MITLIBRARIES

3

9080 01917 6624

';:a!!KIJKJtf!?i-:: 'mlmmm

:^Bi:::-:

^^^;li§lfi0l!§0§illln:::^^r-v; mjiinmimiijmDigitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

DEWEY^

Massachusetts

Institute

ot

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

CREATIVE

DESTRUCTION

AND

DEVELOPMENT:

INSTITUTIONS,

CRISES,

AND

RESTRUCTURING

Ricardo

J.Caballero,

MIT

Dept

of

Economics

Mohamad

L.

Hammour,

DELTA

and

CEPR

Working

Paper

00-1

7

August 2000

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper can be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research

Network

Paper

Collection at

http:/

/papers.

ssrn.com/paper.taf?abstract_id=XXXXXX

MASSACHUSETTSiN:^!IiuTt

OFTECHNOLOGY

2

5

2000

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

CREATIVE

DESTRUCTION

AND

DEVELOPMENT:

INSTITUTIONS,

CRISES,

AND

RESTRUCTURING

Ricardo

J.Caballero,

MIT

Dept

of

Economics

Mohamad

L.

Hammour,

DELTA

and

CEPR

Working Paper

00-1

7

August

2000

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper can

be downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research

Network

Paper

Collection

at

http:/

/papers.

ssrn.com/paper.taf?abstract_id=XXXXXX

CREATIVE

DESTRUCTION

AND

DEVELOPMENT:

INSTITUTIONS,

CRISES,

AND

RESTRUCTURING*

Ricardo

J. CaballeroMITandNBER

Mohamad

L.Hammour

DELTA^

and

CEPR

July 20,

2000

Abstract

There

is increasing empiricalevidence

that creative destruction, drivenby

experimentation

and

theadoption

of

new

products

and

processeswhen

investment

issunk, is a core

mechanism

of development.

Obstacles to thisprocess

are likely tobe

obstacles to the progress in standards

of

living. Generically,underdeveloped

and

politicized institutions are a

major

impediment

to a well-fimctioning creative destructionprocess,

and

result in sluggish creation, technological "sclerosis,"and

spuriousreallocation.

Those

ills reflect themacroeconomic

consequences of

contracting failures inthe

presence

of

sunk

investments.Recurrent

crises are anothermajor

obstacle to creative destruction.The

common

inference that increased liquidationsduring

crises result inincreasedrestructuring is

unwarranted.

Indications are, to the contrary, that crises freezethe restructuring process

and

that this is associatedwith

the tight financial-marketconditions that follow.

This

productivity costof

recessionsadds

to the traditional costsof

resource under-utilization.

Preparedfor the AnnualWorld

Bank

ConferenceonDevelopmentEconomics, Washington,D.C.,April 18-20,2000.We

thank AbhijitBanerjee forhis discussion ofourpaper and two anonymous referees fortheirsuggestions.

^

DELTA

Introduction

The

world

economy

today

isundergoing

momentous

reorganization in the faceof

thedevelopment

and

large-scaleadoption of information

technologies.Alan Greenspan

1999

describes the recent

US

experience

in thefollowing words:

'The

American

economy,

clearly

more

thanmost,

is in the gripof

what

...Joseph

Schumpeter

... called fcreativedestruction,'the

continuous process

by which emerging

technologiespush

out the old. ...The

remarkable

...coming

togetherof

thetechnologies thatmake

up what

we

labelIT

-information technologies

-

hasbegun

to alter,fundamentally,

themanner

inwhich

we

do

business

and

createeconomic

value".This

wave

of

restructuring isonly

the latestmanifestation

of

creative destruction,by which

theproduction

structureweeds

outunproductive segments;

upgrades

its technology, processes,and

outputmix;

and

adjusts totheevolving

regulatoryand

globalenvironment.

Ongoing

restructuringis as relevant forthedeveloping

world

as it is foreconomies

attheleading

edge of

technology. In this paper,we

draw on

the significantadvances over

thepast

decade

in theoreticaland

empirical researchon

creative destruction to formulate anumber

of

propositionsconcerning

the roleand workings

of

thismechanism

in thedevelopment

process.Some

of

the ideaswe

putforward

are firmlygrounded

inempiricalevidence; others are not

more

thanhypotheses

consistentwith

acombination

of

theoretical considerations

and

scattered evidence, butwhich

deserve

systematic investigationin the future.The

restof

thispaper

isorganized

into three sections. In the first section,we

review

recent international

evidence

on

grossjob

flows that supports the idea that creativedestruction is a core

mechanism

of

growth

inmarket economies.

Our

discussion revolvesaround

three basic facts. First, the large,ongoing,

and

persistent grossjob

creationand

destruction

flows

exhibitedby

allmarket

economies

studied providesevidence

of

extensive

ongoing

restructuring activity.Second,

thisreallocationprocess shiftsresourcesover

time fi-omlow

to high-productivity sites,and

isfound

toaccount

for a large shareof

productivity growth. Third, the very large majority

of

grossflows

take place withinnarrowly

defined sectorsof

theeconomy.

This

implies that traditional analysesof

restructuring that

emphasize

shifts acrossproduction

sectorsand

associated relative pricechanges only

capture a smallcomponent

of

thisphenomenon.

The

bulk

of

what

we

observe

calls for a different sortof

analysis,which

emphasizes

theoriesof

experimentation

and

technology adoption

^evinsohn

1999

and

Melitz

1999

apply

thoseideasto tradereform,

Olley

andPakes 1996

to industrial deregulation,and

Caballero

and

Hammour

1999

to the effectof

criseson

restructuringactivity). Further explorationof

therole

played

by

those silentflows

may

call for a shift in thedevelopment

paradigm from

the idea

of

a 'bigpush"

to amyriad

of

'littlenudges."

If creativedestruction is a core

mechanism

of

economic

growth,

obstacles to thisprocessare likely to

be

obstacles todevelopment.

This

isof

particular relevance tomany

developing

economies

today,which

have

opened

up

theirmarkets and

must

now

face thechallenge

of

notonly

catching up, butkeeping

up

with

world

standards.The

second

section argues that institutional

impediments

are likely to constitutemajor

obstacles to awell-functioning creative destruction process,

and

explores theirconsequences.

