THE BOUNDARIES OF CHARITY

The Impact of Ethnic Relations on Private Charitable Services

for Quebec City’s English-speakers, 1759-1900

Thèse

Patrick Donovan

Doctorat en histoire

Philosophiae Doctor (Ph.D.)

Québec, Canada

© Patrick Donovan, 2019

THE BOUNDARIES OF CHARITY

The Impact of Ethnic Relations on Private Charitable Services

for Quebec City’s English-speakers, 1759-1900

Thèse

Patrick Donovan

Sous la direction de :

Donald Fyson, Directeur

Johanne Daigle, Co-directrice

RÉSUMÉ

Cette thèse porte sur les organismes privés de bienfaisance s’adressant aux anglophones de Québec entre 1759 et 1900. L’étude offre un portrait des différents organismes, des besoins auxquels ceux-ci répondent et des lacunes dans le réseau d’assistance. Au cours de la période étudiée, le rôle des organismes privés d’assistance s’accroît, alors que celui de l’État décroît. La compassion envers les pauvres augmente, engendrant de nouvelles organisations charitables pour les populations les plus marginalisées. En dépit de ce fait, la prison sert souvent de refuge pour compenser les failles dans le réseau.

Cette thèse montre plus précisément comment les relations interethniques façonnent le réseau d’assistance aux pauvres. Tout au long du demi-siècle suivant la Conquête, dans la ville de Québec, les autorités britanniques en poste soutiennent l’infrastructure charitable catholique établie lors du régime français, fait inusité dans l’Empire britannique. Après 1815, époque marquée par une forte immigration de Grande Bretagne et d’Irlande, de nouvelles associations bénévoles laïques voient le jour. La cooperation entre élites de différents groupes ethnoreligieux existe dans plusieurs associations. Les divisions ethniques s’intensifient toutefois entre 1835 et 1855, un changement engendré par une convergence de facteurs, dont la défaite du républicanisme patriote, un accroissement de la pratique religieuse, la mise en place d’écoles confessionnelles et l’émergence d’un nationalisme irlando-catholique plus robuste à la suite de la grande famine. Dans la deuxième moitié du XIXe siècle, le paysage de l’assistance se divise clairement entre trois réseaux parallèles : un pour les catholiques francophones, un pour les irlando-catholiques anglophones et un pour les protestants anglophones. Le Saint Bridget’s Asylum et le Ladies’ Protestant Home, fondés dans les années 1850, constituent des points d’ancrage forts pour ces réseaux. Les rares tentatives de remise en question des frontières ethniques se soldent par des tensions accrues et même de la violence. Malgré ces divisions, il existe un respect mutuel pour ces frontières dans les trois communautés de la ville, ce qui est inhabituel dans la plupart des villes nord-américaines.

ABSTRACT

This thesis examines the private charitable sector for English-speakers in Quebec City from 1759 to 1900. It provides an overview of poor relief associations, the needs they addressed, and the gaps that remained. The role of private charities increased over the period studied, and that of the state decreased. Compassion toward the poor also increased, leading to new types of charitable organizations for the underclass. Despite this, the prison system served as a refuge to fill gaps in the private charitable sector.

More specifically, this study demonstrates how changes in ethno-religious relations shaped the charity network. In the first half century after the Conquest of Quebec, British authorities supported the Catholic charitable infrastructure established during the French regime, which was unusual within the British Empire. After 1815, as immigration from Britain and Ireland increased, lay private voluntary associations emerged, including many that involved elite cooperation across religious and linguistic lines. Instances of cooperation decreased from 1835 to 1855 due to rising ethnic boundaries caused by the defeat of Patriote republicanism, an increase in religious practice, the establishment of separate confessional schools, and a new type of Irish-Catholic nationalism following the Great Famine. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the private charitable sector became sharply divided into three parallel networks with hardly any overlap: one for Francophone Catholics, one for English-speaking Irish Catholics, and one for English-speaking Protestants. Two core institutions founded in the 1850s, Saint Bridget’s Asylum and the Ladies’ Protestant Home, cemented the divide. Rare attempts to challenge these boundaries resulted in tension and even violence. Despite these divisions, there was a greater mutual respect of established boundaries among communities than in most North American cities.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

RÉSUMÉ ... iii

ABSTRACT ... v

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... vii

LIST OF FIGURES ... ix

LIST OF TABLES ... xi

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS / REMERCIEMENTS... xiii

INTRODUCTION ...1

Definition of problem ...1

Historiography ...9

Sources and Methodology ... 25

Structure and Organization ... 30

1. POST-CONQUEST CONTINUITY: CHARITABLE NETWORKS BEFORE 1815 ... 33

1.1. Family and Church Networks ... 33

1.2. Religious Institutions: Hôtel-Dieu and Hôpital Général ... 35

1.3. The Role of Mutual Aid Societies ... 42

1.4. Poverty and the Criminal Justice System ... 43

1.5. Conclusion ... 45

2. WORKING TOGETHER: CHARITABLE NETWORKS FROM 1815-1835 ... 48

2.1. Factors Increasing Social Service Needs After 1815 ... 48

2.2. New Typologies, Separate Spheres, 1815-1835 ... 55

2.3. Aid to New Mothers: The Female Compassionate Society ... 64

2.4. Men’s Voluntary Work: Sorting out the Adult Poor ... 67

2.5. Early Protestant Homes: Anglicans at the Forefront ... 91

2.6. Early Homes for Irish Catholics ... 99

2.7. Irish Catholic Charitable Initiatives ... 106

2.8. Conclusion ... 108

3. THE QUIET DEVOLUTION, 1835-1855 ... 111

3.1. Rising Ethno-Religious Boundaries (or the Quiet Devolution) ... 111

3.2. Structural Changes and New Additions ... 144

3.3. National Societies: the Saint George’s, Saint Andrew’s and Saint Patrick’s Societies... 150

3.4. Catholic Male Volunteerism and the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul ... 169

3.5. Expansion of Women’s Charitable Endeavours ... 182

3.6. Charity and the State ... 197

3.7. Conclusion ... 202

4. “GOOD FENCES MAKE GOOD NEIGHBOURS”: 1855-1900 ... 205

4.1. Anglophone Decline and Consolidation of the Charitable Network ... 206

4.2. A Cohesive Irish Catholic Charitable Network ... 213

4.3. Evangelicalism and its Impact on the Protestant Charitable Sector ... 246

4.4. Vagrants and the Underclass: Between the Asylum and the Gaol ... 268

4.5. Challenging Boundaries, or the Salvation Army Wars of 1886-1887 ... 283

4.6. Conclusion ... 297

LIST OF FIGURES

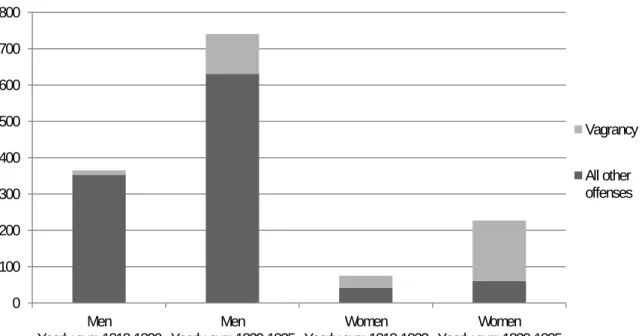

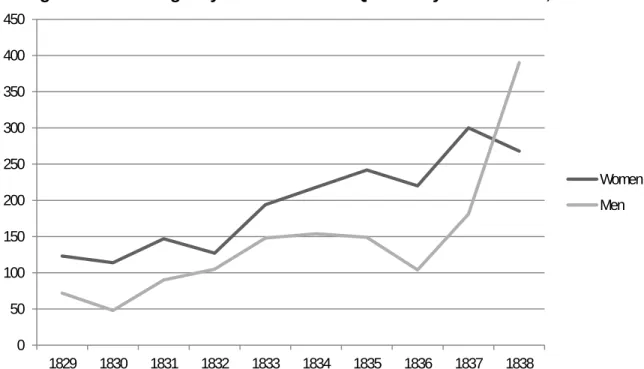

Fig. 1: Proportion of Vagrancy Convictions at the Quebec City Common Gaol, Yearly Averages for 1818-1822 and 1829-1835 ... 90 Fig. 2: Number of Vagrancy Convictions at the Quebec City Common Gaol,

1829-1838 ... 91 Fig. 3: Total Population of Quebec City and Montreal, 1852-1901 ... 206 Fig. 4: Total Population of Quebec City by Ethnic Group, 1852-1901 ... 208 Fig. 5: Quebec City’s Population by Percentage of Ethnic Groups, 1852-1901 ... 209 Fig. 6: Number of Residents at Saint Bridget’s Asylum (Excluding Staff),

1856-1905... 218 Fig. 7: Number of residents at the Finlay Asylum (Excluding Staff), 1865-1894 ... 248 Fig. 8: Number of residents at the Ladies’ Protestant Home (Excluding Staff),

