HAL Id: halshs-00117042

https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00117042

Submitted on 29 Nov 2006HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

The social multiplier and labour market participation of

mothers

Eric Maurin, Julie Moschion

To cite this version:

Eric Maurin, Julie Moschion. The social multiplier and labour market participation of mothers. 2006. �halshs-00117042�

Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne

UMR 8174

The Social Multiplier and Labour Market Participation of Mothers

Eric MAURIN

Julie MOSCHION

The Social Multiplier and Labour Market

Participation of Mothers

1.

Eric Maurin

2and Julie Moschion

3May 2006

1 We thank participants at the “Social Interactions and Network “ seminar in Paris and at the meeting of the

Abstract: In France as in the US, the participation of a mother in the labour market is

influenced by the sex of her oldest siblings. Same-sex mothers tend to have more children and to work significantly less than the other mothers. In contrast, the sex of the oldest siblings does not have any perceptible influence on neighbourhood choices. There is no correlation between the sex of the siblings of a mother and the sex of the siblings of the other mothers living in the same close neighbourhood. Given these facts, the distribution of the sex of the siblings of the other mothers provides us with a plausible instrumental variable to identify the influence of other mothers’ participation on a mother’s participation in the labour market. Reduced-form analysis reveals that a mother’s participation in the labour market is significantly affected by the sex of the oldest siblings of the other mothers living in the same neighbourhood. IV estimates suggest a strong impact of close neighbours’ participation in the labour market on individual participation. We compare this result to estimates produced using the distribution of children’s quarters of birth to generate instruments. Mothers whose children were born at the end of the year cannot send their children to pre-elementary school as early as the other mothers and participate less in the labour market. Interestingly enough, estimates using the distribution of quarters of birth in the neighbourhood as instruments are as strong as estimates using the sex-mix instruments.

Résumé: En France comme aux Etats-Unis, la participation d’une mère au marché du travail

est influencée par le sexe de ses aînés. Les mères ayant des enfants de même sexe ont tendance à avoir plus d’enfants et à travailler moins à l’extérieur du foyer que les autres mères. Par contre, le sexe des aînés n’a pas d’impact substantiel sur les choix résidentiels. Il n’y a aucune corrélation entre le sexe des aînés d’une mère et celui des autres mères du voisinage proche. Ainsi, la distribution du sexe des aînés des voisines constitue une variable instrumentale plausible pour identifier l’influence de la participation des voisines sur la participation d’une mère au marché du travail. L’analyse en forme réduite révèle que la participation d’une mère au marché du travail est significativement moins forte quand ses voisines ont des aînés de même sexe. Les estimations par variable instrumentale suggèrent un impact important de la participation des voisines proches sur la participation individuelle. Nous comparons ensuite ce résultat aux estimations obtenues en utilisant la distribution des trimestres de naissance du deuxième enfant comme instrument. Les mères dont le deuxième enfant est né à la fin de l’année ne peuvent pas l’inscrire en maternelle aussi tôt que les autres et participent plutôt moins au marché du travail. Les deux instruments donnent des résultats très proches quant à l’influence de la participation des voisines sur la participation individuelle.

Introduction

This paper provides an evaluation of the influence of close neighbours on a mother’s decision

to participate in the labour market. The question is whether the labour market behaviour of a

mother is influenced by that of the other mothers living in the same close neighbourhood. To

the best of our knowledge, there is still very little micro-economic evidence on the impact of

neighbours’ decisions on own labour market decision, even though social interactions has

long been identified as a potential explanation for the puzzling variation in labour market

outcomes across subgroups of workers, across time periods or across areas (see e.g. Alesina,

Glaeser and Sacerdote, 2005). As it turns out, the identification of neighbours’ influence on

own labour market decisions raises deep difficulties.

One issue is that neighbourhoods measured in available dataset are often considerably larger

than those which matters for outcomes (i.e., close neighbourhoods). Existing surveys on

neighbourhood interactions suggest that we actually interact with a very little number of close

neighbours only (2 or 3 maximum, see for example Héran, 1986). In contrast, studies on

neighbours’ influence typically proxy neighbourhood with census tracts that is, with very

large groups of people (several thousands). The survey used in this paper enables us to

overcome this problem. The sampling unit consists of small groups of about 20 to 30 adjacent

houses. It provides us with a large sample of mothers with detailed information on the

situation of all the other mothers living in their close neighbourhood. It makes it possible to

analyse how mothers living in adjacent houses actually influence each other4.

Another major issue is to isolate variation in neighbours’ labour market decisions which are

exogenous to own decisions. Women living in the same neighbourhood tend to take similar

participation decision. It is unclear whether it is because they influence each other or because

neighbours typically share the same background and the same preferences. Ideally, we would

like to analyse the behaviour of each mother depending on whether we facilitate or not

(experimentally) her neighbours’ participation in the labour market. Without such a controlled

experiment, our strategy has to rely on the observation of a variable which affects the decision

of each woman, but which has, as such, no effect on her neighbourhood choice nor on her

neighbours’ decisions. Specifically, the first identification strategy used in this paper is based

on the observation of the sex of the oldest siblings of families.

As shown below, the sex of the two oldest siblings has a significant influence on the final

number of children of a family and, consequently, on the participation in the labour market of

the mother. These relations are observed in France as in other countries (for the US case see

e.g. Angrist and Evans, 1998). In contrast, the sex of the two oldest children has no

perceptible influence on neighbourhood choice. We do not observe any significant residential

concentration of families having same-sex siblings. There is no significant correlation

between the sex of the two oldest siblings of a woman and the sex of the two oldest siblings of

her close neighbours. Given these facts, the observed shifts in the proportion of same-sex

siblings’ families across small neighbourhoods seem to be interpretable as quasi experimental

random shocks to the proportion of close neighbours participating in the labour market. This

is typically what is needed to isolate the influence of neighbours’ participation in the labour

market on an individual’s participation. Do mothers living near families with different-sex

The survey used in this paper provides us with a positive answer to this question. A mother’s

probability to participate in the labour market is significantly higher when the other mothers

in her close neighbourhood have different sex siblings than in the opposite case. This

difference is observed regardless of whether her own eldest siblings are same-sex or not.

Interestingly enough, the excess of participation in the labour market of a mother whose

neighbours have different-sex siblings is approximately as big as the excess of participation of

the neighbours themselves, due to their own children’s sex. Assuming that the sex of

neighbours’ siblings influence a woman’s participation only through its impact on their own

participation, this result suggests a strong causal impact of neighbours’ participation on a

woman’s participation. Using the sex of neighbours’ oldest children as an instrumental

variable, we obtain an estimation of the elasticity of a woman’s participation with respect to

her neighbours’ participation of about 0.8. According to our estimations, a 10 percentage

points increase in the participation rate of close neighbours increases a woman’s probability

of participation by about 8 percentage points.

