Risk of Incident Cancer in In

flammatory Bowel Disease

Patients Starting Anti-TNF Therapy While

Having Recent Malignancy

Florian Poullenot, MD,

1Philippe Seksik, PhD,

2Laurent Beaugerie, PhD,

2Aurélien Amiot, PhD,

3Maria Nachury, MD,

4Vered Abitbol, MD,

5Carmen Stefanescu, MD,

6Catherine Reenaers, MD,

7,8Mathurin Fumery, MD,

9Anne-Laure Pelletier, MD,

10Stephane Nancey, PhD,

11,12Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet, PhD,

13Arnaud Bourreille, PhD,

14Xavier Hébuterne, PhD,

15Hedia Brixi, MD,

16Guillaume Savoye, PhD,

17Nelson Lourenc¸o, MD,

18Romain Altwegg, MD,

19Anthony Buisson, MD,

20,21Christine Cazelles-Boudier, MD,

22Antoine Racine, MD,

23Julien Vergniol, MD,

1and

David Laharie, PhD,

1le GETAID

Background: Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and history of malignancy within the last 5 years are usually contraindicated for

receiving anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents. The aim of this study is to assess survival without incident cancer in a cohort of IBD patients exposed to anti-TNF while having previous malignancy within past 5 years.

Methods:Data from IBD patients with previous malignancy diagnosed within the last 5 years before starting an anti-TNF agent were collected through a Groupe d’Etude Thérapeutiques des Affections Inflammatoires du tube Digestif multicenter survey. Inclusion date corresponded to the first anti-TNF administration after cancer diagnosis.

Results:Twenty centers identified 79 cases of IBD patients with previous malignancy diagnosed 17 months (median; range: 1–65) before inclusion. The most frequent cancer locations were breast (n¼ 17) and skin (n ¼ 15). After a median follow-up of 21 (range: 1–119) months, 15 (19%) patients developed incident cancer (8 recurrent and 7 new cancers), including 5 basal-cell carcinomas. Survival without incident cancer was 96%, 86%, and 66% at 1, 2, and 5 years, respectively. Crude incidence rate of cancer was 84.5 (95% CI, 83.1–85.8) per 1000 patient-years.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on

the journal’s Web site (www.ibdjournal.org).

Received for publication August 31, 2015; Accepted January 13, 2016.

From the1CHU de Bordeaux, Hôpital Haut-Lévêque, Service d’Hépato-gastroentérologie, University of Bordeaux, Bordeaux, Pessac, France;2Department of

Gastroenterology, AP–HP, Hôpital Saint-Antoine, ERL 1157 INSERM/UMRS 7203, DHU 12B, UPMC, Paris, France;3Department of Gastroenterology, Henri Mondor

Hospital, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris, Paris Est Creteil University, Paris, France;4CHRU de Lille, Hôpital Claude Huriez, Service des Maladies de l’Appareil

Digestif–Endoscopie Digestive, Lille, France;5Department of Gastroenterology, Cochin Hospital, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris and Paris V University, Paris,

France;6Hôpital Beaujon, Gastroentérologie, Maladies Inflammatoires Chroniques de l’Intestin et Assistance Nutritive, AP-HP, Université Paris VII, Clichy, France;

7Department of Gastroenterology, CHU of Liège, University of Liège, Belgium;8GIGA Research, University of Liege, Belgium;9Service d’Hépato–Gastroentérologie,

CHU Amiens, Université de Picardie Jules Verne, Amiens, France;10Department of Gastroenterology, Bichat Hospital, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris, Paris,

France;11Department of Gastroenterology, Lyon Sud Hospital, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Pierre Benite, France;12INSERM U1111, CIRI, Lyon, France;13INSERM

U954 and Department of Hepato-Gastroenterology, University Hospital of Nancy, Université Henri Poincaré 1, Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy, France;14Inserm CIC 1114 and

Institut des Maladies de l’Appareil Digestif, University Hospital, Nantes, France;15CHU de Nice, Hôpital de l’Archet 2, Service de Gastroentérologie et Nutrition

Clinique, Nice, France;16Department of Hepato-Gastroenterology and Digestive Oncology Hôpital Robert Debré, Reims, France;17CHU de Rouen, Hôpital Charles

Nicolle, Service de Gastroentérologie, Appareil Digestif Environnement et Nutrition Equipe Avenir 4311, Université de Rouen, Rouen, France;18Department of

Hepatogastroenterology, Hôpital Saint-Louis, Paris, France;19Département d’Hépatogastroentérologie, Hôpital Saint-Eloi, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de

Mont-pellier, MontMont-pellier, France;20Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Estaing, UMR 1071 INSERM/Université d’Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France;

21USC-INRA 2018, Microbes, Intestine, Inflammation and Susceptibility of the Host, Clermont-Ferrand, France;22Centre Hospitalier Régionnal de la Côte Basque,

Service de Gastroentérologie, Bayonne, France; and23Department of Gastroenterology, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), University Hospitals

Paris-Sud, Site de Bicêtre, Paris Sud University, Paris XI, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, Villejuif, France. Author disclosures are available in the Acknowledgments.

