service business. The advent of advanced electronics and miniaturization changed the service business for a period. Similar to the automobile industry, it became difficult for the average mechanic who did not have access to design secrets to maintain complex building equipment. Too many of the critical product elements were not visible, and therefore were only diagnosable with specialized

equipment. As building owners were confronted with the prospect of single sources for service contracts, however, they demanded that proprietary diagnostic information be made available regardless of the service provider. Manufacturers complied, providing basic diagnostic information but reserving advanced capabilities for their own service personnel. These three phases of the building equipment service industry are

summarized in the chart below.

1. Basic 2. Electronic 3. Electronic

electro- w ith w ith

mechanical proprietary accessible tools diagnostics

CZ

C')

Time

Figure 3: Trends in Serviceability

The capability to service building equipment is not necessarily transferable between different types of equipment, though. In other words, service companies may be able to

tend to equipment of one type from many different manufacturers, but rarely to different types of equipment. Largely this is due to the complexity of the equipment as well as to the homogeneity of basic design within one type. This has led to an industry structure that is vertically aligned along equipment types. The effect on the building owner or facility manager is that they have to interact with service providers for each type of equipment. There is, as a result, an abundance of providers, terminology, tools, and technology that the facility manger must be aware of. This interaction is simplified in the diagram below. Building Owner/Manager HVAC Fire/Alarm Service Service Transportation Security Service Service

Figure 4: Interaction with Service Providers

2.4. Trends in Service

Although the nature of these interactions with service providers has remained steady, several other trends in the building equipment service industry are worth noting. These trends provide the underpinning for the emerging opportunity described in this thesis. As with most other industries, the building equipment service industry has been greatly affected by the integration of computers and communication technology. Clearly there has been an impact on the equipment itself, especially in terms of customization of controls and in advanced diagnostic capabilities. However, computing technology has also enhanced the ability of service providers to understand how equipment is being used in a particular customer's environment. Furthermore, the ability to collect and

The first important trend is that the focus of building equipment service is changing from 'nuts and bolts' to information. Obviously, the proper functioning of the equipment is still the main priority, but increasingly customers are distinguishing service providers by the amount and quality of information they provide. In a discussion of service

productivity, van Biema (1997) argues that service activities are not transportable, that competition is predominantly local. For the 'wrench turning' aspect of building equipment service, this is true, but the focus on information technology and data is transforming the industry into a 'virtual' one, where value added becomes a function of best ideas and processing power.

The second trend impacting the service business is the increasing reliability of building equipment systems. Manufacturers compete for new equipment sales on many different virtues, one being equipment reliability. As the equipment becomes more reliable, and maintenance intervals are decreased, the value of service goes down. The service

contract is no longer a given -at the extreme, a customer purchasing maintenance-free

equipment questions the value of service at all. Therefore, in order to maintain the revenues associated with service, providers must shift the focus from the physical equipment to complementary services associated with that equipment. Instead of maintaining the machines, providers need to service the customers.

The third trend, at this point more a potential than a reality, is a consequence of the first

two -that maintenance and repair are becoming commodities. Information about

machines, their operation, diagnosis, and repair, is captured in databases and expert systems instead of in employee's heads. Often this information is embedded in the device itself (automobiles, for example, capture diagnostic codes which are readily

available via inexpensive software packages). As this knowledge is made available (through the demands of customers), diagnosis becomes less of a concern and repairs become part-swapping activities led by a computer. The act of repairing the equipment

3.

Business Strategy

3.1. Opportunity Description

The previous chapter described several emerging trends in the building equipment service

industry. One aspect of the industry, however, has remained static -building owners and

facility managers maintain service relationships with many different kinds of equipment specialists. Advances in information technology, and a general acceptance of

information-based services, provide an opportunity to create a new kind of layer between the building owners and the specialist service companies. This concept is represented in the diagram below:

Building Owner/Manager

Integrated Service Provider

HVAC Fire/Alarm

Service Service

Transportation Security Service Service

Figure 5: Integrated Service Provider

Instead of interacting with many different service providers, the building owner or

facility manager interacts with a single provider -the integrated service provider. The

integrated service provider concept could be based on three different overall strategies:

1. Provide the equipment: This strategy involves supplying and installing the information technology equipment that integrates information from the existing building equipment. This equipment is akin to a building automation system, with a focus on monitoring and data collection instead of control. The building owners or

equipment provides, for example by developing (or contracting for) custom information services or reports.

