© Angela Eve Marsh, 2019

Thresholds

Mémoire

Angela Eve Marsh

Maîtrise en arts visuels - avec mémoire

Maître ès arts (M.A.)

Thresholds

Thèse

Angela Eve Marsh

Sous la direction de:

RÉSUMÉ:

À travers une discussion des cinq principaux domaines théoriques qui influencent mon travail artistique; la biophilie, l’écoféminisme, « foraging » (la récupération), la non-dualité et l’espace sacré, j'explore les relations synergiques entre mes réflexions socioécologiques et politiques et ma pratique artistique. Je m'intéresse aux intersections entre l'activisme et l'art, l'engagement et la transformation, et l'idée que l'art peut être vu comme une «sculpture sociale» pour emprunter à Beuys. À la recherche constante des réalités alternatives des forces polarisantes qui dominent notre (ma) vision du monde contemporain et en critiquant la division sociétale de culture|nature, mon texte raconte la connectivité entre mes projets artistiques et mes recherches théoriques, définissant enfin la relation entre les deux comme fondamentale pour mon processus de création. Le concept de seuil est primordial, proposé comme lieu de rencontre ou jonction des mondes binaires; l'intime et le public, le profane et le sacré, la culture et la nature.

ABSTRACT:

Through a discussion of the five main theoretical domains that influence my art-making; biophilia, ecofeminism, foraging (recuperation), non-duality and sacred space, I explore the synergistic relations between my socio-ecological-political reflections and my art practice. I am interested in the intersections between activism and art, engagement and transformation, and the idea that art can be seen as a “social sculpture” to borrow from Beuys. Continually seeking alternative realities from the polarizing forces that dominate our (my) contemporary world-view and questioning the culture|nature divide, my text chronicles the connectivity between my art projects and my theoretical research, finally understanding the relationship between the two as fundamental to my creative process. The concept of the threshold is paramount, proposed as a meeting place or juncture between binary worlds; the intimate and the public, the secular and the sacred, culture and nature.

TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DE MATIÈRES:

RÉSUMÉ: ... III ABSTRACT: ... IV LISTE DES FIGURES/TABLE OF ILLUSTRATIONS: ... VI REMERCIMENTS ... IX

INTRODUCTION ... 1

CHAPTER 1: BIOPHILIA ... 7

LANDSCHAFT, LANDSCAPE, CORNER ... 12

MICHAEL LANDY, NOURISHMENT ... 14

BIOPHILIC DRAWINGS & THE FRAGMENT ... 15

CHAPTER 2: ECOFEMINISM ... 21 DAPHNE AND APOLLO ... 22 THE FEMALE BODY AND THE CHALLENGING OF DUALITIES ... 27 CHAPTER 3: FORAGING ... 31 LA PRÉSERVATION ... 35 DON’T TOUCH THE LEAVES ... 37 CHAPTER 4: NON-DUALITY ... 38 RADICAL NON-DUALISM AND AN ECOLOGICAL POSTMODERNISM ... 39 LA FRICHE ... 40

CHAPTER 5: SACRED SPACE ... 47

THE THRESHOLD ... 47

STIMMUNG ... 49

LA COURTEPOINTE ... 52

CONCLUSION ... 55

LISTE DES FIGURES/TABLE OF ILLUSTRATIONS:

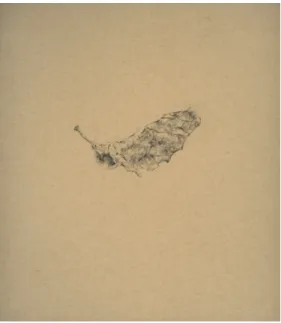

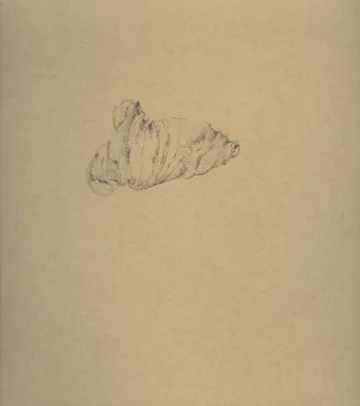

Fig. i: Angela Eve Marsh, Dessin Biophilique #11, 2017, graphite on recycled paper 5

Fig. 1.1 Angela Eve Marsh, Dessin Biophilique #23, 2018, graphite on recycled paper 7

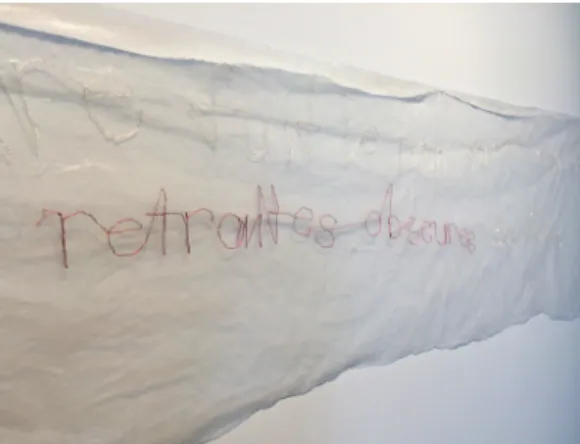

Fig 1.2 Angela Eve Marsh, Retraites obscures, 2017, embroidery thread and plastic 8

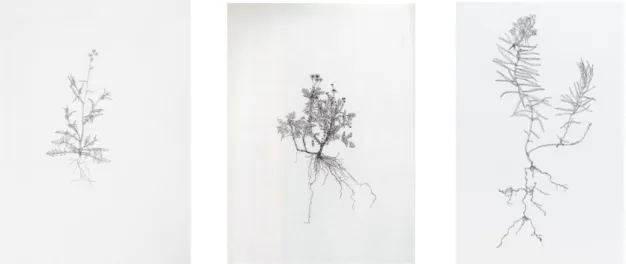

Fig 1.3 Images from Michael Landy’s project Nourishment, etchings on paper, 2003 14

Fig. 1.4 Angela Eve Marsh, Dessin Biophilique #34, 2018, graphite on recycled paper 16

Fig. 1.5 Angela Eve Marsh, Dessin Biophilique #34, 2018, graphite on recycled paper 17

Fig. 1.6 Angela Eve Marsh, Dessin Biophilique #8, 2016, graphite on recycled paper 18

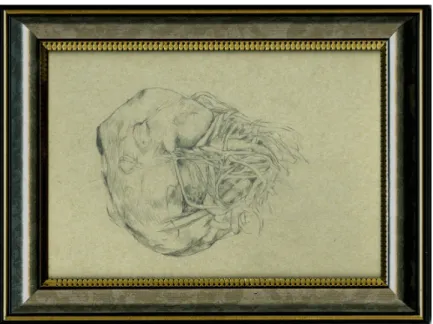

Fig. 1.7 Angela Eve Marsh, Biophilia framed #2, 2018, recuperated frame, graphite

on recycled paper 20

Fig. 1.8 Angela Eve Marsh, Biophilia framed #4, 2018, recuperated frame, graphite

on recycled paper 20

Fig. 2.1 Angela Eve Marsh, Citation of Alice Fulton, 2017, embroidery on chip bag 22

