MIT LIBRARIES

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

DE\A/BY

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

COUNTRY

PORTFOLIOS^

Aart

Kraay,

The World

Bank

Norman

Loayza,

Banco

Central

de Chile

and

The World

Bank

Luis S

erven,

The

World

Bank

Jaume

Ventura,

MIT

Working

Paper

00-16

July

2000

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can

be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research Network

Paper

Collection

at'M^^'CHUSETTSiNSTlTUTE

OFTECHNOLOGY

OCT

2 5Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working Paper

Series

COUNTRY

PORTFOLIOS^

Aart Kraay,

The

World

Bank

Norman

Loayza,

Banco

Central

de

Chile

and

The

World Bank

Luis

Serven,

The

World

Bank

Jaume

Ventura,

MIT

Working Paper

00-16

July

2000

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can

be downloaded

without

charge from

the

Social

Science

Research Network Paper

Collection

atAbstract

How

do

countries holdtheirfinancial wealth?We

constructanew

databaseof

countries' claimson

capital locatedathome

and

abroad,and

internationalborrowingand

lending,covering 68countries

from

1966to 1997.We

find that asmallamount

ofcapital flows from richcountries topoor

countries. Countries' foreign assetpositions areremarkablypersistent, and mostlytaketheform

offoreign loansratherthan foreign equity.To

interpretthese facts,we

build asimplemodel

ofintemafional capital flo9wsthathighlights the interplaybetween

diminishingreturns, production riskand

sovereign risk.We

show

that in the presence ofreasonable diminishingreturns and productionrisk, the probabilitythatinternational crises occurtwice a centuryis

enough

to generate a setof counfryportfolios that areroughlyconsistentwiththe data.

*We

thankMark

Aguiar,Daron Acemoglu,

Giancarlo Corsetti, Raquel Fernandez, RobertE.Lucas

andMark

Wright for insightfulcomments

on

aprevious draft andGian Maria

Milesi-Ferretti for his advice inthe construction of ourdataset.

We

are also grateful toCesarCalderon,Alex

Karaivanov,George Monokroussos,

andRashmi

Shankarforexcellentresearchassistance.The

opinionsexpressedhere are the authors'anddo

not necessarilyreflectthoseoftheWorld

Bank, itsexecutive directors, or the countriestheyrepresent. Financial support

from

theRegional Studies

Program

oftheLatm

American Region

oftheWorld Bank

is gratefullyIntroduction

How

do

countries hold theirfinancial wealth?Our

objective is to provide adescription ofcountry portfolios

and

advance

a parsimonious explanation oftheirmain

features.By

country portfolio,we

refer tothefinancial wealth ofthe countryand

how

it is distributed across holdings ofdomesticcapitaland

variousforeign assets.By

the net foreign assets ofa country,

we

refer tothe country's holdings offoreign equityand

loansminus

foreigners' holdings ofdomesticequityand

loans.We

first turn tothedata

and

ask:How

large are netforeign asset positions?What

countrycharacteristicsseem

tobe

associatedwith positive netforeign asset positions?How

persistent are netforeign asset positions?What

is the relativeimportance of foreign loansand

equity?Withthe

answers

athand,we

go

to the theoryand

ask:Why?

To

determinethemain

features ofcountry portfolios,we

constructanew

databaseon

foreigners' holdings ofdomestic equityand

loans,and

domesticresidents' holdings offoreign equity

and

loans.Our sample

covers the period1966-1997 and

includes68

countriesthat accountfor over90 percent ofworld productionand

trade. Constructing thisdatabase

forces us tochoose

among

fragmentaryand

imperfect sources of information

and

thenmake

(heroic?) assumptionson

how

toreconcile

them and

fill in the gaps.^ Despitethis,we

feel confidentthe inferenceswe

draw

fromthis data are robust. In fact, there is nothing subtle aboutthe empiricalregularities

we

highlight here.The

following are all verystriking features ofthe data:1. Net foreignasset positions as a share ofwealth are small in absolute value

and

negative for

most

countries.Roughly 80

percent ofthe observations in oursample

consist ofcountries

whose

net foreign assets as ashare ofwealth are less than20

percentin absolute value.We

alsofindthat the net foreign asset position isnegative forabout

80

percent oftheobservations in our sample.^ See Sinn

[1990], Rider [1994] andLane and Milesi-Ferretti[1999] foralternativesourcesof data onforeignassetpositions.

Introduction

How

do

countries hold theirfinancial wealth?Our

objective is to provide adescription of country portfolios

and advance

aparsimonious explanation oftheirmain

features.By

countryportfolio,we

refertothefinancial wealth ofthe countryand

how

it is distributed across holdings ofdomesticcapitaland

variousforeign assets.By

the net foreign assetsofa country,

we

referto thecountry's holdings of foreign equityand

loansminus

foreigners' holdingsofdomestic equityand

loans.We

firstturn tothedata

and

ask:How

large are netforeign asset positions?What

country characteristicsseem

tobe

associated with positive netforeign asset positions?How

persistentarenetforeign asset positions?

What

is therelative importance offoreign loansand

equity?Withthe

answers

at hand,we

go

tothe theoryand

ask:Why?

To

determinethemain

featuresofcountry portfolios,we

constructanew

database on

foreigners' holdings ofdomestic equityand

loans,and

domesticresidents' holdings offoreign equity

and

loans.Our sample

covers the period1966-1997

and

includes68

countries that accountforover90

percent ofworld productionand

trade. Constructing thisdatabase

forcesus tochoose

among

fragmentaryand

imperfectsources of information

and

thenmake

(heroic?) assumptionson

how

toreconcile

them and

fill in the gaps.^ Despite this,we

feel confident the inferenceswe

draw

from this data are robust. Infact, there is nothing subtle aboutthe empiricalregularities

we

highlighthere.The

following areall verystriking features ofthe data:1. Net foreign asset positions as a shareofwealth are small in absolute value

and

negativefor

most

countries.Roughly 80

percentofthe observations in oursample

consistofcountries

whose

netforeign assets as a shareofwealth are lessthan20

percent in absolutevalue.We

alsofindthat the net foreign asset position isnegative for about

80

percentofthe observations in our sample.^

See

Sinn[1990], Rider [1994] and Lane and Milesi-Ferretti [1999] foralternative sources of data onforeign assetpositions.

2.

There

is a strong positive relationshipbetween

financial wealthand

the net foreign asset position in a cross-section ofcountries. In particular,we

find thatwhen

financial wealth doubles, the share of netforeign assets in wealth increasesbythree to six percentage points. Cross-country variation in financial wealth

seems

to explain (in a statistical sense)most

ofthevariation in net foreign assetpositions,

even

after controlling for aset ofvariablesthat aredesigned to capturecross-country differences in aggregate production functions.

3.

The

share ofnetforeign assets in wealth is very persistent overtime.A

simpleregression ofthis share

on

its lagged value delivers a slope coefficient of0.98and

a R^ of93 percent. Since

we

find thatbetween

40

percentand 70

percentofthevariation in

changes

in netforeign assets canbe

attributed tochanges

in relativewealth, it

seems

reasonable to conclude that persistence in relative wealth isan

importantsource ofpersistence in foreign assets.

4.

