Daylighting Pathways to Good Jobs in California’s Solar Industry By

Neha Bazaj

BA in Economics & International Area Studies University of California, Los Angeles

Los Angeles, California (2010)

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master in City Planning at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May 2020

© 2020 Neha Bazaj. All Rights Reserved

The author here by grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis

document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created.

Author______________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 18, 2020 Certified by __________________________________________________________________ Karilyn Crockett Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by__________________________________________________________________ Ceasar McDowell Professor of the Practice Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Daylighting Pathways to Good Jobs in California’s Solar Industry By

Neha Bazaj

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 18, 2020 in Partial Fulfillment of the

Requirements for the Degree of Master in City Planning

ABSTRACT

This paper identifies the opportunities for, and challenges to, creating good quality jobs for

socioeconomically disadvantaged workers through mid-size solar photovoltaic projects in California. Recent policy proposals in the United States suggest that clean energy investments can address both climate change and economic inequality, but existing research calls those claims into question. This paper elaborates on the history of union organizing, project labor agreements and prevailing wage law in the solar photovoltaic industry in California, providing some insight into the

opportunities for using these tools to shape job quality in the mid-size solar photovoltaic sector. In combination with key informant interviews, this will enable us to address the question: under what conditions might mid-size solar photovoltaic projects enable good jobs? My analysis suggests that union organizing, project labor agreements and prevailing wage laws are likely to play a smaller role in mid-size projects than they have in utility-scale projects, and thus additional tools are necessary to ensure that mid-size solar photovoltaic projects create good quality jobs for those that need them the most. Policymakers should consider how to attach workforce investment requirements and labor standards to any regulatory incentives for mid-size projects.

Thesis Supervisor: Karilyn Crockett

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements ... 5

Introduction ... 6

Section 1: Theory & Literature ... 12

Job Quality ... 12

Are Solar PV Jobs Good Jobs? ... 16

Conclusion ... 28

Section 2: Research Statement, Methods & Data ... 29

Section 3: History & Context ... 32

Project Labor Agreements ... 32

Prevailing Wage ... 34

Union Organizing ... 36

Labor & Environmental Justice ... 38

Pricing / Cost ... 39

Conclusion ... 40

Section 4: Interview Analysis & Findings ... 41

Conclusion ... 48

Conclusion & Recommendations ... 50

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the many people who helped bring this project across the finish line. From the beginning, Mariana’s sage advice that, “once your research question is so small that it makes you sad, then you have an appropriate research question” kept the thesis process constrained, which was particularly valuable in the context of a global pandemic. It left time for phone calls with loved ones, virtual birthday parties and baby showers, and TikTok dances.

My former colleagues from the California Public Utilities Commission (Whitney, Patrick and Scott) helped me connect my academic question to the real world, and Scott was particularly helpful in connecting me to many of my interviewees. Many thanks, of course, to my interviewees for sharing their experiences, thoughts and opinions with me, and for further grounding my research in reality. I could not have made it through the writing process without the support of my DUSP wives, Jenny and Julia C., the many hours of tomato-time with Julia F. and Carolyn, or the helpful reminders and jokes from all the other MCP2s working through the same process. Big thanks to my housemates Patricia, Cora and Sarah for making our home a peaceful place to work, and for celebrating first drafts, defenses and other milestones with me along the way.

Last, but not least, I am grateful for Karilyn and David for agreeing to guide me through this

process. Karilyn, check-ins with you kept me from spinning out, and your confidence in me gave me the boost I needed to make forward progress. David, debating with you has helped me to better understand and articulate my views, and I’m still waiting for the day you convince me that I’m wrong.

I appreciate all of you more than is possible to express in words. I can’t wait for the day I can thank you all in-person.

Introduction

Climate Change & Economic Inequality

We are facing twin crises of increasing economic inequality and a rapidly changing climate, both of which present particularly severe consequences for socioeconomically marginalized populations. Proposals for a clean energy transition purport to offer a solution to both of these challenges – we can slow or reverse climate change and create jobs to address economic inequality. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and her colleagues in the United States House of

Representative specifically call on “the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal… to create millions of good, high-wage jobs and ensure prosperity and economic security for all people of the United States (Recognizing the Duty of the Federal Government to Create a Green New Deal, 2019).”

While numerous studies affirm that clean energy investments will create new jobs (Wei, Patadia, & Kammen, 2010), studies of clean energy job quality (Kane, 2019; Jones & Zabin, 2015) demonstrate that clean energy jobs are of varying quality, particularly with respect to wages. Thus, while clean energy investments may lead to job growth, further research is needed to determine which clean energy investments have the potential to produce high-quality job and for whom. This research is necessary to more accurately assess and actualize the potential for a clean energy

transition to both address climate change and ensure economic security for all. In this paper, I ask under what conditions might mid-size solar photovoltaic projects in California enable good jobs?

The Clean Energy Transition & Economic Inequality in California

The term “clean energy investment” can be used to describe a wide variety of investments including utility-scale solar and wind farms, solar panel, wind turbine and battery manufacturing, rooftop solar installations, building energy efficiency and weatherization upgrades, and nuclear power plants, amongst others. For the purposes of this paper, I am interested in clean energy jobs related to a clean energy transition. While investments such as building energy efficiency and

weatherization upgrades are certainly useful tools for reducing the amount of energy needed, those activities can and should be undertaken regardless of the fuel source of electricity and will not be considered in this thesis. Instead, I choose to focus exclusively on a technology related to fuel-switching away from fossil fuels – solar photovoltaics (solar PV). Solar PV is one of the most

advanced renewable energy technologies in the market, and in recent years has achieved price parity with fossil fuels such as natural gas (Neff, 2019). Thus, solar PV is likely to be a key technology in any clean energy transition, and therefore job quality in the solar PV industry is an important determinant for the potential of a clean energy transition to also address economic inequality.

I focus my research on California, given the state’s leadership in the clean energy transition. Under the state’s Renewables Portfolio Standard (RPS), all electric utilities currently source at least 25% of their electricity from renewable sources and are mandated to increase that to 60% by 2030 and to 100% by 2045 (RPS, n.d.). Net Energy Metering (NEM) programs allow households, businesses and institutions to install renewable generation on their properties to cover their on-site electric use, and to then sell any excess to their utility company. Programs such as Virtual Net Energy Metering (VNEM) and community shared solar increasingly allow non-single-family homeowners to benefit from the same bill savings offered by NEM. These latter programs may drive growth in the mid-size solar PV sector, making this a crucial moment to establish the rules governing job quality in this sector.

Unfortunately, alongside those ambitious clean energy goals, California also ranks amongst the top five states with the worst income inequality in the United States, and that gap is growing (Chappell, 2019). Drawing on data from the 2018 American Community Survey, the California Budget & Policy Center estimates that the average household income of the top 5% is $506,421 while that of the lowest 20% is just $15,562. And although the “official” poverty rate is declining (12.8% in 2018 down from a high of 17.0% in 2013), the “supplemental” poverty rate, which takes into account the high cost of housing in the state, instead puts the poverty rate at 18.1% (Kimberlin & Hutchful, 2019). Furthermore, as Figure 1 illustrates, those living below the poverty line are unevenly distributed across the state, with the highest rates of poverty largely concentrated in the Central Valley. Analysis by the Public Policy Institute of California also shows that African America and Latino families are disproportionately represented at the lower end of the income spectrum (Bohn & Thorman, 2020).