1859-1905 ... 255 Fig. 9: Comparison of the Number of Residents at the Ladies’ Protestant Home

and Saint Bridget’s Asylum, 1859-1905 ... 256 Fig. 10: Relative weight of Quebec City’s Protestant and English-speaking

Catholic Populations, 1852-1901 ... 257 Fig. 11: Evolution of the City Mission Movement in Quebec City ... 262 Fig. 12: Vagrancy Committals by Gender at the Quebec City Gaol, 1830-1888 .. 271 Fig. 13: Percentage of Committals for Vagrancy by Gender at the Quebec City

Gaol, 1850-1888 ... 272 Fig. 14: Proportion of Anglophones among the Good Shepherd Sisters in

Quebec City, 1851-1891 ... 276 Fig. 15: Proportion of Anglophones among Penitents and Orphans in the Good

LIST OF TABLES

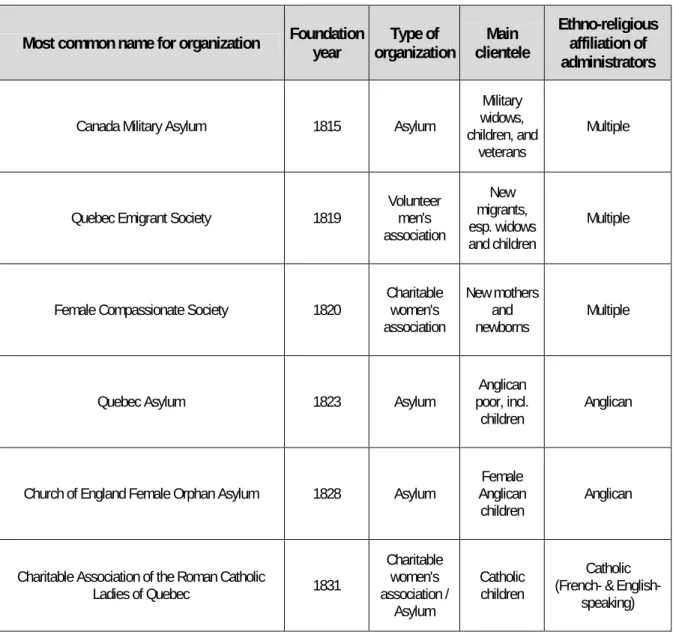

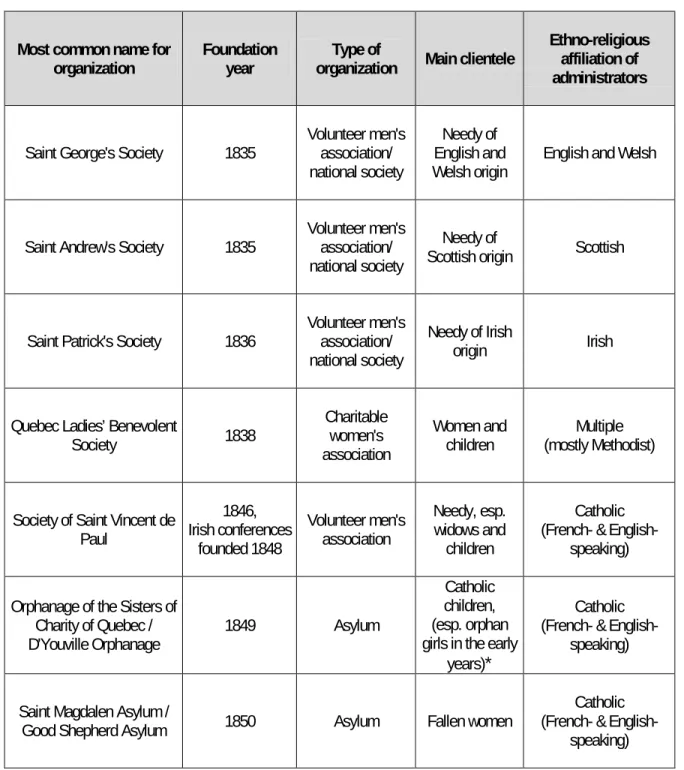

Table 1: Quebec City Population by Ethnic Origin, 1805-1842 ... 49 Table 2: Major Private Charitable Organizations Providing Significant Services

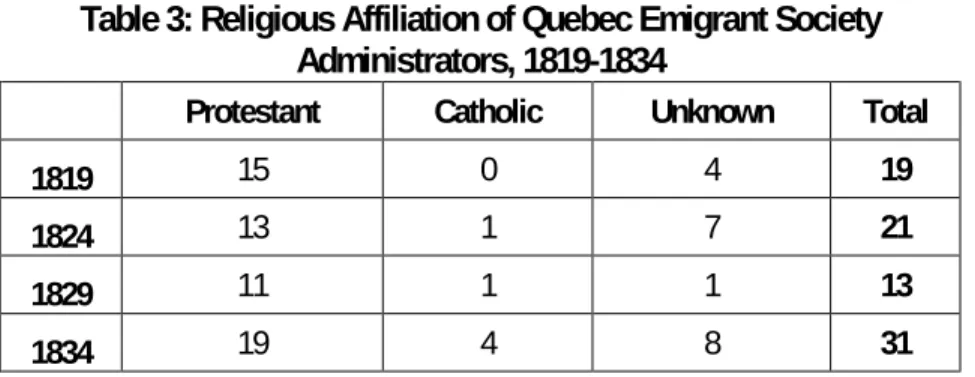

to Quebec City's English-speakers Founded Prior to 1835 ... 56 Table 3: Religious Affiliation of Quebec Emigrant Society Administrators,

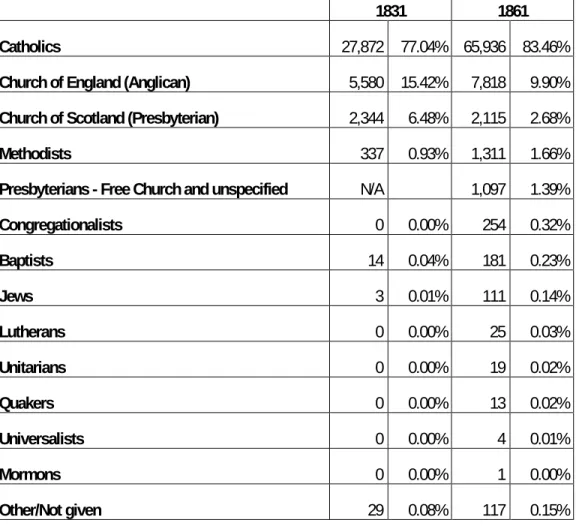

1819-1834... 73 Table 4: Population by Religious Affiliation in Quebec (City & County), 1831,

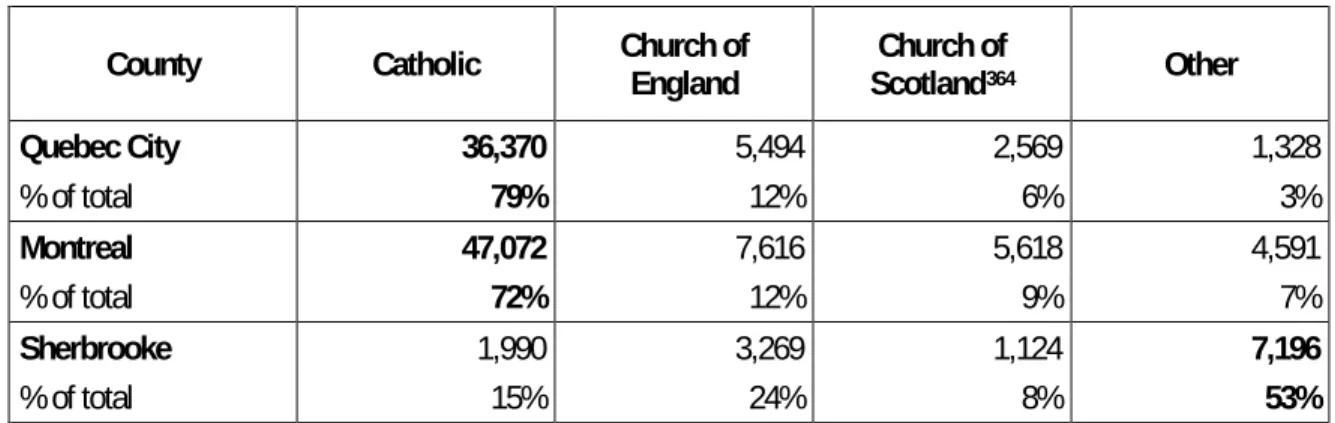

1861... 125 Table 5: Population by Religious Affiliation in Selected Regions of Lower