Gross

foreign asset positions are smalland

consist mostly offoreign loans ratherthan foreign equity. In developing countries, foreign equity assets

and

liabilitiesare roughly 0.3

and

2.8 percent ofwealth, while foreign loan assetsand

liabilitiesaccountfor4.5 percent

and

8.8 percent ofwealth. In industrial countries, foreignequity assets

and

liabilities are roughly 3.3and

3.9 percent ofwealth, whileforeign loan assets

and

liabilitiesaccountfor 1 1 percent ofwealth each.To

sum

up,we

observe that net foreign asset positions are small relative towealth

and

tend to be negative, exceptfor afew

rich countries.These

net foreignasset positions are remarkably persistent as afraction ofwealth,

and

mostly consistofforeign loans rather thanforeign equity holdings. This picture that

emerges

fromthe data is so clear that

we

think itshould constitute themain

target ofany

successfultheoryof international capital flows.

It

seems

safeto argue that such a theory requires at leasttwo ingredients.To

explain the strong positive association

between

wealthand

netforeign assetto

move

from richto poor countries. Natural candidatesfor this role are diminishingreturns atthecountry level

and

country-specific production risk. If either ofthese twoforces are present, the risk-adjusted rate of return to capital declines as

more

capitalis invested in a country, creating

an

incentive to investin countries thathave

littlecapital. Inthe

absence

ofa counten/ailing force, this incentivewould onlybe

eliminated if capital stocks

were

equalized across countries.Hence

the theoryneeds

asecond

ingredient to explainwhy

net foreign assetpositionsare so small.^

A

popularview isthatthetheoryjustneeds

to recognizethatrich countries

have

betteraggregate productionfunctions,and

this iswhy

investorskeep most

oftheircapital in rich countrieseven

in the presence ofdiminishing returnsand

production risk. While this is likelyto betrue tosome

extent,we

look elsewhereforthe

second

ingredient ofthetheory, forthree reasons. First,we

findthat standardvariables

we

thinkare associated with betteraggregate production functions(human

capital, quality ofinstitutions,

and

others)seem

to beeither unrelated to the net foreign asset position ofa country or, alternatively, explain very little ofitsvariation(See Table 3

and

the discussion of itbelow). Second, while better aggregateproduction functions in rich countries

can

explainwhy

netforeign asset positions aresmall, theycannotexplain

why

grossforeignequity positions are alsosmall.To

theextent that investors

have

a desireto diversify production risk, the theorywould

predict thatthey

choose

largegrossforeign equitypositions that are roughlybalanced. Finally, betteraggregate production functions in rich countriescannot

explain

why

most

international trade consists ofloans ratherthan equity. While bothassets are useful to transfer capital across countries, equityhas the additional benefit ofallowing countries to share production risk

and

should therefore always bepreferred over loans.

Why

are observedforeign equity positions so small?Why

areforeign loans ratherthan foreign equity the assetthat is

most

traded internationally?To

answer

thesequestions,we

would stillneed

toadd

additional elements tothetheory anyway.

Inthis

paper

we

explore the alternative hypothesis thatsovereign risk mightbe

thesecond

ingredient thatthetheory needs.^ Inthepresence

ofthissort of risk,domesticcapital offers domestic investors notonly the value ofits productionflow, but

alsoa

hedge

against the risk offoreign default. This creates ahome

bias inthedemand

for capital that mightexplainwhy

net foreign asset positions are small.Should

we

also expectthat sovereign risk leadsto small grossforeign equitypositions? Is it

even

possible that sovereign risk explainswhy

most

international tradein assets consists ofloans ratherthan equity?

The

answers

tothesequestionsdepend

cruciallyon

theconsequences

forinvestors ofaforeign default.Assume

first thatifa country defaultson

itsforeign obligations, foreigncountries respond by seizing the assetsthat this country

owns

abroadand

then usingthese assetsto (partially)

compensate

creditors.Assume

alsothatthe process by which assets are seizedand

transferred to creditorsdoes

not give rise toany

costs or loss of value. In this case, the loss suffered by creditors in the event ofdefault isdetermined bytheir netforeign asset position vis-a-visthe defaulting country.

To

minimizeexposure

to sovereign risk, investorsthenchoose

small net foreign assetpositions. But they

do

nothave

to hold small grossforeign equitypositions. Infact, tothe extentthat investors

have

adesireto diversify production risktheywould

againchoose

largeforeign equity positions thatare roughly balanced.Under

these assumptions, sovereign risk provides a rationaleforwhy

netforeign asset positionsare small, but it cannot explain

why

grossforeign equity positions aresmall. Neithercan it explain

why

most

international trade consistsofloans ratherthan equity.If

we

want

to hold sovereign risk responsibleforthe small gross foreign equity positions observed in the data,we

need

toremove

at leastone

oftheassumptions ofthe previous paragraph.

Perhaps

legalsystems

do

not allowcreditors to seize theforeign assets ofdefaulting countries. Or,

even

iftheydo, thetransfer ofownership^Obstfeld and Rogoff

[1996, p.349] define sovereign riskas referringto"...anysituation in

which a government defaults on loan contractswith foreigners, seizes foreign assets located

within itsborders, or prevents domesticresidentsfromfullymeetingobligationstoforeign

might involve large costs

and

asubstantial loss of value. Inthis case, investors'exposureto sovereign risk is

no

longertheir net foreign asset position vis-a-visthedefaulting country, but instead sonnefraction oftheirgrossforeign asset position.

Now

the existence ofsovereign riskcan

potentiallyexplainwhy

investorschoose

small grossforeign equitypositions.

With the help ofthe additional (and

we

think realistic) assumption thattransferring ownership ofequity is costlierthantransferring ownershipofloans,

sovereign risk can also explain

why

most

international trade in assets consistsof foreign loans ratherthanforeign equity. Investors issuing foreign loansand

equityarewilling to sell these assets ata discountthat reflectsthe value for

them

ofthe gainthey receive in the eventofdefault.''

What

is this gain?A

domestic investorwho

hasborrowed abroad

receives the full value ofthe loans. This gain is exactly equal totheloss experienced by theforeign investor.

A

domestic investorwho

has sold equityclaims toforeigners receives thefull value oftheequity, but loses

any

valuableadvantage

that foreign investors broughtto thefirm (experience, managerial skills,know-how,

access to bettertechnologyor relationships, firm-specific knowledge,and

so on). This gain is less than the loss experienced bytheforeign investor. Therefore

inthe event ofdefault,foreign loans give rise onlyto puretransferswhile foreign

equity creates losses. Whilethe latterallows investors to

hedge

against productionrisk, it is a

worse

hedge

against sovereign risk than the former. Ifthe desireto avoiddiminishing returns induces investorsto transfercapital from richto poorcountries,

foreign loanswill

be

amore

attractive asset ifsovereign risk is high relative toproduction risk. Thus, sovereign risk has also the potential to explain

why

loans arethe preferred asset tofinance capital flows.

The

notion that foreign equityand

loans are subject to sovereign risk is hardlynovel or controversial

among

observers of international financial markets.The

interesting issue is

whether

reasonable probabilities of default can quantitatively"*

This discount in loancontracts shows up Inthe Interest rate. Theevidence Isoverwhelming thatloanstodeveloping countries usually

command

a higherInterestratethan domesticexplain the

main

features ofcountry portfolios.To

determine this,we

constructasimple North-South

model

of international capital flows.The

production technologyexhibits diminishing returns at the country level

and

country-specific risk. In thismodel, the world

economy

experiences periods with substantial international trade inassets, which

end up

in a crisis period in whichSouth

defaultson

itsforeignobligations. North investors seize South'sforeign assets, butthis transfer ofassets is

costly.