Figure 1: Percentage of People Living in Poverty in 2018 Based on the Official Poverty Measure

(Kimberlin & Hutchful, 2019)

Notably, these numbers reflect the pre-COVID-19 world. COVID-19 effectively shut down the United States economy for more than two months, resulting in the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression. The crisis has disproportionately affected workers in low-wage

industries such as dining and small businesses, and it is unclear how many of those jobs and businesses will come back. Even before the utter devastation wracked by COVID-19 on socioeconomically vulnerable populations, recent threats to public safety net programs such as recently enacted and proposed changes to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (Capps, 2019) and increasing premiums for Covered California health plans (Covered California, 2019) had already threatened to exacerbate the ability of low- and middle-income individuals and families to meet their basic needs. To the extent that the economic recovery will include clean energy

investments, it is important to understand how to leverage that investment to create good quality jobs that can help create a post-COVID-19 world based in a vision of equity.

The Solar Photovoltaic Industry in California

The University of California, Berkeley’s Center for Labor Research and Education has published studies examining the quality, diversity and accessibility of utility-scale and rooftop solar PV jobs. Their studies of the utility-scale and rooftop sectors provide insight into the industry structures and regulatory incentives that may also govern job creation in the mid-size sector.

They define utility-scale projects as those larger than 20 megawatts (MW) that sell their energy directly to utilities at wholesale rates, and rooftop projects as those smaller than 1 MW that use energy on-site and then sell any excess energy to the utility at the retail rate. The RPS program is the main driver of utility-scale projects, while NEM programs are the primary driver of rooftop projects. Their research indicates that utility-scale projects tend to produce high-quality jobs with average wages of $78,000 annually, health and pension benefits and access to training, while rooftop jobs tend to be of lower quality, with lower wages, fewer benefits and fewer opportunities for advancement (Philips, 2014; Jones & Zabin, 2015).

In recent years there has been growth in projects that don’t neatly fit into these two

categories. For example, in the course of my research I came across a 16.4 MW rooftop project and a 10.5 ground-mount project that both sell the electricity generated to a local utility. Additionally, within the rooftop market, there is a distinction between residential and commercial projects, which operate under different incentives and financial constraints. The Labor Center’s colleagues up the hill at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab define utility-scale as ground-mounted projects larger than 5 MW and anything else as distributed generation,1 but with separate buckets for residential, small non-residential and large non-residential (Barbose & Darghouth, 2019; Bolinger et al., 2019). One of the developers interviewed for this paper notes that “it almost seems like what we've been seeing is that developers are getting more into rooftop space, while, folks like us who are, we're developers, but have mainly been focused on rooftops are getting more into ground-mount space. So it's almost like the two worlds are starting to meld into one industry.”

Thus, while there is consensus that an installation on a single family home is a rooftop installation, and a 100 MW ground-mounted project in the desert is a utility-scale project, there is far less definition around projects in the middle space. While the industry structures and regulatory incentives surrounding utility-scale and rooftop projects have largely already defined those job markets, mid-size projects operate under a much more heterogeneous set of industry structures,

regulatory incentives and regulatory requirements. This leaves an open question -- under what conditions might mid-size solar PV projects in California enable good jobs?

This is a particularly salient question given the numerous existing and forthcoming programs and policies that have the potential to spur the growth of mid-size projects:

• Recent changes to the NEM rules allow for on-site systems larger than 1 MW (Net Energy Metering, n.d.)

• Feed-in Tariff programs have created a small market for ground-mounted systems 1 MW or smaller that sell the electricity generated directly to the utility (MCE Schedule FIT, 2020)

• Under VNEM, owners of multi-tenant buildings can install solar and allocate the electricity generated across tenants and common areas (Virtual Net Metering, n.d.) • The Solar on Multifamily Affordable Housing (SOMAH) program offers incentives for

installing solar on low-income residential housing, saving tenants money on their utility bills (Implementation of AB 693, n.d.)

• In community shared solar programs, such as California’s Green Tariff Shared

Renewables Program, multiple customers subscribe to a share of a solar PV project and in turn receive a bill credit for their share of the electricity produced by the solar PV system (Green Tariff/Shared Renewables Program (GTSR), n.d.)

• Sacramento Municipal Utility District’s recently approved Neighborhood SolarShares Program offers an alternative way for residential developers to meet the state mandate to install solar on all new residential construction by instead allowing them to pay an in-lieu fee to fund a shared project of 20 MW or less (SMUD’s Neighborhood SolarShares Program Approved for New Homes, 2020).

In addition, recent wildfires in California have brought new urgency to conversations about the role of distributed generation in ensuring electric reliability in a changing climate (Balaraman, 2020). These fires have been sparked by power lines and fueled by high winds, dry conditions and years of drought (most notably, the Camp Fire, which decimated the town of Paradise and killed 89 people), and have resulted in a new utility policy of shutting down power lines in anticipation of high-fire risk weather conditions (De-Energization (PSPS), n.d.; Eavis & Penn, 2019). Distributed generation projects, such as mid-size solar PV projects, can be strategically located and paired with energy storage to ensure continued supply for key locations or customers. Assembly Bill (AB) 3021

(Ting) is under consideration in the California Legislature and would provide $900 million for batteries at schools (School Facilities: Energy Resilient Schools: Grant Program., 2020). There are also three potential bond measures on the November 2020 ballot, which would raise billions of dollars for resiliency investments across the state (Cart, 2020).

The Plan of This Paper

Section 1 opens with a brief overview of the theory on job quality, before moving into a more detailed explanation of the aspects of job quality that I will focus on: adequate wages, non-wage compensation, opportunities for advancement, workplace safety and accessibility. Based on existing literature, I then assess the quality of jobs created by utility-scale and rooftop solar PV projects.

Section 2 describes the research question in detail and outlines the methods and data used to address the research question.

Section 3 provides some of the history and context surrounding the solar PV industry in California. This includes an overview of project labor agreements, prevailing wage laws, union organizing in the solar PV industry, points of tension between labor and environmental justice advocates, and the pricing/cost of solar PV projects.

Section 4 offers an analysis of the nine interviews conducted with five categories of

informants: one utility, unions, developers, engineering-procurement-construction-firms/contractor-installers and one workforce development organization. It attempts to answer the question under what conditions might mid-size solar PV projects enable good jobs? Spoiler: it depends!

Finally, the Conclusion offers some recommendations for how California can leverage its clean energy transition to create good quality jobs for those who need them the most, and poses some broader questions regarding clean energy jobs outside of California, our standards for middle-income wages and the future of the labor movement.

