Does Social Innovation vary with the Organizational Form? Exploring the Diversity of Fair Trade Social Enterprises in Europe

Benjamin Huybrechts Centre for Social Economy

HEC-University of Liège Management School

Contact:

b.huybrechts@ulg.ac.be

Sart Tilman B33 Bte4 4000 Liège BELGIUM

Does Social Innovation vary with the Organizational Form? Exploring the Diversity of Fair Trade Social Enterprises in Europe Abstract

A common view in the literature on social entrepreneurship and social enterprise is to highlight the fact that social innovation crosses the organizational forms. But does that social innovation should be considered regardless of the organizational form? Fair Trade (FT) offers a quite interesting example of both a social innovation and a field in which diverse organizational forms coexist. My research questions are twofold: (1) what are the different types of organizational forms that underlie social innovation in the FT sector?; (2) do these different forms bring different types of social innovation?

The methodology consists of interviews with the leaders of 57 Fair Trade Social Enterprises (FTSEs) in four European regions: Belgium, France (Rhône-Alpes), United Kingdom (England) and Italy (Rome). The findings show that the legal forms and governance models– the two elements of the organizational form considered here–can be combined into five categories of organizational forms: individual, manager-owned business, volunteer-based, multi-stakeholder cooperative and group. These categories seem to be linked, at least to a certain extent, to the age of the FTSE and to its goals. Certain forms seem to signal a particular type of social innovation. Volunteer-based FTSEs use education and advocacy as the main channel to pursue social change at the global level, and see the partnerships with the producers in the South as a vehicle to support the former goal. Individual and business-form FTSEs focus on offering benefits to the producers through a profitable commercial activity. And multi-stakeholder cooperatives and groups generally seek to combine both types of social innovation. However, nuances exist and lead to considering the organisational form as vehicles that may serve various purposes according to the context and the entrepreneurs’ profiles.

I suggest three theoretical frameworks to interpret the diversity of organizational forms and its link with the logics of social innovation. Neo-institutional economics allow to see organizational diversity as the result of the production of different types of goods within the “FT bundle”. New institutionalism in organizational analysis emphasizes organizational diversity as the result of either weak (or non-existent) or multiple institutional logics. And institutional entrepreneurship highlights the ability of FTSEs to shape the environment in a way that legitimizes their own way of conceiving social innovation. I conclude that these three frameworks offer complementary explanations to organizational diversity and that the latter is an asset rather than an obstacle for carrying social innovation in multiple and complementary ways.

Keywords: Social Enterprise, Social Innovation, Fair Trade, Organizational Diversity, Neo-institutional theories, Europe

Does Social Innovation vary with the Organizational Form? Exploring the Diversity of Fair Trade Social Enterprises in Europe 1. Introduction

A common view in the literature on social entrepreneurship and social enterprise is to highlight the fact that social innovation crosses the organizational forms (Battle Anderson & Dees, 2006; Mair & Marti, 2006). Contrarily to previous concepts locating social innovation in well defined organizational forms (such as the co-operative movement and the social economy), social entrepreneurship highlights the ability of several type(s) of organization(s) to produce social innovation. Although certain authors underline the fact that most social enterprises adopt nonprofit or cooperative forms and that these forms may secure the pursuit of the social mission (Defourny, 2001; Defourny & Nyssens, 2006 and other authors of the EMES network), a larger view suggests that social innovation may be carried by individuals and businesses under a wide array of forms (Battle Anderson & Dees, 2006; Nicholls, 2006), including corporations (Austin et al., 2006a). Based on the observation of “blurring boundaries”, the concept of “sector-bending” refers to the ability of social enterprises to develop across the traditional borders separating, typically, nonprofit and “for-profit” institutions (Austin et al., 2006b; Dees, 2001; Nicholls, 2006). But does that mean that issues of organizational form have become irrelevant when examining social innovation?

Fair Trade (FT) offers a quite interesting example of both a social innovation and a field in which diverse organizational forms coexist. The institutionalization of the movement, its opening to the “mainstream” and the arrival of new entrepreneurs and businesses has tremendously increased organizational diversity. I focus here on “Fair Trade Social Enterprises” (FTSEs), i.e., organizations that deal exclusively with FT products (Doherty & Tranchell, 2007; Huybrechts & Defourny, 2008). My research questions are twofold. First, I wish to highlight the different types of organizational forms that underlie social innovation in the FT sector, through a taxonomy that goes further than previous attempts in the literature (e.g. Diaz Pedregal, 2007; Wilkinson, 2007). The second and most important question examines how these different forms might be linked to different types of social innovation. I particularly view social innovation as corresponding to different articulations of the economic activity, the social mission and the political message, which I identify as three core elements of FT (Huybrechts & Defourny, 2008) –and social enterprise in general.

This article adopts an inductive perspective. After the introduction, the second section recalls the fundamentals of FT and presents the content and the methodology of the field study, led with FTSEs’ leaders in four European regions. In the third section, I present the descriptive findings, articulated around the two key questions of this article. The fourth section then suggests three theoretical approaches to discuss the findings. These approaches all claim an affiliation to the “institutional tradition”: economic new institutionalism, new institutionalism in organizational analysis and institutional entrepreneurship–the last two ones being closely linked to each other. As social enterprises can be seen as “new institutional arrangements”, it

is not coincidence that these three approaches have already been used, although separately, to analyze them (Bacchiega & Borzaga, 2001; Dart, 2004; Mair & Marti, 2006; Nicholls & Cho, 2006). The added value of my analysis is to examine the respective contributions of these theoretical approaches in understanding the rationale to organizational diversity and its meaning in terms of social innovation.

2. Field and methodology 2.1. Fair Trade

Most authors locate the origins of the FT movement just after the Second World War, with experimental initiatives of import and distribution of handicraft, carried by NGOs and charitable organizations with a religious background (Diaz Pedregal, 2007; Moore, 2004; Nicholls & Opal, 2005; Raynolds et al., 2007). After two decades of practice and rule-setting, a first step1 of institutionalization and consolidation was achieved in the late 1980s with the creation of several international networks such as EFTA2 and IFAT-WFTO3 (Diaz Pedregal, 2007; Moore, 2004; Raynolds & Long, 2007). It is at that same period that labeling initiatives appeared, starting in the late 1980s with “Max Havelaar”4 in the Netherlands. These initiatives joined together into “FLO”5 in 1997. The emergence of labeling brought a fundamental change in the evolution of FT (Moore et al., 2006; Raynolds & Long, 2007). Indeed, the possibility of having products recognised as meeting the FT standards by an external certifying body and not by the importer (or distributor) itself opened the door of the FT sector to any type of company. Mainstream businesses, including supermarkets and food multinationals, started selling FT products, which resulted in a huge increase in the volume of FT sales but also in a number of debates about the impact of mainstreaming on the original aims of the FT movement (Moore et al., 2006; Nicholls & Opal, 2005; Raynolds & Wilkinson, 2007).