Any

notion

of

restructuring is builton

theassumption

thatinvestment

in capitaland

skills ispartly irreversible,

and

specific with respect totechnology

or the other factorsof

production

itcombines

with. Relationship specificity requires inter-temporal contracting, forwhich

aproper

institutionalframework

is critical. Ifwe

consider institutional failure as the root obstacle togrowth

in thedeveloping

world, it is likely to constitute amajor

impediment

tocreative destruction.We

explore theconsequences of

constrained contracting ability in the financialand

labormarkets

on

the restructuring process. Generically,such problems

result indepressed

creation; technological sclerosis, in the

form

of

inefficient survivalof

low-productivity units; a disruptionof

the strict productivityranking based

on

which

efficient entryand

exit

should

take place;and

privately inefficient separations.Such

illscan be

asmuch

aresult

of

underdeveloped

institutions asone of

politicized institutions inresponse

to the distributional effectsof

restructuring.On

the empirical front,we

explore availableevidence

on

job

flows

inLDCs

and

themany

issues that arise inbringing the data tobear

on

theabove

questions.Although

there isevidence of

significantjob flows

insome

LDCs,

thoseflows

may

reflect a highlyunproductive

restructuring process.However,

toreach

any

conclusive evidence, amuch

more

structural empiricalapproach

is requiredthan

what

hasbeen

attempted

so far.The

third sectionargues

that recurrent crises in thedeveloping

world

are likely to constitute asecond

major

obstacle to creative destruction.This

lineof

argument

contradicts the

commonly

held

view

thatobserved

sharp liquidationsduring

crises resultin increased restructuring.

However,

jobs

that are destroyed during a recessionmostly

feed into

formal

unemployment

orunder-employment

in the informal sector,and

notdirectly into

newly

created jobs.We

argue

that this issuecan

only

be

examined

d5mamically,

and depends

cruciallyon

thebehavior

of

creationand

destructionduring

theensuing

recovery.We

extrapolatefrom

empiricalwork

on

US

gross flows the proposition that,on

the contrary, crisesfreeze the restructuring processand

that thisphenomenon

isdue

tothe tight financial conditionsfollowing

a crisis,which

reduce

the ability to financethe creation

of

new

production

units.Given

thepresumption

thatdeveloping

economies

suffer

from

technological sclerosis, the result is a productivity-costof

crises thatadds

to the traditional costs associatedwith

under-utilized resources.Creative

Destruction

and

Economic

Growth

In this section,

we

review

recent empiricalevidence

that supports the notion that theprocess

of

creative destruction is amajor

phenomenon

at the coreof

economic growth

inmarket

economies -

an

idea thatgoes

back

toJoseph

Schumpeter

1942,who

considered

it "the essential fact

about

capitalism"(p. 83).Underlying any

notionof

restructuring is theassumption

that choicesof

technology,output

mix,

modes

of

organization areembodied

in capitaland

skills.This

irreversibilityinvestments

be

scrapped

and

replacedby

new

ones. If,on

the contrary, capitalwere

perfectly

malleable

and

skills fully generic,adjustment

would

be

costlessand

instantaneous.

At

aconceptual

level, it is theembodiment

of technology

combined

with

incessant opportunities to

upgrade

theproduction

structure that placeongoing

restructuring at the core

of

thegrowth

process, irrespectiveof whether

theeconomy

is atechnological leaderor laggard.

Restructuringis closelyrelated io

factor

reallocation. Ifinvestmentsneed

tobe

scrapped,it is

because

they areworking

with

factorsof production

thatmust

be

freedup

tocombine

with

new

forms

of

investment. In otherwords,

restnicturing generates a reallocationof

factors in

which

technology

isnotembodied.

This

linkhas

been

exploited empirically todevelop

measures

of

reallocation thatcan be used

asan index

of

restructuring.The

most

successfiil

measures

developed

so far arebased

on

laborreallocation,although

therehave

been

attempts to look atotherfactors (see, e.g.,Ramey

and Shapiro

1998).^The

literatureon

grossjob

flows has constructedmeasures of

aggregate grossjob

creation

and

destructionbased

on microeconomic

data at the levelof

business units-

i.e.,plants or firms (see

Davis

and

Haltiwanger 1998

foran

excellent survey).Gross job

creation

over

agiven

period isdefined

asemployment

gainssummed

over

all businessunits that

expand

or startup

during the period; gross destructioncorresponds

toemployment

lossessummed

over

all units thatcontract or shutdown. Although

job flows

constitute a useful indicator

of

restructuring, the linkbetween

thetwo

is loose. It is quitepossible that plant

equipment

and

organizationbe

entirelyupgraded

in agiven

locationwithout

achange

in thenumber

of

jobs; conversely, it is possible thatjobs

may

migrate

from

one

location to another(e.g., fortaxreasons) toperform

exactly thesame

activity.Many

studies arenow

available that constructmeasures

of job

flows for different countries.Three

featuresof

the datahave

emerged

thatallow

us to characterize the role1

.

Gross job

creationand

destructionflows

are large,ongoing,

and

persistent.2.

Most

job flows

take place within ratherthanbetween

narrowly defined

sectorsof

theeconomy.

3.

Job

reallocationfrom

less-productive tomore-productive

business units plays amajor

role in industry-levelproductivity

growth.