2. Provide the equipment and information: This option adds the creation and delivery of information services to the installation of the integrated monitoring equipment.

Service of the building equipment would not be provided in this case -only the

information to enable the service.

3. Provide the equipment, information, and service: This option represents the entire integrated building equipment service package. In addition to providing the

equipment and information services, the business would act as the sole service provider across the range of building equipment. It would provide a single interface to the building owner, ranging from 24 hour monitoring to contractual issues to emergency repair of the building equipment.

When establishing what the basic offering of a business will be, one must consider a wide range of inputs, including market, competition, regulation, capabilities of the firm, and many others. Fundamentally, however, there must be a customer with a compelling need for the product or service. When considering the three options listed above for the building equipment service industry, one can draw an analogy with the building

construction industry. The prospective owners of a building use the services of a general contractor to manage the various trades involved with the actual construction. Although

it may be cheaper to manage those interactions themselves, it takes an enormous amount of skill and effort to do so. Similarly, in the service industry, an offering that provides a single service interface to the building owners for all the installed equipment creates customer value (provided, of course, that the cost of doing so is commensurate with the recognized benefits).

Furthermore, one must consider the potential for the good or service to be adopted by the marketplace. In option one above, the result is that the purchaser has to do more work

equipment -while still managing the interfaces to the service providers. In option two,

multiple service interfaces still exist. Option three provides an integrated service to the customer, with a focus on delivering value and making the facility manager's job easier. For these reasons I propose that the offering consists mainly of information delivery and an integrated service interface, and therefore the equipment becomes an enabler for the product.

3.2. Product Offering and Value Proposition

Xerox identifies potential market opportunities in part by describing them in terms of a

product offering and a value proposition (Gabel 1998). The product offering includes the

product (hardware, software, systems) and the other supporting value chain capabilities associated with that product, such as support and customer service. Davis and Meyer (1998) add the notion that products and services are no longer distinguished, that firms must learn instead to think in terms of offers that combine the two. The value

proposition is a brief statement of the customer benefits delivered by the product offering

to its target market segments. Through these two definitions we can establish the foundation of the venture.

The product offering consists of physical equipment and services. Specifically, the

offering includes:

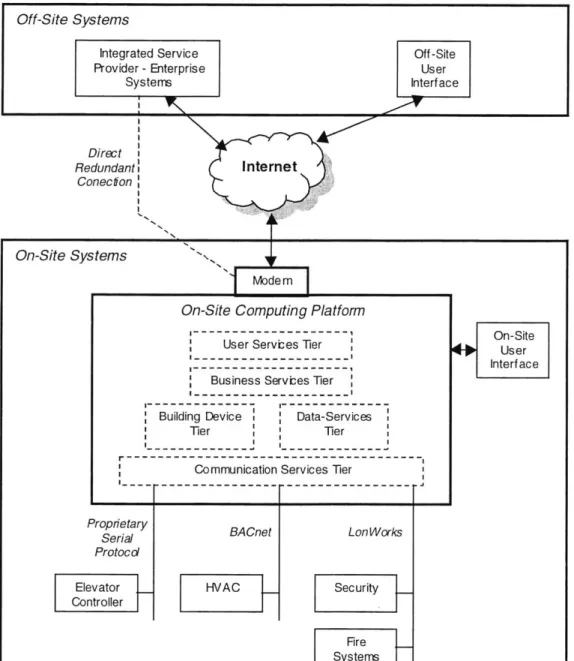

1. On-site systems that connect to and collect information from the relevant building equipment. The range of building equipment depends on the particular contract, but ideally includes any equipment that has the capacity to communicate electronically and the capability to provide information about its status and operational condition. The on-site systems will consist of computers, other electronic devices, software, and associated wiring. The on-site systems connect to off-site systems that constitute the enterprise systems of the integrated service provider. A summary picture of the total system is given in the picture below.