Common in the practice6 and in the academic literature around FT is to divide the movement into two main “wings” articulated around a specific distribution strategy (Gendron, 2004; Moore, 2004; Nicholls & Opal, 2005; Raynolds et al., 2007; Renard, 2003). On the one hand, an “integrated” system of importers and worldshops selling to sensitised consumers. On, the other hand, a “labeled” system including mainstream businesses selling products certified by

1 Several authors (e.g. Nicholls & Opal, 2005) consider the previously mentioned initiatives such as “charity

trade” as constituting the “first wave” of FT. Without neglecting the contribution of these previous initiatives to FT, we consider the rise of FTSEs in the 1970s as the first concretization of FT as we know it nowadays.

2 European Fair Trade Association

3 Originally “International Federation for Alternative Trade”, later changed into “International Fair Trade

Association” and finally to “World Fair Trade Organization” in 2008.

4

The name of the hero in Edouard Douwes Dekker’s (“Multatuli”) books, who takes the defense of small-scale tea producers in Dutch colonies.

5 Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International

6 E.g. http://www.wFTSE.com/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=612, viewed on

FLO. In 1999, the four main FT networks gathered to work on a common definition of FT. This resulted in the ““FINE”7 definition, reviewed in 2001 and based on a large consensus: Fair Trade is a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalised producers and workers - especially in the South. Fair Trade organizations (backed by consumers) are engaged actively in supporting producers, awareness raising and in campaigning for changes in the rules and practice of conventional international trade.

Although the “two-wing picture” of FT is still useful and reveals a fundamental tension in the FT movement (Gendron et al., 2009), it has become insufficient to capture the whole diversity and complexity of the current FT landscape. Indeed, several organizations and supply chains are based on both distribution strategies (Ozcaglar-Toulouse et al., forthcoming; Wilkinson, 2007). We find an increasing number of actors selling non-labelled FT products through a variety of channels, some of which can be “mainstream” (B2B sales for instance) and others “specialized”. In recent years, many small businesses have emerged in the FT sector without belonging to one of the traditional FT systems: they constitute what some start calling a “Third FT wave” or third institutionalization –the first wave being the pioneers’ and the second being FT labeling and mainstreaming (Poos, 2008). These new companies have often established links with other FTSEs, leading to the emergence of local “bottom-up” networks that cannot be captured through the classical distinctions in terms of “wings”. I thus agree with recent work that acknowledges that “Fair Trade is translated into chains, structures and organizations that are far more numerous and varied than what a simplistic analysis [...] restricted to the sole labels [and networks] grouped within FINE might suggest” (Gendron et al., 2009b). Hence, the analysis of social innovation at the organizational level should not simply be based on the distribution strategies and affiliations of the FTSEs: I suggest that the organizational form is one indicator (among others) that deserves attention.

2.2. Fair Trade, social innovation and social enterprise

FTSEs have been quite early taken as examples of social enterprises and they have clearly contributed to the shaping of the social enterprise concept (Alter, 2006; Martin & Osberg, 2007; Nicholls, 2006), particularly in the UK.8 Among her taxonomy of social enterprises’ models, Alter (2006) describes FTSEs as mission-centric and embedded: the social enteprise is not just a device to raise resources to achieve a distinct social mission, but “the enterprise activities are 'embedded' within the organization's operations and social programmes" (p. 212). FT is often described as a social innovation in the sense that its principles make it possible to achieve economic and social benefits simultaneously. Even though the idea of fairness in trading relationships and the concept of fair price are far from new (see for

7

FINE is an informal network set up in 1998 and gathering the four main Fair Trade umbrella organizations at that time: FLO, IFAT, NEWS! and EFTA.

8 Examples include numerous collaborations among FTSEs and social enterprise networks (for instance Social

Enterprise London) or the exemplification of FTSEs’ leaders as social entrepreneurs (for instance, Penny Newman, former CEO of British FTSE Cafédirect, designated as “Social Enterprise Ambassador” in 2007).

instance the cooperative movement), the set of rules and practices created by FT pioneers and the achievement of producer support through a market-based solution can be considered as quite innovative. The institutionalization of FT, particularly through the FT label, is a nice example of “scaling up” of the social innovation (Nicholls, 2006a).

A more encompassing analysis is suggested by Nicholls (forthcoming), who extends Dees and Battle Anderson’s (2006) distinction of two avenues to social entrepreneurship (“social enterprise” and “social innovation”) to describe FT. He suggests that the first type of social entrepreneurship is useful to characterise FT actors (either social enterprises or corporations) that focus on market mechanisms and strategies as the main vehicle to develop FT. On the other hand, FTSEs that rather focus on education and advocacy to influence the conventional market are closer to the vision of “social innovation”. As already mentioned, while acknowledging the adequacy of such a distinction in the context of FT, I would consider these two avenues as ideal types between which there may be a continuum of behaviours. Moroever, I would suggest using less ambiguous terms to name the two logics. Indeed, as Dees and Battle Anderson (2006) admit9, both types of social entrepreneurship involve social enterprises: naming only one school of thought “social enterprise” can thus be misleading. The same goes for social innovation: both types of social entrepreneurship are about social innovation, it is the way of conceiving it that distinguishes them.

Indeed, the focus on education and advocacy aims to transform consumption habits and, on the long term, international trading rules and practices in an “innovative” way compared to the current situation, in a way that includes social and environmental concerns in the economic transactions. The partnerships with producers in the South are a first attempt of concrete illustration of this innovation, but the ultimate goal lies in the scaling up of this initiative to the whole economy, which would enable the greatest possible impact on producers. This conception of social innovation is more global and political, thus corresponding to the “movement-oriented” logics (FT is seen as a social movement and not just a market). In contrast, the “market-oriented” avenue to social innovation is less ambitious in terms of political transformation of the economy, but invests more in producing immediate material benefits for the producers. In this view, the social innovation consists in providing opportunities to the producers so that they can grow and insert themselves in conventional trading channels. The aim is thus not so much that of transforming the market, but rather that of providing a better access to it for producers who are currently excluded from international trading channels (Gendron et al., 2009a; Renard, 2003). As the subsequent analysis will show, the disctinction of these two types of social entrepreneurship is not always clear-cut at the FTSEs’, organizational level. Indeed, FTSEs may be located at different places on the continuum between these two visions. Certain FTSEs may even combine them, with organizational actors (employees, volunteers, etc.) and stakeholders closer to one or the other vision. This may lead to a typical tension of being both “in” and “against” the market (Fridell, 2003; Le Velly, 2004). But, following the idea of complementarity between the use of the

9 In a footnote (nr 41), Dees and Battle Anderson explain that the term “Social Enterprise” has been chosen for

this school of thought on the basis of a “convention” rooted in the American practice. They admit that such a term should ideally not be linked to one particular school of thought but that it should be left as a generic name.

market and the aim of transforming it (Nicholls, forthcoming), such a hybridization of logics within FTSEs may also be an asset.