We compare these findings to estimates produced using a completely different instrumental

variable, i.e., the distribution of quarters of birth of the other children living in the

neighbourhood. The participation of French mothers in the labour market is influenced not

only by the sex of her siblings, but also by their quarter of birth. Children born at the end of

the year cannot be sent at school as early as the other children and –because they are the less

mature of their year-group- perform less well at the beginning of primary school. Within this

context, mothers whose children were born at the end of the year are not less educated and do

not have more children than the other mothers, but have nonetheless less incentive to work

the variations in the proportion of children born at the end of the year across neighbourhood

can be used exactly as the variation in the proportion of same-sex families to identify the

endogenous social effect on mothers’ labour market participation. Most interestingly, the

quarter-of–birth instrument provides us with almost exactly the same evaluation of the

endogenous social effect as the same-sex instrument (i.e., +0.8).

This paper belongs to the literature which tries to clarify the contribution of social interactions

on women’s increased involvement in modern economies. We are not aware of studies

analysing the influence of close neighbours or friends on women’s labour market decisions.

Existing studies have mostly focused on social interactions between members of the same

(broadly defined) family. For example, Raquel Fernandez, Alessandra Fogli and Claudia

Olivetti (2004) make use of the difference across US states in the impact of WWII on

mother’s participation to show that a man who is brought up by a working mother is more

likely to be married to a woman who works. The authors build on this result to argue that a

determinant of the increase in women’s involvement in the labour market has been the

increasing number of men who, over time, grew up with a different family model. In a related

paper, David Neumark and Andrew Postlewaite (1998) suggest that women’s decisions to

participate in the labour market are influenced by the decision of their sisters and by the social

status of their sisters in law (see also Daniela Del Boca, Marilena Locatelli and Silvia Pasqua,

2000).

At a more general level, Claudia Goldin (2006) describes how each generation of women has

been influenced by its immediate predecessors and how this process progressively altered the

identity of women and shifted it from a family centred world to a more career oriented one.

women’s educational and occupational choices cannot be fully understood without taking

social interactions into account. They argue that when a woman decides to delay marriage, her

potential spouses remain in the marriage market longer and, consequently, remain available to

other women. Hence, any exogenous shock delaying one woman’s marriage (such as pill

availability) diminishes the costs for other women to delay their own marriage and this creates

social multiplier effects.

Our study can also be seen as a contribution to the literature which tries to understand the

variation in labour market outcomes across areas or across subgroups of workers within areas.

Alberto Alesina, Edward Glaeser and Bruce Sacerdote (2005) argue that part of the very

strong difference in labour market outcomes between the US and Europe is due to positive

complementarities across people in the enjoyment of leisure time. They provide several pieces

of evidence which support the assumption that one person’s leisure increases the returns to

other people’s leisure. One such piece of evidence is the strong convergence to a common two

days week-end (i.e., Saturday and Sunday) despite the many disadvantages of crowding

infrastructure usage during five days and living this infrastructure underutilized during two

other days.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides a description of the data used in the

paper. Section 3 shows the influence of the sex of the oldest siblings on the labour market

participation of French mothers. Section 4 provides several pieces of evidence suggesting that

the sex of the two oldest siblings does not influence neighbourhood choices. Section 5

estimates the (strong) influence on a mother’s participation in the labour market of her

neighbours’ participation, using the sex of the two oldest siblings of the neighbours as an

instrumental variable. Section 6 compares the estimates obtained with the quarter-of-birth

II Data Description

The data used in this paper come from the 12 French Labour Force Surveys (LFS) conducted

each year between 1990 and 2001. One interesting feature of the French LFS is that the basic

sampling units actually consist of groups of about 20 adjacent households (aires). More

specifically, a typical LFS consists of a representative sample of about 3,500 aires. Each year,

within each aire, all the households are surveyed and, within each household, all the persons

aged 15 or more are surveyed. The French statistical office (INSEE) has chosen this sampling

strategy in order to reduce the travelling expenses of the investigators who are in charge of the

survey.

For each respondent, we have standard information on his date of birth, sex, family situation,

place of birth, education, labour market situation (unemployed, out of the labour force,

employed). Also, for each household, we know the number, sex and birth date of the children

living in the home.

We focus on the sample of mothers aged 21 to 35 years old, living in two-parents families and

having at least two children at the time of the survey (N = 30,423). As Angrist and Evans

(1998), we only have information on children still living with their parents: the LFS does not

follow children outside the parental home. Focusing on mothers who are less than 35 prevents

us from underestimating women’s total number of children and from introducing errors on the

rank of the children in the family. Women who are more than 35 possibly have of age

children, who then have a higher probability of having left the parental home. Another interest

of concentrating on 21-35 years old mothers is that our analysis of the links between the sex

of the oldest siblings and the individual labour supply (first stage) is directly comparable with

For each woman in our sample, we observe on average four other women with two or more

children living in the same small neighbourhood.

For each woman in our sample, the basic dependent variable will be a dummy indicating

whether she participates in the labour market and the basic independent variables will be a

dummy indicating whether her two eldest children are same-sex and a dummy indicating the

quarter of birth of the second child. Also, for each woman, we construct several explanatory

variables describing the average characteristics of the other families with two or more

children living in her aire, namely the proportion of families in which the two eldest children

are same sex, the proportion of families whose second child was born at the end of the year

and the proportion of families where the mother participates in the labour market. Using the

terminology of Manski (1993), the impact of other mothers’ labour market participation on a

mother’s participation in the labour market corresponds the endogenous effect. Let us

emphasize that, for each respondent, the different aire-level indicators are constructed using

only the information on the individuals who do not belong to the family of the respondent.

