Résumé

Partant de recherches menées par Thatcher et Perrewé (2002) et Ahuja et Thatcher (2005), cette étude appro-fondit l’analyse de l’impact de variables générales et spécifiques aux technologies de l’information (TI) liées à l’environnement de travail sur les différences individuelles influençant l’utilisation des TI. Une en-quête a été conduite avec un échantillon de 1010 sala-riés en formation continue en France. Les résultats montrent que l’autonomie, la surcharge de travail qua-litative et l’appui managérial influencent significati-vement les variables individuelles situationnelles spé-cifiques aux TI. Cette étude approfondit l’examen des interactions entre des variables de l’’environnement de travail et les différences individuelles. Elle contribue à une meilleure compréhension des relations entre des variables clés dans la compréhension du processus essentiel d’adaptation mutuelle entre la TI, l’organisation, et les individus.

Mots clefs:

Efficacité personnelle avec les TI, Anxiété, Innovation personnelle, Environnement de travail, Surcharge de travail.

Abstract

Drawing on prior research of Thatcher and Perrewé (2002) and of Ahuja and Thatcher (2005), the purpose of this study is to furthering our understanding of the impacts of broad and IT-specific work environment variables on individual differences influencing IT use. A survey has been conducted with a sample of 1129 workers in professional training in France. The results show that autonomy, qualitative overload, and IT managerial support significantly impact IT situation-specific individual differences. This study furthers the examination of interactions between work environment variables and individual differences. It contributes to a better understanding of the interplay of key variables in the mutual adaptation process between IT, organiza-tions, and individuals.

Key-words:

Computer Self-Efficacy, Computer Anxiety, Personal Innovativeness, Work Environment, Work Overload.

Environment on

IT-Specific Individual

Differences: An

Empirical Study

Christophe Elie-Dit-Cosaque

Professeur Assistant

Groupe Sup de Co Montpellier

2300 Avenue des Moulins

34185 Montpellier Cedex 4

Tel : + 33 (0) 6 18 64 72 02

c.elie-dit-cosaque@supco-montpellier.fr

Jessie Pallud

Professeur Assistant

Ecole de Management Strasbourg

61, avenue de la Forêt-Noire

F-67085 Strasbourg Cedex

jessie.pallud@em-strasbourg.eu

Michel Kalika

Professeur

Directeur de l’école de Management Strasbourg

Université Robert Schuman

61, avenue de la Forêt-Noire

F-67085 Strasbourg Cedex

Tel : +33 (0) 3 90 41 42 66

michel.kalika@em-strasbourg.eu

1. Introduction

The pace of implementation and the often disruptive IT (Lyytinen and Rose 2003; Beaudry and Pinsonneault 2005) invoke a constant need of adaptation within organ-izations (Leonard-Barton 1988; Beaudry and Pinson-neault 2005). In the course of their adaptation to IT, sys-tem users make use of their resources and capabilities such as their ability to control the consequences of IT (Beaudry and Pinsonneault 2005) but are also influenced by their work environment (Ahuja and Thatcher 2005). Furthermore, users differ significantly in their interac-tions with IT depending on individual characteristics (Zmud 1979; Venkatesh 2000; Karahanna et al. 2002) and work environment variables (Ahuja and Thatcher 2005; Ahuja et al. 2007). There are thus theoretical chal-lenges posed by the understanding of how these variables impact individual usage behaviors.

There are also practical challenges associated with the understanding of such issues. Indeed, practitioners need to be constantly aware of how users interact with IT in order to design appropriate training programs (Thatcher and Perrewe 2002). As well as it is necessary for system designers to constantly ensure that systems fit user tasks (Goodhue and Thompson 1995), it is also important to acknowledge the determinants of user computer self-efficacy (CSE) or “ability to competently use technolo-gy” (Compeau and Higgins 1995, p. 189). Indeed, CSE has been found to influence how individuals use and in-teract with IT (Compeau and Higgins 1995). In the same time researchers still widely report attempts of users to work around systems (Orlikowski 2000; Boudreau and Robey 2005; Vaast and Walsham 2005). This holds even when these systems are very restrictive such as ERP sys-tems (Boudreau and Robey 2005). While these behaviors might be motivated by multiple reasons, users competent enough to use specific IT are probably more capable to use it in faithful ways. Little do we know, however, about the influence of work environment variables on CSE. Researchers indeed investigated CSE as an independent variable, studying its impacts on system usage related variables (e.g., Venkatesh 2000), or as an independent variable studying its individual-related determinants (Thatcher and Perrewe 2002). Few, however, clearly focused on the influence of work environment variable on CSE. Consequently, our research question is the fol-lowing: What are the influences of broad work environ-ment factors and IT-specific work environenviron-ment factors on CSE?

Drawing on Thatcher and Perrewe (2002), the purpose of this empirical study is offering further insights on the effects of work environment on IT-specific individual differences. This empirical study has been conducted with 1119 employees attending professional training courses in France. These individuals came from more than 200 organizations. Consequently, an additional

strength of this study is the generalizability of its findings to French corporations.

The paper is organized as follows. In the first section, we motivate the need for gaining further insights into the influences of work environment and individual differ-ences on individual reactions with IT. Then we introduce the research model and the hypotheses. The model draws on Ahuja and Thatcher (2005) and on Thatcher and Per-rewe (2002) research. Then, we present the methodology and analyses. Finally, we discuss the results and the con-tributions of this study and conclude with a future re-search agenda.

2. Theoretical Background

Better understanding user adaptation to IT is a topic of growing interest in information systems (IS) research (Leonard-Barton 1988; Beaudry and Pinsonneault 2005; Deng et al. 2007). Recent research indicates that both individual differences and work environment can influ-ence user interaction with IT (Thatcher and Perrewe 2002; Ahuja and Thatcher 2005; Beaudry and Pinson-neault 2005). Taking into account these factors separate-ly, Thatcher and Perrewé (2002) and Ahuja and Thatcher (2005) provide insightful results, respectively on individ-ual factors leading to CSE and on the influence of work environment on post adoptive behaviors. Integrating both views can offer, we believe, additional insights on these issues. Therefore, we relied on these studies to develop our research model.