The

defaultinitiates a crisis period in which international financial marketsshutdown.

Eventually, international trade in assetsresumes and

the cycle starts again.It

seems

clear thatthismodel

can, in principle, explain thefacts discussed above. Ifsovereign risk is sufficiently high, net capital flows willbe

small (Fact 1). If eitherdiminishing returns or country-specific production risk is important,we

shouldobserve a tendencyfor capital toflowfrom rich to poor countries (Fact 2).

To

theextentthat transferring ownership of foreign equity is costlierthantransferring

ownership of loans, grossforeign assetpositions should

be

smalland

consistprimarily of loans ratherthan equity (Fact4). Ifthe

model

generates persistence intheworld distribution ofwealth, this can naturallyexplain the persistence offoreign asset

positions (Fact3). It is

much

less clearhowever whether

thismodel

is able to providea reasonable quantitative description ofthe data.

A

perhapssurprising finding is that,even

in the presence ofreasonable diminishing returnsand

production risk, theprobability that international crises occur twice a century is

enough

to generate a setofcountryportfolios that are roughly consistent with the data.

The

paper is organized asfollows: Section I provides a briefdescription ofourdatabase

and

extensivelydocuments

the four factsmentioned

above. Section IIpresents the

model and

discusses itsmain

qualitativeand

quantitative implications.Appendix

A

provides a detailed discussion ofhow

we

constructed our database, whileI.

A

Description

of

Country

Portfolios

Inthis section,

we

describe themain

characteristics of countryportfolios usinga

new

database

covering68

countries from1966

to 1997.We

first providean

overview ofthe sources

and methodology used

to constructthe data.We

thensummarize

itsmain

features in theform offourfacts.Appendix

A

providesdetailson

the data

and

describeshow

we

accountforchanges

in thevalue ofstocks ofassets.1.1

A

New

Database

on Country

PortfoliosOur

databasecontains estimates ofdomestic capital stocksand

foreignassets of countries.^ In particular,

we

have

measures

forthefollowing quantities:k =

Domestic

capital stocke =

Domestic

equityowned

byforeign residents.e* = Foreign equity

owned

by domestic residents.I =

Loans

issued bydomestic residentsand

owned

byforeign residents.I* =

Loans

issued by foreign residentsand

owned

by domestic residents.We

measure

these quantities perdomestic resident in constant1990

US

dollars.We

define a=k+e*-e+r-l

and

f=e*-e+r-l asthe financialwealth or portfolioofthe countryand

its net foreign assets, respectively.We

referto a countryas

a creditor (debtor) ifits netforeign assets are positive (negative).

We

construct estimates ofeach

component

of financial wealth in two steps.First,

we

use the limited available information on stocksofthese assetsto determinean

initial value. Second,we

use flow dataand

estimates ofchanges

in the value ofthese assets to extend the initial stocks forward

and backward

overtime.We

relyon

^

We

abstractfrom othercomponents ofwealth suchas land, natural resources, andhuman

this

method

ofcumulating flowseven

forthose countrieswhere

more

stock data isavailable in orderto avoid a potential bias. Since long time series ofstock data are

available only fora

few

rich countries,using these as the primary sourcewould

essentially result in different

methods

beingused

to construct stocks for richand

poorcountries.

These

differenceswould

then contaminate ourinferences regardinghow

portfolios varywith wealth.

We

rely on data from anumber

of standard sources.We

obtain initial stocksofdomesticcapital from the

Penn

World

Tables,and

use flow dataon

gross domestic investment to buildup

stocks of capital valued inUS

dollars atPPP.

In ordertodetermineforeign holdings ofdomesticequity

and

domestic holdings offoreign equity,we

rely primarilyon

dataon

stocksand

flows of directand

portfolio equityInvestment reported in the International

Monetary

Fund's Balance ofPayments

Statistics Yearbook.We

againuse

the limited availableinformationon

stocksreported in this

and

a variety ofothersourcesto determine the initial level ofeach

assetfor

each

country,and

then use corresponding flowdata from the balanceofpayments

to construct stocksfor remainingyears. Finally,we

combine

stock data onthe debts ofdeveloping countries reported in the

World

Bank's GlobalDevelopment

Financewith data

on

stocksand

flowson

debt from the Balance ofPayments

Statistics

Yearbook

to buildup

stocks ofborrowingand

lending forall countries in oursample.^

Our

sample

ofcountries is determined primarily by data availability.We

beginwith a

sample

of98

countries with population greaterthanone

millionand

percapitaGDP

greaterthan 1000

US

dollars atPPP

in 1990.Of

thesewe

discard25

countrieswith missing, incomplete, or inconsistentbalance of

payments

data. This leaves uswith an unbalanced panel of

73

countries spanningon

average25

ofthe yearsbetween 1966 and

1997. Inthe empiricalwork

thatfollowswe

restrict attention toa®

We

assume

throughoutthat stocksofdebt reported inthesesources constitute solelytheassets and liabilities ofdomestic residents.

To

theextentthatthese reflectdebt issued byorowed

toforeign-ownedfirmsoperating in the country,we

are overestimating the loan assetsand liabilities ofdomestic residents. Given that foreign holdingsofdomesticequityare small

set of

68

countries excluding fivetransition economies. Table 1 liststhese countriesclassified by geographical region.

As

the table shows, oursample

includes basicallyall industrial countries

and

a substantialnumber

ofdeveloping countriesfrom allregions ofthe world.

The

countries in oursample

accountforover90

percent ofworld production

and commodity

trade. It is reasonabletothink that these countriesalsoaccountfora similar fraction ofworld trade in assets. ''

Despitethis wide

coverage,

we

do

not findthat netforeign assetssum

tozero across countries in oursample. Inthe

case

ofclaimson

equity,we

find thatthesum

ofall countries reportedclaims

on

foreign equityison

average about3 percent less than reported foreignclaims

on

domestic equity. In the case of lending the discrepancy is larger, with worldreported borrowing exceeding lending by about 12 percent. While these

discrepancies are nottrivial, they are ofa

comparable

order ofmagnitudetowell-known

discrepancies in flowson

foreign assets.1.2

Main

Features

of

Country

PortfoliosInthis subsection

we

examine

themain

features ofcountryportfolios using thedatabase described above.

We

organize the discussion around fourmain

facts orfindings.

Fact 1

:

Netforeign assets

as

a

share of wealth are smalland

negative formost

countries.Figure t

shows

the distribution ofthe shareofforeign assets in wealth,—

,

a

pooling the available

1717

observations forall countriesand

years. Overwhelmingly,net foreignassets representa small fraction ofthe wealth ofdomestic residents.

''

Our procedureresults inestimates ofwealth thatare very small (and occasionally negative)

forafewcountry-year observations, correspondingtocountries with very large external debt.