2.3. Methodology

In order to capture the organizational diversity in FT and its implications in terms of social innovation, I looked at a relatively high number of FTSEs in different contexts. I obtained interviews with the leaders of 57 FTSEs in four European regions10: Belgium (15), France (Rhône-Alpes – 22), England (9) and Italy (Rome – 11). An Internet research allowed to identify the FTSEs in each region (sometimes with the help of a network11 or a support structure12). Following the WFTO13, FTSEs were defined as “organizations directly engaged in Fair Trade through their trading activity”, which involves performing one or several of the following economic functions: import, transformation, wholesale, and retail (Krier, 2008). In each region, all FTSEs corresponding to this criterion were contacted by e-mail. The positive response rates range from 40% (England) to more than 70% (Belgium).

In each FTSE, I personnally met the leader, whose title varies with the type of structure: “CEO” or “general manager” in FT businesses, “director” in some nonprofit FTSEs, “coordinators” in most worldshops, etc.14 The face-to-face interviews lasted between one and two hours, with an average of one hour and a half. I used a semi-structured interview guide, with questions about the history of the FTSE, its organizational form, and its goals and activities. The information from these interviews was used in two ways: through categories for each variable (see next point), and through quotations. Organizational documents were consulted when available (annual reports, presentation leaflets, etc.), as well as the websites.

3. Descriptive findings

3.1. Organizational form Legal form

The organizational form may take different meanings and entail different elements. I will not deal here with the “structure” or “configuration” of the organization, as developed by Miller and Mintzberg (1984).15 A first element I consider is the legal form, especially central in the economic organizational literature. In certain conceptions of social entrepreneurship, the legal form is put forward as a key element that may secure the pursuit of the social mission, similarly to the approaches developed around the co-operative movement and the “social

10

The regions were chosen because of their high concentration of FTSEs as well as because of logistic reasons.

11 Roma Equa & Solidale in Rome and British Association for Fair Trade Shops in the UK. 12 Fair Trade Centre in Belgium and Equisol in Rhône-Alpes.

13http://www.wfto.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=153&Itemid=186&lang=en, viewed on

September 13, 2009.

14 On two occasions, it was not possible to meet the person with the highest level of responsibility, but the

communication manager. When several people were in charge of the FTO, I met one or all of them (in two cases of worldshops where the “team of coordinators” was interviewed).

15

economy” or “Third sector” (Defourny, 2001; Defourny & Nyssens, 2006). Most of the literature, however, considers that social entrepreneurship should not be restricted to particular legal forms, the choice of which is influenced by several factors. As stated by Battle Anderson and Dees (2006), “[w]hile many social entrepreneurs do adopt a not-for-profit form of organization, they, and those researching them, should view the choice of the legal form as a strategic decision, not a state of being. Legal forms of organization are artefacts; tools people have designed to serve various purposes” (156).

Four types of legal forms were identified, in spite of the different names and legal definitions: - Nonprofit organizations16 (28%)

- Cooperatives17 (22%) - “Businesses”18 (26%) - Individuals19 (12%)

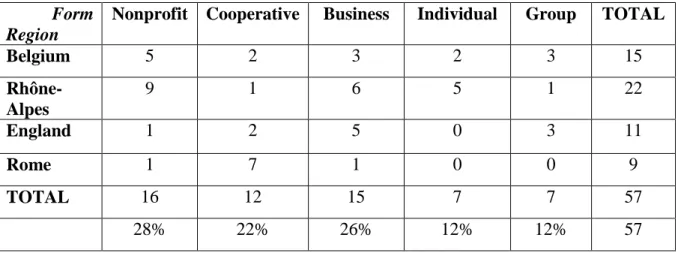

A fifth category consisted of “group” structures, composed of a nonprofit and a cooperative (Miel Maya, Oxfam-Wereldwinkels) or a nonprofit and a business (Traidcraft, Twin, People Tree). Although there may be debated about whether these groups are composed of two distinct FTSEs or not, I considered the group structure as a specific –and innovative– form on its own. The distribution of legal forms varies, of course, according to the region, as the following table shows.

Table 1: Distribution of the legal forms in the four countries of the study

16

“Association sans but lucratif” in Belgium, “Association Loi 1901” in France, “Charity” in the UK and “Associazione (senza fine di lucro)” in Italy.

17 A couple of workers’ cooperatives (e.g. Just Fair Trade in the UK or the SCOP –“Société coopérative de

production”– Ethiquable Gourmand in Rhône-Alpes) or more often multi-stakeholder, general interest cooperatives (e.g. Zaytoun, a British CIC –“Community Interest Company”– and Soli’gren, a SCIC –“Société coopérative d’intérêt collectif”)

18 “Société anonyme” or “société privée” in Belgium and in France; “Società a responsabilità limitata” in Italy;

and “Public limited company” (PLC) or “Company limited by shares” in the UK.

19

Independent entrepreneurs

Form Region

Nonprofit Cooperative Business Individual Group TOTAL

Belgium 5 2 3 2 3 15 Rhône-Alpes 9 1 6 5 1 22 England 1 2 5 0 3 11 Rome 1 7 1 0 0 9 TOTAL 16 12 15 7 7 57 28% 22% 26% 12% 12% 57

Governance

A second entry I considered is the governance of FTSEs. I focused on the types of stakeholders represented in the governance structures (volunteers, investors, NGOs, producers, etc.) and on how the leaders viewed the role of governance. For these two elements, I followed Cornforth’s analysis of governance in the context of social enterprises (Cornforth, 2003; 2004). Based on the composition of the governance structures (mainly the Board of Directors) and on their role as perceived by the leader, I distinguished three categories:

- FTSEs dominated by founders-managers (36%)

In small entrepreneurial FTSEs, it happens often that the founders are either in sufficient number to compose the Board (generally the legal minimum is three), or are supported by a small number of investors who are often friends or family members but have no real decision-making power.20 In these cases, the founders wish to manage the FTSE on their own and thus do not need or want to involve other people beyond their relatives. The Board exists either only on the paper or are, at best, as a “rubber stamp” that may give legitimacy and in some cases expertise to support the managers’ action (Cornforth, 2003).