F. Poullenot, D. Laharie: study conception and design, study investigator, data interpretation, statistical analysis, drafting, and critical revision of the manuscript. P. Seksik, A. Amiot, M. Nachury, V. Abitbol, C. Stefanescu, C. Reenaers, M. Fumery, A.-L. Pelletier, S. Nancey, L. Peyrin-Biroulet, A. Bourreille, X. Hébuterne, H. Brixi, G. Savoye, N. Lourenc¸o, R. Altwegg, A. Buisson, C. Cazelles-Boudier, and A. Racine: study investigators. L. Beaugerie: investigator and critical revision of the manuscript. J. Vergniol: statistical analysis and critical revision of the manuscript.

Reprints: David Laharie, PhD, Service d’hépato-gastroentérologie—Univ, Bordeaux, Laboratoire de bactériologie, Hôpital Haut-Lévêque, CHU Bordeaux, 1 Avenue, de

Magellan, 33604 Pessac, France (e-mail: david.laharie@chu-bordeaux.fr).

Copyright © 2016 Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America, Inc.

DOI 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000741 Published online 26 February 2016.

Conclusions:In a population of refractory IBD patients with recent malignancy, anti-TNF could be used taking into account a mild risk of incident cancer. Pending prospective and larger studies, a case-by-case joint decision taken with the oncologist is recommended for managing these patients in daily practice.

(Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:1362–1369)

Key Words: inflammatory bowel diseases, previous cancer, anti-TNF, risk of incident cancer

I

nflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are disabling conditions affecting mainly young adults lifelong. During the last 2 deca-des, medical management of these diseases has hugely evolved for 2 major reasons. First, therapeutic goals have become more ambi-tious aiming to treat patients beyond symptom control to heal the gut mucosa and prevent digestive damages leading to surgeries.1Second, new paradigms have emerged with the advent of anti– tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents2,3 and larger and earlier

use of conventional immunosuppressants (thiopurines and meth-otrexate). Overall, IBD patients are now more exposed than before to immunomodulators that are conventional immunosup-pressants and/or biologics.

One of 3 to 4 European citizens will develop malignancy during their lifetime with a better prognosis today than before. Physicians are therefore more frequently facing patients with IBD who may receive an immunomodulator while having a history of previous cancer. However, few data have been available so far to help physicians make a decision on how to manage these patients, because of the following 3 main reasons: (1) previous cancer is an usual exclusion criterion in all clinical trials conducted on cases of IBD; (2) guidelines do not recommend any use of immunomo-dulators in patients who have had a malignancy within the last 5 years4; (3) in current practice, physicians are reluctant to use these

agents that could reactivate dormant micrometastasis.

Concerning conventional immunosuppressant use for treating IBD in case of previous malignancy, data from several case–control studies that included highly selected patients are suggesting that they have no major impact on the risk of new cancer or cancer recurrence.5–8Thus, this study aimed to assess the risk for incident cancer in a cohort of IBD patients exposed to anti-TNF therapy while having a history of malignancy within the past 5 years.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

All authors had access to the study data and they have reviewed and approved thefinal article.

Study Population

This study was a retrospective and prospective survey conducted from September 2011 to May 2013 by the Groupe d’Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du tube Digestif centers in France and Belgium.

Patients with the following selection criteria were eligible: age above 18 years, diagnosis of IBD—Crohn’s disease or ulcer-ative colitis—according to the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization criteria,9 treatment including at least 1 anti-TNF

agent (infliximab or adalimumab) administrated for refractory IBD, previous malignancy diagnosed and confirmed by histology within 5 years before starting anti-TNF therapy. Patients with IBD diagnosis following cancer diagnosis could be recruited. For pa-tients with a previous history of more than one malignancy, the most recent one was considered. Study schedule is shown in Figure 1.