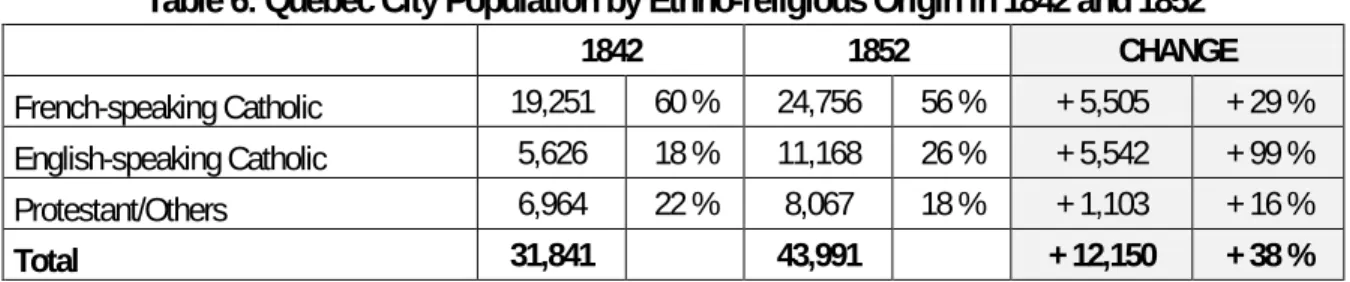

Canada, 1844 ... 127 Table 6: Quebec City Population by Ethno-religious Origin in 1842 and 1852 ... 135 Table 7: Occupational Structure of Adult Male Population by Ethnic Group in

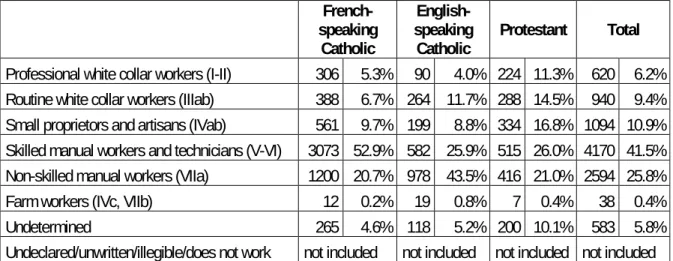

Quebec City (EGP2), 1852 ... 137 Table 8: Major Private Charitable Organizations Providing Significant Services

to Quebec City's English-speakers Founded Between 1835 and 1855 ... 149 Table 9: Major Private Charitable Organizations Providing Significant Services

to Quebec City's English-speakers Founded Between 1855 and 1900 ... 212 Table 10: Place of Birth of Adult Residents at Saint Bridget’s Asylum,

1856-1915... 220 Table 11: Proportion of Catholics among English-, Scottish-, and Irish-origin

Population in Quebec City, 1871, 1901 ... 266 Table 12: Proportion of Committals by Voluntary Confession at the Quebec

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS / REMERCIEMENTS

This thesis would not have been possible without the generous financial support of the Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and the Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Société et Culture (FRQSC). Thanks also to Jeffery Hale Community Partners, the Équipe de recherche en partenariat sur la diversité culturelle et l’immigration dans la région de Québec (ÉDIQ), and the Centre interuniversitaire d’études québécoises (CIEQ) for contracts that allowed me to pursue research for this thesis. Moreover, research on English-speaking organizations in Quebec City conducted for the Morrin Centre, and financed by the Department of Canadian Heritage, helped me situate my results in a broader context.

Thanks to my thesis advisor Donald Fyson for the quality of his supervision, his rigorous attention to details, his novel suggestions for sources, and his easygoing attitude to the inevitable delays that occurred. Merci aussi à ma co-directrice Johanne Daigle, qui m’a aidé à bien définir mon sujet, à mieux comprendre le domaine de l’assistance et qui partageait bien son enthousiasme contagieux pour ces recherches. C’était un immense plaisir de travailler avec vous deux et j’espère qu’on pourra collaborer davantage à l’avenir.

This thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of staff at BAnQ’s archive centre in Quebec City, especially Rénald Lessard and Christian Drolet. Thanks also to Joe Lonergan for facilitating access to the Irish Heritage Quebec archives, and to Richard Walling for helping me obtain access to the Saint Patrick’s Parish archives. James Sweeny was an invaluable help in unearthing unexpected treasures at the Quebec Diocesan Archives in Sherbrooke.

I’d also like to thank the many scholars that gave me useful advice, support, and opportunities along the way, especially Lorraine O’Donnell, Brian Lewis, Chedly Belkhodja, Martin Pâquet, Janice Harvey, Brigitte Caulier, Martin Petitclerc, France

Parent, Louisa Blair, Alex Tremblay-Lamarche, Robert Grace, Simon Jolivet, Peter Toner, Rod MacLeod, and Marianna O’Gallagher.

Finally, thanks to my life partner Anne-Frédérique Champoux for regularly twisting my arm and putting up with my erratic sleep patterns throughout this process. Thanks also to my son Quentin Donovan for existing (even though his arrival on the scene halfway through my doctoral studies slowed me down considerably). Merci aussi à ma mère, Renée Lamontagne, qui me rappelait parfois qu’elle souhaitait me voir obtenir mon doctorat de son vivant : voilà, je l’ai!

INTRODUCTION

Definition of problem

La charité est universelle et ne distingue pas entre les souffrants . . . La misère seule est l'objet de nos recherches, et jamais nous ne distinguons entre Canadien Français, Anglais ou Irlandais.1

This quote, taken from the first report of Quebec City’s Society of Saint Vincent de Paul in 1848, suggests that charity is blind to ethnic divisions. At first glance, this seems sensible: a charitable mindset, one that is concerned for others, would seem to require a broad, compassionate, selfless spirit that is at odds with sectarianism. However, the real world rarely lives up to such ideals. Charity was not always guided by empathy, but also by concerns related to social order and public security. Some of those involved in charity work were also motivated by a personal desire for religious salvation. Moreover, volunteerism was not always entirely voluntary, as there was social pressure among the upper classes to engage in charity; many saw it as their duty. Charitable organizations struggled with limited resources and had to establish criteria to determine who received help and who didn’t. They distinguished between “deserving” and “undeserving” poor. They also drew distinctions along ethnic and religious lines.

In this thesis, I will examine ethno-religious issues within the charitable sector with two purposes in mind. First, I aim to provide a broad structural overview of Quebec City’s many private charitable associations targeting its English-speaking minorities over a period roughly spanning 140 years. Secondly, I will demonstrate that cooperation across ethno-religious lines within this sector decreased between the British Conquest and the turn of the twentieth century, and that rising ethno-religious boundaries were instrumental in structuring the network itself. Following the Conquest, the largely Protestant ruling authorities initially supported the

1 Recueil de la correspondance des conférences du Canada avec le Conseil général de Paris et des rapports

des assemblées générales, (Quebec: Société de Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, Atelier typographique de Léger

Catholic charitable infrastructure established during the French regime. As immigration increased after 1815, new charitable organizations were founded, including many that involved elite cooperation across ethno-religious lines. However, by the turn of the twentieth century, the private charitable sector had become sharply divided into three parallel networks with hardly any overlap: one for Francophones, one for Irish Catholics, and one for Protestants. These divisions were shaped by historical events taking place not only in Quebec, but elsewhere in North America and Western Europe. Although the Quebec City situation had its own specificities due in part to its unique demographic makeup, the exceptionalism and “bonententisme” often present in descriptions of ethnic relations in the city should not be overstated. The evolution described above was roughly mirrored in other northeastern cities such as Montreal and Boston. The same ethno-religious divisions also occurred in other civil society institutions.

Nineteenth-century Quebec City is an interesting and often overlooked laboratory for the study of ethnic relations. The city is overwhelmingly French-speaking today, and is arguably the least ethnically-diverse major city in Canada, but this was not always the case. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, Quebec was the major port of entry for migrants. By 1860, over 40% of the population was English-speaking,2 compared to fewer than 2% having English as a mother tongue today.3 Although the city’s minorities have received some scholarly attention, particularly the Irish Catholic minority, the way ethnic groups related to each other is rarely a primary concern.

2 There is no mother tongue data in the 1861 census. However, 43.6% of Quebec City’s population consisted of people who were neither Canadian natives of French origin, natives of France, or natives of Switzerland. See: Canada, Census of the Canadas 1860-61 (Quebec: S.B. Foote, 1863). Census manuscript databases for the same year show that 42.0% of the population was not of Francophone Catholic origin, based on origin data and surname analysis. See: Centre interuniversitaire d’etudes québécoises à l’Université Laval (CIEQ-Laval), “Population et histoire sociale de la ville de Québec (PHSVQ),” http://www.phsvq.cieq.ulaval.ca/

3 1.93% of the population listed English as a mother tongue in Quebec (Census Metropolitan Area) during the 2016 Census, or 15,270 people out of 789,355. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/

Montreal has been the focus of most studies dealing with urban ethnic relations in the province, yet Quebec City provides an interesting contrast. For one, it is the only major North American city where Francophones have always been a majority.4 Secondly, Quebec City experienced an important decline of its English-speaking Protestant and Irish Catholic minorities in the second half of the nineteenth century, whereas percentages in Montreal remained stable.5 Furthermore, Quebec City did not experience the significant influx of migrants from Southern, Central, and Eastern Europe that redefined and added complexity to ethnic relations in Montreal in the twentieth century. Studying how ethnic groups evolved in such a different environment leads to a more nuanced understanding of ethnic relations in the province and in North America as a whole.