- FTSEs dominated by volunteers (29%)

Most nonprofit –mainly pioneer– FTSEs’ governance structures are composed only of volunteers. Others have involved stakeholders such as employees or partner NGOs, but only to a certain extent, with volunteers remaining dominant.21 Volunteer-based FTSEs put much emphasis on representation, conformly to the democratic model widely observed in nonprofit and cooperative organizations (Spear, 2004). In the context of FT, internal democracy may be seen as part of the political side of the FT project, coherently to what is required for the producers in the South (Develtere & Pollet, 2005).

- Multi-stakeholder FTSEs (35%)

A number of FTSEs have different stakeholders involved in their governance structures, without one exclusive dominant group. Certain of these FTSEs were initially single-stakeholder (typically, volunteer-based) and progressively included other single-stakeholders in the governance structures who acquired an increasing decision-making power. Other FTSEs started immediately with a multi-stakeholder model, for instance when this was required by the law (e.g. Soli’gren).

20 This conclusion might appear biased by the fact that only the leaders were interviewed and that they might

have overestimated their power with regard to the investors’. Yet, further questions about the Board meetings, their preparation and their outcomes suggested the opposite: leaders seemed to control much of the governance process, leading us to this conclusion.

21 FTSEs in which other stakeholders besides volunteers are involved to a significant extent, with real influence

on decision-making –at least from the point of view of the manager–, are included in the multi-stakeholder category.

Taxonomy

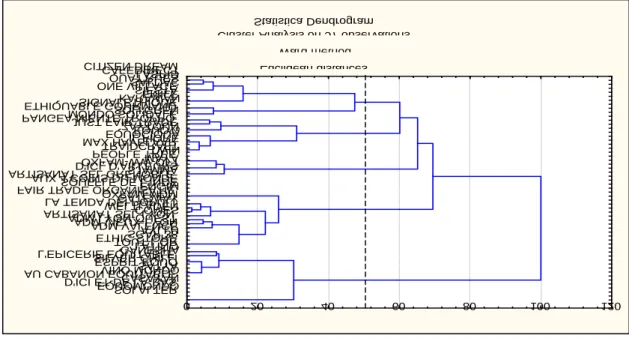

If we combine the categorizations for the legal form and the governance model through a cluster analysis22, we can identify five categories that seem internally consistent and distant from each other, as we can see on the following dendrogram.

Figure 1: Dendrogram resulting from the cluster analysis

Let me present these five categories of organizational forms, starting with the simplest and progressively adding complexity. The first category is composed of thirteen individual or quasi-individual FTSEs. These FTSEs are generally very small (in terms of both people and turnover), have an individual or business legal form and a manager-based governance. In the second category, we find thirteen manager-owned business-form or cooperative FTSEs with sometimes a few investors in the governance structures and, exceptionally, other stakeholders. Their size is generally larger than in the first category. The third category is composed of seventeen volunteer-based nonprofit or cooperative FTSEs. FTSEs in this category are generally older than in the previous categories, although several volunteer-based nonprofit FTSEs have been recently created (e.g. Artisans du Monde shops or Roman worlshops). The size is medium or large in terms of number of people involved (employees and volunteers), but relatively small in terms of turnover –at least compared to the number of people involved. The fourth category is composed of five FTSEs, whose distinctive feature is quite easy to identify: they are all multi-stakeholder cooperatives. Finally, the fifth category is that of the multi-stakeholder group FTSEs (eight cases). Finally, there are a few outliers that cannot be clearly situated in the abovementioned categories. The most notable one is Cafédirect, which probably corresponds to a sixth type of FTSE that is not well represented in the sample. FTSEs such as Divine Chocolate and Agrofair could be included in such a category that could

22 Using the classical technical features: Ward method, Euclidean distances and cut of the dendrogram at 50% of

the maximal distance between the observations (Simar, 2008).

Statistica Dendrogram Cluster Analysis on 57 observations

Ward method Euclidean distances

0 20 40 60 80 100 120

SOLALTER EQUOMONDO D'ICI ET DE LA-BASCASAYAN AU CABANON EQUITABLEVINO MUNDOSATYA ESPRIT EQUO SILVER CHILLI L'EPICERIE EQUITABLEGANESHALATINO TOUT L'OR ETHIC STORESGAP 38AYLLU ADM VALENCE ADM VIEUX-LYON ADM LYON-OUEST ARTISANAT SEL LYONWELTLADENCOMES

LA TENDA DEI POPULIOXFAM-MDMGATEWAY FAIR TRADE ORGANISATIESOUFFLE DE L'INDEENGIM AUX 4 COINS DU MONDE ARTISANAT SEL GRENOBLED'ICI, D'AILLEURSSJAMMA OXFAM-WW-OFTPEOPLE TREEMAYA TWIN TRAIDCRAFT MAX HAVELAAREQUOCIQUAIL FIORE EQUO% ZAYTOUN JUST FAIR TRADE PANGEA NIENTE TROPPOMONDO SOLIDALESOLI'GREN ETHIQUABLE GOURMANDSIGNALETHIQUEKARAWAN EMILE SIESTA ONE VILLAGEQUAT'RUESSALDAC LASPID CAFEDIRECT CITIZEN DREAM

be called “NGO-launched multi-stakeholder businesses”. This category would thus combine features of the Type 5 category (because of the multi-stakeholder governance and the missionary-bureaucratic nature of these FTOs) and the Type 2 category (because of their business legal form and functioning and their 100% market resources).

3.2. Organizational form and social innovation

To capture the type of social innovation pursued by the FTSEs, I asked about the organizational goals (both those stated in the official documents and those perceived by the leader). Organizational goals have been emphasized as a key variable in social enterprises, especially given the multiple (economic, social, political) goals pursued by these organizations (Nyssens, 2006). Yet, they are likely to be different according to each member in the organization (Mintzberg, 1985). Moreover, there may be discrepancies between the stated goals and the concrete, day-to-day activities. This is why I also looked at the organization’s activities and practices, despite the difficulty to directly observe them. Besides the stated activities, I used indirect indicators such as the number of employees and the proportion of the turnover devoted to each activity. Finally, other variables were captured such as the age of the FTSE, the profile of the leader and the proportion of market resources. When asking the leaders about the goals of their organizations, concerns related to the social mission were clearly dominant. The other goals –economic and/or political– were often presented as means or intermediate goals towards the ultimate goal of improving the producers’ livelihoods23, confirming Davies and Crane’s (2003) observation in the case of Divine Chocolate. I could thus not discriminate among FTSEs on the basis of the importance of the social mission, but rather on the type of social mission and on the strategy used to achieve such a mission.