As far as we know, there exist no studies on the effect of neighbours’ influcence on mothers’

participation in the labour market. However, in the early 1980’s, the French Statistical Office

has carried out an interesting study on the intensity of social interactions within

neighbourhoods. One of the clearest result is that we interact with a very little number of

neighbours (2 or 3 on average). Also the relationships with neighbours are maintained mostly

by women, and especially women with children. What emerges from this study is that

mothers are actually much more exposed than others to the effect of neighbourhood

interactions. The results of this study backs up our choice of focusing the analysis on women

III Sex of oldest siblings, fertility and participation in the labour market

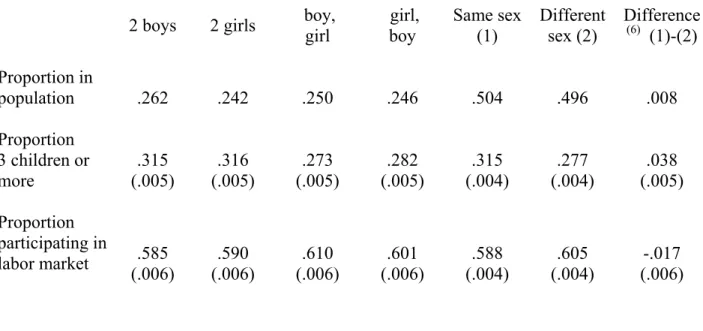

Table 1 analyses the participation in the labour market of the mothers in our sample according

to the sex of the two oldest siblings. Among mothers with same sex siblings, the proportion of

working women (0.588) is about 1.7 points lower than among mothers with different sex

siblings (0.605). This difference is perceptible regardless of whether the first born is a boy or

a girl, even if it is clearer (2.2 points) when it is a boy. Mothers’ participation is not as well

measured in the general census of the population as in the LFS. However, we have checked

that the last census of the population (carried out in 1999) provides the same kind of result:

mothers whose two oldest children are same-sex work significantly less than others, the

difference being a little more than 1.1 point. On American data, Angrist and Evans (1998) put

forward the same type of correlation but the magnitude is lower than in France.

There are several potential explanations to this relation between the sex of the oldest siblings

and the participation of mother in the labour market (see e.g. Rosenzweig and Wolpin, 2000).

Having same sex children may lower family spendings and make it less urgent for the mother

to work (direct effect). The most plausible explanation is indirect, however: the sex of the

oldest siblings influences the participation of mothers because it affects the final number of

children in the family. As in the United States, French mothers with two girls or two boys are

more inclined to have a third child than mothers who already have a boy and a girl (Goux and

Maurin, 2005; Angrist and Evans, 1998). Table 1 confirms that the proportion of families with

at least three children is 4 points higher in families where the oldest siblings are same-sex

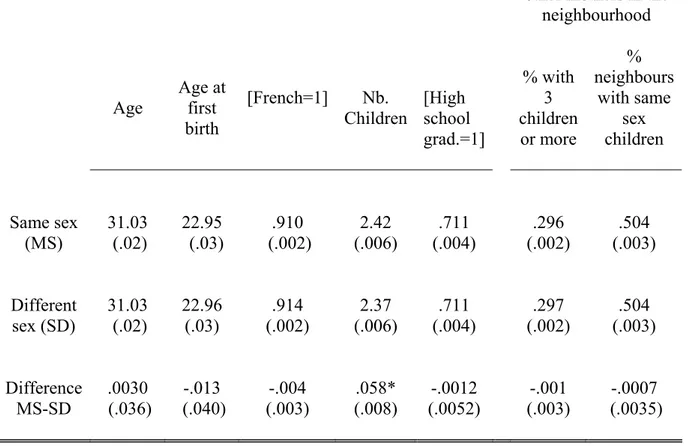

(31.5%) than in families where the oldest siblings are different sex (27.7%). Table 2 shows

that these differences in the final number of children according to the sex of the oldest

siblings cannot be explained by differences in the standard individual determinants of fertility.

between mothers according to the sex of their oldest siblings. What is at stake here really

seems to be a preference of parents for mixed sex siblings and it is this preference that

influences the participation decisions of mothers.

These results are consistent with the literature, and notably with the results of Angrist and

Evans (1998): the sex of the two oldest siblings affects the final number of children, but also

the participation of mothers in the labour market. The magnitude of the effect of the

children’s sex on fertility and participation is however different in their study on American

data than in our French study, even though the method and the samples are defined the same

way. The sex of the two oldest siblings have a lower impact on fertility in France than in the

United States (about 6 points in the United States against 4 points here), but a higher impact

on mothers’ participation (-0.5 points in the US against -1.7 in France).

Assuming that the sex of the oldest siblings affects the participation of mothers only because

it influences the final number of children, the ratio between the impact of the sex of the two

oldest siblings on participation and its impact on fertility gives us an estimate of the causal

effect of having a third child on the mothers’ probability of participating in the labour market.

This Wald estimate (about -0.4) suggests a higher elasticity in France than that estimated by

Angrist and Evans (1998) in the US (about -0.1). The final number of children seems to have

a more negative impact on mothers’ participation in France than in the US. This difference

has plausibly deep institutional causes, which analysis would exceed the scope of this paper.

For now, it is enough remembering that the sex of the two oldest siblings influences the

participation of French mothers more than American ones and that this is probably because

the effect of the number of children on mothers’ participation is more negative in France than

IV Sex of oldest siblings and neighbourhood choice

The sex of the two oldest siblings determines the decision of having a third child. But the

birth of a third child often entails a change of neighbourhood. Hence, we cannot exclude that

the sex of the two oldest siblings also determines (indirectly) the neighbourhood in which

mothers bring up their children and take their labour market decisions.

If this was the case, the sex of the two oldest siblings of a family would be correlated with the

sex of the two oldest siblings of other families in the neighbourhood. Interestingly enough, we

observe no correlation of this type. Mothers with same-sex siblings do not have more

neighbours with same-sex siblings or with three or more children than other mothers (see

table 2, last columns). The data do not show any perceptible residential concentration of

same-sex families. This result is consistent with the assumption that the sex of the oldest

siblings is exogenous to neighbourhood selection.

It is possible to carry out an alternative test of this hypothesis by using the set of Labour Force

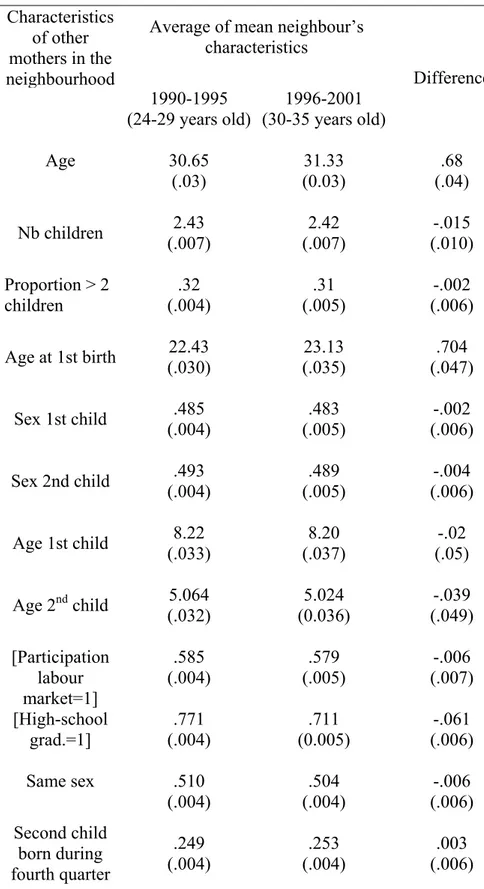

Surveys as a pseudo-panel. Tables 3 and 4 focus on mothers with two children or more