Given that the charitable sector is situated at the hazy confluence of the social, medical, psychiatric, educational, religious, and criminal justice fields,6 it is important to clarify the limits of this study. My primary focus is on the major private charities that provided aid to a significant number of English-speakers. I include poor relief organizations that targeted abandoned infants, orphan and dependent children, needy unemployed or poor adults, and the indigent elderly. These include both outdoor relief groups that distributed aid, and indoor relief institutions that housed the needy. Hospitals are largely excluded, with some exceptions; the historiography of medicine is often considered separately, and this study is more interested in the social service dimension than in the health/medical one.7 I also

4 English-speakers formed a majority in Montreal between 1832 and 1867. See Gillian Leitch, "The Importance of Being English? Identity and Social Organisation in British Montreal, 1800-1850" (Ph.D., Université de Montréal, 2007), 75.

5 Ronald Rudin, The Forgotten Quebecers: A History of English-Speaking Quebec, 1759-1980 (Quebec: Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture, 1985), 179.

6 Louise Bienvenue, "Pierres grises et mauvaise conscience : essai historiographique sur le rôle de l'Église catholique dans l'assistance au Québec," Études d'histoire religieuse 69 (2003) , 12.

7 Exceptions are made for some early hospitals: the Hôpital Général, for instance, was more like a charitable home than a health care institution, and is described in detail in chapter 1.

For a recent overview of Quebec’s medical history, see: Denis Goulet and Robert Gagnon, Histoire de la

largely exclude the public network, which dealt more with delinquent children,8 criminals,9 and the insane,10 in part because these networks have been studied extensively elsewhere. However, given attitudes that tended to criminalize many innocent poor in the nineteenth century,11 I cannot entirely exclude the role of prisons as de-facto charitable institutions in Quebec City, especially considering the fact that they sheltered a disproportionate number of English-speakers. Sources relating to the gaol will therefore serve to show the insufficiency of the private network at different times. The primary focus of this study nevertheless remains the private network.

The period studied ranges from the British Conquest (1759) to the turn of the twentieth century (1900). The former year was chosen for obvious reasons, since Two hospitals specifically targeted English speakers in Quebec City: the Marine and Emigrant Hospital and Jeffery Hale’s Hospital. The former is dealt with in many general histories of health care and medicine in Quebec, including the study listed above. For more information on the latter, see Patrick Donovan, "L’hôpital Jeffery Hale : 150 ans de relations interethniques," Cap-aux-Diamants, no. 121 (2015), 25–28; Alain Gelly,

Centre Hospitalier Jeffery Hale, 1865-1990 / Jeffery Hale’s Hospital Centre, 1865-1990 (Quebec: Jeffery Hale’s

Hospital Centre, 1990).

8 The care of delinquent children was undertaken by reform and industrial homes. This separate network, which did not include institutions founded specifically for Quebec City’s English-speaking communities, has been studied extensively. See: Sylvie Ménard, Des enfants sous surveillance : la rééducation des jeunes

délinquants au Québec (1840-1950) (Montreal: VLB, 2003). For Quebec City, see: Dale Gilbert, "Dynamiques

de l’institutionnalisation de l’enfance délinquante et en besoin de protection : le cas des écoles de réforme et d’industrie de l’Hospice Saint-Charles de Québec, 1870-1950" (M.A., Université Laval, 2006); Andrée-Anne Lacasse, "L'institutionnalisation de l'enfance déviante : le cas de l'Hospice Saint-Charles (1870-1950)" (M.A., Université Laval, 2010). For Montreal, see: Tamara Myers, Caught: Caught: Montreal's Modern Girls and the

Law, 1869-1945 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006); Véronique Strimelle, "La gestion de la déviance

des filles et les institutions du Bon Pasteur à Montréal (1869-1912)" (Ph.D., Université de Montréal, 1999). 9 See: Donald Fyson, Magistrates, Police and People: Everyday Criminal Justice in Quebec and Lower

Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 2006). For

Quebec City’s gaols, see: Donald Fyson, "Prison Reform and Prison Society: The Quebec Gaol, 1812-1867," in Iron Bars & Bookshelves: A history of the Morrin Centre, ed. Louisa Blair, Patrick Donovan, and Donald Fyson (Montreal: Baraka Books, 2016); Martin Mimeault, La Prison des Plaines d’Abraham (Quebec: Septentrion, 2007).

10 See: André Cellard, Histoire de la folie au Québec de 1600 à 1850 (Montreal: Boréal, 1991); Peter Keating,

La science du mal : l’institution de la psychiatrie au Québec 1800-1914 (Montreal: Boréal, 1993); Vincent

St-Pierre, "Portes ouvertes sur l'institutionnalisation de la folie à Québec : étude de l'Asile de Beauport, 1845-1893," Université Laval, M.A., 2017.

11 See: Jean-Marie Fecteau, La liberté du pauvre : sur la régulation de l'assistance et de la répression pénale

the shift from French to British political power signals the beginning of separate English-speaking communities.12 The study ends at the turn of the twentieth century, which was a turning point for several reasons. First, there was a gradual return to rapprochement along ethno-religious lines.13 Second, the professionalization of social services, and a slow shift from private to public control, also began in the early decades of the twentieth century. Moreover, this date was chosen for practical reasons, as current access restrictions on primary sources for the twentieth century limit the scope of research on this topic. This is particularly true for some private archives related to Catholic institutions in Quebec City, whose gatekeepers are more suspicious of researchers following incidents that threw the charitable sector into disrepute, such as the Duplessis Orphans case.

This study considers the words ethnicity and identity in their broadest sense. Unfortunately, the word “ethnic” is often reserved for so-called “exotic” minorities or non-Western groups, an ethnocentric use that I explicitly reject. This is especially true of its popular use in French, though many Francophone scholars have also criticized such a narrow use.14 I work from the premise that Quebec’s Francophones are as “ethnic” as migrants from Britain, Ireland, or elsewhere.15 Ethnic groups are defined as people who share a sense of identity. As for “identity,” it is defined as being “based on the expression of a real or assumed shared culture

12 Although there were many individual English-speakers who settled in New France prior to the Conquest, there is no evidence that they grouped into communities or formed institutions; most of them probably ended up speaking French.

13 The admission of English-speaking Catholics to the Protestant Jeffery Hale’s Hospital at the turn of the 20th century signals this trend. See: Patrick Donovan, "L’hôpital Jeffery Hale : 150 ans de relations interethniques,"

Cap-aux-Diamants, no. 121 (2015): 27.

14 For examples, see Louis LaBorgue, "Les questions dites 'ethniques'," Recherches sociographiques 25, no. 3 (2002): 421-422; Jean-Loup Amselle, Mestizo Logics: Anthropology of Identity in Africa and Elsewhere (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998), 6-7.

15In this thesis, Britain is always used in its geographical sense. It refers to the island of Great Britain, which

includes England, Scotland and Wales. Ireland is the adjacent island. In the nineteenth century, the country combining both islands was known as the United Kingdom of Britain and Ireland.

On the other hand, the adjective “British” is typically used in a broader political sense to refer to the seat of government for a larger Empire, as was the case in the nineteenth century (e.g. “British Empire,” “British isles,” “British North America” etc.)

and common descent” that is determined through “the objectification of cultural, linguistic, religious, historical and/or physical characteristics.”16 Given the important role of religion in justifying boundaries in the nineteenth century, I occasionally use the adjective “ethno-religious” throughout the thesis. This does not imply that I consider religion and ethnicity as separate characteristics; rather, religion is used as a marker of ethnicity.

My analysis of ethnic relations is informed by the notion of group boundaries. This theoretical framework was introduced by Fredrik Barth in 1969. Before Barth, social scientists were more likely to define ethnic groups by focusing primarily on observable differences in their cultural traits and practices. Barth argued that this “cultural stuff” does not define groups; the sense of belonging to a distinctive group does not necessarily come about because of actual cultural differences but also, as the definition of identity above makes clear, “assumed cultural differences.” Neighbouring ethnic groups often have much in common yet may feel sharply opposed and different; Freud called this the “narcissism of small differences.”17 This is certainly the case for the three most numerically significant groups in nineteenth-century Quebec City: they all shared the same Western-European Christian background, came from European countries located next to each other with long histories of cultural interchange, and most of them spoke languages largely derived from Latin. Barth suggests that it is therefore the “boundary that defines the group, not the cultural stuff it encloses,” that it is social constructs that separate members of a group from non-members, not necessarily actual cultural differences between them.18 Boundaries serve to reinforce group bonds and separate members of one group from those of another. Danielle Juteau describes ethnic boundaries as having two sides: an internal face defined with reference to

16 Sian Jones, The Archaeology of Ethnicity: Constructing Identities in the Past and Present (New York: Routledge, 1997), 84.

17 For more about this, see Sigmund Freud, "Civilization and its Discontents," in The Freud Reader, ed. Peter Gay (New York: W.W. Norton, 1989), 751-752.