All patients received treatment according to clinical need. Medications were those usually recommended in IBD, according to their licensed or published doses and frequency. Patients were informed by written notice of their participation. French Data Protection Agency (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés, registration number 914595) and investigational review board of each center approved the study.

Data Collection

Inclusion date was defined as the date of the first anti-TNF administration after previous cancer diagnosis. Medical records of patients were retrospectively reviewed and the following data were collected at inclusion: age, sex, smoking status, family history of IBD, IBD subtype (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) and phenotype according to the Montreal classification,10

extra-intestinal manifestations, previous treatment exposure–including steroids, thiopurines, methotrexate, anti-TNF and surgeries–and main reason for drug interruption (withdrawal, failure, or intoler-ance), anti-TNF agent used (infliximab and adalimumab), and indication (refractory luminal disease,fistulizing disease or post-operative recurrence for Crohn’s disease, refractory disease or severe attack of ulcerative colitis, or extra-intestinal manifesta-tions, or both).

Regarding the characteristics of the malignancy that occurred before inclusion, the following data were collected:

FIGURE 1. Study overview (median with ranges).

tumor site, histological type, lymph node and metastasis extension, Tumor Node Metastasis (TNM) classification if avail-able (the most accurate classification possible was used for the nonmelanoma skin cancers—NMSCs11,12), previous and current

cancer treatments (including surgery, chemotherapy, radiother-apy, or specific targeted therapy), and tumor status at inclusion (remission, palliative, current treatment).

During the follow-up period, from inclusion until July 2013, incident cancers and deaths were prospectively recorded. Incident cancers were recurrent cancers or new cancers, defined as cancer developed in a different organ from the organ involved in a previous cancer, or developed in the same organ but with an indisputably different histological type. For each incident cancer, data of diagnosis, management, and status at the end of follow-up (remission, palliative, under treatment, or death) were collected. NMSCs were classified separately.

Outcome Measures

The primary objective of the study is to determine survival without incident cancer during follow-up. Secondary objectives were (1) to determine the crude incidence rate of incident cancers in the whole study population; (2) compare IBD and cancer characteristics of patients with and without incident cancer; (3) assess incidence and survival rates without incident cancer according to immunosuppressant status, time interval between cancer diagnosis and inclusion with or without exclusion of NMSC; and (4) describe cases of incident cancer.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables, reported as median and range, were compared using the Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test for variables with abnormal distribution, and categorical var-iables with Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests where appropriate.

For survival analyses, time-dependent Kaplan–Meier anal-ysis for survival curves and log-rank test for univariate compar-isons were used. These analyses were conducted in the whole population, and after excluding patients with NMSC at inclusion. Patients’ IBD and cancer variables at baseline were com-pared between patients with and without incident cancer. The characteristics analysed were sex, age, family history of IBD, IBD subtype, extra-intestinal manifestations, smoking status, pre-vious treatments of IBD, age at diagnosis, lymph node and metastasis extension, other previous treatments, follow-up time since cancer diagnosis, and follow-up since inclusion for previ-ous cancer. Risk factors for the onset of incident cancer were analyzed by univariate logistic regression. A Cox proportional hazard model was used to test the independent effect of each variable on survival without incident cancer. Two-sided statisti-cal tests were used for all analyses. P , 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R soft-ware (version 3.1.0; http://cran.r-project.org)13 (using the

sur-vival package14) and using the SAS software (version 9.1.2;

SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Patients at Inclusion

A total of 79 patients were recruited within 20 participating Groupe d’Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du tube Digestif centers. Their main characteristics at inclusion are presented in the Table 1. To summarize, 49 (62%) were women, median age at inclusion was 47 years (range¼ 18–84), 61 (77%) had Crohn’s disease and 18 (23%) had ulcerative colitis; median disease duration was 12 (1–40) years. Regarding previous IBD treatments, 57 (72%) patients had been exposed to thiopurines before inclusion, 25 (32%) to methotrexate, and 25 (32%) had previous major abdominal surgery. Nine patients had IBD diag-nosed after cancer diagnosis. Among the 70 other patients, 35 (50%) had been exposed to anti-TNF before the previous cancer diagnosis, 26 had received infliximab, 3 adalimumab, and 6 had been exposed to both anti-TNF agents.

From cancer diagnosis to inclusion, 18 (23%) patients have been exposed to thiopurines, 10 (13%) to methotrexate, and 7 (9%) had had previous major abdominal surgery.