Combining the goals, activities, and other indicators (people and resources), three main patterns could be distinguished. We can link these patterns with the different types of social innovation introduced in the context of FT, despite a number of nuances.

- “Movement-oriented”. Relatively low economic development (e.g., turnover compared to number of employees). Sales integrated in the socio-political project (typically through the worldshops). Explicit organizational involvement in education and advocacy (but content of education and advocacy varies). Social mission pursued through concrete partnerships with the producers but also through influencing international trading rules and practices.

- “Market-oriented”. Focus on the trading activity (active investment in product development, new distribution strategies, search for profitability, etc.). Social mission best achieved through sales of products. Education and advocacy relatively peripheral.

23 With, however, different nuances. Some insisted on giving producers access to the market while others went

- “Movement and market-oriented”: combination of the two previous patterns (either integrated to each other or pursued separately). Different behaviors regarding the political goals of FT (particularly concerning its “alternative” role).

The rather market-oriented FTSEs were relatively homogeneous in terms of the logics guiding their practices. In the rather movement-oriented FTSEs, and in those combining the two logics, there was much more heterogeneity concerning the way of transforming the market (for instance, by collaborating with or confronting mainstream businesses). Let us now explore the link between the logics of social innovation and the organizational form.

The first, movement-oriented pattern was mainly found in volunteer-based nonprofit or cooperative FTSEs. These FTSEs were generally pioneers in FT, despite a few exceptions of recently created worldshops and other volunteer-based FTSEs (particularly in Italy). Most of the leaders of these FTSEs considered the choice of a “non-business” form as taken-for-granted, given the primarily socio-political goals. The economic activity was important, but it seemed clearly integrated in a broader socio-political context. As a result, these FTSEs had a commercial activity with a relatively low turnover and profitability compared to the number of volunteers and employees. The typical case was that of worldshops in which the sales of the products were closely linked to –and sometimes instrumental to– the education and advocacy goals. In volunteer-based importing FTSEs, the partnerships with the producers were presented as the concretization of a primarily political project. The volunteer-based governance was based on democratic representation much more than expertise, which resulted in larger and more complex governance structures. In certain FTSEs such as Oxfam-Magasins du Monde in Belgium, the creation of a volunteer-based democratic movement was precisely presented as one of the main missions. The education and advocacy activities were funded by specific incomes (subsidies and/or gifts) but they were often also “cross-subsidized” by the sales of the products. The commercial activity was thus not a goal on its own but rather a tool to serve the social and political goals.

The second pattern was mainly found in the first two types of FTSEs (individual and business-form) as well as in certain multi-stakeholder cooperatives and businesses. The leaders of these FTSEs often presented the economic performance as a means to provide more volume and thus more development to the producers –the same rationale used by labelers and promoters of the mainstreaming of FT. Profitability was justified by the need to sustain the social mission on the long term. This translated into business legal forms, considered as taken for granted and necessary to signal their logics of efficiency and professionalism toward economic partners. The managerial governance was also guided by efficiency concerns: several business leaders considered that democratic, multi-stakeholder schemes necessarily hindered economic decision-making. Other business-form FTSEs, however, included NGOs, public representatives, consumers and producers in their governance structures to reinforce their social trustworthiness and impact (Cafédirect in the UK, Citizen Dream in Belgium, Soli’gren in France, etc.). It is worth noting that several leaders acknowledged the importance of political activities at the movement’s level, but did not see it as a goal for their own FTSE. Certain of these leaders mentioned that they indirectly contributed to education and advocacy

through the participation to a network24 or through a more personal –rather than organizational– involvement25. Even in that case, their stand was more often oriented toward an improvement –rather than a transformation– of the market system.

Finally, the third pattern was particularly found in multi-stakeholder groups and cooperatives, but also in a minority of individual and business-form FTSEs. These two families of FTSEs differed, however, in the way in which the two types of social innovation were dealt with. In multi-stakeholder cooperatives and groups, the two logics were relatively clearly separated from each other. The group structures were specifically designed to this end, with a specialization of legal forms: the nonprofit entity dealing with socio-political issues and the cooperative or business entity focused on the economic activity. The governance structures were in some cases separated to attract experts in both domains. In other cases, there were two disctinct General Assemblies but the Board remained common to ensure coordination between the two units. In several cases (e.g., Traidcraft, Oxfam-Wereldwinkels), a common leader was appointed for the whole group. Most of the group structure FTSEs elaborated relatively complex organizational forms reflecting both a specialization in two distinct missions (with the social mission shared among the two entities) and a coordination of the units. Indeed, coordination appeared particularly crucial to deal with the possible tensions inherent to the distinct missions (for instance, between the business part negotiating with corporations and the nonprofit part campaigning against these corporations).

The combination of the two logics of social innovation was also observed in certain business-form and individual FTSEs, but then in a different, much more integrated manner. A good example is provided by the members of the Minga network in France. These FTSEs were characterized by both clear business forms and orientations (market), and by a strong “alternative” political agenda (movement). This translated into a radical opposition to both volunteer-based FTSEs such as Artisans du Monde (because of the presence of volunteers and the NGO-like, non-professional functioning) and to labels (Max Havelaar) and FT businesses engaged in the mainstream. Minga promotes a small and local approach to FT, based on personal relationships and fairness along the whole supply chain –reason for which the presence of FT in the supermarkets is seen as totally “heretic”. FTSEs members of Minga in the sample involved all their employees in such combination of commercial dynamics and political activity. I found a similar approach in FTSEs such as One Village in the UK.

This example of “political businesses” is interesting because it shows that the organizational form is insufficient to signal on its own a particular social innovation. Organizational forms should rather be considered as vehicles that allow for –but do not determine– certain types of social innovation, while leaving latitude in the way in which such an innovation can be interpreted and implemented. The following table summarizes how the logics of social innovation differ with the organizational forms.

24 Certain networks are engaged in campaigning (e.g. city-level networks in Rome and Lyon), while others are a

place in which different types of FTSEs can share experiences and collaborate (e.g. Belgian Fair Trade Federation and UK Fair Trade Leaders’ Forum).