observed in surveys carried out between 1990 and 2001. We compare the sub-sample of

mothers aged 24 to 29 between 1990 and 1995 with the sub-sample of mothers aged 30 to 35

between 1996 and 2001 (and who had at least two children born before 1996). We then have

the same cohort six years apart. Table 3 retraces the evolution of the personal situation of the

members of this cohort between the two sub-periods. Table 4 describes the evolution of their

close neighbours, i.e. the characteristics of other mothers with at least two children living in

the same neighbourhood. Regarding the individual situation of these mothers, some

characteristics (as the diploma or the sex of the two oldest siblings) are fixed by definition.

Also the evolution of the age of mothers across subsamples follows directly from the

approximately six years older than the ones in the first sub-sample. Likewise, their two oldest

children are about six years older. In fact, from the personal viewpoint, only two parameters

change at this turning point of life: the participation in the labour market - which rises

slightly5 - and above all the number of children, since the proportion of mothers having at

least three children is multiplied by 2.5 in six years (57% after age 30 against 23% before). As

a matter of fact, it is around their thirties that most French mothers decide or not to have a

third child. The issue is to understand whether this turning point of their mother’s life goes

also with significant changes in the quality of their neighbourhood. Table 4 brings some

elements of answer. It details the average situation of other mothers living in the same close

neighbourhood as the members of our cohort, when the later are 24-29 years old on the one

hand, and 30-35 years old on the other hand. It reveals that after the age of thirty, the

members of our cohort of mothers live in neighbourhoods in which other mothers are a little

bit older and slightly less graduated than before thirty. But, there is no significant difference

in the proportion of neighbours having three or more children or having same-sex oldest

siblings. Again, this result may be interpreted as the fact that there is no neighbourhood

specialised in the reception of families with three or more children. It does not seem possible

to link the birth of a third child with moving into a neighbourhood better adapted to families

with three children or more.

V The influence of neighbours’ behaviour on own behaviour

The sex of the two oldest children of a woman is a determining factor of her participation in

the labour market, plausibly because it determines her final number of children. On the other

sex of the two oldest siblings of the other families in the neighbourhood. The sex composition

of the siblings does not seem to influence directly or indirectly the choice of the

neighbourhood. Given these facts, the variation across neighbourhoods in the distribution of

the two oldest siblings’ sex provides us with a natural experiment, enabling us to identify the

effect of neighbours’ participation on own participation in the labour market.

To be more specific, assume that the participation decisions of the family i are given by:

(1) Pi = aVPi+ bSi + ui

where Si indicates if the two oldest children are same sex, Pi indicates if the mother

participates in the labour market and VPi represents the proportion of i’s neighbours who

participate in the labour market. The variable ui represents the set of individual and/or

contextual factors (other than VPi and Si) that affects the participation decision of i. The

parameter a represents the influence of the context that we want to identify, the parameter b

represents the set of direct and indirect influences (particularly via the size of the sibship) of

the sex of the two oldest siblings on the participation decisions. It corresponds to the reduced

form of a very simple sequential model: given the sex of their two oldest children and the

context they live in after the birth of the second child, parents decide or not to expand the

family and/or to move. Once these decisions are taken, mothers decide or not to participate in

the labour market according to the final size of their family and to the general context, notably

to their neighbours decision6.

Averaging equation (1) and reorganizing, the proportion VPi can be written :

(2) VPi = cVSi +dSi + vi

6It should be emphasized that this model does not exclude that the proportion of neighbours having 3 children or

more may have influenced the decision of expanding the family. We do not isolate this particular factor of fertility as we are not able to identify the neighbourhood in which the decision to have a third child has been taken (notably for mothers who moved between the second and the third child). Our data do not enable us to analyse contextual effects on fertility. This is why we work directly on a reduced-form (2), without further

where VSi represents the proportion of neighbours having same sex children, where the

new residual vi is a linear combination of the uj residuals affecting the decisions Pj of i’s

neighbours, and the parameter c is proportional to b and the parameter d is proportional to ab.

Assuming that (1) b is not equal to zero (i.e., the sex of the two older children really affects –

directly or indirectly- the participation in the labour market) and (2) S is not correlated with

the neighbourhood characteristics that affects fertility decisions and the participation of the

inhabitants (i.e.,E(Siuj )= 0, there is no correlation between the sex of the two oldest children

and the other factors affecting the neighbourhood participation), the proportion of same sex

neighbours (VSi) provides us with an instrumental variable which influences individual

participation decisions (P) only because it influences the proportion of working women in the

neighbourhood VPi. The next section proposes an evaluation of a using this instrumental

variable.

Results

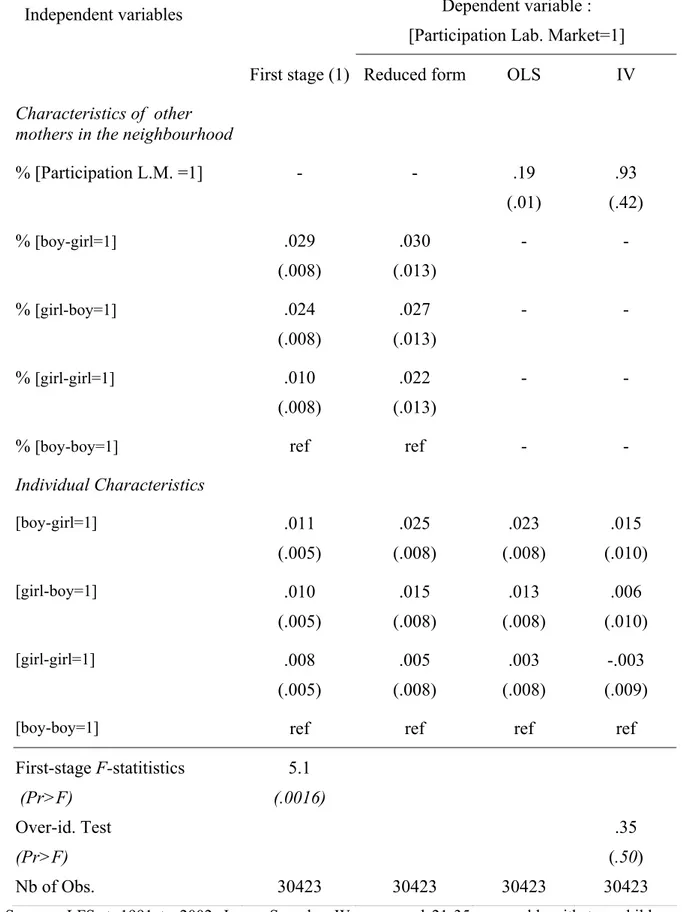

The first column of Table 5 shows the results of the estimation of equation (2). This first stage