Off-Site Systems Integrated Service Provider - Enterprise Systems Communications On-Site Systems Integrated Service Provider Equipment

Existing Building Equipment

Figure 6: Summary of On- and Off-Site Equipment

2. The delivery of building equipment service activities such as monitoring, periodic maintenance, repair, applicable safety audits, and inspection of the relevant

equipment. Again, the range of equipment and specific activities covered under the contract depend on the installation.

3. The delivery of information services related to the building equipment. This

information would be provided in an integrated, consistent format, regardless of the type or manufacturer of the equipment. Specific items include:

- Reports on equipment usage, for example the number of operations of elevators or

escalators, or the hours of operation for HVAC equipment.

- Reports on levels of service provided by the equipment -examples are energy efficiency, or waiting times for elevators. This is useful for building owners

attempting to attract new tenants.

- Reports on equipment reliability and downtime.

- Historical patterns for the equipment.

- Comparisons of equipment to industry standards or other manufacturers. This

information is useful when planning upgrades or replacements.

- The ability to view equipment status, performance, and operating condition in

real-time via existing building network equipment and computers.

- Custom reports as requested by the building owner or facility manager.

The integrated service provider value proposition follows from the product offering, and includes the following benefits for the customer:

1. A consistent, single interface to all building equipment service issues. When reporting problems, tracking service activities, billing, scheduling maintenance, or requesting information, there is only one point of contact. This saves time, personnel, and eases the facility manager's job.

2. Injormation about building equipment presented in a consistent, integrated format. 3. Faster response from the service provider owing to the use of electronic data and

communication systems.

4. A cross-functional view of all building equipment information.

5. Scheduling for periodic maintenance and inspections coordinated between all building equipment types, resulting in less disruption to building activities.

6. Faster information access due to the use of standard information technologies such as the internet.

3.3. Strategic Elements

In summary, the business proposal involves the integration of information technology and building equipment, with the goal of buffering building owners and managers from the multitude of different types of building equipment and service providers they typically

deal with. Successfully creating such a venture demands that a number of strategic elements need to be developed. These fall into two main thrusts: business strategy and technology strategy. Business strategy covers elements such as organization, marketing, and sales (some elements of the business strategy have already been covered, including the basic offering and value proposition). Technology strategy considers how to create advantage through the use of technology and product architecture. Although both these categories contain numerous elements, in the remainder of the thesis I concentrate on those that I believe to be the critical keys to success. These key strategic elements are:

- Value of intermediation: how does the addition of a layer between building owners and service providers add value for the customer?

- Service delivery model: how will the firm provide on-site equipment maintenance and repair given the potentially enormous installed base and geographic area?

- Incumbent or entrant firm: what type of organization is best-suited to establish the integrated service provider venture, an incumbent building equipment service firm, or a new entrant?

- Creating a standard: what strategies can be developed to drive diffusion of the product and to promote it as a standard?

- Capturing value: how can the integrated service provider ensure that competitors can not extract value from the on-site equipment? What strategies will ensure the firm's exclusive retention of this value?

- Product architecture: what on-site product architecture best embodies the integrated service provider goals? What are the key characteristics of this architecture?

In addition to these key strategic elements, there are certain assumptions that I make that are key to the viability of the proposal. Although the risk associated with any of these assumptions is low (I believe the approach is straightforward), they are listed here

explicitly for completeness.

- Qfftsite IT infrastructure: clearly there is a large IT development associated with the integrated service provider approach. This part of the architecture is not covered here

due to the ubiquity of the necessary architectures and technologies (for example, database and web architecture and development).

- Local staff: the firm would require local staff to perform sales, marketing, and

technical activities, primarily to establish and maintain relationships with the building owners and managers.

- Pricing and cost models: A key assumption is that the service could be provided at a rate competitive with current building equipment service providers. Although a detailed analysis is beyond the scope of this thesis, the use of information technology as a backbone is a key enabler to this assumption.

- Building equipment capabilities: As discussed previously, the trend in building equipment is towards better diagnostics and more built-in capabilities. In some ways,

the integrated service provider venture is predicated on this assumption -that building

equipment will provide accurate and reliable information relating to malfunctions and degraded performance.