We

excludethese observations by limitingthesample tothosewherethe ratioofwealth toRoughly

80

percentofthe country/year observations are lessthan20

percent inabsolute value. Also, about

80

percent ofthecountry-yearobservations are negative.Perhaps

Figure 1 is concealing important variation across regionsand

overtime in the sizeand

sign ofthe net foreign asset position.To

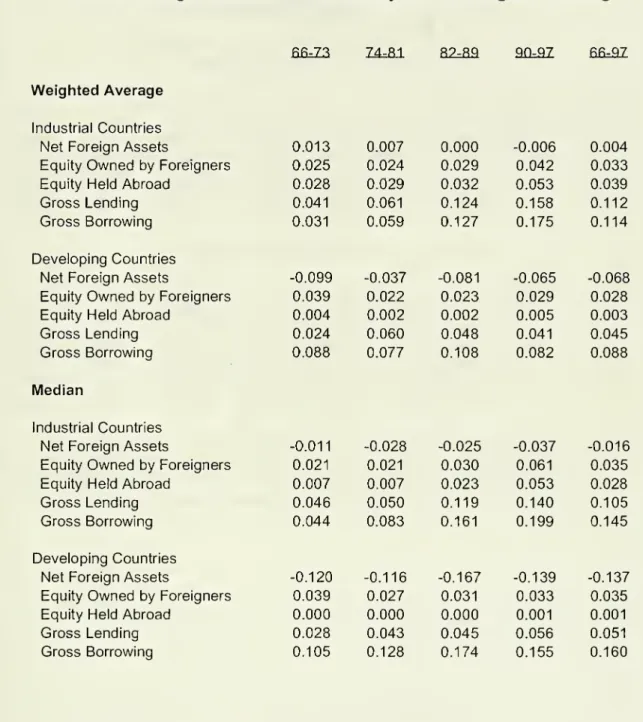

rule outthis possibility, Table 2reports theshareofnetforeign assets in wealth, aggregating across countries in

different regions

and

time periods.The

toppanel reportswealth-weighted averages,and

the lower panel reports the shareforthe typical (median) countryineach group

and

period. Clearly, thefinding thatmost

countrieshave

a small butnegative netforeign asset position holds across regions

and

overtime.Since net foreignasset positions are small relative to wealth, it follows that

there is a strong relationship

between

countries' financialwealthand

theircapitalstock.

To

see

this, Figure 2 plots the capital stock, k, against financial wealth, a,averaging the available years over the period

1966-1997

foreach

country.A

simpleregression ofthe capital stock

on

domesticwealth deliversand

R^of98

percentand

a slope coefficient of 0.93. Clearly, the world distribution of capitalstocks is very close

to the world distribution ofwealth. This

does

notmean

however

that differencesbetween

these two distributions arerandom

or uninteresting. Although the slopecoefficient

appears

tobe

very close to one, the null hypothesis thatthis coefficient isone

isrejected atconventional significance levels.We

also rejectthe null hypothesisthatthe intercept is zero. That is,

on average

the capital stockexceeds

wealth in poorcountries

and

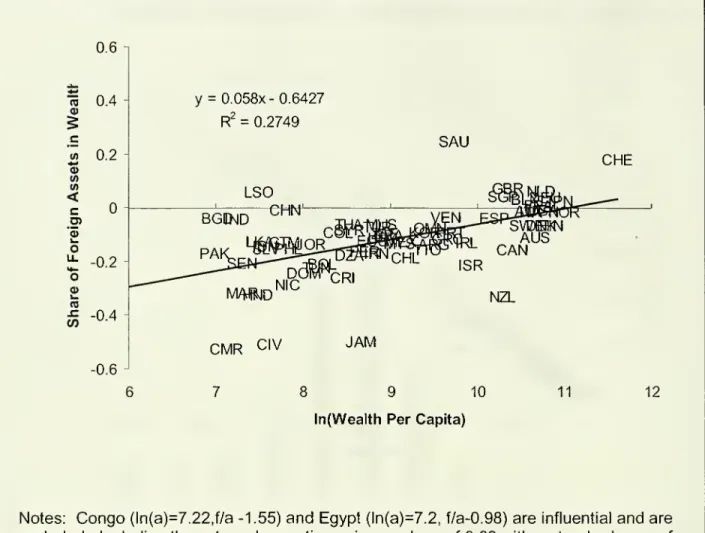

is less than wealth in richcountries. This leads us tothe nextfact:Fact 2:

The

share of netforeign assetsin the countryportfolio increases with wealthin across-section of countries.

The

strong positive associationbetween

the share of netforeign assetsand

wealth is apparent in Figure 3, which plotsthe

average

shareof net foreign assets inwealth,

—

, againstthe logarithmofwealth, ln(a), foreach

country over 1966-1997.a

Virtually all (44 out of47) developing countries are debtors, as aretwo-thirds of

industrial countries (14 outof21). Tiie ten creditor countries in our

sample

are mostlyrich industrial countries (Belgium/Luxembourg, Switzerland,

Germany,

France, UnitedKingdom,

Japan,and

the Netherlands),and

three developing countries (SaudiArabia, Singapore,

and

Lesotho).^The

relationshipbetween

wealthand

netforeignasset positions holds acrosssubperiods.

The

first row ofTable 3 confirmsthat the simple results in Figure 3(shown

in the firstcolumn) hold acrossthe differentsubperiods(shown

in theremaining columns).

The

estimated coefficients range from 0.04to 0.08and

aresignificantly differentfrom zero in

each

subperiod.The magnitudes

ofthesecoefficients indicate that

when

wealth doubles, the share offoreign assets in wealthincreases bythree to six percentage points. In the next

row

ofTable 3we

introduceregional

dummies.

With the exception ofthe first subperiod, thecoefficienton

thelogarithmofwealth increases slightly,

and

remains significantlypositive. Inthe thirdrow

ofTable 3we

check

whetherthechanges

in the wealth elasticity across periods isan

artifactofthechanging composition ofthesample

by restricting attention to abalanced panel of8-yearaverage observations.

The

resultsdo

notchange

substantially.

There

are reasonsto think thatthe relationshipbetween

wealthand

the net foreign asset position iseven

stronger thanwhat

a simple regressionwould

find. It iseasy

to think offactors thatare positively correlated with wealthand

are likelyto benegatively correlated withthe net foreign asset position ofa country. First, wealth is

stronglycorrelated with

human

capital, technologyand

institutional quality, all ofwhich raisethe returns to capital

and

make

foreign assets less attractivefor rich countries. Second, the variability ofreturns is also negatively correlated with wealth,making

foreign assets less attractive for rich countries. Third, theremay

also bescaleeffects

whereby

returnsare higher insome

ofthe larger, richereconomies

in oursample. All ofthese

arguments can be

summarized

bysaying that it is likelythat richLesotho is

somewhat

ofan anomaly, as itruns large current accountsurplusesreflectingprimarilyworkers' remittancesfrom SouthAfrica.

countries

have

better aggregate production functionsand

therefore findforeignassets less attractive.

To

the extentthat this is the case, the simple regressionsofthe net foreign asset positionon

wealth contain omitted variables that biasdownwards

the slopecoefficient.

We

therefore introduce anumber

ofadditional control variablesinto the regression.

We

proxyforhuman

capital with thenumber

ofyears ofsecondary

education in the workforce,and

controlfor scaleeffects using thelogarithmof population.

We

includeopenness

to international trademeasured

astrade

volumes

as a share ofGDP,

financial depthmeasured

as the ratio ofM2

toGDP,

government consumption

as a share ofGDP,

and

an indexofcivil liberties, asproxiesfor thequality ofthe institutional environment.