regression confirms the existence of a significant negative effect of the proportion of

neighbours having same-sex children on their own rate of labour market participation. The

proportion of mothers participating in the labour market is 2.2 percentage points larger when

their siblings are different-sex than when they are same-sex. The second column presents the

regression of a woman’s participation in the labour market on the sex of her two oldest

children and the sex of the two oldest children of the other women living in the

neighbourhood. Interestingly enough, this reduced form equation shows the existence of a

sex on her own participation. A mother’s probability to participate in the labour market is 1.8

percent points larger when the other mothers have different-sex rather than same-sex siblings.

The sex composition of the siblings of neighbours has almost the same effect on a women’s

participation than on the participation of her neighbours themselves. This result suggests a

strong elasticity between a woman’s participation and that of her neighbours. As a matter of

fact, the elasticity estimated by the IV method is 0.8 (column 4). A 10 percent points increase

in the proportion of neighbours participating in the labour market generates a 8 percent points

increase in the probability of participation of a woman.

Table 6 provides an alternative evaluation using a characterization of the sex composition of

the siblings by a complete set of three dummies (boy-girl, girl-boy, girl-girl, and boy-boy

being the ref.) rather than by a single same-sex dummy variable. The first-stage F-statistics

shows that the proportions boy-girl, girl-boy and girl-girl in the neighbourhood represents a

set of relatively powerful instruments (P>.01). The IV estimates are very similar to those

obtained in Table 5, but better estimated. The over-identifying restrictions are not rejected at

standard level. Comfortingly, the sex composition of the siblings has the same impact on own

participation in the labour market as on neighbours’ participation. Families with two boys

participate relatively less than other families. Also, they increase the participation of their

neighbours families relatively less than other families. In contrast, families with a boy and a

girl participate relatively more and increase the participation of their neighbours relatively

more than the other families.

The IV estimate is higher than the OLS estimate (0.2), even if strictly speaking the difference

between the two estimates is not significant. It is something of a puzzle, since endogenous

neighbourhood selection is typically likely to bias OLS coefficient upward7. One possible

explanation is that we measure P with an error that affects mechanically VP, the explanatory

variable of interest. This results in an attenuation bias on the OLS estimate. The bias is all the

more significant that the variance of the errors is large. If this interpretation is correct, the

difference between the OLS and the IV estimate should decrease when focusing on

neighbourhoods with more mothers (i.e., a smaller variance in the error affecting the

measurement of VP). This is actually what we observe: the OLS estimate is about three times

as large (about 0.5) when we restrict the sample to neighbourhoods with at least 7 neighbours,

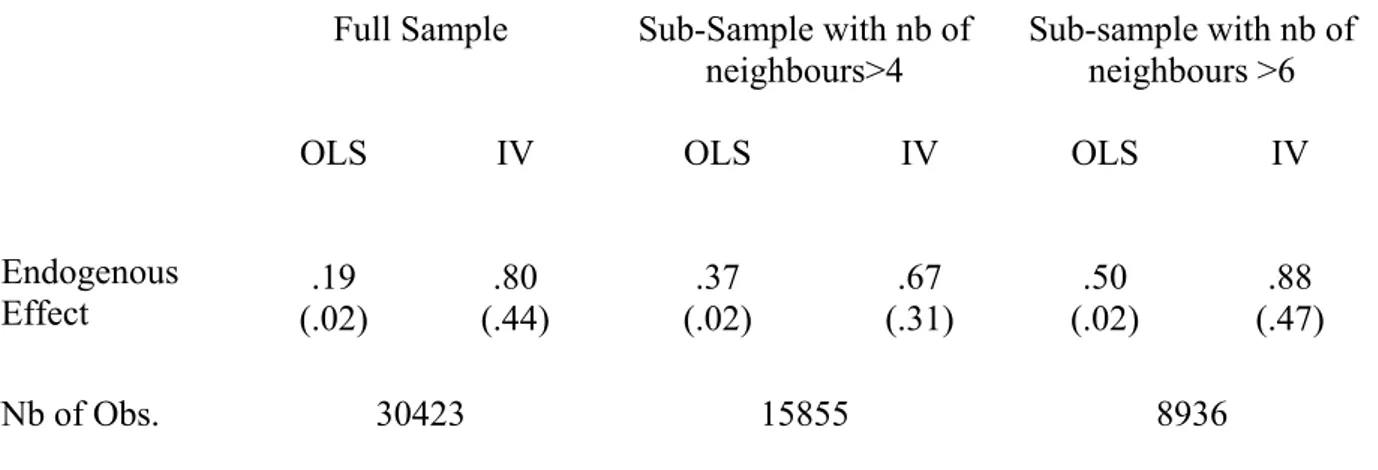

whereas the IV estimate is almost unchanged (see Table 7).

VI An evaluation using children’s quarter of birth as an instrument

This section compares the estimates produced using the sex-mix instrument to estimates

obtained with the distribution of quarters of birth of the other children in the neighbourhood.

Specifically, our second identifying strategy builds on the fact that French mothers’ whose

children were born at the end of the year participate less in the labour market than other

mothers, due to specific feature of the French pre-elementary and elementary schools.

Children born at the end of the year cannot attend school as early as the other children,

because of the specific enrolment rules of French pre-elementary schools8. Also, pupils born

at the end of the year are the youngest of their year-group and, as a consequence, perform less

under assumption that persons with good unobservables have also good outcomes and live in good

neighbourhood. A similar finding is reported by Goux and Maurin (2006) in their analysis of neighbourhood effects on early performance at school.

8 In France, the majority of children begin pre-elementary public school in september of the year of their third

birthday. A significant fraction (about 30%) are even allowed to begin school one year earlier, in september of the year of their second birthday. School heads are asked to give priority to children whose second birthday is before september, however (i.e., to children who are actually 2 years old in september). As a consequence, the

well at the beginning of primary school9. Within this framework, mothers whose children

were born at the end of the year have more incentive to stay at home with their children and

less incentive to work.