All patients received an anti-TNF treatment at inclusion of which 53 (67%) were treated with infliximab and 26 (33%) with adalimumab. Among the 61 patients with Crohn’s disease, anti-TNF therapy was given for refractory luminal disease in 42 cases, fistulizing disease in 9, postoperative recurrence in 8 patients and extra-intestinal manifestations in 2 patients (one with orbital myo-sitis and another with spondyloarthritis) associated in both cases

TABLE 1. Patients

’ Characteristics at Inclusion

Total number of patients 79

Women, n (%) 49 (62)

Median age at inclusion, in years (range) 47 (18–84) Median disease duration, in years (range) 12 (1–40) Crohn’s disease, n (%) 61 (77)

Age at diagnosisa, n: A1/A2/A3 8/41/12

Locationa, n: L1/L2/L3/L4 11/14/30/6 Behavioura, n: B1/B2/B3 22/24/15 Perineal disease, n 27 Ulcerative colitis, n (%) 18 (23) Extensiona, n: E1/E2/E3 1/4/13 Extra-intestinal manifestations, n (%) 30 (38) Current smoking, n (%) 23 (29) Received treatment before inclusion, n (%)

Thiopurines 57 (72)

Methotrexate 25 (32)

Major abdominal surgery 25 (32)

Anti-TNFb 35 (44)

a

According to the Montreal classification.10 b

Among the 70 patients with IBD diagnosed before the previous cancer, 26 had received infliximab, 3 adalimumab and 6 both anti-TNF agents.

to an active luminal disease. Among the 18 patients with ulcera-tive colitis, anti-TNF therapy was given because of refractoriness to conventional therapy in 15 cases and severe attack in 3. Anti-TNF was started in combination with a conventional immunosup-pressant in 18 cases, associated with thiopurine in 11 (14%) patients, or with methotrexate in 7 (9%) patients.

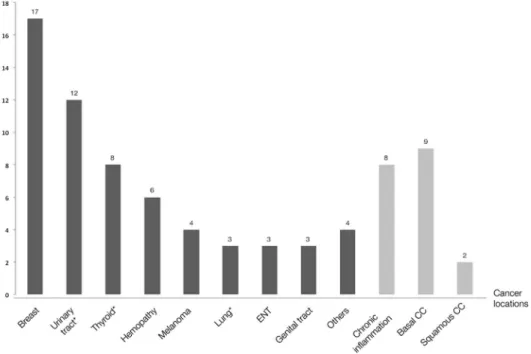

Characteristics of Prior Malignancies

Median age at cancer diagnosis was 45 (18–81) years. Can-cer locations are presented in Figure 2. The most frequent canCan-cer locations were breast (n¼ 17), skin (n ¼ 15, including 9 basal-cell carcinomas, 2 squamous-basal-cell carcinomas and 4 melanomas), cancer of the genitourinary system (n¼ 12, including 3 kidney, 2 bladder, 5 prostate, and 2 testicular cancers), and malignancies that can be attributed to chronic inflammation (n ¼ 8, including 3 small bowel and 2 colorectal adenocarcinomas, 1 anus squamous-cell carcinoma, and 2 cholangiocarcinomas in patients with an associated primary sclerosing cholangitis). At cancer diagnosis, 17 (22%) patients had lymph node involvement and 3 (4%) pa-tients had a metastatic extension. Cancer therapy consisted in surgery in 68 (86%) patients, chemotherapy in 18 (23%), and radiotherapy in 28 (35%).

Median interval between cancer diagnosis and inclusion was 17 (1–65) months (Fig. 1). At inclusion, 77 (97%) patients

were in remission, 1 was receiving chemotherapy for lung cancer, and 1 had a metastatic prostatic cancer controlled with hormone therapy.

Follow-up and Outcomes

With a median follow-up of 21 (1–119) months, 15 (19%) patients developed an incident cancer of which 8 pa-tients had recurrent cancer and 7 papa-tients had a new malig-nancy, including 5 with subsequent basal-cell carcinomas. Details of the 15 patients with incident cancers are provided in the Table 2. In the whole population, survival without inci-dent cancer at 1, 2, and 5 years was 96%, 86%, and 66%, respectively (Fig. 3). The crude incidence rate of incident can-cer was 84.5 (95% CI, 83.1–85.8) per 1000 patient-years in the whole population.

Incident cancer-free survival was not different between patients taking immunosuppressant or not at inclusion (P ¼ 0.366) and in those having an interval between previous cancer and inclusion of less or more than 2 years (P¼ 0.499) (see Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/IBD/B220). After exclusion of previous and incident NMSC, survival without incident cancer at 1, 2, and 5 years was 98%, 90%, and 67%, respectively (see Fig. 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http:// links.lww.com/IBD/B221).