18 Fredrik Barth, "Ethnic Groups and Boundaries," in Theories of Ethnicity: A Classical Reader, ed. Werner Sollors (New York: New York UP, 1996), 300-301.

history and culture, and an external face constructed through relations with outsiders.19 Boundaries are kept up by the communities themselves to reinforce group bonds and to defend group interests. They can also be reinforced by external factors, such as tensions arising through power struggles between groups.20

Although the terms ethnicity and identity are fixed nouns implying fixed realities, and the notion of boundaries conveys solidity, all these concepts should be understood as changing, negotiable, and flexible. The same group’s boundaries may be sharply drawn and exclusive one year, and permeable and inclusive the next. Forms of identification may recede, and old identities may also be revived. These nouns are also imperfect: it is impossible to define an ethnic group in a way that would include all those who claim to be a part of it, so the notion of a group’s identity is always at best an approximation determined by general trends. Moreover, multiple group identities can overlap in one individual, and Quebec City had a fair share of bilingual, bicultural people with hybrid identities.21 This mutable and imperfect character gives ethnic groups a paradoxical edge; they are imagined but not imaginary22 or, as Juteau says, “réels bien que construits et tout autant concrets qu’idéels.”23 In short, these concepts are useful as explanatory devices, but there will always be exceptions when trying to pin down complex realities that are in constant flux. This is why my analysis of ethnic relations in Quebec City is described as constantly changing; an immutable list of generalizations cannot apply to the entire period under study.

This study will look at charitable services in Quebec City from the perspective of private organizations serving its English-speaking population, which was divided

19 Danielle Juteau, L'ethnicité et ses frontières (Montreal: Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 1999), 166-181. 20 Ibid., 35.

21 Ibid., 81.

22 Richard Jenkins, Social Identity, 3rd edition (London; New York: Routledge, 2008), 11. 23 Juteau, L'ethnicité et ses frontières, 10.

into two main subgroups in the nineteenth century: an important Irish-dominated Catholic group,24 and a smaller Protestant minority. The third major ethnic group in Quebec City was the French-speaking Catholic majority. It is possible to further subdivide English-speakers by focusing on geographical origins (Scottish, English, Welsh, Channel Islands) or religious affiliation (Presbyterian, Anglican, others; dissentient churches, established churches; high church, low church), and these sub-units will be explained and referred to when relevant. However, the logic of the three groupings above is based on boundaries that existed within the institutional infrastructure of the province: schools, hospitals, orphanages, and cemeteries came to be divided along the fault lines of religion and language, especially after the 1840s. Although the Protestant group encompassed many national origins and religions, Linda Colley shows that a long history of Catholic-Protestant conflicts dating back to the Reformation created a sense of Protestant solidarity in Britain and Ireland.25 This pattern was maintained in Quebec, and solidarity increased in the face of an increasingly powerful Catholic Church. This same tripartite division of ethnic groups in the province has been used in many other studies on the history of urban ethnic relations, such as the work of Sherry Olson and Patricia Thornton.26 The city also included other ethnic groups (Indigenous peoples, Chinese, Greek, Italian, Jewish, Black), but they represented an infinitesimal percentage of the total population and did not have social service networks of their own in the nineteenth century.27 It is important to recognize that Quebec City is located on traditional

24 This group will be referred to interchangeably as “English-speaking Catholics” and “Irish Catholics,” as was done at the time. The latter term may seem imperfect, but it is telling. While there was a small minority of people of English and Scottish descent among Catholics in Quebec, an Irish identity was imposed upon them by the Church and its institutions. The institutions were exclusively named according to iconic Irish saints (Saint Patrick, Saint Brigid) and there was little room within this community for the expression of other identities. Quebec’s English- and Scottish-Catholics were “honorary Irish Catholics.”

25 Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707-1837 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 1-5. 26 For a discussion of this see Sherry H. Olson and Patricia A. Thornton, Peopling the North American City:

Montreal, 1840-1900 (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2011), 11-13.

27 The Hebrew Ladies’ Aid Association of Quebec, also called Jewish Ladies' Aid, was founded in the twentieth century.

Indigenous territory, and relations with Indigenous peoples play an important part in its history. However, the 1901 census lists only 14 Indigenous and Métis individuals living in the city proper. The nation now known as the Huron-Wendat lived in a reserve over 15km from the city itself, largely integrated into Francophone Catholic society, and therefore fall outside our study’s geographical and linguistic limits. Even as Montreal became more ethnically diverse, with 6.42% of the population having origins outside Britain, Ireland and France in 1901 (rising to 12.8% in 1921), only 1.47% of the population in Quebec City claimed other origins in 1901. Only three of these smaller ethnic groups consisted of more than 50 individuals: 302 Jews, 212 Germans, and 94 Italians. As for visible minorities, the census lists only 28 Asians, and 9 Blacks.28 All these groups lacked the critical mass to form coherent communities that would need and support separate social service infrastructures. The Jewish population eventually grew and developed their own charitable associations in the twentieth century. However, these associations fall outside the time period of our study.29 The scant references to these minorities that appear in sources will be brought up when relevant.

Historiography

This thesis draws upon the historiography of two major areas: ethnic relations and charity. Since I seek to situate results in a broader geographical context, general

28 Canada, Fourth Census of Canada 1901, Volume 1 Population (Ottawa: S.E. Dawson, 1902), Table XI, 376-381. Canada, Sixth Census of Canada—Bulletin XI (Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics, 1921), Table 3, 26. Dorothy Williams argues that census returns for the black population are inaccurate due to clandestine

immigration, a high percentage of American nationals among Blacks, and the misclassification of mixed-race individuals. Nevertheless, she also states that the only regions with larger numbers of blacks in the province were Montreal and the Eastern Townships, not Quebec City. For more on this, see: Dorothy W. Williams, The

Road to Now: A History of Blacks in Montreal (Montreal: Véhicule Press, 1997), 27-36.

29 The Hebrew Ladies’ Aid Association of Quebec was founded around 1912, is probably the first specifically Jewish charitable organization in the city, and has received little attention from historians. Anctil shows that wealthier Jewish women and men were active in broader English-community oganizations in the nineteenth century, in part because the first wave of Jewish migrants came from Britain. “Quebec Hebrew Ladies’ Aid,”

The Canadian Jewish Chronicle, 14 January 1927; Pierre Anctil and Simon Jacobs, Les Juifs de Québec : quatre cents ans d'histoire (Québec: Presses de l'Université du Québec, 2015), 228.

studies were examined for cities in northeastern North America, with a particular focus on those relating to Montreal and Quebec.

Historiography of Ethnic Relations

The historiography of ethnic relations in Quebec reveals that the province’s French-speaking majority had a very different approach to migrant populations than English-speaking majorities elsewhere in North America. While Anglophones sought to assimilate newcomers, at times aggressively so, Francophones adopted an insular mentality that kept outsiders at bay. They were more interested in building boundaries and preserving their culture from foreign influence than in shattering the boundaries of the ethnic minorities around them. The pioneering work on migration by Helen I. Cowan, and more recent work by Martin Pâquet, show that it was actually Quebec’s British ruling minority that set up a bureaucratic apparatus to deal with migrants in the 1800s. For the most part, Quebec’s Francophone majority only became interested in integrating migrants after the mid-twentieth century.30 This created an atmosphere in Quebec that favored the erection of boundaries around mutually-exclusive ethnic groups, leading them to retain their identities for longer periods than elsewhere in North America.

General histories of Quebec City have not explored how this dynamic played out to any great extent. The most complete history of Quebec City to date is the three-volume Histoire de Québec et de sa région.31 While giving a sense of the demographics, occupational status, and institutional framework of the city’s ethnic groups, it does not stray too far into qualitative questions of ethnic relations. As the

30 Martin Pâquet, Tracer les marges de la cité : étranger, immigrant et État au Québec, 1627-1981 (Montreal: Boréal, 2005); Helen I. Cowan, British Emigration to British North America: The First Hundred Years, Rev. and enl. ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1961). See also: Michael Derek Behiels, Le Québec et la

question de l'immigration : de l'ethnocentrisme au pluralisme ethnique, 1900-1985 (Ottawa: Société historique

du Canada, 1991), 11; Fernand Harvey, "L'ouverture du Québec au multiculturalisme, 1900-1981," Revue

française d'études canadiennes 21, no. 2 (1986): 220.

number of English-speakers dwindles, they effectively disappear from such general histories even as their institutions remain. For more hard data, Ronald Rudin’s general history of Anglophone Quebec and François Drouin’s work on the ethnic composition of the population of Quebec City from 1795 to 1971 help quantify and contextualize this decline, which mostly took place in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.32 This is complemented by Sophie Goulet’s study of mixed marriages in the second half of the nineteenth century, which provides snapshots of the gradual yet slow integration of a declining English-speaking population into the French-speaking majority.33 Isabelle Beauregard-Gosselin’s recent thesis builds upon this by providing a longitudinal statistical portrait of Irish Catholics in Quebec City that includes interesting comparisons with Montreal.34 In the absence of comprehensive scholarly works on Quebec’s English-speaking minorities, Louisa Blair’s The Anglos does a good job of sketching out important milestones, though she focuses more on instances of interethnic collaboration than of conflict.35

The many studies focusing specifically on Quebec City’s Irish Catholic minority provide more detail about ethnic relations. An overall spirit of “bonententisme” emerges from a good part of the earlier published literature. Marianna O’Gallagher writes of Francophones and Irish working hand in hand in many organizations, of the generous French who adopted Irish famine orphans, and of the Protestants that financed Quebec’s Irish Catholic church, for instance.36 This “bonententiste” paradigm follows through in Nancy Schmitz’s look at the inclusive nature of

32 Rudin, The Forgotten Quebecers; François Drouin, "La population urbaine de Québec, 1795-1971 : origines et autres caractéristiques de recensement," Cahiers québécois de démographie 19, no. 1 (1990).