Starting

with

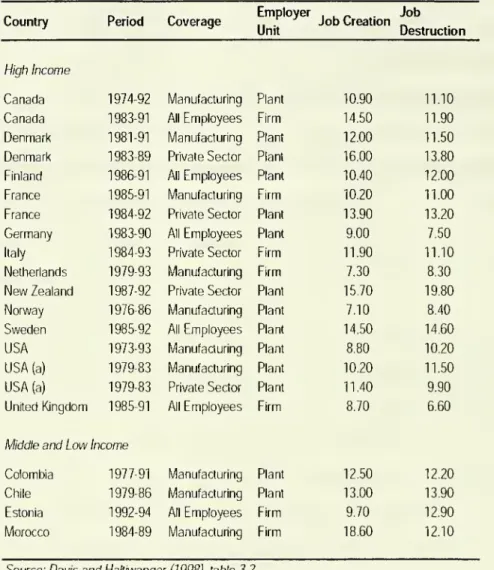

the first feature, table 1summarizes

theaverage annual job flows

measured

for different

economies. Job flows

are generally large,both

inhigh-income

countriesand

for the

few

observationswe

have of

LDCs

(Colombia,

Chileand

Morocco) and

transitioneconomies

(Estonia). It isvery

common

thatan average

of

at leastone

in tenjobs

turnsover

in a year. Creationand

destructionflows

aresimultaneous

and

ongoing.

InUS

manufacturing over

the period 1973-88, forexample,

thelowest

rateof

job

destruction inany

year

was

6.1 percent in the1973 expansion;

and

the lowest rateof

creationwas

6.2percent in the

1975

recession.Moreover,

thebulk

of

thoseflows

are not a caseof

temporary

layoffs-

which

would

notcorrespond

to true restructuring.Table 2

presents data for anumber

of

countrieson

thehigh

persistence ratesof job

creationand

destruction

over

aone-year

and

atwo-year

period (i.e., thepercentage

of

newly

createdjobs

thatremain

filledover

the period; orof

newly

destroyed jobs

thatdo

notreappear

over

the period). Overall,job flow

dataseem

to indicate extensiveongoing

restructuringactivity.

The

second

featureof

the data is that reallocation across traditionally defined sectorsaccounts

foronly

a smallcomponent

of job

flows.To

measure

theamount

of

creationand

destruction that take place

simultaneously

above

theamount

required toaccommodate

net

employment

changes,

defineexcessJob

reallocation as thesum

of job

creationand

destruction

minus

the absolute valueof

netemployment

change.Table

3 presents data forvarious

economies on

the fractionof

excess reallocationaccounted

forby employment

^

An

alternative empirical approachto creativedestruction focuses onphysical capital,andaskshow much

of output growth IS associated with capital-embodied technological progress. See Hulten 1992 and

Greenwood, Herkowitz andKrusell 1997.

shifts

between

narrowly

defined sectors.This

fractionnever exceeds

one-fifth,and

istypically well

below

this level.There

seems

tobe

two major

factorsbehind

within-sector reallocation:adjustment

and

experimentation.

Needless

to say, severaljob

characteristics that are importantdeterminants

of

employment

adjustment

are not capturedby

output-based sectoral classifications.The

job

may

be

associatedwith

capital or skillsof an

outdated vintage (see, e.g., Caballeroand

Hammour

1996b), ormay

have

suffered a highly idiosyncratic disruption. In addition, itappears

that a largecomponent of

job

flows

isdue

toexperimentation in the face

of

uncertainmarket

prospects, technologies, cost structures,or

managerial

ability (see, e.g.,Jovanovic

1982).This

idea issupported

by

evidence

from

US

manufacturing

and elsewhere

thatyounger

plants exhibit higher excess reallocationrates,

even

after controlling for a varietyof

plant characteristics (seeDavis

and

Haltiwanger

1998,p. 18and

figure 4.2).Traditional analyses

of

restructuring in the tradeand

development

literatureemphasize

one dimension of

the creative destruction process-

namely major

shiftsbetween

main

sectors

of

theeconomy.

Much

less noticed is the multitudeof

creationand

destructiondecisions driven

by

highly decentralized idiosyncratic factorsand

experimentation,whose

role ispotentially equally important.Many

conventional

questions indevelopment

may come

under

anew

lightonce

we

consider the roleplayed

by

thoseunderlying

flows.For example,

Levinsohn

1999

andMelitz

1999 argue

that a significant benefitof

tradereform

arisesthrough

thischannel

fi-om factorreallocationtoward

more

productive firms.In a similar vein,

Olley

and

Pakes

1996

find that deregulafion in the U.S.telecommunications

industry increased productivitypredominantly

through

factor reallocationtoward

more

productive plants, rather thanthrough

intra-plant productivitygains.

Our

coming

discussionof

the effectof

criseson

restructuring activityand

its costsin

terms

of

productivityconstitutes anotherexample.

The

functionof

large within-sectorjob

flowsand

their relation to productivity gainscore

mechanism

in thegrowth of

productivity. Foster,Haltiwanger

and

Krian

1998

conduct

a careful studyand

survey

of

this question.Examining

four-digitU.S.

manufacturing

industriesover

the ten years1977-1987,

theydecompose

industry-levelmultifactor productivity gains

over

the periodinto awithin-plantterm

and

a reallocationterm.

The

within-plantterm

reflects productivity gains withincontinuing

plantsweighted

by

their initial output shares; the reallocationterm

reflects productivity gains associatedwith

reallocationbetween

continuing

plants, entryand

exit.They

find that reallocationaccounts

on

average

for52

percentof

ten-year productivity gains.Entry

and

exitaccount

for half

of

this contribution: plants that exitduring

the periodhave

lower

productivity thancontinuing

plants; plants that enteronly

catchup

graduallywith continuing

plants,through

learningand

selectioneffects.Other

studiesof

US

manufacturing

based

on

somewhat

differentmethodologies

(see Baily,Hulten

and Campbell

1992;Bartelsman

and

Dhrymes

1994) concur with

theconclusion

that reallocationaccounts

for amajor

component

of

within-industryproductivity growth. It

would be

of

great interest toknow

whether

restructuring is asproductive in

LDCs

as it is in theUS,

but relevant studies arefew and

give rise tomethodological

issues.Aw,

Chen

and

Roberts

1997, focuson

Taiwar;

Liu

and

Tybout

1996

on

Colombia.

Both

define the within-plantterm

of

theirproductivitydecomposition

based

on

a plant'saverage

shareover

the period rather than its initial share.^As

discussed

by

Foster et al. 1998, this tends to under-estimate the contributionof

reallocation across continuing plants.