FIGURE 2. Cancer locations among the 79 recruited patients. Kaplan–Meier curve of survival without incident cancer during follow-up after exclusion of patients with previous and incident NMSCs (n¼ 66). Details for each cancer location are as follows: breast ¼ 17; skin ¼ 15 (9 basal-cell and 2 squamous-cell carcinomas and 4 melanomas); genitourinary system¼ 12 (3 cancers of kidney, 2 of bladder, 2 of testicles and 5 of prostate); IBD-associated chronic inflammation ¼ 8 (3 small bowel and 2 colorectal adenocarcinomas, 1 anus squamous-cell carcinoma and 2 chol-angiocarcinomas in patients with an associated primary sclerosing cholangitis); thyroid¼ 8; hematology ¼ 6 (3 Hodgkin’s lymphomas, 1 cuta-neous T-cell lymphoma, 1 T-cell lymphoma with high-grade anaplasia and 1 chronic myeloid leukemia), lung¼ 3; tongue ¼ 3; genital tract ¼ 3 (2 endometrial and 1 cervical cancers); miscellaneous¼ 4 (2 neuroendocrine tumors, 1 adenoid cystic carcinoma, and 1 anal squamous-cell car-cinoma in a patient with no previous anoperineal Crohn’s disease location). *Including one case of metastatic cancer at inclusion. Basal CC, basal-cell carcinoma; squamous CC, squamous-basal-cell carcinoma.

The crude incidence rates of cancer were 97.7 per 1000 patient-years when the interval from the incident cancer to inclusion was less than 2 years and 66.4 per 1000 patient-years when it was more than 2 years. Concerning immunosuppressant exposure at inclusion, crude incidence rates of cancer were 74.8 per 1000 patient-years in patients receiving these agents, and 87.3 per 1000 patient-years in those not exposed. After excluding past

and incident NMSC, crude incidence rate of cancer was 67.1 per 1000 patient-years (see Fig. 3, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/IBD/B222).

After exclusion of incident basal-cell carcinomas, median duration from previous cancer to incident cancer diagnosis and from inclusion to incident cancer diagnosis were 63 (12–130) and 32 (6–83) months, respectively. All patients with incident basal-cell carcinomas had previously received thiopurines, within a median exposure duration of 119 (2–254) months. After excluding NMSC, there was a significant difference in the age at cancer diagnosis between patients with an incident cancer and those with no incident cancer, 56 (33–78) years versus 42 (18– 74) years (P¼ 0.017).

Likewise, there was a significant difference in the follow-up duration between patients with an incident cancer and those with no incident cancer, 33 (6–84) months versus 20 (1–101) months (P¼ 0.036). After excluding NMSC, there were no factors asso-ciated with incident cancer in univariate analysis (Table 3).

Among the 15 patients with incident cancers, 5 patients died during follow-up (Table 2) of which 4 deaths were related to cancer evolution (fatal hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in a 35-year-old woman with a history of cutaneous T-cell lym-phoma, metastatic recurrence of a small bowel adenocarcinoma in a 41-year-old man with Crohn’s disease, local recurrence of a perineal squamous-cell carcinoma in a 52-year-old woman with severe anoperineal Crohn’s disease, and locoregional recur-rence of a tongue cancer in a 71-year-old woman), and one death

TABLE 2. Main Characteristics of the 15 Patients Who Developed an Incident Cancer During Follow-up

Sex, Age Cancer: Site, TNMa

Interval Cancer—Inclusion (mo)

Interval Inclusion-Incident

Cancer (mo) Incident Cancer

Status at the End of Follow-up F, 55 Breast, TxN1M0 51 21 Contralateral breast cancer Remission F, 35 Skin T-cell lymphoma 5 12 Hepatosplenic lymphoma Death M, 41 Small bowel, T4N1M0 17 27 Local recurrence T4N2M1 Death

F, 52 Perineal squamous CC 4 54 Local recurrence Death

F, 71 Tongue, T2N0M0 32 36 Locoregional recurrence Death

M, 59 Rectum, T3N1M0 48 74 Liver and lung metastasis Under treatment

M, 76 Lung, T1N0M0 6 6 Brain metastasis Under treatment

M, 85 Prostate 25 52 Bone and liver metastasis Under treatment M, 89 Bladder, T1N0M0 46 83 Local recurrence Death (in postoperative

surgery suites for Crohn’s disease)