We

measure

thevariability ofreturns using the standard deviation ofreal per capita

GDP

growth overthe indicatedperiod. Finally,

we

include a set of regionaldummies

to controlforotherunobserved

region-specific heterogeneity.

The

remainderofTable 3summarizes

theresults ofthisaugmented

regression. Averaging overall years, thecoefficient

on

wealth rises to 0.07and

remains very significant. Consistentwith the view thathigh levels of

human

capitalmake

domestic capitalmore

attractive,we

findthatyears ofsecondary educationenters negativelyalthough not quite significantly atthe 10 percent level.

Somewhat

surprisingly, population size enters positively, suggesting thatthere

may

be

diseconomies

ofscale orcongestion effects thatmake

domestic capital less attractivein large countries. Public

consumption

as a share ofGDP

enters negativelyand

approaches

significance atthe 10 percent level, whichmay

reflectan

increaseddemand

forforeign loans tofinance public consumption. Finally, financial depthenters positively

and

significantly. Thismay

reflect thefact that countrieswithwell-developed

financial marketshave

lessneed

for recourse to international financialmarkets.

The

remaining control variables, openness, civil liberties,and

the volatility ofgrowth

do

notenter significantly. Although themagnitude and

significance ofthecoefficients

on

these variables differssomewhat

across subperiods, the results arequalitatively similar tothose obtained in thefirstcolumn.

From

Table 3we

can also obtain asense

ofthemagnitude

and

relativeimportance ofwealth relativeto otherfactors as adeterminant offoreign assets

positions. Consider the regression in thefirst

column

ofTable 3based on average

data over the period 1966-1997.

A

one

standard deviation increase inthe logarithm ofwealth (which correspondsto roughly athree-fold increase) leads to roughly

two-thirds ofa standard deviation increase inthe net foreign asset position, or about 10 percentage points. In contrast, a

one

standard deviation increase in the remainingsignificant control variables leads to

an

increase (inabsolute value) ofonlyone-third ofa standard deviation inthe the net foreign asset position. Anotherway

to see theimportance ofwealth in explaining the cross-country variation in foreign assets is to

perform a variance decomposition ofthefitted values from these regressions.

The

bottomrow

of Table 3reports the share ofthe variance in predicted foreign assetsthat can

be

attributed towealth.^ Averaging overthe entiresample

period,we

findthat almost

60

percent ofthe cross-countryvariation in predicted foreignassets isdue

to cross-countryvariation inwealth. In all butthe first subperiod

we

similarly findthatthe majority ofthe variation in predictedforeign assets is

due

to variation in wealth.Fact 3:

The

share ofnetforeign assetsin the countryportfolio ispersistent overtime.Figure4 plotstheshare ofnetforeign assets in wealth in a given country

and

year

on

thevertical axis, against its value laggedone

year (inthefirst panel), fiveyears (in the

second

panel)and

10 years (in thethird panel)on

the horizontal axis,pooling all country-year observationsoverthe period 1966-1997.

From

thesethreefigures it is clear that the shareofforeign assets inwealth is very persistent.^"

The

®

We

useadecomposition ofthevarianceofthe

sum

oftwocorrelated randomvariablessuggested byKlenow and Rodriguez-Clare[1997]. In particular, ifZ=X+Y, they define the

shareofthevarianceofZ attributableto

X

as COV(X,Z)A/AR(Z). This numberhas thefollowing natural interpretation: If

we

observethatZ

is onepercent above itsmean

butwe

didnotobserve

X

andY

separately, thenwe

would inferthatX

is COV(X,Z)A/AR(Z) percentabove its

mean

value.We

applythis defining Z asfitted foreignassets, andX

as the estimated coefficienton wealth multiplied bywealth.^°

Thisfact

was

also noted by KraayandVentura [Forthcoming] in a smaller sampleof 13OECD

economies,who

argue thatthisobservationcan explain thelong-standing puzzleraised by Feldstein and Horioka [1980].

simple correlation

between

the shareofforeign assets in country portfolios in agivenyear

and

thesame

share laggedone

year is 0.96.Even

over a 10-year horizon thesimplecorrelation is a respectable 0.55. Thisvery strong persistence ofthe share of

foreign assets in country portfolios is all the

more

surprisingwhen

one

considershow

small foreign assets are relative to wealth. In our

sample

the typical (median) countryholds roughly

-10

percentofits wealth in foreign assets,and

its ratio ofwealth toGDP

is around 2. This impliesthata current account surplusof5 percentofGDP

sustainedfor only fouryears

would be

sufficient to entirely erase a country's netforeign asset position. Yet in thedata

we

see

that netforeign assets as a share ofwealth

on average

barelychange

overthis horizon, as indicated by the estimatedslope coefficients which are very closeto one.

The

pooled data in Figure 4 neverthelessmask

some

interesting variationovertimein the persistenceofforeign assets in country portfolios. In Figure 5

we

disaggregate theannual persistence in thetop panel ofFigure4 by year. For

each

year indicated

on

the horizontal axis,we

regress the share offoreign assetsin wealthon

a constantand

its one-yearlag,and

then plotthe resulting slope coefficientson

the vertical axis as a

dashed

line.The

solid lineshows

a three-yearcenteredmoving

averageofthese estimated slopes.

When

this slope is greaterthan (less than) one, the foreign assets ofall countrieson average

expand

(contract).From

themid-1970s

to the mid-1980s, the slopes are all greaterthanone. This reflects primarilythe rapid

buildupofdebtofdeveloping countriesfinanced by borrowing from rich countries

and

oil producers, followed

by an

even

greater increase intheir recorded debts asmany

ofthese countries

suspended

payment

during the debtcrisis ofthe 1980s.As

thedebt crisis

was

eventually resolved in the late 1980s, the portfolios ofall countriescontracted

and

theslopes fallbelow

one.Somewhat

surprisingly, the estimated slopeis near

one

during the 1990s, providing little evidence ofsystematic increases intheshare ofnetforeign assets in country portfolios duringthis period.

Why

isthe netforeign asset position as ashare ofwealth so persistent?One

immediate possibility is thatthe persistenceofnet foreign assets reflectsthe

persistence ofwealth, which

we

have

seen

to bean

important determinant ofthecross-countryvariation in netforeign assets.

We

investigatethis iiypothesis empirically by regressing thechange

in netforeign assetson

thechange

in thelogarithm ofwealth

and

thechanges

in the othercontrolvariables considered in Table3, using the three eight-year

changes

implied bythefour 8-yearaveraged

periodsusing in Table 3.

We

then perform thesame

variance decomposition as beforetodetermine

what

shareofthe variation inchanges

in netforeign assets aredue

tochanges

in wealth.We

find thatbetween 40

percentand 70

percentofthe variation inchanges

in net foreign assets canbe

attributed tochanges

in wealth. This suggeststo us that persistence in wealth is an important source ofpersistence inforeign

assets.

Fact4:

Gross

foreign assetpositions aresmalland

consistmostlyofforeign loansratherthan foreign equity.

Net foreign assets consistofnet claims

on

foreignequity (e*-e)and

netlending abroad, (l-l*).