Moreover,

both

studiesconduct

theirdecomposition over

ahorizon

shorter than ten years: five years forTaiwan,

and

only

one

year

forColombia. This reduces

the contributionof

entry,which

takes placedynamically

through

theabove-mentioned

learningand

selection effects. It is alsomore

sensitive to the cyclicalityof

productivity,which one

expects to affect productivitygrowth

mostly

within plants.

The

resulting contributionof

reallocation toaverage

producfivity gains is34

percent forTaiwan,

and

near

zero forColombia.^

Given

themethodological

In fact

Aw, Chen

and Roberts 1997use firmratherthanplant-level data,anddefine a within-firm term.Since sectorweights arenotprovided by

Aw

et al. 1997,the calculatedaverage contribution gives equaldifferences, it is difficult to

know

whether

thisimphes

that factor reallocation in thoseLDC

countries is lessproductive

than intheUS.

The

evidence

of

extensive,ongoing job flows

that are pervasivethroughout

theeconomy

and

constitute amajor

mechanism

of

productivitygrowth

points to the centralityof

creative destruction in the

growth

process.Whether

ongoing

restructuring is, in fact, asproductive in

LDCs

as it is inan

advanced

economy

like theUS

is amajor

concern,but itdoes

notdiminish

the potentialimportance

of

this process for growth.A

corollary is thatobstacles to creative destruction are likely to

be

obstacles todevelopment,

and

should be

of

centralconcern

todevelopment

theoryand

policy.Such

potential obstacles are thefocus

of

the restof

thispaper.Institutions

and

Restructuring

We

have

seen that the notionof

restructuringpresumes

thatinvestment

is partlyirreversible.

When

two

factorsof production

enter into aproduction

relationship, theydevelop

a degreeof

specificitywith

respect toeach

otherand

to the choiceof

technology,in the sense that their

value

withinthisarrangement

is greaterthan their value outside. Inthe

presence

of

specificity, the institutionalenvironment

becomes

critical.The

reason is,very

generally, that irreversibility in the decision to enter aproduction

relationshipwith

another factor creates ex-post quasi-rents that

need

tobe

protectedthrough

ex-antecontracting (Klein,

Crawford and

Alchian

1978). Ifcontracting ability is limited, it is theinstitutional

environment

thatdetermines

the rulesby which

those quasi-rents are divided.Poor

institutions,by

definition, preventone of

the parties to a transactionfrom

getting the value

of

what

it put in.This

disrupts thebroad

range

of

financing,employment

and

output sale transactions that underlie a healthy creative destructionWe

view

institutional failure as the root obstacle toeconomic growth

in thedeveloping

world/

This

leads us to thepresumption

thatpoor

institutions are likely to constitute amajor

disruption to creative destruction.To

the extentthatinvestment

irreversibilitytakeson

an

entirelynew

dimension

in thepresence

of

contracting difficulties, itbecomes

of

crucial

import

forthe analysisof development.

In this section,

we

propose

asimple

model

of

the distortions that are likely to affect the restructuring processand

examine

related empirical evidence.Our

treatmentof

institutions is deliberately

very

generic.Our

purpose

is not tocomment

about

specificarrangements,

but to identify acommon

element

likely to affect creative destruction in asystematic fashion

and which

isshared

by

many

examples of

institutional failure-financial

markets

that lack transparencyand

investor protection, overly protective laborregulations, highlypoliticized

and

uncertaincompetitive

regulations, etc.Theoretical

Considerations

A

basic model.We

develop

a basicmodel, based

on

Caballero

and

Hammour

1998a,which

focuseson

specificity in the financingand

employment

relationshipsand

itsimplications for aggregate restructuring.

For

thispurpose

we

introduce three factorsof

production: capital, entrepreneurs,

and

labor.The

specificityof

capitalwith

respect toentrepreneurs affects financing transactions; its specificity

with

respect to labor affectsemployment

transactions. All three factors exist in infinitesimally small units.Entrepreneurs

and

laborhave

linear utility in theeconomy's

unique

consumption

good,

which

we

use asnumeraire.Contracting obstacles affect the possibility

of

economic

cooperation. In order to capturetheir implications at a general level,

we

define foreach

factortwo

possiblemodes

of

production;

Autarky

and

JointProduction

(see figure 1). In Joint Production, the threefactors

combine

in fixedproportions toform production

units.Each

such

unit ismade

up

^SeeLinandNugent 1995 for

abroadreview.

of

(i) a unitof

capital; (ii)an

entrepreneur/;and

(Hi) aworker.Each

entrepreneur / hasan

innate level

of

skill thatdetermines

theproduction

unit's productivity,measured by

theamount

7,of

theconsumption

good

the unitcan

produce.Each

entrepreneur also starts w^itha levelof

networth

a,>

thatcan

finance partof

theunit's capital requirement.The

remaining

financing requirement,6,=

1-

a, isprovided

by

external financiers.We

assume

thatworkers

startwith

zero net worth.Cooperation

in JointProduction

gives riseto

investment

specificity:once committed,

capital is fully specific to the entrepreneurand

theworker. Ithas

no

ex-postuse outside itsrelationshipwith

them.

The Autarky

mode

of production

is freefrom

investment

specificity. If theydo

notparticipate in a Joint

Production

unit, factorscan

operate inthe followingAutarky

modes:

(i) Capital

can be

invested in the international financialmarkets

at a fixedworld

interestrate

/

>

("/i" stands for Autarky), (ii) Ifan

entrepreneurdoes

not enter JointProduction,

he simply

also invests his networth

at theworld

interest rate. (Hi)Autarky

for

Labor

corresponds

toemployment

in the "informal"sector at awage

w''given

by

theinformal-sector labor

demand

function:(1)

U

= UiW^X

U'<0,

where

U

stands forinformal-sectoremployment.

In order to analyze restructuring,

we

assume

theeconomy

startswith

pre-existingproduction

units as well as asupply

of

uncommitted

factorsof

production.Events

takeplace in three consecutive phases: destruction, creation,

and

production. In the destructionphase, the factors in all pre-existing units decide

whether

to continue toproduce

jointly,or to separate

and

join theuncommitted

factors. In the creation phase,uncommitted

factors either

form

new

JointProduction

units orremain

inAurarchy.