M, 66 Prostate 10 23 PSA increase Surveillance

M, 51 Melanoma 6 12 Basal CC Remission

M, 61 Basal CC 0 5 Basal CC Remission

M, 50 Basal CC 11 6 Basal CC Remission

M, 76 Squamous CC 10 12 Basal CC Remission

M, 36 Thyroid cancer, T1N1M0 3 119 Basal CC Remission

a

If TNM available.

basal CC, basal-cell carcinoma; F, female; M, male; squamous CC, squamous-cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3. Kaplan–Meier curve of survival without incident cancer during follow-up.

was due to a course of IBD (septic complications following anal surgery for recurrent anoperineal Crohn’s disease in a 74-year-old man).

During the follow-up period, median duration for anti-TNF treatment was 18 (range¼ 2–87) months. The median number of infliximab infusions was 7 (range ¼ 1–42) among the 53 patients who received this anti-TNF agent and the median number of adalimumab injections was 36 (range ¼ 4–190) among the 26 exposed patients. Concerning associated treatments during the follow-up period, 15 (19%) patients were exposed to thiopurines, 14 (18%) to methotrexate, and 16 (20%) had had major abdominal surgery. At the end of follow-up, 55 (68%) patients were still treated with anti-TNF, including 6 patients with incident cancer (2 patients with prostatic cancer recurrence treated by hormone therapy and 4 with incident basal-cell carcinoma).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is one of thefirst to assess the risk for incident cancer in an IBD population exposed to anti-TNF therapy while having recent history of malignancy. It indicates that in a highly selected cohort of IBD patients recruited in tertiary referential centers who were diagnosed with cancer within 5 years before receiving an anti-TNF agent, survival without incident cancer was 96% and 66% at 1 and 5 years, respectively. Fifteen (19%) patients developed an incident cancer in the total study population, corresponding to a crude incidence rate of 84.5 (95% CI, 83.1–85.8) per 1000 patient-years.

Data on incident cancer risk due to anti-TNF agents in patients with history of cancer are lacking for IBD and few are available so far in rheumatology. The British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register evaluated the risk of recurrent cancer while on anti-TNF therapy in 177 rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients having previous malignancy.15When compared to

a control group exposed to traditional disease-modifying antirheu-matic drugs, a trend of a lower risk for cancer recurrence was observed with anti-TNF agents with an incident risk ratio of 0.58 adjusted for age and sex (95% CI, 0.23–1.48). Crude incidence rate of incident cancer was lower in this RA population (25.3 per 1000 patient-years) as compared with those of our study. How-ever, the median interval between cancer diagnosis and anti-TNF use was longer, beyond 10 years, in this registry when compared to the present IBD cohort. In the German biologics register con-ducted for RA, the crude recurrence rate of cancer for patients exposed to anti-TNF with previous cancer was 45.5 per 1000 patients-years.16More recently, in a case–control Swedish study,

the risk of breast cancer recurrence was similar regardless of the anti-TNF exposure among patients with RA having previous breast cancer.17However, it must be taken into account that there

are striking differences between RA and IBD populations—rheu-matologic patients are older and the conventional immunosup-pressant usually associated with anti-TNF is methotrexate instead of thiopurines. Therefore, extrapolation of these results in an IBD population seems hazardous. It has been more recently observed in a retrospective study that IBD patients with history of cancer do not have an increased risk of incident cancer when exposed to an anti-TNF agent as compared to those who did not receive any immunosuppressant therapy.18

As observed in registries of post-transplant cancers, most of the recurrences occur within the first years.19 A short interval

between diagnosis of neoplasia and anti-TNF therapy for IBD is suggested to have an important role on the recurrence risk. Fol-lowing data collection from patients with organ transplants and despite the lack of any evidence, current recommendations con-traindicate anti-TNF use in IBD patients with a cancer diagnosis within the last 5 years.4This also explains why this study, which

was restricted to a population with the highest risk of recurrence, identified a more elevated crude incidence risk than that in the RA studies.