3.4. Intermediation

The first key strategic issue addresses the idea of creating a layer between the producers of a service and the consumers of a service. Fundamentally, this appears to be at odds with current business strategy, and therefore is important to address. Tapscott (1996) argues that the digital economy is eliminating the middle-men between producers and

consumers -a process he calls disintermediation. This effect is due to the direct linkage

enabled by information systems and the internet in particular. Examples he cites include the elimination of recording companies and retail outlets in the music distribution value chain, and the elimination of travel agents as brokers. He further suggests that those currently in this role need to move up the 'food chain' to create new value and to provide

new types of services.

Although this dynamic is certainly true, one must draw a distinction between intermediate functions that rely on 'humans-in-the-loop' to achieve communication efficiency, and those that rely on information technology to optimize the pairing of consumers and producers. For example, internet companies like E-bay integrate and

intermediate. That is, they provide a more efficient means of linking producers with consumers, effectively automating the broker function (in fact, Tapscott lists integration as another theme of the digital economy). The end result is that consumers have the ability to find producers that otherwise would be unavailable to them. If there is a benefit for the customer, than an intermediary is both necessary and beneficial, provided neither producer nor consumer can provide the function. The integrated service provider actually provides two intermediary functions: one between the building equipment and the

building manager (provided mainly by information technology), and one between the building manager and service provider (options for this function are provided in the next section). In any case, the integrated service provider relies on instant access to extensive information, an attribute Tapscott deems critical for a broker to possess.

3.5. Service Models

The next key strategic issue for the integrated service provider is how to deliver the actual repair and maintenance of building equipment. Customers in this market demand quick response time and rapid resolution of issues. Equipment down-time is a key metric used to assess the quality of service providers. For the integrated service provider, there are three potential strategies: provide the service directly, sub-contract the service on contract basis, or sub-contract the service on a transaction basis.

1. Direct Service: This model of providing service represents the 'traditional' approach. It involves building a service infrastructure within the firm, consisting of offices, personnel, equipment, and material in all venues where the firm does business. Clearly this would be a significant undertaking requiring substantial investments in time and money. Of course, one approach to building this infrastructure is

acquisition. However, there is not a clear target for such an acquisition, that is, one firm that can provide the service capability across a broad range of building

equipment types. As building equipment service firms are typically specialized, an acquisition strategy would involve the merging of a number of different companies. The advantages to the direct service approach include clear control over the service

resources, and the ability to develop lasting relationships with customers due to the consistency of contacts.

2. Contract with Service Providers: This option involves developing contracts with existing providers of building equipment service. These contracts would be analogous with those that already exist between building owners and service

providers, with the exception that all customer interaction would be via the integrated service provider. One potential problem with this arrangement would be an inherent conflict by the contracted firms doing the actual service. Because they would compete directly for the same service contracts, their incentives may not be aligned with an integrated service provider sub-contract arrangement. Provisions would have to be built into the contract to provide these incentives; clearly a successful integrated service provider venture would give the motivation as it may provide the only vehicle for service business. A primary advantage of this option is the availability of

specialist service providers in most every location. Of course, the integrated provider would still need local presence to initiate, negotiate, and maintain relationships with the specialist providers (as well as the customers).

3. Transaction: The third, and most intriguing, option for providing service is to do so by contracting on a per transaction basis. Each building equipment service need, scheduled or unscheduled, could be viewed as an individual transaction that the integrated service provider would put out for bid to the general service community. In this scenario, the integrated provider would have longer term contracts with building managers, leading to a relationship oriented strategy. But there would be no

contracts with the firms providing the actual service -that relationship would be

Building Owner/Manager

Relationship oriented

Transaction oriented |ZZc>

Potential HVAC 0 0j 0 Potential Fire/Alarm

0000 0

Service Pro idders

o0

oService

ProwdersSO 0

Potential Transportation 0 0 0 0 Potential Security

Service Proiders Service Provders

Figure 7: Transaction Oriented Service

The figure above identifies the relationships in this scheme. Clearly the burden

associated with this proposal is to manage each of the transactions in real-time. As every service need is identified, a provider would have to be found and negotiated with. Some

building service needs are emergency conditions -for example, a passenger is trapped in

an elevator. The brokering scheme, therefore, would have to have to be fast and accurate. A bank of service operators, contacting potential service providers on each occasion, would not be sufficient to meet the real-time requirements. Any system with a human-in-the-loop may in fact make this approach untenable because of the large overhead and time consuming nature of give-and-take in the negotiation. Given that the heart of the

integrated service provider is an information system, an alternative approach would be to conduct these transaction negotiations on-line. A service need would be posted

electronically, and capable service providers would bid on providing that service. The entire transaction would be conducted on-line, except of course for the actual servicing of the equipment (although this type of repair is becoming feasible, it is not the focus of this thesis).