33 Sophie Goulet, "La nuptialité dans la ville de Québec : étude des mariages mixtes au cours de la deuxième moitié du 19ième siècle" (M.A., Université Laval, 2002).

34 Isabelle Beauregard-Gosselin, "Intégration d'une communauté minoritaire en période d'industrialisation: les Irlandais catholiques de la ville de Québec, 1852-1911," M.A., Université Laval, 2016,

35 Louisa Blair, The Anglos: The Hidden Face of Quebec City, 2 vols. (Quebec: Éditions Sylvain Harvey, 2005). 36 Marianna O'Gallagher, Saint Patrick's, Quebec: The Building of a Church and of a Parish 1827 to 1833 (Quebec: Carraig Books, 1981), 22; Marianna O'Gallagher, Saint Brigid's, Quebec: The Irish Care for their

People, 1856 to 1981 (Quebec: Carraig Books, 1981), 19; Marianna O'Gallagher, "Children of the Famine," The Beaver 88, no. 1 (2008).

Quebec City’s Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations, which she contrasts with the militant forms taken by the parade in other North American cities.37 This dissertation questions many of these assertions, at times revealing ulterior motives beneath the seeming interethnic cordiality. Historians have also introduced nuances to this narrative, such as Marie-Claude Belley and Jason King’s revisionist takes on the Irish famine orphans placed out into Francophone families, which wrongly tended to depict the latter’s motives as disinterested benevolence.38 Nevertheless, there is some relative truth to this positive spin: by virtue of Quebec City being a largely Catholic city, the historiography is unanimous that Irish Catholics fared better than in many other northeastern cities dominated by assimilationist Protestants.

Many historians have challenged the “bonententiste” narrative on Irish Catholics in Quebec City, especially since the 1990s. Their work reveals tensions with Protestants, Francophones, and even among the Irish themselves. Robert Grace charts a gradual decline in Irish Catholic relations with Protestant Anglophones following the massive arrivals of less fortunate famine migrants, noting that Quebec City became one of the major Canadian hotbeds of Fenianism and other radical anti-British forms of Irish nationalism.39 As for Irish Catholic relations with Francophones in Quebec, Grace describes them as being “sweet-and-sour”: “sour” in their struggles for control of Catholic institutions and over the same low-end jobs, but “sweet” through intermarriage and the rare instances of joint anti-imperialist

37 Nancy Schmitz, Irish for a Day: Saint Patrick's Day Celebrations in Quebec City, 1765-1990 (Sainte-Foy: Carraig Books, 1991).

38 Marie-Claude Belley, "Un exemple de prise en charge de l'enfance dépendante au milieu du XIXe siècle : les orphelins irlandais à Québec en 1847 et 1848" (M.A., Université Laval, 2003); Jason King, "Remembering Famine Orphans: The Transmission of Famine Memory Between Ireland and Quebec," in Holodomor and

Gorta Mor: Histories, Memories and Representations of Famine in Ukraine and Ireland, ed. Christian Noack,

Lindsay Janssen, and Vincent Comerford (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 115-144. 39 Robert J. Grace, "The Irish in Mid-nineteenth-century Canada and the Case of Quebec: Immigration and Settlement in a Catholic City" (Ph.D., Université Laval, 1999). The idea of Quebec as a hotbed of Irish

nationalism first appears in Peter Michael Toner, "The Rise of Irish Nationalism in Canada, 1858-1884" (Ph.D., National University of Ireland, 1974).

resistance.40 Regarding the latter, David DeBrou shows that Irish-French political alliances gradually declined in the years leading up to the Patriote Rebellions.41 Labour historian Peter Bischoff highlights some of the violent ethnic struggles between Irish and Francophone ship workers in the late 1870s, stressing however that these were only blips in an overall story showcasing exemplary interethnic working class solidarity.42 Political tensions within the Irish Catholic community itself are also apparent, notably in Catherine Coulombe’s analysis of Quebec’s Irish community organizations in the years 1851-1900.43 In short, Quebec City’s Irish Catholic community steered its own political course, had an active radical fringe, and occasional interethnic scuffles cast shadows on a situation that was typically better than the one faced by their counterparts in many other North American cities.

There has been much less written about Quebec City’s Protestant minority, but what little exists points to a relatively well-behaved and moderate group. Although anti-Catholic organizations like the Orange Order did exist for a short time in Quebec City, Simon Jolivet’s survey of their archives confirms Grace’s assertion that the city’s overwhelmingly Catholic majority made it "an eyesore to Orangemen and Ultra Protestants."44 Given this, Quebec was relatively free of the Protestant nativism that marred ethnic relations in other North American cities. There was little reason for Protestants to revolt, as they typically fared better than Catholics on the socio-economic scale despite their continued minority status. Nevertheless, there

40 Robert J. Grace, The Irish in Quebec: An Introduction to the Historiography (Quebec: Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture, 1993).

41 David DeBrou, "The Rose, the Shamrock and the Cabbage: The Battle for Irish Voters in Upper-town Quebec, 1827-1836," Histoire sociale-Social History 24, no. 48 (1991), 305-334.

42 Peter Bischoff, Les débardeurs au port de Québec : tableau des luttes syndicales, 1831-1902 (Montreal: Hurtubise HMH, 2009).

43 Catherine Coulombe, "Eire go Bragh : Irlande éternelle? Etude et prosopographie des organisations communautaires irlandaises catholiques de Québec de 1851 à 1900" (M.A., University of Ottawa, 2010). 44 Robert J. Grace, "The Irish in Quebec City in 1861: A Portrait of an Immigrant Community" (M.A., Université Laval, 1987), 125; Simon Jolivet, "Orange, vert et bleu : les orangistes au Québec depuis 1849," Bulletin

were some Protestant-Catholic confrontations, and many have yet to receive major scholarly attention, such as the 1853 Gavazzi riots, the 1872 election riots, and the 1886-87 Salvation Army “wars.”45 Richard Vaudry’s study of Anglicanism in Quebec City details some sectarian violence, but this took place among Protestants themselves (between Evangelical Anglicans and “High Church” Anglicans).46

Moving beyond Quebec City, the closest case for comparison is Montreal. The history of ethnic relations in the multicultural metropolis has received more attention than in Quebec City. The portrait that emerges from this historiography leads one to assume there was far greater strain between ethnic groups in Montreal than in Quebec City. After all, this is the city where an angry British loyalist mob fuelled by anti-French sentiments burned down the parliament in 1849. There are also more instances of anti-Catholic Orange Order violence, which Jolivet examines.47 There were religious riots around the coming of anti-Catholic firebrand preacher Alessandro Gavazzi in both Quebec and Montreal, but the Montreal riots were arguably more severe and resulted in several deaths.48 The Montreal press was also more polarized on the Ultramontane-liberal spectrum than

45 For an examination of the judicial response to collective violence in Montreal and Quebec City, see: Donald Fyson, "The Trials and Tribulations of Riot Prosecutions: Collective Violence, State Authority and Criminal Justice in Quebec, 1841-1892," in Canadian State Trials, Volume III: Political Trials and Security Measures,

1840-1914, ed. Susan Binnie and Barry Wright (Toronto: Osgoode Society / University of Toronto Press,

2009), 161-203. See footnote 44 for the Gavazzi riots, which have received more attention for Montreal than Quebec City.

46 Richard W. Vaudry, Anglicans and the Atlantic World: High Churchmen, Evangelicals, and the Quebec

Connection (Montreal; Ithaca: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003).

47 Jolivet, "Orange, vert et bleu."; Dorothy Suzanne Cross, "The Irish in Montreal, 1867-1896" (M.A., McGill University, 1969), 168.