Section 1: Theory & Literature

Job Quality

There a number of varying definitions of what constitutes a “good” or “decent” job. The International Labour Organization’s definition includes “employment opportunities, adequate earnings and productive work, decent working time, combining work, family and personal life, work that should be abolished, stability and security of work, equal opportunity and treatment in

employment, safe work environment, social security, and social dialogue (“Measuring Job Quality,” 2020).” Osterman (2013) also highlights diversity in the substance of work (including skill levels, autonomy, and intensity or stress); the ability and extent of control over one’s work and the extent of surveillance; stress and intensification of work; and employment terms and conditions. Adamson and Roper (2019) note that different disciplines tend to focus on different aspects of job quality; economists tend to narrowly focus on wages, psychologists are more concerned with individual’s own perceptions and sociologists take a more holistic view that considers both economic and non-economic factors.

Although it would be neither possible nor prudent to try to create one universal definition of what constitutes good job quality, it is useful to select some parameters of good job quality to at least begin to understand the challenges and opportunities for creating good quality jobs in the mid-size solar PV sector. While a primary motivation behind this thesis is economic inequality and ensuring economic security, the uneven racial and spatial distribution of income inequality and the weak nature of the social safety net in the United States demand a more nuanced approach. I define five elements of job quality that I believe are particularly relevant to the issues of economic

inequality and the solar PV industry in California. These are adequate wages, non-wage compensation, opportunities for advancement, workplace safety and accessibility.

Adequate Wages

In order for individuals and families to achieve economic security, they must be paid an adequate wage. However, what constitutes an adequate wage varies substantially. Below I present estimates from two tools that attempt to estimate an adequate wage based on location and on the number of wage earners and dependents in a household. The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) has developed a Family Budget Calculator which estimates the income required for a modest yet adequate standard of living (“Family Budget Calculator,” n.d.). MIT’s own Dr. Amy K. Glasmeier

developed the Living Wage Calculator, which estimates the income required to meet a family’s basic needs while also maintaining self-sufficiency. It does not include amounts for savings or investment, and so may be better defined as a minimum subsistence wage (Living Wage Calculator, n.d.).

Both tools include baseline amounts for housing, food, childcare, transportation, health care, other necessities and taxes. I provide estimates for three different household compositions, all with two children but with varying numbers of adults and working adults. I chose these combinations to highlight that a family-sustaining wage can vary widely depending on household composition. While these tools certainly do not account for all of the factors that may impact a household’s financial need, they nonetheless serve as a useful benchmark against which to evaluate the ability of different jobs to meet a family’s basic needs.

To ground our discussion, I offer income estimates for four geographic regions within California: Kern County, Imperial County, the Los Angeles metro area and the San Francisco metro area. Kern County is located in the San Joaquin Valley, which has both high rates of poverty and a large share of utility-scale solar PV projects. The California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) is also specifically exploring options to bring affordable energy options to residents in disadvantaged communities in the San Joaquin Valley (San Joaquin Valley Affordable Energy Proceeding, n.d.), making this region particularly relevant to goals to promote a clean energy transition that also addresses economic needs. I include Imperial County because it also has high rates of poverty and many utility-scale solar PV projects have also been built in the Imperial Valley. Finally, I include the Los Angeles and San Francisco metro areas to offer benchmarks for higher-cost urban and suburban areas.

Table 1 2 adults (2 income) 2 children 2 adults (1 income) 2 children 1 adult 2 children Location Living Wage Calculator (2019 dollars)

a Family Budget Calculator (2017 dollars)b

Kern County $72,524 $54,988 $66,533

$73,204 n/a $62,597

Imperial County $72,893 $55,357 $66,903

$74,628 n/a $63,465

Los Angeles Metro Areac $85,152 $67,616 $79,162

$92,295 n/a $84,144

San Francisco Metro Aread $94,741 $77,205 $88,750

$125,672 n/a $116,502

a (Living Wage Calculator, n.d.) b (“Family Budget Calculator,” n.d.)

c For the Family Budget Calculator this is consists of Los Angeles County, for the Living Wage Calculator this is the Los

Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim Metropolitan Statistical Area

d For the Family Budget Calculator this is Contra Costa County, for the Living Wage Calculator this is the San

Francisco-Oakland-Hayward Metropolitan Statistical Area

The Family Budget Calculator tends to offer slightly higher estimates than the Living Wage Calculator, but the estimates for Kern and Imperial Counties are quite close. The estimates for the Los Angeles and San Francisco metro areas vary substantially, likely due to the two tools’ difference in underlying geographic definitions for those regions. Going forward, I will refer to the wages provided by the Living Wage Calculator, as it offered estimates for a greater variety of household compositions and its estimates for the Los Angeles and San Francisco metro areas encompass those regions’ entire metropolitan statistical areas.

Non-Wage Compensation

Beyond wages, jobs may offer various forms of non-wage compensation. These may include healthcare (e.g. medical, dental and vision insurance), retirement benefits (pensions or employer-matched contributions to individual savings accounts), paid time off (e.g. sick, vacation, maternity and/or family leave). However, the vital importance of health insurance, savings and paid time off have become all too clear in light of COVID-19, for both individual and public health, bringing their

characterization as “benefits” into question. These benefits are not simply “extra perks,” but rather constitute basic needs as well. A good quality job requires not just adequate wages but health insurance, allowance for contributions to savings and paid time off to care for oneself and one’s family.

Opportunities for Advancement

Many industries offer a variety of jobs, some of low-wage/low-quality, others of high-wage/high-quality. However, a low-wage/low-quality job need not also be a dead-end job. Career ladder programs provide the training to enable workers to move from lower- to higher-quality jobs within an industry, and may even work with an industry to create new rungs on a job ladder (Osterman & Shulman, 2011). Career ladders in the healthcare industry, for example, can offer employees the opportunity to move from jobs as cleaners and orderlies to jobs as certified nursing assistants and ultimately to jobs as registered nurses (Osterman & Shulman, 2011). Thus, when evaluating the potential for the solar industry to create good jobs, it is worthwhile to also consider whether it creates the opportunity to move into good-quality jobs.

Workplace Safety

In 2018, the construction industry had the eighth highest incident rate of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses, at 3 incidents per 100 full-time workers, with 1.2 of those incidents requiring time away from work (2018 Survey of Occupational Injuries & Illnesses, 2019). This is two to three times higher than the incident rates associated with white-collar industries such as professional and technical services, and where incidents rarely require time away from work.

Solar construction comes with a particular sets of risks including falls (for rooftop

installations), electrical injuries, and heat related illness (for projects in hot geographic areas (Green Job Hazards: Solar Energy | Occupational Safety and Health Administration, n.d.). For workers on utility-scale solar projects in the southwest United States, there are additional concerns related to the dangers of inhaling dust containing the fungus Coccidioides, which causes Valley Fever (Sondermeyer Cooksey et al., 2017).

Given the dangers associated with solar PV construction, it is essential for workers to receive proper safety training regarding how to protect themselves, and for worksite managers to ensure that appropriate preventive measures are in place.