When we focus on the sample of mothers with two or more children, our data confirm that

those whose second child was born at the end of the year participate significantly less in the

labour market than the other mothers (Table 8, first column). Also Table 8 shows that this

participation gap cannot be explained by variation in births’ seasonality across mothers’ with

different background. Mothers whose second child was born during the last quarter of the year

are neither more educated, nor older, nor more often non-French than the other mothers. They

do not have more children either. Also, the LFS data do not reveal any specific residential

concentration of families whose second children were born at the end of the year. Table 4

confirms that the proportion of neighbours whose children were born at the end of the year

does not vary across a mother’s life cycle. Given these facts, the variation across

neighbourhoods in the proportion of mothers whose second child was born at the end of the

year provides us with a plausible alternative instrument for identifying the impact on a

mother’s labour market participation of the participation of the other mothers living in the

same neighbourhood.

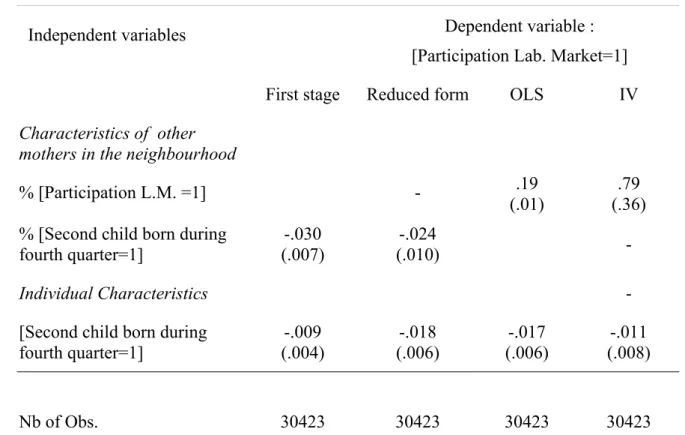

The first-stage regression confirms that the proportion of mothers in the neighbourhood who

participate in the labour market is negatively correlated with the proportion of mothers whose

second-born children were born at the end of the year (Table 9, column 1). Most interestingly,

the reduced-form regression reveals that a mother’s probability of participating in the labour

market is significantly reduced when the children of the other mothers were born at the end

rather than at the beginning of the year. The last column shows the result of a regression of a

9 The national evaluations conducted each year at entry into third grade show an average difference of about 1/2 of a standard deviation between the scores of children born in January (the most mature of their year-group) and those of children born in December (the least mature).

mother’s participation in the labour market on the participation of the other mothers, using the

quarter of birth of the children of the other mothers as an instrumental variable. The IV

estimate is as large as the estimate obtained with the sex-mix instrument.

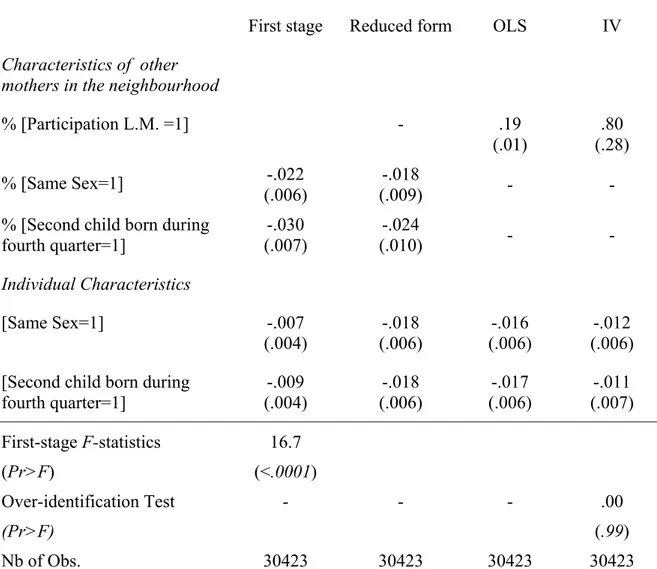

Table 10 shows the results of first-stage and second-stage regressions when we use jointly the

same-sex and quarter-of-birth instruments to identify the endogenous social effects. The

first-stage F-statistics shows that the proportions boy-girl, girl-boy and girl-girl in the

neighbourhood represents a set of powerful instruments. Also over-identification restrictions

are not rejected. We find almost exactly the same IV estimates as when the instruments are

used separately, but they are estimated much more precisely.

VII Conclusion

A mother’s decision to participate in the labour market is correlated with those of the other

mothers living in the same neighbourhood. This paper studies the extent to which this is

causal. An identification problem exists because mothers with similar characteristics are often

observed living in close proximity. Another difficulty is that neighbourhoods measured in

available datasets are typically larger than those which actually matter for outcome (i.e., close

neighbourhoods). The French Labour Force Surveys enable us to overcome this problem and

to consider the effect of close neighbours on own outcomes because of the nature of data

collection: the basic sampling units consist of groups (aires) of 20 to 30 adjacent households.

Our identifying strategy uses instrumental variables. In France, the sex of the two oldest

siblings has a significant impact on the decision of mothers to participate in the labour market.

The effect is actually stronger than in the US. In contrast, the sex of the two oldest siblings

across same-sex and different-sex mothers. Given these facts, the distribution of the sex of the

oldest siblings of the neighbours provides us with a plausible instrument to identify the

effect of neighbours’ participation in the labour market on own participation. Interestingly

enough, the reduced-form analysis shows a significant influence of the sex of the neighbours’

siblings on own participation and the IV estimate suggests a very strong elasticity of own

participation to neighbours participation. We compare this result to estimates produced using

the distribution of children’s quarters of birth to generate instruments. Mothers whose

children were born during the fourth quarter of the year cannot send their children to

pre-elementary school as early as the other mothers and participate less in the labour market.

Interestingly enough, estimates using the distribution of quarters of birth in the neighbourhood

as instruments are as strong as estimates using the sex-mix instrument. Understanding

variation in women’s labour supply across areas and over time is a very difficult task. This

paper suggests that one plausible explanation is the existence of a strong social multiplier,

where the utility of not working is strongly linked to the proportion of close neighbours who

do not work.

References:

Alesina, Alberto, Edward Glaeser, and Bruce Sacerdote (2005), “Work and Leisure in the US and Europe: Why so Different”, Unpublished Manuscript.

Angrist Joshua D. and Evans, William N., (1998) "Children and Their Parents' Labour Supply: Evidence from Exogenous Variation in Family Size," American Economic Review, American Economic Association, vol. 88(3), pages 450-77.