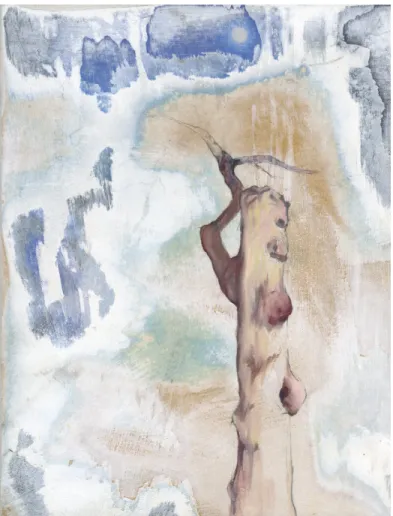

Fig. 2.2 Angela Eve Marsh, Daphne #3, 2012, oil paint on recuperated mdf board 23

Fig. 2.3 Angela Eve Marsh, Citation Joanna Macy, 2017, embroidery thread on chip bag 24

Fig. 2.4 Angela Eve Marsh, Daphne #11, 2017, oil paint on recuperated mdf 25

Fig. 2.6 Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of Daphne et Apollon

Bibliothèque St. Jean Baptiste, Québec, 2017 29

Fib 2.7 Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of project La Friche, 2017

bubble wrap, plant fragments, thread 30

Fig 3.1 Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of project Don’t touch the leaves 2017, cut chip bags and leaves 31

Fig. 3.2 Angela Eve Marsh, Daphne #16, 2017, oil paint on recuperated mdf 32

Fig 3.3 Myriam Dion, http://www.artnau.com/2013/09/myriam-dion/ 33

Fig 3.4 Giorgia Volpe, documentation of project Point de rencontre, 2016,

www.giorgiavolpe.net 34

Fig. 3.5 Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of installative project

La Preservation, sewn plastic and natural found objects, 2017 35

Fig. 3.6 Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of installative project

La Preservation, sewn plastic and natural found objects, 2017 36

Fig 3.7 Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of Reclaiming exhibition, 2017 37

Fig 4.2 Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of project La Friche, 2018, bubble wrap, natural fragments, thread 41

Fig 4.3 Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of project La Friche, 2018,

bubble wrap, natural fragments, thread 44

Fig 4.4 Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of project La Friche, 2018,

bubble wrap, natural fragments, thread. Photo: Jérôme Bourque 46

Fig 5.1 Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of La Courtepointe, recuperated plastic and thread, 2018. Photo credit: Alexis Belavance 51

Fig 5.2 Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of La Courtepointe, recuperated plastic and thread, 2018. Photo credit: Alexis Belavance 54

Fig 6.1 Angela Eve Marsh, Biophilia framed, graphite on paper in recuperated

frame, 2018 58

REMERCIMENTS

I would like to thank my director of research, Jocelyn Robert, for his brilliant way of seeing and understanding the world and the art that we make, as well as for his open mind and generous guidance.

Alexandre David, Marcel Jean and Joëlle Tremblay also deserve my gratitude for their insights and for the sharing of their time and knowledge.

Carol Bigwood from York University, for her inspiring words that greatly nourished my reflection.

I thank my children, Ernest and Madeleine, for still being true and wild. Justin, for always seeking to understand.

My mother. My sister. My mother-in-law. Thank-you.

And of course to her, Nature, the mother of us all, for waiting patiently and lovingly despite our continued forgetting.

Je voudrais remercier mon directeur de recherche, Jocelyn Robert, pour sa manière brillante de voir et de comprendre le monde et l'art que nous fabriquons, ainsi que pour son ouverture d'esprit et ses conseils généreux.

Alexandre David, Marcel Jean et Joëlle Tremblay méritent également ma gratitude pour leurs idées et pour le partage de leur temps et de leurs connaissances.

Carol Bigwood d’Université York, pour ses mots inspirants qui ont beaucoup nourris mes réflexions.

Je remercie mes enfants, Ernest et Madeleine, des êtres toujours authentiques et

wild.

Justin, pour continuer de chercher à comprendre. Ma mère. Ma sœur. Ma belle-mère. Merci.

Et bien sûr, elle, La Nature, la mère à toutes et à tous, qui continue d'attendre patiemment et amoureusement malgré notre oubli constant.

INTRODUCTION

Over the course of the research and reflection that has comprised my master’s studies in visual arts, I have come to the realisation that for me, art-making is the residue and result of a confrontation of the dualities that conform my personal and societal perceptions; a process that is born from a place of perpetual friction. In my art practice, I am trying to find a way of making the polarities talk, of cohabiting inspiration with discomfort, serenity with indignation. As Ai Wei Wei said in a recent interview, “I am trying to cope with my learning”. I feel as though my art practice is born from a place of great anguish and vulnerability confronted with the realities and tragedies of our contemporary world, which no longer remain external to my personal life but that infiltrate and become intimate narratives that form my perceptions and experiences.

The fragility of our present ecological, social and spiritual balance is assumed in my practice, and in many ways determines the aesthetic of what I create.

My work feels like a birth of sorts, a cohabitation that seeks to self-realize outside of the dichotomies of a separated culture|nature system that informs and conditions my ways of understanding the world. I am looking for a 3e voie or 3rd path, another reality beyond the

dualities that both trouble and engage me. Moving away from Cartesian-inspired grids towards vertiginous ecosystemic complexities, I am fascinated by the wild, the micro fragment in its relation to the monad, the liberty that exists in the unquantifiable.

I undertook my master’s degree questioning the relationship between my socio-political activism and my interior, intimate world as joint instigators for my art-making. Despite the fact that they both play a crucial role in my creative production, I initially felt them to be antagonistic and at odds with one another, as if my artistic work was like the blister that forms around the sore of my discomfort. I now fully embrace this, realizing that for me, this “contamination”, this messy, indiscriminate crossover between the issues and the self is essential in my art practice, constituting the very basis from which my creative impulse is born.

The modernist notions of individuality and materiality as central components of art-making seemed and still seem irrelevant to my practice. I have an urge to contaminate (in a positive sense) the untouchableness of it all in my search for pragmatic meaning, in response to my need to confront tensions and to seek resolution(s). To upset the “Emperor’s new clothes” phenomenon of the art world with questions, concerns or emotional responses.

Rather than creating fixed art objects that are statically preserved and therefore easily packaged for our consumerist culture, the realities of change and entropy inspire me to rework and reintegrate found materials and completed artworks into new installations or artistic experiences, where renewal and demise become determinate forces and an organic flux prevails.

When I look back on my journey over the last two years, pluralist centres of critical thinking emerge. So I have decided to organize this text around these ideas, proposed as the multiple nuclei of my creative engagement: biophilia, ecofeminism, foraging, non-duality, and sacred space.

Through my work, these fundamental ideas appear and reappear and the related artistic experimentations result in diverse realisations (aesthetic, philosophical and ethical), with each project enabling me to take apart or understand a different question or theoretical interrogation in a new way.

And so, like a threshold of sorts, my art practice is situated at the meeting place between the intimate and beyond, the open and concealed, the serene and troubled, seeking a non-dual way of being amidst the dichotomies that organize my felt world.

I am trying to cope with my learning.

Ai Wei Wei Interview CBC radio, June 2018

I can’t help but pull the earth around me, to make my bed.

From the song “Ship to wreck” (2015) Florence and the Machine

My intention is not to improve on nature but to know it – not as a spectator but as a participant1.