In the final phase,production takes place

and

factorrewards

are distributedand

consumed.

Ifthe factors ina Joint

Production

unitseparate after the creationphase, theironly

option is tomove

back

toAutarky.

Introducing pre-existing units allows us to

analyze

destruction decisions.We

assume

theirproductivity distribution is

over

the interval^"e

[0,y'"'^] and, for simplicity, that ithas

negligiblemass.

The

supply of

uncommitted

factors is as follows/i^The

supply of

capital is unlimited,(ii)

The

supply

of

entrepreneurswith

any

given

productivity^6

[0,y'""''']

is also unlimited, but not all

of

them

have

positive net worth.We

assume

thatentrepreneurs

with

positive networth

are distributedaccording

to auniform

density0>

for

each

productivity level,and

thatthey

allhave

sufficientfunds

to fully finance aproduction

unit (a,>

1). (Hi)The

aggregatemass

of

labor is one, so thatemployment

in JointProduction

isgiven

by

(2)

L=\

- U(\/).Efficient equilibrium.

We

first derive theeconomy's

efficient-equilibrium conditions,which would

arise if agentshad

perfect contracting ability.We

restrict ourselves toparameter

configurations that result inan

interior equilibrium (0<L

<

1).On

thecreation side,

given

that thesupply

of

entrepreneurswith

the highestproductivity^"''" isunlimited

and

thattheAutarky

returnon

capital is/, labor'sAutarky

wage

must

satisfy(3)

v/*

=y'"'"-/

(a "*"

denotes

efficient equilibrium values).Any

wage

below

thisvalue

would

induce

infinite Joint

Production

labordemand; and

any

wage

below

would

induce

zerodemand.

The

labordemand

and

supply

system

(2)-(3)determines

the efficient equilibrium creationof

JointProduction

units, as illustrated in figure 2.Note

thatthe JointProduction

rewards

for capital

and

labor are equal to theirAutarky

rewards,and

that thereward

forentrepreneurs is zero

because

of

theirunlimited supply.On

the destruction side, scrapping the capital invested in a pre-existing unit freesup

aunit

of

labor. Efficient exit willtherefore affect allunitswith

productivitylevels(4)

/

<

v/*.Incomplete-contracts equilibrium.

Because

of investment

specificity,implementing

theefficient equilibrium requires a contract thatguarantees capital in Joint

Production

itsex-ante opportunity cost

/.

The

contractingincompleteness

we

introduce isdue

to theinalienability

of

human

capital,which

rendersunenforceable

any

contracting clause thatremoves

the rightof

the entrepreneur or theworker

towalk

away

from

the JointProduction

relationshipex

post (seeHart

and

Moore

1994).This

affectsboth

theemployment

transactionbetween

laborand

capital,and

the financing transactionbetween

the entrepreneur

and

external financiers.Starting

with

theemployment

relationship,we

assume

that theworker

dealswith

theo

entrepreneur

and

his financier as a single entity. Ifproduction

unit i has productivityyt,its associated specific quasi-rents, is the difference

between

the unit's outputand

itsfactors'ex-postopportunity costs:

(5)

St=y,-W',

consideringthatthe

worker

moves

toAutarky

ifhe

leaves theproduction

unit.Following

the

Nash

bargaining solution for sharing the unit's output,we

assume

each

party gets itsex-post opportunitycostplus a share

of

the surplussi. Ifp

e

(0,1) denoteslabor's share:(6) Wi

=

\/

+

I3siand

Ki=

{l-p)Si,where

w,and

;r,denote

therewards

of

laborand

capital, respectively.The

contractingproblem

adds

a rentcomponent

pSitowages.

Turning

to the financingrelationship, theassociated specific quasi-rentscorrespond

to thefull profit Ki

because

the ex-post outside optionsof

the entrepreneurand

externalfinanciers are worthless.

Again,

because

of

the inahenabilityof

human

capital,no

contract

can prevent

the entrepreneurfrom

threatening to leave the relationship.Any

contract

can be

renegotiatedaccording

to theNash

bargaining solution,which

gives theentrepreneur a share

ae

(0,1)of

Tttand

gives the external financier a share (1-a).The

firm's outside liability

can

thereforenever

exceed

(7)

/bt<{\-a)7ti.

This

financial constraint places alower

bound

on

the networth

a,=

1-

6, theentrepreneur

needs

to starta project,which

can

be

writtenas(8)

a,>\-{\-a)(\-p)(y,-w'y/.

based

on

(5)-(6).We

assume

a

is largeenough

that (8) requires positive networth

when

yi

-

y""^-This

implies thatonly

entrepreneurswith

positive networth can

enter JointProduction, in

which

casewe

have

assumed

that theyhave

enough

funds

to fully financea

production

unit.We

now

solve for the incomplete-contracts equilibrium conditions. Startingwith

creation,an

entrepreneurwho

is able to finance aproduction

unit will find itprofitabletodo

so if(9)

;r,>/,

which, given

(5)and

(6), is equivalentto(10)

yi>W

+ [\+fil{\-P)y\

Because

of

the rentcomponent

inwages,

capitalbehaves

as ifit faced aworld

interestrate higher than r^ .

The

JointProduction

demand

for labor isgiven

by

themass

of

entrepreneurs

whose

productivity satisfies (10)and

can

finance aproduction

unit:One

reason could bethattheentrepreneurcandisguiseproperfundsasbeing external,andviceversa.(11)

L =

(p[y'""'-W'-[\+m-l3)Vl

Together

withequation

(2) for thesupply

of

labor, thisdetermines

theincomplete-contracts equilibrium level

ofL.

As

illustrated in figure 2, labordemand

(11)under

incomplete

contracts fallsbelow

itsefficient-economy

counterpart (3).This

occursboth

because

of

labor-market rents(which

shifts thecurve

down

vertically)and

because of

the financial constraint(which

rotates thecurve

down

around

its vertical-axis intercept). Inthe incomplete-contracts equilibrium, Joint

Production

employment

and Autarky

wages

are

lower

than their efficient-equilibrium counterparts:(12)

L<L*

and

>/<>/*.