Accessibility

Given that certain racial and geographic populations are disproportionately at the lower end of the income inequality spectrum, it is also important to consider whether the jobs being created are accessible to those who need them the most. Differences in geographic locations of projects, and racial and gender disparities in the construction industry may impact who is able to secure work in the solar PV industry.

Are Solar PV Jobs Good Jobs?

UC Berkeley’s Labor Center has published studies examining the quality, diversity and accessibility of utility-scale and rooftop solar PV jobs. Their studies of the utility-scale and rooftop sectors not only provide insight into the quality of jobs created by the two different sectors, but also insight into the different mechanisms that govern job creation in the two sectors. It is useful to understand the job quality in the utility-scale and rooftop sectors, and the mechanisms that have helped to determine that job quality, as this can help us understand the potential pathways for job creation in the mid-size sector.

Utility-Scale Solar PV

Wages and Non-Wage Compensation

Jones et al (2016) estimate the wages and benefits paid to various categories of workers involved in renewable energy construction in Kern, Imperial, Riverside, San Bernardino and San Luis Obispo counties (where most utility-scale renewable energy projects have been constructed) from 2002-2015. Although their estimates include jobs across multiple renewable energy

technologies, utility-scale solar PV (here defined as anything greater than 5 MW) makes up almost half of the MW installed and is associated with more than half of the blue-collar construction job-years over this period. Wages and benefits are shown for a variety of trades in Figure 2.

Figure 2

(Jones et al., 2016, p. 10)

If we assume full-time employment (40 hours a week for 50 weeks a year), annual pre-tax salaries range from a low of $56,480 for a teamster to a high of $105,700 for an electrical utility-lineman. For an electrician-wireman, one of the most common types of workers on utility-scale solar PV projects, their annual salary is estimated at $76,400.

This latter estimate is in-line with Philips (2014) conclusion that utility-scale solar PV

projects in California have produced high-quality construction jobs with an average salary of $78,000 and health and pension benefits. Phillips’ analysis was based on three projects in Riverside and San Luis Obispo counties.

Measured against the living wage estimates for Kern and Imperial counties, which range from $54,988 to $72,893, the wages of $76,400-$78,000 for an electrician-wireman are adequate. These wages may or may not be sufficient for households in the San Francisco and Los Angeles metro areas (living wage estimates from $67,616 to $94,741), depending on household composition.

However, as the majority of utility-scale solar PV projects are not constructed in these metro areas, it may not be a valid to expect wages for these jobs to keep pace with those standards, as it is less likely that workers on these projects live in those area. Both studies note that the jobs also come with health and pension benefits, which Jones et al. (2016) estimate increases total compensation by almost 50%.

Opportunities for Advancement

Through their use of union labor and those unions’ use of an apprenticeship model, utility-scale solar PV projects in California offer opportunities for both skilled and entry-level construction workers, with a clearly defined process for moving up the career ladder.

Apprenticeship programs are quite common in the construction industry, with electricians holding the largest share of active apprentices in 2018 (Apprenticeship Data and Statistics, n.d.). Apprentices complete free classroom training while also working on construction projects where they receive pay and benefits. As they move through their training and required work hours, their compensation increases. Apprenticeship programs take 3-5 years to complete, with electrical apprenticeship programs requiring a minimum of 8,000 hours of on-the-job training and 640 hours of classroom training (Luke et al., 2017).

From 2012-2016, 89% of graduates from California state-certified apprenticeship programs were from union-associated programs, and in California, 16 union locals have been responsible for building the majority of utility-scale solar projects, with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) making up about 60% of work-hours (Luke et al., 2017).

Luke et al (2017) analyze a set of 27 solar projects built in Kern County from 2012-2017. This represents 25% of all solar built during this time period. The electrical workers for these projects all came from IBEW Local 428, and included journeymen, apprentices, un-indentured apprentices (those working through the apprenticeship application process) and panel installers. The project labor agreements (PLAs) for these projects required a ratio of one journeyman to one apprentice to four panel installers. Figure 3 below shows the number of electrical workers by wage and skill level on those 27 projects. Compensation ranges from a low of $13 per hour ($26,000 annually) without benefits for a panel installer to a high of $41.21 ($82,420) with full benefits for a journeyman.

Thus, although not all jobs created by utility-scale solar PV projects in California offer adequate compensation, they do offer a clear pathway and opportunity to advance into a job that does.

Figure 3: Number of Workers by Wage and Skill Level on 27 Solar Projects, 2012-2017

(Luke et al., 2017, p.12)

In addition, under PLAs, project contractors pay into these apprenticeship training programs. In fact, Jones et al. (2016) estimate that from 2010-2014, the training for 16% of graduating electrical apprentices was funded by solar PV project contributions to apprenticeship training programs. Thus, utility-scale projects not only offer opportunities for current apprentices to move up the construction career ladder, but they help to fund the training of the next generation of apprentices.

Safety

Worker participation in apprenticeship programs has positive impacts on worker safety (Duncan & Ormiston, 2019; Waitzman & Philips, 2017). Figure 4 below illustrates the relationship between payment of benefits, apprenticeship training and construction industry fatality rates in 2012 across five states with significant development of renewable energy (Jones et al., 2016). States with higher rates of apprenticeship-graduates and higher levels of benefits had lower construction fatality rates. While even a single fatality is a tragedy, apprenticeship programs appear to somewhat mitigate the inherent dangers of construction work.

Figure 4

(Jones et al., 2016, p. 18)

As mentioned above, most graduates from state-certified apprenticeship programs are from union-associated programs. Most utility-scale projects in California use union workers, and thus workers have received training associated with improved worker safety (Philips, 2014). The use of apprentices and journeymen in utility-scale solar PV projects indicate that worker safety is an important feature of these jobs.

Accessibility

Figure 5 illustrates the location of construction jobs associated with renewable energy projects in California from 2002-2015. Most utility-scale solar PV farms have been built in the San

Joaquin and Imperial Valleys, regions that have some of the most disadvantaged communities as identified by CalEnviroScreen (Luke et al., 2017).2 Disadvantaged communities in the San Joaquin Valley are also the focus of CPUC efforts to improve energy affordability.

Luke et al.’s (2017, p. 13) analysis of 27 projects constructed in Kern County from 2012-2017 demonstrated that “38 percent of all workers (including entry level, apprentice, and journeyman) live in disadvantaged communities [and] 43 percent of entry-level workers (panel installers, un-indentured apprentices and first year apprentices) live in disadvantaged communities.” These results are mapped in Figure 6. Similar matches between project location and workforce residence have been reported in Imperial and Fresno counties (Zabin et al., 2016).

Thus, there are indictors that utility-scale solar PV projects are creating jobs that are accessible to residents in regions of California at severe socioeconomic disadvantage.