The impact of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-alpha on malignancy has been extensively studied. This cytokine may exert 2 opposite processes on tumor proliferation. On the one hand, TNF-alpha exerts an antitumor effect initiating cellular apoptosis. Accordingly, this effect has prompted the theoretical concern that inhibiting TNF-alpha may cause either recurrence or rapid tumour progression in patients with cancer. Conversely, TNF-alpha has also been shown to facilitate survival and proliferation of neoplastic cells through the nuclear factor

k

B signalling path-way.20Thus, considering that TNF-alpha plays a key role in thedevelopment of cachexia associated with cancer, several phase II studies have been conducted combining chemotherapy with anti-TNF agents compared to chemotherapy with placebo in patients

TABLE 3. Results of Univariate Analysis for Predictors

of Occurrence of Incident Cancer (After Excluding

NMSC)

Variable Relative Risk 95% CI P

Male sex 0.81 0.20–3.29 0.763

Age at diagnosis (yr) 1.02 0.99–1.05 0.205 IBD subtype

Crohn’s disease Reference

Ulcerative colitis 3.86 0.65–22.84 0.136 Extra-intestinal manifestations 1.30 0.34–4.92 0.694 Prior bowel resection 2.18 0.43–11.0 0.344 Immunosupressant at inclusion 0.62 0.16–2.43 0.494 Anti-TNF exposure before

prior cancer

0.82 0.21–3.2 0.776 Age at cancer diagnosis (yr) 1.03 0.99–1.07 0.145 Surgery for the prior cancer 0.49 0.1–2.46 0.39 Chemotherapy for the prior cancer 1.84 0.44–7.74 0.403 Radiotherapy for the prior cancer 1.69 0.43–6.6 0.45 Interval between cancer diagnosis

and inclusion (mo)

0.99 0.97–1.03 0.953

CI, confidence interval; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

with current malignancies. No evidence of disease acceleration or increased mortality has been identified with infliximab in patients with refractory renal cell carcinoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and non–small-cell lung cancer.21–23

Furthermore, 2 confounding factors may have an impact on incident cancer in IBD having past malignancy and exposure to anti-TNF agents. First, in the general non-IBD population, patients with previous cancer have an increased risk of new cancer.24It can be related to deleterious specific exposure, genetic

susceptibility, and/or cancer therapy. This feature has also been recently observed in the French IBD CESAME cohort, with a 2-fold increased risk of incident cancer per se in patients with previous malignancy when compared to others.5 Second,

expo-sure to thiopurines (72% in the present cohort), which are asso-ciated with an increased risk of lymphoma and of NMSCs may also influence the risk of incident cancer.25,26This hypothesis has

not been confirmed in the CESAME cohort.5 Nevertheless, to

estimate the real impact of anti-TNF on incident cancer, an anal-ysis excluding NMSC has been performed in the present cohort. The crude incidence rate of incident cancer was lower than that in the whole cohort.

Due to its design, we acknowledge that this study has the following limitations: a partially retrospective recruitment, a heterogeneous study population (including various types and stages of malignancies), and that patients were not only exposed to anti-TNF agents but also to immunomodulator and anticancer therapies, and the follow-up duration was limited. These features may influence the risk of incident cancer. No control group was available because of the great variety of malignancies included. Conversely, the present cohort included patients with a poor IBD course leading their physicians to start an anti-TNF agent despite a recent history of cancer. This population clearly illustrates that managing IBD patients with a past or current malignancy has become more frequent as trends in therapy are moving to an increasingly earlier and longer use of immunomodulators. However, physicians are reluctant to give these agents to patients with past malignancies. This has been observed in a study from a tertiary referential center that identified 80 patients with extra-intestinal cancer in their cohort. When compared to control subjects, patients with previous cancer had a comparable disease activity, but were less exposed to any immunomodulator and underwent surgery more frequently.7

In the present population of IBD patients who have been exposed to anti-TNF while having recent malignancy, crude incidence rate was 84.4 per 1000 patient-years, which is higher than in RA studies. Thus, making the decision to use anti-TNF in this specific population requires balancing the risks between reactivating dormant metastases and an uncontrolled IBD course. With pending additional data, a case-by-case decision should be taken with the oncologist and the patient, taking into account natural history of cancer according to location, histological type, and time since cancer diagnosis and IBD prognosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

F. Poullenot has received lecture fees from Abbvie and MSD, P. Seksik has received consulting and lecture fees from Biocodex, Abbvie and MSD, L. Beaugerie has received consul-ting fees from Abbvie, lecture fees from Abbvie, Ferring, and MSD, research grants from Abbvie, Biocodex and Ferring, and travel support from Abbvie and Ferring, A. Amiot has received consulting fee from Abbvie and Biocodex and lectures fee and travel accommodation from Abbvie, Biocodex, and MSD, A. Bourreille has received consulting and lecture fees from Abbvie, Covidien, Ferring, MSD, and Takeda, D. Laharie has received consulting and lecture fees from AbbVie and MSD. The other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

1. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Ferrante M, Magro F, et al. Results from the 2nd

Scientific Workshop of the ECCO. I: impact of mucosal healing on

the course of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:

477–483.