Turning

to destruction, note that aworker

who

leaves a pre-existingproduction

unit will findemployment

in JointProduction

with

probability!, inwhich

casewe

denote

hisexpected

wage

by

E[w];

and

willremain

inAutarky

with

probability (1 -L), inwhich

casehis

wage

willhew^.

The

exitcondition is therefore(13)

/<Z£[w]

+

(l-!)>/.

Characterization

of

equilibrium.We

now

characterize the general-equilibriumconsequences

of incomplete

contracting.The

imbalances

we

describe constitute a highlyinefficient

macroeconomic

solution to theunresolved

microeconomic

contractingproblems.

We

first discuss featuresof

equilibrium that are highly suggestiveof

theexperience

of developing

countries, but pertainonly

indirectly to restructuring;we

thenturn todirect implications for the restructuringprocess.

In order to avoid issues related to the possibility that the entrepreneur

may

want to restart in anew

productionunit,

we

assumeentrepreneursinpre-existingunitshavezeronetworth.1.

Reduced

cooperation.At

the purelymicroeconomic

level, it iswell

known

thatlimited contracting ability

hampers

cooperation.We

have seen

that positive-valueJoint

Production

projectsmay

notbe undertaken because

labor (eqn. 6) or theentrepreneur(eqn. 7)

can

capturerentsbeyond

theirex-ante opportunitycosts.2.

Under-employment.

As

we

have

seen

in the discussionof

equation

(12), JointProduction

is characterizedby under-employment

^

< L

),which

isan

equilibriumconsequence

of

obstacles tocooperation

in the financialand

labor markets. In partialequilibrium,rent appropriation

reduces

the JointProduction

returnon

capital. In orderto restorethisreturn to the level f^ required

by world

markets,fewer

JointProduction

units are created, informal-sector

employment

balloons,and

the opportunity-costcomponent

\/ of

wages

falls (eqn. 6). Generally, the extentof

under-employment

depends

on

thesupply

elasticityof

the factor that suffersfrom

specificity,which

we

assume

here tobe

infinite.The

counterpartof

under-employment

in JointProduction

isan

overcrowded

informalsector

{U

>

U

).The

reason

thishappens

is thatwe

have

assumed no

need

forcontracting in

Autarky.

We

view

the informal sector asone

where

transactionalproblems

are less severebecause

there is lessneed

for cooperationwith

capital(due

to

low

capital intensity or constant returns),because

employment

regulationscan

be

evaded,

etc'3.

Market

segmentation. In the incomplete-contracts equilibrium,both

the laborand

financial

markets

aresegmented.

There

areworkers

and

entrepreneurs inAutarky

who

would

strictly prefer tomove

into Joint Production, but are constrainedfrom

doing

so.Put

anotherway,

thosetwo

factors earn rents in JointProduction. It iseasy

to see that the rent

component

of

JointProduction

wages

in (6) is positive,and

setsthem

strictlyabove

the informal-sector wage.''However,

thepresence

of

rentsdoes

not entail

high

wages,

but quite the contrary.One

can

show

that JointProduction

'°Banerjee and

Newman

1998 applyasimilarinterpretation tothetraditional sector,whichthey seeas a

sectorwhere contractingiseasierbecauseinformationasymmetriesarelesssevere.

wages

arelower under incomplete

contracts than inthe efficienteconomy.

To

see thisfor

any

production

uniti,replace Ttt=

yt- w, into (9) toget(14)

Wi<y,-/<y'"'"-/

= W'\

The

rentcomponent

of

wages

arisesthrough depressed

wages

in the informal sector,not

because

of high

wages

in JointProduction. Similarly,from

(10), it is clearthanan

entrepreneur

with

intra-marginal productivity^,earns positive rents equal toyt-w

-[1

+

p/{\-

p)]r^ associatedwith

the scarcityof

internal fiinds.Those

rentswould

notarise in

an

efficient equilibrium.We

now

turn to the characteristicsof

equilibrium that pertain directly to restructuring.The

first three properties characterize theamount

of

equilibrium creationand

destructionof

JointProduction

units; thelasttwo

characterize thequalityof

restructuring,understood

asthe net gain that results

from

it.4.

Depressed

creation. Since creation in thiseconomy

is equaltoL

< L

, it follows thattheequilibrium rate

of

creation isdepressed

compared

to the efficienteconomy.

5. Sclerosis.

The

JointProduction

structure suffersfrom

sclerosis, inthe sense thatsome

production

units survive thatwould

be scrapped

inan

efficienteconomy.

To

see this,compare

the efficientand

incomplete-contracts exit conditions, (4)and

(13).Sincew

< W^

was

shown

in (12) forAutarky and

w,<

v/*

in (14) for Joint Production, it isclear that cost pressures to scrap are

lower

in the incomplete-contracts than in the efficient equilibrium. Sclerosis is thus a resultof

the under-utilizationand

low

productivity

of

labor. Sluggish creationand

sclerosiscan

impose

aheavy

drag

on

aggregate productivity.

6.

Unbalanced

restructuring. Destruction is excessivelyhigh

compared

to thedepressed

rate

of

creation.To

seethis, notethattheprivate opportunity costused

in (13) for exit'

' Simplynotethat (9) impliesTz; >0.

decisions is

higher than

the socialshadow

wage

v/ of

labor.This

isdue

to thepossibihty

of

capturing a rentcomponent

inwages,

which

distortupwards

theprivateopportunity cost

of

labor. Itmay

appear

paradoxical that theeconomy

exhibitsboth

sclerosis

and

excessive destruction. In fact, theformer

is acomparison

with

the efficient equilibriumand

the latter is acomparison

between

privateand

social valueswithin the incomplete-contracts equilibrium.

The

unbalanced

natureof

grossflows

isclosely related to the

presence

of

rentsand market

segmentation. InCaballero

and

Hammour

1996a,we

argue

that itsheds

lighton

the natureof

employment

crises indeveloping

countries.7.