25

Table 2: Social innovation and organizational form

Type 1 Type 2 Type 3 Type 4 Type 5 Legal form Individual Business Nonprofit (or

cooperative)

Cooperative Hybrid

Governance Managerial (exceptions of multi-stakeholder models)

Volunteer-based

Multi-stakeholder

Examples Esprit Equo Satya-Pure Elements CitizenDream Saldac Oxfam-MDM Ayllu Pangea-NT Soli’gren Oxfam-WW MMH-MFT Traidcraft Dominant logics Market-oriented Market-oriented or hybrid Movement-oriented Generally hybrid Economic activity

Central Central (but meaning varies) Tool to achieve socio-political goals

Central Central (for business entity)

Social mission

Achieved through economic performance

Vector for political message

Shared between nonprofit and business entities

Education &

advocacy Generally not explicit

Minority: central and integrated in the business

High and explicitly handled

Depends Central (for nonprofit entity)

4. Discussion

Let me briefly suggest three theoretical approaches that could enable interpreting these findings.26

New institutional economics

Based on the work of Coase (1937), who first opened the “black box” of organizations previously ignored by the traditional economic analysis, a whole stream developed from the 1970s through several theories such as transaction cost theory (Williamson, 1979). From an economic neo-institutional perspective, organizations adopt the institutional arrangements that allow them to minimize the transaction costs. These costs will vary with the nature of the “goods” produced by each organization (classical “private goods”, “public” or “quasi-public” goods, “trust goods”, etc.). Organizational forms should thus be interpreted through their assets for producing particular goods better than others.

But which “goods” are produced in the context of FT? We may distinguish at least three. If we isolate the “physical” or “observable” part of a FT product, we find a classical private good. Similarly to any consumption good, a FT banana, bottle of wine or piece of handicraft

26

benefits to the purchaser who has paid for it. Particular to FT, however, is the fact that the conditions under which the good has been produced matter quite a lot. The consumers do not buy only a banana: they also “buy” the guarantee that the producers have received a fair price and fair trading conditions (prefinancing, long-term relationship, etc.). Nevertheless, such a guarantee is only a promise: the consumer cannot verify whether the organization selling the product has really implemented what it announces. Part of the FT product can thus be defined as a trust good27. Finally, consumers may also “buy” the project of making trade fairer, through regulation, education and advocacy. These elements benefit the society as a whole and can thus be described as a (quasi-) public or collective good28. To summarize, following Becchetti & Rosati (2005) or Balineau & Dufeu (Balineau & Dufeu, forthcoming), we can see FT as a “bundle of characteristics”. In this perspective, if FTSEs adopt various forms, it is because they focus on different characteristics of this bundle. In terms of social innovation, the focus on prívate good production corresponds to the “market-based” orientation, while the focus on public good production is closer to the “movement-based” orientation.

Using transaction cost analyses, nonprofit organizations appear well equipped for the production of trust29 and public30 goods (e.g., Hansmann, 1980; Krashinsky, 1986). Through a number of organizational features (nondistribution of profit, ability to raise non-market resources, etc.), reinforced by the volunteer-based governance, they seem naturally closer to the “movement-oriented” social innovation. It is thus logical that FT pioneers seeking to build a movement able to influence consumption habits and mainstream trading practices chose the nonprofit, volunteer-based form. Such a form was a signal of trustworthiness with regard to the announced social mission and a tool to raise the resources needed by the political activity. However, being restricted in their access to capital and in the incentives for economic performance (Gui, 1987; Hansmann, 1996), nonprofits wishing to develop the economic activity (i.e., to increase their market orientation) had to find other institutional arrangements allowing this. The emergence of cooperative FTSEs and group structures may thus be seen as a response to such a need. More recently, newcomer FTSEs focusing on private good production (market orientation) have logically chosen forms allowing this (individual, managerial business or cooperative). Moreover, while the “trust-giving” nature of the organizational form was important in the beginning of FT, the emergence of a label and of several networks such as the WFTO reduced such importance and allowed any organizational form to engage in FT.

From this perspective, the diversity of organizational forms corresponds to a certain distribution of roles according to the nature of the goods produced. This is coherent with

27 A trust good is characterized by an information asymmetry between the buyer and the provider, which disables

the buyer to assess the quality of the good (Milgrom & Roberts, 1992)

28 It is not possible to exclude people from the consumption of the good (non-excludable characteristic), and the

consumption of one unit does not reduce the availability of the good for other people (non-rival characteristic) (Milgrom & Roberts, 1992)

29

Through the trust-giving nature of the “nondistribution constraint”, i.e., the prohibition to distribute net earnings, which is supposed to eliminate opportunism linked to the information asymmetry characteristic of the production of trust goods (Gui, 1987; Hansmann, 1980; Krashinsky, 1986).

30 Through their access to non-commercial resources (subsidies, gifts, voluntary work) and their ability to avoid

Handy (1997), who suggests that business companies will focus on the production of private goods with an observable quality, while nonprofit organizations will be preferred for the production of less easily observable goods such as trust and public goods. This argument could be applied to explain the existence of groups gathering both entities. From a transaction cost perspective, the group structure is particularly suited for the combined production of public good (movement orientation through the nonprofit entity) and private good (market orientation through the business entity).

In spite of these useful insights, there are several exceptions that challenges the neo-institutional economic arguments. For instance, why do certain FTSEs with a similar organizational form (e.g., cooperatives or businesses) have very different logics of social innovation? And why do FTSEs with similar logics sometimes adopt different forms? Moreover, neo-institutional economics do not explain why business forms where adopted by FTSEs even before the emergence of the label (problem of trustworthiness) and with logics including, at least partially, a movement, public good orientation. One answer is to suggest that social enterprises such as FTSEs constitute a new institutional arrangement that is very different from both traditional nonprofits and “for-profit” companies (Bacchiega & Borzaga, 2001). But even when the link between the types of goods produced and the organizational form is confirmed, neo-institutional economics say little about why FTSEs focus on certain goods over others. Other theoretical approaches are thus required for a more complete analysis.

Neo-institutional theory

Unlike neo-institutional economists, the authors of the “New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis” (as named by Powell & DiMaggio, 1991) see the institutions in a much broader sense, as social and historical constructions which have progressively rendered certain forms and behaviors as taken for granted (Powell & DiMaggio, 1991). Introducing the view of organizations as “dramatic enactments of the rationalized myths pervading modern societies”, Meyer and Rowan (1991, p. 47) contest the dominant functional view of organizations by showing that “structures can become invested with socially shared meanings, and thus, in addition to their 'objective' functions, [...] serve to communicate information about the organization to both internal and external audiences” (Tolbert & Zucker, 1996, p. 171). As organizations are shaped by institutional pressures, they tend to resemble each other through coercive, mimetic and normative influences (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). In the context of FTSEs, mimetic or normative pressures may lead to favoring particular logics of social innovation. But other pressures (for instance by public authorities) may have nothing to do with these logics.