48 Vincent Breton, "L'émeute Gavazzi : pouvoir et conflit religieux au Québec au milieu du 19e siècle " (M.A., UQAM, 2004); Dan Horner, "'Shame upon you as men!' Contesting Authority in the Aftermath of Montreal’s Gavazzi Riot," Histoire sociale-Social History 44(2011); Dan Horner, "A Barbarism of the Worst Kind:

Negotiating Gender and Public Space in the Aftermath of Montreal's Gavazzi Riot," (M.A., Queen's University, 2004); Elinor Kyte Senior, British Regulars in Montreal: An Imperial Garrison, 1832-1854 (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1981); Robert Sylvain, Clerc, garibaldien, prédicant des deux mondes : Alessandro

the more moderate Quebec City press.49 Tension within the Catholic Church between French and Irish Catholics was also greater, in part because Church leaders were more ideologically polarized, and Rosalyn Trigger’s study looks at how the pope was even asked to intervene to prevent what one observer feared could become an “all-out domestic war.”50

Looking beyond the province of Quebec, single community studies of the Irish dominate once again. The historiography of the Irish in English Canada arose largely in the 1980s. At first it focused more on the rural experience, seeking to undermine the urban focus of the older American historiography, most irreverently through the work of Donald Akenson.51 Despite the occasional study on Catholic-Protestant riots in Saint John52 and Toronto,53 much of the 1980s and 1990s Canadian historiography suggested that the situation was quite different and less explosive north of the border, that more migration took place before the famine, that Irish Protestant migrants outnumbered Irish Catholics, and that the Irish had largely assimilated by the early twentieth century. Nevertheless, recent studies stress important regional disparities within Canada, most importantly in the province of Quebec, where Irish Catholics outnumbered Irish Protestants and retained a distinct and strong Irish identity well into the twentieth century.54

49 Vallières et al., Histoire de Québec et de sa région, 1002.

50 Rosalyn Trigger, "The Geopolitics of the Irish-Catholic Parish in Nineteenth-Century Montreal," Journal of

Historical Geography 27, no. 4 (2001); Simon Jolivet, Le vert et le bleu : identité québécoise et identité irlandaise au tournant du XXe siècle (Montréal: Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 2011).

51 Donald H. Akenson, Small Differences: Irish Catholics and Irish Protestants, 1815-1922 (Montreal; Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1988).

52 Scott W. See, Riots in New Brunswick: Orange Nativism and Social Violence in the 1840s (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993).

53 Brian P. Clarke, Piety and Nationalism: Lay Voluntary Associations and the Creation of an Irish-Catholic

Community in Toronto, 1850-1895 (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1993); Michael Cottrell, "St.

Patrick's Day Parades in Nineteenth-Century Toronto: A Study of Immigrant Adjustment and Elite Control,"

Histoire sociale-Social History 25, no. 49 (1992); Mark George McGowan, The Waning of the Green: Catholics, the Irish, and Identity in Toronto, 1887-1922, McGill-Queen's studies in the history of religion. (Montreal:

McGill-Queen's University Press, 1999).

The voluminous historiography on Irish-Americans is quite comprehensive. American historians of the Irish were social history pioneers as early as the 1930s.55 Comprehensive regional studies cover many cities in the northeast, including Boston,56 New York,57 and Philadelphia,58 as well as interesting studies of smaller industrial cities such as Worcester59 and Fall River.60 In the past decade, Kevin Kenny and Timothy J. Meagher have attempted to synthesize all these narratives, the latter doing more to highlight regional differences.61 These studies show that, as in Quebec City, Catholic-Protestant relations were largely harmonious until the Irish famine migration. Sectarianism arose as poor Irish migrants gravitated to American cities, occupied low-end jobs, and clashed with the older Protestant majority in the 1840s and 1850s. The historiography stresses that difficulties were compounded by the rise of Protestant evangelicalism and Catholic Ultramontanism. Irish Catholics became increasingly “Catholic, embattled, and suspicious.”62 This was particularly true in Boston and industrial New England, whereas integration involved less friction the further inland or south one travelled, and the newer the cities in question.63 The San Francisco experience, for instance,

55 Kevin Kenny, "Introduction," in New Directions in Irish-American History, ed. Kevin Kenny (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), 2.

56 Oscar Handlin, Boston's Immigrants, 1790-1880: A Study in Acculturation, Rev. and enl. ed. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1991); Dennis P. Ryan, Beyond the Ballot Box: A Social

History of the Boston Irish, 1845-1917 (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1983).

57 Ronald H. Bayor and Timothy J. Meagher, The New York Irish (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996).

58 Dale B. Light, "Class, Ethnicity and the Urban Ecology in a Nineteenth Century City: Philadelphia's Irish, 1840-1890" (Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania, 1979); Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White (New York: Routledge, 1995).

59 Timothy J. Meagher, Inventing Irish America: Generation, Class, and Ethnic Identity in a New England City,

1880-1928 (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2001).

60 Anthony Coelho, "A Row of Nationalities. Life in a Working Class Community: The Irish, English and French Canadians of Fall River, Massachusetts, 1850-1890" (Ph.D., Brown University, 1980).

61 Kevin Kenny, The American Irish: A History (New York: Longman, 2000); Timothy J. Meagher, The

Columbia Guide to Irish American History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005).

62 Meagher, The Columbia Guide to Irish American History, 58. 63 Ibid., 102-107.

involved very little hardship for Irish Catholics.64 As in Canada, Irish Catholics struggled with French-Canadians and other Catholic migrants over control of the Church, education, and for low end jobs. However, they soon dominated and imposed their agenda in most places due to their overwhelming numerical superiority among Catholics. Upward mobility and acculturation gradually led to greater acceptance of Irish Catholics by the majority in the twentieth century. In fact, Irish-Americans came to be seen as a model to emulate by later generations of migrants.

French Canadians have not received as much direct attention as the Irish in the historiography outside Quebec. Aside from the aforementioned work on Fall River, few of the above studies deal with French Canadians outside Quebec. Studies of Francophone North America tend to stand on their own.65 They show that tight-knit and insular Francophone communities in the United States came to assimilate into the English-speaking majority after a few generations, though they had initially been depicted as unassimilable. In Canada, Robert Choquette looks at French-Irish tensions in Ontario, with French-Irish clerical pressure for the linguistic assimilation of French Canadians being the major flashpoint.66

In short, the historiography of ethnic relations in Quebec City has some important gaps, particularly with regard to studies about the Protestant minority. Thankfully, there is a wealth of material on urban ethnic relations outside the city that make it possible to situate the results of this dissertation in a broader context. This will allow me to provide new multilateral, longitudinal, and comparative perspectives on ethnic relations.

64 R. A. Burchell, The San Francisco Irish, 1848-1880 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980). 65 Yves Frenette, Marc St-Hilaire, and Étienne Rivard, La francophonie nord-américaine (Quebec: Presses de l'Université Laval, 2012); Yves Frenette, Les francophones de la Nouvelle-Angleterre, 1524-2000 (Montreal: INRS-Urbanisation, 2001); Yves Roby, Les Franco-Américains de la Nouvelle-Angleterre : rêves et réalités (Sillery: Septentrion, 2000); Dean R. Louder and Eric Waddell, French America: Mobility, Identity, and Minority

Experience Across the Continent (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993).

66 Robert Choquette, Language and Religion: A History of English-French Conflict in Ontario (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1975).

Historiography of Charity

Early studies on charity were usually written from whiggish or social control perspectives, at times a mixture of both. The former stressed an inevitable march of progress from the dark days of institutionalization to the glorious present of foster care. The social control paradigm was inspired by the rise of Marxist approaches in the social sciences during the 1960s and 1970s. The term “social control” was initially used in a positive sense to describe the processes used to ensure social cohesiveness. However, with time, the term took on dark repressive overtones; charitable organizations were described in the pessimistic light of bourgeois liberals seeking to dominate, to isolate and mold the poor according to their ideals and fears, while also serving their own individualistic capitalist interests.67 The social control approach was more prevalent and lasting in studies about Quebec's Catholic social services, in large part due to a general societal backlash against the near-total domination of the Catholic Church in Quebec before the 1960s and, more specifically, to fallout over the Duplessis Orphans case.68

These early studies were criticized for being too theoretically rigid. They ignored important aspects such as working-class agency, among others. Richard Fox wrote in 1976 that the social control approach “[assumes] that institutions are imposed by that elite or that society upon passive, malleable subjects.”69 Jean-Marie Fecteau

67 Walter I. Trattner, From Poor Law to Welfare State: A History of Social Welfare in America, 6th ed. (New York: The Free Press, 1999), 72; Patricia T. Rooke and Rodolph Leslie Schnell, Discarding the Asylum: From

Child Rescue to the Welfare State in English-Canada (1800-1950) (Lanham, MD: University Press of America,

1983), 405; Bienvenue, "Pierres grises et mauvaise conscience," 14-15.

68 The Duplessis Orphans were victims of a scheme whereby many orphans were falsely classified as mentally ill in order to obtain funding from the federal government between the 1940s and 1960s. The Catholic Church was complicit in this scheme and guilty of harsh treatment and abuse. See Bienvenue, "Pierres grises et mauvaise conscience," 13.