Scrambling.

In the efficienteconomy,

only

themost

productive

entrepreneurswithy

=

y""^ areinvolved

in Joint Production.Had

theirnumber

been

insufficient, otherswould

have been

brought

inaccording

toa strictproductivity ranking.On

thecreation side,an

efficientprocess

should

result in the highest-productivity projectsbeing

implemented. This ranking

isscrambled

in the incomplete-contracts equilibrium, asanother characteristic

of

theentrepreneur-

networth

- comes

into play.This

tends toreduce

the qualityof

thechum,

inthe sensethatthesame volume

of scrapping

and

re-investment

will result in a smaller productivity gain.8. Privately inefficientseparations.

A

dimension

thatwe

have

actually not incorporatedin

our model,

butwhich

can

also constitutean important

consequence

of

contracting difficulties, is the possibilityoprivately

inefficientseparations.This

can

come

about

through

factors similar to those thatmake

creation privately inefficient, in the sensethat agents are constrained

from

starting positivelyvalued

projects.For example,

assume

that aproduction

unitgoes through

a periodof

temporarily negativecash flow

that

must

be

financed if the unit is toremain

in operation.Such

continuationinvestment

would

help preserve the unit's specific capital,and

is therefore itselfspecific

and

subject to a financial constraint.When

the financial constraint is binding,destruction

can

be

privately inefficientand

result in losses for theowners

of both

labor

and

capital.'^This

gives rise toanother

factor thatreduces

the qualityof

'^

See,e.g., Caballeroand

Hammour

1999fordetails.restructuring, as it generatesspurious

churn with

littlepayoff

interms

of

productivitygains.

Moreover,

once

we

admit

the possibilityof

private inefficiencyon

thedestruction

margin,

then factors other than productivitymay

affect those decisionsand

alsoscramble

theproductivityranking

in exit decisions.Political

economy.

Although

contractingincompleteness

was

founded

on

the inalienabilityof

human

capital inour model,

itcan be

due

to a varietyof

factors. In particular, the legaland

regulatoryframework

can, in itself,be

a sourceof

factor specificityand

provide

the institutionalframework

thatdetermines

the divisionof

specific rents.

Legal

restrictionson employee

dismissals, forexample,

would

effectivelymake

capital partly specific to labor in the JointProduction

relationshipanalyzed

above.Moving

beyond

an

exogenous

view

of

institutions, the final theoretical issuewe

touch

on

in this section

concerns

some

of

theunderlying

causes for the institutional obstacles toefficient restructuring.

Institutions play

two

distinct functions: efficiencyand

redistribution.On

one

hand, it isnaive

to think thatmarkets

can

generally function properly withoutan

adequate

institutional

framework.

In theirefficiency role,we

have seen

that the basic principle thatdetermines

institutions is thateach

factorought

to get outthe social valueof

what

it putin

-

i.e., absentany

externalities, its ex-anteterms

of

trade.On

the other hand, it isequally naive to thinkthat

such

institutions,being

partlydetermined

inthe political arena,will not also

be

used

asan instrument

in the politicsof

redistribution.A

poor

institutionalframework

is the resultof

acombination

of under-development

in therealm

of

contracting

and

regulationsand

of

overlypowerful

political interestgroups

who

have

tilted the institutional

balance

excessivelyin theirfavor.By

displacing technologiesand

skills, creative destruction threatens a varietyof

incumbent

interests,and

can

therefore itself give rise to political oppositionand

endogenous

institutional barriers.Mere

uncertaintyconcerning

theimpact

of

restructuring can, in fact,

prop

up

opposition(Fernandez

and

Rodrick

1991).Mokyr

1992

discusses

many

historicalexamples

of

resistance totechnology

adoption,perhaps

themost

popular

of which

is the nineteenth centuryLuddite

movement

in Britainfhomis

1972).'^

The

response

can range

from mere

neglectof

theurgency

of

institutionalreform

to active barriers affecting trade, competition, regulation, the size

of

thegovernment

sector, as well as the financial

and

labormarket dimensions

thatwe

focused

on

inour

model.

As

we

have

seen, amajor

pitfallof

such

protection, ifintended

to protect labor or otherfactors characterized

by

relatively inelastic supply, is that itcan

backfireand

result inlarge-scale

under-employment and

internalsegmentation

between

thosewho

end

up

benefiting

from

protectionand

thosewho

do

not.This

pitfall isworth

highlighting as anumber

of

LatinAmerican economies

(e.g., Chileand

Argentina)

go

through

the processof

revising theirlaborcodes

in the contextof

ever increasing globalizationand

expanding

outsideoptions for capital (see Caballero

and

Hammour

1998b).A

Look

atAvailableEvidence

Theoretically,

we

have argued

thatpoor

institutions generally result in a stagnantand

unproductive

creative destruction process. Ifone

considers institutional failure as thefiindamental illness

of

thedeveloping

world, thenone

would

presume

that sclerosisand

alow-quality

chum

are prevalentphenomena.

Although

this is consistentwith

low

productivity inLDCs,

one

would

like to findmore

direct

evidence

from

job

flowson

this issue.At

first sight, the datathatwere

presented intable 1

do

hotseem

to support the ideaof

sclerosis.Job flows

in thefew

developing

countries

we

have

dataon

areof

similar, if not larger,magnitude

as inhigh-income

" Political

economy

considerations have not failed to arise in the current debate on the impact ofthe ITrevolution: "a major consequence ofrapid economic andtechnological change ... needs to be addressed:

growing worker insecurity - the result, I suspect, offear ofpotentialjob skill obsolescence. Despite the

tightest labormarkets in a generation,more workers report in aprominent survey thatthey are fearful of

losing their jobs than similar surveys found in 1991 at the bottom of the last recession. ... Not

countries (see

Tybout

1998).However,

there are severalpowerful

reasonswhy

thisevidence cannot be taken

at face value:1

.