Andy Goldsworthy

These words are written for those of us whose language is not heard, whose words have been stolen or erased, those robbed of language, who are called voiceless or mute, even the earthworms, even the shellfish and the sponges, for those of us who speak our own language…2

Susan Griffin

Fig. i: Angela Eve Marsh, Dessin Biophilique #11, 2017, graphite on recycled paper

Walking in the woods with my family at 8 or 9 years old, I am nourished by the rich diversity of life and the quiet, sacred silence of the place. Our walks are almost ritualistic, crossing a large field of wildflowers and sumac bushes to reach the opening of the "magic forest", where our playful race slows into small, tempered steps. At the entrance to the forest our awareness seems to awaken, seeking communion with all the mysteries of the wild that are harboured within.

From this young age, I begin to understand the precariousness of our natural spaces, of the human/nature balance. My mother would warn me often, "This may not be here when you grow up”. Leaving the forest, I look behind me and imagine a halo of light around the landscape, a protective shield to ward off the blind hand of human "development".

Moving to the city at the end of my teenage years, I miss the bucolic environment of my childhood. In a gesture of reconciliation, I let the little tufts of grass behind my rented, rundown Victorian go wild and cultivate vegetable gardens with my room-mate that always left place for the untamed. I feel an incredible relief watching the weeds grow through the cracks in the roadway, signs of her (nature). And so began my almost obsessive observation and adoration of urban trees, towering over the cut grass and concrete landscapes, perpetually witnessing all our hasty debates. Through their wise presence, I realize my own fleetingness, my distraction, my impermanence. The trees whisper to me: "Stay alive, rooted and real!"3

CHAPTER 1: Biophilia

Fig. 1.1: Angela Eve Marsh, Dessin Biophilique #23, 2018, graphite on recycled paper

I'm here again, still silent, absorbed in my drawing, in total connection with this little piece of nature. In this sacred space of creation, the sacred space of my studio, my absolute admiration for this fragment of the natural world is transmitted in my tentative lines that try to capture its resonance of life. I embroider or I sew, taking pleasure in this validation of the manual, this reclaiming of time, thinking of the long line of women who did it before and who are doing it with me. I create from the plastic that I recover, this dominating material that troubles me so much, embroidering words of resistance, words to strengthen and question, in the flagrant colors of turquoise blue and scarlet red. On plastic, so banal and yet so invasive, that seems to seduce us more brilliantly than spring flowers or the song of birds. 4

Fig 1.2: Angela Eve Marsh, Retraites obscures, 2017, embroidery thread and plastic

In trying to articulate and comprehend the motivations and theoretical underpinnings of my artistic practice, I identify the notions of biophilia and pillars of ecofeminist theory as fundamental to my creative inspiration as well as symbiotic and intertwined with my world vision. My work is an intimate dialogue between my experience, perception and environment (natural and cultural), reflecting pressing socio-political questions that are treated and filtered through my lenses of engaged citizen, mother and female artist. My artistic research explores my relationship with nature, both in an intimate sense and in a broader sociological context, rooted in my childhood experiences where the beauty of growing up in a natural environment was always a little darkened by my awareness of its precarity. Interested in the evidences of nature that survive amidst the challenges of contemporary urbanity, I am actively seeking a sort of reconciliation between the perceived dualities of nature|culture and the tragic Cartesian separation of the human from the wild, the latter by extension associated with the feminine, the intuitive, the emotional and the bodily, which will be further explored in my analysis of ecofeminist thought in the next chapter.

What it is exactly that binds us so closely to living things? The biologist will tell you that life is the self-replication of giant molecules from lesser chemical fragments, resulting in the assembly of complex organic structures, the transfer of large amounts of molecular information, ingestion, growth, movement of an outwardly purposeful nature, and the proliferation of closely similar organisms. The poet-in-biologist will add that life is an exceedingly improbable state, metastable, open to other systems, thus ephemeral – and worth any price to keep5.

5Edward O. Wilson, Biophilia (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: Harvard University Press,

A few years ago, I came across a book entitled Biophilia, the title referring a notion defined by its author, the biologist Edward O. Wilson as "the urge to affiliate with other forms of life"6.

A decade earlier Eric Fromm had described biophilia in a more general way as “the passionate love of life and of all that is alive”7. However, this is not a recent concept. Indeed, it describes

the living link between humanity and nature that was suppressed by religious struggles (against animism and indigenous belief systems symbiotic to nature) and economic revolutions (the replacement of local sustainable subsistence systems by globalized, mercantile capitalist systems in which work was no longer intrinsically dependent upon relationship and stewardship of the earth). « Biophilia or something close to it was woven throughout the myths, religions and mindset of early humankind, which saw itself as participating with nature »8. According to Wilson and others (Pyle, Orr, Kahn), biophilia, the need to be

connected to the natural world, is primordial for the very survival of humanity, without which the health and wellbeing of human (and other) species are in peril.

Many individuals and societies are no longer connected to the more-than-human world in such a way as to ensure a sustainable future… As such connection has diminished, environmental challenges have multiplied and influences for estrangement intensified. Today, as the virtual finds its apotheosis at the expense of the real, the separation has progressed to a point where reattachment may be impossible, and long-term survival of human culture is not at all a forgone conclusion. 9

Soon after discovering writings on this notion of biophilia, I came across a study that made me begin to think about making art projects that are biophilic in reflection. It was an analysis of Disney films over a period of 70 years, the objective being to understand the changing place of nature in our collective imagination. The study shows that for 70 years, the duration of the scenes that show images of nature and biodiversity has greatly diminished, which is linked to the hypothesis of a great societal disconnect to nature (echoing the diagnostic of Pyle, Orr, Wilson and others):

6 Wilson, Edward O., Biophilia (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: Harvard University Press, 1984), p. 85

7 Fromm, quoted in Orr, David W., Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect, (Washington: Island Press, 2004): 187

8 Orr, David W., Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect, (Washington: Island Press, 2004): 188

…Dans nos sociétés occidentales, nous perdons peu à peu le contact avec notre environnement naturel proche, par nos modes de vie de plus en plus urbains, mais aussi par l’adhésion au paradigme dominant qui considère que le progrès technique permet de nous affranchir du monde naturel. La conséquence prédite de cette déconnexion est que, la nature faisant de moins en moins partie de leur construction identitaire (surtout en tant qu’enfant), nos concitoyens sont de moins en moins en demande de la nature, ce qui permet aux politiques et autres décideurs de se sentir de moins en moins concernés. Selon ces hypothèses, nous sommes entrés dans un cercle vicieux qui participe à la crise de la protection de la nature et de l’environnement en général. 10

The conclusion of this study troubled me as it confirmed my observations and impressions of an increasing general disconnection, exacerbated by our hygienic, controlled, urban and sub-urban ways of life that function through a complex of artificial infrastructures instead of organic relationships. It also triggered the beginning of my reflections on this idea of an

ecological illiteracy11 as proposed by Pyle, "a generational environmental amnesia"12 and the idea

of a collective imagination that could be nurtured or compromised according to our lived experience.