(Jones et al., 2016, p. 8)

2 “The California Environmental Protection Agency’s tool, CalEnviroScreen 3.0, ranks census tracts to identify the most

disadvantaged communities in California.It takes into account several factors: pollution and hazardous exposure that can lead to negative health effects; sensitive population indicators that confer increased vulnerability to pollutants, such as incidence of asthma; and socio-economic factors including poverty, unemployment, language barriers, low educational attainment, and housing burden. CalEPA defines as “disadvantaged” those census tracts that fall in the worst-off 25

San Joaquin Valley

Imperial Valley Figure 5: County distribution of all renewable

energy construction jobs, California, 2002-15

Figure 7: Map of Worker Residences with CalEnviroScreen 3.0 Scores for Kern County Solar Projects

(Luke et al., 2017, p. 14)

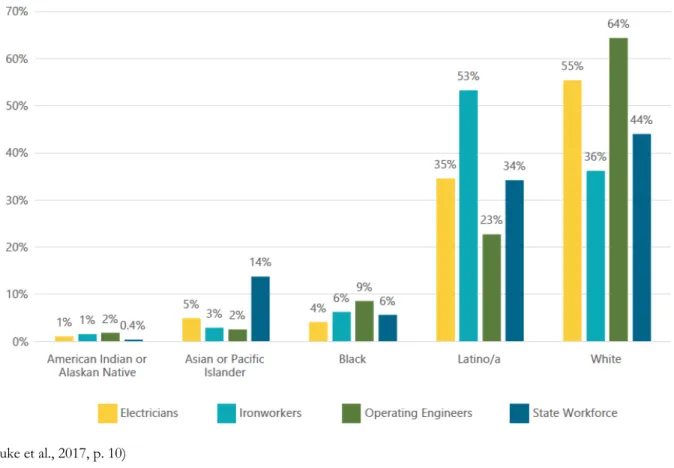

Luke et al. (2017) also analyze the demographics of all apprentices in 16 union locals that built most of the renewable energy projects in California from 2002-2017. Although the apprentices in these unions also work on a variety of projects other than utility-scale solar PV, in order to get a broad range of training, the data are still a relevant indicator for apprentices on utility-scale solar PV projects. The results are shown in Figure 7. Focusing on electricians (the trade making up the

majority of the workforce on utility-scale PV projects), we see that Latinx representation is similar to Latinx representation in the overall state workforce, while black representation is slightly slower. Asian/Pacific Islander and Native American representation are even lower. These statistics offer some cautious optimism that Latinx and black workers, who are overrepresented on the lower end of the income spectrum, have access to the jobs created by utility-scale solar PV.

Figure 8: Apprenticeship Starts by Race/Ethnicity and Trade, 2002-2017

(Luke et al., 2017, p. 10)

Conclusion

The extensive analyses conducted by researchers at UC Berkeley’s Labor Center indicate that utility-scale solar PV projects create good quality jobs. This is largely due to the prominence of union organizing in utility-scale projects that has resulted in the use of union labor and PLAs for these projects. Regulatory incentives, particularly the Renewable Portfolio Standard, have played a strong role in driving demand for utility-scale projects, but have not played a direct role in setting labor standards or establishing job quality.

Journeyman electricians make adequate wages to support a household of four in the lower-cost counties of the San Joaquin and Imperial Valleys, and apprentices may substantially contribute to their household’s economic stability. Importantly, there is a clear pathway for apprentices to move up to journeyman status and thus to eventually make an adequate wage. Regardless of their apprentice/journeyman status, all union workers receive health and pension benefits through their union membership, benefits that increase the value of their total compensation by almost 50%. Participation in apprenticeship training is also associated with better worker safety.

Finally, utility-scale solar PV projects create jobs that are accessible to their surrounding communities, particularly for workers living in the San Joaquin and Imperial Valleys, including those living in disadvantaged communities. The racial demographic data indicate that Latinx and black workers are approximately proportionately represented in these jobs, such that utility-scale solar PV projects are at least not exacerbating racial economic inequities. However, it is likely that more could be done to increase these groups’ representation in these jobs in order to make forward progress and begin to close the gap.

Rooftop Sector

The available data and research on the rooftop solar PV sector is much thinner, but does offer some direct insight on wages, opportunities for advancement and accessibility, and some inferences regarding non-wage compensation, opportunities for advancement, safety and accessibility.

Adequate Wage

The California Occupational Guides report that the median wage for solar PV installers3 in 2019 was $21.52 per hour and $44,765 annually. The Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Employment Statistics survey reports similar values; the median wage in 2018 was $20.52 per hour and $42,680 annually (Solar Photovoltaic Installers, n.d.). However, Jones and Zabin’s (2015) review of job postings find wages as low as $10 per hour.

Using the California Occupational Guides, the wages specific to our reference geographies, alongside the living wage estimates for those geographies, are provided below in Table 2. The data indicate that solar PV installers may earn adequate wages if they are part of a two-income household, but their wages would be insufficient if they are their household’s sole wage-earner.

3 Assemble, install, or maintain solar photovoltaic (PV) systems on roofs or other structures in compliance with site

assessment and schematics. May include measuring, cutting, assembling, and bolting structural framing and solar modules. May perform minor electrical work such as current checks. Excludes solar thermal installers who are included in “Plumbers, Pipefitters, and Steamfitters” (47-2152). Excludes solar PV electricians who are included in “Electricians” (47-2111).

Table 2 Solar PV Installer ½ income 2 adults (2 income) 2 children 2 adults (1 income) 2 children 1 adult 2 children Kern County $41,092 $36,262 $54,988 $66,533 Imperial County $45,467 $36,447 $55,357 $66,903

Los Angeles County $45,253 $42,576 $67,616 $79,162

San Francisco Bay Area $51,457 $47,371 $77,205 $88,750 (Occupation Profile, Solar Photovoltaic Installers, n.d.)

Opportunities for Advancement & Non-Wage Compensation

The difference in career trajectories for solar PV installers as compared to union electricians can be seen in the compensation comparison in Figure 8. While solar PV installer and union

electrician jobs in the San Francisco Bay Area offer similar base wages, a union electrician has the potential to increase their wages by over 300% to $50.40 per hour or $100,800 annually, which would be an adequate wage for a one-income household in the San Francisco Bay Area. Meanwhile, a solar PV installer’s top wage is only $28.05 per hour or $56,100, which would only suffice in a two-income household.

In addition, union electricians receive a union pension, health and other benefits from day one, while the existence and scope of non-wage compensation for solar photovoltaic installers varies contractor by contractor. Thus, jobs in the rooftop sector neither offer opportunities for

Figure 9

(Jones et al., 2016, p. 15)

Safety

Companies in rooftop solar PV sector “compete in the residential construction market where barriers to entry are low, unionized contractors are absent, and contractors who comply with employment laws and building codes must compete with many who skirt these regulation (Jones & Zabin, 2015).” Although there are no statistics on workplace incident rates for solar photovoltaic installers specifically, the incident rate for residential building construction was 2.9 per 100 workers, as compared to 2.5 for nonresidential building construction, where unionization rates are much higher (Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses Data, n.d.). If we look at roofing contractors, the incident rate is even worse, at 4.3 per 100 workers. While not directly applicable to the rooftop solar sector, these statistics re-emphasize the importance of proper training, which we know is available through (largely) union apprentice programs.