69 Richard Fox, "Beyond 'Social Control': Institutions and Disorder in Bourgeois Society," History of Education

built upon these early criticisms in 1980s Quebec by introducing a more complex social regulation approach that, among other things, considered the interplay of elite control and acts of resistance from the poor.70

Feminist studies in this period highlighted the role of gender dynamics in charitable associations. Many studies examine the “separate spheres” conventions that defined gender roles and placed limits on women’s involvement in charitable associations in certain cities and certain periods in history.71 The level of adherence to these conventions was often linked to the religious background of the women. Nancy Hewitt and Anne Boylan highlight the differences between charities run by conservative “benevolent” women from established churches, and “reformist” women from more evangelical backgrounds. These distinctions challenged earlier views that tended to place all women’s charities in the same category.72

Other scholars have provided new ways to qualify the different charitable organizations. For example, Timothy Hacsi’s overview of both Catholic and Protestant child charities in the United States divides institutions into isolating, protective and integrative. This framework more accurately reflects the different types of approaches than the harsh social control perspective. Isolating institutions wanted to break children from the culture, and often religion, of their parents to

70 “[La régulation sociale] apparaît donc comme un compromis fragile, toujours remis en question, entre l'exercice de la domination par les classes dirigeantes et la pratique de résistance des classes populaires” Jean-Marie Fecteau, Un nouvel ordre des choses : la pauvreté, le crime, l'État au Québec, de la fin du XVIIIe

siècle à 1840 (Outremont: VLB, 1989); Fecteau, La liberté du pauvre, 10.

71 For a comprehensive discussion of this, see: Anne M. Boylan, The Origins of Women's Activism: New York

and Boston, 1797-1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002). For a look at separate spheres

in Canada, see: Janet Vey Guildford and Suzanne Morton, Separate Spheres: Women's Worlds in the 19th

Century Maritimes (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1994).. For an analysis of separate spheres in Montreal’s

charitable sector, see chapter seven of Janice Harvey, "The Protestant Orphan Asylum and the Montreal Ladies' Benevolent Society: A Case Study in Protestant Child Charity in Montreal, 1822-1900" (Ph.D., McGill University, 2001), 268-310.

72 Nancy A. Hewitt, Women’s Activism and Social Change: Rochester, New York, 1822-1872 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984); Anne M. Boylan, “Women in Groups: An Analysis of Women’s Benevolent

Organizations in New York and Boston, 1797-1840,” Journal of American History 71, no. 3 (1984), 497-523; Quoted in Harvey, "The Protestant Orphan Asylum and the Montreal Ladies' Benevolent Society," 7-8.

provide a new moral basis. Protective institutions sought to protect the cultural and religious heritage of children from a world they saw as hostile to it. Integrative institutions began appearing after the 1870s in the United States, encouraging parental visits and sending children to nondenominational public schools outside the asylum.73 In Quebec, there was a definite shift from an isolating to a protective model in the nineteenth century. The push toward integration into a broader common culture did not exist in the late-nineteenth century model of sharply bounded communities, even within the boundaries of these cultures themselves. Many studies have looked at the tension between economic liberalism and the charity sector. Dennis Guest sees the history of charity marked by residual (liberal, market-oriented, laissez-faire) and institutional (solidaristic) concepts of social security. The former, which calls for minimal state intervention and stigmatizes charity-seekers, was dominant in the period prior to 1940, being especially strong in the mid-nineteenth century.74 Fecteau and others concur, by looking at how rising economic liberalism in the political sphere reformed a charitable sector that was seen as hindering the development of industrial capitalism. In a liberal society of free individuals, all were responsible for their own condition; the poor were therefore to blame for their own poverty, not the social conditions they operated in.75 These ideas also led to an increasing criminalization of the poor: gaols in Lower Canada doubled as homeless shelters, housing impressive numbers of vagrants. Donald Fyson builds upon Fecteau’s pioneering work76 to look at this summary imprisonment of the marginalized poor throughout Lower Canada in greater detail. He reveals that the incarceration of the poor took place on an unprecedented scale in Quebec City. The Quebec gaol also housed a

73 Timothy A. Hacsi, Second Home: Orphan Asylums and Poor Families in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 54-59.

74 Dennis Guest, The Emergence of Social Security in Canada, 3rd edition (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1999), 3-5, 9.

75 This idea is the subject of Fecteau’s La liberté du pauvre. 76 Fecteau, Un nouvel ordre des choses, 119-122.

disproportionate number of Irish Catholic female vagrants, which testifies to an insufficient charitable network.77

The historiography of charity in Quebec City contains many studies on individual charitable organizations and religious orders, but many adopt an uncritical self-congratulatory tone. There are important studies for the three major players on the Francophone side, namely the Sisters of Charity,78 the Good Shepherd nuns,79 and the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul,80 but no major synthesis offering a longitudinal view of the sector as a whole. On the Anglophone side, the recent studies are much slimmer. I have written commemorative booklets for the two major charitable homes, namely the Ladies’ Protestant Home (Protestant) and Saint Brigid’s Home (Catholic),81 the latter building on the pioneering work of Marianna O’Gallagher.82 All these studies, including the ones I have written, have serious limitations. Since most were produced by and for the organizations themselves, with the organization’s editorial input on content, many verge on the hagiographic, extolling the benevolent spirit of the key players involved and lacking a broader or more critical outlook. They gloss over the sectarian divisions that influenced the distribution of charity, the underlying gender and class issues that defined their structures, and downplay the conflicts and controversies.

77 Donald Fyson, "L'irlandisation de la prison de Québec, 1815-1885," (Notes for a paper delivered at the "Question sociale et citoyenneté" colloquium, UQAM, August 31, 2016), 342-345; Donald Fyson, "Prison Reform and Prison Society: The Quebec Gaol, 1812-1867," in Iron Bars & Bookshelves: A history of the Morrin

Centre, ed. Louisa Blair, Patrick Donovan, and Donald Fyson (Montreal: Baraka Books, 2016).

78 Nive Voisine et al., Histoire des Soeurs de la Charité de Québec, 3 vols. (Beauport: Publications MNH, 1998).

79 Josette Poulin, "Une utopie religieuse : le Bon-Pasteur de Québec, de 1850 à 1921" (Ph.D., Université Laval, 2004).

80 Réjean Lemoine, La Société de Saint-Vincent de Paul à Québec : nourrir son âme et visiter les pauvres,

1846-2011 (Quebec: GID, 2011).

81 Patrick Donovan and Ashli Hayes, The Ladies' Protestant Home: 150 Years of History (Quebec: Jeffery Hale Foundation, 2010); Patrick Donovan, Saint Brigid's and its Foundation: A Tradition of Caring Since 1856 (Quebec: Saint Brigid's Home Foundation, 2012).

Some aspects of poor relief in Quebec City have been examined more extensively. The Francophone Catholic response to illegitimate mothers and their children has received the most study, but none of the existing work touches much on how English-speakers related to these initiatives, or the alternatives provided by Protestants.83 The topic of Irish famine relief has also received considerable attention, mostly with regard to the Grosse Ile quarantine station. The most useful study for our purposes on this theme is Marie-Claude Belley’s look at responses to famine orphans in the 1840s, which focuses on post-quarantine Irish Catholic charitable networks within Quebec City itself.84

Despite all these individual studies, there are few that provide a broad view of Quebec City’s charitable sector, and what exists underrepresents the networks set up by English-speakers. For instance, Saint Bridget’s Asylum, the most significant English-language charitable institution in Quebec City, was recently omitted from a supposedly comprehensive survey.85 Johanne Daigle and Dale Gilbert did some valuable preliminary work on an inventory of children’s charities in the city, which includes some English-language institutions but focuses primarily on the Francophone Catholic sector due to a lack of existing studies on the former.86 This

83 France Gagnon, "Transitions et reflets de société dans la prise en charge de la maternité hors-norme : l'exemple de l'Hospice Saint-Joseph de la Maternité de Québec, 1852-1876" (M.A., Université Laval, 1994); Marie-Aimée Cliche, "Morale chrétienne et 'double standard sexuel' : les filles-mères à l'hôpital de la Miséricorde à Québec 1874-1972," Histoire sociale-SociaI History, 24, no. 47 (1991), 85-125; Virginie Fleury-Potvin, "Une double réponse au problème moral et social de l'illégitimité : la réforme des moeurs et la promotion de l'adoption par 'la sauvegarde de l'enfance' de Québec, 1943-1964" (M.A., Université Laval, 2006).

84 Belley, "Un exemple de prise en charge de l'enfance dépendante". For additional criticism of this narrative, see: King, "Remembering Famine Orphans."

85 Etienne Berthold 2015 study on the work of religious communities in Quebec includes many minor

Francophone institutions but fails to mention any of the Anglophone institutions where nuns worked, including major ones like Saint Bridget’s Home. See: Étienne Berthold, Une société en héritage : l'œuvre des

communautés religieuses pionnières à Québec (Quebec: Publications du Québec, 2015).

86 Johanne Daigle recognized this shortcoming and hired me as a research assistant to develop the preliminary research report that eventually led to this thesis. See: Johanne Daigle and Dale Gilbert, "Un modèle

d'économie sociale mixte : la dynamique des services sociaux à l'enfance dans la ville de Québec, 1850-1950," Recherches sociographiques 20, no. 1 (2008); Johanne Daigle and Dale Gilbert, "Naître et grandir à Québec, volet 'Les Bonnes Oeuvres'," CIEQ, http://expong.cieq.ca/.