Marc Augé discusses the endemic of the “non-lieu” or non-place in our contemporary society; describing the zones created by highways, airports, generic shopping centres and strip malls that occupy and remodel the urban and sub-urban landscapes13. I see the non-lieu as a

corporately-defined space, the serial chain restaurants, hotels and stores where anonymity and conformity are guaranteed, as well as a “safe”, predetermined experience, with corporate branding or identity replacing the local, territorial or cultural ones (thinking of the Starbucks I visited in Kyoto that was almost identical to one in Toronto or Quebec). Most important to my discussion of biophilia, according to Augé these non-lieux are antagonistic to intimacy and

10Anne-Caroline Prévot, “Les représentatons de la nature se simplifent-elles depuis 70 ans?” Regards, Société Française d’Écologie, n 56 (2004). accessed August 1, 2018, https://www.sfecologie.org/regard/r56-a-c-prevot-disney

Translation: "... in our western societies, we are gradually losing touch with our natural environment, our increasingly urban lifestyles and by adhering to the dominant paradigm that considers that technical progress makes it possible for us to emancipate ourselves of the natural world. The predicted consequence of this disconnection is that, as nature becomes less and less part of their identity construction (especially as a child), our fellow citizens are less and less in demand of nature, allowing policy and other decision-makers to feel less and less concerned. According to these hypotheses, we have entered a vicious circle that contributes to the crisis of the protection of nature and the environment in general”

11 R. M. Pyle, “Nature Matrix: reconnecting people with nature” (Onyx, 37, 2003): 206 12 Prévot, “Les représentatons de la nature se simplifent-elles depuis 70 ans?”

connection, to relations between individuals, between self and the other as well as the self and place (contrary to the “lieu”, where the anthropological imprint or history is alive and present). “Les lieux anthropologiques créent du social organique, les non-lieux créent de la contractualité solitaire”14, "… l’espace du non-lieu ne crée ni identité singulière, ni relation, mais solitude et

similitude”15. Although Augé doesn’t discuss the role of nature in his conception of the lieu,

and even includes public parks as non-lieu, he is tackling this question of the loss of connection and community through the increasing conformity of place into non-place. The highways, strip malls and box stores surrounded by acres of paved parking lot transform the previously biophilic places, where nature was permitted to be, into the biophobic zones, where nature is controlled and any green we see is strictly limited to manicured gardens and lollipop trees. In these public spaces, starved of biophilic relation, anonymity and conformism reign. But situated outside this binary opposition, a contamination can exist, best expressed in the archetype of the weed that breaks through the paved lot, which I explore in my most recent project, La Friche (see in-depth discussion in Chapter 4: Non-duality).

Since the biophobic "non-places," occupy more and more of our landscapes, it is in a conscious socio-political gesture that I hope to construct my art practice around biophilic interests and principals. However, I am certainly not the first or the only artist to be interested in this merging of experience and politics with art and nature. Joseph Beuys, at Documenta 7 in 1982, planted 7,000 oak trees with the aim of making a “social sculpture”, a work that activated the public sphere in order to transform society and to "converge decentering projects of both the artist and the human being"16. In the contemporary art world, there are many

artists who work with living plants or animals, to question the human / nature dichotomy and "decenter the human in this eminently anthropocentric era” 17. Weintraub discusses the

practices of 42 artists in her book "Eco Art, in pursuit of a sustainable planet"18 like Eduardo

Kac's "biotope" paintings. Kac "paints" with living microorganisms that are related to the conditions of their environment, such as temperature, or even the spectators’ sneezing (where

14 Ibid, 119

15 Ibid, 130. Translation: “Anthropological places create a social organic, non-places create solitary contractuality ... the space of non-place creates neither singular identity nor relation, but solitude and similarity.”

16Amanda White, “Engaging with Vegetable Others – Entrer en relation avec l’Autre vegetal” (Esse, no. 87

(Printemps-été 2016): 21 17 Ibid, p. 20

18Linda Weintraub, “To Life! Eco Art in Pursuit of a Sustainable Planet”(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012)

new microbes colonize the biotope). I am very interested in this manoeuvre to decenter the artist in the creation of the artwork, where the work becomes the result of collective exchanges, moving away from individualist-driven practices into eco-systematic ones.

Landschaft, landscape, Corner

It is interesting that the word landscape first appeared in the French language at the end of the 16th century, only a hundred years before the time of Descartes and the Enlightenment. According to Rousseau, what is natural in man is his progressive withdrawal from nature, his gradual removal from the "primitive state"19. However, if we look at medieval depictions of

the natural world, as in the Book of Hours manuscripts, the landscape is portrayed as a working environment, ruled by the seasonal cycles of nature in which humans were also subjects. With the emergence of the Dutch landscape paintings of the 17th century, we begin

to see a clear separation of the human from his/her environment; a picturesque, mastered view of a tamed wilderness that became the iconic landscape image, a materialization of the divisive Cartesian world-view of the controller and the controlled.

Landscape architect and theorist James Corner is interested in the distinction between landskip (landscape as artifice, pictorial and visual) and landschaft (landscape as occupied environment whose effects and meaning accumulate through tactility, use and commitment over time). According to Corner landskip is a “pictured, dead event”, a deeply aestheticized experience far from the “ills of contemporary society” where the viewer is allowed, for the time being, to forget and escape present and future difficulties, promoting a nostalgia for the past in an “entertaining” experience (rather than a productive, useful or participative one)20. In this

experience the landscape becomes an “aesthetic object of attention” which is decontextualized from present reality21. By digging a little deeper into its meaning, we find that the concept of

landschaft chronologically preceded that of landskip, where the land was experienced as “the environment of a working community”, ecosystematic and diverse rather than mastered and

19 Nature contre culture, http://www.implications-philosophiques.org/litterature/les-animaux-denatures-vercors/nature-contre-culture/

20 James Corner (dir.), Recovering Landscape. Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture (New York: Princeton

Architectural Press, 1999): 156

homogenous. Landschaft describes an intimate relationship with the environment (both built and natural) that integrates occupation, activity and space. Corner explains:

Whereas the scenery of landschaft may be picturable (that is, to the degree that scenery is a valid or knowable concept in the deeply habituated landschaft), its deeper, existential aspects circle more socially cognitive, eidetic22 processes.

Spatial, material, and ambient characteristics are still here, but their essence is not necessarily that of Cartesian objecthood; they are present in sometimes foggy and multiplicitous ways, structured but not immediately visible – structured, in fact, more through use and habit in time than through any prior schematization. 23

Although Corner was principally critiquing current trends in landscape architecture through his discourse on landskip and landschaft, I find it extremely pertinent in this discussion on our ways of representing nature, and how our relationship with our environment can determine our ways of producing and consuming the images that represent this reality. Anne Cauquelin has critiqued our tendency to associate landscape with nature, stating that landscape is a construction, an analogue of nature. Rather than bringing humanity closer to nature, she argues that our landscape representations have served to further separate and control our experience, where “…the ‘landscape-system’ seems to serve as a barrier erected against a lack of culture or barbarism, against unkempt and dangerous spaces. It acts like the “No Trespassing” signs hung on the gates of large estates. It keeps out the untamed and draws a circle of good behaviour and refined manners.”24

And so, how do we reconceive our representations of nature?

22While a picture, according to Corner, would be a purely retinal impression, an eidetic image, as we have just

explored, would have sensory, cognitive and metaphorical complexity.

23James Corner (dir.), Recovering Landscape. Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture (New York: Princeton

Architectural Press, 1999): 154

24Nathalie Desmet, “The Landscape, a Counternature: An Interview with Anne Cauquelin” (Esse, vol. 88, Fall

Michael Landy, Nourishment

Fig 1.3: Images from Michael Landy’s project Nourishment, etchings on paper, 2003

In his project Nourishment (2003) Michael Landy made a series of etchings of wild plants (“street flowers” as he calls them) that he found in the forgotten corners of the city of London. The images are meticulously rendered, in a portrait style where the unique individuality of each plant is accentuated. In his project, Landy was interested in challenging hierarchies; those between humans and nature, but also those between social stratifications, with the weed acting as a metaphor for the popular classes, "call (ing) attention to the at once desolate and frantic beauty of things and places that we have, perhaps, been programmed to ignore” 25. The resonance of his images transcends their surface beauty; they work on a level

that goes beyond our traditional conceptions and depictions of nature in the picturesque sense, touching on the realm botanical drawing while working on a deeper, significative level.