Accessibility

A key difference between utility-scale solar PV projects and rooftop solar PV projects is their geographic siting. While the majority of utility-scale solar PV projects and the associated jobs are in the San Joaquin and Imperial Valleys (Luke et al., 2017), rooftop solar PV projects can be located in urban and urban areas throughout the state. The siting of rooftop solar PV projects in population centers means that the associated jobs are more accessible to workers living in or near to urban areas, as opposed to only those workers in more rural parts of the state. Thus, rooftop solar PV projects may offer a more plausible strategy for job creation in urban and suburban areas of the state.

There are also examples of urban workforce development programs working specifically to place workers with barriers to employment in solar photovoltaic installer positions. Zabin et al (2016) describes partnerships between GRID Alternatives, an organization focused on increasing low-income communities’ and communities of color’s access to solar energy and solar jobs, and Homeboy Industries and the East LA Skills center, two organizations that provide training to formerly-incarcerated ex-gang members. However, as of 2015, GRID reported “that out of 1,007 volunteers in the Los Angeles Area, there have been [only] 213 solar industry hires since 2012 (Russak, 2015).” Thus, there is still work to be done to increase access to solar photovoltaic installer jobs by workers with barriers to employment.

Conclusion

The rooftop solar PV sector has been researched much less extensively and rigorously than the utility-scale solar PV sector. However, the available data and research do indicate some broad themes. Wages for solar photovoltaic installers are insufficient to meet the basic needs of a household with only one wage earner, and there is little opportunity for workers to move into higher-wage work. Some workers may receive non-wage compensation such as retirement or health benefits, but this is highly variable from company to company. There is little insight into the safety training offered to solar photovoltaic installers, but the similarities between the rooftop sector and the residential construction sector give cause for concern about whether or not all employers are looking out for the best interests of their employees. Finally, while rooftop solar PV jobs may be found more broadly throughout the state, and thus be accessible to a more geographically diverse workforce, workers with barriers to employment still face difficulty in accessing these jobs.

Conclusion

Existing research on the solar photovoltaic industry in California indicates that utility-scale projects tend to produce high-quality jobs with adequate wages for single-income households, health and pension benefits and access to training, while rooftop jobs tend to be of lower quality, with lower wages, fewer benefits and fewer opportunities for advancement. The research also emphasizes the connection between good quality jobs in the utility-scale sector and union organizing, PLAs and prevailing wage rates. In contrast, union organizing, PLAs and prevailing wage rates are largely absent in the rooftop sector. The utility-scale and rooftop sectors set the stage for understanding the mid-size sector, and the practices and trends in the utility-scale and rooftop sector may influence those of the mid-size sector.

Section 2: Research Statement, Methods & Data

Research Statement

The existing literature on solar PV jobs emphasizes the connection between good quality jobs in the utility-scale sector and union orgnanizing, PLAs and prevailing wage rates. In contrast, unions, PLAs and prevailing wage rates are largely absent in the rooftop sector. Section 3 will offer some more detail on PLAs and prevailing wage law, along with some history and context about the renewable energy market in California. This will help to illuminate why unions, PLAs and prevailing wage rates are prevalent in the utility-scale sector, but not the rooftop sector, and begin to provide some insight into opportunities for shaping job quality in the mid-size solar PV sector. In

combination with key informant interviews, this will enable us to address the question: under what conditions might mid-size solar PV projects enable good jobs?

Methods & Data

I conducted semi-structured interviews with nine people from five types of organizations; a community choice aggregator, union, developers, EPC/contractor-installer and workforce

development.

The lack of clear boundaries for mid-size projects made it difficult to know who to reach out to. I knew that I wasn’t interested in speaking with stakeholders who were focused solely on the residential rooftop sector or focused solely on the utility-scale sector. Instead, I first looked for project developers focused on commercial solar. Solar Power World, an industry media outlet, publishes the Top Solar Contractors list annually. Contrary to its name, the list includes not just companies that provide contracting services, but also companies that provide

Engineering-Procurement-Construction (EPC), development, construction/installation, electrical work and/or rooftop-specific installations (Solar Power World’s Annual Top Solar Contractors List, 2017). I queried for companies in California that self-identified as a developer and listed “Commercial” as their primary market. There were seven.

The California Solar + Storage Association (CALSSA), an industry association, also has a public database of its members. Their membership includes communications/marketing firms, consultants, contractors/installers, designers, distributors/suppliers, engineers, EPCs, financial entities/banks, law firms, manufacturers, nonprofit and educational institutions, project developers and service providers. I queried for members that identified as project developers. There were 38.

I did a web search of the seven developers from the Top Solar Contractors list and the 38 project developers from CALSSA’s membership database to understand what types of customers they served and what types projects they were involved in. I eliminated companies that seemed oriented primarily toward the residential sector or energy storage, or did not seem to have projects in California.

I initially focused on developers as I was interested in speaking with the stakeholder who is responsible for construction workforce hiring decisions. In the course of my research, I came to understand that these decisions are also made by EPCs and contractors (who may subcontract out part of their work), and can also be driven by a project’s customer.

I reached out to a former colleague, who now works at CALSSA, for assistance in obtaining contact information for the project developers on my list. I also asked for his suggestions regarding other companies who work in the commercial sector and might have insight into my research question. Using a combination of his contacts and extensive cold-calling efforts, I was ultimately able to connect with five companies who are developers, EPCs and contractors/installers.

In my initial web search of the 45 developers, I came across the Westmont Solar Energy Project, a 16.4 MW solar system on the roof of a warehouse located within the Port of Los Angeles. This project was notable not only for its size, but for its commitment to a union and veteran

construction workforce. I was interested to understand the circumstances surrounding this outcome, as it seemed to be a perfect example of a project that didn’t fit neatly into either the rooftop or utility-scale sector, and that had created good-quality jobs for a disadvantaged population. I was able to speak with three stakeholders involved in this project: PermaCity Skybridge (the EPC firm), IBEW Local 11 (the IBEW Local that supplied the electricians for the project) and Empower America (a workforce development organization that had connected veterans to the project).

Early on in my research I had also looked into projects commissioned by community choice aggregators (entities that purchase electricity on behalf of customers but that do not own or operate electric transmission or distribution infrastructure), given these entities’ interest in developing local energy projects. Local projects are typically sited in or near to populated areas, which means that they are likely to be smaller than utility-scale projects. At the same time, they are likely to be larger than a project meant to service the electric needs of a single residence or business. I came across MCE Solar One, a 10.5 MW ground-mounted system built on a remediated brownfield in the city of Richmond, CA. The project was built using union labor and had a 50% local hire requirement. On its face, MCE Solar One is a prime example of the potential for mid-size projects to bridge union

and environmental justice interests. I was able to speak with two stakeholders involved in this project: MCE (the community choice aggregator) and IBEW Local 1245 (one of the two IBEW Locals that supplied electricians for the project).