Measurement

issues. First, it isimportant

tokeep

inmind

the lackof uniformity

injob

flow

measures,

which

may

undermine

their comparability across countries.Table

1 highlightstwo major

differences:sample

coverage

(manufacturing, privatesector, all

employees)

and

the basicemployer

unit (the plant or the firm).Other

important differences are

more

difficult to trace,most

notably the difficulties inlinking observations longitudinally in the face

of

ownership

or other changes.For

example,

Continiand

Paceli1995

report that attempts to correct Italian data forspurious births

and

deathsreduce job flows

by

about

one-fifthl"^2. Industrialstructure

and

employer

characteristics.The

magnitude

of job flows

variessystematically

with

industrial structureand

employer

characteristics. First,Davis

and

Haltiwanger

1998

show

that the industry patternof

job

reallocation intensity is quite similar across countries.A

regressionof

reallocationon

2-digit industry fixed effects forpooled

US, Canadian

and

Dutch

data yieldsan

R-squared of

48

percent (table3.4).

Although

we

are notaware

of

a systematic investigationof

this issue,we

would

expect to find that

LDC

employment

is heavily biasedtoward

light industrieswith

relatively

low

levelsof investment

specificityand

that typicallyexperience

a fastturnover rate.

One

expects this typeof

restructuringwith

small re-investmentrequirements

to yieldcommensurately

low

productivity gains.Moreover,

rather thana sign

of

their ability to restructure, thismay

even

be

an

indication thatLDCs

avoid

industries

where

restructuring isexpensive.Second,

Davis

and

Haltiwanger

(1998, figure 4.1)summarize

internationalevidence

from

seven

countries forwhich

job

reallocation rates fall significantlywith

employer

size.

Compared

tohigh-income

countries, the bias in the size distribution indeveloping

countriestoward

small plants isdramatic

(see, e.g.,Tybout

1998, table 1).unexpectedly, greater worker insecurities are creating political pressures to reduce the fierce global competitionthathasemergedinthe

wake

ofour1990s technologyboom."(Greenspan 1999)This,

by

itself, predictsmuch

largerjob

flows.How

productive thistype

of

reallocation is requires close interpretation. Ifsmall plant size is closelyrelated to the

light-industry bias

with

little technological lock-in, the benefitsof

restructuringmay

be

small.Moreover,

if small plant size is associatedwith

greater financial fragility,some

of

theobserved turnover

may

actuallybe

privately inefficientand

unproductive.3.

Restructuring

requirements.Given

the extentof

catchingup

ahead of them,

one

would

actuallyexpect

developing

economies

tohave

significantlyhigher

investment

and

restructuring requirements. In fact, the extraordinary turnover ratesexperienced

by

Taiwanese

firmsmay

be

acase

in point. In their studyof

Taiwanese

manufacturing

industries.Aw,

Chen

and

Roberts

1997

report that firms that enteredover

the previous five yearsaccount

forbetween

one-thirdand

one-halfof

1991industry output (table 1).

They

report that the equivalent figures formanufacturing

plantsis 18 to 21 percentin

Colombia;

15 to 16 percent in Chile;and

14 to 19percentin the

US

(fh. 3, p. 7).Large

turnover rates inTaiwan

arean

indication thatdeveloping

countrieshave

the potential to attainmuch

higher restructuring ratesabsent

major

impediments.

Another

useful naturalexperiment can

be

found

in EasternEuropean

transition.Haltiwanger and

Vodopivec

1997

studied the caseof

Estonia,which

was

one of

themost

radical reformers.Estonia

implemented major

reforms

in 1992.As

reported in table 1,average annual job

creationand

destruction rates in Estoniaover

the period1992-94

were

9.7and

12.9 percent, respectively.Those

figures are within therange

observed

inOECD

economies.

What

is striking is thattheycoincidedwith

a periodof

momentous

reforms.For example,

between

1989 and

1995, the shareof

private enterprises in totalemployment

rosefrom

2 to35

percent;and

the shareof

establishments

with

more

than100

employees

fellfrom

75

to46

percent. In thiscontext,

observed job

flows

inEstonia

were

disappointingly low,which

is notsurprising

given

themajor

institutionaldeficiencies facedby

transitioneconomies.

'" SeeDavisand Haltiwanger

1998,table 3.2,fn. b.

4. Productivity.

So

far,our

discussionwas

limited to thevolume of

thechum.

Our

theoretical discussion also

pointed

to other factors-

privately inefficient separationsand

thescrambling

in the productivityranking

of

enteringand

exiting units-

thatreduce

the qualityof

those flows. In principle, sclerosis is consistentwith

largeflows

ifthe latter are relatively unproductive.

The

qualityof

thechum

can

be

measured by

an accounting

exerciseof

the type discussed in the previous section,which

accounts

for the aggregate productivity

improvements

associatedwith job

flows. Inour

discussion

of

the results forColombia

and

Taiwan,

we

pointed

out thatmethodological

issuesdo

notallow

directcomparison

with

results for theUS.

As

importantly, it

should

be

pointed out that those studiesdo

notaccount

for thescrapping

and

re-investment costsof

restructuring.When

a firm exitsand

is replacedby

a higher-productivity entrant,one

should

account

for the costof

scrappinginvestments

in theformer

and

reinvesting in the latter.This

is particularly importantin

comparisons

between

high

and

low-income

economies,

when

employment

in thelatter is biased

toward

light industriesand

othermodes

of production with

low

reinvestment

costs.It

seems

safe toconclude

that cross-countrycomparisons based

on

raw

job flow

data areunlikely to

provide

conclusiveevidence

on

the efficiencyof

restmcturing.A

more

structural empirical

approach

isneeded

that addresses the typeof

issues discussed above.From

thispointof

view, thecorresponding

empirical literature is still in its infancy.Crises,

Recovery,

and

Productivity

Recurrent

crises indeveloping

economies

have

large welfareconsequences.

Some

of

these

consequences

areimmediately

apparent,while

othersmanifest

theirdamage

over

time

and

thus are often under-appreciated.A

potentiallymajor

impact

of

the lattertype isthe

dismptive

effect that crisescan

have

on

the restructuring process. In this sectionwe

explore this cormection. After clarifying a