More fundamentally, the assumption of gradual isomorphism is at the opposite of the observation of organizational diversity among FTSEs. Several factors may explain this from a sociological neo-institutional point of view. A first possible explanation is that diversity is observed at the early stages of a field and that the field’s institutionalization progressively bringd isomorphism (Powell & DiMaggio, 1991). But this is inconsistent with the observation

that diversity in FTSEs’ forms has been increasing rather than decreasing over time. Another explanation is that institutional pressures in FT are weak or even non-existent. Indeed, with the exception of Italy, where the social cooperative form has been encouraged –or “induced” (Scott, 1991)– by public authorities lobbied by FT networks31, there is generally no legal framework or funding scheme specific to FTSEs that would force the latter to be structured similarly. Moreover, concerning normative pressures, we could consider FT was precisely launched in an “institutional void” located between the market and civil society (Renard, 2003). As a result, there were no direct normative pressures on FT pioneers, which allowed for a diversity of forms escaping isomorphic pressures.

There were, however, indirect isomorphic pressures, first from development and advocacy NGOs, and, gradually, with the mainstreaming process, from the market. The persistent organizational diversity could thus be caused not so much by the absence but rather by the plurality of institutional (particularly mimetic and normative) pressures favoring either the movement or market orientations. While uniformity may exist because of imitation within specific networks (for instance Minga in France and Agices in Italy), there does not seem to be commonly recognized “success stories” that could be imitated by all FTSEs. My interviews with several leaders confirm that they diverged strongly about what they see as the model to be followed. Such divergences were often based on normative assesments (with given FTSEs depicted as “too market-oriented” or “too political”, or supporting producers in an “inappropriate way”).

The interviews confirmed the justifications of the organizational form (particularly the legal form) on the basis of given “myths” (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). Leaders of volunteer-based FTSEs often referred to values of democracy and solidarity, insisting on the coherence between their democratic form and the requirements for producer groups as well as the political goals of FT. In pioneer FTSEs having evolved into multi-stakeholder cooperatives or groups, these values were not denied but they were accompanied by a strong insistence on the need to professionalize and to increase the market orientation. In group structures, the creation of a specific and relatively autonomous trading company was presented as a response to such a need. Each entity may thus be seen as pursuing logics of social innovation that embody specific institutional demands, with complementarities but also tensions. The multiple stakeholders are among the most concrete channels through which these demands are integrated into the organizational context (Cornforth, 2003). Indeed, in several cases of FT group structures, the institutional pressures were concretely relayed by particular stakeholders on the Board (for instance, volunteers and NGOs versus investors and business experts). This is a clear illustration of the organizational implications of “institutional pluralism” (Kraatz & Block, 2008).

While the interviews confirmed the growing trend towards professionalism and market orientation, even in the nonprofit structures (Dart, 2004), it is worth noting that such an

31 The Italian network Agices has been particularly involved in lobbying public authorities to accept FT as a field

for social cooperatives and to promote “not-for-profit” (nonprofit or cooperative) forms for FTSEs. This could be reinforced by the law on FT that has been elaborated from 2005 –but has not yet been adopted.

orientation may take several meanings and be implemented differently. A major difference appeared between the large FTSEs collaborating with mainstream businesses, and the small entrepreneurial venture. The latter regularly criticized the bureaucratic and impersonal trends of large and old FTSEs, putting forward their small, flexible and innovative form as more appropriate to support producers in a personalized way. For some of these leaders, smallness and innovation were suited for their market orientation, which they considered in line with mainstream businesses involved in FT. For others, though, particularly in the Minga network, smallness was a political choice which they favored at all the levels of the supply chain, through working for instance with small local transformation companies. This corresponded to an original embedding of a clear market orientation (they rejected voluntary work and subsidies) in a political project hostile to mainstream businesses. This shows how commonly mentioned values such as “professionalism”, and similar forms (e.g. the managerial business), can be interpreted very differently (Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006), demonstrating the ability of FTSEs to shape and give meaning to their form and practices.

Institutional entrepreneurship

In the previous analysis, I have limited the scope to the arguments of the “early” neo-institutional authors. These arguments are rather deterministic concerning organizational forms and behavior and say little about where the institutional pressures come from. Drawing on the intuitions of DiMaggio (1988) and Scott (1991), a growing number of scholars has tried to introduce “agency” –the capacity to act– in neo-institutional theory by examining how actors shape institutions. This is referred to as “institutional entrepreneurship” (Hwang & Powell, 2005; Leca et al., 2008; Maguire et al., 2004) or “institutional work” (Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006). However, viewing organizations as simultaneously embedded in their environment and capable of shaping such an environment leads to a paradox –the paradox of “embedded agency” (Battilana & D'Aunno, 2009; Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006).

Institutional entrepreneurship may help us to characterize organizational diversity not only as a reflection of a multidimensional good production or of institutional pluralism, but as a result of deliberate differentiation processes. This explains why this approach is of special interest in research on social entrepreneurship (Mair & Marti, 2006; Nicholls, forthcoming). While Nicholls and Cho (2006) have emphasized the “disruptive” ability of social enterprises as a whole to escape isomorphic pressures from civil society and the market, I examine such ability for particular FTSEs regarding the isomorphic pressures within the FT sector in given regions. I look at how these FTOs seek to capture and secure power and legitimacy32 through the promotion of particular logics –and forms bearing these logics– over others.

In the previous analysis, I mentioned the role of the Italian network Agices in promoting the social cooperative as a symbol for a non-business, alternative form. It is important to

32

The type of legitimacy that is referred to is close to what Suchman (1995) calls normative “structural legitimacy”: “audiences see the organization as valuable and worthy of support because its structural characteristics locate it within a morally favored taxonomic category” (Suchman, 1995:581). In other words, “[t]he structurally legitimate organization becomes a repository of public confidence because it is ‘the right organization for the job’” (581).

emphasize that such a network was created by a number of pioneer FTSEs (such as Pangea-Niente Troppo in Rome) that shaped the network so as to legitimize their own form and impose it to others through the membership criteria. The normative environment hostile to business-form FTSEs is thus the result of “institutional strategies”33 of coalitions of FTSEs. This context makes it difficult for “non-aligned” FTSEs to survive and develop. I found an example of such a “black swan” through Esprit Equo, a small Roman business-form FTSE that actively struggled for legitimacy, inter alia through developing import partnerships with WFTO members in Italy and abroad. Esprit Equo, however, did not manage to see its organizational form recognized by Agices and other networks, which, according to the founder, hinders its development.