The purpose of Thatcher and Perrewé (2002) was to de-velop a more comprehensive nomological net around CSE. Thus, they investigated the interplay between IT-specific individual difference (computer anxiety and CSE), situation specific individual difference (personal innovativeness with IT) and broad traits (negative affec-tivity and trait anxiety). However, although this study furthers our understanding of individual differences lead-ing to IT usage, it only addresses the individual and per-sonal level to explain user self-efficacy with the technol-ogy. Though, organizational or environmental factors are likely to play a prominent role in user efficacy with tech-nologies (Ahuja and Thatcher 2005; Deng et al. 2007). It is thus important to integrate this dimension and to study its impacts on aforementioned factors leading to IT use. Ahuja and Thatcher (2005) partly filled this gap by tak-ing into account several work environment variables to explain user trying to innovate with IT. Ahuja and Thatcher (2005) contend this latter variable is a relevant post-adoption outcome. They finally identified work overload and autonomy to be significant variable that influence trying to innovate with IT. They also showed the role played by gender in user perceptions.

Following Ahuja and Thatcher (2005), this work is an attempt to further examine the effects of work environ-ment on IT related variables. Our focus is on the effects of work environment on IT-specific individual

differ-ences, namely computer anxiety (CA) and CSE. In con-trast, Ahuja and Thatcher (2005) examined the influence of work environment on user trying to innovate with IT. We also add another work environment variable, which is IT managerial support.

3. Model and Hypotheses

This paper examines the relationship between work envi-ronment, the stable situation-specific trait of personal innovativeness with IT, and a stable broad trait, namely

CA.

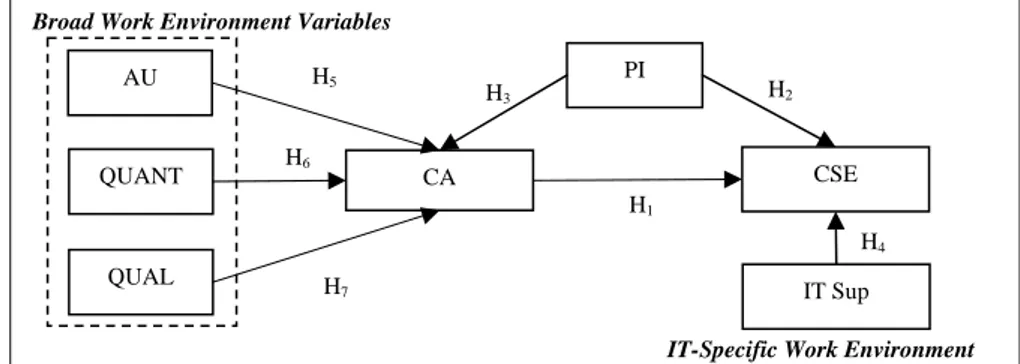

Drawing on Thatcher and Perrewé (2002), we posit CA as a direct antecedent of CSE. Personal innovativeness is posited to influence both aforementioned variables. We then hypothesize work environment variables of autono-my, quantitative and qualitative overload (Ahuja and Thatcher 2005), as having direct influence on CA. IT managerial support is posited as a direct predictor of CSE.

The research model is displayed in Figure 1

below.

It has seven hypotheses, which we introduce hereafter.Figure 1. Research Model

3.1.IT-specific Individual Differences

Through a synthesis of the literature, Zmud (1979) stressed the role of individual differences for IS success. Specifically, the researcher highlighted three categories of individual differences that are specific to the IS con-text and that play a significant role in IS use. These cate-gories are cognitive styles, personality and demograph-ic/situational variables (p. 967). Following this research, Karahanna et al. (2002) studied one type of individual differences, namely personality traits, that includes per-sonal innovativeness, written communication apprehen-sion, oral communication apprehension and CA. Kara-hanna et al. (2002) found that personality traits influence the perception of IT usefulness, namely the relative ad-vantage of decision support systems. Similarly, this re-search aims at investigating individual differences through personality traits by addressing CA and personal innovativeness with IT. CSE is added as a third individu-al difference (Thatcher and Perrewe 2002).

3.1.1. Computer Self-Efficacy (CSE)

CSE pertains to the category of dynamic individual dif-ferences (Thatcher and Perrewe 2002). CSE is defined as “a judgment of one’s capability to use a computer” (Compeau and Higgins 1995, p. 192). Compeau and Hig-gins (1995) argued that CSE has three main dimensions. The first dimension is magnitude, which reflects the ca-pability of an individual to perform complex tasks with computers. The second dimension is strength, that is, the confidence of an individual in his/her ability to perform tasks with computers. Finally, generalizability refers to the domain of activity to which CSE applies. Researchershave linked CSE to several outcome variables. For in-stance, CSE is positively related with outcome expecta-tions (Compeau and Higgins 1995), system usage (Com-peau and Higgins 1995; Venkatesh et al. 2003; Thomp-son et al. 2006), enjoyment during system usage (Com-peau and Higgins 1995) and perceived behavioral control (Thompson et al. 2006). Given that the implications of CSE for system usage it is thus important to identify its determinants.

3.1.2. Computer Anxiety (CA)

While Sun and Zhang (2006) identify CSE as a cognitive reaction to IS use, they introduce CA as an affective reac-tion to IS use. Similarly Venkatesh (2000) considers CA as an emotion in his research model. Therefore, by deal-ing with CSE and CA variables in our research, we can assess both cognitive and affective reactions linked to IT use. CA refers to an anxious state towards IT use. Usual-ly, individuals who experience CA fear using IT and can be reluctant to interact with it (Igbaria and Parasuraman 1989).

Several studies found that CA is negatively related to IT use (Coffin and MacIntyre 1999; Venkatesh 2000; Durn-dell and Haag 2002). For instance, DurnDurn-dell and Haag (2002) showed that lower levels of CA encourage higher levels of system usage, more specifically of Internet use. Other researchers such as Coffin and MacIntyre (1999) observed the relationship between CA and CSE. They investigated computer-related affective states by conduct-ing a survey with Canadian college students. They found that CA leads to lower levels of CSE. This result was confirmed in another survey by Thatcher and Perrewé H6 CA CSE QUANT IT Sup H5 H7 H3 H2 H4 H1

IT-Specific Work Environment

QUAL

AU PI

Broad Work Environment Variables

CA=Computer Anxiety, AU= Autonomy, CSE = Computer Self-Efficacy, INN = Personal Innovativeness with IT, QUAL = Qualitative Overload, QUANT = Quantitative Overload, SUP = IT Managerial Support

(2002) who found that CA was negatively related with CSE. Consequently, we hypothesize the following: Hypothesis 1: Computer anxiety negatively influences computer self-efficacy.