Case, Anne C. and Lawrence F. Katz, 1991. "The Company You Keep: The Effects of Family and Neighbourhood on Disadvantaged Youths," NBER Working Papers 3705, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Del Boca, Daniela, Locatelli, Marilena and Silvia, Pasqua (2000), " Employment Decisions of Married Women: Evidence and Explanations," Labour, 14 (1), 35-52.

Fernandez, Raquel, Alessandra Fogli and Claudia Olivetti (2004) “Mothers and Sons: Preference Development and Female Labor Force Dynamics,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(4): 1249-1299, November 2004

Goldin, Claudia (2006), “The Quiet Revolution That Transformed Women’s Employment, Education and Family”, NBER Working Paper 11953.

Goldin, Claudia, and Lawrence F. Katz (2002), “The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women’s Career and Marriage Decisions”, Journal of Political Economy, 110 (4), pp:730-70.

Goux, Dominique, and Eric Maurin (2005), “The Effect of Overcrowded Housing on Children’s Performance at School”, Journal of Public Economics, vol:89, August pp.

Goux, Dominique, and Eric Maurin (2006), “Close Neighbours Matter: Neighbourhood Effects on Early Performance at School”, Revised Version, Unpublished Manuscript.

Héran, François, (1986), "Comment les Français voisinent", Economie et Statistique, n° 195, pp. 43-59.

Ioannides, Yannis M., (2002), "Residential Neighbourhood Effects", Regional Science and Urban Economics, 32,2, 2002, 145-165.

Ioannides, Yannis M., (2003), "Interactive Property Valuations", Journal of Urban Economics, 56, 435-457.

Ionnadies, Yannis M. and Jeffrey E. Zabel, (2003), "Neighbourhood Effects and Housing Demand", Journal of Applied Econometrics, 18, 563-584.

Manski, Charles F. (1993) " Identification of Endogenous Social Effects : The Reflection Problem ", Review of Economic Studies, 60:531-542.

Neumark, David and Andrew Postlewaite, (1998) “Relative Income Concerns and the Rise in Married Women's Employment", Journal of Public Economics, 70, pp. 157-183.

Rosenzweig, Mark R. and Kenneth I. Wolpin, (2000) “Natural “Natural Experiment” in Economics”, Journal of Economic Literature, American Economic Association, vol. 38(4) pp. 827-874.

Table 1 : Impact of the sex of the two oldest children on mothers’ fertility and participation Sex of the two oldest children

2 boys 2 girls boy, girl girl, boy Same sex (1) Different sex (2) Difference (6) (1)-(2)

Proportion in population .262 .242 .250 .246 .504 .496 .008 Proportion 3 children or more .315 (.005) .316 (.005) .273 (.005) .282 (.005) .315 (.004) .277 (.004) .038 (.005) Proportion participating in labor market .585 (.006) .590 (.006) .610 (.006) .601 (.006) .588 (.004) .605 (.004) -.017 (.006) Source : LFS 1990-2002.

Table 2 : Demographic differences between mothers according to the sex of their two eldest children .

Individual characteristics of the mother Characteristics of the other mothers in the

neighbourhood Age Age at first birth [French=1] Nb.

Children [High school grad.=1] % with 3 children or more % neighbours with same sex children Same sex (MS) 31.03 (.02) 22.95 (.03) .910 (.002) 2.42 (.006) .711 (.004) .296 (.002) .504 (.003) Different sex (SD) 31.03 (.02) 22.96 (.03) .914 (.002) 2.37 (.006) .711 (.004) .297 (.002) .504 (.003) Difference MS-SD .0030 (.036) -.013 (.040) -.004 (.003) .058* (.008) -.0012 (.0052) -.001 (.003) -.0007 (.0035) Source : LFS 1990-2002.

Table 3 : Evolution of mothers’ demographic characteristics according to their age : a pseudo-panel analysis of the cohort observed in 1990-1995 and 1996-2001.

Average of individual characteristics

1990-1995

(24-29 years old) (30-35 years old) 1996-2001

Difference Age 27.30 (.02) 33.29 (.02) 5.99 * (.03) Number of children 2.28 (.008) 2.81 (.013) .52 * (.01) Proportion > 2 children .23 (.006) .57 (.007) .34 * (.009) Age at first birth 21.38 (.038) 21.50 (.038) .12* (.05) Sex 1st child .483 (.007) .484 (.007) .001 (.010) Sex 2nd child .494 (.007) .488 (.007) -.006 (.010) Age 1st child 5.93 (.038) 11.79 (.038) 5.86* (.05) Age 2nd child 3.05 (.037) 8.93 (.037) 5.88* (.05) [Participation labour market=1] (.007) .544 (.007) .619 (.010) .075* [High-school grad.=1] (.006) .797 (.006) .800 (.008) .003 Same sex .502 (.007) (.007) .504 (.010) .002 Second child born during fourth quarter .247 (.006) .256 (.006) .009 (.009)

Source : LFS 1990-2002. Sample : Women observed in 1990-1995 when aged 24-29 years old and with 2 children or more. The table compares their average characteristics in 1990-1995 with their average characteristics six years later in 1996-2001. Reading: When we follow over time the cohort of mothers observed in the LFS 1990-1995 at the age of 24-29, we find that the proportion with three

Table 4 : Evolution of the demographic characteristics of the other mothers living in the neighbourhood according to a mother’s age: a pseudo-panel analysis of the cohorts observed in 1990-1995 and 1996-2001.

Characteristics of other mothers in the neighbourhood

Average of mean neighbour’s characteristics 1990-1995 (24-29 years old) 1996-2001 (30-35 years old) Difference Age 30.65 (.03) (0.03) 31.33 (.04) .68 Nb children (.007) 2.43 (.007) 2.42 (.010) -.015 Proportion > 2 children (.004) .32 (.005) .31 (.006) -.002 Age at 1st birth 22.43 (.030) 23.13 (.035) .704 (.047) Sex 1st child .485 (.004) .483 (.005) -.002 (.006) Sex 2nd child .493 (.004) .489 (.005) -.004 (.006) Age 1st child 8.22 (.033) 8.20 (.037) -.02 (.05) Age 2nd child 5.064 (.032) 5.024 (0.036) -.039 (.049) [Participation labour market=1] .585 (.004) .579 (.005) -.006 (.007) [High-school grad.=1] .771 (.004) .711 (0.005) -.061 (.006) Same sex .510 (.004) .504 (.004) -.006 (.006) Second child born during fourth quarter .249 (.004) (.004) .253 (.006) .003

Table 5 : The Endogenous Effect on Mothers’ Labour Market Participation : an Evaluation using the Proportion of Same-Sex Families in the Neighbourhood as an Instrumental Variable.