This type of electronic transaction is becoming commonplace on the internet, both within consumer-to-business and business-to-business relationships. Brokering transactions for

service would be an ideal application of electronic agent technology. Agents are software applications that perform as mediators in electronic commerce transactions. They are different from traditional applications in that they are "personalized, autonomous, proactive, and adaptive" (Moukas 1998). As such, they can be 'tuned' to particular user preferences or situations. Maes (1998) describes the six fundamental stages of a buying process, and goes on to suggest where agents are most likely to be used for automation. The applicability of agents to the integrated service provider business application is outlined in the table below.

Buying Stage Applicability of Agents

1. Need Identification Low -the need is dictated by equipment condition or

periodic requirements

2. Product Brokering Medium -retrieval of information to determine the

specific service to buy from provider

3. Merchant Brokering High -this stage involves the evaluation of potential

service providers based on availability, location, expertise, price, reputation, and previous experience

4. Negotiation Medium -most elements of the transaction would be

fixed, although some, such as price, could be

negotiated by agents

5. Purchase/Delivery Low -purchase could be conducted through agents,

but delivery of service in most cases requires the physical presence of service providers

6. Product Service and Medium -post-service evaluation could be

Evaluation conducted electronically through agents, and could

feed consideration set for future transactions Figure 8: Application of Agents

Proposed Service Model: Of the three potential service approaches, the transaction oriented approach is the most compelling for its ability to eliminate time-consuming manual search and negotiation. However, it also presumes that all potential players in the transaction would have the technical capability (and desire) to conduct business in this manner. It is likely that this will not be the case for some time, and therefore a fall-back option needs to be considered. The first option, developing an in-house service

capability, is the least desirable because it involves the creation of a massive and widely distributed organization. The purpose of the integrated service provider approach is to

leverage technology to reduce the manual overhead, not to increase or replicate it. Therefore the most likely way to achieve the building equipment service component is to

develop longer-term contracts with local service providers, and to gradually phase in an agent-based transaction approach as the technology becomes more widely accepted.

3.6. Entrant or Incumbent?

The third major strategic issue considers the type of firm that is best suited to enter the

integrated service provider business -an incumbent specialist service firm, or an entrant

into the industry. An incumbent firm, for example Carrier Corp. in HVAC equipment, or Simplex in alarm systems, has an established base of knowledge and customer

relationships upon which to draw if attempting to become an integrated service provider. An entrant firm, however, has advantages in terms of their ability to adopt a new business model, as this opportunity requires. The following discussion examines the key points regarding incumbents and entrants.

The ability of an incumbent service firm to successfully become an integrated service provider would depend on many things. The first would be their ability to recognize the potential of the opportunity, and to divert resources from their core business in order to

pursue it. Christenson (1997) discusses the theory of resource dependence, which states that it is not managers who determine the flow of resources within a company, but rather it is customers and investors. For innovations that do not have an immediately positive impact on a firm's major customers, it will be difficult for that firm to reallocate

resources to develop the innovation. Instead the firm will concentrate on satisfying their customers. In the building equipment service industry, an incumbent firm is typically associated with a single type of building equipment. For example, Otis Elevator provides service for elevators and escalators but not for other building equipment. Therefore, the customers of Otis will push for innovations that improve Otis' capability to quickly and effectively service elevators. Allocating resources to develop products that allow Otis to

would not help Otis' short-term objectives (i.e. current service-contract customers). Thus it would be met with resistance by those internal forces tuned to satisfying customers.