It becomes clear, then, that while the etchings stick very closely to what could be seen, the depicted weeds act metaphorically, standing in for the urban underclass - similarly mobile, mongrel and diasporic - and also the subject of prolonged neglect and spasmodic measures of control, or weeding. In what Landy says in an

25Dickerson, Phoebe, “Edgelands : Prints by George Shaw and Michael Landy”, This is tomorrow contemporary art

magazine, (16 July 2012), accessed August 1, 2018,

idealization of weeds, their survival, spread and fertility take on a political complexion. 26

Landy, affiliated with Damien Hirst’s group YBA (Young British Artists), is best known for his colossal project Breakdown (2001), where in a critique of our consumerist society, Landy meticulously catalogued and destroyed all of his 7,227 personal possessions (including his car) over the course of a two-week public exhibition that took the form of a reverse assembly line with 10 workers. After this project (which rendered him possession-less and bankrupt), Landy took a year off of art, then returned with Nourishment, which continued his socio-political questioning but from a different angle. Through the simple, detailed, almost meditative images of weeds, we arrive at a different sort of experience that leaves the confines of an over-aestheticized, pictorial depiction of nature, moving towards the creation of a multi-layered, multiple-meaning image. It is interesting to note that Landy entered into a relationship with these plants that went beyond the simple drawing of them. He brought them back to his studio and cared for them for months, giving them water, light and nutrients in a continual observation of their development and wellbeing. While he engaged to take care of them, the plants in turn "nourished" Landy by offering him, through this project, a creative and financial source of renewal after the nihilistic Breakdown.

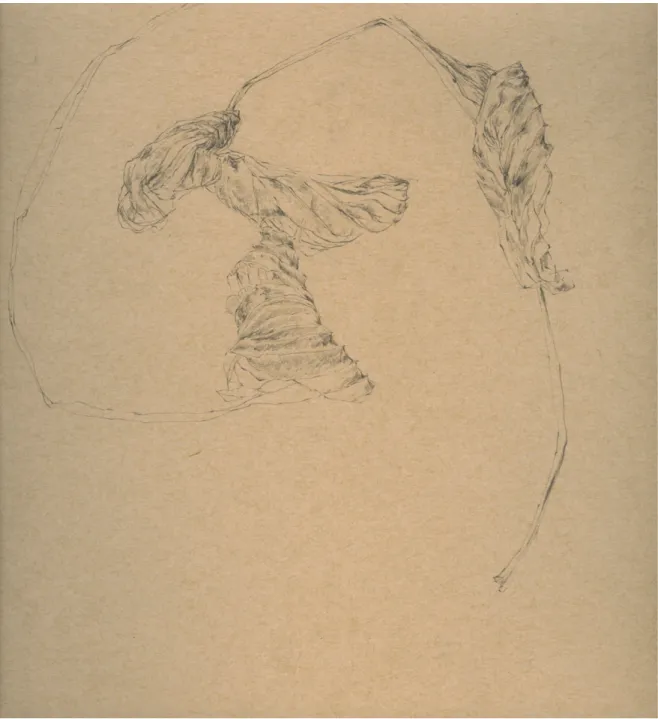

Biophilic drawings & the Fragment

I have been drawing found fragments of nature for several years, interested in this idea of forging a relation with an “individual” of the natural world. Long before I was introduced to Landy and Corner, I felt the traditional landscape-type depiction of nature to be alienating to my lived experience, the “pictured” representations seeming to promote more of a feeling of detachment or distance than intimacy and relation. So, rather intuitively and without an end product in mind, I began to draw the small pieces of nature that I found on my path; a leaf, a seed, a tangled root, enjoying the sense of connectivity that I felt in the process of creating these simple, yet complex drawings that seem to function on both a realistic and an abstract

26Stallabras, Julian, “An artist after breakdown”, Evening Standard (17 december 2002), accessed August 1, 2018.

http://www.standard.co.uk/home/an-artist-after-break-down-7428322.html

Fig. 1.4: Angela Eve Marsh, Dessin Biophilique #34, 2018, graphite on recycled paper

plane. After having completed over 30 of them, I began to wonder, since our experience of urban nature is often fragmented and one on one (the observation of a tree that we cross on our path or a wild plant that grows through the concrete), could this kind of a fragmentary image be closer to our urban experience of nature than the traditional, composite, so-called

landscape pictures? In fragmented images of nature, rather than reducing the heterogeneity to homogeneity by trying to tell it all, we suggest the multiplicity and diversity by only revealing a small part. The intricacy of the individual object, despite its small scale or fragmented appearance, is linked to the infinite complexity of the composite layered and entangled systems. This idea is fortified by Murielle Hladick (2000); " Le fragment permet la recomposition théorique de l’ensemble et rappelle la totalité, il est donc signe, mémoire, mais en même temps, paradoxalement, il prend une valeur intrinsèque de monade.”27 So while the

fragment communicates the complexity of the totality, it also expresses the essence of the singular, the atom, the one. When applied to art, we can say that when only a piece of the totality is given, it is up to the imagination to reconstruct, in a myriad of diverse forms, the ecosystematic complexity of the whole. When we see only a small part of the complexity, we are more capable of image-ining the multitude and the vertiginous28 diversity

of the macrocosm. In a picturesque landscape, all is given to us (often including the emotional tone or mood), and therefore we have little space to create our own interpretations and realities. In the fragment, one opens towards a wealth and a plurality of meanings, narratives and experiences.

27 Murielle Hladik, “Figure(s) de la ruine”, L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui (no. 331, novembre-décembre 2000): 51 Translation: “The fragment allows the theoretical recomposition of the whole and recalls the totality, it is sign, memory, but at the same time, paradoxically, it takes an intrinsic value of monad.”

28 I must give credit to my director of research, Jocelyn Robert, for the use of this term « vertigineuse » (French) or vertiginous in discussing the experience we can have when faced with the infinite complexity of something as relatively “simple” as a wild field.

Fig. 1.5: Angela Eve Marsh, Dessin Biophilique #37, 2018, graphite on recycled paper

In my Biophilic Drawings, I see the act of drawing as a dialogue, a way of forging relations with the fragments of nature that I find. In drawing, a process that is meticulous and time-consuming, I try to listen attentively to my subject, in an open seeking of intimacy and understanding. In my various dispositions of these fragmentary, but whole unto themselves, moments, I sense the macro complexity. I like to see this intimate gesture of drawing as a political act (!) a deliberate, active research for biophilic relationships between humanity (myself) and nature.