Furthermore, we note that the aforementioned studies were conducted in an academic setting with college stu-dents as subjects. Therefore, testing the influence of CA with a sample of managers will extend the generalizabil-ity of these results. The next individual difference this research addresses is personal innovativeness.

3.1.3. Personal Innovativeness with IT

Researchers often distinguish individuals depending on their readiness to adopt a new IT (e.g., Mahajan and Pe-terson 1978; Brancheau and Wetherbe 1990; Parthasara-thy and Bhattacherjee 1998), that is, depending on their personal innovativeness. Agarwal and Prasad (1998, p. 206) define personal innovativeness with IT (PIIT) as “the willingness to try out any new information technolo-gy”. They argue that, although innovativeness is an im-portant predictor of adoption, IS research scarcely studied this construct in relation with technology adoption. They suggest that personal innovativeness with IT has im-portant impacts on adoption decisions and innovation related outcomes. Corroborating this, Thatcher and Per-rewe (2002) linked computer innovativeness to CSE and found CA mediates this relationship. Personal innova-tiveness with IT is considered a “situation-specific stable trait” (Thatcher and Perrewe 2002, p. 385). As envisaged by Thatcher and Perrewe (2002), Yi et al. (2006, p. 417) showed that individual innovativeness is significantly related with beliefs such as usefulness, ease of use and compatibility. Thompson et al. (2006) also found a strong positive impact of PIIT on ease of use perceptions, CSE and future intentions. Furthermore, Thatcher and Perrewe (2002) found support for the impact of PIIT on CSE and on CA. Hence:Hypothesis 2: Personal innovativeness with IT positively

influences computer self-efficacy.

Thus, PIIT is related to positive reactions toward IT use (Thatcher and Perrewe 2002; Thatcher et al. 2003; Thompson et al. 2006). IT is also expected that PIIT will be negatively related with negative emotions such as CA. Thatcher and Perrewe (2002) indeed found support for this negative relationship. Hence, we posit:

Hypothesis 3: Personal innovativeness with IT negatively

influences computer anxiety.

3.2.Work Environment Variables

Recent research highlighted the significant influence of work environment on individual differences, specifically on personality traits (Westerman and Simmons 2007). Indeed, Westerman and Simmons (2007) showed that work environment was a mediator of the relationship between employee personality traits and their perfor-mance. Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that work

environment can also influence employee performance or efficacy with IT. In this research, the work environment components correspond to perceived autonomy and over-load, which were identified by Ahuja et al. (2005) as relevant factors influencing user interaction with IT. In addition to these broad work environment variables, we identify an IT specific work environment variable that can influence system user self-efficacy: IT managerial support.

3.2.1. IT Managerial Support

IT managerial support is an IT-specific work environ-ment variable. Researchers widely recognize the need for top management IT support for effective IT implementa-tion (Bashein and Markus 1994; Martinko et al. 1996). According to Bashein and Markus (1994), managerial support is, indeed, a precondition for business process reengineering success. Leonard-Barton and Deschamps (1988) found managerial support to be related to more IT use. According to these researchers, this concept is in fact related to the concept of subjective norms developed by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975). Given these evidence, Jasper-son et al. (2005) suggested that top managers should con-tinually support IT uses and good practices over time. Moreover, managerial commitment to IT change success has greater impact when it is accompanied by worker empowerment (Bashein and Markus 1994). This can be done through increased self-determination, self-efficacy, and impact (Thomas and Velthouse 1990; Spreitzer 1995). With managerial IT support, we thus expect em-ployees to have a greater sense of self-efficacy and so to be more confident in their IT use. We posit:

Hypothesis 4: IT managerial support is positively related

with computer self-efficacy.

3.2.2. Autonomy

Autonomy is related to a sense of freedom in the work-place. It refers to the practices that foster initiative and freedom in individuals’ actions (Seibert et al. 2004). Au-tonomy is also frequently defined as a component of em-powerment (Conger and Kanungo 1988; Thomas and Velthouse 1990; Spreitzer 1995; Seibert et al. 2004). In that, autonomy is similar to self-determination. Self-determination indeed “reflects autonomy over the initia-tion and continuainitia-tion of work behavior and processes” (Spreitzer 1996, p. 484). It is often related with work performance and job satisfaction. Ahuja and Thatcher (2005) found that higher levels of autonomy encouraged trying to innovate with IT. Ahuja et al. (2007) related job autonomy to higher levels of organizational commitment and lower levels of of IT road warriors exhaustion. Since autonomous individuals have greater capacity of initia-tive for making decisions about their work, we expect that autonomy will be related with lower levels of CA. Hypothesis 5: Autonomy negatively influences computer anxiety.

3.2.3. Overload

Overload is defined as “individuals’ perception that they cannot perform a task because they lack critical re-sources” (Ahuja and Thatcher 2005, p. 435). Following Sales (1970), Ahuja and Thatcher (2005) distinguished a quantitative and a qualitative dimension of overload. The quantitative dimension of overload refers to what indi-viduals cannot do because of environment limitations. The qualitative dimension of overload refers to the indi-viduals’ perceptions that their tasks require more skills and capacities in their work than they currently possess (Ahuja and Thatcher 2005). Peterson et al. (1995) con-sidered role overload as the lack of personal resources that would permit the individuals to fulfill their commit-ments, obligations, and requirements (Peterson et al. 1995). Work overload has several consequences on em-ployees such as work exhaustion or turnover. IS imple-mentation in the workplace can facilitate some work ac-tivities but, at the same time, can contribute to the inten-sification of the overall workload and increase profes-sional constraints (Metzger and Cléach 2004).

Hypothesis 6: Quantitative overload positively influences

computer anxiety

Hypothesis 7: Qualitative overload positively influences

computer anxiety

4. Methods

4.1.Research Design

We used a survey design in order to test our model. Sur-vey designs are particularly appropriate when the purpose of the research is to obtain generalizability of the findings (Pinsonneault and Kraemer 1993). Analyses have been performed with the PLS algorithm based software SmartPLS (Ringle et al. 2005). As compared with covari-ance based software, PLS places less demands and distri-butional assumptions of data (Chin 2001).