Notwithstanding the desire to allocate resources to the integrated service provider idea, one must consider the ability of an incumbent firm to develop this idea even if they chose to. Prahalad and Hamel (1990) describe the core competency of the organization as the collective learning, the glue that binds the organization together. The core competencies of an incumbent service organization revolve around knowledge related to a particular type of equipment. Carrier's service division, for example, has a clear competency in the technology associated with HVAC equipment. It has also developed competencies in other aspects of the service business, such as route scheduling and dispatch optimization. In the end, however, it is an organization tuned to the problem of delivering service to HVAC equipment.

The competencies required for the integrated service provider are substantially different. Because it is an opportunity based on information, and not on physical service and repair, the successful firm will need to develop competencies in software technology,

networking and databases. Although specialist service providers are integrating

information technology into their products and processes, inherently they have a different focus and thus a different set of core competencies than an integrated service provider would. The notion that one firm could do all these things is debated in Feeny (1998); the

authors note that successful businesses focus on creating advantage through a limited set of competencies, while outsourcing other activities to complementary providers. As discussed in an earlier section, the actual service and repair would be realized as an outsourced activity.

Additionally, the biases of an incumbent firm may be a liability in the pursuit of the integrated service provider business. I have already mentioned the competency bias towards a particular type of equipment; for example, security systems versus HVAC or lighting. Within one type of equipment, there are also biases to specific manufacturers or technologies. An example is support for the building automation standards BACnet and

LonWorks. Certain manufacturers (and providers) have pledged support for, and

developed expertise in, one of these standards. To develop expertise in the other standard

may be difficult due to the established cultural bias -frequently personnel of such firms

are on standard setting bodies associated with one of the technologies, and therefore have developed a personal stake in it.

The preceding discussion clearly leads to the conclusion that an incumbent is at a disadvantage relative to an entrant in the integrated service industry (the table below summarizes the entrant vs. incumbent issue). An incumbent faces hurdles related to resource allocation, core competencies, and biases. An entrant, on the other hand, needs to address start-up issues such as funding, resourcing, and customer development. An entrant would also need to establish the relationships on the supply-side necessary to provide service and repair (as discussed in a previous section). Perhaps the best option for a first-mover as an integrated service provider would be for an incumbent firm to set up an autonomous organization. As Christenson (1997) suggests, such an organization would be free to develop those customers and relationships that positively affect the development of the firm's technology and processes. Issues associated with funding would be at least partially alleviated, and access to the incumbent firm's customers could be provided. Ideally, an incumbent firm could provide the best of its resources to an

autonomous organization focused on the integrated service provider business.

Entrant Incumbent

Advantages - focus on critical core - funding

competencies - established customers -clean slate - tangible assets (offices,

-no bias equipment)

Disadvantages -have to raise capital - inability to allocate resources

-no tangible assets away from customer concerns

-no customer base - established biases

- mismatched competencies Figure 9: Summary of Incumbent vs. Entrant

4.

Technology Strategy

The business strategies outlined in the previous section are critical parts of the integrated

service provider concept. Each is a pillar of the overall strategy -if one is weak, the

venture on the whole will be weakened, but will remain viable. Perhaps the most important determinant of the success of the venture, however, will be the strategic

application of technology. What exactly is technology strategy? Wheelwright and Clark (1992) offer that "the objective of technology strategy is to guide the firm in acquiring, developing, and applying technology for competitive advantage". A broader definition asks the following three questions as a way to define technology strategy (Stern 1999a):

1. What technologies can affect overall customer value? 2. Can the value be captured in the face of competition?

3. Does the firm have the organizational capabilities to deliver the value?

Both definitions agree that technology is a key determinant in the value proposition, and that competitive advantage can be an outcome of a properly planned and executed technology strategy. The integrated service provider concept described in this thesis is

fundamentally enabled by technology -to connect the various types of building

equipment together, to notify remote sites when building equipment has a problem, and to give customers electronic access to both the equipment and information about the equipment. As described earlier, the offering consists of both a product and a service. The technology strategy, therefore, must consider both: the equipment that is installed at the customer site, and the information and activities that are enabled by the product.