Independent variables Dependent variable : [Participation Lab. Market=1] First stage (1) Reduced form OLS IV

Characteristics of other mothers in the neighbourhood

% [Participation L.M. =1] - - .19 (.01) .80 (.44) % [Same Sex=1] -.022 (.006) -.018 (.009) - - Individual Characteristics [Same Sex=1] -.07 (.004) -.018 (.006) -.016 (.006) -.012 (.007) Nb of Obs. 30423 30423 30423 30423

Source : LFS, t=1991 to 2002, Insee. Sample : Women aged 21-35 years old, with two children or more.

Note (1): The dependent variable of the first-stage regression is the proportion of other mothers in the neighbourhood participating in the labour market. The dependent variable of the other regression is the individual participation in the labour market.

Table 6 : The Endogenous Effect on Mothers’ Labour Market Participation : an Evaluation using the Sex Composition of Other Families in the Neighbourhood as an Instrument.

Independent variables Dependent variable : [Participation Lab. Market=1] First stage (1) Reduced form OLS IV

Characteristics of other mothers in the neighbourhood

% [Participation L.M. =1] - - .19 (.01) .93 (.42) % [boy-girl=1] .029 (.008) .030 (.013) - - % [girl-boy=1] .024 (.008) .027 (.013) - - % [girl-girl=1] .010 (.008) .022 (.013) - -

% [boy-boy=1] ref ref - -

Individual Characteristics [boy-girl=1] .011 (.005) .025 (.008) .023 (.008) .015 (.010) [girl-boy=1] .010 (.005) .015 (.008) .013 (.008) .006 (.010) [girl-girl=1] .008 (.005) .005 (.008) .003 (.008) -.003 (.009)

[boy-boy=1] ref ref ref ref

First-stage F-statitistics (Pr>F) 5.1 (.0016) Over-id. Test (Pr>F) .35 (.50) Nb of Obs. 30423 30423 30423 30423

Source : LFS, t=1991 to 2002, Insee. Sample : Women aged 21-35 years old, with two children or more. Note (1): The dependent variable of the first-stage regression is the proportion of other mothers

Table 7: Variation in OLS and IV estimates of the endogenous effect across sub-samples Full Sample Sub-Sample with nb of

neighbours>4

Sub-sample with nb of neighbours >6

OLS IV OLS IV OLS IV

Endogenous

Effect (.02) .19 (.44) .80 (.02) .37 (.31) .67 (.02) .50 (.47) .88

Nb of Obs. 30423 15855 8936

Table 8 : Demographic differences between mothers according to the quarter of birth of their second child .

Individual characteristics of the mother Characteristics of the other mothers in the

neighbourhood Particip. in Lab. Market. Age Age at first birth [French=1] Nb Child. [High-school grad.=1] % with 3 children or more % second child born in Q1 Born fourth quarter (Q1) (.0057) .582 30.97 (.036) 23.01 (.039) .912 (.003) 2.39 (.008) .711 (.005) .503 (.004) .258 (.003) Born before fourth quarter (Q0) .601 (.032) 31.05 (.021) 22.94 (.023) .912 (.002) 2.39 (.004) .711 (.003) .505 (.002) .248 (.002) Diff. (Q1-Q0) -.019* (.006) (.041) -.078 (.046) .069 (.0037) .0003 (.0095)-.0036 (.006) -.003 (.0041) -.0021 (.004) .010 Source : LFS 1990-2002. Sample : Women aged 21-35 years old, with two children or more.

Table 9 : The Endogenous Effect on Mothers’ Labour Market Participation : an Evaluation using the Proportion of Children Born at the End of the Year as Instrument

Independent variables Dependent variable : [Participation Lab. Market=1] First stage Reduced form OLS IV

Characteristics of other mothers in the neighbourhood

% [Participation L.M. =1] - .19 (.01)

.79 (.36) % [Second child born during

fourth quarter=1] -.030 (.007) -.024 (.010) - Individual Characteristics -

[Second child born during fourth quarter=1] -.009 (.004) -.018 (.006) -.017 (.006) -.011 (.008) Nb of Obs. 30423 30423 30423 30423

Source : LFS, t=1991 to 2002, Insee. Sample : Women aged 21-35 years old, with two children or more, living in areas with less than 100,000 hab.

Note (1): The dependent variable of the first-stage regression is the proportion of other mothers in the neighbourhood participating in the labour market. The dependent variable of the other regression is the individual participation in the labour market.

Table 10 : The Endogenous Effect on Mothers’ Labour Market Participation : an Evaluation using Jointly Quarter-of-Birth and Sex-mix Instruments.

Independent variables Dependent variable : [Participation Lab. Market=1] First stage Reduced form OLS IV

Characteristics of other mothers in the neighbourhood

% [Participation L.M. =1] - .19 (.01) .80 (.28) % [Same Sex=1] -.022 (.006) -.018 (.009) - -

% [Second child born during

fourth quarter=1] (.007) -.030 (.010) -.024 - -

Individual Characteristics

[Same Sex=1] -.007

(.004) (.006) -.018 (.006) -.016 (.006) -.012 [Second child born during

fourth quarter=1] -.009 (.004) -.018 (.006) -.017 (.006) -.011 (.007) First-stage F-statistics (Pr>F) 16.7 (<.0001) Over-identification Test (Pr>F) - - - .00 (.99) Nb of Obs. 30423 30423 30423 30423

Source : LFS, t=1991 to 2002, Insee. Women aged 21-35 years old, with two children or more, living in urban area with more than 100,000 hab.

Note (1): The dependent variable of the first-stage regression is the proportion of other mothers in the neighbourhood participating in the labour market. The dependent variable of the other regression is the individual participation in the labour market.

Appendix

Consider a neighbourhood of size n and let P represent the (n,1) vector of dummies

characterizing mothers’ participation, S the (n,1) vector of dummies characterizing oldest

siblings’ sex, and U the vectors of residuals. Equation (1) can be rewritten,

(1) MP=bS+U

where M is a (n,n) matrix such that

m(i,i)=1 and m(i,j)=m=-a/(n-1) for i different from j.

It is easy to check that Q=M-1 is a (n,n) matrix such that

q(i,i)=q1=(1+(n-2)m)/(1+(n-2m-(n-1)m2),

and q(i,j)= q2 =-m/(1+(n-2m-(n-1)m2) for i different from j.

Hence, Equation (1) can be rewritten,

(1bis) P=bQS+QU

which yields,

(2) VPi = cVSi +dSi + vi

where c= q1b whereas d=(n-1)bq2=ab/(1+(n-2m-(n-1)m2)