This project has been exposed several times in several different ways, the presentation of the drawings posing an interesting dilemma of sorts. While each piece resulted from an intimate dialogue between myself and a fragment of nature, I wanted to explore the possibilities of showing them together, hinting towards this vertiginous complexity that fascinates me so much, the sort of liberty that emerges from the unquantifiable, a wink at the dizzying complexity of which our species is only a fragment itself. The drawings were initially mounted in a grid pattern on a large wall of my studio, which I found interesting as this seemed to suggest a sort of reconciliation between the indiscriminate complexities of each item and the scientific or mathematical matrix within which they were presented. However, in this format we lost the sense of intimacy with each fragment. When I participated in the group show Reclaiming (May 2017 in the exhibition space of the Pavillon Alphonse-Desjardins at Université Laval with Annie Lalande and Karen

Fig. 1.6: Angela Eve Marsh, Dessin Biophilique #8, 2016, graphite on recycled paper

White), I mounted 15 drawings in a row, 20 cm between each, at eye level, with the intent of capitalizing on the possibility of creating intimate relation and engagement between the drawing and the spectator. This seemed to be effective, as the drawings elicited curiosity and comments from the spectators who came to the show, however my director Jocelyn Robert suggested that it could have been interesting to experiment with the audience having to make an effort to access the drawings, by placing them lower to the ground, for example, thus implicating a change of posture in order to be at eye level. In a way, they were “consumed” too easily as fleeting images in the eye-level format that I had presented them, and I understood his point. I exposed them again when I participated in the group exposition during the Rencontre Interuniversaire des Maîtrises en Arts Visuels (RIMAV) (Université de Québec à Outaouais in Gatineau, October 2018), but decided to once again mount them in a row at eye level, as I was concerned that if I played too much with their position, putting them close to the ground, the sense of relation might be lost, and the more audacious positioning of the drawings might be overemphasized, becoming too spectacular. During both expositions I also presented my installative piece Don’t touch the leaves, created from cut recuperated plastic and real leaves (described in detail in Chapter 3), and I felt that both times an interesting dialogue was created between the two projects, where the experiences of intimate observation, fragility (of myself, the fragments, our ecological equilibrium) and culture|nature dialogue were explored in different ways. However, the evolution of the biophilic drawings has not stopped with these presentations. In the late spring of 2018 I began to experiment with putting the drawings in second-hand gilded frames that I found at my local thrift store. The fake gold, baroque-style frames changed the lecture of the drawings, and I found that this interesting disposition created new dialogues between the frames, the fragments and the culture|nature continuum, in a way shouting out my proclamation of the preciousness of these mundane, overlooked fragments of urban nature (from the celeriac that I would prepare for supper to an uprooted weed or browned curled leaf on my path). I framed twelve of my biophilic drawings in this way and exposed them in a group show at our studios during Mars de la Maîtrise in March 2018. I am interested in continuing to experiment with this format, where I am planning a full wall installation, salon-style, of about 50 gilded-framed biophilic drawings; a wink at our capitalist consumption of images, a quiet assertion of a culture|nature cohabitation. Will the experience be overwhelming? Will the detail and relation be lost? I am curious to find out, and hope to realize this installative project in the coming year.

Fig. 1.7: Angela Eve Marsh, Biophilia framed #2, 2018, recuperated frame, graphite on recycled paper

CHAPTER 2: Ecofeminism

We also understood that women all over the world, since the beginning of patriarchy, were also treated like « nature », devoid of rationality, their bodies functioning in the same instinctive way as other mammals. Like nature they could be oppressed, exploited and dominated by man. 29

Pour Descartes, l’environnement est considéré comme séparé de l’homme : il désigne ce qui l’environne et non sa substance. Le dualisme entre l’homme et la nature a permis l’assujettissement de cette dernière par l’homme et donné lieu à une nouvelle vision du monde ... 30

Ecofeminism is a joint feminist and ecological school of thought that proposes that the same patriarchal/capitalist matrix that permits the exploitation of nature also justifies the exploitation of women. It was in the work of Francoise d’Eaubonne, Le féminisme ou la mort (1974) where this term appeared for the first time. Eaubonne defends the position that it is only through a feminist revolution that an ecological revolution can take place, as two of our leading environmental crises today, intensive (industrialized) agriculture and overpopulation are the result of a male-dominated, power and profit-driven society. She does not argue for the replacement of an androcracy by a gynaecocracy (as some other feminists have done and continue to do), but rather envisions a gylany (to use the term later coined by Riane Eisler, a society built on a balance and equality of power between the sexes. Since then, branching theories of ecofeminism have been developed by activists and scholars from around the world, each with varying perspectives on the role of spirituality and academics in this domain, as well as on the role of women as the bringers of balance in an unbalanced world.

However, it can generally be agreed upon in ecofeminist circles that the deconstruction of the culture|nature dichotomy is essential and a redefining of the hierarchical binaries is required in order to obtain balance and equity in our societies. For example, by exploring the revolutionary potential in the quality of passivity (which can be considered as a strength rather

29 Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva, Ecofeminism (London and New York: Zed Books, 2014): preface

30 Vandana Shiva, “Étreindre les arbres”, in “Reclaim, Recueil de textes écofeministes”, ed. Émilie Hache (Paris : Éditions Cambourakis, 2016): 186

Translation: "For Descartes, the environment is considered as separate from man: it designates what surrounds him and not its substance. The dualism between man and nature has allowed the subjugation of the latter by man and given rise to a new vision of the world ... "

than a weakness) “the feminine offers the possibility of undermining that ontological system”31 that elevates the powerful over the powerless and that subjugates the concealed, the

obscure, the passive, and the wild.

Daphne and Apollo

Fig. 2.1: Angela Eve Marsh, Citation of Alice Fulton, 2017, embroidery thread on chip bag32

My readings and interest in the subject of ecofeminism were born quite organically from my project Daphne and Apollo that I began in 2011 and finished during my master’s studies. I

31Carol Bigwood, Earth Muse, Feminism, Nature and Art (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993): 127 32Alice Fulton, Sensual Math (New York: Norton, 1995): 103

started out by painting portraits of individual urban trees, which for me seemed to naturally emanate human traits, their “bodies” emerging in a flesh-coloured palette of tans, pinks, burgundies and scarlet reds. I have always been interested in the anthropomorphic quality of trees, rebounding with female iconography (scars, vulvas, pregnant bellies, graceful arms). In this project, while evoking my very personal, bodily connection with trees, a discourse of gender-based dualities and power struggles seemed to emerge. An investigation of ecofeminist theory became necessary, as I felt there was something of socio-political position that I was trying to express in the work. The binary qualities of force and vulnerability (or we could say passivity, which as previously stated perhaps needs to be reconsidered as a strength) materialize in the presence of trees, which I see as relevant (although not limited to) the strength and struggle of women.

It was Diane Keating, my mother-and-law and published poet, who identified the link between my project and the myth Apollo and Daphne from Ovid’s Metamorphosis. According to the tale, Fig. 2.2: Angela Eve Marsh, Daphne 3, oil paint on recuperated mdf, 2012

Apollo, stung by the malignant arrow of cupid, pursues with a disproportionate pride and an overflowing passion the beautiful Daphne, who wishes to remain single, celibate and free. Terrified by his aggressive advances, she begs her father (the god Pénée) to transform her appearance; “Help me father! If your streams have divine powers change me, destroy this beauty that pleases too well!” 33. In what I see as a very interesting contemporary metaphor, Daphne finds refuge in nature, taking on the form of a tree. Once Daphne is transformed, Apollo decides that he could use her wood in the fabrication of things – “if you can’t be my bride, you will be my tree”34, and so the myth also recalls for me another issue in our

contemporary ecological crises, the consumerism which is promoted as a salve for unsatisfied emotional or spiritual needs. In my ensuing research on the various ecofeminist interpretations of the ancient myth, I came across the work of Alice Fulton, a contemporary American poet who rewrote Ovid’s poem from a pop-culture position with a strong feminist leaning. I also took up the reading of Émilie Hache’s recently published ecofeminist anthology

Reclaim (2016), in the interest of seeing how these theories might contribute to the dialogue

created by the work. With a desire to integrate these writings into my project, I experimented with embroidery on recuperated plastic, thus presenting various citations that I felt contributed to our interpretation of the ancient myth from diverse ecofeminist perspectives.