We

illustrate the relative importance ofthe latter in explainingthe cross-country variation in country portfolios in two ways. Table 4

shows

thecomposition offoreign assets as theyvaryacross regions,

income

groups,and

time.Averaging overall years, claims

on

foreign equity consist ofonly0.3 percent ofthewealthofdeveloping countries, while foreign claims

on

domestic equityaccountfor2.8 percent ofwealth.

Among

industrial countriesclaimson

foreign equityand

foreignclaims

on

domesticequityare onlysomewhat

largerand

consist ofonly 3.3percentand

3.9 percentofwealth." In contrastgross borrowingand

lending accountfor 8.8percent

and

4.5 percent ofwealth ofdeveloping countries,and

1 1 percent ofwealtheach

for industrial countries. Finally, it is interesting to notethatthe shareofgross borrowingand

lending in thewealth of industrial countries ismuch

larger than that ofdeveloping countries, especiallyduring the 1990s.

"

A

largeliterature hasdocumentedthatthe holdingsof foreign equity of investors in afewrich countries are very small (Frenchand Poterba [1991],Tesar andWerner [1992] and others). Lewis[1999] provides an excellent surveyofalternativeexplanationsfor this empirical

regularity. Ourdata confirmsthat itapplies toa

much

broaderset ofcountries and assets.In contrastwith Table

4

which focuseson

gross positions, Figure 6 providesevidence

on

the importanceofnet lending in explaining the cross-country variation innet foreign assets.

We

plot net lending as a share ofwealthon

the vertical axis,and

the share of foreign assets in wealth

on

the horizontalaxis, averaging overthe period1966-97.

The

top panelshows

the results for all countries, while the bottom panelshows

thesame

informationfor industrial countries only. Sincethe slope ofthis relationship is nothingmore

than the covariancebetween

netforeign assetsand

netlending divided by the variance ofnetforeign assets, this slope can

be

interpreted asthefraction ofthe variancein net foreign assets attributable to variation in net lending.

In ourfull

sample

ofcountriesthisfraction is82

percent. Forthe developing countries in oursample

this is not surprising at all, sincewe

have seen

thatgross equitypositions are small.

What

ismore

surprising isthatthesame

number

applies to industrial countrieswhere

cross-border claimson

equityaremuch

more

prevalentthan in developing countries.

From

this evidencewe

conclude thatmost

ofthecross-country variation in net foreign assets

can be

attributed todifferences in netlendingratherthan inforeign direct

and

portfolio equity investment.To

sum

up,we

have

seen

thatthe share ofnet foreign assets in countryportfolios is small

and

typically negative (Fact 1), exhibits a strong positiveassociation with wealth in a cross-section ofcountries (Fact 2), is remarkably

persistent overtime (Fact3),

and

consists primarily offoreign loans ratherthanforeign equity (Fact 4).

II.

Towards

an

Explanation

of

Country

Portfolios

We

next develop amodel

thatemphasizes

the interplay ofdiminishing returns,production risk

and

sovereign risk in aworld populated byhomogeneous

mean-variance investors.^^ Diminishing returns

and

production risk implythat therisk-adjusted rate ofreturn to capital declines as

more

capital is invested in a country. Ifthese

were

the only forces atwork,we

would observe all countries choosing thesame

portfolios,and

the world distribution of capital stockswould

be

determined bythe equalization ofrisk-adjusted rates ofreturn. Sovereign risk

however

generates ahome

bias in thedemand

for capital. Ifthiswere

theonly force atwork, countrieswould

hold onlydomestic capitaland

the world distribution of capital stockswould

mimic

the world distribution ofwealth.The

set ofcountry portfoliosand

the worlddistribution of capital stocks is

shaped

bythe interaction oftheseforces.11.1

A

Model

of

InternationalCapital

Flows

The

world containstwo countries, Northand

South;one

factor ofproduction,capital;

and

a singlegood

that canbe

used

for consumptionand

investment. Thisgood

isused

as the numeraire.Each

country contains a continuum of identicalconsumer/investorsthat evaluate

consumption sequences

as follows:(1) EJlnc(t)e"^' dt (5>0)

where

c is consumption.The

time index will be omittedwhenever

this is notconfusing. Throughout,

we

usean

asterisk todenote South variables.We

assume

North has higher initialwealth than South, i.e. a(0)>a*(0).

^^The

keypropertyofthese investors is thatthe shareofeach assetintheir portfolio does not

depend ontheirwealth, butonlyonthe

menu

ofavailable assets. By homogeneous,we mean

thatall Investors haveidentical (homothetic) preferences, although possiblydifferentwealth

and

menu

ofavailable assets.The

productiontechnology is quite simple. Let kand

k*be

thecapital stocksofNorth

and

South.To

produce

one

unitofcapital,one

unitoftheconsumption

good

isrequired. Since capital is reversible, the price of

each

unitis alwaysone and

its returnis the flowofproduction net of depreciation. Letco

and

co*be

two standardWiener

processes with independent increments. That is, E[do)]= E[dco*]=0, E[dco^]=E[dcL)*^]=dt

and

E[do>do/]=0.Then

the flow ofproduction netofdepreciation is given byTtdt+adcain North

and

7T;*dt+adco* in South;where n

and

n* are short-hand for 7t=9k"^and

7i:*=0k*"'' (0<y<1; 9>0)and a

is a positive constant.The

parameterymeasures

the strength ofdiminishing returns which, for simplicity, are treated here asan

externality or congestion effect.^^The

parametera

measures

the importance ofcountry-specific production risk. Therefore, thisformulation

assumes

thatbothcountries

have

thesame

technologyand

embodies

thetwo

forcesthatmake

therisk-adjusted rate of return to capital decreasing in the capital stock

and

create incentivesforcapital to

move

from rich to poorcountries.Domestic

investorsown

the domesticstock of capitaland

can enter into loanand

equity contracts with foreign investors. International loans promisetopay an

instantaneous interest rate rdt. At the beginning ofthe period, the lender gives the

principal tothe borrower. Atthe

end

ofthe periodthere are two possible outcomes.The

borrower might honor its promise, in whichcase

the lender receives the principal plus interest.The

borrower mightalsodefaulton

its promise, in whichcase

theborrower

keeps

the principaland

interestand

the lender receives nothing.A

shareofNorth (South) equityhas pricev (v*)

and

promises topay

the net flow ofproductiongenerated by

one

unitofNorth (South) capital. At the beginning ofthe period thebuyergives the value ofthe equityto the seller.

The

sellerprovides the buyerwith aunitofcapital

and

allows him/herto operate the production technology.Once

again,at the

end

ofthe period there aretwo possible outcomes.The

sellermight honor itspromise, inwhich

case

the buyerreceives the value ofthe equityand keeps

the netflowofproduction.

The

sellermight alsodefaulton

its promise, in whichcase

the^^At

thecostoffurthernotation,

we

couldgeneratethisdependence byassumingthere isaproductionfactor thatis not priced. Sincethis is wellknown,

we

dispense withtheformalities.seller

keeps

the value ofthe equityand

then pays a costX (0<X<1)to repossess theunitof capital

and

the net flowof production.The

buyer receives nothing. Let I betheamount

of lending from North to Southand

e (e*)be

thenumber

ofNorth (South)shares

owned

by South (North).It isevidentthat international loan

and

equity contractswill beused

inequilibrium if

and

onlyifthe probability thatthey arehonored

ishigh enough. Thisobservation raises a familiartime-inconsistency problem. Since

governments

cannotpunishforeign citizens, internationaltrade in assets relies

on

governments'willingnessto punishtheir

own

citizens iftheydefaulton

theirobligations towardsforeigners. 'Ex-ante' both

governments

would like tocommit

todo

thisand

allowinvestors toexploit beneficial trade opportunities.