Interviewees

1. Community Choice Aggregator

a. MCE: David Potovsky, Power Supply Contracts Manager 2. Union

a. IBEW Local 11: Robert Corona, Sr. Assistant Business Manager / Director of Organizing

b. IBEW Local 1245 3. Developer

a. TerraVerde: Rick Brown, Chair of the Board b. EnterSolar: Steve Burns, VP, Project Management

4. Engineering-Procurement-Construction Firm / Contractor-Installer a. PermaCity Skybridge: Jeremy Johnson, Principal

b. Baker Home Energy: Keith Randhahn, Director of Engineering, Products and Services

c. Luminalt: Jeanine Cotter, President and CEO 5. Workforce Investment Organization

Section 3: History & Context

The following subsections offer some more detail on PLAs and prevailing wage law, in order to illuminate when a project is likely to use a PLA and/or be subject to prevailing wage laws. I also explore some of the history and controversy behind union organizing efforts in the solar industry, the tensions between labor and environmental justice advocates in the development of different segments of the solar industry, and the different pricing options for solar projects. This will all help to illuminate why unions and PLAs are prevalent in the utility-scale sector, but not the rooftop sector, and begin to provide some insight into opportunities for shaping job quality in the mid-size solar PV sector.

Project Labor Agreements

What are project labor agreements?

A Project Labor Agreements (PLA) is an agreement between a project contractor and a set of construction unions that governs the terms and conditions of employment. While the specific details of a PLA vary, they typically contain two broad provisions: (1) most, if not all, of the workers will be dispatched through the local union hiring halls and (2) there will be no work stoppage for the duration of the project (Waitzman & Philips, 2017). PLAs are similar to the collective bargaining agreements between individual unions and their signatory contractors, but they may be used for projects that require many different types of workers from different unions, where the individual collective bargaining agreements may have conflicting provisions. A collective bargaining agreement is typically valid for a specific set of dates, while a PLA is in effect for the duration of a project, which may not align with a union’s underlying collective bargaining agreements. PLAs may apply to one project or to a set of projects, such as a set of projects funded by the same bond issue

(Waitzman & Philips, 2017).

Unique Provisions of Project Labor Agreements

Other provisions that may be part of a PLA include: wage rates, scheduling, dispute resolution processes, requirements for the contractor to pay into union health benefit and pension plans, journeyman to apprentice ratios, local hire preferences, requirements for unions to ensure an adequate supply of workers, exemptions for employing non-union workers, safety programs, and rules outlining the job responsibilities of different types of workers, amongst others (Garland et al.,

2002; Waitzman & Philips, 2017). These and other provisions are all subject to negotiation during the PLA bargaining process.

Arguments in Favor of Project Labor Agreements

The two typical provisions of PLAs, (1) that most workers be dispatched through the union hiring hall and (2) that there will be no work stoppages, indicate the primary motivations behind PLAs. For unions, PLAs increase the usage of union workers on a project. For a project contractor, PLAs ensure that project completion will not be delayed due to labor disputes. Unions may also be able to negotiate terms that are better than those in their collective bargaining agreements (Garland et al., 2002). Project contractors may also benefit from alignment of work schedules across different types of workers which may improve productivity and efficiency, and they are guaranteed a skilled workforce as the majority of union workers go through rigorous apprenticeship programs (Dunlop, 2002; Waitzman & Philips, 2017).

Utility-scale solar PV projects are good candidates for PLAs. These projects require hundreds of workers across a variety of trades, and so project contractors may benefit from PLA provisions such as schedule coordination, a guaranteed supply of skilled workers and, of course, no work stoppages. For unions, a PLA can guarantee hundreds of jobs for their members and can garner payments into benefit plans and apprenticeship training programs.

Arguments Against Project Labor Agreements

Of course PLAs may not be appropriate for all construction projects. Dunlop notes that “the size, duration, scope, isolation, craft and contractor compositions of the project, the

management structure for the project, and the problems likely to be confronted may not warrant a separate project agreement, distinctive from the separate local or area craft agreements (2002, p. 19).” In particular, the smaller size, shorter duration and more limited craft and contractor compositions of rooftop and mid-size projects may not warrant the use of a PLA.

In addition, open- or merit-shop (non-union) contractors tend to oppose PLAs because they believe the requirement to hire through the union hall puts them at a disadvantage to union shops. While many PLAs will include an exemption for a few of a contractor’s “key” employees, the remainder must be hired through the union. In addition, PLAs may require all project contractors to pay into union health benefit and pension plans, which their “key” employees may not benefit from,

and may constitute double-payment if the contractor is already paying into separate health and retirement benefits programs (Garland et al., 2002; Waitzman & Philips, 2017).

Of particular relevance to our discussion, given the importance of accessibility to good quality jobs by those most impacted by economic inequality, are that women and minority

contractors also often object to PLAs (Garland et al., 2002). These contractors are often non-union and smaller, placing them at them at a disadvantage in bidding on large contracts. However, Lund and Oswald (2001) counter that many PLAs include specific provisions to promote the inclusion of women and minority contractors.

Interestingly, union contractors are also often opposed to PLAs because they may

undermine the terms previously negotiated in their collective bargaining agreement with the union (Garland et al., 2002).

Prevailing Wage

What is the Law?

The Davis-Bacon Act of 1931 applies to federally funded projects over $2000 and requires that “contractors and subcontractors must pay their laborers and mechanics employed under the contract no less than the locally prevailing wages and fringe benefits for corresponding work on similar projects in the area (Davis-Bacon and Related Acts | U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.).” California has additional prevailing wage requirements that apply to state public works projects over $1000 (Public Works Frequently Asked Questions, n.d.).” Prevailing wage laws are intended to ensure that low-bids on public works projects are not based on low pay for workers (Mahalia, 2008).

The Relationship Between Prevailing Wage and Union Wage

Prevailing wage rates are determined through occupation-specific surveys of local wages and collective bargaining agreements. In non-right-to-work states such as California, the collectively bargained union wage and benefits tends to be the prevailing wage (Philips, 2014). Thus, utility-scale projects that use union labor (or any project that uses union labor), pay prevailing wage because the union wage and the prevailing wage are the same.

In our reference geographies, the wages (exclusive of benefits) for apprentice and

journeyman electricians range from a low of $36,000 annually for an apprentice in Imperial County just starting out, to a high of $110,520 annually for a journeyman in Contra Costa County. In all cases a journeyman electrician earns an adequate wage for single income households, and

apprentices, except perhaps those just starting out, are able to substantially contribute to in a two-income household. Thus, prevailing wage laws are one method for ensuring that solar PV projects pay adequate wages.

Table 3 Apprenticea Journeymanb ½ income 2 adults (2 income) 2 children 2 adults (1 income) 2 children 1 adult 2 children Kern County $39,520 - $79,020 $87,800 $36,262 $54,988 $66,533 Imperial County $36,000 - $73,800 $90,000 $36,447 $55,357 $66,903 Los Angeles County $38,760 - $82,360 $97,000 $42,576 $67,616 $79,162 San Francisco Bay Area

(Contra Costa County) $44,200 - 99,460 $110,520 $47,371 $77,205 $88,750

a (State of California Department of Industrial Relations, n.d.-a) b (State of California Department of Industrial Relations, n.d.-b)

Pros / Cons of Prevailing Wage Laws

In a recent review of the existing research, Duncan and Ormiston (2019) examine common areas of contention regarding the effects of prevailing wage laws; construction costs, apprenticeship training, workplace safety and the racial composition of the labor force. Opponents claim that prevailing wage laws increase overall construction costs and discriminate against minority contractors.