4.2.Measures

The scales were borrowed from prior research. CSE (3 items) and CA (3 items) are from Venkatesh (2000). Work environment variables, namely autonomy (3 items), quantitative (4 items) and qualitative overload (4 items), were developed by Ahuja and Thatcher (2005). Personal innovativeness is from Agarwal and Prasad (1998). Managerial support was adapted from social fac-tor items available in Thompson and Higgins (1991). All measures were reflective and were assessed with a 7 point Likert scale. The possibility of not answering a question was also given to subjects who did not feel con-cerned by the statement. All these measures were devel-oped in English. Thus, we first translated them into French and translated them back in English in order to ensure an identical meaning across countries. Details of items are given in Appendix.

4.3.Sampling

Questionnaires were given to workers after professional training courses in a large French training company1. The courses dealt with many general or specialized topics such as time management, personal organization, man-agement control, accounting, team manman-agement. Many categories of workers are represented in the sample, from top managers to clerical workers. The questionnaires were distributed randomly across training courses in a period of time of one month. Overall 1129 participants took part in the study. Of these participants, 119 have been retained from analyses because they answered “not concerned” for all the items of at least one construct. Because all constructs are reflective and their items hence interchangeable (Jarvis et al. 2003), once participants answered to at least an item, they were included in the analyses. The final sample is hence of 1010 participants (90 %).

Regarding the demographic information of our sample, 44% of the participants were men, and 56% women. 37% were from 26 to 30 years old, 50% from 36 years old to 50 years old, and 10% were more than 50 years old. The participants came from more than 200 companies. 23.3% of the participants work in organizations larger than 10000 employees, and 7.3% work in companies that have less than 500 employees. 57% of the participants were managers and 38% team managers.

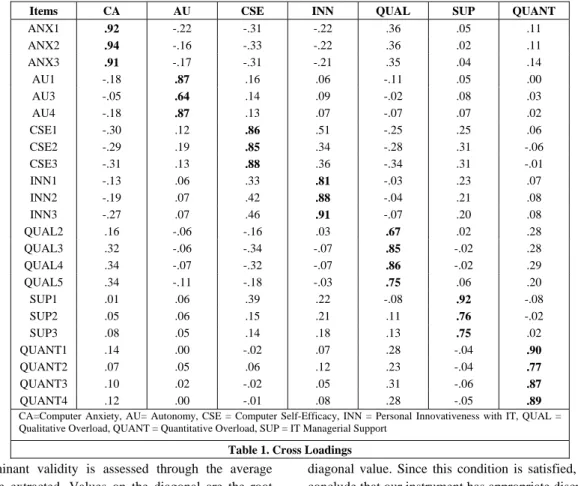

4.4.Construct Validity and Reliability

Convergent and discriminant validity are assessed by the cross loadings table and the Average Variance extracted table. The cross loadings are given in Table 1 below. The results show that all items load clearly on their intended constructs, with values greater than 0.60. CSE1 loading on INN was above the cutoff .50 value. Because it was only marginally above this value, we decided to maintain it in analyzes. Also, t-values of the outer model loadings statistics are all greater than 1.96 for items loadings on their constructs. We can thus conclude that all items load significantly on their intended construct which is evi-dence of appropriate convergent validity (Gefen et al. 2000).

1

This research has been conducted within the Observatoire

Dauphine-Cegos du e-Management, a research partnership

Items CA AU CSE INN QUAL SUP QUANT ANX1 .92 -.22 -.31 -.22 .36 .05 .11 ANX2 .94 -.16 -.33 -.22 .36 .02 .11 ANX3 .91 -.17 -.31 -.21 .35 .04 .14 AU1 -.18 .87 .16 .06 -.11 .05 .00 AU3 -.05 .64 .14 .09 -.02 .08 .03 AU4 -.18 .87 .13 .07 -.07 .07 .02 CSE1 -.30 .12 .86 .51 -.25 .25 .06 CSE2 -.29 .19 .85 .34 -.28 .31 -.06 CSE3 -.31 .13 .88 .36 -.34 .31 -.01 INN1 -.13 .06 .33 .81 -.03 .23 .07 INN2 -.19 .07 .42 .88 -.04 .21 .08 INN3 -.27 .07 .46 .91 -.07 .20 .08 QUAL2 .16 -.06 -.16 .03 .67 .02 .28 QUAL3 .32 -.06 -.34 -.07 .85 -.02 .28 QUAL4 .34 -.07 -.32 -.07 .86 -.02 .29 QUAL5 .34 -.11 -.18 -.03 .75 .06 .20 SUP1 .01 .06 .39 .22 -.08 .92 -.08 SUP2 .05 .06 .15 .21 .11 .76 -.02 SUP3 .08 .05 .14 .18 .13 .75 .02 QUANT1 .14 .00 -.02 .07 .28 -.04 .90 QUANT2 .07 .05 .06 .12 .23 -.04 .77 QUANT3 .10 .02 -.02 .05 .31 -.06 .87 QUANT4 .12 .00 -.01 .08 .28 -.05 .89

CA=Computer Anxiety, AU= Autonomy, CSE = Computer Self-Efficacy, INN = Personal Innovativeness with IT, QUAL = Qualitative Overload, QUANT = Quantitative Overload, SUP = IT Managerial Support

Table 1. Cross Loadings

Discriminant validity is assessed through the average variance extracted. Values on the diagonal are the root square of the average variance extracted for each con-struct. These values should be greater than any

off-diagonal value. Since this condition is satisfied, we can conclude that our instrument has appropriate discriminant validity. The AVE table is given in Table 2 below.

Variables CR CA 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

(1) Autonomy .84 .74 .80

(2) Computer Anxiety .95 .91 -.20 .92

(3) Computer Self-Efficacy .90 .84 .17 -.35 .87

(4) Personal Innovativeness with IT .90 .84 .08 -.23 .47 .87

(5) Qualitative Overload .87 .80 -.10 .39 -.33 -.05 .79

(6) Quantitative Overload .92 .89 .01 .13 .00 .09 .32 .86

(7) Managerial Support .85 .79 .07 .04 .33 .24 .01 -.05 .81

CR = Composite Reliability, CA = Cronbach’s Alpha

* Items on the diagonal are the square root of Average Variance Extracted (AVE). Table 2. Discriminant Validity and Reliability Finally, reliability was checked with composite reliability

(Fornell and Larcker 1981) and Cronbach’s Alphas. All values of Cronbach’s Alphas and composite reliability were well above the 0.70 generally accepted threshold (Boudreau et al. 2001). Thus, our constructs have appro-priate internal consistency.