2. Ramadas AV, Gunesh S, Thomas GAO, et al. Natural history of Crohn’s

disease in a population-based cohort from Cardiff (1986-2003): a study of changes in medical treatment and surgical resection rates. Gut. 2010;59:

1200–1206.

3. Kaplan GG, Seow CH, Ghosh S, et al. Decreasing colectomy rates for ulcerative colitis: a population-based time trend study. Am J

Gastroenter-ol. 2012;107:1879–1887.

4. Dignass A, Assche GV, Lindsay JO, et al. The second European

evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease:

current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:28–62.

5. Beaugerie L, Carrat F, Colombel JF, et al. Risk of new or recurrent cancer under immunosuppressive therapy in patients with IBD and previous cancer. Gut. 2014;63:1416–1423.

6. Guerra I, Algaba A, Quintanilla E, et al. Management and course of inflammatory bowel disease patients with associated Cancer.

Gastroenter-ol. 2014;146. Issue 5 -54–S-55.

7. Rajca S, Seksik P, Bourrier A, et al. Impact of the diagnosis and treatment

of cancer on the course of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis.

2014;8:819–824.

8. Gómez-García M, Cabello-Tapia MJ, Sánchez-Capilla AD, et al.

Thio-purines related malignancies in inflammatory bowel disease: local

expe-rience in Granada. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4877–4886.

9. Stange EF, Travis SPL, Vermeire S, et al. European evidence based

consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease:

defini-tions and diagnosis. Gut. 2006;55(suppl 1):i1–15.

10. Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, et al. The Montreal classification

of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and

implica-tions. Gut. 2006;55:749–753.

11. Telfer NR, Colver GB, Morton CA, et al. Guidelines for the management

of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:35–48.

12. Motley R, Kersey P, Lawrence C, et al. Multiprofessional guidelines for the management of the patient with primary cutaneous squamous cell

carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:18–25.

13. Anon. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing R. Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. 2014. Available at: http://www.R-project.org/.

14. Anon. Therneau T. A package for survival analysis in S. R Package

Version 2.37–7. 2014. Available at:

http://CRAN.R-project.org/packag-e¼survival..

15. Dixon WG, Watson KD, Lunt M, et al. Influence of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy on cancer incidence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have had a prior malignancy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62: 755–763.

16. Strangfeld A, Hierse F, Rau R, et al. Risk of incident or recurrent malignan-cies among patients with rheumatoid arthritis exposed to biologic therapy in the German biologics register RABBIT. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R5.

17. Raaschou P, Frisell T, Askling J, et al. TNF inhibitor therapy and risk of breast cancer recurrence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014.

18. Axelrad J, Bernheim O, Colombel J-F, et al. Risk of new or recurrent

Cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and previous Cancer

exposed to immunosuppressive and anti-TNF agents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015.

19. Penn I. The effect of immunosuppression on pre-existing cancers.

Trans-plantation. 1993;55:742–747.

20. Bernheim O, Colombel JF, Ullman TA, et al. The management of

immu-nosuppression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and cancer.

Gut. 2013;62:1523–1528.

21. Harrison ML, Obermueller E, Maisey NR, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha as a new target for renal cell carcinoma: two sequential phase II trials of infliximab at standard and high dose. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:

4542–4549.

22. Wiedenmann B, Malfertheiner P, Friess H, et al. A multicenter, phase II

study of infliximab plus gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer cachexia.

J Support Oncol. 2008;6:18–25.

23. Jatoi A, Ritter HL, Dueck A, et al. A placebo-controlled, double-blind trial

of infliximab for cancer-associated weight loss in elderly and/or poor

performance non-small cell lung cancer patients (N01C9). Lung Cancer.

2010;68:234–239.

24. Curtis RE, Freedman M, Ron E, et al. New Malignancies Among Cancer Survivors: SEER Cancer Registries, 1993-2000. Bethesda, MD: National Canecr Institute; 2006.

25. Beaugerie L, Brousse N, Bouvier AM, et al. Lymphoproliferative

disor-ders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease:

a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1617–1625.

26. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Khosrotehrani K, Carrat F, et al. Increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients who receive thiopurines for

inflam-matory bowel disease. Gastrenterology. 2011;141:1621–1628.e1–5.