However,

'ex-post'governments do

not

have an

incentive to punish default ifthe benefitsexceed

the costs.The

benefits of default are clear. But,what

are the costsofdefault?We

shallassume

they varyovertime. Let s={0,1}

be

the state ofthewortd. During 'normal times' (s=0) bothcountries can credibly

commit

to retaliatewith penalties that are largeenough

toensure that default never occurs. During 'crisis periods' (s=1) countries cannot

credibly

commit

to penaltiesbeyond

retaliation in kind.As

a result, if s=1 South (North) defaults ifits netforeign asset position is negative enough, i.e.ve-l-v*e*<-Ae*

(v*e*+l-ve<-A,e).^'* Leta

dtand

|3dtbe

the probabilitiesthat the wortd transitionsfrom

8=0

tos=1and

vice versa;and

assume

thesetransitions are independentofproduction shocks, E[dcods]=E[dca*ds]=0.

The

value ofds is revealed afterthebeginning-of-penod

payments

of loanand

equity contractshave

alreadybeen

made.

What

is the equilibrium probabilityofdefault?Assume

investors believe theprobability of default is zero. Ifa*>a(1-A), the country portfolios

chosen

by investorsare consistentwith this belief.^^ In this case, the equilibnum probability ofdefaultis

^'*

The seminal papers on sovereign risk andthe abilityofvarioustypes of penaltiestosustain trade areEaton and Gersovitz [1981] and Bulowand Rogoff [1989]. Eaton and Fernandez

[1995] and Obstfeldand Rogoff[1996, chapter6] aretwoexcellent surveysofthis topic.

^ If investors believe thatthe probability of defaultiszero, the equilibrium of the model implies

v=v*=1, k=k*=(a+a*)/2, e=a*/2, e*=a/2and 1=0. Naturally, no countrydefaults ifs=0. Buteven ifs=1, Northdoesnot default and neither does Southifa*>a(1-X).

zero

and

sovereign riskis simply notan

issue.We

shall thereforeassume

fromnow

onthat a*(0)<a(0)-(1-X). In this case, the equilibrium probability of default is

state-dependent.

Assume

the initial state is s=1and

investors believe that defaultoccurs ifthe state

does

not change. Then, investorsdo

not purchase foreign loansand

equitysince they expectdefault to occurwith probability close toone, i.e. 1-|3dt. But then

both countries are indifferent

on whether

to default or not.To

ensurethatan

equilibrium exists

we

assume

theydefault(on their non-existentforeign obligations)so thatthe beliefs ofinvestors are consistent. This implies thatthere is

no

trade Inassets during 'crisis periods'.

Assume

nextthatthe initial state iss=0 and

investorsbelieve that default occurs ifthe state changes. In this case, investorswill

purchase

foreign loans

and

equitysince default occurs onlywith avery small probability, i.e. adt. Ifthis probability is not too large, thechosen

country portfolios are consistentwith South defaulting in the unlikelyeventthe state ofthe world changes. Otherwise,

there is

no

Nash

equilibrium in which the countryfollows a purestrategy.^®We

shallrestrictthe analysis to the case in which

a

is small. This implies thatadt

is theequilibrium probability of default in 'normal times'.

To

sum

up, theworldeconomy

exhibits periods oftrade in assets thatculminate in crises (s transitions from

s=0

to s=1) inwhich the debtor countrydefaults.

The

parametersa

and

A.measure

the probabilityand

the destructiveness ofthis crisis. After itoccurs, a period

ensues

in which there isno

trade in assets.Eventually, international trade in assets

resumes

(stransitionsfrom s=1 tos=0)and

the cycle starts again. Although in normal times there might

be

substantial trade inassets, the (small) probability that acrisis occurs

has an

important effecton

thestrategies followed by investors.

We

describethese strategies next.^^

We

canconstruct a mixed-strategyNash equilibrium asfollows: Let p bethe probabilityof defaultthat leads investorstochoosecountryportfolios suchthatve-l-v*e*=-Ae*. South is

indifferent between defaulting ornot. There is an equilibrium in which Southdefaults with

probability (p/a)dt.

11.2

Investment

Strategies

In crisis periods, the only decision that investorsface is

how much

toconsume

and

save. This limited choice isembedded

inthis budget constraintwhich appliesonlyduring crisis periods:

(2)

da

=(7ia-c)dt

+aadco

In normal times there istrade in assets,

and

we

can writethe budgetconstraint ofthe representative investorin North asfollows:

(3)

da

= [7r(k-e) +7i*e*+rl-c]dt

+(7-[(k-e)d(o+e*d(o*]+[(v-A)e-v*e*-l]ds

where, ofcourse, the following restriction applies:

(4) a=

k-ve

+

v*e*+l

The

firsttwo terms ofthe budget constraint (3) arestandardand

show

how

theexpected return

and

volatilityofwealthdepends on

asset choice, conditionalon

thestate ofthe world not changing.

The

thirdterm describes the wealthshock

that theinvestorexperiences atthe onset ofa crisis period. Throughout,

we

rule out Ponzischemes

and impose

short-sale constraintson

the holdings offoreign equity. Thislast restriction is a logical implication ofsovereign risk.

To

determine the optimal consumptionand

portfolio rules, the representativeconsumer

in Northmaximizes

(1) subject to (2)-(4)and

thedynamics

ofassetphces

and

their return characteristics, i.e. the laws ofmotion ofr, v , v*, n, n*,a and

a*.Since the representative

consumer

is infinitesimal, he/she understands that his/heractions

have no

influenceon

these pricesand

their evolution.The

representativeconsumer

in the South solves a similar problem.Appendix

B

shows

that thefirst-orderconditions associated with the investor's problem can

be

written as follows:(5) c

=

6a

(6) 2k-e

7T:-p=

a

a (7) a r p=

a-_

^k-^e

2k-e

,, , a (8)p-v-n

=

-a

+

a(A-v)

ak-Xe

e*

(9) If7i*-r-v*<0, e*=0. Otherwise, re*

-p

•v* =a^ +a

vk-Xe

where

pis the multiplierassociated with constraint(3) divided bythe marginal utility ofwealth. This quantity can

be

interpreted as the risk-free rate that applieson

loansbetween

North residents.A

similar set offirst-orderconditions applyto South.Equation (5) is thefirst-order condition associatedwith c;

and

shows

thefamiliar result that

consumption

equalsthe annualized value ofwealth. Sincethe rate oftime preference isused

as the discount factor, theconsumption

rule is independentofthe state ofthe world.