Given the very good values overall for convergent validi-ty, discriminant validivalidi-ty, and reliabilivalidi-ty, we can thus

con-clude that our instrument has appropriate measurement properties. The step that follows is the analysis of struc-tural paths.

5. Analyses

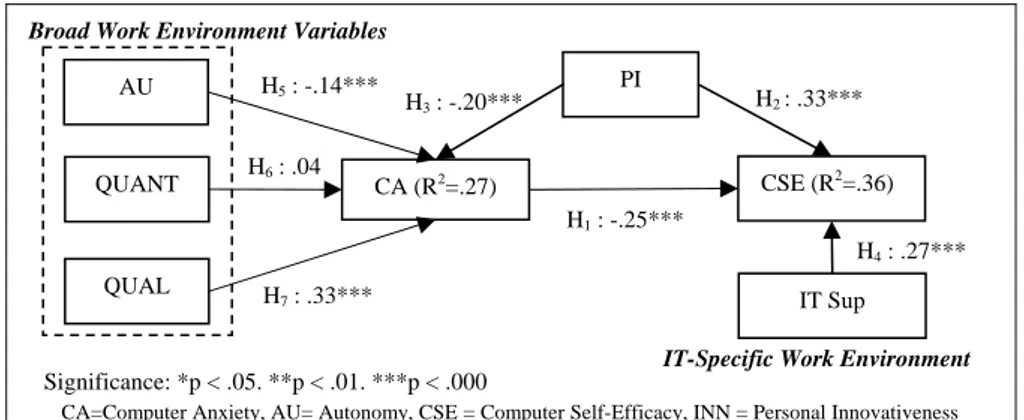

For the test of structural paths, we included gender, expe-rience with IT, and age as control variables. The overall results are summarized in Figure 2 and Table 3 below.

Figure 2. Summary of Results The variance explained for CA was R2 = .27. Like

ex-pected, we found a significant negative influence of au-tonomy on CA (Beta = -.14, p < .000). We also found a positive relationship between qualitative overload and CA (Beta = .33, p < .000). As expected also, we found a negative relationship between personal innovativeness and CA (Beta = -.20, p < .000). However, unexpectedly, we found no significant influence of quantitative over-load on CA (Beta = .04, N.S). This suggests that having too much work to perform has no influence on an indi-vidual’s CA. Age, which was posited as a control varia-ble was found to significantly influence CA (Beta = .20, p < .000), which suggests that eldest people tend to be more computer anxious than the youngest ones. Experi-ence with IT was found to be significant with a small negative impact on CA (Beta = -.06, p < .05), suggesting that the more experience individuals have, the less com-puter anxious they are likely to be. Finally, we found a

small and barely significant effect of gender (Beta = -.05, p < .05), with women less computer anxious than men. Our model explains 28 % of the variance for CSE (R2 = .36). CA was found to be a significant negative predictor of CSE (Beta = -.25, p < .000). Similarly, personal inno-vativeness was found to be a significant predictor (Beta = .-.20, p < .000) of CA. These results are consistent with prior research on the topic (Thatcher and Perrewe 2002). As well, age (Beta = -.09, p < .000), experience with IT (Beta = .07, p < .05), and gender (Beta = -.11, p < .000) were found to significantly impact CSE. This suggests the elder and the more experienced the individuals are, the more self-efficient they feel. In contrast, women feel less self efficient than men. Finally, IT support was found to significantly impact CSE, which is consistent with our expectations (Beta = .27, p < .000). The results are sum-marized in Table 3 below.

Predictor P.C. S.D. S.E. T.S. D.V. Computer Self-Efficacy (R2 = .36) Computer Anxiety -.25 .03 .03 8.84*** Innovativeness .33 .03 .03 10.35*** Support .27 .02 .02 10.85*** Age -.09 .03 .03 3.71*** Gender -.11 .03 .03 4.37*** Experience with IT .07 .03 .03 2.74** D.V. Computer Anxiety (R2 = .27) Autonomy -.14 .03 .03 5.15*** Innovativeness -.20 .03 .03 7.31*** Qualitative Overload .33 .03 .03 10.18*** Quantitative Overload .04 .03 .03 1.30 Age .20 .03 .03 7.60*** Gender -.05 .03 .03 1.98 Experience with IT -.06 .03 .03 2.45* Significance: *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .000

D.V. = Dependent Variable, P.C. = Path Coefficient, S.D. = Standard Deviation, S.E. = Standard Error, T.S. = T-Statistic

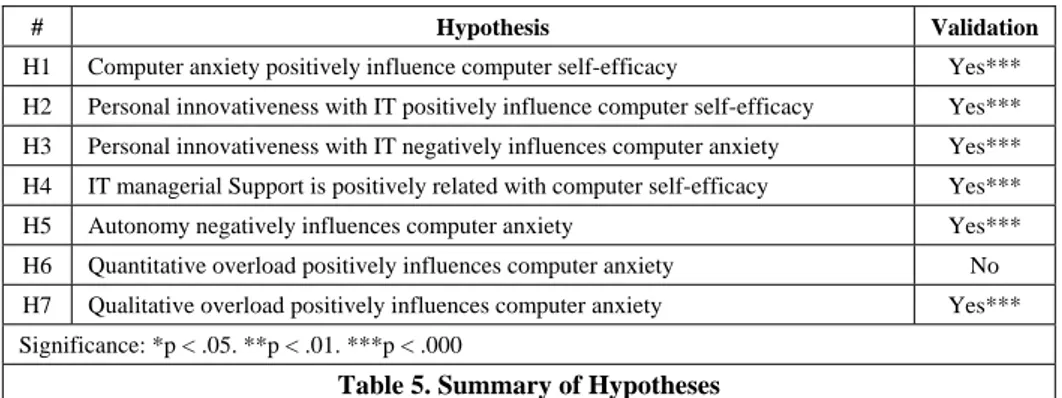

Table 3. Path Coefficients Overall, excepted for the influence of quantitative

over-load on CA, which was found to be insignificant, our hypotheses (summarized in Table 5 below) are thus well supported. H6 : .04 CA (R2=.27) CSE (R2=.36) QUANT IT Sup H5 : -.14*** H7 : .33*** H3 : -.20*** H2 : .33*** H4 : .27*** H1 : -.25***