Duncan and Ormiston (2019) rebuff these claims, finding that the research “generally indicates that prevailing wage laws do not affect construction costs… and do not have a racially discriminatory impact.” One common explanation for the cost result is that the increased labor costs are offset by the increased productivity of skilled workers and an increased use of capital. However, this hypothesis has not been directly tested. They also argue that prevailing wage laws serve to promote worker safety and training, since payment of the prevailing wage is strongly associated with the use of union labor, and most union members go through apprenticeship training programs.

Thus, in addition to ensuring that public works projects pay adequate wages, prevailing wage laws, via their association with union labor, help create opportunities for advancement and

When do prevailing wage requirements apply to solar projects? Public Projects

Following the requirements of California’s prevailing wage law, any solar PV projects that are constructed for government entities and are funded by at least $1000 of state month must pay the prevailing wage. One notable program for solar PV for government entities is Proposition 39, which provides $550 million annually for five years for energy efficiency and clean energy projects for K-12 public school and community colleges.

However, because schools (and other government entities) are tax-exempt, many of these projects are instead owned by private third parties who are able to take advantage of the Federal Investment Tax Credit for 26% of project cost. The energy produced by the project is then sold to schools through a power purchase agreement (PPA), where the pricing terms are held constant for the duration of the contract, usually 20-25 years. This arrangement reduces project costs by 30%, which is then reflected in the pricing terms offered to schools. These projects, although owned by a private third party, are still required to pay prevailing wages because of a 2011 state law.

In 2011, Senate Bill (SB) 136 (Yee) was passed. It amended the definition of “public work” to include renewable energy projects built on state or municipal land where “[m]ore than 50% of the energy generated is purchased or will be purchased by the state or a political subdivision of the state (Public Contracts: Prevailing Wages., 2011).”

Utility-scale Projects

As noted in Section 1, utility-scale solar PV projects pay prevailing wage rates. However, utility-scale projects in California are privately financed (although all have received a federal tax credit of up to 30% of total project cost) and are therefore not subject to prevailing wage laws. Rather, the practice of paying prevailing wage is the result of successful negotiations by the State Building & Construction Trades Council of California (the Trades Council) with project developers. The resulting PLAs include the typical provision to use union labor, and as mentioned previously, in California the union wage rate is the prevailing wage rate.

Union Organizing

The Trades Council has successfully negotiated PLAs for most utility-scale solar PV projects in California. These projects require hundreds of workers across a number of skilled trades including

electricians, ironworkers, laborers and carpenters. Thus, utility-scale solar PV project appear ripe for the use of a PLA. The project contractor will be guaranteed a steady supply of workers and can ensure alignment of schedules across the various trades involved in the project. However, to the extent that PLAs increase labor costs, it is possible that project contractors may prefer to hire out work on a more piecemeal basis. For unions, PLAs on utility-scale projects offer jobs for hundreds of their members, and they have been able to negotiate contributions to union benefits and

apprenticeship programs.

Some have called into question the methods used by the Trades Council to secure PLAs for utility-scale renewable energy projects. Project developers and some unions not affiliated with the Trades Council claim that California Unions for Reliable Energy (CURE, which is affiliated with the Trades Council) raises environmental objections to gain leverage in labor negotiations (Lifsher, 2011; Woody, 2009). These developers and unions claim that CURE then drops its environmental

objections once it has secured a PLA. California Energy Commissioner Jeffrey Byron expressed skepticism at the tactic as well, saying “[t]his does stress the limits of credibility to some extent, when an attorney representing a labor union is so focused on the potential impact of a solar power plant on birds” (Woody, 2009). Jan Smutny-Jones of the Independent Energy Producers Assn. of California, an industry trade group, “described CURE as ‘professional litigants’ that exploit loopholes in the California Environmental Quality Act” (CEQA) and notes “that time is of the essence for all of these projects…. They don’t have a lot of time for lawsuits used to extract concessions from developers” (Lifsher, 2011).

For its part, CURE, which has a long history of advocating for union labor in power plant construction, says that its environmental objections come from a place of genuine concern for sustainability in the industry, and that “they do not abandon valid environmental objections to a project just because a company signs a labor agreement” (Woody, 2009). According to Woody (2009), this alleged negotiation tactic has long been the subject of discussion in the California legislature, which has considered bills that would bar labor form participating in environmental assessments, such as those required by CEQA. None of the bills have ever passed.

To the extent that intervention in environmental review processes does offer a point of leverage for labor advocates in negotiations with project developers, this same opportunity may not exist for many mid-size projects. Mid-size projects are more likely to be built on rooftops and parking lots, and these types of projects are exempt from CEQA review (Improving Permit Review and Approval for Small Solar Systems, 2019).

In addition to the lack of environmental review, the rooftop solar PV sector is composed of thousands of small projects that each employ only a handful of workers for a short period of time. Project contractors have less need for the no work stoppage guarantee offered by a PLA, and less need for a guaranteed supply of skilled workers. Similarly, unions may be less inclined to negotiate for a PLA because individual rooftop projects do not offer a large number of jobs for its members. Prevailing wage laws do not apply outside of projects for government entities. Without requirements for wage parity across companies or projects, or strong union involvement, the rooftop solar PV sector presents an opportunity for a race to the bottom. While there certainly are union contractors in the rooftop solar PV sector, they must compete for business with open-shop contractors who may be able to undercut them on total project cost due to their lower labor costs. This same danger exists for the mid-size solar PV sectors, as smaller projects may not garner the attention or interest of unions.

Labor & Environmental Justice

The development of solar PV in California has often put labor and environmental justice (EJ) advocates at odds with one another. Labor advocates (primarily unions affiliated with the Trades Council and the IBEW in particular) favor utility-scale projects because they create well-paying union jobs. EJ advocates, on the other hand, while certainly not opposed to well-well-paying jobs, are also interested in bringing the bill savings benefits of rooftop solar to disadvantaged

communities. This tension has played out most dramatically in the debates around NEM, with EJ advocates strongly in favor and labor advocates strongly opposed. EJ advocates argued that NEM is a key economic incentive for rooftop solar, while labor advocates argued that NEM acts as a cost shift from those who can install rooftop solar to those who cannot (Zabin et al., 2016). NEM was ultimately kept but updated, with adjustments to program rules and the compensation rates for electricity not used on-site.

Mid-size solar PV projects, such as those spurred by VNEM, community shared solar and the Solar on Multifamily Affordable Housing program, offer the potential to earn the approval of both groups; they certainly offer opportunities to expand solar PV bill savings to disadvantaged communities and, as we will explore more fully in Section 4, may offer the opportunity to create good quality jobs.