Fig. 2.3: Angela Eve Marsh, Citation Joanna Macy, 2017, embroidery thread on chip bag35

33 Accessed August 1, 2018. http://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph.htm#488381109 34 Ibid.

35Joanna Macy, “Agir avec le désespoir environnemental”, in “Reclaim, Recueil de textes écofeministes”, ed.

The female body and the challenging of dualities

Carol Bigwood discusses the problematic in ecofeminist thought that has the tendency to encourage or support the women-nature identity, thus simplifying the exploitation of the two. The perceived connection between women and nature was traditionally seen by early feminists like Simone de Beauvoir as a cause of their subjugation, and therefore something to be rejected and overthrown (where the role of maternity was seen as a potential threat to female emancipation). And she is not alone in her thinking:

Feminists long ago identified the association of “women” and “the body” as contributing to women’s exclusion from the cultural sphere (insofar as culture is associated with mind rather than body-related activities). 36

Yet in emphasizing the female, body, and nature components of the dualities male/female, mind/body, and culture/nature, radical ecofeminism runs the risks of perpetuating the very hierarchies it seeks to overthrow. 37

However, there exists another school of contemporary ecofeminism that embraces the link between nature and women as a source of spiritual strength and power (evident in the work of widely-published witch/activist Starhawk), using this position to critique society’s unethical domination of the two. In Émilie Hache’s recent anthology of feminist writings, Reclaim, she identifies the androcratic dualist system as the problem, rather than the association of the female with nature itself.

A quoi peut alors ressembler une articulation positive entre les femmes et la nature, une articulation écoféministe? Pour tenter de répondre à cette question, on peut repartir de ce qui pose problème dans cette identification des femmes avec la nature : ce qui pose problème, ce n’est pas la nature en tant que telle, c’est l’infériorité attribuée à cette nature en raison du dualisme nature/culture. Mais si on sort de ce dualisme? Pour le dire simplement, les écofeministes sortent de l’identification des femmes avec la nature au sens patriarcal et « dualiste » de « les femmes sont inférieures parce qu’elles sont du côté de la nature et la nature est inférieure parce qu’elle s’oppose à la culture (et qu’elle est féminine) ». Elles en sortent en se réappropriant à la fois la « nature » et ce qui est habituellement attribué aux femmes, ce qui est distribué du côté de la féminité. Les écoféministes

36 Terry Field, as cited by Anne-Line Gandon, “L’écoféminisme: une pensée feminist de la nature et de la société” (Recherches feminists, vol. 22, no. 1, 2009): 11

37 Carolyn Merchant, “Ecofeminism and feminist theory” in Reweaving the world, the emergence of ecofeminism, ed. Irene Diamond and Gloria Feman Orenstein (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1990): 102

procèdent en ce sens à ce qu’on pourrait appeler « une inversion du stigmate », sauf qu’il s’agit ici d’un double stigmate concernant et les femmes et la nature, nous faisant nous prendre les pieds dans le tapis en jouant les unes contre l’autre alors que l’enjeu consiste au contraire à tenir les deux ensemble, en retrouvant une conception de la nature non appauvrie, non naturalisée, une version pourrait-on dire écologique de la nature, intelligente, sensible, pour pouvoir revenir sur le lien femmes/nature autrement qu’en le rejetant. 38

This idea of the inversion of the stigma, of leaving the hierarchical dichotomies behind in order to reconceive new relationships and co-habitations, is of great interest to me, which I explore further in Chapter 3, in a perpetual ontological questioning of the reductive dualities that inhabit us.

I presented my project Daphne and Apollo as a solo exhibition in two public libraries in the Quebec city area in 2017, through the Programme de diffusion en arts visuels et métiers d'art, L'Institut

Canadien de Québec. While the first exposition was disappointing due to a very generic exhibition

space and difficult hanging system (which proved challenging with the small tree portraits), the second was a very satisfying fit, in the church-converted-library of St Jean Baptiste. The space was quite small and intimate, and so I had to make a judicious choice of what pieces to present (as I had completed over twenty paintings in the project). Installed alongside the stained-glass windows that remained from the library’s previous life as a church, an interesting dialogue was created between the embroidered plastic (recalling the past in an contemporary aesthetic), the paintings and the religious (and admittedly patriarchal) iconography, emphasizing a complexity in our experience of the sacredness of the space and the narratives conveyed.

38 Émilie Hache, ed.. Reclaim, Recueil de textes écofeministes (Paris : Éditions Cambourakis, 2016): 22

Translation: “What can a positive articulation between women and nature look like, an ecofeminist articulation? To try to answer this question, we can start from what is problematic in this identification of women with nature: what poses a problem is not the nature as such, it is the inferiority attributed to this nature because of the dualism nature / culture. But if we get out of this dualism? To put it simply, the ecofeminists reject women's identification with nature in the patriarchal and "dualistic" sense of "women are inferior because they are on the side of nature and nature is inferior because it opposes culture (and is feminine) ". They come out by reclaiming both "nature" and the qualities that are usually attributed to women or femininity. In this sense, ecofeminists are doing what could be called a "reversal of the stigma", except that this is a double stigma concerning women and nature, and so we get mixed up by playing against each other while the stake consists on the contrary to hold the two together, by finding a conception of the nature not impoverished, not naturalized, a version could one say ecological of nature, intelligent, sensitive, to be able to return to the woman / nature bond other than by rejecting it”.

Fig. 2.6: Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of solo exposition Daphne et Apollon St. Jean Baptiste public library, Quebec City, 2017

The influence of ecofeminist theory in my art practice has not concluded with Daphne and Apollo. It seems to continue on and colour my interpretation and experience of other ongoing work, where the importance of sewing and embroidery for me is an important reappropriation of traditionally viewed female skills and techniques. In sewing I am interested in merging voice with skill, history with the contemporary context and enjoy exploring complicated political subjects through the rich heritage of the fibre arts. My project La Courtepointe that I recently exposed in Montreal was a 12’ x 5’ “quilt” sewn from transparent and translucent plastic recuperated from my daily life (see Chapter 3 and 4 for an in-depth discussion of this project). My most recent project, La Friche is created from small natural fragments collected from urban

wrap. In this project, I employ an ecofeminist position in my analysis of how our urban “wastelands” are managed, which I see as a strong metaphor for the domination and suppression in our society that seeks to dichotomize culture from nature, civilized from wild (and we could also say intellect from emotion and male from female). In this project, I am reflecting on our human-centric need to hierarchize the usage of our spaces, speaking for the place of the wild, the other, the voiceless, in our urban landscapes, arguing for a reconciliation between our societal need to control and nature’s desire to re-establish and heal.

CHAPTER 3: Foraging

Fig 3.1: Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of project Don’t touch the leaves, 2017, cut chip bags and leaves

I see myself as a forager in art-making, which differs from the original definition of the word foraging, being the searching for wild food. I use the term forage in reference to my process of finding the materials for my art, an active seeking what is already there and sometimes hidden. This sort of conjuring out of obscurity can also manifest as a re-thinking of functions, like the usually ignored plastics that we use in packaging, transformed into something precious like an art object and aesthetic experience. I forage for natural subjects for my biophilic drawings, for wood polished clean by the river for a collaborative project I realized in a school in St. Pascale, for mdf poster-board which I reconditioned for my Daphne and Apollon (amongst other) paintings, for the plastic for my sculptures and tapestries. This act of foraging provides me not only with sources of materials but also with inspiration for the projects that follow.