Significance: *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .000 IT-Specific Work Environment QUAL

AU PI

Broad Work Environment Variables

CA=Computer Anxiety, AU= Autonomy, CSE = Computer Self-Efficacy, INN = Personal Innovativeness with IT, QUAL = Qualitative Overload, QUANT = Quantitative Overload, SUP = IT Managerial Support

# Hypothesis Validation

H1 Computer anxiety positively influence computer self-efficacy Yes*** H2 Personal innovativeness with IT positively influence computer self-efficacy Yes*** H3 Personal innovativeness with IT negatively influences computer anxiety Yes*** H4 IT managerial Support is positively related with computer self-efficacy Yes*** H5 Autonomy negatively influences computer anxiety Yes*** H6 Quantitative overload positively influences computer anxiety No H7 Qualitative overload positively influences computer anxiety Yes*** Significance: *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .000

Table 5. Summary of Hypotheses Three techniques were applied in order to identify

whether there was common method bias in the study. The analysis of the AVE matrix, the Harman’s single factor test, and the test consisting of “controlling for the effects of an unmeasured latent factor” (Podsakoff et al. 2003, p. 891) were performed following the procedure detailed in Liang et al. (2007). We found no evidence of common method bias following either technique.

In the section that follows, we discuss the results of this study, its limitations and its contributions.

6. Discussion

The results of this study confirm prior research that found CA perceptions to negatively impact CSE perceptions (Coffin and MacIntyre 1999; Thatcher and Perrewe 2002). Conversely, personal innovativeness with IT in-creases CSE.

In response to our research question, we can assert that both broad work environment and IT-specific work envi-ronment factors play a significant role in individual dif-ferences. Indeed, we found qualitative overload and, au-tonomy to be relevant predictors of CA. Deng et al. (2007) surveyed 153 workers in a post-implementation context and they also identified autonomy as a significant variable in the nomological net of CSE. Further, IT man-agerial support was found to be an important predictor of CSE. Unexpectedly, however, quantitative overload has not been found a significant predictor of CA. Prior re-search found quantitative overload to be negatively relat-ed to trying to innovate for women (Ahuja and Thatcher 2005), and to be positively related to work exhaustion and work-family conflict. This research suggests that quantitative overload has not direct effect on the IT spe-cific psychological state of CA.

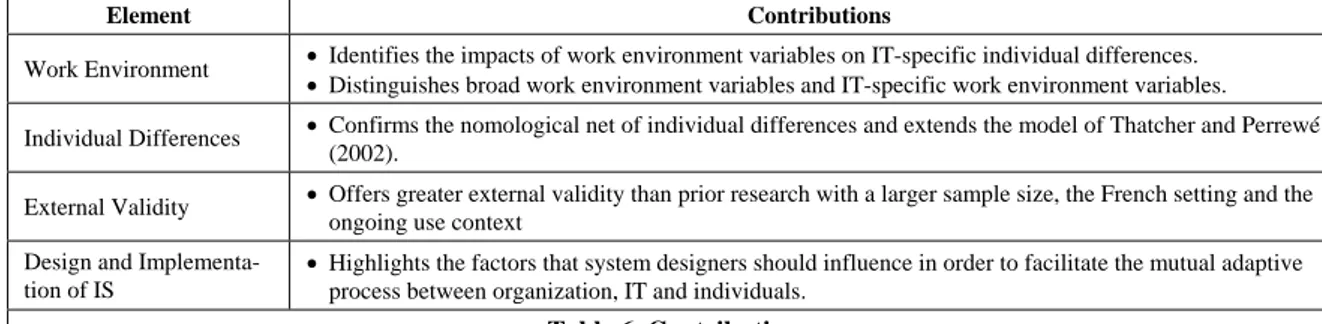

This research has several contributions for research and practice. First, we provide further insights on the influ-ence of work environment on CSE. This issue deserves attention since CSE is closely related to IS use. Indeed, CSE refers to a competent use or a rich usage of a tech-nology. Burton-Jones and Straub (2006) highlighted the fact that IS use can vary from a low structure to a deep structure. Deep structure usage corresponds to a situation in which users employ the more advanced functionalities of the IT and take advantage of its full capabilities. Fur-thermore, it seems that deep structure usage can only be

reached if users develop good ability to use computers (Compeau and Higgins 1995). Therefore, identifying the predictors of CSE enables a better understanding of IT use.

Second, this study extends prior work of Thatcher and Perrewe (2002) and of Ahuja and Thatcher (2005) with the posited influence of work environment variables on individual reactions to IT. We show that qualitative over-load and autonomy are factors influencing CA and that IT managerial support predicts CSE. In contrast, we found no influence of quantitative overload on IT-specific individual differences.

Third, this research contributes to the external validity of prior research. Both Ahuja and Thatcher (2005) and Thatcher and Perrewé (2002), conducted their investiga-tion with relatively small samples of student subjects in university settings (respectively N=235 and N=263). In spite of the strengths of such sampling method, especially with graduate students (Gordon et al. 1986), researchers suggest field research offer additional insights and better external validity (Bouchard 1976). By using a large sam-ple (N=1010) of individuals with diverse backgrounds and working in different types of organizations, our study contributes to making a step forward to generalizing prior findings to the settings of French corporations. Addition-ally, by surveying individuals about their IT use context, we also extend the generalizability of our findings to the “ongoing use context” (Deng et al. 2007). Indeed, Deng et al. (2007) noted that most IS research dealing with CSE has focused on a training context by giving little attention to variables such as autonomy, support or per-sonal innovativeness. This research deals with all the former variables and focuses on the post-implementation context, making our results generalizable to the ongoing use context. “The ongoing use context is where the com-puter actually adds value by enabling people to do work faster, better, or more creatively and, thereby, create real business value” (Deng et al. 2007, p.396). Deng et al. (2007) also explain that the ongoing use context is the step coming after training. Generally, in the ongoing use context, individuals have been using the technology for a long time and they use the technology to better perform their tasks.

Finally, the results of this study can help practitioners take into account the individual differences and work environment variables examined in this study when

de-signing courses related with adaptation to IT and IT us-age. It suggests that providing autonomy and training to people make them more confident when they interact with IT. This is also consistent with prior work on

em-powerment, contending autonomy and competence can help people become more efficient in the workplace (Conger and Kanungo 1988; Thomas and Velthouse 1990; Spreitzer 1995).