The remainder of the thesis explores elements of the technology strategy for the

integrated service provider concept. This chapter lays out the strategy; that is, what are the guidelines the firm should adopt when making the detailed technology decisions. Determining this decision making framework early will provide a context for the

technology decisions. Without it, the decisions made each day by developers and base technology staff will result in an emergent strategy, one which may not be in the best

interest of the firm. The strategy therefore must answer a number of questions concerning the firm's technical direction: what are the actions that will increase the adoption rate of the offering? How can the technology decisions promote the development of a product (and service) standard? What can be done to prevent easy imitation by competitors?

Once the strategic technology direction is set, the technology framework can be laid out. Primarily, this consists of the product architecture, and the specific technology choices to populate the architecture. Again, some basic questions must be considered: How does the strategy drive the architectural choices? What architectural decomposition will

ensure that the product will be adaptable to the widest range of uses and customers? How do existing technologies drive the architecture choices? The integrated service provider architecture is covered in the next chapter; the remainder of this chapter is dedicated to the general technology strategy.

4.1. Creating a Standard

Although the business proposition described in this thesis is essentially a service, it relies on an underlying technology (product) backbone. The product consists of the equipment installed at the customer site that ties together the various types of building equipment, and as such represents the 'integrated' in the integrated service provider concept. The success of the business on the whole depends in large part on the success of creating a technical architecture that has the ability to satisfy a wide range of customers.

Furthermore, this success will depend on the diffusion of the product into the marketplace, and ultimately its acceptance as a standard.

From a technology strategy perspective, the notion of creating a standard architecture versus creating a great product has important implications for the integrated service provider. The distinction between the two strategies is rooted in the customer's buying decision: if the decision is based solely on the intrinsic value of the product to the customer, then developing a 'great' product is sufficient (Stern 1999b). If the buying decision depends on the extent to which others have purchased the product, then creating

a great product may not be enough -an architecture to sustain that product must be established. Specifically, the technology strategy must be focused on establishing the product as a standard, as opposed to focusing solely on attributes like performance, features, and price (although obviously these cannot be discounted). The rapid pace of technology forces many great products into early obsolescence, while architectures can transcend technological changes. As Morris and Ferguson (1993) describe it:

While any single product is apt to become quickly outdated, a well-designed and open-ended architecture can evolve along with critical technologies, providing a fixed point of stability for customers and serving as the platform for a radiating and long-lived product family.

Architectural benefit Value to

consumer

Great product benefit

Size of installed base

Figure 10: Consumer Benefits and Installed Base

The chart above demonstrates how consumer benefits increase with the size of the installed base. This effect has many drivers. Economy of scale is perhaps the best known: as the volume of the product increases, the marginal cost decreases, and these savings are passed on to the consumer. The concept of network externalities refers to the

increase in value as the total number of users increase. For example, the value of a telephone expands with the number of other telephone users. Product complementarities

describe the increase in value as additional products and services become available

before other parties will be interested in creating complementary effects. A modular architecture also provides benefits, as consumers can anticipate that new technologies will be easily integrated. And finally, the fears of adopting a new technology, and its accompanying learning curve and growing pains, can be forestalled by the existence of an installed base.

It is important to distinguish the development of a standard for the integrated service provider concept versus the standards battle in building automation system protocols (BACnet vs. LonWorks, as discussed earlier). As a system that integrates information from building equipment, and provides it to off-site information systems, or directly to

local systems, the integrated service provider equipment is not competing for the building automation protocol standard. In fact, the integrated service provider must be neutral between BACnet and Echelon (and proprietary protocols) in order to provide the greatest customer value. Of course, the adoption of a single protocol standard would make the technology development easier for the integrated service provider, but at the same time would open up the field to imitation.

There are a number of specific strategies that should be adopted by the integrated service provider in order to establish technology standard. These strategies, which are used later as inputs to the architecture development, are described below.

Low switching and adoption costs: As one component of the overall pricing strategy,

keeping the cost of integrated service low is an obvious strategic approach to ensuring adoption. However, specific requirements will ensure that the product is architected in a manner to facilitate low adoption (or switching) costs. As mentioned previously, the ability to integrate seamlessly with existing protocol standards is key. This allows building owners to keep all their existing building equipment, and gives them the flexibility to choose suppliers and equipment optimally for the specific situation. This also places a scalability requirement on the product. The architecture must be able to accommodate a wide range of customer situations, ranging from high-rise,