A similar case is that of Citizen Dream, a Brussels-based FTSE that, from its creation in 1999, faced criticism from certain pioneer Belgian FTSEs such as Oxfam-Magasins du Monde. Through WFTO membership and support by other established FTSEs, Citizen Dream gained its “right” to exist as a FT actor and showed to potential social entrepreneurs that FT could also be undertaken with a business form and a market logic. Although this FTSE ultimately collapsed, it paved the way for a new generation of business-form FTSEs, besides –and not against– other models. The recognition and the coexistence of different models of FTSEs in Belgium were institutionalized through the recent creation of the “Belgian Fair Trade Federation”. To impose their own form and logics, however, certain FTSEs engaged in de-legitimizing the previous arrangement and by depicting their own as superior. As already mentioned, the members of the Minga network are opposed to both volunteer-based, and business-form FTSEs active in mainstream distribution channels. Their opposition translated into books and press releases that successfully diffused Minga’s views among FTSEs and public opinion in general, confirming the “potential for institutional entrepreneurship on the part of relatively small, peripheral or isolated actors” (Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006, p. 249). Such an advocacy and theorizing work convinced a growing number of FTSEs and obliged established actors such as Max Havelaar and Artisans du Monde to spend much energy in defending their own forms and practices.

All these examples show that FTSEs are much more than passive reflections of the institutional setting: rather, in a context of institutional pluralism, FTSEs may create new models out of several “rationalizing myths” at their disposal, select justifications out of these myths and diffuse the appropriateness of their institutional arrangement through a number of strategies such as theorization and networking (Kraatz & Block, 2008; Maguire et al., 2004). The constitution of networks among FTSEs and, more generally, among social enterprises, is a crucial process for understanding how certain forms and logics gradually become dominant.

33

As defined by Lawrence and Suddaby (2006, p. 224), the concept of institutional strategy “describes the manipulation of symbolic resources, particularly membership access and the definition of standards, which are key aspects of the type of work necessary in the early stages of an institutionalization project”.

5. Conclusion

This article has tried to better understand the organizational diversity in the FT sector and its implications in terms of social innovation. My study on 57 FTSEs in four European regions has highlighted the existence of diverse legal forms and governance models. The combination of these two elements leads to five categories of organizational forms. These categories seem to be linked, at least to a certain extent, to different logics of social innovation. Volunteer-based FTSEs are generally more focused on education and advocacy, being thereby closer to the “movement-oriented” avenue to social innovation. Most managerial business forms focus on the market orientation as the way to achieve the social mission. These two logics are often combined in the context of multi-stakeholder cooperatives and groups. However, nuances exist and certain forms appear as “vehicles” that may be invested of different logics (with, for instance, certain business-form FTSEs that are very radical and movement-oriented).

I suggested three theoretical frameworks to interpret the diversity of organizational forms and its correspondence with the logics of social innovation. Neo-institutional economics viewed organizational diversity as the result of the production of different types of goods within the “FT bundle”. New institutionalism in organizational analysis emphasized organizational diversity as the result of weak and multiple institutional logics. And institutional entrepreneurship highlighted the ability of FTSEs to shape the environment in a way that legitimizes their own form and logics. These three frameworks, although relying on different assumptions and understandings of an “institution”, can be used in a complementary way: the first one focusing on organizational forms as functional, asset-providing arrangements; the second one examining the organizational forms and logics as resulting from institutional pressures; and the third one seeing organizational forms as strategic tools in the process of institutional shaping.

This study entails several limitations. The first one is that “organizational form” was restricted to the legal form and the governance model, leaving other aspects aside (such as the architecture or design). Moreover, the sole interview with the leader restricted the insights concerning certain organizational dynamics and interpretations. In many cases, however, the documental analyses and the references about the FTSE in other studies enabled a more global picture. The third limitation is that study was carried out in Europe (and not in the South), thereby lacking information about differences in the concrete implementation of the social mission. The latter was rather examined through the particular articulation of market and movement orientations. Finally, while the link between organizational forms and logics of social innovation has been explored in depth, it is not yet clear, even using the three theoretical approaches, whether the organizational form should be seen as a consequence or as a cause of the orientations regarding the type of social innovation. I have left the sense of the causal relationship open to interpretation precisely because I think that there may be mutual influences between these two elements.

In spite of these limitations, I developed an analysis which I hope will enrich both the academic analysis and the practice of FT and social enterpreneurship in general. First, from a

normative point of view, I would like to stress the importance of the coexistence of organizational forms. The ability of social enterprises to resist isomorphic pressures underlined by Nicholls and Cho (2006) is an asset that provides legitimacy in the eyes of multiple constituents. The coexistence of different organizational avenues to social innovation is likely to attract a much broader array of organizational actors and supporters than if there was only a single model: individual entrepreneurs, ethical investors, groups of citizens, etc. But such diversity is not without tensions, both among and within organizations. In local contexts, powerful coalitions of social enterprises or external actors (typically the State or large market players) are likely to impose one model over the others.

Secondly, as I have tried to show, the coexistence of different forms in social entrepreneurial fields such as FT does not mean that these forms do not matter any more. While the form is only one element of the organizational identity and the latter should not be restricted to the former, as former pieces of literature have tended to do34, it is a necessary element that may underlie certain types of social innovation over others. The literature on social enterprise should thus not ignore the organizational form issues only because the focus is on the process of social innovation. Such an innovation, as this study has shown, can be translated into a variety of organizational forms, which are not anecdotic regarding the articulation of the economic activity, the social mission and the possible political message. Finally, the view of social enterprises as “new institutional arrangements” should lead to deepening the theoretical frameworks adopting an institutional perspective. While the three approaches I suggested have already been used in the context of social enterprise, it is particularly fruitful to combine their insights, an exercise that remains rare at this date (Schneiberg, 2005). Social enterprise is too rich and innovative to be captured only through one theoretical lens.

References

Alter, S. K. (2006), “Social Enterprise Models and Their Mission and Money Relationships”, in A. Nicholls (Ed.), Social Entrepreneurship. New Models of Sustainable Social Change, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 205-232.

Austin, J., Leonard, H. B., Reficco, E. & Wei-Skillern, J. (2006a), “Social Entrepreneurship: It Is For Corporations, Too”, in A. Nicholls (Ed.), Social Entrepreneurship. New Models of Sustainable Social Change, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 169-204. Austin, J., Stevenson, H. & Wei-Skillern, J. (2006b), “Social and Commercial

Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both?”, Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 30:1, 1-22.

Bacchiega, A. & Borzaga, C. (2001), “Social Enterprises as Incentive Structures”, in C. Borzaga & J. Defourny (Eds.), The Emergence of Social Enterprise, Routledge, London and New York, 273-295.

Balineau, G. & Dufeu, I. (forthcoming), “Are Fair Trade goods credence goods? A new proposal, with French illustrations”, Journal of Business Ethics, special issue on Fair Trade in different national contexts.

Battilana, J. & D'Aunno, T. (2009), “Institutional work and the paradox of embedded agency”, in T. B. Lawrence, R. Suddaby & B. Leca (Eds.), Institutional Work, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

34