Element Contributions

Work Environment Identifies the impacts of work environment variables on IT-specific individual differences. Distinguishes broad work environment variables and IT-specific work environment variables. Individual Differences Confirms the nomological net of individual differences and extends the model of Thatcher and Perrewé

(2002).

External Validity Offers greater external validity than prior research with a larger sample size, the French setting and the ongoing use context

Design and Implementa-tion of IS

Highlights the factors that system designers should influence in order to facilitate the mutual adaptive process between organization, IT and individuals.

Table 6. Contributions This research has also limitations, which is important

to review. The main limitation of this study is, as in Thatcher and Perrewé (2002), its internal validity. In-deed, data have been gathered through self reports, with hence the predictor and criterion variable measures provided by the same person (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Participants may seek to remain consistent in their responses, and to respond according to social desirability. In order to mitigate the impacts of these potential problems, participants’ anonymity was guar-antied and they were asked to respond as honestly as possible. Participants were also given the possibility to send their responses by regular mail. Furthermore, the statistical tests performed (discussed in the analyses section) showed that common methods bias were not a concern in this study.

7. Conclusions

Building on and extending prior research (Thatcher and Perrewe 2002; Ahuja and Thatcher 2005), this study confirms and extends our understanding of the impacts of work environment variables on individual differences. This study posits broad work environment factors (autonomy, quantitative overload), and IT-specific work environment factors (IT managerial sup-port) as influencing CSE. Of the posited relationships, only quantitative overload was found to be non signifi-cant. While prior research (Thatcher and Perrewe 2002; Ahuja and Thatcher 2005) was conducted with student subjects in an only university setting, the pre-sent study has been conducted with a much larger sample of individuals from multiple backgrounds in a French setting. Practitioners might want to take the highlighted relationships into account in order to opti-mize the mutual adaptation between work environ-ments, individuals and IT.

References

Agarwal, R., and Prasad, J. (1998) "A Conceptual and Operational Definition of Personal Innovativeness in the Domain of Information Technology,"

Infor-mation Systems Research (9:2), pp 204-215.

Ahuja, M.K., Chudoba, K.M., Kacmar, C.J., McKnight, D.H., and George, J.F. (2007) "IT Road Warriors: Balancing Work-Family Conflict, Job Autonomy, and Work Overload to Mitigate Turno-ver Intentions," MIS Quarterly (31:1), pp 1-17. Ahuja, M.K., and Thatcher, J.B. (2005) "Moving

Be-yond Intentions and Toward the Theory of Trying: Effects of Work Environment and Gender on Post-Adoption Information Technology Use," MIS

Quarterly (29:3), pp 427-459.

Bashein, B.J., and Markus, M.L. (1994) "Preconditions for BPR success," Information Systems

Manage-ment (11:2), pp 7-13.

Beaudry, A., and Pinsonneault, A. (2005) "Understand-ing User Responses to Information Technology: A Coping Model of User Adaptation," MIS Quarterly (29:3), pp 493-524.

Bouchard, T.J. (1976) "Field Research Methods: Inter-viewing, Questionnaires, Participant Observation, Unobtrusive Measures," in: Handbook of Industrial

and Organizational Psychology, M.D. Dunnette

(ed.), Rand McNally, Chicago.

Boudreau, M.-C., Gefen, D., and Straub, D.W. (2001) "Validation in Information Systems Research: A State-of-the-Art Assessment," MIS Quarterly (25:1), pp 1-16.

Boudreau, M.-C., and Robey, D. (2005) "Enacting Integrated Information Technology: a Human Agency Perspective," Organization Science (16:1), pp 3-18.

Brancheau, J.C., and Wetherbe, J.C. (1990) "The Adoption of Spreadsheet Software: Testing Inno-vation Diffusion Theory in the Context of End-User Computing," Information Systems Research (1:2), pp 115-143.

Burton-Jones, A., and Straub, D.W. (2006) "Reconcep-tualizing System Usage: An Approach and Empiri-cal Test," Information Systems Research (17:3), pp 228-246.

Coffin, R.J., and MacIntyre, P.D. (1999) "Motivational Influences on Computer-Related Affective States,"

Computers in Human Behavior (15:5), pp 549-569.

Compeau, D.R., and Higgins, C.A. (1995) "Computer Self-Efficacy: Development of a Measure and Ini-tial Test," MIS Quarterly (19:2), pp 189-211. Conger, J.A., and Kanungo, R.N. (1988) "The

Empow-erment Process: Integrating Theory and Practice,"

Academy of Management Review (13:3), pp

471-482.

Deng, X., Doll, W.J., and Truong, D. (2007) "Comput-er Self-Efficacy in an Ongoing Use Context,"

Be-haviour and Information Technology (23:6), pp

395-412.

Durndell, A., and Haag, Z. (2002) "Computer Self Efficacy, Computer Anxiety, Attitudes Towards the Internet and Reported Experience with the In-ternet, by Gender, in an East European Sample,"

Computers in Human Behavior (18:5), pp 521-535.

Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (1975) "Belief, Attitude,

Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to theory and research, Reading, MA.

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. (1981) "Evaluating Struc-tural Equation Models with Unobservable Varia-bles and Measurement Error," Journal of

Market-ing Research (18:1), pp 39-50.

Gefen, D., Straub, D., and Boudreau, M. (2000) "Struc-tural Equation Modeling Techniques and Regres-sion: Guidelines for Research Practice,"

Communi-cations of Association for Information Systems

(7:7), pp 1-78.

Goodhue, D.L., and Thompson, R.L. (1995) "Task-Technology Fit and Individual Performance," MIS

Quarterly (19:2), pp 213-236.

Gordon, M.E., Slade, L.A., and Schmitt, N. (1986) "The 'Science of the Sophomore' Revisited: From Conjecture to Empiricism," Academy of

Manage-ment Review (11:1), pp 191-207.

Igbaria, M., and Parasuraman, S. (1989) "A Path Ana-lytic Study of Individual Characteristics, Computer Anxiety and Attitudes Toward Microcomputers,"

Journal of Management (15:3), pp 373-388.

Jarvis, C.B., Mackenzie, S., Podsakoff, P., Mick, D., and Bearden, W. (2003) "A critical review of con-struct indicators and measurement model misspeci-fication in marketing and consumer research,"

Journals of Consumer Research (30:2), pp

199-218.