Foraging for me has to do with my relationship to my environment, both natural and built, as well as my ethical intent to minimize my resource consumption; my work is made from pre-existing materials (and thus looks at transforming what already exists) in a deliberate gesture on my part to defy dominating consumer-based systems. Purchasing my clothes and furnishings from charity thrift stores, taking home chairs left out to the garbage truck or a blanket-sized piece of bubble wrap from a neighbour’s bin, I aim to consume as little new goods as possible. Living in a society of excess, I find that the abundance (oftentimes overwhelming) of raw and transformed materials around me creates a felt urgency to find ways of basing the materiality

of my artistic practice on recuperation, where this practice of foraging has a philosophical and ethical logic.

Far from mute, the recuperated materials, with their history and signification, instigate an immediate dialogue quite different from the one-directional imposition I would feel when working with neutral, virginal surfaces like canvas. I began experimenting with mdf poster board about 5 years ago, searching for a recuperated, hard surface that I could use for oil painting (having previously experimented with fabric). As I made my periodic rounds in the local thrift stores, I noticed an abundance of plaqued posters, mounted on mdf. I began by reconditioning the boards with electric and manual sanders to completely remove the poster in order to create a surface for painting, but soon realized the interest and potential in leaving fragments of the original image as background or context. The idea of the palimpsest, of layers of history, story and reference seemed relevant, and opened new doorways to different relations within the painting itself.

In seeking coherence in my pictorial work, I found a source for natural earth-based pigments, from the company Earth Paints, pigments that are sustainably sourced by an American artist who founded her own small business, seeking a way of oil painting without the toxicity. With these pigments I am able to mix my own oil colours as well as watercolour paints, using only soap and water to clean my brushes. This creates a restrictive palette, but I don’t mind working within the constraints of a “natural” spectrum, as these limitations impose a rigor and a discipline that assures a consistence with my ethical questioning and seems to fortify my intent to create an “earth-based”, biophilic practice.

I am fascinated by the alchemy that can happen when an artist recuperates a material and, eclipsing its original form or function, transforms it into an entirely new presence or experience. The work of Ghanaian/Nigerian artist El Anastui comes to mind, where materials as banal and basic as bottle caps are reconfigured into a tapestry of rich, complex colours and rippling textures. In his work he speaks of the history of the bottled drinks, a colonial import whose remains litter the African landscape. Montreal-based Myriam Dion cuts the daily newspaper with her razor into intricate, lace-like creations, transforming the everyday into the precious. Giorgia Volpe weaves and crochets all sorts of materials that we would have simply thrown away to create her sculptural and installative works, such as ribbon from old cassette tapes or plastic bags in the form of a huge circular woven rug. These artists’ transformations all have something in common with my own practice, where the mundane or even invasive evolve with manual skill, time and labour into another experience, a new manifestation of being.

My sculptural work in recuperated materials was born from my socio-ecological militancy (a refutation of our linear, consumerist ways of functioning) and seen as a reconciling gesture, an act of taking awareness or prise de conscience. It started with my difficulty in witnessing the huge quantity of plastic bags that I was throwing out everyday, so in conscious gesture, I began to collect them, creating a horribly large pile in my studio after several months. Seeking a way to somehow transform this material, I began to sew it, first creating protective but suffocating pouches that I used in my Smother project (2015), later creating uterine-like forms that I eventually began to see as abandoned bee hives (after reading on the disappearance of worldwide bee populations) which turned into my Ruches project (2016). During my master’s studies, my work in plastic continued with La Preservation (2017), La Courtepointe (2018) and La

Friche (2018). Through these various projects, I have found that even after the transformative

intervention of sewing, while the form and the aesthetic experience changes, in material terms they still remains plastic, troubling in their permanence and essential unchangeability. As one of my student’s said during a Culture à l’École project in a local high-school; “oui, mais ça reste que

c’est toujours du plastique39”. Despite the emergence of a new experience, I was not able to change the material’s essential nature, as a true alchemist might have been able to do. However, within this unforgiving reality, interesting dispositions of dichotomies can emerge –

39 Translation : Yes, but it still remains plastic

the beautiful sewn plastic that becomes crystalline in the sun, like a seductive mirage that almost (but not quite) overshadows its malignant, disturbing reality.

Fig. 3.5: Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of installative project La Preservation sewn plastic and natural found objects, 2017. Photo credit : Mériol Lehmann

La Préservation

In this installative project that I created for a collective exposition during Mars de la Maîtrise, I encapsulated the small natural fragments that I had collected for my biophilic drawing project (now dried and crumbling) into sewn pouches of transparent plastic and mounted them together in a Cartesian grid pattern on a white wall. In this project I was exploring this intersection between poles; the logical-scientific and emotional-natural, try to juxtapose and create dialogue between these binary realities. The sewn plastic pouches became transformed

into quasi-organic beings, where the untamed long threads dangling from each one moved naturally in the ventilated air, tangling together and interconnecting the individual pockets, creating a sort of ecosystematic resonance despite their calculated isolation. For me, the piece also expresses my questioning of our societal view of death, our desire to prevent the natural entropy of things, (hence the seductivity of plastic in our societal seeking of immortality, this material that seems to resist age and the passage of time). However, I find it interesting that the permanence of plastic seems contradictory to the transparency of its appearance, a felt fragility despite its material reality.

Fig. 3.6: Angela Eve Marsh, photo documentation of installative project La Preservation sewn plastic and natural found objects, 2017. Photo credit : Mériol Lehmann

Don’t touch the leaves

This project was created in 2017, conceived of as an installative piece to be exhibited alongside my Dessins biophiliques/biophilic drawings (which I saw as creating a sort of felt balance between the pure nature presented in the drawings and the reality of our hybrid nature-culture environments). The project was started in my collection of chip bags, much like my collection of transparent plastic for the aforementioned projects. Chip bags are quite seductive as a material due to their silvery inner skin and their bright, garishly coloured exterior. But they are also stunningly wasteful; a thick, unrecyclable plastic to package something as ephemeral as

a chip. After a fair bit of reflection, I finally decided to cut realistic shapes of leaves out of the bags, an ironic wink at the idea of an artificialized, human devised, hygienic “nature”, like the astro-turf soccer fields or “lawns” that stay always green and clean, or fake flowers in perpetual bloom. My idea was to make a large pile in the middle of the exhibition space in which children could jump and play, in leaves that never brown or decompose. However, after I installed them in the gallery, during the evening sweep by the custodian they were collected and disposed of. While about 2/3 of the leaves were salvaged from the garbage, there wasn’t enough to convey my original idea, so I decided to add real leaves into the mix. Finally, the resulting piece was much more powerful, evoking a sort of uncomfortable duality between the natural and the artificial, also suggesting the contamination and seductive invasion of plastics in our environment. I have shown the piece two times since, keeping the natural leaves (which are continually degrading) with the plastic ones, enjoying the contrast between the entropy to which the real leaves are succumbing alongside their ageless, glittery plastic counterparts.

Fig. 3.7: Angela Eve Marsh, Photo documentation of Reclaiming exhibition, 2017