Equations (6)

and

(7) are the firstorder conditions associated with kand

I;and

describe

how

investors value productionand

sovereign risk, respectively. Equation(6) says thatthe

premium

for holding production risk, n-p, is the covariancebetween

the return to

one

unitof capitaland

one

unitofthe investor'sportfolio, a^(k-e)/a.Equation (7) says thatthe

premium

forholding sovereign risk, r-a-p, is alsoproportionalto the covariance

between one

unit ofloansand

one

unitofthe investor'sportfolio, i.e.

a

. Butsince this time the effectoftheshock

is 'large' ora

non-local,thefactor of proportionality is not

one

butthe ratioofthe marginal valueofwealth before

and

aftera crisis occurs, i.e. .k-Ae

Equations (8)

and

(9) are thefirst-orderconditions associated with eand

e*;and

describe the supplyofNorth equityand

thedemand

for South equity,respectively. Equation (8) can

be

interpreted asdetermining the price atwhich North iswilling to sell equity.Each

share sold bythe North reducesincome

byone

unitof output, but also provides a gain of 1-A.in the eventofacrisis. This iswhy

equitywillbe

sold at adiscount, i.e. v<1. Using Equations (6)and

(7),we

find thatthis discount is equal tothe gain obtained in the event of a crisistimes the price ofone

unitofincome

in this state oftheworld, i.e. 1-v=(1-^)—

-. Equation (9) defines the

r

demand

forSouth equity. Thisasset contains both production riskand

sovereign riskand

the requiredpremium

reflects just this.Thiscompletes the description ofthe model. Equations (4)-(9)

and

theircounterparts for Southjointly determine asset prices (p,p*,r,v,v*), the world

distribution of capital stocks (k,k*)

and consumptions

(c,c*);and

the pattern ofassettrade (e,e*,i) as afunction ofthedistribution ofwealth (a,a*)

and

technology(n,7i*,a,a*).

We

use this set ofequations toderive the cross-sectional implications ofthetheory. Then,the budgetconstraints (2)-(3)determine the lawofmotion ofthe

world

economy

asa function ofthe initial distribution ofwealthand

technologyand

the realizations ofthe shocks.

We

usethis additional set ofequationstoderive thetime-series implications ofthe theory.

11.3

Three

Examples

Before

we

embark

ina quantitative analysis ofthe model,we

discuss threeexamples

or special cases that help build intuitionon

the role ofthe differentforcesthatthe theory emphasizes. In these examples,

we

assume

the worldeconomy

startsin normal times

and

then ask:What

is the initial pattern oftrade in assetsand

how

does

it evolve overtime?EXAMPLE

#1: Leta^O

sothatthere isno

sovereign risk. Inthis case, there isno

discounton

international assets, i.e. p=p*=rand

v=v*=1. Since countrieshave

identical

and

homothetic preferences and, effectively, thesame menu

of assets,theychoose

thesame

portfolios.As

a result, there isno

borrowing or lending. Sincetechnologies are identical, both countries invest

50

percent oftheirwealth in domesticcapital

and

the restin foreign equity. Thus, halfoftheworld capital stock is located ineach

countryand

theworld interest rate equalsthe marginal product ofcapital:(10) k =k*

=

-^+ ^^ 2 (11) r=

e^a+a*v^

\ ^ JIf

one

interprets Northand

South as the set of industrialand

developingcountriesin Table 1,

we

have

that =0.8;and

netforeign assetpositions (as aa+

a*

percentage ofwealth) of North

and South

are37.5and

-150 percent, respectively.The

distribution of wealth is constant overtime, since both countrieschoose

thesame

portfolios

and

thereforehave

thesame

growth rate:da

da

(12)

^

=^^

=

(r-p).dt +-(dco

+dco*)a

a*

2 ^ ^An

implication ofthis is that netforeign asset positions are time invariant.The

predictions ofthisexample

are both well-knownand

dead

wrong.The

model

exhibitstwo featuresthat are present inthe data: net foreign asset positionsare positivelyassociated with wealth (Fact 2)

and

very persistent (Fact 3). But themodel

alsopredicts netforeign asset positions thataremuch

largerthan those in thedata (Fact 1). Italso predicts very large foreign equity positions

and no

borrowingand

lending, whilethe data

shows

thatcountries hold little foreign equityand

financemost

oftheirnetforeign asset positions with foreign loans (Fact4).

EXAMPLE

#2

: Leta^O

so thatthe only reasonwhy

capital flowsfrom rich topoor countries is to exploit higherrates ofreturn.

Now

foreign equityand

loans deliverthe

same

return in normaltimes. IfX=0, foreign equityand

loans also deliverthesame

return inthe event ofdefault and, consequently, the composition offoreignassets is indeterminate. IfX is strictly positive,foreign equity

becomes

adominated

asset. In this case, countries

do

not holdforeign equityand

finance theirnetforeignasset positions with foreign loans.

The

world distribution of capital stocksand

theworld interest rate are implicitlydetermined by:

(13) r

=

ek-^+a-k (14) r= ek*"^+a-(15) k+k*=

a +a*

k^ \3'Equations (13)

and

(14) describe thedemand

for Northand

South capital,and

Equation (15) is the market-clearing condition.

These

equationsshow

that sovereignrisk creates a

home

bias inthedemand

forcapital. Also, notethat theworld interestrate

exceeds

the marginal product ofcapital in both countries. This difference istherisk

premium

required tocompensate

lendersforsovereign risk.The

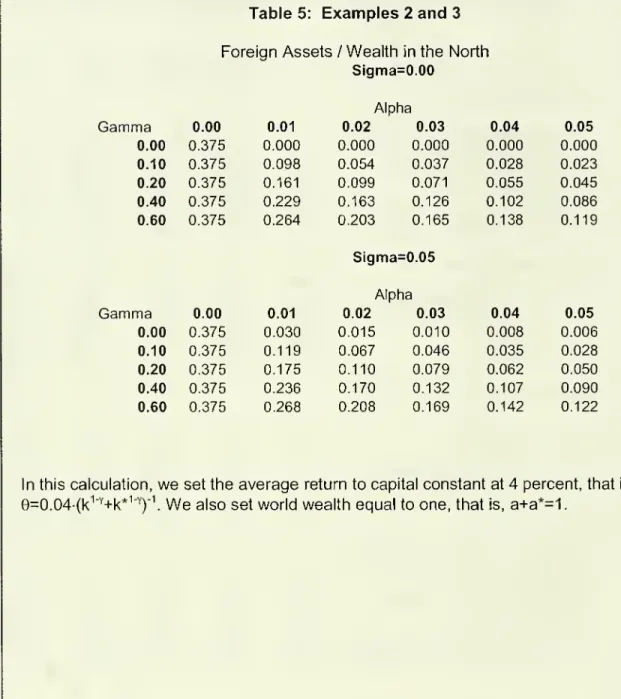

toppanel ofTable 5

computes

the foreign asset position of Northunder

alternativeassumptions

forY

and

a (Remember

the net foreign asset position of South is-A

times that ofNorth). Netforeign assetpositions for North

and South

range from zero (as a^'>=) to37.5

and -150

percent (asa^O).

What

are reasonable valuesfora

and

y? Forinstance,

a=0.02

is consistent with the 20'*^ century experience which features twoepisodes of large-scale defaults in the

1930s and

the 1980s. Since the expectedvalue ofaggregate production is 9k^'^, values of yaround 0.6 correspond to the

neoclassical growth model, while values of ynear

one

are close tothe lineargrowthmodel. Table 5

shows

that ifa=0.02 and

y=0.6, the net foreign asset positions ofNorth

and

South are 20.3and

-81.2 percent.These

numbers

are roughly halfofthose