Jasperson, J., Carter, P., and Zmud, R. (2005) "A Comprehensive Conceptualization of Post-Adoptive Behaviors Associated with Information Technology Enabled Work Systems," MIS

Quar-terly (29:3), pp 525-557.

Karahanna, E., Ahuja, M., Srite, M., and Galvin, J. (2002) "Individual differences and relative ad-vantage: the case of GSS," Decision Support

Sys-tems (32:4), pp 327-341.

Leonard-Barton, D. (1988) "Implementation as Mutual Adaptation of Technology and Organization,"

Re-search Policy (17:5), pp 251-267.

Leonard-Barton, D., and Deschamps, I. (1988) "Mana-gerial Influence in the Implementation of New Technology," Management Science (34:10), pp 1252-1265.

Liang, H., Nilesh, S., Hu, Q., and Xue, Y. (2007) "As-similation of Enterprise Systems: The Effect of In-stitutional Pressures and the Mediating Role of Top Management," MIS Quarterly (31:1), pp 59-87. Lyytinen, K., and Rose, G.M. (2003) "The Disruptive

Nature of Information Technology Innovations: the Case of Internet Computing in Systems Develop-ment Organizations," MIS Quarterly (27:4), pp 557-595.

Mahajan, V., and Peterson, R.A. (1978) "Innovation Diffusion in a Dynamic Potential Adopter Popula-tion," Management Science (24:15), pp 1589-1597. Martinko, M.J., Henry, J.W., and Zmud, R.W. (1996)

"An Attributional Explanation of Individual Re-sistance to the Introduction of Information Tech-nologies in the Workplace," Behaviour &

Infor-mation Technology (15:5), pp 313-330.

Metzger, J.-L., and Cléach, O. (2004) "Le Télétravail des Cadres : entre suractivité et apprentissage de nouvelles temporalités," Sociologie du Travail (46), pp 433-450.

Orlikowski, W.J. (2000) "Using Technology and Con-stituting Structures: A Practice Lens for Studying Technology in Organizations," Organization

Sci-ence (11:4), pp 404-428.

Parthasarathy, M., and Bhattacherjee, A. (1998) "Un-derstanding Post-Adoption Behavior in the Context of Online Services," Information Systems Research (9:4), pp 362-379.

Peterson, M.F., Smith, P.B., Akande, A., Ayestaran, S., Bochner, S., Callan, V., Nam Guk, C., Jesuino, J.C., D'Amorim, M., Francois, P.-H., Hofmann, K., Koopman, P.L., Kwok, L., Tock Keng, L., Mor-tazavi, S., Munene, J., Radford, M., Ropo, A., Sav-age, G., and Setiadi, B. (1995) "Role conflict, am-biguity, and overload: A 21-nation study,"

Acade-my of Management Journal (38:2), pp 429-452.

Pinsonneault, A., and Kraemer, K.L. (1993) "Survey Research Methodology in Management Infor-mation Systems: An Assessment," Journal of

Management Information Systems (10:2), pp

Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.-Y., and Podsakoff, N.P. (2003) "Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies," Journal

of Applied Psychology (88:5), pp 879-903.

Ringle, C.M., Wende, S., and Will, A. "Smart PLS," U.o. Hamburg (ed.), University of Hamburg, , Hamburg, Germany, 2005.

Sales, S.M. (1970) "Some Effects of Role Overload and Role Underload," Organizational Behavior

and Human Performance (5:6), pp 592-608.

Seibert, S.E., Silver, S.R., and Randolph, W.A. (2004) "Taking Empowerment to the Next Level: A Mul-tiple-Level Model of Empowerment, Performance, and Satisfaction," Academy of Management

Jour-nal (47:3), pp 332-349.

Spreitzer, G.M. (1995) "Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation," Academy of Management Journal (38:5), pp 1442-1465.

Spreitzer, G.M. (1996) "Social Structural Characteris-tics of Psychological Empowerment," Academy of

Management Journal (39:2), pp 483-504.

Sun, H., and Zhang, P. (2006) "The Role of Affect in IS Research: A Critical Survey and a Research Model," in: Human-Computer Interaction and

Management Information Systems - Foundations (1), P. Zhang and D. Galletta (eds.), M.E. Sharpe,

Inc., Armonk, NY.

Thatcher, J.B., and Perrewe, P.L. (2002) "An empirical Examination of Individual Traits as Antecedents to Computer Anxiety and Computer Self-Efficacy,"

MIS Quarterly (26:4), pp 381-396.

Thatcher, J.B., Srite, M., Stepina, L.P., and Liu, Y. (2003) "Culture, Overload and Personal Innova-tiveness with Information Technology: Extending

the Nomological Net," Journal of Computer

Infor-mation Systems (44:1), pp 74-81.

Thomas, K.W., and Velthouse, B.A. (1990) "Cognitive Elements of Empowerment," Academy of

Man-agement Review (15:4), pp 666-681.

Thompson, R., Compeau, D., and Higgins, C. (2006) "Intentions to Use Information Technologies: An Integrative Model," Journal of Organizational &

End User Computing (18:3), pp 25-46.

Thompson, R.L., and Higgins, C.A. (1991) "Personal Computing: Toward a Conceptual Model of Utili-zation," MIS Quarterly (15:1), pp 125-143. Vaast, E., and Walsham, G. (2005) "Representations

and Actions: the Transformation of Work Practices with IT Use," Information and Organization (15:1), pp 65-89.

Venkatesh, V. (2000) "Determinants of Perceived Ease of Use: Integrating Control, Intrinsic Motivation, and Emotion into the Technology Acceptance Model," Information Systems Research (11:4), pp 342-365.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M.G., Davis, G.B., and Davis, F.D. (2003) "User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View," MIS

Quar-terly (27:3), pp 425-478.

Westerman, J.W., and Simmons, B.L. (2007) "The Effects of Work Environment on the Personality-Performance Relationship: An Exploratory Study,"

Journal of Managerial Issues (19:2), pp 288-305.

Yi, M.Y., Fiedler, K.D., and Park, J.S. (2006) "Under-standing the Role of Individual Innovativeness in the Acceptance of IT-Based Innovations: Com-parative Analyses of Models and Measures,"

Deci-sion Sciences (37:3), pp 393-426.

Zmud, R.W. (1979) "Individual Differences and MIS Success: A review of the Empirical Literature,"